LA NEF n°334 Mars 2021 (version longue et intégrale de l’article paru dans La Nef)

Guerre d’Espagne : un passé qui ne passe pas

par Arnaud Imatz

Longtemps l’Espagne des années 1975-1985 a été considérée comme l’exemple « historique », « unique », presque parfait, de transition pacifique d’un régime autoritaire vers la démocratie libérale. Elle était le modèle unanimement salué, louangé, par la presse internationale occidentale. Depuis, bien de l’eau est passée sous les ponts. La belle image d’Épinal n’a cessé de se détériorer au fil des ans cédant la place aux silences et réserves, puis aux critiques acerbes de nombreux « observateurs » et « spécialistes » politiques. Certains, parmi les plus sévères, n’hésitent plus à réactiver les vieux stéréotypes de l’increvable Légende noire, vieille de cinq siècles, que l’on croyait pourtant définitivement enterrée depuis la fin du franquisme. Mais qu’elle est donc la part de réalité et de fiction dans ce sombre tableau qui nous est désormais décrit?

L’Espagne d’aujourd’hui

L’Espagne apparaît faible, chancelante et impuissante ; elle n’a jamais été autant au bord de l’implosion. Les nationalismes périphériques, les séparatismes, qui la déchirent sont de plus en plus virulents. L’économie du pays souffre de maux graves : manque de compétitivité, détérioration de la productivité, rigidité du marché du travail, taux de chômage le plus élevé de l’UE (en particulier celui des jeunes avec beaucoup de diplômés forcés de s’exiler), coût excessif des sources d’énergie, système financier grevé par l’irrationalité du crédit, déficit public considérable, pléthore de fonctionnaires dans les diverses « autonomies », gaspillage de l’argent public… la liste des problèmes est désespérément longue. Avant la mort du dictateur, Francisco Franco, pendant la première phase du « miracle économique (1959-1975), l’Espagne s’était hissée au 8e rang des puissances économiques mondiales, position qu’elle avait conservée jusqu’à la crise de 2007. Mais elle a par la suite singulièrement décroché pour se retrouver reléguée au 14e rang.

À cela est venu s’ajouter l’effet désastreux de la pandémie de coronavirus et la gestion déplorable de la crise sanitaire. Le président Sánchez et les porte-paroles du palais de la Moncloa ont d’abord prétendu sans vergogne : « le machisme tue plus que le coronavirus », puis, ils ont affirmé triomphalement : « nous avons mis le virus en déroute ». Mais le bourrage de crâne des propagandes politiciennes ne dure qu’un temps. La dure réalité des faits a fini, comme toujours, par s’imposer. On le sait, le bilan provisoire est parmi les plus calamiteux: un effondrement du PIB (-12%), une destruction de plus de 620 000 emplois, près de 4 millions de chômeurs officiels dont un chômage de plus de 40% chez les jeunes, un secteur hôtelier à l’abandon, au bord de la ruine, un recul du tourisme à un niveau plus bas qu’il y a vingt ans, une récession qui est la plus forte du monde occidental après l’Argentine, enfin, une surmortalité liée à la covid 19 s’élèvant à 60 000 voire 110 000 morts (selon les sources).

Le gouvernement Sanchez II.

Cela étant, il convient de préciser tout de suite que la pandémie, événement mondial, grave mais néanmoins conjoncturel, n’a fait qu’aggraver une crise générale préexistante. On ne saurait trop insister sur le rôle d’un facteur structurel, déterminant dans l’involution récente du pays : la défaillance de la classe ou de l’oligarchie politique (droites et gauches de pouvoir confondues) qui n’a jamais été aussi médiocre, corrompue et irresponsable. Le second gouvernement de Pedro Sánchez (2020-), coalition du parti socialiste (PSOE), du Parti communiste (PCE/IU) et de Podemos (un parti « populiste » d’extrême gauche, pro-immigrationniste, dont les leaders se réclament à la fois de Lénine, de Marx et du régime vénézuélien, ce dernier les ayant financés lorsqu’ils étaient dans l’opposition), n’est jamais que l’expression voire l’aboutissement d’un processus de détérioration, de dégénérescence, de vassalisation et de perte presque totale de souveraineté, qui s’est accéléré après le tournant du siècle.

Bien sûr, le cas espagnol ne saurait être expliqué sans une remise en perspective globale. Toutes les démocraties occidentales sont aujourd’hui exposées aux dangers redoutables que sont la révolution culturelle, le politiquement correct, la nouvelle religion séculière postchrétienne et l’émergence du «totalitarisme light ». Mais pour ne pas excéder notre propos, tenons-nous en ici au rôle et à la part de responsabilité de la classe politique espagnole. On ne saurait vraiment saisir la nature et l’ampleur de cette responsabilité dans le collapsus général, politique, social, économique et moral (mais aussi dans le suicide démographique ; le taux de fécondité étant le plus bas de l’UE : 1,17, voire 1,23 en incluant l’indice de natalité des immigrés), sans évoquer quelques événements clefs de la transition démocratique et du tournant du siècle. Ce rappel permettra de mieux comprendre pourquoi tout ce qui touche à la guerre civile de 1936-1939 est devenu un sujet de division beaucoup plus violent aujourd’hui qu’il y a encore quinze ans, alors que le temps aurait dû contribuer à apaiser les passions.

