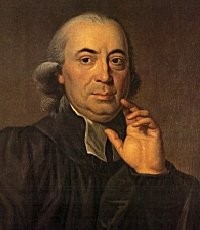

A medical student at the University of Königsberg in East Prussia in the 1760s, Herder quickly abandoned medicine for theology and philosophy, which brought him into contact with philosopher Immanuel Kant, one of his professors. To encourage Herder, his favorite pupil, Kant waived the fees customarily paid for attendance at his lectures, allowed the student to read some of his unpublished manuscripts, and introduced him to the writings of Montesquieu, Hume, and Rousseau.

Ordained in 1765, Herder became assistant master (teacher) at the Lutheran cathedral school in Riga. His religious works include Christian Writings (Christliche Schriften), 5 vols. (1794–98), Luther’s Catechism, with a catechetical instruction for the use of schools (1798), and On the Spirit of Hebrew Poetry (Vom Geist der hebräischen Poesie) (1782–3). According to Steven Martinson, the Lutheran pietism in which he was raised exhibited “a sense of equality among the ‘brothers’ and ‘sisters’ that carried over into Herder’s later understanding of community life.” Herder regretted that Martin Luther had not established a German national church. Christianity, he believed, had been (and should be) Germanized, just as other nations should adopt modifications of Christianity suitable to their own circumstances, ethnic consciousness, and experience.

Romantic Son of the Enlightenment

In Strasbourg he met Goethe, five years his junior, upon whom Herder’s ideas about poetry and its social role produced a powerful effect. Herder was a key figure, with Goethe and others, in the Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress) movement in German literature c. 1770–84.

Though a leader of the Romantics, Herder was nevertheless, according to Royal J. Schmidt, “a true son of the Aufklärung and seventeenth-century rationalism who was strongly influenced by the ideas of Leibniz, Kant, Spinoza, Montesquieu and Shaftesbury.” (“Cultural Nationalism in Herder,” Journal of the History of Ideas [June 1956], 407.) Because all human structures are transitory, Herder believed, tradition,

though in itself . . . an excellent institution of Nature, indispensable to the human race: but when it fetters the thinking faculty both in politics and education, and prevents all progress of the intellect, and all the improvement, that new times and circumstances demand, it is the true narcotic of the mind, as well to nations and sects, as to individuals.

In 1776, through Goethe’s influence, Herder was named Generalsuperintendent of the Lutheran clergy at Weimar, a post he held for the rest of his life.

A prolific author in many different fields (poetry, art, comparative philology and linguistics, religion, mythology, philosophy of history, metaphysics, psychology or philosophy of mind, aesthetics, and political philosophy), his books most relevant to this discussion are This Too a Philosophy of History for the Formation of Humanity (1774); Ideas for the Philosophy of History of Humanity (Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit), 4 vols. (1784–91), his masterwork, in which he discussed all known peoples; and Letters for the Advancement of Humanity (Briefe zur Beförderung der Humanität), 10 vols. (1793–7), a work largely of political philosophy written in response to the French Revolution.

A prolific author in many different fields (poetry, art, comparative philology and linguistics, religion, mythology, philosophy of history, metaphysics, psychology or philosophy of mind, aesthetics, and political philosophy), his books most relevant to this discussion are This Too a Philosophy of History for the Formation of Humanity (1774); Ideas for the Philosophy of History of Humanity (Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit), 4 vols. (1784–91), his masterwork, in which he discussed all known peoples; and Letters for the Advancement of Humanity (Briefe zur Beförderung der Humanität), 10 vols. (1793–7), a work largely of political philosophy written in response to the French Revolution.

Stylistically, according to Michael Forster [2] of the University of Chicago, Herder is “hostile towards systematicity in philosophy. He is in particular hostile to the ambitious sort of systematicity aspired to in the tradition of Spinoza, Wolff, Kant, Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel: the ideal of a comprehensive theory whose parts display some sort of strict overall pattern of derivation.” He was skeptical that such systematic designs could work, as opposed to creating the illusion that they do, and believed system-building closes off inquiry and disregards or distorts vital empirical evidence. Herder’s views “established an important countertradition in German philosophy (which subsequently included e.g. F. Schlegel, Nietzsche, and Wittgenstein).” He also harbored “a general commitment to empiricism and against apriorism in philosophy which leads him to avoid familiar sorts of apriorist arguments in philosophy.”

