“On ne commande pas aux âmes comme aux langues”, affirme Spinoza. C’est le langage qui définit une société et crée la cohésion au sein d’un peuple. Contrôler le langage est l’apanage de l’État, que ce soit un État créé dans un but utopique, démocratique ou totalitaire car le langage permet d’avoir accès au logos du peuple, et ainsi commander leurs « âmes ». Dans les Histoires florentines, Machiavel relève comment pour conditionner l’homme, toute politique doit nécessairement passer par la logique, en se tissant par le biais du langage. Continuant la même idée, Hobbes affirme que l’humain peut facilement être assujetti par un système langagier qui amalgame la peur et l’orgueil. Ainsi si l’État créé une situation de frayeur et de fierté simultanées, il créé en même temps un peuple obéissant qui de lui-même serait prêt à renoncer à ses droits pourvu qu’il ait l’impression, fausse certes, d’être en train de faire ou encore de dire ce qu’il faut.

Le contrôle utopique du discours

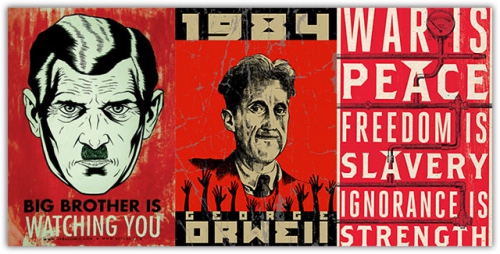

On peut penser que « contrôle utopique » est un genre d’oxymore qui met en parallèle deux idées contraires. Or, en nous basant sur le Kallipolis de Platon, nous voyons que tel n’est pas le cas. Comme dans un état dystopique, l’État utopique doit contrôler le langage pour contrôler le savoir du peuple. Dans La République, l’État est géré par un groupe de philosophes qui choisissent ce qui est bien pour la population en se donnant pour but le bien-être du peuple, au lieu du contrôle absolu qu’est le but avoué de Big Brother, mais la similitude entre les deux états est plus que dérangeante.

Par exemple pour créer les « guerriers » de l’État, Socrate établit les lois du discours qui doivent nécessairement être basées sur la vérité selon lui. Mais pour Socrate sa vérité est la seule qu’on puisse concevoir pour ne pas corrompre les jeunes esprits par le mensonge et la fiction. Il décide donc que pour la bonne gouvernance il faudrait bannir tout simplement certaines fables, et même les idées qui relèveraient du mensonge :

« … jamais dans un État qui doit avoir de bonnes lois, ni vieux ni jeunes ne doivent tenir ou entendre de pareils discours sous le voile de la fiction, soit en vers soit en prose, parce qu’ils sont impies, dangereux et absurdes. »

Dans les deux cas, utopie ou dystopie, c’est l’État qui détient le pouvoir de discerner entre le bien et le mal et dans les deux cas le libre arbitre individuel est sacrifié. Dans L’Orange mécanique d’Anthony Burgess nous voyons comment l’État en voulant réprimer ce qu’il considère mal, réprime le libre arbitre et de ce fait réprime l’homme aussi.

La Novlangue

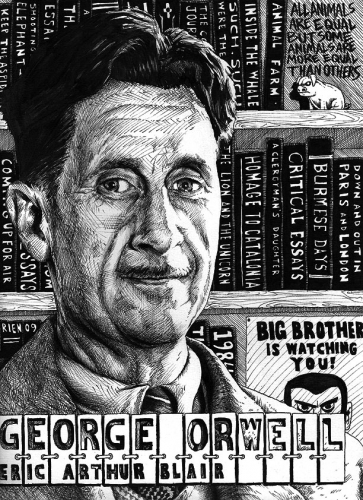

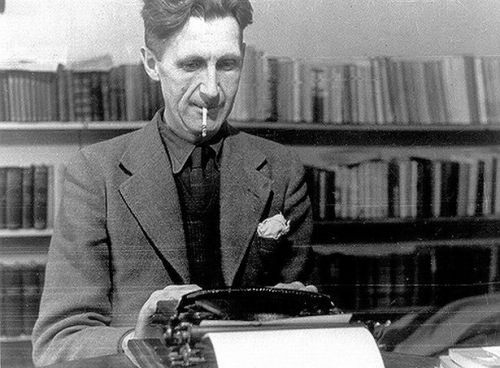

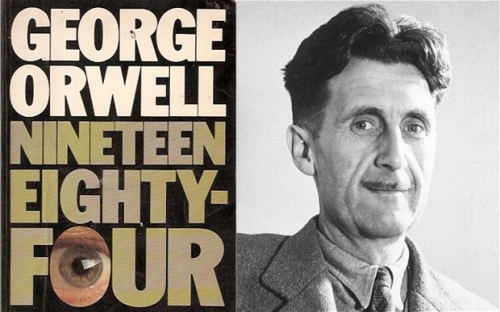

La Novlangue Le novlangue est la langue inventée par le Parti pour remplacer l’ancilangue à Océania. Le novlangue n’est pas traité uniquement dans la trame du roman, mais Orwell consacre également une partie importante au développement de cette langue dans son appendice. En 1984, le Novlangue est encore en mode décollage, même si le dictionnaire novlangue est à sa onzième édition et ce n’est qu’en 2050 qu’il effacera complètement l’ancilangue. Se rapprochant de l’hypothèse Sapir-Whorf, selon lequel c’est le langage qui détermine notre perception du monde et que chaque société, différente de par leur système linguistique, développe des pensées et des réflexions distinctes, Orwell dépeint un monde inconscient, manipulé par un système de langage élaboré. Dans son essai Politics and the English Language publié en 1945, Orwell émet déjà l’idée de la corrélation qui existe entre la langue et l’esprit. Le novlangue, pour le but du Parti, se développe donc en s’appauvrissant. Dans un premier temps, toute connotation associée aux mots est éliminée, puis on procède par éliminer les synonymes et les antonymes. La langue devient rigide, ne permettant aucune souplesse d’esprit, aucune émotion d’y traverser. La grammaire subit le même traitement. Tout était simplifié de telle façon à ce que la personne réfléchit le moins possible, ou ne réfléchit pas du tout.

Le novlangue a comme fin de sectionner la pensée en découpant la langue afin qu’il ne reste que des mots domestiques pour les robots de l’angsoc. De ce fait, il est planifié et instauré de manière à éliminer systématiquement, et plus efficacement que la torture, le crime par la pensée, et toute autre forme d’hérésie.

Le langage comme contrôle de la pensée

Pour Orwell, la situation politique reflète le langage et si l’un est corrompu, il s’ensuit que l’autre doit l’être aussi. S’appuyant sur les constructions de la langue anglaise, il démontre comment le langage est utilisé dans la politique pour créer une fausse impression de sécurité, pour rassurer le peuple à obéir sans réfléchir. L’Océania est continuellement en guerre. Cette guerre a deux buts. Premièrement de garder le peuple dans un État de frayeur et deuxièmement de faire de sorte que le peuple soit satisfait et même fier de cette guerre. De ce fait, au lieu de mettre l’emphase sur tous les manques, l’État utilise un langage hautement positif. L’emphase est mise sur les victoires, sur la capture des ennemis, sur des augmentations imaginaires et aucune mention n’est faite des bombardements continuels, sur la qualité de vie misérable ou sur la diminution permanente des ressources.

Dans Le Cru et le Cuit, Claude Lévi-Strauss démontre comment dans une région où la cuisson de la nourriture est inconnue, le peuple n’a pas de mot pour signifier le concept « cuit » et comme dans « la langue il n’y a que des différences», il ne possède pas de signifié pour désigner le concept « cru ». De la même façon, le novlangue éliminait toute idée de révolte en supprimant d’abord les mots et ensuite les concepts mêmes qui sont associés à ces mots :

« On remarqua qu’en abrégeant ainsi un mot, on restreignait et changeait subtilement sa signification, car on lui enlevait les associations qui, autrement, y étaient attachées. »

C’est le concept hégélien qui stipule qu’on ne peut penser ce qu’on ne peut dire. De même selon Boileau « ce qui se conçoit clairement s’exprime clairement et les mots pour le dire viennent aisément. » Ainsi donc, il faudrait retenir la conception anti-platonicienne et anti-idéaliste qui voudrait que les choses n’existent pas en dehors des mots qui servent à les designer.

Orwell relève aussi comment l’orthodoxie commande une certaine forme de répétition, tant et si bien que le langage ad absurdum résulte en un reductio ad absurdum de la logique. Dans 1984, les orateurs du Parti inculquent le même genre d’orthodoxie par leur jargon à la fois répétitif et inflammatoire. Dans ce système de répétition, les mots deviennent que des sons, du bruit qu’on émet à la gloire du Parti et ne véhiculant aucun sens à part bien-sûr la célébration du Parti. Ainsi les chansons accomplissent ce but à la perfection car elles permettent à la fois l’apprentissage par cœur sans réflexion et la scansion du Parti.

