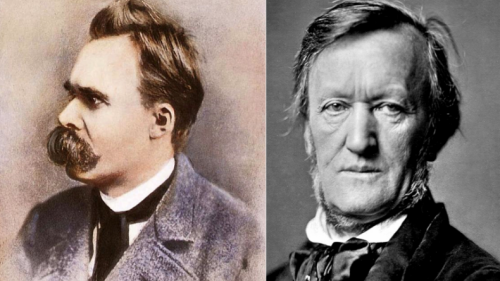

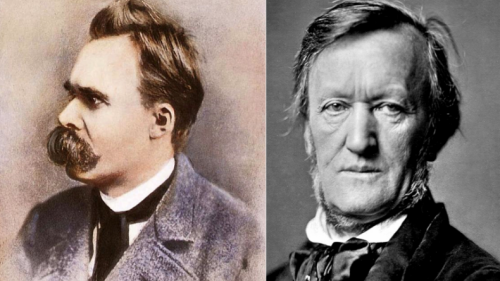

Wagner, Nietzsche and the Birth of Music – from the Spirit of Tragedy

Alexander Jacob

Ex: https://manticorepress.net

One of the great misfortunes of modern aesthetic theory is the fact that, ever since Nietzsche introduced the concepts of ‘Dionysian’ music and ‘Apollonian’ art in his popular essay Die Geburt der Tragödie aus dem Geiste der Musik (The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music) (1872), it has become customary among scholars and critics to consider these as quasi-normative elements of tragic drama. We may recall that Nietzsche, following Schopenhauer’s dictum that ideas are the universalia post rem;[1] music, however, gives the universalia ante rem,[2] and reality the universalia in re,[3] contended that the primordial music that is universal in expression is to be identified as ‘Dionysian’ while all artistic and dramatic representations of this universal music were merely ‘Apollonian’ forms of individuation, or of merely illusory phenomena:

through Dionysian music the individual phenomenon becomes richer and widens into a world-picture. It was a powerful victory of the non-Dionysian spirit when, in the development of the newer dithyramb, it alienated music from itself and forced it down to be the slave of appearances.[4]

But Nietzsche’s conclusion is in fact a false one, for it is only through Apollonian art that the universal can be appreciated. And the value of the latter for man is not through an insensate immersion into the realm of the Unconscious but rather through a Supra-Conscious apprehension of man’s first Fall from God and a desire to be reintegrated into the divine – as Schopenhauer himself had revealed in his discussion of tragedy in his masterwork Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung (The World as Will and Imagination) (1818/59). Indeed, Schopenhauer’s theory of tragedy is, of all the philosophical theories of tragedy that have been propounded since antiquity, the one perhaps closest to the truth – which is hardly surprising considering the ‘pessimistic’ cast of his entire philosophical system. Schopenhauer’s view of the phenomenal world as the expression of a conflict-ridden Will to Life led him to consider tragedy as

the summit of poetical art, both on account of the greatness of its effect and the difficulty of its achievement. It is very significant for our whole system, and well worthy of observation, that the end of this highest poetical achievement is the representation of the terrible side of life. The unspeakable pain, the wail of humanity, the triumph of evil, the scornful mastery of chance, and the irretrievable fall of the just and innocent, is here presented to us; and in this lies a significant hint of the nature of the world and of existence.[5]

Therefore he concluded that

The true sense of tragedy is the deeper insight that it is not his own individual sins that the hero atones for, but original sin, the crime of existence itself.

The fall that is evoked in every tragic representation is, thus, also not a fall into morality, as the Hebrew reference to the ‘knowledge of good and evil’ in Genesis 3, and Nietzsche’s entire moral philosophy following it, would have us believe, but rather the original Fall (or ‘castration’) of the primordial macroanthrophomorphic form of Ouranos called Purusha (among the Indians) or Adam Kadmon (among the Hebrews) that generated the physical cosmos.[6]

Nietzsche indeed does not seem to be aware of the original significance of the Greek gods Dionysus and Apollo, nor of their relation to the representations of tragic drama. The essential cosmic role of Dionysus is that of the solar force of Ouranos/Helios that descends into the underworld to be revived in our universe as the sun, Apollo. This descent is among the ancient Indo-Europeans understood as a ‘castration’ of the phallus of Ouranos by Time/Chronos that is remedied by the force of Chronos’ representative in the nascent universe, Zeus, or Dionysus.[7] The solar force that Dionysus represents in the underworld is naturally rather uncontrolled in its enormous energy and is therefore represented in the Dionysian cult by the wild abandon typical of Bacchanalian rites. The aim of these rites however, as in all Indo-European religions, would have been a serious soteriological one rather than a frivolous, as in Nietzsche’s account. The followers of Dionysus were ‘enthusiasts’, ‘filled with the god’, and imitated in their ritual worship the cosmic progress of the god.

It is true that the Dionysian mysteries, much like the Indian Tantric ones, are not imbued with a sense of ‘sin’, but they are nevertheless focussed on the need to transfigure human passions into divine ones – even if it be through indulgence. The Dionysian satyr-plays are therefore a hedonistic, quasi-Tantric counterpart of the higher sacerdotal sacrifices among the Indo-Europeans, and especially of such sacrifices as the Agnicayana of the Indian brāhmans which seeks to restore the divine phallus of the castrated, or ‘fallen’ Purusha to its original cosmic force.[8]

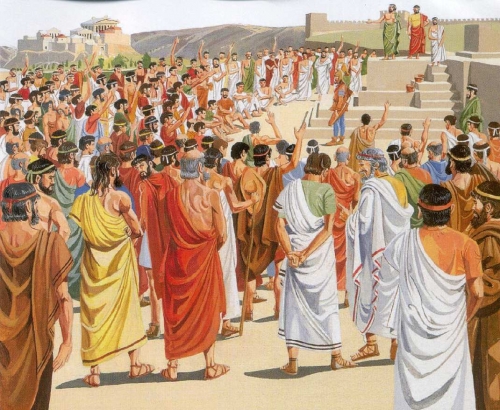

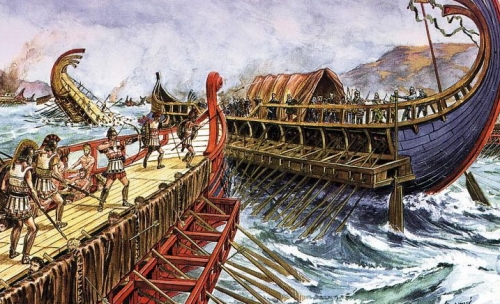

However, it must be noted that these orgiastic celebrations of the energy that the solar force contains in the underworld did not in themselves constitute ‘tragedies’ in any form. Their ritual repesentations merely served, historically, as the source of dramatisations of tragic stories in Greece. For we know from Aristotle’s Poetics 1449ª that tragedy gradually evolved from the spoken prelude to the Dionysian dithyrambs. The dithyramb is a choral hymn sung and danced to Dionysus in a particularly ecstatic manner. It was comprised of male choruses (perhaps dressed as satyrs) that included men and boys.

Later, in the 6th c. B.C., when the dithyrambic prelude had developed in its scope, Thespis took the part of a character and Phrynicus introduced dialogues. Bacchylides’ surviving fragment of a dithyramb (from the 5th c. B.C.) is in the form of a dialogue between a solo singer and a chorus. Thus there arose responsorial dialogues between solo singers and a choir. Aeschylus in the 5th c. B.C. introduced a second actor too into the play. The chorus in a dithyramb sang narrations of actions, unlike the direct speeches of actors in a drama.[9]

Tragedy emerged in this way as a distinct artistic form mainly in ancient Greece. We know that Sanskrit dramas in India did not include tragedies. According to the 10th century treatise on drama called Dasharūpa by Dhanika, Bk.III, for instance, actions not suited for representation on the stage include murder, fights, revolts, eating, bathing, intercourse, etc. The death of a hero too can never be represented. If tragedy is not favoured by the ancient Indian drama, it is not attested in the ancient Near East either, though liturgical laments were composed at the end of the Third Dynasty of Ur (ca.2000 B.C.) marking the losses of the temples of the major Sumerian cities. In Egypt, from the 12th dynasty of the Middle Kingdom (ca.1990 B.C.), there is evidence of dramatic representations of religious subjects in temples. Of these, the murder of Osiris by Seth, his dismemberment, and resuscitation may be considered the Egyptian counterpart of the Dionysian mysteries.

