Par Gérard Dussouy

Ex: http://www.leblancetlenoir.com

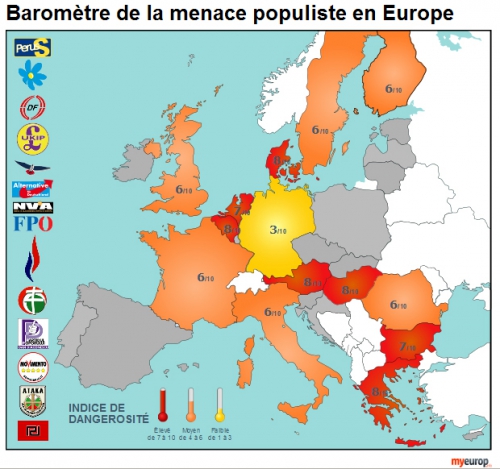

Face au changement mondial qui, avec ses perturbations de toutes natures (et qui n’ont rien à voir avec on ne sait quelle « main invisible », maléfique en l’occurrence), précipite les nations européennes dans un profond déclin, jusqu’à saper les bases de la civilisation européenne, les classes politiques au pouvoir persistent dans leurs errements suicidaires pour leurs peuples, en termes d’identité, d’emploi, ou d’indépendance. Quant aux divers mouvements populistes qui, en réaction, émergent un peu partout en Europe, ils ne perçoivent pas d’autre issue que celle d’un repliement, national ou régional, frappé d’une impuissance mortelle.

En effet, le vrai niveau de la lutte politique, parce que le seul où elle peut être efficace, est aujourd’hui continental. En premier lieu, il se situe au cœur même de l’Union européenne dont il est urgent que les peuples européens se la réapproprient en écartant la caste idéologique et technocratique qui la dirige.

Changer les formes pour sauver le fonds. Il faut comprendre, une fois pour toutes, que si l’on veut sauver ou préserver le fonds, à savoir la civilisation européenne avec son substrat humain (ses nations ancestrales), il faut, d’une part, rompre avec la logique libérale et purement mercantile imposée par les Etats-Unis depuis l’effondrement de l’Union soviétique, et, d’autre part, pour s’adapter aux réalités du monde, savoir changer les formes politiques, c’est à dire les institutions étatiques périmées. Compte tenu des bouleversements qui n’ont fait que commencer, et des périls grandissants, que chacun saisit désormais au quotidien, l’européisme rassembleur et offensif est à l’ordre du jour.

Maintenant que la construction libérale de l’Europe est à l’agonie, et que les Etats nationaux étalent leurs incapacités respectives dans la nouvelle distribution mondiale de la puissance (en particulier dans le champ de la démographie-question centrale du 21ème siècle), il est plus que jamais indispensable de réunir les dernières forces vives nationales dans le même Etat européen, et d’arrêter des stratégies unitaires tous azimuts.

L’incapacité des partis de gouvernement à changer leur vision du monde.

Avant tout parce qu’elles y trouvent leur intérêt financier, mais en raison, aussi, du formatage idéologique dont nos sociétés sont l’objet (facilité par une inculture historique généralisée) les élites dirigeantes des Etats européens s’accrochent à leurs croyances. Elles ne veulent pas admettre que leurs valeurs ne sont pas universelles, mais qu’elles sont contingentes d’une ère qui s’achève, celle de la modernité occidentale. Elles n’entendent pas mettre en cause les dogmes de la métaphysique des Lumières que sont : l’identification de la vérité (!) à l’universel, la conviction que la raison annihile les prédéterminations, l’unité du genre humain et la perfectibilité de l’homme, le développement économique et l’enrichissement mutuel grâce au libre-échange. Parce que cela leur sied, moralement et matériellement. Alors que tout ce que l’on observe concourt à contester le maintien d’une telle rhétorique.

Une idéologie néfaste. Aussi bien la connaissance que l’expérience de la diversité, d’un côté, que les conséquences malheureuses de la mondialisation pour des pans entiers de la société, d’un autre, ont rendu cette rhétorique illusoire et dangereuse. Mais nos élites inhibées ne veulent pas l’admettre. De plus, à force d’avoir voulu séparer la culture de la nature, en surestimant la première pour dénigrer la seconde, elles ne peuvent pas comprendre que les idées occidentales n’ont mené l’humanité, sans jamais réussir à la convertir à leurs croyances, que tant qu’elles ont été portées par une infrastructure humaine et matérielle dynamique. Or, ce n’est plus du tout le cas. Maintenant, compte tenu du bouleversement des rapports de force mondiaux, culturels inclus, l’aspiration à une société humaine universelle signifie la fin de la civilisation européenne.

