mardi, 09 mars 2010

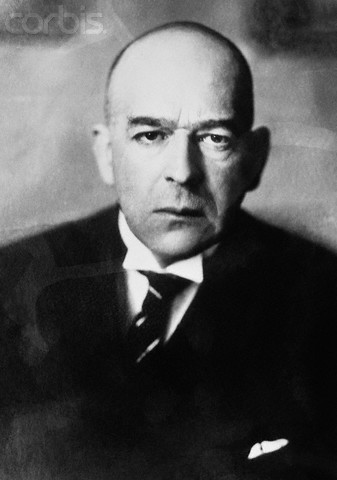

Sigrid Hunke et le sens de la mort

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1986

Sigrid Hunke et le sens de la mort

Sigrid Hunke est très connue Outre-Rhin. Le public francophone, lui, ne connaît que son livre sur l'Islam et les rapports intellectuels euro-arabes au Moyen Age (Le Soleil d'Allah brille sur l'Occident, Albin Michel, 1984, 2ème éd.) et sa remarquable fresque philosophico-religieuse "L'autre religion de l'Europe" (Le Labyrinthe, 1985). En 1986, Sigrid Hunke a publié un petit ouvrage fascinant sur le thème de la mort, tel qu'il est entrevu par huit grands systèmes religieux dans le monde, le christianisme, le judaïsme, l'Islam, le classicisme hellénique, la mythologie de l'Egypte antique, le bouddhisme, l'Edda germano-scandinave, les grandes idéologies modernes.

Pour le christianisme, écrit Sigrid Hunke, le Dieu tout-puissant, depuis sa sphère marmoréenne d'éternité, depuis son au-delà inaccessible, impose la mort à ses créatures en guise de punition pour leur désobéissance et pour leur prétention à devenir égales à lui. Le Christ, fils de ce Dieu omnipotent fait chair et "descendu" parmi les hommes, obéit à son Père, meurt crucifié, descend dans le royaume des morts et revient à la vie. Pour les premiers croyants, le règne paradisiaque, annoncé par ce Messie et par la tradition hébraïque, devait commencer dès la réapparition du Christ. Il n'en fut rien et ce fut le tour de force opéré par Paul de Tarse: cet apôtre tardif annonce que la mort est une parenthèse, qu'il faut attendre un "jugement dernier", où le Christ sépararera les pies des impies et jugera bons et méchants à la place de son "Père". Ce n'est qu'alors que commencera le règne définitif de Dieu, où injustice, misères, maladies auront à jamais disparues.

Pour le christianisme, écrit Sigrid Hunke, le Dieu tout-puissant, depuis sa sphère marmoréenne d'éternité, depuis son au-delà inaccessible, impose la mort à ses créatures en guise de punition pour leur désobéissance et pour leur prétention à devenir égales à lui. Le Christ, fils de ce Dieu omnipotent fait chair et "descendu" parmi les hommes, obéit à son Père, meurt crucifié, descend dans le royaume des morts et revient à la vie. Pour les premiers croyants, le règne paradisiaque, annoncé par ce Messie et par la tradition hébraïque, devait commencer dès la réapparition du Christ. Il n'en fut rien et ce fut le tour de force opéré par Paul de Tarse: cet apôtre tardif annonce que la mort est une parenthèse, qu'il faut attendre un "jugement dernier", où le Christ sépararera les pies des impies et jugera bons et méchants à la place de son "Père". Ce n'est qu'alors que commencera le règne définitif de Dieu, où injustice, misères, maladies auront à jamais disparues.

Quant au Dieu juif de l'Ancien Testament, il est, écrit Sigrid Hunke, un dieu des vivants et non des morts, lesquels sont à jamais séparés de lui. Ce Dieu n'entretient aucune relation avec le phénomène de la mort, avec les morts, avec le règne de la mort. Sa toute-puissance s'arrête là. La mort, dans le monde hébraïque, est fin absolue, négation, non-être définitif. Iavhé n'a aucun pouvoir sur Shéol, l'univers des défunts dans l'imaginaire hébraïque. Le corps du défunt rejoint la terre, la Terre-mère, que vénéraient les tribus sémitiques du Proche-Orient. Le Iahvisme, inauguré par Moïse, rompt les ponts avec cette religiosité tellurique des Sémites, entraînant un effondrement et une disparition des cultes voués aux défunts. Plus tard, après l'exil babylonien, les prophètes Ezra, Daniel et Enoch, renforcent cette radicale altérité entre l'au-delà iavhique et l'en-deça terrestre, par une instrumentalisation des dualismes issus de Perse. Dès lors, la césure entre l'esprit et la chair, entre Iavhé et l'homo peccator (l'homme pécheur), entre la Vie et la Mort, se fait encore plus absolue, plus brutale, plus définitive. Mais cette césure terrible, angoissante, se voit corrigée, par certaines influences iraniennes: désormais, à ce monde de larmes et de sang s'oppose l'espoir de voir un jour advenir un monde meilleur, rempli de cette "lumière" dont les Iraniens avaient le culte. Mais seul le peuple élu, obéissant à Iavhé en toutes circonstances, pourra bénéficier de cette grâce.

Le Dieu de l'Islam est l'ami des croyants, de ceux qui lui sont dévoués. Il leur accorde son amour et sa miséricorde. La Terre n'est pas réceptacle de péché: le péché découle du choix de chaque créature, libre de faire le bien ou le mal. L'Islam ne connaît pas de catastrophe dans la dimension historique, comme le iahvisme vétéro-testamentaire et le christianisme, mais bien plutôt une catastrophe globale, cosmique, après laquelle Allah recréera le monde, car telle est sa volonté et parce qu'il aime sa création et refuse qu'on la dévalorise.

Les dieux de la Grèce antique sont des immortels qui font face aux mortels. Pour Sigrid Hunke, contrairement à l'avis de beaucoup d'hellénisants, la Grèce affirme la radicale altérité entre la sphère du divin et la sphère de l'humain. Le destin mortel des hommes ne préoccupe pas les dieux, écrit-elle, et les âmes, libérées de leurs prisons corporelles, errent, pendant des siècles et des siècles, souillées par leur contact avec une chair mortelle pour éventuellement ensuite retourner dans l'empyrée d'où elles proviennent.

Les dieux de l'Egypte antique et des Germains sont eux-mêmes mortels. Pour les Egyptiens, les dieux ont tous une relation directe avec la mort. Chaque soir, le dieu solaire connaît la mort et, chaque matin, il revient, ressuscite rajeuni par ce voyage dans l'univers de la mort. Le défunt rejoint le dieu des morts Osiris et accède à un statut supérieur, dans le royaume de ce dieu. Dieux et hommes sont partenaires et responsables pour le maintien de l'ordre cosmique. Dans la mythologie germanique, les dieux sont des compagnons de combat des hommes. Lorsque ceux-ci meurent, les dieux les accueillent parmi eux, puisque, durant leurs vies, les hommes ont aidé les dieux à combattre les forces de dissolution.

Au XXème siècle, cette idée d'amitié entre dieux et hommes, est revenue spontanément, dit Sigrid Hunke, dans la pensée d'un Teilhard de Chardin, qui demandait à ses contemporains de lutter de toutes leurs forces aux côtés de la puissance du créateur pour repousser le mal". Idée que l'on retrouve aussi dans la mystique médiévale d'un Maître Eckhart qui voulait que les hommes deviennent des "Mitwirker Gottes", c'est-à-dire qu'ils collaborent efficacement à l'oeuvre créatrice de Dieu. Quant au Russe Nikolaï Berdiaev (1874-1948), il écrivait, en exil à Berlin dans les années 20: "Dieu attend la collaboration des hommes dans son travail de création; il attend leur collaboration dans le déroulement incessant de cette création". Cet appel à s'engager activement pour le divin implique une responsabilité de l'homme vis-à-vis du monde vivant, de la nature, de l'écologie terrestre, de la justice sociale, des enfants qui naissent et qui croissent,...

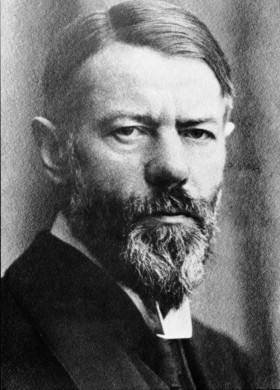

Pour Max Scheler, dont Sigrid Hunke admire la philosophie, l'homme doit se débarasser de son attitude infantile à l'égard de la divinité, oublier cette position de faiblesse quémandante et implorante que les religions bibliques lui ont inculquée et accéder à une religiosité adulte, c'est-à-dire participative. L'homme, à côté du divin, doit participer à la création, doit s'engager personnellement, s'identifier à l'oeuvre de Dieu.

La conclusion de la belle enquête de Sigrid Hunke est double: 1) il ne faut plus voir la mort sous l'angle sinistre de la négation; 2) le principe "confiance" est supérieur au principe "espérance". Avec les grands penseurs de ce que Sigrid Hunke a appelé "l'autre religion de l'Europe", Héraclite, Hölderlin, Hebbel, Rilke, etc., nous ne saurions regarder la mort comme la négation absolue, ni la craindre comme point final, comme point de non retour définitif mais, ainsi que l'avaient bien perçu Schelling et Tolstoï, comme une "reductio ad essentiam". La mort, dans cette perspective immémoriale, qui remonte aux premiers bâtisseurs de tumuli de notre continent, aux autochtones absolus dont nous descendons, est un retour à la plénitude de l'Etre; elle est un "retour à ce foyer qui est si proche des origines" (Heidegger). Et Sigrid Hunke de rapeller ces paroles de Bernhard Welte, prononcées au bord de la tombe de Heidegger: "... La mort met quelque chose en sûreté, elle dérobe quelque chose à nos regards. Son néant n'est pas néant. Elle cache et dissimule le but de tout un cheminement" (Der Tod birgt und verbirgt also etwas. Sein Nichts ist nicht Nichts. Er birgt und verbirgt das Ziel des ganzen Weges).

Ces paroles, si proches de la pensée heideggerienne, si ancrées dans la campagne Souabe et dans l'humus de la Forêt Noire, nous révèlent, indirectement, le principe "confiance". Une confiance dans le grand mouvement de l'Etre qui nous a jeté dans le monde et nous reprendra en son sein (Teilhard de Chardin). Le principe "confiance" est supérieur au principe "espérance" (Ernst Bloch), affirme Sigrid Hunke, car il ne laisse aucune place au souci spéculateur, au calcul utopique au doute délétère: il nous apprend la sérénité, la Gelassenheit.

En résumé, un livre d'une grande sagesse, servi par une connaissance encyclopédique des auteurs de cette "autre religion de l'Europe", pré-chrétienne, qui n'a cessé de corriger la folie anti-immanentiste judéo-chrétienne.

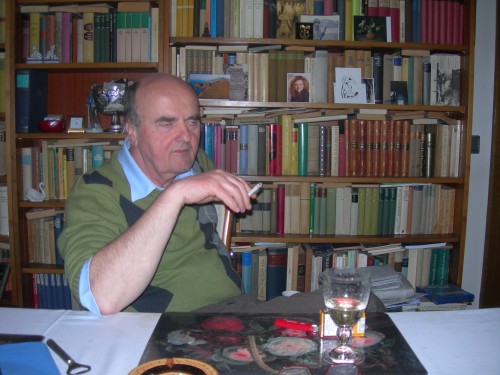

Bertrand EECKHOUT.

