Vers des régimes autoritaires en France et en Europe?

Sur la crise des démocraties et la transition des formes politiques

Irnerio Seminatore

***

TABLE DES MATIÈRES

Introduction. Corruption et changement des régimes politiques

La crise des fondements, le déclin français et la tentation autoritaire

Régimes égalitaristes et régimes hiérarchiques

La souveraineté et ses interprètes, Tocqueville, Rousseau et C.Schmitt

Macron, la France et l'Europe

La démocratie est elle en danger?

La dérive autoritaire de la démocratie

L'affaiblissement de l'esprit de liberté et la transformation de l’État démocratique en l’État

bureaucratique.

Sur le rôle de la "Formule politique"

Guerre et liberté

Sur la crise des démocratie et l’évolution vers des régimes autoritaires

États et violence politique

Les menaces portées contre la démocratie: un tabou de la communication politique

La recherche d'un ordre alternatif

Essor et évolution des régimes autoritaires en Europe

La "Nouvelle Frontière" de l'Europe, le Souverainisme

Souverainisme et populisme. Stratégie et tactique

La révolution numérique et le contrôle social

Phénomènes de normalisation, de violence et de sanction du XXIeme siècle.

Michel Foucault et sa "notion d'homme"

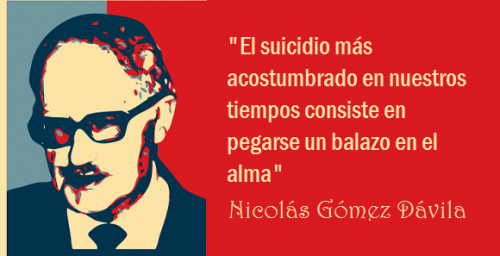

La folie et la mort. Le suicide d'Hamlet à Elsinor

***

Introduction. Corruption et changement des régimes politiques

Dans une période de "fake news" et de perversions sémantiques est-il surprenant de se révolter contre le chaos ou l'anarchie, là même où d'autres y voient la démocratie, la liberté d'expression et l'égale condition de la nature humaine? Quelles preuves apporter à la marche vers des régimes autoritaires, si non des exemples de conduite déviants, par rapport à des normes et des pratiques ancrées dans une tradition, ou dans une préférence politique héritées du passé? Passant à la formulation d'hypothèses crédibles, le besoin d'ordre et de sécurité peut-il être compris intuitivement comme demande de protection, face à des grandes crises d'autorité ou, en revanche, comme angoisse sociale, difficile à affronter avec les moyens du débat et de l'intégration et exigeant plutôt ceux de la force et de la répression?

Or, comprendre la transition actuelle des démocraties vers des régimes autoritaires, c'est faire référence à trois types d'explication:

- d'ordre historique

- d'ordre politique et culturel

- d’ordre sociologique, scientifique et psychologique.

Pour le premier type, je retiendrais l'explication classique, celle de la décomposition de la démocratie et de la théorie des cycles historiques.

Pour le deuxième, la crise des fondements, la conception du pouvoir et l'affaiblissement de l'esprit de liberté.

Pour la troisième, celle des systèmes de contrôle et de manipulation des opinions et de la disponibilité des masses à l'asservissement vis à vis d'un maître.

Des éléments des trois critères se retrouvent dans l'impossible conciliation de la souveraineté étatique, de la liberté individuelle et des convictions populaires, qui définissent le pouvoir démocratique. Ainsi permanence et discontinuité s'en trouvent bouleversées et besoin et inquiétude du changement, intimement liées. Cette situation affecte la conception héritée de la démocratie et augmente la séduction des régimes autoritaires, tenus pour naturels et parfois nécessaires.

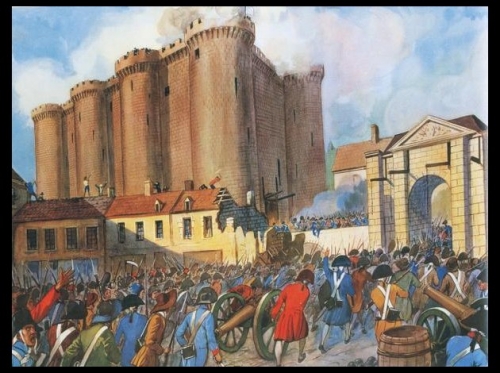

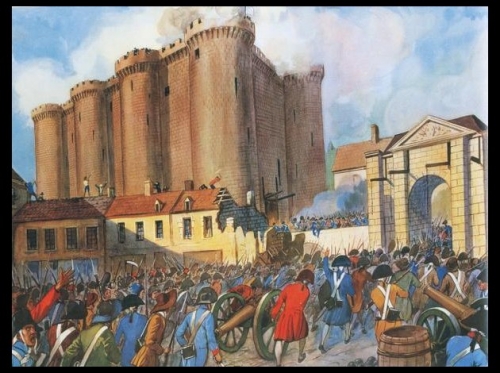

En effet dans le courant de derniers deux cent cinquante ans, nous sommes passés,en Europe, des monarchies de droit divin à des monarchies constitutionnelles, puis à des républiques présidentielles et, au XXème siècle après deux grandes révolutions, communiste et national-socialiste à l'ère des tyrannies, pour adopter enfin, à cheval du XXIème siècle, l'âge des démocraties.

Suite à la défaite des pays totalitaires, à la dislocation des empires et à la décolonisation du monde dans la deuxième partie du XXème siècle, nous sommes devenus de colonisateurs, colonisés et l'hétérogénéité des traditions historiques s'est transformée en une uniformisation forcée des conceptions politiques.

Par ailleurs, et comme conséquence du processus de mondialisation, qui a accompagné l'effondrement du communisme soviétique, le pouvoir occidental s'est assuré du consensus des peuples par l'idéologie de l'élargissement de la démocratie.

Or, le trait commun de celle-ci a reposé en Europe sur la dispersion des fonctions d'autorité et, plus de toute autre, de l'autorité souveraine, individuelle ou collective. Au sein de l'Union européenne la souveraineté est en fait partagée entre oligarchies bureaucratiques multiples, qui cachent le polycentrisme des pouvoirs et une gouvernance non élective, se réclamant d'un autoritarisme libéral.

En France, cette dispersion du pouvoir souverain n'a pas tenu compte de la diversité des populations et de conceptions éthiques et civilisationnelles, qui affectent en profondeur l'esprit public, chez les masses et chez les élites et a poursuivi les raisonnements et les pratiques de la tradition républicaine, remaniée par la cinquième république.

L'anarchie universitaire et syndicale, prônant la mort de l’État policier, détesté par Mai 68, puis le retour au pouvoir du général de Gaulle, accusé de bonapartisme par des intellectuels qui se voulaient sans dieu ni maître, suscita un tournant des opinions à la faveur de l'homme du salut.

Dans de pareilles situations et selon Aristote, les démocraties se corrompent et les guerres civiles naissent, exaspérant les conflits des factions et les rivalités entre les individus et les représentants du pouvoir. Puisque les luttes intestines ne trouvent de limites, ni dans la loi, ni dans les mœurs, devenus sans freins, le libre cours aux détracteurs de l'autorité et à la haine des exclus, affaiblissent l'autorité, réclamant à grand voix, un changement de régime.

C'est aujourd'hui le cas de Macron.qui est au même temps un jacobin, ignorant la raison d’État et un progressiste universaliste, qui méprise l'homme du peuple, bref un souverain, en état de guerre permanente avec ses sujets, de plus en plus hostiles à sa politique.

Selon la vulgate classique, les démocraties sont entraînées vers leur mort et vers l'instauration de régimes autoritaires, lorsque les opinions et les masses, opposées à la classe des privilégiés, se soumettent au pouvoir salvateur d'un chef, populiste ou démagogue, qui les entraîne à la conquête du pouvoir d’État.

Ainsi se succèdent les différentes formes des régimes politiques, qui transforment la liberté en licence et la démocratie en tyrannie, l'excès de liberté entraînant en retour un excès de servitude. Puisque le peuple est animé par des formes dégradées de connaissance, l'apparence, les préjugés et les passions, Aristote en concluait que la meilleure forme de gouvernement est le régime mixte, une composition de démocratie et d'aristocratie, option qui sera reprise par Machiavel à la Renaissance et à laquelle, dans les premières décennies du XXème siècle, Pareto, Mosca et Michels, adapteront la théorie des d'élites dans le but d'étudier la stabilité des partis politiques et la tendance oligarchique des démocraties.

La crise des fondements, le déclin français et la tentation autoritaire

En ce qui concerne le deuxième critère, la conception du pouvoir dans les démocraties d'aujourd'hui, celles-ci ne peuvent rester indifférentes à la crise des fondements, les principes premiers et ultimes de l'autorité de commandement, le consentement volontaire ou la rigueur de la loi. Or une crise des fondements est avant tout une grande crise intellectuelle et morale, une crise de foi, de sens et de société,bref une remise en cause des paradigmes, engendrant une énième subversion de la conscience européenne.

Elle met en cause le passé, le présent et l'avenir et concerne le peuple dans son ensemble. Le choix qu'elle implique appartient-il au "demos", au souverain, ou à Dieu? A la démocratie ou au pouvoir suprême? A l'histoire ou à la politique?

La crise actuelle engage en profondeur la responsabilité du citoyen et, puisque le pouvoir de commandement implique "l'obéissance" des sujets, qui est la consistance effective de la souveraineté, le régime politique confronté au problème de l'adhésion volontaire tirera une grande difficulté de la division du peuple, qui se niche dans la composition même de celui-ci. Un peuple aux deux identités, dont l'âme se divise en deux inimitiés existentielles, dictées par la pluralité des Dieux, est un peuple déchiré entre deux obéissances, à la loi divine, par sa nature universelle, et à la loi politique, par sa nature séculière et nationale.

C'est la situation de la France d'aujourd'hui, la France, jadis pays-guide de l'Europe et actuellement déchirée par la présence sur son sol de deux civilisations hostiles, irréconciliables et en état de guerre virtuelle.

Or, les régimes politiques existants sont l'expression, dans la Gaule et en Europe, d'une seule culture collective, des mêmes sentiments ancestraux, ou , en d'autres termes, de la même foi en Dieu, en la loi et en l'homme de raison.

