vendredi, 18 novembre 2011

Zeitenthobenheit und Raumschwund

Zeitenthobenheit und Raumschwund

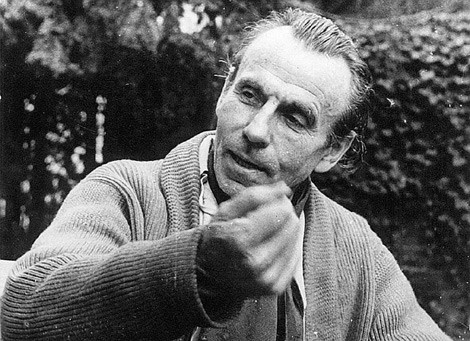

Ernst Jünger hat ein umfängliches Reisewerk hinterlassen. Im Laufe seines Lebens unternahm er mehr als 80 Reisen, etliche auch an exotische Orte in Übersee. Ausgehend von größtenteils unbekannten Dokumenten des Nachlasses – authentischen Reisenotizen und unveröffentlichten Briefen –, fügt Weber der Biografie dieses Jahrhundertmenschen das bislang ungeschriebene Kapitel eines intensiven Reiselebens hinzu.

Jünger reflektierte die Moderne als Beschleunigungsgeschichte und dokumentierte die um (Selbst-)Bewahrung bemühten Versuche, die katastrophalen Umbrüche, den permanenten Wandel des 20. Jahrhunderts literarisch zu bewältigen. Ernst Jüngers ›Ästhetik der Entschleunigung‹ liefert damit nicht nur eine Ästhetik des Tourismus und der literarischen Moderne, sondern hält auch Verhaltensregeln für eine Epoche bereit, in der das Zeit-für-sich-haben immer weniger möglich erscheint.

Jan Robert WEBER

Ästhetik der Entschleunigung

Ernst Jüngers Reisetagebücher

(1934 - 1960)

525 Seiten, gebunden mit Schutzumschlag

ISBN 978-3-88221-558-8

€ 39,90 / CHF 53,90

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, littérature, lettres, lettrees allemandes, littérature allemande, révolution conservatrice, weimar, ernst jünger |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 12 novembre 2011

Lovecraft Contra a Modernidade

00:05 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : lovecraft, modernité, littérature, littérature américaine, lettres, lettres américaines |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 11 novembre 2011

Le ballet des asticots

Le ballet des asticots

par Pierre Chalmin

Ex: http://lepetitcelinien.blogspot.com/

À propos de Joseph Vebret, Céline, l’infréquentable ? (Jean Picollec éditeur) et n°2 de la revue Spécial Céline, Céline sans masque. Autopsie d'un insupportable talent (Le Magazine des Livres, Lafont Presse, septembre/octobre 2011). «Celui qui parle de l’avenir est un coquin. C’est l’actuel qui compte. Invoquer sa postérité, c’est faire un discours aux asticots.» Céline, Voyage au bout de la nuit.

À propos de Joseph Vebret, Céline, l’infréquentable ? (Jean Picollec éditeur) et n°2 de la revue Spécial Céline, Céline sans masque. Autopsie d'un insupportable talent (Le Magazine des Livres, Lafont Presse, septembre/octobre 2011). «Celui qui parle de l’avenir est un coquin. C’est l’actuel qui compte. Invoquer sa postérité, c’est faire un discours aux asticots.» Céline, Voyage au bout de la nuit.On remet Céline en route, c’est tous les jours en cette glorieuse année du cinquantenaire de sa mort. Je commence à en avoir assez, je le dis tout net, et l’effet s’avère désastreux sur mes nerfs de ces fastidieuses compilations d’opinions ressassées, de tant de livres inutiles, de numéros «hors-série» fumeux fabriqués avec des bouts de chandelles, de tous ces avis doctes et cons et mille fois entendus de tout le monde et de n’importe qui : tant de broutilles indigentes, de temps perdu et de papier gâché… Je sais bien qu’il s’agit d’une industrie, que les illettrés aussi doivent gagner leur vie, etc. Permettez qu’étant femme du monde et non pas putain, je décline l’invitation à partouzer. On me proposa jadis d’écrire un petit ouvrage évoquant notre sujet : Les Céliniens, j’avais déjà mon idée, mon angle d’attaque. On me sait las méchant. On a renoncé. Je n’eusse rien pu écrire de toute façon, on ne diffame pas la canaille, à quoi serviraient sinon les lois ?

Bref, je reçois deux nouvelles publications d’anniversaire – cent et cent-unième, deux cent et deux cent-unième publiées en cette année faste ? – relatives à Céline, et Asensio me somme, avec ses grâces habituelles – pistolet sur la tempe – d’en rendre compte.

Je contemple la couverture du premier objet : Spécial Céline, c’est déjà le n° 2, – un troisième est annoncé en novembre ! –, qui s’intitule Céline sans masque. Une réminiscence de Sipriot et son Montherlant. Sous-titré : Autopsie d’un insupportable talent. Je bondis. Qui peut commettre une telle ânerie ? Je renvoie aux dictionnaires, n’importe lequel : ça ne veut rien dire. Je soupèse l’objet : 135 grammes. Pour 128 pages imprimées sur du papier torchon. Dites un prix ?… 17,50 euros ! C’est publié par Lafont Presse, un trust énorme. Ça doit leur coûter dans les 30 centimes à imprimer, et encore j’exagère peut-être, il y a longtemps que je n’ai pas joué à l’éditeur… J’ouvre et je lis le nom des deux compères éditorialistes à qui l’on doit je présume les jolis titres : MM. Joseph Vebret et David Alliot. David Alliot, je le connais, il publie un livre par trimestre sur Céline depuis quelques années. Joseph Vebret, un de ses amis me l’avait jadis décrit comme le plus désintéressé des amateurs de littérature, le plus fauché, le plus gratuit… (C’est peu de temps après que je l’ai vu deviser – oh ! quelques instants ! on n’a plus guère de patience à mon âge – avec Houellebecq, le passage juste où Houellebecq explique sa supériorité sur Baudelaire. Je me suis arrêté trente secondes plus tard, je pensais que Vebret se lèverait et partirait, que la messe était dite. Et puis pas du tout, ils continuaient de disserter sur le «génie» de Houellebecq : parce que c’est ainsi, Houellebecq a du génie, Céline du «talent» seulement…). Curieux de le retrouver là.

Second objet qui cette fois ressemble à un livre : Céline l’Infréquentable ? Publié par Jean Picollec, un ami de longue date. 208 pages, 16 euros. Je souffle un peu. Miséricorde ! l’auteur, c’est précisément et encore Joseph Vebret. Je saute à la page de faux-titre… «À Jules, parce que» : parce que quoi ? qu’est-ce que cette puérilité ! Tout de suite envie de le jeter aux orties «parce que merde»… Même page, trois épigraphes. Le nom du destinataire de la première est mal orthographié : lire «Marcel Lafaÿe»; deuxième citation, de Philippe Muray… sortie de son contexte et qui exprime exactement le contraire de ce que Muray a longuement écrit, expliqué, disséqué dans son Céline (je renvoie à ma contribution – bénévole ! – au copieux Muray à paraître à la mi-octobre aux éditions du Cerf, où précisément je traite le sujet); enfin, pied de page, dernière citation, de Gide cette fois, un article de la NRF d’avril 1938 (du 1er avril exactement, mais notre citateur n’y est pas allé chercher et c’est dommage parce que cet article, consacré entre autres à Bagatelles pour un massacre, recèle mille fois plus intéressant que la pauvre phrase qu’il en extrait) : «Les juifs, Céline et Maritan»… «Maritan» pour Maritain ! l’association est pourtant explicite quand on sait un peu d’histoire littéraire…

Soyons franc, ça commençait par trop mal. Ma patience avait été fort éprouvée déjà par un récent entretien avec le professeur Philippe Alméras à qui j’avais tenu à donner la parole puisque aussi bien tout le monde la lui refusait, mais dont la thèse ne m’a jamais convaincu. Je m’apprêtais à sabrer sans nuance ces nouvelles publications, et bien-succinctement. Heureusement, je dispose depuis plus de quinze ans d’un nègre critique, comme par hasard qui se trouve être le plus compétent des céliniens. Je l’ai donc sommé – pistolet sur la tempe, méthode Asensio – de me donner un avis nuancé sur ces deux ouvrages. Lisez plutôt.

Céline l’Infréquentable ?

– Je trouve ce petit livre très bien, c’était une très bonne idée, car il donne la parole à plusieurs céliniens qui ne se connaissent pas forcément et qui ont chacun une approche différente ou des réponses différentes… ou semblables. Une histoire avec Céline différente. Comment chacun y est venu, à quel âge, pourquoi, ce qu’il a apporté… Des âges différents; des formations différentes aussi. On pourrait reprocher à l’ouvrage de n’avoir pas donné la parole à Alméras, ou à André Derval qui aurait été plus critique à l’égard de Céline que certains. Même si on peut dire qu’aucun n’est complaisant à l’égard d’un certain Céline et que tous se posent des questions. Soulignons que ce sont des interviews, donc des «instants», des «réponses partielles», «limitées», qui demanderaient sans doute explications, nuances, compléments, non des thèses ou des études qui se voudraient complètes, définitives, mûrement réfléchies. Les interviews les plus intéressantes sont celles des jeunes céliniens : Laudelout, Mazet, Brami, Alliot. Les vieux céliniens ont tendance à plus parler d’eux-mêmes que de Céline… (N.B. : Les «vieux» céliniens sont donc, en procédant par élimination, Bruno de Cessole, François Gibault, Philippe Sollers et Frédéric Vitoux, l’ouvrage étant constitué de huit entretiens…).

Céline sans masque

– «Les céliniens : combien de divisions ?» par Marc Laudelout : une synthèse remarquable, Laudelout étant aux premières loges depuis plus de trente ans avec son Bulletin célinien pour juger des querelles intestines incessantes qui agitent le petit monde des céliniens.

