dimanche, 03 février 2019

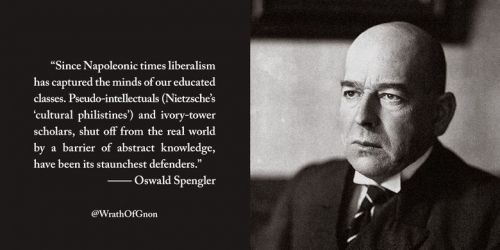

Dezsö Csejtei auf der Oswald-Spengler-Konferenz 2018

00:44 Publié dans Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, philosophie de l'histoire, oswald spengler, allemagne, révolution conservatrice |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 02 février 2019

Prof. Dr. Max Otte auf der Oswald-Spengler-Konferenz 2018

00:40 Publié dans Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, philosophie de l'histoire, oswald spengler, allemagne, révolution conservatrice |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 01 février 2019

Jürgen Egyptien: Stefan George – Dichter und Prophet

01:37 Publié dans Littérature, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : poésie, stefan george, littérature, littérature allemande, lettres, lettres allemandes, révolution conservatrice, allemagne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Gregory Swer auf der Oswald-Spengler-Konferenz 2018

Gregory Swer auf der Oswald-Spengler-Konferenz 2018

00:35 Publié dans Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, philosophie de l'histoire, oswald spengler, révolution conservatrice, allemagne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

A propos du traité d'Aix la chapelle et de la notion de souveraineté

A propos du traité d'Aix la chapelle et de la notion de souveraineté

par Pierre Eisner

Ex: http://thomasferrier.hautetfort.com

La signature du traité dit d’Aix-la-Chapelle entre la France et l’Allemagne a suscité beaucoup de réactions. Sans doute a-t-on attaché trop d’importance à ce qui n’était qu’une opération de communication. Elle a été voulue par Emmanuel Macron pour l’aider à construire une façade de partisan de l’Europe, et concédée par Angela Merkel qui n’a plus de poids politique. Même s’il a fallu flatter le voisin allemand pour y parvenir. Mais tout texte, fût-il mal conçu et peu contraignant, a malgré tout une signification.

Le Rassemblement national (RN), comme une certaine partie de la droite, y a vu une perte de souveraineté, certains parlant de trahison. C’est sur cette perte supposée qu’il nous faut réfléchir. De quelle souveraineté s’agit-il quand on parle de celle de la France ? Est-ce celle du pouvoir de son dirigeant ou est-ce celle du pouvoir de son peuple ?

Le président Emmanuel Macron n’a pas perdu la moindre parcelle de son pouvoir par le fait du traité. Prenons ainsi l’exemple de la politique étrangère et de la défense. La France et l’Allemagne se sont engagées à coordonner leurs actions dans ces domaines, favorisant les échanges de personnel diplomatique et instituant notamment un Conseil franco-allemand de défense et de sécurité. Si, pour une raison quelconque, les dirigeants français et allemands sont amenés à prendre des décisions contradictoires, comme cela a été souvent la cas dans un passé récent, rien ne pourra les en empêcher. Alors ils se garderont bien de faire jouer les instances communes qu’ils ont instituées. En revanche si l’un ou l’autre, à propos d’une question un peu épineuse et faisant débat, est en phase avec son homologue ou parvient à le convaincre de rejoindre sa position, il pourra expliquer dans son pays qu’il est contraint par l’obligation de trouver une position commune, sollicitant par exemple l’avis d’un Conseil compétent.

En revanche le peuple français, comme le peuple allemand, aura perdu un peu de son pouvoir. On vient d’expliquer le mécanisme qui permet de court-circuiter le peuple lorsque sa position pourrait ne pas être celle attendue par son dirigeant.

C’est exactement ce qui se passe avec l’actuelle Union européenne. Il est inexact de dire que telle ou telle décision est imposée par Bruxelles. Lorsque l’avis des représentants du peuple français n’est pas sollicité, au prétexte de l’obligation de se conformer à telle règle européenne, c’est parce que son dirigeant s’est arrangé auparavant avec ses homologues pour ladite règle soit instaurée. Il y a bien un cas où la règle européenne est légitime. C’est celui de l’Euro et de la règle des 3% relative au déficits publics. En France au moins, le peuple s’est prononcé par référendum. Le paradoxe est que cette règle a été peu contraignante. On a accepté n’importe quoi de la Grèce pour son admission, comme de la France pour s’y conformer. Si la règle n’est pas respectée en 2019, il est peu probable que cela fasse des vagues.

Il y a bien un transfert de pouvoir, aussi bien à l’occasion de ce traité franco-allemand qu’à l’occasion des traités européens. Mais un transfert du pouvoir populaire au bénéfice du pouvoir discrétionnaire d’un dirigeant. C’est une perte sèche de démocratie, indépendamment de ce qu’on peut mettre comme périmètre pour définir le peuple.

Ce n’est pas comme si une Europe politique était installée, sous la forme d’un état unifié. Ou comme si la France et l’Allemagne fusionnaient pour donner naissance à un état commun. On pourrait alors parler de transfert de souveraineté démocratique. Aujourd’hui la souveraineté démocratique n’est pas transférée : elle est dissoute au bénéfice d’une techno-structure et in fine des membres d’un club.

Pour revenir au traité franco-allemand ou à toutes les opérations qui y ressemblent, dans l’absence d’une instance politique installée au niveau adéquat, pour produire les rapprochements, les convergences que l’on peut raisonnablement souhaiter, ce ne sont pas des institutions qu’il faut créer pour tenter de les imposer, mais des convergences qu’il faut réaliser, sous le contrôle des citoyens de tous les états concernés.

Évidemment c’est difficile : il faut des dirigeants éclairés et courageux pour cela. Et cela concerne certains sujets comme l’économie, quand la diplomatie a besoin d’une légitimité politique et quand la lutte contre le terrorisme peut se contenter d’une coopération avec une mise en commun de moyens. A l’inverse, les institutions nouvelles, qui se multiplient à l’infini avec un coût incontrôlé, ne sont que des alibis. Chacun le sait : quand on veut évacuer un problème, on crée une commission.

C’est ainsi qu’il faut apprécier le traité d’Aix-la-Chapelle. Beaucoup de bruit pour rien, surtout pour ne rien faire de sérieux. Juste de la poudre aux yeux, mais qui peut aveugler.

Pierre EISNER (Le Parti des Européens)

00:28 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : politique internationale, europe, affaires européennes, union européenne, traité d'aix-la-chapelle, aix-la-chapelle, emmanuel marcron, angela merkel, france, allemagne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 31 janvier 2019

Prof. Dr. Alexander Demandt auf der Oswald-Spengler-Konferenz 2018

01:38 Publié dans Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : allemagne, alexander demandt, oswald sepngler, révolution conservatrice, philosophie, philosophie de l'histoire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 30 janvier 2019

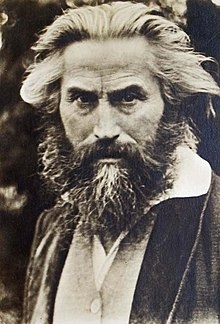

Werner Sombart ce grand oublié de l'histoire

01:25 Publié dans Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : capitalisme, werner sombart, socialisme, socialisme allemand, allemagne, philosophie politique, théorie politique, sciences politiques, politologie, révolution conservatrice |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Prof. Dr. Gerd Morgenthaler auf der Oswald-Spengler-Konferenz 2018

Prof. Dr. Gerd Morgenthaler auf der Oswald-Spengler-Konferenz 2018

00:32 Publié dans Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : oswald spengler, révolution conservatrice, allemagne, philosophie, philosophie de l'histoire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 29 janvier 2019

"Oswald Spengler ou le tourment de l'avenir"

11:57 Publié dans Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, philosophie de l'histoire, oswald spengler, allemagne, révolution conservatrice |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 26 janvier 2019

Presseschau Januar 2019

Presseschau

Januar 2019

AUßENPOLITISCHES

Gefahr einer Eskalation

OSZE warnt vor Nationalismus in Europa

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/osze-warnt-vor-nationalismus-in-europa/

Spaniens ultrarechte Partei Vox zieht ins Regionalparlament von Andalusien ein https://www.gmx.net/magazine/politik/spaniens-ultrarechte-partei-vox-regionalparlament-andalusien-33447198

Vox-Partei in Spanien

Der Aufstieg der Rechtsextremen

https://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/spanien-vox-101.html

Frankreich in Aufruhr

Europas Held ohne Volk

von Jürgen Liminski

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/europas-held-ohne-volk/

„Gelbwesten“

Über 700 Schüler bei Protesten in Frankreich festgenommen https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/ueber-700-schueler-bei-protesten-in-frankreich-festgenommen/

Gelbe Westen – Alain de Benoist im Gespräch

https://sezession.de/59957/gelbe-westen-alain-de-benoist-im-gespraech

Zusagen an Gelbwesten: Günther Oettinger fordert Defizitverfahren gegen Frankreich Weil Emmanuel Macron den Gelbwesten Zusagen in Milliardenhöhe gemacht hat, wird sich Frankreich höher verschulden. Der EU-Haushaltskommissar will das nicht hinnehmen.

https://www.zeit.de/politik/ausland/2018-12/zusagen-gelbwesten-frankreich-guenther-oettinger-defizitverfahren-neuverschuldung

(Einige Tage später...)

Oettinger: Höhere französische Schulden einmalig tolerieren Frankreichs Präsident Emmanuel Macron erhält für seine milliardenschweren Sozialmaßnahmen erneut Rückhalt aus der EU. «Wir haben den französischen Etat vor einigen Wochen geprüft und werden jetzt nicht erneut in Prüfung gehen», sagte EU-Haushaltskommissar Günther Oettinger den Zeitungen der Funke-Mediengruppe. Sollte Frankreich an seiner Reformpolitik festhalten, «werden wir eine Staatsverschuldung, die höher liegt als drei Prozent, als einmalige Ausnahme tolerieren». Macron hatte wegen der «Gelbwesten»-Krise den «sozialen und wirtschaftlichen Notstand ausgerufen».

https://www.stern.de/panorama/oettinger--hoehere-franzoesische-schulden-einmalig-tolerieren-8506872.html

(Zu Macron und dem Migrationspakt)

Sonntagsheld (88) – General-Streik

https://sezession.de/60006/sonntagsheld-88-general-streik

29-Jähriger auf der Flucht

Die Jagd nach dem Täter von Straßburg

https://www.welt.de/politik/ausland/article185382336/Zwei-Tote-in-Strassburg-auf-Weihnachtsmarkt-Die-Jagd-nach-dem-fluechtigen-Taeter.html

Straßburg-Attentäter von Polizei erschossen

https://www.br.de/nachrichten/deutschland-welt/strassburg-attentaeter-von-polizei-erschossen,RC91YGd

Anschlag von Straßburg

Der Terror ist eingeschleppt

von Karlheinz Weißmann

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/der-terro...

