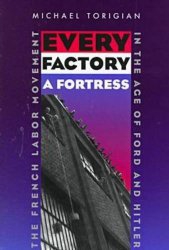

Michael Torigian

Michael Torigian

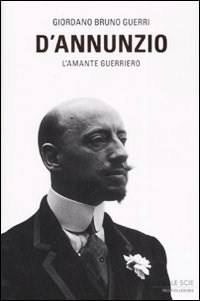

Every Factory a Fortress: The French Labor Movement in the Age of Ford and Hitler

Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1999

Michael Torigian’s Every Factory a Fortress: The French Labor Movement in the Age of Ford and Hitler chronicles the rise and decline of the French Labor movement from the years surrounding the First World War to the outbreak of the Second, culminating in a storm of labor agitation from 1934-1940.

It tells the story of how the working class responded to the social changes introduced by the Fordist-Taylorist model of production that became prevalent during World War I. The rise of the labor movement in these decades lead to the establishment of the Parti Communiste Français (PCF) as a major political force. They faced a great deal of challenges that manifested as strife on the factory floor, within the unions, against the various other factions in French politics, and internationally.

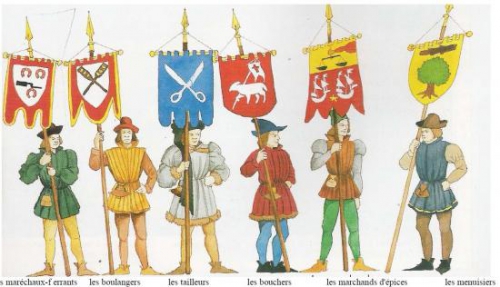

Torigian focuses particularly on the most powerful and radical element of the labor movement, the metal workers, termed métallos in French. These workers were involved in the various trades of steel making, shipbuilding, re-forging, mechanical manufacturing, electrical manufacturing, airplane, automobile, and defense manufacturing, and other miscellaneous metal fabrication. They would play a pivotal role in the wave of strikes and factory occupations that occurred in the years immediately preceding the Second World War.

In addition to the labor struggle, the threat of a Fascist coup in 1934 and the impending war with Germany, made the labor movement a part of the left wing French resistance to Fascism, yet the tension between the international political concerns and economic issues facing the workers would prove to deleterious to the unions and the PCF as the nation lurched towards the Second World War.

Every Factory a Fortress begins with an overview of the transformation of the French metal industry in the years surrounding the First World War. Perhaps the most drastic of all the changes was the adoption of the Fordist-Taylorist mode of production. In the years before the First World War, the metal industry was essentially based in craft workshops, which required a certain amount of skilled labor, and some familiarity with mathematics and drafting as well as manufacturing. It was an essentially artisanal trade.

The First World War would be the beginning of the end for the small workshop. Industrial production would be concentrated in large factories, often employing thousands of workers, which would utilize mechanized, standardized mass production techniques as developed by Henry Ford and Frederick W. Taylor. These would be detrimental to the conditions of the worker. In the old workshops, the craftsman enjoyed a degree of independence and the respect of the foremen. Management rarely intervened in the day-to-day life of the worker.

The Fordist-Taylorist system would replace much of the skilled labor needed with machines, and their operators would be subjected to dehumanizing “scientific management.” Engineers and management would dictate the most effective means of production to the workers, who were reduced to performing repetitive and often dangerous industrial routines as part of an assembly line, often timed by a stopwatch. Failure to keep pace would result in the dismissal of the worker, thus making employment less secure.

This was compounded by the fact that the bosses, termed the patronat, viewed themselves as rulers of the workers, and refused to recruit higher level positions from the laborers, preferring to hire engineers and managers from outside. This lack of social mobility would compound the divide between the workers and the patronat.

The conditions of the war furthered the problems inherent in the system. The fact that many men were out at the front, and would die as a result of the war, meant that women, immigrants, and boys were brought in to fill their roles in the war years and those following. Paid less and easily replaced, this furthered the degradation of skilled labor.

The high turnover in the metal industry following the First World War would have serious social consequences as well. The lack of job security and the flux of employment that resulted from workers constantly leaving factories in search of higher wages led to a fairly nomadic existence. The rooted communities based upon the skilled workers of the workshop ceased to exist and workers crowded into hastily constructed suburbs, which lacked adequate electricity, sanitation, and other basic amenities. Tuberculosis, diphtheria, and other communicable diseases took their toll, and child mortality increased.

The decline of the traditional working communities and the rise of atomized life in the slums provided an opening for mass, consumer culture to replace the organic bonds of society. Sports, radio broadcasts, and cinema became popular diversions French culture became Americanized, Hollywoodized, as one trade unionist noted, “Today, life inside and outside the factories is similar to life in America and has no other aim than the pursuit of crass material satisfaction . . . To achieve this satisfaction people seem willing to accept any kind of servitude.” Moreover, the rise of consumerism distracted the working class from political and economic goals.

The labor movement in France was descended from the ideology of revolutionary syndicalism, which held that the workers would rise up and seize control of the workshops. In the aftermath of the First World War, it proved to be antiquated, as it focused on the concerns of skilled workers in the atmosphere of the workshops that dominated before the rise of the mass industrial system.

