« Deux armées qui se battent, c’est une grande armée qui se suicide. » (Henri Barbusse)

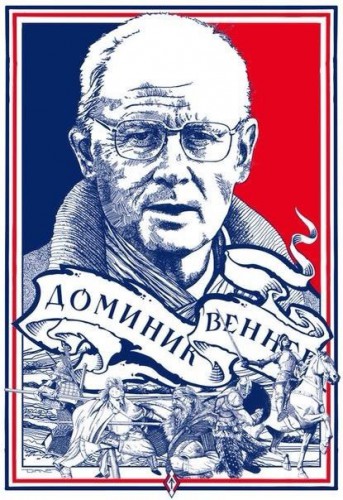

2008 : nous allons bientôt célébrer le 90ème anniversaire de l’armistice du 11 novembre 1918. Mais c’est aussi l’année où le dernier Poilu allemand s’est éteint. Clin d’œil du destin : le dernier Poilu français a eu l’élégance de ne lui survivre que quelques semaines. Bien sûr, il reste quelques survivants italiens, anglais ou russes, mais il est très symbolique que les deux derniers « fraternels adversaires » se soient suivis de si près dans la tombe. Il s’agit d’abord ici de rendre hommage à tous ces combattants européens. Une ou plutôt deux générations sacrifiées sur l’autel de l’aveuglement des politiques. Nous ferons largement appel aux récits de ceux qui ont vécu l’enfer des tranchées, quelle que soit leur sensibilité : communiste, pacifiste, catholique, nationaliste, fasciste ; l’un était provençal, l’autre était prussien… peu importe, tous appartenaient à ce peuple d’Europe qu’on a assassiné. Nous laisserons donc une large place aux citations de ces hommes, empreintes d’une brutale beauté. Mais c’est aussi un événement aux conséquences incommensurables, puisqu’il a provoqué non seulement la ruine de l’Europe, mais aussi son affaiblissement définitif. On relira également à ce sujet l’excellent ouvrage de Dominique Venner, Le Siècle de 1914. Enfin, c’est une terrible leçon pour les hommes d’aujourd’hui : tout peut recommencer, tout recommencera sans doute, demain…

LES DERNIERS JOURS DU VIEUX MONDE

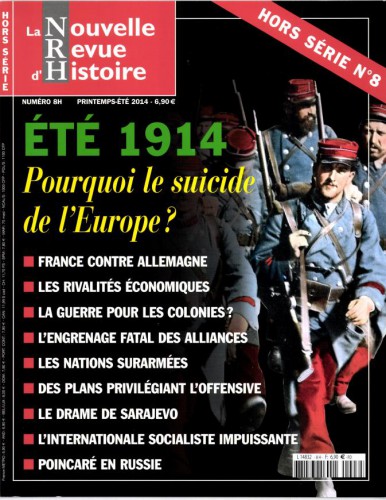

Comment a-t-on pu en arriver là ? Il est certain qu’aucun des protagonistes du déclenchement du conflit n’avait imaginé le déroulement de cette guerre et l’effondrement du vieux monde qu’il engendrerait. S’ils avaient su… En ce début de XXème siècle, l’Europe n’a jamais été aussi puissante. Dans les décennies précédentes, elle a fini de se partager le monde. Dans les domaines intellectuel, scientifique, technique, militaire, commercial, bancaire, elle règne en maître. Toutes les anciennes puissances impériales sont à ses pieds : la Chine, le Japon… De l’autre côté de l’Atlantique, un géant est en train de s’éveiller, mais peu y font attention ; seule l’Espagne l’a vérifié à ses dépens pour avoir été la première puissance européenne vaincue par une nation non européenne et avoir ainsi perdu ses possessions nord-américaines (1898). Personne, non plus, ne s’est inquiété de la défaite de la Russie face au Japon (1904). Pour tous les Européens, l’Europe reste l’omphalos, le nombril du monde. Le réveil sera terrible.

La Grande-Bretagne est encore la première puissance mondiale. Les Anglais rêvent d’un monde dominé par eux ; s’ils échouent, le témoin ne tardera pas à être passé aux cousins d’Amérique. L’Allemagne est la nation qui monte en puissance, dans tous les secteurs, ce qui ne laisse pas d’inquiéter les Anglo-Saxons. L’Autriche-Hongrie se voit bien affaiblie par les tendances centrifuges des peuples qui la composent. Quant à la Russie, atteinte par sa défaite contre le Japon, elle est en pleine évolution, mais le temps joue contre elle. Tout ce petit monde se connaît bien : rois et empereurs ont des liens de parenté : Guillaume II n’est-il pas le neveu d’Edouard VII ?

Parmi les Etats qui comptent en ce début de XXème siècle, il faut ajouter l’Empire ottoman, à l’agonie, dont le dépeçage vient de commencer avec les guerres balkaniques. Enfin, il y a la France, une anomalie dans cette Europe monarchiste et impériale. Une France qui exporte son idéologie égalitaire depuis qu’elle a décapité son roi, une idéologie mortifère pour l’Europe de la volonté de puissance. Une France arrogante, sûre de sa supériorité intellectuelle sur ces Etats aux « régimes du passé. » C’est enfin une France qui supporte mal la comparaison avec son rival oriental. Si les niveaux démographique et économique des deux Etats étaient équivalents en 1870, la population allemande dépasse celle de la France de 55% en 1914 (68 millions contre 40) ; quant au PIB, il a triplé en Allemagne et seulement doublé en France pendant ce même demi-siècle. Sur le plan militaire, les forces françaises et allemandes semblent s’équilibrer : 30 000 officiers et 750 000 soldats de part et d’autre, mais la puissance militaire et industrielle allemande est bien supérieure à celle de la France. Les événements le confirmeront : « Du haut d’une colline, j’avais vu l’armée française déployée dans la plaine sous de vagues canonnades comme une vieille anecdote, oubliée longtemps par le Temps et soudain reprise par lui pour être sévèrement liquidée. Cette armée qui déployait partout ses rubans bleu et rouge rappelait les tableaux de bataille peints vers 1850. Archaïque, ahurie, prise en flagrant délit d’incurie et de jactance, essayant vaguement de crâner, pas très sûre d’elle. J’avais vu passer des généraux, l’air triste, suivis de cuirassiers, conçus par leurs pères pour mourir à quelque Reichshoffen. En face, on ne voyait rien, les Allemands se confondaient avec la Nature ; je trouvais que cette philosophie avait du bon» (Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, La Comédie de Charleroi).

Ces grandes puissances se concurrencent, mais qui penserait que ces querelles de famille vont dégénérer dans l’abomination ? Des crises, il y en a eu tout au long de cette fin du XIXème et de ce début du XXème, mais elles ont été résolues par la diplomatie, avant qu’il ne soit trop tard : le camouflet de Fachoda subi par la France face à l’Angleterre (1898), les rivalités coloniales entre la France et l’Allemagne (crises de Tanger en 1905 et d’Agadir en 1911). Mais les ambitions autrichiennes et russes se heurtent dans les Balkans ; la tension y est avivée par les guerres balkaniques de 1912-1913. Et il y a surtout le contentieux franco-allemand lié à l’annexion de l’Alsace et de la Lorraine par l’Allemagne. Un peu plus de quarante années à seriner à deux ou trois générations la haine de l’autre : « Et la Revanche doit venir, lente peut-être, mais en tout cas fatale, et terrible à coup sûr ; la haine est déjà née et la force va naître ; c’est au faucheur de voir si le champ n’est pas mûr. » (Paul Déroulède). Le Kaiser est persuadé que « la France veut la guerre » et le pangermanisme est en fleurs. La Russie veut la destruction de l’Autriche-Hongrie au nom du panslavisme. La Grande-Bretagne veut réduire cette Allemagne qui lui fait de l’ombre. Depuis quelques années, toutes les puissances renforcent leur armement. Des alliances parfois contre nature se sont nouées : la Triple Entente qui réunit une France et une Angleterre réconciliées, ainsi que la Russie, pourtant jugée inconciliable avec la seconde ; d’autre part, la Triplice où l’on trouve côte à côte l’Allemagne, menacée à l’Est comme à l’Ouest, l’Autriche-Hongrie et l’Italie, ces dernières ayant pourtant des intérêts rivaux dans les Balkans. Finalement tous veulent la guerre : il suffira d’une étincelle.

LES EUROPEENS APPRENNENT LE NOM DE SARAJEVO

C’est à Sarajevo, l’ancienne capitale de la Roumélie assujettie aux Turcs, qu’elle se produit. L’Autriche avait reçu la tutelle sur la Bosnie-Herzégovine par le traité de San Stefano en 1878. En 1908, elle a mis l’Europe devant le fait accompli en l’annexant purement et simplement. Acte inadmissible pour les nationalistes serbes. Le 28 juin 1914, un exalté, Gavrilo Princip, assassine l’archiduc François-Ferdinand, l’héritier de la couronne, sur un pont de Sarajevo. L’incident aurait pu en rester là ou n’avoir que des conséquences restreintes ; au pire, l’Autriche aurait pu avoir, de la part des autres puissances continentales, l’autorisation de « punir » la Serbie... Mais cela, la Russie n’en veut à aucun prix. Et l’effrayante logique des alliances internationales va transformer cet attentat somme toute anodin en détonateur de la Première Guerre mondiale. « En cet été 1914, l’équilibre fragile et compliqué de l’Europe, les combinaisons des chancelleries et les calculs des hommes politiques ont été emportés en quelques instants par le complot d’un obscur groupuscule d’officiers et d’adolescents d’un lointain pays balkanique, qui ne savaient rien de la politique mondiale et ne voulaient qu’une chose : assouvir leur haine de l’Empire austro-hongrois » (Dominique Venner).

C’est à Sarajevo, l’ancienne capitale de la Roumélie assujettie aux Turcs, qu’elle se produit. L’Autriche avait reçu la tutelle sur la Bosnie-Herzégovine par le traité de San Stefano en 1878. En 1908, elle a mis l’Europe devant le fait accompli en l’annexant purement et simplement. Acte inadmissible pour les nationalistes serbes. Le 28 juin 1914, un exalté, Gavrilo Princip, assassine l’archiduc François-Ferdinand, l’héritier de la couronne, sur un pont de Sarajevo. L’incident aurait pu en rester là ou n’avoir que des conséquences restreintes ; au pire, l’Autriche aurait pu avoir, de la part des autres puissances continentales, l’autorisation de « punir » la Serbie... Mais cela, la Russie n’en veut à aucun prix. Et l’effrayante logique des alliances internationales va transformer cet attentat somme toute anodin en détonateur de la Première Guerre mondiale. « En cet été 1914, l’équilibre fragile et compliqué de l’Europe, les combinaisons des chancelleries et les calculs des hommes politiques ont été emportés en quelques instants par le complot d’un obscur groupuscule d’officiers et d’adolescents d’un lointain pays balkanique, qui ne savaient rien de la politique mondiale et ne voulaient qu’une chose : assouvir leur haine de l’Empire austro-hongrois » (Dominique Venner).

