The Pre-Death Thoughts of Faust

(1922 - #59)

N. A. BERDYAEV (BERDIAEV)

The fate of Faust -- is the fate of European culture. The soul of Faust -- is the soul of Western Europe. This soul was full of stormy, of endless strivings. In it there was an exceptional dynamism, unknown to the soul of antiquity, to the Greek soul. In its youth, in the era of the Renaissance, and still earlier, in the Renaissance of the Middle Ages, the soul of Faust sought passionately for truth, they fell in love with Gretchen and for the realisation of his endless human aspirations it entered into a pact with Mephistopheles, with the evil spirit of the earth. And the Faustian soul was gradually corroded by the Mephistophelean principle. Its powers began to wane. What ended the endless strivings of the Faustian soul, to what did they lead? The Faustian soul led to the draining of swamps, to the engineering art, to a material arranging of the earth and to a material mastery over the world. Thus we find spoken towards the conclusion of the second part of Faust:

Ein Sumpf zieht am Gebirge hin,

Verpestet alles schon Errungene;

Den faulen Pfuhl auch abzuziehn,

Das letzte waer das Hoechsterrungene,

Eroeffn ich Raeume vielen Millionen,

Nicht sicher zwar, doch taetig-frei zu wohnen.

Nigh the mountain a swamp doth stretch,

Pollutes there every advancement;

To drain off the foul pool,

Would be the utmost highest achievement,

I'd open up space for many a million,

Not indeed secure, but active-free to be.

And thus do end during the XIX-XX Centuries the searchings of the man of modern history. With genius Goethe foresaw this. But the final word for him belongs with the mystic chorus:

Alles Vergaengliche

Ist nur ein Gleichnis;

Das Unzulaengliche,

Hier wird's Ereignis;

Das Unbeschreibliche,

Hier ist's getan;

Das Ewig-Weibliche

Zieht uns hinan.

All the Transitory

Is but a Symbol Image

The Insufficient

Here doth transpire;

The Ineffable

Here doth act;

The Eternal-Feminine

Upward doth draw us.

And draining the swamp is but a symbol of the spiritual path of Faust, merely a sign of spiritual activity. Upon his path, Faust passes from a religious culture over to an irreligious civilisation. And in this irreligious civilisation the creative energy of Faust becomes drained, his endless aspirations die. Goethe gave expression to the soul of Western European culture and its fate. Spengler, in his challenging book, "Der Untergang des Abendslandes" ["The Decline of the West"], announces the end of European culture, its ultimate transition over into civilisation, which is the beginning of the death-process. "Civilisation -- is the irreversible fate of a culture". The book of Spengler bears within it an enormous symptomatic significance. It conveys the feeling of crisis, of sudden impending change, that of the end of an entire historical era. It speaks about the great sorry affair of things in Western Europe. We, as Russians, have been split off from Western Europe already for many a long year, from its spiritual life. And since our access to it has been blocked, it has seemed to us to be more fortunate, more orderly, more happy, than it is in actuality. Even prior to the World War, I very acutely sensed the crisis of European culture, the impending end of an entire world era, and I expressed this in my book, "The Meaning of Creativity". During wartime also I wrote an article, "The End of Europe", in which I expressed the thought, that the twilight period of Europe has begun, that Europe is at an end as a monopolist of culture, that the emergence of culture out beyond the bounds of Europe has been inevitable, for other continents and other races. Moreover, two years back I wrote an etude, "The End of the Renaissance", and a book, "The Meaning of History: Attempt at a Philosophy of Human Fate", in both which I definitely expressed the idea, that we are experiencing the end of modern history, that we are living out the final remnants of the Renaissance period of history, that the culture of old Europe has tended towards deterioration. And therefore I read the book of Spengler with an especial tremulation. In our era, with its historical disintegration, thought is focused upon the problems of the philosophy of history. It was the same in the epoch, when Bl. Augustine conceived of his first rendering of a Christian philosophy of history. It is possible to foresee, that philosophic thought henceforth will be concerned not so much with problems of gnosseology, as rather by problems of the philosophy of history. In the "Bhagavad Gita" revelations occur during a time of warfare. During a time of war there can be resolved ultimate problems about God and the meaning of life, but it is difficult to get concerned over analytic gnosseology. And in out time is at work the thinking during a time of war. We live in an epoch inwardly akin to the Hellenistic epoch, the epoch of the collapse of the ancient world. The book of Spengler -- is a remarkable book, in places almost of genius, it stimulates and makes for thought. But it cannot be too much a surprise for those Russian people, who long since already have sensed the crisis, about which Spengler speaks.

* * *

Spengler can convey the impression of being an extreme relativist and sceptic. Even mathematics for him is something relative. There exists the ancient Apollonian mathematics, -- a finite mathematics, and there exists the European Faustian mathematics, -- an infinite mathematics. Science is not unconditional, not absolute, but is rather the expression of the souls of various cultures, of various races. But still, in essence, it is impossible to classify Spengler under any sort of current. Academic philosophy is quite alien to him, and he holds it in contempt. He is first of all his own unique individualist. And in this he is akin to the Goethean spirit of contemplation. Goethe intuitively contemplated the primal phenomena of nature. Spengler intuitively contemplates the history of the primal phenomena of culture. He, just also as with Goethe, is a symbolist as regards world-concept. He refuses to think employing abstract concepts, he does not believe in the fruitfulness of such thinking. All abstract metaphysics is foreign to him. From the morbid methodologism and gnosseologism, in which German great thought emerged, from the sick and futile reflection, Spengler has instead turned away towards living intuition. He casts himself into the dark ocean of the historical existence of peoples and penetrates into the soul of races and cultures, into the styles of the various epochs. He makes a break with the epoch of gnosseologism in the philosophy of thought, but he does not pass over to ontologism, he does not construct any sort of ontology and does not believe in the possibility of ontology. He knows only of being, as manifest in cultures, as reflected in cultures. The primal grounds of being and the meaning of existence remain for him hidden. The morphology of history for him -- is the solely possible philosophy. With him there is not even a philosophy of history, exclusively it is rather -- a morphology of history. All the truths, the truths of science, of philosophy, religion, -- are for Spengler merely the truths of culture, of cultural types, of cultured souls. The truths of mathematics -- are the symbols of various styles of cultured souls. Such an attitude towards cognition and being is characteristic to a man of a late and waning culture. The soul of a man set within an epoch of cultural decline tends to ponder over the fate of cultures, over the historical fate of mankind. It has always been so. Such a soul has no interest either in the abstract knowledge of nature, nor in the abstract knowledge of the essence and meaning of being. Of interest to it is the culture itself, and everything -- is merely reflected in the culture. It is struck by the dying off of once flourishing cultures. It is wounded by the inevitability of fate. Spengler is very capricious, he does not consider himself bound by anything in general obligatory. He is, first of all -- a paradoxicalist. For him, just as for Nietzsche, paradox is a means of cognition. In the book of Spengler there is a sort of affinity with the book of the youthful genius [Otto] Weininger, "Sex and Character", and despite all the different themes and spiritual outlook, the book of Spengler -- is just as remarkable a phenomenon in the spiritual culture of Germany, as is the book of Weininger. In breadth of intent, in scope, in its unique intuitive insights into the history of cultures, the book of Spengler can take its place alongside the remarkable book of [Houston Stewart] Chamberlain ("Die Grundlagen des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts" ["The Foundations of the Nineteen-Hundreds"]). After Nietzsche -- comes Weininger, Chamberlain and Spengler -- the sole genuinely original and remarkable figures in German spiritual culture. Just like Schopenhauer, Spengler has contempt for professors of philosophy. He offers a very arbitrary list of writers and thinkers, and in his opinion of the remarkable books, esteemed by him. These people are of a quite various a spirit. But they all bear some relationship to the principle of the will to live and the will to power, all have bearing on the crisis of culture. These are -- Schopenhauer, Proudhon, Marx, R. Wagner, Duhring, Ibsen, Nietzsche, Strindberg, Weininger. Is Spengler a pessimist? For many, his book has to produce the impression of a very boundless pessimism. But this is not a metaphysical pessimism. Spengler does not desire the quenching of the will to live. On the contrary, he desires the affirmation of the will to live and the will to power. In this he is closer to Nietzsche, than to Schopenhauer. All cultures are doomed to a withering away and death. Our European culture is also doomed. But it is necessary to accept fate, not oppose it, and to live it out to the end, and to the end manifesting the will to power. With Spengler there is the amor fati. The pessimism of Spengler, if such a term be properly applicable to him, is a pessimism culturo-historical, and is neither a pessimism individually-metaphysical nor individually-ethical. He -- is a pessimist on civilisation. He denies the idea of progress, and he returns to the teaching about cyclical returns. But with him there is no pessimistic balance of suffering and pleasure, of a pessimistic understanding of the very essence of life. He admits of an inexhaustible creative wellspring of life, lodged within the primal impulse, begetting culture all ever new and anew. He is fond of this will to cultural flourishing. And he perceives the death of a culture as a law of life, as an inevitable moment within the vital fate of a culture itself. Surprisingly strong with Spengler is a correlation of phenomena in various spheres of a culture and the discerning from them of an unique symbol, such as signifies that selfsame culture, that selfsame cultural style. He transfers concepts from mathematics and physics over into painting and music, from art into politics, from politics into religion. Thus, he speaks about an Apollonian and a Faustian mathematics. He discerns one and the same primary phenomenon within various epochs, within various cultures. And he regards it possible to admit of one and the same sort of such phenomena, as Buddhism, Stoicism and Socialism, belonging to various epochs and cultures. His most remarkable thoughts are about art and about mathematics and physics. And with him there are truly intuitions of genius.