Wegen Streits um UN-Migrationspakt

Belgische Regierung in Turbulenzen

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/belgische-regierung-wackelt/

Brüssel: Ausschreitungen bei Demonstration gegen UN-Migrationspakt https://www.zeit.de/politik/ausland/2018-12/bruessel-demonstration-protest-un-migrationspakt

Vor Brexit-Abstimmung

Tausende Briten schließen sich Demo von Rechtsextremen an http://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/london-tausende-protestieren-mit-rechtsextremen-fuer-den-brexit-a-1242784.html

Briten im Endzeitmodus

Prepper rüsten sich für den Brexit

https://www.n-tv.de/panorama/Prepper-ruesten-sich-fuer-den-Brexit-article20737519.html

3500 Soldaten in Wartestellung

Britische Armee wappnet sich für Chaos-Brexit

https://www.n-tv.de/politik/Britische-Armee-wappnet-sich-fuer-Chaos-Brexit-article20779576.html

Bis 2030

EU verschärft CO2-Grenzwerte für Neuwagen

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/eu-verschaerft-co2-grenzwerte-fuer-neuwagen/

Guerilla-Urbanisten aus der Zarenstadt

Junge Aktivisten wollen den Bürgern von St. Petersburg zeigen, wie sie urbanen Raum zurückerobern können. Dadurch möchten sie in der breiten Bevölkerung für politisches und demokratisches Bewusstsein sorgen

https://www.fluter.de/politischer-aktivismus-in-russland

Stellungname des Außenministeriums

Israel setzt Boykott von FPÖ-Ministern fort

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/israel-setzt-fpoe-boykott-fort/

China: Die Welt des Xi Jinping | Doku | ARTE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o4BA_6RROJ8

Amerikanische Lektionen I – Wahlsiege und Machtstrukturen https://sezession.de/59981/amerikanische-lektionen-i-wahlsiege-und-machtstrukturen

Fiasko um Mauerfinanzierung

US-Shutdown tritt in Kraft

https://www.n-tv.de/politik/US-Shutdown-tritt-in-Kraft-article20785729.html

(Nächste Verunglimpfungsakion)

Neue Amphibienart nach Trump benannt – als Kritik an dessen Klimapolitik https://www.watson.ch/international/usa/581868632-neue-amphibienart-nach-trump-benannt-als-kritik-an-dessen-klimapolitik

(Billy Six)

Südamerika

Deutscher Reporter in Venezuela verhaftet

http://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/venezuela-deutscher-reporter-billy-six-in-venezuela-verhaftet-a-1244013.html

Freiheit für Billy Six!

Knastweihnacht in Caracas

von Dieter Stein

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/streiflicht/2018/knastweihnacht-in-caracas/

Exodus aus Venezuela – die nächste Völkerwanderung!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TaeBIppXr2M

Die Krise in Venezuela zeigt, dass Lateinamerika sich nicht länger vor der Geschichte verstecken kann

https://www.nzz.ch/meinung/die-krise-in-venezuela-zeigt-dass-lateinamerika-sich-nicht-laenger-vor-der-geschichte-verstecken-kann-ld.1425093

Europas und Nordamerikas Linke schweigt

Venezuela – Ein reiches Land, vom Sozialismus ruiniert https://www.tichyseinblick.de/kolumnen/aus-aller-welt/venezuela-ein-reiches-land-vom-sozialismus-ruiniert/

Mexikos linker Präsident wird Liebling der Märkte https://www.heise.de/tp/features/Mexikos-linker-Praesident-wird-Liebling-der-Maerkte-4255855.html

Kuba, real und nicht geschönt

Polizeistaat Kuba: Verhör in Havanna

https://www.tichyseinblick.de/kolumnen/aus-aller-welt/polizeistaat-kuba-verhoer-in-havanna/

Proteste in Haiti gegen Korruption

https://www.bote.ch/nachrichten/international/proteste-in-haiti-gegen-korruption;art46446,1132483

AfD-Politiker Petr Bystron

„Ich will auf die Situation der weißen Farmer in Südafrika aufmerksam machen“ https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/interview/2018/ich-will-auf-die-situation-der-weissen-farmer-in-suedafrika-aufmerksam-machen/

Afrika hat genug von seinen Helfern

https://www.achgut.com/artikel/afrika_hat_genug_von_seinen_helfern

Hat Madagaskar noch eine Chance?

Von Volker Seitz

https://www.achgut.com/artikel/hat_madagaskar_noch_eine_chance

Südsudan will neue Hauptstadt : Ein kapitaler Plan https://www.faz.net/aktuell/gesellschaft/menschen/suedsudan-will-neue-hauptstadt-ein-kapitaler-plan-15927995.html

Terror an den Pyramiden

Tote bei Anschlag auf Touristenbus in Ägypten

https://www.t-online.de/nachrichten/ausland/id_85008988/aegypten-zwei-tote-bei-anschlag-auf-touristenbus-nahe-pyramiden.html

INNENPOLITISCHES / GESELLSCHAFT / VERGANGENHEITSPOLITIK

(Psychologie der herrschenden Generation)

„Die Wiedergutmacher“

Psychosen im gefühlsgeleiteten Hippiestaat

von Thorsten Hinz

https://jungefreiheit.de/kultur/literatur/2018/psychosen-im-gefuehlsgeleiteten-hippiestaat/

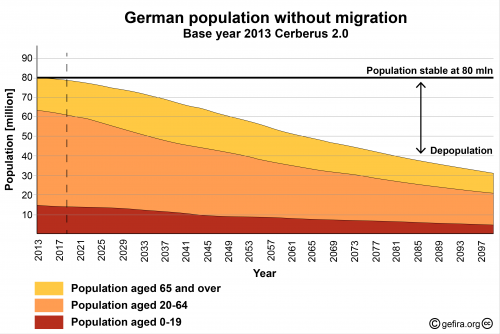

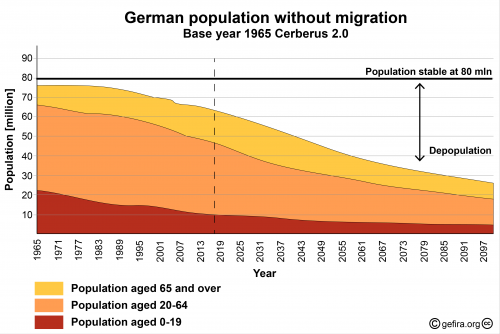

„Wir schaffen das“ oder deutlicher: „Deutschland schafft sich ab“

https://www.goldseiten.de/artikel/398592--Wir-schaffen-da...

Wirtschaftsentwicklung 2019 – Die deutsche Lust am Niedergang

https://www.cicero.de/wirtschaft/wirtschaftsentwicklung-2...

Auf dem Gipfel deutscher Schizophrenie

von Markus Vahlefeld

https://www.achgut.com/artikel/auf_dem_gipfel_deutscher_schizophrenie

Union ganz vorne

Das sind die größten Partei-Spenden 2018

https://www.abendzeitung-muenchen.de/inhalt.union-ganz-vorne-das-sind-die-groessten-partei-spenden-2018.d4c0239d-fad5-4813-a4cd-ccf240f8f8bd.html

Zur Wahl von Kramp-Karrenbauer zur CDU-Vorsitzenden Weitermerkeln

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/weitermerkeln/

Susi Neumann

„Von der SPD kann man nix mehr erwarten“- Ex-Putzfrau verkündet Austritt aus Partei https://www.focus.de/politik/deutschland/susi-neumann-von-der-spd-kann-man-nix-mehr-erwarten-ex-putzfrau-verkuendet-austritt-aus-partei_id_10022261.html

Abrechnung mit „Schlipsträgern“

Ex-Putzfrau Susanne Neumann tritt aus SPD aus

http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/spd-ex-putzfrau-susanne-neumann-tritt-aus-der-partei-aus-a-1242056.html

SPD startet neues Ausschlussverfahren gegen Thilo Sarrazin https://www.handelsblatt.com/politik/deutschland/spd-vorstand-spd-startet-neues-ausschlussverfahren-gegen-thilo-sarrazin/23769112.html?ticket=ST-86803-mnjw5ygFrGsMxqFhyyTi-ap4

Internationaler Tag

Bundesregierung: Geistig Behinderte sollen wählen dürfen https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/bundesregierung-geistig-behinderte-sollen-waehlen-duerfen/

Nach Terrroranschlag auf Berliner Weihnachtsmarkt: LKW-Besitzer zürnt über Berlin https://web.de/magazine/panorama/terrroranschlag-berliner-weihnachtsmarkt-lkw-besitzer-zuernt-berlin-33470462

Terroranschlag auf Berliner Weihnachtsmarkt

Zwei Jahre danach – und das Staatsversagen geht weiter von Michael Paulwitz

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/zwei-jahre-danach-und-das-staatsversagen-geht-weiter/

„Egal woran Sie glauben“

Integrationsbeauftragte verschickt weihnachtslose Weihnachtsgrüße https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/integrationsbeauftragte-verschickt-weihnachtslose-weihnachtsgruesse/

Flüchtlingskrise 2015

Bundesverfassungsgericht schmettert AfD-Klagen zur Asylpolitik ab

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/bundesv...

