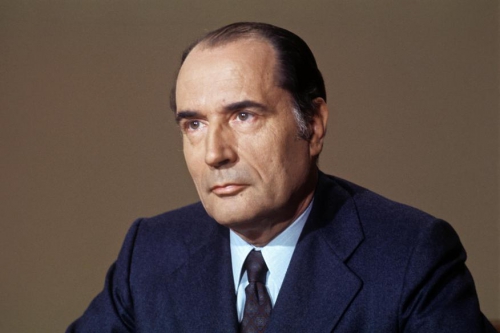

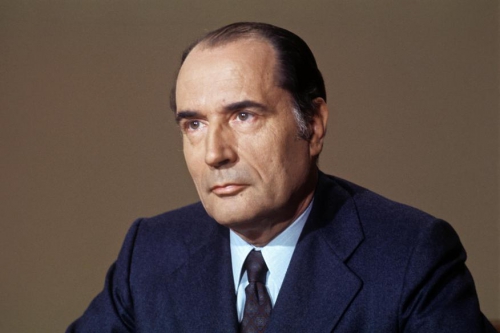

François Mitterrand:

European Statesman, Anti-American, & Judeophobe

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

President François Mitterrand is a notoriously ambiguous figure and one which, indeed, is an object of both interest and repulsion for the European Right. In his trilogy of little memoirs, hastily written at the end of his life, the president and founder of the European Union makes clear that his passion for “European integration” was founded upon a hostility to the United States of America’s domination of the Old Continent. Intense hostility to American power as well as Jewish power is also evident from private comments he made to his friends and associates. Yet, Mitterrand was also instrumental in the ostracism and persecution of French nationalists from the 1980s onwards.

Mitterrand had been traumatized by the Fall of France in 1940 – during which he had been captured as a soldier before escaping to Vichy after two previous failed attempts. He had personally witnessed European nations’ fratricidal war and calamitous fall from world-hegemony to imperial dependencies of the American and Soviet superpowers. The solution, as he saw it, was eternal peace in Europe and the creation of a European superpower through a fusion of nations, and in particular of France and Germany.

Hostility to American power is evident throughout Mitterrand’s memoirs. He says he rejected the proposed European Defense Community in the 1950s – which would have created a kind of European army made up of French, West German, Italian, and Benelux troops – because it would have been under effective American control:

To refuse the [European Defense Community] was to take the risk of knocking down the fragile edifice of the emerging Europe. To accept it would be a contradiction. To build the Europe of generals before a serious embryo of political authority existed, especially in this period of cold war, left the field too open to general staffs who would have been in a position to determine the fate of Europe and of the countries making it up through the military necessities they would have alone been judges of. And as speaking of general staffs in the plural was in addition no more than a fiction, this defense community would only have been an additional instrument at the service of the Pentagon. That is to say of the Americans. I had not forgotten that at [Georges] Bidault’s request [John] Foster Dulles had gone so far as to imagine deploying the atomic bomb in Vietnam. I could not conceive of Europe being so colonized, and I feared would be destroyed both the body and the soul of what appeared to me as the great ambition of men of my time.[1]

Mitterrand’s attitude towards U.S. influence in Europe had not fundamentally changed between the 1950s and 1990s. He said on the American view of post-Cold War Europe: “the concept of European unity did not mean the same reality depending on if one was American or French.”[2] He rejected closer ties with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who was gravely concerned about the return of German power, citing the same concerns:

Great Britain did not have sufficient leeway to escape the control of the United States, and I would not exchange European construction, of which Federal Germany was one of the pillars, for a Franco-English entente which was desirable but reduced to good wishes.[3]

In private, Mitterrand would go further, telling the journalist Georges-Marc Benamou, with whom he was co-writing one of his memoirs:

France is at war with America. Yes, a constant war, a vital war, an economic war, a war without death. In appearance. Yes, they are very tough, the Americans, they are rapacious, they want undisputed power over the world . . . You saw, after the Gulf war, that they wanted to control this part of the world. They left nothing to their allies.[4]

Certainly, those on the Right have long lamented that after the Second World War all the nations of Europe were subjected to the Soviet and American Empires. The Soviet Union imposed crude military coercion. The United States in contrast reduced Western Europe to a fluctuating combination of economic, military-atomic, political, and, most perniciously, cultural dependence.[5]

But why was Mitterrand so concerned with American power over Europe? What, exactly, is the problem from a so-called universalist liberal-democratic perspective? Mitterrand’s private comments perhaps provide an indication. On May 17, 1995, his last day in office as president, Mitterrand told a friend inquiring about the continuing media-political campaign surrounding his association with former Secretary-General of the Police René Bousquet (who had deported Jews during the Second World War): “You are observing here the powerful and harmful influence of the Jewish lobby in France.”[6] If France, according to François Mitterrand, suffers from “the powerful and harmful influence of the Jewish lobby,” well then what dark forces of disintegration, eternally hostile to Europe, are lurking in America?

Mitterrand the European and Prussophile

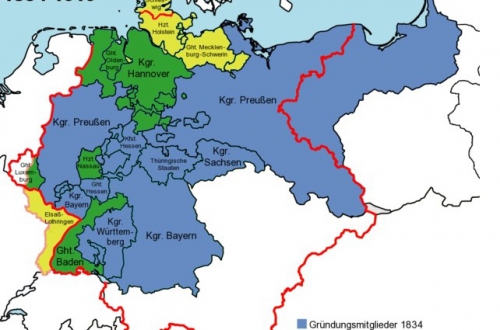

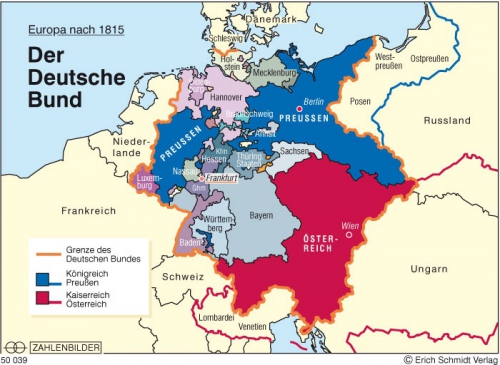

Perhaps surprisingly for a Frenchman, Mitterrand saw the shattered German realm of Prussia as an important part of Europe’s redemption. He considered Prussia’s destruction by the Allies in 1945 as a great injustice designed to “strike Germany to the head,” reducing that great nation to decerebrated impotence. Mitterrand notes: “The influence of the United States exercised itself more strongly over the Federal Republic than over France – or at least with more success.”[7] But the Germans, unlike the British, at least wanted to “build Europe.”

Mitterrand sharply distinguishes between the culture and civilization of Prussia and National Socialism.[8] He seems to imagine German Reunification as a kind of return of Prussia to the Federal Republic:

Prussia, home of civilization and culture, inseparable from the civilization and culture that we, Frenchmen, claim as our own . . . before the end of the century Prussia would reappear in her real dimension, one of the richest reservoirs of men and means of Europe and Germany.[9]

Germany would then find its “head” through reunification with “Prussia,” which in turn would free Europe, through Germany’s union with France.

Indeed, Mitterrand went so far, in one of his last speeches in Berlin, to praise the courage of the Third Reich’s soldiers, offending many Jews:

I knew what there was of strong in the German people, its virtues, its courage, and his uniform matters little to me, and even the idea which inhabited the spirit of these soldiers who would die in such large numbers. They were brave, they accepted to lose their lives. For a bad cause, but their gesture had nothing to do with that. They loved their country.[10]

In any event, Mitterrand’s Prussophilia was too optimistic to not say archaic. Prussia is not reborn. Reunification, in destroying the oddly national socialist German Democratic Republic,[11] actually furthered Germany’s demographic collapse with a sharp fall of fertility in the east and continued economic retardation. But there are flickers in the embers: The Patriots Against the Islamization of the West (PEGIDA) protests are strongest in former Prussia, and it is eastern Germans who have radicalized Alternative for Germany (AfD) towards focus against immigration.

Mitterrand rejected the “Europe of Generals” in the 1950s. Yet he proved was the single most important figure in pushing for the “Europe of Bankers” created by the Maastricht Treaty in the 1990s, with its unlimited free movement of capital and its formal reduction of states to dependence upon financial markets. But Mitterrand apparently hoped this would be compensated by the creation of a European common currency – the écu or the Euro – and a powerful, autocratic European Central Bank. In destroying the Deutsche Mark and creating a formidable European currency to rival the U.S. dollar, Mitterrand believed the monetary dominance of the German Bundesbank and of the U.S. Federal Reserve would be ended. The Mitterrandian poetry reaches its greatest heights on this theme of Franco-German reconciliation and European power:

The incessant tumult of History teaches the vanity of treaties as soon as the balance of power changes. . . . I cannot give up however of the idea that a society can survive only by its institutions. So it will be with Europe. Given that everything thus far rests upon force which itself gives way only to violence, let us break this logic and replace it with free contract. If the community, the daughter of reason, adopts lasting structures, victor, vanquished, these notions will belong to our prehistory. The smallness of our continent, the birth of the [European] Community which includes two thirds of its inhabitants, the need felt in both the east and West of Europe to exist and influence the destiny of the planet by widening the vice which, from Asia and America, is closing upon us, are pushing for this realization. I dream of the predestination of Germany and France, which geography and their old rivalry designate to give the signal. I also work towards this. . . . If they have kept within themselves the best of what I do not hesitate to call their instinct of greatness, they will understand that this here is a project worthy of them. I am drawing a design which I know will be muddled, compromised year by year, beyond this century. . . . France is always tempted by withdrawal upon herself and the epic illusion of glory in solitude . . . The great powers of the rest of the world will seek to ruin the arrival of an order which is not theirs. Those nostalgic for death on the street corner, of the hospital one crushes beneath bombs, of car bombs for the sole honor of raising up a plot of land as a nation, with its border posts at the first hedge, will wrap themselves in the folds of a thousand and one flags . . .[12]

Pétain and Mitterrand

Mitterrand’s Failure

France, whether embodied in a De Gaulle, a Mitterrand, or a Le Pen, has often provided inspiration for Europeans in other countries who dream of freeing the Old Continent from foreign domination. The French enjoyed a relative freedom and national ambitions far beyond anything the occupied Germans could be allowed to have.

France’s decline is viscerally-felt and painful for the French. Indeed, the French political class, at least from the beginning of the presidency of Charles de Gaulle in 1958 to that of Nicolas Sarkozy in 2007, was sincerely motivated to strengthen French and Europe as a power in the world. This was evident in autonomy within NATO, a relatively independent “Arab policy,” the push for European integration, efforts to promote French language and culture through various protectionist measures, and opposition to the 2003 Iraq War. These efforts were overwhelmingly conservative ones, however, and completely disregarded the deep roots of the nation’s decadence, and were thus doomed to failure.

Mitterrand himself was haunted by the decline of France. He told Benamou:

In fact, I am the last of the great presidents . . . Well, I mean the last in the line of De Gaulle. After me, there will be no more in France . . . Because of Europe . . . Because of globalization . . . Because of the necessary evolution of institutions.[13]

Charles de Gaulle had a similar view. But while the General believed Europe had been strongest, most free and alive, when there had been vigorous warring nations, Mitterrand famously declared that “Nationalism is war!”

Mitterrand was entirely complicit in the demonization of European nationalisms and the rise of the Shoah to what Éric Zemmour has called “the official religion of the French Republic,”[14] notably with the passage of the Fabius-Gayssot Act criminalizing critical historical study of the Holocaust. He empowered Jewish “anti-racist” organizations such as the CRIF, the LICRA, and SOS Racisme. He participated in a concerted police and politico-media campaign to frame the Front National for the desecration of a Jewish cemetery at Carpentras in 1990, indefinitely excommunicating that party from respectability in the eyes of mainstream public opinion. Mitterrand did this for personal and political gain, pandering to the most powerful ethnic networks in the country, and working to keep the Socialist Party in power, despite its manifest economic failures, by dividing the opposition into a “mainstream” right and a “far-right.”