Malavoy dans l’entretien qu’il accorde à David Alliot sous le titre : Le diable apparaît chez Céline est fort sympathique, il montre de l’enthousiasme, est honnête avec lui-même, mais un peu naïf tout de même, fait trop confiance à ce que dit Céline ou ce qu’en dit Lucette…

Céline et Montandon par Éric Mazet : analysant Montandon, fanatique communiste puis fanatique nazi, Mazet ne se contente pas de la caricature d’un être déjà caricatural; c’est fouillé, extrêmement précis, très éclairant.

Céline par Henri Mondor par David Alliot : il y a de l’exagération dans le titre ! Alliot n’apporte rien sur Mondor ni son texte. Même remarque pour son Céline à Kränzlin, le témoignage d’Asta Schertz. Plus intéressante est son exhumation des archives de la Préfecture de Police de Paris sur Céline. Une riche idée de rééditer ces textes peu connus ou difficilement trouvables.

L’étude de Lavenne : Image de l’écrivain, Céline face aux médias. De l’aura de l’absent à la présence du spectre, est intéressante en dépit d’un titre trop long… qui a cependant le mérite de résumer trente-six pages en moins de vingt mots.

Charles Louis Roseau, Céline ou le «marketing» de l’ancien combattant est assez complet sans rien révolutionner.

Véra Maurice, Quand les jupes se retroussent dans l’écriture célinienne, a réfléchi à son sujet…

Et voilà ce qui s’appelle de la critique enlevée ! Quant à moi, je relève la présence des mêmes noms dans les deux ouvrages, et je me demande, naïvement, pourquoi on ne demande jamais leur avis à des céliniens aussi éminents et décisifs et «qui bossent» comme disait Céline – «Tout ce que je vois, c’est que je bosse et que les autres ne foutent rien…» –, que Jean-Paul Louis qui est à l’origine de la publication des Lettres de Céline en Pléiade, mais encore de L’Année Céline depuis 1990, ni de l’extraordinaire Gaël Richard, auteur d’un Dictionnaire des personnages dans l’œuvre romanesque de Louis-Ferdinand Céline, qui prépare un Dictionnaire de la correspondance de Céline et une Bretagne de Céline, ouvrages édités parmi cent merveilles et autant de raretés par le même Jean-Paul Louis aux éditions Du Lérot (Les Usines réunies, 16140 Tusson – site : www.editionsdulerot.fr) ? La réponse est dans la question : ils bossent, ils n’ont pas de temps à perdre. Ni moi non plus pour finir.

En conclusion, et suivant ses centres d’intérêt, que le lecteur choisisse ce qu’il a envie de lire : lequel des deux ouvrages sommairement présentés supra, l’un, l’autre, aucun…

S’il recherche une introduction à l’œuvre de Céline, la plus abordable, entre biographie et essai, est le Céline d’Henri Godard qui vient de paraître (Gallimard, 594 pages, 25,50 euros). La biographie «historique» de François Gibault, en trois volumes : Céline – 1894-1932 – Le Temps des espérances; Céline – 1932-1944 – Délires et persécutions; Céline – 1944-1961 – Cavalier de l’Apocalypse, vient de reparaître au Mercure de France (compter un peu plus de 80 euros pour un peu moins de 1 200 pages).

Voyage au bout de la nuit, 505 pages, est disponible dans la collection Folio pour le prix de 8,90 euros; Mort à crédit, 622 pages, 9,40 euros, que nous conseillons aux néophytes pour aborder l’œuvre de Céline, se trouve dans la même collection.

Pierre CHALMIN

Stalker, 11/10/2011

00:10 Publié dans Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : céline, littérature, littérature française, lettres, lettres françaises |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 09 novembre 2011

Le bulletin célinien n°335 (novembre 2011)

Le bulletin célinien n°335 (novembre 2011)

Vient de paraître : Le Bulletin célinien n°335. Au sommaire :

Vient de paraître : Le Bulletin célinien n°335. Au sommaire :

Marc Laudelout : Bloc-notes

P.-L. Moudenc : « Céline’s band »

Robert Le Blanc : Jeanne Alexandre et « Voyage au bout de la nuit »

Jeanne Alexandre : « Voyage au bout de la nuit » [1933]

Rémi Astruc : Céline et la question du patrimoine

M. L. : Céline et Jean Renoir

Pierre de Bonneville : Céline et Villon (4 et fin).

Un numéro de 24 pages, 6 € franco.

Le Bulletin célinien, B. P. 70, Gare centrale, BE 1000 Belgique.

Le Bulletin célinien n°335 - Bloc-notes

André Derval (1) m’écrit que, contrairement à ce que j’ai laissé entendre, le colloque de février dernier n’a pas été organisé sous les auspices de la Société des Études céliniennes. « J’en suis personnellement responsable, en collaboration avec Emmanuèle Payen, de la BPI (Bibliothèque Publique d’Information, ndlr) », précise-t-il. Je suis heureux de cette rectification car j’avais déploré, on s’en souvient, qu’au cours dudit colloque, Céline ait été présenté comme un partisan du génocide. La présence active de François Gibault, président de la SEC, et d’André Derval, qui dirige la revue de la société, m’avaient induit en erreur. Mea culpa.

André Derval (1) m’écrit que, contrairement à ce que j’ai laissé entendre, le colloque de février dernier n’a pas été organisé sous les auspices de la Société des Études céliniennes. « J’en suis personnellement responsable, en collaboration avec Emmanuèle Payen, de la BPI (Bibliothèque Publique d’Information, ndlr) », précise-t-il. Je suis heureux de cette rectification car j’avais déploré, on s’en souvient, qu’au cours dudit colloque, Céline ait été présenté comme un partisan du génocide. La présence active de François Gibault, président de la SEC, et d’André Derval, qui dirige la revue de la société, m’avaient induit en erreur. Mea culpa.Il ne s’agit pas, soyons clairs, d’exonérer Céline de ses outrances. Ainsi, on regrettera, pour la mémoire de l’écrivain, que celui-ci se soit laissé aller à adresser, sous l’occupation, des lettres aux folliculaires de bas étage qui constituaient la rédaction de l’hebdomadaire Au Pilori, pour ne citer que cet exemple. Encore faut-il ajouter que des céliniens, peu suspects de complaisance, tel Henri Godard, admettent que Céline était dans l’ignorance du sort tragique réservé aux juifs déportés.

La Société des Études céliniennes n’est donc pas responsable de ces dérives et c’est tant mieux. Elle ne l’est pas davantage de l’édition du livre iconographique de Pierre Duverger, Céline, derniers clichés, coédité par l’IMEC et les éditions Écriture, dans une collection que dirige André Derval (2). Dans ce cas aussi, il faut s’en féliciter. La préfacière de cet ouvrage n’y affirme-t-elle pas que « Céline appela à l’extermination » [sic] ? C’est, une fois encore, interpréter abusivement le langage paroxystique du pamphlétaire.

Après la guerre, Céline se gaussait de ses accusateurs qui voyaient en lui « l’ennemi du genre humain » ou, pire, « un génocide platonique, verbal ». « On ne sait plus quoi trouver », ajoutait-il, désabusé (3).

Sur cette période trouble de l’occupation, il faut lire la somme de Patrick Buisson, 1940-1945, années érotiques, qui vient d’être rééditée en collection de poche (4). S’il est vrai que le rapport à l’argent, au pouvoir et au sexe détermine un individu, l’auteur montre avec perspicacité à quel point la libido joua un rôle majeur dans ces années tumultueuses. Céline y est défini comme un « thuriféraire de la France virile ». C’est sans doute l’une des raisons pour laquelle il est si mal considéré en notre époque qui voit le triomphe des valeurs féminines « au détriment de l’impératif communautaire avec lequel les valeurs mâles ont, depuis toujours, partie liée ». Et d’observer que « cette féminisation de la société s’accompagne d’un effacement symétrique des marqueurs identitaires du masculin tels que l’autorité et la force physique dont le capital social et symbolique semble promis à une lente mais inexorable évaporation ». C’est dire si Céline, qui fustigeait le pays femelle qu’était alors la France à ses yeux, aurait honni ce qu’il en est advenu.

Marc LAUDELOUT

1. Né en 1960, André Derval est l’auteur d’une thèse de doctorat, Le récit fantastique dans l'œuvre de Louis-Ferdinand Céline (Université de Paris VII, 1990). Il est actuellement responsable du fonds d’archives Céline à l’Institut Mémoires de l’édition contemporaine (IMEC) et directeur de la revue Études céliniennes éditée par la Société d’études céliniennes. Au cours du colloque de Beaubourg, André Derval a déploré, à juste titre, qu’en France aucun travail collectif relatif à Céline ne soit entrepris par une équipe d’enseignants chercheurs, comme cela se produit pour tant d’autres écrivains.

2. Pierre Duverger, Céline, derniers clichés (préface de Viviane Forrester), Imec-Écriture, 2011.

3. Entretien avec Louis-Albert Zbinden, Radio suisse romande [Lausanne], 25 juillet 1957.

4. Patrick Buisson, 1940-1945, années érotiques (I. Vichy ou les infortunes de la vertu ; II. De la Grande Prostituée à la revanche des mâles), Le Livre de Poche, 2011. Ce livre est paru initialement en 2008 (Éd. Albin Michel).

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Revue | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : céline, littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française, revue |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 08 novembre 2011

Les tribulations d'un poète au pays des Soviets

Emmanuel Carrère, Prix Renaudot pour son "Limonov"

par Minnie Veyrat

Ex: http://www.metamag.fr

Quel est le metteur en scène qui s’emparera, le premier, de l’incroyable scénario écrit par Emmanuel Carrère dans son dernier livre, « Limonov » tout juste consacré par un jury Renaudot qui a jeté sa gourme ? Car, tout y est. La naissance du héros : gros plan sur le bébé couché dans une vielle caisse d’obus et suçant une queue de hareng séché. A parents médiocres, enfance morose et c’est à l’adolescence que les choses commencent à bouger.