De l’esprit de la transition démocratique au retour de la mentalité de guerre civile

Un point d’histoire est indiscutable: c’est la droite franquiste (mélange complexe et subtil de carlistes-traditionalistes, monarchistes conservateurs et libéraux, phalangistes, conservateurs-républicains, démocrates-chrétiens, radicaux de droite et technocrates) qui a pris l’initiative d’instaurer la démocratie. Cette transition démocratique n’a pas été une conquête des ennemis de la dictature, elle a été un choix délibéré de la grande majorité de ceux qui avaient été jusque là ses principaux leaders. L’intelligence politique de la gauche (le PSOE de Felipe González et le PCE de Santiago Carrillo), a été de renoncer à ses revendications maximalistes, pour embrasser la voie du réformisme et joindre ainsi ses forces au processus démocratique amorcé par la droite franquiste. Les faits parlent d’eux même : Le décret-loi autorisant les associations politiques fut édicté par Franco en 1974, un an avant sa mort. La loi de réforme politique fut adoptée par les anciennes Cortes « franquistes » le 18 novembre 1976 et ratifiée par référendum populaire le 15 décembre 1976. La loi d’amnistie fut adoptée par les nouvelles Cortes « démocratiques » le 15 octobre 1977. Elle reçut l’appui de la quasi totalité de la classe politique (en particulier celle des leaders du PSOE et du PCE). N’oublions pas la présence dans les Cortes de la première législature de personnalités exilées d’extrême gauche aussi significatives que Santiago Carrillo, Dolores Ibarruri (la Pasionaria) ou Rafael Alberti. Enfin, c’est le Congrès (l’organe constitutionnel) qui a adopté la Constitution actuelle, qui a été ensuite ratifiée par référendum le 6 décembre 1978 (avec 87% de voix pour).

La Transition démocratique reposait sur une parfaite conscience des échecs du passé et sur la volonté de les dépasser. Il ne s’agissait pas d’oublier et encore moins d’imposer le silence aux historiens ou aux journalistes, mais de les laisser débattre et de refuser que les politiciens s’emparent du sujet pour leurs luttes partisanes. Deux principes animaient cet « esprit de la transition démocratique », aujourd’hui dénoncé, tergiversé et caricaturé par les gauches, le pardon réciproque et la concertation entre gouvernement et opposition. Il était alors inconcevable que des politiciens de droite ou de gauche s’insultent en se traitant de « rouge » ou de « fasciste ».

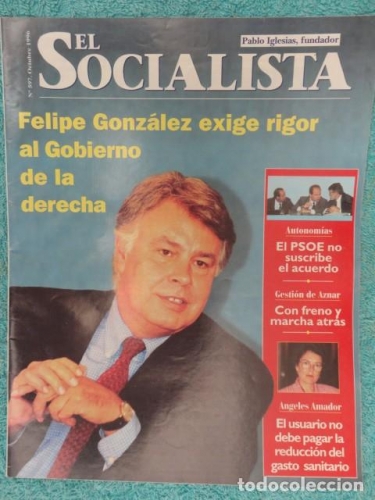

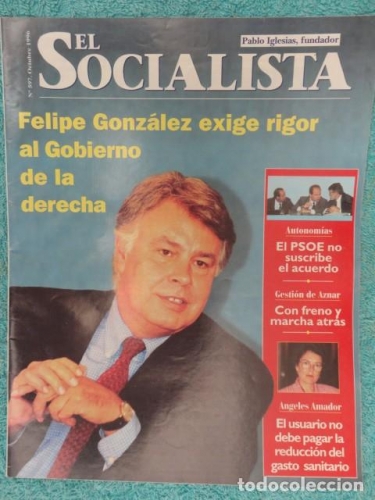

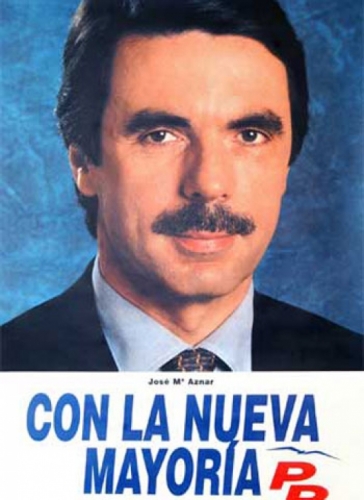

Un premier durcissement dans les polémiques partisanes devait néanmoins se produire lors des législatives de 1993. Mais la vraie rupture se situe trois ans plus tard, en 1996, lorsque le PSOE avec son leader Felipe González (au pouvoir depuis 14 ans mais en difficulté dans les sondages), a volontairement joué la carte de la peur, dénonçant le Parti Populaire (PP), parti néolibéral et conservateur, comme un parti agressif, réactionnaire, menaçant, héritier direct du franquisme et du fascisme. Les Espagnols se souviennent encore d’une fameuse vidéo électorale du PSOE qui représentait le PP en doberman ou pitbull enragé et sanguinaire.