Inversion de la logique

« Le gros mensonge »

C’est par une manipulation psychologique élaborée que le Parti arrive à ses fins dans 1984, s’infiltrant subtilement dans le cerveau tant et si bien que la personne même ne se rencontre pas qu’elle a été lobotomisée. Inverser la logique de l’individu c’est changer sa perception de telle façon qu’il devient impossible à cette personne d’avoir un quelconque raisonnement approprié :

« Par manque de compréhension, ils restaient sains. Ils avalaient simplement tout, et ce qu’ils avalaient ne leur faisait aucun mal, car cela ne laissait en eux aucun résidu, exactement comme un grain de blé, qui passe dans le corps d’un oiseau sans être digéré. »

Dans Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler utilise le terme « Le Gros Mensonge ». Le gros mensonge est l’utilisation d’un mensonge, si grand, que personne ne croirait que quelqu’un puisse avoir eu l’audace d’avoir inventé une telle chose. Le public se laisse facilement manipuler par une voix autoritaire et au lieu de remettre en question la rhétorique étatique, ils préfèreront croire à n’importe quelle ineptie. « Big Brother », les termes ne sont pas anodins, représente ce parent qui veille sur eux, et crée dans leur esprit l’image de cette personne primordiale à leur sauvegarde. Les citoyens sont donc psychologiquement amputés de toute forme de rébellion. 1984, jouant sur les mots et la parole, crée un climat langagier envahissant où l’individu est amené à croire à tout ce que le parti proclame, même s’il détient des informations contraires. Par exemple, après avoir proclamé une diminution dans la ration de chocolat, le Parti annonce qu’il y a en effet une augmentation de ration et le peuple l’acclame sans se poser des questions.

La double pensée

Selon Philippe Breton, la manipulation consiste à construire une image du réel de telle façon qu’il a l’air d’être réel. Océania est un état délabré où les gens croient quand même à la richesse, où le peuple est courbé et malade mais croit quand même à la vigueur, où c’est la pénurie qui règne et les gens croient à l’abondance.

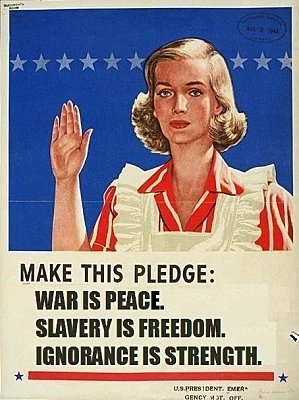

La double-pensée est un mot novlangue signifiant « contrôle de la réalité. » C’est le fait d’accepter deux idées opposées, simultanément et absolument. Elle est utilisée comme arme de manipulation psychologique de sorte que la personne soit incapable de penser par soi ou même de voir la contradiction dans leurs idées et accepter plus facilement les « gros mensonges ». Ce sont les mots qui permettent la contradiction, mais utilisées à perpétuité les contradictions deviennent admissibles, voire même analogues. Ainsi les slogans du Parti sont eux-mêmes construits sur les propos antinomiques :

« La guerre c’est la paix. La liberté c’est l’esclavage. L’ignorance c’est la force. »

De même, toutes les choses dégoûtantes sont décrites par des mots élogieux pour faire avaler la pilule à la population, par exemple la cigarette de la Victoire et le Gin de la victoire. Tout comme les noms des ministères : le ministère de la Paix s’emploie à faire la guerre, le ministère de la Vérité s’occupe des mensonges, le ministère de l’Amour se consacre à la torture, et le ministère de l’Abondance s’attèle à créer la famine. Le terme « canelangue » de même est insultant quand il est utilisé contre un opposant mais élogieux pour décrire un partisan. Et le mot « noirblanc », qui peut résumer le but machiavélique du parti et son système de double pensée, veut dire : faire croire à quelqu’un que le noir est blanc s’il est appliqué à un opposant mais signifie une croyance absolue dans le parti et ne pas seulement dire mais croire que le noir est blanc quand c’est voulu par ce dernier.

2+2=5

En 1939, Orwell écrit déjà qu’il est « possible qu’on arrive à une ère où deux et deux font cinq quand le dirigeant le voudra. » 1984 est essentiellement axé sur le contrôle psychologique de la personne. Même si la torture physique est présente, c’est le contrôle mental qui est la priorité du Parti. La manipulation mentale, qui passe principalement par le langage, est si subtilement distillée dans l’inconscient que la population ne se rend même pas compte de son endoctrinement. Même Julia qui se révolte contre le Parti ne pouvait avoir d’autre mémoire que celle du Parti.

« Dire de ce qui est que cela est, et dire de ce qui n’est pas que cela n’est pas, c’est dire la vérité » selon Aristote dans sa Métaphysique. De là découle l’idée que ce qui est vrai est réel. Or, la réalité de quelqu’un peut ne pas être partagée par un autre car l’imaginaire de chacun est différent. Mais dans 1984, le Parti travaille à ce que l’imaginaire soit le même pour tout le monde, la même réalité doit être partagée par tous et ainsi la même vérité sera détenue par tous.

Le Parti ne peut admettre que les gens puissent réfléchir par eux et procède donc à détruire toute logique chez la personne. Au début du roman, Winston écrit :

« La liberté, c’est la liberté de dire que deux et deux font quatre. Lorsque cela est accordé, le reste suit»

En détruisant même cette simple logique mathématique, le Parti détruit toute forme de réflexion et d’indépendance mentale. De sorte qu’il n’y a plus de réalité objective mais seulement la réalité à laquelle le Parti veut faire croire. Se basant sur le système de la double pensée, le Parti habitue la personne à accepter toute sorte d’incohérences. Pour soumettre la personne, il ne suffit pas de lui faire croire à une notion fallacieuse, mais de croire à ce que le Parti veut lui faire croire, et d’y croire seulement parce que le Parti lui demande de croire. C’est pour cela que 2+2 peut faire 3 si le Parti le veut. Cette croyance établie, même les personnes intelligentes comme Syme n’arrivent pas à voir hors la logique du Parti. Une fois guéri, Winston peut lui aussi accepter les dichotomies sans se questionner et finalement trace 2+2=5.

La propagande

Comme système totalitaire, Océania a recours à une propagande minutieuse pour endoctriner sa population. Elle passe par le bourrage de crâne, à instaurer la crainte, à modifier et contrôler les comportements de tout un chacun et surtout à changer et à recréer la connaissance.

Les enfants sont lobotomisés, comme dans La République de Platon où l’éducation de l’enfant est prise en charge pour ne pas le laisser corrompre par d’autres idées. Selon Bertrand Russell, une éducation autoritaire aide à créer des esclaves aussi bien que des despotes car la personne accepte l’idée que la seule relation possible entre deux personnes est une relation où l’un ordonne et l’autre obéi. L’association des Espions et de la Ligue de la jeunesse, à l’instar d’un certain Hitlerjugend, travaille à soumettre les enfants et les femmes, qui sont parmi les plus fervents adorateurs du parti. Tout comme le contrôle de l’acte sexuel, qui devient important pour un état totalitaire où la frustration sexuelle est dirigée vers le fanatisme. Dans les deux textes, les femmes sont instruites à avoir une répugnance pour le sexe qu’elles ne devaient accomplir que dans le but de la procréation.

Les phrases, les mots, et les images ne laissent aucun répit, aucune liberté. Par exemple les mots « facecrime » et « crime de la pensée » qui décrivent des crimes qu’on commet par ses expressions ou par sa pensée, c’est-à-dire si la personne n’a pas montré l’expression ou la pensée attendue de lui. En plus, la présence de la Police de la Pensée qui surveille les moindres gestes renforce cet état de terreur. Winston craint même qu’il puisse se trahir de dos ou dans son sommeil.

Il y a un vrai culte de la personnalité, emprunté au régime mussolinien, autour de Big Brother. À commencer par le terme affectueux « grand frère », les membres du parti ne doivent pas seulement vénérer mais aimer Big Brother. Ainsi les défilés dans les rues sont récurrents et chaque jour les membres sont soumis aux « Deux Minutes de la Haine ». La propagande pour être effectif joue sur l’affect de la personne. La figure de Goldstein créer par le Parti pour représenter l’ennemi est efficace car elle pousse la haine des membres à son paroxysme même Winston ne peut que se laisser emporter, et parallèlement accentue l’amour pour Big Brother.

