Edelweiss

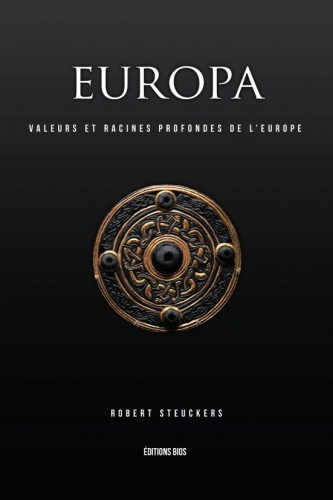

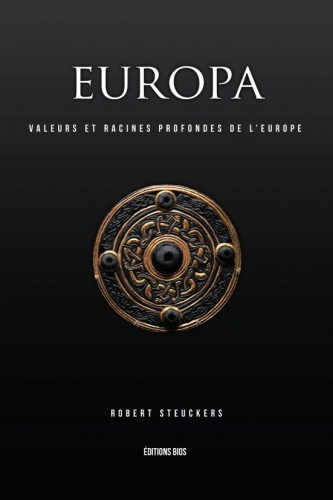

De Archeo-Futuristische Europese Rijksgedachte aan de hand van Robert Steuckers’ Europa I. Valeurs et racines profondes de l’Europe

(Madrid: BIOS, 2017)

door Alexander Wolfheze

Voorwoord: Slangtong in Zürich

De aanstaande Europese verkiezingen, waarmee het globalistisch-eurocratisch regime in Brussels zich nogmaals vier jaar een ‘democratische’ dekmantel wil aanmeten, biedt een goede gelegenheid tot een gedegen heroverweging van het ‘EU project’. De democratische camouflagekleding van het EU keizerrijk is inmiddels echter zodanig afgedragen dat zelfs troonopvolger kandidaat Mark Rutte zich afvraagt of het niet tijd is om het gewoon maar om te kleden in onverhuld totalitaire ‘uniform’ stijl. De titel van zijn op 13 februari 2019 in Zürich uitgesproken - en door analisten als ‘sollicitatiebrief’ nummer zoveel geïnterpreteerde[1] - ‘Churchill Lezing’ spreekt in dit opzicht boekdelen: The EU: from the power of principles towards principles and power.[2] Ofwel: ‘De EU: van de macht van principes naar principes en macht’. ‘Naar machtsprincipe’ zegt hij nog net niet, maar de inhoud windt er geen doekjes om: ‘het gaat in de wereld om macht en macht is geen vies woord’ (lees: de EU heeft machtsmiddelen die onvoldoende worden gebruikt), ‘de EU moet minder naïef zijn en meer realisme tonen’ (lees: het is tijd voor de EU het idealistisch masker laat vallen) en ‘we moeten besluiten over sancties tegen landen voortaan met een gekwalificeerde meerderheid nemen’ (lees: de resterende staatssoevereiniteit van de lidstaten moet nog verder worden verkleind). En inderdaad ontwikkelt de EU zich steeds meer in de richting van een ‘superstaat’: de gestage accumulatie van censuurmaatregelen in de mediale en digitale sfeer met hate speech codes,[3] fake news taskforces[4] en copyright directives[5] neemt inmiddels Orwelliaanse vormen aan. Met de totalitaire finish lijn van het EU project in zicht, is het goed de historische ontwikkeling en ideologische grondslagen ervan nog eens de revue te laten passeren.

De aanstaande Europese verkiezingen, waarmee het globalistisch-eurocratisch regime in Brussels zich nogmaals vier jaar een ‘democratische’ dekmantel wil aanmeten, biedt een goede gelegenheid tot een gedegen heroverweging van het ‘EU project’. De democratische camouflagekleding van het EU keizerrijk is inmiddels echter zodanig afgedragen dat zelfs troonopvolger kandidaat Mark Rutte zich afvraagt of het niet tijd is om het gewoon maar om te kleden in onverhuld totalitaire ‘uniform’ stijl. De titel van zijn op 13 februari 2019 in Zürich uitgesproken - en door analisten als ‘sollicitatiebrief’ nummer zoveel geïnterpreteerde[1] - ‘Churchill Lezing’ spreekt in dit opzicht boekdelen: The EU: from the power of principles towards principles and power.[2] Ofwel: ‘De EU: van de macht van principes naar principes en macht’. ‘Naar machtsprincipe’ zegt hij nog net niet, maar de inhoud windt er geen doekjes om: ‘het gaat in de wereld om macht en macht is geen vies woord’ (lees: de EU heeft machtsmiddelen die onvoldoende worden gebruikt), ‘de EU moet minder naïef zijn en meer realisme tonen’ (lees: het is tijd voor de EU het idealistisch masker laat vallen) en ‘we moeten besluiten over sancties tegen landen voortaan met een gekwalificeerde meerderheid nemen’ (lees: de resterende staatssoevereiniteit van de lidstaten moet nog verder worden verkleind). En inderdaad ontwikkelt de EU zich steeds meer in de richting van een ‘superstaat’: de gestage accumulatie van censuurmaatregelen in de mediale en digitale sfeer met hate speech codes,[3] fake news taskforces[4] en copyright directives[5] neemt inmiddels Orwelliaanse vormen aan. Met de totalitaire finish lijn van het EU project in zicht, is het goed de historische ontwikkeling en ideologische grondslagen ervan nog eens de revue te laten passeren.

Het Verdrag van Maastricht dat de formele grondslag legde voor de huidige Europese Unie werd getekend op 7 februari 1992, zes weken na de formele opheffing van de Sovjet Unie: zo begon de opbouw van het nieuwe cultuurmarxistische Westblok direct na de afbraak van het oude reaalsocialistische Oostblok. Sindsdien heeft de EU zich niet alleen naar buiten toe sterk uitgebreid (met name door de haastige inlijving van de net uit het Oostblok ontsnapte Centraal-Europese natiestaten), maar zij heeft zich ook in rap tempo als proto-totalitair ‘superstaat’ project naar binnen toe ontwikkeld tot een waardige opvolger van de Sovjet Unie. De overeenkomsten zijn in toenemende mate frappant: dezelfde sociale ‘deconstructie’ (Oostblok: hyper-proletarisch collectivisme / Westblok: neo-matriarchale nivellering), dezelfde economische ‘deconstructie’ (Oostblok: ‘dwangcollectivisatie’ / Westblok: ‘rampen kapitalisme’) en dezelfde etnische ‘deconstructie’ (Oostblok: ‘groepsdeportatie’ / Westblok: ‘omvolking’). De tegenstelling tussen het theoretisch discours van het liberaal-normativisme (‘vrijheid’, ‘gelijkheid’, ‘democratie’, ‘rechtsstaat’, ‘mensenrechten’) en de praktische leefrealiteit van maatschappelijke degradatie (sociaal-darwinistische economische tweedeling, sociale implosie, institutionele corruptie, endemische criminaliteit, etnische vervanging) neemt in het huidige Westblok even groteske vormen aan als in het voormalige Oostblok. In zeker opzichten is het Westblok zelfs verder doorgeschoten in de richting van een ‘superstaat’: zo staat de EU vlag in alle lidstaten obligaat naast de nationale vlag - een directe degradatie van nationale waardigheid die zelfs de formeel onafhankelijke Sovjet satellietstaten bespaard bleef.

Met deze escalerende discrepantie tussen theorie en praktijk is de heersende klasse van het Westblok - een globalistisch-eurocratisch opererende coalitie tussen het neoliberale grootkapitaal en de cultuurmarxistische intelligentsia - inmiddels verworden tot een regelrecht vijandelijke elite. Haar EU project heeft ontpopt zich tot een voor allen zichtbaar globalistisch anti-Europa project. Voor het overleven van de Europese beschaving en van de Europese inheemse volkeren die deze beschaving dragen is de verwijdering van de vijandelijke elite absolute noodzaak. Daarbij is een fundamentele (cultuurhistorische, politiekfilosofische) kritiek op haar ideologie van essentieel belang. Een belangrijke bijdrage tot deze kritiek is recent geleverd door Belgisch Traditionalistisch publicist Robert Steuckers - een passender ‘verkiezingswijzer’ voor de ‘Europese verkiezingen’ van mei 2019 dan zijn grote trilogie Europa is nauwelijks denkbaar. Dit essay beoogt Steuckers’ analyse van de echte kernwaarden en identitaire wortels van Europa, zoals vervat in het eerste deel van zijn nog niet uit het Frans vertaalde trilogie, onder de aandacht van het Nederlandstalige publiek te brengen. Steuckers’ Europa I biedt meer dan een grondige tegen-analyse van de postmoderne ‘deconstructie’ van Europa’s authentieke waarden en identiteiten: het biedt een heldere formule van een levensvatbaar alternatief: een Archeo-Futuristisch geïnspireerd ‘Europa van de volkeren’ gebaseerd op de complementaire principes van autonome volksgemeenschappen, consistente politieke subsidiariteit en pragmatische confederatieve structuren. Het moet nogmaals gezegd zijn: de patriottisch-identitaire beweging van de Lage Landen is Robert Steuckers grote dank verschuldigd - en een hartelijke felicitatie met een werk dat de gewoonlijk nogal bescheiden intellectuele begrenzingen van onze gewesten verre te boven gaat.

Met deze escalerende discrepantie tussen theorie en praktijk is de heersende klasse van het Westblok - een globalistisch-eurocratisch opererende coalitie tussen het neoliberale grootkapitaal en de cultuurmarxistische intelligentsia - inmiddels verworden tot een regelrecht vijandelijke elite. Haar EU project heeft ontpopt zich tot een voor allen zichtbaar globalistisch anti-Europa project. Voor het overleven van de Europese beschaving en van de Europese inheemse volkeren die deze beschaving dragen is de verwijdering van de vijandelijke elite absolute noodzaak. Daarbij is een fundamentele (cultuurhistorische, politiekfilosofische) kritiek op haar ideologie van essentieel belang. Een belangrijke bijdrage tot deze kritiek is recent geleverd door Belgisch Traditionalistisch publicist Robert Steuckers - een passender ‘verkiezingswijzer’ voor de ‘Europese verkiezingen’ van mei 2019 dan zijn grote trilogie Europa is nauwelijks denkbaar. Dit essay beoogt Steuckers’ analyse van de echte kernwaarden en identitaire wortels van Europa, zoals vervat in het eerste deel van zijn nog niet uit het Frans vertaalde trilogie, onder de aandacht van het Nederlandstalige publiek te brengen. Steuckers’ Europa I biedt meer dan een grondige tegen-analyse van de postmoderne ‘deconstructie’ van Europa’s authentieke waarden en identiteiten: het biedt een heldere formule van een levensvatbaar alternatief: een Archeo-Futuristisch geïnspireerd ‘Europa van de volkeren’ gebaseerd op de complementaire principes van autonome volksgemeenschappen, consistente politieke subsidiariteit en pragmatische confederatieve structuren. Het moet nogmaals gezegd zijn: de patriottisch-identitaire beweging van de Lage Landen is Robert Steuckers grote dank verschuldigd - en een hartelijke felicitatie met een werk dat de gewoonlijk nogal bescheiden intellectuele begrenzingen van onze gewesten verre te boven gaat.