Le déclin français, commencé en 1789, avec la "Grande Révolution", le rabaissement de la noblesse et l'hiver démographique,se poursuit avec l'égarement de ses croyances anciennes, qui justifient aujourd'hui son agnosticisme moral par le primat de la "raison" et par l'absence de principes d'ordre métaphysique, exaltant une sécularisation dévoyée et une Église ouverte à l'Islam.

Il continue avec Macron, épris par un aveuglement historique, qui, en mal de stabilité politique, a osé l'hérésie sacrilège, affirmant à Lyon que "la culture française n'existe pas et qu'elle est diverse et multiple"?( 6 février 2017). Le but de complaire à une foule inculte, maghrébine et barbaresque, étrangère à l'histoire du pays, l'a trahi dans l'oubli que l'unité culturelle garantit et préserve l'intégrité d'une nation.

Pouvait il sacraliser autrement une République sans unité, sans hiérarchie et sans Histoire, qui a remplacé les révolutions par les invasions, changeant de visage à la barbarie?

Or, puisque toute solution politique est l'usage combiné de l'autorité, de la loi et de la force, comment la "classe politique" pourra -t- elle réagir à la révolte des masses, offertes par son Prince à toute tentation et à tout reniement?

Du même coup, le rassemblement du Tiers-État, la plèbe moderne des vieux français des terroirs, des petits commerçants et chômeurs, rejetés par une mondialisation dévastatrice, mobilisant révolte et envie de réformes, a consenti aux ennemis du peuple, les black-blocs ou les islamo-gauchistes, d'utiliser au sein de ce mouvement la violence et la subversion.

Cette convergence entre le légitime et l'illégitime, a corrompu l'adhésion du peuple et a justifié la riposte autoritaire de Macron, qui n'a pas la religion de la gloire de Louis XIV, ni celle de la grandeur de de Gaulle et qui ne sait combiner l'alliance traditionnelle du Roi et du Tiers État, en associant les deux formes politiques, par lesquelles se décomposent aujourd'hui les démocraties, l'oligarchie mondialiste et la tyrannie monarchiste.

Le combat contre la ruine de "l'esprit français", si patente de nos jours, avait pourtant débuté à Londres en juin 1940, dans le but de maintenir la France occupée, dans un état de liberté d'esprit contre les formes variées de séduction et de soumission intellectuelles venant de l'occupation allemande, car "l'esprit français" ne se concevait, à l'époque, que dans son lien avec une nation libre et dans la lecture d'une histoire engagée, qui partagerait le corpus philosophique de la liberté.

Le débat sur la démocratie et les régimes autoritaires ouvre aujourd'hui une nouvelle page à la réflexion politique, en France et en Europe et touche toutes les classes et toutes les générations, car les enfants du siècle ne combattent plus pour la vertu ou pour la patrie, mais pour le pacifisme, les migrations illégales ou les droits de l'homme.

Régimes égalitaristes et régimes hiérarchiques

En effet le changement de paradigmes a fait tourner la page de l'égalité, du bonheur et des désirs des citoyens, qui avaient constitué autrefois les piments de l'utopie.

L'époque contemporaine est particulièrement touchée par une revendication d'uniformité et d'hostilité à l'ordre établi et par une réceptivité désarmante vis à vis des vitupérations et des demandes sociales. En effet ces dernières laissent un grand espace à la disponibilités des masses pour croire aux nouvelles prophéties et au vieilles lubies égalitaristes.

Ces masses, qui ne font plus confiance à des philosophies salvatrices, fussent-elles dialectiques et qui ont quitté les partis politiques, constituent le terrain de chasse privilégiées de l'intime corruption de la démocratie, l'apolitisme et la logique des privilèges, apanage des parvenus et des arrivistes.

Celle-ci constitue la semonce captivante de tous les courants et de tous les hommes, qui vendent sur la scène politico-médiatique, leurs alchimies du renouveau et des promesses, non certifiées, du futur.

L'aveuglement dans la fiction de l'égalité s'est particulièrement développée au sein de l'opposition entre les deux camps, de la société civile et de la société politique, autrement dit de la fraternité introuvable et de la rivalité irréductible, en corrompant au même temps l'idée d'Europe.

La souveraineté et ses interprètes, Tocqueville, Rousseau et C.Schmitt

La souveraineté et ses interprètes, Tocqueville, Rousseau et C.Schmitt

Avec l'évolution des systèmes de pouvoir contemporains, la dictature des majorités, que Tocqueville craignait venir de l'uniformisation des conditions en Amérique se renverse de nos jours en la tyrannie des minorités, puissamment portées par la désagrégation de la vie sociale et la corruption de la vie parlementaire. En effet si la tyrannie de la majorité a pu apparaître jadis menaçante, la phénoménologie contemporaine prouve que ce sont les revendications minoritaires à afficher le plus grand danger pour le bien commun.

Ce sont en outre les minorités qui prétendent dissoudre le concept de "genre", ou de "nature" (homme,femme), pour le soumettre totalement à celui de société, au sein d'un processus historique, qui tend vers l'égalité des citoyens.

Cette civilisation égalitariste, dans sa dimension multiculturelle entraînerait un mutation anthropologique, où les différences ne seront plus légitimes et il en résultera une nouvelle humanité, dans laquelle les minorités s’emploient à définir autrement la société et à changer les codes et les dictionnaires du langage courant, de même que les délits et les peines de la jurisprudence et de la loi et où le concept de "nature" disparaîtra par l'effet de la "volonté générale" et du "contrat démocratique".

De telle manière les revendications minoritaires , promues sous le drapeau de l'égalité, pourront dissoudre les identités nationales et les communautés d'origine.

Or, la "souveraineté" défendue par Tocqueville, comme capacité d'autonomie politique et d'auto-organisation sociétale, hors de tutelles étrangères, n' est guère la "souveraineté" de la volonté générale de Rousseau, le genevois misogyne, inspirateur de la révolution française, destructrice de tout ordre hiérarchique et père des dogmes démocratiques du républicanisme de la IIIIème République.

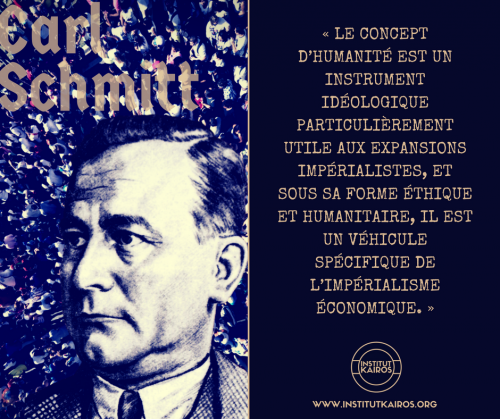

Elle n'est pas non plus celle de C.Schmitt, dernier représentant du "Jus Publicum Europaeum", penseur du décisionnisme et de la souveraineté, incombant sur "celui qui décide de l'exception, en situation d'exception". La souveraineté de Carl Schmitt, qui s'inscrit au cœur de la lutte à mort de l'ami et de l'ennemi, comme essence du politique, prône en effet, en situation de danger, l'unité de tous ceux qui se rassemblent et qui sont liés par une origine et une amitié homogènes, excluant ceux qui sont étrangers à l'ordre politique national et se comptent aujourd'hui par millions.

Macron, la France et l'Europe

Macron, la France et l'Europe

Or, dans l'hypothèse de crises plus violentes,la faiblesse de Macron et la dissolution de la France et de l'esprit français s'inscrivent dans l'impossible conciliation, au cœur l'unité "indivisible" de la nation, de l'universalisme extrémiste et de l'immigrationnisme débridé du Prince. Conciliation politique et institutionnelle qui exigerait la soumission de tous au pouvoir régalien, afin d'assurer la paix civile, face à la menace latente de la désunion et de la subversion internes.

Personne n'osera réduire la démocratie au seul suffrage, fût il plébiscitaire, ni le suffrage à la divinisation du peuple, fût-il le "peuple élu".

Selon l'institution monarchique, réhabilitée par la république présidentielle, un peuple n'est uni que sous son souverain, seul en mesure d'assurer la concorde civile.

Mais le péché historique de la France, c'est d'avoir brisé l'unité de la nation, à l'époque de la Réforme protestante vis à vis des Huguenots et de leurs collusions supposées avec la Hollande et l'Angleterre, hier avec le Front Populaire et l'Union Soviétique et après la guerre, avec les socialismes et les pays de l'Est, aujourd'hui avec l'Islam et les États sunnites et wahhabistes, ennemis latents et permanents du pays.

Dans cette république querelleuse et insoumise la démocratie, antidote de la monarchie ou du pouvoir monocratique, a-t-elle besoin d'un chef providentiel, maître, despote, ou barbare qui s'élève au dessus des factions et incarne l'autorité et la concorde?

Au coeur de troubles et difficultés multiples, Macron tend vers un point d'équilibre entre l'ordre libéral global et l'égalitarisme islamo-libertaire, ou encore, entre la modernité administrative et les nouvelles aristocraties républicaines.

En tant qu'expression des bourgeoisies françaises de droite et de gauche, il ne peut conjuguer l'inimitable exaltation pour la primauté de l'Amérique de Trump et le caractère russe de Poutine.

S'il lui est impossible d'intégrer ou d'anéantir l'Angleterre, tournée vers le grand large, Macron tâche de voir dans le Brexit une occasion de nouer avec l'Espagne et de prendre à revers les pays de Visegrad, par une politique d'entente avec la Serbie et les Balkans Occidentaux,en humiliant l'Italie,qui sera le premier rebel du giron des pays subordonnés au joug de l'Union germano-américaine.

C'est la peur d'une surprise stratégique d'ampleur historique, la révolte islamique, qui lui interdit de reconnaître dans l'ennemi intérieur le perdant de la bataille de Roncevaux, qui marche désormais sur les Champs Élysée.

De surcroît et par un coup de poker, après avoir affronté les gilets jaunes et guillotiné le vieux système des partis, Macron est apparu en Europe, après les élections, comme le seul faiseur de rois et le seul créateur de légitimité vis à vis des institutions européennes.