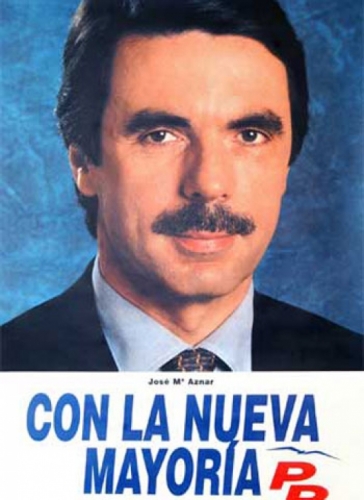

Pendant toute la décennie 1990, un véritable raz de marée culturel, néo-socialiste et postmarxiste, a submergé le pays. Les nombreux auteurs autoproclamés « progressistes », tous défenseurs du Front populaire de 1936, ont inondé les librairies de livres, occupé les chaires universitaires, monopolisé les grands médias et gagné largement la bataille historiographique. La nation, la famille et la religion sont redevenues des cibles privilégiées de la propagande semi-officielle. Paradoxalement, cette situation s’est maintenue sous les gouvernements de droite de José Maria Aznar (1996-2004). Obsédé par l’économie, « L’Espagne va bien ! », Aznar s’est désintéressé des questions culturelles ; mieux, il a cherché à donner des gages idéologiques à la gauche. A vrai dire, beaucoup de gens de droite lui donnaient raison lorsqu’il rendait hommage aux Brigades internationales (pourtant composées à 90% de communistes et socialistes marxistes), ou lorsqu’il condamnait le franquisme, voire le soulèvement du 18 juillet 1936 (alors qu’il est le fils d’un phalangiste et qu’il a été lui-même dans sa jeunesse un admirateur déclaré de José Antonio, un militant de la Phalange indépendante et dissidente). La droite « la plus bête du monde » (comme on aime à dire en France), acquiesçait aussi lorsqu’il encensait le ministre et président du Front populaire, Manuel Azaña, un franc-maçon, farouchement anticatholique, l’un des trois principaux responsables du désastre final de la République et du déclenchement de la guerre civile, avec le républicain catholique Niceto Alcalá-Zamora et le socialiste Francisco Largo Caballero, le « Lénine espagnol ». Les leaders du PP, régulièrement et injustement accusés d’être les héritiers du franquisme et du fascisme, croyaient pouvoir désarmer l’adversaire et trouver leur salut dans une continuelle profession de foi antifranquiste. Une erreur crasse, qu’ils finiront par payer vingt ans plus tard, lorsqu’en 2019 le parti populiste Vox surgira sur la scène politique.

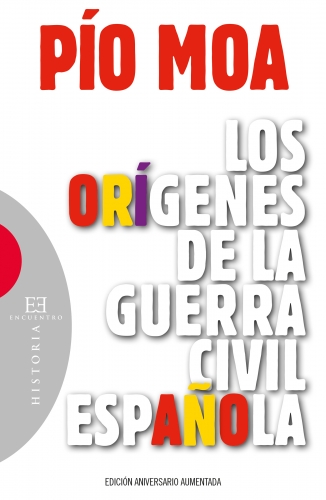

Mais dans les années 2000, l’imprévisible allait se produire en dehors de la droite politique. Au nom de la liberté d’expression, d’opinion, de débat et de recherche, un groupe d’historiens indépendants, avec à leur tête l’américain Stanley Payne (voir notamment La guerre d’Espagne. L’histoire face à la confusion mémorielle, un livre incompréhensiblement épuisé et non réédité en France depuis des années) et l’ex-communiste Pio Moa (auteur de best-sellers tels Los mitos de la guerra civil, un livre vendu à plus de 300 000 exemplaires, encore inédit en France, qui démontre notamment que le soulèvement socialiste de 1934 a été l’antécédent direct du soulèvement national du 18 juillet), mais aussi toute une pléiade d’universitaires, dont un bon nombre de professeurs d’histoire de l’université CEU San Pablo de Madrid, se sont insurgés contre le monopole culturel de la gauche socialo-marxiste. Quelques années plus tard, d’autres travaux incontournables ont été publiés tels ceux de Roberto Villa García et Manuel Álvarez, sur les fraudes et les violences du Front Populaire lors des élections de février 1936, de César Álcala sur les plus de 400 « Checas » (centres de tortures organisés par les différents partis du Front populaire dans les grandes villes pendant la guerre civile), ou les recherches de Miguel Platon sur le nombre des exécutions et assassinats dans les deux camps (57 000 victimes parmi les nationaux / nacionales et non pas nacionalistas/nationalistes, comme on le dit à tort en France, et 62 000 victimes parmi les front-populistes ou républicains) et sur le nombre des victimes de la répression franquiste de l’après-guerre (22 000 condamnations à mort dont la moitié commuées en peines de prison). Citons également ici l’œuvre de référence, bien que beaucoup plus ancienne, d’Antonio Montero, sur la terrible persécution religieuse (près de 7000 religieux assassinés de 1936 à 1939 ; 1916 martyrs de la foi ayant été béatifiés et 11 canonisés par les papes entre 1987 et 2020, en dépit des pressions des autorités espagnoles).

Au lendemain de son accession au pouvoir, en 2004, plutôt que de contribuer à effacer les rancœurs, le socialiste José Luis Rodriguez Zapatero, ami déclaré des dictateurs Fidel Castro et Nicolas Maduro, a ravivé considérablement la bataille idéologique et culturelle. Rompant avec le modérantisme du socialiste Felipe González, il a choisi délibérément de rouvrir les blessures du passé et de fomenter l’agitation sociale. En 2006, avec l’aide du député travailliste maltais, Léo Brincat, il a fait adopter par la commission permanente, agissant au nom de l’assemblée du Conseil de l’Europe, une recommandation sur « la nécessité de condamner le franquisme au niveau international ». Dès la fin de la même année, diverses associations « pour la récupération de la mémoire », ont déposé des plaintes auprès du Juge d’instruction de l’Audience nationale, Baltasar Garzón. Elles prétendaient dénoncer un «plan systématique » franquiste « d’élimination physique de l’adversaire » « méritant le qualificatif juridique de génocide et de crime contre l’humanité». Garzón, juge à la sensibilité socialiste, s’est déclaré immédiatement compétent mais il a été désavoué par ses pairs et finalement condamné à dix ans d’ « inhabilitation » professionnelle pour prévarication par le Tribunal suprême.

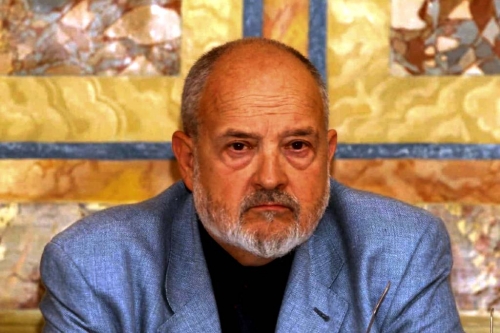

Baltasar Garzon.