Streit um das Amt der Bundestagsvizepräsidentin

Schäbiges Verhalten der Altparteien

von Jörg Kürschner

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/2018/schaebiges-verhalten-der-altparteien/

Schleswig-Holstein

Kieler AfD-Landtagsfraktion schließt Sayn-Wittgenstein aus https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/kieler-afd-landtagsfraktion-schliesst-sayn-wittgenstein-aus/

Eklat in Stuttgarter Landtag

Polizei begleitetet AfD-Politiker aus Plenum

https://www.n-tv.de/politik/Polizei-begleitetet-AfD-Politiker-aus-Plenum-article20770134.html

Landtagspräsidentin Muhterem Aras

„Aggression der AfD-Fraktion nimmt zu“

https://www.stuttgarter-zeitung.de/inhalt.landtagspraesidentin-muhterem-aras-aggression-der-afd-fraktion-nimmt-zu.97d09ba9-04a3-46aa-b071-a4c64265d920.html

Stuttgart

Landtagspräsidentin sieht „höchste Eskalationsstufe“ mit der AfD https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article185574044/Stuttgart-Landtagspraesidentin-sieht-hoechste-Eskalationsstufe-mit-der-AfD.html

70 Jahre FDP

Die „nationalen“ und „rechten“ Wurzeln vergessen von Karlheinz Weißmann

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/die-nationalen-und-rechten-wurzeln-vergessen/

Nicht der letzte Akt

Deutschlands halber Ausstieg aus der Kohle

Mit einem Staatsakt hat sich Deutschland am Freitag von der Steinkohle verabschiedet. Schauplatz war das Bergwerk Prosper-Haniel im Ruhrgebiet, das letzte noch aktive. Allerdings ist der Abschied von der Kohle nur ein halber: Künftig wird Steinkohle importiert und weiter in Kraftwerken verbrannt, Braunkohle wird weiter gefördert, und wie die Zeit danach aussehen soll, ist auch noch nicht klar.

https://orf.at/stories/3105159/

Neue Feiertage für die Hauptstadt

Berlin: Tag der deutschen Kapitulation wird Feiertag https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/berlin-tag-der-deutschen-kapitulation-wird-feiertag/

17.000 ermordete Juden: Kein Prozess gegen KZ-Wachmann

https://www.faz.net/aktuell/rhein-main/prozess-gegen-kz-w...

LINKE / KAMPF GEGEN RECHTS / ANTIFASCHISMUS / RECHTE

(Zur geistigen Lage der deutschen Gesellschaft)

Rechenschaftsbericht 2018 (II) – Januar bis April

von Götz Kubitschek

https://sezession.de/60034/rechenschaftsbericht-2018-ii-januar-bis-april

(Billige „Antifa“-Mobber und -Diskriminierer geben sich erneut als „Künstler“ aus) Kampagne gegen Rechts

„Zentrum für politische Schönheit“ ruft zur Denunziation auf https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/zentrum-fuer-politische-schoenheit-ruft-zur-denunziation-auf/

„Zentrum für politische Schönheit“

„Soko Chemnitz“ beschäftigt Justiz und Politik

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/soko-chemnitz-beschaeftigt-justiz-und-politik/

„Soko Chemnitz“

„Zentrum für politische Schönheit“ schaltet Online-Pranger ab https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/zentrum-fuer-politische-schoenheit-schaltet-online-pranger-ab/

„Zentrum für Politische Schönheit“

Jagd auf Andersdenkende

von Boris T. Kaiser

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/jagd-auf-andersdenkende/

Neuer Totalitarismus

Mein Künstler, dein Spitzel

von Thorsten Hinz

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/mein-kuenstler-dein-spitzel/

(ähnliches Kaliber)

Coca-Cola-Werbung gegen die AfD? Das steckt hinter dem Plakat in Berlin https://www.gmx.net/magazine/panorama/coca-cola-werbung-a... https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/linker-adventskalender-ruft-zu-anti-afd-aktionen-auf/

Anti-Rechts-Broschüre

Sachsens Kultusminister kritisiert Amadeu-Antonio-Stiftung https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/sachsens-kultusminister-kritisiert-amadeu-antonio-stiftung/

Amadeu-Antonio-Stiftung

Zopf-Alarm und Nazi-Wahn

von Felix Krautkrämer

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/zopf-alarm-und-nazi-wahn/

(Das war zu erwarten gewesen...)

Neuer Verfassungsschutzpräsident

Haldenwang will AfD beobachten lassen

https://www.n-tv.de/politik/Haldenwang-will-AfD-beobachten-lassen-article20759584.html

Nach Wechsel an der Spitze

Medienbericht: Verfassungsschutz will AfD beobachten

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/medienb...

Nach „Prüffall“

AfD Thüringen klagt gegen Landesverfassungsschutz https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/afd-thueringen-klagt-gegen-landesverfassungsschutz/

(Der Verfassungsschutz hat ja nun mit der AfD zu tun...) Keine Überwachung

Bericht: Ditib nicht mehr im Visier des Verfassungsschutzes https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/bericht-ditib-nicht-mehr-im-visier-des-verfassungsschutzes/

Bürgerliche Offensive

Kampfansage an die linke Einäugigkeit

https://www.welt.de/regionales/nrw/article184778062/Kampfansage-an-die-linke-Einaeugigkeit.html

Hamburger Menetekel

„Rechts ist die Hölle – links ist der Himmel – in der Mitte ist nichts“

https://www.tichyseinblick.de/kolumnen/spahns-spitzwege/r...

(Angesichts solcher Radikalisierung wird es Zeit für ein SPD-Verbot...) SPD-Politiker Kahrs fordert AfD-Verbot

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/spd-politiker-kahrs-fordert-afd-verbot/

Kind eines AfD-Politikers abgelehnt

Linksgrüne Sippenhaft an der Waldorfschule

von Michael Paulwitz

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/linksgruene-sippenhaft-an-der-waldorfschule/

Streit um AfD-Politikerkind

Eine Waldorfschule braucht Nachhilfe in Demokratie Ob privat oder öffentlich – Schulen dürfen niemanden diskriminieren. Die Ausgrenzung der Rechten nimmt seltsame Züge an.

https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/streit-um-afd-politikerkind-eine-waldorfschule-braucht-nachhilfe-in-demokratie/23765516.html

Die Entscheidung der Berliner Waldorfschule & die Folgen Die neuen Nazis sind totalitäre „Gutmenschen“

http://www.pi-news.net/2018/12/die-neuen-nazis-sind-totalitaere-gutmenschen/

Baden-Wüttemberg

AfD-Abgeordneter darf keine Weihnachtsgeschichte vorlesen https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/afd-abgeordneter-darf-keine-weihnachtsgeschichte-vorlesen/

Traditioneller Adventskalender

Die Post beschenkt alle Bundestagsabgeordneten – fast alle https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/die-post-beschenkt-alle-bundestagsabgeordneten-fast-alle/

Oberverwaltungsgericht Rheinland-Pfalz

Reichsbürgern dürfen Waffen entzogen werden

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/reichsbuergern-duerfen-waffen-entzogen-werden/

Widerspruch zu Wagenknecht

Linkspartei-Chef Riexinger warnt vor deutschen „Gelbwesten“ https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/linkspartei-chef-riexinger-warnt-vor-deutschen-gelbwesten/

(Inner-Linker Konflikt. Vom „Tagesspiegel“ deshalb thematisiert, weil die Gruppe antijüdisch agiert.)

Gewalttätige Politsekte „Jugendwiderstand“

Maos Schläger aus Berlin-Neukölln

https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/gewalttaetige-politsekte-jugendwiderstand-maos-schlaeger-aus-berlin-neukoelln/23729980.html

Das erfolgreichste Programm „gegen Nazis“ in der Geschichte Deutschlands Die Identitären – ein notwendiger Perspektivwechsel

http://www.pi-news.net/2018/12/die-identitaeren-ein-notwe...

Rückblick & im Gespräch mit Weltenbrand

von Martin Sellner

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qI5mYpWu71E

(Berliner Urania untersagt Pressefreiheit)

Tagesdosis 4.12.2018 – Zensoren in die Produktion!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xVZ0-z8fFLQ

Skandal um rechte Chatgruppe: Landeskriminalamt ermittelt gegen Polizisten

https://www.gmx.net/magazine/politik/skandal-rechte-chatg...

(Und sofort wird aus der Chatgruppe in den Medien ein „rechtes Netzwerk“...) Rechtes Netzwerk in Frankfurter Polizei – Landeskriminalamt ermittelt

https://www.gmx.net/magazine/politik/rechtes-netzwerk-fra...

Hamburg

G20-Krawalle: Polizei veröffentlicht weitere Fahndungsbilder https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/g20-krawalle-polizei-veroeffentlicht-weitere-fahndungsbilder/

Frauenchiemsee

Schändung von Jodl-Grab: Täter verurteilt

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/schaendung-von-jodl-grab-taeter-verurteilt/

Linke Gewalt – Angriffe in Halle/Saale

https://sezession.de/59976/linke-gewalt-angriffe-in-halle-saale

Baden-Württemberg

Sitzbank-Wurf gegen Auto von AfD-Abgeordneten: Polizei ermittelt

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/sitzban...

Rosenheim: Antifa will AfD-Büro stürmen

http://www.pi-news.net/2018/12/rosenheim-antifa-will-afd-buero-stuermen/

Rosenheim

Antifa stürmt AfD-Büro – Polizei schreitet ein

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H3oBbHOM0wQ

EINWANDERUNG / MULTIKULTURELLE GESELLSCHAFT

Der Migrationspakt als Elitenprojekt

https://sezession.de/59954/der-migrationspakt-als-elitenprojekt

UN-Migrationspakt: Hetze statt Fakten

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T3fW9rARIwY

„Lügen- und Angstkampagne“

Auswärtiges Amt beklagt Propagandafeldzug gegen Migrationspakt https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/auswaertiges-amt-beklagt-propagandafeldzug-gegen-migrationspakt/

Wohlstand migrieren, nicht Menschen!