Une idéologie néfaste. Aussi bien la connaissance que l’expérience de la diversité, d’un côté, que les conséquences malheureuses de la mondialisation pour des pans entiers de la société, d’un autre, ont rendu cette rhétorique illusoire et dangereuse. Mais nos élites inhibées ne veulent pas l’admettre. De plus, à force d’avoir voulu séparer la culture de la nature, en surestimant la première pour dénigrer la seconde, elles ne peuvent pas comprendre que les idées occidentales n’ont mené l’humanité, sans jamais réussir à la convertir à leurs croyances, que tant qu’elles ont été portées par une infrastructure humaine et matérielle dynamique. Or, ce n’est plus du tout le cas. Maintenant, compte tenu du bouleversement des rapports de force mondiaux, culturels inclus, l’aspiration à une société humaine universelle signifie la fin de la civilisation européenne.

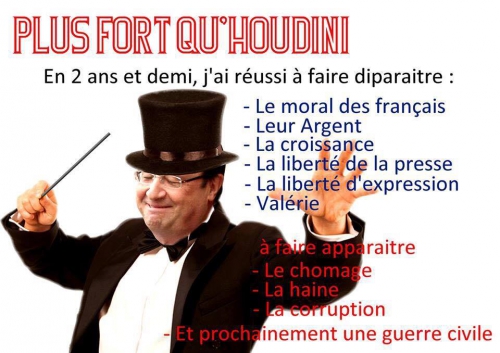

Outre son parti-pris idéologique, le problème de la classe politique européenne est qu’elle est obsédée par le souci de la croissance économique ou, ce qui revient au même dans nombre de pays européens, par la crise qu’elle-même a contribué à créer en avalisant le libre-échange avec les pays à bas salaires. Elle n’a jamais voulu légiférer pour faire en sorte que les grandes compagnies privilégient l’investissement dans l’espace européen. Il en va ainsi parce que l’idéologie basique libérale, à savoir la primauté de l’enrichissement individuel, a vaincu. Mieux, elle a retourné en sa faveur le préjugé universaliste égalitariste de la gauche, par une sorte de renversement gramscien, en obtenant qu’elle approuve l’installation en Europe d’un sous-prolétariat massif issu de l’ancien Tiers-monde.

Néanmoins, en raison d’une demande intérieure qui s’affaiblit, pour cause de vieillissement marqué, c’est la stagnation économique qui s’installe. Et pour longtemps, car contrairement à ce que la classe dominante claironne, malgré les nouvelles technologies, les beaux jours ne reviendront pas de si tôt. Elle pense alors résoudre les problèmes posés par la démographie européenne défaillante, en faisant appel aux susdites populations allogènes qui affluent par millions (3,6 millions de places offertes par le gouvernement allemand, d’ici à 2020 !).

Des contradictions insupportables. Cette politique systématique de portes ouvertes à tous les flux, matériels et humains, est cautionnée par tous les partis de gouvernement qui s’y croient obligés, qui n’en imaginent pas d’autres, et qui l’appliquent sans s’inquiéter du fait qu’elle prépare des temps barbares. Car le monde historique, et non pas rêvé, dans lequel nous sommes, reste le monde des forces et de la force, comme tout le démontre autour de nous, et maintenant aussi chez nous.

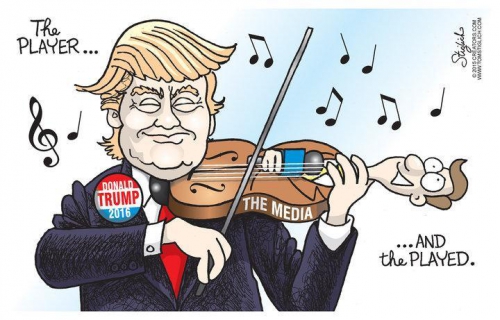

Devant tant de contradictions, seule la puissance des tabous, entretenue par les communicants de service, fait tenir encore le système. Alors que l’interprétation officielle du monde est démentie, tous les jours, par le réel, ils écrasent le champ symbolique et interdisent ainsi la diffusion d’autres façons de penser le monde. On retrouve là une fonction essentielle de l’idéologie qui est de maintenir des formes obsolètes de pensée en dissimulant tout ce qui les dément.

Les limites des populismes.

Malgré toute la défiance qui existe dans les populations européennes envers les partis de gouvernement, pour les raisons que nous venons d’évoquer, les différentes consultations électorales qui ont eu lieu en Europe, ces dernières semaines ou ces derniers mois, ont montré, encore une fois, les limites du populisme.

