samedi, 03 janvier 2015

Ernst Jünger's The Glass Bees

Ernst Jünger's The Glass Bees

Matthew Gordon

(From Synthesis)

& http://www.wermodandwermod.com

Ernst Jünger

Louise Bogan & Elizabeth Mayer (transl.)

The Glass Bees

New York Review Books, 2000

THE Glass Bees is an introspective novel about a quiet but dignified cavalry officer called Richard. Unable to adjust to life after war and needing money, he applies for a security job at the headquarters of the mysterious oligarch Zapparoni. Confronted with mechanical and psychological trials, the dream becomes a nightmare, and Richard is forced to contemplate his place in the modern world and the nature of reality itself.

THE Glass Bees is an introspective novel about a quiet but dignified cavalry officer called Richard. Unable to adjust to life after war and needing money, he applies for a security job at the headquarters of the mysterious oligarch Zapparoni. Confronted with mechanical and psychological trials, the dream becomes a nightmare, and Richard is forced to contemplate his place in the modern world and the nature of reality itself.

Although philosophical and lyrical, this book is nonetheless a tense page-turner with all the qualities of great sci-fi drama. The poetic imagery is highly expressive, but there are times when the sentences are clumsy and over-long, the meaning of a passage can be lost over a seemingly unnecessary paragraph break. Whether this is down to Jünger's original German or the fault of translation I couldn't possibly say. Nonetheless Ernst Jünger stands among the most lucid and skilful of continental modern writers.

Jünger's vision of the future isn't the ultra-Jacobin "boot stamping on a human face" of Nineteen-Eighty-Four - it is a subtler, more Western dystopia. Jünger is amazingly prescient in this, although he is rarely given credit for it; he predicts that the media and entertainment will rule the psyches of men, that miniaturisation and hyperreal gratification will become our new Faustian obsession and that for all the wonders and benefits of technology it is ultimately dehumanising and alienating. The new world won't be ruled by crude and brutal tyrants like Hitler, Stalin or Kim Jong Ill, but by benevolent and private businessmen, like Rupert Murdoch. We won’t be dominated by the authoritarian father-ego of Freud, but by the hedonistic-pervert of Lacan. Jünger anticipates the theory of hyperreality formulated by Baudrillard, and it is interesting that this book was published before theories on post-modernism and deconstruction became vogue.

Faced with this less than perfect future, Jünger's doesn't try to incite revolution or political struggle – his message remains the same throughout his work – but to inspire individual autonomy. Despite all outward constraints, uprightedness and self-reliance is real freedom. Jünger depicts a superficial and spiritually bankrupt future, but if he is to be believed, the potential for man to be his true self is always the same.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Livre, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, littérature, lettres, lettres allemandes, littérature allemande, ernst jünger, révolution conservatrice, abeilles de verre, allemagne, dystopie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 02 janvier 2015

Wahhabism, China, Mass Immigration: Lothrop Stoddard Rediscovered

Wahhabism, China, Mass Immigration: Lothrop Stoddard Rediscovered

Robert Locke

Ex: http://www.wermodandwermod.com

But strangely, when it comes to the great racial thinkers of the past, this rule is suspended. So complete has been their effacement by the liberal establishment, so far beyond the pale of legitimate opinion have they been pushed, that it’s almost unnecessary to repress them anymore.

But in their day these men were best-selling authors and respected scholars. They produced some serious thinking on race that I have recently been trying to rediscover. The first of my rediscoveries: Lothrop Stoddard.

Stoddard (1883-1950) was no marginal figure. He came from a distinguished New England family, had a PhD in history from Harvard, and wrote 14 well-respected books. A lifelong Unitarian and Republican, Stoddard was also a member of the American Historical Association, the American Political Science Association, and the Academy of Political Science.

As with most thinkers, not everything he said can be endorsed. What he wrote, mainly in the 1920’s and '30’s, reflects the snobberies of that time-for example, the old WASP preference for (surprise, surprise) Northern Europeans over Southern or Eastern ones. I accept this attitude as a natural preference for one’s own kind but must dismiss it if it’s proposed to inform serious politics in this country today. But, since Stoddard also wrote of the dangers of internecine jealousies undermining the unity of whites, I can forgive him.

Stoddard was not, as liberal critics like to tar all race-conscious thinkers, a Nazi or anything like it. In fact, he wrote a book critical of Nazi Germany entitled Into the Darkness, and he saw, years before the Nazis became significant, the essential falsehood of their core racial myth:

Stoddard was not, as liberal critics like to tar all race-conscious thinkers, a Nazi or anything like it. In fact, he wrote a book critical of Nazi Germany entitled Into the Darkness, and he saw, years before the Nazis became significant, the essential falsehood of their core racial myth:

Indeed the national-imperialists presently seized upon race teachings, and prostituted them to their own ends. A notable example of this is the extreme Pan-German propaganda of Houston Stewart Chamberlain and his fellows. Chamberlain makes two cardinal assumptions: he conceives modern Germany as racially purely Nordic; and he regards all Nordics outside the German linguistic-cultural group as either unconscious or renegade Teutons who must at all costs be brought into the German fold. To anyone who understands the scientific realities of race, the monstrous absurdity of these assumptions is instantly apparent. The fact is that modern Germany, far from being purely Nordic, is mainly Alpine in race. Nordic blood preponderates only in the northwest, and is merely veneered over the rest of Germany, especially in the upper classes... To let Teuton propaganda gull us into thinking of Germany as the Nordic fatherland is both a danger and an absurdity. (The Rising Tide of Color p .202)

This is the only place I know where Nazi ideology is refuted on its own terms.

Let’s look at some key passages from Stoddard’s magnum opus of 1920, The Rising Tide of Color. The first passage that really got my attention was his warning (in 1920!) that an obscure variety of Islam called Wahhabism was destined to be a major source of trouble for the Western World:

Let’s look at some key passages from Stoddard’s magnum opus of 1920, The Rising Tide of Color. The first passage that really got my attention was his warning (in 1920!) that an obscure variety of Islam called Wahhabism was destined to be a major source of trouble for the Western World:

The brown world, like the Yellow world, is today in acute reaction against white supremacy... The great dynamic of this brown reaction is the Mohammedan Revival...

Islam’s warlike vigor has impressed men’s minds ever since the far-off days when its pristine fervor bore the Fiery Crescent from France to China. But with the passing cycles this fervor waned, and a century ago Islam seemed plunged in the stupor of senile decay. .. Yet at this darkest hour a voice came crying from out the vast Arabian desert, the cradle of Islam, calling the Faithful to better things. This puritan reformer was the famous Abd-el-Wahab, and his followers, known as Wahabis, soon spread the length and breadth of the Mohammedan world, purging Islam of its sloth and rekindling the fervor of its olden days. Thus began the great Mohammedan Revival.

That revival, like all truly great regenerative movements, had its political as well as its spiritual side. One of the first things which struck the reformers was the political weakness of the Moslem World and its increasing subjection to the Christian West... The result in Islam was a fusing of religion and patriotism into a ‘sacred union’ for the combined spiritual regeneration and political emancipation of the Moslem World...

No more zealous Moslems are to be found in all the ranks of Islam than those who have sojourned longest in Europe and acquired the most intimate knowledge of its sciences and ways. Mohammedans are keenly alive to the ever-shifting uncertainties and divisions that distract the Christianity of today, and of the woeful instability of modern European institutions.” (p.56)

Here Stoddard lays bare all the things we are missing today in the analysis of these questions-a grasp of the broad sweep of history beyond anything within the reach of the neocon imagination; honesty about the reality that a Nietzschean racial will-to-power lies in the background of Western relations with the Moslem world; a prescient recognition of the key fact about these fanatics that puzzles the globalist consensus-that they are not seduced by our society on contact, like East German teenagers guzzling their first Coca-Colas.

Stoddard wrote more about Islam in his book The New World of Islam. His ability to see things from an adversary’s point of view is remarkable, and gives the lie to the myth that only people indoctrinated in multicultural sensitivity can do this. (In fact, of course, multicultural ideology tends to produce the opposite effect, as it teaches that “we’re all the same” and forbids honesty about the core Hobbesian fact of relations between peoples: they are often enemies.)

Stoddard wrote more about Islam in his book The New World of Islam. His ability to see things from an adversary’s point of view is remarkable, and gives the lie to the myth that only people indoctrinated in multicultural sensitivity can do this. (In fact, of course, multicultural ideology tends to produce the opposite effect, as it teaches that “we’re all the same” and forbids honesty about the core Hobbesian fact of relations between peoples: they are often enemies.)