(*) Zoals de voorafgaande ‘Steuckers recensies’[6] is dit essay niet alleen bedoeld als boekbespreking, maar ook als metapolitieke analyse - een bijdrage tot de patriottisch-identitaire tegen-deconstructie van het door de Westerse vijandelijke elite gehanteerde postmoderne deconstructie discours. De kern van dit essay is een samenvatting door Steuckers’ Traditionalistisch geleide exploratie van de Europese identiteit. Die exploratie zet een definitieve punt achter de postmoderne deconstructie van die identiteit en het aldus bewerkstelligde cultuurhistorische tabula rasa stelt de patriottisch-identitaire beweging in staat een revolutionair nieuwe invulling te geven aan het idee ‘Europa’. Een Archeo-Futuristisch Europa ligt daarmee feitelijk binnen intellectueel handbereik.

(**) Dit essay belicht ‘casus Europa’ in drie stappen: het eerste drietal paragraven beoogt diagnostische ‘nulmetingen’, het tweede drietal paragraven geeft therapeutische ‘referentiepunten’ en de zevende paragraaf indiceert een concreet ‘behandelplan’. In eerste en laatste paragraven schetst de recensent het grotere Archeo-Futuristische kader weer waarbinnen Steuckers’ exploratie van de Europese identiteit relevant is voor de patriottisch-identitaire beweging - de eigenlijke ‘recensie’ van Steuckers’ Europa I vindt de lezer in paragraven 2 t/m 6.

(***) Voor een toelichting op de gekozen (ver)taal(vorm) en (voet)noten(last) wordt verwezen naar het voorwoord van de voorafgaande ‘Steuckers recensies’.

1.

Het rode onkruid

(psycho-historische diagnose)

‘Over Your Cities Grass Will Grow’[7]

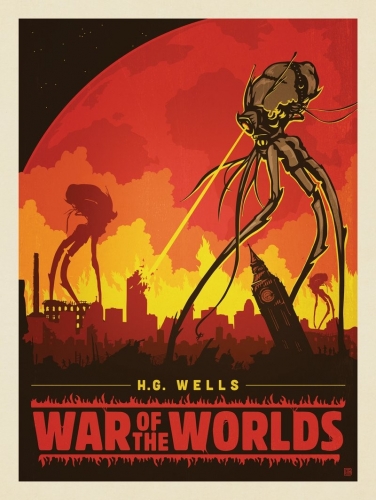

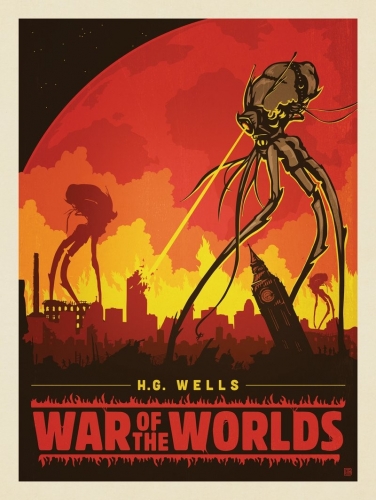

H.G. Wells’ eeuwig groene meesterwerk The War of the Worlds blijft tot op de dag van vandaag niet alleen een van de grootste werken van het hele literaire science fiction genre: het behoudt ook tot op de dag van vandaag een directe - veelal alleen onderbewust, instinctief erkende - relevantie voor de existentiële conditie van de Westerse beschaving.[8] Wells’ magistrale sfeerimpressie van de Earth under the Martians schetst een wereld waarin de mens alle herkenning- en referentiepunten verliest: de menselijke beschaving wordt weggevaagd door superieure buitenaardse technologie, de mensheid zelf wordt gereduceerd tot slachtvee voor een buitenaardse bezettingsmacht en zelfs de aardse natuur wordt verdrongen door buitenaardse vegetatie. Een griezelig ‘rood onkruid’ - in verwijzing naar de rode kleur van de oorlogsplaneet Mars - overwoekert de ruïnes van de menselijke beschaving en verstikt de restanten van de aardse vegetatie.[9] Literaire analyses van The War of the Worlds erkennen dat Wells’ meesterwerk op aannemelijk wijze kan worden geïnterpreteerd als een serie retrospectieve en contextuele psycho-historische ‘bespiegelingen’. Zo projecteert Wells de in zijn tijd recent afgeronde en sociaaldarwinistisch geïnterpreteerde genocide van ‘primitieve volkeren’ (zoals de inheemse bevolking van Tasmanië)[10] door het ‘blanke meesterras’ op een hypothetische uitroeiing van de mensheid door superieur buitenaards ras. Ook projecteert hij de mensonterende horreur van de in zijn tijd opkomende bio-industrie op een hypothetische ‘slachtvee status’ van de mensheid na een buitenaardse invasie. Waar de meeste literaire analyses zich echter niet mee bezig houden is de voorspellende waarde van Wells’ werk, een waarde die het ontleent aan de voorwaartse projectie van meerdere - en gelijktijdige - technologische en sociologische ontwikkelingstrajecten. Wells’ geniale literaire verpakking van deze projecties geeft zijn ‘wetenschappelijke fictie’ een kwaliteit die in eerdere eeuwen als ‘profetisch’ zou hebben gegolden.

H.G. Wells’ eeuwig groene meesterwerk The War of the Worlds blijft tot op de dag van vandaag niet alleen een van de grootste werken van het hele literaire science fiction genre: het behoudt ook tot op de dag van vandaag een directe - veelal alleen onderbewust, instinctief erkende - relevantie voor de existentiële conditie van de Westerse beschaving.[8] Wells’ magistrale sfeerimpressie van de Earth under the Martians schetst een wereld waarin de mens alle herkenning- en referentiepunten verliest: de menselijke beschaving wordt weggevaagd door superieure buitenaardse technologie, de mensheid zelf wordt gereduceerd tot slachtvee voor een buitenaardse bezettingsmacht en zelfs de aardse natuur wordt verdrongen door buitenaardse vegetatie. Een griezelig ‘rood onkruid’ - in verwijzing naar de rode kleur van de oorlogsplaneet Mars - overwoekert de ruïnes van de menselijke beschaving en verstikt de restanten van de aardse vegetatie.[9] Literaire analyses van The War of the Worlds erkennen dat Wells’ meesterwerk op aannemelijk wijze kan worden geïnterpreteerd als een serie retrospectieve en contextuele psycho-historische ‘bespiegelingen’. Zo projecteert Wells de in zijn tijd recent afgeronde en sociaaldarwinistisch geïnterpreteerde genocide van ‘primitieve volkeren’ (zoals de inheemse bevolking van Tasmanië)[10] door het ‘blanke meesterras’ op een hypothetische uitroeiing van de mensheid door superieur buitenaards ras. Ook projecteert hij de mensonterende horreur van de in zijn tijd opkomende bio-industrie op een hypothetische ‘slachtvee status’ van de mensheid na een buitenaardse invasie. Waar de meeste literaire analyses zich echter niet mee bezig houden is de voorspellende waarde van Wells’ werk, een waarde die het ontleent aan de voorwaartse projectie van meerdere - en gelijktijdige - technologische en sociologische ontwikkelingstrajecten. Wells’ geniale literaire verpakking van deze projecties geeft zijn ‘wetenschappelijke fictie’ een kwaliteit die in eerdere eeuwen als ‘profetisch’ zou hebben gegolden.

De existentiële breuklijnen die de Moderniteit heeft veroorzaakt in de Westerse beschaving kunnen worden geanalyseerd - en deels ook vooruit geprojecteerd - met verschillende moderne wetenschappelijk modellen: economisch als Entfremdung (Karl Marx), sociologisch als anomie (Emile Durkheim), psychologisch als cognitive dissonance (Leon Festinger) en filosofisch als Seinsvergessenheit (Martin Heidegger). De metapolitieke relevantie van deze analyses voor de Westerse patriottisch-identitaire bewegung ligt niet zozeer in hun - al dan niet ideologisch negatieve - ‘deconstructieve’ capaciteit, als wel in hun simpele diagnostische waarde. Hierin ligt een belangrijke overeenkomst tussen deze moderne wetenschappelijke modellen en moderne artistieke ‘modellen’ zoals Wells’ meesterwerk The War of the Worlds: door ‘maatschappelijke signalen’ te interpreteren dienen ze als metapolitieke ‘verkeersborden’ - en als waarschuwingen. Inmiddels is de accumulatieve impact van de Moderniteit op de Westerse samenlevingen echter zó groot geworden, dat de existentiële conditie van de Westerse volkeren niet langer in termen van authentieke beschavingscontinuïteiten en historische standaardmodellen kan worden beschreven. Wanneer afwijking, aberratie en ontsporing een existentiële conditie volledig bepalen, dan is er immers niet langer sprake van een historische herkenbare ‘standaard’. Wanneer wetenschappelijke ‘waarschuwingsborden’ worden genegeerd, dan komen artistiek ‘voorspelde’ dystopische eindbestemmingen in zicht. Niet voor niets wordt deze fase van de (ex-)Westerse beschavingsgeschiedenis getypeerd als ‘post-modern’: de (ex-)Westerse samenlevingen van nu hebben authentieke beschavingscontinuïteit grotendeels achter zich gelaten en bewegen zich versneld in de richting van existentiële condities die overeenkomsten vertonen die van Wells’ Earth under the Martians.