Sigrid Hunke, Tod was ist dein Sinn?, Neske-Verlag, Pfullingen, 1986, 164 S., DM 28.

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (2) | Tags : philosophie, mort |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 08 mars 2010

Das politische Volk

Das politische Volk

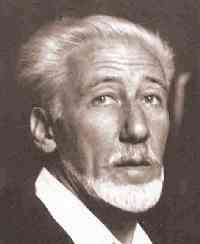

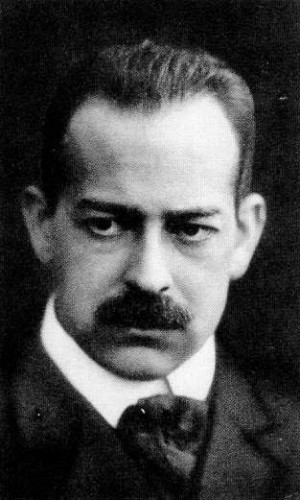

Hans Freyers Theorie der Volksgemeinschaft - eine Wirkungsgeschichte mit Brüchen.

(in: Ethnologie und Nationalsozialismus, Hg. Bernhard Streck, Gehren, Escher Verlag, 2000)

Geschichte der Soziologie oder Vergangenheitsbewältigung?

Um die Mitte der siebziger Jahre begann die Soziologie in Deutschland sich auf ihre jüngste Geschichte zu besinnen; es ging weniger um ihre Klassiker, die seit jeher zum Kanon der Fachausbildung gehörten, vielmehr um Werk, Wirkung und politisches Profil ihrer wissenschaftlichen "Väter" und "Großväter" als Repräsentanten der deutschen Soziologie der Zwischenkriegszeit 1918-1945. Auslöser für diese Recherchen waren einerseits neue Konzepte der Wissenschaftssoziologie: Die Struktur wissenschaftlicher Revolutionen und das Konzept des Paradigmenwandels (Kuhn 1976), soziale und kognitive Institutionalisierungsprozesse und Stadien der Wissenschaftsentwicklung (Mullins/Mullins 1973), wurden auf die eigene Disziplin angewandt und machten gerade die Zwischenkriegszeit mit ihren politischen Umbrüchen, sozialen Krisen und kulturellen Experimenten zum bevorzugten Analysegegenstand einer "Wissenschaftssoziologie der Soziologie". Andererseits waren diese wissenschaftlichen Bemühungen stets begleitet von einer stark emotionalisierten Aufarbeitung persönlicher Lebensgeschichten: als zornige Abrechnung der Nachkriegsgeneration mit ihren Vätern, als moralische Kritik an den geistigen Irrwegen, die zwangsmäßig zur Katastrophe des Nationalsozialismus führen mußten - oder auch als Rechtfertigung bzw. gegenseitige Schuldzuweisung der betroffenen Zeitzeugen. Diese Kontroversen haben eine systematische wissenschaftliche Analyse erschwert, aber gleichzeitig eine lebhafte und pointierte Diskussion ausgelöst und werden selbst wieder zu Forschungsgegenständen einer bewegten Wirkungsgeschichte der Soziologie, an der Konflikte und Zusammenwirken von wissenschaftlichen Ideen, persönlichen Karriereentscheidungen, plötzlichem Wechsel des politischen Rahmens und institutionellen Zwängen hervorragend studiert werden können. Die ideengeschichtliche Perspektive, die zweifellos ihre Berechtigung behält als Fortschreibung und Sicherung des disziplinären Wissenskanons, tritt hier zurück zugunsten einer wirkungsgeschichtlichen und wissenschaftssoziologischen Analyse und eines biographischen Aspekts. Damit erscheinen neben den Institutionen Wissenschaft und Universität mit ihren in langer Tradition gefestigten Regeln der Wissensproduktion, Sozialisation, Selektion, Paradigmenbindung etc., wissenschaftsexterne Einflußfaktoren auf das Werk: sowohl schicksalhafte Ereignisse, politische Umbrüche, Kriege, als auch subjektive Merkmale, wie Temperament und Begabung, familiäre Bindungen und Freundschaften, persönliches politisches Engagement und alle Zufälle des persönlichen Lebensweges; persönliche Verantwortung und Versäumnisse werden damit auch zum soziologischen Forschungsproblem.

Die Berücksichtigung außerwissenschaftlicher Faktoren, vor allem der politischen Ereignisse, hat in dieser deutschen Nachkriegsdiskussion zu einer nationalstaatlichen Isolierung der Soziologiegeschichte und zu einer zeitlichen Zentrierung auf das Schlüsselereignis der "Machtergreifung 1933" geführt. Beides ist sachlich unzulässig und führt zu verzerrten Ergebnissen. In der Zwischenkriegszeit bestand weiterhin ein dichtes Kommunikationsnetz der verschiedenen intellektuellen Milieus des deutschsprachigen Mitteleuropa - dazu gehörten auch Prag und Budapest als Kulturzentren der Habsburger Monarchie - das erst durch den 2. Weltkrieg zerstört wurde (Lepsius 1981a: 7-10). Auch eine zeitliche Eingrenzung auf die zwanziger Jahre oder auf die Zeit des Nationalsozialismus muß zu irreführenden Ergebnissen führen. Wenn auch die politische Zäsur 1933 in Deutschland einen deutlichen Bruch mit der Soziologie der zwanziger Jahre hervorrief und eine weitere Spaltung nach 1933 durch die Emigration verursachte, so sind doch in allen drei Fragmentierungen weiterhin auch Gemeinsamkeiten hinsichtlich wissenschaftstheoretischer Grundlagen, des wissenschaftlichen Selbstverständnisses und der Paradigmen festzustellen. Die äußerst schöpferische Kultur und Wissenschaft der Weimarer Republik zehrte von längerfristigen europäischen geistigen Strömungen, die durch Kulturkampf und Wissenschaftspolitik im wilhelminischen Deutschland größtenteils abgeblockt waren und danach mit gesteigerter Wucht zum Durchbruch kamen. Vor allem die Soziologie war davon betroffen - sie fand in Deutschland erst in den zwanziger Jahren Anerkennung als akademische Disziplin, und wurde im Gesamtzusammenhang dieses kulturellen Durchbruchs zur gesellschaftlichen Erneuerungsbewegung hochstilisiert. Die Ursprünge der Sozialwissenschaften und ihre großen Fortschritte im 19. Jahrhundert sind jedoch im langfristigen europäischen und transatlantischen Diskurs verankert, der in einer im Vergleich zu heute viel übersichtlicheren Wissenschaftsgemeinschaft mit wenigen maßgeblichen Zeitschriften nach 1918 in Deutschland noch einmal einen Höhepunkt erreichte. Die 1909 gegründete Deutsche Gesellschaft für Soziologie (DGS) hatte zahlreiche Mitglieder aus dem deutschsprachigen Mitteleuropa, die zum Teil auch führende Positionen einnahmen. Die durchgängigen europäischen kulturellen Traditionen blieben also ebenso relevant wie die nationalen politischen Ereignisse. Erst durch eine Mehrebenen-Betrachtung in diesem Sinne, die erstens vermeidet, das Jahr 1933 als einen alle gesellschaftlichen Bereiche revolutionierenden Bruch zu definieren, die zweitens sich nicht auf den deutschen nationalstaatlichen Raum beschränkt, der vor 1871 ja nicht in dieser Form existiert hatte, wird man das Zusammenspiel der einzelnen Ebenen zeigen können, in dem euphorische Übersteigerungen, Sinnverschiebungen und Bedeutungswandel sozialwissenschaftlicher Modelle und Theorien zustande kamen - ein Zusammenspiel, das von Synergieeffekten bis zur gegenseitigen Blockade reichen konnte.

Die meisten Arbeiten über diese Zeit wurden als "kritische" Analysen unternommen, jedoch nicht im Sinne dieser Mehrebenen-Analyse, die mit einer immanenten Interpretation auf der Grundlage einer zeitgenössischen Ortsbestimmung auch eine Einordnung in den Gesamtzusammenhang ex post, sowie ein Prüfen der logischen Folgerichtigkeit der Werke vereinen würde; "kritisch" verstanden sich die Forschungen vielmehr im Sinne einer "Vergangenheitsbewältigung", die das "falsche Bewußtsein" der damaligen Gelehrten als Wegbereiter des Nationalsozialismus aufdecken sollte und diese damit zu Ideologen erklärte. So wird in einer intellektuellen Biographie Hans Freyers von der wissenschaftlichen Leistung Freyers von vorneherein abgesehen (dabei jedoch konzediert, daß seine wissenschaftlichen Werke heute noch mit Profit gelesen werden könnten), da seine historische Bedeutung als radikal-konservativer Ideologe überwiege (Muller 1987: 3). In einer Darstellung der deutschen Soziologie 1933-45 wird Freyer zum Ideologen der nationalsozialistischen Bewegung erklärt, da er bereits 1930 den gesellschaftlichen Willen als Hiatus zwischen Vergangenheit und Zukunft bzw. Theorie und Praxis in sein soziologisches Konzept einbezogen hätte.(Rammstedt 1986: 44 f.) Oder er wird in einer renommierten historischen Darstellung der Kultur der Weimarer Republik lediglich als "völkischer Schriftsteller" erwähnt, seine wissenschaftliche Karriere wird dabei außer acht gelassen ( Gay 1970: 11). Dies sind durchaus folgerichtige Eingrenzungen des Forschungsinteresses, wenn Gesellschaft und Kultur der Weimarer Zeit ausschließlich vom "Endpunkt" des Nationalsozialismus her charakterisiert werden.

Die Frage, wie es 1933 zur politischen Katastrophe in Deutschland kommen konnte, die ja eine harte historische Tatsache ist, sollte nicht dazu führen, im nachhinein alle Entwicklungen auf diesen Kulminationspunkt der Katastrophe hin zu interpretieren. Am weitesten geht dabei wohl Georg Lukács, der eine immanente und zwingende Kausalkette herstellt von einem historischen Eklektizismus in der Nationalökonomie des 19. Jahrhunderts über einen Werterelativismus, gefördert durch die damalige Psychologie, bis zum Irrationalismus, bei dem Max Weber gerade durch seine Exclusion der Werte aus der Wissenschaft gelandet wäre - sowie zu Hans Freyer, der durch Übertragung der Existenz- und Lebensphilosophie auf die gesellschaftliche Ebene den positiven Weg zum Faschismus frei gemacht hätte (Lukács 1946). In derartigen Rezeptionen spiegelt sich der Kampf der Ideologien des 20. Jahrhunderts; sie tragen jedoch kaum zu einem historisch-wissenschaftlichen Erkenntnisfortschritt bei, denn was Resultat der Analyse sein sollte, ist darin von vorneherein vorgegeben; man betreibt "Vergangenheitsbewältigung, und die "wissenschaftliche" Arbeit wird dabei zur bloßen Reifikation. Auch in der historischen Analyse muß das Ergebnis zunächst offen sein, die Komplexität der Prozesse und die Falsifizierbarkeit der Ergebnisse und Theorien müssen erhalten bleiben.