It is important to note that Greek tragic drama, which relied on solo speeches and choral commentaries on the action, did not include much action and certainly no violent action, which was considered too horrific to be enacted onstage and needed a Messenger to describe it to the actors. The dramatic action of a tragedy does not therefore rely on action itself, and often even shuns it. The drama unfolds only through the medium of the speeches of the various characters and choruses. That is why the power of Euripides’ monodic declamations detailing the actions as well as the reactions of the protagonists must be acknowledged as the acme of Greek tragedy rather than its nadir, as Nietzsche considered it. In Euripides (5th c. B.C.) the action was focussed on the feelings generated by the dramatic action, and even the choral commentaries receded in importance before the actor’s monody, a style of dramatic declamation that was perfected by the Roman Stoic philosopher and dramatist Seneca the Younger (1st c. A.D.), who relied mainly on Euripides’ example in the creation of his tragedies.

The cause of this misunderstanding of Euripidean tragedy may be traced back to Richard Wagner’s analyses of Greek drama in his Oper und Drama (Opera and Drama) (1851), Bk.III, Ch.3:[10]

The cause of this misunderstanding of Euripidean tragedy may be traced back to Richard Wagner’s analyses of Greek drama in his Oper und Drama (Opera and Drama) (1851), Bk.III, Ch.3:[10]

In didactic uprightness, which was at the same time artistic dishonesty, lies the cause of the rapid decline of Greek tragedy, in which the people soon perceived that there was no intention of influencing their instinctive feeling, but merely their absolute understanding. Euripides had to suffer under the scourge of the taunts of Aristophanes for his outright disclosure of this falsehood. The fact that poetic art, by dint of adopting a more and more didactic aim, should first pass into political rhetoric, and at last become literary prose was, although an extreme consequence, the one to be naturally expected from the evolution of the intellectual out of the emotional; or, as applied to art, from the evolution of speech from melody.

Nietzsche too rails against Euripides in The Birth of Tragedy, which was in fact a paean to the music-drama of Richard Wagner. He considers Euripides a ‘democratic’ artist who propagated ‘middle-class mediocrity’ by representing tragic protagonists as ordinary rather than superheroic figures. But, as Schopenhauer had already clarified in his discussion of tragedy, it is the imperfection of human nature itself that informs the highest tragedies:

the [tragic] misfortune may be brought about by the mere position of the dramatis personæ with regard to each other, through their relations; so that there is no need either for a tremendous error or an unheard-of accident, nor yet for a character whose wickedness reaches the limits of human possibility; but characters of ordinary morality, under circumstances such as often occur, are so situated with regard to each other that their position compels them, knowingly and with their eyes open, to do each other the greatest injury, without any one of them being entirely in the wrong. This last kind of tragedy seems to me far to surpass the other two, for it shows us the greatest misfortune, not as an exception, not as something occasioned by rare circumstances or monstrous characters, but as arising easily and of itself out of the actions and characters of men, indeed almost as essential to them, and thus brings it terribly near to us. In the other two kinds we may look on the prodigious fate and the horrible wickedness as terrible powers which certainly threaten us, but only from afar, which we may very well escape without taking refuge in renunciation. But in the last kind of tragedy we see that those powers which destroy happiness and life are such that their path to us also is open at every moment; we see the greatest sufferings brought about by entanglements that our fate might also partake of, and through actions that perhaps we also are capable of performing, and so could not complain of injustice; then shuddering we feel ourselves already in the midst of hell.[11]

Although the tragic condition of man is common to every individual human being, Schopenhauer’s discussion suggests that it is only noble men whose lives are truly tragic:

Thus we see in tragedies the noblest men, after long conflict and suffering, at last renounce the ends they have so keenly followed, and all the pleasures of life for ever, or else freely and joyfully surrender life itself … they all die purified by suffering, i.e., after the will to live which was formerly in them is dead.

Nietzsche’s sustained attack on Euripidean tragedy also does not seem to have rightly understood Aristophanes’ criticism of Euripides in his play The Frogs, since Aristophanes’ denunciation of the ‘effeminate’ and ‘democratic’ style of Euripides was indeed directed at a Dionysian form of drama that contrasted with the stark ‘manly’ art of Aeschylus. The erotic aspects of Euripides’ drama were regarded by Aristophanes as a manifestation of the unbridled licentiousness of Dionysiac rituals, which exploited the androgynous character of Dionysus himself. In other words, Nietzsche’s criticism of Euripidean tragedy is in direct opposition to his admiration of what he believed to be the ‘Dionysian’ aspects of the earliest dramatic representations.

In his attack on Euripides for his ‘demotion’ of the Greek chorus below the individual speeches of the characters of the drama Nietzsche further identifies Dionysian music with the Unconscious, or the ‘dream-world’:

This demotion in the position of the chorus …. is the first step towards the destruction of the chorus, whose phases in Euripides, Agathon and the New Comedy followed with breakneck speed one after the other. Optimistic dialectic, with its syllogistic whip, drove music out of tragedy, that is, it destroyed the essence of tragedy, which can be interpreted only as a manifestation and imaginary presentation of Dionysian states, as a perceptible symbolising of music, as the dream-world of a Dionysian intoxication…

In fact there is no indication that drunken intoxication – representing Dionysian inspiration – was the basis of tragic drama even though it may have formed part of the original ritual celebrations of the God from which dithyrambic drama arose.

Nietzsche considers Dionysian music as universal, and Apollonian art, pantomime, drama or opera, as individual, and expressive of the individual lives of the tragic personae:

In fact the relationship between music and drama is fundamentally the reverse [of the Apollonian] – the music is the essential idea of the word, and the drama is only a reflection of this idea, its isolated silhouette.

After this Apollonian presentation of the delusory ‘action’ of the drama, the Dionysian realm reasserts itself:

In the total action of the tragedy the Dionysian regains its superiority once more. Tragedy ends with a tone which never could resound from the realm of Apollonian art.

Nietzsche illustrates this section of his argument with the example of the music of Wagner’s Tristan, his fascination with which was clearly the ímpetus to the writing of The Birth of Tragedy.[12]

Primordial music is falsely interpreted by Nietzsche as being essentially rapturous, or ‘Dionysian’, and best expressed by instrumental, or ‘absolute’, music and then by choral song. Nietzsche is fundamentally averse to dramatic music – which is rather contradictory in one who claimed to be discussing the ‘birth of tragedy’. Indeed, tragedy did not arise from any Dionysian spirit of music, but rather tragic drama arose from the soteriological impulses of the Dionysiac mysteries. And tragic dramatic, or operatic, music itself arose from the sentiments incorporated within the texts of dramatic poems.

Nietzsche’s denunciation of critics too as being excessively intellectual and moralistic (‘Socratic’) and opposed to the authentically ‘aesthetic’ listener dodges the central issue of tragedy – that it is always a reminder of the imperfection of the tragic hero as well as of the viewer. This understanding is obtained through an ethical evaluation of the condition of human life in general, and not from an aesthetic judgement of the pleasure afforded to the ears or eyes by the spectacle on stage.