Another contemporary problem whose racial aspect is taboo to discuss is cheap Oriental labor. Stoddard wrote:

Assuredly the cheapness of Chinese labor is something to make a factory owner’s mouth water... With an ocean of such labor power to draw on, China would appear to be on the eve of a manufacturing development that will act like a continental upheaval in changing the trade map of the world. (p.244)

Stoddard also foresaw the Third World unarmed invasion scenario made famous in Jean Raspail’s novel The Camp of the Saintsdecades before it began to become visible:

And let not Europe, the white brood-land, the heart of the white world, think itself immune. In the last analysis, the self-same peril menaces it too. This has long been recognized by far-sighted men. For many years economists and sociologists have discussed the possibility of Asiatic immigration into Europe. Low as wages and living standards are in many European countries, they are yet far higher than in the congested East, while the rapid progress of social betterment throughout Europe must further widen the gap and make the white continent seem a more and more desirable haven for the swarming, black-haired bread-seekers of China, India and Japan...We shall not be destroyed, perhaps, by the sudden onrush of invaders, as Rome was overwhelmed by northern hordes; we shall be gradually subdued and absorbed. (p. 289)

Stoddard wrote about one factor in the racial conflict of our time that tends to be ignored by Americans: the fact that the white race used to feel a sense of solidarity before World War I. The collapse of this sense of solidarity was one key to the unraveling of the white world’s instinct for racial self-preservation:

Thus white solidarity, while unquestionably weakened, was still a weighty factor down to August 1914. But the first shots of Armageddon saw white solidarity literally blown from the muzzles of the guns. An explosion of internecine hatred burst forth more intense and general than any ever known before... Before Armageddon there thus existed a genuine moral repugnance against settling domestic differences by calling in the alien without the gates. The Great War, however, sent all such scruples promptly into the discard. (p.208)

World War II, which Stoddard foresaw, was just the apotheosis of this process, complete with one state mythology that defined Jews, Russians and Poles as outside the pale of white civilization and another that denied the value of race altogether in favor of an economic mythology.

Finally, I would like to quote a succinct passage that can only trigger a shock of recognition:

Our present condition is the result of following the leadership of idealists and philanthropic doctrinaires, aided and abetted by the perfectly understandable demand of our captains of industry for cheap labor.” (p. xxxi) [not online]

How little has changed in 83 years!

I have the curious sense that since the melting of the geopolitical ice of the Cold War, which froze human relations into an artificial pattern for 44 years, history has not only not stopped but is in some ways going backwards-and that all these issues from earlier times are once again becoming live.

We have much to learn by revisiting the racial thinkers of the past-even if we do not always agree with them.

Source: VDARE, 21 Feb 2004.

You can get the stunning 2011 editions of Lothrop Stoddard's The Revolt Against Civilization: The Menace of the Under-Man (1922) and The French Revolution in San Domingo (1914) from our online book shop.

00:05 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : lothrop stoddard, raciologie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 01 janvier 2015

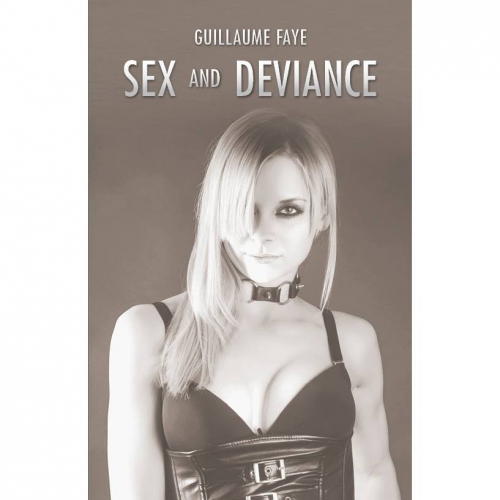

Guillaume Faye: Sex and Deviance

Guillaume Faye: Sex and Deviance

Sex and Deviance is at once a raging critique of the values underpinning contemporary Western societies and a down-to-earth, pragmatic vision of the future. Guillaume Faye is meticulous in his analysis of the points at which Western societies have deviated from their golden mean, thus having triggered the tidal wave of social ills that they are facing and can expect to face. Faye identifies at the centre of this vortex the matter of sex and sexuality, and with this proffers an answer to the perennial question: What is the glue that holds societies together?

Faye’s penetrating assault on the specious thinking of ideologues is certain to rattle the convictions of those from across the spectrum. Much more than just a socio-political exposition, this book is an invitation to shed old ways of thinking and to begin new, hard-headed discussion over the most pertinent issues of this century.

To order the book (19 £):

http://www.arktos.com/guillaume-faye-sex-and-deviance-softcover.html

Introduction

1. Funeral Dirge for the Family

The Disappearance of the Lasting Couple

Fragility of Unions Based on Romantic Love

The Politisation of Love: Symptom of Neo-Totalitarianism

Love is Not a Gift, but a Calculation

The Decline of the Duty to Continue the Lineage

Supremacy of the Anti-Familial Ideology

Consequences of the Deterioration of the Monogamous Couple

The Destruction of the Bourgeois Family Results in Chaos

Polyamory, Polygamy, Polyfidelity: Toward Involution

Spoiled Child, Sick Child

2. The Sacralisation of Homosexuality

Homophile Ideology and the ‘Struggle against Homophobia’

The Pathology of Homosexual Discourse and the Homosexual Mentality

The Egoism, Egotism, and Superficiality of ‘Gay Culture’

Proselytising the Gay Religion

Psychopathology and Fraud of the Male Homosexual Couple

The Psychology of Homosexuality

The Real Aim of the Fight against Homophobia

Are Gays Really...Gay?

The Innocence of Lesbians: Female Homosexuality

Are We All Bisexual?

The Delirium of Homoparentality

Homophobia among ‘Youths’

Gender Theory: The Latest Whim of Homosexualist and Feminist Ideology

3. Males and Females: Complex Differences

Woman’s Deep Psychology and Archetypical Representations

Questions about the Dependence and Submission of Women

Questions on Male Superiority and the ‘Dominant Male’

Effeminisation and Devirilisation of Society

Different Ways the Sex Act Is Perceived Between Men and Women

The Rising Power of Women Today

Women’s Revenge and the Possible Reversal of Sexual Polarity

The Unisex Utopia

The Dialectics of Double Domination

Love, Money, and Interest

4. Feminist Schizophrenia

The Insurmountable Contradictions of Feminism

The Two Feminisms: Sane and Insane

The Androgynous Utopia

The Dogma of ‘Parity’

Feminism and Careerism

The Feminisation of Values

5. The Farce of Sexual Liberation

An Ideology of Puritans

The False Promises of Sexual Liberation

The Illusion of Virtual Encounters

6. Sex and Perversions

Sexual Obsession and Sexual Impoverishment

Asexuals and the Extinction of Desire: Fruits of Hypersexualism

Immodesty as Anti-Eroticism

The Sexual Destructuration of Adolescents

Rapes, Sex Crimes, and Judicial Laxity

The Explosion in Sexual Violence by Minors

Violence and Sexism at School

Minors Having Abortions

Female Victims of Violence: Organised Dishonesty

The Suffering of Women in Immigrant Neighbourhoods

To Be a Homophobe is Prohibited; To Be a Paedophile is Permissible

7. Ineradicable Prostitution

Prostitution and Polytheistic Cults

Explosion and Polymorphism of Prostitution

Barter Prostitution

Regulating Prostitution

8. Sex and Origin

The Pressure for ‘Mixed’ Couples and Unions

The Race-Mixing Imperative, Soft Genocide, and Preparing the Way for Ethnic Chaos

Miscegenation as Official State Doctrine

Different Sexualities

Sexual Violence and Sexual Racism

Sexual Ethnomasochism and Divirlisation

Birthrates and Ethnic Origin

9. Islam and Sex

9. Islam and Sex

The Contradiction of Sexual Permissiveness in the Face of Islam

Macho Nervous Schizophrenia

Misogyny and Gynophobia

10. Christianity and Sex

The Canonical Sexual Morality of the Church

Failure of the Sexual and Conjugal Morality of the Church

Christian Sex-Phobia Has Provoked Sex-Mania by way of Reaction

From Sexual Sin to the Sin of Racism

11. Sex, Biotechnology, and Biopolitics

Improbable Human Nature

Biotechnology and Evolution

Rearguard Actions Against Biotechnology

What the Future May Have in Store

Conclusion

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix E

Appendix F

Appendix G

Index

Guillaume Faye was one of the principal members of the famed French New Right organisation GRECE in the 1970s and '80s. After departing in 1986 due to his disagreement with its strategy, he had a successful career on French television and radio before returning to the stage of political philosophy as a powerful alternative voice with the publication of Archeofuturism. Since then he has continued to challenge the status quo within the Right in his writings, earning him both the admiration and disdain of his colleagues. Arktos has also published English translations of his books Archeofuturism (2010), Why We Fight (2011), and The Convergence of Catastrophes (2012).

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Nouvelle Droite, Synergies européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : sexualité, nouvelle droite, guillaume faye, livre, synergies européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Theodore Lothrop Stoddard

Remembering Theodore Lothrop Stoddard (29 June 1883 - 1 May 1950)

Alex Kurtagic

Ex: http://www.wermodandwermod.com

American historian, journalist, anthropologist, and eugenicist Theodore Lothrop Stoddard was born 131 years ago today. A popular author and journalist until World War II, he was the author of 18 books, most published by a prestigious New York Publisher, Charles Scribner, including, The French Revolution in San Domingo (1914) and The Revolt Against Civilization (1922), of which we published new, annotated editions in 2011.