La propagande est si réussie que Winston depuis le début ressent de l’amour envers O’Brien et même à la fin, quand ce dernier est en train de le torturer, il ne peut s’empêcher de l’admirer. Le but de la propagande de l’Océania est d’arriver justement à un amour inconditionnel à l’égard de Big Brother. Le Parti vise à posséder l’esprit de tout un chacun, l’endoctrinement absolu. Winston ne peut mourir tant que ses sentiments ne changent pas et de façon lugubre, pour montrer la victoire totale de Big Brother, le roman se termine par cette phrase en majuscule :

« Il AIMAIT BIG BROTHER »

Mutabilité de l’Histoire

Poussant à l’extrême la notion que ce sont les gagnants qui écrivent l’histoire, le Parti utilise ce concept pour ratifier l’Histoire de sorte à effacer la mémoire des personnes. Le Parti commence par détruire le passé, tout ce qui a trait aux souvenirs est irrémédiablement abattu et toute chose véhiculant un morceau d’Histoire est impérativement modifiée. Sans informations du passé, ou encore sans les moyens de comprendre ses informations, il ne serait même plus nécessaire de censurer l’Histoire hétérodoxe. La manipulation de la langue est utile dans ce qu’il n’affecte pas que le présent, mais a de l’emprise sur le passé aussi bien que le futur.

Winston Smith travaille au Ministère de la Vérité, dont le but est de propager le mensonge. Son travail consiste à changer l’histoire au fur et à mesure que les évènements changent. Le passé est rectifié, remanié et changé tant de fois que le passé même n’existe plus. Il est intéressant de noter que le tube dans lequel les informations désuètes sont jetées pour être oubliées s’appelle « trou de mémoire ». L’écriture-même qui est un acte de transcendance perd de sa fonction. Winston se demande pour qui et pourquoi il écrit un journal quand son seul sort est l’oubli.

Comme l’Histoire passe par le langage, il devient impératif de falsifier ou d’effacer les écrits pour changer le cours de l’histoire. Sans la mise en parole, la mémoire s’atrophie et s’efface. Et c’est à force d’altérer la mémoire que le Parti peut faire tout croire aux personnes car l’individu n’a plus d’ancrage dans le passé. Comme le Parti ne peut être infaillible, alors c’est la mémoire qui doit l’être. Winston se demande continuellement s’il n’est pas fou car « aujourd’hui, la folie était de croire que le passé était immuable.»

Le langage, seul vestige de la mémoire antérieure, doit être effacé et recréé à son tour. Après son premier acte de révolte, l’écriture, les souvenirs de Winston remontent à la surface par ses rêves et il se réveille en prononçant le mot « Shakespeare ». La littérature, surtout la littérature classique, fait partie de l’imaginaire collectif et ne peut que réveiller chez la personne idéologie et révolte. Pour établir et maintenir l’oligarchie, il faut être sûr que toute la littérature antique serait ensevelie et il ne suffira pas de les détruire tout simplement car les idées peuvent renaître. L’instauration du novlangue ferait le reste du travail et terminerait la destruction physique par la destruction mentale de ces œuvres car même s’ils ont échappé au pillage, ils n’auront plus de signification.

Réalité et constructivisme

Le contrôle de la vérité, ou sur ce qu’il veut établir comme vérité, permet au Parti de construire une réalité voulue. Se basant sur les données qu’il possède, qu’il pressent comme véridiques, puisque c’est prouvé par les documents, l’individu est amené à recréer sa réalité ou plutôt à accepter la réalité du Parti. Même Winston est amené à questionner la réalité à chaque fois et a des doutes sur sa réalité en l’opposant à la réalité que le Parti veut lui faire croire.

En psychologie, le terme dissonance cognitive renvoie à l’inconfort que ressent un humain quand il se trouve confronté à des idées contraires aux informations qu’il détient comme réalité. Un des buts du Parti est alors d’enlever cet inconfort de l’esprit des personnes pour qu’elles ne doutent plus. Et pour ce faire, il commence donc par effacer les données déjà établies dans leur esprit, et même jusqu’à dans leur imaginaire pour arriver à l’orthodoxie ultime.

L’un des plusieurs slogans du Parti stipule « Qui commande le passé commande l’avenir ; qui commande le présent commande le passé. » Se basant sur la théorie du constructivisme opposée à la réalité, le Parti met en avant l’idée que la connaissance des faits découle d’une construction exécutée par la personne. Selon Arthur Schopenhauer, tout ce qui est n’a de valeur que pour le sujet. Le Parti alors ne conserve que ce qui a de la valeur pour lui. Le reste est oublié et doit être oublié par tout le monde. La réalité est détruite et reconstruite selon les besoins du Parti. Par exemple O’Brien tente de convaincre Winston que sa réalité est fausse en lui montrant une copie de la photo que Winston avait jetée dans le trou de mémoire tout en lui demandant de croire que la photo n’existe pas.

Pour construire la réalité de tout un peuple, le Parti procède en détruisant la mémoire de tout un chacun et d’y mettre les souvenirs qu’il veut. Le cas de Winston semble alors très improbable dans ce système. Winston se demande à plusieurs reprises s’il est la seule personne à avoir une mémoire. O’Brien lui-même à un moment lui accorde qu’il est le dernier homme à s’en souvenir. Le livre d’horreur qu’est 1984, nous pousse à nous demander si même la révolte de Winston n’est pas manigancée du début à la fin. Le journal qui lui permet son premier pas vers l’anarchie a été acheté chez M. Charrington qui travaille pour la Police de la Pensée. C’est lui qui lui chante le premier morceau d’une chanson ancienne qui réveille ses souvenirs et c’est chez lui-même qu’il achète le bloc de corail qui agissant à un certain degré comme la madeleine de Proust, réveillant son inconscient. O’Brien lui avoue qu’il le surveille depuis sept ans. Winston Smith n’est alors qu’un rat dans un labyrinthe et la mémoire elle-même devient malléable dans la main du Parti qui la recréé et l’efface selon sa volonté.

Conclusion

Conclusion 1984 est classé premier dans les meilleures ventes sur Amazon et est actuellement le livre le plus vendu au monde. Sean Spicer, Directeur de la communication de la Maison-Blanche, pour l’inauguration présidentielle de Donald Trump annonça qu’il y avait pour cet évènement « le plus grand public jusque-là ». Défiée par les statistiques, Kellyanne Conway, porte-parole du nouveau Président américain, a dit que Sean Spicer se référait en fait à des « faits alternatifs », ayant ainsi recours aux mêmes procédés que l’État de l’Océania dans 1984. Le pouvoir sur les mots est souvent utilisé par les gouvernements pour maintenir la population dans un état inférieur, leur faisant croire ce qu’ils veulent. La falsification, l’exagération, la dramatisation sont autant de méthodes auxquelles l’État a recours pour manœuvrer la personne. Utilisés comme outil de manipulation et de propagande, les mots peuvent diriger toute la pensée d’un peuple. Que ce soit dans les États utopiques ou dystopiques, pour contrôler le peuple, un travail minutieux sur le langage est élaboré, car c’est à travers le langage qu’ils atteignent la pensée et peuvent diriger le peuple dans la direction qu’ils souhaitent. Ainsi ce n’est peut-être plus vers une utopie que nous devons nous tendre. Huxley dans son épigraphe pour le Meilleur des mondes cite Nicolas Berdiaeff : « … Les utopies sont réalisables. La vie marche vers les utopies. Et peut-être un siècle nouveau commence-t-il, un siècle où les intellectuels de la classe cultivée rêveront aux moyens d’éviter les utopies et de retourner à une société non-utopique, moins ‘parfaite’ et plus libre ».

Annexe : Présentation de 1984

1984 dépeint un monde d’après-guerre où seulement trois États dominent le monde : l’Eurasia, l’Estasia et l’Océania. Ces trois pouvoirs totalitaires contrôlent un monde dépourvu de toute liberté, et chacun de ces États ont leur propre philosophie : le Néo-Bolchévisme en l’Eurasia, le Culte de la Mort ou l’Oblitération du Moi en Estasia et l’Angsoc en Océania (socialisme anglais en novlangue). Il y a une guerre continuelle entre ces trois États qui sert leurs intérêts communs pour maintenir la dictature.

L’histoire est racontée par Winston Smith, un homme de 39 ans qui travaille au Ministère de la Vérité. Son travail consiste à ratifier les informations antérieures pour qu’elles soient à jour avec les communications actuelles du Parti. Il décrit le monde dans lequel il vit. Un monde détruit, géré par la propagande, la manipulation et la peur. La figure de Big Brother, leur leader, avec la phrase « Big Brother vous regarde », se trouve partout. En plus, les citoyens sont surveillés tout le temps grâce à des « télécrans » qu’ils n’ont pas le droit d’éteindre et par la Police de la Pensée qui surveille leurs moindres faits et gestes. Le peuple vit dans un état de fatigue et de manque qui le rend plus docile et facile à manipuler. Il n’y a plus de vie privée et les relations elles-mêmes sont factices car les enfants sont encouragés à dénoncer leurs parents et la sexualité devient taboue, pour gommer tout désir chez l’humain.