*

We should note here that Wagner’s conception of the genesis of the earliest forms of drama and music is rather more subtle than Nietzsche’s. We observe in Wagner’s writings that he identifies melody and music as the primal expression of what he calls ‘Feeling’, and words are said to have been later superimposed on these tunes in dramatic lyrics that gradually became increasingly intellectual and didactic in tone to the detriment of the expression of Feeling itself. In his Oper und Drama, Part III, Wagner detailed the manner in which the lyric developed from dance forms that impelled melodic creation:

We know, now, that the endless variety of Greek metre was produced by the inseparable and living co-operation of dance-gesture with articulate speech. (Ch.1)

And again,

The most remarkable feature of ancient lyric consists in its words and verse proceeding from tone and melody: like gestures of the body which became gradually shortened into the more measured and certain gestures of mimicry after having been, as movements of the dance, of merely general indication and only intelligible after many repetitions. (Ch.3)

Wagner understands the earliest representations of dramatic action too as those contained in folk-dances, as he declared in his essay, ‘La musique de l’avenir’ (1860):[13]

That ideal form of dance is in truth the dramatic action. It really bears precisely the same relation to the primitive dance as the symphony to the simple dance-tune. Even the primal folk-dance already expresses an action, for the most part the mutual wooing of a pair of lovers: this simple story – purely physical in its bearings – when ripened to an exposition of the inmost motives of the soul, becomes nothing other than the dramatic action.

However, the gradual intellectualisation of dramatic representation led to the decay of the emotional integrity of melodic invention:

The more the faculty of instinctive emotion became compressed into that of the arbitrary understanding and the more lyrical contents became accordingly changed from emotional to intellectual … the more evident became the removal from the literary poem of its original consistency with primitive articulate melody, which it now only continued to use, so to speak, as a mode of delivery and merely for the purpose of rendering its more callous, didactical contents as acceptable to the ancients habits of feeling as possible. (Ibid.)

While dance music was of principal importance in Greek drama, Wagner thinks that Christianity in particular sharply divorced soul from body and consequently killed the body of music (Oper und Drama, I, Ch.7). The Christian Church deprived music of its choreographic core so that music was forced to develop instead as harmony and counterpoint. In Italy, however, the Renaissance’s discovery of the operatic form of drama gave rise to an uncontrolled proliferation of melodic invention:

The downfall of this art in Italy and the contemporaneous rise of opera-melody among the Italians I can call nothing but a relapse into paganism.

Development of rhythmic melody upon the base of the other mediaeval Christian iinvention, harmony, occurred only in Germany, as notably in the works of Bach. The orchestra continued processes of polyphony that operatic song denied to the latter, for the orchestra in the opera was only a rhythmic harmonic accompaniment to song.

Wagner however does criticise even the chorales of the Reformation as lacking in rhythm, since they are dance music deprived of rhythm by ecclesiastical convention. Nietzsche, on the other hand, in his exaggerated Teutonism, confusedly identifies the choral music of the Reformation with the musical atmosphere of the Dionysiac rituals. He declares that the choral music of the Reformation recovered the

glorious, innerly healthy and age-old power which naturally only begins to stir into powerful motion at tremendous moments … Out of this abyss the German Reformation arose. In its choral music there rang out for the first time the future style of German music. Luther’s choral works sounded as profound, courageous, spiritual, as exuberantly good and tender as the first Dionysian call rising up out of the thickly growing bushes at the approach of spring.

But anyone familiar with German music of the Reformation will be aware of the musical naivety that marks the chorale hymns favoured by Luther. The rich choral writing of Bach was not derived from the melodies of the Lutheran chorales but from the general elaboration of harmony and counterpoint in the ‘Baroque’ musical forms encouraged by the Counter-Reformation.

The general preference of both Wagner and Nietzsche for polyphony as opposed to operatic monody and homophony reflects the particularly folkloric bent of German musical taste, since polyphony is originally a folk-musical tradition that grew out of communal round-songs. It was first introduced into serious church music in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance to the steadfast opposition of conservative popes like John XXII, who banished it from the liturgy in 1322 and lay bare its defects in his 1324 papal bull Docta sanctorum patrum (Teachings of the Holy Fathers):

Some [composers] break up their melodies with hockets or rob them of their virility with discant, three-voice music, and motets, with a dangerous element produced by certain parts sung on text in the vernacular; all these abuses have brought into disrepute the basic melodies of the Antiphonal and Gradual [the principal sections of Gregorian chant in the Mass]. These composers, knowing nothing of the true foundation upon which they must build, are ignorant of the church modes, incapable of distinguishing between them, and cause great confusion. The great number of notes in their compositions conceals from us the plainchant melody, with its simple well-regulated rises and falls that indicate the character of the church mode. These musicians run without pausing. They intoxicate the ear without satisfying it; they dramatize the text with gestures; and, instead of promoting devotion, they prevent it by creating a sensuous and indecent atmosphere. . . . Therefore, after consultation with these same brethren (the cardinals), we prohibit absolutely, for the future that anyone should do such things, or others of like nature, during the Divine Office or during the holy sacrifice of the Mass.[14]

The development of opera in Italy was due mainly to the rejection of polyphony and contrapuntal music in favor of a dramatic style of musical expression that declaimed the words of dramatic speeches and dialogues in recitatives that were almost sung but not fully melodic. What neither Wagner nor Nietzsche appreciated is the fact that this quasi-melodic recitative of the stile rapprensatitvo is in fact the dramatic foundation of the Italian opera of the Renaissance since it expresses all of the dramatic feelings directly, faithfully and forcefully. The ‘da capo’ arias that followed the recitatives for musical effect are not the bearers of the drama but merely the musical reflections and echoes of the dramatic recitatives.

In other words, the entire tragic action of drama rests on the narrations and emotional reactions of the characters to these narrations that are conveyed by the recitatives. The orchestra can always only be a vehicle of general feeling. While it can underscore what the verse depicts it cannot become a substitute for the latter. The first development of drama as mimetic dance and pantomime – such as the dithyramb in ancient Greece or folk-dance in most countries – is an improvement on solely orchestral music only insofar as it incorporates humans in its representations. Only theatrical plays with spoken dialogues and, more especially, operatic dramas with sung dialogues achieve the fullest expression of tragedy since they alone employ the incomparably expressive instrument of the human voice for the exposition of their tragic content. By contrast, a dramatic symphony can never approach the status of a tragic drama, even if it be interspersed, or concluded, with choral passages as, for example, in Berlioz’s Roméo et Juliette Symphony or Liszt’s Faust Symphony. For, the most sombre symphonic tone-poems cannot produce the full sympathy with the fate of a tragic human hero that alone leads to a recognition of the universal nature of the tragic condition of man and a subsequent desire for liberation from the phenomenal world. This recognition and this desire are indeed the essential constituents of tragedy, as they are of all true religion.

*

Since Italian church music was the basis of secular musical styles as well, we may briefly pause here to consider the nature of early Christian rituals. Among the Christians the sacraments themselves were considered to be ‘mysteries’, though the principal theological mysteries were those of the Holy Trinity, the Incarnation (or Virgin Conception of Jesus), and the Resurrection of Christ. Of these the incarnation itself is viewed as a divine fall for the purpose of the redemption of mankind, while the resurrection is the Christian counterpart of the ascent of Apollo from the Dionysiac solar force in the underworld. We must bear in mind that even the normal ‘mass’ of the Catholic Church is a dramatic sacrifical ritual since its climax is reached in the Eucharist, when the bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of the Christ, the sacrificial Lamb of God.