„Eine humanistische Kritik am Wesen der Migration ist längst überfällig“, erklärt Autor und Rubikon-Beiratsmitglied Hannes Hofbauer im Exklusiv-Interview.

https://www.rubikon.news/artikel/wohlstand-migrieren-nicht-menschen

Auftritt bei UN-Migrationsgipfel

Merkel beklagt gezielte Falschmeldungen

https://www.n-tv.de/politik/Merkel-beklagt-gezielte-Falschmeldungen-article20764431.html

Kritik am Migrationspakt ist eine Mischung aus Lügen und Hetze! Das behauptet jedenfalls Angela Merkel. Was erlauben diese Frau!!!?

http://antides.de/was-erlauben-diese-frau

Kampagne gegen UN-Migrationspakt

Was bleibt? Der Tag nach Marrakesch

von Matthias Moosdorf

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/was-bleibt-der-tag-nach-marrakesch/

UN-Migrationspakt

Menetekel von Marrakesch

von Dieter Stein

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/menetekel-von-marrakesch/

UNHCR-Vertreter: Andere Staaten sollen sich an Deutschland orientieren https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/unhcr-vertreter-andere-staaten-sollen-sich-an-deutschland-orientieren/

Integrationsministerin Anne Spiegel

Grünen-Politikerin fordert Einwanderungskultur

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/gruenen-politikerin-fordert-einwanderungskultur/

Zurückweisungen an der Grenze

Seehofers Rückführungsabkommen erweisen sich als Luftnummer https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2019/seehofers-rueckfuehrungsabkommen-erweisen-sich-als-luftnummer/

„Politische Angriffe“: Flüchtlingsorganisation gibt „Aquarius“ auf https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/politische-angriffe-fluechtlingsorganisation-gibt-aquarius-auf/

Flüchtlingsbetreuer

Die politisch-korrekte Schweigespirale durchbrechen https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/die-politisch-korrekte-schweigespirale-durchbrechen/

Fahndungserfolg

Grenzkontrollen lohnen sich

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/grenzkontrollen-lohnen-sich/

Die Reisen der „Immigranten“ – unter der Lupe betrachtet Wem nützt es? So ein Migrationszug muss geplant und von langer Hand organisiert werden, das sagt einem schon der gesunde Menschenverstand. Diese Leute müssen wochenlang verpflegt werden, sie müssen Schlaf- und Waschgelegenheiten haben (Klos nicht zu vergessen), sie müssen Wäsche zum Wechseln haben ... Einige Überlegungen zur „Migration“.

https://www.epochtimes.de/meinung/gastkommentar/die-reisen-der-immigranten-unter-der-lupe-betrachtet-a2726033.html

(Die Wirtschaft will Einwanderung...)

Arbeitgeberpräsident hält Integration von Einwanderern für gelungen https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/arbeitgeberpraesident-haelt-integration-von-einwanderern-fuer-gelungen/

Ulrich Vosgerau zu Asylwahnsinn & Meinungsterror

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wklUR7i3beE

Moslems im Schwimmbad

Timke: Unsere Regeln dürfen nicht zur Disposition gestellt werden https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/timke-unsere-regeln-duerfen-nicht-zur-disposition-gestellt-werden/

Mangelnde Integration

Schröder wirft moslemischen Männern Gewaltproblem vor https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/schroeder-wirft-moslemischen-maennern-gewaltproblem-vor/

OECD-Bericht

Jeder siebte Zuwanderer in Deutschland hat nur Grundschulniveau https://www.welt.de/wirtschaft/article185252246/OECD-Jeder-siebte-Zuwanderer-hat-nur-Grundschulniveau.html

Grabschattacken

Sexuelle Belästigung: Flüchtlingsblogger Aras B. Zu Sozialstunden verurteilt https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/sexuelle-belaestigung-fluechtlingsblogger-aras-b-zu-sozialstunden-verurteilt/

Nach Verurteilung

Der jähe Absturz des Vorzeige-Migranten

von Boris T. Kaiser

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/der-jaehe-absturz-des-vorzeige-migranten/

Nach Suchaktion

Vermisste 17-Jährige tot in Flüchtlingsheim in Sankt Augustin gefunden https://www.ksta.de/region/rhein-sieg-bonn/sankt-augustin/nach-suchaktion-vermisste-17-jaehrige-tot-in-fluechtlingsheim-in-sankt-augustin-gefunden-31681748

Vorfall in Sankt Augustin

Starb die 17-jährige Elma C., weil sie ihren neuen Freund beleidigte? https://www.focus.de/panorama/welt/vorfall-in-sankt-augustin-starb-die-17-jaehrige-elma-c-weil-sie-ihren-neuen-freund-beleidigte_id_10021376.html

Baden-Württemberg

Mißbrauch von zwei Mädchen: Polizei nimmt Nordafrikaner fest https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/missbrauch-von-zwei-maedchen-polizei-nimmt-nordafrikaner-fest/

Oberösterreich

Mord an 16jähriger: Tatverdächtiger Afghane auf der Flucht

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/mord-an-16j...

Nordrhein-Westfalen

Kurdisch-libanesische Hochzeit sorgt für Großeinsatz https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/kurdisch-libanesische-hochzeit-sorgt-fuer-grosseinsatz/

Schwere Krawalle in Ankerzentrum in Bamberg: Elf Verletzte, neun Festnahmen https://www.gmx.net/magazine/panorama/schwere-krawalle-ankerzentrum-bamberg-verletzte-festnahmen-33460966

Festnahme in Deutschland

Serienvergewaltigung erschüttert Finnland

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/ausland/2018/serienvergewaltigung-erschuettert-finnland/

Opfer von mildem Urteil enttäuscht

Mann ins Koma geprügelt: Schläger müssen nicht in den Knast https://www.op-online.de/region/langen/egelsbacher-koma-gepruegelt-keine-schlaeger-muss-knast-10848521.html

Neuer Asylantrag

Abgeschobener Rädelsführer von Ellwangen zurück in Deutschland https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/abgeschobener-raedelsfuehrer-von-ellwangen-zurueck-in-deutschland/

KULTUR / UMWELT / ZEITGEIST / SONSTIGES

Kunsthistoriker sieht Nervosität bei Entscheidungsträgern Kommt jetzt doch kein Kreuz auf das Berliner Stadtschloss? Das Berliner Stadtschloss wird originalgetreu nachgebaut – die Frage ist nur: Mit dem Kreuz, das früher auf der Kuppel war? Oder ohne? Die Frage schien geklärt – und bricht jetzt doch wieder auf.

https://www.katholisch.de/aktuelles/aktuelle-artikel/kommt-jetzt-doch-kein-kreuz-auf-das-berliner-stadtschloss?utm_source=aktuelle-artikel&utm_medium=Feed&utm_campaign=RSS

(...Oder die vom Nachkriegs-Wiederaufbau verschonte Stadt...) Die vom Krieg verschont gebliebene Stadt Köln

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=153&v=oXAoEnUotOc

(Ende des Moderne-Hypes auf dem Kunstmarkt?)

Villa Grisebach in Berlin : Freud und Leid des Auktionators am Pult http://www.faz.net/aktuell/villa-grisebach-in-berlin-freud-und-leid-des-auktionators-am-pult-12964876.html

(Hurra, es wurde wieder etwas gefunden...)

Kunsthalle Mannheim: NS-Raubkunst in grafischer Sammlung Die Detektivarbeit eines Provenienzforschers hat in der grafischen Sammlung der Mannheimer Kunsthalle einige Werke mit dubiosem Hintergrund zu Tage gefördert. Eine Radierung raubten die Nazis zweifelsfrei ihrem jüdischen Besitzer.

https://www.welt.de/regionales/baden-wuerttemberg/article185320820/Kunsthalle-Mannheim-NS-Raubkunst-in-grafischer-Sammlung.html

Braucht Dresden ein Bombenkriegs-Museum?

Ja!, sagt Dankwart Guratzsch, seiner Geburtsstadt, die er 1957 verließ, aufs Engste verbunden. Hier sollte am 13. Februar 2020, dem 75. Jahrestag der Zerstörung, der Startschuss für den Bau eines solchen Museums fallen. Einen Wunschstandort hat er auch schon.

http://www.dnn.de/Dresden/Lokales/Braucht-Dresden-ein-Bombenkriegs-Museum

Die USA-Lobby: Deutsche Staatsmedien im Fadenkreuz der Transatlantik-Gefolgsleute https://deutsch.rt.com/meinung/80182-usa-lobby-deutsche-staatsmedien-im-fadenkreuz-transatlantik/

Pressefreiheit adé – Frankreich führt Gesetz gegen „Fake News“ ein! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3cESV87dFWg&t=

Manipulation durch Reporter

SPIEGEL legt Betrugsfall im eigenen Haus offen

http://www.spiegel.de/kultur/gesellschaft/fall-claas-relotius-spiegel-legt-betrug-im-eigenen-haus-offen-a-1244579.html

„Spiegel“-Skandal um Claas Relotius

Geliefert wie gewünscht

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/geliefert-wie-gewuenscht/

Die und wir – erbärmlich versus konstruktiv

https://sezession.de/60014/die-und-wir-erbaermlich-versus-konstruktiv

Der Fall Relotius: Es ist ein Stein ins Lügenmeer gefallen https://www.achgut.com/artikel/der_fall_relotius_es_ist_ein_stein_in_luegenmeer_gefallen

Medien: Haltung statt Wahrheitssuche

Die FakeNews beim SPIEGEL sind kein Einzelfall: Statt zu versuchen, der Wahrheit auf die Spur zu kommen, ersetzen Journalisten Recherche durch Haltung. Diese Einstellung droht den Journalismus in Verruf zu bringen – und FakeNews als Instrument der Denunziation fällt auf die Erfinder zurück.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e2MEzbLSfMg

(Weitere Fälle von Lügen in den etablierten Medien) Gerechtigkeit für Claas Relotius!

Wer über sehr viele ähnliche Medienfälle nicht reden will, der sollte über den Ex-SPIEGEL-Mann schweigen

von Alexander Wendt

https://www.publicomag.com/2018/12/gerechtigkeit-fuer-claas-relotius/?fbclid=IwAR2Y2NxIhKBHoaUJVcBmOiq52rm6pD8swOKoi_t_uKSRfOewHqRnSP7nI4I

(Vergangene Fälle von Lügen in den etablierten Medien) Der inszenierte Rassissmus

https://www.zeitenschrift.com/artikel/der-inszenierte-rassissmus

Skandal: MDR-Moderatorin berichtet wie Druck auf sie ausgeübt wurde um sie politisch............…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rtPTcgOfxQg

Patriotische Youtuber

Eine neue Form der Aufklärung

von Björn Harms

https://jungefreiheit.de/kultur/medien/2018/eine-neue-form-der-aufklaerung/

(Nach der Homo-Ehe der nächste Schritt zur „Ehe für alle“) Hochzeit kostete 15.000 Euro: Wie dieser Japaner eine Zeichentrickfigur geheiratet hat

https://rp-online.de/panorama/ausland/japaner-heiratet-ho...