Quelques esprits lucides comme Jean Jaurès, Joseph Caillaux ou le maréchal Lyautey, s’opposent à cette guerre dont ils pressentent qu’elle ne sera pas une guerre comme les autres. Ils prêchent dans le désert. En Allemagne, le chancelier Bethmann-Hollweg, et en Autriche, le Premier ministre de Hongrie, le comte Tisza, se révèlent tout aussi impuissants à enrayer le cours des événements. Face à eux, les va-t-en guerre sont bien plus entreprenants, en particulier en Russie et en Autriche-Hongrie : Nicolas II, poussé par son ministre des Affaires étrangères, Sazonov, décidé à détruire l’Autriche-Hongrie ; l’Empereur autrichien François-Joseph, âgé de 84 ans et manipulé par le Premier ministre autrichien, Berchtold. Ils ne sont pas les seuls : en France, Poincaré y voit l’occasion de venger l’humiliation de 1870 ; en Allemagne, Guillaume II écoute aussi les avis bellicistes du général von Moltke et du grand état-major.

Tout au long du mois de juillet, le destin de l’Europe reste comme suspendu. Les hommes de bonne volonté finiraient-ils par l’emporter ? Hélas, le 28, l’Autriche déclare la guerre à la Serbie ; le 30, la Russie mobilise. Jaurès est assassiné par Raoul Villain le 31. A ses funérailles, Léon Jouhaux, patron de la CGT, déclare : « Acculés à la lutte, nous nous levons pour repousser l’envahisseur, pour sauvegarder le patrimoine de civilisation et d’idéologie généreuse que nous a légué l’Histoire. » Répliquant à la Russie, l’Allemagne mobilise le 31 juillet et lui déclare la guerre le 1er août. La France l’imite : « La mobilisation n’est pas la guerre », déclare hypocritement celui qu’on surnomme « Poincaré-la-Guerre ». Et L’Humanité, le journal de Jaurès, écrit : « Des entrailles du peuple, comme des profondeurs de la petite et de la grande bourgeoisie, des milliers de jeunes gens, tous plus ardents les uns que les autres, quittant leur famille, sans faiblesse et sans hésitation, ont rallié leurs régiments, mettant leur vie au service de la Patrie en danger.» L’Allemagne attaque simultanément la Belgique et la France le 3. La Grande-Bretagne rentre dans cette danse macabre le 5. « Mais songe donc que nous sommes presque tous du peuple et en France aussi la plupart des gens sont des manœuvres, des ouvriers et des petits employés. Pourquoi donc un serrurier ou un cordonnier français voudrait-il nous attaquer ? Non, ce ne sont que les gouvernements. Je n’ai jamais vu un Français avant de venir ici, et il en est de même de la plupart des Français en ce qui nous concerne » (Erich Maria Remarque, A l’Ouest, rien de nouveau).

LA GRANDE ILLUSION

Dans chaque camp, on est persuadé que les combattants – forcément victorieux – seront rentrés pour l’hiver. Ce sera une partie de plaisir. Guillaume II lui-même parle d’une « guerre courte, fraîche et joyeuse. » Les Français crient : « A Berlin ! » et les Allemands « Nach Paris ! » On ose : « Ca doit être superbe, une charge, hein ? Toutes ces masses d’hommes qui marchent comme à la fête ! Et le clairon qui sonne dans la campagne… et les petits soldats qu’on ne peut retenir et qui crient : « Vive la France ! » ou bien qui meurent en riant !...» (Henri Barbusse, Le Feu).

Les hommes ne sont pas résignés, ils n’ont pas l’esprit munichois avant la lettre, le pacifisme les dégoûte : « Jamais tant d’hommes à la fois n’avaient dit adieu à leur famille et à leur maison pour commencer une guerre les uns contre les autres. Jamais non plus des soldats n’étaient partis pour les champs de bataille, mieux persuadés que l’affaire les concernait personnellement » (Jules Romains, Les hommes de bonne volonté). Seuls les paysans, normands, souabes ou moujiks, porteurs du bon sens de la terre, savent que déjà ils vont manquer les moissons, et que le pire est sans doute à venir… « Les fleurs, à cette époque de l’année, étaient déjà rares ; pourtant on en avait trouvé pour décorer tous les fusils du renfort et, la clique en tête, entre deux haies muettes de curieux, le bataillon, fleuri comme un grand cimetière, avait traversé la ville à la débandade. Avec des chants, des larmes, des rires, des querelles d’ivrognes, des adieux déchirants, ils s’étaient embarqués » (Roland Dorgelès, Les Croix de Bois). D’autres pleurent déjà une Europe qui se meurt : « J’entendais les explosions de la chimie au fond de ces souterrains, de ce labyrinthe commun, où cinq cents Normands et cinq cents Saxons – gens de même race, sans doute, o patries abusivement partagées – se rejoignaient et se mêlaient » (Drieu la Rochelle).

Nul n’imagine que le progrès technique a définitivement périmé les guerres de soldats au profit des guerres de masses et de matériel et des boucheries sanguinaires. La Guerre de Sécession a pourtant fait 630 000 morts en quatre ans aux Etats-Unis ! « Les hommes n’ont pas été humains, ils n’ont pas voulu être humains. Ils ont supporté d’être inhumains. Ils n’ont pas voulu dépasser cette guerre, rejoindre la guerre éternelle, la guerre humaine. Ils ont raté comme une révolution. Ils ont été vaincus par cette guerre. Et cette guerre est mauvaise, qui a vaincu les hommes. Cette guerre moderne, cette guerre de fer et non de muscles. Cette guerre de science et non d’art. Cette guerre d’industrie et de commerce. Cette guerre de bureaux. Cette guerre de journaux. Cette guerre de généraux et non de chefs. Cette guerre de ministres, de chefs syndicalistes, d’empereurs, de socialistes, de démocrates, de royalistes, d’industriels et de banquiers, de vieillards et de femmes et de garçonnets. Cette guerre de fer et de gaz. Cette guerre faite par tout le monde, sauf par ceux qui la faisaient. Cette guerre de civilisation avancée » (Drieu la Rochelle).

Le plan allemand, initié par le feld-maréchal comte von Schlieffen, prévoit de tourner les forces défensives françaises par la Belgique puis de fondre sur Paris. Il est en effet indispensable de remporter rapidement la victoire sur le front occidental pour pouvoir se retourner ensuite contre les Russes. En quelques semaines, les six armées allemandes bousculent les forces françaises sur plusieurs centaines de kilomètres. La route de Paris semble ouverte. Mais lors d’un sursaut extraordinaire, les Français s’arc-boutent sur la Marne et stoppent les Allemands, arrachant au général von Moltke cet aveu : « Que des hommes, après avoir battu en retraite pendant dix jours, couchant sur le sol, épuisés de fatigue, puissent être capables de reprendre le fusil et d’attaquer quand sonnent les clairons, c’est une chose que nous n’avions jamais envisagée, une éventualité que l’on n’étudiait pas dans nos écoles de guerre. » Le Kronprinz, dans une déclaration aussi prémonitoire que pathétique, s’inquiète : « A la bataille de la Marne, s’accomplit le tragique destin de notre peuple ». Maurice Barrès lui répond : « C’est l’éternel miracle français, le miracle de Jeanne d’Arc… » Le 11 septembre, il est clair que les Français ont gagné la bataille de la Marne. Le « coup de faux » prévu par les Allemands a échoué, et avec lui la guerre-éclair qui devait libérer le front Ouest. La course à la mer qui la suit finit de figer les positions. Non, aucun soldat ne sera de retour dans ses foyers pour Noël : il y aura bien d’autres Noël de boue et de sang… « Avec mon harnais sur le dos, avec toutes ces annexes de cuir et de fer, j’étais couché dans la terre. J’étais étonné d’être ainsi cloué au sol ; je pensais que ça ne durerait pas. Mais ça dura quatre ans. La guerre aujourd’hui, c’est d’être couché, vautré aplati. Autrefois, la guerre c’étaient des hommes debout. La guerre d’aujourd’hui, ce sont toutes les postures de la honte » (Drieu la Rochelle).

Le plan allemand, initié par le feld-maréchal comte von Schlieffen, prévoit de tourner les forces défensives françaises par la Belgique puis de fondre sur Paris. Il est en effet indispensable de remporter rapidement la victoire sur le front occidental pour pouvoir se retourner ensuite contre les Russes. En quelques semaines, les six armées allemandes bousculent les forces françaises sur plusieurs centaines de kilomètres. La route de Paris semble ouverte. Mais lors d’un sursaut extraordinaire, les Français s’arc-boutent sur la Marne et stoppent les Allemands, arrachant au général von Moltke cet aveu : « Que des hommes, après avoir battu en retraite pendant dix jours, couchant sur le sol, épuisés de fatigue, puissent être capables de reprendre le fusil et d’attaquer quand sonnent les clairons, c’est une chose que nous n’avions jamais envisagée, une éventualité que l’on n’étudiait pas dans nos écoles de guerre. » Le Kronprinz, dans une déclaration aussi prémonitoire que pathétique, s’inquiète : « A la bataille de la Marne, s’accomplit le tragique destin de notre peuple ». Maurice Barrès lui répond : « C’est l’éternel miracle français, le miracle de Jeanne d’Arc… » Le 11 septembre, il est clair que les Français ont gagné la bataille de la Marne. Le « coup de faux » prévu par les Allemands a échoué, et avec lui la guerre-éclair qui devait libérer le front Ouest. La course à la mer qui la suit finit de figer les positions. Non, aucun soldat ne sera de retour dans ses foyers pour Noël : il y aura bien d’autres Noël de boue et de sang… « Avec mon harnais sur le dos, avec toutes ces annexes de cuir et de fer, j’étais couché dans la terre. J’étais étonné d’être ainsi cloué au sol ; je pensais que ça ne durerait pas. Mais ça dura quatre ans. La guerre aujourd’hui, c’est d’être couché, vautré aplati. Autrefois, la guerre c’étaient des hommes debout. La guerre d’aujourd’hui, ce sont toutes les postures de la honte » (Drieu la Rochelle).

Les bilans commencent à être vertigineux : lors de la bataille d’Ypres, du 13 au 25 octobre, tombent 100 000 Français et Anglais et 130 000 Allemands ! Au 31 décembre 1914, sur le seul front occidental, Français, Anglais et Belges ont déjà perdu un million d’hommes, et les Allemands 700 000. « Le matin est gris ; lorsque nous sommes partis, c’était encore l’été et nous étions cent cinquante hommes. Maintenant nous avons froid ; c’est l’automne ; les feuilles bruissent, les voix s’élèvent d’un ton las : « Un, deux, trois quatre… » Et après le numéro trente-deux, elles se taisent. Il se produit un long silence, avant qu’une voix demande : « Y a-t-il encore quelqu’un ? » Puis elle attend et dit tout bas : « Par pelotons ! » Cependant elle s’arrête et ne peut achever que péniblement : « Deuxième compagnie… deuxième compagnie, pas de route, en avant ! » Une file, une brève file tâtonne dans le matin. Trente-deux hommes » (Remarque).