Winston, la seule personne qui est assez consciente pour se rendre compte de ce qui se passe, se révolte en commençant à écrire un journal pour noter ses pensées, qui vont à l’encontre de l’État. Il est hanté par le passé, par ses souvenirs et n’arrive pas à faire abstraction du passé, contrairement aux autres. En même temps il rêve de faire partie d’un groupe révolutionnaire, La Fraternité, mené par Goldstein, l’ennemi du Parti. Il veut s’associer à O’Brien, un membre du Parti qu’il pense faire partie de La Fraternité. Révolté par l’asexualité chez la femme, il s’éprend d’une femme Julia qui elle aussi se rebelle contre le Parti. Leur promiscuité devient un acte politique et voulant aller plus loin dans leur révolte même s’ils savent qu’ils risquent la torture et la mort, ils se joignent à O’Brien qui confirme l’idée de Winston, qu’en effet il est membre de la Fraternité.

Pour se voir aussi souvent qu’ils le veulent, Winston loua une chambre chez M. Charrington, un vieil antiquaire qui recèle encore quelques objets du passé, notamment le journal que Winston avait acheté, un presse-papier incrusté d’un corail qui deviendra un fétiche pour Winston et un tableau qu’il essaie de lui vendre. Entretemps O’Brien lui fait parvenir le livre de La Fraternité écrit par Goldstein lui-même après que Winston et Julia se sont dits prêts à tout, que ce soit le suicide ou le meurtre, pour servir le groupe.

Alors qu’ils sont dans la chambre de M. Charrington, Winston et Julia sont arrêtés et torturés. M. Charrington, membre actif de la Police de Pensée surveillait Winston pendant tout ce temps et le télécran caché à l’arrière du tableau avait tout enregistré. Winston découvre qu’O’Brien est loin d’être révolutionnaire et que le livre de Goldstein est écrit par le Parti lui-même pour chasser les criminels par la Pensée et vérifier l’orthodoxie du peuple.

On apprend que Julia s’est facilement rendue après la torture mais Winston prend plus de temps à être guéri croyant en une réalité objective. Peu à peu, avec l’accroissement dans la torture, Winston devient aussi lobotomisé que les autres et commence à croire que la réalité est seulement dans la tête. Mais le dernier faisceau de révolte est éteint quand Winston est forcé à renier son amour pour Julia, et ainsi la trahir. Ultime torture, réservée au détenus de la chambre 101, qui consiste à mettre l’humain en face de ses phobies et ainsi le forcer à se rendre complètement – une cage de rats sur son visage qui s’ouvrira sur l’ordre d’O’Brien pour lui dévorer le visage. La victoire est complète. Un Winston vaincu promène les routes en attendant la balle qui va le tuer, avec dans son cœur l’amour d’une seule personne : Big Brother.

Quraishiyah Durbarry

Sur l’auteur

Enseignante de formation, Quraishiyah Durbarry a publié plusieurs nouvelles et poèmes en français et en anglais dans diverses revues (Point Barre, Vents Alizés, Contemporary Poets…).

A été co-lauréate du « Prix Livre d’or – Romans 2011 », organisé par la Mairie de Quatre-Bornes (Ile Maurice) et présidé par Ananda Devi.

A publié un recueil de poèmes : Entre Désir et Mort (ISBN : 9782332471154) et un roman : Féminin Pluriel (Harmattan, ISBN : 978-2-336-00843-1)

Co-lauréate du prix d’écriture du festival Passe Portes et de l’Union européenne à Maurice en 2015 (pour la pièce L’Attrape-bête, mise en scène en 2016 pour le même festival et ayant recu le prix coup de coeur de Daniel Mesguish.)

Lauréate du prix d’écriture du festival Passe Portes et de l’Union européenne à Maurice en 2016 (pour la pièce Le Minotaure.), présidé par Bernard Faivre d’Arcier.

En cours de publication, Sandor Marai, Mémoire et Vérité

Bibliographie

Besnier Jean-Michel, Les Théories de la Connaissance, PUF, collection « Que sais-je ? », Paris, 2005.

Breton Philippe, Convaincre sans manipuler, La Découverte, 2015

Hobbes, Leviathan, Chapitre XIV Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus logico-philosophicus, 1921.

Festinger Leon, Une théorie de la dissonance cognitive, Enrick B. Editions, 2017.

George Orwell, 1984, Éditions Gallimard, (format Kindle), 2013.

Georges Orwell, Politics and the English Language, first published 1945, the Estate of the late Sonia Brownell Orwell, 1984 (format Kindle).

Lévi-Strauss Claude, Mythologiques 1 : Le cru et le cuit, Plon, Amazon Media EU S.à r.l. (format Kindle), 2014.

Platon, La République, traduction de Victor Cousin, Amazon Media EU S.à r.l. (format Kindle)

Russell Bertrand, Power: A New Social Analysis, Routledge, 2004.

Saussure Ferdinand, Cours de linguistique générale, Ed. Payot, 1964.

Spinoza, Traité théologico-politique, Chapitre XX.

Whorf Benjamin Lee, Language, thought, and Reality – Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf, MIT Press, 2nd Revised edition, 2012.

Sitographie

George Orwell, Review of Russell’sPower: A new social analysis, 1939

Observatoire B2V des Mémoires, Mémoire et émotion, Le rôle des émotions dans le fonctionnement de la mémoire, B2V 2013.

http://www.observatoireb2vdesmemoires.fr/les-memoires/la-... (consulté le 27.01.17).

Filmographie

Kellyanne Conway: Press Secretary Sean Spicer Gave ‘Alternative Facts’, 2017.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=2&v=VSrEE...

Two minutes of hate 1984, 2015

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0KeX5OZr0A4

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

To his credit, Ryan does not spend much ink on critical analyses of the various presentations. That would make for a very fat and dreary book. In nearly every instance he’d have to tell us that the production was uneven and woefully miscast. I wondered if he was going to carp about the misconceived film adaptation of Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1997; American title: A Merry War). Not a bit of it; he leaves it to us to do the carping and ridicule. What he does provide is a rich concordance of Orwell presentations over the years, with often amazing production notes, technical details, and contemporary press notices. And if you don’t care to get that far into weeds, George Orwell on Screen is still an indispensable guidebook, pointing you to all sorts of bio-documentaries and dramatizations you might never discover on your own. This is particularly true of the many (mostly) BBC docos produced forty or fifty years ago, where you find such delights as Malcolm Muggeridge and Cyril Connolly lying down in tall grass and trading tales about their late, great friend.

To his credit, Ryan does not spend much ink on critical analyses of the various presentations. That would make for a very fat and dreary book. In nearly every instance he’d have to tell us that the production was uneven and woefully miscast. I wondered if he was going to carp about the misconceived film adaptation of Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1997; American title: A Merry War). Not a bit of it; he leaves it to us to do the carping and ridicule. What he does provide is a rich concordance of Orwell presentations over the years, with often amazing production notes, technical details, and contemporary press notices. And if you don’t care to get that far into weeds, George Orwell on Screen is still an indispensable guidebook, pointing you to all sorts of bio-documentaries and dramatizations you might never discover on your own. This is particularly true of the many (mostly) BBC docos produced forty or fifty years ago, where you find such delights as Malcolm Muggeridge and Cyril Connolly lying down in tall grass and trading tales about their late, great friend.

d crib-note interpretation of O’Brien (“zealous Party leader . . . brutally ugly”), but pray consider: a) Connolly was Orwell’s only acquaintance of note who came close to the novel’s description of O’Brien, physically and socially; b) if you bother to read O’Brien’s monologues in the torture clinic, you see he’s doing a kind of Doc Rockwell routine: lots of fast-talking nonsense about power and punishment, signifying nothing.

d crib-note interpretation of O’Brien (“zealous Party leader . . . brutally ugly”), but pray consider: a) Connolly was Orwell’s only acquaintance of note who came close to the novel’s description of O’Brien, physically and socially; b) if you bother to read O’Brien’s monologues in the torture clinic, you see he’s doing a kind of Doc Rockwell routine: lots of fast-talking nonsense about power and punishment, signifying nothing. A good deal of Nineteen Eighty-Four, in fact, is a twisted retelling of Keep the Aspidistra Flying.

A good deal of Nineteen Eighty-Four, in fact, is a twisted retelling of Keep the Aspidistra Flying. To repeat the obvious, Burnham was describing Communism, not some theoretical “totalitarianism,” as in some press blurbs for Nineteen Eighty-Four. As noted, Orwell explicitly disavowed any connection between his fictional “Party” and the Communist one. Nevertheless, the political program that O’Brien boasts about to Winston Smith is the Communist program à la James Burnham. It’s exaggerated and comically histrionic, but strikes the proper febrile tone.