Savenko réalise vite qu’il trouvera argent et succès chez les voyous. Il tentera donc d’en faire partie pour essayer de sortir de la grisaille de sa petite ville de Kharkov. Notre apprenti voyou, malheureusement, est aussi poète, mais n’est pas Villon qui veut !

Là, entre en jeu Anna. Grosse femme excentrique dont la librairie sera l’antichambre (puis la chambre) des premier succès d’Edouard. Le voilà amant en titre et sa petite renommée locale commence. Il sera désormais Ed. Limonov.

Il reste qu’il faut bien vivre à Moscou où ils s’installent en 1968. Et ce n’est pas forcément déchoir pour un poète que de vendre des pantalons fabriqués à demeure. Exit Anna. Voici la splendide Elena qui partagera son rêve américain : devenir mannequin pour elle et connaître enfin le succès pour lui. Mais le rêve tourne rapidement au cauchemar.

Heureusement, une autre femme, Jenny, lui ouvre les portes d’un milliardaire dont il deviendra le « majordome poète » et que celui-ci se plaît à exhiber dans son salon. Le poète russe plaît dans le nouveau monde.

Elena le quitte et le plonge dans un de ces chagrins éthyliques à la Russe : un zapoï. Rien de tel que Paris pour se consoler. Limonov devient, ici, la coqueluche, pour un temps, des intellos de l’époque (Robbe–Grillet et Edern Hallier entre autres...), dont il fréquente le QG de la place des Vosges. Ses premiers livres autobiographiques paraissent, écrits que Madame Carrère d’Encausse juge, pour sa part, « pornographiques et ennuyeux ». C’est aussi à Paris qu’il rencontre Natacha, dont il tombe amoureux, malgré sa nymphomanie et son goût immodéré pour les boissons fortes. Là, on a envie de dire « stop ». Trop, c’est trop. Mais non, le film continue.

Une vie de merde ?

Limonov rêve de voir son pays retrouver sa grandeur. Mais, après un court passage à Moscou, où il apprend qu’Anna s’est pendue et que ses anciens amis sont soit morts soit en prison, plus rien ne le tente que la guerre. Quel meilleur endroit que les Balkans ? Croates, Serbes, Bosniaques… On s’y perd un peu, mais voici Limonov chez les Serbes en tenue camouflée, la kalachnikov à l’épaule.

Ses livres se vendant bien, il retourne à Moscou où commence le règne de Poutine. Le voilà rédacteur en chef contestataire d’une feuille de chou, organe d’un obscur parti national-bolchévique. Il manquait la case prison, c’est fait. Le voilà condamné pour terrorisme et trafic d’armes. C’est, bizarrement, en prison qu’il accédera à une certaine sérénité. L’auteur pourra enfin peaufiner son œuvre de poète maudit, oublié de tous.

C’est là qu’il écrit, d’après Emmanuel Carrère, son chef d’œuvre, « Le livre des eaux ». Hélas, les politiciens russes ont besoin de nouvelles idoles et ils découvrent qu’un nouveau « Dostoïevski » croupit dans un camp de travail, à Engels. On l’en fait sortir en grande pompe, sous les caméras de la télévision. La suite sera sans grand intérêt.

Vous croyez écrire le mot « fin ». Vous n’y êtes pas encore. Car, dans les tribulations de ce Russe à travers le siècle, tout est vrai ou presque. Qui plus est, le vrai Limonov existe. Emmanuelle Carrère l’a rencontré. Et il pourrait être indispensable de le consulter pour éclaircir quelques points de détail, avant de dire « moteur ».

Que dire du livre d’Emmanuel Carrère ? Bien que Limonov ne soit guère sympathique, on peut comprendre la sorte de fascination qu’un tel personnage ait pu inspirer à l’auteur qui se qualifie, lui-même, de « bourgeois-bobo » et qui, bien qu’à l’opposé du voyou ukrainien, aimerait sans doute, à ses heures, voir son propre visage se dégager du reflet de Limonov dans un miroir.

Limonov, quant à lui, termine sa vie dans un beau domaine, avec sa dernière épouse et son jeune enfant. Lorsque l’on évoque, devant lui, l’Asie centrale et ses immensités, ses yeux brillent encore. Toutefois, si l’on en vient, plus largement, à parler de sa vie et de son œuvre, il répond, désabusé : « une vie de merde... »

Ce livre se lit comme un roman d’aventures ; le style est alerte, mais, parfois, Carrère fait preuve de facilité en adoptant, avec une certaine gourmandise, le vocabulaire ordurier de son modèle.

Limonov d’Emmanuel Carrère aux éditions POL, 488 pages à 20 €

00:10 Publié dans Littérature, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : edouard limonov, prix renaudot, livre, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française, littérature |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 26 octobre 2011

Der Renegat der konservativen Revolution: Das Buch „Thomas Mann – Der Amerikaner“