La faiblesse des partis « attrape-tout ». En France, l’échec du FN à s’emparer d’au moins une des deux ou trois régions qui lui étaient promises, dans un contexte de désaffection du vote qui lui est favorable, est symptomatique de la faiblesse programmatique d’un parti attrape-tout fondé sur le seul réflexe protestataire. Et, qui plus est, demeure un « parti de l’isoloir » (où l’on se cache pour voter pour qui l’on veut), tant il est vrai qu’il manque de cadres compétents (sinon on les connaitrait) et de militants capables d’être en nombre sur le terrain (ce qui serait une faiblesse rédhibitoire en cas de prise miraculeuse du pouvoir), alors même qu’il prétend agir dans la sphère sociale. A l’appui du constat, d’une part, la prestation pathétique de la candidate du Front National dans le Nord-Pas de Calais-Picardie face à son concurrent des Républicains quand celui-ci la questionna sur l’opportunité du retour des frontières pour une région située au cœur de l’Europe, et quand ils débattirent de l’euro. Il n’est pas étonnant que seuls 22% des Français jugent qu’elle ferait une bonne présidente et que 62% d’entre eux qui n’ont jamais voté pour le FN, n’ont pas l’intention de le faire à l’avenir. D’autre part, il y a l’incapacité notoire du parti nationaliste à mobiliser des manifestations de masse. S’il a hérité de l’ancien parti communiste français la fonction tribunitienne qui était la sienne (à savoir, celle de porte parole des classes défavorisées), il est très loin de pouvoir rivaliser, à distance dans le temps, avec lui dans ce domaine. Cela faute de disposer d’un appareil partisan comparable et d’un relais syndical comme la CGT.

L’inconséquence politique des dirigeants. En Espagne, le succès de Podemos s’explique, lui aussi, par le mécontentement d’une grande partie de la population. Mais, il est des plus relatifs, et sans doute éphémère, tant le mouvement est incapable de trouver des alliés, et de préconiser des solutions crédibles (autrement dit non démagogiques et soutenables par l’économie espagnole) pour résoudre la crise sociale. En effet, il est d’autant plus incapable d’y parvenir que, comme l’ultra gauche en France, il est internationaliste. Et qu’à ce titre, il ne saurait admettre que c’est la mondialisation qui a ruiné la plupart des industries espagnoles, et que le salariat espagnol est victime, comme tous les autres en Europe, de la concurrence mondiale.

Et que penser de la motivation de ces populistes régionalistes qui rêvent d’une souveraineté, nécessairement fictive compte tenu des potentiels régionaux concernés, à la seule fin, non exprimée bien sûr, de pouvoir mieux s’intégrer au marché mondial en faisant de leur terre respective un paradis fiscal ? A l’instar des nationalistes affairistes catalans qui entendent transformer leur province en une sorte de Grande Andorre (de culture catalane par ailleurs). Minoritaires en voix (47,8% des bulletins), lors des dernières élections régionales, mais majoritaires en sièges au parlement de Barcelone, grâce au mode de scrutin régional espagnol, ils ont quand même du mal à convaincre que l’Espagne est leur pire ennemi.

L’horizon des populismes est, certes, provisoirement large et dégagé, mais il n’est pas celui du pouvoir et encore moins celui de la maîtrise des réalités.

L’absence de projet politique en adéquation avec le réel. Rassembler des mécontents de tous les bords (et ils sont de plus en plus nombreux) est une chose. Proposer un projet de gouvernement crédible parce qu’en adéquation avec le réel et parce que susceptible de se donner les moyens de peser dans la balance du pouvoir mondial, est autre chose. Or, c’est là le seul critère qui vaille. Tout le reste n’est que verbiage, phantasmes, ou illusion. Car les vraies questions sont : quel Etat en Europe est en mesure de mettre en échec les stratégies de domination des Etats-Unis ou de la Chine ? Quel Etat est en mesure de se mettre, individuellement, à l'abri des fluctuations financières ? De quel pouvoir dispose-t-il pour négocier avec les géants de la finance ou avec les nouvelles économies ? Bon courage aux Anglais, si le Brexit est voté ! A quoi bon reprendre sa souveraineté monétaire si c’est pour disposer d’une monnaie dépréciée et être obligé d’acheter des devises étrangères (dollar ou yuan) pour régler ses paiements internationaux, et un jour, parce que cela arrivera, pour rembourser ses dettes ? Comment s’opposer, seul, et de façon durable, aux mouvements migratoires ou aux forces terroristes ?

Le seul enjeu politique qui s’avère pertinent : la prise du pouvoir à Bruxelles.

Le problème actuel des populismes, aussi légitimes qu’ils soient dans leur aspiration à porter les revendications des populations maltraitées par les politiques mises en place par des gouvernements, tous motivés par l’idéologie libérale et cosmopolite, est qu’ils n’ont rien d’autre à opposer à celle-ci qu’une utopie nostalgique et régressive. En effet, tandis que l’on peut parler d’une idéologie des groupes dominants parce que le libéralisme mondial satisfait leurs intérêts, et que cela les empêche, à la fois, d’en comprendre les effets préjudiciables et d’estimer objectivement l’état réel de la société, l’utopie des populistes consiste à croire que l’on peut revenir en arrière, voire retrouver la gloire passée, ou encore maintenir ce que de longues luttes sociales ont permis d’acquérir, en occultant des pans entiers de la réalité du monde et des changements irréversibles qui se sont opérés. Car, en effet, si le marché mondial donne l’impression de pouvoir se fracturer, la redistribution de la puissance est bel et bien effective, et avec elle, celle de la richesse et des ambitions. Dans ce nouveau contexte, les Etats nationaux européens ne sont plus que des petites puissances inaptes à retenir un mouvement du monde qui leur est devenu défavorable

La mutation radicale du champ de l’action politique. Le niveau pertinent de l’action politique pour les Européens conscients des désastres qui s’annoncent et du dépassement des solutions nationales, dans un monde globalisé, est, d’évidence, celui du continent.