Herder and Biological Race

Herder was a key figure in the development of two well-known philosophical-anthropological concepts.

One is Zeitgeist (zeit time + geist spirit), “spirit of the time” or “spirit of the age,” signifying the general cultural, intellectual, ethical, spiritual, and political climate of an era. Herder reportedly coined the term in his 1769 critique of a work by German philologist Christian Adolph Klotz.

The second concept, the one relevant here, is Volksgeist, usually translated as “national spirit” or “national character.” In German, however, Nationalgeist is the term for national spirit, and Nationalcharakter for national character. Volksgeist means “spirit of the Volk.”

In a holistic sense, race consists of dimensions beyond physical anthropology or population genetics. Just as every distinct population shares common morphological and physiological traits, despite within-group variation they likewise express unique group psychology, intelligence, behavior, character, morals and, ultimately, culture and civilization. (Jared Taylor: “White Americans believed race was a fundamental aspect of individual and group identity. They believed people of different races differed in temperament, ability, and the kind of societies they built.”) In fact, such second-order phenomena are the aspects of race that preoccupy most “racists” most of the time.

Herder’s Volksgeist is highly compatible with this modern understanding of race. This is why he is frequently viewed as a “racist” by modern academics (e.g., Cedric Dover, “The Racial Philosophy of Johann Herder,” British Journal of Sociology [1952]: 124–33) or as a forerunner of Nazism. It is easy to see why this is the case.

German physical anthropologist Egon von Eickstedt maintained that Herder and Christoph Meiners (1747–1810) were the founders of the anthropological theory of history. Anthropologist Ilse Schwidetzky wrote that Herder “entertained the general conviction that the character of a people, and subsequently their history, is determined by their nature and heredity.”

However, Herder’s implicitly racial or ethnic understanding of Volk was not predicated upon a biological worldview, at least not an explicit one. Moreover, it reflected the biological confusion and limited scientific understanding of the time. As Oxford biologist John R. Baker noted, in Herder’s Ideas,

his arguments appear rather feeble and in places actually foolish. For instance, he says that all men are the same in internal anatomy, and even—almost unbelievably—that a few hundred years ago the inhabitants of Germany were Patagonians [natives of a region located at the southern tip of South America]. He mentions [Johann F.] Blumenbach [the German father of modern anthropology, who developed a 5-race model of mankind], but will not agree to the division of mankind into races. ‘Race [he uses this actual word] implies a difference of origin [i.e., not the Biblical creation],’ he claims; and this difference he denies. ‘Denn jedes Volk ist Volk,’ he insists; for him, the reality is not the race but the nation with its national speech.

Herder shows better sense than some of the philosophers of his time [Baker mentions Rousseau and several other eminent figures] in rejecting the idea that the anthropoid apes could be regarded as human. He tells us that nature has divided the apes and monkeys into many genera and species, but man is unitary. ‘Neither the Pongo [chimpanzee] nor the Longimanus [gibbon] is your brother; but truly the American [Amerindian] and the Negro are.

Herder’s religious convictions prevented him from classifying mankind with animals. He believed national groups belonged not to “systematic natural history,” but to “the physico-geographical history of man.” With Montesquieu, he viewed human populations as products of the lands they inhabited, the climates in which they developed, and the circumstances that shaped their respective histories:

The structure of the earth, in its natural variety and diversity . . . Seas, mountain ranges and rivers are the most natural boundaries not only of lands but also of peoples, customs, languages and empires, and they have been, even in the greatest revolutions in human affairs, the directing lines or limits of world history.

Yet, despite these caveats, Herder’s worldview was unmistakably racialist, as can be seen in his observations concerning the Chinese:

. . . show what kind of nation it is, and evince it’s genetic character: a character which equally meets the eye on contemplation of the whole, and inspection of its parts, even to dress, food, customs, domestic economy, arts, and amusements. This northeastern mungal [Mongol] nation could no more change its natural form by artificial regulations, even though enduring for thousands of years, than a man can change his nature, that is, the innate character of his race and complexion. It was planted on this spot of the Globe: and . . . this race of men, in this region, could never become Greeks or Romans. Chinese they were, and will remain: a people endowed by nature with small eyes, a short nose, a flat forehead, little beard, large ears, and a protuberant belly: what their organization could produce, it has produced. . . . Nature seems to have refused them as well as many other nations in this corner of the World, great invention in Science: while on the other hand he has beautifully conferred on their little eyes a spirit of application, adroit diligence and nicety, a talent of imitating with art whatever their cupidity deems useful. Eternally moving, eternally occupied, they are forever going and coming, in quest of gain, or in fulfillment of their offices. . . .

Elsewhere he makes the reverse case: “Had Greece been peopled with Chinese, our Greece would never have existed.”

Jacques Godechot, a French Jewish historian, wrote that for Herder “the destiny of national groups is fixed by imperatives beyond popular [i.e., political] modification. These imperatives are race (Herder did not formulate a theory of race, but to a certain extent he can be considered as a forerunner of modern racism), language, tradition, and natural frontiers.”

It can be said that Herder inserted a full-blown, de facto racial-ethnic view of history and mankind at a level one step above that of biology (race). In Herder’s treatment, at least, the consequences are much the same as they would be for a more biologically-oriented approach.

Still, rejection of, or lack of clarity about, basic raciology is best avoided. It leads whites badly astray, as witness the consequences of the petty but internecine nationalisms of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Volksgeist

The Volksgeist, the spirit of the folk, is a manifestation of the people; it animates the nation. “There is only one class in the state, the Volk (not the rabble), and the king belongs to this class as well as the peasant.” The Volksgeist is as old as the Volk, and evolves with the national group. There is a life of national groups, and withering and death marks the end of a Volk.

Every human group is, as an empirical matter, different from every other group, each nationality (or Volk) is characterized by its own unique spirit. Each people possesses its own cultural traits shaped by ancestral history and the experience of a particular physical environment, and mentally constructs its social life through language, literature, religion, the arts, customs, and folklore inherited from earlier generations. The Volk is the family writ large.

Law, too, must be adapted to the spirit of each nation, for rules applied to one nation are not valid for another. The only effective and legitimate governments are those that develop naturally from within particular nations and reflect, in their differences from other polities, the cultures of the people they govern.

It follows that two nations cannot have the same Volksgeist. Therefore, Herder rejected the French revolutionary (and contemporary) dogma that man is everywhere the same, whether he lives in Africa or England, or that every nation is fundamentally identical with every other nation, and thereby should be made homogeneous with them. Herder, Godechot writes, is staunchly opposed to all that is cosmopolite and universalist in character: “In contrast, he believes in particularism.”

Herder constantly likened the Volksgeist, “singular, marvelous, inexplicable, ineffable,” to a plant that grows, blooms, and withers. Just as the “botanist cannot obtain a complete knowledge of a plant, unless he follow it from the seed, through its germination, blossoming, and decay,” so too must the historian seek to understand the uniqueness of the present by reference to its roots in the past.

In other words, the Volksgeist can best be understood through the phenomena of history. Therefore, the study of history must play a central role in education. The objective of historical instruction, which should be nationalistic in character, is to teach how the Fatherland evolved over time.

Rather than giving priority to the study of ancient and modern history, as was common in the 18th century, Herder redeemed the history of the Middle Ages, feeling that it had been given short shrift. He also refused to restrict history to the study of politics, wars, and dynasties. For Herder, history was primarily the history of the Volk: its language, culture, customs, religion, literature, law, and folklore. (A writer and collector of poetry, folk songs, and legends, and an early student of comparative literature, Herder published a collection of folk songs in 1773 entitled Voices of the People in Their Songs [Stimmen der Völker in ihren Liedern].)

Rather than giving priority to the study of ancient and modern history, as was common in the 18th century, Herder redeemed the history of the Middle Ages, feeling that it had been given short shrift. He also refused to restrict history to the study of politics, wars, and dynasties. For Herder, history was primarily the history of the Volk: its language, culture, customs, religion, literature, law, and folklore. (A writer and collector of poetry, folk songs, and legends, and an early student of comparative literature, Herder published a collection of folk songs in 1773 entitled Voices of the People in Their Songs [Stimmen der Völker in ihren Liedern].)

Herder’s views of both the German and the Slavic Volksgeist did not match existing territorial borders, but were pan-national in character.

Despite being Prussian, Herder rejected Prussian nationalism as too narrow. An intense German nationalist, he was imbued with the spirit of the entire German Volk: “He is deserving of glory and gratitude who seeks to promote the unity of the territories of Germany through writings, manufacture, and institutions.” Herder believed that Austria, too, should be part of Germany.

Likewise, he conceived of Slavs as a Volk, rather than extolling specific polities. Thus, he wrote of the Slavic, as opposed to the Russian, Polish, or some other politically-defined Volksgeist. Herder predicted the Slavic nations would one day be the real power in Europe, as western Europeans would reject Christianity and rot away, while the eastern European nations would adhere to their religion and to their idealism. Through his concept of Volksgeist, which directly influenced Slavic intellectuals, and his high praise for the Slavic people and culture, Herder became an intellectual godfather of Pan-Slavism [4].

Herder rejected the mixture of Völker, each of which he believed was adapted to a particular ecological niche. Ideally, “if every one of these nations had remained in its place, the Earth might have been considered as a garden, where in one spot one human national plant, in another, another, bloomed in its proper figure and nature.” But just “as men are not firmly rooted plants, the calamities of famine, earthquakes, war and the like, must in time remove them from their place to some other more or less different.” Almost every people on Earth “has migrated at least once, sooner or later, to a greater distance, or less.”

On Language

For Herder, language became a key cultural differentiator and identifier:

Has a people anything dearer than the speech of its fathers? In its speech resides its whole thought-domain, its tradition, history, religion, and basis of life, all its heart and soul. To deprive a people of its speech is to deprive it of its one eternal good. . . . As God tolerates all the different languages in the world, so also should a ruler not only tolerate but honor the various languages of his peoples. . . . The best culture of a people cannot be expressed through a foreign language; it thrives on the soil of a nation most beautifully, and, I may say, it thrives only by means of the nation’s inherited and inheritable dialect. With language is created the heart of a people; and is it not a high concern, amongst so many peoples—Hungarians, Slavs, Rumanians, etc.—to plant seeds of well-being for the far future and in the way that is dearest and most appropriate to them?

Herder’s stress on the centrality of language, including dangerously divisive multilingual diversity within the white race, or even a single white state, impacted the development of European nationalism during the succeeding two centuries. (Linguistic diversity within multiracial states like the US is desirable because, genetically speaking, language barriers tend to hinder hybridization. You do not want anything like “English Only” in a multiracial milieu.) After Herder, European national languages assumed a heavily romanticized, mystical aura in nationalist thought. Worse, language was used as a poor stand-in for race in whites’ construction of their concepts of “people” and “nation” in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Madison Grant, Lothrop Stoddard, and others realized that race and language are not interchangeable, that language is not an adequate surrogate for race. Nor should language balkanize and divide whites, as it has to date. It is imperative that we transcend the currently impermeable linguistic barriers that seal whites into airtight national compartments, rendering us “foreign” and mutually unintelligible to one another. Rather, we must talk and move ceaselessly across the old territorial, linguistic, and intellectual borders as a prelude to full-fledged transnational white cooperation.

The Jews

In terms of religion, for Herder there was no continuity between (for him, legitimate) Old Testament Judaism and the Pharisaic Judaism of Jesus’ time, which he regarded as degenerate in form.

As far as ethnicity goes, Herder did not think of Jews primarily as individuals, but as a Volk. The Jews, he wrote, “in the land of their fathers, and in the midst of other nations . . . remain as they were; and even when mixed with other people they may be distinguished for some generations downward.” His view of Völker compelled him to regard Jews as alien to Germany and Europe:

For thousands of years, since their emergence on the stage of history, the Jews were a parasitic growth on the stem of other nations, a race of cunning brokers all over the earth. They have caused great evil to many ill-organized states, by retarding the free and natural economic development of their indigenous population.

In another passage reflective of Herder’s racial-ethnic worldview, he says:

The Jewish people is and remains in Europe an Asiatic people alien to our part of the world, bound to that old law which it received in a distant climate, and which, according to its confession, it cannot do away with . . . [Emphasis added.]

How many of this alien people can be tolerated without injury to the true citizens?

A ministry in which a Jew is supreme, a household in which a Jew has the key of the wardrobe and the management of the finances, a department or commissariat in which Jews do the principal business, are Pontine marshes which cannot be drained.

However, in the opinion of some Jews, Herder’s greatest sin was his formulation of the theory of the Volksgeist itself. David Isadore Lieberman, an anti-white publicist, writes:

Herder’s most important contribution to the intellectual history of antisemitism was entirely unintended: his novel argument for the organic development of national cultures, which incorporated elements of geography, language, kinship, and historical continuity. Although Herder maintained (with occasional lapses) that no culture enjoyed a privileged position with respect to any other, his model of the organic natural culture left Jews living in the Diaspora exposed, susceptible to charges that their culture was “inorganic” and therefore inauthentic.

This last sentence is dishonest or possibly ignorant. To Herder, Jews definitely constituted an organic, “authentic” Volk. (See Frederick M. Barnard, “The Hebrews and Herder’s Political Creed,” Modern Language Review [Oct. 1959], 533.) It would be correct to say that Herder’s model leaves Jews exposed to the charge of subverting and destroying—and today, committing genocide against—other authentic cultures and peoples.

Finally, Herder’s contention that “No nationality has been solely designated by God as the chosen people of the earth” must also be classified as anti-Semitic, flatly contradicting as it does the central dogma of Judaism, Jews, organized Jewry, and all governments today.

Editor’s Bibliographical Note

A number of Herder’s works are available in English translation:

Another Philosophy of History and Selected Political Writings [5] , ed. and trans. Ioannis D. Evrigenis and Daniel Pellerin (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2004)

, ed. and trans. Ioannis D. Evrigenis and Daniel Pellerin (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2004)

God, Some Conversations [6], trans. Frederick T. Burckhardt (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1940)

On the Origin of Language: Two Essays [7] (by Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Johann Gottfried von Herder), trans. John H. Moran and Alexander Gode (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986)

(by Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Johann Gottfried von Herder), trans. John H. Moran and Alexander Gode (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986)

On World History: An Anthology [8], ed. Hans Adler and Ernest A. Menze, trans. Ernest A. Menze and Michael Palmer (M. E. Sharpe, 1996)

Philosophical Writings [9] , ed. Michael N. Forster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002)

, ed. Michael N. Forster (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002)

Reflections on the Philosophy of the History of Mankind [10] (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968)

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968)

Sculpture: Some Observations on Shape and Form from Pygmalion’s Creative Dream [11], trans. Jason Gaiger (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002)

Selected Early Works, 1764-1767: Addresses, Essays, and Drafts; Fragments on Recent German Literature [12] , ed. Ernest A. Menze and Karl Menges, trans. Ernest A. Menze and Michael Palma (University Park, Penn.: Penn State Press, 1992)

, ed. Ernest A. Menze and Karl Menges, trans. Ernest A. Menze and Michael Palma (University Park, Penn.: Penn State Press, 1992)

Selected Writings on Aesthetics [13], ed. and trans. Gregory Moore (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006)

Shakespeare [14] , trans. Gregory Moore (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008)

, trans. Gregory Moore (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008)

The Spirit of Hebrew Poetry [15] (Toronto: University of Toronto Libraries, 2011).

(Toronto: University of Toronto Libraries, 2011).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg Der „Pariser Salonlöwe“ (WDR 5) und „Medienintellektuelle“ Bernard-Henri Lévy (BHL) gilt als einer eifrigsten Lautsprecher der Intervention in Libyen. Seine Reise im Osten Libyens Anfang März des Jahres, so will es die Fama, soll den Stein ins Rollen gebracht haben. Hier suchte er den Kontakt mit Anti-Gaddafi-Rebellen, um zu eruieren, wie glaubwürdig deren Absichten seien, den Despoten Gaddafi in die beziehungsweise – hier wohl angemessener – aus der Wüste zu jagen.

Der „Pariser Salonlöwe“ (WDR 5) und „Medienintellektuelle“ Bernard-Henri Lévy (BHL) gilt als einer eifrigsten Lautsprecher der Intervention in Libyen. Seine Reise im Osten Libyens Anfang März des Jahres, so will es die Fama, soll den Stein ins Rollen gebracht haben. Hier suchte er den Kontakt mit Anti-Gaddafi-Rebellen, um zu eruieren, wie glaubwürdig deren Absichten seien, den Despoten Gaddafi in die beziehungsweise – hier wohl angemessener – aus der Wüste zu jagen.

Les philosophes des Lumières vont progressivement faire de l’intérêt rationnel le seul véritable déterminant de la conduite humaine, dans le fil de Newton qui découvrit la loi de l’attraction universelle. Cette réduction de l’homme à son intérêt « bien compris », c’est-à-dire éclairé par les lumières de sa raison, débouche sur une « physique sociale » dont l’esprit des Lumières croit avoir découvert les lois indépassables. Et si tout homme est déterminé par sa nature à rechercher ce qui lui est utile, « alors l’échange économique devient l’exemple le plus net d’une relation humaine rationnelle » puisque chacun, au terme d’une négociation – un négoce – pacifique, est censé y trouver son compte.

Les philosophes des Lumières vont progressivement faire de l’intérêt rationnel le seul véritable déterminant de la conduite humaine, dans le fil de Newton qui découvrit la loi de l’attraction universelle. Cette réduction de l’homme à son intérêt « bien compris », c’est-à-dire éclairé par les lumières de sa raison, débouche sur une « physique sociale » dont l’esprit des Lumières croit avoir découvert les lois indépassables. Et si tout homme est déterminé par sa nature à rechercher ce qui lui est utile, « alors l’échange économique devient l’exemple le plus net d’une relation humaine rationnelle » puisque chacun, au terme d’une négociation – un négoce – pacifique, est censé y trouver son compte.

A prolific author in many different fields (poetry, art, comparative philology and linguistics, religion, mythology, philosophy of history, metaphysics, psychology or philosophy of mind, aesthetics, and political philosophy), his books most relevant to this discussion are This Too a Philosophy of History for the Formation of Humanity (1774); Ideas for the Philosophy of History of Humanity (Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit), 4 vols. (1784–91), his masterwork, in which he discussed all known peoples; and Letters for the Advancement of Humanity (Briefe zur Beförderung der Humanität), 10 vols. (1793–7), a work largely of political philosophy written in response to the French Revolution.

A prolific author in many different fields (poetry, art, comparative philology and linguistics, religion, mythology, philosophy of history, metaphysics, psychology or philosophy of mind, aesthetics, and political philosophy), his books most relevant to this discussion are This Too a Philosophy of History for the Formation of Humanity (1774); Ideas for the Philosophy of History of Humanity (Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit), 4 vols. (1784–91), his masterwork, in which he discussed all known peoples; and Letters for the Advancement of Humanity (Briefe zur Beförderung der Humanität), 10 vols. (1793–7), a work largely of political philosophy written in response to the French Revolution. Rather than giving priority to the study of ancient and modern history, as was common in the 18th century, Herder redeemed the history of the Middle Ages, feeling that it had been given short shrift. He also refused to restrict history to the study of politics, wars, and dynasties. For Herder, history was primarily the history of the Volk: its language, culture, customs, religion, literature, law, and folklore. (A writer and collector of poetry, folk songs, and legends, and an early student of comparative literature, Herder published a collection of folk songs in 1773 entitled Voices of the People in Their Songs [Stimmen der Völker in ihren Liedern].)

Rather than giving priority to the study of ancient and modern history, as was common in the 18th century, Herder redeemed the history of the Middle Ages, feeling that it had been given short shrift. He also refused to restrict history to the study of politics, wars, and dynasties. For Herder, history was primarily the history of the Volk: its language, culture, customs, religion, literature, law, and folklore. (A writer and collector of poetry, folk songs, and legends, and an early student of comparative literature, Herder published a collection of folk songs in 1773 entitled Voices of the People in Their Songs [Stimmen der Völker in ihren Liedern].)

Army geht, im Irak kämpft und unverkennbar nicht ohne Stolz die „Hurensöhne“ aufspürt und abknallt: „We found them and killed them, these sons of the bitches.“ Man stelle sich den bundesdeutschen Aufschrei vor, schriebe ein Künstler hierzulande derartige Textzeilen.

Army geht, im Irak kämpft und unverkennbar nicht ohne Stolz die „Hurensöhne“ aufspürt und abknallt: „We found them and killed them, these sons of the bitches.“ Man stelle sich den bundesdeutschen Aufschrei vor, schriebe ein Künstler hierzulande derartige Textzeilen.

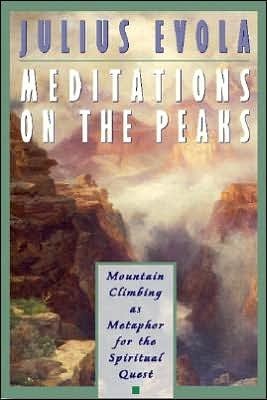

In un’occasione Evola cita la teoria giuridica di Carl Schmitt dell’international law . Il filosofo della politica tedesco aveva espresso l’idea della caduta del diritto internazionale europeo consuetudinario avvenuta, all’incirca, dopo il 1890, e la conseguente affermazione di un diritto internazionale più o meno ufficializzato. «Noi però qui non siamo interamente del parere dello Schmitt», scrive Evola, spiegando che «di contro all’opinione di molti, nei riguardi dell’azione svolta da Bismarck, sia all’interno della Germania che in Europa, non tutte le cose sono “in ordine”. […]. Più che Bismarck, a noi sembra che, se mai, Metternich sia stato l’ultimo “Europeo”, vale a dire l’ultimo uomo politico che seppe sentire la necessità di una solidarietà delle nazioni europee non astratta, o dettata solo da ragioni di politica “realistica” e da interessi materiali, ma rifacentesi anche a delle idee e alla volontà di mantenere il migliore retaggio tradizionale dell’Europa» . Contrariamente a quanto sostenuto da Baillet , Evola fu dunque piuttosto critico nei confronti di Bismarck, che non ebbe, secondo la visione tradizionale evoliana, il coraggio di opporsi in modo sistematico e rigoroso al mondo moderno e della sovversione (nella sua forma economico-capitalistica), ma dovette in alcuni casi venire a patti con esso.

In un’occasione Evola cita la teoria giuridica di Carl Schmitt dell’international law . Il filosofo della politica tedesco aveva espresso l’idea della caduta del diritto internazionale europeo consuetudinario avvenuta, all’incirca, dopo il 1890, e la conseguente affermazione di un diritto internazionale più o meno ufficializzato. «Noi però qui non siamo interamente del parere dello Schmitt», scrive Evola, spiegando che «di contro all’opinione di molti, nei riguardi dell’azione svolta da Bismarck, sia all’interno della Germania che in Europa, non tutte le cose sono “in ordine”. […]. Più che Bismarck, a noi sembra che, se mai, Metternich sia stato l’ultimo “Europeo”, vale a dire l’ultimo uomo politico che seppe sentire la necessità di una solidarietà delle nazioni europee non astratta, o dettata solo da ragioni di politica “realistica” e da interessi materiali, ma rifacentesi anche a delle idee e alla volontà di mantenere il migliore retaggio tradizionale dell’Europa» . Contrariamente a quanto sostenuto da Baillet , Evola fu dunque piuttosto critico nei confronti di Bismarck, che non ebbe, secondo la visione tradizionale evoliana, il coraggio di opporsi in modo sistematico e rigoroso al mondo moderno e della sovversione (nella sua forma economico-capitalistica), ma dovette in alcuni casi venire a patti con esso. Particulièrement impitoyable, la guerre à laquelle fut confronté l’État Indépendant Croate entre 1941 et 1945 s’est achevée, en mai 1945, par l’ignoble massacre de Bleiburg (1). Tueries massives de prisonniers civils et militaires, marches de la mort, camps de concentration (2), tortures, pillages, tout est alors mis en œuvre pour écraser la nation croate et la terroriser durablement. La victoire militaire étant acquise (3), les communistes entreprennent, en effet, d’annihiler le nationalisme croate : pour cela, il leur faut supprimer les gens qui pourraient prendre ou reprendre les armes contre eux, mais aussi éliminer les « éléments socialement dangereux », c’est à dire la bourgeoisie et son élite intellectuelle « réactionnaire ». Pour Tito et les siens, rétablir la Yougoslavie et y installer définitivement le marxisme-léninisme implique d’anéantir tous ceux qui pourraient un jour s’opposer à leurs plans (4). L’Épuration répond à cet impératif : au nom du commode alibi antifasciste, elle a clairement pour objectif de décapiter l’adversaire. Le plus souvent d’ailleurs, on ne punit pas des fautes ou des crimes réels mais on invente toutes sortes de pseudo délits pour se débarrasser de qui l’on veut. Ainsi accuse-t-on, une fois sur deux, les Croates de trahison alors que personne n’ayant jamais (démocratiquement) demandé au peuple croate s’il souhaitait appartenir à la Yougoslavie, rien n’obligeait ce dernier à lui être fidèle ! Parallèlement, on châtie sévèrement ceux qui ont loyalement défendu leur terre natale, la Croatie.

Particulièrement impitoyable, la guerre à laquelle fut confronté l’État Indépendant Croate entre 1941 et 1945 s’est achevée, en mai 1945, par l’ignoble massacre de Bleiburg (1). Tueries massives de prisonniers civils et militaires, marches de la mort, camps de concentration (2), tortures, pillages, tout est alors mis en œuvre pour écraser la nation croate et la terroriser durablement. La victoire militaire étant acquise (3), les communistes entreprennent, en effet, d’annihiler le nationalisme croate : pour cela, il leur faut supprimer les gens qui pourraient prendre ou reprendre les armes contre eux, mais aussi éliminer les « éléments socialement dangereux », c’est à dire la bourgeoisie et son élite intellectuelle « réactionnaire ». Pour Tito et les siens, rétablir la Yougoslavie et y installer définitivement le marxisme-léninisme implique d’anéantir tous ceux qui pourraient un jour s’opposer à leurs plans (4). L’Épuration répond à cet impératif : au nom du commode alibi antifasciste, elle a clairement pour objectif de décapiter l’adversaire. Le plus souvent d’ailleurs, on ne punit pas des fautes ou des crimes réels mais on invente toutes sortes de pseudo délits pour se débarrasser de qui l’on veut. Ainsi accuse-t-on, une fois sur deux, les Croates de trahison alors que personne n’ayant jamais (démocratiquement) demandé au peuple croate s’il souhaitait appartenir à la Yougoslavie, rien n’obligeait ce dernier à lui être fidèle ! Parallèlement, on châtie sévèrement ceux qui ont loyalement défendu leur terre natale, la Croatie.