La loi de mémoire historique de 2007

Un an plus tard, en 2007, se voyant dans l’impossibilité de faire taire les nombreuses voix discordantes d’historiens et de journalistes, Zapatero et ses alliés ont choisi, sur l’initiative des communistes d’Izquierda Unida, de recourir à la loi « mémorielle ». La « loi de mémoire historique », adoptée le 26 décembre 2007, se veut et se justifie comme une « défense de la démocratie », contre un possible retour du franquisme et des « idéologies de haine ». En réalité, elle est une loi discriminante et sectaire en rien démocratique. Elle reconnaît et amplifie justement les droits en faveur de ceux qui ont pâti des persécutions ou de la violence pendant la guerre civile et la dictature (des normes en ce sens ayant déjà été édictées par des lois de 1977, 1980, 1982 et 1984), mais dans le même temps, elle accrédite une vision manichéenne de l’histoire contrevenant à l’éthique la plus élémentaire.

L’idée fondamentale de cette loi est que la démocratie espagnole est l’héritage de la Seconde République (1931-1936) et du Front populaire (1936-1939). Selon son raisonnement, la Seconde République (avec le Front populaire), mythe fondateur de la démocratie espagnole, a été un régime presque parfait dans lequel l’ensemble des partis de gauche a eu une action irréprochable. La droite serait en définitive la seule responsable de la destruction de la démocratie et de la guerre civile. Pour couronner le tout, mettre en cause ce mensonge historique ne saurait être qu’une apologie exprès ou déguisée du fascisme.

Cette loi effectue un amalgame absurde entre le soulèvement militaire, la guerre civile et le régime de Franco, qui sont autant de faits bien distincts relevant d’interprétations et de jugements différents. Elle exalte les victimes et les assassins, les innocents et les coupables lorsqu’ils sont dans le camp du Front populaire et uniquement parce qu’ils sont de gauche. Elle confond les morts en action de guerre et les victimes de la répression. Elle jette le voile de l’oubli sur les victimes « républicaines » qui sont mortes aux mains de leurs frères ennemis de gauche. Elle encourage tout travail visant à démontrer que Franco a mené délibérément et systématiquement une répression sanglante pendant et après la guerre civile. Enfin, elle reconnait le légitime désir de beaucoup de personnes de pouvoir localiser le corps de leur ancêtre, mais refuse implicitement ce droit à ceux qui étaient dans le camp national sous prétexte qu’ils auraient eu le temps de le faire à l’époque du franquisme.

Théoriquement, cette loi a pour objet d’honorer et de récupérer la mémoire de tous ceux qui furent victimes d’injustices pour des motifs politiques ou idéologiques pendant et après la guerre civile, mais en réalité, non sans perversité, elle refuse de reconnaître que sous la République et pendant la guerre civile beaucoup de crimes ont été commis au nom du socialisme-marxiste, du communisme et de l’anarchisme et que ces monstruosités peuvent être qualifiées elles aussi de crimes de lèse humanité (il en est ainsi, notamment, des massacres de Paracuellos del Jarama et des « Checas », et des hécatombes lors de la persécution des chrétiens). Dès sa promulgation, la « loi de mémoire historique » a d’ailleurs été systématiquement interprétée en faveur des représentants et sympathisants du seul camp républicain ou front-populiste et de leurs seuls descendants.

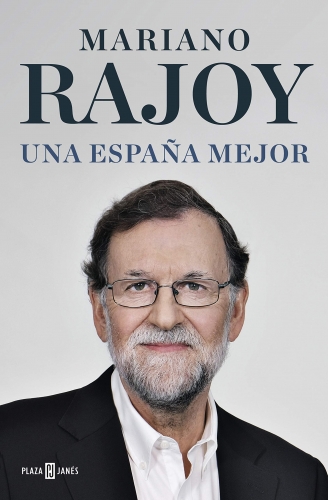

Le retour au pouvoir de la droite, trois ans après le début de la crise économico-financière de 2008, ne devait guère changer la donne. Le président Mariano Rajoy (2011-2018), ancien conservateur des hypothèques devenu un politicien professionnel roué mais dépourvu de tout charisme, s’est contenté de suivre le précepte bien connu des néolibéraux: ne pas toucher aux réformes culturelles ou sociétales « progressistes » mais défendre d’abord et avant tout les intérêts et les idées économiques et financières des eurocrates et de l’oligarchie mondialiste. Rajoy n’osera ni abroger, ni modifier la loi de mémoire. Un ami, philosophe Argentin à l’humour cinglant, résumait son idéologie par ces mots : « L’important c’est l’économie… et que mon fils parle l’anglais ». Mais encore faut il ajouter que cette attitude à courte vue a été largement partagée par son électorat. Historiquement, les droites espagnoles ont toujours été marquées par la forte empreinte du catholicisme, mais dans une société sécularisée, dans laquelle la hiérarchie de l’Église ne résiste pas mais donne au contraire au quotidien l’exemple du renoncement, de l’abdication et de la soumission, l’électorat de droite se retrouve inévitablement passif, apathique, désemparé, sans protection. Bon gestionnaire en période de calme, mais dépourvu des qualités de l’homme d’État, Rajoy s’est avéré incapable d’affirmer son autorité en pleine tourmente. Ébranlé politiquement par le référendum d’indépendance de la Catalogne (2017), organisé par les séparatistes sans la moindre garantie juridique, il a chuté finalement à l’occasion d’une motion de censure (2018) suite à l’implication du PP dans divers scandales de corruption.