This death and resurrection of Christ were naturally, from the earliest times, the subject of various forms of sacred music. The Gregorian chants that flourished in central and western Europe from the ninth century were monophonic songs that were used in the masses of the Roman Rite of the western Catholic Church. Gregorian chant was used also in the Passion music of the Holy Week services. Responsorial Passion settings in which the narration is chanted by a small group of the choir and refrains are sung by the whole choir were another form of passion music, as also was the Tenebrae music of the Holy Week. Alongside these Passions, oratorios involving narration and dialogues between characters in sacred dramas originated in the early 17th century in Italy. These oratorios were doubtless influenced by the ‘new music’ propagated by Giulio Caccini in his monodic and operatic works and led to the well-known Baroque oratorio-Passions of the seventeeth and eighteenth centuries.

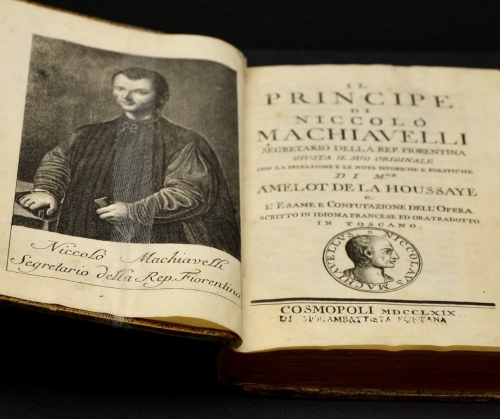

One of the first musicians to discover the importance of adhering to the text of songs or dramatic poems rather than developing melodic permutations and combinations independent of the text as in polyphony was Giulio Caccini (1551-1618), who developed the first operas in Italy within the learned circle of the Florentine Academy founded by the Byzantine philosopher Gemistus Pletho (ca.1355-1454) and the Florentine banker and patron of the arts, Cosimo de’ Medici (1389-1464), under the supervision of the Neoplatonist philosopher, Marsilio Ficino (1433-99). Caccini made it clear in the Preface to his Le nuouve musiche (1602) that polyphony was totally unsuited to musical expression of poetry and that the Greek song was essentially a solo song such as was praised by Plato. He declared that he had learnt from the members of the Florentine Academy

not to value the kind of music that prevents the words from being well understood and thus spoils the sense and the form of the poetry. I refer to the kind of music that elongates a syllable here and shortens one there to accommodate the counterpoint, turning the poetry to shreds. Instead, they urged me to adhere to the manner [of composition] praised by Plato and the other philosophers who affirm that music is nothing but speech, rhythm, and harmony. According to them, the purpose of music is to penetrate the minds of others and create the marvelous effects that writers admire. In modern music, these effects could not be achieved through counterpoint. Particularly in solo singing accompanied by string instruments, not a word could be understood in the pervasive vocalises, whether on short or long syllables. Furthermore, in every type of music, the common people would applaud and shout for serious singers only [if they produced] such vocalises.[15]

Given the vulgar neglect of the words of the musical performances, Caccini declares that

In both madrigals and arias [all in monodic style] I have always tried to imitate the ideas of the words, seeking more or less expressive notes to follow the sentiments of the words. I concealed the art of counterpoint as much as I could, to make the words as graceful as possible.

Indeed, Wagner too understands the importance of poetic diction in lyrical composition:

It was only the musician’s yearning to gaze into the poet’s eye which even rendered posible this appearance of melody upon the surface of the harmonic waters. And it was only the poet’s verse which could sustain the melody upon the surface of those waters, for otherwise though giving forth a fugitive utterance, it would in default of sustenance have only fallen back again into ocean depths. (Oper und Drama, Part III, Ch.3).

Particularly significant is Wagner’s oblique commendation of what is best developed in Italian opera as the ‘stile rappresentativo’, or quasi-melodic recitatives:

There proceeds from the pure faculty of speech such a fulness of the most manifold rhythmic assertive power … that all these riches, together with that fructification of the purely musical power of man which springs from them and which is exemplified in every art-creation brought forth by the inner poetical impulse, can only be properly described as absolutely immeasurable. (Part III, Ch.2)

The orchestral accompaniments themselves are merely highlights of the verse-melody:

The vivifying central point of dramatic expression is the actor’s articulate verse-melody, towards which absolute orchestral melody is drawn as a warning preparation and away from which the ‘thought’ of the orchestral motive leads as a remembrance Part III, Ch.6)

The orchestra can also substitute for the ‘gestures’ which formed essential parts of the mimetic dance-forms of folk-dance as well as of drama:

That which is offered to sight in the constant presence and motion of that exponent of articulate verse-melody – the actor – is dramatic gesture, that which makes this clear to the sense of hearing being the orchestra, the original and necessary effectiveness of which is confined to its being the harmonic bearer of the verse-melody … from the orchestra therefore, as from music’s richly emotional and maternal bosom, the unifying bond of expression proceeds. (Ibid.)

Wagner believed that the ultimate aim of musical development was the invention of a true melodic form that would, now that it has been filtered through the understanding, revive the original Feeling at the basis of all music in a much more faithful and concentrated form:

In the course of proceeding from articulate to tonal speech we arrived at the horizontal upper surface of harmony, playing upon the mirror of which the word-phrase of the poet was reflected back again as musical melody. Now … to the means of sinking into the fullest depths of that maternal element – of sinking therein that poetic intention which is as the productive agency, besides doing this so that every atom contained in the awful chaos of those depths shall be determined into a conscious and individual announcement though in no narrowing but in an ever-widening compass. Now, in short, for the artistic progress consisting of broadening out a definite and conscious intention into an emotional faculty which, notwithstanding that it is immeasurable, shall be of certain and precise manifestation.

This advanced form of melody will be a return of feeling developed through the intellect back to the primordial font of Feeling:

Real melody … stands in relation to the original maternal articulate melody as an absolute contrast, and one which … we may refer to as a progress from understanding to feeling, or as one out of speech to melody. This is in contradistinction to the former change from feeling to understanding and melody to speech. (Part III, Ch.3)

The final aim of Wagner’s innovation is indeed melody – not by itself, as in Italian operatic arias, but as ‘symphonic melody’. While this symphonic dimension of his melodies may be considered to be merely an orchestral addition to the melodic content of Italian arias, we cannot deny the extaordinary affective power of Wagner’s melodies as a successful fulfilment of his own musical aims.

It is also worth noting that, unlike Nietzsche, Wagner attributes the decay of tragedy not only to the intellectualisation of dramatic prosody but also to the social circumstances in which the high taste of the nobility was replaced by the commercial impresario who only seeks profits by propagating the puerile taste of a vulgar public. He reminds his readers that earlier works of art were brought to life by the nobility who formed the public for refined forms of art:

the excellent and specially refined productions of our art already existing … the incentive to the creation of such work proceeded from the taste of those before whom it had to be performed. What we find is that this public of higher feeling and taste in its condition of most active and definite sympathy with art-production first greets our view in the period of the Renaissance … passing its life gaily in palaces or bravely in war it had exercised both eye and ear in perception of the graceful, the beautiful and even of the characteristic and energetic, and it was at its command that the works of art arose which distinguish that period as the most fortunate for art since the decay of that of Greece. (Ch.VII)

Nowadays, however,

it is the man who pays the artist for that in respect of which nobility formerly rewarded him who is the ruler of public art-taste – the man who orders the art-work for his money – the man who wants his own favorite tune varied anew for novelty – but no new theme. This ruler and orderer is the Philistine, and this Philistine is … the most dastardly outcome of our whole civilisation … It is his will to be dastardly and vulgar, and art must accommodate itself thereto. Let us hasten to get him out of our sight.

In his essay, ‘Das Judenthum in der Musik’ (Jewry in Music) (1850) Wagner points particularly to the role that the Jews have played in the commercialisation of music:

What the heroes of the arts, with untold strain consuming lief and life, have wrested from the art-fiend of two millennia of misery, to-day the Jew converts into an artbazaar.