Transfrau Angela Ponce bei Miss Universe: „Eine Lektion für die Welt“ https://web.de/magazine/unterhaltung/lifestyle/transfrau-angela-ponce-miss-universe-lektion-welt-33469342

Japaner heiratet Hologramm

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N2hsHndTkJA

Katja Kraus

Ex-Nationalspielerin will Frauenquote für Vorstände von Bundesliga-Klubs

https://jungefreiheit.de/kultur/2018/ex-nationalspielerin...

Viele Kinder wünschen sich vom Nikolaus ein Handy https://www.mittelhessen.de/hessen-welt/boulevard/vermischtes_artikel,-Viele-Kinder-wuenschen-sich-vom-Nikolaus-ein-Handy-_arid,1461022.html

Das wahre Gesicht der Jusos ist unmenschlich und radikal SPD-Jugendorganisation fordert die legale Tötung von Ungeborenen bis zur Geburt

https://www.freiewelt.net/nachricht/spd-jugendorganisatio...

(Keine Luftballons mehr)

Umweltschutz

Morgen Kinder wird’s was geben – oder auch nicht

https://jungefreiheit.de/kultur/2018/morgen-kinder-wirds-...

Nur noch St. Nikolaus ohne Rute

Grüne Landtagsabgeordnete will Knecht Ruprecht abschaffen http://www.pi-news.net/2018/12/gruene-landtagsabgeordnete... https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/gruenen-politikerin-warnt-vor-knecht-ruprecht/

Gedanken über den Krampus

von Martin Lichtmesz

https://sezession.de/59985/gedanken-ueber-den-krampus

Zum revolutionären Ikonoklasmus

Sonntagsheld (86) – Konterfei-Revolution

https://sezession.de/59952/sonntagsheld-86-konterfei-revolution

„Wie in 1930er Jahren“

Künstler Ai Weiwei beklagt Stimmungswandel in Deutschland https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/kuenstler-ai-weiwei-beklagt-stimmungswandel-in-deutschland/

(Bezeichnendes Psychogramm)

Multi-Kulti-Bezirk im Umbruch Berlin-Moabit: Total zentral, aber überhaupt nicht wie Mitte https://www.rbb24.de/politik/wahl/bundestag/beitraege/moabit-berlin-wahljahr-2017-reportage.html

Straßenzeitungen

Obdachlose akzeptieren bargeldlose Bezahlung

https://www.sueddeutsche.de/medien/strassenzeitungen-obdachlose-akzeptieren-bargeldlose-bezahlung-1.4238692

„Wenn es hier so scheiße ist, warum sind Sie dann hier?“ Klartext-Buch bringt Richter Dienstaufsichtsbeschwerde ein

https://jungefreiheit.de/politik/deutschland/2018/klartex...

Die ethnische Wahl

Martin Sellner

https://sezession.de/60002/die-ethnische-wahl

JF-TV Jahresrückblick 2018

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wci57ltyG4E

Zum 100. Geburtstag von Helmut Schmidt

„Der große Mann mit kleiner Wirkung“

von Karlheinz Weißmann

https://jungefreiheit.de/kultur/gesellschaft/2018/der-grosse-mann-mit-kleiner-wirkung/

Fleisch-Skandal in Deutschland : Die Verrohung des Schlachtens Metzger aus Osteuropa sind überfordert, Tiere bluten bei Bewusstsein aus – und das unter den Augen amtlicher Veterinäre. Was sind die Folgen des Schlachthof-Skandals?

https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/inland/fleisch-skanda...

Ausbreitung der Waschbären bedroht andere Arten 1,3 Millionen Waschbären gibt es mittlerweile in Deutschland, auch in Berlin vermehren sich die Tiere rasant. Artenschützer schlagen deshalb Alarm.

https://www.tagesspiegel.de/wissen/wildtiere-ausbreitung-der-waschbaeren-bedroht-andere-arten/23808538.html

(Andreas Gabalier)

„Volksrocker“ gegen linke Medien

A Meinung haben

von Boris T. Kaiser

https://jungefreiheit.de/debatte/kommentar/2018/a-meinung-haben/

17:58 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, presse, médias, journaux, allemagne, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 25 janvier 2019

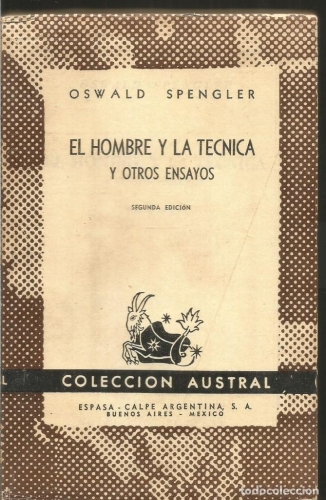

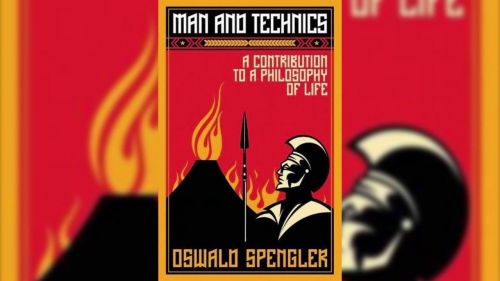

Tecnicidad, Biopolítica y Decadencia. Comentarios al libro "El Hombre y la Técnica" de Oswald Spengler.

Tecnicidad, Biopolítica y Decadencia.

Comentarios al libro "El Hombre y la Técnica" de Oswald Spengler.

Carlos Javier Blanco Martín

Resumen. El presente artículo es un comentario detenido de la pequeña obra de Oswald Spengler "El Hombre y la Técnica". En él desarrollamos el concepto de tecnicidad, necesario para comprender la amplia perspectiva (zoológica, naturalista, dialéctica, operatiológica) esbozada por el filósofo alemán. No se trata de un ensayo sobre la Técnica en el sentido artefactual y objetivo sino sobre el desarrollo de las capacidades operatorias (viso-quirúrgicas) de los ancestros del hombre, que lo llevaron desde la depredación hasta la Cultura, y desde la Cultura hasta la decadencia. Especialmente la decadencia de los pueblos occidentales que más han contribuido al despegue de esa tecnicidad.

Abstract. This article is a detailed commentary on Oswald Spengler's little work "The Man and the Technique". In it we develop the concept of technicality, necessary to understand the broad perspective (zoological, naturalistic, dialectic, operatiological) outlined by the German philosopher. This is not an essay on the Technique in the objective and artifactual sense, but rather on the development of the operative capacities (visual and manual) of the ancestors of man, which led him from predation to Culture, and from Culture to decline: especially the decadence of the western peoples that have contributed most to the takeoff of this technicality

Introducción. Justificación del presente comentario. Indagaciones sobre la Tecnicidad según Oswald Spengler.

En un trabajo anterior ya quisimos hacer una aproximación antropológica al concepto spengleriano de la Técnica[i] . El presente trabajo quiere ser una prolongación del mismo, profundizando en los conceptos spenglerianos sobre la tecnicidad y lo hacemos por medio de un comentario detenido de las páginas de su pequeña obra El Hombre y la Técnica.[ii] Este breve texto spengleriano aclara muchos aspectos de la filosofía, poco sistemática y, a veces, impresionista, del gran pensador alemán, el creador de la magna obra La Decadencia de Occidente. Este breve libro traza un cuadro evolutivo de la técnica en la historia natural y cultural del hombre. Pero hace algo más: esboza de una manera dialéctica el destino fatal de los pueblos de Occidente, pueblos que han desarrollado toda su tecnicidad hasta ponerla en manos de sus enemigos. Este examen detenido de los párrafos enérgicos y vibrantes del librito puede ayudar a comprender la peculiar dialéctica pesimista –a diferencia de la optimista hegeliana- del pensador alemán Oswald Spengler. En vez de alcanzar un progresivo dominio técnico del mundo, encaminado a su mayor comodidad y salud, el hombre y sus antepasados simplemente han ido diferenciando cualidades sensitivo-etológicas desde hace millones de años, cualidades en las que ya está presente la tecnicidad, aun cuando todavía nuestros antepasados no era capaces de fabricar herramientas, o sólo empleaban órganos y partes sensomotoras de su cuerpo para ejercer su dominio. Por ello, en nuestro comentario empleamos el término tecnicidad, contrapuesto a "técnica" para hacer referencia a esas capacidades generales implícitas a la hora de ejercer dominio, control o alteración del propio medio envolvente, con independencia de la existencia de herramientas, armas u otros objetos extra-somáticos. La tecnicidad es la cualidad o el carácter técnico de algo o alguien, y no se debe circunscribir a los productos de las artes humanas o proto-humanas ni al aspecto normativo o envolvente del Espíritu Objetivo. Nuestro comentario, pues, se enmarca en el espacio antropológico. Queremos ahondar en la antropología spengleriana, tal y como llevamos haciendo desde hace unos años. [iii]

En un trabajo anterior ya quisimos hacer una aproximación antropológica al concepto spengleriano de la Técnica[i] . El presente trabajo quiere ser una prolongación del mismo, profundizando en los conceptos spenglerianos sobre la tecnicidad y lo hacemos por medio de un comentario detenido de las páginas de su pequeña obra El Hombre y la Técnica.[ii] Este breve texto spengleriano aclara muchos aspectos de la filosofía, poco sistemática y, a veces, impresionista, del gran pensador alemán, el creador de la magna obra La Decadencia de Occidente. Este breve libro traza un cuadro evolutivo de la técnica en la historia natural y cultural del hombre. Pero hace algo más: esboza de una manera dialéctica el destino fatal de los pueblos de Occidente, pueblos que han desarrollado toda su tecnicidad hasta ponerla en manos de sus enemigos. Este examen detenido de los párrafos enérgicos y vibrantes del librito puede ayudar a comprender la peculiar dialéctica pesimista –a diferencia de la optimista hegeliana- del pensador alemán Oswald Spengler. En vez de alcanzar un progresivo dominio técnico del mundo, encaminado a su mayor comodidad y salud, el hombre y sus antepasados simplemente han ido diferenciando cualidades sensitivo-etológicas desde hace millones de años, cualidades en las que ya está presente la tecnicidad, aun cuando todavía nuestros antepasados no era capaces de fabricar herramientas, o sólo empleaban órganos y partes sensomotoras de su cuerpo para ejercer su dominio. Por ello, en nuestro comentario empleamos el término tecnicidad, contrapuesto a "técnica" para hacer referencia a esas capacidades generales implícitas a la hora de ejercer dominio, control o alteración del propio medio envolvente, con independencia de la existencia de herramientas, armas u otros objetos extra-somáticos. La tecnicidad es la cualidad o el carácter técnico de algo o alguien, y no se debe circunscribir a los productos de las artes humanas o proto-humanas ni al aspecto normativo o envolvente del Espíritu Objetivo. Nuestro comentario, pues, se enmarca en el espacio antropológico. Queremos ahondar en la antropología spengleriana, tal y como llevamos haciendo desde hace unos años. [iii]

- El concepto de tecnicidad.