De nieuwe ‘globalistische’ heersersklasse van het Westen staat nu in effectief boven en los van de Westerse volkeren, zij is alleen nog ‘verbonden’ met deze volkeren in de uitwerking van haar macht. De vijandelijke elite acht zichzelf nu niet alleen ethisch en esthetisch, maar ook en vooral evolutionair verheven boven de ‘massa’ die zij is ‘ontgroeit’.[11] De consistent negatieve effecten van haar machtsuitoefening - hoofdrichtingen: neo-liberale uitbuiting, industriële ecocide, bio-industriële dierkwellerij, cultuur-marxistische deconstructie, sociale implosie, etnische vervangingsstrategieën - maken haar herkenbaar als een letterlijk vijandelijke elite. Zij kent geen sympathieën – niet voor haar autochtone vijanden, niet voor haar allochtonen dienaren en niet voor haar aardse thuis. The globalists are at war with humanity as a whole. They seek to eliminate or enslave at will. They care about themselves and themselves alone. They are committed to concentrating all wealth in their hideous hands. In their evil eyes, our only purpose is to serve them and enrich them. Hence, there is no room for racism, prejudice, and discrimination in this struggle. It is not a race war but a war for the human race, all included, a socio-political and economic war of planetary proportions (Jean-François Paradis).[12]

De globalistische en dus anti-Europese geopolitieke strategie van de vijandelijke elite (gericht op industriële delokalisatie, sociale atomisering en culturele ontworteling, verg. Steuckers 223ff.) mag als zodanig - als sociaaleconomische en psychosociale oorlogsvoering - worden erkend door een handjevol patriottisch-identitaire denkers, maar zij wordt door de Westerse volksmassa alleen begrepen in haar uitwerkingen: economische marginalisatie (arbeidsmarktverdringing, kunstmatige werkeloosheid, interetnische tribuutplicht), sociale malaise (matriarchale anti-rechtstaat, gezinsontwrichting, digitale pornificatie) en culturele decadentie (onderwijs ‘idiocratie’, academische ‘commercialisering, ‘politiekcorrecte’ mediaconsensus). Deze economische, sociale en culturele ‘deconstructie’ programma’s worden door de vijandelijke elite kracht bijgezet en onomkeerbaar gemaakt door een zorgvuldig gedoseerd, maar inmiddels kritieke proporties aannemend proces van massa-immigratie. Het proces van etnische vervanging heeft tot doel de Westerse volkeren als etnisch, historisch en cultureel herkenbare eenheden te elimineren door ze als geatomiseerde déracinés ‘op te lossen’ in la boue,[13] de ‘modder’ van identiteitsloze, karakterloze en willoze massamens. Dit proces van etno-culturele, sociaal-economische en psycho-sociale totaal-nivellering beoogt - prioritair richting Europa - de ultieme Endlösung van het kernprobleem van de Nieuwe Wereld Orde, dat wil zeggen van het automatisch anti-globalistisch voortbestaan van authentieke identiteiten op collectief niveau. Concreet wordt deze Endlösung gerealiseerd in totalitair geïmplementeerde etnocidale ‘multiculturaliteit’ en anti-identitaire ‘mobocratie’.

De motivaties en doelstellingen van de vijandelijke elite onttrekken zich feitelijk aan het voorstellingsvermogen van de Westerse volksmassa - ze gaan in zekere opzichten het gewone menselijk verstand ‘te boven’. Hun ‘niet-aardse’ en ‘diabolische’ kwaliteit wordt echter in toenemende mate waarneembaar in hun concrete uitwerkingen.[14] Elders werd de ideologie van de vijandelijke elite gedefinieerd als ‘Cultuur Nihilisme’: een geïmproviseerde ideeëncocktail die zich kenmerkt door militant secularisme, sociaal-darwinistisch hyper-individualisme, collectief geïnternaliseerd narcisme en doctrinair cultuur- relativisme die uitmondt in de vernietiging van alle authentieke Westerse beschavingsvormen.[15] Het feit dat de volksmassa niet in staat het Cultuur Nihilisme als ideologie en programma te begrijpen heeft veel te maken met de opzettelijke ‘ongrijpbaarheid’ ervan: de expliciete motivaties en doelstellingen van de vijandelijke elite zijn intentioneel on-logisch en anti-rationeel. Het enige wat voor de vijandelijke elite telt is haar macht - haar zogenaamde ‘ideeën’ zijn slechts manoeuvres om de macht te krijgen, te behouden en te vergroten: ze dienen te worden begrepen in het kader van cognitieve oorlogsvoering.

Een goed voorbeeld van deze cognitieve oorlogsvoering is het huidige ‘klimaatdebat’: de door de vijandelijke elite uitgestippelde ‘partijkartel lijn’ beroept zich op Gutmensch eco-bewustzijn, maar het op basis van deze lijn via nieuwe ‘klimaatbelastingen’ aan de volksmassa opgelegde ‘straftarief’ wordt exclusief aangewend voor het ‘investeren’ in het commerciële ‘klimaat bedrijf’ – en het subsidiëren van politiek-correcte ‘klimaat clubs’. Het onvermijdbare verzet van de volksmassa wordt vervolgens cognitief ‘weggesluisd’ naar een subrationeel ‘klimaatontkenning’ discours dat wordt toegeschreven aan – en zelfs opportunistisch wordt opgeëist door – de ‘populisten’, activistisch (Frankrijk’s ‘gele hesjes’) dan wel parlementair (Baudet’s ‘0,00007 graden’). De daarbij succesvol bewerkstelligde opgelegde cognitieve dissonantie inzake ‘klimaat’ gaat zover dat men in de volksmassa het verdwijnen van winterijs en het toeslaan van februarilentes instinctief wegredeneert. De balanceerakte van de vijandelijke elite is feilloos: de ‘populistische oppositie’ is blij met een paar extra zeteltjes maar verspeelt haar échte moreel aanzien, de volksmassa is blij nog een paar jaartjes ‘dansen op de vulkaan’ met vakantievliegen en autorijden en de vijandelijke elite is blij dat haar ‘economische groei’ ongestoord oploopt – en met de extra ‘klimaatbelastingen’ die kunnen worden aangewend voor ‘commerciële aanbestedingen’ en, natuurlijk, ‘klimaat vluchtelingen’. Ondertussen loopt de ecocidale klok van antropogene aardopwarming en meteorologische catastrofes gewoon door - naar de final countdown.

De Westerse volksmassa erkent per saldo wel instinctief de globalistische grootheidswaanzin van de vijandelijke elite - deze instinctieve erkenning wordt door de elitaire intelligentsia veelal neerbuigend afgedaan als ‘onderbuikgevoel’ en de politieke vertaling ervan wordt al even neerbuigend betiteld als ‘populisme’. Deze ultiem demofobe arrogantie mag lang werken, maar er zal uiteindelijk wel een hoge prijs op staan: de Westerse volkeren ervaren het globalistische regime van de vijandelijke elite nu al in toenemende mate als een regelrechte ‘bezettingsmacht’. Men begint de alles verstikkende macht van de vijandelijke elite te zien voor wat zij is: een wezensvreemd ‘rood onkruid’ dat de Westerse beschaving en het Westerse thuisland versmoort.

De Westerse volksmassa erkent per saldo wel instinctief de globalistische grootheidswaanzin van de vijandelijke elite - deze instinctieve erkenning wordt door de elitaire intelligentsia veelal neerbuigend afgedaan als ‘onderbuikgevoel’ en de politieke vertaling ervan wordt al even neerbuigend betiteld als ‘populisme’. Deze ultiem demofobe arrogantie mag lang werken, maar er zal uiteindelijk wel een hoge prijs op staan: de Westerse volkeren ervaren het globalistische regime van de vijandelijke elite nu al in toenemende mate als een regelrechte ‘bezettingsmacht’. Men begint de alles verstikkende macht van de vijandelijke elite te zien voor wat zij is: een wezensvreemd ‘rood onkruid’ dat de Westerse beschaving en het Westerse thuisland versmoort.

I had not realised what had been happening to the world, had not anticipated this startling vision of unfamiliar things. I had expected to see... ruins - I found about me the landscape, weird and lurid, of another planet. For that moment I touched an emotion beyond the common range of men, yet one that the poor brutes we dominate know only too well. I felt as a rabbit might feel returning to his burrow and suddenly confronted by the work of a dozen busy navvies digging the foundations of a house. I felt the first inkling of a thing that presently grew quite clear in my mind, that oppressed me for many days, a sense of dethronement, a persuasion that I was no longer a master, but an animal among the animals, under [alien rule]. With us it would be as with them, to lurk and watch, to run and hide; the fear and empire of man had passed away. - Herbert George Wells, The War of the Worlds

2.

De Europese kata-morfose

(politiek-filosofische diagnose)

Impia tortorum long[o]s hic turba furores sanguinis innocui, non satiata, aluit.

Sospite nunc patria, fracto nunc funeris antro, mors ubi dira fuit,

vita salusque patent.

[Hier voedde een goddeloze en onverzadigbare meute beulsknechten

hun lange waanwoedes met het bloed der onschuldigen.

Pas nu het vaderland veilig is, nu deze moordkelder opengebroken is,

zijn leven en gezondheid weer mogelijk.][16]

Na een halve eeuw systematische sloop van staatsstructuren en volksidentiteiten is het Europese politieke, economische, sociale en culturele landschap nagenoeg onherkenbaar veranderd. Decennialange neoliberale woeker en cultuurmarxistische wildgroei hebben als Europa als een ‘rood onkruid’ in hun greep en vroeger onvoorstelbare ‘maatschappelijke vormen’ zijn ontstaan. Hypermobiel ‘flitskapitaal’ levert kortstondige economische bubbels op waarin zich architecturale, artistieke en modieuze monstruositeiten nestelen, met name in central business districts, leisure time resorts en academic campus environments. Etnische ‘diversiteit’ resulteert in sociaaleconomische netwerken die als ‘invasieve exoten’ de Westerse publieke sfeer overwoekeren: diaspora economieën, drugsmaffia’s, polycriminele subculturen. Deze netwerken worden aangevuld door on-Westerse ‘levensovertuigelijke’ instituties: de door Midden-Oosters oliekapitaal aangestuurde awqāf,[17] de uit belastingtribuut bekostigde ‘asielindustrie’ en de door globalistisch kapitaal aangestuurde systeemmedia. Wat deze door de vijandelijke elite effectief gedoogde en gefaciliteerde netwerken en instituties met elkaar verbindt is hun gemeenschappelijke functionaliteit: hun rol als vervangingsmechanismen ter bewerkstelligen van de Nieuwe Wereld Orde. Hierbij valt een cruciale voortrekkersrol toe aan die schwebende Intelligenz: de cultuur-marxistische intelligentsia die zich opwerpt als globalistische avant-garde. Deze intelligentsia is belast met de bovenruimtelijke en im-materiële deconstructie die voorafgaat aan de ruimtelijke en materiële deconstructie van de Westerse beschaving. Deze ‘spirituele’ en ‘intellectuele’ voorsprekers van het globalistische bezettingsregime ...se nichent dans [l]es trois milieux-clefs - média, économie, enseignement - et participent à la élimination graduelle mais certaines des assises idéologiques, des fondements spirituels et éthiques de notre civilisation. Les uns oblitèrent les résidus désormais épars de ces fondements en diffusant une culture de variétés sans profondeur aucune, les autres en décentrant l’économie et en l’éclatant littéralement par les pratiques de la spéculation et de la délocalisation, les troisièmes, en refusant l’idéal pédagogique de la transmission, laquelle est désormais interprétée comme une pratique anachronique et autoritaire, ce qu’elle n’est certainement pas au sens péjoratif que ces termes ont acquis dans le sillage de Mai 68. [...hebben zich genesteld in [de] drie sleutelposities [van de globalistische macht] - de media, de economie [en] het onderwijs - en zij werken van daar uit aan de langzame maar zekere eliminatie van de ideologische, spirituele en ethische fundamenten van onze beschaving. Sommigen van hen werken aan het wegwissen van de toch al uiteengevallen fundament restanten door een oppervlakkige ‘culturele diversiteit’ te verspreiden. Anderen [werken aan] de ‘decentralisatie’ van de economie door haar letterlijk op te blazen door middel van speculatie en dislokalisatie. Weer anderen [werken aan] de sabotage van het pedagogische ideaal van [culturele] transmissie door [dat ideaal] af te doen als een ‘verouderde’ en ‘autoritaire’ praktijk door [gebruik te maken van] de negatieve betekenis waarmee deze termen zijn belast in de nasleep van mei ’68.] (p. 262-3)

De globalistische intelligentsia coördineert middels geraffineerde alien audience propaganda strategieën de cognitieve oorlogsvoering van de vijandelijke elite tegen de Westerse volkeren: zij bewerkstelligt de liberaal-normativistische habitus van exclusief ‘economisch denken’ dat de fysieke deconstructie van Westerse beschavingsvormen rechtvaardigt. ...[U]ne économie ne peut pas, sans danger, refuser par principe de tenir compte des autres domaines de l’activité humaine. L’héritage culturel, l’organisation de la médecine et de l’enseignement doivent toujours recevoir une priorité par rapport aux facteurs purement économiques, parce qu’ils procurent ordre et stabilité au sein d’une société donnée ou d’une aire civilisationnelle, garantissant du même coup l’avenir des peuples qui vivent dans cet espace de civilisation. Sans une telle stabilité, les peuples périssent littéralement d’un excès de libéralisme, ou d’économicisme ou de ‘commercialité’... [Een economi[sch model] kan niet ongestraft weigeren rekening te houden met de andere domeinen van menselijke activiteit. De culturele nalatenschap, het medische zorgsysteem en de onderwijstechnische organisatie moeten altijd prioriteit krijgen boven puur economische factoren want zij verschaffen orde en stabiliteit aan een gegeven gemeenschap of beschavingssfeer: zij garanderen namelijk de toekomst van de volkeren die leven binnen die beschavingssfeer. Zonder die stabiliteit sterven d[ie] volkeren letterlijk aan een overdosis van ‘liberalisme’, ‘economisme’ en ‘commercialisme’...] (p. 216-7)

In de Europese context wordt de dubbel neoliberale en cultuurmarxistische deconstructie van de Westerse beschaving en volkeren geïmplementeerd door het in Brussel gebaseerde ‘EU project’. Dit project wordt gekenmerkt door een radicale omkering van alle traditionele noties van pan-Europese samenwerking: in metahistorische zin staat het postmoderne ‘EU project’ in structurele tegenstelling tot de klassieke Europese rijksgedachte. L’Europe actuelle, qui a pris la forme de l’eurocratie bruxelloise, n’est évidemment pas un empire, mais, au contraire, un super-état en devenir. La notion d’‘état’ n’a rien à voir avec la notion d’‘empire’, car un ‘état’ est ‘statique’ et ne se meut pas, tandis que, par définition, un empire englobe en son sein toutes les formes organiques de l’aire civilisationnelle qu’il organise, les transforme et les adapte sur les plans spirituel et politique, ce qui implique qu’il est en permanence en effervescence et en mouvement. L’eurocratie bruxelloise conduira, si elle persiste dans ses errements, à une rigidification totale. L’actuelle eurocratie bruxelloise n’a pas de mémoire, refuse d’en avoir une, a perdu toute assise historique, se pose comme sans racines. L’idéologie de cette construction de type ‘machine’ relève du pur bricolage idéologique, d’un bricolage qui refuse de tirer des leçons des expériences du passé. Cela implique une négation de la dimension historique des systèmes économiques réellement existants, qui ont effectivement émergé et se sont développés sur le sol européen. [Het huidige ‘Europa’, zoals het vorm wordt gegeven door de Brusselse ‘eurocratie’, is duidelijk geen rijk - het is het omgekeerde: een superstaat-in-wording. De notie van een ‘staat’ staat volledig los van de notie van een ‘rijk’, want een ‘staat’ is [letterlijk] ‘statisch’ en [in zijn essentie] onbewegelijk, terwijl een rijk nu juist alle binnen de erdoor beheerste beschavingssfeer organische vormen incorporeert, omvormt en aanpast aan zijn spirituele en politieke grondslagen: [een rijk] is daardoor nu juist permanent in een staat van gisting en beweging. Als de Brusselse eurocratie voortgaat op de door haar ingeslagen [tegengestelde en] doodlopende weg, dan zal zij uitlopen op een totale ‘verstening’. De Brusselse eurocratie van vandaag ontbeert - en weigert - [elk soort historisch] geheugen, heeft elk [soort] historisch fundament verloren en zet zich af tegen [elk soort historische] worteling. [Haar radicaal] constructivistische en mechanische zelfbegrip berust op een ideologische improvisatie die weigert om uit de lessen en ervaringen van de [Europese] geschiedenis te leren. Dit behelst een ontkenning van de historische dimensie van de [specifieke en volkseigen - althans tot voor kort -] echt bestaande economische systemen die [organisch] zijn voortgekomen en zich hebben ontwikkeld uit de Europese bodem.] (p. 215-6)

In politiek-filosofisch perspectief vertegenwoordigt het essentieel anti-Europese ‘EU project’ niets meer en minder dan een globalistische Machtergreifung. Neo-Jacobijnse radicalen hebben de macht overgenomen en historische precedenten met betrekking tot Jacobijnse machtsexperimenten[18] - met name de Franse en Russische revolutionaire terreur - geven aanleiding tot zorg. Kennis van de Europese historische context van het ‘EU project’ is echter onvoldoende voor een echt begrip van de ogenschijnlijk tegenstrijdige - want zelfdestructieve - anti-Europese doelstellingen van dat project. Zulk begrip vergt inzicht in de grotere doelstellingen van het globalisme - dat inzicht wordt nu in hapklare brokken aangeleverd in Steuckers’ Europa.

3.

Het globalistische anti-Europa

(geo-politieke diagnose)

Soms is de misdaad die men wil begaan zo groot,

dat het niet volstaat haar te begaan namens een volk:

dan moet men haar begaan namens de mensheid.

- Nicolás Gómez Dávila

Steuckers’ panoramische overzicht van de hedendaagse mondiale geopolitiek herleidt de oorsprong van het anti-Europese ‘EU project’ tot het einde van de Tweede Wereld Oorlog. Dit conflict bracht een einde aan de grootmacht status en imperiale hegemonie van de Europese natie-staten: de militaire nederlagen van Frankrijk in 1940, Italië in 1943 en Duitsland in 1945 werden gevolgd door de liquidatie van alle Europese koloniale rijken (Brits Indië in 1947, Nederlands Indië in 1949, Belgisch Congo in 1960, Frans Algerije in 1962 en Portugees Afrika in 1975). De wereldheerschappij werd in kort tijdbestek overgenomen door twee supermachten die beide op een universalistische ideologie en een mondiale geopolitiek inzetten: de Verenigde Staten als voorvechter van het Liberalisme en de Sovjet Unie als voorvechter van het Socialisme. Het fysieke (geografische, demografische, industriële) restbestand ‘Europa’ werd met militaire verdragen (NAVO, Warschau Pact) en economische samenwerkingsverbanden (EEG, Comecon) vervolgens tussen de overwinnaars verdeeld. Het is belangrijk de brute realiteiten van militaire nederlaag, koloniale liquidatie en politieke ontvoogding voor ogen te houden. La Seconde Guerre mondiale avait pour objectif principal, selon Roosevelt et Churchill, d’empêcher l’unification européenne sous la férule des puissances de l'Axe, afin d’éviter l’émergence d’une économie ‘impénétrée’ et ‘impénétrable’, capable de s’affirmer sur la scène mondiale. La Seconde Guerre mondiale n’avait donc pas pour but de ‘libérer’ l’Europe mais de précipiter définitivement l’économie de notre continent dans un état de dépendance et de l’y maintenir. Je n’énonce donc pas un jugement ‘moral’ sur les responsabilités de la guerre, mais je juge son déclenchement au départ de critères matériels et économiques objectifs. Nos médias omettent de citer encore quelques buts de guerre, pourtant clairement affirmés à l’époque, ce qui ne doit surtout pas nous induire à penser qu’ils étaient insignifiants. [Volgens Roosevelt en Churchill was het hoofddoel van de Tweede Wereld Oorlog te verhinderen dat Europa zich verenigde onder leiding van de As mogendheden, om zo te voorkomen dat er een [Europese] economie zou ontstaan die zich op het wereldtoneel als ‘ondoordringbaar’ en ‘onverslaanbaar’ zou kunnen handhaven. [Hun] Tweede Wereld Oorlog had dus niet ten doel om Europa te ‘bevrijden’, maar om de economie van ons continent te doel vervallen tot een staat van afhankelijkheid - en daarin te houden. Daarmee doe ik dus geen uitspraak over de ‘morele’ verantwoordelijkheid voor die oorlog - ik beoordeel [slechts] zijn uitbreken vanuit objectieve materiële en economische doelen. Het feit dat onze media [ook] de vermelding van een aantal andere oorlogsdoelen vermijden die toentertijd duidelijk werden verkondigd moet ons er niet toe brengen te denken dat die [doelen] onbelangrijk waren.] (p.220)

Na veertig jaar Koude Oorlog beginnen zich midden jaren ’80 de eerste tekenen stressfracturen af te tekenen in de globaal opererende machtsmachines van de twee supermachten. De rampen met de Challenger en Chernobyl (28 januari en 26 april 1986) laten duidelijk zien dat de symptomen van imperial overstretch niet langer te verbergen zijn. Escalerende economische chaos en toenemend politieke gezagsverlies dwingen beide supermachten tot ingrijpende binnenlandse maatregelen: Reaganomics en Perestrojka markeren de geopolitieke vloedlijn van de supermachten. Na de implosie van de Sovjet Unie is de Verenigde Staten de officiële winnaar van de Koude Oorlog maar de Pyrrus-kwaliteit van de formele overwinning blijkt uit het feit dat Amerika onvoorwaardelijk berust in de sensationele opkomst van de Chinese economische supermacht en zich effectief terugtrekt uit de eerder felomstreden Derde Wereld. Na de Amerikaanse nederlaag in Somalië (Black Hawk Down, 1993) vervalt Afrika in failed states en neo-tribale chaos. Na de Amerikaanse evacuatie uit Panama (Canal Zone Handover, 1999) wordt Latijns Amerika overgelaten aan Bolivarianismo en Marea Rosa.[19] De imperiale rat race tussen de soevereine natiestaten die begon met de Zevenjarige ‘Wereld Oorlog Nul’ (1756-63) mag dan zijn geëindigd met Amerika als last man standing, maar het opleggen van een authentiek-imperiale Pax Americana ligt ver buiten het bereik van Amerika’s geopolitieke intenties, ambities en capaciteiten. De met Wilsoniaanse retoriek ingeklede interventies van Bush Senior en Bush Junior in Irak in 1991 en 2003 waren geen exercities in principiële global governance, maar in pragmatische resource control. Na de zelfopheffing van de Sovjet Unie als supermacht concurrent en de afkondiging van de ‘nieuwe wereld orde’ (Bush Senior, 1991) besloot de Amerikaanse heersende klasse dat het ‘einde van de geschiedenis’ (Francis Fukuyama, 1992) gekomen is: zij schakelde over van Amerikanisme naar globalisme. Er ontstond zo een ‘wereld elite’, toegankelijk voor iedereen met heel veel geld en heel weinig moraliteit. Deze elite acht zich ontheven aan alle geopolitieke regels en wetmatigheden: staatsrechterlijke soevereiniteit, culturele eigenheid en etnische identiteit zijn in die optiek definitief achterhaalde fenomenen, obstakels op de door haar ingeslagen snelweg naar een Brave New World. Als geheel definieert zich deze nieuwe ‘globalistische’ elite los van alle etnische religieuze en culturele wortels: vanuit deze zelfgewilde ontworteling keert zij zich meteen tegen de rest van de nog wel gewortelde mensheid - tegen staten die nog soevereiniteit hebben, tegen culturen die nog essentie hebben en tegen volken die nog identiteit hebben. De globalistische vijandelijke elite is geboren.

Onder de dubbele banieren van neoliberalisme en cultuurmarxisme beschouwt de vijandelijke elite beschouwt het ‘achtergebleven’ menselijke ‘residu’ als weinig meer dan een oneindig ‘maakbare’ massa ‘mensenmateriaal’ dat kan worden gebruikt voor het aanvullen van banksaldi, het invullen van seksuele perversiteiten en het opvullen van existentiële leemtes. [La superclasse... domine à l’ère idéologique du néoliberalisme. Il n’est pas aisé de la définir : elle comporte évidemment les managers des grandes entreprises mondiales, les directeurs des grandes banques, de cheiks du pétrole ou des décideurs politiques voire quelques vedettes du cinéma ou de la littérature ou encore, en coulisses, des leaders religieux et des narcotrafiquants, qui alimentent le secteur bancaire en argent sale. Cette superclasse n’est pas stable : on y appartient pendant quelques années ou pendant une ou deux décennies puis on en sort, avec, un bon ‘parachute doré’. ...[N]umériquement insignifiante mais bien plus puissante que les anciennes aristocraties ou partitocraties, elle est totalement coupée des masses, dont elle détermine le destin. En dépit de tous les discours démocratiques, qui annoncent à cor et à cri l’avènement d’une liberté et d’une équité inégalées, le poids politique/économique des masses, ou des peuples, n’a jamais été aussi réduit. Son projet ‘globalitaire’ ne peut donc pas recevoir le label de ‘démocratique’. [De ‘superklasse’... domineert het tijdperk van de neoliberale ideologie. Het is niet gemakkelijk haar te definiëren: zij bestaat het duidelijkst uit de managers van de gro[ots]te multinationals, de directeuren van de gro[ots]te banken, de oliesjeiken [en bepaalde] politieke leiders, maar ook uit enkele filmsterren, intellectuelen en ‘spirituele leiders’ - en daarnaast uit een schimmiger personeelsbestand van [maffiabazen en] drugsbaronnen die de bankensector voeden met zwart geld. Deze ‘superklasse’ is verre van stabiel: men kan er enkele jaren of decennia toe behoren voordat men er weer uit valt - meestal met een ‘gouden parachute’. ...[N]umeriek is zij zeer klein, maar zij is machtiger dan alle voorafgaande aristocratieën en partitocratieën uit de menselijke geschiedenis. Zij is volledig afgesneden van de [volks]massa’s, waarvan zij het lot bepaalt. Ondanks het [publieke] discours dat continu spreekt over het aanbreken van weergaloze vrijheid en gelijkheid is het politieke [en] economische gewicht van de [volks]massa’s nog nooit [eerder in de geschiedenis] zo klein geweest. Het globalistische project [dat wordt nagestreefd door de ‘superklasse’] kan daarom in geen enkel opzicht ‘democratisch’ worden genoemd.] (p. 291)

De globalistische vijandelijke elite instrumentaliseert de militaire macht en politieke invloed van Amerika: zij wendt Amerikaanse macht en invloed aan voor globalistische doelen en wensen. Zij misbruikt het Amerikaans prestige, het Amerikaans vermogen en het Amerikaanse volk - dit is de diepste reden voor de anti-globalistische en nationalistische reactie die Donald Trump in het Witte Huis brachten. De vijandelijke elite opereert echter boven en achter Amerikaanse instituten als het presidentschap: in Amerika onttrekt de echte macht zich grotendeels aan institutionele controle en democratische correctie. De Washington swamp, de lying press en de deep state bepalen het beleid - het is voor de strijd tegen deze monsters dat het Amerikaanse volk Donald Trump tot president koos. De monsterlijke macht van de vijandelijke elite is echter zo groot dat ook twee jaar na Trump’s verkiezingsoverwinning de publieke sfeer nog steeds wordt gedomineerd door zijn vijanden. De onfatsoenlijke woede en openlijke sabotage waarmee de vijandelijke elite reageert op Trump is begrijpelijk: de globalistische vijandelijke elite valt en staat met haar grip op haar Amerikaanse instrumentarium. Alleen met controle over de Amerikaanse geldschepping, de Amerikaanse krijgsmacht en de Amerikaanse diplomatie is zij in staat de internationale geopolitieke chaos te handhaven waarin haar financiële belangen en ideologische waandenkbeelden gedijen.

Controle over Amerika is voor de globalistische vijandelijke elite vooral van belang voor het blijvend onderdrukken van haar potentieel machtigste vijand: Europa. Europa is een potentieel dodelijk gevaar voor het nihilistische en ontwortelde globalisme omdat het een ongeëvenaarde technologisch-industriële en sociaal-economische capaciteit combineert met authentieke cultuurhistorische en etnische worteling. Met het wegvallen van de Sovjet Unie eindigde de tweehoofdige ‘bewindvoering’ die aan het einde van de Tweede Wereld Oorlog werd opgelegd aan Europa. De geopolitieke opgave om Europa ‘klein te houden’ valt vervolgens toe aan Amerika alleen: de permanente verdragsmatige verzwakking van het verenigde Duitsland (vooral via monetaire convergentie met Frankrijk) en de Amerikaanse militaire expansie naar het oosten (vooral via uitbreiding van de NAVO) zijn basale ingrediënten van deze globalistische strategie. Toch blijkt deze strategie niet waterdicht: militaire aanwezigheid in Europa vergt een aanzienlijke en constante inspanning van een economisch en politiek mondiaal overbelast Amerika en zelfs de via de Europese eenheidsmunt (2002) afgedwongen tribuutplicht blijkt onvoldoende in staat de Duitse sociaaleconomische motor af te remmen. De EU expansie naar het voormalige Oostblok (2004) laat bovendien het gevaar herleven van een door Duitsland geleid semi-autarkisch geopolitiek blok - het tegenwerken van een dergelijk Mitteleuropa project was de hoofdreden van de Balkan ‘dwarsboom’ politiek waarmee de Triple Entente in 1914 de Eerste Wereld Oorlog provoceerde. Dit grotere geopolitieke perspectief geeft een heel andere duiding aan de in Amerika bedachte ‘Financiële Crisis’ van 2008, die leidde tot de economisch desastreuze en politiek destabiliserende ‘Europese Schuldencrisis’ van 2009, en aan de door Amerika geïnstigeerde ‘Arabische Lente’ van 2011, die leidde tot de Europese ‘Migratie Crisis’ van 2015.

Deze duiding wordt het best verwoordt door Steuckers zelf: La globalisation, c’est... le maintien de l’Europe, et de l’Europe seule, en état de faiblesse structurelle permanente. Et cette faiblesse structurelle est due, à la base, à un déficit éthique entretenu, à un déficit politique et culturel. Il n’y a pas d’éthique collective, de politique viable ou de culture féconde sans ce que Machiavel et les anciens Romains, auxquels le Florentin se référait, appelaient des ‘vertus politiques’, le terme ‘vertu’ n’ayant pas le sens stupidement moraliste qu’il a acquis, mais celui, latin, de ‘force agissante’, de ‘force intérieure agissante’... [De globalisatie betekent dit: ...het gijzelen van Europa - en alleen van Europa - in een staat van permanente [en] structurele zwakte. En die zwakte is in essentie te wijten aan een doorlopend ‘ethisch tekort’ [dat zich vertaalt in] een politiek en cultureel tekortschieten. Een collectieve ethiek, een levensvatbare politiek [en] een vruchtbare cultuur zijn onmogelijk zonder wat Machiavelli, en de oude Romeinen waarop de Florentijn zi[jn denken] baseerde, de ‘politieke deugden’ noemden - waarbij de term ‘deugd’ niet de kortzichtige moralistische lading heeft die hij nu heeft, maar de [oorspronkelijk] Latijnse [betekenis] van ‘acterende kracht’ [en] ‘innerlijk sturende kracht’.] (p. 279-80) Terecht wijst Steuckers op de door globalistische cognitieve oorlogsvoering bewerkstelligde ‘ethisch tekort’ van Europa: het is dit tekort aan politieke deugd, doelbewustheid en daadkracht dat Europa verlamt. Dit tekort maakt psycho-historische catharsis, geopolitieke assertiviteit en decisionistische zelfverdediging onmogelijk: het maakt Europa machteloos tegen de acute existentiële bedreigingen van opzettelijk gestuurde sociale implosie, massa-immigratie en jihadistische terreur. Dit globalistisch ‘anti-European’ Europa verwezenlijkt zich door de verinnerlijking van het cognitieve-dissonante globalistische mainstream media discours van zelfdestructief geïnterpreteerde ‘mensenrechten’, ‘multiculturaliteit’ en ‘diversiteit’. L’arme principale qui est dirigée contre l’Europe est donc un ‘écran moralisateur’, à sens unique, légal et moral, composé d’images positives, de valeurs dites occidentales et d’innocences prétendues menacées, pour justifier des campagnes de violence politique illimitée. [Het voornaamste wapen dat gericht is tegen Europa is een uniek ‘moralistisch [televisie- en beeld]scherm’ dat [specifieke] juridische en morele ‘waarden’ [afdwingt via] het positieve ‘frame’ van zogenaamde ‘westerse waarden’ en gepretendeerde ‘bedreigde onschuld’ voor het goedpraten van een [systematische] campagne van eindeloze politieke terreur.] (p.281)