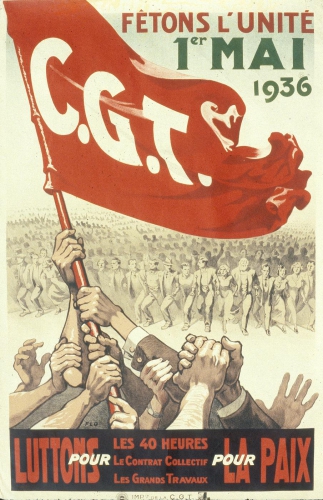

Represented by the Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT), they adopted an anarchist position and refused to negotiate with political parties or form their own to represent themselves, codifying their beliefs in the 1906 Charter of Amiens. Opposed to negotiation with bosses and politicians, the CGT used wildcat strikes, boycotts, and sabotage to advocate for worker control. However, membership remained low, and poor organization stifled its ability to pursue extended strikes.

Divergences between the more reformist and the revolutionary wings began to arise and were furthered by the First World War, as the working class was unequivocally patriotic in their support of the war effort. This lead the CGT to reject direct action in favor of negotiation. However, the new workers in the war industry did not take to the CGT, preferring more mass movement-oriented action over the skilled labor elite of the CGT.

In 1917 there was a round of strikes, opposed by CGT representatives, who sought to protect the interests of skilled laborers from the demands of the masses. In March 1918, another round of strikes lead by anti-reformist dissident stewards broke out. Furthermore, the Russian Revolution had piqued the interest of the more revolutionary segments of the labor movement.

In the waning months of the war, reformist elements sought to codify some of the state-directed socialist aspects of the war economy to mitigate the threat of revolution, proposing nationalization, collective management, and state resolution of contract disputes. However, the end of the war restored the full free market, and the unions lost whatever leverage they enjoyed during the war.

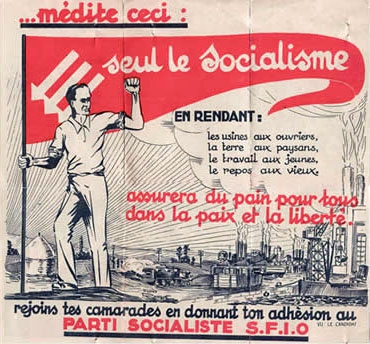

This strengthened the hand of revolutionary syndicalists and the new Soviet-oriented groups. In June 1919, anarchist stewards lead nearly 180,000 workers in a month long strike, where a Soviet was proclaimed in Saint-Denis. The refusal of the CGT leadership to endorse the strikes only exacerbated tensions between the revolutionaries and the reformists. This led to creation of the PCF from a split in the Socialist Party in 1920, and workers began to rally to this new “worker’s party.”

The reformist leadership began to purge the revolutionaries aligned with the PCF, who formed the Confédération Générale du Travail Unitaire (CGTU) in 1922. The CGTU experienced infighting between syndicalists, anarchists, and communists, but by 1923 had enough control to bring the CGTU into the Soviet backed Red International of Labor Unions and organize the union according to Bolshevism. The Unitaires, as CGTU members were called, in the metal industry were used as the political laboratory of the CGTU, where “every change of line, every new directive, every political imperative cooked up by the French and international communist movement would thus find its way into the union’s daily operations.”

One particular organizational change used by the CGTU was to shift the base of operations from the section locale, which represented union by neighborhood, to the section syndicale, which represented workers directly on the factory floor, thus implanting the CGTU into the daily workings of the factory. Unfortunately, the factory sections were hampered by management intimidation and logistics. Both the CGTU and the “confederal” CGT failed to achieve much progress throughout the twenties in terms of concrete gains for their members.

It was the onset of the Great Depression that would strengthen the hand of labor in France. The contraction in the labor movement would end the high turnover in the factories. Immigration, migration from the countryside, and female labor participation decreased, and skilled workers and family men were given priority. This essentially stabilized the environment on the factory floor, which would allow the labor movement to take root. Moreover, the conditions inside the factory worsened in terms of stagnating wages, production speedups, and longer hours. The stabilization of the workforce, combined with more unpleasant conditions lead to a greater need for labor activism.

The CGT tried to organize within the communist dominated suburbs, but were hampered by the union locale mode of organization where unions were represented by locals outside the factory, which led to a lack of contact between the worker and union. The unitaires were better prepared to unionize the métallos, using the section syndicale to reach workers directly on the factory floor. The PCF also utilized factory cells to recruit.

In 1930, direct orders from the Soviet Union forced the CGTU and PCF to reduce their revolutionary rhetoric and focus more on the day-to-day struggles of the workers, which helped end the marginalization they suffered in the preceding years. In 1932 the CGTU started making more concrete demands than full scale revolution like the 40 hour week, guaranteed minimum wages, collective bargaining, and health and safety guarantees. However, the revolutionary core was still present in the party, though reigned in. These radical activists would prove useful in leading future agitation. An increase in strike activity by the CGTU from 1931 to 1933 would result from the turn towards the concerns of the common worker. The CGTU took on the prominent French auto manufacturer, Renault, in November 1931 after a large wage cut was announced. The strike broke out on a shop by shop level, leading to a two month struggle with management. While the strike failed, it raised the credibility of the CGTU in the eyes of the workers. In 1933, the CGTU fomented a massive strike at the plant of Citroen after wage cut announcements were made. After a work stoppage by 300 craftsmen, CGTU agitation eventually caused Citroen to lockout 18,000 workers. Strike committees were formed as intermediaries between union leadership and the workers. Citroen eventually reopened its factories and the promised a mitigation of the wage cut, and the workers returned in blocs, who would engage in slowdowns to force the factory to keep their promises and rehire strikers. While the strike did not bring Citroen to heel completely, it solidified the role of the CGTU as the leader of labor activism in the metal industry.