Spengler comienza su estudio sobre la técnica mostrando su olímpico desprecio hacia las charlas del siglo XVIII y XIX sobre la "cultura". Desde las robinsonadas al mito del "buen salvaje", los "hombres de cultura" que habían llenado los salones europeos de aquellos años habían olvidado por completo el verdadero papel de la técnica en la civilización. El arte, la poesía, la novela, la cultura entendida como segunda naturaleza sublime del hombre, relumbraban en la mente de ilustrados y románticos, y con ese resplandor se cegaban a las realidades terribles de que estaba preñado el siglo XX, cuando el contexto geopolítico, social y económico ya había mutado por completo y la Ilustración o el romanticismo sólo habitaba en la mente retardataria de los demagogos y los "intelectuales", no en los hombres fácticos y de acción. El escalpelo de Spengler se extiende hasta los utilitaristas ingleses. Para ellos la técnica era el recurso idóneo para instaurar la holgazanería en el mundo:

Aber nützlich war, was dem »Glück der Meisten« diente. Und Glück bestand im Nichtstun. Das ist im letzten Grunde die Lehre von Bentham, Mill und Spencer. Das Ziel der Menschheit bestand darin, dem einzelnen einen möglichst großen Teil der Arbeit abzunehmen und der Maschine aufzubürden. Freiheit vom »Elend der Lohnsklaverei« und Gleichheit im Amüsement, Behagen und »Kunstgenuß«: das »panem et circenses« der späten Weltstädte meldet sich an. Die Fortschrittsphilister begeisterten sich über jeden Druckknopf, der eine Vorrichtung in Bewegung setzte, die – angeblich – menschliche Arbeit ersparte. An Stelle der echten Religion früher Zeiten tritt die platte Schwärmerei für die »Errungenschaften der Menschheit«, worunter lediglich Fortschritte der arbeitersparenden und amüsierenden Technik verstanden wurden. Von der Seele war nicht die Rede.

"Útil, empero, era lo que sirve a la "felicidad del mayor número". Y esta felicidad consistía en no hacer nada. Tal es, en último término, la doctrina de Bentam, Mill y Spencer, El fin de la Humanidad consistía en aliviar al individuo de la mayor cantidad posible de trabajo, cargándola a la máquina. Libertad de "la miseria, de la esclavitud asalariada" [Elend der Lohnsklaverei] e igualdad en diversiones, bienandanza y “deleite artístico”. Anúnciase el panem et circenses de las urbes mundiales en las épocas de decadencia. Los filisteos de la cultura se entusiasmaban a cada botón que ponía en marcha un dispositivo y que, al parecer, ahorraba trabajo humano. En lugar de la auténtica religión de épocas pasadas, aparece el superficial entusiasmo “por las conquistas de la Humanidad” [Errungenschaften der Menschheit], considerando como tales exclusivamente los progresos de la técnica, destinados a ahorrar trabajo y a divertir a los hombres. Pero del alma, ni una palabra." [iv]

La técnica para el utilitarismo inglés era vista como instancia ahorradora de trabajo, como mera herramienta liberadora de esclavitud del trabajo asalariado, pero no como la esencia misma del hombre fáustico, del hombre que transforma el mundo, que lo modifica substancialmente. Oswald Spengler repudia con toda su rabia y fuerzas ese sentimentalismo vulgar que arranca de Rousseau, de los románticos y también de los "progresistas". Un sentimentalismo que reduce la filosofía de la Historia a mero "optimismo", esto es, un estado de ánimo confiado y tranquilizador en el cual ya no habrá más guerras ni dominaciones de unos pueblos sobre otros. Un estado de quietud que, al modo más nietzscheano, Spengler intuye como deprimente, laminador, una antesala de un suicidio colectivo, un estado alienado y de falsedad. La Historia de los hombres sigue su curso con completa independencia de sus deseos, anhelos y expectativas. Como acontece con las leyes de la naturaleza, inexorables y devoradoras de civilizaciones, razas y universos enteros, las "leyes" de la historia siguen su marcha con independencia absoluta de nuestra mente.

Para comprender los tiempos, al hombre, a la vida que nos toca –históricamente- vivir, se precisa de una facultad especial, el "tacto fisiognómico":

Der physiognomische Takt, wie ich das bezeichnet habe, was allein zum Eindringen in den Sinn alles Geschehens befähigt, der Blick Goethes, der Blick geborener Menschenkenner, Lebenskenner, Geschichtskenner über die Zeiten hin erschließt im einzelnen dessen tiefere Bedeutung.

"El tacto fisiognómico, como he denominado la facultad que nos permite penetrar en el sentido de todo acontecer; la mirada de Goethe, la mirada de los que conocen a los hombres y conocen la vida, y conocen la Historia y contemplan los tiempos, es la que descubre en lo particular su significación profunda" [v].

El naturalismo, el determinismo, de la misma manera que el "culturalismo", se mostrarán incapaces de comprender el significado de la técnica en la historia de los hombres. Hace falta el tacto fisiognómico, es preciso sentir esa especie de empatía o intuición hacia lo que hacen las distintas clases de hombres, para así poder insertar adecuadamente el papel de la técnica en la cultura. La técnica no es la pariente pobre de la Cultura. No se trata de la versión ínfima de "cuanto puede hacer el Homo sapiens". Esta especie "sapiente" que construye catedrales góticas, compone sinfonías, escribe El Quijote, la Suma Teológica o la Ilíada, es también la especie que ha comenzado empuñando palos, forjado espadas o construido cañones anti-aéreos. La técnica –y de entre ella, la técnica depredatorio-bélica- sería la versión grisácea, deprimente, prosaica de la sublime Cultura. El naturalismo verá la evolución desde la maza asesina hasta el cohete espacial (recordemos la genial escena cinematográfica de Stanley Kubrick en 2001, Una Odisea Espacial). El determinismo, cercano al naturalismo y, a veces, complementario de éste, verá en la técnica una condición sine qua non de la Cultura sublime, condición que habrá que retirar del escenario convenientemente cuando ya actúe la Cultura sublime (Bellas Artes, Poesía, Espíritu, etc.). Finalmente, el "culturalismo", que Spengler detesta, pues representa el idealismo y la ceguera ignorante de los "literatos", escinde en dos la vida humana, una mitad sublime y otra prosaica; la mitad "prosaica" es condenada a la oscuridad por el idealismo rampante (pero también por el utilitarismo y el materialismo dialéctico) una vez que ha brotado la Cultura. Pero he aquí que el Filósofo de la Historia no puede ni debe dejar de lado aquello que es consustancial a la vida humana en su devenir. La técnica, reivindicada ahora por Spengler desde un naturalismo mucho más profundo, es esencial a la vida misma de todos los animales. La técnica no es la colección de "cosas" que ha producido el hombre para matar, destruir, crear, dominar. La técnica no se deja reducir a un estudio "supra-orgánico", "extra-somático", "objetivo". En la propia organicidad animal ya está presente la técnica:

Das ist der andre Fehler, der hier vermieden werden muß: Technik ist nicht vom Werkzeug her zu verstehen. Es kommt nicht auf die Herstellung von Dingen an, sondern auf das Verfahren mit ihnen, nicht auf die Waffe, sondern auf den Kampf

Das ist der andre Fehler, der hier vermieden werden muß: Technik ist nicht vom Werkzeug her zu verstehen. Es kommt nicht auf die Herstellung von Dingen an, sondern auf das Verfahren mit ihnen, nicht auf die Waffe, sondern auf den Kampf

"Este es el otro error que debe evitarse aquí: la técnica no debe comprenderse partiendo de la herramienta. No se trata de la fabricación de cosas, sino del manejo de ellas; no se trata de las armas, sino de la lucha."[vi]

La técnica no es la herramienta [Werkzeug], una suerte de prolongación extra-somática y objetiva del sujeto humano. La técnica, en realidad, es el manejo [Verfahren] con las cosas. Este es el corazón del comienzo del librito de Spengler: la técnica es la táctica de la vida. La vida no es una colección de cosas, a saber: sujetos corpóreos y objetos producidos por esos sujetos corpóreos. Esta sería la miope visión compartida al alimón por idealistas y por realistas. Los primeros se fijan en la "creatividad" del sujeto hacedor (se "crean" tanto obras de arte como misiles de cabeza nuclear), y los segundos paran mientes en lo creado. Pero en medio está la vida misma, la acción, a saber, el uso de los medios para la lucha.

- La Biopolítica spengleriana. Un naturalismo dialéctico.

La vida es comprendida como una guerra ya en sus más arcaicos estratos zoológicos.

Es gibt keinen »Menschen an sich«, wie die Philosophen schwatzen, sondern nur Menschen zu einer Zeit, an einem Ort, von einer Rasse, einer persönlichen Art, die sich im Kampfe mit einer gegebenen Welt durchsetzt oder unterliegt, während das Weltall göttlich unbekümmert ringsum verweilt. Dieser Kampf ist das Leben, und zwar im Sinne Nietzsches als ein Kampf aus dem Willen zur Macht, grausam, unerbittlich, ein Kampf ohne Gnade.

"No existe el “hombre en sí” — palabrería de filósofos —, sino sólo los hombres de una época, de un lugar, de una raza, de una índole personal, que se imponen en lucha con un mundo dado, o sucumben, mientras el universo prosigue en torno su curso, como deidad erguida en magnífica indiferencia. Esa lucha es la vida; y lo es, en el sentido de Nietzsche, como una lucha que brota de la voluntad de poderío; lucha cruel, sin tregua; lucha sin cuartel ni merced" [vii] .