|

|

|

Geschrieben von: Simon Meyer |

|

Ex: http://www.blauenarzisse.de/

|

|

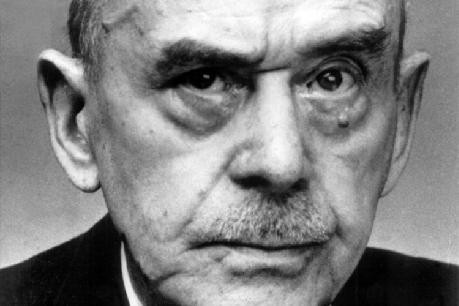

Als im Sommer 1914 auf die Schüsse von Sarajevo die allgemeine Mobilmachung folgte, machte einer der schon damals berühmtesten Schriftsteller Deutschlands keinen Hehl aus seiner Solidarität mit dem Reich und dessen Kriegsführung: Thomas Mann. Er wurde – nicht zuletzt wegen seines berühmten Namens – vom Kriegsdienst freigestellt. Doch sein literarisches Schaffen stellte er in den Dienst der Sache. Zwanzig Jahre später jedoch, befand er sich geographisch und politisch auf der anderen Seite. Thomas Manns literarischer Kriegsdienst begann noch 1914 mit der Schrift Gedanken im Kriege, auf die im gleichen Jahr der Großessay Friedrich und die große Koalition folgte. Und er legte nach. 1915 verfaßte er eine leidenschaftliche Verteidigung Deutschlands in einem Beitrag für die Schwedische Tageszeitung Svenska Dagbladet. Drei Jahre später, zum Ende des Krieges, sammelte er seine Gedanken unter dem Titel Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen – einem der Grundlagenwerke der Konservativen Revolution. Flucht vor der Heimat und der eigenen politischen Vergangenheit Um so verwunderlicher: Derselbe Schriftsteller propagierte gut zwei Jahrzehnte später aus seinem amerikanischen Exil heraus unablässig die bedingungslose Vernichtung Deutschlands als notwendig und verdient. Während des Zweiten Weltkriegs hatte Thomas Mann die amerikanische Staatsbürgerschaft erworben. Seit 1938 hatte er in den Vereinigten Staaten seinen ständigen Aufenthalt. Der Amerikaner Thomas Mann war den Deutschen ein Fremder geworden. In den Nachkriegsjahren war er nicht willkommen, zu frisch war bei vielen die Erinnerung an das, was Mann ihnen in den Rundfunksendungen der Alliierten entgegengeschleudert hatte. Doch auch als die Verhältnisse sich 1968 grundlegend geändert hatten, blieb er ein Fremdkörper. Zu liberal-großbürgerlich erschien Thomas Mann nun und wurde angesichts seiner frühen Schriften schon fast als unsicherer Kantonist behandelt, jedenfalls als Fossil aus einer überholten Epoche. Warum ging Thomas Mann, der für die Buddenbrooks mit dem Literaturnobelpreis ausgezeichnet wurde und darin eine hanseatische Handelsfamilie beschrieb, diesen Weg? Warum wurde er nicht nur aus der Notwendigkeit des Exils sondern aus innerer Überzeugung zum Amerikaner? Wäre nicht der Weg, den etwa Gottfried Benn, Martin Heidegger oder Ernst Jünger während der Jahre der nationalsozialistischen Herrschaft gingen, für ihn der wahrscheinlichere gewesen? In diese Fragestellungen, so hofft man, würde ein Buch des Deutschamerikaners Hans Rudolf Vaget, Professor an einem College in Massachusetts und ausgewiesener Kenner des Lebens und Schaffens Manns, etwas Klarheit bringen können. Dieses Buch befaßt sich mit den amerikanischen Jahren Manns, ist unlängst im S. Fischer Verlag erschienen und trägt den bezeichnenden Titel Thomas Mann, der Amerikaner. Ein detailreicher Blick in eine wenig bekannte Epoche Manns Der Autor beeindruckt im Buch mit einem Detailreichtum, der eine langjährige, akribische Arbeit erahnen läßt. In allen Einzelheiten schildert Vaget die Zeit und die Zeitgenossen Manns in den Vereinigten Staaten, so daß der Leser den Weg des Autors in seinem Exil bis ins einzelne nach verfolgen kann. Viele deutsche Leser Thomas Manns haben sich zunächst mit den Buddenbrooks und dem Zauberberg befaßt und haben auch Tonio Kröger und den Tod in Venedig gelesen. Alles Werke, die für den Deutschen Thomas Mann stehen. Die amerikanischen Jahre und die amerikanischen Verhältnisse jener Zeit sind oft weniger bis überhaupt nicht bekannt. Insoweit eröffnen sich durch das vorliegende Werk in großer Breite neue Aspekte auf einen Zeitraum, mit dem man sich bisher vielleicht kaum oder gar nicht eingelassen hatte. Leider erschöpft sich das Buch auch häufig in der Aneinanderreihung von Fakten und Ereignissen. Vaget ist stärker in der Schilderung der amerikanischen Protagonisten, etwa Franklin D. Roosevelts oder der Gönnerin Manns, Agnes Meyer. Thomas Mann selbst bleibt in den Schilderungen etwas blaß. Vor allem gelingt es Vaget nicht, den eigentlichen Grund für die Entwicklung Manns aus der Fülle der Details zu entwickeln. Die Verweise auf die Beschäftigung Manns mit den Dichtern Walt Whitman oder Joseph Conrad während der zwanziger Jahren, die eine erste tiefere Verknüpfung Manns zur anglo-amerikanischen Literatur entstehen ließ, mag biographisch interessant sein. Erhellend für die Amerikanisierung Manns sind sie nicht. Thomas Manns politischer Lagerwechsel wird nicht begründet Die Verwandlung Manns vom Verteidiger des deutschen Sonderwegs hin zu einem glühenden Anhänger des Sozialdemokraten Roosevelt bleibt dunkel. Denn gerade Roosevelt ist dem, was Mann noch 1918 für richtig hielt diametral entgegengesetzt. Roosevelt war ein Mann von ausgesprochener Deutschfeindlichkeit, der schon vor dem Krieg bedauerte, man habe es 1918/19 versäumt, den Deutschen den ihnen gebührenden Denkzettel zu verpassen. Im Gegensatz hierzu herrschte in der amerikanischen Öffentlichkeit überwiegend die Überzeugung vor, mit Versailles weit über das Ziel hinausgeschossen zu sein, und man blickte verschämt auf das Auseinanderklaffen des eigenen Anspruchs, mit dem man 1917 angetreten war, und dem Ergebnis der Friedensbedingungen. Roosevelt ging es – ähnlich wie Churchill – nicht nur um die Beseitigung Hitlers sondern um die Vernichtung Deutschlands als Subjekt der Geschichte. Thomas Mann erkannte dies und unterstützte Roosevelt trotzdem vorbehaltlos. Die Frage nach dem „warum“ scheint Vaget aber auch nicht besonders wichtig zu sein. Vaget ist selbst so durchdrungen von der Überzeugung der gerechten Sendung der Amerikaner. Und zwar der Amerikaner in ihrer Variante der demokratischen Partei und ihres Anspruchs auf eine Formung und Umgestaltung der Welt in ihrem Sinne. Eine Alternative, einen dritten Weg gleichsam, kann sich Vaget nicht ernsthaft vorstellen. Wiederholt schimmert so die eigene Vorliebe des Autors für die amerikanischen Demokraten von F. D. Roosevelt bis hin zu Obama durch. Zuweilen ist es schwer zu unterscheiden, wo die Wiedergabe der Gedanken Manns endet und eigene Ansichten des Autors in den Vordergrund rücken. Man hält den Autor zunächst für einen typischen Amerikaner, der trotz seiner ausgewiesenen Kenntnisse über Goethe, Mann und Nietzsche schlußendlich doch Amerikaner bleibt. Herbert Rosendorfer bemerkte in einem seiner Bücher, sowohl Sprache als auch Geschichte Deutschlands bliebe selbst dem intelligentesten Ausländer dem Grunde nach unbegreiflich. Aber Vaget ist Deutscher, im böhmischen Marienbad geboren. Gleichwohl scheint er sich derart amerikanisiert zu haben, wie dies auch beim späten Thomas Mann der Fall war. Da ihm selbst der Zugang zu dem fehlt, was Mann vor diesem Wandel ausmachte, kann er diesen Wandel auch nicht erklären. Jünger, Benn und Bergengruen: Das politische Exil war 1933 nicht der alleinige Weg So selbstverständlich, wie der Autor meint, war selbst 1933 der Weg nicht, den Thomas Mann genommen hatte. Zwar galt Mann seit etwa 1922, damals für viele überraschend, als Anhänger des parlamentarischen Parteienstaats, aber noch 1933 hätte ihn das Regime zumindest aus propagandistischen Zwecken mit offenen Armen begrüßt. Warum Mann nicht in der Schweiz blieb, sondern schlußendlich ein amerikanischer Linksliberaler mit noch dazu einem zuweilen pathologischen Haß auf Deutschland und die Deutschen wurde, bleibt nach der Lektüre dieses sehr umfangreichen Werkes komplett im Dunkeln. Man kann Thomas Mann nicht vorwerfen, die Möglichkeit eines deutschen Sonderwegs in der Moderne nicht erfaßt zu haben. Er sah dies und ging trotzdem den langen Weg nach Kaisersaschern. Thomas Mann bleibt in der Vielgestaltigkeit seiner Facetten und seiner Entwicklung ein Rätsel. Anders als viele konservativ-bürgerliche Deutsche, die der Ansicht waren, zunächst sollte der Krieg gewonnen werden, wie man danach Hitler loswerde, werde man dann schon sehen, wollte Thomas Mann zuletzt zwischen Hitler und Deutschland nicht mehr trennen. Warum wurde Thomas Mann zum Amerikaner? Eine letzte Antwort hierauf gibt auch das vorliegende Buch nicht und eine letzte Antwort kann hierauf vielleicht auch nicht gefunden werden. Hans R. Vaget: Thomas Mann, der Amerikaner. S. Fischer Verlag Frankfurt. Gebunden, 545 Seiten. 24,95 Euro |

00:10 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : révolution conservatrice, allemagne, thomas mann, livre, littérature, littérature allemande, lettres, lettres allemandes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 25 octobre 2011

Pierre Vial présente "Le loup-garou" d'Hermann Löns

Pierre Vial présente "Le loup-garou" d'Hermann Löns

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : nouvelle droite, pierre vial, nouvelledroite, littérature, lettres, lettres allemandes, hermann löns, littérature allemande |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 24 octobre 2011

Pierre Vial présente "Nouveaux Cathares pour Montségur" de Saint-Loup

00:13 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : nouvelle droite, saint-loup, marc augier, pierre vial, littérature, lettres, lettres françaises, littérature française |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 16 octobre 2011

Identità umana e pregiudizio etnico ne «I viaggi di Gulliver» di Jonathan Swift

di Francesco Lamendola

Fonte: Arianna Editrice [scheda fonte]

Da quando è apparso nelle librerie di Londra, nel 1726, il capolavoro di quella mente satirica e paradossale che fu Jonathan Swift (in una sua opera minore, la «Modesta proposta», del 1729, aveva suggerito, con la impassibile seriosità dell’economista, che i bambini poveri venissero utilizzati come cibo per i ricchi), ossia «Gulliver’s travels», esso non ha finito di dar luogo ad equivoci e fraintendimenti.

Basti dire che, per anni ed anni, di esso, o piuttosto di una sua edizione ridotta e “normalizzata”, si è voluto fare un classico per la gioventù; cosa ancora più amaramente paradossale di quel che avrebbe potuto immaginare il suo stesso autore, dato che tutto si può pensare de «I viaggi di Gulliver», tranne che sia un romanzo adatto ai bambini.

Se bastasse il fatto che il protagonista, a un certo punto, capita nel paese di Lilliput, dove tutto, a cominciare dagli abitanti, è quindici volte più piccolo che nel nostro mondo; oppure che, nella sua successiva avventura, egli finisce nel paese di Brobdingnag, ove il rapporto delle grandezze è rovesciato a sfavore dell’uomo, e lo stesso protagonista finisce rinchiuso in gabbia come un canarino, per il trastullo della gigantesca figlia del re; se bastassero tali aspetti puramente esteriori, allora vorrebbe dire che noi attribuiamo ben poca importanza a ciò che diamo da leggere ai bambini, oppure che non abbiamo capito nulla della terribile serietà di questo libro.

Che cos’è che non passa attraverso la macina della satira impietosa di Swift, misantropo inguaribile e scatenato pessimista? Non si salva nessuno: i suoi strali colpiscono con infallibile cattiveria i filosofi, gli storici, gli inventori (e questo in piena ideologia del progresso, in pieno secolo dei Lumi!); l’avidità e la brutalità degli Europei, protesi alla conquista degli altri continenti (e ciò nel Paese europeo che più di tutti si stava impegnando in questa sedicente “missione di civiltà”, la Gran Bretagna, dopo aver ridotto alla disperazione i vicini Irlandesi); la sete degli uomini di vivere eternamente; il primordiale istinto di sopraffazione proprio della natura umana, che viene significativamente contrapposto alla olimpica saggezza e all’esplicito disprezzo ad essa riservato dai nobili cavalli parlanti.

Dal punto di vista filosofico, «I viaggi di Gulliver» sono una vera e propria miniera di spunti per la riflessione, almeno quanto lo sono altri classici ammirati sotto il profilo letterario, ma, di solito, poco considerati in questa prospettiva, quali la «Divina Commedia» di Dante, il «Don Chisciotte della Mancia» di Cervantes e i «Promessi Sposi» di Manzoni.

Una miniera addirittura inesauribile: al punto che, se volessimo non già trattare, ma anche solo sfiorare, le principali tematiche filosofiche sottese al romanzo di Swift, avremmo la necessità di riempire parecchi volumi; qui, pertanto, vogliamo limitarci a toccare uno solo di tali aspetti, vale a dire quello riguardante il problema dell’identità e del pregiudizio etnico.

Formidabile accusatore dell’etnocentrismo, Swift insiste continuamente, lungo tutta la sua opera, sulla estrema difficoltà, anzi, sulla radicale impossibilità di superare i pregiudizi culturali della propria civiltà, nel momento in cui ci si trova alle prese con una civiltà diversa, i cui presupposti materiali e spirituali siano totalmente differenti dai nostri e anche da quelli che potremmo teoricamente concepire.