La mutation radicale du champ de l’action politique. Le niveau pertinent de l’action politique pour les Européens conscients des désastres qui s’annoncent et du dépassement des solutions nationales, dans un monde globalisé, est, d’évidence, celui du continent.

Après la crise bancaire de 2008 et la crise de la zone euro non résolue, celle des réfugiés le démontre à son tour. La rationalité politique de la pensée européiste consiste ici à accepter le nouveau monde tel qu’il est, et à produire une nouvelle compréhension de ce monde (car rien ne sert de nier le changement, et de regretter le passé aussi brillant qu’il ait été). Mais, en même temps, l’éthique politique de ce même européisme est une nouvelle volonté du monde en devenir, une volonté des Européens de sauvegarder leurs identités et de compter encore longtemps dans l’histoire, grâce à un rétablissement en leur faveur des rapports de force qui conditionnent tout, qui sont l’essence de la politique mondiale

A ce stade de la réflexion, deux chemins différents, mais qui ne sont pas exclusifs sous certaines conditions, s’offrent aux générations qui viennent pour conduire la lutte politique dont l’objectif est la prise du pouvoir en Europe (à Bruxelles en l’occurrence, d’un point de vue institutionnel), sachant que toute victoire qui demeurerait nationale ou provinciale serait à court terme annihilée. Le premier consiste à persister, malgré tout, dans la voie nationale avec des perspectives de réussite aléatoires selon les pays, puis, dans le meilleur des cas, si les divergences ne sont pas trop grandes et si les contentieux ne sont pas trop nombreux, à envisager des alliances entre les nouveaux pouvoirs contestataires de l’ordre imposé.

Le second, celui qui permettait de sortir des chemins battus, réside dans l’invention d’un style et d’un organe politiques, tous les deux transnationaux, dont l’objectif est l’investissement coordonné du Parlement européen par les mouvements citoyens qui ont commencé à éclore. Et dont on peut concevoir qu’ils ne vont pas cesser de se multiplier au fur et à mesure que le contexte de crises va se confirmer et se durcir. La question qui se pose, et que l’organisme transnational a à résoudre, est celle de leur convergence et de leur fédération dans l’objectif précis de conquérir par les urnes le Parlement européen, afin de pouvoir ainsi changer de l’intérieur l’Union européenne, et par conséquent toutes les politiques non conformes aux intérêts des Européens conduites jusqu’à maintenant. Parce que le Parlement a les pouvoirs de le faire, dès lors qu’existerait en son sein un bloc nettement majoritaire de députés solidaires dans leur vision d’une Europe émancipée de ses vieux tabous idéologiques et consciente de la précarité de son avenir.

Le second, celui qui permettait de sortir des chemins battus, réside dans l’invention d’un style et d’un organe politiques, tous les deux transnationaux, dont l’objectif est l’investissement coordonné du Parlement européen par les mouvements citoyens qui ont commencé à éclore. Et dont on peut concevoir qu’ils ne vont pas cesser de se multiplier au fur et à mesure que le contexte de crises va se confirmer et se durcir. La question qui se pose, et que l’organisme transnational a à résoudre, est celle de leur convergence et de leur fédération dans l’objectif précis de conquérir par les urnes le Parlement européen, afin de pouvoir ainsi changer de l’intérieur l’Union européenne, et par conséquent toutes les politiques non conformes aux intérêts des Européens conduites jusqu’à maintenant. Parce que le Parlement a les pouvoirs de le faire, dès lors qu’existerait en son sein un bloc nettement majoritaire de députés solidaires dans leur vision d’une Europe émancipée de ses vieux tabous idéologiques et consciente de la précarité de son avenir.

Bien évidemment, s’il s’avérait, qu’entre-temps, des pouvoirs nationaux prenaient conscience de l’impérieuse transformation du champ politique et, de ce fait, découvraient la convergence de leurs intérêts propres avec la démarche précédente, leur appui serait des plus décisifs. Il en découlerait la possibilité que se forme un premier noyau étatique dans la perspective d’une unification européenne en plusieurs temps.

