mercredi, 30 octobre 2013

Munich ou Athènes-sur-l’Isar: ville de culture et matrice d’idées conservatrices-révolutionnaires

Robert STEUCKERS:

Munich ou Athènes-sur-l’Isar: ville de culture et matrice d’idées conservatrices-révolutionnaires

Conférence prononcée à Vlotho im Wesergebirge, université d’été de “Synergies Européennes”, 2002

Cette conférence est la recension des premiers chapitres de:

David Clay Large, Hitlers München – Aufstieg und Fall der Hauptstadt der Bewegung, C. H. Beck, Munich, 1998.

Le passé de Munich, capitale bavaroise, est marqué par la volonté culturelle de ses rois. Il y a d’abord eu Louis I, qui règne de 1825 à 1848. Ce monarque, quand il était prince héritier, a fait le voyage en Italie, en 1817-1818: il a été, comme beaucoup d’Allemands, fasciné par l’urbanisme traditionnel des villes de la péninsule et veut faire de Munich, sa “Residenzstadt”, un centre culturel allemand incontournable, au service d’une véritable renaissance culturelle qui a, cette fois, pour point de départ, l’espace germanophone du centre de l’Europe. Pour embellir la “ville de résidence”, il fait appel à des architectes comme Leo von Klenze et Friedrich von Gärtner, tous deux appartenant à l’école dite “classique”, renouant avec les canons grecs et romains de l’antiquité, ceux de Vitruve. En épousant la cantatrice espagnole Lola Montez, il se heurte à la bourgeoisie philistine de la ville, hostile aux dépenses de prestige voulues par le roi et qui prend le prétexte de ce mariage avec une roturière étrangère, pour manifester sa désapprobation à l’endroit de la politique royale et du mécénat pratiqué par le monarque. Ce mariage donnera lieu à quantité de ragots irrévérencieux, censés saborder l’autorité de ce monarque tourné vers les arts.

Le passé de Munich, capitale bavaroise, est marqué par la volonté culturelle de ses rois. Il y a d’abord eu Louis I, qui règne de 1825 à 1848. Ce monarque, quand il était prince héritier, a fait le voyage en Italie, en 1817-1818: il a été, comme beaucoup d’Allemands, fasciné par l’urbanisme traditionnel des villes de la péninsule et veut faire de Munich, sa “Residenzstadt”, un centre culturel allemand incontournable, au service d’une véritable renaissance culturelle qui a, cette fois, pour point de départ, l’espace germanophone du centre de l’Europe. Pour embellir la “ville de résidence”, il fait appel à des architectes comme Leo von Klenze et Friedrich von Gärtner, tous deux appartenant à l’école dite “classique”, renouant avec les canons grecs et romains de l’antiquité, ceux de Vitruve. En épousant la cantatrice espagnole Lola Montez, il se heurte à la bourgeoisie philistine de la ville, hostile aux dépenses de prestige voulues par le roi et qui prend le prétexte de ce mariage avec une roturière étrangère, pour manifester sa désapprobation à l’endroit de la politique royale et du mécénat pratiqué par le monarque. Ce mariage donnera lieu à quantité de ragots irrévérencieux, censés saborder l’autorité de ce monarque tourné vers les arts.

De Maximilien II au Prince-Régent Luitpold

Son successeur sur le trône bavarois, Maximilien II, règnera de 1848 à 1864. En dépit des cabales menées contre son père, il poursuivra l’oeuvre de ce dernier, ajoutant au classicisme une touche de futurisme, en faisant construire un palais des glaces (de fer et de verre) comme celui de Londres, prélude à une architecture différente qui ne table plus uniquement sur la pierre comme matériau de construction. Maximilien II attire des savants d’Allemagne du Nord à Munich, qui ne sont évidemment pas des Bavarois de souche: on parlera alors des “Nordlichter”, des “Lumières du Nord”. Louis II, qui règne de 1864 à 1886, prônera une nouvelle architecture romantique, inspirée par les opéras de Wagner, par le moyen âge, riche en ornementations. On connaît ses châteaux, dont celui, merveilleux, de Neuschwanstein. Cette politique se heurte également à une bourgeoisie philistine, insensible à toute forme de beauté. Après Louis II, après sa mort étrange, le Prince-Régent Luitpold, aimé du peuple, préconise une industrialisation et une urbanisation de la Bavière. Munich connaît alors une évolution semblable à celle de Bruxelles: en 1800, la capitale bavaroise comptait 34.000 habitants; en 1880, elle en avait 230.000; en 1910, 596.000. Pour la capitale belge, les chiffres sont à peu près les mêmes. Mais cette industrialisation/urbanisation provoque des déséquilibres que la Bavière ne connaissait pas auparavant. D’abord il y a l’ensauvagement des moeurs: si la liaison entre Louis I et Lola Montez avait fait scandale, alors qu’elle était toute romantique et innocente, les trottoirs de la ville sont désormais livrés à une prostitution hétérosexuelle et homosexuelle qui n’épargne pas les mineurs d’âge. Il y a ensuite les mutations politiques qu’entraîne le double phénomène moderne de l’industrialisation et de l’urbanisation: les forces politiques conservatrices et catholiques, qui avaient tenu le haut du pavé avant l’avènement du Prince-Régent Luitpold, sont remises en question par la bourgeoisie libérale (déjà hostile aux rois mécènes) et par le prolétariat.

Son successeur sur le trône bavarois, Maximilien II, règnera de 1848 à 1864. En dépit des cabales menées contre son père, il poursuivra l’oeuvre de ce dernier, ajoutant au classicisme une touche de futurisme, en faisant construire un palais des glaces (de fer et de verre) comme celui de Londres, prélude à une architecture différente qui ne table plus uniquement sur la pierre comme matériau de construction. Maximilien II attire des savants d’Allemagne du Nord à Munich, qui ne sont évidemment pas des Bavarois de souche: on parlera alors des “Nordlichter”, des “Lumières du Nord”. Louis II, qui règne de 1864 à 1886, prônera une nouvelle architecture romantique, inspirée par les opéras de Wagner, par le moyen âge, riche en ornementations. On connaît ses châteaux, dont celui, merveilleux, de Neuschwanstein. Cette politique se heurte également à une bourgeoisie philistine, insensible à toute forme de beauté. Après Louis II, après sa mort étrange, le Prince-Régent Luitpold, aimé du peuple, préconise une industrialisation et une urbanisation de la Bavière. Munich connaît alors une évolution semblable à celle de Bruxelles: en 1800, la capitale bavaroise comptait 34.000 habitants; en 1880, elle en avait 230.000; en 1910, 596.000. Pour la capitale belge, les chiffres sont à peu près les mêmes. Mais cette industrialisation/urbanisation provoque des déséquilibres que la Bavière ne connaissait pas auparavant. D’abord il y a l’ensauvagement des moeurs: si la liaison entre Louis I et Lola Montez avait fait scandale, alors qu’elle était toute romantique et innocente, les trottoirs de la ville sont désormais livrés à une prostitution hétérosexuelle et homosexuelle qui n’épargne pas les mineurs d’âge. Il y a ensuite les mutations politiques qu’entraîne le double phénomène moderne de l’industrialisation et de l’urbanisation: les forces politiques conservatrices et catholiques, qui avaient tenu le haut du pavé avant l’avènement du Prince-Régent Luitpold, sont remises en question par la bourgeoisie libérale (déjà hostile aux rois mécènes) et par le prolétariat.

Bipolarisme politique

Un bipolarisme politique voit le jour dans la seconde moitié du 19ème siècle avec, d’une part, le “Patriotenpartei”, fondé en 1868, rassemblant les forces conservatrices catholiques, hostiles à la Prusse protestante et au “Kulturkampf” anti-clérical lancé par le Chancelier Bismarck. Pour les “Patrioten”, l’identité bavaroise est catholique et conservatrice. Les autres idées, importées, sont nuisibles. Face à ce rassemblement conservateur et religieux se dresse, d’autre part, le “parti social-démocrate”, fondé en 1869, qui parvient à rassembler 14% des suffrages à Munich lors des élections de 1878. Le chef de file des sociaux-démocrates, Georg von Vollmar, n’est pas un extrémiste: il s’oppose à tout dogmatisme idéologique et se profile comme un réformiste pragmatique. Cette politique paie: en 1890, les socialistes modérés et réformistes obtiennent la majorité à Munich. La ville est donc devenue rouge dans un environnement rural et semi-rural bavarois majoritairement conservateur et catholique. Cette mutation du paysage politique bavarois s’effectue sur fond d’un antisémitisme ambiant, qui n’épargne que quelques vieilles familles israélites, dont celle du mécène Alfred Pringsheim. Les Juifs, dans l’optique de cet antisémitisme bavarois, sont considérés comme les vecteurs d’une urbanisation sauvage qui a provoqué l’effondrement des bonnes moeurs; on les accuse, notamment dans les colonnes d’une feuille populaire intitulée “Grobian”, de spéculer dans le secteur immobilier et d’être les “produits collatéraux” du progrès, notamment du “progrès automobile”. Cet antisémitisme provoque une rupture au sein des forces conservatrices, suite à la fondation en 1891 d’un nouveau mouvement politique, le “Deutsch-Sozialer Verein” ou DSV, sous la houlette de Viktor Hugo Welcker qui, armé de quelques arguments tirés de cet antisémitisme, entame une campagne sociale et populaire contre les grands magasins, les agences immobilières et les chaînes de petits commerces en franchise, dont les tenanciers ne sont pas les véritables propriétaires de leur boutique.

Les pangermanistes

A l’émergence du DSV s’ajoute celle des cercles pangermanistes (“Alldeutscher Verband”) qui véhiculent également une forme d’antisémitisme mais sont constitués en majorité de protestants d’origine nord-allemande installés en Bavière et hostiles au catholicisme sociologique bavarois qu’ils jugent “rétrograde”. Les pangermanistes vont dès lors s’opposer à ce particularisme catholique bavarois et, par voie de conséquence, au “Patriotenpartei”. Pour les pangermanistes, la Bavière doit se détacher de l’Autriche et de la Bohème majoritairement tchèque, parce que celles-ci ne sont pas “purement allemandes”. Dans une seconde phase, les pangermanistes vont articuler dans la société bavaroise un anti-christianisme sous l’impulsion de l’éditeur Julius Friedrich Lehmann. Pour ce dernier et pour les théoriciens qui lui sont proches, une lutte systématique et efficace contre le christianisme permettrait aux Allemands de mieux résister à l’emprise du judaïsme ou, quand cet anti-christianisme n’est qu’anti-confessionnel et ne touche pas à la personne du Christ, de faire éclore une “chrétienté germanique” mâtinée d’éléments de paganisme. Cette attitude du mouvement pangermaniste en Bavière ou en Autriche s’explique partiellement par le fait que la hiérarchie catholique avait tendance à soutenir les populations rurales slaves de Bohème, de Slovénie ou de Croatie, plus pieuses et souvent plus prolifiques sur le plan démographique. Les protestants “germanisés” dans le cadre du pangermanisme affirmaient que l’Allemagne et la Bavière avaient besoin d’un “nouveau Luther”.

Le contre-monde de Schwabing

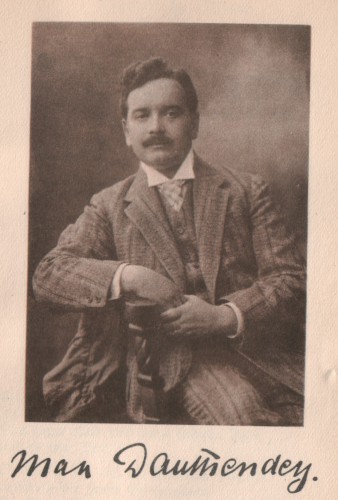

Telle était donc la scène politique qui animait la Bavière dans les deux décennies qui ont précédé la première guerre mondiale. Deuxième question de notre exposé aujourd’hui: comment le choc des visions du monde (car c’est bien de cela qu’il s’agit) s’est-il manifesté à Munich au sein de la bohème littéraire, productrice d’oeuvres qui nous interpellent encore et toujours? Cette bohème littéraire a, de fait, généré un contre-monde libre-penseur, débarrassé du fardeau des “tu dois”, propre au chameau de la fable de Nietzsche, un contre-monde qui devait s’opposer aux raideurs du wilhelminisme prussien. On peut dire aujourd’hui que la bohème munichoise était une sorte d’extra-territorialité, installée dans les cafés à la mode du faubourg de Schwabing. Les “Schwabinger” vont remplacer les “Nordlichter” en préconisant une sorte de “laisser-aller joyeux et sensuel” (“sinnenfrohe Schlamperei”) contre les “ours lourdauds en leur cerveau” (“bärenhaft dumpf im Gehirn”). Cette volonté de rendre l’humanité allemande plus joyeuse et plus sensuelle va amorcer un combat contre les étroitesses de la religion (tant catholique que protestante), va refuser les rigidités de l’Etat (et du militarisme prussien), va critiquer la domination de plus en plus patente de la technique et de l’argent (en déployant, à ce niveau-là, une nouvelle forme d’antisémitisme antimoderne). Les “Schwabinger”, dans leurs critiques, vont englober éléments de droite et de gauche.

Le 18 décembre 1890 est le jour de la fondation de la “Gesellschaft für modernes Leben” (“Société pour la vie moderne”), une association animée par Michael Georg Conrad (très hostile aux catholiques), Otto Julius Bierbaum, Julius Schaumberger, Hanns von Gumppenberg. Pour Conrad, qu’admirait Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, la tâche principale de la littérature est “d’abattre les vaches sacrées” (tâche encore plus urgente aujourd’hui!). Conrad s’attaquera à la personnalité de l’Empereur Guillaume II, “le monarque qui n’a pas le temps”, lui reprochant sa frénésie à voyager partout dans le monde, à sacrifier au culte de la mobilité fébrile propre à la Belle Epoque. Conrad sera plusieurs fois condamné pour “crime de lèse-majesté” et subira même un internement de deux mois en forteresse. Mais cet irrévérencieux n’est pas ce que nous appelerions aujourd’hui un “gauchiste”. Il s’oppose avec virulence à l’emprise sur Munich de la SPD sociale-démocrate et de son idéologie de la lutte des classes. Conrad veut une réconciliation des masses et de la monarchie, en dépit des insuffisances actuelles et conjoncturelles du wilhelminisme. Pour lui, les socialistes et les ultramontains sont à mettre dans le même sac car ces deux forces politiques ont pour objectif de détruire “l’esprit national”, lequel n’est nullement “bigot”, “bourgeois” au sens de “Biedermeier” mais, au contraire, doit s’affirmer comme insolent (“frech”) et moqueur (“pfiffig”). L’Allemand de demain doit être, selon Conrad, “uilenspiegelien” (la mère de Charles De Coster était munichoise!) et opposer aux établis coincés le cortège de ses frasques et de ses farces. La littérature a dès lors pour but de “libérer la culture allemande de tout fatras poussiéreux” (“Die deutsche Kultur von allem Angestaubten zu befreien”). L’art est l’arme par excellence de ce combat métapolitique.

Insolence et moqueries

Insolence et moqueries dans ce combat métapolitique de libération nationale seront incarnées par Oskar Panizza (1853-1921), psychiatre et médecin militaire, auteur de pièces de théâtre et de poèmes. Panizza s’insurge contre le moralisme étouffant de son époque, héritage du formatage chrétien. Pour lui, la sensualité (souvent hyper-sexualisée) est la force motrice de la littérature et de l’art, par voie de conséquence, le moralisme ambiant est totalement incompatible avec le génie littéraire. Panizza consigne ces visions peu conventionnelles (mais dérivées d’une certaine psychanalyse) et blasphématoires dans une série d’écrits et de conférences visant à détruire l’image édulcorée que les piétistes se faisait de l’histoire de la littérature allemande. Dans une pièce de théâtre, “Das Liebeskonzil”, il se moque du mythe chrétien de la Sainte Famille, ce qui lui vaut une condamnation à un an de prison pour atteinte aux bonnes moeurs et aux sentiments religieux: c’est la peine la plus sévère prononcée dans l’Allemagne wilhelminienne à l’encontre d’un auteur. Une certaine gauche spontanéiste, dans le sillage de mai 68, a tenté de récupérer Oskar Panizza mais n’a jamais pu annexer son antisémitisme affiché, de facture pansexualiste et délirante. Panizza, en effet, voyait le judaïsme, et le catholicisme figé, pharisaïque, qui en découlait, comme une source de l’anti-vitalisme dominant en Europe qui conduit, affirmait-il avec l’autorité du médecin-psychiatre, à l’affadissement des âmes et à la perversité sexuelle. Ses tribulations, jugées scandaleuses, le conduisent à un exil suisse puis français afin d’échapper à une condamnation en Allemagne pour lèse-majesté. En 1904, pour se soustraire au jugement qui allait immanquablement le condamner, il sort nu dans la rue, est arrêté, considéré comme fou et interné dans un asile psychatrique, où il mourra en 1921.

Insolence et moqueries dans ce combat métapolitique de libération nationale seront incarnées par Oskar Panizza (1853-1921), psychiatre et médecin militaire, auteur de pièces de théâtre et de poèmes. Panizza s’insurge contre le moralisme étouffant de son époque, héritage du formatage chrétien. Pour lui, la sensualité (souvent hyper-sexualisée) est la force motrice de la littérature et de l’art, par voie de conséquence, le moralisme ambiant est totalement incompatible avec le génie littéraire. Panizza consigne ces visions peu conventionnelles (mais dérivées d’une certaine psychanalyse) et blasphématoires dans une série d’écrits et de conférences visant à détruire l’image édulcorée que les piétistes se faisait de l’histoire de la littérature allemande. Dans une pièce de théâtre, “Das Liebeskonzil”, il se moque du mythe chrétien de la Sainte Famille, ce qui lui vaut une condamnation à un an de prison pour atteinte aux bonnes moeurs et aux sentiments religieux: c’est la peine la plus sévère prononcée dans l’Allemagne wilhelminienne à l’encontre d’un auteur. Une certaine gauche spontanéiste, dans le sillage de mai 68, a tenté de récupérer Oskar Panizza mais n’a jamais pu annexer son antisémitisme affiché, de facture pansexualiste et délirante. Panizza, en effet, voyait le judaïsme, et le catholicisme figé, pharisaïque, qui en découlait, comme une source de l’anti-vitalisme dominant en Europe qui conduit, affirmait-il avec l’autorité du médecin-psychiatre, à l’affadissement des âmes et à la perversité sexuelle. Ses tribulations, jugées scandaleuses, le conduisent à un exil suisse puis français afin d’échapper à une condamnation en Allemagne pour lèse-majesté. En 1904, pour se soustraire au jugement qui allait immanquablement le condamner, il sort nu dans la rue, est arrêté, considéré comme fou et interné dans un asile psychatrique, où il mourra en 1921.

Le “Simplicissimus”

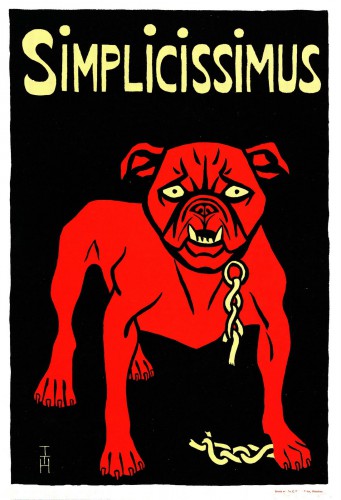

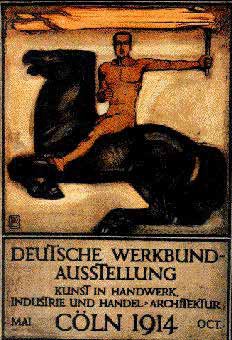

En 1896 se crée à Munich la fameuse revue satirique “Simplicissimus” qui, d’emblée, se donne pour tâche de lutter contre toutes les formes de puritanisme, contre le culte des parades et de la gloriole propre au wilhelminisme, contre la prussianisation de l’Allemagne du Sud (“Simplicissimus” lutte à la fois contre le prussianisme et le catholicisme, la Prusse étant perçue comme un “Etat rationnel”, trop sérieux et donc “ennemi de la Vie”), contre le passéisme bigot et rural de la Bavière. On peut dès lors constater que la revue joue sur un éventail d’éléments culturels et politiques présents en Bavière depuis les années 70 du 19ème siècle. Le symbole de la revue est un “bouledogue rouge”, dont les dents symbolisent l’humour agressif et le mordant satirique que la revue veut incarner. Le mot d’ordre des fondateurs du “Simplicissimus” est donc “bissig sein”, “être mordant”. Cette attitude, prêtée au bouledogue rouge, veut faire comprendre au public que la revue n’adoptera pas le ton des prêcheurs moralistes, qu’elle n’entend pas répéter inlassablement des modes de pensée fixes et inaltérables, tous signes patents d’une “mort spirituelle”. En effet, selon Dilthey (puis selon l’heideggerien Hans Jonas), on ne peut définir une chose que si elle est complètement morte, donc incapable de produire du nouveau, par l’effet de sa vitalité, même atténuée.

En 1896 se crée à Munich la fameuse revue satirique “Simplicissimus” qui, d’emblée, se donne pour tâche de lutter contre toutes les formes de puritanisme, contre le culte des parades et de la gloriole propre au wilhelminisme, contre la prussianisation de l’Allemagne du Sud (“Simplicissimus” lutte à la fois contre le prussianisme et le catholicisme, la Prusse étant perçue comme un “Etat rationnel”, trop sérieux et donc “ennemi de la Vie”), contre le passéisme bigot et rural de la Bavière. On peut dès lors constater que la revue joue sur un éventail d’éléments culturels et politiques présents en Bavière depuis les années 70 du 19ème siècle. Le symbole de la revue est un “bouledogue rouge”, dont les dents symbolisent l’humour agressif et le mordant satirique que la revue veut incarner. Le mot d’ordre des fondateurs du “Simplicissimus” est donc “bissig sein”, “être mordant”. Cette attitude, prêtée au bouledogue rouge, veut faire comprendre au public que la revue n’adoptera pas le ton des prêcheurs moralistes, qu’elle n’entend pas répéter inlassablement des modes de pensée fixes et inaltérables, tous signes patents d’une “mort spirituelle”. En effet, selon Dilthey (puis selon l’heideggerien Hans Jonas), on ne peut définir une chose que si elle est complètement morte, donc incapable de produire du nouveau, par l’effet de sa vitalité, même atténuée.

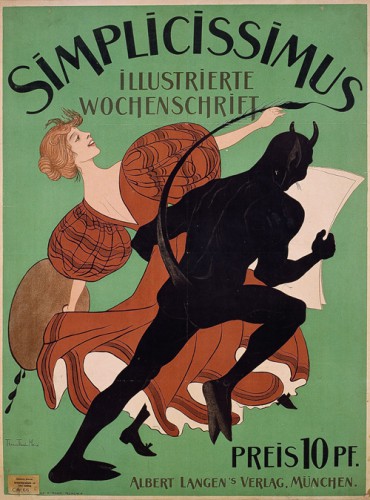

L’homme qui se profile derrière la revue “Simplicissimus”, en abrégé “Der Simpl’”, est Albert Langen (fondateur d’une maison d’édition qui existe toujours sous le nom de “Langen-Müller”). Il est alors âgé de 27 ans. Il rejette le wilhelminisme comme David Herbert Lawrence rejetait le victorianisme en Angleterre ou August Strindberg l’oscarisme en Suède. Cette position anti-wilhelminienne ne participe pas d’une hostilité au patriotisme allemand: au contraire, Albert Langen veut, pour la nation, contribuer à faire éclore des idéaux combattifs, finalement assez agressifs. Les modèles dont il s’inspire pour sa revue sont français car en France existe une sorte de “métapolitique satirique”, incarnée, entre autres initiatives, par le “Gil Blas illustré”. Pour confectionner le pendant allemand de cette presse parisienne irrévérencieuse, Langen recrute Ludwig Thoma, virtuose des injures verbales, comme le seront aussi un Léon Daudet en France ou un Léon Degrelle en Belgique; ensuite l’Israélite Thomas Theodor Heine, excellent caricaturiste qui fustigeait les philistins, les ploutocrates, les fonctionnaires et les officiers. Le dramaturge Frank Wedekind se joint au groupe rédactionnel pour railler les hypocrisies de la société moderne, industrialisée et urbanisée. Langen, Heine et Wedekind finissent par être, à leur tour, poursuivis pour crime de lèse-majesté. Langen s’exile à Paris. Heine écope de six mois de prison et Wedekind de sept mois. Du coup, la revue, qui tirait à 15.000 exemplaires, peut passer à un tirage de 85.000.

Pour une armée nouvelle

Les moqueries adressées à la personne de l’Empereur ne signifient pas que nos trois auteurs niaient la nécessité d’une autorité monarchique ou impériale. Au contraire, leur objectif est de rétablir l’autorité de l’Etat face à un monarque qui est “pose plutôt que substance”, attitude risible, estiment-ils, qui s’avère dangereuse pour la substance politique du IIème Reich. Les poses et les parades du wilhelminisme sont la preuve, disaient-ils, d’une immaturité politique dangereuse face à l’étranger, plus équilibré et moins théâtral dans ses affirmations. S’ils critiquaient la caste des officiers modernes, recrutés hors des catégories sociales paysannes et aristocratiques traditionnellement pourvoyeuses de bons soldats, c’est parce que ces nouveaux officiers modernes étaient brutaux et froids et non plus sévères et paternels: nos auteurs plaident pour une armée efficace, soudée, capable de prester les tâches qu’on réclame d’elle. De même, notre trio du “Simpl’”, derrière leurs satires, réclament une meilleure formation technique de la troupe et fustigent l’anti-militarisme des sociaux-démocrates.

Les moqueries adressées à la personne de l’Empereur ne signifient pas que nos trois auteurs niaient la nécessité d’une autorité monarchique ou impériale. Au contraire, leur objectif est de rétablir l’autorité de l’Etat face à un monarque qui est “pose plutôt que substance”, attitude risible, estiment-ils, qui s’avère dangereuse pour la substance politique du IIème Reich. Les poses et les parades du wilhelminisme sont la preuve, disaient-ils, d’une immaturité politique dangereuse face à l’étranger, plus équilibré et moins théâtral dans ses affirmations. S’ils critiquaient la caste des officiers modernes, recrutés hors des catégories sociales paysannes et aristocratiques traditionnellement pourvoyeuses de bons soldats, c’est parce que ces nouveaux officiers modernes étaient brutaux et froids et non plus sévères et paternels: nos auteurs plaident pour une armée efficace, soudée, capable de prester les tâches qu’on réclame d’elle. De même, notre trio du “Simpl’”, derrière leurs satires, réclament une meilleure formation technique de la troupe et fustigent l’anti-militarisme des sociaux-démocrates.

Sur le plan géopolitique, la revue “Simplicissimus” a fait preuve de clairvoyance. En 1903, elle réclame une attitude allemande plus hostile aux Etats-Unis, qui viennent en 1898 d’arracher à l’Espagne les Philippines et ses possessions dans les Caraïbes, l’Allemagne héritant de la Micronésie pacifique auparavant hispanique. L’Allemagne et l’Europe, affirmaient-ils, doivent trouver une réponse adéquate à la Doctrine de Monroe, qui vise à interdire le Nouveau Monde aux vieilles puissances européennes et à une politique agressive de Washington qui chasse les Européens du Pacifique, en ne tenant donc plus compte du principe de Monroe, “l’Amérique aux Américains”. Le “Simpl’” adopte ensuite une attitude favorable au peuple boer en lutte contre l’impérialisme britannique. Il est plus souple à l’égard de la France (qui avait offert l’asile politique à Langen). Il est en revanche hostile à la Russie, alliée traditionnelle de la Prusse.

Les cabarets

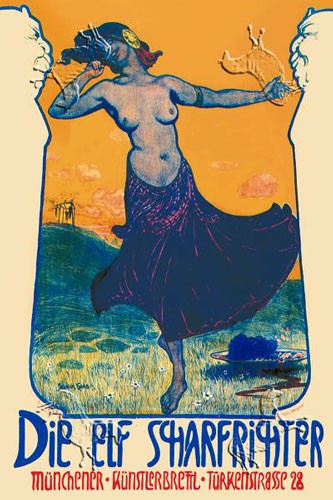

A côté du “Simplicissimus”, le Munich de la première décennie du 20ème siècle voit naître le cabaret “Die Elf Scharfrichter” (“Les onze bourreaux”) qui marquera durablement la chronique entre 1901 et 1903. Ce cabaret, lui aussi, se réfère à des modèles étrangers ou non bavarois: “Le chat noir” de Paris, “Il quatre cats” de Barcelone, le “Bat” de Moscou et l’“Überbrettl” de Berlin. Les inspirateurs français de ce cabaret munichois étaient Marc Henry et Achille Georges d’Ailly-Vaucheret. Mais Berlinois et Bavarois appliquent les stratégies du rire et de l’arrachage des masques préconisées par Nietzsche. En effet, la référence au comique, à l’ironie et au rire chez Nietzsche est évidente: des auteurs contemporains comme Alexis Philonenko ou Jenny Gehrs nous rappellent l’importance critique de ce rire nietzschéen, antidote précieux contre les routines, les ritournelles des conformistes et des pharisiens puis, aujourd’hui, contre la critique aigre et inféconde lancée par l’Ecole de Francfort et Jürgen Habermas. Jenny Gehrs démontre que les cabarets et leur pratique de la satire sont étroitement liés aux formes de critique que suggérait Nietzsche: pour celui-ci, l’ironie déconstruit et détruit les systèmes de valeurs et les modes de pensée qui figent et décomposent par leurs raideurs et leur incapacité vitale à produire de la nouveauté féconde. L’ironie est alors expression de la joie de vivre, de la légèreté d’âme, ce qui n’induit pas une absence de sériosité car le comique, l’ironie et la satire sont les seules voies possibles pour échapper à l’ère du nihilisme, les raideurs, rigidités, pesanteurs ne produisant que “nihil”, tout comme le “politiquement correct” et les conventions idéologiques de notre temps ne produisent aucune pensée féconde, aucune pensée capable de sortir des ornières où l’idéologie et les praxis dominantes se sont enlisées. La pratique de l’ironie implique d’adopter une pensée radicale complètement dépourvue d’indulgence pour les conventions établies qui mutilent et ankylosent les âmes. L’art, pour nos contestataires munichois comme pour Jenny Gehrs, est le moyen qu’il faut déployer pour détruire les raideurs et les rigidités qui mènent le monde à la mort spirituelle. Alexis Philonenko rappelle que sans le rire, propre de l’homme selon Bergson, les sociétés basculent à nouveau dans l’animalité et ruinent les ressorts et les matrices de leur propre culture de base. Si ne règnent que des constructions idéalisées (par les médiacrates par exemple) ou posées comme indépassables ou éternelles, comme celle de la pensée unique, de la bien-pensance ou du “politiquement correct”, le monde sombrera dans la mélancolie, signe du nihilisme et du déclin de l’homme européen. Dans ce cas, il n’y a déjà plus de perspectives innovantes, plus aucune possibilité de faire valoir nuances ou diversités. Le monde devient gris et terne. Pour nos cabaretistes munichois, le wilhelminisme était une praxis politique dominante qui annonçait déjà ce monde gris à venir, où l’homme ne serait plus qu’un pantins aux gestes répétitifs. Il fallait réagir à temps, imméditement, pour que la grisaille envahissante ne dépasse pas la première petite étape de son oeuvre de “monotonisation”.

A côté du “Simplicissimus”, le Munich de la première décennie du 20ème siècle voit naître le cabaret “Die Elf Scharfrichter” (“Les onze bourreaux”) qui marquera durablement la chronique entre 1901 et 1903. Ce cabaret, lui aussi, se réfère à des modèles étrangers ou non bavarois: “Le chat noir” de Paris, “Il quatre cats” de Barcelone, le “Bat” de Moscou et l’“Überbrettl” de Berlin. Les inspirateurs français de ce cabaret munichois étaient Marc Henry et Achille Georges d’Ailly-Vaucheret. Mais Berlinois et Bavarois appliquent les stratégies du rire et de l’arrachage des masques préconisées par Nietzsche. En effet, la référence au comique, à l’ironie et au rire chez Nietzsche est évidente: des auteurs contemporains comme Alexis Philonenko ou Jenny Gehrs nous rappellent l’importance critique de ce rire nietzschéen, antidote précieux contre les routines, les ritournelles des conformistes et des pharisiens puis, aujourd’hui, contre la critique aigre et inféconde lancée par l’Ecole de Francfort et Jürgen Habermas. Jenny Gehrs démontre que les cabarets et leur pratique de la satire sont étroitement liés aux formes de critique que suggérait Nietzsche: pour celui-ci, l’ironie déconstruit et détruit les systèmes de valeurs et les modes de pensée qui figent et décomposent par leurs raideurs et leur incapacité vitale à produire de la nouveauté féconde. L’ironie est alors expression de la joie de vivre, de la légèreté d’âme, ce qui n’induit pas une absence de sériosité car le comique, l’ironie et la satire sont les seules voies possibles pour échapper à l’ère du nihilisme, les raideurs, rigidités, pesanteurs ne produisant que “nihil”, tout comme le “politiquement correct” et les conventions idéologiques de notre temps ne produisent aucune pensée féconde, aucune pensée capable de sortir des ornières où l’idéologie et les praxis dominantes se sont enlisées. La pratique de l’ironie implique d’adopter une pensée radicale complètement dépourvue d’indulgence pour les conventions établies qui mutilent et ankylosent les âmes. L’art, pour nos contestataires munichois comme pour Jenny Gehrs, est le moyen qu’il faut déployer pour détruire les raideurs et les rigidités qui mènent le monde à la mort spirituelle. Alexis Philonenko rappelle que sans le rire, propre de l’homme selon Bergson, les sociétés basculent à nouveau dans l’animalité et ruinent les ressorts et les matrices de leur propre culture de base. Si ne règnent que des constructions idéalisées (par les médiacrates par exemple) ou posées comme indépassables ou éternelles, comme celle de la pensée unique, de la bien-pensance ou du “politiquement correct”, le monde sombrera dans la mélancolie, signe du nihilisme et du déclin de l’homme européen. Dans ce cas, il n’y a déjà plus de perspectives innovantes, plus aucune possibilité de faire valoir nuances ou diversités. Le monde devient gris et terne. Pour nos cabaretistes munichois, le wilhelminisme était une praxis politique dominante qui annonçait déjà ce monde gris à venir, où l’homme ne serait plus qu’un pantins aux gestes répétitifs. Il fallait réagir à temps, imméditement, pour que la grisaille envahissante ne dépasse pas la première petite étape de son oeuvre de “monotonisation”.

Franziska zu Reventlow

Franziska zu Reventlow est la figure féminine qui opère la jonction entre ce Schwabing anarchisant et la “révolution conservatrice” proprement dite, parce qu’elle a surtout fréquenté le cercle des Cosmiques autour de Stefan George, où se manifestaient également deux esprits profonds, Alfred Schuler et Ludwig Klages, dont la pensée n’a pas encore été entièrement exploitée jusqu’ici en tous ses possibles. David Clay Large définit la vision du monde de Franziska zu Reventlow comme “un curieux mélange d’idées progressistes et réactionnaires”. Surnommée la “Reine de Schwabing”, elle est originaire d’Allemagne du Nord, de Lübeck, d’une famille aristocratique connue, mais, très tôt, elle a rué dans les brancards, sa nature rebelle passant outre toutes les conventions sociales. La lecture du Norvégien Ibsen —il y avait un “Ibsen-Club” à Lübeck— du Français Emile Zola, du socialiste allemand Ferdinand Lassalle et, bien entendu, de Friedrich Nietzsche, dont le “Zarathoustra” constituait sa “source sacrée” (“geweihte Quelle”). Elle arrive à Schwabing à 22 ans et, aussitôt, Oskar Panizza la surnomme “la Vénus du Slesvig-Holstein” (“Die schleswig-holsteinsche Venus”), tout en ajoutant, perfide, qu’elle était “très sale”. Les frasques de Franziska ont choqué sa famille qui l’a déshéritée. A Munich, elle crève de faim, ne prend qu’un maigre repas par jour et se came au laudanum pour atténuer les douleurs qui l’affligent. Rapidement, elle collectionne quelques dizaines d’amants, se posant comme “mère libre” (“freie Mutter”) et devenant ainsi l’icône du mouvement féministe, une sorte de “sainte païenne”.

Franziska zu Reventlow est la figure féminine qui opère la jonction entre ce Schwabing anarchisant et la “révolution conservatrice” proprement dite, parce qu’elle a surtout fréquenté le cercle des Cosmiques autour de Stefan George, où se manifestaient également deux esprits profonds, Alfred Schuler et Ludwig Klages, dont la pensée n’a pas encore été entièrement exploitée jusqu’ici en tous ses possibles. David Clay Large définit la vision du monde de Franziska zu Reventlow comme “un curieux mélange d’idées progressistes et réactionnaires”. Surnommée la “Reine de Schwabing”, elle est originaire d’Allemagne du Nord, de Lübeck, d’une famille aristocratique connue, mais, très tôt, elle a rué dans les brancards, sa nature rebelle passant outre toutes les conventions sociales. La lecture du Norvégien Ibsen —il y avait un “Ibsen-Club” à Lübeck— du Français Emile Zola, du socialiste allemand Ferdinand Lassalle et, bien entendu, de Friedrich Nietzsche, dont le “Zarathoustra” constituait sa “source sacrée” (“geweihte Quelle”). Elle arrive à Schwabing à 22 ans et, aussitôt, Oskar Panizza la surnomme “la Vénus du Slesvig-Holstein” (“Die schleswig-holsteinsche Venus”), tout en ajoutant, perfide, qu’elle était “très sale”. Les frasques de Franziska ont choqué sa famille qui l’a déshéritée. A Munich, elle crève de faim, ne prend qu’un maigre repas par jour et se came au laudanum pour atténuer les douleurs qui l’affligent. Rapidement, elle collectionne quelques dizaines d’amants, se posant comme “mère libre” (“freie Mutter”) et devenant ainsi l’icône du mouvement féministe, une sorte de “sainte païenne”.

Quel est le “féminisme” de Franziska zu Reventlow? Ce n’est évidemment pas celui qui domine dans les esprits de nos jours ou qui a animé le mouvement des suffragettes. Pour la Vénus de Schwabing, le mouvement de libération des femmes ne doit pas demander à ce qu’elles puissent devenir banquières ou courtières en assurances ou toute autre horreur de ce genre. Non, les femmes vraiment libérées, pour Franziska zu Reventlow, doivent incarner légèreté, beauté et joie, contrairement aux émancipées acariâtres que nous avons connues naguère, les “Emanzen” dont se moquent aujourd’hui les Allemands. Franziska les appelaient déjà les “sombres viragos” (“Die finstere Viragines”). Si les femmes libérées ne deviennent ni légères ni belles ni joyeuses le monde deviendra atrocement ennuyeux et sombrera dans la névrose, bannissant en même temps toute forme charmante d’érotisme.

Les “Cosmiques” de Schwabing

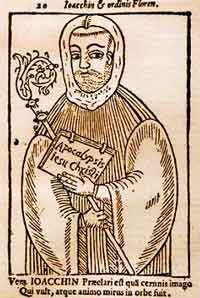

Malgré le scandale que suscite ses positions féministes et libératrices, Franziska zu Reventlow demeure d’une certaine manière “conservatrice” car elle valorise le rôle de la femme en tant que mère biologique, dispensatrice de vie mais aussi d’éducation. La femme doit communiquer le sens de la beauté à ses enfants, les plonger dans le patrimoine littéraire de leur nation et de l’humanité toute entière. Cette double fonction, à la fois révolutionnaire et conservatrice, Franziska zu Reventlow la doit à sa fréquentation du cercle des “Cosmiques” de Schwabing, autour de Karl Wolfskehl et Stefan George, d’une part, d’Alfred Schuler et Ludwig Klages, d’autre part, avant la scission du groupe en deux clans bien distincts. Les “Cosmiques”, au nom d’une esthétique à la fois grèco-romaine, médiévisante et romantique, teintée de pré-raphaélisme et d’Art nouveau, présentaient tous les affects anti-industriels de l’époque, déjà repérables chez leurs prédécesseurs anglais; ils vont également renouer avec l’anti-rationalisme des premiers romantiques et manifester des affects anti-parlementaires: la raison conduit, prétendaient-ils, aux horreurs industrielles de la sur-urbanisation inesthétique et aux parlottes stériles des députés incultes, qui se prennent pour des émules de Socrate en n’émettant que de purs discours dépourvus de tous sentiments. Les “Cosmiques” toutefois ne renouent pas avec le christianisme romantique d’un Novalis, par exemple: ils déploient, surtout chez Schuler et Klages, une critique radicale du christianisme et entendent retourner aux sources païennes de la culture européenne pré-hellénique qu’ils appeleront “tellurique”, “chtonienne” ou “pélasgique”. Ce paganisme est, en filigrane, une révolte contre les poncifs catholiques du conservatisme bavarois qui n’abordent la spiritualité ou la “carnalité” de l’homme qu’en surface, avec la suffisance du pharisaïsme: pour les “Cosmiques”, “il existe des chemins sombres et secrets”, qu’il faudra redécouvrir pour redonner une “aura” à la culture, pour la ramener à la lumière. Franziska zu Reventlow, dans ses souvenirs de Schwabing, où elle se moque copieusement des “Cosmiques”, dont certains étaient tout-à-fait insensibles aux séductions de la féminité, que les hommes et les femmes qui emprunteront ces voies “sombres et secrètes” seront les initiés de demain, les “Enormes” (“Die Enormen”), tandis que ceux qui n’auront jamais l’audace de s’y aventurer ou qui voudront les ignorer au nom de conventions désuètes ou étriquées, seront les “Sans importance” (“Die Belanglosen”).

De Bachofen à Klages

Si Stefan George a été le poète le plus célèbre du groupe des “Cosmiques”, Ludwig Klages, qui se détachera du groupe en 1904, en a indubitablement été le philosophe le plus fécond, encore totalement inexploré aujourd’hui en dehors des frontières de la germanophonie. Figure de proue de ce qu’Armin Mohler a défini comme la “révolution conservatrice”, Klages ne basculera jamais dans une tentation politique quelconque; il étudiera Bachofen et Nietzsche, fusionnera leur oeuvre dans une synthèse qui se voudra “chtonienne” ou “tellurique”, tout en appliquant ses découvertes philosophiques à des domaines très pratiques comme la science de l’expression, dont les chapitres sur la graphologie le rendront mondialement célèbre. La postérité a surtout retenu de lui cette dimension de graphologue, sans toutefois vouloir se rappeler que la graphologie de Klages est entièrement tributaire de son interprétation des oeuvres de Bachofen et Nietzsche. En effet, Klages a été l’un des lecteurs les plus attentifs du philosophe et philologue bâlois Bachofen, issu des facultés de philologie classique de Bâle, tout comme Nietzsche. Klages énonce, suite à Bachofen, une théorie du matriarcat primordial, expression spontanée et non détournée de la Vie mouvante et fluide que le patriarcat a oblitéré au nom de l’Esprit, censé rigidifier les expressions vitales. L’histoire du monde est donc une lutte incessante entre la Vie et l’Esprit, entre la culture (matriarcale) et la civilisation (patriarcale). Alfred Schuler, mentor de Klages mais qui n’a laissé derrière lui que des fragments, mourra lors d’une intervention chirurgicale en 1923; Klages s’exilera en Suisse, où il décédera en 1956, après avoir peaufiné son oeuvre qui attend encore et toujours d’être pleinement explorée dans diverses perspectives: écologie, géophilosophie, proto-histoire, etc. Quant à Franziska zu Reventlow, elle quittera Munich pour une autre colonie d’artistes basée à Ascona en Suisse, une sorte de nouveau Schwabing avec, en plus, l’air tonifiant des Alpes tessinoises. Elle y mourra en 1918.

Thomas Mann patriote

La guerre de 1914 balaie le monde de Schwabing, que les conservateurs aigris voulaient voir disparaître, pour qu’il ne puisse plus les ridiculiser. Bon nombre d’artistes s’engagent dans l’armée, dont le poète Richard Dehmel et les peintres August Macke et Franz Marc (du groupe “Blauer Reiter”, le “Cavalier bleu”) qui, tous deux, ne reviendront pas des tranchées. Le “Simplicissimus” cesse de brocarder cruellement les officiers, ces “analphabètes en uniforme”, et les généraux, ces “sombres simplets”, et devient un organe patriotique intransigeant, sous prétexte qu’en temps de guerre, quand la patrie est en danger, “les muses doivent se taire” et qu’il faut participer “à une guerre qui nous est imposée” et “au combat pour défendre la culture menacée par l’étranger (belliciste)”. Thomas Mann participe à l’effort de guerre en opposant la culture (vivante, tirée d’un humus précis) à la civilisation dans un opuscule patriotique intitulé “Gedanken im Kriege” (“Idées en temps de guerre”). La culture (allemande) pour Mann, en cette fin août 1914, est “homogénéité, style, forme, attitude et bon goût”. Quant à la “civilisation”, représentée par l’Ouest, elle est “rationalité (sèche), esprit des Lumières, édulcoration, moralisme, scepticisme et dissolution”. La tâche de l’Allemagne, dans cette guerre est de défendre la fécondité vitale de la culture contre les attaques de la civilisation qui entend “corseter” les âmes, leur faire perdre leurs élans, édulcorer la littérature et la musique qui ne peuvent se développer que sur un terreau “culturel” et non “civilisationnel”. Ces idées nationales de Thomas Mann sont consignées dans “Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen” (“Considérations d’un apolitique”). Son frère Heinrich Mann, en revanche, plaidait pour une civilisation marquée par l’humanisme de Zola, adepte d’une justice pour chaque individu, au-delà de toute institution ou cadre politique, un Zola qui s’était précisément hissé, lors de l’affaire Dreyfus, au-dessus des institutions politiques de la France: pour Heinrich, Thomas aurait dû prendre une position similaire à l’auteur du “J’accuse” et se hisser au-dessus de l’idée patriotique et de l’Etat semi-autoritaire du wilhelminisme. A partir des années vingt, les deux frères se réconcilieront sur base des idées “occidentales” de Heinrich.

Noire vision spenglerienne

Oswald Spengler était revenu à Munich en 1911, après y avoir passé une année d’étude en 1901: toujours amoureux de la ville bavaroise, il était cependant déçu en s’y réinstallant. Il ne retrouvait plus intact le style classique de Louis I, y découvrait en revanche “l’ornementalisme imbécile” de l’“Art Nouveau” et les “escroqueries expressionnistes”, toutes expressions du déclin qui affecte l’Europe entière. Pour Spengler, qui s’apprête à rédiger sa somme “Der Untergang des Abendlandes”, les affres de décadence qui marquent Munich sont autant de symboles du déclin général de l’Europe, trop influencée par les idées “civilisatrices”. Pour Spengler, la transition entre, d’une part, la phase juvénile que constitue toute culture, créatrice et d’abord un peu fruste, et, d’autre part, la phase sénescente de la civilisation, s’opère inéluctablement, comme une loi biologique et naturelle. Les hommes —les porteurs et les vecteurs de culture vieillissants— se mettent à désirer le confort et le raffinement, abandonnent les exigences créatrices de leur culture de départ, n’ont plus la force juvénile d’innover: tous les peuples d’Occident subiront ce processus de sénescence pour en arriver d’abord à un stade de lutte planétaire entre “pouvoirs césariens”, ensuite à un stade d’uniformité généralisée, à une ère des masses abruties, parquées dans des villes tentaculaires, dont l’habitat sera constitué de “casernements” sordides et sans charme. Ces masses recevront, comme dans le Bas-Empire, du pain et des jeux. Tel est, en gos, le processus de déclin que Spengler a voulu esquisser dans “Der Untergang des Abendlandes”.

Le déclin de Munich et de toute l’Europe était donc en germe avant le déclenchement de la première grande conflagration intereuropéenne. La guerre accélère le processus. Au lendemain de l’armistice de novembre 1918, nous aurons donc affaire à un autre Munich et à une autre Europe. Une autre histoire, bien différente, bien plus triste, pouvait commencer: celle de l’après-Schwabing. Avant d’assister à la lutte plénétaire entre les nouveaux Césars (Hitler, Staline, Churchill, Roosevelt). Après la victoire du César américain, l’ère des masses abruties par la consommation effrénée et par le confort matériel a commencé. Nous y sommes toujours, malgré les ressacs dus aux crises: l’aura des Cosmiques n’élit plus personne. Les masses abruties sont là, omniprésentes. Les villes tentaculaires détruisent les cultures, au Japon, au Mexique, en Afrique. Et pas seulement en Europe et en Amérique du Nord. Les jeux virtuels sont distribués à profusion. Spengler avait raison.

Robert Steuckers.

(Forest-Flotzenberg, Vlotho im Wesergebirge, été 2002).

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Révolution conservatrice, Synergies européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : allemagne, révolution conservatrice, munich, bavière, histoire, schwabing |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 25 octobre 2013

Conversations with History: Robert Fisk

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : robert fisk, histoire, entretien |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 24 octobre 2013

Conversations with History: Howard Zinn

00:09 Publié dans Entretiens, Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : howard zinn, entretien, history, radical history, histoire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 22 octobre 2013

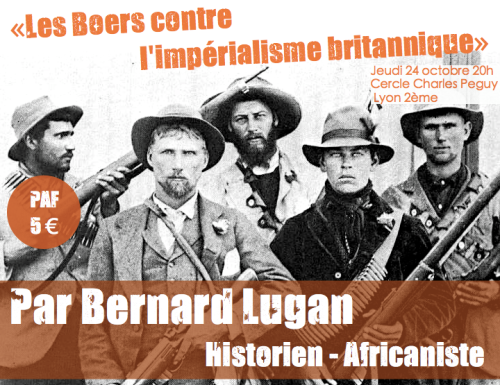

B. Lugan: les Boers contre l'impérialisme

16:28 Publié dans Evénement, Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : bernard lugan, histoire, événement, afrique du sud, afrique, affaires africaines, boers, impérialisme britannique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Conversations with History: Chalmers Johnson

00:04 Publié dans Actualité, Entretiens, Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : chalmers johnson, histoire, entretien, états-unis, déclin américain, impérialisme, impérialisme américain |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 19 octobre 2013

UN PEUPLE PEU CONNU : LES SARMATES

Jean Pierinot

Ex: http://metamag.fr

00:05 Publié dans archéologie, Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : sarmates, archéologie, antiquité, proto-histoire, histoire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 16 octobre 2013

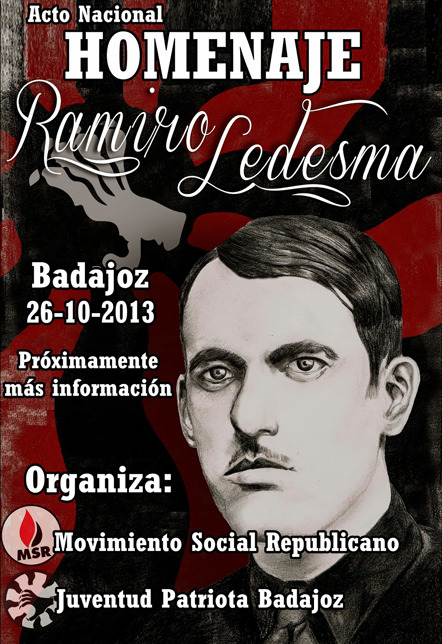

Ramiro Ledesma Ramos

00:05 Publié dans Evénement, Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, espagne, événement, badajoz |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 03 octobre 2013

UN REGARD SUR LES TRENTE GLORIEUSES

Pierre LE VIGAN

Ex: http://metamag.fr

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, france, trente glorieuses, livre |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 02 octobre 2013

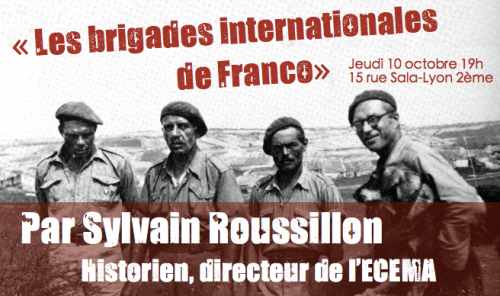

Brigades internationales de Franco

00:05 Publié dans Evénement, Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : événement, lyon, histoire, espagne, guerre civile espagnole, guerre d'espagne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 01 octobre 2013

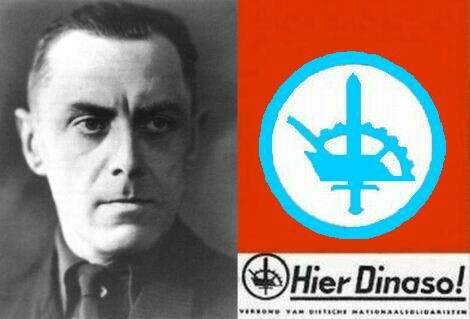

De verloren erfenis van het Verdinaso

De verloren erfenis van het Verdinaso

Een overzichtsgeschiedenis van het naoorlogse Heel-Nederlandisme en solidarisme

Filip MARTENS

De intellectueel Joris Van Severen (1894-1940) is zonder enige twijfel de meest briljante Vlaamse geest geweest van de laatste 90 jaar. Hij had tevens een zeer sterke en indrukwekkende persoonlijkheid. Na zijn dood in 1940 bleef de door hem gestichte beweging Verdinaso verder leven in de harten van duizenden sympathisanten, die decennialang in neo-Dinaso-groeperingen actief bleven.

Inleiding

De maatschappelijke ideeën van nationale bewegingen kunnen sterk uiteenlopen, daar ze bepaald worden door de context waarin hun staatkundige opvattingen zich ontwikkelen. Nationalisme versmelt steeds staatkundige en maatschappelijke ideeën tot één ondeelbaar geheel. Het Verdinaso vertolkte dit zeer goed met de leuze “Het Dietsche Rijk en Orde”.

Dit blijkt ook uit de ideologische evolutie van Joris Van Severen. Vanuit een katholieke familiale afkomst over flamingantische bezigheden tijdens zijn universiteitsjaren beleefde hij door de oorlogsgruwelen een nationaal-revolutionair ontwaken aan het IJzerfront. Vanaf 1923 ontwikkelde Van Severen een katholiek Groot-Nederlands nationalisme met Italiaans-fascistische inspiratie en vormgeving. Na 1934 plooide hij stelselmatig terug op een Heel-Nederlands revolutionair conservatisme, waarbij de katholieke fundamenten het haalden op de nationaal-socialistische en fascistische modes. Zijn laatste ontwikkelingsstadium vertoont sterke gelijkenissen met de Franse en Duitse Jong-Conservatieven.

Joris Van Severen evolueerde ook in zijn afbakening van de natiestaat. Oorspronkelijk was hij een vurige anti-Belgische flamingant. De romantische zinspreuk “De taal is gansch het volk” was toen voor hem – en voor heel het flamingantisme – de voornaamste maatstaf voor nationale identiteit. Bijgevolg kon België geen natiestaat zijn en moest er een ‘Vlaams’ volk bestaan dat nauw verwant was aan Nederland.

Van Severen stichtte in oktober 1931 het solidaristische en volksnationalistische Verbond van Dietsche Nationaal-Solidaristen (Verdinaso) na een reeks teleurstellingen in de partijpolitiek. Het taalcriterium werd nog geradicaliseerd door het flamingantisme als overbodige tussenstap overboord te gooien: er bestond enkel nog een ‘Diets’ volk in Nederland, Noord-België en Frans-Vlaanderen. Deze niet-partijpolitieke organisatie was dus bij de aanvang Groot-Nederlands en wou een ideologische en leidinggevende elite vormen. Reeds in 1932 wou Van Severen overschakelen op een staatsnationalistische koers, omdat hij inzag dat enerzijds de regering verregaande maatregelen tegen zijn beweging zou nemen en anderzijds de macht over de Belgische staat diende te worden verworven. De invloedrijke Wies Moens kon dit echter nog 2 jaar tegenhouden.

Het openlijk militaristische – met de Dietsche Militie (DM) had het Verdinaso immers een eigen militie – en als staatsgevaarlijk beschouwde Verdinaso kreeg vanaf eind 1933 zeer ernstige moeilijkheden met de Staatsveiligheid: vele huiszoekingen bij en intimidaties van Verdinaso-leiders, uitsluiting van de Verdinaso-vakbond, een speciale wet om de DM te verbieden, … Daarop gooide Van Severen het roer om door het taalnationalisme af te zwakken: zogenaamde “lotsverbonden volkeren” als de Walen, de Luxemburgers en de Friezen waren welkom in de Dietse volksstaat als ze dat wensten. De DM werd omgevormd tot Dinaso Militanten Orde (DMO) en voor het natieverdelende opbod tussen Nederlandstalig en Franstalig België was geen plaats meer. Het Verdinaso refereerde hiermee aan de 15de eeuwse Bourgondisch-Habsburgse Nederlanden. Wies Moens verliet hierop het Verdinaso. Nochtans kwam de fundamentele evolutie in Van Severens staatkundige denken pas later, doch dit viel echter minder op door de geleidelijke evolutie ervan.

De afkondiging van deze (1ste) Nieuwe Marsrichting betekende een duidelijke afname van Van Severens etno-culturele nationalisme ten voordele van de Rijksgedachte. Van Severen werd vanaf dan een gerespecteerd figuur binnen de Belgische adel en aan het koninklijk hof, die met zijn mening terdege rekening hielden. Hij streefde er naar dat koning Albert I hem zou benoemen tot premier, zodat hij een corporatistische staat kon installeren. De koning moest tevens meer bevoegdheden krijgen.

Inzake maatschappelijke ideeën beriep Van Severen zich op de Conservatieve Revolutie. Dit hield een afwijzing in van de Franse Revolutie, de op vrijmetselaarsprincipes gestoelde grondwet, liberalisme, kapitalisme, marxisme, conservatisme, parlementaire democratie en politieke partijen. Het Verdinaso stelde dat politieke partijen moesten verdwijnen omdat ze het organisch karakter van de volksgemeenschap miskenden en elk voor zich streefden naar de macht, zich slaafs lieten misbruiken door de financiële wereld en aldus “de wettige organisatie van het verraad aan en van de uitplundering van het volk” zijn. Tevens werd gepleit voor een organische samenleving gebaseerd op solidarisme en corporatisme die echte democratie inhielden. Dit omvatte een vervanging van de verfoeide parlementaire democratie – de “demoliberale chaos” – door een corporatieve maatschappelijke ordening. Er was ook een behoudsgezind katholicisme aanwezig. Voor dit alles haalde Van Severen zijn inspiratie onder meer bij de pauselijke encyclieken ‘Rerum Novarum’ en ‘Quadragesimo Anno’, de Action française van Charles Maurras (1868-1952), het neothomisme van Jacques Maritain (1882-1973), de katholieke socioloog markies René de la Tour du Pin (1834-1924) en Mussolini’s nieuwe interpretatie van corporatisme. Van Severen vatte de maatschappelijke ideeën van het Verdinaso samen onder de noemer ‘nationaal-solidarisme’.

Het Verdinaso hanteerde een staatkundige visie die niet zozeer Vlaams-regionalistisch was, maar het grotere geheel der volkeren in de Lage Landen beschouwde. Hiermee oversteeg het Verdinaso duidelijk het romantisch-dromerige flamingantisme. De evoluerende staatkundige visie van het Verdinaso toont aan dat voor de achterban de maatschappelijke opvattingen primeerden. Er haakten wel heel wat mensen af, maar de meesten bleven: noch Groot-Nederlandisme, noch anti-Belgicisme waren voor het gros der Dinaso’s essentieel voor het revolutionair gedachtegoed.

Bovendien was het Verdinaso totaal onafhankelijk van buitenlandse machten. Van Severen weigerde immers consequent financiering en inmenging van nazi-Duitsland, dat eerder als ‘goede en nauw verwante buur’ werd gezien. Dit in tegenstelling tot de slaafse knechtenmentaliteit tegenover Duitsland van het flamingantisch-regionalistische VNV in de ijdele hoop dat de Duitsers hen een zelfstandig Vlaanderen zouden geven. Het VNV werd dan ook reeds lang vóór de Tweede Wereldoorlog gefinancierd en gestuurd door Duitsland.

Vanaf augustus 1936 liet Van Severen de term ‘Dietsland’ vallen. Voortaan sprak hij achtereenvolgens over “het Dietse Rijk”, “de Lage Landen”, “de Nederlanden”, “het Dietse Rijk der Nederlanden” en tenslotte vanaf 1938 over “de Zeventien Provinciën”. Vanaf deze 2de Nieuwe Marsrichting moest België niet langer verdwijnen, maar moest de macht gegrepen worden binnen België mét Waalse steun, waarna moest gestreefd worden naar een fusie met Nederland en Luxemburg. Het taalcriterium werd nu volledig verlaten en vervangen door geopolitieke argumenten en het gemeenschappelijk verleden der Nederlanden, terwijl de eeuwenoude lotsverbonden gemeenschap van Dietsers, Friezen, Walen en Luxemburgers diende hersteld te worden door staatkundige eenmaking in een rijksgemeenschap. In dit de facto herstelde Verenigd Koninkrijk der Nederlanden zou de verscheidenheid der Dietsers gevrijwaard worden door provinciaal federalisme.

Deze evolutie was staatkundig veel fundamenteler dan de 1ste Nieuwe Marsrichting van 1934. Met deze 2de Nieuwe Marsrichting verliet dan ook ongeveer één derde der leden het Verdinaso. Pas tegen 1939 stabiliseerde het ledenaantal weer. Het Verdinaso kon nu echter ook andere doelgroepen aanspreken: Franstalige Vlamingen, Belgisch-nationalistische Vlamingen en ook … Walen. Met de 2de Nieuwe Marsrichting werden tevens alle Vlaamse leeuwenvlaggen definitief geweerd: het Verdinaso gebruikte sindsdien consequent de Belgische en Nederlandse vlaggen, terwijl op hun meetings eveneens de vlaggen van alle Belgische en Nederlandse provincies en de volksliederen van beide landen gebruikt werden. Emiel Thiers (1890-1981), algemeen verslaggever, stelde op de 3de Landdag van het Verdinaso te Tielt in oktober 1934 dat het Verdinaso definitief en volledig gebroken had met de vermolmde Vlaamse Beweging: “Wij hebben ons verlost van het ‘flamingantisme’ en van het ‘hollandisme’; thans verlossen wij ons van de ‘separatistenmentaliteit’ (…)”.

Met de 3de Nieuwe Marsrichting in 1939 keerde Van Severen terug naar een etno-cultureel natiebegrip door de Franstaligen op basis van afstamming en bloed tot geromaniseerde Dietsers te verklaren. De historische gemeenschap der Nederlanden werd nu dus eveneens een volksgemeenschap, terwijl ook het Belgisch nationalisme aanvaard werd. De weg naar de Dietse natiestaat liep nu over een machtsovername in België, waarna samenwerking met Nederland en Luxemburg zou beoogd worden. Hiermee lag het Verdinaso aan de basis van de latere Benelux-gedachte.

Significant is voorts dat het Verdinaso zich nadrukkelijk “Noch linksch, noch rechtsch” noemde en als overtuigd antiparlementaire beweging nimmer deelnam aan verkiezingen. De Dinaso’s werden opgeroepen om blanco of ongeldig te stemmen. Desondanks was het Verdinaso toch een grote beweging: op de laatste grote meeting van het Verdinaso in het Antwerpse Sportpaleis in 1939 waren er 9.000 aanwezigen.

Na de dood van Joris Van Severen te Abbeville in mei 1940 kwam Emiel Thiers aan het hoofd van het Verdinaso. Samen met propagandaleider Paul Persyn (1912-1976) blies hij in de zomer van 1940 de beweging krachtig nieuw leven in, met onder meer een sterke aangroei van het ledenaantal en de opening van tientallen nieuwe Dinaso-huizen tot gevolg. In augustus 1940 sloot het Verdinaso een samenwerkingsakkoord met de Belgisch-nationalistische beweging Nationaal Legioen/Légion Nationale. Beide organisaties lieten de Militärverwaltung weten niet te zullen collaboreren zonder goedkeuring van de koning, van wie ze een initiatief verwachtten. In september 1940 volgde een akkoord met Rex-Vlaanderen.

De Duitsers dwongen in 1941 echter Verdinaso-Vlaanderen, Rex-Vlaanderen en het VNV te fuseren tot de Eenheidsbeweging-VNV. Tegelijk werden ook Verdinaso-Wallonië en Verdinaso-Nederland verplicht samen te gaan met respectievelijk Rex-Wallonië en de NSB. Het Nationaal Legioen/Légion Nationale weigerde te fuseren en werd volkomen uitgeschakeld: alle leiders werden naar Duitse concentratiekampen gedeporteerd.

Duitsland had immers als doel om de Lage Landen op termijn te annexeren (wat in juli 1944 ook gebeurde). Daarom onderdrukte de Duitse bezetter ieder Groot- en Heel-Nederlands streven en werd ook de Belgisch-Nederlandse grens gesloten: niemand kon zonder Duitse toestemming over de grens, waardoor bijgevolg geen contacten mogelijk waren over Belgisch-Nederlandse frontvorming. Verder wist Duitsland uiteraard al van vóór de Tweede Wereldoorlog dat het Verdinaso een onafhankelijke beweging was en dus niet te manipuleren viel zoals Rex en het VNV.

Het Verdinaso werd door de Duitse bezetter onder druk gezet: in januari-februari 1941 werd Hier Dinaso! (de periodiek van het Verdinaso) verboden, individuele Verdinaso-leiders zoals Jef François (1901-1996) en Pol Le Roy (1905-1983) werden bewerkt om voor een pro-Duitse koers te kiezen, de putsch van DMO-leider Jef François tegen Verdinaso-leider Thiers werd gesteund en uiteindelijk werd propagandaleider Persyn in april 1941 korte tijd opgesloten. Thiers begreep en trad af, waarop François hem opvolgde, doch slechts een klein deel der Dinaso’s wou François in de collaboratie volgen. François’ mini-Verdinaso werd tot vernederende onderhandelingen gedwongen met het VNV en uiteindelijk legde de Militärverwaltung op 5 mei 1941 een ‘akkoord’ over de Eenheidsbeweging-VNV op.

Door de gedwongen fusie viel het Verdinaso uiteen in 3 delen: primo een groep die actief in het verzet stapte tégen Duitsland, secundo een grote groep die zich neutraal opstelde en niet participeerde aan de oorlog en tertio een kleine groep die zich aansloot bij de collaborerende Eenheidsbeweging-VNV. Deze laatste strekking kreeg na de oorlog te maken met de repressie en epuratie, terwijl de 2 overige groepen ongehinderd nieuwe Dinaso-initiatieven ontplooiden.

Het kleine aantal collaborerende Dinaso’s – vooral uit de DMO en de jeugdorganisatie Jong Dinaso – kreeg de leiding over de SS-Vlaanderen. DMO’ers waren immers fysiek en psychisch gestaalde en ideologisch geschoolde leidersfiguren: zwakkelingen werden nadrukkelijk niet geduld in hun rangen. Ook de Jong Dinaso’s waren gevormd met het ideaalbeeld van de DMO’er voor ogen. En juist zo’n mannen had de SS nodig. Verder was het schenken van zo’n hoge posities aan ex-Dinaso’s uiteraard ook een middel om hen te overtuigen zich aan te sluiten bij de Eenheidsbeweging-VNV: het bewees dat ze geen tweederangsrol zouden moeten spelen.

Het VNV bleek dus voor de Duitsers ideologisch en organisatorisch te weinig onderbouwd. Die partij bestond immers uit meerdere, zéér verschillende strekkingen (zo ongeveer alles van links-flamingantisch tot extreem-rechts), zodat VNV-leider Staf De Clercq constant veel moeite had om deze kakofonie bijeen te houden. Het Verdinaso had daarentegen één – te nemen of te laten – koers gevoerd. Het VNV vertegenwoordigde duidelijk de kleinburgerlijke Vlaamse Beweging, terwijl het Verdinaso groots en Europees dacht.

De Eenheidsbeweging-VNV bleef officieel streven naar een zelfstandig Vlaanderen en naar een taalnationalistisch Groot-Nederland, maar zoals vermeld onderdrukten de Duitsers iedere Groot- (en ook Heel-)Nederlandse uiting snel. Na met veel naïef enthousiasme en zonder enige garanties in de collaboratie gestapt te zijn vielen in de loop der oorlog veel VNV’ers de schellen van de ogen: meer en meer leden werd het duidelijk dat ze gebruikt werden door de Duitse bezetter om voor hen het land te besturen, terwijl een Groot-Nederlandse staat er nooit zou komen. Tegen het voorjaar van 1944 had de Eenheidsbeweging-VNV dan ook al ca. 85% (!) van zijn leden verloren. Toen Duitsland in juli 1944 de Lage Landen annexeerde, stond het door de bevolking gehate VNV politiek schaakmat: wat moest het immers nog verdedigen gezien de annexatie – die het VNV altijd ontkend had – er nu wel gekomen was, waardoor de Dietse staat – die het VNV altijd beloofd had – er nu nooit meer zou komen?

Door de evoluties in Van Severens staatkundige gedachtegoed poogden zelfs de emotioneel anti-Belgische flaminganten hem na de oorlog te recupereren. Voor hen was er de herinnering aan de vroege Van Severen en bewees zijn executie het vermeende anti-Vlaamse karakter van de Belgische staat. Het verklaart waarom de flaminganten Van Severen – die hen nochtans verketterde als Hitlerknechten en separatisten – na de oorlog een plaats gaven in het flamingantische pantheon, ondanks sterk verzet van oud-Dinaso’s. Daarnaast was het flamingantisme ook niet vies van taalnationalistisch Groot-Nederlandisme, louter als middel tegen iedere poging tot verzoening met België. Er mocht alleen niet gepreciseerd worden wat Van Severen in werkelijkheid met het begrip ‘Dietsland’ bedoelde. Het verklaart alvast waarom zowat iedereen in de Vlaamse Beweging een volkomen verkeerd begrip heeft – zowel ideologisch als staatkundig – van Joris Van Severen en zijn beweging. Het Verdinaso van na de Nieuwe Marsrichting van 1934 is immers enkel en alleen de maatstaf voor de Belgischgezinde, Heel-Nederlandse en solidaristische beweging. De liberaal-conservatieve flaminganten vereenzelvigen zich dan ook onterecht met zijn historische erfenis.

De Belgischgezinde neo-Dinaso-beweging tijdens en na de Tweede Wereldoorlog

Onmiddellijk na de ondergang van het Verdinaso in het voorjaar van 1941 stichtten diverse ontevreden Dinaso’s het clandestiene Dietsch Eedverbond, dat ook een aantal misnoegde VNV’ers aantrok. Leden dienden de Dietse Eed, die stelde dat de Dietse gedachte onder alle omstandigheden moest primeren, af te leggen. Het Dietsch Eedverbond opereerde voornamelijk via persoonlijke informele contacten. De groepering bestond tot 1944 en oefende zware kritiek op het collaborerende VNV uit.

Daarnaast werd in 1942 het Heel-Nederlandse Dietsch Studenten Keurfront (DSK) gesticht, dat in 1943 zijn naam in Diets Solidaristisch Keurfront veranderde. Het DSK bestond vooral uit Gentse studenten. In Leuven was onder meer de latere CVP-Minister Frans Van Mechelen (1923-2000) lid. Daarnaast waren er ook nog contacten in Sint-Niklaas en Turnhout. Het DSK telde ca. 200 leden en werd geleid door onder meer Jozef Moorkens, Herman Todts (1921-1993) en Edmond De Clopper (1922-1998). Zij waren ideologisch sterk op het voormalige Verdinaso gericht en wezen de onvoorwaardelijke collaboratie af. Het VNV werd dan ook scherp gehekeld in DSK-pamfletten.

Todts vertelde later over het DSK: “Jonge mensen, overwegend studenten die er een zelfde mentale instelling op nahielden, vonden elkaar in die dagen onder de verzamelnaam Diets Studenten Keurfront. Een jaar later Diets Solidaristisch Keurfront. De kwalificatie ‘Diets’ wees op een streven om de historische Zeventien Provincies van weleer tot één staat te herenigen; de kwalificatie ‘solidaristisch’ beklemtoonde inzet van alle leden van onze samenleving in ons verzet tegen de ons opgedrongen ideeën; terwijl de kwalificatie ‘keurfront’ het geloof in de dominantie van de elite benadrukte.”

Het DSK vergaderde van 1942 tot september 1944 regelmatig in het ouderlijk huis van Edmond De Clopper aan de Vrijdagmarkt in Gent. Na de oorlog werd de studentenorganisatie Solidaristische Beweging (cfr. infra) gesticht door DSK’ers.

Nog tijdens de oorlog richtte E.H. Bonifaas Luykx De Gemeenschap op, dat onmiskenbaar een neo-Dinaso-jongerengroep was en waar relatief veel oud-Dinaso’s bij betrokken waren. Hierover zijn echter weinig gegevens bekend. Daarnaast was er tijdens de oorlog ook nog de beweging rond de Henegouwse Dinaso Louis Gueuning (cfr. infra).

Oud-Dinaso’s die na de oorlog weer politiek actief werden, verspreidden zich over het hele katholiek-conservatieve kamp. Zo vinden we in de christendemocratische zuil bijvoorbeeld Willem Melis (eerste hoofdredacteur van de naoorlogse De Standaard in 1947), Luc Delafortrie (redacteur bij De Standaard in 1954-1978), Rafaël Renard (adjunct-kabinetschef van minister Arthur Gilson (1961-1965) en voorzitter van de Vaste Commissie voor Taaltoezicht (1964-1976)), Jef Van Bilsen (Secretaris-Generaal en later Commissaris van de Koning voor Ontwikkelingssamenwerking in de jaren 1960 en regeringsdeskundige in de jaren 1970) en Frantz Van Dorpe (CVP-burgemeester van Sint-Niklaas in 1965-1976 en VEV-voorzitter vanaf 1959). Allemaal namen uit de strekking die het Verdinaso buiten de collaboratie wilde houden en na het mislukken van dat opzet inactief werd of in het verzet ging.

Daarnaast waren er na de oorlog tal van groepen die zich tot ideologische erfgenaam van het Verdinaso verklaarden en uiteraard afkerig tot vijandig stonden tegenover de Vlaamse Beweging. De neo-Dinaso-visie op de Vlaamse Beweging werd vertolkt door Herman Todts in het artikel ‘Ik klaag aan. Aan mijn vrienden van de Vlaamse Beweging’ in De Uitweg van 31 mei 1952: oorspronkelijk was de Vlaamse Beweging een positieve kracht door haar Nederlandse oriëntatie, die ze op cultureel vlak kreeg van Jan-Frans Willems en die op politiek vlak werd voortgezet door Joris Van Severen; nu was het echter een “lamlendige pruikenbeweging” geworden, die ver was afgedwaald.

Eén der belangrijkste figuren hierbij was Louis Gueuning, voormalig Verdinaso-leider der Romaanse gouwen (cfr. infra). Zijn neo-Dinaso-strekking verdedigde hetzelfde staatkundige en maatschappelijke project als het Verdinaso en keurde de collaboratie af. De repressie en epuratie werden positief gewaardeerd, hoewel men wel oog had voor de vele onschuldigen die er door getroffen werden.

De oud- en neo-Dinaso’s bleven overtuigd van de Dietse Rijksgedachte en bleven steeds het herstel der historische Nederlanden en der vroegere provinciën nastreven. Hun staatkundig project wou net zoals Van Severens Nieuwe Marsrichting in 1934 de Belgische kerngebieden – Belgisch-Vlaanderen en Belgisch-Brabant – de staatsmacht in handen geven. De Belgischgezinde neo-Dinaso’s vertoonden geen enkele affiniteit met het flamingantisme en volgden Van Severens Belgisch-nationalistische koers. Hun aanhang bestond uit radicaal-conservatieve katholieken en Belgisch-nationalisten, zoals Van Severens goede vriend en PSC’er baron Pierre Nothomb (1887-1966).

Onmiddellijk na de oorlog hadden flamingantisme en federalisme bij de publieke opinie van Nederlandstalig België volledig afgedaan, zelfs al vóór de Duitse aftocht in september 1944. Zelfs voor de flaminganten – met uitzondering van een kleine harde kern – werd België opnieuw het onbetwiste vaderland. Pas in de jaren 1960 zou een deel der flaminganten weer kritischer worden over België.

Tot diep in de jaren 1950 was de Heel-Nederlandse beweging heel sterk. De neo-Dinaso’s speelden daarin een vooraanstaande rol doordat velen onder hen niet of nauwelijks met de repressie hadden te maken gehad en dus politiek actief mochten zijn. Bovendien hadden zij na de oorlog, toen openlijke kritiek op de Belgische staatsstructuur gewoonweg ondenkbaar was, het voordeel dat hun staatkundig programma niet op de vernietiging van België gericht was. Daarnaast beschikten de neo-Dinaso’s ook nog eens over erkende verzetslui.

Conform de leer van het Verdinaso waren de neo-Dinaso’s meestal afkerig van partijpolitiek. Zij organiseerden zich voornamelijk als een kern van ideologisch sterk geschoolde leden die een voorbeeldfunctie moest vervullen. Geen enkele groep slaagde er door de stabiliteit der naoorlogse parlementaire democratie echter in om nog maar een fractie van het succes van het Verdinaso te bereiken. Misschien verklaart dit waarom veel neo-Dinaso’s de antipartijpolitieke houding niet consequent volhielden. Heel wat oud-Dinaso’s kwamen immers terecht in de CVP en aanvankelijk zelfs even in de reorganisatie der flamingantische partijpolitiek.

De neo-Dinaso-groepen bereikten door een eindeloze reeks ruzies en afscheuringen zelden een betekenisvolle eenheid. Een logische ontmoetingsmogelijkheid waren uiteraard de jaarlijkse Van Severen-herdenkingen. In februari 1956 schreef de neo-Dinaso Staf Vermeire (1926-1987) aan de gewezen DMO-leider en collaborateur Jef François dat “de sterke tegenstellingen” tussen de oud-Dinaso’s enkel nog konden overwonnen worden op een ééndaagse herdenking. Er bestonden bijgevolg tientallen naoorlogse neo-Dinaso-periodieken. Vrijwel zonder uitzondering werden deze geïllustreerd met hagiografische beschrijvingen, teksten en citaten van Van Severen. Dit toont aan hoe sterk de Leider geïdealiseerd werd door zijn naoorlogse volgelingen. Vanaf de jaren 1960 raakte een herstel der Bourgondische Nederlanden echter gemarginaliseerd door het opkomende taalfederalisme dat eerst de Vlaamse en Waalse Bewegingen en uiteindelijk de media en het politieke establishment veroverde.

De neo-Dinaso-beweging van Louis Gueuning

De Henegouwer Louis Gueuning (1898-1971), leraar aan het atheneum van Soignies, was aanvankelijk actief in het Waalse regionalisme en sloot zich in 1931 aan bij de groepering La Renaissance Wallonne. Zijn waardering voor het Portugese staatshoofd Antonio Salazar en voor gewestelijke geschiedenis en verscheidenheid, evenals een afkeer voor de parlementaire democratie brachten hem en enkele Waalse vrienden in maart 1939 bij het Verdinaso. Met Joris Van Severen ontwikkelde Gueuning al snel een hechte vriendschap en intense correspondentie, hoewel hij geen voorstander was van het militarisme van het Verdinaso. Op 4 mei 1940 werd hij door Van Severen aangeduid als verantwoordelijke voor de Romaanse gouwen.

Na de executie van Van Severen nam de én anti-Duitse én anti-Britse Gueuning tijdens de oorlog een attentistische houding aan: hij voerde een onafhankelijke politieke koers en benadrukte de zelfstandigheid der Lage Landen. Met een tiental Dinaso’s richtte Gueuning de Joris Van Severen-Orde op die onder meer jaarlijks in mei een beperkte, clandestiene herdenking van Van Severen organiseerde en verder Van Severens denkwerk consolideerde. In tegenstelling tot VNV en Rex collaboreerde Gueuning dus niet met de Duitse bezetter én wees hij eveneens samenwerking met de geallieerden af. Hij werd dan ook vervolgd door zowel de Duitse Gestapo tijdens de oorlog als door het communistisch verzet tijdens de repressie. Gueunings neutrale koers bleek echter zijn redding en hij doorstond beide vervolgingen zonder blijvende gevolgen. Wel werd zijn huis geplunderd tijdens de repressie en hij verloor zijn job. In 1950 stichtte Gueuning het Albrecht-en-Isabellacollege in Sint-Pietersleeuw. Dit was een elitaire, Franstalige privé-school met hem aan het hoofd.

Ook na de Tweede Wereldoorlog handhaafde de Gueuning-groep de ideologie van Joris Van Severen en het Verdinaso. Volgens Le Peuple (dd. 15 februari 1946) werden er tijdens de verkiezingscampagne van 1946 al pamfletten verspreid met een oproep om te stemmen óf blanco óf voor kandidaten die voor “le rapprochement des Pays-Bas tout entiers” stonden. Voorts verschenen er diverse periodieken. Zo steunde in 1945-1949 L’Actualité Politique – waaraan vooral André Belmans (1915-2008) meewerkte – Leopold III, terwijl het blad ook streed tegen de partijpolitiek. Vanaf maart 1951 verscheen De Uitweg, dat eerst de heruitgave van Hier Dinaso! (cfr. infra) overnam en daarna door de fusie met Le Cri du Peuple in november 1951 een Franstalige tegenhanger kreeg. Tot eind 1953 verscheen De Uitweg als weekblad, in 1954 werd het een maandblad en later verscheen het door financiële problemen onregelmatig. Uiteindelijk werd het opgevolgd door het blad Politiek nu (1969-1971).

Gueuning bezorgde de Leider in 1951 tevens een grafmonument te Abbeville, waarop Van Severen tot ‘Pater Patriae’ en ‘Novi Belgii Conditor’ verklaard werd. Hij recruteerde zijn aanhangers vooral in Nederlandstalig België en onder tweetalige Brabanders. Verder had hij wisselende contacten met diverse Belgischgezinde Derde Weg-groepen. Voor de door Gueuning samengeroepen ‘Staten-Generaal van Verzet tegen het Regime’ op 13 en 14 september 1952 in de Antwerpse zaal Gruter daagden ca. 300 mensen op.

Ideologisch volgde Gueuning de lijn van Van Severen in diens laatste fase. Belangrijkste doel was het herstel der historische Lage Landen in hun gewestelijke verscheidenheid als een organische natie die de kern moest worden van een nieuw Europa. Grote vijand was “de Vreemde” of “l’Étranger”: de buurlanden hadden er steeds alles aan gedaan om de Nederlanden te verdelen en te beheersen. Groot-Brittannië werd door Gueuning bijzonder geviseerd: ‘Albion’ was de nieuwe bezetter en het door de oorlogsregering van Londen beheerste regime was de nieuwe collaborateur. De flamingantische en wallingantische federalisten dienden bewust of onbewust het belang van “de Vreemde” doordat ze na 1830 nog eens de natie wilden opdelen.

Gueuning publiceerde veel over de nagedachtenis en ideologie van Van Severen. Ter legitimering der Nederlandse natie publiceerde hij over de natuurlijke en historische eenheid en zending ervan. Gueuning was een Heel-Nederlander die op basis van historische en geopolitieke argumenten geloofde in het ideaal der 17 Provinciën. Hij wees nationalisme consequent af aangezien dit product van de 19de eeuwse Romantiek Europa evenveel schade had toegebracht als het liberalisme en marxisme. Hierbij verwees hij naar “de verwoesting” in de Nederlanden door het taal-, sociaal en economisch nationalisme. Zijn duidelijke afwijzing van flamingantisme en wallingantisme betekende dat taal voor Gueuning geen enkele waarde had als afbakeningscriterium voor een natie.

Gueunings denken werd gedomineerd door personalisme en roeping. Primo, personalisme betekent dat de mens zich zo volledig mogelijk moet kunnen ontplooien. Naast zijn Heel-Nederlandse motieven verklaart dit mee waarom Gueuning weigerde te collaboreren met nazi-Duitsland, dat een volledig andere visie op de mens had. Orde was voor hem een noodzakelijke menselijke zelfdiscipline om zich persoonlijk te kunnen ontwikkelen. Secundo, het begrip roeping houdt in dat iedere mens een unieke roeping heeft in zijn leven en in de maatschappij. Door deze roeping zo goed mogelijk te vervullen geeft de mens zin aan zijn handelen en leven. Een maatschappij dient op ieder niveau de roeping van ieder individu te ondersteunen, daar zij het resultaat is van de vervulde roepingen van zichzelf ontplooiende individuen. Vrijheid was hierbij voor Gueuning geen libertijns doel op zich, maar een middel in de ontplooiing van de mens, evenals het begrip orde.

Inzake de sociale ordening hernam Gueuning niet expliciet de solidaristische leer. Hij gebruikte de term solidarisme niet en pleitte ook nauwelijks voor een corporatistische staat. Nochtans zat hij wel op die lijn: het volk diende in de staat vertegenwoordigd te worden door zijn elites: “alle beroepsverenigingen, alle gewestelijke groeperingen, alle levensbeschouwingen die de grondslagen van de nationale gemeenschap niet aantasten, hebben recht vertegenwoordigd te worden”.

Verder promootte Gueuning een autoritair regime rond de koning die ten volle zijn grondwettelijke voorrechten moest kunnen uitoefenen bij de samenstelling van een onafhankelijke regering. Naast dit klassieke discours der Belgischgezinde Derde Weg-beweging diende vooral het partijenstelsel uitgeschakeld te worden. Dit mocht met alle middelen worden bestreden, zelfs onwettige. Deelname aan de partijpolitieke strijd werd zinloos geacht: bij verkiezingen werden de aanhangers opgeroepen om blanco te stemmen.