Alain Soral has said that whomever rises by the Jews must fall by the Jews. And, sure enough, Mitterrand was caught in his web of sins: He empowered Jewish organizations to persecute revisionist historians and nationalist activists in the name of the Shoah, but in turn an ever-more-vocal fraction of this same community resented Mitterrand’s own so-called “ambiguities” on the Vichy period, namely his youthful admiration for Marshal Philippe Pétain, his postwar association with Bousquet, and his refusal to officially debase France by recognizing collective and national guilt for participation in the Holocaust.[15]

Characteristically, Mitterrand chose to write his three memoirs with the collaboration of three Jews: the infamous Elie Wiesel, the young Georges-Marc Benhamou, and the atrociously-botoxed publisher Odile Jacob. This no doubt reflected the density of Jewish networks around Mitterrand, many in which still had affection for the old leader, but also (especially in the case of the High Priest of Holocaustianity Wiesel) an attempt by Mitterrand to secure his legacy and respectability before the Jewish community.

Mitterrand’s attempts to appease ethnocentric Jews[16] naturally failed. He continued to be attacked until his dying day and, after his death, Wiesel all but called the recently-departed president a liar, accusing him of “a deformation of facts” and “falsehood” concerning “that bastard Bousquet.”[17] Benamou also repeatedly tried to get Mitterrand to confess some imagined guilt, but failed:

Actually, François Mitterrand did not believe in the specificity of the holocaust, despite his fascination for the Old Testament and his ‘friendship for the Jewish people.’ He had not understood the Twentieth Century and its tragedy. . . . He had always been indifferent to the Jewish question, and that is a positive point, in view of his milieu. The flip side is that this indifference never allowed him to understand the scale of the Jewish tragedy. He was a man of the Nineteenth Century, that is, a man who considered the greatest tragedy of all time to be Verdun, those thousands square kilometers overturned by bombs, that ossuary. . . .

But the cornered monarch had closed in on himself. This confrontation had taken for him such an obsessive turn that to concede apologies on behalf of France, in his eyes, was a personal humiliation. He had convinced himself of this and became again, in these movements, that Gaulish chieftain that I did not like very much.[18]

Indeed, neither Wiesel nor Benamou could tolerate the arrogance of a goy prince who would put his own dead, those French peasants rooted for millennia, before those of their own Tribe. Mitterrand could protest to Benamou that wartime was complicated: “Young man, you do not know what you are talking about,” to no avail.

Mitterrand apparently believed that Europe could become a world-power despite the hegemony of a hostile anti-European culture, despite the demonization of any European ethno-national self-assertion, and despite the founding of the “European Union” on fundamentally neoliberal and plutocratic principles of open borders.

So far, his œuvre has singularly failed, with the Eurozone in particular being a byword for economic failure and permanent crisis. Perhaps this is unsurprising. Indeed, even in his own day Mitterrand had a singular contempt for the man he had appointed to oversee – or perhaps, merely, spectate over – his grand design: European Commission President Jacques Delors. Mitterrand mocks Delors as a non-entity, doing who-knows-what in Brussels, superficially idealized by the French media. He reacts to Delors’ declaration that he would not be running for president despite the superficial polls in his favor: “Oh, what a non-event on live television, that doesn’t happen every day!”[19] It seems very strange of Mitterrand to be so invested in the European Union as his “legacy,” and yet be so mocking of his chosen executor. Indeed, elsewhere he argues that European leaders will know to be conciliatory and push forward with integration precisely because of the fragility of the project: “They know that the European Meccano would collapse if one piece were removed.”[20] That is not exactly a vote of a confidence in a sound foundation.

The ultimate legacy of the flawed Union Mitterrand bestowed upon Europe remains unclear. Perhaps, it is a bridge too far in transnationalism which will, in a dialectical response, bring about a nationalist regime firmly dedicated to the restoration of the nation-state. Perhaps, as Guillaume Faye hoped, the Union can in time be hijacked as an effective power which would enable Europe’s emancipation from the small-states’ seductive temptation of collaboration with American political and military power. Perhaps the whole EU project will simply prove irrelevant to the continued steady decline of Europeans in the face of American cultural-political hegemony and Afro-Islamic demographic submersion.

And what can we conclude on Mitterrand? Every man is indelibly marked by the world of his childhood. In the case of Mitterrand, he was raised a French-speaking, Right-wing Catholic milieu in which America, Jewry, and high finance were seen with suspicion as corrupting and overlapping entities. The values of Mitterrand’s childhood milieu had many similarities with those of a Charles de Gaulle, a Léon Degrelle, or a Hergé, men who also dreamed, each in their way, of a Europe free from America.

There is little logic in Mitterrand’s sinuous rise to power besides perhaps a hostility to an overbearing De Gaulle, openness to alliance with the French Communists, and a good feel for the political center of gravity of the country. Mitterrand served as a decorated Vichy official, joined the Resistance, quickly rose as a postwar minister in the corrupt, parliamentary Fourth Republic and pledged to defend French Algeria. After over two decades in the desert of opposition, he finally became the first Socialist President of the Fifth Republic in 1981, after which he quickly had to renege upon his exaggerated social promises, but maintained his power in part through collaboration with ethnocentric Jewish networks.

In a sense, Mitterrand betrayed the values of his childhood and yet he never went far enough to fully appease a large fraction of the Jewish community. I cannot help but think, in his sincere reconciliation with Germany and his clumsy efforts to set the foundations for a European superpower, Mitterrand also sought to redeem his European soul.

Notes

1. François Mitterrand, Mémoires interrompus (Paris: Odile Jacob, 1996), 212-3.

2. François Mitterrand, De l’Allemagne, de la France (Paris: Odile Jacob, 1997), 45.

3. Mitterrand, De l’Allemagne, 43.

4. Georges-Marc Benamou, Le dernier Mitterrand (Paris: Plon, 1996), 52.

5. Kevin B. MacDonald, The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political Movements (1st Book Library: 2002).

6. Renaud Dely, “Quand Mitterrand parlait du ‘lobby juif’,” Libération, August 27, 1999. http://www.liberation.fr/politiques/1999/08/27/quand-mitterrand-parlait-du-lobby-juif-jean-d-ormesson-revele-des-propos-tenus-en-1995_280524

7. Mitterrand, De l’Allemagne, 139.

8. Indeed, anti-Nazism is the stated center of Mitterrand’s moral universe. In fact there are both breaks and continuity between Frederick the Great’s Prussia and Adolf Hitler’s Germany. Among the points of continuity: autocracy, militarism, and sacrifice.

9. Mitterrand, De l’Allemagne, 125.

10. Jean Guisnel, “Mitterrand célèbre les soldats morts, allemands compris,” Libération, May 10, 1995. http://www.liberation.fr/evenement/1995/05/10/mitterrand-celebre-les-soldats-morts-allemands-compris_133400

11. The GDR, despite its obsessive anti-Nazism, appeared very national socialist in its Prusso-Stalinism. Indeed, from a demographic point of view East Germany was a superior regime, maintaining higher birth rates and encouraging the more educated to have children.

12. Mitterrand, De l’Allemagne, 128-9.

13. Benhamou, Mitterrand, 146. Indeed, Mitterrand seems to be the last French president whose name American journalists can remember, as miserable an indicator as any. http://www.ohmymag.com/le-petit-journal/le-petit-journal-les-journalistes-americains-ont-du-mal-avec-le-president-francais_art73699.html

14. Éric Zemmour, “The Rise of the Shoah as the Official Religion of the French Republic,” The Occidental Observer, May 12, 2015. http://www.theoccidentalobserver.net/2015/05/eric-zemmour-the-rise-of-the-shoah-as-the-official-religion-of-the-french-republic/

15. Towards the end of his term as president, Mitterrand famously rejected on live television the Sephardic journalist Jean-Pierre Elkabbach’s relaying Jewish organizations’ demands for “apologies” for Vichy:

Mitterrand: “They will wait a long time. They will not get any. France has no need to apologize, nor has the Republic. I would never accept it. I consider that it is an excessive demand from people who do not deeply feel what it means to be French and the honor of being French, and the honor of the history of France. . . .

Elkabbach: “[You successors] will also feel the pressure.

Mitterrand: [Scoffs.] “Perhaps in a hundred year still too? What does this mean? This maintains hatred and it is not hatred which must govern France.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=owFF0K9-jcs

16. And Wiesel is truly absurdly ethnocentric in his unenlightening book of interviews with Mitterrand. He opens the book with: “For us, Jews,” and never stops. At least half the questions must have a Jewish focus or framing. I am sorry if I must appear unkind but such selfish self-centeredness is rightly mocked. In his interventions, Wiesel mentions the synagogue, the concentration, the psychoanalyst, the Talmudic sage, a Talmudic saying, “the death of a Hasidic master,” the trauma of forgetting his speech scrolls while in Israel (because he is “very pious,” he says), his being raised “the Bible” [sic], the Jewish tradition, the Yiddish writer, the rabbi, Kafka’s equaling Dostoevsky, and on and on and on. As the libertarian comedian Doug Stanhope has put it: “Jew, Jew, Jew, Jew, Jew, Jew, Jew, Jew!” Wiesel also repeatedly, and quite transparently, emotionally manipulates through selective righteous indignation, either to distract (Biafra, Yugoslavia) or to harass the Jews’ enemies (Islamic fundamentalism in Iran and Algeria, Iranian and Libyan efforts to get nuclear weapons . . .) without a peep on Israel’s crimes against the Palestinians or its nuclear weapons. François Mitterrand and Elie Wiesel, Mémoire à deux voix (Paris: Odile Jacob, 1997).

17. Christophe Barbier, “Wiesel Contre Mitterrand,” L’Express, October 3, 1996. http://www.lexpress.fr/informations/wiesel-contre-mitterrand_618526.html

18. Benamou, Mitterrand, 199-201.

19. Benamou, Mitterrand, 90.

20. Mitterrand, De l’Allemagne, 129-30.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

La democrazia è stata imposta all’Europa settant’anni fa con la conclusione disastrosa della seconda guerra mondiale, ma i suoi effetti deleteri hanno cominciato a diventare evidenti dopo la fine della Guerra Fredda, con la messa in atto della decisione di trasformare l’intera umanità in un’orda meticcia facilmente manovrabile dal potere dietro le quinte del sistema democratico, di recidere il legame sempre esistito e che rappresenta l’ordine normale delle cose, tra sangue e suolo.

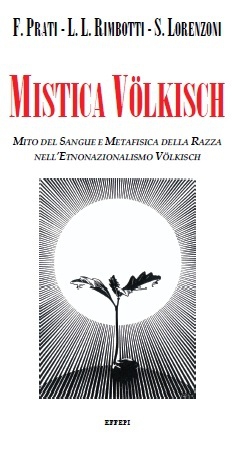

La democrazia è stata imposta all’Europa settant’anni fa con la conclusione disastrosa della seconda guerra mondiale, ma i suoi effetti deleteri hanno cominciato a diventare evidenti dopo la fine della Guerra Fredda, con la messa in atto della decisione di trasformare l’intera umanità in un’orda meticcia facilmente manovrabile dal potere dietro le quinte del sistema democratico, di recidere il legame sempre esistito e che rappresenta l’ordine normale delle cose, tra sangue e suolo. Riguardo a Evola, è importante precisare che molti hanno voluto vedere in Evola il teorico di una dottrina spirituale della razza in contrapposizione alla visione nazionalsocialista e in particolare dell’ideologo del nazionalsocialismo, Alfred Rosenberg, che si è voluta riduttivamente interpretare come un rozzo materialismo biologico. Questa interpretazione, ci assicurano i nostri autori, è completamente falsa, riesce a stare in piedi solo se si evita e si impedisca che sia accessibile la lettura di prima mano dei testi nazionalsocialisti, e in particolare del ponderoso Mito del XX secolo di Rosenberg, secondo la prassi democratica che consiste nella censura e nell’impedire il confronto delle idee, altrimenti sarebbe chiaro che il nazionalsocialismo e Rosenberg ebbero ben chiara la dimensione spirituale connessa al “mito del sangue”.

Riguardo a Evola, è importante precisare che molti hanno voluto vedere in Evola il teorico di una dottrina spirituale della razza in contrapposizione alla visione nazionalsocialista e in particolare dell’ideologo del nazionalsocialismo, Alfred Rosenberg, che si è voluta riduttivamente interpretare come un rozzo materialismo biologico. Questa interpretazione, ci assicurano i nostri autori, è completamente falsa, riesce a stare in piedi solo se si evita e si impedisca che sia accessibile la lettura di prima mano dei testi nazionalsocialisti, e in particolare del ponderoso Mito del XX secolo di Rosenberg, secondo la prassi democratica che consiste nella censura e nell’impedire il confronto delle idee, altrimenti sarebbe chiaro che il nazionalsocialismo e Rosenberg ebbero ben chiara la dimensione spirituale connessa al “mito del sangue”.

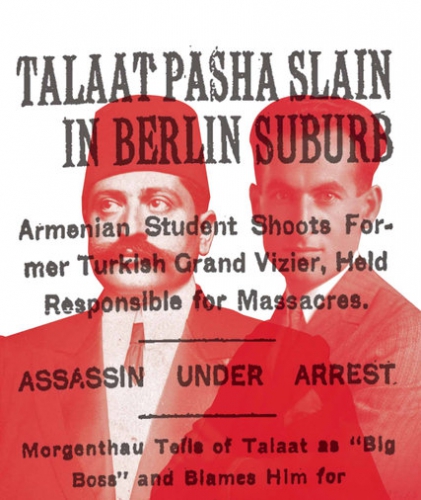

Christian soldiers — who, thanks to their new constitutional equal rights, could now serve in the military — were disarmed and put in work battalions, after which they were worked to death or slaughtered outright. On April 24, 1915, the Armenian community was decapitated. Some 250 prominent Armenians in Constantinople were arrested and subsequently murdered. In the Armenian homelands in the East, the genocide took place under the pretext of deportation and resettlement. Armenians packed and cataloged their valuables, handed over assets, and were marched out of their towns, where they were plundered and massacred, often with sickening Oriental sadism. Those who were not killed outright were marched to desert internment camps where they perished through disease, hunger, and violence. Between 800,000 and 1.4 million Armenians died, as well as more than half a million Greeks and Assyrians. Hundreds of thousands became refugees. By the end of the war, the Ottoman Empire had virtually eliminated its Armenian population.

Christian soldiers — who, thanks to their new constitutional equal rights, could now serve in the military — were disarmed and put in work battalions, after which they were worked to death or slaughtered outright. On April 24, 1915, the Armenian community was decapitated. Some 250 prominent Armenians in Constantinople were arrested and subsequently murdered. In the Armenian homelands in the East, the genocide took place under the pretext of deportation and resettlement. Armenians packed and cataloged their valuables, handed over assets, and were marched out of their towns, where they were plundered and massacred, often with sickening Oriental sadism. Those who were not killed outright were marched to desert internment camps where they perished through disease, hunger, and violence. Between 800,000 and 1.4 million Armenians died, as well as more than half a million Greeks and Assyrians. Hundreds of thousands became refugees. By the end of the war, the Ottoman Empire had virtually eliminated its Armenian population.

De por sí son destacables los conceptos de las ideas políticas de Imperio e imperialismo que presenta Jorge Luna Yepes, con una visión desprejuiciada y nada común en el Ecuador, por aportar con estas a un mejor y más pleno entendimiento de nuestra realidad política-histórica en el continente americano; donde la palabra Imperio se volvió sinónimo de la explotación capitalista estadounidense, siendo usual escuchar a los sectores ideológicos de izquierda –sobre todo- referirse despectivamente a Estados Unidos como “el imperio”, e incluso haciendo alusiones similares –en el sentido de explotación capitalista- a otros países, en particular a España por su claro pasado imperial en América.

De por sí son destacables los conceptos de las ideas políticas de Imperio e imperialismo que presenta Jorge Luna Yepes, con una visión desprejuiciada y nada común en el Ecuador, por aportar con estas a un mejor y más pleno entendimiento de nuestra realidad política-histórica en el continente americano; donde la palabra Imperio se volvió sinónimo de la explotación capitalista estadounidense, siendo usual escuchar a los sectores ideológicos de izquierda –sobre todo- referirse despectivamente a Estados Unidos como “el imperio”, e incluso haciendo alusiones similares –en el sentido de explotación capitalista- a otros países, en particular a España por su claro pasado imperial en América.

Influencé par Nietzsche et Carlyle, Maurice Spronck publie en 1894 une contre-utopie (ou dystopie). Thomas More, Francis Bacon, Tommaso Campanella pariaient sur l’avenir ou l’onirisme pour élaborer des systèmes politiques et sociaux parfaits dans lesquels les êtres humains s’épanouiraient harmonieusement au contraire de la dystopie popularisée par les écrivains de science-fiction et d’anticipation (Eugène Zamiatine, écrivain de Nous autres, Aldous Huxley dans Le meilleur des mondes, George Orwell avec 1984, René Barjavel pour Ravage, Ray Bradbury et son Fahrenheit 451). L’an 330 de la République fait de Maurice Spronck un étonnant précurseur.

Influencé par Nietzsche et Carlyle, Maurice Spronck publie en 1894 une contre-utopie (ou dystopie). Thomas More, Francis Bacon, Tommaso Campanella pariaient sur l’avenir ou l’onirisme pour élaborer des systèmes politiques et sociaux parfaits dans lesquels les êtres humains s’épanouiraient harmonieusement au contraire de la dystopie popularisée par les écrivains de science-fiction et d’anticipation (Eugène Zamiatine, écrivain de Nous autres, Aldous Huxley dans Le meilleur des mondes, George Orwell avec 1984, René Barjavel pour Ravage, Ray Bradbury et son Fahrenheit 451). L’an 330 de la République fait de Maurice Spronck un étonnant précurseur.

Face aux réformes europhobes et même eurocidaires, car destinées à briser la mémoire historique des Européens, et notamment celles en préparation par le gouvernement PS en France, nous devons opposer un contre-programme de résistance. Voici quelques éléments de réflexion en ce sens de ce que pourrait être un programme d’enseignement de l’histoire de l’Europe destiné à promouvoir notre longue mémoire au lieu de chercher à la détruire au nom d’un « multikulti » délirant destiné à faire place libre. J’utiliserai ici la terminologie française classique (6ème à terminale) mais des équivalents existent dans tous les pays d’Europe.

Face aux réformes europhobes et même eurocidaires, car destinées à briser la mémoire historique des Européens, et notamment celles en préparation par le gouvernement PS en France, nous devons opposer un contre-programme de résistance. Voici quelques éléments de réflexion en ce sens de ce que pourrait être un programme d’enseignement de l’histoire de l’Europe destiné à promouvoir notre longue mémoire au lieu de chercher à la détruire au nom d’un « multikulti » délirant destiné à faire place libre. J’utiliserai ici la terminologie française classique (6ème à terminale) mais des équivalents existent dans tous les pays d’Europe.

Vor fast

Vor fast

How do we know it was all a farce? Because they didn’t succeed in assassinating Castro and yet the United States is still standing! Sure, we’ve got the same types of socialist and interventionist programs that Castro has in Cuba — income taxation, Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, economic regulations, a Federal Reserve, etc. — but that’s not because Castro conquered the United States but rather because Americans love socialism and interventionism as much as Castro does.

How do we know it was all a farce? Because they didn’t succeed in assassinating Castro and yet the United States is still standing! Sure, we’ve got the same types of socialist and interventionist programs that Castro has in Cuba — income taxation, Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, economic regulations, a Federal Reserve, etc. — but that’s not because Castro conquered the United States but rather because Americans love socialism and interventionism as much as Castro does.