Stoddard was the archetypical product of ivy-league education in the old United States. He graduated magna cum laude from Harvard University, studied law at Boston University, and obtained a PhD in history from Harvard University, later published as the aforementioned book on San Domingo (Haiti).

Stoddard was the archetypical product of ivy-league education in the old United States. He graduated magna cum laude from Harvard University, studied law at Boston University, and obtained a PhD in history from Harvard University, later published as the aforementioned book on San Domingo (Haiti).

Stoddard was closely associated with Madison Grant's circle of eugenicists and immigration restrictionists during the early part of the 20th century. His work, like that of his colleagues, is controversial today, and books like The Rising Tide of Colour (1920) set forth theses which would be rejected out of hand by present-day policy makers, even though said theses, if at times expressed in a language we would no longer use, have proven broadly correct, with the collapse of the European empires, the demographic trends of the past fifty years in Europe and North America due to mass immigration, the rise of Japan, and the rise of Islam as a threat to the West due to regious fanaticism. He also predicted a second world war and a war between Japan and the United States. Indeed, in his day, Stoddard's influence was significant, to the point of being alluded to in F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby. As is typical of American writers, then and now, and from all sides of the American political spectrum, Stoddard was accutely focused on human races, their characteristics, their relative status, and the conflicts of interests arising between them. As a representative of the old WASP establishment in his country, he was also preoccupied its continuity.

But, while socially conservative, he was in every other sense a progressive liberal, strange as that may seem today: for him, eugenics was about improving the efficiency of human society—an aspiration well in keeping with the ideals of the Progressive Age in America, which was all about efficiency, wholesomeness, and purification (something not unrelated to Protestant ideals), and well in keeping with today's progressives, even if their approach is very different. Indeed, eugenics at this time (which was a generation or more before it fell into disrepute) was seen by its proponents as humane, and American writers made their case in terms of 'the right to be well born', and so forth. Today, this seems inconceivable, but let us think about this for a moment: is not pre-natal screening, and the option to abort a defective fetus, in effect congenial with eugenics, even if restricted to the welfare of individuals? And, given what we now know about epigenetics, would not efforts to improve the overall health of the population also congenial with eugenics? In future, it is likely parents will have the option to eliminate, initially by pre-natal prevention and later by means of therapy, congenital diseases and deformity through gene deactivation, replacement, or correction. While the cattle-breeding methods of the early eugenicists seem shocking to us—and it must be said, these methods were degrading, in that humans were treated like animals or livestock—so were some of the methods used in early medicine, before better ways were found to deal with injury and disease. Today's surgical methods may in future seem like butchery.

But, while socially conservative, he was in every other sense a progressive liberal, strange as that may seem today: for him, eugenics was about improving the efficiency of human society—an aspiration well in keeping with the ideals of the Progressive Age in America, which was all about efficiency, wholesomeness, and purification (something not unrelated to Protestant ideals), and well in keeping with today's progressives, even if their approach is very different. Indeed, eugenics at this time (which was a generation or more before it fell into disrepute) was seen by its proponents as humane, and American writers made their case in terms of 'the right to be well born', and so forth. Today, this seems inconceivable, but let us think about this for a moment: is not pre-natal screening, and the option to abort a defective fetus, in effect congenial with eugenics, even if restricted to the welfare of individuals? And, given what we now know about epigenetics, would not efforts to improve the overall health of the population also congenial with eugenics? In future, it is likely parents will have the option to eliminate, initially by pre-natal prevention and later by means of therapy, congenital diseases and deformity through gene deactivation, replacement, or correction. While the cattle-breeding methods of the early eugenicists seem shocking to us—and it must be said, these methods were degrading, in that humans were treated like animals or livestock—so were some of the methods used in early medicine, before better ways were found to deal with injury and disease. Today's surgical methods may in future seem like butchery.

The change in attitudes towards eugenics, and the scientific progress that has taken place since it was in vogue, has obscured the fact that its proponents were progressives. They truly wanted a better world, a more peaceful and civilised world. And in Stoddard's case this is even reflected in his analysis of foreign affairs. As a pacifist, for example, he was against intense nationalisms and called for fairer policy towards European colonial subjects. He had expertise in Islam and on affairs in the Islamic world, and was, for a time, a Eastern correspondent. In his writing he proved sympathetic towards the concerns of the peoples of these regions.

Unfortunately for Stoddard, his investigation of conditions in Germany in the Winter of 1939 - 194o, which resulted in the book Into the Darkness: Nazi Germany Today, proved disastrous for his career. As a journalistic exercise, it made perfect sense: it was topical and controversial. In the heat of the war, however, his theories came to be seen as too closely aligned with those of the National Socialists. By the time he died in 1950, his passing went unnoticed.

Unfortunately for Stoddard, his investigation of conditions in Germany in the Winter of 1939 - 194o, which resulted in the book Into the Darkness: Nazi Germany Today, proved disastrous for his career. As a journalistic exercise, it made perfect sense: it was topical and controversial. In the heat of the war, however, his theories came to be seen as too closely aligned with those of the National Socialists. By the time he died in 1950, his passing went unnoticed.

I am told that Stoddard wrote an autobiography, which has never been published. Rumour has it that efforts have been made to get ahold of the manuscript, but that his son has consistently denied access to it. This is pity no matter the reasons, because such an autobiography is of historical interest, and could yield new insights into the time period and the individuals in Stoddard's circle, which had links to the highest levels of the American political establishment.

Bibliography:

The French Revolution in San Domingo, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914.

Present-day Europe, its National States of Mind, The Century Co., 1917.

Stakes of the War, with Glenn Frank, The Century Co., 1918.[20]

The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1921 [1st Pub. 1920]. ISBN 4-87187-849-X

The New World of Islam, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1922 [1st Pub. 1921].

The Revolt Against Civilization: The Menace of the Under Man, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1922.

Racial Realities in Europe, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1924.

Social Classes in Post-War Europe. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1925.

Scientific Humanism. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1926.

Re-forging America: The Story of Our Nationhood. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1927.

The Story of Youth. New York: Cosmopolitan Book Corporation, 1928.

Luck, Your Silent Partner. New York: H. Liveright, 1929.

Master of Manhattan, the life of Richard Croker. Londton: Longmans, Green and Co., 1931.

Europe and Our Money, The Macmillan Co., 1932

Lonely America. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran, and Co., 1932.

Clashing Tides of Color. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1935.

A Caravan Tour to Ireland and Canada, World Caravan Guild, 1938.

Into the Darkness: Nazi Germany Today, Duell, Sloan & Pearce, Inc., 1940.

00:05 Publié dans Biographie, Hommages | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : raciologie, lothrop stoddard, hommage, biographie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

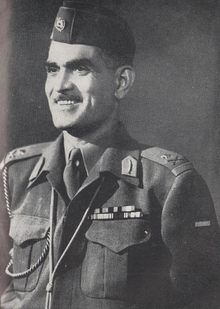

Abd al-Karim Kassem, père de la souveraineté irakienne

Erich Körner-Lakatos :

Abd al-Karim Kassem, père de la souveraineté irakienne

A Bagdad en l’année 1914 nait le fils du marchand de peaux Kassem : son père lui donne le prénom d’Abd al-Karim. On ne connaît pas exactement sa date de naissance car, à l’époque, dans l’Empire ottoman, on ne les relevait qu’une fois par an. Son curriculum, en revanche, est bien connu : à 17 ans, le jeune garçon entre à l’Académie militaire ; en 1941, il entre en formation pour être breveté d’état-major.

A Bagdad en l’année 1914 nait le fils du marchand de peaux Kassem : son père lui donne le prénom d’Abd al-Karim. On ne connaît pas exactement sa date de naissance car, à l’époque, dans l’Empire ottoman, on ne les relevait qu’une fois par an. Son curriculum, en revanche, est bien connu : à 17 ans, le jeune garçon entre à l’Académie militaire ; en 1941, il entre en formation pour être breveté d’état-major.

Dans l’armée irakienne, il y a des remous : les cercles patriotiques estiment que l’Irak doit se ranger du côté de l’Axe Rome-Berlin pour abattre le joug que les Anglais font peser sur le pays. Dans la nuit du 2 avril 1941, les officiers nationalistes se soulèvent. Parmi eux, un jeune major, Abd al-Karim Kassem. La réaction des Britanniques ne se fait pas attendre. Dès le 17 avril, des unités venues d’Inde débarquant à Bassorah, au total 20.000 hommes. Les Irakiens répliquent : leur 3ème Division encercle le 30 avril la base britannique d’Habbaniya, située à l’ouest de Bagdad.

Une unité de l’armée de l’air allemande, l’Haifisch-Geschwader (l’escadron du requin) décolle d’Athyènes, forte de neuf Messerschmitt 110, et met le cap sur l’Irak, flanquée de quelques bombardiers Heinkel 111. A partir de l’aérodrome de Mossoul, les Me110 amorcent leurs missions, abattent quatre appareils ennemis et en détruisent autant au sol. L’aide italienne est plutôt symbolique. Des appareils de transport apportent 18 tonnes d’armes et de munitions. Ils sont accompagnés d’une douzaine de chasseurs Fiat CR-42 qui, après quelques missions, retournent à leur base de Rhodes. En quelques courtes semaines, les Anglais matent l’insurrection irakienne.

En février 1958, la Jordanie et l’Irak constitue la « Fédération arabe », qui doit disposer d’une armée commune, en réponse à la constitution de la RAU (République Arabe Unie), avec l’Egypte et la Syrie. Mais cette dernière quittera la RAU dès 1961 parce que Nasser a confié tous les postes importants à des Egyptiens, ne parvenant pas, à cause de cette maladresse, à effacer le souvenir d’une rivalité immémoriale, celle des diadoques qui se sont jadis partagé l’Empire d’Alexandre : l’Egypte aux Ptolémée de la vallée du Nil, la Syrie aux Séleucides.

Dans la cadre de la « Fédération arabe » irako-jordanienne, le Roi d’Irak ordonne en juillet de déplacer des unités irakiennes sur le Jourdain. C’est l’initiative qui permet de concrétiser un coup d’Etat préparé depuis longtemps à l’instigation d’Abd al-Karim, devenu général et commandant d’une brigade d’infanterie.

Le coup d’Etat du 14 juillet 1958 réussit. Le Roi Fayçal II est tué. Kassem proclame la république, se nomme lui-même premier ministre et ministre de la défense nationale. La nouvelle république irakienne dénonce les accords instituant la « Fédération arabe » avec la Jordanie et signe un traité d’assistance avec la RAU de Nasser.

Le coup d’Etat du 14 juillet 1958 réussit. Le Roi Fayçal II est tué. Kassem proclame la république, se nomme lui-même premier ministre et ministre de la défense nationale. La nouvelle république irakienne dénonce les accords instituant la « Fédération arabe » avec la Jordanie et signe un traité d’assistance avec la RAU de Nasser.

Kassem fait proclamer ensuite une loi de réforme agraire qui limite la grande propriété terrienne. Au bout de neuf mois de consolidation du nouveau régime, Kassem ose un pas en avant décisif : il déclare le 24 mars 1959 que l’Irak rejette le « Traité de Bagdad » qui avait institué un pacte militaire pro-occidental (avec la Turquie, l’Iran et le Pakistan). Les unités britanniques sont alors contraintes de quitter l’Irak. La population se réjouit que l’objectif tant recherché soit enfin atteint : l’Irak est devenu un Etat pleinement souverain.

L’Egypte nassérienne comptait beaucoup d’amis en Irak, où les cercles panarabes souhaitaient voir l’Irak faire partie de la RAU. Mais Kassem ne veut pas remplacer les maîtres de Londres par de nouveaux maîtres venus d’Egypte. Ses adversaires panarabes s’avèreront toutefois les plus forts.

A cinq heures du matin, le 8 février 1963, des appareils Mig survolent avec vacarme et en rase-mottes le centre de Bagdad, criblent la résidence de Kassem de missiles. Les chars manoeuvrent dans les rues. La garde présidentielle, composée de 600 parachutistes, livre un combat acharné contre les putschistes. En vain. Abd al-Karim Kassem est tué le lendemain d’une rafale de mitraillette.

Erich Körner-Lakatos.

(article paru dans « zur Zeit », Vienne, n°45/2014 ; http://www.zurzeit.at ).

00:05 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : abd al-karim kassem, abd al-karim qasim, irak, histoire, monde arabe, monde arabo-musulman, moyen orient, nationalisme arabe |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 31 décembre 2014

La Chine face au dollar

La Chine face au dollar

Le projet, dont la gestion est confiée à HKND pour une centaine d'années, prévoit également la construction de deux ports, d'un aéroport, d'un complexe touristique, d'un oléoduc et d'une voie ferroviaire qui relierait elle aussi les deux océans...1)

Sans faire officiellement partie du Brics, le Nicaragua est en bons termes avec ses membres, notamment la Chine, le Venezuela, le Brésil et la Russie. La participation, directe ou indirecte (via Hong-Kong) de la Chine au financement est généralement considérée comme une première concrétisation des intentions affichées lors des derniers sommets de cet organisme visant à la mise en oeuvre de grands projets de développement et d'infrastructures communs. Cependant l'Etat vénézuélien annonce conserver une part majoritaire dans le financement du projet.

On peut s'interroger cependant sur les ressources dont l'Etat disposerait en propre pour ce faire. Clairement, la participation chinoise s'inscrit dans les nombreux programmes dans lesquels la Chine investit en Amérique centrale et latine. L'objectif est tout autant politique qu'économique. Il s'agit de disputer aux Etats-Unis le monopole qu'ils se sont assuré depuis deux siècles, en application de la doctrine de Monroe, dans cette partie du monde. Dans l'immédiat, Washington n'aura guère de moyens politiques pour réagir, sauf à provoquer un changement de régime à la suite d'un coup d'état qu'il aurait organisé.

Cependant le projet de canal suscite de nombreuses oppositions: d'abord parce que le tracé du canal passe par la plus grande réserve d'eau douce d'Amérique latine, le lac Cocibolca. Ensuite parce qu'il conduirait à déplacer près de 30.000 paysans et peuples locaux qui vivent sur les terres où il sera percé. Ces craintes pour l'environnement et la population sont parfaitement fondées. Mais elles sont relayées par divers ONG d'obédience américaine, ce qui leur enlève une part de crédibilité. Les entrepreneurs américains redoutent en effet l'arrivée de nombreuses entreprises chinoises dans une zone qu'ils considéraient jusque-là comme une chasse gardée. Le Nicaragua et la Chine n'ont aucune raison de continuer à leur concéder ce monopole.

Au delà de toutes considérations géopolitiques, les environnementalistes réalistes savent que de toutes façons, dans le monde actuel soumis à des compétitions plus vives que jamais entre pouvoirs politiques, économiques, financiers, ce canal se fera, quelles que soient les destructions imposées à la nature et aux population. Il s'agira d'une destruction de plus s'ajoutant à celles s'étendant sur toute la planète, en Amazonie, en Afrique, au Canada, dans les régions côtières maritimes censées recéler du pétrole. Les perspectives de désastres globaux en résultant ont été souvent évoquées, sur le climat, la biodiversité, les équilibres géologiques. Inutile d'en reprendre la liste ici. Mais on peut être quasi certain que ces perspectives se réaliseront d'ici 20 à 50 ans.

Les investissements chinois dans le monde.

Concernant la montée en puissance de la Chine, il faut bien voir que ce projet de canal ne sera qu'un petit élément s'ajoutant aux investissements en cours et prévus le long du vaste programme chinois dit de la Nouvelle Route de la Soie. Un article du journaliste brésilien Pepe Escobar vient d'en faire le résumé. Certes l'auteur est complètement engagé en soutien des efforts du BRICS à l'assaut des positions traditionnelles détenues par les Etats-Unis et leurs alliés européens. Mais on peut retenir les éléments fournis par l'article comme indicatifs d'une tendance incontestable. L'auteur y reprend l'argument chinois selon lequel les investissements de l'Empire du Milieu seront du type gagnant-gagnant, tant pour la Chine que pour les pays traversés. 2)

Encore faudrait-il que ces derniers aient les ressources nécessaires pour investir. Aujourd'hui, comme la Banque centrale européenne, sous une pression principalement américaine, refuse aux Etats de le faire, et comme les industriels européens se voit empêcher d'accompagner les investissements chinois et russes, du fait de bilans fortement déficitaires, la Nouvelle Route de la Soie risque de se transformer en une prise en main accrue des économies européennes par la concurrence chinoise. Les résultats en seraient désastreux pour ce qui reste d'autonomie de l'Europe, déjà enfermée dans le statut quasi-colonial imposé par Washington.

D'où viennent les capacités d'investissement de la Chine ?

La Chine détient près de 1 200 milliards de dollars de bons du Trésor américain. En effet, ces dernières années, grâce notamment à des salaires bas, elle a pu beaucoup exporter sur le marché international en dollars, alors que sa population achetait peu. Elle a donc accumulé des excédents commerciaux. Cette situation change un peu en ce moment, du fait d'une augmentation de la consommation intérieure et de la concurrence sur les marchés extérieurs de pays asiatiques à coûts salariaux encore plus bas. Mais elle reste une tendance forte de l'économie chinoise. Que faisait-elle ces dernières années de ses économies? Elle les prêtait massivement aux Etats-Unis en achetant des bons du trésor américain. Aujourd'hui ces réserves en dollars, tant qu'elles dureront, lui permettront de financer des investissements stratégiques dans le monde entier

Mais d'où viennent les capacités d'investissement des Etats-Unis?

Dans le même temps en effet que la Chine économisait, les Etats-Unis dépensaient largement au dessus de leurs revenus, dans le cadre notamment des opérations militaires et interventions extérieures. Pour couvrir ces dépenses, la Banque fédérale américaine (Fed) émettait sur le marché international des sommes largement supérieures, sous forme de bons du trésor (emprunts d'Etat). La Fed s'en est servi pour prêter des sommes considérables aux principales banques américaines, Morgan Stanley, City Group. Merril Lynch, Bank of America Corporation, etc. Les dettes de ces banques auprès de la Fed atteignent aujourd'hui plus de 10.000 milliards de dollars. Les banques disposent certes en contrepartie de milliards de dollars d'actif, mais insuffisamment pour couvrir leur dette auprès de la Fed en cas de nouvelle crise financière.