È ovvio che, così impostata la questione, la soluzione non può consistere nel generico e velleitario cosmopolitismo illuminista, benché tanto decantato da Voltaire e dagli altri “philosophes” francesi, a cominciare da Montesquieu: come si fa ad essere cittadini del mondo, infatti, se risulta per noi insormontabile la barriera culturale entro la quale siamo nati e cresciuti e dall’interno della quale tendiamo a giudicare, con arbitraria sicumera, altri modi di essere, di sentire e di pensare, del tutto diversi ai nostri?

Più sensato, semmai, appare un atteggiamento di scettica tolleranza, simile a quello già mostrato da Montaigne e del quale abbiamo già avuto, a suo tempo, occasione di occuparci (cfr. il nostro articolo «Michel de Montaigne e il cannibale felice», apparso sul sito di Arianna Editrice in data 13/12/2007).

Ha scritto Gianni Celati nel suo saggio introduttivo a «I viaggi di Gulliver» di Jonathan Swift (Feltrinelli, Milano, 2004, pp. XV-XVI):

«Che si tratti di meschini lillipuziani o di magnanimi giganti o di cavalli virtuosi, le abitudini dei vari paesi dipendono sempre da una fissazione su certi assiomi, definizioni nominali, dogmi o giudizi a priori; e sono una cecità che impedisce di vere oltre i limiti di una cultura, anche dove si tratta di cose osservabili a occhio nudo. Non solo nei comportamenti, ma anche nelle percezioni e nei pensieri intimi, la natura umana sembra ineluttabilmente dipendente da condizionamenti ambientali. Per cui il passaggio da un regime di abitudini all’altro corrisponde sempre a un lavaggio del cervello; e Gulliver non fa che subire lavaggi del cervello passando da un paese all’atro e adeguandosi a sempre nuove situazioni.

Se tutti i comportamenti e i pensieri dipendono così strettamente da condizionamenti esterni, viene da chiedersi dove ci porti questa lezione di relativismo radicale. Come si chiede Patrick Reilly: “che ne è della vantata libertà della mente, l’inviolabile santuario dell’io”? Spesso è stato detto che Swift porge un orecchio all’uomo perché si riconosca. Ma guardiamo Gulliver, che sembra un automa in balia della relatività , alieno in tutti i paesi dove capita e anche nella sua amata Inghilterra: se lui è l’uomo in cui specchiarsi, l’uomo è l’alieno del mondo, che appena fuori casa diventa come Gulliver una specie di “freak” da baraccone, alla maniera dei selvaggi che erano esibiti per lo svago delle folle o dei potenti. Dal libro risulta che l’identità umana viene riconosciuta attraverso “leggi di Natura”; le quali però sono giudizi a priori, abitudini di pensiero per discriminare l’indigeno dall’estraneo. Ad esempio, nella prima parte Gulliver si trova subito a essere classificato dai dotti lillipuziani come un uomo caduto dalla luna, in base a supposte “leggi di Natura”; e per gli stessi motivi i dotti di Brobdingnag lo classificano come un embrione abortivo, poi uno scherzo di natura; e i matematici lapuziani lo disprezzano perché non ha le loro stesse attitudini demenziali; infine i cavali lo espellono dalla Houyhnhnmland perché lo considerano una bestia irrazionale. Sempre le “leggi di natura” servono a definire la differenza tra l’indigeno e l’estraneo, e hanno il risultato di esporre Gulliver a sanzioni, a condanne al rischio della vita, all’espulsione.

Inoltre va notato che la consistenza di questi giudizi a priori si fonda soprattutto sulla boria dei sapienti, sui luoghi comuni della cultura, e in nessun altro libro la scienza dei dotti viene così collegata alle forme universali dell’etnocentrismo. È questo che impedisce di riconoscere nell’alieno Gulliver un’identità umana;, facendone appunto un “freak”, uno scherzo di natura: perché, nella scienza dei dotti, i valori differenziali diventano modi del pregiudizio etnico che decide l’identità dell’individuo; sicché i luoghi comuni d’ogni cultura rappresentano i criteri ultimi per distinguere gli individui umani al resto delle creature sensitive.

Questa una lezione che Swift ha imparato da Montaigne, uno dei suoi grandi ispiratori; e il «Gulliver»» sviluppa la visione di Montaigne sulla relatività delle opinioni e abitudini e di tutti i popoli. Una battuta nella quarta parte riassume il pensiero che attraversa il nostro libro: “dov’è mai un essere vivente non trascinato da preconcetti e parzialità per la sua terra natia?”: Bisognerebbe citare i tratti del pregiudizio etnico negli omiciattoli di Lilliput come nei cavali della Houyhnhnmland : pensare alle idee dei capi lillipuziani di macellare o accecare il povero Gulliver, ricordare le proposte nell’assemblea dei cavalli di castrare gli Yahoo. Che si tratti dell’untuosa crudeltà dei lillipuziani, della crudeltà orientale del re di Luggnagg, di quella olimpica dei cavalli, o di quella degli europei impegnati in guerre e massacri coloniali, la cultura delle nazionalità sembra che debba sempre confermare le proprie abitudini ricorrendo a sistemi di crudeltà.

Ogni cultura risulta un modo violento di marchiare gli altri, di segnare i limiti tra noi e l’estraneo. Perché chi è fuori dai limiti d’una cultura, l’alieno, sembra appartenere alla natura brada come le bestie, dunque dovrà essere domato, marchiato o castrato come le bestie. Questo mi sembra il succo delle disavventure di Gulliver, e fa venire un mente un celebre passo di Montaigne: “Noi non abbiamo altro punto di riferimento per la verità e la ragione che l’esempio e l’idea degli usi e opinioni del nostro paese. […] Perciò gli altri diversi da noi sembrano selvaggi, allo stesso modo in cui chiamiamo selvatici i frutti che la natura ha prodotto nel suo naturale sviluppo” (“Essais”, libro I, cap. XXXI).»

Abbiamo detto che la constatazione della irrimediabile limitatezza e dell’insuperabile condizionamento degli individui da parte della società fa sì che Swift propenda per una visione relativistica e scettica della condizione umana.

La sua satira, che assume talora i toni di un feroce sarcasmo, non sa o non vuole individuare una”pars costruens” sulla quale far leva, in tanto pessimismo antropologico; egli è un formidabile distruttore, ma non si pone nemmeno il problema di come l’uomo possa tentare di uscire dal condizionamento cui sempre viene sottoposto, senza neppure rendersene conto.

Non si può dire che ne abbia l’obbligo: Swift non è un filosofo, ma uno scrittore; il fatto che abbia saputo vedere e criticare, dietro la vuota retorica del cosmopolitismo illuminista e del progresso illimitato, il vuoto presuntuoso di una cultura incapace anche solo di comprendere i limiti della sua stessa ideologia, sta a significare che il grande demistificatore era di parecchie lunghezze più avanti dei suoi contemporanei, senza però spingersi innanzi fino a raggiungere, o almeno a intravedere, un terreno solido su cui poggiare i piedi.

Proviamo, dunque, a riprendere il discorso là dove l’autore de «I viaggi di Gulliver» lo lascia in sospeso, e vediamo a quali conclusioni si possa arrivare.

Oggi che la globalizzazione sta rimescolando le culture, le riflessioni di Swift appaiono di particolare urgenza, perché è ovvio che una mescolanza culturale, realizzata in tempi brevissimi e con l’unico denominatore comune del profitto economico di pochi, non può che portare a incomprensioni, tensioni, conflitti.

Non ci sembra, però, che l’appartenenza a una determinata cultura debba connotarsi prevalentemente in senso negativo, come Swift sembra pensare: al contrario, l’identità culturale è un elemento essenziale al buon vivere, perché consente all’individuo di interagire positivamente con l’ambiente, di comprendere gli altri ed esserne compreso, di condividere con essi valori, strumenti di pensiero e sensibilità. Un individuo senza identità è come una pianta secca e senza radici; una cultura senza identità è, a sua volta, come un deserto pietrificato, dove ogni cosa diviene anonima e intercambiabile.

È chiaro che l’identità culturale, se si chiude su se stessa e degenera in esclusivismo intollerante, finisce per rendere un pessimo servizio all’individuo, espropriandolo della sua unicità e precludendogli la via di ogni possibile arricchimento spirituale; ma, fino a che questo non avviene e la società si limita ad offrire all’individuo dei saldi punti di riferimento e una rete di relazioni armoniose con l’altro, non solo non ne limita la creatività, ma gli offre un insostituibile punto d’appoggio, sul quale far leva e con il quale orientarsi.

Il problema è che, oggi, da un lato le culture tendono ad abdicare alla propria autonomia e a lasciarsi omologare in un generale appiattimento, ciò che produce un gravissimo impoverimento anche per il singolo individuo; dall’altro, tendono a svuotarsi dall’interno e a dimenticare le proprie radici, trasformandosi in quelle “società liquide” di cui parla Zygmunt Bauman, dominate dalla smania del cambiamento e caratterizzate dalla riduzione del cittadino a consumatore compulsivo di beni sempre più inutili, senza i quali, però, egli si sentirebbe povero ed escluso.

Il grande pericolo, perciò, al giorno d’oggi, non è tanto l’etnocentrismo, quanto l’anonimità e la degradazione delle culture, in nome di un “progresso” incontrollabile e di un tecnicismo esasperato che relegano sempre più l’individuo nel ruolo di semplice accessorio di un sistema efficiente, ma impersonale, dominato dalla sola dimensione economica.

E non ci sembra si possa dire che i pregiudizi dell’economia siano più accettabili di quelli di origine culturale: al fanatismo identitario si sostituisce il non meno temibile ricatto dello status economico-sociale.

Nel romanzo di Gulliver, “freak” è lo straniero in quanto diverso, ridotto a fenomeno da baraccone; nella società globalizzata contemporanea, ove imperano la tecnoscienza e le leggi del profitto, “freak” è colui che non può o non vuole consumare secondo le modalità totalitarie del consumismo imperante: chi, per esempio, si accontenta di essere fruitore di beni e servizi e non più di marchi, di firme, di simboli legati all’industria.