Plateforme organisationnelle et doctrinale. Comme l’Histoire l’enseigne, c’est toujours dans l’épreuve que se fondent les grandes constructions. L’épreuve commune permet d’abord la prise de conscience de la précarité de la situation, puis la réflexion sur l’état des lieux et les solutions à trouver, et enfin, sur l’action à entreprendre. Peut-on voir, dès lors, dans les protestations contre « l’islamisation de l’Europe », écume d’un envahissement sournois, ou contre la négociation du traité transatlantique, aussi différemment intentionnés que soient les divers protagonistes, des indices, attendant que d’autres apparaissent, d’une réelle prise de conscience et d’une révolte européenne potentielle? C’est une possibilité, car l’identification d’ennemis ou de défis communs, supposés ou réels peu importe, est un préalable à toute construction politique.

Ce qu’il y a de sûr, aujourd’hui, c’est qu’on ne résoudra pas les crises apparues en se terrant dans les vieilles institutions, mais en élargissant l’horizon de la reconquête idéologique, culturelle et économique à toute l’Europe, et en retrouvant, par avancées simultanées et coordonnées dans toutes les provinces du continent, la voie de la maîtrise. Les premiers mouvements à l’instant évoqués, et tous ceux qui adviendront, doivent servir de « planches d’appel » à un saut vers l’action européenne dans toutes les directions possibles. Car, bien entendu, tout est lié. Et il faut offrir aux groupes résistants dispersés dans l’espace européen une image rationalisée de l’histoire qui se joue sous leurs yeux et qui sera leur lien. En effet, la dispersion politique est l’obstacle insurmontable des populismes, alors que la perspective du rassemblement des peuples européens, qui ont tout inventé, est grosse d’une dynamique irrésistible. Nous avons besoin pour cela d’un européisme intellectuellement offensif qui soit, à la fois, explicatif et critique, propositionnel et programmatique. Mais, comme on ne pense que pour agir, et que la théorie et la praxis vont ensemble, ce nouvel élan mental doit s’accompagner d’un travail d’organisation à l’échelle continentale, préalable aux initiatives à venir.

Au seuil d’une régression civilisationnelle irréversible et d’une dilution ethnocidaire dans le magma universel, un leitmotiv s’impose aux Européens lucides et décidés à ne pas subir : inventer un nouveau style politique continental pour changer les formes politiques afin de sauver le fonds (le substrat humain et civilisationnel de l’Europe).

Gérard Dussouy

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

L’Afrique du Sud évoque principalement pour le public français les Zoulous, l’or, le diamant, Nelson Mandela et les lois de ségrégation raciale qui portaient le nom lugubre d’apartheid, mises en place au milieu du XXe siècle. Une étude géopolitique de l’Afrique du Sud, vingt ans après les premières élections démocratiques, s’impose. La puissance économique de l’Afrique du Sud (elle assure 1/5e du PIB du continent) et ses réserves en minerais et en métaux précieux lui confèrent une place particulière sur la scène internationale. Ce pays a également une ambition militaire et politique et participe à de nombreuses opérations de maintien de la paix en Afrique. L’Afrique du Sud est une démocratie, la presse bénéficie d’une réelle liberté, les syndicats ont des droits reconnus, les scrutins électoraux qui se tiennent aux échéances prévues ne sont pas entachés de fraude. Mais cette réussite pourrait n’être qu’une parenthèse, car elle reste très fragile et la pérennité des institutions démocratiques n’est guère assurée. Cet ouvrage présente l’Afrique du Sud du XXIe siècle, les atouts et les faiblesses d’une nation en construction.

L’Afrique du Sud évoque principalement pour le public français les Zoulous, l’or, le diamant, Nelson Mandela et les lois de ségrégation raciale qui portaient le nom lugubre d’apartheid, mises en place au milieu du XXe siècle. Une étude géopolitique de l’Afrique du Sud, vingt ans après les premières élections démocratiques, s’impose. La puissance économique de l’Afrique du Sud (elle assure 1/5e du PIB du continent) et ses réserves en minerais et en métaux précieux lui confèrent une place particulière sur la scène internationale. Ce pays a également une ambition militaire et politique et participe à de nombreuses opérations de maintien de la paix en Afrique. L’Afrique du Sud est une démocratie, la presse bénéficie d’une réelle liberté, les syndicats ont des droits reconnus, les scrutins électoraux qui se tiennent aux échéances prévues ne sont pas entachés de fraude. Mais cette réussite pourrait n’être qu’une parenthèse, car elle reste très fragile et la pérennité des institutions démocratiques n’est guère assurée. Cet ouvrage présente l’Afrique du Sud du XXIe siècle, les atouts et les faiblesses d’une nation en construction.

Il faut croire que nous arrivons à un carrefour dans notre Histoire suite à un emballement frénétique typique de notre société post-moderne. 2015 marque en effet le début de ce qui semble être une nouvelle ère avec le retour en puissance du terrorisme islamique sur le sol européen et ce pour le plus grand malheur de l’irénisme ambiant et de l’hédonisme-matérialiste de l’homo occidentalis. Hélas ! La réponse à la menace terroriste est tout aussi funeste que la menace elle-même : outre le déni de réalité, l’état d’urgence et la société sécuritaire. Nous sommes littéralement dans la gueule du loup.