Die wissenschaftliche Bearbeitung dieser Zeit wurde durch die Gründung einer Arbeitsgruppe "Ethnologie im Nationalsozialismus" nun im Fach Ethnologie aufgenommen, und die Arbeiten zur Soziologie der Zwischenkriegszeit können erste Vergleichsmöglichkeiten bieten. Das Buch von Otthein Rammstedt, Deutsche Soziologie 1933-1945 (1986) hat vermutlich deshalb in die ethnologische Diskussion Eingang gefunden, weil der Begriff der Volksgemeinschaft darin eine zentrale Rolle spielt. Dieses Buch, das eine Bibliographie der "Soziologischen Literatur im Dritten Reich" von mehr als 200 Seiten enthält, im Text aber nur wenige, bereits in anderen Arbeiten hinlänglich diskutierte Werke behandelt, kann hier als paradigmatisches Exempel einer wissenschaftlichen "Vergangenheitsbewältigung" im o.a. Sinn dienen.

Rammstedt kommt in seiner Abhandlung schnell auf das Hauptergebnis seiner Forschungen: Ab 1933 hätten die in Deutschland verbliebenen Soziologen eine paradigmatische Eigenständigkeit und Einheit nach innen wie nach außen vertreten, im Sinne einer "deutschen" Soziologie (in Anführungsstrichen) bzw. Deutschen Soziologie (groß geschrieben - ähnlich wie damals auch eine Deutsche Physik propagiert wurde). Da die für seine Abhandlung erstellte Bibliographie ein unerwartetes Übermaß an nationalsozialistischen Arbeiten ergeben hätte, fühlte Rammstedt sich berechtigt, mehr oder weniger die gesamte sozialwissenschaftliche Profession in Deutschland nach 1933 unter dieses einheitliche Paradigma der Deutschen Soziologie zu subsumieren, das er als einen totalitären Ansatz versteht, der jedoch weder von den zeitgenössischen Wissenschaften im Ausland, noch in späteren Rezeptionen, auch nicht in der bisherigen Fachgeschichtsschreibung wahrgenommen worden wäre (1986:20-22).

Zwei Kritikpunkte sind hier anzuführen:

Erstens müßte die Feststellung, daß die zeitgenössische internationale scientific community, die doch die deutsche Entwicklung äußerst kritisch verfolgte, den totalitären Ansatz der Deutschen Soziologie nicht wahrgenommen hätte (Rammstedt 1986: 22f.), und die sich dabei auf Durchsicht renommierter Zeitschriften und Verhandlungen internationaler wissenschaftlicher Gesellschaften nach 1933 bezieht, den Autor doch zu einer Überprüfung veranlassen, ob seine Subsumierung der Soziologie in Deutschland unter das totalitäre Paradigma Deutsche Soziologie überhaupt wissenschaftlich haltbar ist. Freyers theoretische Grundlegung der Soziologie (1930), auf der seine nachfolgenden Arbeiten zu den Aufgaben der Soziologie, zur politischen Erziehung, zu Herrschaft, Planung und Technik, sowie zum Volksbegriff theoretisch aufgebaut sind, ist als eine der wenigen Arbeiten der jüngeren deutschen Soziologengeneration nach Max Weber im Ausland rezipiert worden. Sie wurde als interessante Fortführung des Ansatzes Max Webers in Frankreich auch nach 1933 wahrgenommen (Aron 1935: 4, 175), und der amerikanische Soziologe Talcott Parsons übernahm 1937 in seinem frühen Hauptwerk The Structure of Social Action (New York 1968: 473) nicht nur Freyers geschichtsphilosophische Fundierung der Soziologie im Idealismus, sondern stützte sich auch im wesentlichen auf Freyers Klassifikation der Wissenschaften in Natur-, Logos-, und Wirklichkeitswissenschaften (762, 774), um nur einige Beispiele des internationalen Diskurses zu nennen. Einige der Schüler Freyers haben sowohl in Deutschland als auch in der Emigration dessen theoretische Grundlegung ausgebaut1.

Zweitens kommt mit der Subsumierung aller soziologischer Arbeiten in Deutschland nach 1933 unter "Deutsche Soziologie" eine ideologische Kategorisierung der Soziologie sozusagen "durch die Hintertür" wieder ins Spiel, die damals nur von wenigen nationalsozialistischen Karrieristen vertreten wurde: Wenn man alle in Deutschland verbliebenen Soziologen unter dem Paradigma "Deutsche Soziologie" zusammenfassen kann, müßte daraus dann nicht auch eine Zusammenfassung der Emigranten folgen - etwa unter dem Paradigma "Jüdische Soziologie", oder "liberalistische Soziologie"?

Rammstedt hat auf jeden Fall einen heftigen Protest der älteren Soziologengeneration als Zeitzeugen herausgefordert. Unter ihnen war es vor allem René König, der selbst noch nach 1933 in Deutschland studiert und und publiziert hat, bis er 1938 nach Zürich ging - der als einer der führenden deutschen Soziologen nach 1945 zeit seines Lebens gegen alle restaurativen Tendenzen und gegen die Fortsetzung nationalsozialistischer Karrieren gekämpft hat - der die theoretische Denkfigur der Deutschen Soziologie bei Rammstedt lediglich durch einen primitiven Empirismus abgestützt fand (König 1987: 393 ff.): Statt seine These theoretisch zu differenzieren, könne er sie nur abstützen durch "eine ungemein dilettantisch und primitiv aufgestellte Bibliographie, [die] das bisher erreichte Maximum an versuchter Irreführung eines harmlosen Publikums darstellt, das über keinen substantiellen Blick nach rückwärts verfügt [...]" (395). König mahnt dabei nicht nur das Fehlen seiner und vieler anderer Publikationen in der Bibliographie an, sowie den fehlenden Bezug auf seine eigene bereits 1937 geschriebene theoretische Kritik der historisch- existenzialistischen Soziologie (1975), sondern bezichtigt Rammstedt darüber hinaus, er hätte sich auf genau die abwegige Linie weniger Soziologen (vor allem Hans Freyers) um 1933 verleiten lassen, die aus der Fiktion, die gesellschaftliche Wirklichkeit hätte sich mit dem politischen Umbruch 1933 sprunghaft geändert, folgerten, daß die Erkenntnishaltung der Soziologie als Wissenschaft sich ebenfalls grundlegend ändern müsse (394) - hin zur nun alleine hoffähigen Deutschen Soziologie. König verabsolutiert hier allerdings ebenfalls den Umbruch 1933, denn die soziologischen Theorien der sogenannten Deutschen Soziologen Rammstedts wurden lange vor 1933, in den Aufbruchsjahren der Weimarer Republik konzipiert. Auch tendiert König in seiner o.a. theoretischen Kritik stellenweise zu ähnlichen Vereinfachungen, indem er die historisch-existenzialistische Soziologie besonders anfällig für Gewalt (1975: 13) und die Anfälligkeit dieser Denkformen und Denker für den Nationalsozialismus (1975: 267) herausstellt und sich dabei im wesentlichen auf Freyer und Heidegger beruft. Da zu den berühmtesten Vertretern einer historisch-existenzialistischen Soziologie auch Emigranten der "Frankfurter Schule" zu rechnen sind, führt es nicht weiter, theoretische Denkfiguren, wie die historisch-existenzialistische Theorie, eine politikwissenschaftliche Liberalismuskritik, oder auch die Gleichsetzung von Theorie und Praxis, mit Faschismus oder Nationalsozialismus in eine Linie zu bringen. Um derartige Theorien mit der Realpolitik zu verbinden, sind immer institutionelle Schaltstellen nötig, und diese sind im einzelnen nachzuweisen.

Im Falle Hans Freyers wird versucht, diese Schaltstelle zu belegen durch seine Wahl zum Präsidenten der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie (DGS) im Dezember 1933 (u.a. Klingemann 1981, Käsler 1984). Hans Freyer nahm nach vorheriger Absage die Wahl zum Präsidenten der DGS im Dezember 1933 nur deshalb an, um die Gegengründung eines neuen nationalen Soziologenverbandes durch eine radikale Gruppe NS-orientierter Soziologen, die sich tatsächlich "Deutsche Soziologen" bezeichneten, zu verhindern2. Das ist gelungen, und nach 1934 gab es keinen nennenswerten Auftritt dieser radikalen Deutschen Soziologen mehr, bzw. ist sie offensichtlich nie zu einer nationalen Organisation geworden.

Freyer hätte Ende 1933 tatsächlich alle institutionellen Möglichkeiten in der Hand gehabt, zum "Führer" der Soziologen im neuen nationalsozialistischen Deutschland zu werden: Er war Präsident der traditionellen Fachorganisation DGS, er wäre als Kompromißkandidat auch von der neuen radikalen Gruppe akzeptiert worden, und er war bestens eingeführt sowohl in der internationalen Kant-Gesellschaft als auch in der Deutschen Philosophischen Gesellschaft; er hätte zudem als Herausgeber der neuen soziologischen Zeitschrift Der Volksspiegel (ab 1933) die Schaltstelle für Publikationen einer nationalsozialistischen Soziologie kontrollieren können. Aber er nützt keine dieser Gelegenheiten aus, unterläßt weitere Aktivitäten als Präsident der DGS und gibt die Herausgeberschaft des Volksspiegel 1934 wieder auf. Aus dem Nicht-Ausnützen insitutioneller Vorteile und aus seiner wiederholten Ablehnung einer Parteimitgliedschaft läßt sich schließen, daß sich Freyer von einer nationalsozialistischen Vereinnahmung fernhalten wollte, was er stets sehr höflich und vorsichtig, niemals mit theatralischer Pose, durchzuhalten wußte. Auch spricht Freyers Rückzug gegen Rammstedts These, Freyer hätte, wie die anderen Deutschen Soziologen, die hypertrophe Absicht gehabt, die Soziologie als eigenständige Kraft im Prozeß der Volkwerdung neben der Politik zu institutionalisieren (Rammstedt 1986: 128 f.); dazu wären doch die ihm zur Verfügung stehenden Positionen hervorragend geeigent gewesen. Sein Wirken an der Universität war nach übereinstimmenden Aussagen ehemaliger Schüler gekennzeichnet vom Bemühen, nach außen möglichst kein Aufsehen zu erregen, um seinen Schülern und Kollegen in seinem Istitut einen Schutzraum zur wissenschaftlicher Arbeit zu erhalten. In der Atmosphäre des zunehmenden allgemeinen Mißtrauens konnte das allerdings auch irritieren - man wußte nicht, woran man war3. Die Konzessionen Freyers werden genauestens berichtet ( z.B. Muller 1987), die Gegenbeispiele jedoch übersehen: Freyer hat nach 1933 sowohl die Marx-Studien seines Schülers Heinz Maus (nach 1945 einer der prominenten Vertreter einer marxistischen Soziologie in Marburg) gedeckt und ihn aus dem Gefängnis geholt4, wie auch den Leipziger Philosophen Hugo Fischer bis zu seiner Flucht nach Norwegen geschützt, der (wie H. Maus) mit der nationalbolschewistischen Bewegung verbunden war. Für die Berliner "Mittwochsgesellschaft" war Freyers Deutsches Wissenschaftliches Institut in Budapest bis 1944 ein ausländisches Vortrags- und Kontakt-Refugium, und zahlreiche ungarische Kollegen verdanken Freyer ihre Rettung in letzter Minute vor den sowjetischen Besatzern. Freyer wird von Carl Goerdeler als Mittelsmann seiner Widerstandsgruppe in den Verhören nach dem 20. Juli 1944 genannt, und diese Verhöre sind längst publiziert (Archiv Peters 1970). Nach 1945 hat Freyer in Leipzig den in Bonn abgelehnten marxistischen Historiker Walter Markov habilitiert, der später, mit Jürgen Kuczynski in Berlin als Gegenfigur, zur Historikerprominenz der DDR gehörte.