“Freak”, abnorme, è, oggi, colui che voglia essere se stesso e rifiutare le maschere dell’avere e dell’apparire: egli viene guardato con sospetto e disprezzo, proprio come i lillipuziani guardano Gulliver, così ingombrante nella sua diversità.

Ma tale diversità è un bene, non un male, sia per il singolo individuo, sia per la società intera.

Potrebbe una società permettersi di fare a meno di quel cinque per cento creativo, di quella piccola minoranza di persone che non si adeguano passivamente a tutte le mode e a tutti i pregiudizi, ma che coltivano in se stesse la preziosa, inestimabile pianticella dell’originalità, della consapevolezza, dell’apertura esistenziale?

Tante altre notizie su www.ariannaeditrice.it

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : gulliver, jonathan swift, 18ème siècle, angleterre, lettres, lettres anglaises, littérature, littérature anglaise |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 15 octobre 2011

Céline, un génie des lettres, un enfant et un fou

Par Amaury Watremez. A propos de la sortie en Folio d’une partie de la correspondance de Céline, les Lettres à la NRF, passionnantes.

Par Amaury Watremez. A propos de la sortie en Folio d’une partie de la correspondance de Céline, les Lettres à la NRF, passionnantes.Les Lettres à la NRF de Céline sont au fond comme un journal littéraire de ce dernier, et dans les considérations de ces deux misanthropes on perçoit des remarques qui se rejoignent très souvent sur eux, sur leur entourage, leur œuvre, le reste de l’humanité.

Ce que dit Céline dans sa correspondance sur la littérature, il le mettra en forme plus clairement encore dans les Entretiens avec le professeur Y en particulier. Céline écrit tout du long de sa vie littéraire qui se confond avec sa vie tout court car la littérature, n’en déplaise aux petits marquis réalistes, est un enjeu existentiel. Il écrit des lettres pleines de verve, parfois grossières, à la limite du trivial. Il y explique, en développant sur plusieurs courriers sa conception de l’écriture, basée sur le style. Il se moque de l’importance de l’histoire par l’écrivain (« des histoires, y’en a plein les journaux »), se moque des modes littéraires, n’est pas tendre avec ses amis, dont Marcel Aymé, dont il suggère l’édition sur papier toilettes ainsi que l’œuvre de Jean Genet, comme un gosse jaloux du succès de ses pairs, qui entend conserver toute l’attention sur lui.

Car il cultive les paradoxes, il est misanthrope mais a soif de gloire et de la reconnaissance la plus large possible des lecteurs.

Ses correspondants ne sont pas sans talent, ainsi Gaston Gallimard, son éditeur : on s’étonne encore du flair remarquable de celui-ci en matière d’édition, on chercherait vainement son équivalent de nos jours où domine à des rares exceptions le clientélisme, l’obséquiosité, le copinage entre « beaux messieurs coquins et belles dames catins » pour reprendre le terme de Maupassant dans sa correspondance. Ce qui montre d’ailleurs que ce copinage ne date pas d’hier, ce qui n’est pas une excuse vu les sommets himalayens qu’il atteint en ce moment dans les milieux littéraires en particulier, culturels, ou plutôt « cultureux » en général.

Céline comme Léautaud est un misanthrope littéraire exemplaire, ce que sont finalement la plupart des littérateurs de toute manière, qui se libèrent des blessures subies par eux à cause de l’humanité en écrivant, en ouvrant un passage vers des univers mentaux et imaginaires inexplorées. Mais l’écriture n’est pas qu’une catharsis, contrairement à ce que les auteurs d’auto-fiction voudraient nous laisser croire, eux qui font une analyse en noircissant des pages qui ont pour thème central l’importance de leur nombril.

La misanthropie en littérature est un thème couru, maintes fois traité et repris, souvent lié à la pose de l’auteur se présentant en dandy, en inadapté, en poète maudit incompris de tous.

C’est un sujet d’écriture au demeurant très galvaudé.

Parfois, l’auteur qui prend cette posture a les moyens de ses prétentions, de ses ambitions, et d’ailleurs la postérité a retenu son nom à juste titre, pour d’autres, c’est souvent assez ridicule voire grotesque. Les artistes incompris de pacotille, les rebelles de ce type sont des fauves de salon comparés aux écrivains qui refusent les mondanités, les dorures, et l’ordure. Ces fauves de salon ne sont pas méchants, ils sont émouvants à force d’évoquer Rimbaud ou Baudelaire pour tout et n’importe quoi, de manière aussi désordonné que l’adolescent post-pubère clame sa détestation de la famille pour mieux y coconner, et continuer à se vautrer ensuite dans un mode de vie bourgeois. Et après tout, Claudel qui se réclamait de Rimbaud, et qui était un grand bourgeois conservateur, était aussi un grand écrivain, les fauves de salon peuvent donc avoir encore quelque espoir que leur démarche ne soit pas totalement vaine.

C’est encore mieux quand le prétendu inadapté rebelle, artiste et créateur, est jeune, et vendu comme génie précoce pour faire vendre (ne surtout pas oublier la coiffure de « rebelle » avec mèche ou frange « ad hoc »).

Cette rentrée littéraire, on nous refait le coup avec Marien Defalvard dont le livre s’avère certes plutôt bien écrit, et certainement réécrit, mais sans personnalité, sans saveur, sans couleur, sans odeur.

Les personnages misanthropes les plus connus sont le capitaine Némo et Alceste, les plus intéressants, les plus remarquables aussi. Louis-Ferdinand Destouches alias Céline, semble être eux aussi de véritable misanthrope, détester ses semblables.

Au final, on songe plutôt à son encontre au mot de Jean Paulhan répondant à une lettre d’injures de Céline, ces misanthropes, ce sont à la fois des enfants, des fous, mais aussi des hommes de talent, des génies avides de gloire. Ils ont des blessures diverses, surtout à cause du monde, dont ils ressentent la sottise et la cruauté plus fortement que les autres. Ce sont finalement des blessures d’amour, en particulier pour Léautaud, mais aussi pour Céline, qui feint de haïr ses semblables mais qui veut à tout prix ou presque leur reconnaissance.

Céline fût fidèle à Lucette, toujours discrète, toujours présente, consolatrice, fluette et solide, qui avait son atelier de danse au-dessus du cabinet de l’écrivain à Drancy, l’exception peut-être de quelques « professionnelles » de Bastoche, ce qu’évoque Claude Dubois dans son ouvrage sur La Bastoche : Une histoire du Paris populaire et criminel dont l’auteur de ses lignes a déjà parlé sur Agoravox.fr. Derrière les pétarades de l’auteur du Voyage on distingue aussi un grand pudique goûtant la présence discrète de sa femme attentionnée.

Ces deux auteurs comme beaucoup de natures très sensibles sont dans l’incapacité au compromis sentimental, amical, à l’amour mesuré, raisonnable, sage, et finalement un rien étriqué. Il est difficile de leur demander de rentrer dans un cadre ce dont ils sont incapables.

Sur ce point là, Céline est aussi un enfant comme Léautaud, on sent dans ses amitiés, à travers ses lettres à Roger Nimier, Denoèl ou Gaston Gallimard, cette recherche de la perfection et d’une amitié sans réelle réciprocité où c’est l’ami qui couve, qui prend les coups, les responsabilités à la place, et à qui l’on peut reprocher la brutalité et la sottise du monde extérieur, du monde des adultes où ils ne sont jamais au fond rentrés en demeurant des spectateurs dégoûtés par ce qu’ils y voient.

Sa misanthropie est aussi sa faiblesse, mais comme du charbon naissent parfois quelques diamants, de celle-ci naît le génie particulier de son œuvre littéraire. Cette hyper-émotivité du style que l’on trouve surtout chez Céline, ce chuchotement fébrile et passionné.

Amaury WATREMEZ

Agorafox.fr, 26/09/2011.

> Mes terres saintes, le blog d'Amaury Watremez.

00:10 Publié dans Littérature, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : céline, livre, lettres, littérature, lettres françaises, littérature française |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 14 octobre 2011

Il Dio di Ezra Pound

di Luca Leonello Rimbotti

Fonte: mirorenzaglia [scheda fonte]

Il contraltare di Evola, dal punto di vista di una lettura “pagana” del Fascismo, fu certamente Ezra Pound. Se il primo del regime mussoliniano intese fare un risultato moderno delle virtù guerriere ario-romane, un’epifania della potenza, il secondo ne scorse i connotati di religione agreste, la cui continuità sarebbe stata garantita – più che non ostacolata – da forme di cristianesimo non dogmatiche, legate alle credenze arcaiche relative alla sacralità della terra. Se Evola vide nel movimento dei fasci una rinascenza del fato di gloria, qualcosa dunque di “uranico”, Pound rimase colpito invece dalla natura tellurica, diremmo quasi Blut-und-Boden, del comunitarismo fascista del suolo e del seme. Il significato è comunque, nei due casi, quello di una continuità ininterrotta, ben rappresentata dal particolare tipo di imperialismo veicolato dal Fascismo, tutto incentrato sull’idea di redenzione del suolo, di lavoro dei campi, di civilizzazione attraverso la coltivazione e la valorizzazione della terra.

Il contraltare di Evola, dal punto di vista di una lettura “pagana” del Fascismo, fu certamente Ezra Pound. Se il primo del regime mussoliniano intese fare un risultato moderno delle virtù guerriere ario-romane, un’epifania della potenza, il secondo ne scorse i connotati di religione agreste, la cui continuità sarebbe stata garantita – più che non ostacolata – da forme di cristianesimo non dogmatiche, legate alle credenze arcaiche relative alla sacralità della terra. Se Evola vide nel movimento dei fasci una rinascenza del fato di gloria, qualcosa dunque di “uranico”, Pound rimase colpito invece dalla natura tellurica, diremmo quasi Blut-und-Boden, del comunitarismo fascista del suolo e del seme. Il significato è comunque, nei due casi, quello di una continuità ininterrotta, ben rappresentata dal particolare tipo di imperialismo veicolato dal Fascismo, tutto incentrato sull’idea di redenzione del suolo, di lavoro dei campi, di civilizzazione attraverso la coltivazione e la valorizzazione della terra.