To repeat the obvious, Burnham was describing Communism, not some theoretical “totalitarianism,” as in some press blurbs for Nineteen Eighty-Four. As noted, Orwell explicitly disavowed any connection between his fictional “Party” and the Communist one. Nevertheless, the political program that O’Brien boasts about to Winston Smith is the Communist program à la James Burnham. It’s exaggerated and comically histrionic, but strikes the proper febrile tone. In March 1947, while getting ready to go to Jura and ride the Winston Smith book to the finish even if it killed him (which it did), Orwell wrote his long, penetrating review of The Struggle for the World. He paid some compliments, but also noted some subtle flaws in Burnham’s reasoning. Here he’s talking about Burnham’s willingness to contemplate a preventive war against the USSR:

In March 1947, while getting ready to go to Jura and ride the Winston Smith book to the finish even if it killed him (which it did), Orwell wrote his long, penetrating review of The Struggle for the World. He paid some compliments, but also noted some subtle flaws in Burnham’s reasoning. Here he’s talking about Burnham’s willingness to contemplate a preventive war against the USSR:

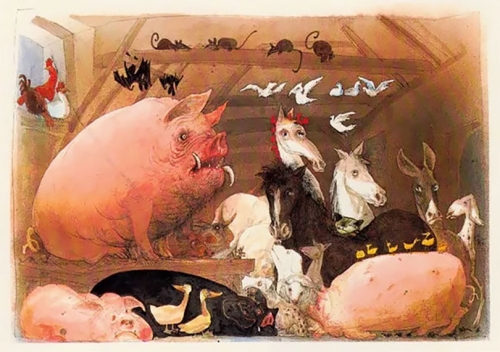

When Orwell finished Animal Farm in 1945, it was a very bad time to promote anti-Communist books with talking animals. This one was too clearly an allegory about the Bolshevik Revolution and the Stalinist aftermath, as subtle as a cow-pie (one barnyard feature that does not appear in the book). Over two dozen publishers rejected it promptly; Churchill’s coalition government had been touting a pro-Soviet line since 1941. Against this background, Animal Farm was about as welcome as a sympathetic book review of Mein Kampf (which Orwell did in fact once publish, during the Phony War period).

When Orwell finished Animal Farm in 1945, it was a very bad time to promote anti-Communist books with talking animals. This one was too clearly an allegory about the Bolshevik Revolution and the Stalinist aftermath, as subtle as a cow-pie (one barnyard feature that does not appear in the book). Over two dozen publishers rejected it promptly; Churchill’s coalition government had been touting a pro-Soviet line since 1941. Against this background, Animal Farm was about as welcome as a sympathetic book review of Mein Kampf (which Orwell did in fact once publish, during the Phony War period). But the use of pigs raises all sorts of other complications. All the male pigs but Napoleon, we are told, have been castrated. This fact is introduced late in the book, and rather obliquely: “Napoleon was the only boar on the farm.” But hold on: Napoleon has sired many porkers, presumably male often as not. Surely they’re still intact – some of them, anyway. Is Orwell just being forgetful, or does he fear certain distasteful matters will slow down the story?

But the use of pigs raises all sorts of other complications. All the male pigs but Napoleon, we are told, have been castrated. This fact is introduced late in the book, and rather obliquely: “Napoleon was the only boar on the farm.” But hold on: Napoleon has sired many porkers, presumably male often as not. Surely they’re still intact – some of them, anyway. Is Orwell just being forgetful, or does he fear certain distasteful matters will slow down the story?

Cinematographer Franz Lustig’s opening scenes confront even the most unsuspecting and ill-informed audience with the sight of an almost obliterated Hamburg filled with crumbling buildings. Raw footage shows, or at least intimates, that a deliberate and premeditated plan had achieved its desired effect of sending Germany back to the Stone Age. This plan, codenamed Operation Gomorrah, which was at the time the heaviest aerial assault ever undertaken, was later called “Germany’s Hiroshima” by British Bomber Command. Reel after reel offers shocking images: black-and white photo montages of the chaff-filled skies and the abhorrent results of the merciless firebombing that had raised a four-hundred-and-sixty-meter scorching-hot tornado that reached temperatures of up to eight hundred degrees Celsius, and swept over twenty-one square kilometers of the city. Carried out by Lancaster, Wellington, Stirling, and Halifax aircraft, their blockbuster bombs turned asphalt streets into rivers of flame, asphyxiating young and old alike in a sea of carbon monoxide, and as one eyewitness later recalled, it “sucked people like dry leaves into its molten heart.”

Cinematographer Franz Lustig’s opening scenes confront even the most unsuspecting and ill-informed audience with the sight of an almost obliterated Hamburg filled with crumbling buildings. Raw footage shows, or at least intimates, that a deliberate and premeditated plan had achieved its desired effect of sending Germany back to the Stone Age. This plan, codenamed Operation Gomorrah, which was at the time the heaviest aerial assault ever undertaken, was later called “Germany’s Hiroshima” by British Bomber Command. Reel after reel offers shocking images: black-and white photo montages of the chaff-filled skies and the abhorrent results of the merciless firebombing that had raised a four-hundred-and-sixty-meter scorching-hot tornado that reached temperatures of up to eight hundred degrees Celsius, and swept over twenty-one square kilometers of the city. Carried out by Lancaster, Wellington, Stirling, and Halifax aircraft, their blockbuster bombs turned asphalt streets into rivers of flame, asphyxiating young and old alike in a sea of carbon monoxide, and as one eyewitness later recalled, it “sucked people like dry leaves into its molten heart.” Stefan Lubert (Alexander Skarsgard), a widower, and his daughter Freda (Flora Thiemann), are the people whose palatial home Rachael has in effect invaded when it is requisitioned by the occupying forces to billet the Morgans. Rachael insists, “I want them out!”, which means in effect expelling them to the refugee camps. She also asks them difficult questions about a certain portrait that had only recently been removed from a place of honor over their fireplace and hurriedly replaced by another painting. These are petty acts of spiteful sadism that were no doubt common practice and openly endorsed by the non-fraternization code at that time, but in the context of the film’s narrative clearly signals more about Rachael’s own insecurities than it does about any misdemeanors or malicious intent on the part of those in whose home she resides.

Stefan Lubert (Alexander Skarsgard), a widower, and his daughter Freda (Flora Thiemann), are the people whose palatial home Rachael has in effect invaded when it is requisitioned by the occupying forces to billet the Morgans. Rachael insists, “I want them out!”, which means in effect expelling them to the refugee camps. She also asks them difficult questions about a certain portrait that had only recently been removed from a place of honor over their fireplace and hurriedly replaced by another painting. These are petty acts of spiteful sadism that were no doubt common practice and openly endorsed by the non-fraternization code at that time, but in the context of the film’s narrative clearly signals more about Rachael’s own insecurities than it does about any misdemeanors or malicious intent on the part of those in whose home she resides.

Mr. Wilson begins his “inquiry into the nature of the sickness of mankind in the twentieth century” at the effective point of the writers who have most influence in the present intellectual world. They are mostly good writers; they are not among the writers catering for those intellectuals who have every qualification except an intellect. They are good, some are very good: but at the end of it all what emerges? One of the best of these writers predicted that at the end of it all comes “the Russian man” described by Mr. Wilson as “a creature of nightmare who is no longer the homo sapiens, but an existentialist monster who rejects all thought”, As Hesse, the prophet of this coming, put it: “he is primeval matter, monstrous soul stuff. He cannot live in this form; he can only pass on”. The words “he can only pass on” seem the essence of the matter; this thinking is a chaos between two orders. At some point, if we are ever to regain sanity, we must regard again the first order before we can hope to win the second. It was a long way from Hellas to “the Russian man”; it may not be so far from the turmoil of these birth pangs to fresh creation. It is indeed well worth taking a look at the intellectual situation; where Europeans were, and where we are.