1933 - Zugriff der Politik - Abwehrmechanismen der Wissenschaft

Aus soziologischer Sicht ist die Wissenschaft als gesellschaftlicher Prozeß zu denken, d.h. es ist herauszustellen, "welche Funktionen und Wirkungen die Wissenschaft im gesellschaftlichen Prozeß hat bzw. unter welchen gesellschaftlichen Bedingungen ihr diese Funktionen zugeschrieben werden können" (Bühl 1974: 19). Das soll auf keinen Fall heißen, daß Wissenschaft nur ein "Abbild der gesellschaftlichen Verhältnisse" wäre (zu diesem ist sie gerade in geschichtlichen Rückblicken oft degradiert worden), sondern es wird das Modell eines relativ selbständigen Teilsystems zugrundegelegt, in dem die gesellschaftliche Definition und Funktion von Wissenschaft und die immanenten logischen Konstrukte und wissenschaftstheoretischen Definitionen relativ unabhängig variieren. Die Wissenschaftssoziologie geht heute von einem sehr komplexen Zusammenwirken auf unterschiedlichen Ebenen des inneren und des äußeren Systems von Wissenschaft aus - ein Modell, das der Wissenschaft als eine der großen Institutionen der modernen Industriegesellschaft seit Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts am ehesten entspricht. Die modernen Diktaturen im 20. Jahrhundert konnten weder auf die Wissenschaft verzichten, noch diese Institution vollkommen unter ihre Kontrolle bringen; die Förderung der Wissenschaften gehörte zu ihrem politischen Programm (wenn auch nach ihren politischen oder weltanschaulichen Vorstellungen), da der wissenschaftliche Fortschritt politische Macht und internationalen Einfluß verlieh. Ab welchem Punkt das komplexe Zusammenspiel von Wissenschaft und Politik mit seinen Prozessen der Kooperation, Konkurrenz, Selektion von vordringlichen Aufgaben, von Personal, Kontrolle der Veröffentlichungen usw., das in jeder modernen Gesellschaft in unterschiedlichen Varianten stattfindet, pervertiert wird und zu einseitiger Machtausübung führt, muß in jedem Einzelfall untersucht und begründet werden.

Bereits das "Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums" 1933, danach u. a. die bürokratische Macht der NS-Dozenten- und Studentenbünde, die vornehmlich jüngere, karrierebesessene, aber wissenschaftlich mittelmäßige Köpfe anzog, waren Perversionen des komplexen Wissenschaftssystems, deren Folgen nicht nur im Verlust durch Emigration oder in der Rekrutierung von nationalsozialistischen Parteigängern bestanden, sondern die sich bis in die wissenschaftlichen Texte auswirkten, auch in solche, die als nicht politisch relevant galten. Entstellungen der Wissenschaft in diesem Sinne sind in den Verklausulierungen der inneren Emigration ebenso zu finden, wie in der zweideutigen Alltagskommunikation von Kollegen, die sich seit langer Zeit zu kennen glaubten. Es war ein schleichender Erosionsprozeß der Wissenschaft, dessen Folgen weit in die Nachkriegszeit wirkten. Trotzdem war auch in dieser "dürftigen Zeit" die Wissenschaft nicht am Ende.

Im Prozeß der zunehmenden Unterhöhlung der wissenschaftlichen Institutionen durch die Politik wird die Erhaltung des noch verbleibenden "Restsystems" um jeden Preis zum Überlebensprinzip. Dabei kommt es zu unvermeidlichen "Abwehrmechanismen" gegen die politischen Übergriffe, die in allen modernen totalitären Regimes in ähnlicher Weise auftreten. Sie haben die Funktion, das Wissenschaftssystem, wenn auch unzulänglich oder entstellt, aufrechtzuerhalten und dem direkten politischen Zugriff insgeheim auszuweichen - die Bildung von kleinen Verschwörergemeinschaften der engsten Mitarbeiter, die bewußten Plagiate oder die Camouflage brisanter Themen in Klassiker-Analysen gehören ebenso zu diesen wissenschaftlichen Abwehrmechanismen, wie ein übertriebenes professionelles Verhalten und Vokabular, mit dem politische Gegner ihre parteiideologischen Kämpfe verbrämten, oder auch die beflissene Einhaltung bürokratischer Regeln, um wenigstens ein Mindestmaß an wissenschaftlicher Arbeit voranzubringen. Diese Abwehrmechanismen verursachen Schäden und sind zu bedauern wie Krankheitssymptome, ihr Auftreten ist jedoch ebenso sicher zu erwarten wie diese, wenn eine derartige politische Situation einmal eingetreten ist.

Bei der institutionellen Gleichschaltung der Universitäten waren den betroffenen Wissenschaftlern kaum Handlungsspielräume gegeben; die Maßnahmen des Gesetzes zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums, die Beschneidung der Rechte der Fakultäten, die Einführung des "Führerprinzips", d.h. die Aufhebung der Wahlen des Rektors bzw. der Dekane usw. waren eindeutige Vorschriften und konnten nur auf informellen Wegen gemildert werden. Das wurde in Leipzig häufig praktiziert, sei es durch nachlässige Bearbeitung des Ariernachweises, durch Hervorhebung der Teilnahme am 1. Weltkrieg, politischer Verdienste, oder des sozialen Engagements eines gefährdeten Kollegen, oder z. B. auch durch informelle Beeinflussung bei der Ernennung der Dekane. Hans Freyer hat in dieser Zeit mit großem Geschick die Rolle des savant prudent eingenommen, die ja taktisches Denken, Schläue und List nicht ausschließt5. Auf der institutionellen Ebene kann man Freyer also kaum zur Gallionsfigur des Nationalsozialismus erklären. Da auch die persönliche Biographie keine Anhaltspunkte ergab, bleibt also noch sein wissenschaftliches Werk zu untersuchen. Es war hauptsächlich seine Pallas Athene. Ethik des politischen Volkes (1935), sowie seine Schriften Revolution von rechts (1931), Der Staat (1925) und seine Aufsätze zum Volksbegriff zwischen 1928 und 1934, die in der Nachkriegsrezeption als Nachweis herangezogen wurden, daß er die nationalsozialistische Ideologie vorbereitet bzw. unterstützt hätte.

Volk als Rasse oder "Volk als Tat"?

Der Volksbegriff als Krisenbewältigung der Moderne.

Es sollte nicht unbeachtet bleiben, daß Freyers Reflexionen über den Volksbegriff auf einem langfristigen wissenschaftlichen Diskurs aufbauen. Die Weiterführung von Hegels Phänomenologie des Geistes und seiner Rechtsphilosophie, die Verarbeitung von Fichtes und Lorenz von Steins Staatslehre, die Einbeziehung der Werke von Dilthey und Simmel, Max Webers politischer Soziologie und nicht zuletzt der damals höchst aktuellen Wissenssoziologie, müssen als Gegenstand einer Theorieanalyse (Üner 1992) hier ausgeklammert bleiben. Jedoch kann eine dokumentarische Skizze der wissenschaftlichen Diskurse um den Volksbegriff seit dem 19. Jahrhundert und deren Synergieeffekte mit sozialen und politischen Umwälzungen zur genaueren Bestimmung dienen, wie die Schnittpunkte von langfristigen wissenschaftlichen Diskursen mit politischen Ereignissen die Deutungen des Volksbegriffes beeinflußt haben.

Nach dem 1. Weltkrieg, als Folge des Zusammenbruchs der großen Reiche - des russischen, des österreichisch-ungarischen sowie des osmanischen - stand in ganz Europa die Diskussion um die Volksgemeinschaft im Mittelpunkt. Einerseits wurde die eigene Geschichte und Kultur, Sprache und Traditionen des jeweiligen Volksgemeinschaft aus der Zeit vor der Einbindung in die Großreiche als die eigentliche historische Identität und gemeinschaftsbindende Kraft wieder in Erinnerung gerufen; andererseits wurden aber durch Friedensverträge neue staatliche Einheiten gebildet, die wiederum unterschiedliche ethnische Minderheiten umfaßten; z.B. wurden ehemals ungarische Gebiete der neuen Tschechoslowakei oder Rumänien eingegliedert, oder deutsche Minderheiten kamen erneut zu Frankreich. Das Problem der Nationwerdung (nation building) beschäftigte das zerstückelte Europa und hat der facettenreichen Diskussion des Volksbegriffes in den zwanziger Jahren, die sich zwischen den Extremen biologisch-rassistischer Positionen einerseits und einer expressionistisch-humanistischen, oder auch sozialistischen Weltgemeinschaft andererseits bewegte, einen äußerst aktuellen politischen Gehalt gegeben. Es ist dabei zu betonen, daß diese polarisierte öffentliche Diskussion im Rahmen neuer, die jeweiligen Monarchien ablösender republikanischer Staatenbildungen stattfand, und somit die Vision einer neuen "res publica" der modernen Massengesellschaft, für die alle bisherigen historischen Beispiele als unzulänglich angesehen wurden, auch hinter diesen Kontroversen nach dem 1. Weltkrieg stand. Diese republikanische Idee wurde im kontinentalen Europa jedoch im Laufe der zwanziger Jahre zunehmend durch moderne Diktaturen6 propagiert, die sich in unterschiedlichen Varianten der Idee eines plebiszitären Führerstaates verpflichtet sahen und insgesamt als Retter der Volksherrschaft, oder der "wahren Demokratie" auftraten. Das Konzept einer biologischen Rasse oder einer ausschließlich durch Geburt bestimmten Volksgemeinschaft blieb dabei ein Außenseiterthema; wenn auch die zeitgenössische expressionistische Literatur euphorisch von "Volk" "Blut" und "Rasse" sprach, oder Hans Freyer in seiner kulturphilosophischen Staatstheorie die Heilighaltung der Rasse (1925: 153) als wichtigste Aufgabe der Macht verkündete, so waren das symbolische Exaltationen für eine durch gemeinsame Geschichte, Sprache und Traditionen übermittelte Kultur.

Man kann diese Diskussion als einen Durchbruch in das öffentliche Bewußtsein und als krisenbedingte Steigerung und Popularisierung ausgedehnter wissenschaftlicher Diskussionen aus dem 19. Jahrhundert über "Volk als Rasse" und dessen Gegenbegriff "Volk als Tat" bezeichnen7. Das Zusammentreffen von wissenschaftlichen Erkenntnissen, die Übertragung eines wissenschaftlichen Modells einer Disziplin in eine andere, und die Popularisierung der wissenschaftlichen Erkenntnisse durch Medien, soziale Bewegungen und Politik können zu unerwarteten Synthesen führen: z. B. wurde das darwinistische Prinzip der Evolution der Natur durch Selektion übertragen auf historische Prozesse als Wettbewerbsprinzip: Fortschritt durch Veredelung und Auslese der Völker; damit erschien eine Reduzierung vom kulturellen Fortschritt der Menschheit auf den der Nation gerechtfertigt. Oder es kam zu einer politische Synthese eines biologischen Rassebegriffes mit der kulturellen Herkunft, die vor allem durch den immensen wissenschaftlichen Ausbau der Philologie im 19. Jahrhundert: Slawistik, Germanistik, Romanistik, etc. ausgelöst wurde. Im Zuge der politischen Nationalbewegungen ging aus dieser wissenschaftlichen Differenzierung ein neuer Urmythos hervor: Dadurch, daß Ergebnisse vergleichender Sprachforschung,nämlich die Verflechtungen verwandter Sprachen, auf ethnische Gebilde übertragen wurden, ergaben sich aus Sprachfamilien Völkerfamilien, deren Stammesursprung nun wissenschaftlich erforscht werden sollte. Diese Suche nach dem "Urvolk" schlug sich politisch in den zahlreichen "Pan-Bewegungen" nieder - Panslawismus, Pangermanismus etc., und die damit verbundene wissenschaftliche Erforschung von Wanderungsbewegungen führte wieder zurück zum Problem der "Rasse". Deshalb konnten bei der Gründung der "Société Ethnologique" in Paris 1839 Programm und Ziele dieser Vereinigung als Elemente der Rassenforschung bezeichnet werden (Brunner u.a.1972 f., Bd. 5: 157-159), während die Ethnologie Ende 1920 als reine Kulturwissenschaft verstanden wird8.