Ezra Pound è stato probabilmente il maggiore e più profondo cesellatore del ruralismo fascista, che giudicò elemento direttamente proveniente dagli arcaici riti latini legati alla fertilità e ai cicli di natura. La “battaglia del grano”, l’impresa delle bonifiche, la celebrazione del pane quale simbolo di vita santificato dalla fatica quotidiana, non sarebbero stati, per il poeta americano, che altrettanti momenti in cui gli antichi misteri pagani tornavano a parlare al popolo, e sotto la sollecitazione ideologica di un regime che fu allo stesso tempo quanto mai attento alla modernità. E che registrò il passaggio dell’Italia a nazione più industriale che agricola, con un numero di operai che per la prima volta nel 1937 superò quello dei contadini.

Questo doppio registro, tipico del Fascismo, di portare avanti insieme i due comparti, senza deprimerne uno a vantaggio dell’altro, questa simmetrica capacità di operare lo sviluppo industriale e quello agricolo, iniettando la modernizzazione nelle tecniche di coltura ma rinforzando l’attaccamento atavico al suolo, fu la formula adottata da Mussolini per promuovere il progresso senza intaccare – ma anzi rinsaldandolo – il patrimonio immaginale legato alla terra, e per di più abbinandolo ad un reale incremento della capacità produttiva, affidata alla scelta autarchica. Della terra, con costante perseveranza, si celebrò la sacralità, facendo del suolo patrio, quello da cui il popolo ricava la fonte di vita, una vera e propria religione di massa. Questa religione popolare fascista, riscoperta intatta dall’antichità e dotata di moderne applicazioni anti-utilitariste ed anti-speculative, ebbe in Pound un cantore geniale.

La recente uscita del libro di Andrea Colombo Il Dio di Ezra Pound. Cattolicesimo e religioni del mistero (Edizioni Ares) ce ne fornisce un nuovo attestato. In questo agile ma importante lavoro noi riscopriamo tutta la profondità di una concezione del mondo incentrata su ciò che Pound definitiva “economia sacra”. Come già fatto da Caterina Ricciardi nel 1991, nella sua antologia di scritti giornalistici di Pound, anche Colombo sottolinea questa impostazione del poeta che, forte della sua recisa ostilità al mondo liberista del profitto finanziario e nemico giurato dell’usura, vide nella sana e naturale economia fascista un preciso riverbero di ancestrali tendenze sacrali. In una serie di articoli pubblicati sul settimanale “Il Meridiano di Roma” fra il 1939 e il 1943, Pound andò indagando le origini italiche, perlustrandone la vena religiosa relativa ai misteri e ai riti di fertilità. In tal modo, «Roma è Venere, l’antica dea dell’amore che ritorna a restituire il sogno pagano agli uomini», realizzando il contatto vivente fra l’antichità e il presente moderno: «E Mussolini, il Duce della bonifica e della battaglia del grano, diventa per il poeta il riesumatore dell’antica cultura agraria, la religione fondata sul mistero sacro del grano, mistero di fertilità».

Entro questi grandi spazi ideologici di rinascita moderna delle logiche arcaiche, Pound ingaggiò la sua personale lotta contro quel mondo di speculatori, affaristi privi di scrupoli e autentici criminali da lui individuato nei governanti angloamericani, che in nome dell’usura finanziaria e dell’idolatria dell’oro non avevano esitato a scatenare contro i popoli a economia organica la più distruttiva delle guerre. Proveniente per nascita egli stesso dal pericoloso milieu presbiteriano, come Colombo ricorda, Pound ben presto se ne distaccò, avvicinandosi ad una interpretazione del cristianesimo come continuità pagana sotto specie devozionale ai santi locali, alle varie Madonne, alle processioni popolari d’impronta rurale. Convinto – e a ragione – di una netta presenza neoplatonica nella stessa teologia cattolica, Pound finì col considerare la religione di Cristo come una forma neopagana di accettazione del mistero della vita. Egli contestava alla radice la filiazione del cristianesimo dall’ebraismo, affermando che invece ciò che si doveva stabilirne era la continuità con l’ellenismo e con il politeismo in auge nell’Impero romano, al cui interno il cristianesimo poté inserirsi senza traumi particolari, in virtù della sua sostanza di religione dapprima solare, erede del mitraismo, poi anche tellurica, erede delle venerande liturgie agresti.

Pound conobbe gli scritti di Frazer e di Zielinski, allora famosi, ma noi possiamo aggiungere che questa lettura poundiana, tutt’altro che peregrina, ha trovato conferma in molti studiosi di religione anche molto importanti, da Cumont a Wind, da Seznec fino a Wartburg: il cristianesimo, ed ivi compreso talora anche il papato, veicolavano sostanziose dosi di neoplatonismo pagano. L’interesse di Pound per figure come Gemisto Pletone o Sigismondo Malatesta – esemplari del neopaganesimo rinascimentale – furono il lato filosofico di un mondo ammirato profondamente da Pound, quello dell’etica economica medievale e proto-moderna, coi suoi fustigatori dell’interesse e della speculazione: un San Bernardino, ad esempio, che combatté tutta la vita l’usura, in forme anche violente e non meno anticipatrici di certi argomenti moderni.

Pound nel paganesimo, e di nuovo nel cristianesimo francescano (notoriamente di ispirazione neoplatonica), vide l’antefatto di quella guerra aperta alla schiavitù dell’interesse che solo con il Fascismo, e con la sua ideologia corporativa del “giusto prezzo”, divenne movimento mondiale di lotta al disumano profitto liberista. Il prezzo della merce, quando stabilito dalla mano pubblica, dà garanzie di giustizia, è regolato dal potere politico, ha veste legale, è insomma pretium justum; quando invece è affidato al gioco incontrollato degli interessi privati, come accade nelle economie liberiste, fornisce l’evidenza di una guerra belluina fra speculatori, a tutto danno del popolo e del suo lavoro.

Questi concetti Pound li martellò in scritti e discorsi alla radio italiana durante la guerra, e sono massicciamente presenti anche nei Cantos. E questo gli costò, come noto, l’infamia della gabbia e del manicomio, cui lo destinarono i “democratici” vincitori. Questa di Pound fu una battaglia a difesa del lavoro onesto contro la bolgia degli speculatori. A difesa della sacralità dell’economia – che è lavoro del popolo – e contro quanti al denaro attribuiscono un demoniaco potere assoluto.

Pound era in prima fila, non faceva l’intellettuale ben ripagato e ben protetto, magari pronto a cambiare bandiera al primo vento contrario. Propagandava idee, lanciava fulmini e saette contro l’ingiustizia sociale e la speculazione, come un moderno Bernardino da Feltre ci metteva la faccia del predicatore intransigente e la parola infiammata del profeta che vede prossimo l’abisso. La sua condanna dell’usura e dell’usuraio ebbe aspetti di radicalismo medievale in piena guerra mondiale.

Quest’uomo vero fu pronto a pagare di persona, senza mai rinnegare una sola parola. Si esponeva senza remore. E parlava chiaro e forte. Come ad esempio in quella lettera – riportata da Colombo – indirizzata a don Calcagno (il sacerdote eresiarca fondatore di “Crociata Italica” durante la RSI e vicino a Farinacci) nell’ottobre 1944, in cui si scagliò contro la doppiezza vaticana di Pio XII: «Credete che un figlio d’usuraio, venduto e stipendiato, o indebitato agli ebrei sia la persona più adatta a “portare le anime a Cristo”? La Chiesa una volta condannava l’usura».

Ezra Pound non era un sognatore fuori dal mondo, e nemmeno un visionario ingenuo, come hanno cercato di farlo passare certi suoi non richiesti ammiratori antifascisti. Era un perfetto lettore della realtà e un geniale interprete dell’epoca in cui visse. Ebbe chiarissima davanti a sé l’entità della prova che si stava svolgendo con la Seconda guerra mondiale. Comprese come pochi che quella era la lotta decisiva fra l’usuraio e il contadino, e che difficilmente per il vinto ci sarebbe stata una rivincita. Quando la guerra piegò verso il trionfo degli usurai – allorché, come scrisse, «i fasci del littore sono spezzati» – partecipò fino in fondo all’esperienza tragica della Repubblica Sociale, consapevole di vivere, come dice Colombo, «l’età apocalittica della fine».

L’uomo europeo deve molto a Pound. Gli deve una grande passione ideale e una formidabile attrezzatura ideologica, che è grande poesia e a volte anche grande prosa. Proprio mentre l’usura universale sta facendo a pezzi un popolo dietro l’altro, proprio mentre infuria la volontà di scannare i popoli per arricchire piccole oligarchie di speculatori apolidi, quella di Pound appare come una gigantesca opera di profezia e di riscatto.

Tante altre notizie su www.ariannaeditrice.it

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ezra pound, théologie, tradition, philosophie, littérature, lettres, lettres américaines, littérature américaine |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 12 octobre 2011

Sortie du n°6 du Livr'arbitres

Sortie du n°6 du Livr'arbitres...

Rappel : A l'occasion de la sortie de ce nouveau numéro, la revue organise une soirée littéraire et amicale le mercredi 12 octobre à partir de 20 heures au bar le 15 vins, 1, rue Dante, 75005 Paris (cliquez ici).

Avec la participation (et les possibles dédicaces) de: Francis Bergeron, François Bousquet, Patrick Gofman, Michel Mourlet, Emmanuel Ratier, Joseph Vebret, Miège, Innocent....