Si Spengler rechaza tanto el idealismo como el realismo en su tratamiento de la técnica, otro tanto se ha de decir de la "antropología predicativa". "El hombre"… ¿qué es? Si hablamos de un Homo faber –hombre fabricante- pensado con el mismo formato que el concepto de Homo sapiens, sapiente, estamos eligiendo un predicado esencial que definirá a esta especie animal concreta a la que pertenecemos. Hay poca ganancia con respecto a estas antropologías tradicionales si al Homo, a nuestro género, le añadimos el predicado de "animal técnico". No existe el "hombre en sí" [Es gibt keinen »Menschen an sich«]. No hay tal cosa previamente definida, recortada, a la cual podamos asignarle (casi, podríamos decir "inyectarle") la cualidad esencial de su tecnicidad, de la misma manera que antaño se decía del hombre que era un "animal social" o "animal racional". No hay que hablar de tecnicidad de ese "Hombre" pre-dado . De lo que se ha de hablar es de una lucha cósmica eterna, en la que se insertan los seres vivos de todas las escalas zoológicas. A las enormes galaxias y a los descomunales astros les resulta por completo indiferente el resultado de esta minúscula guerra, una contienda ésta que para sus héroes y víctimas sin embargo les es esencial. La antroposfera de éste diminuto planeta es una capa extrafina y efímera que nada importa en el decurso del universo. Los hombres mueren por "pequeñas cosas" desde el punto de vista cósmico, aun cuando esas "pequeñeces" como la defensa de la patria, la preservación de un ideal, de una civilización o una fe comporten un valor infinito a los actores humanos.

Y estos supuestos valores supremos, relativos entre las mismas culturas humanas, y susceptibles de relativización a escalas supra-humanas, cósmicas, son en gran medida "mentira" si tras de ellos captamos su esencia: la voluntad de poder. En efecto, según Spengler, "el hombre es un animal de rapiña" [viii] [Denn der Mensch ist ein Raubtier.]. Depredador, es la palabra castellana que de la manera más neutra y zoológica describe nuestra condición. A años luz nos hallamos de los herbívoros. La clave de nuestra evolución como primates estriba en la depredación. El hombre como depredador encarna un estilo de vida, una complexión físico-espiritual que los métodos naturalistas groseros no podrán captar. Sabido es que Spengler apuesta por el naturalismo de Goethe y de la fisiognómica, y no por el materialismo de Linneo y de Darwin. Las "ciencias de la vida" estudian cadáveres y compuestos físico-químicos, diseccionan y clasifican, buscan causas deterministas al modo mecanicista, pero renuncian y hasta desprecian "el tacto fisiognómico". Este tacto, imprescindible para la comprensión de la vida, nos da la clave de la tecnicidad. La clave consiste en una superación del carácter pasivo de los sujetos vivos. De la planta podemos decir que "en ella y en torno a ella está la vida" más que afirmar, propiamente, que es un ser vivo[ix]. En rigor, es un "escenario" [Schauplatz] de los procesos vivientes.

Eine Pflanze lebt, obwohl sie nur im eingeschränkten Sinne ein Lebewesen ist. In Wirklichkeit lebt es in ihr oder um sie herum. »Sie« atmet, »sie« nährt sich, »sie« vermehrt sich, und trotzdem ist sie ganz eigentlich nur der Schauplatz dieser Vorgänge, die mit solchen der umgebenden Natur, mit Tag und Nacht, mit Sonnenbestrahlung und der Gärung im Boden eine Einheit bilden, so daß die Pflanze selbst nicht wollen und wählen kann. Alles geschieht mit ihr und in ihr. Sie sucht weder den Standort, noch die Nahrung, noch die andere Pflanze, mit welcher sie die Nachkommen erzeugt. Sie bewegt sich nicht, sondern der Wind, die Wärme, das Licht bewegen sie.

"La planta vive; aunque sólo en sentido limitado, es un ser viviente. En realidad, más que vivir puede decirse que en ella y en torno a ella está la vida. “Ella” respira, “ella” se alimenta, “ella” se multiplica; y, sin embargo, no es propiamente más que el escenario de esos procesos, que constituyen una unidad con los procesos de la naturaleza circundante, con el día y la noche, con los rayos del sol y la fermentación del suelo; de suerte que la planta misma no puede ni querer ni elegir. Todo acontece con ella y en ella. Ella no busca ni su lugar propio, ni su alimento, ni las demás plantas con quienes engendra su sucesión. No se mueve, sino que son el viento, el calor, la luz, quienes la mueven." [x]

"La planta vive; aunque sólo en sentido limitado, es un ser viviente. En realidad, más que vivir puede decirse que en ella y en torno a ella está la vida. “Ella” respira, “ella” se alimenta, “ella” se multiplica; y, sin embargo, no es propiamente más que el escenario de esos procesos, que constituyen una unidad con los procesos de la naturaleza circundante, con el día y la noche, con los rayos del sol y la fermentación del suelo; de suerte que la planta misma no puede ni querer ni elegir. Todo acontece con ella y en ella. Ella no busca ni su lugar propio, ni su alimento, ni las demás plantas con quienes engendra su sucesión. No se mueve, sino que son el viento, el calor, la luz, quienes la mueven." [x]

La vida, pues, en su estrato ínfimo, vegetal, si bien es un entrecruzamiento de procesos vitales (ellos mismos activos), el sujeto o "escenario" donde acontecen consiste, no obstante, en un mero receptáculo dominado por la pasividad. La vida vegetal es sometimiento al mundo-entorno [umgebenden Natur], a la naturaleza envolvente. A su vez, la vida vegetal es el sustrato sobre el que se asienta la "vida movediza" [freibewegliche Leben], esto es, el Reino animal. El carácter móvil, auto-portátil por así decir, de la vida animal es ya una forma de libertad, de sobre-posición, por encima de la situación pasiva y sometida del vegetal. Pero la movilidad libre de las criaturas animales está, a su vez, dividida en dos escalones: la vida del herbívoro, hecha para huir, y la vida del carnívoro, para depredar.

Es a través de la primacía de alguno de los sentidos como se crea un mundo-entorno específico para cada uno de los dos escalones de lo animal. El oído para los herbívoros, nacidos para huir o caer como presas, y el ojo –la mirada- para los cazadores, los más libres y sagaces de entre los animales. Este predominio sensorial unilateral, según parece decirnos Spengler, determina los distintos mundos-entorno.

Erst durch die geheimnisvolle und von keinem menschlichen Nachdenken zu erklärende Art der Beziehungen zwischen dem Tier und seiner Umgebung mittels der tastenden, ordnenden, verstehenden Sinne entsteht aus der Umgebung eine Umwelt für jedes einzelne Wesen. Die höheren Pflanzenfresser werden neben dem Gehör vor allem durch die Witterung beherrscht, die höheren Raubtiere aber herrschen durch das Auge. Die Witterung ist der eigentliche Sinn der Verteidigung. Die Nase spürt Herkunft und Entfernung der Gefahr und gibt damit der Fluchtbewegung eine zweckmäßige Richtung von etwas fort.

"La misteriosa índole — por ninguna reflexión humana explicable — de las relaciones entre el animal y su contorno, mediante los sentidos palpadores, ordenadores e intelectivos, es la que convierte el contorno en un mundo circundante para cada ser en particular. Los herbívoros superiores son dominados por el oído y, sobre todo, por el olfato. Los rapaces superiores, en cambio, dominan por la mirada. El olfato es el sentido propio de la defensa. Por la nariz rastrea el animal el origen y la distancia del peligro, dando así a los movimientos de huida una dirección conveniente: la dirección que se aleja del peligro. [xi]

El "contorno" [Umgebung] al cual todavía se veía sometida la planta, es en el animal un mundo-entorno [Umwelt]. Cada especie animal lo percibe a su modo. Las teorías de von Uexküll, conocidas por Spengler, resuenan aquí. Pero ese mundo percibido de manera distinta por cada especie determina, a su vez, una básica relación de poder, la relación de dominante a dominado. De la Biología teórica se pasa recta y necesariamente a una Biopolítica. En la propia Biología teórica se pre-contiene la base zoológica del Poder. La mirada del animal de presa es ya una mirada que busca obtener botín y dominio, que fija rectilínea y frontalmente sus objetivos.

Para el depredador, "el mundo es la presa" [Die Welt ist die Beute]. Spengler nos describe así el origen de la Cultura, la raíz del mundo histórico específico del ser humano. Justamente como el hueso-maza, el arma letal en manos de un simio, se transforma en la película 2001 Una Odisea Espacial, en un artefacto cosmonáutico, la tecnicidad del hombre hunde sus raíces en el propio escalonamiento superior del ancestro, el homínida comedor y cazador de otros animales.

Ein unendliches Machtgefühl liegt in diesem weiten ruhigen Blick, ein Gefühl der Freiheit, die aus Überlegenheit entspringt und auf der größeren Gewalt beruht, und die Gewißheit, niemandes Beute zu sein. Die Welt ist die Beute, und aus dieser Tatsache ist letzten Endes die menschliche Kultur erwachsen

"Un sentimiento infinito de poderío palpita en esa mirada larga y tranquila; un sentimiento de libertad que brota de la superioridad y descansa en el mayor poder, en la certidumbre de no ser nunca botín ni presa de nadie. El mundo es la presa; y de este hecho, en último término, ha nacido toda la cultura humana." [xii]

Esa mirada poderosa, unida a ese sentimiento de poder, es el germen de la Historia. Y la Historia se individualiza. No se trata de una historia de las masas. Las masas no poseen la historia. Antes de alzarse culturas individualizadas, en la fase zoológica y pre-cultural, la Historia la hacen los individuos. El animal de presa destaca y se recorta ante el animal de rebaño. El herbívoro precisa de muchos como él, y entre ellos (como luego, en las sociedades de masas) una muchedumbre de iguales constituye ya el individuo. Ha de verse aquí, en El Hombre y la Técnica, no una teoría, en el sentido riguroso o científico, sino una analogía. Spengler discurre por analogías, y esas analogías presiden toda su filosofía de la historia. Si una Cultura es, toda ella, un ser vivo dotado de su morfología propia y de su propio ciclo vital, un herbívoro es un análogo de un "hombre masa". El hombre masa del siglo XIX y XX es un retroceso hacia la animalización, pero hacia la animalización del escalón inferior, la de la presa, la del cobarde herbívoro.