Il faut croire que nous arrivons à un carrefour dans notre Histoire suite à un emballement frénétique typique de notre société post-moderne. 2015 marque en effet le début de ce qui semble être une nouvelle ère avec le retour en puissance du terrorisme islamique sur le sol européen et ce pour le plus grand malheur de l’irénisme ambiant et de l’hédonisme-matérialiste de l’homo occidentalis. Hélas ! La réponse à la menace terroriste est tout aussi funeste que la menace elle-même : outre le déni de réalité, l’état d’urgence et la société sécuritaire. Nous sommes littéralement dans la gueule du loup.

De tweede opvatting gaat terug op de Amerikaanse Revolutie. De Founding Fathers gaven aan het begrip democratie een pragmatische en realistische invulling. Zij koesterden geen illusies over de menselijke natuur. De maatschappij kan weliswaar verbeterd worden, maar de mens blijft fundamenteel dezelfde. Macht maakt corrupt en moet aan banden worden gelegd. Vandaar het complexe systeem van checks and balances, de scheiding van de machten en een indrukwekkende grondwet die de vrijheden van de burgers waarborgt. Een paradijs ligt niet in het verschiet en een nieuwe mens al evenmin.

De tweede opvatting gaat terug op de Amerikaanse Revolutie. De Founding Fathers gaven aan het begrip democratie een pragmatische en realistische invulling. Zij koesterden geen illusies over de menselijke natuur. De maatschappij kan weliswaar verbeterd worden, maar de mens blijft fundamenteel dezelfde. Macht maakt corrupt en moet aan banden worden gelegd. Vandaar het complexe systeem van checks and balances, de scheiding van de machten en een indrukwekkende grondwet die de vrijheden van de burgers waarborgt. Een paradijs ligt niet in het verschiet en een nieuwe mens al evenmin.

It is a common myth on the Right, that while the rightists are divided, the leftists have clearly defined goals and are struggling together to achieve them. While I do agree that the Left has more common goals (privileges for sexual, religious, and ethnic minorities, the destruction of ethnically homogeneous countries and nations, etc.) I do not agree that the Left is united in realizing these aims. When it comes to issues of the hierarchy of these goals, the means of achieving them, or leadership, they are just as divided as the Right, or even more.

It is a common myth on the Right, that while the rightists are divided, the leftists have clearly defined goals and are struggling together to achieve them. While I do agree that the Left has more common goals (privileges for sexual, religious, and ethnic minorities, the destruction of ethnically homogeneous countries and nations, etc.) I do not agree that the Left is united in realizing these aims. When it comes to issues of the hierarchy of these goals, the means of achieving them, or leadership, they are just as divided as the Right, or even more.

Mevrouw, mijnheer,

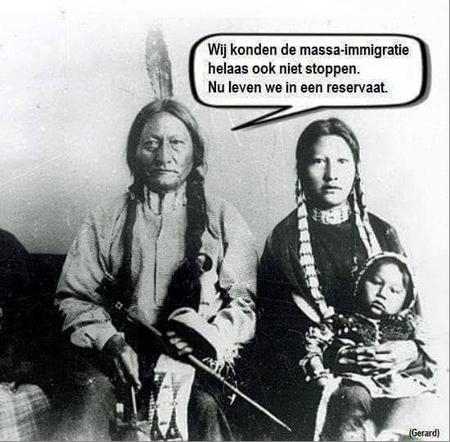

Mevrouw, mijnheer, Vanaf de tweede helft van de negentiende eeuw, toen de migratie tsunami steeds verder naar het westen trok, was het lot van de Indianen bezegeld. Ze werden systematisch van hun gronden verjaagd, bizons die de basisvoeding van bepaalde stammen waren, werden massaal uitgeroeid en vaak de Indianen zelf ook. Uiteindelijk kwamen ze in reservaten terecht die hen door de bezetters van hun land werden toebedeeld. Op enkele uitzonderingen na leiden ze er een soort vegetatief en vrij doelloos bestaan. Hun oorspronkelijke cultuur wordt er bovendien gereduceerd tot een soort folklore waarmee toeristen kunnen worden geëntertaind en soms zelfs tot min of meer spectaculaire circusattracties (dat was al zo in de tijd van Buffalo Bill). De Indianen werden overigens nooit opgenomen in de Amerikaanse melting pot maatschappij want in die smeltkroes van immigranten van over gans de wereld horen zij als enige echte autochtonen niet thuis.