Vers la nouvelle « loi de mémoire démocratique » de 2021

Avec l’adoption de la « loi de mémoire historique », la boîte de Pandore a été ouverte. Élu à la présidence, en juin 2018, le socialiste Pedro Sánchez, n’a pas tardé à en faire la démonstration. Pour rester au pouvoir, Sánchez, qui représente la tendance radicale du PSOE opposée aux modérés, a accepté les voix de l’extrême gauche et des indépendantistes alors qu’il avait juré avant les élections ne jamais le faire. Arriviste, allié par opportunisme à Podemos et au PC/IU, il doit donner régulièrement des gages à ses associés les plus radicaux (y compris aux nationalistes-indépendantistes) tout en ménageant Bruxelles et Washington, qui ne manqueraient pas de siffler la fin de la récréation si la ligne rouge venait à être franchie en matière économique.

Le premier gouvernement socialiste de Sánchez s’est engagé, dès le 15 février 2019, à procéder au plus vite à l’exhumation de la dépouille du dictateur Francisco Franco enterré quarante-trois ans plus tôt dans le chœur de la basilique du Valle de los Caídos. Le 15 septembre 2020, moins d’un an après avoir réalisé le transfert des cendres, malgré le chaos de la pandémie et le caractère prioritaire de la gestion sanitaire, le second gouvernement de Sánchez, une coalition de socialistes, de communistes et de populistes d’extrême gauche (PSOE-PC/IU-Podemos), a décidé d’adopter, au plus tôt, un nouvel « Avant-projet de loi de mémoire démocratique », qui devrait abroger la « loi de mémoire historique » de 2007. Au nom de la « justice historique » et du combat contre « la haine », contre « le franquisme » et « le fascisme », le gouvernement entend promouvoir la réparation morale des victimes de la guerre civile et du franquisme et « garantir aux citoyens la connaissance de l’histoire démocratique ».

Cet avant-projet de loi prévoit plus précisément : la création d’un parquet spécial du Tribunal suprême compétent en matière de réparation des victimes ; l’allocation de fonds publics pour l’exhumation des victimes des franquistes enterrées dans des fosses communes et leur identification a partir d’une banque nationale ADN ; l’interdiction de la Fondation Francisco Franco et de toutes les « institutions qui incitent à la haine » ; l’annulation des jugements prononcés par les tribunaux franquistes ; l’inventaire des biens spoliés et des sanctions économiques pour ceux qui les ont confisqués ; l’indemnisation des victimes de travaux forcés par les entreprises qui ont bénéficié de leur main d’œuvre ; la révocation et l’annulation de toutes les distinctions, décorations et titres nobiliaires concédés jusqu’en 1978 ; l’effacement et le retrait de tous les noms de rue ou d’édifices publics rappelant symboliquement le franquisme ; l’actualisation des programmes scolaires pour tenir compte de la vraie mémoire démocratique et pour expliquer aux élèves « d’où nous venons » afin que « nous ne perdions jamais plus nos libertés » ; l’expulsion des moines bénédictins gardiens du Valle de los Caidos ; l’exhumation et le déplacement des restes mortels de José Antonio Primo de Rivera ; la désacralisation et la « resignification » de la basilique du Valle de los Caídos qui sera reconvertie en cimetière civil et musée de la guerre civile ; enfin, aux dire de la vice-présidente, Carmen Calvo, il sera menée une « réflexion » sur l’éventualité de la destruction de l’immense croix surmontant le temple. Pour couronner le tout, des amendes de 200 euros à 150 000 euros sont prévues afin de réprimer toutes les infractions à la loi.

Carmen Calvo.

Dans un langage typiquement orwellien, la première vice-présidente Carmen Calvo n’a pas manqué de souligner que ce texte favorisera la « coexistence » et permettra aux Espagnols de « se retrouver dans la vérité ». La réalité est pourtant tragique : cet avant-projet renouvelle et renforce l’utilisation de la guerre civile comme arme politique. Il discrimine et stigmatise la moitié des espagnols, efface les victimes de la répression front-populiste, refuse l’annulation même symbolique des sentences prononcées par les tribunaux populaires républicains et ignore superbement la responsabilité de la gauche dans certaines des atrocités les plus horribles commises pendant la guerre civile. Seule la vision « progressiste » du passé définie par les autorités en place est démocratique, l’histoire des « autres » devant disparaître comme dans le cas de l’histoire manipulée de l’Union soviétique.

On ne saurait pourtant « se retrouver dans la vérité », comme le dit Calvo, en écartant d’un trait de plume toute recherche historique rigoureuse. Contrairement à ce que prétend la vice-présidente, le soulèvement militaire de juillet 1936 n’est pas à l’origine de la destruction de la démocratie. C’est au contraire parce que la légalité démocratique a été détruite par le Front populaire que le soulèvement s’est produit. En 1936, personne ne croyait en la démocratie libérale et certainement pas les gauches. Le mythe révolutionnaire partagé par toutes les gauches était celui de la lutte armée. Ni les anarchistes (qui s’étaient révoltés en 1931, 1932 et 1933), ni le parti communiste, un parti stalinien, ne croyaient en la démocratie. La majorité des socialistes avec leur leader le plus significatif, Largo Caballero, le « Lénine espagnol », préconisait la dictature du prolétariat et le rapprochement avec les communistes. Le PSOE était le principal responsable du putsch d’octobre 1934 contre le gouvernement de la République, du radical Alejandro Lerroux.

Un seul exemple suffit pour illustrer le caractère révolutionnaire du courant alors majoritaire au sein du PSOE. Le 17 février 1934, la revue Renovación, publiait un « décalogue » des Jeunesses socialistes (mouvement dirigé par le secrétaire général Santiago Carrillo, qui devait fusionner avec les Jeunesses communistes, en mars 1936). Dans son point 8, on pouvait lire : « La seule idée que doit avoir aujourd’hui gravée dans la tête le jeune socialiste est que le Socialisme ne peut s’imposer que par la violence, qu’un camarade qui propose le contraire, qui a encore des rêves démocratiques, qu’il soit petit ou grand, ne saurait être qu’un traître, consciemment ou inconsciemment ». On ne saurait être plus clair ! Quant aux gauches républicaines du jacobin Manuel Azaña, elles s’étaient compromises dans le soulèvement socialiste de 1934, et ne pouvaient donc pas davantage être tenues pour démocrates. Ajoutons encore que, dès son arrivée au pouvoir en février 1936, le Front populaire ne cessera d’attaquer la légalité démocratique. Le Front populaire espagnol était extrémiste et révolutionnaire. Le Front populaire français était, en comparaison, modéré et réformiste. Telle est la triste réalité que le gouvernement socialiste espagnol cherche aujourd’hui vainement à cacher derrière un épais rideau de fumée.

L’avant-projet de loi de « mémoire démocratique » de la coalition socialo-communiste n’est pas seulement antidémocratique ou autoritaire, il est proprement totalitaire. En poursuivant la « rééducation » pour ce qui concerne le passé, il porte gravement atteinte à la liberté d’expression et d’enseignement. Il est anticonstitutionnel, mais de cela bien évidemment ses rédacteurs se soucient comme d’une guigne dans la mesure où à plus long terme ils souhaitent imposer une autre constitution plus « révolutionnaire » et, par la même occasion, se débarrasser de la monarchie.

Outre ce texte de loi de mémoire démocratique, le gouvernement espagnol de Pedro Sánchez a l’intention de soumettre prochainement au parlement tout un ensemble de projets de lois (sur l’euthanasie, l’interruption de grossesses, l’éducation, le choix en matière de genre, etc.), qui heurte de front les conceptions chrétiennes de la vie. Les autorités espagnoles ne recherchent plus la paix qu’à travers la division, l’agitation, la provocation, le ressentiment et la haine; la justice prend la forme de la rancœur et de la vengeance. L’Espagne semble s’enfoncer inexorablement dans une crise globale d’une ampleur dramatique.

Arnaud Imatz

https://lanef.net/2021/03/12/guerre-despagne-un-passe-qui...

Le lieutenant général Michael Groen, directeur du Joint Artificial Intelligence Center du ministère américain de la défense, évoque la nécessité d'accélérer la mise en œuvre de programmes d'intelligence artificielle à usage militaire. Selon lui, "nous pourrions bientôt nous retrouver dans un espace de combat défini par la prise de décision basée sur les données, l'action intégrée et le rythme. En déployant les efforts nécessaires pour mettre en œuvre l'IA aujourd'hui, nous nous retrouverons à l'avenir à opérer avec une efficacité et une efficience sans précédent".

Le lieutenant général Michael Groen, directeur du Joint Artificial Intelligence Center du ministère américain de la défense, évoque la nécessité d'accélérer la mise en œuvre de programmes d'intelligence artificielle à usage militaire. Selon lui, "nous pourrions bientôt nous retrouver dans un espace de combat défini par la prise de décision basée sur les données, l'action intégrée et le rythme. En déployant les efforts nécessaires pour mettre en œuvre l'IA aujourd'hui, nous nous retrouverons à l'avenir à opérer avec une efficacité et une efficience sans précédent".

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Quant aux mouvements "populistes" actuels, leur parabole a déjà été parcourue au cours des vingt dernières années par la "Lega" et est en train d'être parcourue par le "M5S" : succès initial soudain, dû à la nouveauté, insistance sur quelques thèmes de propagande facilement déclinés avec quelques variables (anti-islamisme, xénophobie, anti-européanisme, "anti-politique", moralisme, etc.), lassitude vis-à-vis de la politique politicienne démocratique habituelle, due à la routine d’une politique professionnelle et incompétente, puis impasse et crise dues à une détérioration rapide – à un vieillissement. L'absence de véritables programmes et surtout d'une authentique tension civique conduit fatalement à un échec cyclique mais peut-être aussi à une résurrection rapide sur des modules récurrents (le berlusconisme et le recyclage des thèmes et sympathies de l'ex-Ligue dans le grillisme en sont la preuve).

Quant aux mouvements "populistes" actuels, leur parabole a déjà été parcourue au cours des vingt dernières années par la "Lega" et est en train d'être parcourue par le "M5S" : succès initial soudain, dû à la nouveauté, insistance sur quelques thèmes de propagande facilement déclinés avec quelques variables (anti-islamisme, xénophobie, anti-européanisme, "anti-politique", moralisme, etc.), lassitude vis-à-vis de la politique politicienne démocratique habituelle, due à la routine d’une politique professionnelle et incompétente, puis impasse et crise dues à une détérioration rapide – à un vieillissement. L'absence de véritables programmes et surtout d'une authentique tension civique conduit fatalement à un échec cyclique mais peut-être aussi à une résurrection rapide sur des modules récurrents (le berlusconisme et le recyclage des thèmes et sympathies de l'ex-Ligue dans le grillisme en sont la preuve). Le populisme peut-il être lu comme la énième désintégration d'une pensée européenne construite sur des cathédrales, des monastères et des universités ?

Le populisme peut-il être lu comme la énième désintégration d'une pensée européenne construite sur des cathédrales, des monastères et des universités ?