Deze duiding wordt het best verwoordt door Steuckers zelf: La globalisation, c’est... le maintien de l’Europe, et de l’Europe seule, en état de faiblesse structurelle permanente. Et cette faiblesse structurelle est due, à la base, à un déficit éthique entretenu, à un déficit politique et culturel. Il n’y a pas d’éthique collective, de politique viable ou de culture féconde sans ce que Machiavel et les anciens Romains, auxquels le Florentin se référait, appelaient des ‘vertus politiques’, le terme ‘vertu’ n’ayant pas le sens stupidement moraliste qu’il a acquis, mais celui, latin, de ‘force agissante’, de ‘force intérieure agissante’... [De globalisatie betekent dit: ...het gijzelen van Europa - en alleen van Europa - in een staat van permanente [en] structurele zwakte. En die zwakte is in essentie te wijten aan een doorlopend ‘ethisch tekort’ [dat zich vertaalt in] een politiek en cultureel tekortschieten. Een collectieve ethiek, een levensvatbare politiek [en] een vruchtbare cultuur zijn onmogelijk zonder wat Machiavelli, en de oude Romeinen waarop de Florentijn zi[jn denken] baseerde, de ‘politieke deugden’ noemden - waarbij de term ‘deugd’ niet de kortzichtige moralistische lading heeft die hij nu heeft, maar de [oorspronkelijk] Latijnse [betekenis] van ‘acterende kracht’ [en] ‘innerlijk sturende kracht’.] (p. 279-80) Terecht wijst Steuckers op de door globalistische cognitieve oorlogsvoering bewerkstelligde ‘ethisch tekort’ van Europa: het is dit tekort aan politieke deugd, doelbewustheid en daadkracht dat Europa verlamt. Dit tekort maakt psycho-historische catharsis, geopolitieke assertiviteit en decisionistische zelfverdediging onmogelijk: het maakt Europa machteloos tegen de acute existentiële bedreigingen van opzettelijk gestuurde sociale implosie, massa-immigratie en jihadistische terreur. Dit globalistisch ‘anti-European’ Europa verwezenlijkt zich door de verinnerlijking van het cognitieve-dissonante globalistische mainstream media discours van zelfdestructief geïnterpreteerde ‘mensenrechten’, ‘multiculturaliteit’ en ‘diversiteit’. L’arme principale qui est dirigée contre l’Europe est donc un ‘écran moralisateur’, à sens unique, légal et moral, composé d’images positives, de valeurs dites occidentales et d’innocences prétendues menacées, pour justifier des campagnes de violence politique illimitée. [Het voornaamste wapen dat gericht is tegen Europa is een uniek ‘moralistisch [televisie- en beeld]scherm’ dat [specifieke] juridische en morele ‘waarden’ [afdwingt via] het positieve ‘frame’ van zogenaamde ‘westerse waarden’ en gepretendeerde ‘bedreigde onschuld’ voor het goedpraten van een [systematische] campagne van eindeloze politieke terreur.] (p.281)

In Europa wordt dit globalistische discours exemplarisch geïnternaliseerd en prioritair vertegenwoordigd door de soixante-huitard generatie die zich na haar ‘lange mars door de instituties’ het monopolie op de politieke macht heeft toegeëigend. Pendant les années de leur traversée du désert, ...les [utopistes]de [la] génération soixante-huitard] feront... un ‘compromis historique’ qui repose, ...premièrement, sur un abandon du corpus gauchiste, libertaire et émancipateur, au profit des thèses néolibérales, deuxièmement, sur une instrumentalisation de l’idée freudo-sartienne de la ‘culpabilité’ des peuples européens, responsables de toutes les horreurs commises dans l’histoire, et troisièmement, sur un pari pour toutes les démarches ‘mondialisatrices’, même émanant d’instances capitalistes non légitimées démocratiquement ou d’institution comme la Commission Européenne, championne de la ‘néolibéralisation’ de l’Europe, dont le pouvoir n’est jamais sanctionné par une élection. [Gedurende hun jaren in de woestijn... maakten de [utopisten] van de [‘achtenzestig’] generatie... een ‘historisch compromis’ dat berust... op [drie complementaire strategieën:] (1) een verraad van hun linkse [kern]gedachtegoed [van] bevrijding en emancipatie ten gunste van het neoliberalisme, (2) een [politieke] toepassing van het Freudiaans-Sartriaanse idee van de ‘schuld’ van de Europese volkeren, [die zo] verantwoordelijk [worden gehouden] voor alle misdaden van de geschiedenis en (3) een inzet op ‘globaliserende’ processen - zelfs [als die processen] worden gedreven door [on]democratische [en] illegitieme kapitalistische machten of door institutie[s] als de Europese Commissie, die [zich heeft opgeworpen] als kampioen van de ‘neoliberalisatie’ van Europe en waarvan de macht nog nooit door een verkiezing is goedgekeurd.[20]] (p.293) Dit ideologische verraad en globalistische deze collaboratie, de standaard modaliteiten van de Europese vijandelijke elite, hebben de Europese beschaving aan de rand van de afgrond gebracht.

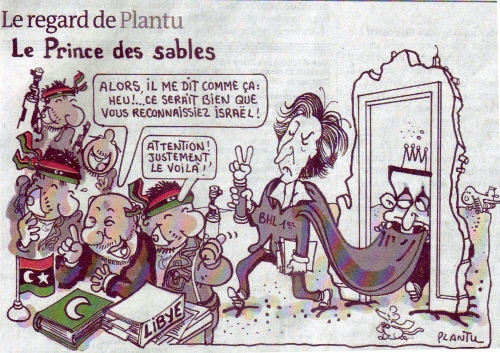

Steuckers wijst op de functionaliteit van het verraad van de Europese soixante-huitards ten aanzien van de globalistische geopolitiek: dit verraad levert Europa over aan het de facto monsterverbond tussen twee essentieel anti-Europese globalistische krachten: het liberaal-normativisme, gesymboliseerd in het Amerikaanse ‘Puritanisme’, en het islamisme, gesymboliseerd in het Saoedische ‘Wahhabisme’. Aujourd’hui, nous faisons face à l’alliance calamiteuse de deux fanatismes religieux : le wahhabisme, visibilisé par les médias, chargé de tous les péchés, et le puritanisme américain, camouflé derrière une façade ‘rationnelle’ et ‘économiste’ et campé comme matrice de la ‘démocratie’ et de toute ‘bonne gouvernance’. Que nous ayons affaire à un fanatisme salafiste ou hanbaliste qui rejette toutes les synthèses fécondes, génératrice et façonneuses d’empires, qu’elles soient byzantino-islamiques ou irano-islamisées ou qu’elles se présentent sous les formes multiples de pouvoir militaire équilibrant dans les pays musulmans, ou que nous ayons affaire à un fanatisme puritain rationalisé qui entend semer le désordre dans tous ces états de la planète, que ces états soient ennemis ou alliés, parce que ces états soumis à subversion ne procèdent pas de la même matrice mentale, nous constatons que toutes nos propres traditions européennes... sont considérées par ces fanatismes contemporains d’au-delà de l’Atlantique ou d’au-delà de la Méditerranée comme émanations du Mal, comme des filons culturels à éradiquer pour retrouver une très hypothétique pureté, incarnée jadis par les pèlerins du ‘Mayflower’ ou par les naturels de l’Arabie du VIIIe siècle. [In het huidige tijdsbestek hebben we te maken met een rampspoedig [globalistisch, anti-Europees] bondgenootschap tussen twee religieuze fanatismes: het Wahhabisme,[21] zoals gevisualiseerd en als ‘zondig’ bestempeld door de [mainstream] media, en het Amerikaanse puritanisme, gecamoufleerd achter een ‘rationele’ en ‘economische’ façade en voorgesteld als vast referentie ‘frame’ voor ‘democratie’ en ‘behoorlijk bestuur’. Of we nu te maken hebben met vormen van ‘Salafistisch’ of ‘Hanbalitisch’ fanatisme[22] dat een punt zet achter de vruchtbare, creatieve en imperium-scheppende byzantijns-islamitische of iraans-islamitische syntheses, of met vormen van puriteins-gerationaliseerd en militair-hegemoniaal fanatisme dat over de hele wereld chaos schept (bij bevriende zowel als vijandelijke staten, want alle aan die hegemonie onderworpen staten vertegenwoordigen andersoortige mentale werelden): wij moeten constateren dat onze eigen Europese tradities... onverenigbaar zijn die fanatismes van de overzijde van de Atlantische Oceaan en Middellandse Zee. Die hedendaagse fanatismes beschouwen [onze tradities] als incarnaties van het [pure] Kwaad [en] als cultuuruitingen die moeten worden bestreden met het - overigens zeer hypothetische - puurheid die wordt belichaamt in de Pilgrim Fathers van de ‘Mayflower’[23] en de bons sauvages[24] van de 8e eeuwse Arabische binnenlanden]. (p. 261-2)

De totalitair-regressieve fanatismes van het ‘Puristisch’ liberaal-normativisme en het ‘Wahhabistisch’ islamisme zullen emotioneel, intellectueel en spiritueel moeten worden overwonnen als de Europese beschaving en de Europese volkeren de Crisis van het Moderne Westen willen overleven. De therapie die op dit kritieke punt vanuit Traditionalistisch oogpunt momenteel de grootste kans van slagen biedt is een politiek-filosofische ‘noodgreep’: de nooduitgang van het Archeo-Futuristisme.

4.

Het Archeo-Futuristisch alternatief

(politiek-filosofische therapie)

Lo, all our pomp of yesterday

Is one with Nineveh and Tyre!

Judge of the Nations, spare us yet.

Lest we forget - lest we forget!

- Rudyard Kipling

Het Archeo-Futuristische alternatief voor het globalistische anti-Europese ‘EU project’ is een gelijktijdig teruggrijpen en vooruitprojecten van een Traditionalistisch concept dat lang een vitale rol heeft gespeeld in de Europese geschiedenis en dat weer kan doen: de Europese Rijksgedachte. Het gaat hierbij om een concept dat strikt genomen boven-historisch is daarom te allen tijde kan herleven. Het ideologisch misbruik en de historiografische misinterpretatie van de Europese Rijksgedachte door het 19e en 20e eeuwse (hyper-)nationalisme - meest recent in het ‘Derde Rijk’ - doet niets af aan de boven-historische vitaliteit ervan. Steuckers wijst in dat verband op het essentieel belang van een juist begrip van het Traditionalistische gedachtegoed waarvan de Rijksgedachte deel uitmaakt. Het Traditionalisme stelt namelijk dat alle collectieve (taalkundige, religieuze, etnische, nationale) identiteiten, en de horizontaal (werelds, fysiek) ervaren verschillen daartussen, organisch onderdeel (kunnen, moeten, zullen) zijn van grotere, synergetisch unieke entiteiten met een hogere verticale, transcendent (spiritueel, psychologisch) ervaren, functionaliteit. Deze entiteit kan worden betiteld als Imperium, ofwel ‘Rijk’ - in het Avondland als het ‘Europese Rijk’. Het numineuze karakter ervan is onmiddellijk aantoonbaar in het feit dat het ontzag inspireert in degenen die er zich op natuurlijke wijze deel van voelen - en dat het angst inspireert in degenen die het onwaardig zijn.

Pour résumer brièvement la position traditional[iste],... disons que les horizontalités modernes ne permettent pas le respect de l’Autre, de l’être-autre. Si l’Autre est jugé dérangeant, inopportun dans son altérité, il peut être purement et simplement éliminé ou mis au pas, sans le moindre respect de son altérité, car l’horizontalité fait de tous des ‘riens ontologiques’, privés de valeur intrinsèque. Tel est l’aboutissement de la logique égalitaire, propre des idéologies et des systèmes qui ont voulu usurper et éradiquer la tradition ‘reichique’ : si tout vaut tout dans l’intériorité de l’homme, ou même dans sa constitution physique, cela signifie, finalement, que plus rien n’a de valeur spécifique, et si une valeur spécifique cherche à pointer envers et contre tout, elle sera vite considérée comme une anomalie qui appelle l’extermination. L’intervention fanatique et sanglante de ‘colonnes infernales’. La verticalité, en revanche, implique le devoir de protection et de respect, un devoir de servir les supérieurs et un devoir des supérieurs de protéger les inférieurs, dans un rapport comparable à celui qui existe, dans les sociétés et les familles traditionnelles, entre parents et enfants. La verticalité respecte les différences ontologiques et culturelles ; elle ne les considère pas comme des ‘riens’ qui ne méritent ni considération ni respect. [Om het tradition[alistische] standpunt samen te vatten... kan men stellen dat de modern[istische] horizontaliteit een [waarachtig] respect van de Ander en het anders-zijn onmogelijk maakt. Wanneer de Ander in zijn anders-zijn [slechts] als storend [en] inopportuun wordt beoordeeld, dan kan hij simpelweg worden geëlimineerd of worden weggezet zonder het minste respect voor zijn anders-zijn: de [modernistische] horizontaliteit reduceert immers alle [vormen van authentieke] identiteit tot een ‘ontologisch nulwaarde’ zonder intrinsieke waarde. Dat is het [onvermijdelijke] eindresultaat van de egalitaire logica die ligt achter de ideologieën en systemen die de rijkstraditie willen vervangen en uitwissen. Als alles alleen maar afhangt van het innerlijk van de mens, of zelfs alleen maar van zijn fysieke constitutie, dan blijft er uiteindelijk niets van specifieke waarde over. Wanneer een specifieke waarde in de tegenovergestelde [niet-egalitaire] richting wijst tegen het [‘algemene belang’ in], dan wordt zij al snel gezien als een ‘afwijking’ die moet worden geëlimineerd. Dit [resulteert] in de fanatieke en bloedige interventie van de ‘helse colonnes’[25] [van het modernistische collectivisme]. Daartegenover staat de [Traditionalistische] verticaliteit die uitgaat van de verplichting tot bescherming van en respect voor [de Ander]. [Dat is] de verplichting [van lager gestelden] om hoger gestelden te dienen en de verplichting van hoger gestelden om lager gestelden te beschermen in een verhouding die vergeleken kan worden met die tussen ouders en kinderen in traditionele gemeenschappen en families. Deze verticaliteit respecteert ontologische verschillen en de culturele [uitdrukkingen daarvan]: zij reduceert ze niet tot ‘[ontologische] nulwaarden’ die geen consideratie en respect verdienen.] (p. 157)

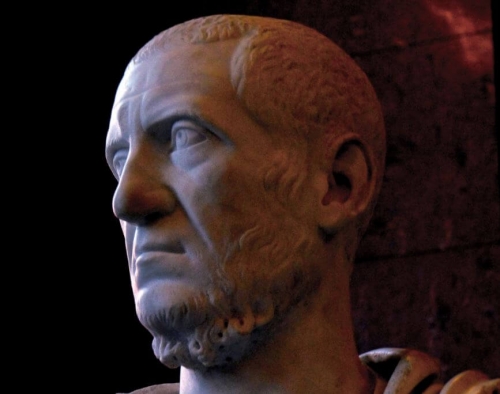

De Traditionalistische Rijksgedachte behelst dus een holistische visie waarin alle collectieve en individuele [authentieke] identiteiten op organische wijze worden ingepast in een groter geheel van synergetische meerwaarde. Il faut enfin... que chaque communauté et chaque individu aient conscience qu’ils gagnent à demeurer dans l’ensemble impéria[ux]au lieu de vivre séparément. Tâche éminemment difficile qui souligne la fragilité des édifices impériaux : Rome a su maintenir un tel équilibre pendant les siècles, d’où la nostalgie de cet ordre jusqu’à nos jours. ...[L]a civitas de l’origine... de l’Urbs, la Ville initiale de l’histoire impériale, ...s’est étendue à l’Orbis romanus. Le citoyen romain dans l’empire signale son appartenance à cet Orbis, tout en conservant sa natio et sa patria, appartenance à telle nation ou telle ville de l’ensemble constitué par l’Orbis. [Het is uiteindelijk noodzakelijk... dat elke gemeenschap en ieder individu zich ervan bewust zijn dat zij er meer bij gebaat zijn vast te houden aan het imperiale geheel dan afzonderlijk te leven. [Dit is] een zeer ingewikkelde opgave die de kwetsbaarheid van [alle] imperiale projecten onderstreept: Rome wist eeuwenlang een dergelijke balans te handhaven - vandaar de nostalgie naar de [Romeinse] orde die voortduurt tot op de dag van vandaag. ...[D]e originele civitas... van de Urbs waaruit [men] stamt, [dat wil zeggen] de Stad vanwaaruit de imperiale geschiedenis zich ontplooide... breidde zich [met het Romeinse rijk] uit tot een Orbis romanus. Onder het [Romeinse] keizerrijk duidde het Romeins burgerschap op een identificatie met die Orbis, met behoud van de eigen natio en het eigen patria, [dat wil zeggen] met een [blijvend] toebehoren aan een bepaalde natie of vaderland binnen het geheel van die Orbis.] (p.129-31) D’abord, il faut préciser que le ‘Reich’ n’est pas une nation, même s’il est porté, en théorie, par un populus (le populus romanus) ou une ‘nation’ (la deutsche Nation) : ...[c’est] n’est pas [une chose] nationaliste, [c’est] même [une chose] anti-nationaliste. [I]l n’a rien contre les sentiments d’appartenance nationale, contre la fierté d’appartenir à une nation. De tels sentiments sont positifs... mais doivent être transcendés par une idée. Cette transcendance conduit à une verticalité, qui oppose à toutes les formes modernes d’horizontalité, ce qui est, par ailleurs, le noyau idéel, de toutes les traditions... [Vooraf moet worden vastgesteld dat een ‘Rijk’ geen natie is, zelfs als het in theorie door een populus ([een ‘volk’ zoals] het populus romanus) of door een natie ([een natie zoals] de deutsche Nation) wordt gedragen: ...[het Rijk] is niet nationalistisch, [het is] zelfs anti-nationalistisch. [H]et heeft niets tegen het identiteit bepalende [collectieve] nationalistisch sentiment [of] tegen de [individuele] trots op het behoren tot een natie. Zulke sentimenten zijn positief... maar dienen te worden overstegen door het [nog hogere imperiale] idee. Deze transcendentie leidt tot een verticaliteit die zich afzet tegen alle moderne vormen van horizontaliteit - deze [verticaliteit] is uiteindelijk de ideële kern van alle [authentieke T]radities.] (p. 156-7)

Het praktische samengaan van collectieve en individuele identiteiten wordt gerealiseerd in de politieke toepassing van het Traditionalistische beginsel van subsidiariteit (een laatste spoor daarvan is in de Nederlandse Traditie terug te vinden in het anti-revolutionaire principe van ‘soevereiniteit in eigen kring’). ...[L]e principe de ‘subsidiarité’, tant évoqué dans l’Europe actuelle mais si peu mis en pratique, renoue avec un respect impérial des entités locales, des spécificités multiples que recèle le monde vaste et diversifié. [...Het beginsel van ‘subsidiariteit’, waaraan men vaak refereert in het hedendaagse Europe maar dat men zelden in de praktijk brengt, kan [nieuw] imperiaal [ondersteund] respect geven aan de lokale gemeenschappen [en] specifieke identiteiten die horen bij de echte wereld van enorme [authentiek-gewortelde] diversiteit.] (p. 139)

In relatie tot de Rijksgedachte zijn ‘identiteitspolitiek’, ‘multiculturaliteit’ en ‘diversiteit’ non-issues: ze worden organisch ‘opgelost’ door sublimatie in de hogere functionaliteit van het Rijk. L’empire est donc fait de multiplicités, de différences, qui n’ont rien de commun avec la fausse multiculturalité vantée par les médias d’aujourd’hui. Cette multiculturalité, escroquerie idéologique, relève justement de cette horizontalité qui vise à vider tous les hommes, autochtones et allochtones, de leur substance ontologique. Cette multiculturalité tue l’essentiel qui vit en l’homme. Toute politique qui cherche à la promouvoir est une politique criminelle, exterministe... [Een Rijk behelst dus [altijd complexe] meervoudigheden [en] diversiteiten die niets gemeen hebben met de valse ‘multiculturaliteit’ die wordt aangeprezen door de [mainstream] media van vandaag. Deze [namaak-] multiculturaliteit is een ideologisch bedrog dat voortvloeit uit de [modernistische] horizontaliteit die bedoeld is om alle mensen - autochtoon zowel als allochtoon - the ontdoen van hun ontologische substantie. Deze multiculturaliteit doodt de essentie die leeft in de mens. Alle politiek die haar wil bevorderen is een criminele - en etnocidale - politiek...] (p.158) Het is een ironisch feit dat de Traditionalistische Rijksgedachte en Rijksgemeenschap effectief veel meer tolerantie en vrijheid bieden dan de modernistische ‘diversiteit’ en ‘democratie’ dat ooit zouden kunnen.

5.

Sacrum Imperium

(neo-imperiale therapie)

Hier die Manen hehrer Krieger

Seien euch ein Musterbild

Führen euch vom Kampf als Sieger

- Joseph Hartmann Stuntz[26]

De Westerse beschaving is gebaseerd op een kwetsbare balans tussen elkaar aanvullende authentieke identiteiten die samen synergische meerwaarde krijgen via historische interacties. Deze meerwaarde kan worden uitgedrukt in de ‘hyper-boreale’ archetypen van Techne (technische bevrijding), Nomos (juridische bevrijding) en Evangelion (spirituele bevrijding).[27] Maar deze meerwaarde en de beschaving waarop zij is gebaseerd vergen constante bescherming en bewaking - dit is de basis van de Traditionalistisch Europese Rijksgedachte. En Europe, les structures de type impérial sont... une nécessité, afin de maintenir la cohérence de l’aire civilisationnelle européenne, dont la culture a jailli du sol européen, afin que tous les peuples au sein de cette aire civilisationnelle, organisée selon les principes impériaux, puissent avoir un avenir. [In Europa zijn structuren van het imperiale type... onontbeerlijk om de cohesie te beschermen van de Europese beschavingssfeer die is ontsproten aan de Europese grond - en om aan de binnen die beschavingssfeer inheemse volkeren een toekomst[perspectief] te bieden door een haar te [re]organiseren volgens imperiale principes.] (p. 214) Een dubbel idealistische en realistische - Archeo-Futuristische - heroverweging van de Rijksgedachte is van essentieel belang ter bescherming van de Europese volkeren en van hun gezamenlijke beschaving. De uitbreiding van de Europese Rijksgedachte tot de overzeese Europees-stammige volkeren is daarbij een logische volgende stap: deze stap is reeds Archeo-Futuristisch uitgewerkt in het concept van de ‘Boreale Alliantie’. Op globale schaal zou een dergelijke alliantie natuurlijke bondgenoten vinden in de twee andere Indo-Europese Rijksgedachten: de Perzische en Indische: een Archeo-Futuristische exploratie van dit thema is te vinden in Jason Jorjani’s concept van de World State of Emergency. De alternatieve geopolitiek die past bij deze Archeo-Futuristische heroverwegingen wordt al concreet onderzocht in de anti-globalistische Neo-Eurazianistische beweging.[28]

Het is de taak van het Traditionalisme om de gezamenlijke ‘Hogere Roeping’ van de Europese volkeren in herinnering te brengen wanneer deze bedreigd wordt.[29] Steuckers voldoet hieraan door de Traditionalistische visie van Europa eenduidig te neer te zetten: L’Europe, c’est une perception de la nature comme épiphanie du divin... L’Europe, c’est également une mystique du devenir et de l’action... L’Europe, c’est une vision du cosmos où l’on constate l’inégalité factuelle de ce qui est égal en dignité ainsi qu’une pluralité de centres... [C’est] une nouvelle vision de l’homme, impliquant la responsabilité pour l’autre, pour l’écosystème, parce que, ... sur [c]es bases philosophiques, ...l’homme... est un collaborateur de Dieu et un miles imperii, un soldat de l’empire. Le travail n’est plus malédiction ou aliénation mais bénédiction et octroi d’un surplus de sens au monde. La technique est service à l’homme, à autrui... La construction de l’Europe... nécessite de revitaliser une ‘citoyenneté d’action’, où l’on retrouve la notion de l’homme coauteur de la création divine et l’idée de responsabilité. [Het [Traditionalistisch] ‘Europa’ is een visioen waarin de natuurlijke wereld als Goddelijke Epifanie geldt... [Dit] Europa is een mysterie in wording en werking... [Dit] Europa is een kosmisch visioen dat de feitelijke ongelijkheid erkent van alles dat gelijk is in waardigheid en daarmee ook van [cultuurhistorische en geopolitieke] multipolariteit... [Dit] nieuwe visioen van mens-zijn impliceert verantwoordelijkheid voor [alles dat] anders [en] voor het [hele natuurlijke en menselijke] ecosysteem omdat... op de filosofische basis [van dit visioen]... de mens een medewerker is van God - een miles imperii, een soldaat van het [goddelijk ingestelde] Rijk. Hier is werk niet langer vloek of vervreemding,[30] maar een zegen en een octrooi voor [een hoger] verantwoordelijkheidsbesef voor de [hele schepping]. [Hierbij] staat de techniek ten dienste van de mens - [en] van de ander...[31] De constructie van Europa... vereist een herleven van ‘activistisch burgerschap’ waarin men het idee terugvindt van de mens als medewerker aan de Goddelijke Schepping - en het idee van [zijn uit zijn authentieke identiteit voortvloeiende kosmische] verantwoordelijkheid.] (p. 138-9) Het is duidelijk dat de Hogere Roeping van de Europese volkeren niet stopt aan de geografische grenzen van het Europese subcontinent: zij geldt ook voor de Europees-stammige volkeren die zich over deze grenzen heen hebben begeven en zich overzees hebben gevestigd in boreale en australe regionen.

Het is de taak van het Traditionalisme om de gezamenlijke ‘Hogere Roeping’ van de Europese volkeren in herinnering te brengen wanneer deze bedreigd wordt.[29] Steuckers voldoet hieraan door de Traditionalistische visie van Europa eenduidig te neer te zetten: L’Europe, c’est une perception de la nature comme épiphanie du divin... L’Europe, c’est également une mystique du devenir et de l’action... L’Europe, c’est une vision du cosmos où l’on constate l’inégalité factuelle de ce qui est égal en dignité ainsi qu’une pluralité de centres... [C’est] une nouvelle vision de l’homme, impliquant la responsabilité pour l’autre, pour l’écosystème, parce que, ... sur [c]es bases philosophiques, ...l’homme... est un collaborateur de Dieu et un miles imperii, un soldat de l’empire. Le travail n’est plus malédiction ou aliénation mais bénédiction et octroi d’un surplus de sens au monde. La technique est service à l’homme, à autrui... La construction de l’Europe... nécessite de revitaliser une ‘citoyenneté d’action’, où l’on retrouve la notion de l’homme coauteur de la création divine et l’idée de responsabilité. [Het [Traditionalistisch] ‘Europa’ is een visioen waarin de natuurlijke wereld als Goddelijke Epifanie geldt... [Dit] Europa is een mysterie in wording en werking... [Dit] Europa is een kosmisch visioen dat de feitelijke ongelijkheid erkent van alles dat gelijk is in waardigheid en daarmee ook van [cultuurhistorische en geopolitieke] multipolariteit... [Dit] nieuwe visioen van mens-zijn impliceert verantwoordelijkheid voor [alles dat] anders [en] voor het [hele natuurlijke en menselijke] ecosysteem omdat... op de filosofische basis [van dit visioen]... de mens een medewerker is van God - een miles imperii, een soldaat van het [goddelijk ingestelde] Rijk. Hier is werk niet langer vloek of vervreemding,[30] maar een zegen en een octrooi voor [een hoger] verantwoordelijkheidsbesef voor de [hele schepping]. [Hierbij] staat de techniek ten dienste van de mens - [en] van de ander...[31] De constructie van Europa... vereist een herleven van ‘activistisch burgerschap’ waarin men het idee terugvindt van de mens als medewerker aan de Goddelijke Schepping - en het idee van [zijn uit zijn authentieke identiteit voortvloeiende kosmische] verantwoordelijkheid.] (p. 138-9) Het is duidelijk dat de Hogere Roeping van de Europese volkeren niet stopt aan de geografische grenzen van het Europese subcontinent: zij geldt ook voor de Europees-stammige volkeren die zich over deze grenzen heen hebben begeven en zich overzees hebben gevestigd in boreale en australe regionen.

Naar binnen toe vereist dit visioen een individuele zelfdiscipline, een individuele arbeidsethos en een individuele acceptatie van hiërarchische orde - en dus een omkering van de narcistische, hedonistische en collectivistische levenshouding die wordt bevorderd en bestendigd in het liberaal-normativisme dat nu dominant is in het postmoderne Westen. Dit betekent een overgang naar een nieuwe existentiële realiteit die wordt beheerst door authentieke normen en waarden - en door een legitieme Autoriteit. In de Europese Traditie draagt die Autoriteit, in navolging van zijn Romeinse archetype, de titel ‘keizer’.[32] Dans la conception [traditionaliste] hiérarchique des êtres et des fins terrestres... l’empire constituait le sommet, l’exemple impassable pour tous les autres ordres inférieurs de la nature. De même, l’empereur, également au sommet de cette hiérarchie par la vertu de sa titulaire, doit être un exemple pour tours les princes du monde, non pas en vertu de son hérédité, mais de supériorité intellectuelle, de son connaissance ou des ses connaissances. Les vertus impériales sont justice, vérité, miséricorde et constance... [In de [Traditionalistische] hiërarchische opvatting van wereldse wezens en wensen... vertegenwoordigt het Rijk het hoogste doel, het onevenaarbare voorbeeld voor alle lagere natuurlijke ordeningen. Dit betekent dat de keizer, die op grond van zijn titel aan de top van deze hiërarchie staat, een voorbeeld stelt voor alle [overige] prinsen van de wereld - niet op grond van zijn afstamming, maar [op grond] van zijn intellectuele superioriteit en van zijn kundigheid en inzichten. [In hem worden de] imperiale [‘politieke] deugden’ van rechtvaardigheid, waarheid, mededogen en standvastigheid verwezenlijkt]. (p. 136) Vanzelfsprekend is een als zodanig herkenbare legitieme Autoriteit bijna onvoorstelbaar in de huidige Europese context, maar toch is dit ideaalbeeld van deze Autoriteit onontbeerlijk als vast referentiepunt. Ditzelfde geldt tot op zekere hoogte voor de Rijksgedachte zelf: in het huidige politiek-filosofisch discours is deze gedachte eerst en vooral een experiment waarmee een bestemming en een koers kunnen worden bepaald voor de patriottisch-identitaire beweging. Op dezelfde manier dat het ‘Koninkrijk der Hemelen’ als referentiepunt dient voor de Hogere Roeping van het Christendom, zo dient de Europese Rijksgedachte als referentiepunt voor de Europese beschaving – ook als het ideaal nog niet is verwezenlijkt in het hier en nu. De oude Traditionalistische Rijksgedachte dient hierbij als voorbeeld voor een nieuwe Archeo-Futuristische Rijksgedachte. De hiërarchische politieke filosofie van het Neo-Eurazianisme kan ook hierbij een brugfunctie vervullen.