Spengler -- is of an areligious nature. In this is his tragedy. With him there is as it were an atrophied religious sense. Whereas both Weininger and Chamberlain -- are of a religious nature, Spengler -- is areligious. He is not only himself non-religious, but he also does not understand the religious life of mankind. Yet he examined the role of Christianity within the fate of European culture. This -- is the most striking side of his book. In this is its spiritual deformity, almost its monstrous defect. It is not necessary to be a Christian, in order to understand the significance of Christianity within the history of European culture. The pathos of objectivity ought to be brought to bear on this. But Spengler does not sense himself under the compulsion of any such objectivity. He does not ponder on Christianity within history, he does not see a religious meaning. He knows, that culture is religious by its nature and by this it is distinct from civilisation, which is irreligious. But he has been able to express very noble thoughts, such as only can be expressed by a non-believing soul in our epoch. Behind his civilised self-feeling and self-awareness can be sense the imprint of a culture, which has lost its faith and is tending towards decline.

* * *

Spengler understands and senses the world foremost of all as history. This he regards as the modern perception of the world. It is only to such an attitude towards the world that there belongs a future. Dynamism is characteristic to our times. And only a perceiving the world as history is a dynamic perception. The world as nature is static. Spengler contrasts nature and history, as two methods of viewing the world. Nature is expanse. History is time. The world presents itself to us as nature, when we view it from the perspective of causality, and it presents itself to us as history, when we view it from the perspective of fate. That history is a matter of fate, is all very well and good with Spengler. Fate cannot be conceived of by means of a causal explanation. Only the perspective of fate gives us a grasp upon the concrete. Spengler's assertion is quite correct, that for ancient man there was no history. The Greek perceived the world as static, for him it was from nature, from the cosmos, and not from history. He did not know historical remoteness. Spengler's thoughts on antiquity are very insightful. And it mustneeds be admitted, that Greek thought did not know of a philosophy of history. It was not a matter of either Plato, or of Aristotle. The point of view of a philosophy of history is contrary to the aesthetic ponderings of the Hellene. The world for him was a completed cosmos. Hellenic thought created the Hellenic metaphysics, so inconducive for conceiving the world as an historical process. Spengler senses himself as an European man with a Faustian soul, with its infinite aspirations. He not only sets himself distinct from ancient man, he moreover asserts, that the ancient soul for him is inconceivable, is impenetrable. This however does not prevent him from drawing upon its understanding and insights. But does history exist for Spengler himself, is he one for whom there is a world, as history, and not as nature? I think, that for Spengler history does not exist and for him a philosophy of history is impossible. Not by chance did he call his book a morphology of world history. The morphological perspective derives from nature-knowledge. Historical fate, the fate of culture exists for Spengler only in that sense, that fate exists for a flower. The historical fate of mankind does not exist. There does not exist a single mankind, a single subject of history. Christianity was the first to have rendered possible a philosophy of history, in that it revealed the existence of a single mankind with a single historical fate, having its own beginning and end. Thus first for the Christian consciousness is revealed the tragedy of world history, the fate of mankind. Spengler however turns back to the pagan particularism. For him there is no mankind, no worldwide history. Cultures, races -- are isolated monads with an isolated fate. For him the varied types of culture experience a cyclical turning of their own fate. He returns to the Hellenic perspective, which was surpassed by the Christian consciousness. With Spengler the Baptismal water as it were was missing. He abjures his own Christian blood. And for him, just as for the Hellene, there does not exist the perspective of an historical remoteness. The historically remote distance exists only in this instance, if there exists an historical fate of mankind, a worldwide history, if each type of culture is but a moment of a worldwide fate.

The Faustian soul with its endless aspirations, with the distance opening up before it, is the soul of the Christian period of history. This Christianity shatters the boundaries of the ancient world, with its delimited and narrowed horizons. After the appearance of Christianity in the world, an infinity opened up. Christianity rendered possible the Faustian mathematics, the mathematics of the endless. Of this Spengler is not at all aware. He does not posit the appearance of the Faustian soul in any sort of connection with Christianity. He has made an examination of the significance of Christianity for European culture, for the fate of European culture. This fate however -- is a Christian fate. He wants to push Christianity back exclusively to the sense of a magical soul, to a type of Hebrew and Arabic culture, to the east. And he thus dooms himself to a lack of understanding of the meaning of European culture. For Spengler generally there does not exist a meaning to history. The meaning of history also cannot exist amidst such a denial of the subject of the historical process. The cyclical turnings of the various types of culture, lacking connections between them of a single fate, is totally meaningless. Moreover, the denial of a meaning to history makes impossible a philosophy of history. There remains but the morphology of history. But for the morphology of history there is merely the manifestation of nature, in it there is no unique historical process, no fate, as a manifestation of meaning. In Spengler the Faustian soul ultimately loses its connection with Christianity, which gave it birth, and in the hour of the waning of the Faustian culture it attempts to return to the ancient sense of life, tacking on it also the theme of history. In Spengler, despite his distasteful civilisation pathos, there is sensed also the exhaustion of a trans-cultural man. This weariness of a man of an era of decline quenches any sense of the meaning of history and its connections to historical fates. There remains only the possibility of an intuitive-aesthetic insight into the types and styles of the souls of cultures. Faust does not bear up under a time of historical fate, he does not want to experience it to the final end. He, weary and exhausted by the modern history, agrees it the better to die, having experienced a short moment of civilisation, set at the summit of culture. He is captivated by the thought, that he is to be given this final mitigation and consolation of death. But there is no death. Fate continues on even beyond this side of what the Faustian soul had acknowledged as the sole life. And the burden of this fate has to be carried across into the remote eternity. For Spengler's Faustian soul the remote eternity is hidden, the historical fate beyond the bounds of this life, of this culture and civilisation; to the end of his days he wants to restrict himself to the cycle of a dying civilisation. He foresees the rise of new cultures, which likewise will pass over into a civilisation and die. But these new souls of cultures are foreign to him and he regards them for himself as impenetrable. These new cultures which, perhaps, will arise in the East, will not have any sort of inward connection with the dying European culture. Faust loses the perspective of history, of historical fate. Culture for him -- is merely a springing forth, a blossoming and fading flower. Faust ceases to understand the meaning and the bond of fate, since for him the light of the Logos has grown dim, there has grown dark the sun of Christianity. And the appearance of Spengler, a man exceptionally gifted, at times close to genius in certain of his intuitions, is very remarkable for the fate of European culture, for the fate of the Faustian soul. There is nowhere further to go. After Spengler -- there is already the plunge into the abyss. With Spengler there is a great intuitive gift, but this -- is but the giftedness of a blindman. As a blindman, no longer still seeing the light, he throws himself off into the murky ocean of culturo-historical being. With Hegel there was still a Christian philosophy of history, in its sort no less Christian, than the philosophy of history of Bl. Augustine. It knows of an unified subject of history and meaning to history. It shines through everything with the rays of the Christian sun. With Spengler there are no longer these rays. Hegel belongs to a culture, possessing a religious basis; Spengler senses himself as already having passed over into a civilisation, bereft of religious basis. One might moreover still note, that the point of view of Spengler unexpectedly reminds one of the perspective of N. Danilevsky, as developed in his book, "Russia and Europe". The culturo-historical types of Danilevsky are very similar to the souls of the cultures of Spengler, but with this difference, that Danilevsky is quite lacking in the enormous intuitive gift of Spengler. Vl. Solov'ev criticised N. Danilevsky from the Christian point of view. For Spengler the fate of the history of the world remains unsolved, since for him history is but an aspect of nature, a phenomenon of nature, and it is not in that nature -- is an aspect of history, as it is for historical metaphysics.

* * *

Every culture inevitably passes over into civilisation. Civilisation is the fate, the doomed lot of culture. Civilisation however ends up by death, it is already the beginning of death, the exhaustion of the creative powers of a culture. This -- is a central thought of Spengler's book. "We are civilised people, and not people of the Gothic or Rococco". What differentiates civilisation from culture? A culture -- is religious as to its basis, civilisation -- is irreligious. For Spengler -- this is a fundamental distinction. And he regards himself as a man of civilisation, since he is irreligious. A culture derives from a cult, it is bound up with a cult of ancestors, it is impossible without sacred traditions. Civilisation is the will to worldwide might, to an ordering of the surface of the earth. A culture -- is national. Civilisation -- is international. Civilisation is the worldwide city. Imperialism and socialism alike -- are civilisation, and not culture. Philosophy and art exist only in a culture, in a civilisation they are impossible and unnecessary. Possible and necessary within civilisation is only the engineering art. And Spengler gives the appearances, that he understands the pathos of the engineering art. Culture -- is organic. Civilisation -- is mechanical. Culture is grounded upon inequality, upon qualities. Civilisation in contrast is pervaded by the aspiration for equality, it seeks to be based upon quantities. Culture -- is something aristocratic. Civilisation -- is something democratic. The distinction of culture in contrast to civilisation is of something extraordinarily fruitful. With Spengler there is a very acute sense of an inexorable process of the victory of civilisation over culture. The decline of Western Europe for him is first of all the decline of the old European culture, the exhaustion within it of the creative powers, the end of art, of philosophy, of religion. Civilisation has still not reached its finish. Civilisation will still celebrate its victory. But after civilisation will come the onset of death for the Western European cultural race. And after this, culture can blossom forth only in other races, only in other souls.

These thoughts are expressed by Spengler with an astounding brilliance. But are these thoughts something new? For us, as Russians, it is impossible to be taken aback by these thoughts. We long since already know of the difference of culture from civilisation. All the Russian religious thinkers have asserted this difference. they all sensed a certain sacred terror at the perishing of culture and the ensuing triumph of civilisation. The struggle against the spirit of philistinism, which so wounded Hertsen and K. Leont'ev, people of quite varied tendencies and outlook, was grounded upon this motif. Civilisation by its nature is pervaded by a spiritual philistinism, by a spiritual bourgeoisness. Capitalism and socialism entirely alike are infected by this spirit. Beneathe the hostility towards the West of many a Russian writer and thinker lies concealed not hostility towards Western culture, but rather hostility towards Western civilisation. Konstantin Leont'ev, one of the most insightful of Russian thinkers, loved the great culture of the West, he loved the colourful culture of the Renaissance, he loved the Catholic great culture of the Middle Ages, he loved the spirit of chivalry, he loved the genius of the West, he loved the mighty manifestation of the sense of person within this great cultural world. But he abominated the civilisation of the West, the fruition of the liberal-egalitarian process, the extinguishing of spirit and the death of creativity within civilisation. He comprehended already the law of the transition of culture over into civilisation. For him this was an inexorable law within the life of societies. Culture for him corresponded to that period in the developing of societies, which he termed as the period of the "blossoming of complexity", civilisation however corresponded to a period of "simplistic confusion". The problem of Spengler was quite clearly posited by K. Leont'ev. He likewise denied progress, he confessed a theory of cycles, he asserted, that after the complex blossoming forth of culture there ensues decline, decay, death. The process of "liberal-egalitarian" civilisation is the onset of death, of disintegration. For Western European culture he regarded this death as irreversible. He saw the perishing of the flourishing culture in the West. But he wanted to believe, that a flourishing culture was still possible in the East, in Russia. Though towards the end of his life he lost also this faith, he saw, that also in Russia civilisation was triumphing, that in Russia matters were going towards a "simplistic confusion". And then he came to be imbued with a dark apocalyptic outlook. So also Vl. Solov'ev towards the end lost faith of a possibility within the world of a religious culture and he had an anguished sense of the onset of the kingdom of the Anti-Christ. Culture is possessed of a religious basis, there is in it a sacred symbolism. Civilisation however is of the kingdom of this world. It is the triumph of the "bourgeois" spirit, of a spiritual "bourgeoisness". And it makes totally no difference, whether it be a civilisation capitalistic or socialistic, it is alike -- a godless philistine civilisation. Indeed even Dostoevsky was not an enemy of Western culture. Remarkable in this regard are the thoughts of Versilov in "The Adolescent". "They are not free, -- says Versilov, -- but we are free". "Only I alone in Europe with my Russian melancholy then was free... To the Russian, Europe is precious the same, as is Russia: each stone in it is dear and precious. Europe has been our fatherland the same, as also is Russia... O, to the Russian, dear are these old foreign stones, these miracles of God's old world, these bits of sacred wonders: and to us this is even more dear, than it is to them themselves. They have now other thoughts and other feelings, and they have ceased to appreciate the old stones". Dostoevsky loved these "old stones" of Western Europe, "these miracles of God's old world". But he, just as with K. Leont'ev, denounces the people of the West for this, that they have ceased to revere their "old stones", they have forsaken their own great culture and have surrendered themselves completely to the spirit of civilisation. Dostoevsky loathed not the West, not the Western culture, but rather the irreligious, the godless civilisation of the West. Russian Easternism, Russian Slavophilism was merely a veiled struggle of the spirit of a religious culture against the spirit of an irreligious civilisation. The struggle of these two spirits, of these two types, is innate to Russia itself. This is not a struggle of East and West, of Russia and Europe. And many Western people too have felt anguish, almost to the point of agony, at the triumph of the irreligious and monstrous civilisation over a great and sacred culture. Suchlike have been the romantics of the West. Suchlike were the French Catholics and symbolists -- Barbey d'Aurevilly, [Paul] Verlaine, Villiers de L'Isle-Adam, Huysmans, Leon Bloy. Suchlike was Nietzsche, with his anguish over the tragic Dionysian culture. Not only remarkable Russian people, but also the most refined and perceptive Western people with anguish felt, that the great and holy culture of the west was perishing, that it was dying, that coming to it was a civilisation alien to it, a worldwide city, irreligious and international, that a new sort of man was coming, a parvenue, obsessed with a will to world power and taking possession of all the earth. In this victorious march of civilisation was dying the soul of Europe, the soul of European culture.

The originality of Spengler was not in the positing of this theme. This theme had already been posited with an extraordinary alacrity by Russian thought. The originality of Spengler lies however in this, that he has no desire to be a romantic, he does not wish to anguish over the dying great culture of the past. He wants to live in the present, he wants to accept the pathos of civilisation. He wants to be a citizen of the worldwide city of civilisation. He preaches a civilisation's will to world power. He is consentual to trading off religion, philosophy, art for technology, for the draining of swamps and the erecting of bridges, for the invention of machines. The uniqueness of Spengler lies in this, that there has not been yet a man of civilisation, a drainer of swamps, endowed with such an awareness as with Spengler, a sad awareness of the inexorable decline of the old culture, endowed with such a keenness and such a gift of penetration into the culture of the past. Spengler's self-feeling for civilisation and his self-awareness are at the root contradictory and ambiguous. In him there is not civilisation's arbitrary sense of value and self-smugness, there is not that faith in the absolute excellence of its own epoch, of its own generation over all the epochs and generations that went before. It is impossible to construct a civilisation, to defend the interests of a civilisation, to dry up swamps with such a mindset as Spengler has. For these deeds what is necessary is a dulling of consciousness, becoming thick-skinned, with a naive faith in the endless progress of civilisation. Spengler tends to understand everything too well. He is not the new man of civilisation, he is rather, the dying Faust -- the man of the old European culture. He -- is a romantic in an era of civilisation. He wants to give the appearance, that he is interested by the engineering art, by the draining of swamps, by the erection of the world city. In actuality, he writes instead a remarkable book about the decline of European culture and by this he works a deed of culture, rather than of civilisation. He is as such unusual a cultural man, overwhelmingly a cultural man. Such people tend poorly to build the world city of civilisation. They are better at writing books. Faust hardly can be called a fine engineer, a fine maker of civilisation. He is dying at the very moment, when he decides to set about the draining of swamps. Spengler is not a man of civilisation, as he wants both himself and us to believe, - he is a man of a late and declining culture. And therefore in his book is discerned the evidence of grief, foreign to a man of civilisation. Spengler -- is a German patriot, a German nationalist and imperialist. This is clearly expressed in his booklet, "Preussentum und Sozialismus" ["The Prussian and Socialism"]. In him there is the will to world power for Germany, there is the faith, that during the period of civilisation, such as still remains for Western Europe, this world power of Germany will be realised. He combines with civilisation this will and this faith for himself, he finds for himself a place within it. But the history of recent years has inflicted such a blow to the imperialistic mindset of Spengler. If imperialism and socialism -- be not one and the same thing, then -- certainly, Spengler is moreso the imperialist, than a socialist. The civilisation of a world city however is beginning to move more rapidly in the direction of realisation of a world power and world kingdom, the kingdom of this world, through socialism, rather than through imperialism.

* * *

Our era has features of affinity with the Hellenistic era. The Hellenistic era brought to an end the culture of antiquity. And, according to the thought of Spengler, this was a transition of the culture of antiquity over into civilisation. Suchlike is the doomed lot of every culture. And for both our era and for the Hellenistic era alike there is characteristic the mutual interaction of East and West, the meeting and coming together of all cultures and all races, a syncretism, the universalism of civilisation, the feeling of an end-time, the demise of an historical era. And in our era too the civilisation of the West turns towards the East and the trans-cultural people of this civilisation seek for light from the East. And in our era too within the various theosophic and mystical currents there occurs the jumbling together and combining of various systems of beliefs and cults. And in our era too there is the will towards a worldwide uniting in imperialism and the selfsame will finds expression also in socialism. Cultures and states cease to be nationally isolated. The individuality of the cultures passes over into the universality of civilisation. And in our era too there is the thirst to believe and a powerlessness to believe, a thirst to create and a powerlessness to create. And in our era too there predominates an Alexandrianism both in thought and in creativity. Within history daylike and nightlike eras follow in succession. The Hellenistic era was a transition from the daylight of the Hellenic world over to the night of the Medieval Dark Ages. And we stand at the threshhold of a new night era. The daytime of modern history is at an end. Its rational light is dying down. Evening ensues. And it is not Spengler alone who sees the signs of the encroaching twilight. Our time in many of its portents is reminiscent of the beginning of the early Middle Ages. The have begun the processes of drawing back and consolidation, similar to the processes of drawing back and consolidation during the time of the emperor Diocletian. And it is not so improbable an opinion, to imagine that there is beginning a feudalisation of Europe. The process of the collapse of states is transpiring parallel to an universalistic uniting. There are occurring enormous transmigrations and displacements of masses of mankind. And there will perhaps ensue a new chaos of peoples, from which nowise quickly will a new orderly cosmos take shape.

The World War has drawn Western Europe out of its customary, its established boundaries. Central Europe lies inwardly devastated. Its powers not only materially, but also spiritually, have become overstrained. Civilisation through imperialism and through socialism has to pour forth across the surface of all the earth, has to move even towards the East. Into the civilisation will be brought ever new masses of mankind, new segments. But the new Middle Ages will be a civilised barbarism, a barbarism amidst machines, and not amidst forests and fields. The great and sacred traditions of culture will turn inward. The true spiritual culture, perhaps, will happen to experience a catacomb period. The true spiritual culture, having survived its Renaissance period, having gone through its humanistic pathos, will happen to return to certain principles of a religious medieval culture, not a barbarian Middle Ages, but rather a cultural Middle Ages. Upon the pathways of the modern, the humanistic, the renaissance history, everything is already exhausted. Faust upon the paths of an outward endlessness of aspirations exhausted his powers, he wore down his spiritual energy. Still, there remains for him movement towards an inner infinity. In one of his aspects, Faust has had to totally surrender himself over to the external material civilisation, a civilised barbarism. Though in another of his aspects he has to be faithful to the eternal spiritual culture, the symbolic existence of which was expressed by the mystical chorus at the finish of the second part of "Faust". Suchlike is the fate of the Faustian soul, the fate of European culture. The future is twofold. With Spengler, the preeminence of spiritual culture is sundered. It passes as it were over totally into civilisation and dies. Spengler does not believe in an abiding meaning to world life, he does not believe in the eternal aspect of a spiritual reality. But even if spiritual culture should perish amidst the quantities, it then still will be preserved and abide amidst the qualities. It was carried forth both through the barbarity and night of the old Middle Ages. It will be carried forth also through the barbarity and night of the new Middle Ages, prior to the dawn of a new day, to a coming Christian Renaissance, when there will appear the St. Francis and the Dante of the new epoch.

* * *

The truths of science for Spengler are not independent truths, but are rather truths relevant of the culture, of cultural styles. And the truths of physics are connected with the souls of a culture. There is a very remarkable chapter about the Faustian and Apollonian nature-knowledge. Mighty strides in physics have been characteristic of our era. Within physics there is occurring a genuine revolution. But the discoveries, which the physics of our era is uncovering, are characteristic of the decline of a culture. Entropy, connected with the Second Law of Thermodynamics, radioactivity and the decaying apart of atoms of matter, the Law of Relativity -- all this tends to shake the solidity and stability of the physico-mathematical world-perception, and it undermines faith in the lasting existence of our world. I might say, that all this -- represents a physical apocalypsis, a teaching about the inevitability of the physical end of the world, the death of the world. Only during the era of the waning of European culture does there arise such an "apocalyptic" disposition within physics. What a difference it is from the physics of Newton. Newton in his physics did not give his own interpretation of the Apocalypsis. The physics of our day can be termed the pre-death thoughts of Faust. It has become impossible to seek for stability in the physical world order. Physics posits a death sentence for the world. The world is perishing in its proportionate discharge of warm energy into the universe, of energy, unreturnable into other forms of energy. The creating energies at work in forming the manifold of the cosmos, are subsiding. The world is perishing from an irreversible and insurmountable striving towards physical equilibrium. And is not the striving towards equilibrium, towards equality, in the social world that same sort of entropy, that same ruination of the social cosmos and culture in a proportionate discharge of warm energy, unreturnable in any sort of energy as is creative of culture? A pondering over the themes, posited by Spengler, leads to these bitter thoughts. But the bitterness of these thoughts ought not to be inescapable and gloomy. Not only physics, but also sociology, do not have belonging to them the final word in deciding the fates of the world and of man. The loss of a physical stability is not an irreversible loss. It is in the spiritual world that it is necessary to seek for stability. It is in the depths that it is necessary to seek for points of support. The world as external lacks infinite perspectives. The absurdity within it has been shown over the ages. But there is apparent an infinite inner world. And it is with it that there ought to be connected our hopes.

* * *

In the large book of Spengler nothing is said about Russia. Only in the table of contents of the projected second volume is there a final chapter entitled -- "Das Russentum und die Zukunft" ["The Russian and the Future"]. There are grounds to think, that Spengler sees in the Russian East that new world, which will come to replace the dying world of the West: in his booklet "Preussentum und Sozialismus" several pages are devoted to Russia. Russia for him -- is a mysterious world, incomprehensible for the world of the West. The soul of Russia is still more remote and ungraspable for Western man, than is the soul of Greece or of Egypt. Russia is an apocalyptic revolt against antiquity. Russia -- is religious and nihilistic. In Dostoevsky is revealed the mystery of Russia. In the East can be expected the appearance of a new type of culture, of a new soul of culture. Yet this too contradicts the suggestions about Russia as a land nihilistic and hostile to culture. In the thoughts of Spengler, ultimately not followed out to the end, there is a sort of something turned backwards, where its opposite end seems an assertion of Slavophilism. And for us these thoughts are of interest, this turning of the West towards Russia, these expectations, connected with Russia. We are situated in more propitious a position, than is Spengler and the people of the West. For us the Western culture is attainable and graspable. The soul of Europe does not represent for us a soul remote and incomprehensible. We are in an inner communion with it, we sense in ourselves its energy. And yet at the same time we are the Russian East. Therefore the scope of Russian thought has to be broader, from its apparent remoteness. The philosophy of history, towards which the thought of our era turns, with great success has to be worked out in Russia. The philosophy of history always was of a basic interest within Russian thought, beginning with Chaadayev. That, which we are experiencing at present, ought ultimately to lead us out of our isolated existence. Granted that at present we are still moreso pushed back eastwards, but at the end of this process we shall cease to be the isolated East. Whatever happens with us, we inevitably have to emerge onto the world stage. Russia -- is at the middle between East and West. In it clash two torrents of world history, the Eastern and the Western. In Russia is hidden a mystery, which we ourselves cannot fully fathom. But this mystery is connected with a resolving of whatever the themes of world history. Our hour has still not come. It will be connected with the crisis of European culture. And therefore such books, as the book of Spengler, cannot but excite us. Such books are closer to us, than to the European peoples. This -- is our style of book.

Nikolai Berdyaev.

(1922)

© 2003 by translator Fr. S. Janos

(1922 - 59,1 -en)

PREDSMERTNYE MYSLI FAUSTA. Berdyaev's article is the 3rd of a four part anthology, "Osval'd Shpengler i Zakat Evropy", first published by book-publisher "Bereg" 1922, Moscow, p. 55-72. This entire 1922 Oswald Spengler anthology has been included in the V. V. Sapov edited Berdyaev-reprint under the partially inclusive title, "Smysl Istorii; Novoe Srednevekov'e", Publisher "Kanon", 2002 Moscow, p. 312-404; the Berdyaev title p. 364-381. (The other three selections included in this Spengler anthology are: F. Stepun -- "Osval'd Shpengler i 'Zakat Evropy'", S. Frank -- "Krizis zapadnoi kul'tury", Ya. Bukshpan -- "Nepreodolennyi ratsionalizm".

Е-текст по-русский: Кротова ..

Return to Berdyaev Online Library..

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

« La peur est l’un des symptômes de notre temps. Elle nous désarme d’autant plus qu’elle succède à une époque de grande liberté individuelle, où la misère même, telle que la décrit Dickens, par exemple, était presque oubliée. »

« La peur est l’un des symptômes de notre temps. Elle nous désarme d’autant plus qu’elle succède à une époque de grande liberté individuelle, où la misère même, telle que la décrit Dickens, par exemple, était presque oubliée. » « On assiste à des enchères où l’on dispute s’il vaut mieux fuir, se cacher ou recourir au suicide, et l’on voit des esprits qui, gardant encore toute leur liberté, cherchent déjà par quelles méthodes et quelles ruses ils achèteront la faveur de la crapule, quand elle aura pris le pouvoir. »

« On assiste à des enchères où l’on dispute s’il vaut mieux fuir, se cacher ou recourir au suicide, et l’on voit des esprits qui, gardant encore toute leur liberté, cherchent déjà par quelles méthodes et quelles ruses ils achèteront la faveur de la crapule, quand elle aura pris le pouvoir. »

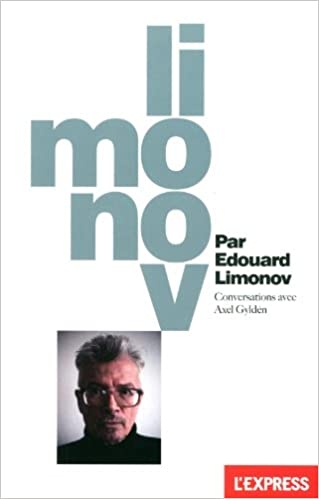

Suite à une affectation paternelle, le garçon grandit dans la ville industrielle de Kharkov aujourd’hui en Ukraine. Ce surdoué fut d’abord « un lecteur assidu, dévorant tout ce qui [lui] tombait sous la main (1) ». Au collège, il joue au garnement insupportable avec des résultats scolaires décevants. À la fin de l’adolescence, il commet des larcins mineurs. Mortifié d’être exempté du service militaire, ce myope ne supporte plus la pesante ambiance sous Khrouchtchev et Brejnev. Incontrôlable et provocateur, il quitte l’Union soviétique en 1974. Quelques plumitifs y ont vu l’indice que derrière une apparente attitude dissidente culturelle et artistique, Limonov aurait été un agent clandestin du KGB au même titre d’ailleurs que l’« arctiviste onanophobe » Piotr Pavlenski…

Suite à une affectation paternelle, le garçon grandit dans la ville industrielle de Kharkov aujourd’hui en Ukraine. Ce surdoué fut d’abord « un lecteur assidu, dévorant tout ce qui [lui] tombait sous la main (1) ». Au collège, il joue au garnement insupportable avec des résultats scolaires décevants. À la fin de l’adolescence, il commet des larcins mineurs. Mortifié d’être exempté du service militaire, ce myope ne supporte plus la pesante ambiance sous Khrouchtchev et Brejnev. Incontrôlable et provocateur, il quitte l’Union soviétique en 1974. Quelques plumitifs y ont vu l’indice que derrière une apparente attitude dissidente culturelle et artistique, Limonov aurait été un agent clandestin du KGB au même titre d’ailleurs que l’« arctiviste onanophobe » Piotr Pavlenski…

Libéré, Limonov se rapproche de l’opposition libérale anti-Poutine. Il purge alors diverses peines de détention administrative en tant que principal animateur de la contestation en 2010 – 2011. Il se ravise en 2014 et se sépare des libéraux quand le président russe soutient indirectement la révolte de Donetsk et de Lougansk, et annexe la Crimée. Ses livres, Le Vieux (Bartillat, 2015) et Kiev Kaputt, justifient ce surprenant revirement, car « Poutine ne s’est pas réconcilié avec Limonov (9) ». S’il salue la diplomatie du Kremlin, il continue néanmoins à s’opposer au poutinisme intérieur, économique et sociale. Il affirme « être plus radical et plus à droite que le pouvoir dans le domaine de la politique extérieure (10) ». En revanche, « je suis beaucoup plus à gauche que le pouvoir en politique intérieure, poursuit Limonov. J’exige la nationalisation de l’industrie gazière et pétrolière. J’exige la confiscation des biens des grosses fortunes, la privation pour celles-ci de la citoyenneté russe et leur expulsion de Russie (11). »

Libéré, Limonov se rapproche de l’opposition libérale anti-Poutine. Il purge alors diverses peines de détention administrative en tant que principal animateur de la contestation en 2010 – 2011. Il se ravise en 2014 et se sépare des libéraux quand le président russe soutient indirectement la révolte de Donetsk et de Lougansk, et annexe la Crimée. Ses livres, Le Vieux (Bartillat, 2015) et Kiev Kaputt, justifient ce surprenant revirement, car « Poutine ne s’est pas réconcilié avec Limonov (9) ». S’il salue la diplomatie du Kremlin, il continue néanmoins à s’opposer au poutinisme intérieur, économique et sociale. Il affirme « être plus radical et plus à droite que le pouvoir dans le domaine de la politique extérieure (10) ». En revanche, « je suis beaucoup plus à gauche que le pouvoir en politique intérieure, poursuit Limonov. J’exige la nationalisation de l’industrie gazière et pétrolière. J’exige la confiscation des biens des grosses fortunes, la privation pour celles-ci de la citoyenneté russe et leur expulsion de Russie (11). » Il confirme à Axel Glydén qu’« en Occident, vous êtes vieux, archaïques et vous allez tous mourir, au sens intellectuel du mot. À force de ressasser le passé, vos cerveaux sont encombrés d’interdits. Et vous allez faire du surplace pendant des siècles. Les intellectuels français sont manichéens. Hantés par le passé, ils sont enfermés dans des dogmes (14) ». Ayant connu la « stagnation » brejnévienne du début des années 1970, Édouard Limonov perçoit une stagnation mortifère qui imprègne à son tour l’Occident.

Il confirme à Axel Glydén qu’« en Occident, vous êtes vieux, archaïques et vous allez tous mourir, au sens intellectuel du mot. À force de ressasser le passé, vos cerveaux sont encombrés d’interdits. Et vous allez faire du surplace pendant des siècles. Les intellectuels français sont manichéens. Hantés par le passé, ils sont enfermés dans des dogmes (14) ». Ayant connu la « stagnation » brejnévienne du début des années 1970, Édouard Limonov perçoit une stagnation mortifère qui imprègne à son tour l’Occident.

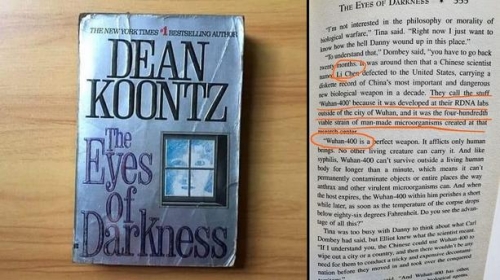

La Chine accuse les États-Unis ! Nous avions déjà la crise sanitaire et la crise économique, voici peut-être une nouvelle crise diplomatique majeure puisqu’un porte-parole du ministère chinois des Affaires étrangères suggère que l’épidémie n’est pas nécessairement accidentelle…et qu’elle provient d’Amérique !

La Chine accuse les États-Unis ! Nous avions déjà la crise sanitaire et la crise économique, voici peut-être une nouvelle crise diplomatique majeure puisqu’un porte-parole du ministère chinois des Affaires étrangères suggère que l’épidémie n’est pas nécessairement accidentelle…et qu’elle provient d’Amérique !

D'une poignée de main ferme, il accueillait les visiteurs sans manières dans son appartement de 100 mètres carrés à la déco minimaliste: quelques chaises, un bureau en formica, un fauteuil en skaï et, sur les murs gris, trois ou quatre photos où l'on reconnaissait le maître des lieux, pour la plupart des clichés pris à Paris, dans le Marais, où il avait vécu au début des années 1980, et devant Notre-Dame.

D'une poignée de main ferme, il accueillait les visiteurs sans manières dans son appartement de 100 mètres carrés à la déco minimaliste: quelques chaises, un bureau en formica, un fauteuil en skaï et, sur les murs gris, trois ou quatre photos où l'on reconnaissait le maître des lieux, pour la plupart des clichés pris à Paris, dans le Marais, où il avait vécu au début des années 1980, et devant Notre-Dame.  Cette manière de parler peut être déstabilisante. Elle est aussi rafraîchissante. Car, au moins les propos de Limonov procédaient-ils d'une pensée réellement personnelle, hors sol et hors cadre, qui a le mérite d'interroger les certitudes. Tout en l'écoutant énoncer ses vérités dégoupillées, il fallait toujours se demander si elles étaient à prendre au second ou au troisième degré. Tout bien réfléchi, c'était au premier.

Cette manière de parler peut être déstabilisante. Elle est aussi rafraîchissante. Car, au moins les propos de Limonov procédaient-ils d'une pensée réellement personnelle, hors sol et hors cadre, qui a le mérite d'interroger les certitudes. Tout en l'écoutant énoncer ses vérités dégoupillées, il fallait toujours se demander si elles étaient à prendre au second ou au troisième degré. Tout bien réfléchi, c'était au premier.

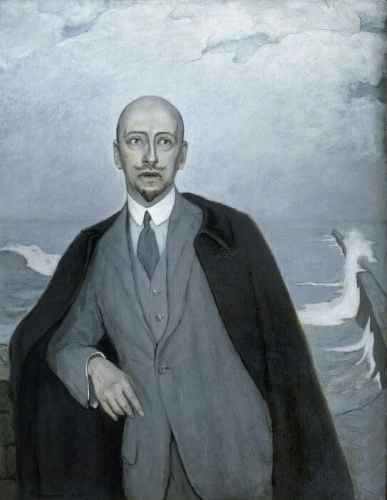

In her 2013 biography of d’Annunzio,

In her 2013 biography of d’Annunzio,

He earned fame in Berlin, where he became a hero of the international artistic community. It was in Berlin that he published his resonant essay "Zur Psychologie des Individuums. I - Chopin und Nietzsche. II - Ola Hansson" 1892 as well as poems Totenmesse, 1895 (Polish version: Requiem aeternam, 1904), Vigilien, 1895 (Polish version: Z cyklu wigilii, 1899), De profundis, 1895 (Polish version 1900), Androgyne, 1900. They introduced themes which would be central to all of his work: individualism, the metaphysical and social status of creative individuals, fate of geniuses, the sense of such attributes of genius as "degeneration" and "illness". He continued to present his philosophical views in essays published in a number of magazines and later collected in the volumes "Auf den Wegen der Seele" 1897 ("Na drogach duszy" [On the Paths of the Soul], 1900), "Szlakiem duszy polskiej" [On the Paths of the Polish Soul], 1917, "Ekspresjonizm, Słowacki i Genesis z ducha" [Expressionism, Slowacki and Genesis from the Spirit], 1918.

He earned fame in Berlin, where he became a hero of the international artistic community. It was in Berlin that he published his resonant essay "Zur Psychologie des Individuums. I - Chopin und Nietzsche. II - Ola Hansson" 1892 as well as poems Totenmesse, 1895 (Polish version: Requiem aeternam, 1904), Vigilien, 1895 (Polish version: Z cyklu wigilii, 1899), De profundis, 1895 (Polish version 1900), Androgyne, 1900. They introduced themes which would be central to all of his work: individualism, the metaphysical and social status of creative individuals, fate of geniuses, the sense of such attributes of genius as "degeneration" and "illness". He continued to present his philosophical views in essays published in a number of magazines and later collected in the volumes "Auf den Wegen der Seele" 1897 ("Na drogach duszy" [On the Paths of the Soul], 1900), "Szlakiem duszy polskiej" [On the Paths of the Polish Soul], 1917, "Ekspresjonizm, Słowacki i Genesis z ducha" [Expressionism, Slowacki and Genesis from the Spirit], 1918. Przybyszewski translated the philosophical issues raised in his essays and narrative poems into the language of literary prose and drama. A very prolific writer, he published many novels, all of them trilogies, in German and Polish, notably Homo Sapiens, German edition 1895-96, Polish edition. 1901; Satans Kinder, 1897; Synowie ziemi [Sons of the Earth], 1904-11; Dzieci nędzy [Children of Poverty], 1913-14; Krzyk [The Cry], 1917; Il Regno Doloroso, 1924. All of his novels had basically the same type of protagonists, i.e. outstanding individuals destroyed by the social world and by their internal demons. These doomed characters were presented in extreme, frequently pathological, emotional states of alcoholism, jealousy, destructive love. The plots were weak and served as a pretext to analyze the characters' internal states. This new type of the protagonist required appropriate narration techniques that were different from those used in realistic novels. Przybyszewski made innovative use of (seemingly) indirect speech and of internal monologue.

Przybyszewski translated the philosophical issues raised in his essays and narrative poems into the language of literary prose and drama. A very prolific writer, he published many novels, all of them trilogies, in German and Polish, notably Homo Sapiens, German edition 1895-96, Polish edition. 1901; Satans Kinder, 1897; Synowie ziemi [Sons of the Earth], 1904-11; Dzieci nędzy [Children of Poverty], 1913-14; Krzyk [The Cry], 1917; Il Regno Doloroso, 1924. All of his novels had basically the same type of protagonists, i.e. outstanding individuals destroyed by the social world and by their internal demons. These doomed characters were presented in extreme, frequently pathological, emotional states of alcoholism, jealousy, destructive love. The plots were weak and served as a pretext to analyze the characters' internal states. This new type of the protagonist required appropriate narration techniques that were different from those used in realistic novels. Przybyszewski made innovative use of (seemingly) indirect speech and of internal monologue.

Ceci posé, le lecteur du récit ne peut manquer d’être frappé par le soin qui y a été mis à casser les stéréotypes et autres images d’Epinal. Le meneur de l’insurrection à Waldeghem, Bruno Halinx, n’a rien du fruste campagnard qu’on serait tenté de se représenter dans ce rôle. Fils du notaire de la localité, il a pu bénéficier d’un enseignement de qualité à l’école latine des augustins d’Anvers. Le futur héros est raffiné, quelque peu efféminé même, au point que le début de l’œuvre ressemble à un roman d’apprentissage, où la force des circonstances transforme un homme peu viril en chef intrépide.

Ceci posé, le lecteur du récit ne peut manquer d’être frappé par le soin qui y a été mis à casser les stéréotypes et autres images d’Epinal. Le meneur de l’insurrection à Waldeghem, Bruno Halinx, n’a rien du fruste campagnard qu’on serait tenté de se représenter dans ce rôle. Fils du notaire de la localité, il a pu bénéficier d’un enseignement de qualité à l’école latine des augustins d’Anvers. Le futur héros est raffiné, quelque peu efféminé même, au point que le début de l’œuvre ressemble à un roman d’apprentissage, où la force des circonstances transforme un homme peu viril en chef intrépide.

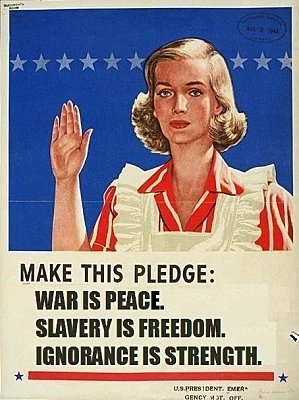

La Novlangue

La Novlangue

Conclusion

Conclusion

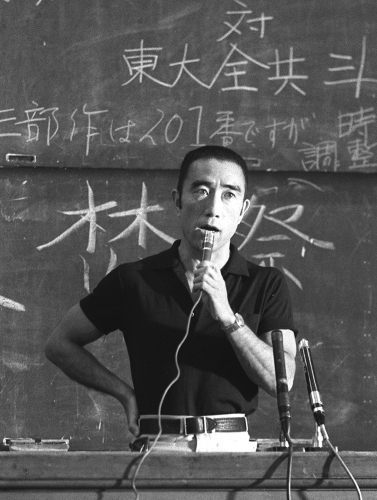

Dr. Joyce maintained that “Mishima, of course, never explored the Emperor’s role in World War II in any depth, and his chief fixation appears solely to have been the decision of the Emperor to accede to Allied demands and ‘become human.’” This is a baffling statement which again simply betrays Dr. Joyce’s lack of knowledge. Besides rightfully decrying the Showa Emperor’s self-demotion to “become human” from his traditional status of “Arahitogami” (god in human form or demigod), Mishima also critically examined the Emperor’s role in politics before, during, and after the war, which revealed that what Mishima essentially venerated was not the individual Tennō but the Kōtō (the unique and time-honored Japanese monarchical system).

Dr. Joyce maintained that “Mishima, of course, never explored the Emperor’s role in World War II in any depth, and his chief fixation appears solely to have been the decision of the Emperor to accede to Allied demands and ‘become human.’” This is a baffling statement which again simply betrays Dr. Joyce’s lack of knowledge. Besides rightfully decrying the Showa Emperor’s self-demotion to “become human” from his traditional status of “Arahitogami” (god in human form or demigod), Mishima also critically examined the Emperor’s role in politics before, during, and after the war, which revealed that what Mishima essentially venerated was not the individual Tennō but the Kōtō (the unique and time-honored Japanese monarchical system).

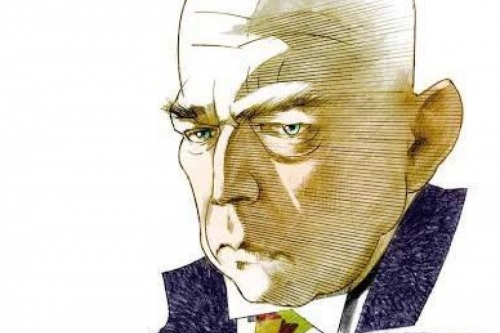

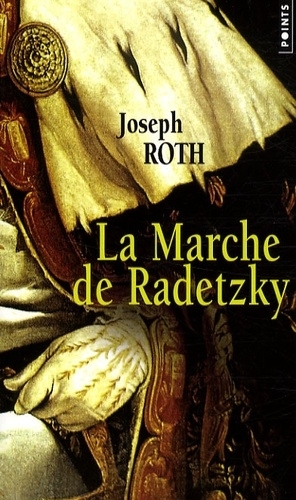

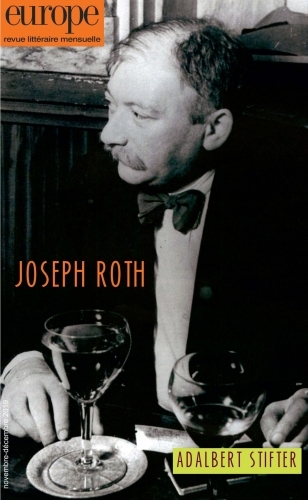

Il y a quatre-vingt ans, mourait en exil à Paris, à l’Hôpital Necker, l’un des plus grands écrivains de l’ancienne Double Monarchie austro-hongroise, Joseph Roth (1894-1939). Issu d’une famille juive des confins galiciens de l’Empire, Roth se convertit au catholicisme et passa du socialisme utopique au monarchisme nostalgique. Il fut, avec ses superbes romans La Marche de Radetzky et La Crypte des Capucins, le mémorialiste d’un empire disparu et le théoricien d’un conservatisme éclairé, celui des Habsbourg. Deux excellentes raisons de le lire !

Il y a quatre-vingt ans, mourait en exil à Paris, à l’Hôpital Necker, l’un des plus grands écrivains de l’ancienne Double Monarchie austro-hongroise, Joseph Roth (1894-1939). Issu d’une famille juive des confins galiciens de l’Empire, Roth se convertit au catholicisme et passa du socialisme utopique au monarchisme nostalgique. Il fut, avec ses superbes romans La Marche de Radetzky et La Crypte des Capucins, le mémorialiste d’un empire disparu et le théoricien d’un conservatisme éclairé, celui des Habsbourg. Deux excellentes raisons de le lire ! Comme l’écrit justement Claudio Magris, qui a tant fait pour le ressusciter, Joseph Roth incarna bien « l’aède du crépuscule de la vieille Europe et de l’identité individuelle », quels que fussent ses masques qu’il porta avec une sorte de dandysme narquois, celui du juif galicien converti au catholicisme autrichien ou celui du caporal qui se prétendit officier de l’Armée impériale et royale. Désespéré par la perte de sa patrie, réduit à une misère noire que son ami Zweig, entre autres bienfaiteurs, tenta d’atténuer, Roth finit ses jours dans deux endroit mythiques de la Rive gauche, tous deux situés en face l’un de l’autre à l’ombre du Sénat, l’Hôtel Foyot, où logèrent Joseph II et Rilke, détruit en 1938 au moment de l’Anschluss, et le Café Tournon, demeuré intact, où je me rends en pèlerinage à chacun de mes passages parisiens, seul ou en compagnie de l’un ou l’autre confrère. J’aime à y rêver à ces émigrés monarchistes devant un verre de bourgogne.