The events of February 1934 France would have a major impact on the labor movement. The Stavisky Affair, which revealed that several members of the cabinet were connected to the Jewish swindler Serge Stavisky, inflamed the passions of the far right, and led to a series of demonstrations in January 1934 by organizations like Action Française and Croix de Feu of a generally an anti-democratic character.

On February 3rd, Premier Daladier dismissed the right-wing prefect of the police, leading to massive demonstrations on the 6th. 100,000 rightists marched on the Chamber of Deputies, and police opened fire, killing 18 and leaving 18,000 wounded. Fearing impending civil war, the government resigned.

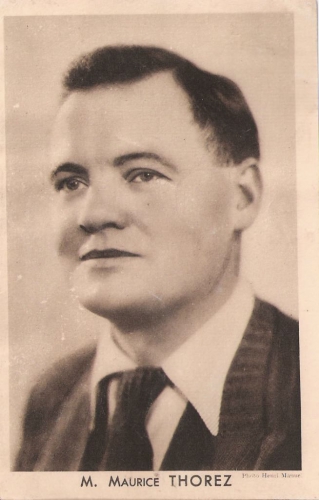

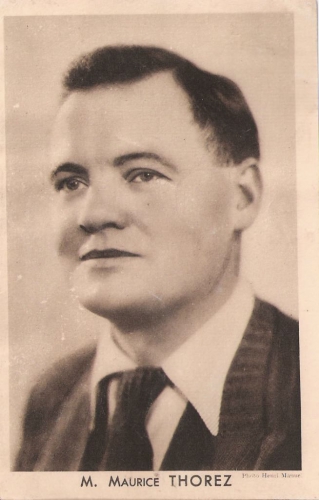

The initial response of the communists was indifferent. PCF leader Maurice Thorez stated that there was “ no difference between bourgeois democracy and fascism. They are two forms of capitalism . . . Between cholera and the plague one does not choose.” On the 7th of February, the PCF rejected a socialist overture to form a united front against what was widely perceived as a Fascist coup attempt.

The initial response of the communists was indifferent. PCF leader Maurice Thorez stated that there was “ no difference between bourgeois democracy and fascism. They are two forms of capitalism . . . Between cholera and the plague one does not choose.” On the 7th of February, the PCF rejected a socialist overture to form a united front against what was widely perceived as a Fascist coup attempt.

Interestingly enough, it was PCF member and future Fascist Jacques Doriot that broke ranks with the party leadership to propose an alliance with the Section Française de l’Internationale Ouvrière (SFIO) against the anti-republican forces. In response, Thorez announced a demonstration on February 9th against fascism and Daladier’s cabinet. The demonstration was banned, but it went ahead anyhow, resulting in street fighting that left six dead. In response a general strike was called on February 12th, mobilizing four million workers across the country.

In this action, the strikers saw themselves not as agents of revolutionary class struggle, but as defenders of French democratic institutions derived from the French Revolution. This in turn would lead to the formation of alliances between the PCF and the less revolutionary factions of the French left. The PCF joined the SFIO to formulate a “united action pact.” With German rearmament posing a threat to Soviet Union, the PCF was forced to abandon its criticism of French democracy and seek alliances with potential allies against a future German assault within the political sphere. Steps were taken to reunify the CGT and the CGTU, but they had yet to produce any results. The new-found moderation of the PCF and CGTU and their symbolic defense of the republic proved to be quite successful in convincing workers to join, swelling the ranks in the metal union enough for them to put out a weekly paper, Le Métallo.

The Franco-Soviet Pact of Mutual Assistance in May 1935 forced further rapprochement between the PCF and the French state, which opened the way for an alliance with the Radicals, the bourgeois liberal party. The PCF increasingly appealed to French patriotism against the threat of Germany, wrapping themselves “so tightly in the French flag that the hammer and sickle would barely be visible.” The May 1935 election would also see the formation of a People’s Front observing “republican discipline,” where voters would vote for the strongest Left-wing party on the second ballot. This lead to massive gains for the PCF, moving the number of cities and towns under PCF control from 150 to 297.

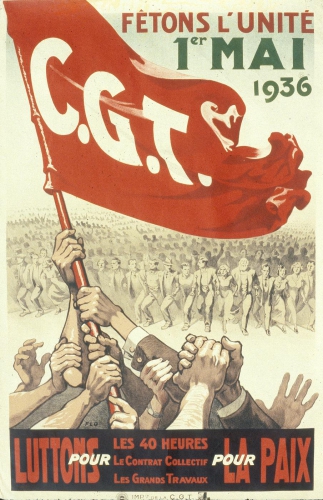

In June 1935, the Comité de Rassemblement Populaire was formed to bring together the PCF, SFIO, CGT, CGTU, and Radicals to organize a pro-republican Bastille Day rally. However, it decided to maintain itself afterwards and align with the People’s Front in support of republican defense. However, the various factions were in dispute on a number of issues, and it would take until January 1936 for them to codify a program, based around international defense against fascism, suppression of the right-wing leagues, and some fairly vague promises of restoring the worker’s purchasing power harmed by the depression through a fairly Keynesian program. A GCT-CGTU merger would follow in March of 1936.