Wagner, on the other hand, sought to restore ‘a system in which the relation of art to public life such as once obtained in Athens should be re-established on an if possible still nobler and at any rate more durable footing’. This was the purpose underlying the treatise he published in 1849 called Kunst und Revolution (Art and Revolution).

*

If we turn back to Nietzsche now, we note that the Wagnerian focus on the maternal font of ‘Feeling’ is turned by Nietzsche into the realm of the ‘Dionysian’ spirit. Nietzsche follows Wagner in considering melody as the original element of musical expression:

The melody is thus the primary and universal fact, for which reason it can in itself undergo many objectifications, in several texts. It is also far more important and more essential in the naive evaluations of the people. Melody gives birth to poetry from itself, over and over again. (Die Geburt der Tragödie)

However, while Wagner sought to achieve a rearticulated melody that surpassed melodic verse, Nietzsche in Der Fall Wagner (The Case of Wagner) (1888) finally shrank back in horror from beautiful melody:

let us slander melody! Nothing is more dangerous than a beautiful melody!

Nothing is more certain to ruin taste![16]

The reason for his fear of Wagner’s melodic achievement is that it might lead to the collapse of music under the burden of expressiveness – as indeed happened with the appearance of the atonal post-Romantic music of Schoenberg:

Richard Wagner wanted another kind of movement, — he overthrew the physiological first principle of all music before his time. It was no longer a matter of walking or dancing, — we must swim, we must hover. . . . This perhaps decides the whole matter. “Unending melody” really wants to break all the symmetry of time and strength; it actually scorns these things — Its wealth of invention resides precisely in what to an older ear sounds like rhythmic paradox and abuse. From the imitation or the prevalence of such a taste there would arise a danger for music — so great that we can imagine none greater — the complete degeneration of the feeling for rhythm, chaos in the place of rhythm. . . . The danger reaches its climax when such music cleaves ever more closely to naturalistic play-acting and pantomime, which governed by no laws of form, aim at effect and nothing more…. Expressiveness at all costs and music a servant, a slave to attitudes — this is the end. . . .

Nietzsche’s insistence on rhythm is related to his preference for dance music, which he understands in the spirit of Dionysian or Bacchanalian choreography. However, since he does not intuit the religious character of Dionysian ritual as well as of the original Greek tragedies, we notice that Nietzsche’s understanding of the dance-forms of the Dionysiac mysteries is also rather deficient. While Wagner focussed on ‘gesture’ in early drama, and viewed the dance as the expression of simple dramatic actions, Nietzsche’s wild appeals to dance are more suggestive of modern ‘abstract’ dance. Thus it has been rightly maintained by Georges Liébert that Nietzsche spoke in his writings on tragedy and operatic music not about opera at all but about the ballet of composers like Ravel and Stravinsky.[17] In ‘Versuch einer Selbstkritik’ (An Attempt at Self-Criticism) (1886) – quoting from his own Also sprach Zarathustra (1883-85) and comically identifying Dionysus with Zarathustra – Nietzsche even exhorts the reader to

Lift up your hearts, my brothers, high, higher! And for my sake don’t forget your legs as well! Raise up your legs, you fine dancers, and better yet, stand on your heads!

Any writer who imagines the Iranian religious reformer Zoroaster as a ‘Dionysian’ priest proclaiming the above message to his listeners can hardly be considered an authority on either ancient religion or drama.

The real aim of Nietzsche’s parody of Zoroastrianism, as well as of Dionysiac religion, is of course his urge to remove moralism and all discussion of ‘good and evil’ from public discourse. To this end Wagner’s rejection of intellectualism in Euripides is transformed by Nietzsche into a single-minded attack on ‘moralism’.and ‘morality’.itself. But tragedy, as we have noted above, is in the nature of things moral. And Sophocles, whom Nietzsche admires above Euripides, was not more mindless of the gods than the latter. Even a brief glance at the final Chorus in Sophocles’ ‘Antigone’ will make this clear:

Of happiness the chiefest part Is a wise heart: And to defraud the gods in aught with peril’s fraught. Swelling words of high-flown might mightily the gods do smite. Chastisement for errors past Wisdom brings to age at last.[18]

The ulterior motive behind Nietzsche’s rejection of moralism is obviously his larger goal of eliminating Christianity from Europe,

Christianity as the most excessively thorough elaboration of a moralistic theme which humanity up to this point has had available to listen to. To tell the truth, there is nothing which stands in greater opposition to the purely aesthetic interpretation and justification of the world, as it is taught in this book, than Christian doctrine, which is and wishes to be merely moralistic and which, with its absolute standards, beginning, for example, with its truthfulness of God, relegates art, every art, to the realm of lies — in other words, which denies art, condemns it, and passes sentence on it.

*

Nietzsche indeed ignores the fact that it was the Church that created the first examples of modern tragic music, based on the ‘mysteries’ of the Christ story, in the West during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The Florentine opera that flourished during the Renaissance was also closer to the original Greek drama that both Wagner and Nietzsche wished to emulate than the German music of the time insofar as the focus on the musical quality of poetic declamation was perfected only in Renaissance Italy and in the Italian operatic tradition that followed from it. The monodic music that was championed by the first Italian operatic composers meant the rejection of polyphonic distractions for a concentrated attention on the texts of the dramas. For the intellectual understanding of the essentially tragic condition of man the text of the play is indeed indispensable, since it is the text of a tragic drama that – through its redevelopment of archetypal myths and histories – serves to remind us of the essential distress of the human condition. And a dramatic focus on the tragic condition of the hero as expressed in the text can be achieved only through poetic declamation, or its heightened musical counterparts – quasi-melodic recitatives and monodies.

Thus, while the maintenance of a more general mood of mourning, and of longing for wholeness, can be accomplished by both instrumental and vocal means, the painful conflicts of the drama can be expressed fully only by vocal recitatives and, occasionally, also by choral refrains. Indeed, it may even be said that only the vocal declamations of actors in a tragedy have the capacity of recalling to the listener the universal dimension of tragedy whereas purely instrumental, or ‘absolute’, music can arouse in him a heightened consciousness of only his own personal losses.

Tragedy, also, has not declined because of its moral content but through the democratic pandering to the vulgar tastes of the audiences. Opera seria, or tragic opera, which developed from the model of the Greek tragedies, did not decline through the Italian delight in melodious arias but through the lack of interest – among an increasingly vulgar public – in the intensely moving recititatives that constituted the declamatory core of these tragic music dramas. We see also from Nietzsche’s later criticisms of Wagner’s music that, despite the wondrous success of Wagner’s symphonic melodic elaboration of the Italian arias, the musical development that he represented was too easily capable of degeneration in the hands of lesser musicians than himself.

The tragic effects of opera seria are produced by reminders, necessarily ethical, and necessarily vocal, of the tragic condition of humanity in general. The latter is not located vaguely in a subconscious Dionysian spirit, as uncontrolled energy, but in the subjective perception of this condition by the individual viewer who sympathises with the tragic protagonists through what Aristotle called ‘pity and fear’.

The essential feeling of all tragic drama is indeed one of loss. This is not a sense of personal loss, but an awakening of the awareness of the first Fall of man, from God – as Schopenhauer had perceptively pointed out. And this fatal Fall can only be overcome through an intellectual as well as emotional apperception of it and a concomitant longing to regain the divine. These feelings are most effectively produced in the realm of art by tragic drama and opera. Whatever the course of Dionysiac or Bacchanalian rituals may have been, the tragic dramas and operas that evolved from them are thus necessarily infused with moral resonances. All tragedy – ancient Greek as well as modern – is in this sense fundamentally moral because it is fundamentally religious.

[1] universals after the fact

[2] universals before the fact

[3] universals in the fact

[4] The Birth of Tragedy out of the Spirit of Music, tr. Ian Johnston.