« LAISSEZ ICI TOUTE ESPERANCE » (Ernst Jünger)

Les tranchées: « Ils sont sales les boyaux, pleins de tous ces débris abominables que la guerre accumule aussitôt qu’elle est là : boîtes de conserve, bras, fusils, sacs, caisses, jambes, merdes, culots d’obus, grenades, chiffons et même des papiers » (Drieu la Rochelle). « Cet asile s’enfonce, ténébreux, suintant et étroit comme un puits. Toute une moitié en est inondée – on y voit surnager des rats – et les hommes sont massés dans l’autre moitié. […] S’asseoir ? Impossible. C’est trop sale, là-dedans : la terre et les pavés sont enduits de boue, et la paille disposée pour le couchage est tout humide à cause de l’eau qui s’y infiltre et des pieds qui s’y décrottent. De plus, si l’on s’assoit, on gèle, et si on s’étend sur la paille, on est incommodé par l’odeur du fumier et égorgé par les émanations ammoniacales » (Barbusse).

Le froid : « Quand on sort du gourbi, le froid vous mordille le menton, vous pique le nez comme une prise, il vous amuse. Puis il devient mauvais, vous grignote les oreilles, vous torture le bout des doigts, s’infiltre par les manches, par le col, par la chair, et c’est de la glace qui vous gèle jusqu’au ventre » (Dorgelès). Et la pluie : « C’est un dur effort, lorsqu’on sait, comme nous, l’accroissement que la pluie apporte avec elle : les vêtements lourds ; le froid qui pénètre avec l’eau ; le cuir des chaussures durci ; les pantalons qui plaquent contre les jambes et entravent la marche ; le linge, au fond du sac, le précieux linge propre qui délasse dès qu’on l’a sur la peau, irrémédiablement sali, transformé peu à peu en un paquet innommable sur lequel des papiers, des boîtes de conserve ont bavé leur teinture ; la boue qui jaillit, souillant le visage et les mains ; l’arrivée barbotante ; la nuit d’insuffisant repos, sous la capote qui transpire et glace au lieu de réchauffer ; tout le corps raidi, les articulations sans souplesse, douloureuses ; et le départ, avec les chaussures de bois qui meurtrissent les pieds comme des brodequins de torture » (Maurice Genevoix, Ceux de 14).

Les mouches et les poux : « On traverse des multitudes de mouches qui, accumulées sur les murs par couches noires, s’éploient en nappes bruissantes lorsqu’on passe. - Ca va recommencer comme l’année dernière !... Les mouches à l’extérieur, les poux à l’intérieur » (Barbusse). Les rats et les corbeaux : « Les rats venaient les renifler. Ils sautaient d’un mort à l’autre. Ils choisissaient d’abord les jeunes sans barbe sur les joues. Ils reniflaient la joue, puis ils se mettaient en boule et ils commençaient à manger cette chair d’entre le nez et la bouche, puis le bord des lèvres, puis la pomme verte de la joue. De temps en temps ils se passaient la patte dans les moustaches pour se faire propres. Pour les yeux, ils les sortaient à petits coups de griffes, et ils léchaient le trou des paupières, puis ils mordaient dans l’œil, comme dans un petit œuf, et ils le mâchaient doucement, la bouche de côté en humant le jus. […] Le corbeau poussait le casque ; parfois, quand le mort était mal placé et qu’il mordait la terre à pleine bouche, le corbeau tirait sur les cheveux et sur la barbe tant qu’il n’avait pas mis à l’air cette partie du cou où est le partage de la barbe et du poil de la poitrine. C’était là tendre et tout frais, le sang rouge y faisait encore la petite boule. Ils se mettaient à becqueter là, tout de suite, à arracher cette peau, puis ils mangeaient gravement en criant de temps en temps pour appeler les femelles » (Jean Giono, Le grand Troupeau).

La misère : « Plus que les charges qui ressemblent à des revues, plus que les batailles visibles déployées comme des oriflammes, plus même que le corps à corps où l’on se démène en criant, cette guerre, c’est la fatigue épouvantable, surnaturelle, et l’eau jusqu’au ventre, et la boue et l’ordure et l’infâme saleté. C’est les faces moisies et les chairs en loques et les cadavres qui ne ressemblent même plus à des cadavres, surnageant sur la terre vorace. C’est cela, cette monotonie infinie de misères, interrompue par des drames aigus, c’est cela, et non pas la baïonnette qui étincelle comme de l’argent, ni le chant de coq du clairon au soleil ! » (Barbusse). La peur : « Cet homme avait eu peur. Comme il avait eu peur. Comme j’avais eu peur, moi aussi. Comme nous avions eu peur. Quelle peur énorme, gigantesque, s’était accroupie et tordue sur ces faibles collines. Quelle immense femelle, possédée d’un aveu cynique, obscène, hystérique, délirant, s’était formée, au revers de Thiaumont, au creux de Fleury, de toutes nos peurs d’hommes accroupis, prosternés, vautrés, incrustés dans la terre gelée, fermentant dans nos sueurs, nos fanges, nos saignements. Comme cette femelle avait gémi et hurlé ! » (Drieu la Rochelle).

L’enfer : « Nos jambes se dérobent ; nos mains tremblent ; notre corps n’est plus qu’une peau mince recouvrant un délire maîtrisé avec peine et masquant un hurlement sans fin qu’on ne peut retenir. Nous n’avons plus ni chair, ni muscles ; nous n’osons plus nous regarder, par crainte de quelque chose d’incalculable. Ainsi nous serrons les lèvres, tâchant de penser : cela passera… Cela passera… Peut-être nous tirerons-nous d’affaire » (Remarque). Le déluge de fer : « C’était un déchaînement inattendu, épouvantable. L’homme au moment d’inventer les premières machines avait vendu son âme au diable et maintenant le diable le faisait payer. Je regarde, je n’ai rien à faire. Cela se passe entre deux usines, ces deux artilleries. L’infanterie, pauvre humanité mourante, entre l’industrie, le commerce, la science. Les hommes qui ne savent plus créer des statues, des opéras, ne sont bons qu’à découper du fer en petits morceaux. Ils se jettent des orages et des tremblements de terre à la tête, mais ils ne deviennent pas des dieux. Et ils ne sont plus des hommes » (Drieu la Rochelle). L’obus : « La terre s’est ouverte devant moi. Je me sens soulevé et jeté de côté, plié, étouffé et aveuglé à demi dans cet éclair de tonnerre… Je me souviens bien pourtant : pendant cette seconde où, instinctivement, je cherchais, éperdu, hagard, mon frère d’armes, j’ai vu son corps monter, debout, noir, les deux bras étendus de toute leur envergure, et une flamme à la place de la tête ! » (Barbusse). Les gaz : « Une attaque de gaz, qui vient par surprise, en emporte une multitude. Ils ne se sont même pas rendu compte de ce qui les attendait. Nous trouvons un abri rempli de têtes bleuies et de lèvres noires. Dans un entonnoir, ils ont enlevé trop tôt leurs masques. Ils ne savaient pas que dans les fonds le gaz reste plus longtemps ; lorsqu’ils ont vu que d’autres soldats au-dessus d’eux étaient sans masque, ils ont enlevé les leurs et avalé encore assez de gaz pour se brûler les poumons. Leur état est désespéré ; des crachements de sang qui les étranglent et des crises d’étouffement les vouent irrémédiablement à la mort » (Remarque). Les emmurés vivants : « L’univers éclata. L’obus arriva et je sus qu’il arrivait. Enorme, gros comme l’univers. Il remplit exactement un univers fini. C’était la convulsion même de cet univers. […] Et la porte s’était effondrée et la chambre était devenue un sépulcre vivant. Tous les hommes assis en rond s’étaient dressés à mon cri, car j’avais hurlé. Un cri, un aveu épouvantable m’avait été arraché qui les épouvanta, dit-on, plus que l’obus. Les hommes se ruèrent vers le point où avait été la porte et où maintenant se dressait un mur noir. Ils me passèrent sur le corps, ils me piétinèrent sauvagement. Me piétiner les consolait d’être emmurés. Nous étions emmurés » (Drieu la Rochelle).

L’attaque : « La compagnie entière était entassée là, grand bouclier vivant de casques rapprochés, devant quatre échelles grossières. La couverture roulée, pas de sac, l’outil au côté : « Tenue de gala », avait blagué Gilbert. A notre droite, empilée dans la même parallèle, une compagnie d’un régiment de jeunes classes venait de mettre baïonnette au canon. Toutes les sapes, toutes les tranchées étaient pleines, et de se sentir ainsi pressés, reins à reins, par centaines, par milliers, on éprouvait une confiance brutale. Hardi ou résigné, on n’était plus qu’un grain dans cette masse humaine. L’armée, ce matin-là, avait une âme de victoire » (Dorgelès). Les corps à corps : « Ce fut un massacre à l’arme blanche, la dégoûtante besogne d’assassins qui surinent dans le dos » (Genevoix). La relève : « Pauvres semblables, pauvres inconnus, c’est votre tour de donner ! Une autre fois, ce sera le nôtre. A nous demain, peut-être, de sentir les cieux éclater sur nos têtes s’ouvrir sous nos pieds, d’être assaillis par l’armée prodigieuse des projectiles, et d’être balayés par des souffles d’ouragan cent mille fois plus forts que l’ouragan » (Barbusse).

Le fer et le feu broient les pauvres chairs des hommes : « Nous voyons des gens à qui le crâne a été enlevé, continuer de vivre ; nous voyons courir des soldats dont les pieds ont été fauchés ; sur leurs moignons éclatés, ils se traînent en trébuchant jusqu’au prochain trou d’obus ; un soldat de première classe rampe sur ses mains pendant deux kilomètres en traînant derrière lui ses genoux brisés ; un autre se rend au poste de secours, tandis que ses entrailles coulent par-dessus ses mains qui les retiennent ; nous voyons des gens sans bouche, sans mâchoire inférieure, sans figure ; nous rencontrons quelqu’un qui, pendant deux heures, tient serrée avec les dents l’artère de son bras, pour ne point perdre tout son sang ; le soleil se lève, les obus sifflent ; la vie s’arrête» (Remarque). « La douleur l’avait engourdi et il ne sentait plus ses membres ni sa tête, il ne sentait que sa blessure, la plaie profonde qui lui fouillait le ventre. […] Il n’avait pas encore osé toucher sa blessure, cela lui faisait peur, et sa main s’écartait de son ventre, pour ne pas sentir, pour ne pas savoir. […] Enfin, il se dompta et, la bande prête, résolument il toucha la plaie. C’était au-dessus de l’aine gauche. Sa capote était déchirée et, sous ses doigts craintifs, il ne sentait rien qu’une chose gluante. Lentement, pour ne pas souffrir, il déboucla son ceinturon, ouvrit sa capote et son pantalon, puis il essaya de soulever sa chemise. Ce fut horrible, il lui sembla qu’il allait s’arracher les entrailles, emporter sa chair… Torturé, il s’arrêta, sa main posée sur sa peau nue. Il sentit quelque chose de tiède qui, doucement, lui coulait le long des doigts. […] La pluie ruisselait en pleurs le long de ses joues amaigries. Puis deux lourdes larmes coulèrent de ses yeux creux : les deux dernières » (Giono). « Chauvin était renversé sur le dos au fond du trou, cassé, plié sur son ventre ; il regardait ce morceau de ciel bleu. Ses yeux étaient comme de la pierre. Il pataugeait à deux mains dans son ventre ouvert, comme dans un mortier. Ses poings faisaient le moulin ; ses tripes attachaient ses poignets. Il s’arrêta de crier. Il était tout empêtré dans ses tripes, et en raidissant ses bras, il les tira comme ça en dehors de son ventre » (Dorgelès). « Un petit convoi approchait. Il y avait cinq ou six hommes autour d’un brancard que deux hommes portaient sur leurs épaules. Un affreux gémissement vint au-dessus de moi, se jeta sur moi. Les hommes avaient un air épouvanté. Comme j’arrivais près d’eux, ils s’arrêtèrent et déposèrent le brancard. Ce fut l’occasion d’un affreux long hurlement – puis une série de cris, de gémissements, de protestations, de supplications. […] Je m’approchai avec crainte. Alors je le vis… Je n’avais pas vu ça depuis deux ans. Et c’était dans la plus horrible manière de cette sacrée nature. Un beau jeune homme, un grand corps, un officier, ce bras avec ce bracelet d’or. Et un visage arraché. Arraché. Une bouillie. Il n’avait plus d’yeux, plus de nez, plus de bouche. Et il était vivant, bien vivant ; sans doute vivrait-il. […] Et lui, il tournait sa face de tous côtés, avec son habitude de voir. Il y avait là quelque part dans cette surface énorme, dans ce chaos de viandes, une double habitude de voir qui nous cherchait » (Drieu la Rochelle).