Ces actifs eux-mêmes ne sont évidemment pas sans valeur. Ils correspondent à des investissements financés dans l'économie réelle par les banques. Mais en cas de crise boursière, ils perdent une grande partie de leur valeur marchande. Les grandes banques se trouvent donc en situation de fragilité. Lors des crises précédentes, elles se sont tournées vers la Fed pour être secourues. La Fed a fait face à la demande en empruntant à l'extérieur, notamment en vendant des bons du trésor. Mais ceci n'a pas suffit pour rétablir les comptes extérieurs de l'Amérique, en ramenant la dette extérieure à des niveaux supportables. Bien que le dollar soit resté dominant sur les marchés financiers, du fait que les investisseurs internationaux manifestaient une grande confiance à l'égard de l'Amérique, il n'était pas possible d'espérer qu'en cas d'augmentation excessive de la dette il ne se dévalue pas, mettant en péril les banques mais aussi les préteurs extérieurs ayant acheté des bons du trésor américains.

Ce scénario catastrophe est celui qui menace tous les Etats, lorsqu'ils accumulent une dette excessive. Mais, du fait de la suprématie mondiale du pouvoir américain, celui-ci a pu jusqu'ici s'affranchir de cette obligation d'équilibre. La Fed a fait fonctionner la planche à billet, si l'on peut dire, dans le cadre des opérations dites de quantitative easing ou assouplissement quantitatif qui se sont succédées ces dernières années. Dans le cadre de cette politique, la Banque Centrale se met à acheter des bons du trésor (ce qui revient à prêter à l'État) ainsi que d'autres titres financiers . Elle met donc de l'argent en circulation dans l'économie . Ceci augmente les réserves du secteur bancaire, lui permettant en cas de crise et donc de manque de liquidités des banques, à accorder à nouveau des prêts. Lors de la crise dite des subprimes, les banques n'avaient pas pu le faire par manque de réserve.

Et l'Europe ? Elle est ligotée.

Il s'agit d'un avantage exorbitant du droit commun dont les Etats-Unis se sont attribué le privilège du fait de leur position dominante. Ni la banque de Russie ni celle de Pékin ne peuvent le faire. Quant à la BCE, elle est autorisée depuis le 18 septembre à consentir des prêts aux banques de la zone euro, dans le cadre d'opérations dite « targeted long-term refinancing operations », ou TLTRO. Ceci devrait inciter les banques à augmenter leurs volumes de prêts aux entreprises., face à la crise de croissance affectant l'Europe. Les sommes considérées sont cependant faibles au regard de celles mentionnées plus haut, quelques centaines de milliards d'euros sur plusieurs années.

De plus et surtout, la BCE n'a pas été autorisée à prêter aux Etats, de peur que ceux-ci ne cherchent plus à réduire leur dette. Le but est louable, en ce qui concerne les dépenses de fonctionnement. Mais il est extrêmement paralysant dans le domaine des investissements productifs publics ou aidés par des fonds publics. Ni les entreprises ni les Etats ne peuvent ainsi procéder à des investissements de long terme productifs. Au plan international, seuls les Etats soutenus par leurs banques centrales peuvent le faire, en Chine, en Russie, mais également aux Etats-Unis.

Que vont faire les Etats-Unis face à la Chine ?

Revenons aux projets chinois visant à investir l'équivalent de trillions de dollars actuels tout au long de la Nouvelle Route de la soie, évoquée ci-dessus. Dans un premier temps, la Chine n'aura pas de difficultés à les financer, soit en vendant ses réserves en dollars, soit le cas échéant en créant des yuans dans le cadre de procédures d'assouplissement quantitatifs. La position progressivement dominante de la Chine, désormais considérée comme la première puissance économique du monde, lui permettra de faire accepter ces yuans au sein du Brics, comme aussi par les Etats européens. Quant au dollar, il perdra une partie de sa valeur et la Fed ne pourra pas continuer à créer aussi facilement du dollar dans le cadre d'assouplissement quantitatifs, car cette création diminuerait encore la valeur de sa monnaie. Ceci a fortiori si la Chine, comme elle aurait du le faire depuis longtemps, cessait d'acheter des bons du trésor américain.

Ces perspectives incitent de plus en plus d'experts à prévoir que, face à la Chine, l'Amérique sera obligée de renoncer à laisser le dollar fluctuer. Ce serait assez vite la fin du dollar-roi. Des prévisions plus pessimistes font valoir que ceci ne suffisant pas, l'Amérique sera conduite à généraliser encore davantage de politiques d'agression militaire. La Chine pourrait ainsi en être à son tour victime.

Notes

1) Cf http://www.pancanal.com/esp/plan/documentos/canal-de-nicaragua/canal-x-nicaragua.pdf

2) Pablo Escobar Go west young Han http://www.atimes.com/atimes/China/CHIN-01-171214.html

Traduction française http://www.vineyardsaker.fr/2014/12/23/loeil-itinerant-vers-louest-jeune-han/

00:10 Publié dans Actualité, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : politique internationale, géopolitique, devises, dollar, yuan, chine, asie, affaires asiatiques, états-unis, guerre économique, économie, canal du nicaragua, nicaragua, amérique centrale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

L’Iran, il y a cinquante ans

Erich Körner-Lakatos :

L’Iran, il y a cinquante ans

Le 5 octobre 1964, six chefs de tribu sont exécutés dans la ville iranienne de Shiraz parce qu’ils ont saboté la réforme agraire de l’Empereur Mohammed Reza Pahlevi qui, à partir du 15 septembre 1965 portera le titre d’Aryamehr, de « Soleil des Aryens ». Cette réforme agraire, appelée « révolution blanche », consiste à déposséder largement les latifundistes iraniens qui, dorénavant, ne pourront plus considérer comme leur plus d’un seul village. Les possessions féodales seront redistribuées aux paysans qui travaillent véritablement la terre. Le processus enclenché par la « révolution blanche » fait qu’à la fin de l’été 1964, 9570 villages ont été redistribués à 333.186 familles paysannes, ce qui équivaut à une population de 1.665.930 âmes. Le Shah a ainsi éliminé la caste entière des latifundistes. C’est là un événement qui laisse tous les penseurs marxistes perplexes qui véhiculent l’idée (fausse) que les grands propriétaires exploiteurs étaient le soutien de la monarchie iranienne. Le Shah de la dynastie Pahlevi était très populaire auprès du petit paysannat. Les mollahs chiites partisans de Khomeini, eux, haïssent le monarque, parce que leur influence est liée à celle des latifundistes évincés. Khomeini présentera la note au régime monarchique en 1979 et chassera le Shah et sa famille. Un an plus tard, le Roi des rois s’éteint en exil.

(article paru dans « zur Zeit », Vienne, n°45/2014 ; http://www.zurzeit.at ).

00:05 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : années 60, histoire, iran, shah d'iran, moyen orient |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

2200 architectes et ingénieurs détruisent le rapport « officiel » sur le 11 septembre 2001

Plus de 2200 architectes et ingénieurs détruisent le rapport « officiel » de la Commission sur le 11 septembre 2001

Le 11 septembre 2001 est devenu un assemblage de mots plus ou moins confus et l'un des sujets les plus populaires de cette dernière décennie, à la fois sur et hors internet. Un sujet qui est devenu si populaire et qui a transformé tellement de gens que les sondages indiquent que plus de 50% de gens ne croient pas à la version officielle diffusée par le gouvernement américain concernant le « rapport de la Commission du 11 septembre 2001 ».

Pendant longtemps, les gens ont été ridiculisés pour avoir remis en cause la soi-disant version officielle, ils ont été catalogués comme théoriciens du complot, anti-américains, fous et on leur attribuait des noms péjoratifs. Mais est-il sensé de mettre ces personnes dans de telles catégories compte tenu de tous les éléments de preuve qui existent pour indiquer que l'histoire officielle n'est pas vraie ? Il ne s'agit pas de théories de grande envergure qu'on peut parfois trouver sur des sites Internet, mais de preuves scientifiques solides réelles.

Enfin quelques médias de grandes distribution

Pendant des années, personne dans les médias de grande distribution n'aurait osé toucher à l'histoire de « la vérité du 11 septembre 2001 » et présenter les faits qu'ils ont pu faire valoir. Peut-être qu'ils ont reçu l'ordre de ne pas le faire étant donné que c'était un sujet délicat. Peut-être qu'ils n'ont pas senti qu'il y avait une validité ou simplement estimaient qu'il n'y avait pas de « retour » sur les faits qui indiquent que l'histoire officielle est obsolète.

Quoi qu'il en soit, nous voyons à présent les nouvelles des médias de grande distribution comme un sujet qui est enfin exposé, et cela pourrait tout changer dans notre monde. Beaucoup ont déjà un pressentiment sur la vérité du 11 septembre 2001, mais si cela devenait de notoriété publique cela changerait la perception des gens sur la guerre, le terrorisme, les gouvernements et les médias de grande distribution.