The political gains and consolidation of the left would help support and organize labor activism in the future. In 1935, the first major successes of the CGTU soon followed, the Gnome-et-Rhône aircraft works granted labor demands after the threat of a strike, and similar victories in the Panhard-Levassor auto plant, the Chausson auto works, Hispano-Souza, and the aircraft plants of Bloch, CAMS, and Loiré-Olivier soon followed.

The 1936 parliamentary elections would intensify the momentum of the French labor movement, the Communists growing from 10 to 72 seats. However, parties of the extreme right had also made significant gains. The atmosphere of polarization grew as the moderate bourgeois liberal parties were reduced in strength. 120,000 workers rose in a May Day strike. The Bréguet aviation plant fired two militants in reprisal for their role in the May Day strike, which triggered an occupation. When police arrived to evict them, they barricaded themselves into the workshop bearing the company’s prototypes. The management recalled the police and opened negotiations when they refused to leave. The striker’s demands were satisfied. Another strike broke out, possibly encouraged by the PCF’s Toulouse branch, in the Latécoère aviation plant and it was settled in the workers favor in a manner similar to the Bréguet strike. The wave of factory occupations struck the capital region, notably at the Bloch plant, where a strike aided by PCF deputies and the Communist mayor of Courbevoie succeeded in granting a new contract with a large raise to the workers.

However, the leadership of the PCF, was not entirely pleased by these actions, as they had joined the People’s Front to maintain the force of the French government against the rising power of German Fascism. PCF organ L’Humanité urged the workers to “refrain from wild revolutionary gestures.” However, the new People’s Front government had buoyed the worker’s hope for economic reform, and they would go ahead with or without Communist support.

A demonstration in memory of the Paris Commune of 1871 on May 24th drew 600,000 workers, furthering the fervor of the movement, as syndicalist Pierre Monatte remarked, “When you feel strong in the streets, you can no longer feel like a slave in the factory.” The Tuesday following the commemoration of the Commune, 4,000 workers occupied six metal plants. This strike would spread, on Thursday 33,000 Renault workers would join. Attempts to resolve the strikes on June 1st failed when the employers refused to sign a contract. On June 2nd, 60 factories were occupied, and the strike had spread to other regions of France. The union leaders who had advocated caution in order to maintain their political position were ignored as the movement gained a life of its own.

On June 7th, an agreement, dubbed the Matignon Accords, was reached, which promised recognition of the union, a 7 to 15 percent raise, and a system of shop stewards. Other demands would be resolved later. However, the employers immediately had reservations, and the most of the striking workers saw no reason to leave, believing the accords were too loose. By the 9th of June, four million workers remained on strike.

Fear of a revolution reached fever pitch as labor delegates rejected the employers’ concessions, demanding four non-negotiable things: a serious wage increase, paid vacation, payment for the days on strike, and satisfaction of the striking technicians’ demands. The government, fearing civil war, hurriedly passed a forty-hour week, paid vacation, and collective bargaining. Thorez, fearing that that the strike would break the People’s Front, called on workers to bring the strikes to an end, and on the 12th of June, the union signed a contract with the employer’s collective, the UIMM, which granted paid vacation, raises, and shop stewards, and the union was recognized as the sole bargaining agent of the workers. Further bargains between individual factories were struck on the 13th and 14th, and work resumed on the 15th. The workers viewed this as a great triumph, and the strikers evacuated the plants to great fanfare.

The employers responded to the new system with a series of indirect attacks on the Matignon Accords, firing stewards, reclassifying categories of workers, and delaying the implementation of the contract. The employers’ actions intensified the workers’ defiance, augmented by the fact that many of the new union recruits were inexperienced in dealing with the formalities of negotiation and came to unionism in the surge of labor radicalism. The union leadership was presented with problems from the confrontational attitude of the new stewards, who sought to flex their new found power at the least provocation from management. The PCF worried that further conflicts with the patronat would damage the political strength of the People’s Front. CGT leader Jouhaux urged employees to ignore “employer provocations” and wait for the government to arbitrate disputes.

The advent of the Spanish Civil War would further the rifts developing in the People’s Front further. The Blum government bowed to public pressure and refused to aid the loyalists in the conflict. For the PCF and the CGT this was akin to the endorsement of fascism. A one-hour general strike in protest of France’s non-intervention was called for on the 7th of September. While supported by the Communists, it had the effect of inflaming the tensions between them and the syndicalists and socialists opposed to further warfare in Europe, and the SFIO announced its opposition to the strike on the grounds that it would threaten the People’s Front government.

To counter the Communist influence in the factories, the SFIO formed the Amicales Socialistes d’Enterprise, a rival union. Some former confederals in the CGT also took an anti-communist, pacifist line spread through their organ Syndicats. About a third of the CGT, sympathetic to revolutionary syndicalism supported the Syndicats group. At the first meeting of the Metal Federation’s congress after CGT-CGTU reunification, attempts were made to preserve the spirit of unity, and two of six executive positions were reserved for confederals. However, following the passage of a compulsory government arbitration bill for strikes, which the CGT accepted, and Blum’s increasingly conservative policies in the midst of financial crisis, workers became increasingly disgruntled with the union’s willingness to support the government, and anarchist and Trotskyites formed the Cercle Syndicaliste “Lutte de Classes” in opposition to CGT.

