Por Ernesto Milá

Ex: https://rebelioncontraelmundomoderno.wordpress.com

info-Krisis.- Fue en 1992 (o quizás fuera en 1994) cuando conocidos a Alexandr Duguin, el cual nos habló por primera del “cosmismo”. Lo que nos dijo en aquel momento, casi textualmente, fue lo que pudimos leer luego en su libro Rusia y el Misterio de Eurasia, en donde tocaba con cierto detenimiento (pero no exhaustivamente), los rasgos y el papel del cosmismo en la historia reciente de Rusia y del período soviético. Desde aquel momento experimentamos un vivo interés por esta corriente filosófica, sin embargo, la falta de traducción de las obras de su fundador, Fiodorov, eran un obstáculo para poder penetrar en ella. Con el tiempo, Internet ha ido facilitando progresivamente el conocimiento y comprensión de esta doctrina ofreciendo fuentes documentales en distintos idiomas occidentales accesibles. Este trabajo es, pues, en cierto sentido, un trabajo de síntesis en castellano sobre todo lo publicado sobre el cosmismo en Internet, pero es algo más. Es un trabajo crítico y, al mismo tiempo que intenta aportar un elemento decisivo y nuevo: el cosmismo en Occidente. Por que lo sorprendente es que, de manera expontánea, aparentemente sin lazos orgánicos directos, las mismas ideas puestas en circulación por Fiodorov fueron asumidas por personajes y movimientos muy diversos en los países occidentales y, más o menos, en las mismas épocas. Identificar cuáles eran esas corrientes y como se manifestaron supone un ejercicio intelectual curioso no realizado hasta ahora.

Ha dado la casualidad que hemos alternado este trabajo con otro sobre “conspiración – conspiradores – conspiranoicos”, de ahí que nos haya preocupado extraordinariamente un concepto derivado de la “paranoica”, una especie de visión paranoica atenuada de los “enlaces” entre los hechos, lo que se llama en literatura “apofenia”. La apofenia sería el estalecimiento de patrones y conexiones entre sucesos aleatorios que no tienen ninguna vinculación entre sí. No se trataría de una “enfermedad mental”, sino más bien de un patrón de comportamiento provisto de algún rastro de psicosis conspiranoica. Sin embargo, los estudios sobre la apofenia han demostrado que puede aparecer en individuos sanos y cuya mentalidad tiene una carga de creatividad superior a la normal. Hemos procurado huir de cualquier tentación conspiranoica y de caer en esta “apofenia”. Así pues nuestro trabajo ha consistido simplemente en describir el fenómeno cosmista y el movimiento de “los constructores de dios” que apareció en Rusia en el siglo XIX y se insertó como corriente dentro del partido bolchevique (siendo atacada inmisericordemente por Lenin y, desmostrando explícitamente su existencia y peligrosidad para el materialismo dialéctico marxista), y, paralelamente, el desarrollo de ideas extremadamente similares en Occidente y antes las cuales es lícito realizar un paralelismo crítico, aun reconociendo que no existen vínculos orgánicos demostrables entre las ideas nacidas en Rusia y esas mismas ideas nacidas en Occidente (en franjas del ocultismo, en el sector de la New Age, en el pensamiento de Teilhard de Chardín y en el humanismo universalista de la UNESCO). Lo cual es todavía más sorprendente… Huir de la “apofenia”, paradójicament, nos sitúa en un terreno directamente “conspiranoico”.

El huir de la tentación “apofénica” nos sitúa pues en un contexto todavía más sorprendente: si las ideas “cosmitas” en Rusia y el “universalismo” occidental son tan parecidos, pero no existen vínculos orgánicos entre ellas (salvo a través del concepto de noosfera utilizado tanto por Teilhard como por el cosmista Vernadski)… ¿de dónde deriva esa similitud? Pregunta que dejamos en el aire, tras mencionar la doctrina de la “contra iniciación” y de la “anti tradición” que corresponde a la interpretación realizada por René Guénon.