Lors d'une interview sur C-SPAN, le fondateur Richard Gage des ingénieurs et architectes du 11 septembre 2001 Truth parle de l'effondrement irréfutable contrôlé du bâtiment 7. Ce que Richard présente est de la science simple et des évaluations rigoureuses.

« Richard Gage, AIA, est un architecte qui réside à San Francisco Bay Area, il est membre de l'American Institute of Architects, et le fondateur et PDG de Architects & Engineers for 9/11 Truth ( AE911Truth.org ).

Une organisation éducative, 501(c) 3, qui représente plus de 2200 architectes et ingénieurs agréés et diplômés qui ont signé une pétition appelant à une nouvelle enquête indépendante, avec le pouvoir d'assignation complète, concernant la destruction des Twin Towers et du World Trade Center Building 7 le 11 septembre 2001. Plus de 17 000 signataires parmi lesquels figurent de nombreux scientifiques, avocats, des citoyens responsables formés aux États-Unis et à l'étranger et autres. Ils citent des preuves accablantes d'une démolition explosive contrôlée. »

Plusieurs experts évoquent une démolition contrôlée

La vidéo ci-dessous est un extrait de 15 minutes du documentaire AE911Truth, qui résoud le mystère du WTC 7. Plusieurs experts à travers le monde remettent en question l'histoire officielle du World Trade Center 7.

Architects & Engineers - Solving the Mystery of WTC 7 - AE911Truth.org

Conclusion

Il est temps de s'interroger sur le monde dans lequel nous vivons.

Si la vérité à propos du 9/11 devient enfin une connaissance commune, cela pourrait être la porte pour un changement radical mais extrêmement positif dans notre monde. Je pense que nous sommes sur le point de connaître la vérité sur le 11 septembre.

- Source : Sandra Véringa

00:05 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, états-unis, 11 septembre 2001, new york |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

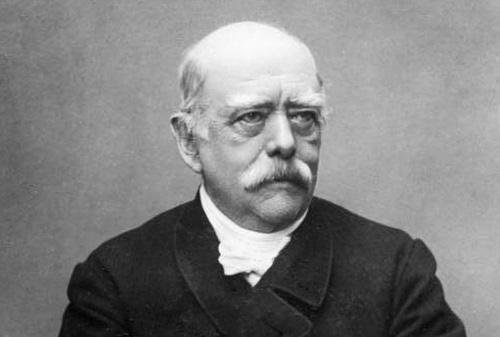

Otto von Bismarck’s Epistle to Angela Merkel

Otto von Bismarck’s Epistle to Angela Merkel

|

Ex: http://www.strategic-culture.org |

|

…Angela, you know, I have always been against ladies’ presence in public affairs and I have not changed my viewpoint so far. Twice I had luck in my life. Firstly, I used to live in the days when ladies were absolutely not allowed to German’s politics. Secondly, I was born on the April Fools’ Day to become a diplomat.

So, Frau Bundeskanzlerin, I have been watching you rule the country from my family vault and now my patience is lost. You have to listen to what I’ll tell you from my estate in Friedrichsruh. It’s a pity you have never come here to visit my grave and ask my advice. Looks I did right ordering grenadiers to give Poles a rough ride and have no mercy because hardly anybody else in Europe deserved thrashing more than them. Yes, you got it right, I mean your grandfather, a Pole by origin. He inherited the national traits of his tribe and made you inherit them too. Now I’d like to make you remember the rules I introduced for German diplomats century and a half ago. Breaching them boded trouble for the nation. This is the first rule, Angela: «Stupidity is a gift of God that should not be used». To put it bluntly, a stateswoman should not be more stupid than her fellow citizens. The most serious form of stupidity is to believe that you are smarter than them. Just look around and answer the question – how many Germans support your alliance with Anglo-Saxons? How many Germans approve your attacks on Russia? Are you sure you see the difference between a big political game and a woman’s intrigue? Let me remind you the second rule of German politics so that you would not mix these things up: «The only sound basis for a large state is its egoism and not romanticism». Where is the state egoism in your policy? Is it your commitment to closer relations with the US President? It’s a hope against hope. Whatever you sacrifice to please Obama, it will bring bad luck to Germans. Americans have a reason to stir up trouble in Europe, why help them? Do not forget that the third rule of German politics says: «Whatever is at rest should not be set in motion. A government must not waver once it has chosen its course. It must not look to the left or right but go forward». Germany has once chosen Ostpolitik and that was the best choice. But after the collapse of the Soviet Union you fell victim to greed. You wanted Russia to be pushed out further and further. Now you and Americans are turning Europe into a military camp. Germany put on soldier’s boots and stepped on the Serbian ground. You forgot what I said: «The whole of the Balkans is not worth the bones of a single Pomeranian grenadier», «One day the great European War will come out of some damned foolish thing in the Balkans». You spend billions of Euros on Kosovo. The first thing I would do being in your shoes is to hang those Albanian murderers that you made come to power. There is nothing to expect from them but low tricks and plundering. Finally, you messed with the Russians having forgotten the main secret of German politics: «Make a good treaty with Russia». You should read my memoirs and learn by heart what I said many years ago: «Never fight against Russians. Your every cunning will be responded by their unpredictable stupidity», «This inviolable state of the Russian nation is strong in its climate, its spaces and limitations of the needs». You should also take into account, Angela, that a Russian harnesses his horse slowly but drives fast. Putin’s patience has its limits. If he starts to act you’ll be in a deep trouble. You collude with Anglo-Saxons. Nothing could be more stupid. These guys turn a blind eye on the fact that the Yeltsin’s Russia is gone. A new Russia has appeared headed by Putin. It’s not weak and pliant any more. Today’s Russia is strong again and ready to stand up for itself. You should realize who you deal with. Read once again what I wrote: «Do not expect that once taking advantage of Russia's weakness, you will receive dividends forever. Russians always come for their money. And when they come – do not rely on agreement signed by you, you are supposed to justify. They are not worth the paper it is written. Therefore, with the Russian is to play fair or do not play». Angela, perhaps you opted to provoke Russians into getting mired in Ukraine because you remember my words that in order to deprive Russia of its power, you need to separate it from Ukraine? Come on, you cannot formulate a concrete goal if it is based on a mere speculation! Many European politicians say that without Bavaria Germany will become a weedy castrate, but nobody is going to try it, no matter how many idiots are dreaming of secession from Germany there. You follow Anglo-Saxons who don’t think about depriving Russia of its imperial status. They want to destroy it. Do you really believe Germany would benefit if there were no Russia in Europe? Do you really believe this baloney about European values and common interests? Remember I was rebuked for keeping away from forming coalitions. A French newspaper wrote that I suffered from nightmares because of prospects for Germany to become part of a coalition. True, I was afraid of coalitions because I could not sleep at nights fearful that my partners steal my possessions. I was also accused of creating a secret fund to bribe the press and calling journalists «moral poisoners of wells». You know what I think about them. «Journalist is a person who has mistaken his calling». They persecute people because of their complex of inferiority. I bribed them to make German wells safe for drinking. These guys have already poisoned German minds, as well as yours, I’m afraid. Finally, I’ll say the following. No need to take seriously those diplomatic dumbbells trying to reshape the world so that it would look like a Christmas tree in a Prussian military barrack. Believe me, the world doesn’t want to be reshaped, and there is no need to do it. Politics is the art of the possible, the attainable - the art of the next best no matter how abhorrent it may seem to be. In Russia I learned the word «nichego!» («it is nothing») used when they face really hard times. This word connotes with great wisdom and patience - the qualities you should acquire, Frau Federal Chancellor, and that would be my last advice to you. Sincerely,

Prince Otto von Bismarck

|

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, europe, allemagne, angela merkel, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Study of Sombart – Varsanyi

Study of Sombart – Varsanyi

A Study of Werner Sombart’s Writings by Nicholas A. Varsanyi (PDF – 8.4 MB):

A Study of Werner Sombart’s Writings

Varsanyi, Nicholas A. A Study of Werner Sombart’s Writings. Ph.D. Thesis, Montreal, McGill University, 1963. File originally retrieved from: <http://digitool.library.mcgill.ca/R/?func=dbin-jump-full&object_id=115298&local_base=GEN01-MCG02 >.

Ex: http://neweuropeanconservative.wordpress.com

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Révolution conservatrice, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : werner sombart, socialisme, socialisme allemand, révolution conservatrice, allemagne, histoire, théorie politique, philosophie, philosophie politique, sciences politiques, politologie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Marche Sainte-Geneviève

00:01 Publié dans Evénement | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : événement, paris, france |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 30 décembre 2014

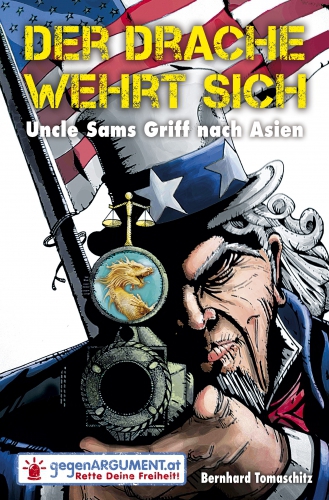

Uncle Sams Griff nach Asien

Bernhard Tomaschitz

Der Drache wehrt sich

Uncle Sams Griff nach Asien

200 Seiten,

kartoniert, 16,00 euro

Kurztext:

In Europa nur wenig bemerkt wird die Tatsache, daß in Zentral- und Südostasien längst ein „Großes Spiel“ der Weltmächte stattfindet. Während sich die USA diese rohstoffreichen und strategisch wichtigen Regionen ihrer Einflußzone zur Schwächung Chinas und Rußlands einverleiben wollen, kontern Moskau und Peking mit der Stärkung der Schanghaier Organisation für Zusammenarbeit und greifen den US-Dollar als Weltleitwährung an. Und die USA tun das, was sie am besten können: Sie entfalten – um angeblich „Freiheit“ und „Demokratie“ zu verbreiten – subversive Tätigkeiten, stiften zu Aufständen an, Verbünden sich mit Islamisten und errichten in Ostasien ein Raketenabwehrsystem, welches angeblich gegen Nordkorea, tatsächlich aber gegen das aufstrebende China gerichtet ist.

Mit profunder Sachkenntnis analysiert Bernhard Tomaschitz die hinter diesem Wettlauf der Mächte stehenden geopolitischen Fragen, zeigt die Mittel und Wege auf, wie die USA sich Zentralasien ihrer Einflußsphäre einverleiben und China eindämmen wollen und welches krakenartige Netzwerk an angeblich „unabhängigen“ Stiftungen dabei zum Einsatz kommt.

Bestellungen:

00:10 Publié dans Actualité, Géopolitique, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, bernhard tomaschitz, actualité, géopolitique, états-unis, asie, affaires asiatiques, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Center Parcs: économie sans conscience n’est que ruine de l’âme

Center Parcs: économie sans conscience n’est que ruine de l’âme

par Claude Bourrinet

Boulevard Voltaire cliquez ici

Hitler, paraît-il, rêvait de transformer la France en jardin. Le libéralisme mondialisé, en apparence moins ambitieux, préfère la métamorphoser en Center Parcs. Le chômage massif n’est pas pour rien dans l’avilissement du peuple français. Non seulement parce que l’être humain, socialisé, a besoin de travailler pour éprouver ses capacités, manifester sa dignité, mais aussi parce que la raréfaction de l’emploi est devenue un argument d’autorité pour imposer ce qui s’apparente de plus en plus à une dégradation de la civilisation, au sens où l’entendait Edgar Morin en 1997. Dans un entretien paru en 2008, il revient sur cette notion : « Il s’agit de solidariser les rapports humains, régénérer les campagnes, ressourcer, convivialiser, moraliser… »

La multiplication des paradis artificiels, pour ainsi dire en bulle, piètres succédanés à la misère économique, sociale et humaine, généralisée par une société sinistre, est-elle en mesure de raviver les campagnes, de créer de la convivialité, de « solidariser » la société ?

Éric Zemmour note, dans Le Suicide français, combien régnait, durant les Trente Glorieuses, tant chez les gaullistes que chez les communistes, une vision héroïque et ascétique du travailleur, pour qui certaines valeurs (le courage, la fidélité, la fierté, l’intelligence du métier) n’étaient pas encore dissoutes par l’hédonisme contemporain, ou tout simplement par l’éradication de l’industrie française.

De fait, le Grand Remplacement a commencé à cette époque, qui connaît l’exode des paysans vers la ville, phénomène civilisationnel dont l’on n’a pas mesuré toute l’importance. C’est tout un art de vivre, d’exister ensemble, de respecter la terre, la nature, les traditions, qui a été anéanti. Depuis, la campagne n’est plus qu’un espace d’exploitation et une nostalgie. De même, la désindustrialisation de notre pays, la destruction de ses grandes réalisations d’après-guerre, sous les coup de la mondialisation, ou du fait de cette pompe aspirante qu’est la délocalisation, ont provoqué sous-emploi ou bien substitution du métier par le « service ». Le prolétariat s’est transformé en masse flexible d’agents commerciaux, de nettoyeurs, de domestiques, de recrutés précaires, de petites mains corvéables, de mendiants à mi-temps. On ne reprochera pas aux habitants de petits villages d’accueillir avec espoir ces Center Parcs (l’emploi sans scrupule du Néerlandais est, en soi, tout un programme). La déréliction a des raisons que la raison doit accepter. « L’homme est un animal qui s’habitue à tout », écrit Dostoïevski dans Souvenirs de la maison des morts.

Mais nous devons bien réfléchir à ce qui est en train de se produire dans notre vieux pays. Il ne s’agit pas seulement du saccage de notre trésor naturel, mais du ravage causé dans l’esprit du peuple français, réduit à n’être plus que le serviteur du tourisme de masse.

00:05 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, center parcs, france |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Éloge du consumérisme de Noël

Éloge du consumérisme de Noël: contre Natacha Polony

Les agapes de Noël sont régulièrement l’occasion de condamnations aussi vertueuses qu’hypocrites sur la débauche de consommation. Elles sont le prétexte à des considérations superficielles contre la ”société de consommation”, le ”libéralisme”, l’ ”argent”, le” capitalisme”, etc. Et cela, souvent au nom d’une vision aussi ignorante du fonctionnement de l’économie que de la ferveur religieuse.

À titre d’exemple, je cite ici deux textes, l’un de l’excellente Natacha Polony, (« Grande braderie de Noël » ), qui, une fois n’est pas coutume, n’est vraiment pas inspirée ; et l’autre, de la romancière Solange Bied-Charreton, ( « A-t-on perdu l’esprit de Noël ? » ) (1) qui s’indigne de la sécularisation de Noël par le consumérisme. Deux analyses aussi emblématiques l’une que l’autre d’un état d’esprit habile à manier les clichés les plus lourdement idéologiques et les plus déconnectés de la réalité.

Critique des idées fausses

Natacha Polony s’est fait un nom dans la défense, souvent talentueuse, des traditions, des enracinements, dans la dénonciation de l’effondrement de l’Éducation nationale ; mais aussi dans la défense de l’agriculture traditionnelle et familiale contre l’agriculture et l’élevage industriels (elle a raison) mais son romantisme terrien a quelque chose de fabriqué, de faux, d’urbain. Tout comme sa critique puritaine des festivités de Noël.

« Ces fêtes de Noël qui sont devenues la mise en scène gargantuesque du règne de la consommation sur nos existences », écrit-elle. L’excès même de la formule l’affaiblit. Nous serions «gavés de biens ». Trop riches en somme, ramollis comme les Romains de la décadence ? Elle fustige avec hypocrisie un « libéralisme » qui serait pire que le communisme (alors que les libéraux n’ont pas voix au chapitre dans ce pays) et aussi « les ardeurs de l’enrichissement personnel », comme s’il s’agissait d’un péché. Alors que la France crève d’assistanat, de fuite des cerveaux et des entrepreneurs, de fiscalisme confiscatoire, de sous-travail, ces intellectuels inconscients se dressent contre le goût de l’enrichissement privé qui est le moteur de la prospérité, de la créativité et du dynamisme d’une nation, comme l’a démontré Schumpeter.

Elle estime, dans une formule pompeuse que « ce qui constitue le phénomène majeur de ce début du XXIe siècle est l’extension du marché à l’ensemble des domaines de l’expérience humaine ». Ah bon ? Dans une société française collectiviste et corporatiste où 57% du PIB échappe au marché pour se reporter sur les redistributions, l’assistanat, les aides et les dépenses publiques ? Où l’emploi marchand ne cesse de reculer au profit de l’emploi fonctionnarisé ou aidé qui frôle les 6 millions d’agents ? Natacha Polony, comme tous les intellectuels parisiens, formule de grands principes globalement fondés sur l’ignorance et l’idéologie. Dans un pays où le collectivisme, le réglementarisme et l’étatisation (même de la Santé) ne cessent de progresser, ce genre de formule laisse pantois. C’est au contraire le rétrécissement du marché qui est la règle dans la société française. Et nos idéologues nous disent, désignant un chat : « observez ce chien ».

Fustigeant le « Divin Marché », elle vilipende la timide Loi Macron comme le symbole d’un libéralisme débridé, alors que c’est un pet de nonne : « le libéralisme de la loi Macron qui porte atteinte à l’indépendance de la France au nom d’une petite logique comptable qui va à l’encontre de l’idée même de République ». Elle fait allusion à la vente aux Chinois d’une partie du capital de l’aéroport de Toulouse-Blagnac, sans comprendre une seconde que la cause de cette vente n’est pas le libéralisme mais… le socialisme fiscal : pour survivre, cette entreprise avait besoin d’apport en capital. Or, les investisseurs français, assommés de taxes et d’impôts, ne peuvent pas suivre. C’est le collectivisme socialiste qui pousse à brader le patrimoine national, pas le libéralisme qui, au contraire, permet la prospérité et les marges nettes des investisseurs nationaux ! Brader le patrimoine national, les ”bijoux de famille” au nom des besoins de financement et d’endettement ? C’est la conséquence perverse du socialisme. C’est lui qui aboutit à la cession patrimoniale par l’État et, paradoxalement, pas le capitalisme libéral !

Natacha Polony, reprenant une sociologie de bazar soixante-huitarde déplore en ces termes fantasmés la ”marchandisation” de nos existences : « tout dans les actions des individus relève de la recherche de rentabilité et de performance ». Hélas, c’est l’inverse ! « La vie individuelle, se lamente-t-elle, se gère comme un budget ». On est sidéré par la déconnection de tels clichés. Nous vivons, au contraire, en France, dans une société où l’idéal de performance, de responsabilité économique individuelle, d’entrepreneuriat, de récompense du mérite est abrogé au profit de l’assistanat et du corporatisme – notamment syndical. Comment Natacha Polony, qui est tout de même très intelligente, peut-elle se méprendre à ce point ? La réponse est claire : l’intellectualisme aveugle et abêtit parce qu’il remplace le bon sens et l’observation par l’idéologie paresseuse. D’origine marxiste, même à droite.

Mais revenons à nos moutons avec cette autre charge contre le consumérisme de Noël, issue de la romancière Solange Bied-Charreton (1) (« A-t-on perdu l’esprit de Noël ? »). Elle aussi se lance dans des considérations de sociologie de comptoir : « Noël est devenu cette grande fête de la matière, de la richesse et de la dépense » Comme si cela empêchait la spiritualité… Donc, vive la pauvreté, le dénuement, le dépouillement, comme idéaux sociaux ? Elle fustige, dans un anti-matérialisme convenu « l’envoûtement affiché pour le luxe, pour les plaisirs du ventre, cette compulsion consommatoire » ; en même temps, elle se moque, dégoûtée, de la débauche « de chocolats industriels, de mauvais champagne, de sapins abattus à la chaine (2), de fourrures synthétiques, de jouets et de bonbons ». Elle, a sans doute les moyens de s’offrir du bon champagne et du chocolat de pâtissier… Bref, le petit peuple serait malvenu de faire des réveillons chaleureux et de s’offrir des cadeaux de Noël ; il ferait mieux de se recueillir et de se coucher tôt.

La romancière poursuit en se scandalisant de cette « profusion délétère », de la « féérie fétichiste de la marchandise », multipliant les formules de la langue de bois gauchisante : « l’histoire de l’Occident des deux derniers siècles est celle de l’avènement du capitalisme comme « fait social total » (Marcel Mauss). L’esprit du Noël capitaliste infuse l’idée selon laquelle le bonheur réside dans la consommation. Rite religieux d’une économie qui ne sait plus quoi faire de sa surproduction ». Âneries économiques ; nullités sociologiques hors-observations ; clichés snobs , généralisations, formules toutes faites, rhétorique qui remplace la réflexion. Relier cela au combat contre les crèches des laïcards (islamophiles par ailleurs) est stupide ; elle confond deux problèmes distincts. On croirait entendre un pasteur calviniste ou un curé janséniste du XVIIe siècle : « l’immortalité est un moindre mal, Dieu existe et châtie. Mais c’est un monde sans Dieu qui désormais entend diffuser cet ”esprit de Noël” ». Degré zéro de l’analyse. Dans un autre article (« Un chant de Noël pour les vaches, pour la terre et pour les hommes ») (3) Natacha Polony réitère son aversion pour « la débauche d’achats et de l’orgie de nourriture ». Elle passera donc le réveillon de Noël à manger quelques dattes et des fèves arrosées d’eau minérale.

Le puritanisme hypocrite

Les clichés contre le marché, le consumérisme, l’argent, qui fédèrent toute la classe intellectuelle française de droite comme de gauche, relèvent d’une puissante hypocrisie. Ils témoignent aussi d’une ignorance profonde du fonctionnement de notre société comme de l’histoire. Le spiritualisme et la ferveur religieuse populaire n’ont jamais été synonymes – sauf chez des minorités monacales ascétiques ou des sectes – d’austérité et de dépouillement, mais, bien au contraire, de profusion festive et conviviale. Prenons le christianisme : si le Christ a chassé les ”marchands du Temple”, c’est parce qu’ils commerçaient dans un lieu inapproprié, mais il n’a jamais condamné les débordantes Noces de Cana. Et que pensent nos nouveaux Cathares de la ville de Lourdes, dont toute la prospérité, commerçante, hôtelière, touristique, dépend du culte marial ? Est-ce une profanation ? Les sommes colossales dépensées par l’Église dans la Chapelle Sixtine ou les cathédrales sont-elles condamnables ?

La vision myope selon laquelle notre société est beaucoup plus mercantile et obsédée par l’argent que les sociétés traditionnelles est totalement fausse. Une preuve éclatante en est fournie par le fait incontournable que, de la plus haute Antiquité jusqu’à la Révolution, la noblesse ne se définissait pas seulement par les qualités militaires mais surtout par la richesse, condition de son acquisition. À Rome, les noblesses équestre et sénatoriale étaient strictement fondées sur la fortune financière et foncière, selon un barème précis. Et de l’Athènes de Périclès jusqu’à la France de Louis Philippe, le vote était censitaire, c’est-à-dire fondé sur la capacité fiscale.

Dans les délires anti-consuméristes de Natacha Polony, on retrouve cette idée de frustrés que Noël n’est pas une fête, que tout ce qui est ”matériel” est mal. Comme si le recueillement était antinomique de la fête ; comme si la spiritualité était antinomique du principe de plaisir. Les marchés de Noël seraient ”impurs”, parce qu’ils inciteraient à la consommation et parce qu’ils seraient des ”marchés” ? On n’est pas très éloigné d’une dérive mentale puritaine partagée par les Talibans et autres djihadistes… Beaucoup plus intelligente, et proche du réel, est la réflexion de l’écrivain Denis Tillinac (Noël envers et contre tout, in Valeurs Actuelles, 18/12/2014) qui associe étroitement la magie religieuse (culturelle et cultuelle à la fois) de la Nativité à la convivialité des agapes des cadeaux et du banquet familial du réveillon.

On ressent un malaise devant ces plaintes sur la ”surconsommation” de Noël. Comment peut-on s’indigner que les commerces fassent du chiffre d’affaire à Noël alors que cela crée des emplois et fournit du travail ? Un éleveur de volailles du Gers ou un ostréiculteur charentais n’apprécieraient certainement pas des propos incitant à ne pas trop ”consommer” pour cette période de fin d’année. Un grand nombre de PME et de TPE – qui portent à bout de bras une économie plombée par le parasitisme fiscal de l’État Providence, font une partie indispensable de leur chiffre d’affaires à Noël – et au premier de l’An. C’est mal ?

Dans toutes ces critiques du matérialisme marchand, on repère évidemment une gigantesque hypocrisie puisqu’elles proviennent d’urbains nantis. Il faut avoir l’esprit hémiplégique, pour penser que le plaisir de consommer, de faire la fête, d’échanger des cadeaux au moment de Noël est contraire à la spiritualité et à la tradition de la Nativité. Fêter Noël sans agapes, c’est absurde. Ces lamentations sur la ”profanation” de Noël par la fête relève d’une incapacité à penser ensemble le sacré et le profane, à envisager une célébration familiale et cultuelle avec ces composants naturels que sont l’abondance et la dépense. Faut-il rejeter aussi les repas de noces ? Et la tradition des cadeaux baptismaux en or et en argent ? Le dépouillement et l’ascèse (dans plusieurs religions) relèvent d’un idéal monacal, d’une exception.

Le marché conçu comme péché

Le grand paradoxe des sociétés marchandes et libérales, non étatistes, non collectivistes, c’est qu’elles sont moins individualistes, moins égoïstes et plus solidaires, plus organiques que les régimes de l’État Providence, « puissance tutélaire » selon Tocqueville, qui substitue aux solidarités familiales et autres l’assistanat public. Voilà une idée à creuser. La mentalité marxiste, qui imprègne sourdement nos élites, est d’ailleurs fondée sur un type d’économie anti-marchande qui reprend subrepticement l’idée du Capital de Marx : en revenir à une société de troc programmé, archaïque et pré-monétaire, mais aussi surplombée par un Big Brother redistributeur et égalisateur. C’est cette utopie qui a fourvoyé et foudroyé l’URSS et le monde communiste. Et dont la tentation est toujours vivante, infectieuse, dans l’État français.

Sociologiquement, – et économiquement – l’idée de dictature du marché et de la consommation ne correspond pas à ce qu’on observe dans la société française. Certes, oui, sur le plan quantitatif, on consomme plus qu’en 1900. Partout dans le monde. Mais – et c’est ce qui importe – la part de la consommation marchande et des revenus marchands dans la société française ne cesse, tendanciellement, de décliner, depuis 40 ans, au profit d’une part de la redistribution et d’autre part du salariat fonctionnarisé. En termes techniques, on assiste donc à une socialisation de la demande par assistanat et à une étatisation de l’offre. Avec, en corrélation, une augmentation du chômage et une stagnation à la baisse du niveau de vie. Ce sont les faits, indépendants des discours idéologiques.