Vanaf de tweede helft van de negentiende eeuw, toen de migratie tsunami steeds verder naar het westen trok, was het lot van de Indianen bezegeld. Ze werden systematisch van hun gronden verjaagd, bizons die de basisvoeding van bepaalde stammen waren, werden massaal uitgeroeid en vaak de Indianen zelf ook. Uiteindelijk kwamen ze in reservaten terecht die hen door de bezetters van hun land werden toebedeeld. Op enkele uitzonderingen na leiden ze er een soort vegetatief en vrij doelloos bestaan. Hun oorspronkelijke cultuur wordt er bovendien gereduceerd tot een soort folklore waarmee toeristen kunnen worden geëntertaind en soms zelfs tot min of meer spectaculaire circusattracties (dat was al zo in de tijd van Buffalo Bill). De Indianen werden overigens nooit opgenomen in de Amerikaanse melting pot maatschappij want in die smeltkroes van immigranten van over gans de wereld horen zij als enige echte autochtonen niet thuis.

Overreaching man is for Weil the main subject of Greek thought. Retribution, Nemesis. These are buried in the soul of Greek epic poetry. So starts the discussion on the nature of man. Kharma. We think

Overreaching man is for Weil the main subject of Greek thought. Retribution, Nemesis. These are buried in the soul of Greek epic poetry. So starts the discussion on the nature of man. Kharma. We think

Marianne :

Marianne :  La deuxième étape renvoie à ce j’ai appelé « l’héritage impossible » de mai 68. Je parle bien de l’héritage impossible et non de l’événement historique lui-même. C’est ma différence avec Eric Zemmour et d’autres critiques qui ont un aspect « revanchard » : je ne règle pas des comptes avec l’événement historique et les soixante-huitards ne sont pas responsables de tous les maux que nous connaissons aujourd’hui. En France, l’événement mai 68 a été un événement à multiples facettes où ont coexisté la « Commune étudiante », une grève générale qui rappelait les grandes heures du mouvement ouvrier et une prise de parole multiforme qui a été largement vécue comme une véritable libération dans le climat de l’époque. L’événement historique Mai 68 n’appartient à personne, c’est un événement important de l’Histoire de France, et plus globalement des sociétés développées de l’après-guerre qui sont entrées dans une nouvelle phase de leur histoire et ont vu surgir un nouvel acteur : la jeunesse étudiante. Ce que le regretté Paul Yonnet a appelé le « peuple adolescent ». En ce se sens, à l’époque, Edgar Morin est l’un de ceux qui a le mieux perçu la caractère inédit de l’événement en caractérisant la « Commune étudiante » comme un « 1789 socio-juvénile ».

La deuxième étape renvoie à ce j’ai appelé « l’héritage impossible » de mai 68. Je parle bien de l’héritage impossible et non de l’événement historique lui-même. C’est ma différence avec Eric Zemmour et d’autres critiques qui ont un aspect « revanchard » : je ne règle pas des comptes avec l’événement historique et les soixante-huitards ne sont pas responsables de tous les maux que nous connaissons aujourd’hui. En France, l’événement mai 68 a été un événement à multiples facettes où ont coexisté la « Commune étudiante », une grève générale qui rappelait les grandes heures du mouvement ouvrier et une prise de parole multiforme qui a été largement vécue comme une véritable libération dans le climat de l’époque. L’événement historique Mai 68 n’appartient à personne, c’est un événement important de l’Histoire de France, et plus globalement des sociétés développées de l’après-guerre qui sont entrées dans une nouvelle phase de leur histoire et ont vu surgir un nouvel acteur : la jeunesse étudiante. Ce que le regretté Paul Yonnet a appelé le « peuple adolescent ». En ce se sens, à l’époque, Edgar Morin est l’un de ceux qui a le mieux perçu la caractère inédit de l’événement en caractérisant la « Commune étudiante » comme un « 1789 socio-juvénile ». J-P LG : L’éducation était antérieurement liée à une conception pour qui les contraintes, la limite, le tragique étaient considérés comme inhérents à la condition humaine, tout autant que les plaisirs de la vie, la sociabilité et la solidarité. Devenir adulte c’était accepter cette situation au terme de tout un parcours qui distinguait clairement et respectait les différentes étapes de la vie marquées par des rituels qui inséraient progressivement l’enfant dans la collectivité. C’est précisément cette conception qui s’est trouvée mise à mal au profit nom d’une conception nouvelle de l’enfance et de l’adolescence qui a érigé ces étapes spécifiques de la vie en des sortes de modèles culturels de référence. Valoriser les enfants et les adolescents en les considérant d’emblée comme des adultes et des citoyens responsables, c’est non seulement ne pas respecter la singularité de ces étapes de la vie, mais c’est engendrer à terme des « adultes mal finis » et des citoyens irresponsables. Aujourd’hui, il y a un écrasement des différentes étapes au profit d’un enfant qui doit être autonome et quasiment citoyen dès son plus jeune âge. Et qui doit parler comme un adulte à propos de tout et de n’importe quoi. On en voit des traces à la télévision tous les jours, par exemple quand un enfant vante une émission de télévision en appelant les adultes à la regarder ou pire encore dans une publicité insupportable pour Renault où un enfant-singe-savant en costume co-présente les bienfaits d’une voiture électrique avec son homologue adulte… Cette instrumentalisation et cet étalage de l’enfant-singe sont obscènes et dégradants. Les adultes en sont responsables et les enfants victimes. Paul Yonnet a été le premier à mettre en lumière non seulement l’émergence de « l’enfant du désir » mais celui du « peuple adolescent ». Dans la société, la période de l’adolescence avec son intensité et ses comportements transgressifs a été mise en exergue comme le centre de la vie. Cette période transitoire de la vie semble durer de plus en plus longtemps, le chômage des jeunes n’arrange pas les choses et les « adultes mal finis » ont du mal à la quitter.