Wenn auch der biologische Rassebegriff in den Sozialwissenschaften der Weimarer Zeit nur noch periphere Bedeutung hatte (die "Geschichte als Rassenkampf" war wissenschaftlich nicht mehr zu vertreten), so bestimmte er als Amalgam von Rasse-Urvolk-Urkultur nach wie vor die öffentliche Diskussion in Bewegungen z.B. des Zionismus, oder des Alldeutschtums, wie auch in der expressionistischen Literatur, die allesamt damit auch eine wissenschaftliche Grundlage für ihre Ziele beanspruchen konnten. Die auf den biologischen Rassebegriff konzentrierte Spezialdisziplin der Eugenik, in der die amerikanischen Humanwissenschaften die Vorreiter waren, wurde von Erneuerungsbewegungen - sowohl rechter wie linker politischer Couleurs - ebenfalls popularisiert und "voluntarisiert": die Planbarkeit des Erbes versprach Befreiung aus dem Zustand des Ausgeliefertseins an die Natur und verhieß bewußte Gestaltung - des germanischen oder auch des sozialistischen freien Menschen. Es ist wissenschaftgeschichtlich zu wenig aufgearbeitet, wie sehr die junge Disziplin der Bevölkerungswissenschaft der zwanziger Jahre in Verbindung mit der Eugenik gerade von linken Bewegungen gefördert und in die politische Arbeit einbezogen wurde. Der wissenschaftliche Referent im sozialdemokratischen sächsischen Kultusministerium, Karl Valentin Müller, in den Fächern Geschichte, Nationalökonomie und Statistik an der Universität Leipzig promoviert, verfaßte 1927 im Auftrag der Gewerkschaftsbewegung die Schrift Arbeiterbewegung und Bevölkerungsfrage, mit dem Untertitel: Eine gemeinverständliche Darstellung der wichtigsten Fragen der quantitativen und qualitativen Bevölkerungspolitik im Rahmen gewerkschaftlicher Theorie und Praxis; die Kapitelüberschriften reichen von der Gesellschaftsbiologie über Arbeiterbewegung und Rassenhygiene bis zu Siedlung und Wanderung als Lohnbestimmungsgrund.

Der mit der Idee der Planbarkeit einer Gesellschaft verbundene Voluntarismus konnte ohne weiteres mit dem Konzept des "Volkes der Tat" verschmelzen, das aus den konstitutionellen Bewegungen Anfang des 19. Jahrhunderts stammt: Das Volk, das aus dem gegenwärtigen Zustand der Unmündigkeit heraustritt und sich eine gemeinschaftlich erarbeitete Constitution gibt, die nun die Kräfte der einzelnen zu einem geschichtlichen Ziel der Volksgemeinschaft vereinigt9. In euphorische Hoffnungen steigerte sich diese Volksdiskussion in der Literatur des politischen Expressionismus der Zeit: Das Individuum ist gefallen. Das Volk steht auf, der Mensch und das Volk, beide wollen eins sein - sie wollen Menschheit sein. Die Vernichtung des Eins, um das All zu sein, ist der Sinn der namenlosen Erschütterung, die Menschen und Völker der Gegenwart umgestaltet (Lothar Schreyer); Masse wird als "wirkendes Volk" (Ludwig Rubiner) oder als "verschüttet Volk" (Ernst Toller) beschworen, aus deren Trümmern sich das Volk als höhere freie Gemeinschaft erheben wird (Üner 1981: 135-141).

Derartige Begriffssynthesen führen dazu, daß es in der wissenschaftlichen Rezeption, den Expertisen und in der Anwendung ihrer Ergebnisse, immer schwieriger wird, die Begriffe und Resultate sauber zu trennen. Auch innerhalb der wissenschaftlichen Diskussion herrschen dann die Analogieschlüsse, die Übertragung der Modelle auf andere Disziplinen vor. Nun sollte das nicht von vorneherein als Defizit bewertet werden. Um ein "Darüber-hinaus" über den bisherigen Wissensstand der eigenen Wissenschaft zu erreichen, die Verhärtungen der eingefahrenen Theorien aufzubrechen, müssen die disziplinären Grenzen überschritten werden, um neue Inspirationen aus Entdeckungen anderer Gebiete zu gewinnen und sich neuen Aufgaben aus dem politisch-sozialen Umfeld zu stellen. Gerade in Zeiten des krisenhaften Wandels wird auch ein Wissenschaftsverständnis vorherrschen, das gekennzeichnet ist durch Gegenerschaft den Traditionen der etablierten Disziplin gegenüber - die "Wissenschaft als Bewegung" (Üner 1992: 16-19), die nicht mehr die "Reform" des Bestehenden, sondern eine "Revolution" im Sinn des "Umsturzes der Werte"10 anstrebt, die eine neue "Weltsicht" und den ethischen Appell in den Vordergrund stellt. Eine ins Detail gehende logisch-analytische Diskussion ist noch gar nicht möglich, weil dem alten Wissenschaftsverständnis noch kein neues entgegengesetzt werden kann - und auch nicht soll, denn man will ja aus der Verhärtung des bisherigen Systems herauskommen. Gerade deshalb wird eine große Ausdehnung der wissenschaftlichen Bestrebungen auf andere Disziplinen und auch auf religiöse, künstlerische und soziale Erneuerungsbewegungen möglich. Die "Wissenschaft als Bewegung" ist keinesfalls als zweitrangig einzustufen, sie bleibt neben der sogenannten "Expertenwissenschaft" eine konstitutive Komponente jeder Wissenschaft; denn hohe Spezialisierung bedeutet immer auch Erstarrung und Senilität, die wieder aufgebrochen werden muß.

In diesen kaum mehr entwirrbaren Verflechtungen von wissenschaftlicher Diskussion und Aufbruchsparolen der sozialen Bewegungen sind die ersten wichtigen Arbeiten Hans Freyers zur Geschichts- und Kulturphilosophie (1921, 1923), zum Staat als Kultursystem (1925) und zum Begriff des "politischen Volkes" entstanden. Freyer ging in seinen frühen Schriften während der Weimarer Republik, anknüpfend an Hegels Volksgeist, vom Volk als kulturelle Konkretion bzw. vom Staat als Einheit der Gesamtkultur aus (1966: 129 ff.) - wie übrigens auch sein Leipziger Kollege Theodor Litt, der ebenfalls Staat und Volk als "Wesensgemeinschaft" idealisiert, in der eine Ineinssetzung von Individuum und Gemeinschaft stattfände (Litt 1919: 171 ff.). Eine unpolitische Flucht in eine höhere Realität ist bei keinem von beiden intendiert, denn sie knüpfen doch sehr dezidiert an eine die deutsche Reichsgründung begleitende politische Diskussion um die Kulturnation an: Mensch und Volk einander zugeordnet, Volk ist durch Führung geschaffen, jedoch wird - nun im Denkstil der Weimarer Reformen - Führung mehr eine Leistung der geführten Schar, als eine Leistung des Führers; je weiter der Schaffensprozeß fortschreitet, desto mächtiger wird das Werk, um so ohnmächtiger sein Täter (Freyer 1925: 108 f.). Die in den zahllosen kulturellen Erneuerungsbewegungen des Expressionismus, der Jugendbewegung, der Arbeiterkultur etc. artikulierten Konflikte zwischen Mensch und Masse, Natur und Kultur, Kultur und Geschichte, Geist und Macht, vereint Freyer als Kulturphilosoph in seinen Werken bis 1925 mit gleichem expressionistischen Pathos (Üner 1981) zu einer eher integrationistischen dialektischen Theorie der Sinnzusammenhänge, der Objektivationen der Kulturwirklichkeit, während er ab 1925, nun als Ordinarius der Soziologie11, die soziale Wirklichkeit als Handlungszusammenhang und Entscheidungsprozeß in den Vordergrund stellt. Die Schriften vor und nach 1925 können durchaus als komplementäre Analysen der gesellschaftlich-kulturellen Welt betrachtet werden. Die Komplementarität bezieht sich dabei nicht auf die Untersuchungsgegenstände - es handelt sich nicht um die Analyse von Kulturphänomenen einerseits und die Untersuchung gesellschaftlich-politischer Erscheinungen andererseits, sondern um zwei komplementäre wissenschaftliche Betrachtungsweisen ein- und desselben Lebenszusammenhangs. Bemerkenswert ist - wirkungsgeschichtlich gesehen - wie zeitgleich der Wechsel Freyers vom Lehrstuhl für Philosophie in Kiel zum Ordinariat für Soziologie in Leipzig (den er ja nicht maßgeblich beeinflussen konnte) und damit der Wechsel seiner wissenschaftlichen Aufgaben mit einer verstärkten Kulturpolitik zusammenfällt, in der man durch Erwachsenenbildung, Volksbibliotheken, Volksmusikbewegung, Arbeiter- und politische Bildung das "Werden" des Volkes voranbringen wollte.

Hans Freyers Begriff des "politischen Volkes".

Zusammenfassend kann man Freyers "Volk" als politischen Begriff - im Kontext der aktuellen politischen Turbulenzen deutlich vom Volksbegriff in seiner Kulturphilosophie bis 1925 unterschieden - als dynamische und handlungsorientierte Kategorie bezeichnen, die der gegenwärtigen politischen Gemeinschaft im revolutionären Wandel entsprechen sollte: Das "politische Volk" ist nach Freyers historischer Einordnung eine Erscheinung der Moderne, erstmals möglich geworden im Zeitalter der Aufklärung und durch die darauf folgenden Säkularisierungsbewegungen in allen Wissensbereichen der sich konsolidierenden Industriegesellschaft im 19. Jahrhundert; der Begriff "politisches Volk" steht für eine neue, nicht mehr auf organisch gewachsenen kulturellen Traditionen oder auf unveränderbaren staatlichen Institutionen begründete politische Gemeinschaft, die erstmalig in der Menschheitsgeschichte dazu fähig ist, sich von pseudo-theologischen, von oben oktroyierten politischen Heilsmythen und von überzeitlichen "ewigen Werten" des Staates zu emanzipieren, und durch gemeinschaftliches politisches Handeln sowie durch eine dieses Handeln ständig begleitende wissenschaftliche Selbstreflexion, die ihr in ihrer jeweiligen historischen Lage gemäße Staatsform hervorzubringen (Freyer 1931b, 1933). Die wissenschaftliche Selbstreflexion dieser modernen politischen Gemeinschaft hat sich nach Freyer in der Soziologie bereits institutionalisiert - eine Disziplin, die ebenfalls erst durch die Epoche der Aufklärung möglich geworden sei als "Wirklichkeitswissenschaft"12.

Das Neuartige an Freyers Begriff des "politischen Volkes" nach 1925 bestand darin, daß er den Akzent auf Tat und Entscheidung, damit verbunden den Machtaspekt der Führung, vor ihre kulturelle Leistung setzte. Dieser Begriff hat nichts mehr mit kleinen Stammesgesellschaften, oder mit kultur- und lebensweltlichen Aspekten zu tun, die für Ethnologen bedeutsam sein könnten. Freyers Volksbegriff wurde nach 1933, trotz seines Aktivismus und seiner Hervorhebung des Führertums, von den nationalsozialistischen Zeitgenossen keineswege als Artikulierung ihrer "Bewegung" begrüßt - im Gegenteil vermißte man ein biologisch-rassistisches Fundament bzw. eine Volkstheorie, die auf dem Prozeß des organischen Wachstums als Entfaltung von vorneherein gegebener Anlagen gegründet sein müsse. In einem vernichtenden internen Gutachten der NS-Kontrolle kreidete man Freyer an, daß sein Postulat, die Nation sei das Volk des 19. Jhdts, eine Historisierung und Soziologisierung des Volksbegriffes bedeute. Man schloß (vollkommen zutreffend) daraus, daß Freyer "Volk" jeweils in unterschiedlichen historischen Erscheinungen verstünde, daß "Volk" also immer neue staatliche Strukturgedanken aus sich hervorbringen könne, und folgerte, daß nach Freyers Lehre heute an Stelle des Nationalsozialismus auch der Marxismus die Lage beherrschen könnte. Diese Historisierung des Volksbegriffes und darüberhinaus Freyers dezidierte Parteinahme für die idealistische Geschichtsphilosophie "kann in diesem Zusammenhang nur so gedeutet werden, daß eine auf die Biologie gegründete nationalsozialistische Geschichtsphilosophie in ihrer Möglichkeit und Notwendigkeit bestritten wird. Die Schrift ist als marxistisch schärfstens abzulehnen". (Archiv IfZ München 1933).

Die Vorstellung des Volkes als organisch gewachsene Kultureinheit, wie etwa Othmar Spann sie zur selben Zeit vertreten hat, konnte nach Freyers Ausführungen höchstens für ständische Gesellschaftsformen vor der Aufklärung und für das idealistische Konzept der Nationalkultur gelten, die eigentlichen Problem der modernen Gesellschaft im Umbruch würden darin übergangen: daß erstens das ganze Gewebe der Realbedingungen und Realfaktoren ausgeklammert bleibe (Freyer 1930: 76); daß zweitens die heute erreichte Individuation der Individuen geleugnet werde, die bei aller "Gliedhaftigkeit eine unverlierbare Existenz" beanspruchen würde (und um der konstruktiven Entwicklung der Gesellschaft auch beanspruchen solle) (Freyer 1930: 72); daß drittens in Spanns universalistischem Modell der gegliederten Ganzheit der Charakter der Offenheit der Geschichte geleugnet werde, da er damit Entwicklung nur als Emanation von bereits Angelegtem verstehen kann: "Jeder Emanatismus entwertet die konkreten Unterschiede und die konkreten Beziehungen innerhalb der Erscheinungswelt zugunsten des gemeinsamen Bezugs aller Erscheinungen auf die absolute Mitte. Jeder Emanatismus entwertet insbesondere die zeitlich-geschichtlichen Veränderungen der Wirklichkeit zugunsten ihrer metaphysischen Rangordnung [...]; die geschichtliche Veränderung wird zur bloßen Oszillation. Die Wirklichkeit ist von Anfang präformiert; [...] was sie außerdem zu sein scheint, ist Verfall oder Trug" (Freyer 1929: 235).

Freyers methodologischer Grundsatz - die Historisierung aller, auch der allgemeinsten soziologischen Strukturbegriffe (1931a: 124-129) - ist verbunden mit einem neuen Geschichtskonzept der Emergenz, das im Gegensatz zu den emanatistischen oder evolutionären Entwicklungsmodellen des 19. jahrhunderts den Aspekt der Variation und Kontingenz in den Vordergrund stellt: In jeder Situation sind mehrere Möglichkeiten der Weiterentwicklung angelegt, und eine davon wird durch Handeln aktualisiert. Handeln bedeutet immer auch Entscheidung, denn es kann niemals alles aktualisiert werden, was in der Latenz angelegt ist. Das bedeutet auch, daß die gegenwärtige Situation niemals vollständig aus der vergangenen erklärt werden kann: es kann Entwicklungsbrüche, Gabelungen und Umwälzungen geben (Üner 1992: 49 ff.). Dieses Geschichtsmodell der Diskontinuität, das die schöpferische Aktualisierung durch die handelnde Gemeinschaft hervorhebt, wurde in der Leipziger Geschichts- und Sozialphilosophie bereits seit Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts (Fechner, Wundt, Lamprecht) vorbereitet und von Hans Freyer, Schüler von Karl Lamprecht und Wilhelm Wundt, weiter entwickelt. Es ist theoretische Grundlage sowohl von Freyers politischen Schriften um 1933, als auch von Freyers Überwindung einer evolutionären Entwicklungsgeschichte zugunsten einer modernen sozialwissenschaftlichen Strukturgeschichte nach 1945 (Schulze 1989: 283 ff.)

Hans Freyer sieht seine politische Gegenwart nach dem Zusammenbruch des alten Europa im 1. Weltkrieg in einer Umwälzung, die dem Anbruch der Moderne nach der französichen Revolution vergleichbar ist, und in der sich die politische Gemeinschaft völlig neu zu bestimmen hat. Freyer ist also durchaus ein Theoretiker der Revolution, wie Rammstedt hervorhebt. Nur legt Freyer die Epochenschwelle nicht auf den Zeitpunkt 1933, sondern auf den Anbruch der industriellen Gesellschaft im 19. Jahrhundert mit ihren proletarischen Aufständen, der "Revolution von links", historisch gebunden an die Klassengesellschaft des 19. Jahrhunderts; Akteur war damals das Proletariat, das sich aus der materialistischen Entfremdung zu emanzipieren suchte. Nun, in der Gegenwart der Weimarer Republik, kündigt sich für Freyer die Antithese an: eine "Revolution von rechts" (1931b), die keineswegs gegen die Revolution von links gerichtet ist, sondern im Gegenteil diese im Sozialstaat der Bismarckzeit liquidierte, (26 f.), zu einer selbstläufigen Dialektik der Produktionsverhältnisse irrtümlich umgedeutete (10 f.) und zu einem Bekenntnis zur industriellen Welt umformulierte (41) Revolution dialektisch weitertreiben und vollenden soll; gerade die Eingliederung des Proletariats in das System der Industriegesellschaft habe die neue revolutionäre Kraft erzeugt (37). Akteur sei jetzt nicht mehr das Proletariat, das seine materiale Deprivation zu überwinden suchte, sondern das "politische Volk", das jetzt um die vorenthaltene politische Emanzipation kämpft und "die Geschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts freimachen" wird (5).

Nicht dezidiert genannte zeitgeschichtliche "Folie" Freyers war dabei sicher auch die russische Oktoberrevolution 1917, die weltweit mit Faszination betrachtet wurde. Die Sowjetunion verzeichnete in diesen Jahren erstaunliche industrielle Fortschritte, erschien 1931 als einzige politische Macht unbehelligt von der weltweiten Wirtschaftskrise und hat als Modell und Alternative gedient bei den Umstürzen der liberalen Demokratien in fast allen europäischen Staaten (Hobsbawm 1995: 99f.) In dieser Zeit erfolgte auch in der Sowjetunion eine Wendung der politischen Ziele von der sozialistischen Internationale zur Respektierung der nationalen Einheiten. Des weiteren erschien ein Jahr vor Freyers Revolution von rechts die "Theorie der permanenten Revolution" von Leo Trotzki (1930); es ist kaum von der Hand zu weisen, daß Freyer auch dazu eine Entgegnung intendierte. Freyer schließt sich außerdem einer damals weit verbreiteten öffentlichen Kritik an; den Parteien der Weimarer Republik wurde nicht nur von den Konservativen, sondern auch von der politischen Linken vorgeworfen, sie wären mit ihren Programmen im weltanschaulichen Gedankengut des 19. Jahrhunderts steckengeblieben und daher unfähig, die gegenwärtige Gesellschaft im Umbruch zu repräsentieren und deren Ziele politisch umzusetzen.

Freyers "politisches Volk" ist also ein revolutionäres Volk: "Nachdem die Gesellschaft ganz Gesellschaft geworden ist, alle Kräfte als Interessen, alle Interessen als ausgleichbar, alle Klassen als gesellschaftliche notwendig erkannt und anerkannt hat, erscheint in ihr dasjenige, was nicht Gesellschaft, nicht Klasse, nicht Interesse, also nicht ausgleichbar, sondern abgründig revolutionär ist: das Volk" (1931 b: 37). Eine berühmte dialektische Formel von Karl Marx aufnehmend, versteht Freyer das "Volk" als das "gründliche Nichts, von der Welt der gesellschaftlichen Interessen aus gedacht, denn in dieser Welt kommt es nicht vor; und das gründliche Alles, wenn man nach der Zukunft fragt, die dieser Gegenwart innewohnt" (44). Das Recht einer Revolution kann niemals durch eine Analyse der Stärkeverhältnisse bewiesen werden - "man kann ein Nichts nicht messen, und ein Alles auch nicht" - es gilt nur "Prinzip gegen Prinzip zu stellen: das Prinzip Volk gegen das Prinzip industrielle Gesellschaft" (44). Mit derartig polarisierender Dialektik wird immer eine genauere Definition, was nun "Volk" im Gegensatz zu "Gesellschaft" bedeuten soll, umgangen, ja vielmehr würde eine solche Definition für Freyer bereits den gefürchteten Rückfall in längst überholte wissenschaftliche Konzepte bedeuten; eine revolutionäre Entwicklungsdynamik kann nicht mit altbewährten Begriffen erfaßt werden. So muß Freyer das "aktive Nichts" als neues Prinzip der Geschichte vornehmlich mit negativen Bestimmungen einkreisen:

- Das "politische Volk" ist nicht Nation, wie das 19. Jahrhundert Volk verstanden und verwirklicht hatte, als Begriff, der "den Stolz auf das geschichtlich Erreichte, die Gewißheit des geschichtlichen Bestands und irgendeinen Willen zur Weltgeltung im zugemessenen Raum" versinnbildlichte. "Das Bewußtsein eines unendlich reichen geistigen Gemeinbesitzes schwingt mit. Alle Bildung schöpft aus diesem Besitz, und das Bekenntnis zu ihm verpflichtet zum treuen Festhalten an der geprägten geistigen Art, die ihn erwarb. Dieser Begriff des Volkes ist in der neuen Lage der Gegenwart überwunden." (51).