Même les morts ne connaissent aucune délivrance : « En touchant du pied ce fond mou, un dégoût surhumain me rejeta en arrière, épouvanté. C’était un entassement infâme, une exhumation monstrueuse de Bavarois cireux sur d’autres déjà noirs, dont les bouches tordues exhalaient une haleine pourrie ; tout un amas de chairs déchiquetées, avec des cadavres qu’on eût dits dévissés, les pieds et les genoux complètement retournés, et pour les veiller tous, un seul mort resté debout, adossé à la paroi, étayé par un monstre sans tête. Le premier de notre file n’osait pas avancer sur ce charnier : on éprouvait comme une crainte religieuse à marcher sur ces cadavres, à écraser du pied ces figures d’hommes » (Dorgelès). « Les morts bougeaient. Les nerfs se tendaient dans la raideur des chairs pourries et un bras se levait lentement dans l’aube. Il restait là, dressant vers le ciel sa main noire toute épanouie ; les ventres trop gonflés éclataient et l’homme se tordait dans la terre, tremblant de toutes ses ficelles relâchées. Il reprenait une parcelle de vie. Il ondulait des épaules, comme dans sa marche d’avant. […] Et les rats s’en allaient de lui. Mais, ça n’était plus son esprit qui faisait onduler ses épaules, seulement la mécanique de la mort, et au bout d’un peu, il retombait immobile dans la boue. Alors les rats revenaient » (Giono). « Il en est qui montrent des faces demi-moisies, la peau rouillée, jaune avec des points noirs. Plusieurs ont la figure complètement noircie, goudronnée, les lèvres tuméfiées et énormes : des têtes de nègres soufflées en baudruche. […] Plus loin, on a transporté un cadavre dans un état tel qu’on a dû, pour ne pas le perdre en chemin, l’entasser dans un grillage de fil de fer qu’on a fixé ensuite aux extrémités d’un pieu. Il a été ainsi porté en boule dans ce hamac métallique, et déposé là. On ne distingue ni le haut, ni le bas de ce corps ; dans le tas qu’il forme, seule se reconnaît la poche béante d’un pantalon. On voit un insecte qui en sort et y rentre. […] L’homme est sur le ventre ; il a les reins fendus d’une hanche à l’autre par un profond sillon ; sa tête est à demi retournée ; on voit l’œil creux et sur la tempe, la joue et le cou, une sorte de mousse verte a poussé. […] A côté des têtes noires et cireuses de momies égyptiennes, grumeleuses de larves et de débris d’insectes, où des blancheurs de dents pointent dans des creux ; à côté de pauvres moignons assombris qui pullulent là, comme un champ de racines dénudées, on découvre des crânes nettoyés, jaunes, coiffés de chéchias de drap rouge dont la housse grise s’effrite comme du papyrus. […] Je cherche les traits de l’un d’eux : depuis les profondeurs de son cou jusqu’aux touffes de cheveux collés au bord de son calot, il présente une masse terreuse, la figure changée en fourmilière – et deux fruits pourris à la place des yeux. L’autre, vide, sec, est aplati sur le ventre, le dos en loques quasi flottant, les mains, les pieds et la face enracinés dans le sol. […] Un feldwebel est assis, appuyé aux planches déchirées qui formaient, là où nous mettons le pied, une sorte de guérite de guetteur. Un petit trou sous l’œil : un coup de baïonnette l’a cloué aux planches par la figure. Devant lui, assis aussi, les coudes sur les genoux, les poings au cou, un homme a tout le dessus du crâne enlevé comme un œuf à la coque… A côté d’eux, veilleur épouvantable, la moitié d’un homme est debout : un homme, coupé, tranché en deux depuis le crâne jusqu’au bassin, est appuyé, droit, sur la paroi de terre. On ne sait pas où est l’autre moitié de cette sorte de piquet humain dont l’œil pend en haut, dont les entrailles bleuâtres tournent en spirale autour de la jambe » (Barbusse).

Les animaux n’échappent pas à cette folie : « Les cris continuent. Ce ne sont pas des êtres humains qui peuvent crier si terriblement. Je n’ai encore jamais entendu crier des chevaux et je puis à peine le croire. C’est toute la détresse du monde. C’est la créature martyrisée, c’est une douleur sauvage et terrible qui gémit ainsi… Quelques uns continuent de galoper, s’abattent et reprennent leur course. L’un d’eux a le ventre ouvert ; ses entrailles pendent tout du long. Il s’y entrave et tombe, mais pour se relever encore… On peut dire que nous sommes tous capables de supporter beaucoup ; mais en ce moment, la sueur nous inonde. On voudrait se lever et s’en aller n’importe où pourvu qu’on n’entende plus ces plaintes. Et pourtant ce ne sont pas des êtres humains, ce ne sont que des chevaux » (Remarque).

Le chagrin et la pitié : « Quand Wedelstädt vit tomber cet homme, le dernier de sa compagnie, il s’appuya la tête au rebord de la tranchée et se mit à pleurer. Lui non plus ne devait pas survivre à ce jour » (Jünger). « Autour de lui, avec ses yeux vitreux qui semblaient se refuser à la vision précise des choses, il avait vu ses trois mille camarades du départ disparaître par masses ou paquets, jusqu’au dernier, et les avait vu remplacer par d’autres dont la plupart n’avaient fait aussi que passer, en route pour l’hôpital ou la mort, puisque quinze mille hommes avaient roulé à travers nos trois mille numéros matricules » (Drieu la Rochelle). « Et jusqu’à la nuit, je fume, je fume, pour vaincre l’odeur épouvantable, l’odeur des pauvres morts perdus par les champs, abandonnés par les leurs, qui n’ont même pas eu le temps de jeter sur eux quelques mottes de terre, pour qu’on ne les vît pas pourrir » (Genevoix). « Il allait encore pleuvoir ; le jour était d’une blancheur livide qui aveuglait. A terre, des lambeaux de pluie traînaient en flaques jaunâtres que le vent fripait, et quelques gouttes espacées y faisaient des ronds. La pluie n’espérait pourtant pas laver cette boue, laver ces haillons, laver ces cadavres ? Il pourrait bien pleuvoir toutes les larmes du ciel, pleuvoir tout un déluge, cela n’effacerait rien. Non, un siècle de pluie n’effacerait pas ça » (Dorgelès). « En même temps que le jour, montait au-delà du désert le roulement sourd d’un grand charroi. C’étaient ces fleuves d’hommes, de chars, de canons, de camions, de charrettes qui clapotaient là-bas dans le creux des coteaux ; les grands chargements de viande, la nourriture de la terre » (Giono). « On oubliera. Les voiles de deuil, comme des feuilles mortes, tomberont. L’image du soldat disparu s’effacera lentement dans le cœur consolé de ceux qu’ils aimaient tant. Et tous les morts mourront une seconde fois. Non, votre martyre n’est pas fini, mes camarades, et le fer vous blessera encore, quand la bêche du paysan fouillera votre tombe. […] Je songe à vos milliers de croix de bois, alignées tout le long des grandes routes poudreuses, où elles semblaient guetter la relève des vivants, qui ne viendra jamais faire lever les morts […] Combien sont encore debout, des croix que j’ai plantées ? Mes morts, mes pauvres morts, c’est maintenant que vous allez souffrir, sans croix pour vous garder, sans cœur pour vous blottir. Je crois vous voir rôder, avec des gestes qui tâtonnent, et chercher dans la nuit éternelle tous ces vivants ingrats qui déjà vous oublient » (Dorgelès).

Des ennemis ? non, des frères : « Les occupants des tranchées des deux partis avaient été chassés par la boue sur leurs parapets, et il s’était déjà amorcé, entre les réseaux de barbelés, des échanges animés, tout un troc d’eau-de-vie, de cigarettes, de boutons d’uniforme et d’autres objets. […] Nous commençâmes à parlementer en anglais, puis, un peu plus couramment, en français, tandis que les hommes de troupe alentour prêtaient l’oreille. […] Mais nous bavardâmes longtemps encore sur un ton où s’exprimait une estime quasi sportive, et pour finir, nous aurions volontiers échangé des cadeaux en souvenir. Pour en revenir à une situation sans équivoque, nous nous déclarâmes solennellement la guerre sous trois minutes à compter de la rupture des négociations » (Jünger). « A la jumelle, je vois sur un chemin deux blessés qui se traînent, deux Français. Un des uhlans les a aperçus. Il a mis pied à terre, s’avance vers eux. Je suis la scène de toute mon attention. Le voici qui les aborde, qui leur parle ; et tous les trois se mettent en marche vers un gros buisson voisin de la route, l’Allemand entre les deux Français, les soutenant, les exhortant sans doute de la voix. Et là, précautionneusement, le grand cavalier gris aide les nôtres à s’étendre. Il est courbé vers eux, il ne se relève pas. Je suis sûr qu’il les panse » (Genevoix).

L’HOLOCAUSTE EUROPEEN

Au début de la guerre, les états-majors des deux camps n’ont aucune considération pour la vie de leurs hommes, comme Joffre : « A ce jeu, il était certain que nous nous userions ; mais l’ennemi s’userait aussi, et toute la question était de mener nos affaires avec sagesse pour pouvoir durer plus que lui. A la guerre, ce sont les derniers bataillons qui emportent la victoire. » Autrement dit, s’il ne doit rester qu’un survivant, il suffira qu’il soit français… Nos généraux ne connaissent que l’attaque à tout prix, qui voit les Poilus à pantalon garance se faire hacher par les mitrailleuses allemandes soigneusement enterrées : 40 000 tués fin août pendant l’offensive française en Lorraine. Nivelle se révèlera un élève zélé de Joffre. Une seule stratégie : le « grignotage », ou comment gagner quelques centaines de mètres (vite reperdus) au prix de centaines de morts et parfois de centaines de milliers de morts ! « Là, sur notre sol, dans un pays évolué, de vieille civilisation, a eu lieu l’un des massacres les plus abominables de l’histoire de l’humanité. Et nous avons accepté de rentrer dans cette barbarie » (Marc Dugain). Il faudra que des régiments se mutinent, non par peur, défaitisme ou pacifisme, mais simplement parce qu’il était devenu insupportable de continuer ces boucheries inutiles. Le général Pétain mettra fin à celles-ci et ramènera l’ordre et le calme dans les unités au prix de 49 exécutions.

Pétain, c’est l’homme de Verdun. Verdun, c’est non seulement une bataille, mais c’est un sanctuaire : « Tous vinrent à Verdun comme pour recevoir je ne sais quelle suprême consécration. Ils semblaient par la Voie Sacrée monter pour un offertoire sans exemple à l’autel le plus redoutable que jamais l’homme eût levé » (Paul Valéry). Il faut savoir que 66 des 95 divisions françaises se battirent à tour de rôle à Verdun, pour tenir, tenir coûte que coûte. Les deux tiers des soldats français y ont peu ou prou combattu. Le chef d’état-major allemand, le général Falkenhayn, avait voulu Verdun pour « saigner la France à blanc ! » Erreur funeste, les deux peuples s’avérèrent incapables de se départager, 21 millions d’obus déversés par les Français, 22 par les Allemands. Même dans le décompte des morts : 163 000 Gaulois et 143 000 Germains ! Au total, près d’un million de morts et de blessés ! « Plus d’arbres, plus de maisons, plus d’animaux à cinq lieues à la ronde. Des divisions détruites avant d’arriver en première ligne. […] Or, il y avait déjà pour les siècles dans ce paysage de Verdun une mélancolie irrésistible. Ces vues immenses, ces échappées sans fin entre des masses immobiles et résistantes, et vers la droite au-delà de la Meuse, cette immense fuite d’horizon. Et autour de nous, plus près, ces pentes émaciées, ces hérissements à ras de terre de souches noires, ce million de cadavres sous nos pieds, ce cinquième hiver qui commençait, ce délire soudain qui m’avait ramené à ces lieux que j’avais fuis à jamais, ce délire qui semblait la fatalité masquée – tout cela poussait un grand cri » (Drieu la Rochelle). Henry de Montherlant écrira plus tard : « Les hommes de Verdun s’étaient rassemblés sur cette étroite bande de sol pour y verser comme de l’eau, le plus pur de leur vie, puis leur vie ; ils avaient fait d’elle une matière sensible, imbibée d’âme comme certain marbre l’est de lumière, plus vivante avec sa croûte de morts qu’aucun des lieux où la vie pullule. »

Chaque peuple eut droit à son sanctuaire. Pour les Allemands, ce fut Langemarck, où combattirent Jünger et Hitler. Le bulletin de l’armée du 11 novembre 1914 est ainsi rédigé : « Les régiments de jeunes ont donné l’assaut à l’ouest de Langemarck contre les premières lignes ennemies et les ont vaincues en chantant « Deutschland, Deutschland über alles ! » Il fallait sublimer cet événement : 145 000 jeunes Teutons y tombèrent pour que le mythe puisse exister : « Il n’y a de bonheur que dans la guerre sacrificielle » (Theodor Körner). Pour les Anglais, ce fut la Somme où, le 1er juillet 1916, en quelques heures, 60 000 hommes sur 100 000 furent mis hors de combat par les Allemands solidement retranchés. En quelques jours, les pertes, morts et blessés confondus, y furent de 420 000 Anglais, 200 000 Français et 440 000 Allemands. Pour quelques centaines de mètres pris à l’ennemi !

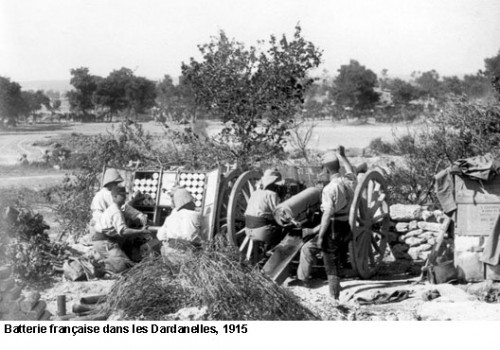

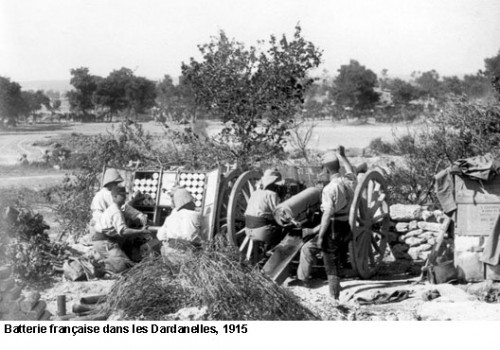

Auparavant, il y avait eu l’aventure des Dardanelles (1915) et le désastre de Gallipoli : 145 000 Français et 225 000 Anglo-Saxons liquidés. Le coût de l’offensive française en Champagne et en Artois (1914-1915) est de 600 000 morts ; pour rien ou si peu : la seconde des trois batailles de Vimy a permis de « grignoter » 2,5 km aux Allemands au prix de 95 000 morts ! Autrichiens et Italiens laissent 300 000 soldats lors des douze batailles de l’Isonzo, dont l’unique objet était de prendre le contrôle du port de Trieste. L’inutile boucherie du Chemin des Dames couche 200 000 morts de part et d’autre. Et combien d’autres terres de souffrance disséminées aux quatre coins de l’Europe, car le front oriental et le front méridional (Balkans) affichent des bilans tout aussi effroyables : les Serbes perdent ainsi 200 000 des leurs dans les montagnes enneigées d’Albanie… « Je fis avancer les chefs de groupes au rapport et appris que nous comptions encore soixante-trois hommes. C’est avec plus de cent cinquante que j’étais parti la veille au soir, plein d’entrain » (Jünger).

Auparavant, il y avait eu l’aventure des Dardanelles (1915) et le désastre de Gallipoli : 145 000 Français et 225 000 Anglo-Saxons liquidés. Le coût de l’offensive française en Champagne et en Artois (1914-1915) est de 600 000 morts ; pour rien ou si peu : la seconde des trois batailles de Vimy a permis de « grignoter » 2,5 km aux Allemands au prix de 95 000 morts ! Autrichiens et Italiens laissent 300 000 soldats lors des douze batailles de l’Isonzo, dont l’unique objet était de prendre le contrôle du port de Trieste. L’inutile boucherie du Chemin des Dames couche 200 000 morts de part et d’autre. Et combien d’autres terres de souffrance disséminées aux quatre coins de l’Europe, car le front oriental et le front méridional (Balkans) affichent des bilans tout aussi effroyables : les Serbes perdent ainsi 200 000 des leurs dans les montagnes enneigées d’Albanie… « Je fis avancer les chefs de groupes au rapport et appris que nous comptions encore soixante-trois hommes. C’est avec plus de cent cinquante que j’étais parti la veille au soir, plein d’entrain » (Jünger).

La Première Guerre mondiale a causé la mort de 9 millions d’hommes ; les blessés, mutilés, invalides représentent à peu près le double. « … Non, on ne peut pas se figurer. Toutes ces disparitions à la fois excèdent l’esprit. Il n’y a plus assez de survivants. Mais on a une vague notion de la grandeur de ces morts. Ils ont tout donné ; ils ont donné, petit à petit, toute leur force, puis, finalement, ils se sont donnés, en bloc. Ils ont dépassé la vie : leur effort a quelque chose de surhumain et de parfait » (Barbusse). De tous les belligérants exténués, la France est la plus touchée : 1,5 million de morts (15% des soldats, 22% des officiers), 3,5 millions de blessés dont 900 000 mutilés et invalides. Oui, la France a bien été saignée à blanc. Le quart nord-est du pays est ravagé : 2,4 millions d’hectares sont devenus impropres aux cultures, 9 300 usines sont détruites. La Grande Faux se montrera vraiment insatiable, puisque la grippe espagnole tuera encore 20 millions de personnes en Europe en quelques mois.

UNE NOUVELLE RACE D’HOMMES

« Je crois que cette guerre est un défi lancé à l’époque et à chaque individu. L’épreuve du feu va nous obliger à mûrir, à devenir des hommes, des hommes capables d’affronter les événements prodigieux des années à venir » (Otto Braun, engagé volontaire en 1914). Cette guerre fut en effet une « rude école » : « Le front attire invinciblement parce qu’il est, pour une part, l’extrême limite de ce qui se sent et se fait. Non seulement on y voit autour de soi des choses qui ne s’expérimentent nulle part ailleurs, mais on y voit affleurer en soi un fond de lucidité, d’énergie, de liberté, qui ne se manifeste guère ailleurs dans la vie commune» (Teilhard de Chardin).

Une nouvelle race d’hommes est ainsi née dans l’enfer des tranchées et a pour origine la camaraderie des combattants. Ernst Jünger lui a consacré un ouvrage, La Guerre comme aventure intérieure. Remarque a également décrit ce phénomène : « Nous devînmes durs, méfiants, impitoyables, vindicatifs, brutes et ce fut une bonne chose. Nous ne fûmes pas brisés, bien au contraire, nous nous adaptâmes. Mais le plus important ce fut qu’un ferme sentiment de solidarité pratique s’éveilla en nous, lequel au front, donna naissance ensuite à ce que la guerre produisit de meilleur : la camaraderie. » Plus loin : « Brusquement une chaleur extraordinaire m’envahit. Ces voix, ces quelques paroles prononcées bas, ces pas dans la tranchée derrière moi m’arrachant tout d’un coup à l’atroce solitude de la crainte et de la mort à laquelle je me serais presque abandonné. Elles sont plus que ma vie, ces voix ; elles sont plus que la présence maternelle et que la crainte ; elles sont ce qu’il y a au monde de plus fort et de plus efficace pour vous protéger : ce sont les voix de mes camarades. »

Car ces hommes ont franchi des frontières qui sont devenues totalement incompréhensibles pour la majorité de nos contemporains : « Quand je demandai des volontaires, j’eus la surprise de voir – car nous étions tout de même à la fin de 1917 – se présenter dans presque toutes les compagnies du bataillon près des trois quarts de l’effectif » (Jünger). « Avec mes hommes, nous nous élancions le long de ce bois où la plupart d’entre nous seraient enterrés, dans ce bois devenu aujourd’hui, pour quelques années, un charmant cimetière » (Drieu la Rochelle). La mort, n’est plus pour eux, source d’effroi ; ils l’ont tellement côtoyée qu’ils l’ont apprivoisée : « La mort avait perdu ses épouvantes, la volonté de vivre s’était reportée sur un être plus grand que nous, et cela nous rendait tous aveugles et indifférents à notre sort personnel. […] Le no man’s land grouillait d’assaillants qui, soit isolément, soit par petits paquets, soit en masses compactes, marchaient vers le rideau embrasé. Ils ne couraient pas, ni ne se planquaient quand les immenses panaches s’élevaient au milieu d’eux. Pesamment, mais irrésistiblement, ils marchaient vers la ligne ennemie. Il semblait qu’ils eussent cessé d’être vulnérables. […] Quand nous avançâmes, une fureur guerrière s’empara de nous, comme si, de très loin, se déversait en nous la force de l’assaut. Elle arrivait avec tant de vigueur qu’un sentiment de bonheur, de sérénité me saisit » (Jünger). Cet élan et cette fureur sont également décrits par Drieu la Rochelle : « Nous nous regardâmes avec plaisir, avec confiance. Nous nous reconnaissions comme des braves, comme de ceux qui sont le sel d’une armée. Et chacun devenait encore plus brave en regardant l’autre. Et si nous regardions autour de nous, notre courage méprisait et menaçait toutes ces peurs qui s’aplatissaient sur le sol autour de nous. […] Nous criions. Qu’est-ce que nous criions ? Nous hurlions comme des bêtes. Nous étions des bêtes. Qui sautait et criait ? La bête qui est dans l’homme, la bête dont vit l’homme. La bête qui fait l’amour et la guerre et la révolution. »

Ces hommes se donnent des chefs, qu’ils choisissent en fonction de leurs qualités plutôt que de leurs galons : « Mais de même que je m’étais reconnu, ils se reconnaissaient en moi. Aussi étonnés que moi – non, tout de même plus étonnés que moi. Mais bientôt, ils couraient, comme s’ils n’avaient jamais été que cela, des nobles. La noblesse est à tout le monde. J’étais grand, j’étais immense sur ce champ de bataille. Mon ombre couvrait et couvre encore ce champ de bataille. Il y avait ainsi un héros tous les vingt kilomètres. Et c’est pourquoi la bataille ne mourait pas, mais rebondissait » (Drieu la Rochelle). Et quand les officiers tombent, il en est toujours pour prendre la relève : « Mais on ne voit plus le lieutenant. Plus de chefs, alors… Une hésitation retient la vague humaine qui bat le commencement du plateau. - En avant ! crie un soldat quelconque. Alors tous reprennent en avant, avec une hâte croissante, la course à l’abîme » (Barbusse).

Lorsque la fin de la guerre arrive, ils retournent dans un monde qui leur est devenu étranger. Ils ont connu l’amitié virile, découvert les satisfactions d’une communauté constructive et solidaire, développé un système de hautes valeurs, « la loi, la moralité, la vertu, la foi, la conscience » (Theodor Körner) et poussé le sens du devoir jusqu’au sacrifice suprême… Ils n’acceptent pas de vivre dans une société où les valeurs sont souvent inversées : intérêt, mesquinerie, mensonge, médiocrité, individualisme... Certains sombrent alors comme le capitaine Conan du roman éponyme de Roger Vercel : « Te rappelles-tu ce que je te disais à Gorna, qu’on était trois mille, au plus, à l’avoir gagnée, la guerre ?... Ces trois mille-là, t’en retrouveras peut-être parfois un ou deux, par-ci, par-là, dans un patelin ou un autre… Regarde-les bien, mon vieux Norbert : ils sont comme moi ! » Mais la plupart sont décidés justement à appliquer ce système de vertus propres à régénérer les individus et le pays : « C’était un idéal physique, esthétique et moral : force et courage s’allient aux proportions harmonieuses du corps et à la pureté de l’âme » (George L. Mosse, De la Grande Guerre au totalitarisme).

PLUS RIEN NE SERA JAMAIS COMME AVANT

« Et, des ruines de cette catastrophe qui accouchaient à la fois de la mondialisation américaine et des nihilismes socialistes (communisme et nazisme), l’Europe ne devait jamais se remettre » (Aymeric Chauprade). La Première Guerre mondiale est la matrice d’événements capitaux qui ont bouleversé l’Europe et même le monde. En premier lieu, les Allemands, après l’échec du plan Schlieffen, inversent le raisonnement. Pour affaiblir la Russie, ils lui inoculent le « bacille de la peste », en y acheminant Lénine jusqu’alors réfugié en Suisse. On connaît la suite : la victoire des bolcheviks, l’effondrement du front russe et la paix séparée de Brest-Litovsk. Plus tard, l’Allemagne en paiera le prix fort, qui sera quasiment détruite par l’URSS en 1944-1945, et dont la moitié sera occupée pendant 45 autres années. La moitié de l’Europe partagera l’addition pendant la même période.

Les survivants des tranchées, cette nouvelle race, ne peuvent que se lever contre la vermine rouge qui tente de conquérir le vieux monde et dont les valeurs sont aux antipodes de celles qu’ils exaltent : collectivisme, égalitarisme, étatisme. Cela commence par les Corps-Francs allemands du Baltikum et les Russes blancs de Dénikine, Koltchak et Wrangel. Mais les Alliés prennent peur d’un rétablissement de la Russie aristocratique et d’une éventuelle alliance entre celle-ci et une Allemagne revancharde. Ils leur préféreront les bolcheviks, avec les conséquences que l’on sait. Mais le fascisme – ou plutôt les fascismes, dont le nazisme - éclot dans tous les pays menacés par les communistes. Idéologie de « l’énergie vitale », il est avant tout une réaction contre la gangrène marxiste. Pour preuve, en Espagne, qui était restée à l’écart du premier conflit du siècle, le phalangisme et le franquisme se sont développés en réaction contre les Rouges du Frente Popular.

La Grande-Bretagne, réfugiée dans son île d’où elle croit diriger encore le monde, échappe à ce phénomène. La France également, mais pour d’autres raisons : si elle est sortie victorieuse du conflit, elle est aussi épuisée. Elle a trop souffert : les femmes qui, pendant des années, ont remplacé les hommes dans les champs comme dans les usines, y ont en quelque sorte pris le pouvoir : elles éduquent leurs enfants dans la haine de la guerre. Les Français se repaissent dans les délices médiocres du Front populaire et ne voient pas arriver la tragédie. Liquidée en quelques jours en juin 1940, la France ne se relèvera jamais de cette affreuse honte.

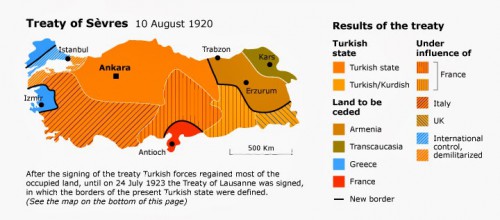

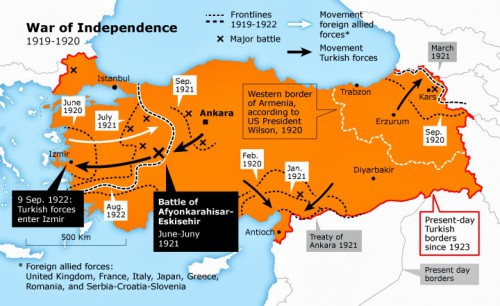

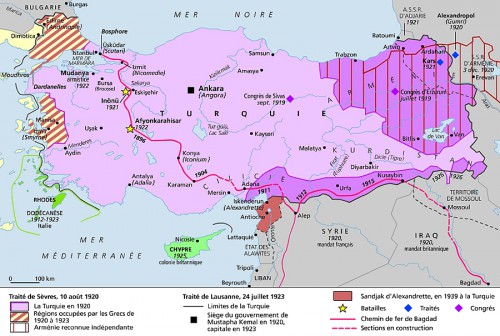

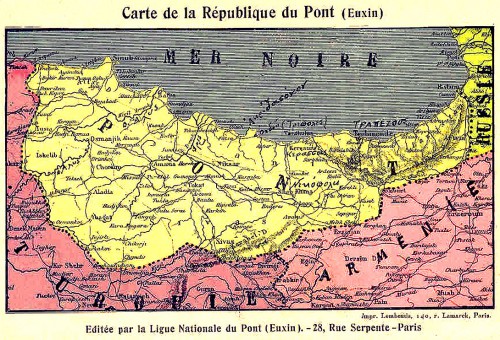

Il faut aussi parler des traités infâmes qui ont redessiné l’Europe : la culpabilisation des vaincus (« la victoire de la civilisation sur l’empire du Mal », déjà), l’humiliation de l’Allemagne, le démantèlement de l’Autriche-Hongrie, la création d’une multitude d’Etats ingérables, aux innombrables minorités, comme la Yougoslavie et la Tchécoslovaquie, qui ne suscitent que haine et frustration. C’est l’œuvre des démocrates Wilson, Lloyd George, Clemenceau… mus par une haine féroce à l’égard de l’ancien monde. Ce dernier n’a-t-il pas déclaré en préambule à Versailles : « L’heure de notre lourd règlement de comptes est venu » ? C’est tout dire. Ce sont eux qui ont labouré et ensemencé les champs de la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Ce ne sont pas des héros, ce sont les responsables de dizaines de millions de morts ! Ainsi, l’Europe sera une nouvelle fois emportée dans un conflit apocalyptique, dont le bilan sera de plus de 50 millions de victimes. Le fascisme, et avec lui le nazisme, disparaîtront dans les ruines de Berlin. Et avec eux, la vieille Europe, cette Europe qu’on avait crue éternelle. Il faudra attendre encore 45 ans pour que le communisme sombre également.

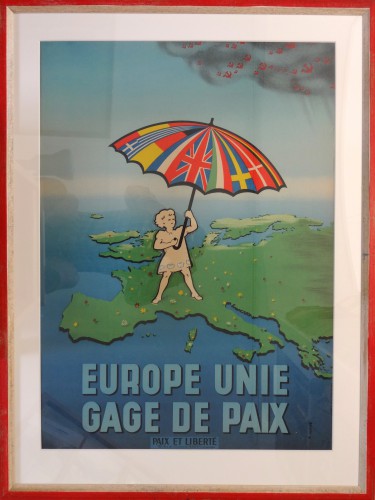

Maintenant que se sont évanouies les idéologies dites totalitaires, il faut remonter à la Première Guerre mondiale pour comprendre les clés de la situation actuelle. La Grande Guerre marque l’intrusion des Etats-Unis d’Amérique dans la politique européenne. Ce sont les Européens qui les ont appelés à l’aide. Lloyd George et Wilson exaltaient « l’amitié, les liens du sang, les mêmes idéaux et un destin commun » entre leurs deux pays. Mais cet allié providentiel, dont l’entrée en guerre, avec son inépuisable réservoir industriel et humain, est décisive, a l’étreinte du python : « Cet appel à l’arbitrage des Etats-Unis revient à confier le sort de l’Europe à la grande puissance qui s’était édifiée dans le rejet de sa tradition historique » (Dominique Venner). A travers ses « Quatorze Points », Wilson impose à l’Europe, au moins à l’état embryonnaire, l’universalisme, le libéralisme, la mondialisation, l’anti-colonialisme, la religion des droits de l’homme, thèmes hérités du Siècle des Lumières et revus par le messianisme protestant des Anglo-Saxons. En bref, un poison mortel pour l’Europe.

Pour achever ce réquisitoire, on rappellera les mots de Romain Rolland, alors trop âgé pour être mobilisé : « Cette jeunesse avide de se sacrifier, quel but avez-vous offert à son dévouement magnanime ? L’égorgement mutuel de ces jeunes héros ! La guerre européenne, cette mêlée sacrilège, qui offre le spectacle d’une Europe démente, montant sur le bûcher et se déchirant de ses mains comme Hercule ! Ainsi les trois plus grands peuples d’Occident, les gardiens de la civilisation, s’acharnent à leur ruine et appellent à la rescousse les Cosaques, les Turcs, les Japonais, les Cinghalais, les Soudanais, les Sénégalais, les Marocains, les Egyptiens, les Sikhs et les Cipayes. » Quelle lucidité ! Pourquoi les Européens ont-ils introduit dans leurs jeux guerriers les peuples qu’ils avaient soumis aux quatre coins de la planète ? Non seulement, c’était injuste : qu’avaient-ils à faire de nos querelles, et quel prix ont-ils dû payer ? Qui plus est, ce crime contre ces peuples qui n’avaient rien demandé marqua le début des mouvements de libération coloniale. Le retour de manivelle est si fort, qu’après une décolonisation lamentable, ce sont les peuples d’Europe qui agonisent sous le poids de leurs anciennes assujettis : immigration massive, métissage, islamisation. Le pire est à venir.

Erich Maria Remarque demandait des comptes aux responsables de cette horreur : « Que feront nos pères si, un jour, nous nous levons et nous nous présentons devant eux pour réclamer des comptes ? Qu’attendent-ils de nous lorsque viendra l’époque où la guerre sera finie ? Pendant des années nous avons été occupés à tuer ; ça a été là notre première profession des l’existence. Notre science de la vie se réduit à la mort. Qu’arrivera-t-il donc après cela ? Et que deviendrons-nous ? » Nous aussi, nous leur demandons des comptes, à eux et à leurs successeurs, qui n’ont rien compris et qui ne comprennent toujours rien, pour tous les malheurs qu’ont connus les peuples d’Europe depuis ce funeste début de XXème siècle, et tout ce qu’ils vont encore endurer au cours de ce XXIème siècle. Parlera-t-on encore de « peuples d’Europe » lorsque celui-ci se finira ?

Ne perdons cependant pas espoir : « Les jours, les semaines, les années de front ressusciteront à leur heure et nos camarades morts reviendront alors et marcheront avec nous. Nos têtes seront lucides, nous aurons un but et ainsi nous marcherons, avec, à côté de nous, nos camarades morts et, derrière nous, les années de front : nous marcherons… contre qui, contre qui ? » Ainsi s’exprimait Remarque. Il ne savait pas contre qui ; nous, depuis, nous avons appris.

Alain Cagnat

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

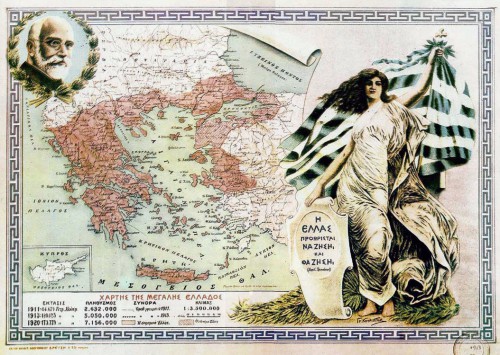

C'est sous son règne que le territoire national grec s'est agrandi: en 1864, il acquiertl es Iles Ioniennes avec Corfou; en 1881, il s'adjoint la Thessalie; en 1913, de vastes zones s'ajoutent au royaume au Nord et à l'Est. C'est là le résultat des guerres balkaniques, où le Prince Constantin, fort de sa formation militaire auprès de l'état-major général allemand, mène ses troupes à la victoire. Constantinople a vraiment été à portée de main…

C'est sous son règne que le territoire national grec s'est agrandi: en 1864, il acquiertl es Iles Ioniennes avec Corfou; en 1881, il s'adjoint la Thessalie; en 1913, de vastes zones s'ajoutent au royaume au Nord et à l'Est. C'est là le résultat des guerres balkaniques, où le Prince Constantin, fort de sa formation militaire auprès de l'état-major général allemand, mène ses troupes à la victoire. Constantinople a vraiment été à portée de main…

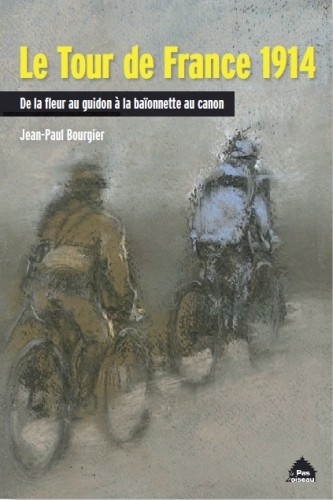

La Coupe du monde de football vient de se terminer; les amateurs de sports tournent leur regard, comme chaque mois de juillet, vers le Tour de France cycliste. La plus célèbre course de vélos du monde se déroule aujourd'hui à l'ombre de celle de 1914, cent ans après que la première guerre mondiale ait éclaté. Le départ d'une étape à Ypres, le passage du peloton le long du champ de bataille de Verdun, les longues étapes en Alsace et en Lorraine en sont la preuve. L'étape qui s'est déroulée sur les pavés du Nord a été, elle aussi, un hommage aux morts de la première guerre mondiale, parce que l'expression "l'enfer du Nord" est née en 1919, quand le parcours de la course Paris-Roubaix était particulièrement sinistre et difficile. Les voies "carrossables" avaient été labourées par les artilleries française, britannique et allemande.

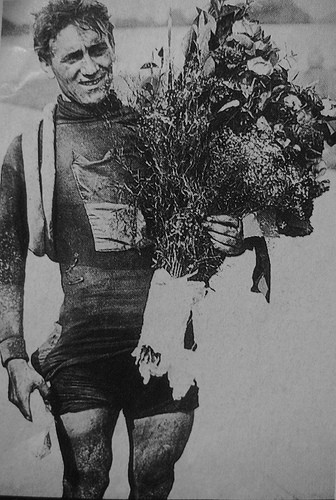

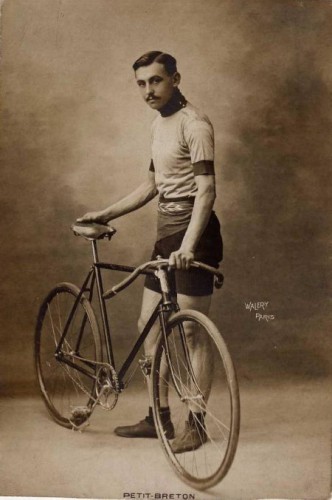

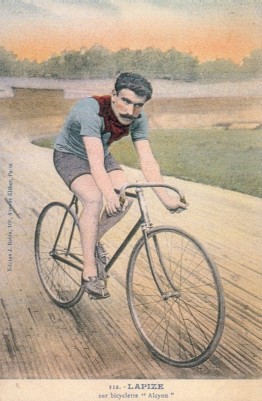

La Coupe du monde de football vient de se terminer; les amateurs de sports tournent leur regard, comme chaque mois de juillet, vers le Tour de France cycliste. La plus célèbre course de vélos du monde se déroule aujourd'hui à l'ombre de celle de 1914, cent ans après que la première guerre mondiale ait éclaté. Le départ d'une étape à Ypres, le passage du peloton le long du champ de bataille de Verdun, les longues étapes en Alsace et en Lorraine en sont la preuve. L'étape qui s'est déroulée sur les pavés du Nord a été, elle aussi, un hommage aux morts de la première guerre mondiale, parce que l'expression "l'enfer du Nord" est née en 1919, quand le parcours de la course Paris-Roubaix était particulièrement sinistre et difficile. Les voies "carrossables" avaient été labourées par les artilleries française, britannique et allemande.  Les médias ont consacré quelques minutes d'attention aux vainqueurs du Tour avant 1914 (le premier Tour a eu lieu en 1903), qui n'ont pas survécu à la première guerre mondiale. Ainsi, Lucien Petit-Breton, vainqueur en 1907 et en 1908, le Luxembourgeois François Faber, vainqueur en 1909, et Octave Lapize, vainqueur en 1910. Petit-Breton a eu une fin misérable: courrier dans l'armée française, il a été renversé par une calèche menée par un cocher ivre. On n'a jamais retrouvé de traces du Luxembourgeois Faber, engagé dans la Légion Etrangère. Il combattait dans la région de la Somme et a disparu le 9 mai 1915 lors d'un combat à proximité d'Arras. Lapize, peut-on dire, a eu la mort du héros: pilote d'un avion de reconnaissance de la toute jeune aviation française, il a été abattu le 14 juillet 1917 en Lorraine.

Les médias ont consacré quelques minutes d'attention aux vainqueurs du Tour avant 1914 (le premier Tour a eu lieu en 1903), qui n'ont pas survécu à la première guerre mondiale. Ainsi, Lucien Petit-Breton, vainqueur en 1907 et en 1908, le Luxembourgeois François Faber, vainqueur en 1909, et Octave Lapize, vainqueur en 1910. Petit-Breton a eu une fin misérable: courrier dans l'armée française, il a été renversé par une calèche menée par un cocher ivre. On n'a jamais retrouvé de traces du Luxembourgeois Faber, engagé dans la Légion Etrangère. Il combattait dans la région de la Somme et a disparu le 9 mai 1915 lors d'un combat à proximité d'Arras. Lapize, peut-on dire, a eu la mort du héros: pilote d'un avion de reconnaissance de la toute jeune aviation française, il a été abattu le 14 juillet 1917 en Lorraine. Le hasard a voulu que le Tour de 1914 ait commencé le 28 juin, le jour même où l'héritier du trône impérial austro-hongrois et son épouse la Comtesse Sophie Chotek ont été assassinés à Sarajevo par l'activiste Gavrilo Princip. Cet assassinat a été le coup d'envoi de la première grande conflagration mondiale mais on ne l'imaginait pas encore quand le départ du Tour a été donné. Pendant la première étape, d'Abbeville au Tréport, personne n'a songé aux événements qui venaient de marquer l'Empire austro-hongrois.

Le hasard a voulu que le Tour de 1914 ait commencé le 28 juin, le jour même où l'héritier du trône impérial austro-hongrois et son épouse la Comtesse Sophie Chotek ont été assassinés à Sarajevo par l'activiste Gavrilo Princip. Cet assassinat a été le coup d'envoi de la première grande conflagration mondiale mais on ne l'imaginait pas encore quand le départ du Tour a été donné. Pendant la première étape, d'Abbeville au Tréport, personne n'a songé aux événements qui venaient de marquer l'Empire austro-hongrois.  Le Tour de France de 1914 s'est déroulé sans le moindre souci. A Cherbourg, les coureurs se trouvaient dans le même hôtel que la figure de proue du socialisme français, Jean Jaurès, avec qui ils ont plaisanté. Juste avant que n'éclate la guerre, cet homme politique a été assassiné. On pouvait déceler bien des indices prouvant la tension croissante entre puissances européennes mais les coureurs en riaient, en disant que des événements plus graves avaient ponctué la politique internationale au cours des quinze dernières années.