L'accord de compromis avec une Merkel sans vision et sans avenir, pousse la France de Macron vers un modèle de société autoritaire, sans lui éviter de devenir, face à une Allemagne à l'hégémonie réluctante, la plus importante province du sacrée romain empire germanique, version post-moderne.

Par ailleurs l'approche rajeunie de la concertation franco-allemande, pourra-t-elle rester le pivot d'une asymétrie stabilisée et définitivement acquise , ou bien deviendra-t-elle le soutien principal d'un jeu de bascule du leadership, porté par un homme, qui s'est forgé une image iconoclaste de la liberté des peuples et du pouvoir des États?

La démocratie est elle en danger?

L'effondrement de la social-démocratie en Europe et la politique néo-libérale ,visant à absorber l'électorat conservateur, s'exprime en France par une pratique de restriction du contrôle parlementaire. La crainte de déstabilisation du pouvoir est le principal fondement de l'autoritarisme d’État. Puisque l'appareil d’État s'est évanoui face à la triangulation instable, d'une gauche affaiblie et d'une droite attirée par le Rassemblement National, le centre accapareur de Macron, dépourvu d'une base sociale propre, glisse vers une politique néo-libérale de type autoritaire, dans le but de rendre impossible une compétition électorale "équitable" et de puiser dans le réservoir électoral des droites conservatrices.

Pour atteindre cet objectif, le mécanisme électoral de la cinquième république donne au regroupement politique gagnant, un poids politique disproportionné dans les instances représentatives. Face à une opposition éclatée, à une presse largement favorable et à des médias qui totalisent des parts d'audience considérables, lui permettant de régner sans partage,la seule figure absente est, comme il le dit en 2015, "la figure du Roi".

D'où son modèle monarchique et son mépris du peuple. Dans cette situation la transformation de la France en exemple de l'Europe, s'inscrit dans l'approfondissement du néo-libéralisme et dans une réforme du droit du travail,"flexibilisé", suivant les recommandations du FMI et de l'OCDE. "There is no other choice", expliquera-t-il dans une interview à la presse anglo-saxonne. Or, à l'échelle internationale, l'enjeu du siècle pour la France, comme pour l'Europe est la transformation du monde par la révolution scientifique et technique. Ainsi, le but de la France de demain est de devenir "une Start Up nation". Cependant, au ralentissement de la croissance et au caractère de plus en plus insupportable des inégalités, la stratégie du pouvoir évolue vers la réalisation de réformes structurelles, qui puissent favoriser, coûte que coûte,la compétitivité du pays. Le succès de ce chantier de réformes repose sur une grande fusion des nano-technologies, bio-technologies, réseaux intelligents et objets connectés. La République en marche, dans l'esprit du Prince, devient le synonyme d'un monde en marche vers l'avenir.

La dérive autoritaire de la démocratie

Le stimulant de ce nouvel horizon technologique est le succès des "meilleurs".

Or, l'obstacle le plus préoccupant de cette démarche générale est l'extension des inégalités, à surmonter par un autoritarisme déclaré, qui délaisse "le bavardage législatif", par une limitation des débats parlementaires, l'adoption de procédures accélérées pour l'examen des projets de loi, la restriction du contrôle parlementaire, le "secret des affaires" et une marge de manœuvre de plus en plus large de l'appareil répressif et des forces de l'ordre. A titre de rappel, la demande au Parlement de la part du président Macron d'adopter une loi qui limite la liberté de manifestation et la présomption d'innocence. Cette politique dure, dangereuse et risquée est ce que l'on peut définir comme la dérive autoritaire de la démocratie et la preuve irréfutable de son étouffement.

L'affaiblissement de l'esprit de liberté et la transformation de l’État démocratique en l’État bureaucratique.

Sur le rôle de la "Formule politique"

In fine, la référence classique de toute tentation autoritaire demeure l'affaiblissement de l'esprit de liberté, qui se mesure aujourd'hui aux dispositions de plus en plus restrictives sur le désaccord politique. C'est de cet affaiblissement que meurent partout les démocraties modernes. Certains parleront de lois liberticides, à propos de la liberté d'expression, d'autres de censure sournoise, d'auto-censure, de chasse aux sorcières, ou de manipulations médiatiques.

En effet, cela se produit lorsque la méfiance, le pessimisme ou la peur de l'ennemi politique s'infiltrent dans nos craintes collectives et c'est là que la liberté se meurt et décline. Les régimes de liberté se meurent également de la désagrégation de la "formule politique", autrement dit du ciment moral, de la croyance collective et de la volonté présumée d'un peuple, de pouvoir surmonter les épreuves de l'Histoire, en s'appuyant sur la fidélité à une tradition ou sur la confiance à un chef providentiel. La désagrégation de ce moment de grâce jette un éclairage sur les difficultés d'une situation, bloquée par une impasse de nature politique ou intellectuelle et qui, en harmonie avec l'esprit du temps, avait permis la mobilisation collective autour d'un projet de renouveau, soufflant au même temps dans le cœur de chaque citoyen.

Ce fut le cas des résistances à l'occupation allemande et à la reconstruction nationale.porteuses de grands espoirs de libertés.

Ce n'est plus le cas d'aujourd'hui, où la "formule politique" se grippe dans la transformation du pouvoir en régime autoritaire, engageant la mutation des États démocratiques en États bureaucratiques, des États dans lesquels ils est interdit de penser et d'avancer, car il ne faut qu'appliquer.

Le cas exemplaire est celui des institutions supra-nationales comme l'Union Européenne, à la double légitimité, nationale ou populaire et supra-nationale ou oligarchique.

Ici le problème non résolu est celui du renouvellement des élites de direction, les "top jobs", en situation de mixité et de jonction des formes d’État et des formes de régimes.

Dans ce cas la "formule" (alliance ou compromis), doit garantir la fonction d'équilibre entre les impulsions stratégiques des Chefs d’États et de Gouvernement (légitimité étatique ou oligarchique) et les responsabilités d'exécution des bureaucraties supra-nationales (légitimité hiérarchique, et, en son aspect confirmatif, démocratique).

La "Formule politique" doit trouver ici la clé de la compatibilité institutionnelle entre l'option autocratique (désignation par le haut) et l'option démocratique (confirmation par le bas).

Il semble évident, dans des conditions si restrictives, que le recrutement des nouvelles élites laisse une marge de manœuvre très réduite aux nouveaux dirigeants et les rend davantage tributaires d'une "aquiescence" hiérarchique, qui les éloigne des revendications des peuples, en restreignant leur autonomie de jugement et en éteignant leur conscience historique.

Cette incompatibilité des deux niveaux de la représentation et de la légitimité engendrera une énième difficulté en situation de conflit civil ou militaire, car la différente composition, de structure et d'idéologie, des partis politiques nationaux, opposera les différentes formations politiques, à base ethnique et à idéologie racialiste fort dissemblables, tant à l'échelle européenne que dans le domaine de la politique étrangère et de sécurité.

Guerre et liberté

La prévisibilité d'un conflit désigne une situation dans laquelle on peut cerner la valeur de la liberté, entendue comme principe de gouvernement.En effet l'anticipation d'un danger réunit et symbolise toutes les autres formes de libertés et tout ordonnancement des activités humaines.

Le conflit civil aux portes, où sera jouée la liberté française et européenne, ainsi que leurs régimes politiques, n'est pas seulement un affrontement de tendances, où s'expriment les formes de soumission de l'humanité aux grands cycles historiques de la paix et de la guerre, mais une lutte à mort entre deux peuples et deux civilisations hostiles, vivant en cohabitation forcée, le peuple de souche et la civilisation française d'une part et les immigrés et la civilisation de l'Islam de l'autre, sur un même sol métropolitain à conquérir, la terre des Francs.

Ce conflit s'exprime par des manifestations multiples d'insoumission, de révolte, de violence symbolique, de rejet intellectuel et moral, de haïne et de mépris déclarés.

Or la liberté de tout un peuple est un enjeu à gagner à chaque instant, car la préservation de la paix est le but principal d'un gouvernement. Le paradoxe français est que beaucoup de politiciens et d'intellectuels ,en bons héritiers du rationalisme cartésien, ne partent pas des faits et des constats pour s"élever au monde des idées et aux grandes proclamations idéologiques, mais prétendent établir, en humanistes cosmopolitiques, un équilibre humain rationnel, fondé sur un dialogue et une entente utopiques, plutôt qu'un équilibre humain naturel, enraciné sur un antagonisme profond, entre les deux âmes du pays. Ce procédé intellectuel est un suicide ou un acte génocidaire, car il accorde à l'ennemi l'espoir d' une victoire à la portée

Au plan historique le déferlement de migrants et de leurs progéniture ont autant d'importance, si non plus grande, que les ambitions ou la gloire des princes. Or le Prince, incapable comme tout homme de tenir le juste milieu, penche raisonnablement vers l'illusion d'une impossible concorde civile.

Lui, et avec lui, les autres gouvernants d'Europe, à commencer par M.me Merkel, ne pensent pas, suivant Machiavel, de pouvoir gouverner la moitié de leurs œuvres, qui relèvent de leur "Virtù", puisque ils ne peuvent maîtriser l'autre moitié, qui est assignée à la "Fortuna", ou au Hasard.

Par ailleurs, du point de vue de la politique mondiale, ils n'arrivent pas à partager l'idée kantienne, que le conflit et la guerre "se greffent sur la nature humaine" et que la forme d'éthique la plus élevé, consiste à dominer cette causalité d'origine (différenciations de société), comme fondement du gouvernement des hommes (hostilité politique).

Les esprits de ces gouvernants sont dominés par l'individualisme moral et l'illusion du cosmopolitisme, qui sont les deux visages d'un même renoncement,à la logique de la raison ou à celle de l'histoire.Au sein du couple franco-allemand cette antinomie se manifeste par l'obsession d'un discours sur les valeurs, sans substance éthique, qui ne tolère pas de répliques et de dissensions et qui freine la liberté des débats. Les représentants de ce couple feignent d'ignorer que la relation de peuple à peuple est une relation d'inimitié et donc de guerre. Cette relation est ainsi occultée et refoulée et alimente les dérapages de la pensée unique, de telle sorte qu'elle obscurcit la capacité de discerner l'essentiel (la lutte politique), de l'accessoire (la concorde civile) et l'amour pour l'ordre des excès violents de la liberté.

Devant les deux formes d'Histoires qui sont devant nos yeux d'européens, l'Histoire de la conscience et l'Histoire réelle, la première, dans le langage de l'Union, prend la forme idéologique de l'apologie et la deuxième celle, dramatique, des antagonismes, qui sont à la racine des choix mortels de l'Union.

Sur la crise des démocratie et l’évolution vers des régimes autoritaires

Si les démocraties occidentales évoluent vers des régimes autoritaires, c'est que l'on peut identifier dans ce cheminement plusieurs parcours.

Le premier et le plus important est la crise des systèmes représentatifs, fondés sur la légitimation du pouvoir par le suffrage, sur le système des contre- pouvoirs ( la balance of power) et sur un corpus acquis d'assurances de libertés. Or, bon nombre de polémistes, (S. Levtssky, D. Ziblatt, D. Runciman, Y. Mounk) revendiquent le recours à un même paradoxe; l'utilisation des institutions démocratiques de la part des détenteurs des pouvoirs globaux, pour mieux dénier la volonté populaire, ou sa fiction.

Les moyens pour y parvenir sont la montée en puissance de la manipulation, la "désinformation" et la constitution d'un réseau d'outils de surveillance, perfectionnés et sournois, pour contrôler et prévenir une remise en cause des positions dominantes.

C'est à ce point qu'une interrogation rapproche singulièrement ces auteurs, celle d'un questionnement commun et capital:

"Comment meurent les démocraties"

Après avoir décrit les moyens et les méthodes des nouveaux fauteurs de l'économie numérique, ces auteurs soulignent l'importance croissante de l'autorité immuable de l'administration des choses, qui pousse à la création d'un État autoritaire, sur une base organisationnelle à caractère numérique.

États et violence politique

Il y a des signes qui ne trahissent pas, la neutralisation des consciences, la dépolitisation de la vie publique et l'élargissement de la censure, bien au delà des dispositions législatives et des enjeux de politique immédiate, préfigurant une véritable "police de la pensée".

Or, si les démocraties évoluent vers des régimes autoritaires derrière des formes d'un pluralisme de façade, c'est que la limitation des libertés d'expression est l'une des preuves de l'intolérance vers les dissensions et que la confiscation du pouvoir se cache derrière le contrôle étroit de l'appareil d’État.

En effet, l' intrusion opaque du pouvoir bureaucratique prend une place nouvelle dans l'innovation technologique, sous la pression de la radicalisation de la société et des conditions de guerre civile, dans lesquelles se répandent des formes de violence spécifiques, celles du terrorisme islamique, de l'insoumission populaire et des réseaux sociaux.

Cette convergence des formes de la violence, interne et extérieure, crée les conditions d'une escalade, qui affaiblit l'autorité du pouvoir, la légitimité des ripostes et la stabilité des régimes politiques, mettant en échec les institutions et les procédures de l’État de droit.

Dans cette situation, une partie considérable de l'establishment intellectuel pointe du doigt les différentes phénoménologies de la crise et identifie sa causalité prioritaire dans un populisme montant, responsable, dans leur lecture, de la dislocation de l'ordre libéral, au moyen de coalitions anti-système de plus en plus vigoureuses.

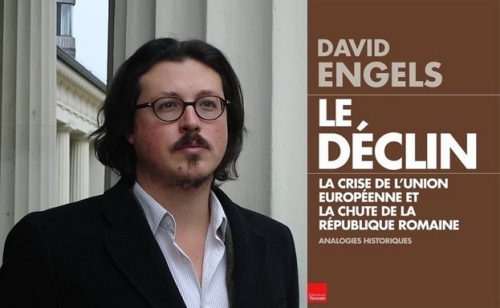

D'autres voient dans cette crise une double corrélation, celle de la place prépondérante du multipolarisme dans les relations internationales et celle du sinistre rattrapage du passé sur le présent. En particulier, de la grande crise européenne des années trente, dont un présage troublant serait à voir dans le Brexit.

Les menaces portées contre la démocratie: un tabou de la communication politique

Or, contrairement à ces Cassandres, le probable "vrai" danger qui menace les démocraties est le tabou, entretenu par la pensée unique sur l'Islam, le terrorisme islamique et la révolte croissante des populations musulmanes installées en Europe et en Occident, dont la guerre proclamée, le djihad, prendra bientôt la forme tragique d'une "surprise stratégique".

Le défi de la guerre civile imminente n'est pas atténué par l'absence, chez les musulmans, d'une conscience collective organisée ou d'un discours révolutionnaire explicite et cohérent, comme cela s'est produit aux États-Unis dans les années cinquante/soixante avec MalcomX et Martin Luther King, les deux leaders historiques de la révolte violente et de l'integrationnisme pacifique. L'absence de réflexion sur leurs conditions d'assistés en France ou en Europe, interdit aux intellectuels musulmans d'aller au delà d'une sorte d'agnosticisme moral et d'un malaise psychologique, qui les prive de l'énergie et de la responsabilité d'un engagement citoyen, de la carence d'un Leader charismatique et du mythe d'un combat mobilisateur pour la liberté et pour l'affranchissement de leur marginalité et de leur subordination endémique.

La raison en est le manque de courage intellectuel et la crainte d'une "vendetta" raciale.

L' absence des musulmans du système politique, en tant qu'entité sociologique aux intérêts propres, déclasse toute une communauté de la bataille politique et parlementaire et pousse le système représentatif vers un autoritarisme hypocrite dans le meilleur des cas, et vers l’extrémisme nationaliste et raciste dans l'autre.

L'apartheid incomplet de cette communauté ne peut être combattu ni au nom de la liberté, ni au nom de l'intérêt général, car il fonde l'équivoque d'une condition ambiguë sur les concessions accordées par une partie du système politique, les socialistes et les démocrates "sincères", qui veulent profiter d'une clientèle à leur botte sans soumission à l’État républicain.

La recherche d'un ordre alternatif

De surcroît, si la désillusion de la démocratie et le retour du réalisme sont évidents, un autre facteur puissant vers des formules politiques autoritaires est représenté par la révolution de l'intelligence et par l'intelligence artificielle dans la vie politique et sociale contemporaines.

D'où viennent-elles la post-démocratie, la contestation du Leadership occidental dans le monde et la recherche d'un ordre alternatif qui s'oppose au progressisme sociétal et au néo- libéralisme de la France et de certains pays européens ?

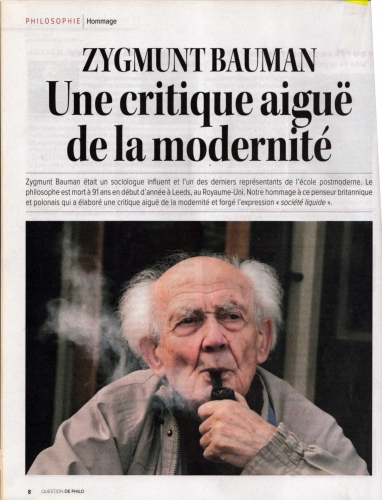

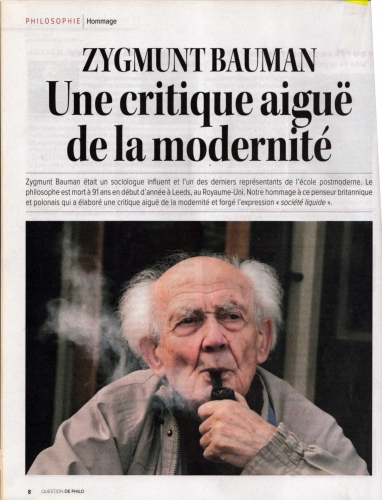

Sous couvert de "raison", dira-t-on, les démocraties de l’Ouest se sont nourries d'une logique de "déraison" qui a théorisé et pratiqué le sens de la démesure et l'extension continue des droits sans devoirs. Cet outrage du "bon sens" a conduit au dépassement des " limites" de l’État, de la Nation, de la famille et de l'anthropologie, et à l'égarement de "l'affectio sociétatis", propres des sociétés homogènes, aboutissant à la "société liquide" de Zygmunt Bauman.

Sous couvert de "raison", dira-t-on, les démocraties de l’Ouest se sont nourries d'une logique de "déraison" qui a théorisé et pratiqué le sens de la démesure et l'extension continue des droits sans devoirs. Cet outrage du "bon sens" a conduit au dépassement des " limites" de l’État, de la Nation, de la famille et de l'anthropologie, et à l'égarement de "l'affectio sociétatis", propres des sociétés homogènes, aboutissant à la "société liquide" de Zygmunt Bauman.

Cette dernière s'opposerait à la société moderne, guidée par un projet commun et par un univers de "sens" partagé, car dans la société liquide les relations sociales sont impalpables, précaires et presque impossibles. Par ailleurs l'individu doit s'adapter à une liberté incertaine et la ville devient une montagne de zones de pauvreté et de récupération. La vulnérabilité de ce monde aliéné serait mise en lumière par la métaphore du monde global, où la télé-réalité apparaît comme la mise en scène de la "jetabilité, de l'interchangeabilité et l'exclusion", bref, comme la précarisation de toutes les conditions de vie.

Essor et évolution des régimes autoritaires en Europe

L'évolution actuelle vers des régimes autoritaires en Europe est imputable plus à une transformation interne des démocraties qu'à un retournement violent de la conjoncture politique.Elle peut être liée, en ses origines, à l'essor des espoirs de renouveau des années 1990, caractérisés par l'inclusion dans la vie publique des groupes dissidents ou minoritaires (ethniques, religieux et sexuels), et quant à la situation actuelle, à la tentative de consolidation des majorités menacées et à la décomposition des partis traditionnels. Cette évolution impose la recherche d'institutions adaptées et d'un nouvel ordre politique. A la lumière du présent, l'opinion publique devient conservatrice, la radicalisation des forces modérées et des classes moyennes, un phénomène étendu et l'essor du populisme, inquiétant. En réalité nous assistons à une intensification des stratégies conservatrices plus que populistes, puisque les clivages qui se dessinent sont tracés par trois vulnérabilités immanentes, celles de la sécurité, de l’invasion migratoire et de la démographie déclinante. Ces vulnérabilités, en dessous des slogans électoraux, imposent une polarisation idéologique inédite et un renouveau des droites européennes, qui ont pour base le cadre de la lutte antiterroriste, la critique des élites urbaines et l'hostilité à la bureaucratisation autoritaire de l'Union européenne, qui ne représente plus l'union des États, ni la défense des peuples du continent . Face à cette levée des boucliers, sommes nous en présence d'une révolte passagère et sans doctrine, ou à une véritable "révolution néo-conservatrice"? Pouvons nous comparer cet âge du doute et du bilan historique à la révolution néo-conservatrice américaine et à la pensée allemande des années 1920/30?