- Das "politische Volk" hat mit "Urvolk" ebenfalls nichts zu tun. Eine tiefer als der Begriff der Nation liegende Schicht: Volk als "Urkräfte der Geschichte [...], Geister, die der Natur ganz nahe waren[...], ein unmittelbares Dasein [...], Volk als Ahnungen und Verkündigungen [...], bleiben für Freyer lediglich als unspezifische Sedimente gültig und sollen als solche in den neuen Begriff des Volkes eingehen. "Nur ist zu sorgen, daß nicht auch diese Schicht als unverlierbarer Besitz und als naturhaft-selbstverständliches Sein erscheine"; denn dann wäre die Wirklichkeit die ungetrübte Darstellung dieser zugrundeliegenden Potenz, und Volk wäre "so etwas wie eine Weihnachtsbescherung" (51 f.), auch hier erlaubt Freyer keinen theoretischen Emanatismus.

Die positive Bestimmung als neues Prinzip der Geschichte ist auffallend vage - Freyer beschränkt sie auf Volk als "Sinn, der in der industriellen Gesellschaft aufgeht", als "lebendiger Kern, um den sich die Mittel des industriellen Systems zu einer neuen Welt zusammenfügen werden, wenn es gelingt sie zu erobern" (1931b:52); da vom neuen Prinzip Volk her eine totale Neuordnung der Welt erfolge, sei es nicht möglich, die Struktur dieses "werdenden Volkes" jetzt schon genau zu bestimmen. Gleichwohl stellt er der Soziologie drei konkrete Aufgaben: Es muß gefragt werden "erstens nach der Struktur des herrschenden Systems, innerhalb dessen sich die Revolution bildet; zweitens nach den Kräften, die sich an dem neuen Gegenpol aufladen, nach ihrer Herkunft und nach der Notwendigkeit, mit der sie ihm zuströmen; und drittens nach der Richtung, die diesen Kräften und ihrer Revolution innewohnt" (53). Die Richtung benennt er: "von rechts", jedoch wiederum nur negativ bestimmend, daß Volk zum einen keine Gesellschaftsklasse wäre, daß also rechts nicht die Fortsetzung der Revolution von links mit anderen Mitteln sein könne; zum anderen könne rechts auch nicht Reaktion heißen. Freyer nimmt den Begriff der Revolution beim Wort, wenn er immer wieder hervorhebt, daß die Revolution quer durch alle bisherigen Interessengegensätze hindurchbräche, weil hier ein umfassendes Freimachen aus dem alten Gesamtsystem und eine totale Umordnung nach einer neuen Generalformel stattfinde (54). Seine positive Definition des Schlagwortes "von rechts" ist ebenso vieldeutig: Emanzipation des Staates. Der Staat, der in der Epoche der industriellen Gesellschaft immer nur Beute, bestenfalls vorsichtiger Schlichter der Wirtschaft war, wird in der Synthese mit dem politischen Volk zum ordnenden Prinzip gegen die Industriegesellschaft. Auch von diesem neuen Staat gibt Freyer keine politische Struktur oder Ordnung an, aber sehr deutlich dessen Bedeutung als realer Faktor im Vollzug der Revolution: Die Revolution von rechts läuft über den Staat, nicht in dem Sinne, daß eine unterdrückte Gesellschaftsklasse sich des Staates taktisch bemächtige, um ihre gesellschaftlichen Interessen durchzusetzen; vielmehr das Volk wird Staat, erwacht zu politischem Bewußtsein, und als "politisches Volk" wird es zum selbständigen Prinzip gegen die wirtschaftlichen Interessen der Industriegesellschaft, ist also die neue, alles umordnende Generalformel (61).

Es ist ein Modell des plebiszitären Führerstaates13, die Freyers Arbeiten zum "politischen Volk" bis 1934 bestimmt. Ganz im Gegensatz dazu steht seine Schrift Pallas Athene: Ethik des politischen Volkes 1935, die bestenfalls eine Ethik des totalen Ausnahmezustandes genannt werden kann; mit dem "politischen Volk" im obigen Sinn hat sie nichts mehr zu tun. Dies erscheint nur noch als "Block des Volkes", an dem der Staatsmann wie ein Bildhauer arbeitet (1935: 98). Die Maximen dieser Ethik sind nicht mehr generalisierbar, vielmehr werden "Ethik" und "bürgerliche Moral" gegeneinander ausgespielt, wird dem "Gewissen aus der Welt des kleinen Mannes" ein Gewissen "mit politischem Format", eben Pallas Athene, die "Göttin der politischen Tugend" gegenübergestellt (30 f.), erinnert der Aufbruch in seiner Doppeldeutigkeit fatal an Vergewaltigung. Das folgende Freyersche Zitat reicht von der magischen Beschwörung bis zum blanken Zynismus und läßt kaum einen Interpretationsspielraum offen. "Immer handelt es sich darum, im Leben [...] ein neues magisches Zentrum aufzurichten, auf das die Menschen nun hinstarren, welcher Segen von ihzm komme oder welches Unheil. Das ist eine Vergewaltigung der menschlichen Natur, und die Menschen entgleiten der Politik immer wieder, weil sie mit ihren eigenen Dingen so viel zu tun haben. Aber die Leistung der politischen Tugend besteht darin, daß diese Vergewaltigung immer aufs neue gelingt, so gründlich gelingt, daß die Erde nicht bloß Wohnhäuser und nützliche Anstalten, sondern Tempel, Burgen und Paläste trägt. Aus dem arbeitssamen und verspielten Menschenwesen [...] eine Heldenschar zu machen für ferne Ziele, ihm, das gegen diesseitige Autoritäten im Grund skeptisch ist [...], den absoluten Glauben an die sichtbare Macht aufzuzwingen, ihm das so gerne lebt, den freiwilligen Tod zu versüßen , ihm eine neue Ehre einzupflanzen, die nur Opfer kostet, kurz diese weiche Materie in ein hartes Metall zu verwandeln, mit dem man stoßen und schlagen kann - das ist die merkwürdige Alchimie, die immer neu erfunden werden muß, wenn politisch etwas geschehen soll" (50 f.). Freyer scheint hier nichts weniger als sein eigenes Werk und seine Gelehrtenkarriere zu verraten, denn Die "Ethik des Willens" ist vor allem auch gegen die theoretische Vernunft gerichtet, die Ausschau nach dem Ganzen hält, und die Begründung sucht, damit aber die Tat begrenzen könnte. (21 f.). Aus der kritischen Sicht der Emigranten wurde diese Kombination von Desperado-Mentalität und hochgepriesener Fahnentreue mit den Verbrechen des Dritten Reiches in Verbindung gebracht - René König und Herbert Marcuse haben die politischen Konsequenzen klar herausgestellt (König 1975: 135 f., Marcuse 1936).

Dennoch ist nicht zu übersehen, daß es auch in dieser Schrift eine zweite Sichtweise gibt, aus der bereits die Enttäuschung über einen "zweitrangigen Principe", über die Geistlosigkeit der an die Macht gelangten nationalsozialistischen Bewegung und das Denken in "Räuberkategorien" zu entnehmen ist. "Es ist armselige Romantik zu glauben, daß in der politischen Welt der Instinkt den rechten Weg fände, und daß der Staatsmann um so genialer sei, je mehr er sich auf sein Gefühl statt auf seinen Verstand verlasse [...]" (112). Und eines erläßt die Göttin der politischen Tugend ihren Lieblingen nicht: "daß ihre Handlungen Adel. Reinheit und die Spannung des guten Gewissens haben [...] Wer beim ersten Schritt, den er aus der Welt der bürgerlichen Arbeit heraustut, dem Kitzel der Zwecke, die die Mittel heiligen, verfällt und sich höchst politisch dünkt, wenn er aus großen Niederträchtigkeiten eine kleine Intrige zusammensetzt, beweist damit nur, daß er lieber in der Welt der bürgerlichen Arbeit hätte bleiben sollen. [...] Ein Principe aus zweiter Hand ist immer nur eine traurige oder je nachdem eine lächerliche Figur" (30 f.) - das konnte kaum ein Aufruf zur Konsolidierung der 1935 gegebenen Verhältnisse sein. Eine Deutung dieser Schrift, die sich nicht zu einem konsistenten Bild zusammenschließt, ist ohne Nachweis der Adressaten, die Freyer ansprechen wollte, nicht möglich. Als Aufruf zur nationalsozialistischen Revolution kam sie 1935 um einige Jahre zu spät. Der von Freyer ursprünglich gewählte Untertitel Ethik der konservativen Revolution, der vom Verleger Niels Diederichs als zu brisant korrigiert wurde (Universitätsarchiv Jena), nennt allerdings die Adressaten. War die Schrift Antwort auf die Mordaktion der Gestapo und SS am 30. Juni 1934 an Ernst Röhm, Schleicher, Gregor Strasser und anderen Feinden, derer sich Hitler damit entledigt hatte - war sie konzipiert, um eine "Zweite Revolution" einzuleiten? Dafür spricht Freyers Stil, der mehr einem Kreuzzugsaufruf als einer ethischen Abhandlung entspricht, aber es gibt bisher keine Nachweise einer Verbindung Freyers zu dieser Gruppe. Freyer hatte nie Sympathien für die Wehrverbände der Parteien während der Weimarer Republik gehegt, und so wird er wohl kaum eine Unterstützung des Machtkampfes der SA bzw. Ernst Röhms gegen die SS intendiert haben. Welche konkrete politische Bewegung er mit der "Pallas Athene" zur Aktion aufrufen wollte, kann zur Zeit noch nicht nachgewiesen werden.

Diese Schrift stellt einen paradigmatischen Fall dar für die anfangs erwähnten "Abwehrmechanismen" des geistigen Schaffens in totalitären politischen Systemen. Als heimliche Botschaft einer Verschwörergemeinschaft konnte sie nur von den Eingeweihten entziffert werden. Sowohl René König (1975) als auch Herbert Marcuse (1936), die Deutschland verließen, haben sie als Fanfare für den Nationalsozialismus gelesen, und auch alle nicht zum engsten Kreis um Freyers zählenden Kollegen konnten sie nur als solche einschätzen. Die Schwierigkeiten der Interpretation liegen offenbar darin, daß hier Innen- und Außenperspektive weit auseinandertreten. Aus der Innenperspektive der Beteiligten verstanden, stellte die reine Willensethik mit ihren Kategorien "Tat" und "Entscheidung", die schon bei Fichte gewissermaßen als Kategorien des Widerstands literaturfähig gemacht worden sind, keineswegs eine Äußerung der politischen Reaktion oder eine Festschreibung der bestehenden Verhältnisse dar, sondern konnten die noch aufrechterhaltene Hoffnung in die Kraft des politischen Volkes oder eines echten politischen Führers beschwören. Das Verhängnisvolle daran ist, daß sowohl NS-Gegner wie NS-Kämpfer in der gleichen Umwelt an die gleichen Adressaten die gleiche Sprache sprechen mußten. Solange ihre Schriften noch in Deutschland publiziert wurden, konnten auch die Gegner ihre Botschaften nur in den gleichen Allegorien verstecken. Aus der Außenperspektive, entweder in der Emigration oder im zeitlichen Abstand, verliert man den Sinn für den zeithistorischen Kontext, sieht man keine Notwendigkeit, in Allegorien zu sprechen - also kann den Botschaften nur ihr aktueller Sinn, von außen gesehen, unterstellt werden; und der ist eben Aktivismus, Gewalt und Diktatur.