J-P LG : L’éducation était antérieurement liée à une conception pour qui les contraintes, la limite, le tragique étaient considérés comme inhérents à la condition humaine, tout autant que les plaisirs de la vie, la sociabilité et la solidarité. Devenir adulte c’était accepter cette situation au terme de tout un parcours qui distinguait clairement et respectait les différentes étapes de la vie marquées par des rituels qui inséraient progressivement l’enfant dans la collectivité. C’est précisément cette conception qui s’est trouvée mise à mal au profit nom d’une conception nouvelle de l’enfance et de l’adolescence qui a érigé ces étapes spécifiques de la vie en des sortes de modèles culturels de référence. Valoriser les enfants et les adolescents en les considérant d’emblée comme des adultes et des citoyens responsables, c’est non seulement ne pas respecter la singularité de ces étapes de la vie, mais c’est engendrer à terme des « adultes mal finis » et des citoyens irresponsables. Aujourd’hui, il y a un écrasement des différentes étapes au profit d’un enfant qui doit être autonome et quasiment citoyen dès son plus jeune âge. Et qui doit parler comme un adulte à propos de tout et de n’importe quoi. On en voit des traces à la télévision tous les jours, par exemple quand un enfant vante une émission de télévision en appelant les adultes à la regarder ou pire encore dans une publicité insupportable pour Renault où un enfant-singe-savant en costume co-présente les bienfaits d’une voiture électrique avec son homologue adulte… Cette instrumentalisation et cet étalage de l’enfant-singe sont obscènes et dégradants. Les adultes en sont responsables et les enfants victimes. Paul Yonnet a été le premier à mettre en lumière non seulement l’émergence de « l’enfant du désir » mais celui du « peuple adolescent ». Dans la société, la période de l’adolescence avec son intensité et ses comportements transgressifs a été mise en exergue comme le centre de la vie. Cette période transitoire de la vie semble durer de plus en plus longtemps, le chômage des jeunes n’arrange pas les choses et les « adultes mal finis » ont du mal à la quitter. J-P LG : Ce n’est pas parce que cette période historique est en train de finir que ce qui va suivre est nécessairement réjouissant. Le monde fictif et angélique qui s’est construit pendant des années – auquel du reste, à sa manière, l’Union européenne a participé en pratiquant la fuite en avant – craque de toutes parts, il se décompose et cela renforce le désarroi et le chaos. La confusion, les fondamentalismes, le communautarisme, l’extrême droite gagnent du terrain… Le tout peut déboucher sur des formes de conflits ethniques et des formes larvées de guerre civile y compris au sein de l’Union européenne. On en aura vraiment fini avec cette situation que si une dynamique nouvelle émerge au sein des pays démocratiques, ce qui implique un travail de reconstruction, auquel les intellectuels ont leur part. Il importe tout particulièrement de mener un travail de reculturation au sein d’un pays et d’une Europe qui ne semblent plus savoir d’où ils viennent, qui il sont et où il vont. Tout n’est pas perdu : on voit bien, aujourd’hui, qu’existe une demande encore confuse, mais réelle de retour du collectif, d’institutions et d’un Etat cohérent qui puissent affronter les nouveaux désordres du monde. Ce sont des signes positifs.

J-P LG : Ce n’est pas parce que cette période historique est en train de finir que ce qui va suivre est nécessairement réjouissant. Le monde fictif et angélique qui s’est construit pendant des années – auquel du reste, à sa manière, l’Union européenne a participé en pratiquant la fuite en avant – craque de toutes parts, il se décompose et cela renforce le désarroi et le chaos. La confusion, les fondamentalismes, le communautarisme, l’extrême droite gagnent du terrain… Le tout peut déboucher sur des formes de conflits ethniques et des formes larvées de guerre civile y compris au sein de l’Union européenne. On en aura vraiment fini avec cette situation que si une dynamique nouvelle émerge au sein des pays démocratiques, ce qui implique un travail de reconstruction, auquel les intellectuels ont leur part. Il importe tout particulièrement de mener un travail de reculturation au sein d’un pays et d’une Europe qui ne semblent plus savoir d’où ils viennent, qui il sont et où il vont. Tout n’est pas perdu : on voit bien, aujourd’hui, qu’existe une demande encore confuse, mais réelle de retour du collectif, d’institutions et d’un Etat cohérent qui puissent affronter les nouveaux désordres du monde. Ce sont des signes positifs.