[5] Welt als Wille und Vorstellung (1818-59), III, 51, tr. K.B. Haldane and J. Kemp..

[6] For a full discussion of the Purusha mythology, see A. Jacob, Ātman: A Reconstruction of the Solar Cosmology of the Indo-Europeans, Hildesheim: Georg Olms, 2005 and Brahman: A Study of the Solar Rituals of the Indo-Europeans, Hildesheim: Georg Olms, 2012.

[7] Dionysus, according to Nonnos, is the ‘second Zeus’ (see Nonnos, Dionysiaca, 10, 298). The ‘first Zeus’ is Zeus Aitherios, who is identical to Chronos (see Cicero, De Natura Deorum, III,21).

[8] See A. Jacob, ‘Reviving Adam: The Sacrificial Rituals of the Indo-Āryans and the Early Christians’, Manticore Press.

[9] See Plato, Laws, III, 700b-e, Republic, III, 394b-c.

[10] All citations from Richard Wagner’s works are from Richard Wagner’s Prose Works, tr. W.A. Ellis.

[11] A. Schopenhauer, ibid.

[12] In fact, Nietzsche himself was later so embarrassed of this essay that he wrote an appendix to it called ‘Versuch einer Selbstkritik’ (An Attempt at Self-Criticism) (1886).

[13] The German translation of this essay was published in 1861as Zukunftsmusik.

[14] See Corpus iuris canonici, 1879, Vol. I, pp. 1256–1257.

[15] ‘Extracts from Introduction to Le nuove musice (1602)’, tr. Zachariah Victor.

[16] ‘The Case of Wagner’, tr. A.M. Ludovici.

[17] See G. Liébert, Nietzsche and Music, (tr. D. Pellauer and G. Parkes), Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, p.82.

[18] Antigone, tr. F. Storr.

Aujourd’hui la transformation est largement accentuée avec la métropolisation du monde : l’interconnexion des capitales et des grandes villes fait qu’il existe souvent plus de liens entre elles qu’entre chacune d’elles et son propre arrière-pays. D’où, parfois, un sentiment d’abandon au sein des périphéries rurales (thème devenu récurrent en France).

Aujourd’hui la transformation est largement accentuée avec la métropolisation du monde : l’interconnexion des capitales et des grandes villes fait qu’il existe souvent plus de liens entre elles qu’entre chacune d’elles et son propre arrière-pays. D’où, parfois, un sentiment d’abandon au sein des périphéries rurales (thème devenu récurrent en France).

Jean-Pierre Vernant, dans « Les origines de la pensée grecque », souligne que « le système de la polis, c’est d’abord une extraordinaire prééminence de la parole sur tous les autres instruments du pouvoir ». C’est ce qui explique l’importance accordée au fait de « tenir parole » chez les peuples primitifs. « Donner sa parole » signifie que le locuteur implique toute sa personne dans son discours et qu’il ne sert point d’obscurs intérêts qui agissent par procuration. L’orateur de la Grèce antique prend la parole afin d’apporter sa pierre à l’édification d’une polis qui ne peut se concevoir sans la participation effective de ses constituants, les citoyens.

Jean-Pierre Vernant, dans « Les origines de la pensée grecque », souligne que « le système de la polis, c’est d’abord une extraordinaire prééminence de la parole sur tous les autres instruments du pouvoir ». C’est ce qui explique l’importance accordée au fait de « tenir parole » chez les peuples primitifs. « Donner sa parole » signifie que le locuteur implique toute sa personne dans son discours et qu’il ne sert point d’obscurs intérêts qui agissent par procuration. L’orateur de la Grèce antique prend la parole afin d’apporter sa pierre à l’édification d’une polis qui ne peut se concevoir sans la participation effective de ses constituants, les citoyens.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

This mammoth volume is a collection of twenty distinct philosophical reflections written over the course of a decade. Most of them are essays, some almost of book length. Others would be better described as papers. A few are well structured notes. There is also one lecture. A magnum opus like Prometheus and Atlas does not emerge from out of a vacuum, and an alternative title to these collected works could have been “The Path to Prometheus and Atlas.” While there are a few pieces that postdate not only that book but also World State of Emergency, most of the texts included here represent the formative phase of my thought. Consequently, concepts such as “the spectral revolution” and “mercurial hermeneutics” are originally developed in these essays.

This mammoth volume is a collection of twenty distinct philosophical reflections written over the course of a decade. Most of them are essays, some almost of book length. Others would be better described as papers. A few are well structured notes. There is also one lecture. A magnum opus like Prometheus and Atlas does not emerge from out of a vacuum, and an alternative title to these collected works could have been “The Path to Prometheus and Atlas.” While there are a few pieces that postdate not only that book but also World State of Emergency, most of the texts included here represent the formative phase of my thought. Consequently, concepts such as “the spectral revolution” and “mercurial hermeneutics” are originally developed in these essays.

Ainsi, face à la désorientation du pouvoir qui veut faire croire qu’il n’existe plus qu’un modèle de société, que “there is no alternative” et que cette non alternative est toute couleur métisse, l’État total se heurtera très vite à un sérieux problème de moyens et de compétences au point qu’au final, les citoyens ne pourront et surtout ne devront se défendre que seuls, en somme ne compter finalement pour leur sécurité que sur eux-mêmes.

Ainsi, face à la désorientation du pouvoir qui veut faire croire qu’il n’existe plus qu’un modèle de société, que “there is no alternative” et que cette non alternative est toute couleur métisse, l’État total se heurtera très vite à un sérieux problème de moyens et de compétences au point qu’au final, les citoyens ne pourront et surtout ne devront se défendre que seuls, en somme ne compter finalement pour leur sécurité que sur eux-mêmes.

Footnotes:

Footnotes:

Bien avant Daech, Soljenitsyne observe :

Bien avant Daech, Soljenitsyne observe :

La rencontre Carl Schmitt et Julien Freund, à Colmar, en 1959, Julien Freund qui confia : « J’avais compris jusqu’alors que la politique avait pour fondement une lutte opposant des adversaires. Je découvris la notion d’ennemi avec toute sa pesanteur politique, ce qui m’ouvrait des perspectives nouvelles sur les notions de guerre et de paix ». Ce concept ami/ennemi est inconfortable puisqu’il donne une consistance à la guerre, ce que refusent les pacifistes qui envisagent l’avènement de la paix perpétuelle comme d’autres envisagent la Parousie.

La rencontre Carl Schmitt et Julien Freund, à Colmar, en 1959, Julien Freund qui confia : « J’avais compris jusqu’alors que la politique avait pour fondement une lutte opposant des adversaires. Je découvris la notion d’ennemi avec toute sa pesanteur politique, ce qui m’ouvrait des perspectives nouvelles sur les notions de guerre et de paix ». Ce concept ami/ennemi est inconfortable puisqu’il donne une consistance à la guerre, ce que refusent les pacifistes qui envisagent l’avènement de la paix perpétuelle comme d’autres envisagent la Parousie. Les conflits sont de plus en plus économiques. Ils l’ont toujours été d’une manière ou d’une autre mais dans des proportions variables et parfois assez limitées. Aujourd’hui, l’économique draine tout à lui, et toujours plus frénétiquement, ce qui explique la liquidité des conflits, le fait qu’ils se jouent des frontières et se dématérialisent. Fini les lignes de front et les tirs de barrage. Le conflit est permanent et de ce fait d’une intensité moindre ; mais il est permanent – plus de trêve. Les médias sous toutes leurs formes ne cessent de nous le rappeler, implicitement ou explicitement. Mais comment départager vainqueur et vaincu ? Il n’y en a tout simplement plus, le conflit est devenu perpétuel.

Les conflits sont de plus en plus économiques. Ils l’ont toujours été d’une manière ou d’une autre mais dans des proportions variables et parfois assez limitées. Aujourd’hui, l’économique draine tout à lui, et toujours plus frénétiquement, ce qui explique la liquidité des conflits, le fait qu’ils se jouent des frontières et se dématérialisent. Fini les lignes de front et les tirs de barrage. Le conflit est permanent et de ce fait d’une intensité moindre ; mais il est permanent – plus de trêve. Les médias sous toutes leurs formes ne cessent de nous le rappeler, implicitement ou explicitement. Mais comment départager vainqueur et vaincu ? Il n’y en a tout simplement plus, le conflit est devenu perpétuel.

La même constatation d’une situation de relative déshérence historiographique et surtout de la priorité donnée au choix de coupures par périodes (Renaissance, XVIIe siècle) peut être constatée pour ce qui est de la recherche anglo-saxonne, après les deux volumes de l’History of Europe de H. A. L. Fisher (Londres, 1935). Citons l’exemple de la Short Oxford History of Europe qui, si elle est récente, n’en est pas moins très traditionnelle dans sa conception clivant le passé en grandes séquences classiques si ce n’est anachronisantes, à commencer par « Classical Greece » ou « Roman Europe » ; citons aussi, plus originales, les New Approaches to European History de Cambridge Uni- versity Press et les Fontana History of Europe Series qui reposent sur un projet thématico-chronologique. À quoi s’ajoute The Penguin History of Europe, de J. M. Roberts (1996), fort heureusement renouvelée dans les Penguin History of Europe Series grâce aux contributions de grands spécialistes comme Chris Wickham ou Mark Greengrass. Là est le paradoxe, c’est la Grande-Bretagne du Brexit d’aujourd’hui qui a donné récemment les ouvrages scientifiques les plus parachevés sur une Europe désanachronisée et pensée comme une totalité d’histoire ayant fonctionné plus sur des connexions que sur des spécificités ou sur des collections de particularités. Pour aller dans cette direction, l’histoire de l’Europe se trouve travaillée outre-Manche surtout systématiquement sur le plan de l’histoire économique, avec The Cambridge Economic History of Europe et The Fontana Economic History of Europe. Un peu à part, original, et soupçonné aujourd’hui d’européo-centrisme parce que donnant le primat à la question de l’exceptionnalité du continent désormais passé de mode, il y a le livre important d’Eric Jones, The European Miracle (Cambridge, 1981) à l’inverse du plus superficiel Europe. A History, de Norman Davies (Oxford, 1996). Il faudrait signaler encore Eugen Weber et Une histoire de l’Europe, Paris (2 vol., Paris, 1986-1987), qui insiste sur le concept postromantique d’héritage légué au monde mais noie le lecteur sous une avalanche factuelle donnant une certaine invisibilité à l’objet même Europe.

La même constatation d’une situation de relative déshérence historiographique et surtout de la priorité donnée au choix de coupures par périodes (Renaissance, XVIIe siècle) peut être constatée pour ce qui est de la recherche anglo-saxonne, après les deux volumes de l’History of Europe de H. A. L. Fisher (Londres, 1935). Citons l’exemple de la Short Oxford History of Europe qui, si elle est récente, n’en est pas moins très traditionnelle dans sa conception clivant le passé en grandes séquences classiques si ce n’est anachronisantes, à commencer par « Classical Greece » ou « Roman Europe » ; citons aussi, plus originales, les New Approaches to European History de Cambridge Uni- versity Press et les Fontana History of Europe Series qui reposent sur un projet thématico-chronologique. À quoi s’ajoute The Penguin History of Europe, de J. M. Roberts (1996), fort heureusement renouvelée dans les Penguin History of Europe Series grâce aux contributions de grands spécialistes comme Chris Wickham ou Mark Greengrass. Là est le paradoxe, c’est la Grande-Bretagne du Brexit d’aujourd’hui qui a donné récemment les ouvrages scientifiques les plus parachevés sur une Europe désanachronisée et pensée comme une totalité d’histoire ayant fonctionné plus sur des connexions que sur des spécificités ou sur des collections de particularités. Pour aller dans cette direction, l’histoire de l’Europe se trouve travaillée outre-Manche surtout systématiquement sur le plan de l’histoire économique, avec The Cambridge Economic History of Europe et The Fontana Economic History of Europe. Un peu à part, original, et soupçonné aujourd’hui d’européo-centrisme parce que donnant le primat à la question de l’exceptionnalité du continent désormais passé de mode, il y a le livre important d’Eric Jones, The European Miracle (Cambridge, 1981) à l’inverse du plus superficiel Europe. A History, de Norman Davies (Oxford, 1996). Il faudrait signaler encore Eugen Weber et Une histoire de l’Europe, Paris (2 vol., Paris, 1986-1987), qui insiste sur le concept postromantique d’héritage légué au monde mais noie le lecteur sous une avalanche factuelle donnant une certaine invisibilité à l’objet même Europe. On peut, entre autres travaux individuels ou collectifs, ajouter à cette sphère d’écriture Krzysztof Pomian, L’Europe et ses nations (Paris, 1990), puis Jacques Le Goff, La Vieille Europe et la nôtre (Paris, 1994) ou L’Europe est-elle née au Moyen Âge ? (Paris, Seuil, 2003). L’ouvrage de Denis de Rougemont, Vingt-huit siècles de l’Europe, la conscience européenne à travers les textes d’Hésiode à nos jours (Paris, 1961), est un produit militant issu de la réflexion de l’un des fondateurs du projet européen de l’après-1945. Notons encore Identités nationales et conscience européenne, sous la direction de Joseph Rovan et Gilbert Krebs (Paris, 1992). Et encore, L’Europe dans son histoire. La vision d’Alphonse Dupront, publié par François Crouzet et François Furet (Paris, 1998). Ou Penser l’Europe, d’Edgar Morin (Paris, 1987), qui met l’accent sur la complexité européenne, et sur le dialogue des pluralités ou l’interculturalité étant le moteur interne de l’histoire de l’Europe, « unitas multiplex ».

On peut, entre autres travaux individuels ou collectifs, ajouter à cette sphère d’écriture Krzysztof Pomian, L’Europe et ses nations (Paris, 1990), puis Jacques Le Goff, La Vieille Europe et la nôtre (Paris, 1994) ou L’Europe est-elle née au Moyen Âge ? (Paris, Seuil, 2003). L’ouvrage de Denis de Rougemont, Vingt-huit siècles de l’Europe, la conscience européenne à travers les textes d’Hésiode à nos jours (Paris, 1961), est un produit militant issu de la réflexion de l’un des fondateurs du projet européen de l’après-1945. Notons encore Identités nationales et conscience européenne, sous la direction de Joseph Rovan et Gilbert Krebs (Paris, 1992). Et encore, L’Europe dans son histoire. La vision d’Alphonse Dupront, publié par François Crouzet et François Furet (Paris, 1998). Ou Penser l’Europe, d’Edgar Morin (Paris, 1987), qui met l’accent sur la complexité européenne, et sur le dialogue des pluralités ou l’interculturalité étant le moteur interne de l’histoire de l’Europe, « unitas multiplex ». On pourrait encore évoquer le centrage sur la démographie, avec l’Histoire des populations de l’Europe éditée par Jean-Pierre Bardet et Jacques Dupaquier (3 vol., Paris, 1997), sur l’histoire de l’écosystème, avec l’Histoire de l’environnement européen de Robert Delort (préface de Jacques Le Goff, Paris, 2001). L’Europe peut encore s’écrire dans la longue durée de son histoire économique tendant vers une « unité organique » malgré ses « diversités », avec L’Histoire de l’économie européenne 1000-2000 de François Crouzet (Paris, 2000) : « On essaiera constamment de considérer l’Europe comme un ensemble, et de prêter attention aux relations entre ses diverses parties : au commerce intra-européen, qui s’est développé de bonne heure, notamment sur la base des dotations différentes en ressources de l’Europe du Nord et de celle du Sud ; à la diffusion des institutions, des organisations et des technologies, aux migrations de main-d’œuvre et de capitaux. On recherchera les forces qui ont rapproché les régions européennes et contribué à créer une économie européenne intégrée – même si ce ne fut que de façon lâche. Cependant, ni les forces centrifuges, ni les rapports avec le monde extérieur ne seront négligés… ». D’autres enquêtes se sont fixées dans la problématique de Les Racines de l’identité européenne, de Francis Dumont (Paris, 1999) ou de La Conscience européenne au XVIe siècle de Françoise Autrand et Nicole Cazauran (éd.) (Paris, 1983) ; ou dans le champ de l’histoire des relations internationales avec L’Ordre européen du XVIe au XXe siècle, dirigé par Georges-Henri Soutou (Paris, 1998) ou La Société des princes (Paris, 1999), de Lucien Bély.