L'élément de fond apparaît ici la transformation commune des vieux conservatismes en doctrines révolutionnaires de la société. Ici encore, le caractère schmittien du renouveau européen est dans la redécouverte de la politique comme critique du libéralisme, une doctrine qui ignore l’État, la souveraineté et la sécurité, au profit d'un moralisme individualiste et d'un progressisme social. Qui fait de la "norme juridique" le référent principal des conduites, privées et publiques; normes qui sont toujours politiques et jamais neutres.

La "Nouvelle Frontière" de l'Europe, le Souverainisme

Ainsi la "Nouvelle Frontière" des droites européennes n'est pas le populisme, mais le Souverainisme et, affectivement, le Patriotisme, comme conscience de la tradition, de la permanence et du "nomos"de la terre.

Ce Souverainisme, qui marque un retour à l’État, ne divinise pas la concurrence, point-clé du néo-libéralisme moderne, car aucun État ne peut tolérer en son sein des entités, nationales ou étrangères, qui concurrencent son pouvoir.

En ce sens l’État politique est l’État qui décide et qui gouverne, un État qui vit dans la grande politique et qui assume celle-ci dans son intégralité, car la politique est lutte, lutte pour le pouvoir et la puissance, lutte pour la domination et la survie, lutte implacable pour sa propre affirmation historique et pour la soumission de l'ennemi à sa vision du monde.

Ainsi le Souverainisme n'est pas un populisme, puisqu'il n'est pas une promesse, mais une volonté ; il n'est pas la critique des élites, mais la revendication d'un destin.

Ainsi le Souverainisme n'est pas un populisme, puisqu'il n'est pas une promesse, mais une volonté ; il n'est pas la critique des élites, mais la revendication d'un destin.

Le renouveau intellectuel des droites européennes, à la lumière de la révolution néo-conservatrice américaine et de la pensée allemande de la République de Weimer, revient sans cesse sur l'irréductible dualité du politique, l'antagonisme de l'ami et de l'ennemi, dans l'approche du pouvoir, de sa conquête et de son maintien.

Rien à voir avec le "statu-quo" ou la simple légitimation par le suffrage. Rien à voir avec les compromis et les accommodements.

La lutte pour le pouvoir n'a de sens qu'en elle même et pour la conquête et la conservation du pouvoir en tant que tel, brutalement, avec la force, la violence verbale et l'affrontement physique

Le souverainisme est une idée-force, qui ne craint pas la bataille des idées et il ne redoute nullement l'action, car il s'en nourrit.

S'il comprend l'appétit naturel des hommes pour l'état civil et pour la paix, érigé en postulat moral, le souverainisme ne peut partager l'inversion du concept westphalien d’État.

Le souverainisme privilégie l’État qui gouverne et l'État-stratège et refuse les démocraties désarmées.

Dès lors ,il ne peut être qu'en rupture avec l'Europe du "statu-quo", avec la dépolitisation de la conscience européenne et avec la neutralité culturelle générale, dont "l’État agnostique et laïc", est l'expression emblématique.

Ainsi et à ce stade il s'insurge contre toutes les conceptualisations qui identifient dans l'Europe de l'Union une figure politique de la post-modernité, un État sans État, une politique sans politique, un pouvoir sans autorité, une désacralisation sans légitimité; une forme d’État sans sujets, car l'idée même de citoyen se traduit en un concept vide et totalement désincarné.

La radicalisation européenne, dont l'impact n'est qu'à ses débuts, se fera sur le sentiment de révolte et de vulnérabilité des peuples trahis et découlera logiquement de l'invasion migratoire, du Brexit et des luttes anti-islamiques.

En termes collatéraux, sur les questions de moralité traditionnelle (gendre, mariages homosexuels et IVG).

Quelle est la nature philosophique de cette évolution vers des régimes autoritaires, et leur "nécessité"? Un des facteurs déterminants repose sur le fait que les élites mondialistes sont en posture défensive et soutiennent une démocratie déclinante et corrompue et que l'ascendant des droites radicales compte sur un foisonnement intellectuel cohérent et adapté et sur l'indignation de ses militants qui n'hésitent pas à se battre.

On ajoutera à ces considérations, l'influence de l'école réaliste et de ses grands maîtres à penser, Machiavel, Hobbes, Weber, Schmitt, Strauss, Kissinger et la critique de la conception libérale et humaniste du pouvoir et de la puissance.

En termes cognitifs, la distinction majeure de la politique et du pouvoir n'est pas la poursuite de la moralité ou de la justice, mais la lutte pour la vie et l'affrontement existentiel, qui constituent les formes les plus intenses des antagonismes nationaux. Sous ce prisme, discriminant, le libéralisme, l'humanisme et les différents juridismes sont trompeurs et en porte à faux par rapport à la réalité effective des relations d'homme à homme et de société à société.

Ce bouleversement cognitif est inacceptable pour les détenteurs des privilèges, les élites bureaucratiques et globalistes, qui ont choisi la ligne de la récusation et du négationnisme et font abus d'autorité dans le conflit civil. C'est dans l'évolution contestée des démocraties déclinantes, que le pluralisme de la société civile montre son visage illusoire et son rôle concurrent par rapport au Politique et à l’État, dans la transition vers des formes politiques originales.

Souverainisme et populisme. Stratégie et tactique

L'insistance sur le rôle de la société civile de la part de la doctrine officielle, comme pouvoir compensateur, est lié à l'institution de la démocratie, fondée sur la logique des contre-pouvoirs (checks and balances), qui, en théorie, freine et limite l'exécutif dans le but d'éviter l'installation d'un pouvoir despotique ou tyrannique. Une balance qui entrave de toutes ses forces l'émergence de l’État total. L'intensification des stratégies souverainistes et néo-conservatrices en Europe fait évoluer le système vers la droite des hémicycles parlementaires et vers les extrêmes du mécontentement et de la révolte des rues et des carrefours, car la France et les autres pays européens sont taraudés par l'épuisement du "statu quo" et de l'idée-guide de l'Union.

Ainsi, si la critique des élites est une tactique doctrinale qui vise la prise en charge de l'homme ordinaire( populisme),le souverainisme est une stratégie de nature parlementaire et plébiscitaire, qui bouleverse les pratiques et les appareils des échiquiers nationaux. De façon générale, là où les libéraux et les progressistes tendent à modérer les débats,à restreindre les libertés et à manipuler l'information, les souverainistes de tout bord, relancent en permanence les affrontements, pour dénoncer les campagnes adverses, montées de toutes pièces sur la base de fake-news, dont l’objectif déclarée est de dévoiler aux opinions les misères et les turpitudes du "Roy nu" et des pouvoirs oligarchiques. Cependant, l'ombre redoutable portée par le passé sur le présent maintiendra son caractère de menace, plus que de danger imminent, jusqu'au moment où le souverainisme, actuellement sans leadership et sans mythes, sans gardes rouges et sans une avant-garde bolchevique, ne se dotera d'un ascétisme révolutionnaire résolu et sévère, dans le but de servir l'indépendance et la liberté du peuple.

La révolution numérique et le contrôle social

La transformation de la démocratie post-moderne en technocratie et en régimes autoritaires n'est pas un phénomène isolé, mais un des facteurs du processus historique,de plus en plus irréversible, que l'on a désigné comme le déclin de l'Occident, dont les signes manifestes sont par ailleurs, l'immigration destructrice de sous-hommes, le vieillissement des populations et la désagrégation de l'Europe et des États-Nations.

D'autres raisons de cette progression palpable, qui ne s'arrête pas aux frontières du politique et le transcende, préfigurant, selon certains, une révolution politique, ce sont les raisons du contrôle et du numérique, imputables à l'espace du Web et aux réseaux de la toile.

Penser la société en termes de réseaux signifie-t-il encore la penser en termes de complexité et de projet collectif ou la dissoudre dans un ensemble à base individualiste, qui comporte une dispersion de la souveraineté politique et une organisation de sujets démunis, autour d'une communication globalisée, pilotée de l'extérieur et vulnérable aux ruptures stratégiques?

Dans ce questionnement ne sont plus évoqués ni les problèmes d'une communauté à gouverner, ni les ambitions d'un destin à affermir.

Par ailleurs internet est devenu un vecteur d' idées politiques et un nouvel espace du débat, sans perdre ses caractéristiques de lieu, de moyen et d'englobant systémique et informel et, de ce fait, sans pouvoir éliminer, ni atténuer les différences de société à société et de culture à culture.

Les fondements philosophiques d'Orient et d'Occident confirment la distance des civilisations politiques dans deux pays aussi opposés et aussi significatifs que sont la France et la Chine, en ce qui concerne le fichage informatique et le contrôle numérique des populations: dans la première, pour garantir le maintien des libertés, dans la deuxième pour détourner les finalités de l'échange intellectuel vers des objectifs de contrôle, virtuellement totalitaire.

Un accélérateur de la marche vers des régimes autoritaires est , en particulier, le climat de soupçon et de méfiance institutionnelle, déchaînés par la chasse aux sorcières et par la recherche du boucs émissaires, servant de prétexte aux hystéries accusatoires, dans le cas d' intrusions informatiques présumées et lors de débats décisifs des campagnes électorales.

La déstabilisation des appareils politiques adverses (campagne Trump-H.Clinton, WikiLeaks), n'est ici qu'un bouleversement mineur dans le domaine de la formation des opinions et de la communication globalisée, car la volonté étrangère présumée de l'intrusion informatique apparaît comme une préférence affichée pour l''un des deux décideurs et comme une"volonté de réfutation" des argumentaires avancés par l'autre, surtout dans la redéfinition de la politique internationale et mondiale.

La coexistence de deux "paradigmes sociétaux", démocratique ou autocratique, est à l'origine de l"option entre "systèmes de consensus" (ou systèmes ouverts) et systèmes du "statu-quo" (ou systèmes fermés), autrement dit entre systèmes partisans et contradictoires (démocratie) et système aux intérêts stabilisés et homogènes (autocratie).

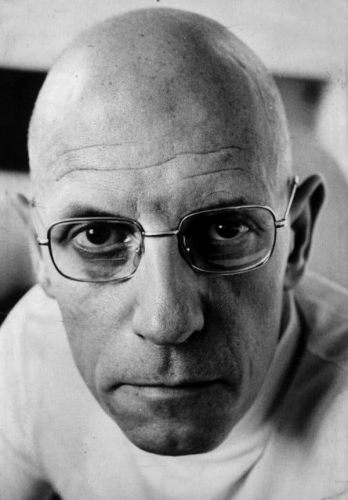

Phénomènes de normalisation, de violence et de sanction du XXIeme siècle.

Michel Foucault et sa "notion d'homme"

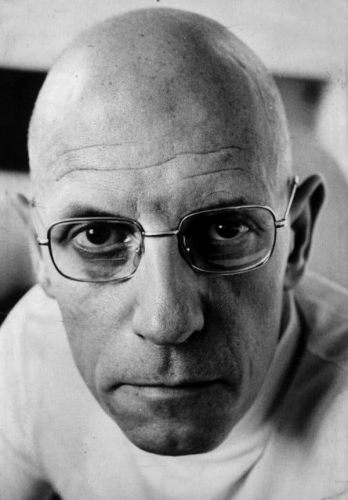

C'est en étudiant les mutations des disciplines du contrôle social aux XVIII et XIXemes siècles que Michel Foucault a dégagé sa notion "d'homme".

Il affirma, sans risque de se tromper, que: "La liberté de conscience comporte plus de dangers , que l'autorité et le despotisme". Nous dirions que les systèmes ouverts comportent infiniment plus de périls que les systèmes fermés, car ils baignent dans les marécages de la responsabilité, refusée par la plupart des damnés de la "Divine Comédie", ne pouvant s'en sortir que par la terreur de la mort.

Il affirma, sans risque de se tromper, que: "La liberté de conscience comporte plus de dangers , que l'autorité et le despotisme". Nous dirions que les systèmes ouverts comportent infiniment plus de périls que les systèmes fermés, car ils baignent dans les marécages de la responsabilité, refusée par la plupart des damnés de la "Divine Comédie", ne pouvant s'en sortir que par la terreur de la mort.

En effet la marche de la démocratie vers des régimes autoritaires est jalonnée d'embûches, de dilemmes et d'épines, auxquelles on ajoutera les tromperies et les mensonges. Dans l'herméneutique du désespoir, nous y repérons, au bout du chemin, la violence et la folie.

Face aux citoyens "dociles et utiles", l"assujettissement des modernes passe par la politique et la communication, dans lesquelles l'enfermement est tissé d'un réseaux de fake-news. Le web y fonctionne, comme le labyrinthe de Minos ou comme une clinique universelle de psychologie sociale, où se confondent les rôles des gardiens et des détenus, agissant sous le mode pervers de l'abus d'autorité, de l'intimidation, du chantage et de la peur.

Si, pour certains la société est une cage, où la violence et la sanction sont omniprésentes et par lesquelles une grande orthopédie mentale régénère les esprits, pour le peuple, les populistes et le souverainistes la société est aussi un dédale de vérités et de rachats, voire de libertés.

La folie et la mort. Le suicide d'Hamlet à Elsinor

Y a-t-il des précédents historiques à l’assujettissement volontaire de toute une civilisation et à sa soumission à un autre Dieu? Par quel mystère l'Europe accepte-t-elle son suicide, face aux nouvelles invasions,sans réagir et sans se révolter?

Qui jouent les gardiens et qui les détenus, dans la prison sociale du XXIème siècle? Les détenus, "dociles et utiles" ce sont les héritiers des empires, honteux de l'être , les vieux civilisateurs du monde.

Les gardiens des cages, les prisonniers de l'Islam, brutalisés par leurs religion et par la castration de leur vie, haletant d'une revanche dantesque.

Dans ce jeu, les vraies détenus sont devenus les esclaves de leurs propres conceptions des libertés, en se pensant les égaux de leurs bourreaux et préférant renoncer à leur condition de maîtres, face aux miroirs déformés de leurs fautes.

C'est pourquoi, indignes de vivre et perclus de leur misère, ils méritent la mort, par aveuglement et par folie ou invoquent anxieusement la dictature par une abjecte volonté de soumission.

En fait, il ne s'est jamais donné le cas que l'invasion d'une population abrutie et forte, s’accommode d'une cohabitation avec une multitude conquise,vieillissante et faible; que la haine naturelle des démunis vis à vis des nantis se soumette de bon gré et sans endurer des peines, à la discipline et au respect de leurs seigneurs, discrédités par l'inertie ou l'impuissance, dans l'usage de la force, de la cruauté et du goût de la violence; et enfin, que l'exercice de la sévice, réelle ou symbolique et, plus encore du mépris et de l'insulte,adoucis par la pitié et par la dérision, ne provoque la séduction et un secret plaisir d'humiliation et de rabaissement.

L'éducation y joue son rôle de carotte, pour le métissage culturel des petits sauvages, à leurs tour prisonniers d'un nécessaire enfermement didactique

Ainsi, face au dilemme d'Hamlet, les Européens doivent choisir lucidement entre la mort de l'autre ou leur propre suicide.

Bruxelles le 9 août 2019.

On parle beaucoup dans le monde antisystème de la chute de l’empire américain. Je m’en mêle peu parce que l’Amérique n’est pour moi pas un empire ; elle est plus que cela, elle est l’anti-civilisation, une matrice matérielle hallucinatoire, un virus mental et moral qui dévore et remplace mentalement l’humanité – musulmans, chinois et russes y compris. Elle est le cancer moral et terminal du monde moderne. Celui qui l’a le mieux montré est le cinéaste John Carpenter dans son chef-d’œuvre des années 80, They Live. Et j’ai déjà parlé de Don Siegel et de son humanité de légumes dans l’invasion des profanateurs, réalisé en 1955, année flamboyante de pamphlets antiaméricains comme La Nuit du Chasseur de Laughton, le Roi à New York de Chaplin, The Big Heat de Fritz Lang.

On parle beaucoup dans le monde antisystème de la chute de l’empire américain. Je m’en mêle peu parce que l’Amérique n’est pour moi pas un empire ; elle est plus que cela, elle est l’anti-civilisation, une matrice matérielle hallucinatoire, un virus mental et moral qui dévore et remplace mentalement l’humanité – musulmans, chinois et russes y compris. Elle est le cancer moral et terminal du monde moderne. Celui qui l’a le mieux montré est le cinéaste John Carpenter dans son chef-d’œuvre des années 80, They Live. Et j’ai déjà parlé de Don Siegel et de son humanité de légumes dans l’invasion des profanateurs, réalisé en 1955, année flamboyante de pamphlets antiaméricains comme La Nuit du Chasseur de Laughton, le Roi à New York de Chaplin, The Big Heat de Fritz Lang. Témoin donc de la désintégration de l’empire britannique causée par Churchill et Roosevelt, militaire vieille école, Glubb garde cependant une vision pragmatique et synthétique des raisons de nos décadences.

Témoin donc de la désintégration de l’empire britannique causée par Churchill et Roosevelt, militaire vieille école, Glubb garde cependant une vision pragmatique et synthétique des raisons de nos décadences.  Toutes ces causes se cumulent aujourd’hui en occident. Glubb écrit à l’époque des Rolling stones et on comprend qu’il ait été traumatisé, une kommandantur de programmation culturelle (l’institut Tavistock ?!) ayant projeté l’Angleterre dans une décadence morale, intellectuelle et matérielle à cette époque abjecte. C’est l’effarante conquête du cool dont parle le journaliste Thomas Frank. En quelques années, explique Frank notre nation (US) n’était plus la même. Idem pour la France du gaullisme, qui rompait avec le schéma guerrier, traditionnel et initiatique de la quatrième république et nous fit rentrer dans l’ère de la télé, de la consommation, des supermarchés, de salut les copains, sans oublier mai 68. Je ne suis gaulliste que géopolitiquement, pour le reste, merci… Revoyez Godard, Tati, Etaix, pour reprendre la mesure du problème gaulliste.

Toutes ces causes se cumulent aujourd’hui en occident. Glubb écrit à l’époque des Rolling stones et on comprend qu’il ait été traumatisé, une kommandantur de programmation culturelle (l’institut Tavistock ?!) ayant projeté l’Angleterre dans une décadence morale, intellectuelle et matérielle à cette époque abjecte. C’est l’effarante conquête du cool dont parle le journaliste Thomas Frank. En quelques années, explique Frank notre nation (US) n’était plus la même. Idem pour la France du gaullisme, qui rompait avec le schéma guerrier, traditionnel et initiatique de la quatrième république et nous fit rentrer dans l’ère de la télé, de la consommation, des supermarchés, de salut les copains, sans oublier mai 68. Je ne suis gaulliste que géopolitiquement, pour le reste, merci… Revoyez Godard, Tati, Etaix, pour reprendre la mesure du problème gaulliste. Détail chic pour raviver ma marotte du présent permanent, Glubb retrouve même trace des Beatles chez les califes !

Détail chic pour raviver ma marotte du présent permanent, Glubb retrouve même trace des Beatles chez les califes !

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Avant que l’on commence à se lamenter sur les décadences décrites par nos ancêtres romains et jusque par nos auteurs contemporains, et quelle que soit l’appellation qui leur fut attribuée par les critiques modernes, « nationalistes », « identitaires », « traditionalistes de la droite alternative, » « de la droite extrême » et j’en passe, il est essentiel de mentionner deux écrivains modernes qui signalèrent l’arrivée de la décadence bien que leur approche respective de son contenu et de ses causes fut très divergente. Ce sont l’Allemand Oswald Spengler avec son Déclin de l’Occident, écrit au début du XXème siècle, et le Français Arthur de Gobineau avec son gros ouvrage Essai sur l’inégalité des races humaines, écrit soixante ans plut tôt. Tous deux étaient des écrivains d’une grande culture, tous deux partageaient la même vision apocalyptique de l’Europe à venir, tous deux peuvent être appelés des pessimistes culturels avec un sens du tragique fort raffiné. Or pour le premier de ces auteurs, Spengler, la décadence est le résultat du vieillissement biologique naturel de chaque peuple sur terre, vieillissement qui l’amène à un moment historique à sa mort inévitable. Pour le second, Gobineau, la décadence est due à l’affaiblissement de la conscience raciale qui fait qu’un peuple adopte le faux altruisme tout en ouvrant les portes de la cité aux anciens ennemis, c’est-à-dire aux Autres d’une d’autre race, ce qui le conduit peu à peu à s’adonner au métissage et finalement à accepter sa propre mort. À l’instar de Gobineau, des observations à peu près similaires seront faites par des savants allemands entre les deux guerres. On doit pourtant faire ici une nette distinction entre les causes et les effets de la décadence. Le tedium vitae (fatigue de vivre), la corruption des mœurs, la débauche, l’avarice, ne sont que les effets de la disparition de la conscience raciale et non sa cause. Le mélange des races et le métissage, termes mal vus aujourd’hui par le Système et ses serviteurs, étaient désignés par Gobineau par le terme de « dégénérescence ». Selon lui, celle-ci fonctionne dorénavant, comme une machine à broyer le patrimoine génétique des peuples européens. Voici une courte citation de son livre : « Je pense donc que le mot dégénéré, s’appliquant à un peuple, doit signifier et signifie que ce peuple n’a plus la valeur intrinsèque qu’autrefois il possédait, parce qu’il n’a plus dans ses veines le même sang, dont des alliages successifs ont graduellement modifié la valeur ; autrement dit, qu’avec le même nom, il n’a pas conservé la même race que ses fondateurs ; enfin, que l’homme de la décadence, celui qu’on appelle l’homme dégénéré, est un produit différent, au point de vue ethnique, du héros des grandes époques. »

Avant que l’on commence à se lamenter sur les décadences décrites par nos ancêtres romains et jusque par nos auteurs contemporains, et quelle que soit l’appellation qui leur fut attribuée par les critiques modernes, « nationalistes », « identitaires », « traditionalistes de la droite alternative, » « de la droite extrême » et j’en passe, il est essentiel de mentionner deux écrivains modernes qui signalèrent l’arrivée de la décadence bien que leur approche respective de son contenu et de ses causes fut très divergente. Ce sont l’Allemand Oswald Spengler avec son Déclin de l’Occident, écrit au début du XXème siècle, et le Français Arthur de Gobineau avec son gros ouvrage Essai sur l’inégalité des races humaines, écrit soixante ans plut tôt. Tous deux étaient des écrivains d’une grande culture, tous deux partageaient la même vision apocalyptique de l’Europe à venir, tous deux peuvent être appelés des pessimistes culturels avec un sens du tragique fort raffiné. Or pour le premier de ces auteurs, Spengler, la décadence est le résultat du vieillissement biologique naturel de chaque peuple sur terre, vieillissement qui l’amène à un moment historique à sa mort inévitable. Pour le second, Gobineau, la décadence est due à l’affaiblissement de la conscience raciale qui fait qu’un peuple adopte le faux altruisme tout en ouvrant les portes de la cité aux anciens ennemis, c’est-à-dire aux Autres d’une d’autre race, ce qui le conduit peu à peu à s’adonner au métissage et finalement à accepter sa propre mort. À l’instar de Gobineau, des observations à peu près similaires seront faites par des savants allemands entre les deux guerres. On doit pourtant faire ici une nette distinction entre les causes et les effets de la décadence. Le tedium vitae (fatigue de vivre), la corruption des mœurs, la débauche, l’avarice, ne sont que les effets de la disparition de la conscience raciale et non sa cause. Le mélange des races et le métissage, termes mal vus aujourd’hui par le Système et ses serviteurs, étaient désignés par Gobineau par le terme de « dégénérescence ». Selon lui, celle-ci fonctionne dorénavant, comme une machine à broyer le patrimoine génétique des peuples européens. Voici une courte citation de son livre : « Je pense donc que le mot dégénéré, s’appliquant à un peuple, doit signifier et signifie que ce peuple n’a plus la valeur intrinsèque qu’autrefois il possédait, parce qu’il n’a plus dans ses veines le même sang, dont des alliages successifs ont graduellement modifié la valeur ; autrement dit, qu’avec le même nom, il n’a pas conservé la même race que ses fondateurs ; enfin, que l’homme de la décadence, celui qu’on appelle l’homme dégénéré, est un produit différent, au point de vue ethnique, du héros des grandes époques. »  L’écrivain Salluste est important à plusieurs titres. Primo, il fut le contemporain de la conjuration de Catilina, un noble romain ambitieux qui avec nombre de ses consorts de la noblesse décadente de Rome faillit renverser la république romaine et imposer la dictature. Salluste fut partisan de Jules César qui était devenu le dictateur auto-proclamé de Rome suite aux interminables guerres civiles qui avaient appauvri le fonds génétique de nombreux patriciens romains à Rome.

L’écrivain Salluste est important à plusieurs titres. Primo, il fut le contemporain de la conjuration de Catilina, un noble romain ambitieux qui avec nombre de ses consorts de la noblesse décadente de Rome faillit renverser la république romaine et imposer la dictature. Salluste fut partisan de Jules César qui était devenu le dictateur auto-proclamé de Rome suite aux interminables guerres civiles qui avaient appauvri le fonds génétique de nombreux patriciens romains à Rome. Nul doute que la crainte de l’Autre, qu’elle soit réelle ou factice, resserre les rangs d’un peuple, tout en fortifiant son homogénéité raciale et son identité culturelle. En revanche, il y a un effet négatif de la crainte des autres que l’on pouvait observer dans la Rome impériale et qu’on lit dans les écrits de Juvénal. Le sommet de l’amour des autres, ( l’ amor hostilis) ne se verra que vers la fin du XXème siècle en Europe multiculturelle. Suite à l’opulence matérielle et à la dictature du bien-être, accompagnées par la croyance à la fin de l’histoire véhiculée par les dogmes égalitaristes, on commence en Europe, peu à peu, à s’adapter aux mœurs et aux habitudes des Autres. Autrefois c’étaient Phéniciens, Juifs, Berbères, Numides, Parthes et Maghrébins et autres, combattus à l’époque romaine comme des ennemis héréditaires. Aujourd’hui, face aux nouveaux migrants non-européens, l’ancienne peur de l’Autre se manifeste chez les Blancs européens dans le mimétisme de l’altérité négative qui aboutit en règle générale à l’apprentissage du « déni de soi ». Ce déni de soi, on l’observe aujourd’hui dans la classe politique européenne et américaine à la recherche d’un ersatz pour son identité raciale blanche qui est aujourd’hui mal vue. A titre d’exemple cette nouvelle identité négative qu’on observe chez les gouvernants occidentaux modernes se manifeste par un dédoublement imitatif des mœurs des immigrés afro-asiatiques. On est également témoin de l’apprentissage de l’identité négative chez beaucoup de jeunes Blancs en train de mimer différents cultes non-européens. De plus, le renversement de la notion de « metus hostilis » en « amor hostilis » par les gouvernants européens actuels aboutit fatalement à la culture de la pénitence politique. Cette manie nationale-masochiste est surtout visible chez les actuels dirigeants allemands qui se lancent dans de grandes embrassades névrotiques avec des ressortissants afro-asiatiques et musulmans contre lesquels ils avaient mené des guerres meurtrières du VIIIe siècle dans l’Ouest européen et jusqu’au XVIIIe siècle dans l’Est européen.

Nul doute que la crainte de l’Autre, qu’elle soit réelle ou factice, resserre les rangs d’un peuple, tout en fortifiant son homogénéité raciale et son identité culturelle. En revanche, il y a un effet négatif de la crainte des autres que l’on pouvait observer dans la Rome impériale et qu’on lit dans les écrits de Juvénal. Le sommet de l’amour des autres, ( l’ amor hostilis) ne se verra que vers la fin du XXème siècle en Europe multiculturelle. Suite à l’opulence matérielle et à la dictature du bien-être, accompagnées par la croyance à la fin de l’histoire véhiculée par les dogmes égalitaristes, on commence en Europe, peu à peu, à s’adapter aux mœurs et aux habitudes des Autres. Autrefois c’étaient Phéniciens, Juifs, Berbères, Numides, Parthes et Maghrébins et autres, combattus à l’époque romaine comme des ennemis héréditaires. Aujourd’hui, face aux nouveaux migrants non-européens, l’ancienne peur de l’Autre se manifeste chez les Blancs européens dans le mimétisme de l’altérité négative qui aboutit en règle générale à l’apprentissage du « déni de soi ». Ce déni de soi, on l’observe aujourd’hui dans la classe politique européenne et américaine à la recherche d’un ersatz pour son identité raciale blanche qui est aujourd’hui mal vue. A titre d’exemple cette nouvelle identité négative qu’on observe chez les gouvernants occidentaux modernes se manifeste par un dédoublement imitatif des mœurs des immigrés afro-asiatiques. On est également témoin de l’apprentissage de l’identité négative chez beaucoup de jeunes Blancs en train de mimer différents cultes non-européens. De plus, le renversement de la notion de « metus hostilis » en « amor hostilis » par les gouvernants européens actuels aboutit fatalement à la culture de la pénitence politique. Cette manie nationale-masochiste est surtout visible chez les actuels dirigeants allemands qui se lancent dans de grandes embrassades névrotiques avec des ressortissants afro-asiatiques et musulmans contre lesquels ils avaient mené des guerres meurtrières du VIIIe siècle dans l’Ouest européen et jusqu’au XVIIIe siècle dans l’Est européen. Les lignes de Juvénal sont écrites en hexamètres dactyliques ce qui veut dire en gros un usage d’échanges rythmiques entre syllabes brèves ou longues qui fournissent à chacune de ses satires une tonalité dramatique et théâtrale qui était très à la mode chez les Anciens y compris chez Homère dans ses épopées. À l’hexamètre latin, le traducteur français a substitué les mètres syllabiques rimés qui ont fort bien capturé le sarcasme désabusé de l’original de Juvénal. On est tenté de qualifier Juvénal de Louis Ferdinand Céline de l‘Antiquité. Dans sa fameuse VIème satire, qui s’intitule Les Femmes, Juvénal décrit la prolifération de charlatans venus à Rome d’Asie et d’Orient et qui introduisent dans les mœurs romaines la mode de la zoophilie et de la pédophilie et d’autres vices. Le langage de Juvénal décrivant les perversions sexuelles importées à Rome par des nouveaux venues asiatiques et africains ferait même honte aux producteurs d’Hollywood aujourd’hui. Voici quelques-uns de ses vers traduits en français, de manière soignés car destinés aujourd’hui au grand public :

Les lignes de Juvénal sont écrites en hexamètres dactyliques ce qui veut dire en gros un usage d’échanges rythmiques entre syllabes brèves ou longues qui fournissent à chacune de ses satires une tonalité dramatique et théâtrale qui était très à la mode chez les Anciens y compris chez Homère dans ses épopées. À l’hexamètre latin, le traducteur français a substitué les mètres syllabiques rimés qui ont fort bien capturé le sarcasme désabusé de l’original de Juvénal. On est tenté de qualifier Juvénal de Louis Ferdinand Céline de l‘Antiquité. Dans sa fameuse VIème satire, qui s’intitule Les Femmes, Juvénal décrit la prolifération de charlatans venus à Rome d’Asie et d’Orient et qui introduisent dans les mœurs romaines la mode de la zoophilie et de la pédophilie et d’autres vices. Le langage de Juvénal décrivant les perversions sexuelles importées à Rome par des nouveaux venues asiatiques et africains ferait même honte aux producteurs d’Hollywood aujourd’hui. Voici quelques-uns de ses vers traduits en français, de manière soignés car destinés aujourd’hui au grand public :

1969 promovierte Sander bei Hans-Joachim Schoeps in Erlangen zum Dr. phil. Der Titel seiner Promotionsschrift lautete „Marxistische Ideologie und allgemeine Kunsttheorie“; Sander setzte sich hier insbesondere mit der Kunstkonzeption von Marx und Engels auseinander. Es war wohl insbesondere der Einfluß des Staatsrechtlers Carl Schmitt, mit dem er bis 1981 brieflich in Kontakt stand, der ihn in dieser Zeit mehr und mehr zu rechtskonservativen Auffassungen tendieren ließ. Von 1964–1974 arbeitete er für das Deutschland-Archiv. In dieser Zeit gestaltete er gelegentlich auch Rundfunkfeuilletons für öffentlich-rechtliche Sender. Sanders „Geschichte der Schönen Literatur in der DDR“ (1972) löste eine heftige Kampagne aus, in deren Folge der Verlag das Buch aus dem Vertrieb zog. Sander verlor nun zunehmend an publizistischem Spielraum. Alternativen fand er unter anderem bei Caspar von Schrenck-Notzings Zeitschrift Criticón.

1969 promovierte Sander bei Hans-Joachim Schoeps in Erlangen zum Dr. phil. Der Titel seiner Promotionsschrift lautete „Marxistische Ideologie und allgemeine Kunsttheorie“; Sander setzte sich hier insbesondere mit der Kunstkonzeption von Marx und Engels auseinander. Es war wohl insbesondere der Einfluß des Staatsrechtlers Carl Schmitt, mit dem er bis 1981 brieflich in Kontakt stand, der ihn in dieser Zeit mehr und mehr zu rechtskonservativen Auffassungen tendieren ließ. Von 1964–1974 arbeitete er für das Deutschland-Archiv. In dieser Zeit gestaltete er gelegentlich auch Rundfunkfeuilletons für öffentlich-rechtliche Sender. Sanders „Geschichte der Schönen Literatur in der DDR“ (1972) löste eine heftige Kampagne aus, in deren Folge der Verlag das Buch aus dem Vertrieb zog. Sander verlor nun zunehmend an publizistischem Spielraum. Alternativen fand er unter anderem bei Caspar von Schrenck-Notzings Zeitschrift Criticón.  Sander hat nie einen Hehl daraus gemacht, daß er die Bundesrepublik für nicht reformierbar hielt. Beide deutsche Staaten seien unter Kuratel der Besatzer entstanden, was unter anderem für eine Negativauslese im Hinblick auf die Eliten gesorgt habe. Dennoch sei nichts verloren: Die Deutschen bräuchten „sich nur innerlich aufzuraffen“, so Sander im „Nationalen Imperativ“, „um sich der brüchigen alten Zustände der Innen- und Außenpolitik zu entledigen, wieder auf die überlieferten, immer noch wirkenden Tugenden zu setzen und neue Formen und Ziele zu wagen, die in Richtung auf einen neuen Machtstaat, eine neue Großmacht drängen, die den Nachbarn durchaus zuzumuten wäre, weil durch nichts sonst das schutzbedürftige Europa noch gerettet werden kann.“ Diese Sätze können, in einer Zeit, in der Europa durch die Auswirkungen der „Flüchtlingskrise“ schutzbedürftiger denn je ist, durchaus als Vermächtnis Sanders nicht nur an die Deutschen gelesen werden.

Sander hat nie einen Hehl daraus gemacht, daß er die Bundesrepublik für nicht reformierbar hielt. Beide deutsche Staaten seien unter Kuratel der Besatzer entstanden, was unter anderem für eine Negativauslese im Hinblick auf die Eliten gesorgt habe. Dennoch sei nichts verloren: Die Deutschen bräuchten „sich nur innerlich aufzuraffen“, so Sander im „Nationalen Imperativ“, „um sich der brüchigen alten Zustände der Innen- und Außenpolitik zu entledigen, wieder auf die überlieferten, immer noch wirkenden Tugenden zu setzen und neue Formen und Ziele zu wagen, die in Richtung auf einen neuen Machtstaat, eine neue Großmacht drängen, die den Nachbarn durchaus zuzumuten wäre, weil durch nichts sonst das schutzbedürftige Europa noch gerettet werden kann.“ Diese Sätze können, in einer Zeit, in der Europa durch die Auswirkungen der „Flüchtlingskrise“ schutzbedürftiger denn je ist, durchaus als Vermächtnis Sanders nicht nur an die Deutschen gelesen werden.

According to Swiss-German historian Armin Mohler, who introduced this formula in a prolific albeit debatable study “Conservative Revolution in Germany: 1918–1932” [80] to describe an intellectual milieu hostile to the “ideas of 1789,” CR, as a cultural and political current, has taken shape in the interwar Germany, but its conceptual relevance transcends these temporal and geographic boundaries. Although later metaphysical discussions of Nietzscheanism

According to Swiss-German historian Armin Mohler, who introduced this formula in a prolific albeit debatable study “Conservative Revolution in Germany: 1918–1932” [80] to describe an intellectual milieu hostile to the “ideas of 1789,” CR, as a cultural and political current, has taken shape in the interwar Germany, but its conceptual relevance transcends these temporal and geographic boundaries. Although later metaphysical discussions of Nietzscheanism More precisely, this interwar German movement, which has always been escaping strict definitions, owes its reputation of the “ideocratic,” “metapolitical,” “neither right-wing, nor left-wing” Third Way precisely to embracing Nietzscheanism as a means of Weberian “re-enchantment of the world” [63]. Indeed, in social sciences and humanities, it was no sooner than Nietzsche put forward the event of the “death of god” that ideological and, basically, purely modern perplexities of the Left and Right have become a low priority compared to transhistorical (epochal) interplay of modernism and antimodernism, broader, the progressive and regressive vector. The latter were partially grasped by derivative intuitions of reactionary modernism [38], organological supermodern [63, 109; 40], archeofuturism [10], etc. in reference to Nietzsche-inspired phenomenon of CR.

More precisely, this interwar German movement, which has always been escaping strict definitions, owes its reputation of the “ideocratic,” “metapolitical,” “neither right-wing, nor left-wing” Third Way precisely to embracing Nietzscheanism as a means of Weberian “re-enchantment of the world” [63]. Indeed, in social sciences and humanities, it was no sooner than Nietzsche put forward the event of the “death of god” that ideological and, basically, purely modern perplexities of the Left and Right have become a low priority compared to transhistorical (epochal) interplay of modernism and antimodernism, broader, the progressive and regressive vector. The latter were partially grasped by derivative intuitions of reactionary modernism [38], organological supermodern [63, 109; 40], archeofuturism [10], etc. in reference to Nietzsche-inspired phenomenon of CR.

Indeed, so far, attempts to convert Nietzsche into politics have been mostly associated with the Nietzsche-Archiv’s destiny in the service of National Socialist ideology thanks to its ardent supporter Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, philosopher’s sister. However, the same destiny largely befell the work of conservative-revolutionary Nietzscheans, the brightest example being “The Third Empire”

Indeed, so far, attempts to convert Nietzsche into politics have been mostly associated with the Nietzsche-Archiv’s destiny in the service of National Socialist ideology thanks to its ardent supporter Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, philosopher’s sister. However, the same destiny largely befell the work of conservative-revolutionary Nietzscheans, the brightest example being “The Third Empire” On the other hand, according to Ernst Troeltsch, German philosopher of history, theologian and, along with Thomas Mann and Hugo von Hofmannsthal, one of the first promoters of the term “CR” [107, 454], only after the First World War, through “war experience,” Nietzsche’s thought was purified of its “sickly and exaggerated elements and thus had set ‘new aims’” [106, 75, quoted after 64, 48] for the German people. Jürgen Habermas confirms that Nietzsche reached the peak of popularity in Germany’s interwar period, when “the ideas of 1914” were confronted with “the ideas of 1789,” noting that “thinkers as various as Oswald Spengler, Carl Schmitt, Gottfried Benn, Ernst Jünger, Martin Heidegger, and even Arnold Gehlen show affinity with this background” [18, 209].