Esa mirada poderosa, unida a ese sentimiento de poder, es el germen de la Historia. Y la Historia se individualiza. No se trata de una historia de las masas. Las masas no poseen la historia. Antes de alzarse culturas individualizadas, en la fase zoológica y pre-cultural, la Historia la hacen los individuos. El animal de presa destaca y se recorta ante el animal de rebaño. El herbívoro precisa de muchos como él, y entre ellos (como luego, en las sociedades de masas) una muchedumbre de iguales constituye ya el individuo. Ha de verse aquí, en El Hombre y la Técnica, no una teoría, en el sentido riguroso o científico, sino una analogía. Spengler discurre por analogías, y esas analogías presiden toda su filosofía de la historia. Si una Cultura es, toda ella, un ser vivo dotado de su morfología propia y de su propio ciclo vital, un herbívoro es un análogo de un "hombre masa". El hombre masa del siglo XIX y XX es un retroceso hacia la animalización, pero hacia la animalización del escalón inferior, la de la presa, la del cobarde herbívoro.

La analogía naturalista de Spengler discurre por canales muy diversos al naturalismo metafísico de Schopenhauer, aunque también conduce al pesimismo, o el de Darwin que induce a pensar en términos progresistas y, por ende, optimistas. El hombre es más que un mono. El hombre es más que un cuerpo que, por búsqueda de homologías rigurosas, esté próximo a los primates. La anatomía evolucionista, y, antes que ella, el comparatismo linneano, tratan ante todo con cadáveres. Los cuerpos estáticos de los científicos naturales son, en opinión de Spengler, naturalezas muertas. Frente a esta biología cadavérica Spengler busca el contacto con una filosofía de la biología de los cuerpos en acción. Tal concepción encuentra analogías en las acciones mismas. De tales analogías no hay razones para quejarse de un "antropomorfismo". Decir que es antropomorfismo que ciertos insectos "conocen la agricultura" o "practican la esclavitud", por ejemplo, sólo podría justificarse si admitiéramos que el hombre es un punto de vista privilegiado. De manera cerrada, y por tanto "ilógica", el círculo del antropomorfismo ve antropomorfismo en nuestras atribuciones acerca de las acciones de los animales. Lo que Spengler quiere decirnos simplemente es que la aparición de instituciones culturales, históricas, cuenta siempre con análogos zoológicos. El plano institucional en el que se puede hablar, como historiador, de una agricultura, una milicia, un Estado, una técnica, una esclavitud en una cultura humana es un plano que "corta" geométricamente con el plano zoológico y con el cual, al menos, hay una recta, una línea de puntos muy reales, donde también estarán presentes esos análogos.

- La tecnicidad y la analogía zoológica.

Ciñéndonos a la tecnicidad, Spengler la quiere ver en las más diversas escalas zoológicas, como ya llevamos visto. Pero no obstante se trata de una tecnicidad muy diversa. Y es que el método analógico, de gran aplicación en filosofías muy distintas a la spengleriana (p.e. en el tomismo) nos recuerda que la relación entre dos términos en parte distintos y en parte semejantes puede establecerse en orden a penetrar de alguna manera en un sector ignoto del mundo. Esta relación de analogía, y no de identidad, es legítima, cuidando de no bascular nunca hacia la univocidad ni hacia la equivocidad. Es una relación susceptible de quedar establecida en función de una proporción o regla. La técnica de los animales es análoga a la de los animales, pero no lo es en todos los aspectos ni en la misma medida. Los castores hacen presas y los ingenieros humanos también. Pero no igual, no en la misma medida. La tecnicidad del hombre es, por así decir, diferenciada. En el hombre se da la individualidad mientras que en el animal esa individualidad se pierde y se difumina en la especie:

Die Technik dieser Tiere ist Gattungstechnik.

"La técnica de los animales es técnica de la especie". [xiii]

La de los animales no humanos es técnica genérica (Gattung). Está incorporada en su instinto, y es invariable. El sujeto es aquí, como vimos en el caso de las plantas, un vehículo o escenario de la voz de la especie. Es una técnica no individualizada, invariable.[xiv]

Die Menschentechnik und sie allein aber ist unabhängig vom Leben der Menschengattung. Es ist der einzige Fall in der gesamten Geschichte des Lebens, daß das Einzelwesen aus dem Zwang der Gattung heraustritt. Man muß lange nachdenken, um das Ungeheure dieser Tatsache zu begreifen. Die Technik im Leben des Menschen ist bewußt, willkürlich, veränderlich, persönlich, erfinderisch. Sie wird erlernt und verbessert. Der Mensch ist der Schöpfer seiner Lebenstaktik geworden. Sie ist seine Größe und sein Verhängnis. Und die innere Form dieses schöpferischen Lebens nennen wir Kultur, Kultur besitzen, Kultur schaffen, an der Kultur leiden. Die Schöpfungen des Menschen sind Ausdruck dieses Daseins in persönlicher Form.

"La técnica humana, y sólo ella, es, empero, independiente de la vida de la especie humana. Es el único caso, en toda la historia de la vida, en que el ser individual escapa a la coacción de la especie. Hay que meditar mucho para comprender lo enorme de este hecho. La técnica en la vida del hombre es consciente, voluntaria, variable, personal, inventiva. Se aprende y se mejora. El hombre es el creador de su táctica vital. Esta es su grandeza y su fatalidad. Y la forma interior de esa vida creadora llamémosla cultura, poseer cultura, crear cultura, padecer por la cultura. Las creaciones del hombre son expresión de esa existencia, en forma personal."[xv]

El hombre es artífice de su táctica vital [Der Mensch ist der Schöpfer seiner Lebenstaktik geworden]. Esta palabra, "táctica", es crucial para comprender la gran analogía belicista que recorre por igual la filosofía de la naturaleza y la filosofía de la historia spenglerianas. De esa creación libre brota, no obstante, un plano nuevo de coacción y de condena sobre los aprendices de brujo que son los humanos. El Espíritu Objetivo podrá verse, hegelianamente, como un fruto de la libertad esencial de los hombres, pero, a la par, se alza como envoltorio determinante y coactivo que canaliza y bloquea los cursos en principio libres de los sujetos. Es una libertad que se auto-restringe al devenir objetivo. La cultura no es ya, sin más, el Reino de la Libertad confrontado al Reino de la Necesidad (material y físico-química). La optimista dualidad kantiana, como en general la optimista y felicitaría dualidad teológico-cristiana de la que partía, ya ha quedado atrás. De la cultura también procede un destino, una fatalidad [Verhängnis].

El hombre es artífice de su táctica vital [Der Mensch ist der Schöpfer seiner Lebenstaktik geworden]. Esta palabra, "táctica", es crucial para comprender la gran analogía belicista que recorre por igual la filosofía de la naturaleza y la filosofía de la historia spenglerianas. De esa creación libre brota, no obstante, un plano nuevo de coacción y de condena sobre los aprendices de brujo que son los humanos. El Espíritu Objetivo podrá verse, hegelianamente, como un fruto de la libertad esencial de los hombres, pero, a la par, se alza como envoltorio determinante y coactivo que canaliza y bloquea los cursos en principio libres de los sujetos. Es una libertad que se auto-restringe al devenir objetivo. La cultura no es ya, sin más, el Reino de la Libertad confrontado al Reino de la Necesidad (material y físico-química). La optimista dualidad kantiana, como en general la optimista y felicitaría dualidad teológico-cristiana de la que partía, ya ha quedado atrás. De la cultura también procede un destino, una fatalidad [Verhängnis].

- El hombre se ha hecho hombre por la mano.

Del carnívoro y depredador, cuyo órgano señorial es el ojo, pasamos al animal de la técnica en el sentido propio y formal, el animal que domina por medio de sus manos. Ese animal es ya el hombre. Dice Spengler que "el hombre se ha hecho hombre por la mano" [Durch die Entstehung der Hand.][xvi].

El ojo y la mano se complementan en lo que respecta a la dominación del mundo-entorno. El ojo domina desde el punto de vista teórico, y la mano desde el punto de vista práctico, nos dice el autor de El Hombre y la Técnica. El relato que nuestro filósofo nos brinda respecto a la aparición de la mano es de todo punto inaceptable. En el texto que comentamos se habla de una aparición repentina. A Spengler no se le pasa por la cabeza, al menos en relación con éste tema, la existencia de una causalidad circular alternativa a la "aparición súbita". La mano, junto con la marcha erguida, la técnica, la posición de la cabeza, etc. son novedades ellas que se podrían explicar de forma evolucionista pero no necesariamente en términos de sucesión lenta y gradual. En la antropología evolucionista se pueden establecer modelos de realimentación causal en donde las novedades "empujan" a otras, ofreciendo ventajas sinérgicas en cuanto a adaptación. Así parece haber sido el proceso de hominización, ciertamente un proceso acelerado, en donde el ritmo del cambio se hace vertiginoso. El papel de la mano en ese conjunto de procesos sinérgicos parece haber sido determinante. En esta misma revista hemos dado noticia de las investigaciones del profesor Manuel Fernández Lorenzo en ese sentido.[xvii]

Por el contrario, los prejuicios anti-evolucionistas de Spengler, y su apuesta por el mutacionismo de Hugo de Vries, hoy tan desacreditado, lastran la genial intuición. La mano hizo al hombre: he aquí una proposición que damos como cierta siempre y cuando no se oscurezcan las otras novedades bioculturales que, en sinergia con la conversión de la garra en mano, nos diferenciaron de manera muy notable dentro del grupo de los primates. Lo que Spengler ve como simultaneidad, nosotros deberíamos hoy analizarlo (con los enormes datos disponibles hoy por la paleoantropología, inexistentes en la época en que nuestro filósofo vivió) en términos de causalidad circular y sinérgica. De hecho, en el siguiente párrafo se podría vislumbrar este enfoque sustituyendo la simultaneidad repentina por este tipo de causalidad:

Aber nicht nur müssen Hand, Gang und Haltung des Menschen gleichzeitig entstanden sein, sondern auch – und das hat bis jetzt niemand bemerkt – Hand und Werkzeug. Die unbewaffnete Hand für sich allein ist nichts wert. Sie fordert die Waffe, um selbst Waffe zu sein. Wie sichdas Werkzeug aus der Gestalt der Hand gebildet hat, so umgekehrt die Hand an der Gestalt des Werkzeugs. Es ist sinnlos, das zeitlich trennen zu wollen. Es ist unmöglich, daß die ausgebildete Hand auch nur kurze Zeit hindurch ohne Werkzeug tätig war. Die frühesten Reste des Menschen und seiner Geräte sind gleich alt.