On pourrait encore évoquer le centrage sur la démographie, avec l’Histoire des populations de l’Europe éditée par Jean-Pierre Bardet et Jacques Dupaquier (3 vol., Paris, 1997), sur l’histoire de l’écosystème, avec l’Histoire de l’environnement européen de Robert Delort (préface de Jacques Le Goff, Paris, 2001). L’Europe peut encore s’écrire dans la longue durée de son histoire économique tendant vers une « unité organique » malgré ses « diversités », avec L’Histoire de l’économie européenne 1000-2000 de François Crouzet (Paris, 2000) : « On essaiera constamment de considérer l’Europe comme un ensemble, et de prêter attention aux relations entre ses diverses parties : au commerce intra-européen, qui s’est développé de bonne heure, notamment sur la base des dotations différentes en ressources de l’Europe du Nord et de celle du Sud ; à la diffusion des institutions, des organisations et des technologies, aux migrations de main-d’œuvre et de capitaux. On recherchera les forces qui ont rapproché les régions européennes et contribué à créer une économie européenne intégrée – même si ce ne fut que de façon lâche. Cependant, ni les forces centrifuges, ni les rapports avec le monde extérieur ne seront négligés… ». D’autres enquêtes se sont fixées dans la problématique de Les Racines de l’identité européenne, de Francis Dumont (Paris, 1999) ou de La Conscience européenne au XVIe siècle de Françoise Autrand et Nicole Cazauran (éd.) (Paris, 1983) ; ou dans le champ de l’histoire des relations internationales avec L’Ordre européen du XVIe au XXe siècle, dirigé par Georges-Henri Soutou (Paris, 1998) ou La Société des princes (Paris, 1999), de Lucien Bély.

On peut poursuivre avec Ernst Kantorowicz et son parcours qui le mène tout d’abord de Frédéric II, empereur-sauveur, et d’un attachement à un Reich imaginé régénérateur, de la foi dans le génie de la nation allemande, au boycott de ses cours par les étudiants nazis, puis à son exfiltration d’Allemagne. Parvenu aux USA et nommé à Berkeley, il doit affronter le maccarthysme en se faisant le défenseur d’une conception européenne de l’université à laquelle il reste attaché. Et son œuvre, qui est alimentée de multiples sources puisées dans des espaces et des temps différents, Gérald Chaix l’écrit, dépasse les évidences dans un paradoxe apparent : parce que sa « perspective est d’emblée européenne, même si, dans sa lecture impériale, il attribue à une Allemagne imprégnée de romanité un destin privilégié. Elle le demeure lorsque les circonstances, mais aussi ses propres choix, l’en éloignent. Elle se précise lorsque étudiant la conception anglaise des deux corps du roi, il situe explicitement celle-ci dans la construction chronologique et géographique d’une histoire européenne nullement close sur elle-même. » Kantorowicz pense par l’Europe. L’Europe conditionne sa pensée et son inventivité d’historien.

On peut poursuivre avec Ernst Kantorowicz et son parcours qui le mène tout d’abord de Frédéric II, empereur-sauveur, et d’un attachement à un Reich imaginé régénérateur, de la foi dans le génie de la nation allemande, au boycott de ses cours par les étudiants nazis, puis à son exfiltration d’Allemagne. Parvenu aux USA et nommé à Berkeley, il doit affronter le maccarthysme en se faisant le défenseur d’une conception européenne de l’université à laquelle il reste attaché. Et son œuvre, qui est alimentée de multiples sources puisées dans des espaces et des temps différents, Gérald Chaix l’écrit, dépasse les évidences dans un paradoxe apparent : parce que sa « perspective est d’emblée européenne, même si, dans sa lecture impériale, il attribue à une Allemagne imprégnée de romanité un destin privilégié. Elle le demeure lorsque les circonstances, mais aussi ses propres choix, l’en éloignent. Elle se précise lorsque étudiant la conception anglaise des deux corps du roi, il situe explicitement celle-ci dans la construction chronologique et géographique d’une histoire européenne nullement close sur elle-même. » Kantorowicz pense par l’Europe. L’Europe conditionne sa pensée et son inventivité d’historien. Penser par l’Europe, mais aussi penser pour l’Europe. La seconde partie du livre s’attache à une autre modalité de mise en problème historique de l’Europe. Avec en ouverture bien sûr, Johan Huizinga qui traduit une volonté d’écrire une histoire de l’Europe dans la perspective d’une fin de durée, un « automne » du Moyen Âge d’abord franco-bourguignon caractérisé par une exacerbation d’affects contradictoires, l’exubérance d’une vie contrastée mais commune. Et ensuite, après les idéaux chevaleresques, il y eut les idéaux renaissants qui transcendèrent la diversité des hommes et des nations. Et Jean-Baptiste Delzant d’insister sur un point : l’Europe de Huizinga est d’abord un « esprit » transhistorique qui en appelle à un « besoin d’unité civilisatrice » et donc à une exigence morale partagée et conceptualisée, entre autres, par Érasme. L’histoire apparaît tel un bouclier, une mise en défense contre les idéologies négatives ultranationalistes, contre les ruines qui en adviennent et en sont advenues au cours du XXe siècle, et pour Huyzinga, de ce fait, elle a un avenir et un présent : « donner corps à une unité désirée… ».

Penser par l’Europe, mais aussi penser pour l’Europe. La seconde partie du livre s’attache à une autre modalité de mise en problème historique de l’Europe. Avec en ouverture bien sûr, Johan Huizinga qui traduit une volonté d’écrire une histoire de l’Europe dans la perspective d’une fin de durée, un « automne » du Moyen Âge d’abord franco-bourguignon caractérisé par une exacerbation d’affects contradictoires, l’exubérance d’une vie contrastée mais commune. Et ensuite, après les idéaux chevaleresques, il y eut les idéaux renaissants qui transcendèrent la diversité des hommes et des nations. Et Jean-Baptiste Delzant d’insister sur un point : l’Europe de Huizinga est d’abord un « esprit » transhistorique qui en appelle à un « besoin d’unité civilisatrice » et donc à une exigence morale partagée et conceptualisée, entre autres, par Érasme. L’histoire apparaît tel un bouclier, une mise en défense contre les idéologies négatives ultranationalistes, contre les ruines qui en adviennent et en sont advenues au cours du XXe siècle, et pour Huyzinga, de ce fait, elle a un avenir et un présent : « donner corps à une unité désirée… ».

The cause of this misunderstanding of Euripidean tragedy may be traced back to Richard Wagner’s analyses of Greek drama in his Oper und Drama (Opera and Drama) (1851), Bk.III, Ch.3:

The cause of this misunderstanding of Euripidean tragedy may be traced back to Richard Wagner’s analyses of Greek drama in his Oper und Drama (Opera and Drama) (1851), Bk.III, Ch.3: