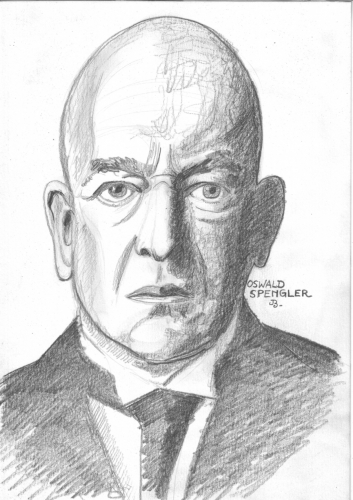

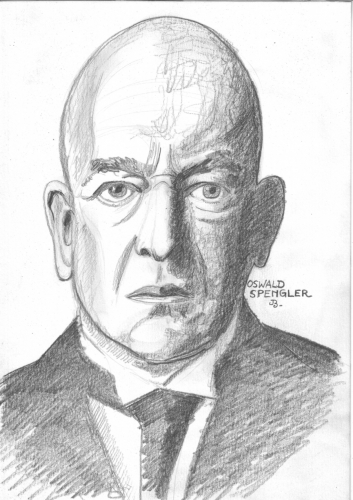

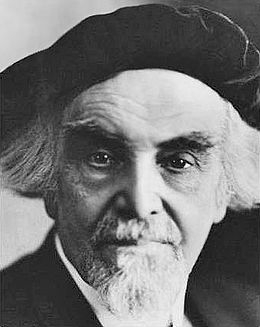

The rivalry between the USA and Russia is something more than geopolitics or economics. These are reflections of antithetical worldviews of a spiritual character. The German conservative historian-philosopher Oswald Spengler, who wrote of the morphology of cultures as having organic life-cycles, in his epochal book The Decline of The West had much to say about Russia that is too easily mistaken as being of a Russophobic nature. That is not the case, and Spengler wrote of Russia in similar terms to that of the ‘Slavophils’. Spengler, Dostoyevski, Berdyaev, and Solzhenistyn have much of relevance to say in analyzing the conflict between the USA and Russia. Considering the differences as fundamentally ‘spiritual’ explains why this conflict will continue and why the optimism among Western political circles at the prospect of a compliant Russia, fully integrated into the ‘world community’, was so short-lived.

Of the religious character of this confrontation, an American analyst, Paul Coyer, has written:

Amidst the geopolitical confrontation between Vladimir Putin’s Russia and the US and its allies, little attention has been paid to the role played by religion either as a shaper of Russian domestic politics or as a means of understanding Putin’s international actions. The role of religion has long tended to get short thrift in the study of statecraft (although it has been experiencing a bit of a renaissance of late), yet nowhere has it played a more prominent role—and perhaps nowhere has its importance been more unrecognized—than in its role in supporting the Russian state and Russia’s current place in world affairs.[1]

Russia’s ‘Soul’

Russia’s ‘Soul’

Spengler regarded Russians as formed by the vastness of the land-plain, as innately antagonistic to the Machine, as rooted in the soil, irrepressibly peasant, religious, and ‘primitive’. Without a wider understanding of Spengler’s philosophy, it appears that he was a Slavophobe. However, when Spengler wrote of these Russian characteristics, he was referring to the Russians as a still youthful people in contrast to the senile West. Hence the ‘primitive’ Russian is not synonymous with ‘primitivity’ as popularly understood at that time in regard to ‘primitive’ tribal peoples. Nor was it to be confounded with the Hitlerite perception of the ‘primitive Slav’ incapable of building his own State.

To Spengler, the ‘primitive peasant’ is the wellspring from which a people draws its healthiest elements during its epochs of cultural vigor. Agriculture is the foundation of a High Culture, enabling stable communities to diversify labor into specialization from which Civilization proceeds.

However, according to Spengler, each people has its own soul, a conception derived from the German Idealism of Herder, Fichte et al. A High Culture reflects that soul, whether in its mathematics, music, architecture; both in the arts and the physical sciences. The Russian soul is not the same as the Western Faustian, as Spengler called it, the ‘Magian’ of the Arabian civilization, or the Classical of the Hellenes and Romans. The Western Culture that was imposed on Russia by Peter the Great, what Spengler called Petrinism, is a veneer.

Spengler stated that the Russian soul is ‘the plain without limit’.[2] The Russian soul expresses its own type of infinity, albeit not that of the Westerner’s Faustian soul, which becomes enslaved by its own technics at the end of its life-cycle.[3] (Although it could be argued that Sovietism enslaved man to machine, a Spenglerian would cite this as an example of Petrinism). However, Civilizations follow their life’s course, and one cannot see Spengler’s descriptions as moral judgements but as observations. The finale for Western Civilization according to Spengler cannot be to create further great forms of art and music, which belong to the youthful or ‘spring’ epoch of a civilization, but to dominate the world under a technocratic-military dispensation, before declining into oblivion like prior world civilizations. While Spengler saw this as the fulfilment of the Western Civilization, the form it has assumed since World War II has been under U.S. dispensation and is quite different from what might have been assumed under European imperialism.

It is after this Western decline—which now means U.S. decline—that Spengler alluded to the next world civilization being Russian.

According to Spengler, Russian Orthodox architecture does not represent the infinity towards space that is symbolized by the Western high culture’s Gothic Cathedral spire, nor the enclosed space of the Mosque of the Magian Culture,[4] but the impression of sitting upon a horizon. Spengler considered that this Russian architecture is ‘not yet a style, only the promise of a style that will awaken when the real Russian religion awakens’.[5] Spengler was writing of the Russian culture as an outsider, and by his own reckoning must have realized the limitations of that. It is therefore useful to compare his thoughts on Russia with those of Russians of note.

Nikolai Berdyaev in The Russian Idea affirms what Spengler describes:

There is that in the Russian soul which corresponds to the immensity, the vagueness, the infinitude of the Russian land, spiritual geography corresponds with physical. In the Russian soul there is a sort of immensity, a vagueness, a predilection for the infinite, such as is suggested by the great plain of Russia.[6]

The connections between family, nation, birth, unity and motherland are reflected in the Russian language:

род [rod]: family, kind, sort, genus

родина [ródina]: homeland, motherland

родители [rodíteli]: parents

родить [rodít’]: to give birth

роднить [rodnít’]: to unite, bring together

родовой [rodovói]: ancestral, tribal

родство [rodstvó]: kinship

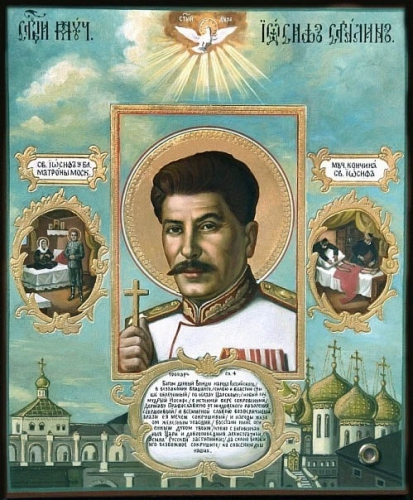

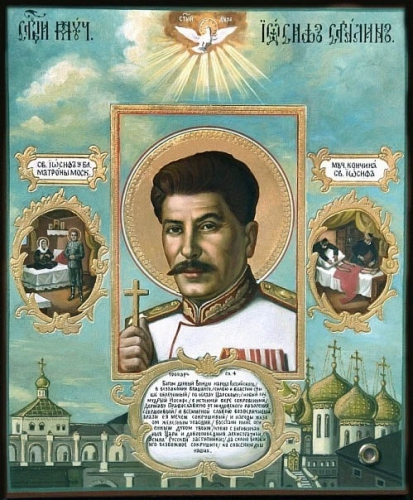

Western-liberalism, rationalism, even the most strenuous efforts of Bolshevik dialectal materialism, have so far not been able to permanently destroy, but at most repress, these conceptions—conscious or unconscious—of what it is to be ‘Russian’. Spengler, as will be seen, even during the early period of Russian Bolshevism, already predicted that even this would take on a different, even antithetical form, to the Petrine import of Marxism. It was soon that the USSR was again paying homage to Holy Mother Russia rather than the international proletariat, much to Trotsky’s lament.

‘Russian Socialism’, Not Marxism

‘Russian Socialism’, Not Marxism

Of the Russian soul, the ego/vanity of the Western culture-man is missing; the persona seeks impersonal growth in service, ‘in the brother-world of the plain’. Orthodox Christianity condemns the ‘I’ as ‘sin’.[7]

The Russian concept of ‘we’ rather than ‘I’, and of impersonal service to the expanse of one’s land, implies another form socialism to that of Marxism. It is perhaps in this sense that Stalinism proceeded along lines often antithetical to the Bolshevism envisaged by Trotsky, et al.[8] A recent comment by an American visitor to Russia, Barbara J. Brothers, as part of a scientific delegation, states something akin to Spengler’s observation:

The Russians have a sense of connectedness to themselves and to other human beings that is just not a part of American reality. It isn’t that competitiveness does not exist; it is just that there always seems to be more consideration and respect for others in any given situation.[9]

Of the Russian traditional ethos, intrinsically antithetical to Western individualism, including that of property relations, Berdyaev wrote:

Of all peoples in the world the Russians have the community spirit; in the highest degree the Russian way of life and Russian manners, are of that kind. Russian hospitality is an indication of this sense of community.[10]

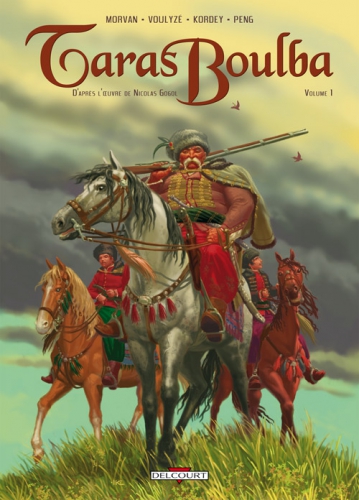

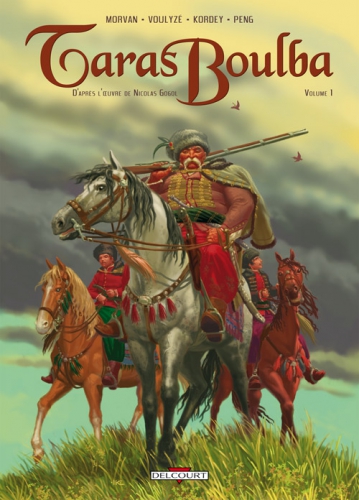

Taras Bulba

Russian National Literature starting from the 1840s began to consciously express the Russian soul. Firstly Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol’s Taras Bulba, which along with the poetry of Pushkin, founded a Russian literary tradition; that is to say, truly Russian, and distinct from the previous literature based on German, French, and English. John Cournos states of this in his introduction to Taras Bulba:

The spoken word, born of the people, gave soul and wing to literature; only by coming to earth, the native earth, was it enabled to soar. Coming up from Little Russia, the Ukraine, with Cossack blood in his veins, Gogol injected his own healthy virus into an effete body, blew his own virile spirit, the spirit of his race, into its nostrils, and gave the Russian novel its direction to this very day.

Taras Bulba is a tale on the formation of the Cossack folk. In this folk-formation the outer enemy plays a crucial role. The Russian has been formed largely as the result of battling over centuries with Tartars, Muslims and Mongols.[11]

Their society and nationality were defined by religiosity, as was the West’s by Gothic Christianity during its ‘Spring’ epoch, in Spenglerian terms. The newcomer to a Setch, or permanent village, was greeted by the Chief as a Christian and as a warrior: ‘Welcome! Do you believe in Christ?’ —‘I do’, replied the new-comer. ‘And do you believe in the Holy Trinity?’— ‘I do’.—‘And do you go to church?’—‘I do.’ ‘Now cross yourself’.[12]

Gogol depicts the scorn in which trade is held, and when commerce has entered among Russians, rather than being confined to non-Russians associated with trade, it is regarded as a symptom of decadence:

I know that baseness has now made its way into our land. Men care only to have their ricks of grain and hay, and their droves of horses, and that their mead may be safe in their cellars; they adopt, the devil only knows what Mussulman customs. They speak scornfully with their tongues. They care not to speak their real thoughts with their own countrymen. They sell their own things to their own comrades, like soulless creatures in the market-place…. . Let them know what brotherhood means on Russian soil![13]

Here we might see a Russian socialism that is, so far from being the dialectical materialism offered by Marx, the mystic we-feeling forged by the vastness of the plains and the imperative for brotherhood above economics, imposed by that landscape. Russia’s feeling of world-mission has its own form of messianism whether expressed through Christian Orthodoxy or the non-Marxian form of ‘world revolution’ under Stalin, or both in combination, as suggested by the later rapport between Stalinism and the Church from 1943 with the creation of the Council for Russian Orthodox Church Affairs.[14] In both senses, and even in the embryonic forms taking place under Putin, Russia is conscious of a world-mission, expressed today as Russia’s role in forging a multipolar world, with Russia as being pivotal in resisting unipolarism.

Commerce is the concern of foreigners, and the intrusions bring with them the corruption of the Russian soul and culture in general: in speech, social interaction, servility, undermining Russian ‘brotherhood’, the Russian ‘we’ feeling that Spengler described.[15]

The Cossack brotherhood is portrayed by Gogol as the formative process in the building up of the Russian people. This process is not one of biology but of spirit, even transcending the family bond. Spengler treated the matter of race as that of soul rather than of zoology.[16] To Spengler, landscape was crucial in determining what becomes ‘race’, and the duration of families grouped in a particular landscape—including nomads who have a defined range of wandering—form ‘a character of duration’, which was Spengler’s definition of ‘race’.[17] Gogol describes this ‘race’ forming process among the Russians. So far from being an aggressive race nationalism it is an expanding mystic brotherhood under God:

The father loves his children, the mother loves her children, the children love their father and mother; but this is not like that, brothers. The wild beast also loves its young. But a man can be related only by similarity of mind and not of blood. There have been brotherhoods in other lands, but never any such brotherhoods as on our Russian soil.[18]

The Russian soul is born in suffering. The Russian accepts the fate of life in service to God and to his Motherland. Russia and Faith are inseparable. When the elderly warrior Bovdug is mortally struck by a Turkish bullet, his final words are exhortations on the nobility of suffering, after which his spirit soars to join his ancestors.[19] The mystique of death and suffering for the Motherland is described in the death of Tarus Bulba when he is captured and executed, his final words being ones of resurrection:

‘Wait, the time will come when ye shall learn what the orthodox Russian faith is! Already the people scent it far and near. A czar shall arise from Russian soil, and there shall not be a power in the world which shall not submit to him!’[20]

Petrinism

A dichotomy has existed for centuries, starting with Peter the Great, of attempts to impose a Western veneer over Russia. This is called Petrinism. The resistance of those attempts is what Spengler called ‘Old Russia’.[21] Berdyaev wrote: ‘Russia is a complete section of the world, a colossal East-West. It unites two worlds, and within the Russian soul two principles are always engaged in strife—the Eastern and the Western’.[22]

With the orientation of Russian policy towards the West, ‘Old Russia’ was ‘forced into a false and artificial history’.[23] Spengler wrote that Russia had become dominated by Late Western culture:

Late-period arts and sciences, enlightenment, social ethics, the materialism of world-cities, were introduced, although in this pre-cultural time religion was the only language in which man understood himself and the world.[24]

‘The first condition of emancipation for the Russian soul’, wrote Ivan Sergyeyevich Aksakov, founder of the anti-Petrinist ‘Slavophil’ group, in 1863 to Dostoyevski, ‘is that it should hate Petersburg with all this might and all its soul’. Moscow is holy, Petersburg satanic. A widespread popular legend presents Peter the Great as Antichrist.

‘The first condition of emancipation for the Russian soul’, wrote Ivan Sergyeyevich Aksakov, founder of the anti-Petrinist ‘Slavophil’ group, in 1863 to Dostoyevski, ‘is that it should hate Petersburg with all this might and all its soul’. Moscow is holy, Petersburg satanic. A widespread popular legend presents Peter the Great as Antichrist.

The hatred of the ‘West’ and of ‘Europe’ is the hatred for a Civilization that had already reached an advanced state of decay into materialism and sought to impose its primacy by cultural subversion rather than by combat, with its City-based and money-based outlook, ‘poisoning the unborn culture in the womb of the land’.[25] Russia was still a land where there were no bourgeoisie and no true class system, but only lord and peasant, a view confirmed by Berdyaev, writing: ‘The various lines of social demarcation did not exist in Russia; there were no pronounced classes. Russia was never an aristocratic country in the Western sense, and equally there was no bourgeoisie’.[26]

The cities that emerged threw up an intelligentsia, copying the intelligentsia of Late Westerndom, ‘bent on discovering problems and conflicts, and below, an uprooted peasantry, with all the metaphysical gloom, anxiety, and misery of their own Dostoyevski, perpetually homesick for the open land and bitterly hating the stony grey world into which the Antichrist had tempted them. Moscow had no proper soul’.[27] Berdyaev likewise states of the Petrinism of the upper class that ‘Russian history was a struggle between East and West within the Russian soul’.[28]

Katechon

Katechon

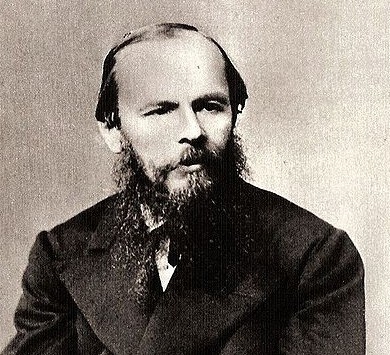

Berdyaev states that while Petrinism introduced an epoch of cultural dynamism, it also placed a heavy burden upon Russia, and a disunity of spirit.[29] However, Russia has her own religious sense of mission, which is as universal as the Vatican’s. Spengler quotes Dostoyevski as writing in 1878: ‘all men must become Russian, first and foremost Russian. If general humanity is the Russian ideal, then everyone must first of all become a Russian’.[30] The Russian messianic idea found a forceful expression in Dostoyevski’s The Possessed, where, in a conversation with Stavrogin, Shatov states:

Reduce God to the attribute of nationality? … On the contrary, I elevate the nation to God…. The people is the body of God. Every nation is a nation only so long as it has its own particular God, excluding all other gods on earth without any possible reconciliation, so long as it believes that by its own God it will conquer and drive all other gods off the face of the earth…. The sole ‘God bearing’ nation is the Russian nation….[31]

This is Russia as the Katechon, as the ‘nation’ whose world-historical mission is to resist the son of perdition, a literal Anti-Christ, according to the Revelation of St. John, or as the birthplace of a great Czar serving the traditional role of nexus between the terrestrial and the divine around which Russia is united in this mission. This mission as the Katechon defines Russia as something more than merely an ethno-nation-state, as Dostoyevski expressed it.[32] Even the USSR, supposedly purged of all such notions, merely re-expressed them with Marxist rhetoric, which was no less apocalyptic and messianic, and which saw the ‘decadent West’ in terms analogous to elements of Islam regarding the USA as the ‘Great Satan’. It is not surprising that the pundits of secularized, liberal Western academia, politics, and media could not understand, and indeed were outraged, when Solzhenitsyn seemed so ungrateful when in his Western exile he unequivocally condemned the liberalism and materialism of the a ‘decadent West’. A figure who was for so long held up as a martyr by Western liberalism transpired to be a traditional Russian and not someone who was willing to remake himself in the image of a Western liberal to for the sake of continued plaudits. He attacked the modern West’s conceptions of ‘rights’, ‘freedom’, ‘happiness’, ‘wealth’, the irresponsibility of the ‘free press’, ‘television stupor’, and referred to a ‘Western decline’ in courage. He emphasized that this was a spiritual matter:

But should I be asked, instead, whether I would propose the West, such as it is today, as a model to my country, I would frankly have to answer negatively. No, I could not recommend your society as an ideal for the transformation of ours. Through deep suffering, people in our own country have now achieved a spiritual development of such intensity that the Western system in its present state of spiritual exhaustion does not look attractive. Even those characteristics of your life which I have just enumerated are extremely saddening.[33]

These are all matters that have been addressed by Spengler, and by traditional Russians, whether calling themselves Czarists Orthodox Christians or even ‘Bolsheviks’ or followers of Putin.

Spengler’s thesis that Western Civilization is in decay is analogous to the more mystical evaluations of the West by the Slavophils, both reaching similar conclusions. Solzhenitsyn was in that tradition, and Putin is influenced by it in his condemnation of Western liberalism. Putin recently pointed out the differences between the West and Russia as at root being ‘moral’ and religious:

Another serious challenge to Russia’s identity is linked to events taking place in the world. Here there are both foreign policy and moral aspects. We can see how many of the Euro-Atlantic countries are actually rejecting their roots, including the Christian values that constitute the basis of Western civilization. They are denying moral principles and all traditional identities: national, cultural, religious and even sexual.[34]

Spengler saw Russia as outside of Europe, and even as ‘Asian’. He even saw a Western rebirth vis-à-vis opposition to Russia, which he regarded as leading the ‘colored world’ against the whites, under the mantle of Bolshevism. Yet there were also other destinies that Spengler saw over the horizon, which had been predicted by Dostoyevski.

Once Russia had overthrown its alien intrusions, it could look with another perspective upon the world, and reconsider Europe not with hatred and vengeance but in kinship. Spengler wrote that while Tolstoi, the Petrinist, whose doctrine was the precursor of Bolshevism, was ‘the former Russia’, Dostoyevski was ‘the coming Russia’. Dostoyevski as the representative of the ‘coming Russia’ ‘does not know’ the hatred of Russia for the West. Dostoyevski and the old Russia are transcendent. ‘His passionate power of living is comprehensive enough to embrace all things Western as well’. Spengler quotes Dostoyevski: ‘I have two fatherlands, Russia and Europe’. Dostoyevski as the harbinger of a Russian high culture ‘has passed beyond both Petrinism and revolution, and from his future he looks back over them as from afar. His soul is apocalyptic, yearning, desperate, but of this future he is certain’.[35]

To the ‘Slavophil’, Europe is precious. The Slavophil appreciates the richness of European high culture while realizing that Europe is in a state of decay. We might recall that while the USA—through the CIA front, the Congress for Cultural Freedom—promoted Abstract Expressionism and Jazz to Europe (like it now promotes Hi-Hop, which the State Department calls ‘Hip-Hop diplomacy’), the USSR condemned this as ‘rootless cosmopolitanism’. Berdyaev discussed what he regarded as an inconsistency in Dostoyevski and the Slavophils towards Europe, yet one that is comprehensible when we consider Spengler’s crucial differentiation between Culture and Civilisation:

Dostoyevsky calls himself a Slavophil. He thought, as did also a large number of thinkers on the theme of Russia and Europe, that he knew decay was setting in, but that a great past exists in her, and that she has made contributions of great value to the history of mankind.[36]

It is notable that while this differentiation between Kultur and Zivilisation is ascribed to a particularly German philosophical tradition, Berdyaev comments that it was present among the Russians ‘long before Spengler’:

It is to be noted that long before Spengler, the Russians drew the distinction between ‘culture’ and ‘civilization’, that they attacked ‘civilization’ even when they remained supporters of ‘culture’. This distinction in actual fact, although expressed in a different phraseology, was to be found among the Slavophils.[37]

Dostoyevski was indifferent to the Late West, while Tolstoi was a product of it, the Russian Rousseau. Imbued with ideas from the Late West, the Marxists sought to replace one Petrine ruling class with another. Neither represented the soul of Russia. Spengler stated: ‘The real Russian is the disciple of Dostoyevski, even though he might not have read Dostoyevski, or anyone else, nay, perhaps because he cannot read, he is himself Dostoyevski in substance’. The intelligentsia hates, the peasant does not. He would eventually overthrow Bolshevism and any other form of Petrinism. Here we see Spengler unequivocally stating that the post-Western civilisation will be Russian.

Dostoyevski was indifferent to the Late West, while Tolstoi was a product of it, the Russian Rousseau. Imbued with ideas from the Late West, the Marxists sought to replace one Petrine ruling class with another. Neither represented the soul of Russia. Spengler stated: ‘The real Russian is the disciple of Dostoyevski, even though he might not have read Dostoyevski, or anyone else, nay, perhaps because he cannot read, he is himself Dostoyevski in substance’. The intelligentsia hates, the peasant does not. He would eventually overthrow Bolshevism and any other form of Petrinism. Here we see Spengler unequivocally stating that the post-Western civilisation will be Russian.

For what this townless people yearns for is its own life-form, its own religion, its own history. Tolstoi’s Christianity was a misunderstanding. He spoke of Christ and he meant Marx. But to Dostoyevski’s Christianity, the next thousand years will belong.[38]

To the true Russia, as Dostoyevski stated it, ‘not a single nation has ever been founded on principles of science or reason’.[39]

By the time Spengler’s final book, The Hour of Decision, had been published in 1934 he was stating that Russia had overthrown Petrinism and the trappings of the Late West. While he called the new orientation of Russia ‘Asian’, he said that it was ‘a new Idea, and an idea with a future too’.[40] To clarify, Russia looks towards the ‘East’, but while the Westerner assumes that ‘Asia’ and East are synonymous with Mongol, the etymology of the word ‘Asia’ comes from Greek Aσία, ca. 440 BC, referring to all regions east of Greece.[41] During his time Spengler saw in Russia that,

Race, language, popular customs, religion, in their present form… all or any of them can and will be fundamentally transformed. What we see today then is simply the new kind of life which a vast land has conceived and will presently bring forth. It is not definable in words, nor is its bearer aware of it. Those who attempt to define, establish, lay down a program, are confusing life with a phrase, as does the ruling Bolshevism, which is not sufficiently conscious of its own West-European, Rationalistic and cosmopolitan origin.[42]

Of Russia in 1934, Spengler already saw that ‘of genuine Marxism there is very little except in names and programs’. He doubted that the Communist program is ‘really still taken seriously’. He saw the possibility of the vestiges of Petrine Bolshevism being overthrown, to be replaced by a ‘nationalistic’ Eastern type which would reach ‘gigantic proportions unchecked’.[43] Spengler also referred to Russia as the country ‘least troubled by Bolshevism’,[44] and the ‘Marxian face [was] only worn for the benefit of the outside world’.[45] A decade after Spengler’s death the direction of Russia under Stalin had pursued clearer definitions, and Petrine Bolshevism had been transformed in the way Spengler foresaw.[46]

Conclusion

As in Spengler’s time, and centuries before, there continues to exist two tendencies in Russia : the Old Russian and the Petrine. Neither one nor the other spirit is presently dominant, although under Putin Old Russia struggles for resurgence. U.S. political circles see this Russia as a threat, and expend a great deal on promoting ‘regime change’ via the National Endowment for Democracy, and many others; these activities recently bringing reaction from the Putin government against such NGOs.[47]

Spengler in a published lecture to the Rheinish-Westphalian Business Convention in 1922 referred to the ‘ancient, instinctive, unclear, unconscious, and subliminal drive that is present in every Russian, no matter how thoroughly westernized his conscious life may be—a mystical yearning for the South, for Constantinople and Jerusalem, a genuine crusading spirit similar to the spirit our Gothic forebears had in their blood but which we can hardly appreciated today’.[48]

Bolshevism destroyed one form of Petrinism with another form, clearing the way ‘for a new culture that will some day arise between Europe and East Asia. It is more a beginning than an end’. The peasantry ‘will some day become conscious of its own will, which points in a wholly different direction’. ‘The peasantry is the true Russian people of the future. It will not allow itself to be perverted or suffocated’.[49]

The arch-Conservative anti-Marxist, Spengler, in keeping with the German tradition of realpolitik, considered the possibility of a Russo-German alliance in his 1922 speech, the Treaty of Rapallo being a reflection of that tradition. ‘A new type of leader’ would be awakened in adversity, to ‘new crusades and legendary conquests’. The rest of the world, filled with religious yearning but falling on infertile ground, is ‘torn and tired enough to allow it suddenly to take on a new character under the proper circumstances’. Spengler suggested that ‘perhaps Bolshevism itself will change in this way under new leaders’. ‘But the silent, deeper Russia,’ would turn its attention towards the Near and East Asia, as a people of ‘great inland expanses’.[50]

While Spengler postulated the organic cycles of a High Culture going through the life-phases of birth, youthful vigor, maturity, old age and death, it should be kept in mind that a life-cycle can be disrupted, aborted, murdered or struck by disease, at any time, and end without fulfilling itself. Each has its analogy in politics, and there are plenty of Russophobes eager to stunt Russia’s destiny with political, economic and cultural contagion. The Soviet bloc fell through inner and outer contagion.

Spengler foresaw new possibilities for Russia, yet to fulfil its historic mission, messianic and of world-scope, a traditional mission of which Putin seems conscious, or at least willing to play his part. Coyer cogently states: ‘The conflict between Russia and the West, therefore, is portrayed by both the Russian Orthodox Church and by Vladimir Putin and his cohorts as nothing less than a spiritual/civilizational conflict’.[51]

The invigoration of Orthodoxy is part of this process, as is the leadership style of Putin, as distinct from a Yeltsin for example. Whatever Russia is called outwardly, whether, monarchical, Bolshevik, or democratic, there is an inner—eternal—Russia that is unfolding, and whose embryonic character places her on an antithetical course to that of the USA.

References

[1] Paul Coyer, (Un)Holy Alliance: Vladimir Putin, The Russian Orthodox Church And Russian Exceptionalism, Forbes, May 21, 2015, http://www.forbes.com/sites/paulcoyer/2015/05/21/unholy-a...

[2] Oswald Spengler, The Decline of The West, George Allen & Unwin, London, 1971, Vol. I, 201.

[3] Ibid., Vol. II, 502.

[4] Ibid., Vol. I, 183-216.

[5] Ibid., 201

[6] Nikolai Berdyaev, The Russian Idea, Macmillan Co., New York, 1948, 1.

[7] Oswald Spengler, The Decline, op. cit., Vol. I, 309.

[8] Leon Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed: what is the Soviet Union and where is it going?, 1936.

[9] Barbara J. Brothers, From Russia, With Soul, Psychology Today, January 1, 1993, https://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/199301/russia-soul

[10] Berdyaev, op. cit., 97-98.

[11] H Cournos,‘Introduction’, N V Gogol, Taras Bulba & Other Tales, 1842, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1197/1197-h/1197-h.htm

[12] N V Gogol, ibid., III.

[13] Ibid.

[14] T A Chumachenko, Church and State in Soviet Russia, M. E. Sharpe Inc., New York, 2002.

[15] Spengler, The Decline, op. cit., I, 309

[16] Ibid., II, 113-155.

[17] Ibid., Vol. II, 113

[18] Golgol, op. cit., IX.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid., XII.

[21] Spengler, The Decline, op. cit., II, 192.

[22] Berdyaev, op. cit., 1

[23] Spengler, The Decline, op. cit., II, 193

[24] Ibid., II, 193

[25] Ibid., II, 194

[26] Berdyaev, 1

[27] Spengler, The Decline, op. cit., II, 194

[28] Berdyaev, op. cit., 15

[29] Ibid.

[30] Spengler, The Hour of Decision, Alfred A Knopf, New York, 1963, 63n.

[31] Fyodor Dostoevski, The Possessed, Oxford University Press, 1992, Part II: I: 7, 265-266.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Alexander Solzhenitsyn, A World Split Apart — Commencement Address Delivered At Harvard University, June 8, 1978

[34] V Putin, address to the Valdai Club, 19 September 2013.

[35] Spengler, The Decline, op. cit., II, 194

[36] Berdyaev, op. cit., 70

[37] Ibid.

[38] Spengler, The Decline, op. cit., Vol. II, 196

[39] Dostoyevski, op. cit., II: I: VII

[40] Spengler, The Hour of Decision, Alfred A Knopf, New York, 1963, 60

[41] Ibid., 61

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid., 63.

[44] Ibid.,182

[45] Ibid., 212

[46] D Brandenberger, National Bolshevism: Stalinist culture and the Formation of Modern Russian National Identity 1931-1956. Harvard University Press, Massachusetts, 2002.

[47] Telegraph, Vladimir Putin signs new law against ‘undesirable NGOs’, May 24, 2015, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/russia/1...

[48] Spengler, ‘The Two Faces of Russia and Germany’s Eastern Problems’, Politische Schriften, Munich, February 14, 1922.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Paul Coyer, op. cit.

Dans Qu’est-ce le Tiers-État ? Sieyès montre que la Révolution française de 1789 fut l’expression de la révolte des Gallo-Romains asservis contre les nobles Franks — qui représentaient à peine 2% de la population. Napoléon Bonaparte était un Frank de la petite noblesse de Toscane qui avait pu suivre une école d’officiers. Il usurpa la Révolution des Gallo- Romains et la retourna au bénéfice des Franks. Près de neuf mille officiers franks, en grande majorité issus de la petite noblesse, appartenant à vingt cinq loges militaires de la franc-maçonnerie, participèrent à la Révolution française aux côtés des Gallo-Romains. Ces officiers, payés avec l’argent de l’impôt que le roi prélevait sur la classe moyenne et non plus par l’attribution de fiefs, comme cela s’était fait durant des siècles jusqu’au quinzième, prétendaient devenir les égaux de la haute noblesse. Cette dernière, avec la royauté, possédait en effet les grandes propriétés foncières. Les officiers franks, ainsi acculés à une pauvreté relative eu égard à leurs richissimes confrères, surent utiliser la révolte du peuple gallo-romain pour confisquer le pouvoir. Napoléon était de ceux-là.

Dans Qu’est-ce le Tiers-État ? Sieyès montre que la Révolution française de 1789 fut l’expression de la révolte des Gallo-Romains asservis contre les nobles Franks — qui représentaient à peine 2% de la population. Napoléon Bonaparte était un Frank de la petite noblesse de Toscane qui avait pu suivre une école d’officiers. Il usurpa la Révolution des Gallo- Romains et la retourna au bénéfice des Franks. Près de neuf mille officiers franks, en grande majorité issus de la petite noblesse, appartenant à vingt cinq loges militaires de la franc-maçonnerie, participèrent à la Révolution française aux côtés des Gallo-Romains. Ces officiers, payés avec l’argent de l’impôt que le roi prélevait sur la classe moyenne et non plus par l’attribution de fiefs, comme cela s’était fait durant des siècles jusqu’au quinzième, prétendaient devenir les égaux de la haute noblesse. Cette dernière, avec la royauté, possédait en effet les grandes propriétés foncières. Les officiers franks, ainsi acculés à une pauvreté relative eu égard à leurs richissimes confrères, surent utiliser la révolte du peuple gallo-romain pour confisquer le pouvoir. Napoléon était de ceux-là.

Mevrouw, mijnheer,

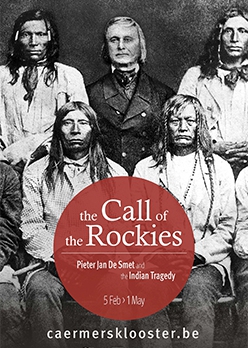

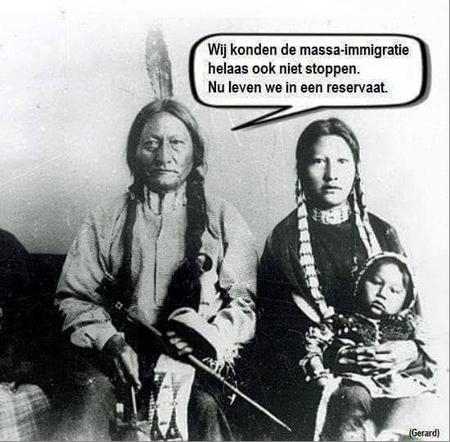

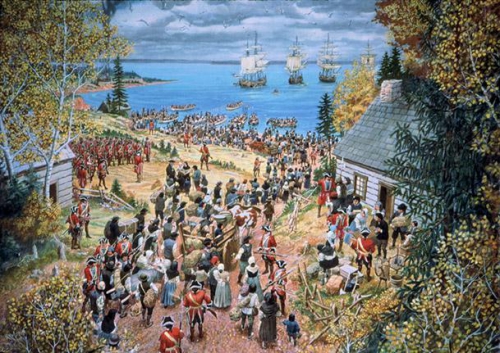

Mevrouw, mijnheer, Vanaf de tweede helft van de negentiende eeuw, toen de migratie tsunami steeds verder naar het westen trok, was het lot van de Indianen bezegeld. Ze werden systematisch van hun gronden verjaagd, bizons die de basisvoeding van bepaalde stammen waren, werden massaal uitgeroeid en vaak de Indianen zelf ook. Uiteindelijk kwamen ze in reservaten terecht die hen door de bezetters van hun land werden toebedeeld. Op enkele uitzonderingen na leiden ze er een soort vegetatief en vrij doelloos bestaan. Hun oorspronkelijke cultuur wordt er bovendien gereduceerd tot een soort folklore waarmee toeristen kunnen worden geëntertaind en soms zelfs tot min of meer spectaculaire circusattracties (dat was al zo in de tijd van Buffalo Bill). De Indianen werden overigens nooit opgenomen in de Amerikaanse melting pot maatschappij want in die smeltkroes van immigranten van over gans de wereld horen zij als enige echte autochtonen niet thuis.

Vanaf de tweede helft van de negentiende eeuw, toen de migratie tsunami steeds verder naar het westen trok, was het lot van de Indianen bezegeld. Ze werden systematisch van hun gronden verjaagd, bizons die de basisvoeding van bepaalde stammen waren, werden massaal uitgeroeid en vaak de Indianen zelf ook. Uiteindelijk kwamen ze in reservaten terecht die hen door de bezetters van hun land werden toebedeeld. Op enkele uitzonderingen na leiden ze er een soort vegetatief en vrij doelloos bestaan. Hun oorspronkelijke cultuur wordt er bovendien gereduceerd tot een soort folklore waarmee toeristen kunnen worden geëntertaind en soms zelfs tot min of meer spectaculaire circusattracties (dat was al zo in de tijd van Buffalo Bill). De Indianen werden overigens nooit opgenomen in de Amerikaanse melting pot maatschappij want in die smeltkroes van immigranten van over gans de wereld horen zij als enige echte autochtonen niet thuis.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

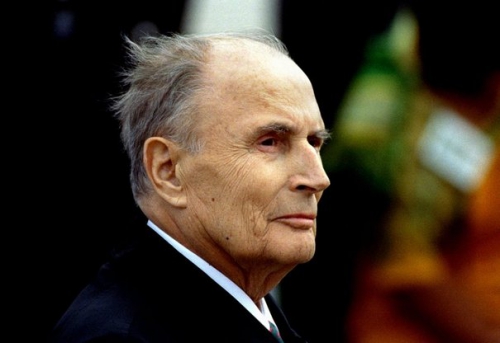

Naguère, nous avions évoqué dans cette rubrique française l’avalanche de livres récemment publiés à l’occasion du vingtième anniversaire du décès de l’ancien Président français François Mitterrand. Dans cette masse de bouquins, un seul n’a pas vraiment été recensés mais il mérite une attention toute particulière : Dites-leur que je ne suis pas le diable (Plon, 2016, 188 p.). Ce livre est dû à la plume de Georges-Marc Benamou. Ce journaliste a suivi Mitterrand de très près au cours des dernières années de sa vie. Juste après la mort du Président, Benamou avait écrit Mémoires interrompues, soit les mémoires incomplètes de Mitterrand. En 1997, parait Le dernier Mitterrand, ouvrage consacré aux mille derniers jours de la vie du président socialiste. Dites-leur que je ne suis pas le diable en est une sorte de complément. On y trouve un florilège de commentaires et d’analyses posés par Mitterrand dans ses dernières années. Il s’agit de citations non encore publiées à ce jour. Benamou analyse en profondeur une série de controverses relatives au Mitterrand âgé, malade et mourant. Ainsi, Benamou analyse la dernière allocution de Mitterrand à la télévision, à la fin de l’année 1994. Mitterrand avait dit qu’il « croyait en les forces de l’esprit ». Et qu’à la fin de l’année 1995, il écouterait le message du Nouvel An du nouveau Président du « lieu où il se trouverait ». Ce fut donc un discours à connotations religieuses évidentes. En France, où l’église et l’Etat sont strictement séparés, ce ton religieux était inédit. Mitterrand avait éprouvé du plaisir en assistant au tollé que son discours avait suscité. « Vous avez vu ? », demandait à Benamou un Mitterrand rigolard, « j’ai osé ! ». A la fin de sa vie, Mitterrand était fasciné par la mort. Ou mieux : par le passage de la vie après la mort. Il en parlait à des médecins, des philosophes, des théologiens.

Naguère, nous avions évoqué dans cette rubrique française l’avalanche de livres récemment publiés à l’occasion du vingtième anniversaire du décès de l’ancien Président français François Mitterrand. Dans cette masse de bouquins, un seul n’a pas vraiment été recensés mais il mérite une attention toute particulière : Dites-leur que je ne suis pas le diable (Plon, 2016, 188 p.). Ce livre est dû à la plume de Georges-Marc Benamou. Ce journaliste a suivi Mitterrand de très près au cours des dernières années de sa vie. Juste après la mort du Président, Benamou avait écrit Mémoires interrompues, soit les mémoires incomplètes de Mitterrand. En 1997, parait Le dernier Mitterrand, ouvrage consacré aux mille derniers jours de la vie du président socialiste. Dites-leur que je ne suis pas le diable en est une sorte de complément. On y trouve un florilège de commentaires et d’analyses posés par Mitterrand dans ses dernières années. Il s’agit de citations non encore publiées à ce jour. Benamou analyse en profondeur une série de controverses relatives au Mitterrand âgé, malade et mourant. Ainsi, Benamou analyse la dernière allocution de Mitterrand à la télévision, à la fin de l’année 1994. Mitterrand avait dit qu’il « croyait en les forces de l’esprit ». Et qu’à la fin de l’année 1995, il écouterait le message du Nouvel An du nouveau Président du « lieu où il se trouverait ». Ce fut donc un discours à connotations religieuses évidentes. En France, où l’église et l’Etat sont strictement séparés, ce ton religieux était inédit. Mitterrand avait éprouvé du plaisir en assistant au tollé que son discours avait suscité. « Vous avez vu ? », demandait à Benamou un Mitterrand rigolard, « j’ai osé ! ». A la fin de sa vie, Mitterrand était fasciné par la mort. Ou mieux : par le passage de la vie après la mort. Il en parlait à des médecins, des philosophes, des théologiens.

Cette délicatesse du dernier repas de Mitterrand consistait en ortolans. Ce sont de petits oiseaux que l’on capture, que l’on engraisse et puis que l’on noie vivants dans l’armagnac. Ils sont ensuite rôtis au four. On doit les manger tout entiers, os et viscères compris. Pour manger ce met de manière traditionnelle, on doit se pencher sur le récipient contenant les ortolans, se placer une serviette sur la tête pour se régaler des odeurs de l’armagnac.

Cette délicatesse du dernier repas de Mitterrand consistait en ortolans. Ce sont de petits oiseaux que l’on capture, que l’on engraisse et puis que l’on noie vivants dans l’armagnac. Ils sont ensuite rôtis au four. On doit les manger tout entiers, os et viscères compris. Pour manger ce met de manière traditionnelle, on doit se pencher sur le récipient contenant les ortolans, se placer une serviette sur la tête pour se régaler des odeurs de l’armagnac. Mitterrand n’aurait pas été lui-même s’il n’avait pas donné, en ses heures ultimes, quelques coups de canifs, bien acérés, à la classe politique. Le livre Dites-leur que je ne suis pas le diable contient quelques belles perles à ce niveau. Quand il s’agit du PS, Mitterrand est vraiment assassin. Dans le lot des socialistes français, il ne voit personne capable de lui succéder. Il ne cite même pas le Président actuel, François Hollande. Les dirigeants du PS sont, selon les Mitterrand des derniers mois, des « avocats de province », ce qu’il était lui-même dans ses jeunes années, dans sa Charente natale. En 1995, lors des Présidentielles, il a soutenu implicitement le néo-gaulliste Jacques Chirac contre le candidat socialiste Lionel Jospin. Mitterrand n’avait pas une haute opinion des autres dirigeants socialistes, comme Pierre Mendès-France. Quant à l’agitation gauchiste de mai 68, il eut ces mots : « Tous des fous ! » ou « Des enfants gâtés de la petite bourgeoisie catholique ».

Mitterrand n’aurait pas été lui-même s’il n’avait pas donné, en ses heures ultimes, quelques coups de canifs, bien acérés, à la classe politique. Le livre Dites-leur que je ne suis pas le diable contient quelques belles perles à ce niveau. Quand il s’agit du PS, Mitterrand est vraiment assassin. Dans le lot des socialistes français, il ne voit personne capable de lui succéder. Il ne cite même pas le Président actuel, François Hollande. Les dirigeants du PS sont, selon les Mitterrand des derniers mois, des « avocats de province », ce qu’il était lui-même dans ses jeunes années, dans sa Charente natale. En 1995, lors des Présidentielles, il a soutenu implicitement le néo-gaulliste Jacques Chirac contre le candidat socialiste Lionel Jospin. Mitterrand n’avait pas une haute opinion des autres dirigeants socialistes, comme Pierre Mendès-France. Quant à l’agitation gauchiste de mai 68, il eut ces mots : « Tous des fous ! » ou « Des enfants gâtés de la petite bourgeoisie catholique ».

John Calvin (1509-1564) appeared as a player on the historical stage during an intense developmental period for Western civilization. The Roman Catholic Church had wielded power in the West for over a millennium, and during that time it had become increasingly corrupt as an institution – so much so that by the 16th century the Church hierarchy was funded (to a large degree) by a direct marketing scheme known as “indulgences.” How the indulgences worked were as follows: No matter how grievously someone might have “sinned,” one could buy a piece of paper signed by either a Bishop or a Cardinal, which guaranteed a place in heaven for that particular person or a loved one of the person’s own choosing. These “get-out-of-hell-free” cards were sold by members of the clergy through franchises granted by the Church hierarchy. The typical indulgence erased one’s previous sins, but for a larger fee there was a twisted kind of“super”indulgence which erased any future sins one might commit as well, no matter how great or blasphemous.

John Calvin (1509-1564) appeared as a player on the historical stage during an intense developmental period for Western civilization. The Roman Catholic Church had wielded power in the West for over a millennium, and during that time it had become increasingly corrupt as an institution – so much so that by the 16th century the Church hierarchy was funded (to a large degree) by a direct marketing scheme known as “indulgences.” How the indulgences worked were as follows: No matter how grievously someone might have “sinned,” one could buy a piece of paper signed by either a Bishop or a Cardinal, which guaranteed a place in heaven for that particular person or a loved one of the person’s own choosing. These “get-out-of-hell-free” cards were sold by members of the clergy through franchises granted by the Church hierarchy. The typical indulgence erased one’s previous sins, but for a larger fee there was a twisted kind of“super”indulgence which erased any future sins one might commit as well, no matter how great or blasphemous.

Russia’s ‘Soul’

Russia’s ‘Soul’ ‘Russian Socialism’, Not Marxism

‘Russian Socialism’, Not Marxism

‘The first condition of emancipation for the Russian soul’, wrote Ivan Sergyeyevich Aksakov, founder of the anti-Petrinist ‘Slavophil’ group, in 1863 to Dostoyevski, ‘is that it should hate Petersburg with all this might and all its soul’. Moscow is holy, Petersburg satanic. A widespread popular legend presents Peter the Great as Antichrist.

‘The first condition of emancipation for the Russian soul’, wrote Ivan Sergyeyevich Aksakov, founder of the anti-Petrinist ‘Slavophil’ group, in 1863 to Dostoyevski, ‘is that it should hate Petersburg with all this might and all its soul’. Moscow is holy, Petersburg satanic. A widespread popular legend presents Peter the Great as Antichrist. Katechon

Katechon Dostoyevski was indifferent to the Late West, while Tolstoi was a product of it, the Russian Rousseau. Imbued with ideas from the Late West, the Marxists sought to replace one Petrine ruling class with another. Neither represented the soul of Russia. Spengler stated: ‘The real Russian is the disciple of Dostoyevski, even though he might not have read Dostoyevski, or anyone else, nay, perhaps because he cannot read, he is himself Dostoyevski in substance’. The intelligentsia hates, the peasant does not. He would eventually overthrow Bolshevism and any other form of Petrinism. Here we see Spengler unequivocally stating that the post-Western civilisation will be Russian.

Dostoyevski was indifferent to the Late West, while Tolstoi was a product of it, the Russian Rousseau. Imbued with ideas from the Late West, the Marxists sought to replace one Petrine ruling class with another. Neither represented the soul of Russia. Spengler stated: ‘The real Russian is the disciple of Dostoyevski, even though he might not have read Dostoyevski, or anyone else, nay, perhaps because he cannot read, he is himself Dostoyevski in substance’. The intelligentsia hates, the peasant does not. He would eventually overthrow Bolshevism and any other form of Petrinism. Here we see Spengler unequivocally stating that the post-Western civilisation will be Russian. En 1915, Maurice Genevoix, jeune lieutenant de l'armée française, échappe de justesse à la mort. On est à Verdun, sur le front des Eparges. Choqué, meurtri, révolté, mais nourri par la beauté de ses hommes, leur bravoure, leurs souffrances, leurs doutes, leurs peurs, il n'aura de cesse toute sa vie de chanter un hymne à la vie, jailli du fond des tranchées boueuses.

En 1915, Maurice Genevoix, jeune lieutenant de l'armée française, échappe de justesse à la mort. On est à Verdun, sur le front des Eparges. Choqué, meurtri, révolté, mais nourri par la beauté de ses hommes, leur bravoure, leurs souffrances, leurs doutes, leurs peurs, il n'aura de cesse toute sa vie de chanter un hymne à la vie, jailli du fond des tranchées boueuses.

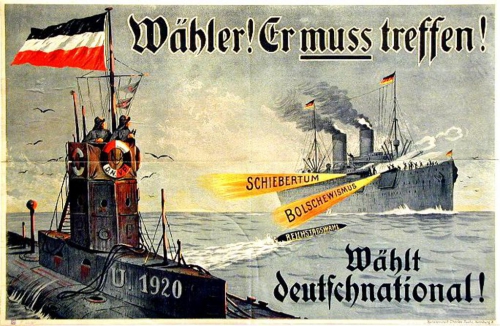

En effet, il me paraît très important de replacer la révolution conservatrice allemande dans un contexte temporel plus vaste et plus profond, comme d’ailleurs Armin Mohler lui-même l’avait envisagé, suite à la publication des travaux de Zeev Sternhell sur la droite révolutionnaire française d’après 1870, qui représente une réaction musclée, une volonté de redresser la nation vaincue : après la défaite de 1918 et le Traité de Versailles de juin 1919, c’est ce modèle français qu’évoquait explicitement l’Alsacien Eduard Stadtler, un ultra-nationaliste allemand, bilingue, issu du Zentrum démocrate-chrétien, fondateur du Stahlhelm paramilitaire et compagnon de Moeller van den Bruck dans son combat métapolitique de 1918 à 1925. L’Allemagne devait susciter en son sein l’émergence d’un réseau de cercles intellectuels et politiques, d’associations diverses, de sociétés de pensée et de groupes paramilitaires pour redonner au Reich vaincu un statut de pleine souveraineté sur la scène européenne et internationale.

En effet, il me paraît très important de replacer la révolution conservatrice allemande dans un contexte temporel plus vaste et plus profond, comme d’ailleurs Armin Mohler lui-même l’avait envisagé, suite à la publication des travaux de Zeev Sternhell sur la droite révolutionnaire française d’après 1870, qui représente une réaction musclée, une volonté de redresser la nation vaincue : après la défaite de 1918 et le Traité de Versailles de juin 1919, c’est ce modèle français qu’évoquait explicitement l’Alsacien Eduard Stadtler, un ultra-nationaliste allemand, bilingue, issu du Zentrum démocrate-chrétien, fondateur du Stahlhelm paramilitaire et compagnon de Moeller van den Bruck dans son combat métapolitique de 1918 à 1925. L’Allemagne devait susciter en son sein l’émergence d’un réseau de cercles intellectuels et politiques, d’associations diverses, de sociétés de pensée et de groupes paramilitaires pour redonner au Reich vaincu un statut de pleine souveraineté sur la scène européenne et internationale.

A la fin du siècle, l’Europe, par le truchement de ces « sciences allemandes », dispose d’une masse de connaissances en tous domaines qui dépassent les petits mondes étriqués des politiques politiciennes, des rabâchages de la caste des juristes, des calculs mesquins du monde économique. Rien n’a changé sur ce plan. Quant à la révolution conservatrice proprement dite, qui veut débarrasser les sociétés européennes de toutes ces scories accumulées par avocats et financiers, politicards et spéculateurs, prêtres sans mystique et bourgeois égoïstes, elle démarre essentiellement par l’initiative que prend en 1896 l’éditeur Eugen Diederichs. Il cultivait l’ambition de proposer à la lecture et à la réflexion une formidable batterie d’idées innovantes capables, à terme, de modeler une société nouvelle, enclenchant de la sorte une révolution véritable qui ne suggère aucune table rase mais au contraire entend ré-enchanter les racines, étouffées sous les scories des conformismes. La même année, le jeune romantique Karl Fischer fonde le mouvement des Wandervögel, dont l’objectif est d’arracher la jeunesse à tous les conformismes et aussi de la sortir des sinistres quartiers surpeuplés des villes devenues tentaculaires suite à la révolution industrielle. Eugen Diederichs veut un socialisme non matérialiste, une religion nouvelle puisant dans la mémoire du peuple et renouant avec les mystiques médiévales (Maître Eckhart, Ruusbroec, Nicolas de Cues, etc.), une libéralisation sexuelle, un néo-romantisme inspiré par des sources allemandes, russes, flamandes ou scandinaves.

A la fin du siècle, l’Europe, par le truchement de ces « sciences allemandes », dispose d’une masse de connaissances en tous domaines qui dépassent les petits mondes étriqués des politiques politiciennes, des rabâchages de la caste des juristes, des calculs mesquins du monde économique. Rien n’a changé sur ce plan. Quant à la révolution conservatrice proprement dite, qui veut débarrasser les sociétés européennes de toutes ces scories accumulées par avocats et financiers, politicards et spéculateurs, prêtres sans mystique et bourgeois égoïstes, elle démarre essentiellement par l’initiative que prend en 1896 l’éditeur Eugen Diederichs. Il cultivait l’ambition de proposer à la lecture et à la réflexion une formidable batterie d’idées innovantes capables, à terme, de modeler une société nouvelle, enclenchant de la sorte une révolution véritable qui ne suggère aucune table rase mais au contraire entend ré-enchanter les racines, étouffées sous les scories des conformismes. La même année, le jeune romantique Karl Fischer fonde le mouvement des Wandervögel, dont l’objectif est d’arracher la jeunesse à tous les conformismes et aussi de la sortir des sinistres quartiers surpeuplés des villes devenues tentaculaires suite à la révolution industrielle. Eugen Diederichs veut un socialisme non matérialiste, une religion nouvelle puisant dans la mémoire du peuple et renouant avec les mystiques médiévales (Maître Eckhart, Ruusbroec, Nicolas de Cues, etc.), une libéralisation sexuelle, un néo-romantisme inspiré par des sources allemandes, russes, flamandes ou scandinaves.

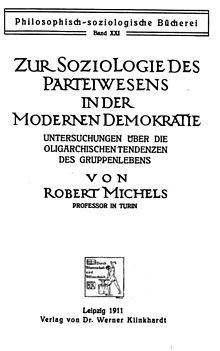

Il faut se rappeler que le rejet le mieux charpenté de la démocratie libérale et surtout de ses dérives partitocratiques ne provient pas d’un mouvement ou cénacle émanant d’une droite posée comme « conservatrice-révolutionnaire » mais d’une haute figure de la social-démocratie allemande et européenne, Roberto Michels, actif en Belgique, en Allemagne et en Italie avant 1914. Ici aussi, je ne fais pas d’anachronisme : à l’université en 1974, on nous conseillait la lecture de sa critique des oligarchies politiciennes (sociaux-démocrates compris) ; après une éclipse navrante de quelques décennies, je constate avec bonheur qu’une grande maison française, Gallimard-Folio, vient de rééditer sa Sociologie du parti dans la démocratie moderne (Zur Soziologie des Parteiwesens), qui démontre avec une clarté inégalée les dérives dangereuses d’une démocratie partitocratique : coupure avec la base, oligarchisation, règne des « bonzes », compromis contraires aux promesses électorales et aux programmes, bref, les maux que tous sont bien contraints de constater aujourd’hui en Europe et ailleurs, en plus amplifiés ! Michels suggère des correctifs : référendum (démocratie directe), renonciation (aux modes de vie matérialistes et bourgeois, ascétisme de l’élite politique se voulant alternative), etc. Dans cet ouvrage fondamental des sciences politiques, Michels vise à dépasser tout ce qui fait le ronron d’un parti (et, partant, d’une vie politique nationale orchestrée autour du jeu répétitif des élections récurrentes d’un certain nombre de partis établis) et suggère des pistes pour échapper à ces enlisements ; elles annoncent les aspirations ultérieures des conservateurs-révolutionnaires (ou assimilés) d’après 1918 et surtout d’après Locarno, sans oublier les futurs non-conformistes français des années 30 et ceux qui, aujourd’hui, cherchent à sortir des impasses où nous ont fourvoyés les établis. Ces pistes insistent sur la nécessité d’avoir des élites politiques ascétiques, sur une virulence correctrice que Michels croyait déceler dans le syndicalisme révolutionnaire (et ses versions italiennes comme celles activées par Filippo Corridoni avant 1914 – Corridoni tombera au front en 1915), dans les idées activistes de Georges Sorel et dans certaines formes d’anarchisme hostiles aux hiérarchies figées. L’idée-clef est de traquer partout, dans les formes de représentation politique, les éléments négatifs qui figent, qui induisent des répétitions lesquelles annulent l’effervescence révolutionnaire ou la dynamique douce/naturelle du peuple, oblitèrent la spontanéité des masses (on y reviendra en mai 68 !). En ce sens, les idées de Michels, Corridoni et Sorel entendent conserver les potentialités vivantes du peuple qui, le cas échéant et quand nécessité fait loi, sont capables de faire éclore un mouvement révolutionnaire correcteur et éradicateur des fixismes répétitifs.

Il faut se rappeler que le rejet le mieux charpenté de la démocratie libérale et surtout de ses dérives partitocratiques ne provient pas d’un mouvement ou cénacle émanant d’une droite posée comme « conservatrice-révolutionnaire » mais d’une haute figure de la social-démocratie allemande et européenne, Roberto Michels, actif en Belgique, en Allemagne et en Italie avant 1914. Ici aussi, je ne fais pas d’anachronisme : à l’université en 1974, on nous conseillait la lecture de sa critique des oligarchies politiciennes (sociaux-démocrates compris) ; après une éclipse navrante de quelques décennies, je constate avec bonheur qu’une grande maison française, Gallimard-Folio, vient de rééditer sa Sociologie du parti dans la démocratie moderne (Zur Soziologie des Parteiwesens), qui démontre avec une clarté inégalée les dérives dangereuses d’une démocratie partitocratique : coupure avec la base, oligarchisation, règne des « bonzes », compromis contraires aux promesses électorales et aux programmes, bref, les maux que tous sont bien contraints de constater aujourd’hui en Europe et ailleurs, en plus amplifiés ! Michels suggère des correctifs : référendum (démocratie directe), renonciation (aux modes de vie matérialistes et bourgeois, ascétisme de l’élite politique se voulant alternative), etc. Dans cet ouvrage fondamental des sciences politiques, Michels vise à dépasser tout ce qui fait le ronron d’un parti (et, partant, d’une vie politique nationale orchestrée autour du jeu répétitif des élections récurrentes d’un certain nombre de partis établis) et suggère des pistes pour échapper à ces enlisements ; elles annoncent les aspirations ultérieures des conservateurs-révolutionnaires (ou assimilés) d’après 1918 et surtout d’après Locarno, sans oublier les futurs non-conformistes français des années 30 et ceux qui, aujourd’hui, cherchent à sortir des impasses où nous ont fourvoyés les établis. Ces pistes insistent sur la nécessité d’avoir des élites politiques ascétiques, sur une virulence correctrice que Michels croyait déceler dans le syndicalisme révolutionnaire (et ses versions italiennes comme celles activées par Filippo Corridoni avant 1914 – Corridoni tombera au front en 1915), dans les idées activistes de Georges Sorel et dans certaines formes d’anarchisme hostiles aux hiérarchies figées. L’idée-clef est de traquer partout, dans les formes de représentation politique, les éléments négatifs qui figent, qui induisent des répétitions lesquelles annulent l’effervescence révolutionnaire ou la dynamique douce/naturelle du peuple, oblitèrent la spontanéité des masses (on y reviendra en mai 68 !). En ce sens, les idées de Michels, Corridoni et Sorel entendent conserver les potentialités vivantes du peuple qui, le cas échéant et quand nécessité fait loi, sont capables de faire éclore un mouvement révolutionnaire correcteur et éradicateur des fixismes répétitifs.

Reste aussi un autre problème que l’époque et ses avant-gardes politiques et littéraires ont tenté de résoudre dans la pétulance et l’intempérance : celui de la vitesse. Chez les futuristes, c’est clair, surtout dans certaines de leurs plus belles œuvres picturales, la vitesse est l’ivresse du monde, le mode exaltant qui, maîtrisé ou chevauché, permet d’échapper justement aux fixismes, au « passatismo ». A gauche aussi, la révolution a pour but de réaliser vite les aspirations populaires. Le prolétariat révolutionnaire des bolcheviques, une fois au pouvoir, maîtrise les machines et les rapidités qu’elles procurent. Le conseillisme bavarois, quant à lui, ne souhaitait pas effacer les spontanéités vitales de la population. Le fascisme de Mussolini, venu du socialisme et du syndicalisme sorélien et corrodinien, ne l’oublions jamais, entend réaliser en six heures ce que la démocratie parlementaire et palabrante (et donc lente, hyper-lente) fait en six ans. Les réactionnaires, que les futuristes ou les bolcheviques jugeront « passéistes », rappelaient que la prise de décision du monarque ou du petit nombre dans les anciens régimes était plus rapide que celle des parlements (d’où la présence récurrente de figures de la contre-révolution française dans les démarches intellectuelles d’Ernst Jünger, fussent-elles les plus maximalistes avant 1925). Un système politique cohérent, pour les avant-gardes des années 20, doit donc pouvoir décider rapidement, à la vitesse des nouvelles machines, des bolides Bugatti ou Mercedes, des avions des pionniers de l’air, des vedettes rapides des nouvelles forces navales (d’Annunzio). Une force politique nouvelle, démocratique ou non (Fiume est une démocratie avant-gardiste !), doit être décisionnaire et rapide, donc jeune. Si elle est parlementaire et palabrante, elle est lente donc vieille et cette sénilité pétrifiée mérite d’être jetée bas. La double idée de décision et de rapidité d’exécution est évidemment présente dans le nationalisme soldatique et explique pourquoi le coup de force est considéré comme plus efficace et plus propre que les palabres parlementaires. Elle apparait ensuite dans la théorie politique plus élaborée et plus juridique de Carl Schmitt, qui rejette le normativisme (comme étant un système de règles figées finalement incapacitantes quand le danger guette la Cité, où la « lex », par sa lourde présence, sape l’action du « rex ») et le positivisme juridique, trop technique et inattentif aux valeurs pérennes. Schmitt, décisionniste, prône évidemment le décisionnisme, dont il est le représentant le plus emblématique, et insiste sur la nécessité permanente d’agir au sein d’ordres concrets, réellement existants, hérités, légués par l’histoire et les traditions politiques de la Cité (ce qui implique le rejet de toute volonté de créer un « Etat mondial »).

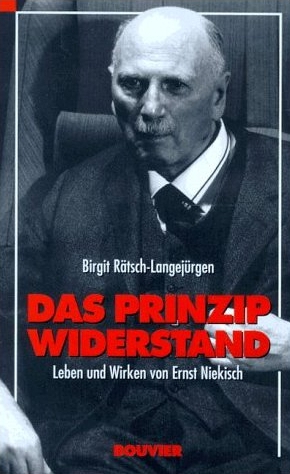

Reste aussi un autre problème que l’époque et ses avant-gardes politiques et littéraires ont tenté de résoudre dans la pétulance et l’intempérance : celui de la vitesse. Chez les futuristes, c’est clair, surtout dans certaines de leurs plus belles œuvres picturales, la vitesse est l’ivresse du monde, le mode exaltant qui, maîtrisé ou chevauché, permet d’échapper justement aux fixismes, au « passatismo ». A gauche aussi, la révolution a pour but de réaliser vite les aspirations populaires. Le prolétariat révolutionnaire des bolcheviques, une fois au pouvoir, maîtrise les machines et les rapidités qu’elles procurent. Le conseillisme bavarois, quant à lui, ne souhaitait pas effacer les spontanéités vitales de la population. Le fascisme de Mussolini, venu du socialisme et du syndicalisme sorélien et corrodinien, ne l’oublions jamais, entend réaliser en six heures ce que la démocratie parlementaire et palabrante (et donc lente, hyper-lente) fait en six ans. Les réactionnaires, que les futuristes ou les bolcheviques jugeront « passéistes », rappelaient que la prise de décision du monarque ou du petit nombre dans les anciens régimes était plus rapide que celle des parlements (d’où la présence récurrente de figures de la contre-révolution française dans les démarches intellectuelles d’Ernst Jünger, fussent-elles les plus maximalistes avant 1925). Un système politique cohérent, pour les avant-gardes des années 20, doit donc pouvoir décider rapidement, à la vitesse des nouvelles machines, des bolides Bugatti ou Mercedes, des avions des pionniers de l’air, des vedettes rapides des nouvelles forces navales (d’Annunzio). Une force politique nouvelle, démocratique ou non (Fiume est une démocratie avant-gardiste !), doit être décisionnaire et rapide, donc jeune. Si elle est parlementaire et palabrante, elle est lente donc vieille et cette sénilité pétrifiée mérite d’être jetée bas. La double idée de décision et de rapidité d’exécution est évidemment présente dans le nationalisme soldatique et explique pourquoi le coup de force est considéré comme plus efficace et plus propre que les palabres parlementaires. Elle apparait ensuite dans la théorie politique plus élaborée et plus juridique de Carl Schmitt, qui rejette le normativisme (comme étant un système de règles figées finalement incapacitantes quand le danger guette la Cité, où la « lex », par sa lourde présence, sape l’action du « rex ») et le positivisme juridique, trop technique et inattentif aux valeurs pérennes. Schmitt, décisionniste, prône évidemment le décisionnisme, dont il est le représentant le plus emblématique, et insiste sur la nécessité permanente d’agir au sein d’ordres concrets, réellement existants, hérités, légués par l’histoire et les traditions politiques de la Cité (ce qui implique le rejet de toute volonté de créer un « Etat mondial »). Ernst Niekisch est un révolutionnaire de gauche pur jus. Il a participé à un gouvernement des Conseils en Bavière, lesquels seront balayés par les Corps Francs de von Epp. Dans ce gouvernement, figurait également Gustav Landauer, penseur anarchiste éminemment fécond, puisant à des sources intéressantes du 19ème siècle et développant une anthropologie compénétrée de mystique. Ce premier gouvernement des Conseils, non explicitement communiste, sera renversé par les bolcheviques du KPD, provoquant chez Landauer une immense déception. Pour lui, la politique révolutionnaire bavaroise sombrait, par ce coup de force, dans les rigidités léninistes et perdait son originalité unique. Niekisch était sans nul doute plus marqué par le marxisme de la social-démocratie d’avant 1914 mais sous l’influence d’un camarade aussi subtil que Landauer, il a dû ajouter à sa formation initiale des éléments moins conventionnels, notamment plus communautaires-anarchisants (héritage de Bakounine et Kropotkine). Cet anarchisme, hostile à toute rigidité et répétition, Niekisch le couple à des idéaux paysans/ruralistes présents dans les « sources du communisme russe » (explorées par Berdiaev) ou chez Tolstoï (édité par Diederichs) et, bien entendu, chez les folcistes (Völkischen) allemands, lesquels étaient plutôt classés « à droite ». Cette mythologie nouvelle devient alors chez Niekisch un mixte de prolétarisme socialiste et de ruralisme germano-russe, saupoudré de quelques oripeaux libertaires légués par Landauer, le tout pour favoriser une révolution allemande philo-soviétique, destinée à libérer les ouvriers et les paysans d’Allemagne d’une bourgeoisie pro-occidentale qui acceptait les réparations imposées par l’Ouest lors du Traité de Versailles, au détriment de son propre peuple, et les crédits américains des Plans Young et Dawes, limitant la souveraineté nationale.

Ernst Niekisch est un révolutionnaire de gauche pur jus. Il a participé à un gouvernement des Conseils en Bavière, lesquels seront balayés par les Corps Francs de von Epp. Dans ce gouvernement, figurait également Gustav Landauer, penseur anarchiste éminemment fécond, puisant à des sources intéressantes du 19ème siècle et développant une anthropologie compénétrée de mystique. Ce premier gouvernement des Conseils, non explicitement communiste, sera renversé par les bolcheviques du KPD, provoquant chez Landauer une immense déception. Pour lui, la politique révolutionnaire bavaroise sombrait, par ce coup de force, dans les rigidités léninistes et perdait son originalité unique. Niekisch était sans nul doute plus marqué par le marxisme de la social-démocratie d’avant 1914 mais sous l’influence d’un camarade aussi subtil que Landauer, il a dû ajouter à sa formation initiale des éléments moins conventionnels, notamment plus communautaires-anarchisants (héritage de Bakounine et Kropotkine). Cet anarchisme, hostile à toute rigidité et répétition, Niekisch le couple à des idéaux paysans/ruralistes présents dans les « sources du communisme russe » (explorées par Berdiaev) ou chez Tolstoï (édité par Diederichs) et, bien entendu, chez les folcistes (Völkischen) allemands, lesquels étaient plutôt classés « à droite ». Cette mythologie nouvelle devient alors chez Niekisch un mixte de prolétarisme socialiste et de ruralisme germano-russe, saupoudré de quelques oripeaux libertaires légués par Landauer, le tout pour favoriser une révolution allemande philo-soviétique, destinée à libérer les ouvriers et les paysans d’Allemagne d’une bourgeoisie pro-occidentale qui acceptait les réparations imposées par l’Ouest lors du Traité de Versailles, au détriment de son propre peuple, et les crédits américains des Plans Young et Dawes, limitant la souveraineté nationale. Pour ma génération qui a exactement vingt ans en 1976, c’est effectivement le livre Baltikum de Dominique Venner qui fait découvrir la geste des Corps Francs allemands d’après 1918. Par la suite, nous avons découvert assez rapidement Ernst von Salomon, dont Les Réprouvés étaient édités en « livre de poche » et que nous trimbalions dans nos cartables de collégiens.

Pour ma génération qui a exactement vingt ans en 1976, c’est effectivement le livre Baltikum de Dominique Venner qui fait découvrir la geste des Corps Francs allemands d’après 1918. Par la suite, nous avons découvert assez rapidement Ernst von Salomon, dont Les Réprouvés étaient édités en « livre de poche » et que nous trimbalions dans nos cartables de collégiens.  En France, la veine nietzschéenne et les progrès des études germaniques, sous l’impulsion de Charles Andler, introduisaient des ferments similaires à ceux qui agitaient la scène culturelle wilhelminienne en Allemagne avant 1914. Le filtre de la Grande Guerre fait que partout en Europe les postures politiques acquièrent une dimension plus « quiritaire ». En Angleterre, certains avant-gardistes optent pour des sympathies profascistes. David Herbert Lawrence rejette le puritanisme victorien, comme les Allemands avant 1914 avaient rejeté d’autres formes de rigorisme, en injectant dans la littérature anglaise des ferments d’organicisme à connotations sexuelles (« L’amant de Lady Chatterley »), en insistant sur la puissance tellurique inépuisable des religions primitives (du Mexique notamment), en démontrant dans Apocalypse que toute civilisation doit reposer sur un cycle liturgique naturel intangible ; il induit ainsi des ferments révolutionnaires conservateurs (il faut balayer les puritanismes, les rationalismes étriqués, etc. et maintenir les cycles liturgiques naturels, au moins comme le fait le catholicisme) dans la pensée anglo-saxonne, qui, liés aux filons celtisants et catholiques du nationalisme culturel irlandais, partiellement dérivés de Herder, s’insinuent, aujourd’hui encore, dans une quantité de démarches culturelles fécondes, observables dans les sociétés anglophones. Même si ces démarches ont parfois l’agaçant aspect du « New Age » ou du post-hippysme.

En France, la veine nietzschéenne et les progrès des études germaniques, sous l’impulsion de Charles Andler, introduisaient des ferments similaires à ceux qui agitaient la scène culturelle wilhelminienne en Allemagne avant 1914. Le filtre de la Grande Guerre fait que partout en Europe les postures politiques acquièrent une dimension plus « quiritaire ». En Angleterre, certains avant-gardistes optent pour des sympathies profascistes. David Herbert Lawrence rejette le puritanisme victorien, comme les Allemands avant 1914 avaient rejeté d’autres formes de rigorisme, en injectant dans la littérature anglaise des ferments d’organicisme à connotations sexuelles (« L’amant de Lady Chatterley »), en insistant sur la puissance tellurique inépuisable des religions primitives (du Mexique notamment), en démontrant dans Apocalypse que toute civilisation doit reposer sur un cycle liturgique naturel intangible ; il induit ainsi des ferments révolutionnaires conservateurs (il faut balayer les puritanismes, les rationalismes étriqués, etc. et maintenir les cycles liturgiques naturels, au moins comme le fait le catholicisme) dans la pensée anglo-saxonne, qui, liés aux filons celtisants et catholiques du nationalisme culturel irlandais, partiellement dérivés de Herder, s’insinuent, aujourd’hui encore, dans une quantité de démarches culturelles fécondes, observables dans les sociétés anglophones. Même si ces démarches ont parfois l’agaçant aspect du « New Age » ou du post-hippysme.

In una relazione sulla sua missione in India, inviata il 31 marzo 1931 al ministro degli Esteri Dino Grandi, Tucci propose la fondazione di un istituto culturale finalizzato ad agevolare gli studi dei giovani Indiani in Italia e presso le istituzioni italiane, a promuovere la conoscenza dell'Italia in India, a mettere in contatto studiosi indiani e italiani dagli interessi affini. Mussolini, che giа accarezzava l'idea di dar vita ad un istituto per le relazioni italo-indiane, ricevette in udienza il professore maceratese e rimase d'accordo con lui che avrebbe esaminato il suo progetto quando egli fosse ritornato dal viaggio di esplorazione che si accingeva ad intraprendere nel Tibet. Rientrato in Italia nel novembre del 1931, Tucci riuscм a coinvolgere nel suo progetto il presidente dell'Accademia d'Italia, Giovanni Gentile, che nel luglio dell'anno successivo ottenne dal Duce l'approvazione definitiva.

In una relazione sulla sua missione in India, inviata il 31 marzo 1931 al ministro degli Esteri Dino Grandi, Tucci propose la fondazione di un istituto culturale finalizzato ad agevolare gli studi dei giovani Indiani in Italia e presso le istituzioni italiane, a promuovere la conoscenza dell'Italia in India, a mettere in contatto studiosi indiani e italiani dagli interessi affini. Mussolini, che giа accarezzava l'idea di dar vita ad un istituto per le relazioni italo-indiane, ricevette in udienza il professore maceratese e rimase d'accordo con lui che avrebbe esaminato il suo progetto quando egli fosse ritornato dal viaggio di esplorazione che si accingeva ad intraprendere nel Tibet. Rientrato in Italia nel novembre del 1931, Tucci riuscм a coinvolgere nel suo progetto il presidente dell'Accademia d'Italia, Giovanni Gentile, che nel luglio dell'anno successivo ottenne dal Duce l'approvazione definitiva.

Two: Lawrence Dennis was part African-American, a fact that was marginally believable at first glance, given his “swarthy” or “bronzed” complexion and short, wiry hair. Dennis could “pass for white” if he wanted to, and so he did for several decades. But this was mainly for reasons of convenience. During his years at Exeter, Harvard, the diplomatic corps, and Wall Street, talking about a mulatto heritage was just an unnecessary complication, and so he didn’t. At the end of the day there is no reason to believe he was ashamed of his mixed-race heritage; it is said that when he died in his eighties he was

Two: Lawrence Dennis was part African-American, a fact that was marginally believable at first glance, given his “swarthy” or “bronzed” complexion and short, wiry hair. Dennis could “pass for white” if he wanted to, and so he did for several decades. But this was mainly for reasons of convenience. During his years at Exeter, Harvard, the diplomatic corps, and Wall Street, talking about a mulatto heritage was just an unnecessary complication, and so he didn’t. At the end of the day there is no reason to believe he was ashamed of his mixed-race heritage; it is said that when he died in his eighties he was  A most bizarre start in life for a diplomat, or Wall Street investment banker, or fascist economic theorist—all of which Dennis would be in the 1920s and ’30s.

A most bizarre start in life for a diplomat, or Wall Street investment banker, or fascist economic theorist—all of which Dennis would be in the 1920s and ’30s. 1. Gerald Horne, The Color of Fascism: Lawrence Dennis, Racial Passing, and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism in the United States (New York: New York University Press, 2007).

1. Gerald Horne, The Color of Fascism: Lawrence Dennis, Racial Passing, and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism in the United States (New York: New York University Press, 2007).

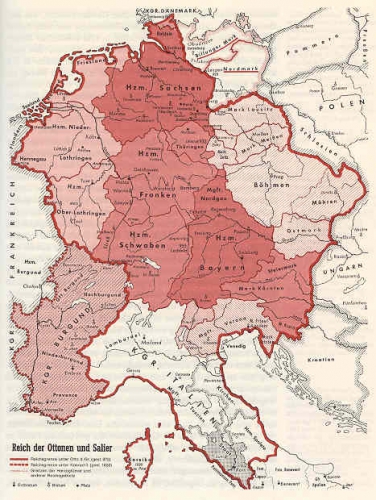

Nous ne sommes pas familiers de la forme impériale développée par le Saint Empire romain germanique réunissant les territoires italiens, bourguignon et germanique à l'origine, émancipant par la suite les deux premiers. Elle s'étend pourtant sur près de neuf siècles, et constitue le grand modèle institutionnel duquel se démarqua l'État souverain. Si Pufendorf a pu le qualifier de « monstre politique », « irregulare aliquod corpus et montro simile », il n'en reste pas moins que sa longévité nous incline à considérer sérieusement la forme institutionnelle de ce pouvoir. Nous en rappellerons brièvement les éléments essentiels, d'un point de vue normatif plus qu'historique. Le titre de Saint Empire romain germanique, das Heilige Römische Reich deutscher Nation, ne commence à être utilisé qu'à la fin du XVe siècle. Mais il n'est encore ni une appellation officielle, ni une seule utilisée pour décrire la situation politique de l'Empire germanique. L'ambition de cette désignation consiste à trouver un critère discriminant d'appartenance des différents peuples germaniques à une structure politique commune.