Comme l’écrit justement Claudio Magris, qui a tant fait pour le ressusciter, Joseph Roth incarna bien « l’aède du crépuscule de la vieille Europe et de l’identité individuelle », quels que fussent ses masques qu’il porta avec une sorte de dandysme narquois, celui du juif galicien converti au catholicisme autrichien ou celui du caporal qui se prétendit officier de l’Armée impériale et royale. Désespéré par la perte de sa patrie, réduit à une misère noire que son ami Zweig, entre autres bienfaiteurs, tenta d’atténuer, Roth finit ses jours dans deux endroit mythiques de la Rive gauche, tous deux situés en face l’un de l’autre à l’ombre du Sénat, l’Hôtel Foyot, où logèrent Joseph II et Rilke, détruit en 1938 au moment de l’Anschluss, et le Café Tournon, demeuré intact, où je me rends en pèlerinage à chacun de mes passages parisiens, seul ou en compagnie de l’un ou l’autre confrère. J’aime à y rêver à ces émigrés monarchistes devant un verre de bourgogne.

All this having been said, I still encourage people to watch Paul Schrader’s film on Mishima and to read Mishima’s guide to Hagakure (or better yet, Hagakure itself). I will myself, when time permits, try to read Mishima’s later more political fiction (e.g. Runaway Horses) and other nonfiction. A work of art is no less compelling, a logical argument no less persuasive, whatever the author’s personal deficiencies or proclivities.

All this having been said, I still encourage people to watch Paul Schrader’s film on Mishima and to read Mishima’s guide to Hagakure (or better yet, Hagakure itself). I will myself, when time permits, try to read Mishima’s later more political fiction (e.g. Runaway Horses) and other nonfiction. A work of art is no less compelling, a logical argument no less persuasive, whatever the author’s personal deficiencies or proclivities.

To his credit, Ryan does not spend much ink on critical analyses of the various presentations. That would make for a very fat and dreary book. In nearly every instance he’d have to tell us that the production was uneven and woefully miscast. I wondered if he was going to carp about the misconceived film adaptation of Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1997; American title: A Merry War). Not a bit of it; he leaves it to us to do the carping and ridicule. What he does provide is a rich concordance of Orwell presentations over the years, with often amazing production notes, technical details, and contemporary press notices. And if you don’t care to get that far into weeds, George Orwell on Screen is still an indispensable guidebook, pointing you to all sorts of bio-documentaries and dramatizations you might never discover on your own. This is particularly true of the many (mostly) BBC docos produced forty or fifty years ago, where you find such delights as Malcolm Muggeridge and Cyril Connolly lying down in tall grass and trading tales about their late, great friend.

To his credit, Ryan does not spend much ink on critical analyses of the various presentations. That would make for a very fat and dreary book. In nearly every instance he’d have to tell us that the production was uneven and woefully miscast. I wondered if he was going to carp about the misconceived film adaptation of Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1997; American title: A Merry War). Not a bit of it; he leaves it to us to do the carping and ridicule. What he does provide is a rich concordance of Orwell presentations over the years, with often amazing production notes, technical details, and contemporary press notices. And if you don’t care to get that far into weeds, George Orwell on Screen is still an indispensable guidebook, pointing you to all sorts of bio-documentaries and dramatizations you might never discover on your own. This is particularly true of the many (mostly) BBC docos produced forty or fifty years ago, where you find such delights as Malcolm Muggeridge and Cyril Connolly lying down in tall grass and trading tales about their late, great friend.

En effet, dans deux de ses romans, Mon Royaume pour un cheval et La Guerre civile, Mohrt évoque à la fois Drieu, qu’il avait rencontré dans le Paris de la fin de l’Occupation, et surtout Bassompierre, son camarade aux Chasseurs alpins sur le front italien, devenu Bargemont dans plusieurs de ses romans, condamné à mort après la Libération et fusillé, malgré l’intervention de grands résistants, pour son engagement sur le front russe. Singulière figure que celle de Bassompierre, qui incarne les déchirements d’une certaine France et dont le tragique destin a profondément marqué Mohrt : une partie importante de son œuvre témoigne de son inconsolable tristesse.

En effet, dans deux de ses romans, Mon Royaume pour un cheval et La Guerre civile, Mohrt évoque à la fois Drieu, qu’il avait rencontré dans le Paris de la fin de l’Occupation, et surtout Bassompierre, son camarade aux Chasseurs alpins sur le front italien, devenu Bargemont dans plusieurs de ses romans, condamné à mort après la Libération et fusillé, malgré l’intervention de grands résistants, pour son engagement sur le front russe. Singulière figure que celle de Bassompierre, qui incarne les déchirements d’une certaine France et dont le tragique destin a profondément marqué Mohrt : une partie importante de son œuvre témoigne de son inconsolable tristesse. Ecoutons Mohrt évoquer ce jeune officier démobilisé après une campagne bien courte qui, contrairement à celle du jeune Stendhal, ne fit pas de lui ce dragon victorieux entrant dans Milan pour occuper - en vainqueur - une loge à la Scala : « Je n’avais plus confiance en moi, parce que j’avais perdu confiance en mon pays. Comme lui, je le sentais vaincu. Je passais mon temps à ruminer la défaite, cherchant à en préciser les causes, si évidentes pour moi ». C’est à ce moment que cet avocat réfugié en zone libre se met à lire les auteurs qui, après la défaite de 1870, proposent une réforme intellectuelle et morale qui ne viendra pas. Même espoir chez Mohrt d’un relèvement, même hantise de la guerre civile - qui viendra, car aux massacres de la Commune succèdent ceux de l’Occupation et de la Libération. Mohrt a dit et répété qu’il avait l’impression d’assister, « à la naissance d’une vérité officielle qui contredisait tout ce que j’avais vu ou cru voir ». Les années d’après la défaite, il les vécut « en somnambule » et dans l’amertume.

Ecoutons Mohrt évoquer ce jeune officier démobilisé après une campagne bien courte qui, contrairement à celle du jeune Stendhal, ne fit pas de lui ce dragon victorieux entrant dans Milan pour occuper - en vainqueur - une loge à la Scala : « Je n’avais plus confiance en moi, parce que j’avais perdu confiance en mon pays. Comme lui, je le sentais vaincu. Je passais mon temps à ruminer la défaite, cherchant à en préciser les causes, si évidentes pour moi ». C’est à ce moment que cet avocat réfugié en zone libre se met à lire les auteurs qui, après la défaite de 1870, proposent une réforme intellectuelle et morale qui ne viendra pas. Même espoir chez Mohrt d’un relèvement, même hantise de la guerre civile - qui viendra, car aux massacres de la Commune succèdent ceux de l’Occupation et de la Libération. Mohrt a dit et répété qu’il avait l’impression d’assister, « à la naissance d’une vérité officielle qui contredisait tout ce que j’avais vu ou cru voir ». Les années d’après la défaite, il les vécut « en somnambule » et dans l’amertume. Peu d’écrivains français peuvent se vanter d’avoir enseigné aux prestigieuses universités de Yale ou de Californie ; très peu nombreux sont ceux qui reçurent en outre la proposition d’intégrer le corps professoral de Princeton. Paradoxe pour ce chouan nourri de Maistre et de Maurras, et qui fut, des décennies durant, l’un des principaux passeurs en France - chez Gallimard - des plus grands écrivains américains du siècle vingtième : qui se souvient que c’est Mohrt qui introduisit Roth et Kerouac chez Gallimard ? Sans oublier son travail en faveur de Faulkner , à qui le liait une sensibilité commune : « Les hommes de l’Ouest ont entre eux bien des ressemblances. Nous étions un peu chouans. Avec M. de Charrette, nous serions allés « chasser la perdrix », nous étions sudistes ».

Peu d’écrivains français peuvent se vanter d’avoir enseigné aux prestigieuses universités de Yale ou de Californie ; très peu nombreux sont ceux qui reçurent en outre la proposition d’intégrer le corps professoral de Princeton. Paradoxe pour ce chouan nourri de Maistre et de Maurras, et qui fut, des décennies durant, l’un des principaux passeurs en France - chez Gallimard - des plus grands écrivains américains du siècle vingtième : qui se souvient que c’est Mohrt qui introduisit Roth et Kerouac chez Gallimard ? Sans oublier son travail en faveur de Faulkner , à qui le liait une sensibilité commune : « Les hommes de l’Ouest ont entre eux bien des ressemblances. Nous étions un peu chouans. Avec M. de Charrette, nous serions allés « chasser la perdrix », nous étions sudistes ».