Worker support for the People’s Front government was further eroded in 1937 following the rise of the fascist Parti Sociale Français (PSF). Following the fatal shootings of six workers by policemen in an anti-fascist demonstration at Clichy on March 16th, which lead to a call for a half-day strike in protest of the killings, Blum threatened to resign if the strike went ahead, and then failing to do so, ordered the police to crackdown on the workers who allegedly instigated the violence at Clichy.

Worker support for the People’s Front government was further eroded in 1937 following the rise of the fascist Parti Sociale Français (PSF). Following the fatal shootings of six workers by policemen in an anti-fascist demonstration at Clichy on March 16th, which lead to a call for a half-day strike in protest of the killings, Blum threatened to resign if the strike went ahead, and then failing to do so, ordered the police to crackdown on the workers who allegedly instigated the violence at Clichy.

Worker anger at the PCF’s collaboration with Blum was unabashed; one Communist stated, “They massacre the workers, they let revolutionary Spain perish, and it’s L’Humanité and the party that makes us swallow it all.” Violent protests erupted in factories throughout the Paris metal industry. In response, employers increased their repression of the unions, locking out workers and firing militants, even refusing to abide by settled contracts in some cases.

The resignation of Blum, who was replaced by Chautemps, only diminished the workers’ faith in the People’s Front and increased the anger they felt towards the union leadership for collaborating with it. The Amicales, Cercle Syndicaliste, and Syndicats, as well as Catholic and Fascist unions attracted workers. Following the failure of the unions and the employers to agree on a new contract after the expiration on the 31st of December 1937, and the failure of the government to arbitrate new terms, the stage was set for another major wave of conflict between labor and management.

1938 saw the reinstatement of Blum as premier following Chautemps’ resignation. This in turn gave the union leadership impetus to demand an anti-fascist foreign policy in addition to their contractual demands. Blum would increase defense spending to counter Germany’s rearmament, but he demanded the unions make a concession concerning the forty-hour work week. The union was willing to abide by this, provided they received a new contract, but the proposed deal fell through. This failure strengthened the hand of the anti-CGT, anti-PCF groups like the Amicales, Cercle Syndicaliste, and Syndicats, who claimed that the union was overtaken by “war psychosis” to the extent that it ignored the economic objectives close to the workers. The metal unions attempted to convince the Blum government that the employers were sabotaging war production through their treatment of the workers. In twenty metal plants workers struck in 20- to 90-minute waves for a new contract and the opening of the Spanish border. However, this in turn lead to large scale strikes, shutting down Citroen’s seven Paris plants, which did not mention foreign policy concerns at all. The union leadership was unprepared for an intensification of the strike activity, but they had no choice but to allow them to continue if they want to maintain the respect of the laborers. However, when the sections syndicales initiated more strike activity, under orders from the central leadership, the leadership then refused to take responsibility or seize the initiative to guide them, torn between the demands of the workers and the political imperatives of maintaining the government against German rearmament. The indecision of the union leadership, combined with their failure to adequately provide strike pay, soup kitchens, or elect strike committees, left the strikers feeling abandoned, which in turn provided an opportunity for Trotskyites to demonstrate leadership of the strike and agitate for further work stoppages. The PCF response was violent and decisive, and PCF thugs beat any Trotskyite agitators approaching the factories. To compound issues, Catholic and Fascist unions were also attempting to turn the workers against the union leaders, and this resulted in several violent confrontations. In the face of mounting divides in the strikers, the employers saw no reason to soften their stance towards them and adamantly refused to entertain their demands. An offer by union leaders to end the strike following government arbitration and a token wage increase was rebuffed by the employers. This failure only spurred further strikes, by April 8th it consisted of 68,000 workers occupying 40 factories. Blum once again resigned in the face of mounting pressure after failing to obtain special powers to end the strikes.

The Daladier succeeded in gaining the special powers denied to Blum and he ordered troops to occupy Paris. A deal called the Jacomet Sentence was struck for workers in the nationalized aviation sector, providing a 45-hour week and a 7 percent wage increase. This was extended to private sector plants on April 13th, and ratified on the 14th. The entire Paris metal industry returned to work on the 19th.

However, workers began to notice how much the agreement curtailed their rights, effectively destroying many of the gains won with the Matignon Accords. Section meetings, posting of union information, and the collection of dues were restricted or prohibited. Furthermore, employers used punitive firings against labor militants, in express violation of the contract they agreed to. Membership in the metal unions declined by nearly a third. In response to criticism among the ranks, CGT leadership labeled unruly members Trotskyites, fascists, or provocateurs.

Further pressure on the unions arose when the Daladier government appointed center-right politician Paul Reynaud as Finance Minister. His decrees proved particularly intolerable, raising taxes, imposing new pro-employer mechanisms to resolve industrial strife, reestablishing the six-day work week, and giving employers the right to fire or blacklist employees for refusing overtime. These decrees would give the CGT a reason to strike against the Daladier government, with the intent of forcing its resignation. A series of strikes on November 21st to the 24th broke out and raised further pressure of a general strike, forcing police to use violence to remove the occupying strikers. They police succeeded in evicting the strikers from all the plants but Renault, whose management further inflamed tensions by announcing an increase in hours. Union leaders attempting to defuse the situation were ignored and workers prepared a last stand, barricading the doors, and gathering pieces of metal to use as projectiles in the face of a coming police onslaught. 6,000 police faced down 10,000-15,000 workers. The ensuing “Battle of Renault” saw the police deploy tear gas to clear the factory and resulted in serious injury to 46 police, 22 workers, hundreds of lesser injuries, and 500 arrests. Renault locked out 28,000 workers the next day and declared their contract null and void. Between the 25th and 30th, union leadership wavered, giving the government time to prepare further measures against future unrest. A general strike planned for the 30th of November was impeded by the government’s deployment of troops and its requisitioning of workers necessary to the basic functioning of national infrastructure. It is estimated around 75% of the Paris region metal industry participated in the strike, but the end result was total defeat. Entire factories were locked out or had their workforce dismissed, union stewards were fired, 500 strikers were sentenced to prison. Rehired workers had to deal with significantly less protections than the ones they had earned two years earlier, and the non-socialist factions of the state shunning cooperation with the unions and communists.

Following the March 1939 annexation of the remainder of Czechoslovakia by the Germans, repressive conditions in the factories only intensified as a result of hurried military production. However, labor leaders following the Comintern anti-German line, were loath to interrupt the militarization of France against Germany. Then the Molotov-Ribbentrop Non-Aggression Pact between the Soviet Union and Germany threw the leadership into chaos. Daladier accused the PCF of being unfaithful to France and CGT leader Johaux condemned the pact, but resisted calls to remove communists from the CGT. The PCF was thrown into even worse disarray than the CGT, as a third of its elected officials resigned in protest, and the government seized their publications. The German invasion of Poland, forced PCF leader Thorez to accept the war effort, but a direct Soviet order demanded that the PCF denounce the war and sabotage the French war effort. The CGT responded by purging the Communists from its ranks. The PCF was proscribed and forced to go underground. The Communist- dominated metal union was disbanded on the 26th of September. The government’s polices towards labor once again became more repressive, banning collective bargaining, strikes, and freezing wages. Those who objected were interned.

However, government concerns about the threat of labor unrest let to an agreement between labor and management to collaborate in the war effort, called the Majestic Agreement. Yet this collaboration failed to deliver any concrete benefits to the workers. Finally, German victory over France in May 1940 would put the factories at the disposal of the victors, thus ending the period of labor strife that had lasted for six years.

Lessons for White Nationalists

The rise and fall of the French labor movement provides many lessons for any budding political movement. Those on the right should not be afraid of learning from the successes and failures of a supposedly left-wing movement. Indeed, many of the concerns articulated by the labor movement were inherently conservative, if not reactionary, as Torigian notes in his Epilogue.

The rise of the unions had its origin in the reaction to the social dislocations caused by mass production and industrialization. Economic events tore asunder the traditional communities centered around the craft workshop; the spirit of camaraderie that craft workers enjoyed was replaced by mechanized drudgery. The strikes provided the first opportunity in years for workers — who stood shoulder-to-shoulder, bound to machines — to form bonds with one another. During the six years of labor unrest, the unions set up schools, concerts, and vacation homes for their members, giving them some semblance of a community they had lost in the preceding years. The goal of restoring the historical ties of a community severed by modernity shows the deep conservatism beneath the outward trappings of leftist unionism.

Another conservative facet of labor’s rise was the fact that it was jolted from its previous malaise by an appeal to patriotism. It was the call to defend the Republic, and the heritage of the French Revolution, that started the six years of struggle in 1934. As Alain Soral states in “Class Struggle Within Socialism: 1830-1914 [2],” “It is historically demonstrated that the people are always patriotic,” noting that even the Communards of 1871 were reacting against the defeat of Sedan and the Prussian occupation agreed to by the bourgeois government. It was the leadership’s willingness to follow the foreign dictates of Comintern, at the expense of economic and social concerns dear to the average worker, that destroyed the benefits they had achieved through the Matignon accords.

The failure of the People’s Front should also be a lesson to any radical political movement about the dangers of mainstreaming. The willingness to sacrifice the gains the union had achieved for the survival of a political party proved disastrous. The equivocation and willingness to compromise demonstrated by the CGT and PCF in the years following Matignon weakened the resolve in the ranks, diminished membership in the movement, and opened the door for more radical elements to outflank them. The concerns of the people within the movement should take priority over any desire for political expediency. The idea that some politician will be the savior of any particular extreme struggle, left or right, has been disproved time and time again. Those who fail to grasp that would greatly benefit from reading Every Factory A Fortress.

Furthermore, anyone wishes to see how a mass movement can become strong enough to challenge the entrenched interests of the political and economic elite should read Every Factory a Fortress. As the struggles of labor continue in the face of globalization, multiculturalism, unchecked immigration, and other consequences of untrammeled neo-liberalism, the need for a movement to raise its banner against this brazen exploitation grows daily. Only by assimilating the lessons of the period from 1934 to 1940 will it emerge victorious.

Related

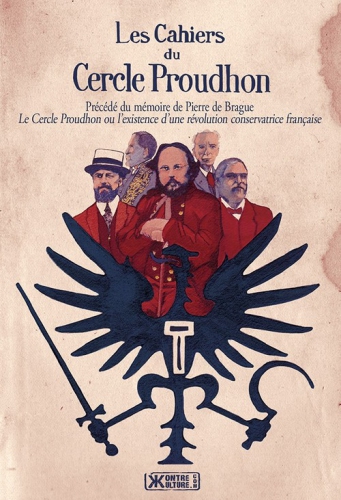

Si l’on s’en tient aux théories, Proudhon, par son fédéralisme, son mutualisme, sa critique acide de la démocratie et de la propriété capitaliste, ainsi que son caractère de farouche pourfendeur de la culture bourgeoise, a su permettre –malgré les tentatives de récupération des socialistes républicains- « à des Français, qui se croyaient ennemis jurés, de s’unir pour travailler de concert à l’organisation du pays français ». Nous touchons là un point essentiel : Proudhon était un homme d’ordre et non cet anti-étatiste anti-théiste et anti-propriétaire primaire que l’on veut nous faire accroire… C’est en tant que prophète de « l’ordre social français » que les membres du Cercle célèbrent ce « grand réaliste », ce « Maître de la contre-révolution », ce « Proudhon constructeur » à l’esprit et à la foi révolutionnaire. J’arrête ici, c’est certainement déjà trop de dialectique pour les quelques placides intellectuels de « gôche » qui prétendent s’accaparer la figure de ce rude fils de paysan, viril et guerrier, inaltérable et hardi défenseur du Travail, de la Famille et de la Terre (qui a dit Patrie ?) ; je ne voudrai pas être désigné responsable de l’ataraxie mentale dont ils souffrent, si peu nombreux soient-ils.

Si l’on s’en tient aux théories, Proudhon, par son fédéralisme, son mutualisme, sa critique acide de la démocratie et de la propriété capitaliste, ainsi que son caractère de farouche pourfendeur de la culture bourgeoise, a su permettre –malgré les tentatives de récupération des socialistes républicains- « à des Français, qui se croyaient ennemis jurés, de s’unir pour travailler de concert à l’organisation du pays français ». Nous touchons là un point essentiel : Proudhon était un homme d’ordre et non cet anti-étatiste anti-théiste et anti-propriétaire primaire que l’on veut nous faire accroire… C’est en tant que prophète de « l’ordre social français » que les membres du Cercle célèbrent ce « grand réaliste », ce « Maître de la contre-révolution », ce « Proudhon constructeur » à l’esprit et à la foi révolutionnaire. J’arrête ici, c’est certainement déjà trop de dialectique pour les quelques placides intellectuels de « gôche » qui prétendent s’accaparer la figure de ce rude fils de paysan, viril et guerrier, inaltérable et hardi défenseur du Travail, de la Famille et de la Terre (qui a dit Patrie ?) ; je ne voudrai pas être désigné responsable de l’ataraxie mentale dont ils souffrent, si peu nombreux soient-ils.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Or le malheur des Turcs, et de leurs victimes, aura été, il y a exactement un siècle, après une dernière année de règne ambigu d'Abdül-Hamid II, la victoire de ces habiles révolutionnaires. Ils admiraient la révolution jacobine française. Leur chef Enver pacha devint alors ce 24 avril 1909 le maître véritable du pouvoir. Un nouveau sultan, le fantoche Rechad Effendi allait régner nominalement sous le nom de Mehmed V jusqu'à sa mort en juillet 1918. Le grand vizir, et le parti de l'Union libérale, en même temps que les alliés de l'Ancien régime furent peu à peu éliminés, au fur et à mesure des désastres rencontrés lors des deux guerres italo-turque de 1911-1912 puis balkaniques de 1912-1913 qui avaient pratiquement mis un terme à la présence turque en Europe.

Or le malheur des Turcs, et de leurs victimes, aura été, il y a exactement un siècle, après une dernière année de règne ambigu d'Abdül-Hamid II, la victoire de ces habiles révolutionnaires. Ils admiraient la révolution jacobine française. Leur chef Enver pacha devint alors ce 24 avril 1909 le maître véritable du pouvoir. Un nouveau sultan, le fantoche Rechad Effendi allait régner nominalement sous le nom de Mehmed V jusqu'à sa mort en juillet 1918. Le grand vizir, et le parti de l'Union libérale, en même temps que les alliés de l'Ancien régime furent peu à peu éliminés, au fur et à mesure des désastres rencontrés lors des deux guerres italo-turque de 1911-1912 puis balkaniques de 1912-1913 qui avaient pratiquement mis un terme à la présence turque en Europe.

Je poursuis ici nos investigations dans les documents de mise en oeuvre de la Constitution de la Cinquième République telle qu’elle a été portée sur les fonts baptismaux par Charles de Gaulle en 1958.

Je poursuis ici nos investigations dans les documents de mise en oeuvre de la Constitution de la Cinquième République telle qu’elle a été portée sur les fonts baptismaux par Charles de Gaulle en 1958.

The initial response of the communists was indifferent. PCF leader Maurice Thorez stated that there was “ no difference between bourgeois democracy and fascism. They are two forms of capitalism . . . Between cholera and the plague one does not choose.” On the 7th of February, the PCF rejected a socialist overture to form a united front against what was widely perceived as a Fascist coup attempt.

The initial response of the communists was indifferent. PCF leader Maurice Thorez stated that there was “ no difference between bourgeois democracy and fascism. They are two forms of capitalism . . . Between cholera and the plague one does not choose.” On the 7th of February, the PCF rejected a socialist overture to form a united front against what was widely perceived as a Fascist coup attempt. Worker support for the People’s Front government was further eroded in 1937 following the rise of the fascist Parti Sociale Français (PSF). Following the fatal shootings of six workers by policemen in an anti-fascist demonstration at Clichy on March 16th, which lead to a call for a half-day strike in protest of the killings, Blum threatened to resign if the strike went ahead, and then failing to do so, ordered the police to crackdown on the workers who allegedly instigated the violence at Clichy.

Worker support for the People’s Front government was further eroded in 1937 following the rise of the fascist Parti Sociale Français (PSF). Following the fatal shootings of six workers by policemen in an anti-fascist demonstration at Clichy on March 16th, which lead to a call for a half-day strike in protest of the killings, Blum threatened to resign if the strike went ahead, and then failing to do so, ordered the police to crackdown on the workers who allegedly instigated the violence at Clichy.

Pierre Drieu la Rochelle n’a éjaculé qu’une seule fois dans sa vie : c’était le 23 août 1914, lors d’une chaude journée de guerre dans la plaine de Charleroi. Ce jour-là, le caporal de 21 ans vit sa première épreuve du feu. Soudain, au milieu de l’affrontement, il se lève, comme s’il n’avait plus peur de la mort, charge son fusil et entraîne plusieurs camarades. L’enivrement que lui procure la sensation d’être devenu le chef qu’il a toujours rêvé d’incarner est comme un orgasme sexuel. « Alors, tout d’un coup, il s’est produit quelque chose d’extraordinaire. Je m’étais levé, levé entre les morts, entre les larves. […] Tout d’un coup, je me connaissais, je connaissais ma vie. C’était donc ma vie, cet ébat qui n’allait plus s’arrêter jamais »*, écrit-il dans La comédie de Charleroi (1934) qui rassemble, sous forme de nouvelles, ses expériences de la Grande Guerre.

Pierre Drieu la Rochelle n’a éjaculé qu’une seule fois dans sa vie : c’était le 23 août 1914, lors d’une chaude journée de guerre dans la plaine de Charleroi. Ce jour-là, le caporal de 21 ans vit sa première épreuve du feu. Soudain, au milieu de l’affrontement, il se lève, comme s’il n’avait plus peur de la mort, charge son fusil et entraîne plusieurs camarades. L’enivrement que lui procure la sensation d’être devenu le chef qu’il a toujours rêvé d’incarner est comme un orgasme sexuel. « Alors, tout d’un coup, il s’est produit quelque chose d’extraordinaire. Je m’étais levé, levé entre les morts, entre les larves. […] Tout d’un coup, je me connaissais, je connaissais ma vie. C’était donc ma vie, cet ébat qui n’allait plus s’arrêter jamais »*, écrit-il dans La comédie de Charleroi (1934) qui rassemble, sous forme de nouvelles, ses expériences de la Grande Guerre.

Vor

Vor  Doch Dutschke argumentiert dagegen unverblühmt national. Er weiß klug zu differenzieren: „Anlässlich des ungarischen Volksaufstandes von

Doch Dutschke argumentiert dagegen unverblühmt national. Er weiß klug zu differenzieren: „Anlässlich des ungarischen Volksaufstandes von  Sein langjähriger Weggefährte und Freund Bernd Rabehl äußerte überdies schon

Sein langjähriger Weggefährte und Freund Bernd Rabehl äußerte überdies schon  Bei allen nationalen Bekenntnissen Rudi Dutschkes darf jedoch nie vergessen werden, dass er schlussendlich auch für eine antiautoritäre und marxistische Welt eines „Internationalismus“ kämpfte und nicht leichtfertig, gar ausschließlich national interpretiert werden kann. Ihn ohne entsprechende Hinweise als „nationalrevolutionär“ einzuordnen, so wie Henning Eichberg es tat, geht fehl. Dutschke war vieles, aber ein Nationalist im klassischen Sinne definitiv nie. Vielmehr kann Dutschke als Beweis dafür gesehen werden, dass die Kategorien „links“ und „rechts“ schon damals nicht mehr aktuell waren.

Bei allen nationalen Bekenntnissen Rudi Dutschkes darf jedoch nie vergessen werden, dass er schlussendlich auch für eine antiautoritäre und marxistische Welt eines „Internationalismus“ kämpfte und nicht leichtfertig, gar ausschließlich national interpretiert werden kann. Ihn ohne entsprechende Hinweise als „nationalrevolutionär“ einzuordnen, so wie Henning Eichberg es tat, geht fehl. Dutschke war vieles, aber ein Nationalist im klassischen Sinne definitiv nie. Vielmehr kann Dutschke als Beweis dafür gesehen werden, dass die Kategorien „links“ und „rechts“ schon damals nicht mehr aktuell waren.

In this book, George Victor addresses the several questions regarding Pearl Harbor: did U.S. Intelligence know beforehand? Did Roosevelt know? If so, why weren’t commanders in Hawaii notified? It is a well-researched and documented volume, complete with hundreds of end-notes and references.

In this book, George Victor addresses the several questions regarding Pearl Harbor: did U.S. Intelligence know beforehand? Did Roosevelt know? If so, why weren’t commanders in Hawaii notified? It is a well-researched and documented volume, complete with hundreds of end-notes and references.