16:10 Publié dans Revue | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : revue, littérature, lettres |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

This Difficult Individual Eustace Mullins—& the Remarkable Ezra Pound

This Difficult Individual Eustace Mullins—& the Remarkable Ezra Pound

By Beatrice Mott

Ex: http://www.toqonline.com/

Eustace Mullins

Earlier this year my friend Eustace Mullins passed away. He had been ailing for some time — at least since I first met him in 2006. Hopefully he is in a better place now.

Mr. Mullins made a huge mark on the nationalist community here in the United States, but also has a following in Europe and Japan. For those who have not read his books, Mr. Mullins attempted to expose the criminal syndicates that manipulate governments and the international financial system.

But Mr. Mullins’ most sparkling claim to fame was his partnership with Ezra Pound in order to write Secrets of the Federal Reserve — probably the most well-known exposé of how our government really works.

But nobody’s life is all sunshine and light. While Mr. Mullins’ work is among the most famous in the nationalist community, it is also some of the worst researched. He often fails to reference where he uncovered the material in his books. While Mr. Mullins was very perceptive of historical trends, his insights were sometimes overshadowed by unbalanced statements.

Authors wishing to quote Eustace’s books in their own writing make themselves an easy target for reasonable critics or hate organizations like the ADL. In this way, Mr. Mullins has done more harm to the movement than good.

I learned this the long way. Having read Secrets, I drove down to Staunton, VA in the summer of 2006 and spent an afternoon talking with Mr. Mullins. My goal was to find the origin of several stories and statements which I could not reference from the text. Mr. Mullins was an elderly gentleman and he couldn’t remember where he had found any of the material I was interested in. He simply replied: “It’s all in the Library of Congress. Back then they would let me wander the stacks.”

So I moved to D.C., a few blocks from the library and spent the better part of two years trying to retrace Mr. Mullins’ footsteps. Prior to this I had had several years’ experience as a researcher and was used to trying to find the proverbial “needle in a haystack.” They wouldn’t let me wander around the book storage facility (the stacks), but I scoured the catalog for anything that might contain the source for Mr. Mullins’ statements. I couldn’t verify any of the information in question.

Sadly, I realized that it would never be good practice to quote Mr. Mullins. But I hadn’t wasted the time. I know more about the Federal Reserve now than most people who work there and I learned about the fantastic Mr. Pound.

Ezra Pound is among the most remarkable men of the last 120 years. He made his name as a poet and guided W. B. Yeats, T.S. Elliot and E. Hemingway on their way to the Noble Prize (back when it meant something). He is the most brilliant founder of Modernism — a movement which sought to create art in a more precise and succinct form. Modernism can be seen as a natural reaction to the florid, heavy Victorian sensibility — it is not the meaningless abstractions we are assaulted with today.

Born in Idaho, Pound left the United States for Europe in 1908. In London he found an audience of educated people who appreciated his poetry. He married Dorothy Shakespear, a descendant of the playwright. Pound also befriended some of the most brilliant artists of the time and watched them butchered in the First World War.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska [1], a sculptor and one of Ezra’s best friends, was one of these sacrifices. The Great War changed Pound’s outlook on life — no longer content with his artistic endeavors alone, he wanted to find out why that war happened.

The answer he got bought him 12 years as a political prisoner in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Anacostia, just across the river from the Capitol in Washington D.C. Pound was never put on trial but was branded a traitor by the post-war American media.

The answer he got bought him 12 years as a political prisoner in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Anacostia, just across the river from the Capitol in Washington D.C. Pound was never put on trial but was branded a traitor by the post-war American media.

What answer did Pound find? Our wars begin and end at the instigation of the international financial houses. The bankers make money on fighting and rebuilding by controlling credit. They colonize nations and have no loyalty to their host countries’ youth or culture. No sacrifice is too great for their profit.

Much of Pound’s work chronicles the effect of this parasitic financial class on societies: from ancient China to modern-day Europe. Pound was a polyglot and scoured numerous (well-documented) sources for historical background. The education that Mullins’ work promises is delivered by the truckload in Pound’s writing. Pound often lists his sources at the end of his work — and they always check out.

Eustace Mullins got to know Pound during the poet’s time as a political prisoner. He was introduced to Pound by an art professor from Washington’s Institute of Contemporary Arts which, in Mullins’ words, “housed the sad remnants of the ‘avant-garde‘ in America.”

According to Mr. Mullins, Pound took to him and commissioned Eustace to carry on his work investigating the international financial system. Pound gave Eustace an American dollar bill and asked him to find out what “Federal Reserve” printed across its top meant. Secrets, many derivative books, and thousands of conspiracy websites have sprung from that federal reserve note.

And here is where the story goes sour. Pound was a feared political prisoner incarcerated because of what he said in Italy about America’s involvement with the international bankers and warmongering. Pound was watched twenty four hours a day and was under the supervision of Dr. Winfred Overholser, the superintendent of the hospital.

Overholser was employed by the Office of Strategic Services (the CIA’s forerunner) to test drugs for the personality-profiling program, what would be called MK-ULTRA. (See John Marks’ The Search for “the Manchurian Candidate”: The CIA and Mind-Control [2].) Personality profiling was St. Elizabeth’s bread and butter: The asylum was a natural ally to the agency.

Overholser was also a distinguished professor in the Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Department of George Washington University. This department provided students as test patients for the Frankfurt Schools’ personality profiling work, which the CIA was very interested in. Prophets of Deceit, first written by Leo Löwenthal [3] and Norbert Guterman in 1948, reads like a clumsy smear against Pound.

It does seem odd that a nationalist student would be allowed to continue the work of the dangerously brilliant Pound right under Winny’s nose. The story gets even stranger, as Mr. Mullins describes his stay in Washington during this time. He was housed at the Library of Congress — apparently he lived in one of the disused rooms in the Jefferson building and became good friends with Elizabeth Bishop [4].

Bishop was the Library of Congress’ “Consultant in Poetry” — quite a plum position. She was also identified by Frances Stonor Saunders as working with Nicolas Nabokov in Rio de Janeiro. Nabokov was paid by the CIA to handle South American-focused anti-Stalinist writers. (See The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters [5].) If what Saunders says is true, then it puts Eustace in strange company at that time of his life.

According to the CIA’s in-house historians, the Library was also a central focus for intelligence gathering [6] after the war, so it is doubly unlikely that just anybody would be allowed to poke around there after hours.

Whatever the motivation for letting Mullins in to see Pound was, the result has been that confusion, misinformation and unverifiable literature have clouded Pound’s message about the financial industry’s role in war. Fortunately Pound did plenty of his own writing.

According to Eustace, his relations with Pound’s relatives were strained after Pound’s release from prison. Pound moved back to Italy where he died in 1972. He was never the same after his stay with Overholser in St. E’s. The St. Elizabeth’s building is slated to become the new headquarters of the Department for Homeland Security [7].

Eustace went on to write many, many books about the abuses of government, big business and organized religion. They are very entertaining and are often insightful, but are arsenic from a researcher’s point of view. A book that contains interesting information without saying where the information came from is worse than no book at all.

While lackadaisical about references in his own writing, Mr. Mullins could be extremely perceptive and critical of the writing of others. I once told him how much respect I had for George Orwell’s daring to write 1984 — to which he sharply replied: “It’s a great piece of pro-government propaganda — they win in the end.” Mr. Mullins is of course right: Orwell’s Big Brother is always one step ahead, almost omniscient — and therefore invincible.

Eustace Mullins was much more than a writer. He became a political activist and befriended many prominent people in the American nationalist movement. But Mr. Mullins didn’t have much faith in American nationalism: It is a movement, he told me, that the government would never let go anywhere.

The Occidental Observer [8], March 20, 2010

00:05 Publié dans Economie, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : etats-unis, ezra pound, littérature, lettres, lettres américaines, littérature américaine, usure, usurocratie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 10 octobre 2011

Ignatius Royston Dunnachie Campbell: A Commemoration

Ignatius Royston Dunnachie Campbell:

A Commemoration

By Kensall Green

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

So much fine writing already exists here concerning Roy Campbell (October 2, 1901–April 22, 1957) that it would be hardly fair to Counter-Currents’ previous Campbell biographers to repeat—my own rephrasing notwithstanding—this poet’s life story once again. Let it simply stand that October 2, 2011 is Roy Campbell’s 110th birthday, and we remember him as poet, as a man of action, and as a heroic defender of the faith.

It is a mighty testament to his talent that his work and life are commemorated still, considering how much suppression his poetry — and therefore his very existence as a poet and hero — were subject to by the intellectual cabal of his day, and all the days since. He died, neck broken in an auto accident in Portugal, April 1957.

The following poems of Campbell both appeared in Sir Oswald Mosley’s BUF Quarterly magazine, published sometime between 1936 and 1940.

The Alcazar*

By Roy Campbell

The Rock of Faith, the thunder-blasted—

Eternity will hear it rise

With those who (Hell itself outlasted)

Will lift it with them to the skies!

‘Till whispered through the depths of Hell

The censored Miracle be known,

And flabbergasted fiends re-tell

How fiercer tortures than their own

By living faith were overthrown;

How mortals, thinned to ghastly pallor,

Gangrened and rotting to the bone,

With winged souls of Christian valour

Beyond Olympus or Valhalla

Can heave ten million tons of stone!

*In the summer of 1936, during the early part of the Spanish Civil War [2], Colonel José Moscardó Ituarte [3], and Spanish Nationalist Forces in support of General Franco, held a massive stone fortress, The Alcazar, against overwhelming Spanish Republican [4] forces. Despite being under continual bombardment, day and night, Col Moscardo and the Nationalists (reportedly nearly 1000 people—more than half of which were women) held out for two months.

The Fight

By Roy Campbell

One silver-white and one of scarlet hue,

Storm-hornets humming in the wind of death,

Two aeroplanes were fighting in the blue

Above our town; and if I held my breath,