Mr. Wilson begins his “inquiry into the nature of the sickness of mankind in the twentieth century” at the effective point of the writers who have most influence in the present intellectual world. They are mostly good writers; they are not among the writers catering for those intellectuals who have every qualification except an intellect. They are good, some are very good: but at the end of it all what emerges? One of the best of these writers predicted that at the end of it all comes “the Russian man” described by Mr. Wilson as “a creature of nightmare who is no longer the homo sapiens, but an existentialist monster who rejects all thought”, As Hesse, the prophet of this coming, put it: “he is primeval matter, monstrous soul stuff. He cannot live in this form; he can only pass on”. The words “he can only pass on” seem the essence of the matter; this thinking is a chaos between two orders. At some point, if we are ever to regain sanity, we must regard again the first order before we can hope to win the second. It was a long way from Hellas to “the Russian man”; it may not be so far from the turmoil of these birth pangs to fresh creation. It is indeed well worth taking a look at the intellectual situation; where Europeans were, and where we are. This union of mind and will, of intellect and emotion in the classic Greek, this essential harmony of man and nature, this at-oneness of the human with the eternal spirit evoke the contrast of the living and the dying when set against the prevailing tendencies of modern literature. For, as Mr. Wilson puts it very acutely: when “misery will never end” is combined with “nothing is worth doing”, “the result is a kind of spiritual syphillis that can hardly stop short of death or insanity”. Yet such writers are not all “pre-occupied with sex, crime and disease”, treating of heroes who live in one room because, apparently, they dare not enter the world outside, and derive their little satisfaction of the universe from looking through a hole in the wall at a woman undressing in the next room. They are not all concerned like Dostoievsky’s “beetle man” with life “under the floor boards” (a study which should put none of us off reading him as far as the philosophy of the Grand Inquisitor and a certain very interesting conversation with the devil in the Brothers Karamazof, which Mr. Wilson rightly places very high in the world’s literature). Many of these writers of pessimism, of destruction and death have a considerable sense of beauty. Hesse’s remarkable Steppenwolf found his “life had become weariness” and he “wandered in a maze of unhappiness that led to the renunciation of nothingness”; but then “for months together my heart stood still between delight and stark sorrow to find how rich was the gallery of my life, and how thronged was the soul of wretched Steppenwolf with high eternal stars and constellations . . . this life of mine was noble. It came of high descent, and turned, not on trifles, but on the stars.” Mr. Wilson well comments that “stripped of its overblown language,” “this experience can be called the ultimately valid core of romanticism — a type of religious affirmation”. And in such writing we can still see a reflection of the romantic movement of the northern gothic world which Goethe strove to unite with the sunlit classic movement in the great synthesis of his Helena. But it ends generally in this literature with a retreat from life, a monastic detachment or suicide rather than advance into such a wider life fulfilment. The essence is that these people feel themselves inadequate to life; they feel even that to live at all is instantly to destroy whatever flickering light of beauty they hold within them. For instance De Lisle Adam’s hero Axel had a lady friend who shot at him “with two pistols at a distance of five yards, but missed him both times.” Yet even after this dramatic and perfect illustration of the modern sex relationship, they could not face life : “we have destroyed in our strange hearts the love of life . . . to live would only be a sacrilege against ourselves . . .” “They drink the goblet of poison together and die in ecstasy.” All of which is a pity for promising people, but, in any case, is preferable to the “beetle man”, “under the floor boards”, wall-peepers, et hoc genus omne, of burrowing fugitives; “Samson you cannot be too quick”, is a natural first reaction to them. Yet Mr. Wilson teaches us well not to laugh too easily, or too lightly to dismiss them; it is a serious matter. This is serious if it is the death of a civilisation; it is still more serious if it is not death but the pangs of a new birth. And, in any case, even the worst of them possess in some way the essential sensitivity which the philistine lacks. So we will not laugh at even the extremes of this system, or rather way of thinking; something may come out of it all, because at least they feel. But Mr. Wilson in turn should not smile too easily at the last “period of intense and healthy optimism that did not mind hard work and pedestrian logic.” He seems to regard the nineteenth century as a “childish world” which presaged “endless changes in human life” so that “man would go forward indefinitely on ‘stepping stones of his dead self’ to higher things.” He thinks that before we “condemn it for short-sightedness”, ” we survivors of two world wars and the atomic bomb” (at this point surely he outdoes the Victorians in easy optimism, for it is far from over yet) “would do well to remember that we are in the position of adults condemning children”. Why? — is optimism necessarily childish and pessimism necessarily adult? Sometimes this paralysed pessimism seems more like the condition of a shell-shocked child. Health can be the state of an adult and disease the condition of a child. Of course, if serious Victorians really believed in “the establishment of Utopia before the end of the century”, they were childish; reformist thinking of that degree is always childish in comparison with organic thinking. But there are explanations of the difference between the nineteenth and the twentieth century attitude, other than this distinction between childhood and manhood. Spengler said somewhere that the nineteenth century stood in relation to the twentieth century as the Athens of Pericles stood in relation to the Rome of Caesar. In his thesis this is not a distinction between youth and age — a young society does not reach senescence in so short a period — but the difference between an epoch which is dedicated to thought and an epoch which has temporarily discarded thought in favour of action, in the almost rhythmic alternation between the two states which his method of history observes. It may be that in this most decisive of all great periods of action the intellectual is really not thinking at all; he is just despairing. When he wakes up from his bad dream he may find a world created by action in which he can live, and can even think. Mr. Wilson will not quarrel with the able summary of his researches printed on the cover of his book : “it is the will that matters.” And he would therefore scarcely dispute the view just expressed; perhaps the paradox of Mr. Wilson in this period is that he is thinking. That thought might lead him through and far beyond the healthy “cowboy rodeo” of the Victorian philosophers in their sweating sunshine, on (not back) to the glittering light and shade of the Hellenic world — das Land der Griechen mit der Seele suchen — and even beyond it to the radiance of the zweite Hellas. Mr. Wilson does not seem yet to be fully seized of Hellenism, and seems still less aware of the more conscious way of European thinking that passes beyond Hellas to a clearer account of world purpose. He has evidently read a good deal of Goethe with whom such modern thinking effectively begins, and he is the first of the new generation to feel that admiration for Shaw which was bound to develop when thought returned. But he does not seem to be aware of any slowly emerging system of European thinking which has journeyed from Heraclitus to Goethe and on to Shaw, Ibsen and other modems, until with the aid of modern science and the new interpretation of history it begins to attain consciousness.

This union of mind and will, of intellect and emotion in the classic Greek, this essential harmony of man and nature, this at-oneness of the human with the eternal spirit evoke the contrast of the living and the dying when set against the prevailing tendencies of modern literature. For, as Mr. Wilson puts it very acutely: when “misery will never end” is combined with “nothing is worth doing”, “the result is a kind of spiritual syphillis that can hardly stop short of death or insanity”. Yet such writers are not all “pre-occupied with sex, crime and disease”, treating of heroes who live in one room because, apparently, they dare not enter the world outside, and derive their little satisfaction of the universe from looking through a hole in the wall at a woman undressing in the next room. They are not all concerned like Dostoievsky’s “beetle man” with life “under the floor boards” (a study which should put none of us off reading him as far as the philosophy of the Grand Inquisitor and a certain very interesting conversation with the devil in the Brothers Karamazof, which Mr. Wilson rightly places very high in the world’s literature). Many of these writers of pessimism, of destruction and death have a considerable sense of beauty. Hesse’s remarkable Steppenwolf found his “life had become weariness” and he “wandered in a maze of unhappiness that led to the renunciation of nothingness”; but then “for months together my heart stood still between delight and stark sorrow to find how rich was the gallery of my life, and how thronged was the soul of wretched Steppenwolf with high eternal stars and constellations . . . this life of mine was noble. It came of high descent, and turned, not on trifles, but on the stars.” Mr. Wilson well comments that “stripped of its overblown language,” “this experience can be called the ultimately valid core of romanticism — a type of religious affirmation”. And in such writing we can still see a reflection of the romantic movement of the northern gothic world which Goethe strove to unite with the sunlit classic movement in the great synthesis of his Helena. But it ends generally in this literature with a retreat from life, a monastic detachment or suicide rather than advance into such a wider life fulfilment. The essence is that these people feel themselves inadequate to life; they feel even that to live at all is instantly to destroy whatever flickering light of beauty they hold within them. For instance De Lisle Adam’s hero Axel had a lady friend who shot at him “with two pistols at a distance of five yards, but missed him both times.” Yet even after this dramatic and perfect illustration of the modern sex relationship, they could not face life : “we have destroyed in our strange hearts the love of life . . . to live would only be a sacrilege against ourselves . . .” “They drink the goblet of poison together and die in ecstasy.” All of which is a pity for promising people, but, in any case, is preferable to the “beetle man”, “under the floor boards”, wall-peepers, et hoc genus omne, of burrowing fugitives; “Samson you cannot be too quick”, is a natural first reaction to them. Yet Mr. Wilson teaches us well not to laugh too easily, or too lightly to dismiss them; it is a serious matter. This is serious if it is the death of a civilisation; it is still more serious if it is not death but the pangs of a new birth. And, in any case, even the worst of them possess in some way the essential sensitivity which the philistine lacks. So we will not laugh at even the extremes of this system, or rather way of thinking; something may come out of it all, because at least they feel. But Mr. Wilson in turn should not smile too easily at the last “period of intense and healthy optimism that did not mind hard work and pedestrian logic.” He seems to regard the nineteenth century as a “childish world” which presaged “endless changes in human life” so that “man would go forward indefinitely on ‘stepping stones of his dead self’ to higher things.” He thinks that before we “condemn it for short-sightedness”, ” we survivors of two world wars and the atomic bomb” (at this point surely he outdoes the Victorians in easy optimism, for it is far from over yet) “would do well to remember that we are in the position of adults condemning children”. Why? — is optimism necessarily childish and pessimism necessarily adult? Sometimes this paralysed pessimism seems more like the condition of a shell-shocked child. Health can be the state of an adult and disease the condition of a child. Of course, if serious Victorians really believed in “the establishment of Utopia before the end of the century”, they were childish; reformist thinking of that degree is always childish in comparison with organic thinking. But there are explanations of the difference between the nineteenth and the twentieth century attitude, other than this distinction between childhood and manhood. Spengler said somewhere that the nineteenth century stood in relation to the twentieth century as the Athens of Pericles stood in relation to the Rome of Caesar. In his thesis this is not a distinction between youth and age — a young society does not reach senescence in so short a period — but the difference between an epoch which is dedicated to thought and an epoch which has temporarily discarded thought in favour of action, in the almost rhythmic alternation between the two states which his method of history observes. It may be that in this most decisive of all great periods of action the intellectual is really not thinking at all; he is just despairing. When he wakes up from his bad dream he may find a world created by action in which he can live, and can even think. Mr. Wilson will not quarrel with the able summary of his researches printed on the cover of his book : “it is the will that matters.” And he would therefore scarcely dispute the view just expressed; perhaps the paradox of Mr. Wilson in this period is that he is thinking. That thought might lead him through and far beyond the healthy “cowboy rodeo” of the Victorian philosophers in their sweating sunshine, on (not back) to the glittering light and shade of the Hellenic world — das Land der Griechen mit der Seele suchen — and even beyond it to the radiance of the zweite Hellas. Mr. Wilson does not seem yet to be fully seized of Hellenism, and seems still less aware of the more conscious way of European thinking that passes beyond Hellas to a clearer account of world purpose. He has evidently read a good deal of Goethe with whom such modern thinking effectively begins, and he is the first of the new generation to feel that admiration for Shaw which was bound to develop when thought returned. But he does not seem to be aware of any slowly emerging system of European thinking which has journeyed from Heraclitus to Goethe and on to Shaw, Ibsen and other modems, until with the aid of modern science and the new interpretation of history it begins to attain consciousness. He is acute at one point in observing the contrasts between the life joy of the Greeks and the moments when their art is “full of the consciousness of death and its inevitability”. But he still apparently regards them as “healthy, once born, optimists,” not far removed from the modern bourgeois who also realises that life is precarious. He apparently thinks they did not share with the Outsider the knowledge that an “exceptional sense of life’s precariousness” can be “a hopeful means to increase his toughness”. The Greeks, of course, had not the advantage of reading Mr. Toynbee’s Study of History, which does not appear on a reasonably careful reading to be mentioned in Mr. Wilson’s book.