Für die Wirkungsgeschichte war Freyers Pallas Athene zweifellos die verhängnisvollste Schrift seines Gesamtwerkes, denn sie bildete die Folie, auf die seither Freyers Gegner sowohl seine frühen, wie auch die späteren Werke projizierten. Es wurde nicht mehr erkannt, daß Freyers Pallas Athene aus der werkimmanenten Entwicklung vollkommen ausbricht, daß er, wie oben dargelegt, zur gleichen Zeit die Reziprozität von Herrschaft und Volk konzipiert hat und die Aufgaben der Wissenschaft, entgegen der Pallas Athene, mit Verve vertreten hat. Deshalb soll nun die Betrachtung wieder zu dieser zurückkehren.

Die Stunde der Soziologie.

In der revolutionären Gegenwart, die diese neue Selbstfindung, Willensbildung und geschichtliche Leistung des Volkes verlangt, schlägt die Stunde einer qualitativ völlig neuen Wissenschaft, die Stunde der Soziologie: Im Freyerschen Konzept ist sie als bewußte wissenschaftliche Lebensgestaltung, Planung und Sozialtechnik der Nachweis dieses historischen Umschlags zu einem neuen Zeitalter der menschlichen Bewußtwerdung. Allerdings hat Freyer diesen Umschlag zur wissenschaftlichen Bewußtwerdung nicht auf den politischen Umbruch 1933 bezogen, wie seine Kritiker ihm vorwerfen (u.a. König 1987), sondern bereits in der Epoche der Aufklärung gesehen: Durch die emanzipatorischen geistigen Strömungen der Aufklärung ist Soziologie als Nachdenken der Gesellschaft über sich selbst erst möglich geworden - sie ist seitdem als "Wirklichkeitswissenschaft" systematisierte gesellschaftliche Selbsterkenntnis. Für seine Gegenwart formulierte Freyer daraus die große Erwartung, daß die Soziologie auch jetzt als Medium der politischen Emanzipation oder "Volkwerdung" fungiert; denn, indem sie mit der kontinuierlichen Selbstanalyse auch die ständige Neuformulierung gesellschaftlicher Ziele leistet und so das Substanzielle eines Zeitalters ausdrückt, treibt sie die Veränderungsprozesse als gesellschaftsimmanente Dialektik weiter und kann also den Hiatus zwischen Theorie und Praxis überbrücken (Freyer 1930: 300-307). Die Kluft zwischen Idealdialektik und Realdialektik ist in Freyers Wirklichkeitswissenschaft aufgehoben (Üner 1992: 196-214).

Freyers logische Grundlegung dieser radikalen Neubestimmung der Soziologie: "Soziologie als Wirklichkeitswissenschaft" (1930) erschien im gleichen Jahr wie die deutsche Erstveröffentlichung der Frühschriften von Karl Marx und hat nicht nur im mühsamen innerwissenschaftlichen Diskurs um die Gegenstandsbestimmung der Soziologie Aufsehen erregt, sondern auch die unterschiedlichsten weltanschaulichen Kontroversen ausgelöst. An der zeitgenössischen Rezeption Freyers fällt auf, daß nur von zwei Rezensenten, dem Philosophen Josef Pieper (1931) und dem Soziologen Karl Mannheim (1932: 40), eine Beziehung von Freyers Konzeption der Soziologie als gesellschaftliche Selbstreflexion zu den theoretischen Auseinandersetzungen in der damaligen Disziplin hergestellt und dabei auch die theoretischen Kurzschlüsse aufgedeckt wurden. Alle anderen beschränkten sich darauf, sie daran zu messen, ob sie mit den eigenen weltanschaulichen Überzeugungen übereinstimmte oder nicht. Und so reicht die zeitgenössische Kritik an Freyer von "Kryptomarxismus" bis zu "Überfaschismus" (Üner 1992: 61 ff.). Der Heidegger-Schüler Herbert Marcuse begrüßte Freyers Buch als die einzige radikale theoretische Selbstbesinnung überhaupt, die seit Max Weber nicht mehr aufgenommen worden wäre (Marcuse 1931).

Dieses "reflexive Paradigma" der modernen Wissenschaft ist nicht alleine Freyers Domäne; er teilt es mit den zeitgenössischen Richtungen der Phänomenologie, der Lebensphilosophie, der Existenzphilosophie, oder auch mit den technikphilosophischen Visionen der Befreiung des Menschen von der Naturgebundenheit zu einer durch die moderne Technik möglich gewordenen Selbstgestaltung (N. Berdjajew, F. Dessauer). Helmuth Plessner hat die moderne menschliche Bewußtwerdung für die damals mit ähnlichem Anspruch einer neuen Leitwissenschaft auftretende Philosophische Anthropologie prägnant zusammengefaßt in der Formel: "Der Mensch ist sich selber nicht mehr verborgen, er weiß von ihm, daß er mit ihm, welcher weiß, identisch ist." (Plessner 1981: 401). Der Gedanke der wissenschaftlichen Selbsterkenntnis blieb auch keineswegs der philosophischen Reflexion vorbehalten; er lieferte eine äußerst publikumswirksame Begründung für die Institutionalisierung der neuen sozialwissenschaftlichen Disziplinen - von der Soziologie über die politischen Wissenschaften bis zur philosophischen Anthropologie - im Zuge der Universitätsreform der zwanziger Jahre. Die diesbezüglichen Stellungnahmen des Soziologen Karl Mannheim (1932) oder des preußischen Kultusministers Carl Heinrich Becker (1925) stützen sich gleichermaßen auf die durch die Sozialwissenschaften möglich gewordene Selbsterkenntnis der politischen Gemeinschaft, und die Förderung dieser Selbstreflexion wird als wichtigste öffentliche Aufgabe, insbesondere der Volksbildung, deklariert, um eine mündige politische Willensbildung möglichst aller Bürger in Gang zu bringen.

Freyers Wirklichkeitswissenschaft und das Wissenschaftsverständnis seines damaligen Leipziger Schüler- und Kollegenkreises waren von einem lebenspraktischen Pathos getragen und konnten von weltanschaulichen Erneuerungsbewegungen aller Couleurs als Lebensphilosophie übernommen werden, denn sie boten jedem das verheißungsvolle Ziel der "Selbstfindung". Freyer verfaßte populärphilosophische Aufrufe, die den unterschiedlichsten weltanschaulichen Gruppierungen zur Selbstreflexion verhelfen sollten. Er selbst war dabei nie Mitglied einer politischen Partei, nie organisatorisch aktiv in einer der weltanschaulichen Erneuerungsbewegungen, und erfüllte damit beispielhaft die von ihm charakterisierten Rolle des "Führers" als Medium des Volkswillens, der dem "politischen Volk" nur so weit Rat geben darf, als es zu seiner Selbstfindung bedarf.

Dieses aktivistische und existentialistische Konzept hat Freyer selbst nicht lange aufrechterhalten; schon 1933 verschwindet der Begriff "Wirklichkeitswissenschaft" in Freyers Schriften, und es deutet sich eine Überwindung des radikalen Aktivismus an durch den Begriff der Planung, die nur langfristig möglich ist und eine stabile politische Macht voraussetzt, welche jedoch nach wie vor durch den Gemeinschaftswillen getragen sein muß (Freyer 1987). Herrschaft stellt erstens ein reales Machtverhältnis dar, das immer auf der Legitimation durch die Teilnehmer beruhen muß; zweitens kann Herrschaft nicht beschränkt werden auf "Repräsentation" i.Sinne einer "Spiegelung" oder Abbildung einer Gemeinschaft, denn auch in der Willensgemeinschaft sind die Inhalte nicht immanent vorgegeben, sondern sie müssen erst in der Auseinandersetzung und in fortlaufender Integrationsleistung geschaffen werden. Das "politische Volk" ist eine "geschichtliche Ganzheit, deren Integration niemals abggeschlossen ist (1987: 39 f., 70).

Aufschlußreich zur Wirkungsgeschichte Freyers ist eine Arbeit seines zeitweiligen Kollegen und Dozenten am Freyerschen Institut, des Staatsrechtlers Hermann Heller, dessen Staatslehre (1933) ohne Freyers "Soziologie als Wirklichkeitswissenschaft" nicht entstanden wäre. Auch Heller geht mit dem Prinzip der Aktualisierung den Antagonismus von Staat und Volk an: Eine durch Praxis der Volksgemeinschaft ständig hervorgebrachte Rechtsanschauung soll als "Imperativ einer Gemeinschaftsautorität" die Staatsakte determinieren, um zu einer Integration von Staat und Gesellschaft zu kommen. Auch er will diese Integration mit Hilfe der Soziologie herbeiführen - sie ist, wie bei Freyer, sowohl Wissenschaft als auch Selbstreflexion einer Gemeinschaft und politische Ethik. Hellers Arbeit, die übrigens zur Programmschrift der SPD der Nachkriegs-Bundesrepublik erkoren wurde, macht deutlich, daß das Leipziger Theorem der politischen Praxis oder Aktion des Volkes - im Zusammenwirken mit anderen Einflußfaktoren und ohne existentialistisches Pathos des "Werdens" - wissenschaftlich durchaus ergiebig sein konnte.

Die Wendung zum Politischen - von der Teleologie zur Teleonomie.

Nimmt man Freyer hinsichtlich der konkreten Aufgaben der Soziologie beim Wort, so vermißt man in der radikal polarisierten Revolutionsdialektik sowohl eine genauere Analyse der Strukturen wie der politischen Prozesse. In den Arbeiten zur Soziologiegeschichte (u.a. Rammstedt 1986: 26ff.), wird übereinstimmend festgestellt, daß die Sozialwissenschaftler allesamt Schwierigkeiten hatten, die Ereignisse um 1933 angemessen zu erklären. Die zeitgenössische Soziologie konnte den Umbruch weder als soziale noch als politische Revolution kennzeichnen; eine Deutung im Sinne einer vorübergehenden Abweichung von normaler Entwicklung mußte ebenfalls ausgeschlossen werden; auch eine Begründung aus ökonomischen, sozialen oder politischen Einzelfaktoren konnte diese Krise nicht angemessen erklären. So blieb für die im Geschehen selbst verstrickten Gelehrten im allgemeinen nur eine geschichtsphilosophische Deutung, die nicht nur bei Freyer stark mythologische Züge bekam, die jedoch innerhalb des Freyerschen Systems eine theoretische Begründung erfährt: Aufbauend auf seiner bereits erwähnten Postulierung, daß soziologische Begriffe immer historisch gebunden, also wissenschaftlicher Ausdruck einer konkreten historisch verortbaren Gesellschaft sein müßten, ergibt sich für die Soziologie die Aufgabe der kontinuierlichen Reflexion über den "historischen Ort" der gegenwärtigen Gesellschaft - insofern sind für Freyer Geschichtsphilosophie und Soziologie überhaupt nicht voneinander zu trennen (eines der zahlreichen Postulate, die Freyer mit der Frankfurter Schule verbindet). Nun muß insbesondere in einer Epoche des krisenhaften Wandels die geschichtsphilosophische Reflexion in der Gegenwart abbrechen, um nicht wieder den Fehler der Extrapolierung von Strukturen aus der Vergangenheit in die Zukunft zu begehen - im Umbruch muß die Zukunft offen bleiben, denn hier ist in extremem Maße "der Hiatus zwischen Gegenwart und Zukunft nicht durch dinghafte Entwicklung, sondern durch den Willen überbrückt [...], ist freie menschliche Praxis" (1930: 307).