Le Tour de France de 1914 s'est déroulé sans le moindre souci. A Cherbourg, les coureurs se trouvaient dans le même hôtel que la figure de proue du socialisme français, Jean Jaurès, avec qui ils ont plaisanté. Juste avant que n'éclate la guerre, cet homme politique a été assassiné. On pouvait déceler bien des indices prouvant la tension croissante entre puissances européennes mais les coureurs en riaient, en disant que des événements plus graves avaient ponctué la politique internationale au cours des quinze dernières années.

Ledesma fue un doctrinario, pero también un hombre de acción. Era consciente de que meditar sobre las ideas solo es admisible si se tiene el valor de llevarlas a la práctica. Eso implica elegir una estrategia, unas tácticas, unos objetivos políticos, un criterio organizativo y formar una clase política dirigente. Se ha aludido bastante al Ramiro Ledesma doctrinario, pero nada en absoluto al estratega político. Y a partir de 1933 tenía una estrategia muy clara: la formación de un “gran partido fascista español” que agrupara a distintas ramas dispersas hasta entonces y a distintos líderes, necesarios todos ellos para alcanzar la masa crítica suficiente para derrocar a la frustrada república y construir un Estado Nacional Sindicalista. En ese sentido, el camino seguido por Ledesma es la estrategia de construcción del partido sumando distintas fuerzas ya existentes y dispersas hasta ese momento, algunas de las cuales incluso en el mundo anarco-sindicalista. Si Ledesma participó en la experiencia de El Fascio fue precisamente por eso, para favorecer una iniciativa unitaria, y si a última hora lanzó Nuestra Revolución fue para crear un medio “aceptable” para que sectores del anarco-sindicalismo asumieran los mismos ideales por los que estaba trabajando Falange Española.´

Ledesma fue un doctrinario, pero también un hombre de acción. Era consciente de que meditar sobre las ideas solo es admisible si se tiene el valor de llevarlas a la práctica. Eso implica elegir una estrategia, unas tácticas, unos objetivos políticos, un criterio organizativo y formar una clase política dirigente. Se ha aludido bastante al Ramiro Ledesma doctrinario, pero nada en absoluto al estratega político. Y a partir de 1933 tenía una estrategia muy clara: la formación de un “gran partido fascista español” que agrupara a distintas ramas dispersas hasta entonces y a distintos líderes, necesarios todos ellos para alcanzar la masa crítica suficiente para derrocar a la frustrada república y construir un Estado Nacional Sindicalista. En ese sentido, el camino seguido por Ledesma es la estrategia de construcción del partido sumando distintas fuerzas ya existentes y dispersas hasta ese momento, algunas de las cuales incluso en el mundo anarco-sindicalista. Si Ledesma participó en la experiencia de El Fascio fue precisamente por eso, para favorecer una iniciativa unitaria, y si a última hora lanzó Nuestra Revolución fue para crear un medio “aceptable” para que sectores del anarco-sindicalismo asumieran los mismos ideales por los que estaba trabajando Falange Española.´

Alors que Raymond De Becker (1912-1969) vivait misérablement à Paris après la guerre, on l’aurait bien étonné si on lui avait dit qu’il ferait l’objet d’un colloque universitaire dans son pays, une quarantaine d’années après sa mort. Ce sont les actes de ce colloque qui sont édités aujourd’hui. Qui était Raymond De Becker et quel lien (indirect) avec Céline ? Ce journaliste belge, auteur du mémoriel Livre des Vivants et des Morts (1942), dirigea le quotidien Le Soir durant l’Occupation. Raison pour laquelle il fut lourdement condamné à la Libération. En mars 1941, il participa, aux côtés d’Édouard Didier, à la fondation des Éditions de la Toison d’Or derrière lesquelles se trouvait le groupe de presse allemand Mundus qui dépendait du Ministère des Affaires Étrangères allemand. Entre 41 et 44, la Toison d’Or publi

Alors que Raymond De Becker (1912-1969) vivait misérablement à Paris après la guerre, on l’aurait bien étonné si on lui avait dit qu’il ferait l’objet d’un colloque universitaire dans son pays, une quarantaine d’années après sa mort. Ce sont les actes de ce colloque qui sont édités aujourd’hui. Qui était Raymond De Becker et quel lien (indirect) avec Céline ? Ce journaliste belge, auteur du mémoriel Livre des Vivants et des Morts (1942), dirigea le quotidien Le Soir durant l’Occupation. Raison pour laquelle il fut lourdement condamné à la Libération. En mars 1941, il participa, aux côtés d’Édouard Didier, à la fondation des Éditions de la Toison d’Or derrière lesquelles se trouvait le groupe de presse allemand Mundus qui dépendait du Ministère des Affaires Étrangères allemand. Entre 41 et 44, la Toison d’Or publi

C’est à Sarajevo, l’ancienne capitale de la Roumélie assujettie aux Turcs, qu’elle se produit. L’Autriche avait reçu la tutelle sur la Bosnie-Herzégovine par le traité de San Stefano en 1878. En 1908, elle a mis l’Europe devant le fait accompli en l’annexant purement et simplement. Acte inadmissible pour les nationalistes serbes. Le 28 juin 1914, un exalté, Gavrilo Princip, assassine l’archiduc François-Ferdinand, l’héritier de la couronne, sur un pont de Sarajevo. L’incident aurait pu en rester là ou n’avoir que des conséquences restreintes ; au pire, l’Autriche aurait pu avoir, de la part des autres puissances continentales, l’autorisation de « punir » la Serbie... Mais cela, la Russie n’en veut à aucun prix. Et l’effrayante logique des alliances internationales va transformer cet attentat somme toute anodin en détonateur de la Première Guerre mondiale. « En cet été 1914, l’équilibre fragile et compliqué de l’Europe, les combinaisons des chancelleries et les calculs des hommes politiques ont été emportés en quelques instants par le complot d’un obscur groupuscule d’officiers et d’adolescents d’un lointain pays balkanique, qui ne savaient rien de la politique mondiale et ne voulaient qu’une chose : assouvir leur haine de l’Empire austro-hongrois » (Dominique Venner).

C’est à Sarajevo, l’ancienne capitale de la Roumélie assujettie aux Turcs, qu’elle se produit. L’Autriche avait reçu la tutelle sur la Bosnie-Herzégovine par le traité de San Stefano en 1878. En 1908, elle a mis l’Europe devant le fait accompli en l’annexant purement et simplement. Acte inadmissible pour les nationalistes serbes. Le 28 juin 1914, un exalté, Gavrilo Princip, assassine l’archiduc François-Ferdinand, l’héritier de la couronne, sur un pont de Sarajevo. L’incident aurait pu en rester là ou n’avoir que des conséquences restreintes ; au pire, l’Autriche aurait pu avoir, de la part des autres puissances continentales, l’autorisation de « punir » la Serbie... Mais cela, la Russie n’en veut à aucun prix. Et l’effrayante logique des alliances internationales va transformer cet attentat somme toute anodin en détonateur de la Première Guerre mondiale. « En cet été 1914, l’équilibre fragile et compliqué de l’Europe, les combinaisons des chancelleries et les calculs des hommes politiques ont été emportés en quelques instants par le complot d’un obscur groupuscule d’officiers et d’adolescents d’un lointain pays balkanique, qui ne savaient rien de la politique mondiale et ne voulaient qu’une chose : assouvir leur haine de l’Empire austro-hongrois » (Dominique Venner). Le plan allemand, initié par le feld-maréchal comte von Schlieffen, prévoit de tourner les forces défensives françaises par la Belgique puis de fondre sur Paris. Il est en effet indispensable de remporter rapidement la victoire sur le front occidental pour pouvoir se retourner ensuite contre les Russes. En quelques semaines, les six armées allemandes bousculent les forces françaises sur plusieurs centaines de kilomètres. La route de Paris semble ouverte. Mais lors d’un sursaut extraordinaire, les Français s’arc-boutent sur la Marne et stoppent les Allemands, arrachant au général von Moltke cet aveu : « Que des hommes, après avoir battu en retraite pendant dix jours, couchant sur le sol, épuisés de fatigue, puissent être capables de reprendre le fusil et d’attaquer quand sonnent les clairons, c’est une chose que nous n’avions jamais envisagée, une éventualité que l’on n’étudiait pas dans nos écoles de guerre. » Le Kronprinz, dans une déclaration aussi prémonitoire que pathétique, s’inquiète : « A la bataille de la Marne, s’accomplit le tragique destin de notre peuple ». Maurice Barrès lui répond : « C’est l’éternel miracle français, le miracle de Jeanne d’Arc… » Le 11 septembre, il est clair que les Français ont gagné la bataille de la Marne. Le « coup de faux » prévu par les Allemands a échoué, et avec lui la guerre-éclair qui devait libérer le front Ouest. La course à la mer qui la suit finit de figer les positions. Non, aucun soldat ne sera de retour dans ses foyers pour Noël : il y aura bien d’autres Noël de boue et de sang… « Avec mon harnais sur le dos, avec toutes ces annexes de cuir et de fer, j’étais couché dans la terre. J’étais étonné d’être ainsi cloué au sol ; je pensais que ça ne durerait pas. Mais ça dura quatre ans. La guerre aujourd’hui, c’est d’être couché, vautré aplati. Autrefois, la guerre c’étaient des hommes debout. La guerre d’aujourd’hui, ce sont toutes les postures de la honte » (Drieu la Rochelle).

Le plan allemand, initié par le feld-maréchal comte von Schlieffen, prévoit de tourner les forces défensives françaises par la Belgique puis de fondre sur Paris. Il est en effet indispensable de remporter rapidement la victoire sur le front occidental pour pouvoir se retourner ensuite contre les Russes. En quelques semaines, les six armées allemandes bousculent les forces françaises sur plusieurs centaines de kilomètres. La route de Paris semble ouverte. Mais lors d’un sursaut extraordinaire, les Français s’arc-boutent sur la Marne et stoppent les Allemands, arrachant au général von Moltke cet aveu : « Que des hommes, après avoir battu en retraite pendant dix jours, couchant sur le sol, épuisés de fatigue, puissent être capables de reprendre le fusil et d’attaquer quand sonnent les clairons, c’est une chose que nous n’avions jamais envisagée, une éventualité que l’on n’étudiait pas dans nos écoles de guerre. » Le Kronprinz, dans une déclaration aussi prémonitoire que pathétique, s’inquiète : « A la bataille de la Marne, s’accomplit le tragique destin de notre peuple ». Maurice Barrès lui répond : « C’est l’éternel miracle français, le miracle de Jeanne d’Arc… » Le 11 septembre, il est clair que les Français ont gagné la bataille de la Marne. Le « coup de faux » prévu par les Allemands a échoué, et avec lui la guerre-éclair qui devait libérer le front Ouest. La course à la mer qui la suit finit de figer les positions. Non, aucun soldat ne sera de retour dans ses foyers pour Noël : il y aura bien d’autres Noël de boue et de sang… « Avec mon harnais sur le dos, avec toutes ces annexes de cuir et de fer, j’étais couché dans la terre. J’étais étonné d’être ainsi cloué au sol ; je pensais que ça ne durerait pas. Mais ça dura quatre ans. La guerre aujourd’hui, c’est d’être couché, vautré aplati. Autrefois, la guerre c’étaient des hommes debout. La guerre d’aujourd’hui, ce sont toutes les postures de la honte » (Drieu la Rochelle).