He is acute at one point in observing the contrasts between the life joy of the Greeks and the moments when their art is “full of the consciousness of death and its inevitability”. But he still apparently regards them as “healthy, once born, optimists,” not far removed from the modern bourgeois who also realises that life is precarious. He apparently thinks they did not share with the Outsider the knowledge that an “exceptional sense of life’s precariousness” can be “a hopeful means to increase his toughness”. The Greeks, of course, had not the advantage of reading Mr. Toynbee’s Study of History, which does not appear on a reasonably careful reading to be mentioned in Mr. Wilson’s book. But Mr. Wilson moves far beyond Sartre in regarding the thinkers of an earlier period; notably Blake. At this point he recovers direction. The reader will find pages 225 to 250 among the most important of this book, but he must read the whole work for himself; this review is a commentary and an addendum, not a précis for the idle, nor a primer for those who find anything serious too difficult. The author advances a long way when he considers Blake’s “skeleton key” to a solution for those who “mistake their own stagnation for the world’s”. Here we reach realisation that the “crises of’living demand the active co-operation of intellect, emotions, body on equal terms”; contact is made here with Goethe’s Ganzheit, although it is not mentioned. “Energy is eternal delight” takes us a long way clear o the damp caverns of neo-existentialism and

But Mr. Wilson moves far beyond Sartre in regarding the thinkers of an earlier period; notably Blake. At this point he recovers direction. The reader will find pages 225 to 250 among the most important of this book, but he must read the whole work for himself; this review is a commentary and an addendum, not a précis for the idle, nor a primer for those who find anything serious too difficult. The author advances a long way when he considers Blake’s “skeleton key” to a solution for those who “mistake their own stagnation for the world’s”. Here we reach realisation that the “crises of’living demand the active co-operation of intellect, emotions, body on equal terms”; contact is made here with Goethe’s Ganzheit, although it is not mentioned. “Energy is eternal delight” takes us a long way clear o the damp caverns of neo-existentialism and No men ever had a deeper sense of the human tragedy than the Greeks; none ever faced it with such brilliant bravery or understood so well not only the art of grasping the fleeting, ecstatic moment, but of turning even despair to the enhancement of beauty. Living was yet great; they understood dennoch preisen; they did not “leave living to their servants”. Mr. Wilson in quoting Aristotle in the same sense as the above lines of Sophocles — “not to be born is the best thing, and death is better than life” — holds that “this view” lies at one extreme of religion, and that “the other extreme is vitalism”. He does not seem at this point fully to understand that the extremes in the Hellenic nature can be not contradictory but complementary, or interacting. The polarity of Greek thought was closely observed and finely interpreted by Nietzsche in diverse ways. But it was left to Goethe to express the more conscious thought beyond polarity in his Faust: the Prologue in Heaven:

No men ever had a deeper sense of the human tragedy than the Greeks; none ever faced it with such brilliant bravery or understood so well not only the art of grasping the fleeting, ecstatic moment, but of turning even despair to the enhancement of beauty. Living was yet great; they understood dennoch preisen; they did not “leave living to their servants”. Mr. Wilson in quoting Aristotle in the same sense as the above lines of Sophocles — “not to be born is the best thing, and death is better than life” — holds that “this view” lies at one extreme of religion, and that “the other extreme is vitalism”. He does not seem at this point fully to understand that the extremes in the Hellenic nature can be not contradictory but complementary, or interacting. The polarity of Greek thought was closely observed and finely interpreted by Nietzsche in diverse ways. But it was left to Goethe to express the more conscious thought beyond polarity in his Faust: the Prologue in Heaven: May we end with a few questions based on that doctrine of higher forms which has found some expression in this Journal and in previous writings? Is it not now possible to observe with reason and as something approaching a clearly defined whole, what has hitherto only been revealed in fitful glimpses to the visionary? What are the means of observation available to those who are not blessed with the revelation of vision? Are they not the thoughts of great minds which have observed the working of the divine in nature and the researches of modern science which appear largely to confirm them?

May we end with a few questions based on that doctrine of higher forms which has found some expression in this Journal and in previous writings? Is it not now possible to observe with reason and as something approaching a clearly defined whole, what has hitherto only been revealed in fitful glimpses to the visionary? What are the means of observation available to those who are not blessed with the revelation of vision? Are they not the thoughts of great minds which have observed the working of the divine in nature and the researches of modern science which appear largely to confirm them? At some point the spirit, the soul — call it what you will — is ignited by some spark of the divine and moves without necessity; yet, again it is a matter of common observation that this only occurs in very advanced types. In general it is only the “challenge” of adverse circumstance which evokes the “response” of movement to a higher state. Goethe expressed this thought very clearly in Faust by his concept of evil’s relationship to good; he also indicated the type where the conscious striving of the aspiring spirit replaces the urge of suffering in the final attainment of salvation: wer immer strebend sich bemüht, den können wir erlösen. In the early stages of the great striving all suffering, and later all beauty must be experienced and sensed; but to no moment of ecstasy can man say, verweile doch, du bist so schön until the final passing to an infinity of beauty at present beyond man’s ken. Complacency, at any point, is certainly excluded. So must it be always in a creed which begins effectively with Heraclitus and now pervades modern vitalism. The philosophy of the “ever living fire”, of the ewig werdende could never be associated with complacency. Still less can the more conscious doctrine of higher forms co-exist with the static, or with the illusory perfections of a facile reformism. Man began very small, and has become not so small; he must end very great, or cease to be. That is the essence of the matter. Is it true? This is a question which everyone must answer for himself after studying European literature which stretches from the Greeks to the vital thought of modern times and, also, the world thinking of many different climes and ages which in many ways and at most diverse points is strangely related. He should study, too, either directly or through the agency of those most competent to judge, the evolutionary processes revealed so relatively recently by modern biology and the apparently ever increasing concept of ordered complexity in modern physics. He must then answer two questions: the first is whether it is more likely than not that a purpose exists in life? — the second is whether despite all failures and obscurities the only discernable purpose is a movement from lower to higher forms? If he comes at length to a conclusion which answers both these questions with a considered affirmative, he has reached the point of the great affirmation. The new religious impulse which so many seek is really already here. We need neither prophets nor priests to find it for ourselves, although we are not the enemies but the friends of those who do. For ourselves we can find in the thought of the world the faith and the service of the conscious and sentient man.