Cabría añadir antes de iniciar nuestro estudio que la atención que ha merecido el cosmismo en Occidente ha sido mínima y, paradójicamente, hasta no hace mucho, solamente los medios marxistas estaban al corriente de su existencia, no tanto por el conocimiento directo de sus textos, como por saber de ella a causa de la crítica que Lenin le formuló en su Materialismo y Empirocriticismo, libro que en los años setenta seguía siendo manual de cabecera de los marxistas españoles…. En los últimos años, medios de la derecha (FAES, en concreto) se han hecho eco de la existencia del cosmismo (véase la publicación FAES correspondiente a abril-junio de este año en la que se publica el artículo El cosmista Stalin y el socialismo del siglo XXI, escrito por Edward Tarnawski, profesor de Ciencia Política de la Universidad de Valencia; el artículo, a pesar de los títulos del autor, contiene, no solamente errores metodológicos, sino de bulto en la valoración de la información y casi podría ser considerado como mera intoxicación).

Cabría añadir antes de iniciar nuestro estudio que la atención que ha merecido el cosmismo en Occidente ha sido mínima y, paradójicamente, hasta no hace mucho, solamente los medios marxistas estaban al corriente de su existencia, no tanto por el conocimiento directo de sus textos, como por saber de ella a causa de la crítica que Lenin le formuló en su Materialismo y Empirocriticismo, libro que en los años setenta seguía siendo manual de cabecera de los marxistas españoles…. En los últimos años, medios de la derecha (FAES, en concreto) se han hecho eco de la existencia del cosmismo (véase la publicación FAES correspondiente a abril-junio de este año en la que se publica el artículo El cosmista Stalin y el socialismo del siglo XXI, escrito por Edward Tarnawski, profesor de Ciencia Política de la Universidad de Valencia; el artículo, a pesar de los títulos del autor, contiene, no solamente errores metodológicos, sino de bulto en la valoración de la información y casi podría ser considerado como mera intoxicación).

Sin embargo, dichos artículos no se intertan en una perspectiva “integradora”, sino que pretendenten “denunciar” al cosmismo como una forma de irracionalismo bolchevique (lo que por otra parte es, pero no sólo es eso, sino que su proyección va mucho más allá de una mera heregía dentro del campo comunista). Por otra parte, el artículo que hemos mencionado de FAES va en la dirección habitual en la derecha liberal occidentalista: establecer vínculos con los EEUU e intentar desvincular y romper cualquier nexo que pudiera existir entre Rusia y Europa.

A nadie que conozca la trayectoria de infokrisis, se le escapa que, por nuestra parte, el eje a construir en el futuro es Madrid – París – Berlín – Moscú y que de su construcción dependerá el orden mundial que sustituya al unilateralismo que hoy agoniza. Sin embargo, consideramos que ni el cosmismo de Rusia, ni el cosmismo de Occidente son puentes que aproximen en lo positivo, sino, más bien, opciones ideológicas que conducen más bien a una misma posición: lo que en Rusia es el “cosmismo”, en Occidente es el “universalismo”. Ambos son, en definitiva, degeneraciones de la perspectiva tradicional y, por tanto, rechazables. Tal es la tesis que vamos a intentar establecer en el presente ensayo.

La Santa Rusia tierra de promisión del bolchevismo y de la tradición

Pocas ideologías han tenido tantas repercusiones como el cosmismo ruso y pocas han sido tan desconocidas e ignoradas como ésta. El racionalismo cartesiano llegó tarde a Rusia y nunca tuvo el impacto que llegó a tener en Occidente a partir del siglo XVII. Y esto explica también el que durante el período soviético pudieran coexistir dos formas antitéticas de racionalidad: la de los materialistas dialécticos y la de los cosmistas. Si el régimen soviético logró imponerse con facilidad en Rusia era porque la sociedad agraria de aquel país estaba mucho más próxima de la tradición que cualquier otro país occidental. Allí el campesino tenía todavía un peso decisivo y opinaba que existe una relación orgánica entre el ser humano y la naturaleza que le rodea. Este simple principio de sabiduría campesina también ha estado presente en Occidente, pero muy debilitado.

El “comunismo”, en el fondo, responde a las tradiciones campesinas de solidaridad y apoyo mutuo que siempre estuvieron más vivas a lo largo del siglo XX en el Este Europeo que en el Oeste y Sur del continente. