Robert Steuckers:

Réflexions générales sur l’état de la “démocratie” en Belgique

Conférence prononcée à Louvain, Salle Maria-Theresa, 22 mars 2012

Traduction française du script original néerlandais

A Jean E. van der Taelen (1917-1996), qui a lutté jusqu’à son dernier souffle pour une “démocratie directe et décisionnaire”.

“Qu’est-ce que la démocratie?” et “Qu’est-ce que la démocratie dans l’Etat belge aujourd’hui?” sont les deux questions auxquelles vous m’avez demandé de répondre dans le cadre de cette modeste conférence. Chacun semble savoir ce qu’est la démocratie mais force est de constater que la grande majorité de nos concitoyens, qu’ils soient Flamands, Wallons ou Allemands ne savent pas trop bien comment fonctionnent les mécanismes de l’Etat où ils vivent, Etat qui est théoriquement une “démocratie”.

Cet Etat est né en 1830, je ne vous apprends rien, et a voulu d’emblée se créer comme une démocratie modèle, en imitant paradoxalement certaines effervescences révolutionnaires françaises (plutôt celles de juillet 1830 que celles de 1789) tout en conservant des modes non démocratiques de fonctionnement, émanant du centralisme jacobin et bonapartiste, qui avaient pourtant été maintenus sous le régime du Royaume-Uni des Pays-Bas (1815-1830). Le nouvel Etat belge de 1830 combine de manière quelque peu incohérente des aspirations démocratiques, voire anarchisantes, avec une volonté de se référer à des modèles français tout en s’en défiant (notamment dans les milieux catholiques). La “révolution belge” de 1830 n’est donc pas un phénomène homogène: s’y téléscopent une volonté démocratique et constitutionaliste (que l’on repère surtout dans les pays allemands, en rébellion contre un certain centralisme prussien et contre la volonté anti-révolutionnaire de Metternich), une révolte populaire et anarchique pour le pain à Bruxelles à la fin de l’été 1830, un espoir d’ascension sociale plus rapide chez les catégories de la population qui avaient bénéficié du régime bonapartiste (observable chez les Libéraux de l’époque), un élément réactionnaire catholique qui refuse d’obéir à un Prince protestant de la dynastie des Orange-Nassau (et est prêt à s’allier avec le “diable” libéral pour s’en débarrasser), etc. Ce noeud inextricable de contradictions ira en s’accentuant, connaîtra parfois des périodes de relatif apaisement, pour aboutir au chaos tranquille et à l’indifférence généralisée d’aujourd’hui, face à un pouvoir dont les fondements religieux ou philosophiques et les rouages du fonctionnement apparaissent de plus en plus opaques.

A l’origine du fait belge: des troupes hétéroclites de mercenaires

Le député et historien Karim Van Overmeire a publié récemment, au sein du mouvement flamand, une histoire très fouillée de cette révolution de 1830, en rappelant notamment qu’il a fallu, comme en Syrie aujourd’hui, faire appel à des mercenaires issus des bas-fonds de Paris (la “Légion belge” du faux Marquis Doulcet de Pontécoulant) ou de Londres (les compagnies de Lecharlier) pour conquérir les Flandres, que ces mercenaires pilleront à l’occasion quand les caisses du nouvel Etat ne pouvait pas encore les payer décemment. Parmi ces mercenaires, on trouvait certes des Belges émigrés pour toutes sortes de motifs (relevant généralement du droit commun) mais aussi de nombreux Français, quelques Britanniques ou Irlandais, beaucoup d’Allemands, quelques Italiens et Ibériques. L’évocation de ces mercenaires turbulents est une rengaine du mouvement flamand, me diront sans doute mes lecteurs francophones, soucieux de se démarquer de ce “mouvement flamand” qu’ils craignent, souvent de manière irrationnelle. Cependant, la plus belle histoire de ces troupes a été écrite par Pierre Nothomb, l’arrière-grand-père d’Amélie Nothomb, écrivain en vue aujourd’hui, qui était un défenseur catholique de l’Etat belge, un adversaire des autonomistes flamands et un germanophobe dans la première phase de sa carrière. Dans un recueil de “bons textes”, établi en 1942 et intitulé “Curieux personnages” (éd. “Les Oeuvres”), Pierre Nothomb narre les tribulations de Pierre-Joseph Lecharlier, celui qui a levé les “volontaires belges de Londres” en 1830. Sous-officier du RU des Pays-Bas à Mons en 1817, Lecharlier se fait remarquer pour son inconduite, est ensuite incorporé dans un régiment disciplinaire à Hardenwijck; il déserte, rejoint une compagnie étrangère de l’armée française à Paris puis déserte une nouvelle fois —car il s’ennuie dans l’armée de la Restauration— pour se retrouver à Londres en 1824. Ses biographes sont étrangement silencieux sur ses activités en Angleterre: on chuchote qu’il a été contrebandier. En 1830, il lève des volontaires en Angleterre (mais, parmi eux, aucun Anglais!) et débarque à Bruxelles le 5 octobre, juste après les “journées de septembre”. La troupe de Pontécoulant y est déjà, composée en majorité de Parisiens recrutés dans le “Café belge”, rue Saint-Honoré. Le reste de cette petite armée privée compte des volontaires de toutes les nations. Doulcet de Pontécoulant connaissait la guerre, et même la “petite guerre”, le “Kleinkrieg” des partisans: il devait, au moment de l’effondrement de l’empire napoléonien, commander les francs tireurs de la Haute Saône contre les armées autrichiennes qui venaient de franchir les Vosges alsaciennes (un tableau gigantesque évoque ce passage au Musée militaire de Vienne); mis à pied au retour de Louis XVIII, il sert quelques années dans l’armée brésilienne. D’autres équipes de déclassés et d’aventuriers sont présentes (celles de Coché, Bauwens, Maréchal et Molesini-Sautel), en tout 700 à 900 hommes. Ces hommes s’emparent ensuite de Gand où Bauwens manque d’occire un magistrat de la ville, ce que l’oblige à quitter la troupe avec une trentaine de compagnons qui pillent la Flandre rurale pour subvenir à leurs besoins et pour se constituer une petite cagnotte.

Après les Flandres, l’Algarve

Doulcet de Pontécoulant tentera aussi de conquérir la Flandre Zéelandaise pour dégager l’Escaut et permettre au nouveau royaume en gestation de profiter des avantages du port d’Anvers, toujours tenu par la garnison loyaliste. Ces aventuriers turbulents participent ensuite aux combats de 1831-32 et, une fois la paix revenue, le gouvernement les encourage vivement à s’engager dans une “légion étrangère” portugaise, où se bousculaient déjà, au service du parti des “constitutionnels”, des troupes hétéroclites et hautes en couleur, anglaises, françaises, germaniques et écossaises. Le 6 octobre 1833, les volontaires issus des troupes de Pontécoulant, de Lecharlier et des autres capitaines de fortune qui avaient sévi en Flandre, s’embarquent à Ostende, sous le commandement de Lecharlier, et prennent la direction du Portugal, où des volontaires de toutes nationalités s’étaient déjà rassemblés, dont le Colonel Borso, un Italien de Gènes, le major polonais Urbansky et l’officier de cavalerie anglais Bacon. Lecharlier fera, pour Dona Maria, la Reine constitutionaliste, la conquête de l’Algarve contre les soldats de Don Miguel, posé comme “réactionnaire” et comme “tyran”, parce que partisan de maintenir certains dispositifs de l’ancien régime.

Le 1 mai 1835, le gouvernement intègre dans la nouvelle armée belge les officiers de la troupe de Lecharlier, qui avaient combattu au Portugal, sauf leur chef, jugé trop turbulent et indiscipliné. Lecharlier entreprend des démarches pour se faire intégrer dans l’armée: en vain! Dépité par les refus successifs qu’il encaisse, il quitte l’Europe pour chercher l’aventure en Amérique centrale mais disparaît dans le naufrage de son navire. Nothomb raconte avec lyrisme et grand talent littéraire l’aventure de Lecharlier, tout en laissant bien sous-entendre que le personnage, indubitablement pittoresque, ne convenait pas au bon fonctionnement d’une armée normale dans un Etat qui voulait bien vite acquérir un statut de normalité en Europe et se défaire de sa mauvaise réputation “révolutionnaire”.

Ces anecdotes, peu évoquées, sur les événements de 1830-31, démontrent que l’avènement de la “démocratie” officielle en Belgique ne s’est pas fait avec l’assentiment du gros du peuple, généralement acceptant et peu intéressé à la politique (contrairement à ses voisins français ou allemands) mais 1) par le déclic d’une révolte locale anarchisante sans projet politique défini, uniquement pour le pain, à Bruxelles et 2) par le truchement de troupes aventurières, recrutées dans les bas-fonds de villes étrangères comme Paris, Londres ou Roubaix, comme on recrute aujourd’hui à Molenbeek ou à Schaerbeek des djihadistes qui luttent contre le pouvoir établi en Syrie. L’avènement, dans la violence également et avec les mêmes acteurs, du “constitutionalisme” au Portugal participe du même schéma opératoire: les puissances occidentales, subversives dans leurs fondements, recrutent des déclassés pour forcer des pays limitrophes à adopter des principes de gouvernement semblables aux leurs, pour mettre en selle des régimes prêts à faire leur politique et surtout peu susceptibles de s’allier avec les puissances traditionnelles du coeur du continent.

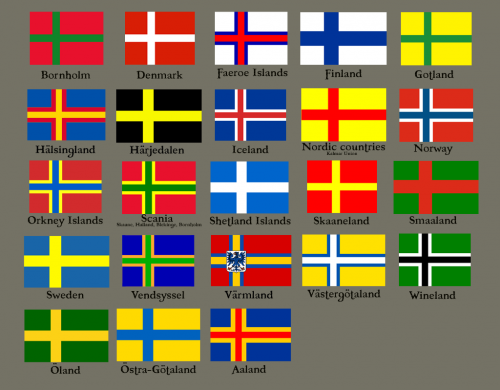

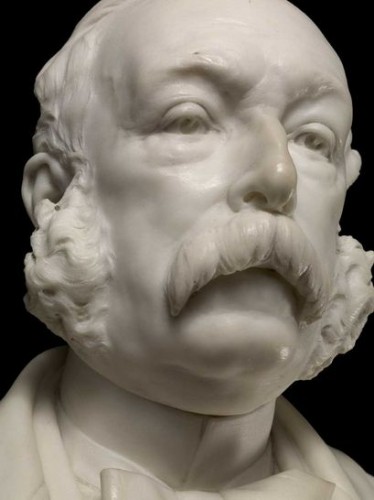

Opposition au système Metternich – L’oeuvre politique d’Ernst Moritz Arndt

Il n’empêche qu’au cours des trois ou quatre premières décennies du 19ème siècle, les peuples d’Europe aspiraient à bénéficier d’une constitution démocratique et voulaient un élargissement du droit de vote aux catégories plus modestes de la population. Les peuples avaient été mobilisés pour faire la guerre contre Napoléon, surtout en Prusse où les bataillons de volontaires de 1813 s’étaient recrutés dans toutes les strates de la population, sans aucune distinction de classe. L’obligation de verser son sang, aux yeux des anciens soldats, devait être compensée par le droit d’intervenir “démocratiquement” dans la formation des gouvernements, des pouvoirs législatifs et exécutifs. Plusieurs petits soulèvements locaux ont ainsi secoué l’Allemagne entre 1825 et 1835: tous portaient, en signe de ralliement, un drapeau rouge-noir-or, symbole de “démocratie” dans les pays germaniques. Ces couleurs ressemblent à celles dites du Brabant, rouge-jaune-noir, utilisées lors de la “révolution” de 1789 contre les réformes éclairées de l’Empereur Joseph II. La différence, de taille, c’est que la révolte anti-joséphienne de 1789 était ultra-réactionnaire, dirigée contre les “Lumières” du despotisme éclairé, et ne comprenait qu’une aile minoritaire libérale, dite “vonckiste”, rapidement mise hors circuit par le déchaînement, dans la rue, d’une violence inouïe. Celle de 1830 a toutes les apparences du libéralisme du début du 19ème, affublé de quelques oripeaux romantiques (la “Muette de Portici”) mais sans l’atout de la politique et de la pensée romantiques, telles que les a décrites un Georges Gusdorf, éminent professeur de l’université de Strasbourg, dans ses multiples volumes consacrés à l’évolution de la pensée du 18ème au 19ème. Et sans la rigueur et la concision de la pensée d’Ernst Moritz Arndt, populiste réclamant une constitution, à la manière des Lumières et du libéralisme du début du 19ème, mais sans la folie révolutionnaire française de vouloir faire table rase de tous les legs du passé ethno-national, enclenchant de la sorte un “processus de dégénérescence” irréversible, faisant basculer les Lumières dans l’ “Ungeist”, le “non-esprit”; en effet, dans son ouvrage “Deutsche Volkwerdung” (= “Le devenir-peuple des Allemands”), il démontre et explique qu’un peuple ne devient peuple que s’il transforme tous ses ressortissants en “zoon politikon” (= “politische Menschen”), ce qui implique d’abjurer les idées et les attitudes réactionnaires qui le minorisent (Kant!), de refuser le cosmopolitisme (expression d’impolitisme dégénéré, déduit d’une coquetterie volontairement inattentive à tout ce qui relève du “hic et nunc”), de refuser avec la même vigueur les pensées mécanicistes et inorganiques (celles de la révolution française qui ne font que laïciser et républicaniser l’absolutisme anti-populaire). Le peuple, en l’occurrence le peuple allemand, ne devient un vrai peuple, à l’instar des Suédois (la Suède est le modèle d’Arndt), donc un peuple politique, que s’il respecte et cultive l’héritage de ses pères, génère une vie artistique qui lui soit propre, adhère aux valeurs héroïques et conserve une vigueur vitale qui en fait en permanence un peuple jeune, challengeur face à toutes les décrépitudes. Enfin, un peuple n’est peuple que si le droit qu’il se donne puise dans les traditions juridiques qui sont les siennes et ne se réfère jamais à des modèles juridiques étrangers (allusion au droit néo-romain du Code Napoléon). Ernst Moritz Arndt était perçu comme un “jacobin”, comme un dangereux révolutionnaire, comme un “démagogue”, par les forces réactionnaires de son époque. On doit plutôt le considérer comme un combattant de la liberté, une liberté qui ne doit rien à la chimère de la “méthodologie individualiste” mais s’inscrit dans le cadre d’un destin collectif, auquel aucun citoyen ne peut se soustraire.

Il n’empêche qu’au cours des trois ou quatre premières décennies du 19ème siècle, les peuples d’Europe aspiraient à bénéficier d’une constitution démocratique et voulaient un élargissement du droit de vote aux catégories plus modestes de la population. Les peuples avaient été mobilisés pour faire la guerre contre Napoléon, surtout en Prusse où les bataillons de volontaires de 1813 s’étaient recrutés dans toutes les strates de la population, sans aucune distinction de classe. L’obligation de verser son sang, aux yeux des anciens soldats, devait être compensée par le droit d’intervenir “démocratiquement” dans la formation des gouvernements, des pouvoirs législatifs et exécutifs. Plusieurs petits soulèvements locaux ont ainsi secoué l’Allemagne entre 1825 et 1835: tous portaient, en signe de ralliement, un drapeau rouge-noir-or, symbole de “démocratie” dans les pays germaniques. Ces couleurs ressemblent à celles dites du Brabant, rouge-jaune-noir, utilisées lors de la “révolution” de 1789 contre les réformes éclairées de l’Empereur Joseph II. La différence, de taille, c’est que la révolte anti-joséphienne de 1789 était ultra-réactionnaire, dirigée contre les “Lumières” du despotisme éclairé, et ne comprenait qu’une aile minoritaire libérale, dite “vonckiste”, rapidement mise hors circuit par le déchaînement, dans la rue, d’une violence inouïe. Celle de 1830 a toutes les apparences du libéralisme du début du 19ème, affublé de quelques oripeaux romantiques (la “Muette de Portici”) mais sans l’atout de la politique et de la pensée romantiques, telles que les a décrites un Georges Gusdorf, éminent professeur de l’université de Strasbourg, dans ses multiples volumes consacrés à l’évolution de la pensée du 18ème au 19ème. Et sans la rigueur et la concision de la pensée d’Ernst Moritz Arndt, populiste réclamant une constitution, à la manière des Lumières et du libéralisme du début du 19ème, mais sans la folie révolutionnaire française de vouloir faire table rase de tous les legs du passé ethno-national, enclenchant de la sorte un “processus de dégénérescence” irréversible, faisant basculer les Lumières dans l’ “Ungeist”, le “non-esprit”; en effet, dans son ouvrage “Deutsche Volkwerdung” (= “Le devenir-peuple des Allemands”), il démontre et explique qu’un peuple ne devient peuple que s’il transforme tous ses ressortissants en “zoon politikon” (= “politische Menschen”), ce qui implique d’abjurer les idées et les attitudes réactionnaires qui le minorisent (Kant!), de refuser le cosmopolitisme (expression d’impolitisme dégénéré, déduit d’une coquetterie volontairement inattentive à tout ce qui relève du “hic et nunc”), de refuser avec la même vigueur les pensées mécanicistes et inorganiques (celles de la révolution française qui ne font que laïciser et républicaniser l’absolutisme anti-populaire). Le peuple, en l’occurrence le peuple allemand, ne devient un vrai peuple, à l’instar des Suédois (la Suède est le modèle d’Arndt), donc un peuple politique, que s’il respecte et cultive l’héritage de ses pères, génère une vie artistique qui lui soit propre, adhère aux valeurs héroïques et conserve une vigueur vitale qui en fait en permanence un peuple jeune, challengeur face à toutes les décrépitudes. Enfin, un peuple n’est peuple que si le droit qu’il se donne puise dans les traditions juridiques qui sont les siennes et ne se réfère jamais à des modèles juridiques étrangers (allusion au droit néo-romain du Code Napoléon). Ernst Moritz Arndt était perçu comme un “jacobin”, comme un dangereux révolutionnaire, comme un “démagogue”, par les forces réactionnaires de son époque. On doit plutôt le considérer comme un combattant de la liberté, une liberté qui ne doit rien à la chimère de la “méthodologie individualiste” mais s’inscrit dans le cadre d’un destin collectif, auquel aucun citoyen ne peut se soustraire.

Les effervescences constitutionalistes en pays allemands

Le cycle révolutionnaire-national-constitutionaliste-démocrate en Europe du Nord commence sans doute le 26 mai 1818, quand le Roi Maximilien-Joseph de Bavière accorde une constitution à ses sujets, assortie d’une représentation bicamérale, avec un sénat composé de représentants de la haute noblesse et une chambre basse, composée de la petite noblesse, de la bourgeoisie et de la paysannerie, ce qui impliquait un élargissement très généreux du cens électoral. Le 22 août de la même année, le Grand-Duc Charles de Bade accorde une constitution encore plus libérale à ses sujets. Le 25 septembre 1819, c’est au tour du Roi Guillaume de Wurtemberg d’octroyer à son peuple une constitution similaire à celles de Bavière et de Bade. Dans le reste des pays allemands, la répression s’organise autour d’une “Commission centrale d’enquête” basée à Mayence et frappe les intellectuels. Metternich fait réaffirmer le “principe monarchique” et cherche à dépouiller les chambres de leurs prérogatives, à les réduire à de simples organes de consultation. Malgré cette pression, le Grand-Duc de Hesse-Darmstadt est contraint d’élargir le cens et de modifier la constitution dans un sens plus démocratique, le 18 mars 1820. Au printemps 1830, fin mars, le Grand-Duché de Bade, avant les soulèvements de Paris et de Bruxelles, évolue vers un libéralisme plus souple encore. En juillet 1830, la France devient une monarchie constitutionnelle. En septembre 1830, comme à Bruxelles, les Brunswickois se révoltent et chassent leur Duc, qu’ils s’étaient mis à haïr. Le 5 janvier 1831, le Prince électeur Guillaume II de Hesse accorde une constitution à ses sujets où le “Landtag” dispose à lui seul du droit de lancer toute initiative d’ordre législatif, de contrôler entièrement le budget et de révoquer les ministres. Le 26 mai 1831, le “Landtag” bavarois oblige le Roi à révoquer le ministre de l’intérieur, Edouard von Schenck. Le 4 septembre 1831, un an après les barricades de Bruxelles, le Roi Antoine de Saxe est contraint d’octroyer à son tour une Constitution. Le 31 décembre 1831, les réformes en pays de Bade prennent de l’ampleur: l’ordonnance réglementant le fonctionnement des communes équivaut presque à autonomiser celles-ci et à politiser de plus larges strates de la population.