Le lien nécessaire entre la terre et la population

Le lien nécessaire entre la terre et la population

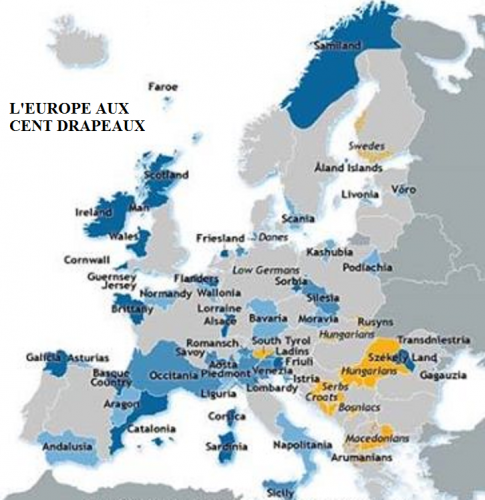

Et cette diversité représente les cent drapeaux d’une Europe non pas éclatée, mais unie dans l’esprit de sa diversité. L’exemple corse montre aux peuples de France l’exemple au moins institutionnel à suivre. Savez-vous que Jean Mabire a été obligé d’arrêter de donner des libres propos dans National Hebdo, l’ancien journal du Front national (FN) parce qu’il y avait affirmé l’existence du peuple corse, en 1991 ? La difficile affirmation d’une identité française surannée laisse, de facto, liberté aux peuples de France à la libre expression. Les seules minorités ethniques reconnues constitutionnellement sont des communautés ultra-marine, or la terre d’Europe, dont la terre française fait partie, est fertile en peuples, en nations non-étatiques.

Et cette diversité représente les cent drapeaux d’une Europe non pas éclatée, mais unie dans l’esprit de sa diversité. L’exemple corse montre aux peuples de France l’exemple au moins institutionnel à suivre. Savez-vous que Jean Mabire a été obligé d’arrêter de donner des libres propos dans National Hebdo, l’ancien journal du Front national (FN) parce qu’il y avait affirmé l’existence du peuple corse, en 1991 ? La difficile affirmation d’une identité française surannée laisse, de facto, liberté aux peuples de France à la libre expression. Les seules minorités ethniques reconnues constitutionnellement sont des communautés ultra-marine, or la terre d’Europe, dont la terre française fait partie, est fertile en peuples, en nations non-étatiques.

La réponse du gouvernement australien ne s'est pas fait attendre. Le Premier ministre australien Scott Morrison s'en est pris au célèbre réseau social: "Les actions de Facebook, qui a retiré l'Australie de sa liste d'amis aujourd'hui, perturbant ainsi des services d'information essentiels sur la santé et les services d'urgence, étaient aussi arrogantes que décevantes". De plus, M. Morrison poursuit: "Ces actions ne feront que confirmer les inquiétudes qu'un nombre croissant de pays expriment quant au comportement des grandes entreprises technologiques qui pensent être plus importantes que les gouvernements et que les règles ne devraient pas s'appliquer à elles. Ils peuvent changer le monde, mais ça ne veut pas dire qu'ils le dirigent".

La réponse du gouvernement australien ne s'est pas fait attendre. Le Premier ministre australien Scott Morrison s'en est pris au célèbre réseau social: "Les actions de Facebook, qui a retiré l'Australie de sa liste d'amis aujourd'hui, perturbant ainsi des services d'information essentiels sur la santé et les services d'urgence, étaient aussi arrogantes que décevantes". De plus, M. Morrison poursuit: "Ces actions ne feront que confirmer les inquiétudes qu'un nombre croissant de pays expriment quant au comportement des grandes entreprises technologiques qui pensent être plus importantes que les gouvernements et que les règles ne devraient pas s'appliquer à elles. Ils peuvent changer le monde, mais ça ne veut pas dire qu'ils le dirigent".

Destinée à favoriser les liens entre la France et les Etats Unis, la French American Fondation est née en 1976, durant ds heures d’antagonisme entre les deux nations. Elle a été baptisée lors d’un dîner aux Etats Unis entre le président Gerald Ford et Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. L’activité de cette fondation est centrée sur le programme Young Leaders dont la mission est de trouver les personnes qui feront l’opinion et qui seront les dirigeants de leurs sociétés respectives. Ils sont né en 1981, avec pour parrain l’influent économiste libéral franco-américain de Princeton, Ezra Suleiman. Le programme financé par des mécènes privés, s’étale sur deux ans, avec un séjour de quatre jours en France, un autre temps équivalent aux Etats Unis, toujours dans des villes différentes, toujours avec des intervenants de très haut niveau. Les Young Leaders français sont (liste non exhaustive): Juppé, Pécresse, Kosciusko Morizet, Wauquiez, Bougrab, Hollande, Moscovici, Montebourg, Marisol Touraine, Najat Vallaut – Belkacem, Aquilino Morelle, Bruno Leroux, Olivier Ferrand, Laurent Joffrin (Nouvel Observateur), Denis Olivennes (Europe 1, Paris Match et du JDD), Matthieu Pigasse, Louis Dreyfus et Erik Izraelewicz (Le Monde).

Destinée à favoriser les liens entre la France et les Etats Unis, la French American Fondation est née en 1976, durant ds heures d’antagonisme entre les deux nations. Elle a été baptisée lors d’un dîner aux Etats Unis entre le président Gerald Ford et Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. L’activité de cette fondation est centrée sur le programme Young Leaders dont la mission est de trouver les personnes qui feront l’opinion et qui seront les dirigeants de leurs sociétés respectives. Ils sont né en 1981, avec pour parrain l’influent économiste libéral franco-américain de Princeton, Ezra Suleiman. Le programme financé par des mécènes privés, s’étale sur deux ans, avec un séjour de quatre jours en France, un autre temps équivalent aux Etats Unis, toujours dans des villes différentes, toujours avec des intervenants de très haut niveau. Les Young Leaders français sont (liste non exhaustive): Juppé, Pécresse, Kosciusko Morizet, Wauquiez, Bougrab, Hollande, Moscovici, Montebourg, Marisol Touraine, Najat Vallaut – Belkacem, Aquilino Morelle, Bruno Leroux, Olivier Ferrand, Laurent Joffrin (Nouvel Observateur), Denis Olivennes (Europe 1, Paris Match et du JDD), Matthieu Pigasse, Louis Dreyfus et Erik Izraelewicz (Le Monde).

Pourquoi un tel recours au sot savant de Molière ? C’est le nombre de chaînes de télé qui devient prodigieux, confirmant que l’humanité ne fait plus rien : on regarde 6.000 chaînes de télé et on a besoin d’experts sur tous les sujets pour savoir quoi penser en matière de vaccins, de nourriture, de sexe, d’atomisme nord-coréen ou de gamins transgenre.

Pourquoi un tel recours au sot savant de Molière ? C’est le nombre de chaînes de télé qui devient prodigieux, confirmant que l’humanité ne fait plus rien : on regarde 6.000 chaînes de télé et on a besoin d’experts sur tous les sujets pour savoir quoi penser en matière de vaccins, de nourriture, de sexe, d’atomisme nord-coréen ou de gamins transgenre. Le film continue sur sa lancée : l’art moderne avec ses copies indécelables et ses toiles blanches ; la météo avec son réchauffement climatique ; la bourse, bien sûr, avec la fameuse parabole du singe qui ne se trompe pas plus qu’un analyste payé des fortunes.

Le film continue sur sa lancée : l’art moderne avec ses copies indécelables et ses toiles blanches ; la météo avec son réchauffement climatique ; la bourse, bien sûr, avec la fameuse parabole du singe qui ne se trompe pas plus qu’un analyste payé des fortunes.

En situant cette fiction sur les dernières pentes du Mont Blanc (qui risque bientôt d’être renommé « Mont Arc-en-Ciel »), Saint Loup sait que le nom « Alpes » provient d’une antique racine celtique proche du mot d’origine indo-européenne « albos » qu’on peut traduire aussi bien par « monde blanc », « monde lumineux » et « monde d’en-haut ».

En situant cette fiction sur les dernières pentes du Mont Blanc (qui risque bientôt d’être renommé « Mont Arc-en-Ciel »), Saint Loup sait que le nom « Alpes » provient d’une antique racine celtique proche du mot d’origine indo-européenne « albos » qu’on peut traduire aussi bien par « monde blanc », « monde lumineux » et « monde d’en-haut ». Le complexe orographique qui associe les Alpes, les Montagnes dinariques, les Balkans et les Carpates sert en outre de conservatoire ethnique et confessionnel. Les vaudois, les adeptes d’une hérésie médiévale du Lyonnais Pierre Valdo (1140 – 1217) qui annonce la Réforme protestante, s’implantent par exemple dans la vallée alpine de l’Ubaye. On s’exprime toujours en romanche dans le canton suisse des Grisons. Dans le Val d’Aoste de langue française perdure le peuple walser et dans le Trentin – Haut-Adige – Tyrol du Sud germanophone vivent les Ladins. Aux confins des Carpates demeurent encore les Sicules de langue magyare et les Saxons (les lointains enfants des colons allemands du Moyen Âge). Dans les Alpes dinariques et dans les Balkans se rencontrent enfin les Pomaks musulmans, les Valaques (ou Aroumains) ou les Goranci eux-aussi mahométans.

Le complexe orographique qui associe les Alpes, les Montagnes dinariques, les Balkans et les Carpates sert en outre de conservatoire ethnique et confessionnel. Les vaudois, les adeptes d’une hérésie médiévale du Lyonnais Pierre Valdo (1140 – 1217) qui annonce la Réforme protestante, s’implantent par exemple dans la vallée alpine de l’Ubaye. On s’exprime toujours en romanche dans le canton suisse des Grisons. Dans le Val d’Aoste de langue française perdure le peuple walser et dans le Trentin – Haut-Adige – Tyrol du Sud germanophone vivent les Ladins. Aux confins des Carpates demeurent encore les Sicules de langue magyare et les Saxons (les lointains enfants des colons allemands du Moyen Âge). Dans les Alpes dinariques et dans les Balkans se rencontrent enfin les Pomaks musulmans, les Valaques (ou Aroumains) ou les Goranci eux-aussi mahométans.

Un livre d’expert nous prévenait (dans un langage scientifique) il y a une dizaine d’années ou plus : les mondialistes nous conditionnaient par la peur des pandémies depuis le début des années 2000 (langage complotiste), en particulier dans le bon vieux monde transatlantique. Tout cela avait suivi le 11 septembre qui devait nous préparer au bioterrorisme, au cyber-terrorisme et enfin à leur vieil objectif de dépeuplement (conspiration ou constatation ?). L’expert en question s’appelle Patrick Zylberman et s’est alors fait l’auteur de drôles de constatations. Le livre a évidemment été mal reçu alors, les journalistes étant comme les médecins vendus achetés pour vendre terreur, vaccin et dictature technologique.

Un livre d’expert nous prévenait (dans un langage scientifique) il y a une dizaine d’années ou plus : les mondialistes nous conditionnaient par la peur des pandémies depuis le début des années 2000 (langage complotiste), en particulier dans le bon vieux monde transatlantique. Tout cela avait suivi le 11 septembre qui devait nous préparer au bioterrorisme, au cyber-terrorisme et enfin à leur vieil objectif de dépeuplement (conspiration ou constatation ?). L’expert en question s’appelle Patrick Zylberman et s’est alors fait l’auteur de drôles de constatations. Le livre a évidemment été mal reçu alors, les journalistes étant comme les médecins vendus achetés pour vendre terreur, vaccin et dictature technologique.  Le storytelling du pire justifie leur tyrannie,

Le storytelling du pire justifie leur tyrannie,