At some point the spirit, the soul — call it what you will — is ignited by some spark of the divine and moves without necessity; yet, again it is a matter of common observation that this only occurs in very advanced types. In general it is only the “challenge” of adverse circumstance which evokes the “response” of movement to a higher state. Goethe expressed this thought very clearly in Faust by his concept of evil’s relationship to good; he also indicated the type where the conscious striving of the aspiring spirit replaces the urge of suffering in the final attainment of salvation: wer immer strebend sich bemüht, den können wir erlösen. In the early stages of the great striving all suffering, and later all beauty must be experienced and sensed; but to no moment of ecstasy can man say, verweile doch, du bist so schön until the final passing to an infinity of beauty at present beyond man’s ken. Complacency, at any point, is certainly excluded. So must it be always in a creed which begins effectively with Heraclitus and now pervades modern vitalism. The philosophy of the “ever living fire”, of the ewig werdende could never be associated with complacency. Still less can the more conscious doctrine of higher forms co-exist with the static, or with the illusory perfections of a facile reformism. Man began very small, and has become not so small; he must end very great, or cease to be. That is the essence of the matter. Is it true? This is a question which everyone must answer for himself after studying European literature which stretches from the Greeks to the vital thought of modern times and, also, the world thinking of many different climes and ages which in many ways and at most diverse points is strangely related. He should study, too, either directly or through the agency of those most competent to judge, the evolutionary processes revealed so relatively recently by modern biology and the apparently ever increasing concept of ordered complexity in modern physics. He must then answer two questions: the first is whether it is more likely than not that a purpose exists in life? — the second is whether despite all failures and obscurities the only discernable purpose is a movement from lower to higher forms? If he comes at length to a conclusion which answers both these questions with a considered affirmative, he has reached the point of the great affirmation. The new religious impulse which so many seek is really already here. We need neither prophets nor priests to find it for ourselves, although we are not the enemies but the friends of those who do. For ourselves we can find in the thought of the world the faith and the service of the conscious and sentient man.

Naipaul had a unique background. He was of Hindu Indian origins and grew up in the British Empire’s West Indian colony of Trinidad and Tobago. Naipaul wrote darkly of his region of birth, stating, “History is built around achievement and creation; and nothing was created in the West Indies.”

Naipaul had a unique background. He was of Hindu Indian origins and grew up in the British Empire’s West Indian colony of Trinidad and Tobago. Naipaul wrote darkly of his region of birth, stating, “History is built around achievement and creation; and nothing was created in the West Indies.” The arrival of Islam to the Sind is the disaster which keeps on giving.

The arrival of Islam to the Sind is the disaster which keeps on giving.

The Kalevala was first published in 1835, but the tales therein date back to antiquity and were handed down orally. The poems were originally songs, all sung in trochaic tetrameter (now known as the “Kalevala meter”). This oral tradition began to decline after the Reformation and the suppression of paganism by the Lutheran Church. It is largely due to the efforts of collectors like Lönnrot that Finnish folklore has survived.

The Kalevala was first published in 1835, but the tales therein date back to antiquity and were handed down orally. The poems were originally songs, all sung in trochaic tetrameter (now known as the “Kalevala meter”). This oral tradition began to decline after the Reformation and the suppression of paganism by the Lutheran Church. It is largely due to the efforts of collectors like Lönnrot that Finnish folklore has survived.

Le communisme a facilement chuté partout finalement mais il a été remplacé parce que Debord nomme le spectaculaire intégré. Tocqueville déjà disait « qu’en démocratie on laisse le corps pour s’attaquer à l’âme. »

Le communisme a facilement chuté partout finalement mais il a été remplacé parce que Debord nomme le spectaculaire intégré. Tocqueville déjà disait « qu’en démocratie on laisse le corps pour s’attaquer à l’âme. » La surpopulation américaine menacera la démocratie américaine (triplement en un siècle ! La France a crû de 40% en cinquante ans) :

La surpopulation américaine menacera la démocratie américaine (triplement en un siècle ! La France a crû de 40% en cinquante ans) : Dix ans avant Umberto Eco (voyez mon livre sur Internet), Huxley annonce un nouveau moyen âge, pas celui de Guénon bien sûr, celui de Le Goff plutôt :

Dix ans avant Umberto Eco (voyez mon livre sur Internet), Huxley annonce un nouveau moyen âge, pas celui de Guénon bien sûr, celui de Le Goff plutôt : Huxley n’est pas très optimise non plus sur l’avenir des enfants mués en de la chair à télé :

Huxley n’est pas très optimise non plus sur l’avenir des enfants mués en de la chair à télé : Quant au futur, no comment :

Quant au futur, no comment : Dans son maigre énoncé des solutions (il n’en a pas), Huxley évoque alors la prison sans barreau (the painless concentration camp, expression mise en doute par certains pro-systèmes !) :

Dans son maigre énoncé des solutions (il n’en a pas), Huxley évoque alors la prison sans barreau (the painless concentration camp, expression mise en doute par certains pro-systèmes !) :

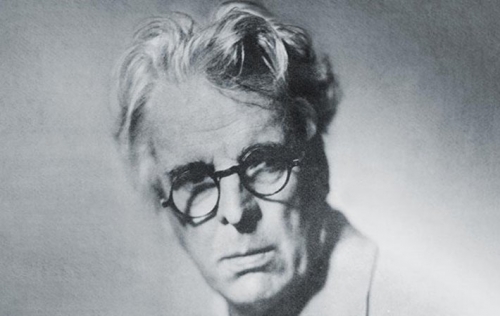

Despite cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as an artist as well as a man.

Despite cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as an artist as well as a man. Despite some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions made to the arts. Despite his

Despite some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions made to the arts. Despite his

En manipulant les archives, l’on manipule les consciences. Il suffit pour cela de « rectifier » le passé en l’alignant sur les nécessités politiques de l’heure. Si d’aventure il arrive que la mémoire individuelle contredise la mémoire collective ainsi façonnée, la contradiction doit être résolue au profit de la seconde par l’élimination de la première. D’où l’utilité de la « double pensée » pour assurer le triomphe de l’orthodoxie. Il n’y a plus ni réalité ni objectivité. Selon les termes même d’O’Brien, « la réalité n’est pas extérieure. La réalité existe dans l’esprit humain et nulle part ailleurs... Tout ce que le parti tient pour la vérité est la vérité ». Par cette perversion totale de l’histoire et de la conscience historique, on atteint le point extrême de la logique totalitaire.

En manipulant les archives, l’on manipule les consciences. Il suffit pour cela de « rectifier » le passé en l’alignant sur les nécessités politiques de l’heure. Si d’aventure il arrive que la mémoire individuelle contredise la mémoire collective ainsi façonnée, la contradiction doit être résolue au profit de la seconde par l’élimination de la première. D’où l’utilité de la « double pensée » pour assurer le triomphe de l’orthodoxie. Il n’y a plus ni réalité ni objectivité. Selon les termes même d’O’Brien, « la réalité n’est pas extérieure. La réalité existe dans l’esprit humain et nulle part ailleurs... Tout ce que le parti tient pour la vérité est la vérité ». Par cette perversion totale de l’histoire et de la conscience historique, on atteint le point extrême de la logique totalitaire.

News of Seth’s victory reaches London where Basil Seal, the ne’er-do-well son of the Conservative Whip and a classmate of Seth’s at Oxford, is recovering from a series of scandalous benders that have forced him to abandon his nascent political career. Desperately in need of money, Seal travels to Azania as a free-lance journalist. Within a short time of his arrival, Basil becomes Seth’s most trusted adviser and is put in charge of the Ministry of Modernization; in effect, Basil has become the real ruler of Azania since Seth spends his time immersed in catalogs and dreaming up more and more ridiculous “progressive” schemes for the betterment of Azanians, such as requiring all citizens to learn Esperanto. The natives who run the other departments are all too happy to refer all business to Basil.

News of Seth’s victory reaches London where Basil Seal, the ne’er-do-well son of the Conservative Whip and a classmate of Seth’s at Oxford, is recovering from a series of scandalous benders that have forced him to abandon his nascent political career. Desperately in need of money, Seal travels to Azania as a free-lance journalist. Within a short time of his arrival, Basil becomes Seth’s most trusted adviser and is put in charge of the Ministry of Modernization; in effect, Basil has become the real ruler of Azania since Seth spends his time immersed in catalogs and dreaming up more and more ridiculous “progressive” schemes for the betterment of Azanians, such as requiring all citizens to learn Esperanto. The natives who run the other departments are all too happy to refer all business to Basil.