Hambach: du constitutionalisme à la révolution

Du 27 au 30 mai 1832 se tiennent les “fêtes nationales” de Hambach, auxquelles participent plus de 30.000 personnes, venues surtout de l’Allemagne du Sud-Ouest, donc de pays bénéficiant déjà d’un régime constitutionnel. Deux délégations étrangères y participent: l’une vient de France, l’autre de Pologne (où la révolte de 1830-31 a été écrasée par les forces prussiennes et russes, garantes de l’ordre voulu par Metternich). Les orateurs réclament cette fois l’abolition du principe monarchique qui maintient, disent-ils, la division de l’Allemagne en petits duchés et principautés. Un république unie, juxtaposée à d’autres républiques nationales en Europe, rassemblerait tous les Allemands en un seul Etat. La “fraternité démocratique” entre les peuples remplacerait la “Sainte Alliance” des empereurs, rois et princes, reposant sur le principe monarchique. Avec Hambach se clot l’ère des revendications constitutionalistes au sein d’Etats, petits ou grands, qui pouvaient rester, dans l’optique des contestataires eux-mêmes, des monarchies. C’est un pas que la “révolution belge”, la “Belgische omwenteling” de Maurits Josson, n’a pas franchi: les révoltés cherchaient un roi... (sur Hambach, cf. Wolfgang Strauss, “Ein Volk, das seine Ketten bricht – 150 Jahre Hambach – Parteienfestival oder revolutionäre Erneuerung?”, in: “Mut”, n°177, Mai 1982).

Les troubles qui ont conduit à l’indépendance belge s’inscrivent donc dans un contexte européen de revendications nationales-constitutionalistes (plutôt que “nationales-libérales”) et de contestation de l’ordre établi au Congrès de Vienne en 1815 sous l’impulsion du Prince Metternich, soucieux de ne plus jamais livrer l’Europe aux “démagogues”. Vu l’analphabétisme assez répandu dans les anciens Pays-Bas autrichiens, après un 17ème et un 18ème sans productions culturelles notables (cf. H. J. Elias, “Geschiedenis van de Vlaams Gedachte”, vol. 1), il n’est pas sûr que le gros de la population des provinces belges cherchait un ordre constitutionnel car une telle vision politique aurait impliqué un taux d’alphabétisation plus élevé, justement comme dans les provinces d’Allemagne du Sud (Bade, Bavière, Wurtemberg), auxquelles les souverains avaient concédé des constitutions, ou, à la limite, comme dans l’ex-Duché du Luxembourg, inféodé au Royaume-Uni des Pays-Bas (RUPB), seule région où l’alphabétisation était largement répandue à l’époque. Le RUPB disposait certes d’une constitution, la ‘Grondwet”, mais la volonté royale de moderniser les deux composantes du pays était perçue comme “anti-démocratique” par les libéraux francophiles et post-bonapartistes et par les catholiques, hostiles à toute immixtion royale-protestante dans les affaires scolaires et religieuses des ex-Pays-Bas autrichiens. Les libéraux, majoritairement francophones et culturellement tournés vers la France, contestaient la politique linguistique du Roi Guillaume des Pays-Bas, qui accordait une place prépondérante au néerlandais. Les catholiques voulaient un Etat majoritairement catholique, ce qu’il était, mais cette majorité catholique devait —à leurs yeux et à une époque marquée par l’ultramontanisme— s’imposer sans le moindre partage, être libérée de toute présence protestante-calviniste (et accessoirement de toute influence libérale trop prépondérante). Les catholiques de 1830 se retrouvent plus ou moins sur la même ligne que les révoltés de 1789, les “Statistes” fédéralistes, harangués par un fanatique religieux, le chanoine van Eupen. Les autres, les libéraux francophiles, souvent issus du fonctionnariat napoléonien, veulent s’aligner sur des modèles français, parfois dans l’espoir d’une annexion ultérieure, ou, du moins, espèrent l’avènement d’une monarchie constitutionnelle similaire à celle de la France de Louis-Philippe. Ces deux forces dominantes, après avoir liquidé par corruption la révolte prolétarienne pour le pain à Bruxelles (cf. les travaux de Maurice Bologne), vont donner le ton: les influences diffuses des nationaux-constitutionalistes allemands réémergeront, de manière seulement fragmentaire, dans deux filons contestataires du 19ème siècle (et partiellement du 20ème), le mouvement flamand émergent et les libéraux dits de “gauche” (dont une fraction, allié à d’autres forces situées plus à “gauche”, donnera ensuite naissance au pilier socialiste). Ces deux mouvements militeront notamment pour une alphabétisation générale dans la langue du peuple.

Les avatars du drapeau

L’histoire du drapeau belge témoigne des atermoiements entre factions différentes: quand des mercenaires français hissent le drapeau tricolore bleu-blanc-rouge sur l’Hôtel de Ville de Bruxelles, celui-ci est aussitôt arraché par la garde urbaine, placée à ce moment-là des événements sous la direction de Ducpétiaux et Jottrand, et remplacé par un drapeau rouge-jaune-noir, considéré comme “brabançon”: dans ces couleurs se mêlent le souvenir (sans doute fort diffus et ténu en 1830) des événements de 1789 et une vague adhésion au démocratisme constitutionaliste des pays d’Allemagne du Sud. Au départ, les couleurs sont disposées horizontalement, comme le drapeau de la “révolution brabançonne” de 1789 et comme l’étendard de ralliement des démocrates allemands de l’ère de la Restauration. Les couleurs seront ensuite placées en position verticale, par une sorte de compromis: on ne veut pas du jacobinisme français, forme laïque et révolutionnaire d’absolutisme, mais on ne veut pas davantage du démocratisme allemand; on est constitutionaliste, soit en faveur d’une monarchie constitutionnelle, mais on n’est pas nationaliste: ni à la manière de la bourgeoisie louis-philipparde (cf. Heinz-Gerhard Haupt, “Nationalismus und Demokratie – Zur Geschichte der Bourgeoisie im Frankreich der Restauration”, Europäische Verlagsanstalt, Frankfurt am Main, 1980) ni à la manière des révolutionnaires nationaux-démocratiques qui ont défilé lors des “fêtes” de Hambach en 1832. Ce premier compromis à la belge est symbolisé par les avatars successifs du drapeau du nouvel Etat: couleurs verticales pour montrer que l’on ne va pas trop loin dans la révolte (Gendebien sur le soulèvement prolétarien de Bruxelles: “Une mauvaise farce d’écoliers”), que l’on maintient une partie du fonctionnariat bonapartiste (resté en place à l’époque du RUPB et noyau dur du libéralisme maçonnique belge), que l’on conserve le droit romain à la sauce Bonaparte et que l’on ne revient pas aux traditions juridiques des Flandres et du Brabant (ce qu’un Arndt aurait demandé...), que l’on permet au Roi d’exercer certaines prérogatives d’ancien régime mais que l’on reste néanmoins dans la tradition constitutionaliste. Ce système sera même un modèle pour les députés de l’éphémère parlement de Francfort de 1848: pour l’Allemagne unie, ils ont voulu un régime de monarchie constitutionnelle à la belge voire le Roi Léopold I comme nouvel empereur constitutionnel!

Un noeud gordien que l’on ne peut plus trancher

Le noeud de contradictions demeure irrésolu après l’indépendance de la Belgique et ne peut être tranché (ne sera jamais tranché), à la manière d’Alexandre, parce qu’il n’existe pas de culture politique commune à tous, ni aux communautés linguistiques ni aux factions qui divisent et le pays et chacune de ces communautés, et que les tentatives littéraires de forger un esprit national se sont heurtées à l’indifférence d’une bourgeoisie dominante mais matérialiste et, partant, totalement inculte (cf. le désintérêt pour l’oeuvre de Charles Decoster puis pour les réalisations architecturales de Victor Horta et de son équipe, édifices que l’on commençait déjà à détruire du vivant de l’architecte parce qu’on ne les trouvait pas assez “utiles”!!). La révolte des “libéraux de gauche”, et l’abnégation admirable de jeunes instituteurs cherchant à alphabétiser les masses, notamment à Bruxelles, permettront certes de développer, tardivement, une politique scolaire digne d’un Etat moderne, mais une politique qui se heurtera de manière récurrente à un matérialisme borné et tenace, à des sectarismes totalement anachroniques, à une haine féroce contre tout ce qui relève de la culture humaniste, hier moquée par les “réalistes”, par les suffisants qui qualifiaient les matières scolaires relevant de la culture générale, comme la géographie ou l’histoire, ou des humanités classiques —le grec et le latin— d’inutilités (“ça sert à rien”); aujourd’hui culture générale et joyaux misérablement résiduaires de l’éducation classique sont noyées dans un festivisme hostile à toute qualité et dans un relativisme “interculturel” qui nous fait sombrer dans la barbarie la plus obscurantiste (pour saisir de manière poignante ce que fut l’apostolat de jeunes instituteurs flamands et laïques à Bruxelles au 19ème, lire: Eliane Gubin, “Bruxelles au XIXe siècle: berceau d’un flamingantisme démocratique, 1840-1873”, Crédit communal de Belgique, Coll. “Histoire Pro Civitate”, n°56, 1979).

Pour expliquer l’évolution des “choses démocratiques” dans l’espace devenu belge après la scission du RUPB, il faut rappeler certains principes de la Constitution de ce royaume qui, uni, n’a duré que quinze ans. Cette constitution fonctionnait avec un “peuple-électeur” quantitativement très limité. Cependant certaines dispositions de cette “loi fondamentale” étaient peut-être plus démocratiques que les dispositions actuelles: ainsi, les élections communales avaient lieu tous les six ans, comme aujourd’hui, mais la constitution, jusqu’au début de l’histoire belge proprement dite, prévoyait le renouvellement d’un tiers du collège tous les deux ans, permettant un contrôle plus étroit des mandataires et l’élimination des farceurs et des “bras cassés”, ce qui n’est plus possible aujourd’hui. L’élargissement du cens électoral n’a pas permis de pérenniser ce système plus démocratique: impossible, budgétairement parlant, de réorganiser des élections tous les deux ans dans chacune des communes du royaume. Comment la situation a-t-elle dès lors évolué? L’évolution ultérieure s’explique par des motifs nombreux et divers, qu’il est impossible d’évoquer, même succinctement, dans le cadre de cette causerie. La révolution industrielle, qui prend son envol en Belgique plus rapidement que dans d’autres régions d’Europe continentale, Allemagne comprise, génère un prolétariat déraciné (exode des campagnes vers les villes) et privé de droits politiques. En marge du parti libéral d’abord, dans certains cénacles ultramontains (hostiles au manchestérisme industriel et capitaliste) puis, enfin, dans le parti socialiste, le prolétariat urbain va réclamer un élargissement du cens électoral pour pouvoir voter ou faire voter des lois qui puissent améliorer son sort. Ces revendications seront toujours assorties d’une volonté de conquérir le suffrage universel, “pur et simple” et non pas “universel, capacitaire et familial”. Mais l’augmentation du nombre des électeurs fait qu’il devient impossible de procéder à des élections intermédiaires, tous les deux ans, pour renouveler, le cas échéant, le tiers des conseils communaux, ou de procéder de manière analogue pour les autres assemblées. Paradoxalement, l’idée du suffrage élargi puis universel permet un contrôle démocratique moindre que certains aspects du suffrage censitaire... Une contradiction à laquelle plus personne ne réfléchit sérieusement...

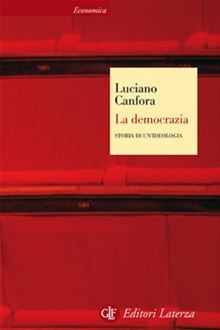

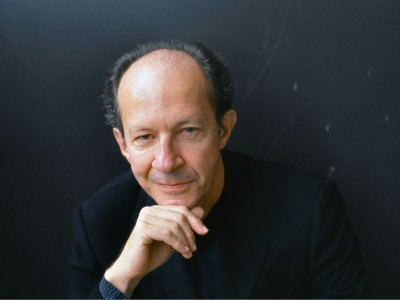

Luciano Canfora et le paradoxe de Condorcet

La question du suffrage universel est abordée dans un ouvrage de référence fort bien charpenté du professeur italien Luciano Canfora, intitulé “La democrazia – Storia di un’ideologia” (Ed. Laterza, Roma/Bari, 2004, 3ième éd., 2010). Le Prof. Canfora enseigne la philologie classique à l’Université de Bari et est le directeur de la revue “Quaderni di storia”: à ce titre, il plonge sans cesse dans les archétypes les plus fructueux de nos héritages grecs et latins et s’immerge, armé de cette formidable panoplie intellectuelle, dans le flux du réel contemporain. Dans “La democrazia”, Canfora explique que la revendication du suffrage universel s’est déployée, dans l’histoire européenne, en trois étapes: 1) lors de la révolution française, 2) à la fin de la II° République en France (et donne un pouvoir personnel et césarien au futur Napoléon III), 3) immédiatement après l’effondrement du tsarisme en Russie, pour donner le pouvoir aux commissaires bolcheviques puis, en Allemagne, après la parenthèse de la République de Weimar, à la NSDAP. Pour Canfora, le suffrage universel, bien que nécessaire à la démocratie, est aussi, simultanément, l’instrument qui l’annulle face à des événements forts, exigeant des prises de décision plus rapides. Canfora explique le mécanisme d’annulation démocratique en se référant à un texte de Condorcet, écrit en 1785, le trop peu connu “Essai sur l’application de l’analyse à la probabilité des décisions rendues à la pluralité des voix”. Dans cet essai, qui précède la révolution française de quatre petites années seulement, Condorcet démontre que, s’il y a plus de deux choix, il est impossible d’obtenir un résultat politique cohérent, c’est-à-dire, “d’étendre la transitivité des préférences individuelles aux préférences sociales”. Ainsi, prenons trois électeurs, Messieurs X, Y et Z. La transitivité s’opère aisément si tous votent, par exemple, comme Monsieur X, qui préfère le parti A au parti B, et le parti B au parti C. Mais si X choisit cet ordre ABC tandis qu’Y préfère l’ordre BCA et Z, l’ordre CAB, aucune transitivité parfaite n’est possible: le résultat électoral, traduit en sièges, ne reflètera en aucun cas les opinions ou desiderata de tous les citoyens. C’est là le “noeud gordien” qu’il nous est désormais impossible à trancher selon des procédés démocratiques, sauf à recourir à une nouvelle mouture du césarisme de Napoléon III, aux commissaires bolcheviques (but du nouveau PTB?) ou à un système de parti unique avec chef incontesté, comme l’était la NSDAP allemande.

La question du suffrage universel est abordée dans un ouvrage de référence fort bien charpenté du professeur italien Luciano Canfora, intitulé “La democrazia – Storia di un’ideologia” (Ed. Laterza, Roma/Bari, 2004, 3ième éd., 2010). Le Prof. Canfora enseigne la philologie classique à l’Université de Bari et est le directeur de la revue “Quaderni di storia”: à ce titre, il plonge sans cesse dans les archétypes les plus fructueux de nos héritages grecs et latins et s’immerge, armé de cette formidable panoplie intellectuelle, dans le flux du réel contemporain. Dans “La democrazia”, Canfora explique que la revendication du suffrage universel s’est déployée, dans l’histoire européenne, en trois étapes: 1) lors de la révolution française, 2) à la fin de la II° République en France (et donne un pouvoir personnel et césarien au futur Napoléon III), 3) immédiatement après l’effondrement du tsarisme en Russie, pour donner le pouvoir aux commissaires bolcheviques puis, en Allemagne, après la parenthèse de la République de Weimar, à la NSDAP. Pour Canfora, le suffrage universel, bien que nécessaire à la démocratie, est aussi, simultanément, l’instrument qui l’annulle face à des événements forts, exigeant des prises de décision plus rapides. Canfora explique le mécanisme d’annulation démocratique en se référant à un texte de Condorcet, écrit en 1785, le trop peu connu “Essai sur l’application de l’analyse à la probabilité des décisions rendues à la pluralité des voix”. Dans cet essai, qui précède la révolution française de quatre petites années seulement, Condorcet démontre que, s’il y a plus de deux choix, il est impossible d’obtenir un résultat politique cohérent, c’est-à-dire, “d’étendre la transitivité des préférences individuelles aux préférences sociales”. Ainsi, prenons trois électeurs, Messieurs X, Y et Z. La transitivité s’opère aisément si tous votent, par exemple, comme Monsieur X, qui préfère le parti A au parti B, et le parti B au parti C. Mais si X choisit cet ordre ABC tandis qu’Y préfère l’ordre BCA et Z, l’ordre CAB, aucune transitivité parfaite n’est possible: le résultat électoral, traduit en sièges, ne reflètera en aucun cas les opinions ou desiderata de tous les citoyens. C’est là le “noeud gordien” qu’il nous est désormais impossible à trancher selon des procédés démocratiques, sauf à recourir à une nouvelle mouture du césarisme de Napoléon III, aux commissaires bolcheviques (but du nouveau PTB?) ou à un système de parti unique avec chef incontesté, comme l’était la NSDAP allemande.

Le socialisme: de la volonté de bâtir une “autre société” à la barbarie et l’inculture

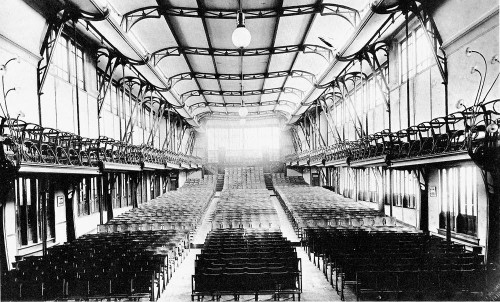

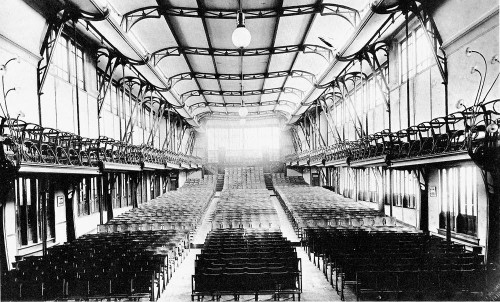

La longue marche des socialistes belges vers le pouvoir fait émerger un phénomène typiquement belge (et néerlandais), celui dit de la “pillarisation”, soit l’émergence de ce que les politologues néerlandophones nomment les “zuilen” ou ‘”piliers” de la société. Ces “zuilen” sont constituée par l’ensemble des organisations, associations, etc. qui gravitent autour des trois principaux partis du royaume, les catholiques (bénéficiant d’un antécédant vu l’organisation des paroisses), les libéraux (dont le “pilier” sera toujours moins lourd que les autres) et les socialistes (qui construiront leur pilier pour le rendre presque aussi efficace que celui des catholiques, ou plus efficace encore, dans les régions les plus industrialisées de la Wallonie). Au début de son histoire, le “pilier” socialiste propose ainsi une “autre société”, démarche qui s’exprime partiellement par le mouvement “art nouveau”, avec un Horta qui édifie une “Maison du Peuple” extraordinaire (que les socialistes ultérieurs s’empresseront de faire démolir, preuve la plus emblématique de la barbarie et de l’inculture dans lesquelles ce “pilier” a chaviré!) et par la volonté de créer des écoles, à la suite des pétitions demeurées sans succés des libéraux populistes, soucieux du maintien de la culture: leurs aspirations, leurs démarches, leurs organisations modestes (mais admirables) sont désormais un phénomène politique définitivement disparu. Le flamingantisme premier est issu de ce libéralisme populaire, parfois orangiste et plus rarement bismarckien, surtout à Bruxelles.

La Maison du Peuple de Bruxelles, oeuvre d'Horta, détruit par les socialistes à la fin des années 50

Après l’effondrement du système scolaire efficace et bien conçu, mis en place par le Roi Guillaume I des Pays-Bas Unis, après la dispariton des lois scolaires du RUPB, l’Etat belge, à ses origines, est un exemple de barbarie effroyable: il n’y a plus, dans ce royaume, de système scolaire digne de ce nom, comme l’explique l’historienne liégeoise Eliane Gubin, spécialiste du flamingantisme démocratique bruxellois du 19ème siècle (cf. également le chapitre consacré à l’analphabétisme, résultat des “révolutions française et industrielle” dans le livre du Prof. Dr. Fernand Lehouck, “Van apathie tot strijdbaarheid – Schets van een geschiedenis van de Belgische vakbeweging 1830-1914”, Orion, Brugge, 1980; le Prof. Lehouck rappelle notamment l’enquête Ducpétiaux de 1843 où 648 ouvriers et ouvrières sur 1000 étaient totalement analphabètes; à Bruges en 1886, 19.179 habitants sur 47.497 demeuraient analphabètes; entre 1868 et 1886, entre 5,6% et 7,8% des enfants en âge d’école primaire fréquentaient les écoles gratuites). Sans écoles bien organisées, il n’y a pas de transmission possible: ce qui explique l’état d’amnésie dans lequel le “machin Belgique” a toujours végété, avec seulement quelques lueurs passagères, comme la volonté de créer une littérature “racique” avec Decoster et Lemonnier, l’émergence du “mythe bourguignon” (Hommel, Colin), le souvenir de Charles-Quint dans des cercles académiques restreints (De Boom, Géoris, Blockmans, Verbrugge, etc.), les tentatives un peu simplistes de Jo Gérard, les efforts des historiens de la littérature (Aron, Quaghebeur, Klinkenberg, Joiret, etc, flanqués des Canadiens Biron et Grutman) dans un milieu qui hélas, lui aussi, n’est qu’académique: rien n’est fait pour insuffler au grand public un sens de l’histoire conforme aux époques les plus sublimes du passé d’entre-Somme-et-Rhin. La preuve? On a supprimé les subsides pour l’un des deux défilés annuels de l’Ommegang (souvenir sublime de Charles-Quint et hommage poignant au principe impérial) pour les affecter à la “Gay Pride” et à la “Zinneken Parade”. Le spectacle n’est plus diffus, comme le disait Guy Debord à propos des démocraties occidentales, il est à nouveau visibilisé et outrancier, comme dans les fascismes, nazismes et autres stalinismes nord-coréens... mais sans bottes ni baudriers ni pas de l’oie. On s’y tortille le cul au rythme des sambas les plus lascives, fessards flasques impudiquement recouverts d’un simple string. On a mieux depuis 2012: les “femens”, dont les charmants gargamels sont maculés de slogans hideux, badigeonnés sans le moindre effort calligraphique, ce qui fait, hélas oublier la Vénus de Milo ou les sculptures de Praxitèle et ôte toute d’envie d’aller les poutouner, dans un grand élan coquin et rabelaisien.

“Autres Lumières” et Kulturstaat

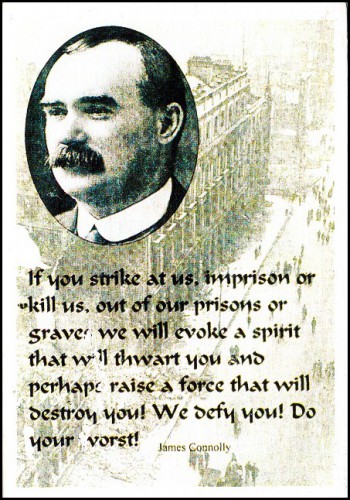

Revenons au 19ème siècle. La reconstitution d’écoles a donc relévé du pur apostolat, de l’abnégation et du dévouement de personnes privées, qui n’ont reçu aucun soutien des autorités en place. Cette posture anti-scolaire, cette attitude de barbarie moderne qu’incarnait le nouvel Etat, né suite aux brutalités des mercenaires recrutés dans les bas-fonds de Londres et de Paris, explique le sentiment anti-belge qui perdurera chez les intellectuels, à commencer par ces instituteurs jeunes et volontaires, idéalistes au sens le plus pur du terme. Ici, il est bon, me semble-t-il, de faire une petite digression, amorce d’une causerie future: un Etat véritablement “démocratique”, au sens que lui aurait donné un philosophe des “autres Lumières” comme Herder, ne devrait-il pas être le “Kulturstaat”, soit l’Etat qui met la préservation de la culture au-dessus de toute autre considération? Ne faut-il pas souhaiter un Etat porté par un idée organique et généreuse (classée à ce titre à gauche de l’échiquier politique!) comme celle théorisée au 19ème par le Norvégien Johan Ernst Sars (cf. Bernhard P. Falk, “Geschichtsschreibung und nationale Ideologie - Der norwegische Historiker J. E. Sars”, Carl Winter Verlag, Heidelberg, 1991)? Cette idée est présente dans bons nombres d’esprits en Allemagne mais n’a jamais trouvé de concrétisation dans les pays germaniques continentaux (en Scandinavie, notamment par l’impact d’un Sars, les choses sont moins dramatiques, la notion d’enracinement est toujours palpable et résiste tant bien que mal à tous les assauts des forces porteuses du déclin irrémédiable de la culture européenne). Elle est très présente toutefois dans le socialisme (Connolly) et le nationalisme (Davis, Pearse) irlandais: même après le second conflit mondial, le Président Eamon de Valera et son ministre Sean MacBride ont répété très souvent, dans les congrès dits “panceltiques” ou à la tribune d’instances internationales, que la mission de l’Irlande dans le monde était de défendre les héritages culturels, garants de l’équilibre international, garants aussi du bonheur des peuples, qui pourront ainsi être en accord avec leur “coeur profond”. Mieux: le recteur de l’Université de Dublin a le droit d’opposer son veto aux lois votées par le Parlement, si ces lois lui semblent des aberrations, imaginées par des échaudés ou des têtes brûlées comme les petits mondes politiciens en produisent tant. Des modèles à méditer.

Paul Belien et le “coup de Loppem ”

Pour un polémiste de la trempe de Paul Belien, la Belgique “pilarisée” d’aujourd’hui a trouvé sa forme en 1919, à la suite du “compromis de Loppem ”, ou “coup de Loppem ”, diront à l’époque les catholiques, pourtant unitaristes et royalistes. Dans le château de Loppem, près de Bruges, les chefs de file des partis libéral, socialiste et catholique, flanqués des représentants du patronat et de la classe ouvrière, décident d’un nouvel agencement de la vie politique du royaume, avec l’approbation du Roi Albert I, soucieux d’éviter tous conflits sociaux et toute contagion par contact avec les “conseils” des soldats allemands révolutionnaires qui avaient fraternisé avec les travailleurs belges dans les villes industrielles (notamment à Liège) en 1918, situation analogue à celle qui avait animé les rues de Strasbourg avant le retour des armées françaises: sur le palais de justice de la métropole alsacienne, on peut toujours, aujourd’hui, apercevoir les impacts des balles et des obus légers, tirés par les Français pour en déloger les “spartakistes” des conseils d’ouvriers et de soldats et leurs alliés locaux. Le Roi craignait aussi la fusion du socialisme révolutionnaire (voire du communisme) avec le nationalisme flamand, parfaitement envisageable en cette période de chaotisation totale des sociétés européennes. Les soldats flamands n’avaient-ils pas crié à l’adresse des officiers français en visite sur le front de l’Yser: “A bas la France! Vivent les Soviets! Vivent les Boches! Vive Lénine! Vive le Kaiser! Vive la Révolution!” (cf. les travaux du Prof. Guido Provoost). Le Roi avait profité de cette “aubaine” pour éviter toute inféodation de l’armée belge au commandement suprême allié, toujours prompt à lancer des offensives inconsidérées et très sanglantes: un Roi demeure soucieux du sang de ses sujets; une république à la française s’en soucie comme d’un guigne! Si le souci du Roi était louable pendant les hostilités, où il souhaitait épargner le sang de ses soldats et demeurer un “belligérant” mais non un “allié” de l’Entente (il n’a prêté de soldats qu’au Tsar), ses craintes de 1919, quand il pensait qu’une révolution était imminente, ont conduit à l’adoption d’un système figé, celui du “coup de Loppem”, qui n’autorise quasiment plus de renouvellement des élites par voie électorale, le suffrage universel pur et simple, voulu par les socialistes, s’avérant plus “bloquant” que les autres formes de suffrage. Si le bourgeois borné et affairiste vote sans cesse pour les mêmes programmes conservateurs de ses avantages, les masses prolétarisées, maintenues analphabètes et manipulées à tire-larigot, votent également pour les mêmes démagogues: le vote des vraies élites culturelles, qui détiennent la longue mémoire, est noyé dans un magma démagogique qui est toujours conservateur et jamais rénovateur ou innovateur. C’est là, sans nul doute, sur le long terme, un effet “hétérotélique” (Jules Monnerot).

Depuis 1919, le système de Loppem barre encore et toujours la route aux challengeurs de la troïka libérale/socialiste/démocrate-chrétienne, en utilisant des méthodes qui ne sont guère reluisantes (et dont se sont servi allègrement les ignares et les pignoufs de la “Sureté de l’Etat”, analphabètes bornés et sans nuances comme le sont les Dupont-Dupond d’Hergé). Dans le pilier catholique, pourtant sûr de faire toujours partie de la troïka vu ses scores impressionnants, des voix se sont élevées pour dénoncer ce partage du pouvoir à trois, surtout qu’il rendait possible, par le suffrage universel pur et simple, introduit après la première conflagration mondiale du 20ème siècle, des tandems catholiques/socialistes (perçus par les critiques catholiques rangés derrière le Cardinal Mercier, d’obédience maurrassienne, comme des aberrations) ou, pire, des majorités libérales/socialistes, portées en coulisses par des ennemis de l’Eglise et du catholicisme. Ces voix étaient plus conservatrices que démocrates-chrétiennes: elles tenteront de se maintenir dans les majorités gouvernementales, même composées avec les socialistes; certains de ces conservateurs —parfois conservateurs de valeurs anciennes et non modernes, tout en étant de vigoureux militants ouvriéristes n’ayant aucune leçon de progressisme social à recevoir des gauches— auront des tentations rexistes mais le rexisme sera très rapidement évincé, après son éphémère succès électoral de 1936.

Absence navrante de références italiennes

Belien a donc raison d’incriminer le “compromis de Loppem”, comme étant un dispositif destiné à geler toute circulation des élites, à tuer dans l’oeuf toute émergence de nouvelles donnes (en dépit des concessions accordées, par la force des choses, à la Volksunie de Schilz et au FDF de Lagasse dans les années 70). Il campe dès lors le système belge comme “non démocratique”, puisqu’il ne laisse aucune tribune d’expression politique dans les assemblées législatives aux forces politiques challengeuses (surtout flamandes et dès lors majoritaires aux niveaux régional et communautaire de la Flandre), pour lesquelles on fabrique des “cordons sanitaires”; Belien a toutefois la naïveté d’en appeler sans cesse au monde anglo-saxon (une bonne partie de son oeuvre livresque et journalistique est rédigée en anglais), pour qu’il aide la Flandre à trouver une “bonne gouvernance”, selon les théories se voulant “démocratiques” qui sont énoncées dans le monde intellectuel britannique ou américain. Belien oublie cependant que, pendant la première guerre mondiale, des lois d’exception, des décrets circonvenant les parlements, ont été adoptés chez tous les belligérants, y compris chez les Anglo-Saxons, et que ce mode de “gouvernance” s’est maintenu en temps de paix, jusqu’à nos jours. Belien, comme, hélas, beaucoup d’intellectuels flamands, ne s’est jamais mis à l’écoute du monde intellectuel italien, dont les productions, innombrables, étudient avec toute la rigueur académique voulue comment circonvenir des partitocraties figées, comme celles qui ont corrompu l’Italie depuis son émergence tardive en tant qu’Etat unitaire sur la scène européenne et comme celle qui sévit en Belgique depuis 1919. Cette habilité à miner le pouvoir des “conformistes” et des “établis” en tous genres a donné successivement l’éclectisme mussolinien, le qualunquisme d’après 1945, et après les “années de plomb” et de répression orchestrée contre toutes les forces challengeuses, l’opération “mani pulite” des années 90 et l’arrivée au pouvoir de trois forces non conventionnelles, la Lega Nord d’Umberto Bossi, l’Alliance Nationale de Gianfranco Fini et “Forza Italia” de Silvio Berlusconi, même si ces deux dernières formations ont sombré dans un conformisme nouveau au bout de quelques mois à peine... Cette habilité explique aussi deux phénomènes relativement neufs: 1) l’apparition à Rome, puis dans toutes les autres villes italiennes, du mouvement “Casa Pound”, classé plutôt à tort qu’à raison dans le sillage du “néo-fascisme” et 2) l’émergence de Beppe Grillo et de son mouvement “va-fanculo” (ce que l’on a bien envie de dire, même en liégeois —“vas’ti fére arrêdjî”— aux di Rupo, Verhofstadt, Decroo, Onkelinks, Dehaene entre autres sinistres personnages).

Belien ne s’est donc pas branché sur les débats italiens, bien plus utiles à son “mouvement flamand” que les pesanteurs ou les simplismes du gourou de Margaret Thatcher, le philosophe moraliste Oakshott (dont Verhofstadt, le nouveau copain de Cohn-Bendit dans les coulisses du Parlement Européen, s’entichait, à l’époque où les vieux syndicalistes gantois, véreux et corrompus, le traitaient de “gamin de merde” – “dââ joeng”), bien plus utiles aussi que les théories des Chicago Boys, que les travestissements boiteux de la pensée de Friedrich von Hayek par le “common sense” des “shopkeepers” presbytériens ou méthodistes, que la pensée “ras-des-pâquerettes” du Tea Party ou que les lapalissades des paléo-conservateurs à la Sarah Palin ou que les conneries retentissantes des “télé-évangélistes”, pour ne pas évoquer le bellicisme outrancier et intransposable des néo-conservateurs (vieux trostskistes recyclés suite au reaganisme). Tout ce fourbi, issu de pensées qui n’ont ni la profondeur ni la richesse des traditions philosophiques continentales (surtout allemandes), n’est pas importable; s’y intéresser ou s’en revendiquer, équivaut à produire du pilpoul, à faire le malin, à se soustraire à toute concrétude, à se vautrer dans l’impolitisme, aurait dit Julien Freund. Par conséquent, on peut tranquillement émettre l’hypothèse que le dissident Belien, très content de maîtriser la langue de Shakespaere de la manière la plus parfaite qui soit, n’a sans doute jamais ouvert un livre de Giorgio Agamben, philosophe de réputation internationale, à la pensée pointue et à l’écriture agile, dont la hauteur de vue permet de consolider des arguments plus basiques, même si l’on n’est pas d’accord avec toutes les conclusions philosophiques de cet auteur, professeur d’esthétique auprès de l’Institut universitaire d’architecture de Venise.

Giorgio Agamben et la notion d’“état d’exception”

Dans “Stato di eccezione” (Bollati Boringhieri, Turin, 2003), Giorgio Agamben souligne d’emblée que les démocraties en général, celles que l’on considère comme étant de “bonne gouvernance” dans le langage des pontes du “politiquement correct”, gouvernent très souvent par le truchement de “pleins pouvoirs”, accordant à l’exécutif la possibilité, euphémiquement posée comme “exceptionnelle”, de réglementer totalement la vie politique d’un pays, de se doter d’un arsenal législatif très ample, surtout quand ces “pleins pouvoirs” permettent de modifier ou d’abroger des lois en vigueur. Agamben se réfère à H. Tingsten et à son livre “Les pleins pouvoirs. L’expansion de pouvoirs gouvernementaux pendant et après la Grande Guerre” (Stock, Paris, 1934). L’exercice sans mesure de “pleins pouvoirs” a éliminé le mode de fonctionnement démocratique, y compris dans les “démocraties” qui se revendiquent comme telles. Tingsten, et à sa suite, Agamben, rappellent que Poincaré émet le 2 août 1914 un décret mettant l’ensemble du territoire français en état de siège, décret coulé en loi deux jours plus tard. Cet état de siège durera jusqu’au 12 octobre 1919, nonobstant le fait que les activités du Parlement aient repris leur cours normal en janvier 1915. Le pouvoir législatif français de 1914 a ainsi délégué une bonne partie de ses prérogatives et compétences à l’exécutif, ce qu’illustre de manière encore plus patente le vote du 10 février 1918 qui accorde au gouvernement des pouvoirs absolus: il pouvait dorénavant réglementer par décrets la production et le commerce des denrées alimentaires. L’exécutif devient ainsi le législatif, ce qui constitue une entorse flagrante au principe de la séparation des pouvoirs, théorisé au 18ème siècle par Montesquieu, un principe qui doit être, de nos jours, l’indice, pour les tenants du “politiquement correct”, d’une “bonne gouvernance”, du moins en théorie, car les représentants du “politiquement correct” ne sont pas prêts à laisser des libertés parlementaires à ceux qui pourraient contredire, même partiellement, leurs dogmes et leurs lubies. La fin des hostilités, le 11 novembre 1918, ne met pas un terme à ces pratiques: en 1924, le gouvernement Poincaré reçoit du Parlement les pleins pouvoirs en matières financières, suite à une crise grave qui ébranle le franc. En 1935, le gouvernement Laval énonce cinquante-cinq décrets “ayant force de loi” pour éviter la dévaluation du franc. L’opposition de gauche rejette certes ces mesures déclarées “fascistes” mais, aussitôt arrivé aux affaires par les urnes, Blum, le chef de file des gauches, recourt aux mêmes expédients: en juin 1937, il demande à son tour les pleins pouvoirs au Parlement pour sauver le franc. Les mesures d’exception, parfaitement compréhensibles en tant de guerre, ne cessent donc pas d’être appliquées, une fois la paix revenue mais, question légitime, est-ce une vraie paix? Ou est-ce la guerre qui continue par d’autres moyens? Ne vivons-nous pas, depuis août 1914, dans une ère de guerre totale et permanente, qui n’emploie pas toujours des moyens militaires pour arriver à ses fins ou porter préjudice aux ennemis? Gouverner un pays, théoriquement “démocratique”, par décrets devient donc la normalité, y compris dans les nations dites “libérales”.

Dans “Stato di eccezione” (Bollati Boringhieri, Turin, 2003), Giorgio Agamben souligne d’emblée que les démocraties en général, celles que l’on considère comme étant de “bonne gouvernance” dans le langage des pontes du “politiquement correct”, gouvernent très souvent par le truchement de “pleins pouvoirs”, accordant à l’exécutif la possibilité, euphémiquement posée comme “exceptionnelle”, de réglementer totalement la vie politique d’un pays, de se doter d’un arsenal législatif très ample, surtout quand ces “pleins pouvoirs” permettent de modifier ou d’abroger des lois en vigueur. Agamben se réfère à H. Tingsten et à son livre “Les pleins pouvoirs. L’expansion de pouvoirs gouvernementaux pendant et après la Grande Guerre” (Stock, Paris, 1934). L’exercice sans mesure de “pleins pouvoirs” a éliminé le mode de fonctionnement démocratique, y compris dans les “démocraties” qui se revendiquent comme telles. Tingsten, et à sa suite, Agamben, rappellent que Poincaré émet le 2 août 1914 un décret mettant l’ensemble du territoire français en état de siège, décret coulé en loi deux jours plus tard. Cet état de siège durera jusqu’au 12 octobre 1919, nonobstant le fait que les activités du Parlement aient repris leur cours normal en janvier 1915. Le pouvoir législatif français de 1914 a ainsi délégué une bonne partie de ses prérogatives et compétences à l’exécutif, ce qu’illustre de manière encore plus patente le vote du 10 février 1918 qui accorde au gouvernement des pouvoirs absolus: il pouvait dorénavant réglementer par décrets la production et le commerce des denrées alimentaires. L’exécutif devient ainsi le législatif, ce qui constitue une entorse flagrante au principe de la séparation des pouvoirs, théorisé au 18ème siècle par Montesquieu, un principe qui doit être, de nos jours, l’indice, pour les tenants du “politiquement correct”, d’une “bonne gouvernance”, du moins en théorie, car les représentants du “politiquement correct” ne sont pas prêts à laisser des libertés parlementaires à ceux qui pourraient contredire, même partiellement, leurs dogmes et leurs lubies. La fin des hostilités, le 11 novembre 1918, ne met pas un terme à ces pratiques: en 1924, le gouvernement Poincaré reçoit du Parlement les pleins pouvoirs en matières financières, suite à une crise grave qui ébranle le franc. En 1935, le gouvernement Laval énonce cinquante-cinq décrets “ayant force de loi” pour éviter la dévaluation du franc. L’opposition de gauche rejette certes ces mesures déclarées “fascistes” mais, aussitôt arrivé aux affaires par les urnes, Blum, le chef de file des gauches, recourt aux mêmes expédients: en juin 1937, il demande à son tour les pleins pouvoirs au Parlement pour sauver le franc. Les mesures d’exception, parfaitement compréhensibles en tant de guerre, ne cessent donc pas d’être appliquées, une fois la paix revenue mais, question légitime, est-ce une vraie paix? Ou est-ce la guerre qui continue par d’autres moyens? Ne vivons-nous pas, depuis août 1914, dans une ère de guerre totale et permanente, qui n’emploie pas toujours des moyens militaires pour arriver à ses fins ou porter préjudice aux ennemis? Gouverner un pays, théoriquement “démocratique”, par décrets devient donc la normalité, y compris dans les nations dites “libérales”.

L’Angleterre, modèle de démocratie pour Belien, n’échappe pas à la règle: le 4 août 1914, le “Defence of Realm Act”, en abrégé “DORA”, donne au gouvernement des pouvoirs très étendus pour réglementer la production de guerre et pour suspendre les droits civils (les tribunaux militaires peuvent désormais juger des civils, ce qui est une pratique contraire aux lois coutumières du Royaume-Uni, celles découlant de la jurisprudence relative à la “martial law” et aux “Mutiny Acts”). Le DORA permettra ainsi la répression en Irlande et l’exécution de seize révoltés des Pâques 1916. Après la Grande Guerre, le Parlement consent à accorder au gouvernement l’ “Emergency Powers Act”, le 29 octobre 1920, pour faire face à de graves troubles sociaux. Cet “Act” prévoyait aussi l’installation de “Courts of summary jurisdiction” pour tous ceux qui transgressaient l’ordre de ne pas entraver la distribution de vivres, d’eau ou de carburant.

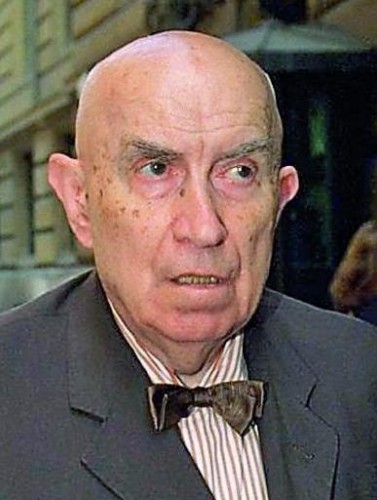

Résistances américaines au faux démocratisme de Wilson: le combat de Gerorge Norris et de Robert M. LaFollette

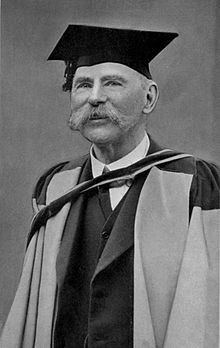

La résistance aux “pouvoirs spéciaux” votés en temps de guerre est particulièrement intéressante à observer dans l’histoire politique américaine. Toute une phalange de sénateurs et d’hommes politiques, essentiellement issus du Middle West et de Californie, se dresseront contre les manoeuvres du pouvoir central (“fédéral”), au point de recevoir l’appellation d’“insurgents” par leurs adversaires “wilsoniens”. Parmi eux, le Sénateur George Norris, qui fustigeait “les banquiers de Wall Street, assis derrière leurs bureaux en acajou et calculant comment convertir les misères de la guerre en or pour remplir leurs sales poches”. Pour Norris, il était désormais impossible de réconcilier les valeurs traditionnelles de la République américaine avec l’aventurisme militaire et son corollaire, la centralisation et la corruption du pouvoir gouvernemental”. Cette résistance, qui s’enracinait dans une fronde paysanne antérieure à 1914, craignait par dessus tout l’émergence d’une élite militaire et professionnelle qui ne devrait plus rendre de comptes au contrôle démocratique. De même, les “insurgents” tels Robert M. LaFollette (photo) et George Norris, interviennent au Congrès pour empêcher le vote de la motion Lansing (août 1915), visant à autoriser des prêts à la Grande-Bretagne et à la France, sous prétexte qu’il s’agissait de “parier unilatéralement sur la victoire de l’Entente”, ce qui risquait d’entraîner les Etats-Unis dans la guerre et “de sacrifier des vies humaines pour des bénéfices privés” sous la forme de contrats juteux. En 1916, LaFollette veut que les livraisons d’armes et de munitions aux belligérants soient définitivement interrompues: face à cette requête, le Président Wilson estime que les affaires étrangères relèvent d’une prérogative exclusive de l’Exécutif, indépendamment de tout apport parlementaire. Wilson estimait que les traditions parlementaires devaient céder le pas face à son grand projet de bâtir une “paix universelle” dès la fin des hostilités. LaFollette, pour sa part, pensait qu’un contrôle démocratique de la politique étrangère, telle qu’elle était menée par la Présidence, constituait une garantie de maintenir un maximum de paix dans le monde. Mieux: la non intervention des Etats-Unis dans la guerre aurait permis, pensait LaFollette, de maintenir, dans la société américaine, le monde paysan et honnête —la saine ruralité du Wisconsin— qu’il avait cherché à préserver dans ses combats d’avant la conflagration de 1914.

La résistance aux “pouvoirs spéciaux” votés en temps de guerre est particulièrement intéressante à observer dans l’histoire politique américaine. Toute une phalange de sénateurs et d’hommes politiques, essentiellement issus du Middle West et de Californie, se dresseront contre les manoeuvres du pouvoir central (“fédéral”), au point de recevoir l’appellation d’“insurgents” par leurs adversaires “wilsoniens”. Parmi eux, le Sénateur George Norris, qui fustigeait “les banquiers de Wall Street, assis derrière leurs bureaux en acajou et calculant comment convertir les misères de la guerre en or pour remplir leurs sales poches”. Pour Norris, il était désormais impossible de réconcilier les valeurs traditionnelles de la République américaine avec l’aventurisme militaire et son corollaire, la centralisation et la corruption du pouvoir gouvernemental”. Cette résistance, qui s’enracinait dans une fronde paysanne antérieure à 1914, craignait par dessus tout l’émergence d’une élite militaire et professionnelle qui ne devrait plus rendre de comptes au contrôle démocratique. De même, les “insurgents” tels Robert M. LaFollette (photo) et George Norris, interviennent au Congrès pour empêcher le vote de la motion Lansing (août 1915), visant à autoriser des prêts à la Grande-Bretagne et à la France, sous prétexte qu’il s’agissait de “parier unilatéralement sur la victoire de l’Entente”, ce qui risquait d’entraîner les Etats-Unis dans la guerre et “de sacrifier des vies humaines pour des bénéfices privés” sous la forme de contrats juteux. En 1916, LaFollette veut que les livraisons d’armes et de munitions aux belligérants soient définitivement interrompues: face à cette requête, le Président Wilson estime que les affaires étrangères relèvent d’une prérogative exclusive de l’Exécutif, indépendamment de tout apport parlementaire. Wilson estimait que les traditions parlementaires devaient céder le pas face à son grand projet de bâtir une “paix universelle” dès la fin des hostilités. LaFollette, pour sa part, pensait qu’un contrôle démocratique de la politique étrangère, telle qu’elle était menée par la Présidence, constituait une garantie de maintenir un maximum de paix dans le monde. Mieux: la non intervention des Etats-Unis dans la guerre aurait permis, pensait LaFollette, de maintenir, dans la société américaine, le monde paysan et honnête —la saine ruralité du Wisconsin— qu’il avait cherché à préserver dans ses combats d’avant la conflagration de 1914.

La “Croisade” de Wilson, “to make the world safe for democracy”, n’était pas autre chose, aux yeux de LaFollette, que le triomphe de Wall Street sur les “instincts naturels du peuple”. Hiram Johnson, Sénateur de Californie, était sur la même longueur d’ondes que son collège LaFollette du Wisconsin: “Nous ne serons plus jamais la même nation (...) Je doute fort que la République que nous avons connue dans le passé ne revienne jamais”. Johnson visait la coercition gouvernementale en marche, qui profitait de l’aubaine offerte par la guerre, la mainmise sur la vie publique des experts et des bureaux et, surtout, l’installation, dans la société américaine, d’une obsession née de la guerre, celle de l’efficacité et de l’urgence à tout prix et à tout moment. Hiram Johnson notait la croissance des pouvoirs factuels de l’administration et de l’industrie à l’abri de tout contrôle parlementaire. De même, il craignait l’extension du pouvoir exécutif aux dépens du législatif: les bureaucrates fédéraux, expliquait-il à ses électeurs, vont évoquer à tout bout de champ le besoin de sécurité pour briser les prérogatives du Congrès. La seule victoire (mitigée) qu’obtiennent toutefois les “insurgents” fut d’annuler un projet de Wilson de contrôler la distribution des journaux, en imposant une censure depuis les services postaux (ce qui a d’ailleurs été tenté en Belgique aussi, dans les années 90, pour juguler la distribution de dépliants et de revuettes émanant d’un parti considéré naguère comme challengeur de l’”Ordre de Loppem”). LaFollette essuie alors une campagne de presse virulente qui conduit une instance gouvernementale, la “Minnesota Commission of Public Safety”, à demander son expulsion du Sénat, arguant qu’il était “un professeur de déloyauté et de sédition procurant aide et facilité à nos ennemis”. On le brûle en effigie, on lui tend une corde avec noeud coulant dans les couloirs du Congrès: bref, on cherche à le briser moralement. La démarche de la “Minnesota Commission” n’aboutira pas: LaFollette sera sauvé par la signature de l’armistice du 11 novembre 1918. Il reprend aussitôt le combat contre le Traité de Versailles, où Wilson, disait-il, menait une “diplomatie personnelle” allant dans le sens des puissances impérialistes “qui avaient précipité l’Europe dans l’holocauste (des tranchées)”. LaFollette craignait aussi que l’Allemagne, réduite par les réparations à un espace de misère noire, connaîtrait tôt ou tard une révolution fatidique. Les Alliés, surtout la France, exigeaient des réparations astronomiques pour la simple et bonne raison qu’ils ne souhaitaient pas taxer leurs propres citoyens pour payer les frais de guerre. LaFollette s’est même avéré prophète: les projets de fusionner les flottes britannique et américaine au sein d’une “monster navy” destinée à protéger les investissements et les prêts accordés dans des zones “non développées”, conduiront à exploiter et à voler les peuples faibles et, par voie de conséquences, à instaurer sur la planète un état de guerre permanente (pour une étude minutieuse de cet aspect de l’histoire politique américaine, cf. David A. Horowitz, “Beyond Left & Right – Insurgency and the Establishment”, University of Illinois Press, Urbana/Chicago, 1997). Par la suite, Franklin Delano Roosevelt fera largement usage de ce type d’expédient, non démocratique, pour asseoir son pouvoir: songeons au “National Recovery Act” du 16 juin 1933, accordant au Président des pouvoirs quasi illimités pour gérer l’économie du pays.

Mussolini, Hitler et la notion d’“état d’exception permanent”

Les “démocraties” française, anglaise et américaine étaient victorieuses en 1918 et disposaient de colonies, capables de fournir aux métropoles des biens de toutes natures, matières premières comme denrées alimentaires. Mais les règles de guerre ont néanmoins été appliquées après les hostilités. Exactement comme en Italie, pays floué à Versailles malgré le sang versé, où le fascisme mussolinien avouera ne gouverner que par décrets (Mussolini: “La dictature fait en six heures ce que la démocratie fait en six ans”). Plus tard, après la parenthèse de la République de Weimar, démocratie exemplaire sur le plan théorique mais dont le fonctionnement n’a connu que des ratés, l’Allemagne adoptera, à son tour, un mode de fonctionnement fondé sur l’“Ausnahmezustand” permanent (= état d’exception), notamment sur base de théories proches de celles de Carl Schmitt, qui se bornent finalement à imiter des modèles français ou britannique, ou, pour le dire avec ironie, ... Hitler, élève de Poincaré (cf. Christoph Gusy, “Die Lehre vom Parteienstaat in der Weimarer Republik”, Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden, 1993). L’Allemagne avait toutefois l’excuse d’être un pays vaincu, ne disposant plus de colonies et obligé de payer des réparations aux montants astronomiques. Dans un tel cadre, elle était effectivement dans un “état d’exception” permanent.

Dans ce contexte affectant toutes les “démocraties” occidentales, le “coup de Loppem” s’explique mais ne s’excuse nullement sur le long terme, surtout s’il justifie des transpositions indues et une pérennisation infondée en des époques de non belligérance. Les traits autoritaires de la “gouvernance”, dans l’entre-deux-guerres, font qu’il n’existe plus, depuis lors, de démocraties pures. Immédiatement après la première guerre mondiale, il y avait parfois peu de différences entre la façon de gouverner une démocratie occidentale par décrets et “pouvoirs spéciaux” et le mode de fonctionnement d’une dictature à l’italienne ou à l’allemande, sans même mentionner les autres formes politiques autoritaires, observables en d’autres pays d’Europe pendant l’entre-deux-guerres. Il n’existe donc pas, objectivement parlant, de ligne séparant en toute netteté les démocraties rénovées à coup de décrets et les régimes plus ou moins fascistes. Cette vision d’une hypothétique séparation bien nette entre “démocraties” et “fascismes” est une lubie des bateleurs d’estrades médiatiques, clowns chargés de jeter de la poudre aux yeux des citoyens, voire “chiens de garde du système” (Serge Halimi).

Diverses voix s’élèvent contre le “coup de Loppem ”

Revenons à 1919, aux années 20, dès le lendemain du “coup de Loppem”. En marge des partis ronronnants —véritables machines tournant à vide et hostiles, par définition, à toutes formes de nouveauté et à toutes tentatives de redéfinir objectivement et positivement la politique sur le plan intellectuel— des voix diverses s’élèveront, dès le début de l’entre-deux-guerres, pour tenter de contester le nouvel agencement de l’Etat. Parmi ces voix, il faut compter:

1) Les communistes, galvanisés par les victoires de Lénine et de Trotsky, qui sentent d’instinct que le “coup de Loppem” entrave d’avance toute tentative, par un éventuel Lénine flamand ou wallon, de bouleverser le régime belge. Plusieurs artistes d’avant-garde seront au départ des compagnons de route des premiers communistes belges, pour devenir par la suite des “flamingants”, comme l’expressionniste Wies Moens et le surréaliste Marc Eemans, ou comme Paul Van Ostaijen et War Van Overstraeten. La césure entre communisme (marxiste) et nationalisme flamand n’est pas encore clairement affirmée au début des années 20. Le phénomène s’observe aussi dans d’autres pays européens.

2) Les flamingants du “Frontbeweging”, qui estiment que l’on n’a pas demandé l’avis des soldats du front, majoritairement recrutés dans les deux provinces de Flandre orientale et de Flandre occidentale, voire dans les communes rurales du Brabant et à Bruxelles (où les monuments aux morts présentent des listes aussi impressionnantes qu’en France). Un Joris van Severen ne peut pas tolérer, par exemple, que la génération du front ait été évincée du compromis et que les revendications flamandes, formulées par des soldats du contingent après trois ou quatre ans de tranchées dans les boues ouest-flamandes, n’y trouvent aucun créneau d’expression.

3) Les francophones de la “Légion Nationale”, issue elle aussi des anciens combattants et flanquée de jeunes gens venus de l’aile la plus conservatrice du parti catholique, contestent également le dispositif de Loppem, dans la mesure où il ne donne pas une voix privilégiée aux anciens combattants, aux “arditi” belges (dont Hoornaert et Poulet), désireux d’imiter leurs homologues italiens ou de faire le “coup de Fiume” perpétré par Gabriele d’Annunzio (un poète-soldat admiré par le socialiste Jules Destrée). Au sein de cette mouvance de la “Légion Nationale” d’Hoornaert et au sein de l’aile conservatrice du parti catholique, une fragmentation graduelle aura lieu: certains conservateurs resteront dans le bercail catholique (Harmel, Hommel, du Bus de Warnaffe, etc.), d’autres seront tentés par le rexisme (Pierre Daye) ou par le technocratisme de Van Zeeland (jugé idéologiquement “neutre” et plus apte pour gouverner avec les socialistes). D’autres encore demeureront fidèles à la “Légion Nationale”: celle-ci connaîtra, dès 1940, une aile majoritairement résistancialiste et une aile minoritaire collaborationniste (l’officier Henri Derriks au sein de la “Légion Wallonie”). L’historien liégeois Francis Balace est le seul résidu actuel de cet esprit, bien qu’édulcoré par l’ambiance consumériste et festiviste de notre époque; il est le fils d’un ancien “légionnaire national” et défend l’esprit de cette “Légion belge” au sein de la “Légion Wallonie” de la Wehrmacht allemande et de la Waffen SS, contre les “degrelliens”, avec l’appui zélé de son élève, l’historien Eddy De Bruyne, très productif en ces matières désormais complètement “historicisées”.

4) Parmi les opposants au système de Loppem, il faut aussi compter les nombreux non conformistes de toutes catégories, non inféodés à des organisations ou des partis, adeptes d’un joyeux anarchisme contestataire, visant par le rire et la provocation à faire la nique aux bourgeois. Ces catégories avaient été “oubliées” des historiens des idées jusqu’à la parution du livre du Prof. Jean-François Füeg, “Le Rouge et le Noir – La tribune bruxelloise non-conformiste des années 30” (Quorum, Ottignies LLN, 1995); cet ouvrage relate les aléas d’un club non politique, qui se pose comme anarchisant et anti-autoritaire et qui a animé la vie intellectuelle bruxelloise de la fin des années 20 à 1940. Cette gauche non conformiste (“orwellienne” dans le sens où l’entend aujourd’hui, en France, un Jean-Claude Michéa) connaîtra des lézardes en son sein à partir de la guerre d’Espagne, où, comme Orwell, elle déplore la répression commise par les communistes staliniens contre les gauches anarchistes et indépendantes à Barcelone. Un anti-communisme de gauche voit le jour à Bruxelles suite aux événements d’Espagne. L’artiste War Van Overstraete (son portrait d’Henry Bauchau rappelle la “patte” du vorticiste anglais Wyndham Lewis), qui est d’abord un sympathisant communiste, prend ses distances avec le “Komintern” dès l’effondrement du front de Barcelone, exactement comme le font alors Orwell ou Koestler, et retourne à ses idées originales, celles d’une “renaissance du socialisme”, qu’il avait couchées sur le papier en 1933. Un Gabriel Figeys, connu sous le pseudonyme de Miel Zankin, anarcho-communiste, soutiendra la politique royale de neutralité, énoncée en octobre 1936 par Léopold III, en dénonçant avec toute la virulence voulue “l’internationale des charognards”, puis rejoindra les rangs collaborationnistes, tandis que d’autres, tels Pierre Fontaine, auteur d’un pamphlet anti-rexiste en 1937, se retireront dans leur cabinet pendant la seconde guerre mondiale, mais réémergeront après cette deuxième grande conflagration intereuropéenne pour fonder le seul hebdomadaire de droite anti-communiste après 1945, “Europe-Magazine”. Les tribulations du “Rouge et Noir” montrent bien que les marginalisés de “gauche” comme de “droite” tournent, exclus, autour du bloc conformiste et fermé sur lui-même, le bloc de Loppem, un bloc aujourd’hui en implosion, parce qu’il n’a jamais pu ni intégrer ni assimiler les véritables porteurs de sang neuf (à part quelques opportunistes vite neutralisés à coups de “fromages” et de “prébendes”). Juste avant d’être exclu avec fracas du PCF, du temps de Georges Marchais, Roger Garaudy avait placé ses espoirs dans une alliance générale de ces marginalisés et de ces exclus pour assiéger le bastion conformiste français mitterrando-chiraquien et le faire tomber; ses voeux ne se sont pas exaucés malgré sa participation à des initiatives vite qualifiées de “rouges-brunes” par les “chiens de garde du système”, sous prétexte qu’y avait participé, plutôt de loin que de près, un vieux pitre pusillanime, cherchant à fourrer son groin partout, le néo-droitiste Alain de Benoist.

Lottizzazione, Proporz et amigocratie

Le “coup de Loppem” instaure donc ce que l’on appelle la partitocratie belge, étendue à toutes les associations, clubs, syndicats, mutuelles ou ligues formant les trois “piliers” du monde politique du royaume. Puisqu’il y a trois parties prenantes dans ce dispositif, on a coutume, dans la presse subsidiée et pondue par les “chiens de garde”, de déclarer le système “pluraliste”. Ce pluralisme est hypocrite: il y a un système en trois partis, comme le catéchisme des temps jadis nous enseignait qu’il y avait un Dieu en trois personnes. Nous avons bien plutôt la juxtaposition de trois totalitarismes qui ne sont en concurrence que pour satisfaire les apparences. En effet, au fil du temps, on s’est aperçu que ce dispositif ternaire ne tolérait plus l’autonomie des députés, se mêlait de tous les aspects de la vie privée des administrés, restreignait la liberté de travailler et de s’épanouir professionnellement, y compris au niveau académique, mettait subrepticement un terme à toutes les formes de “droit de résistance” (dont Agamben constate et déplore la disparition), procédait pour se maintenir ad vitam aeternam, par l’expédient que les Italiens nomment la “lottizzazione”, les Autrichiens le “Proporz” et les analystes flamands de la “verzuiling/pilarisation” l’“amigocratie”, soit la manie de distribuer, au pro rata des voix obtenues, les postes administratifs, des plus lucratifs aux plus modestes, dans les ministères ou dans les “para-stataux” (chemins de fer, poste, voies aériennes du temps de la SABENA, etc.) aux petits camarades du parti, souvent les lèche-cul les plus obséquieux du “chef”, à coup sûr toujours moins brillants et moins efficaces que leurs homologues qui se désintéressent des vulgarités et des intrigues politiciennes et triment dur dans la société civile laquelle ne fait pas de cadeaux.

“Come cambiare?” du Prof. Gianfranco Miglio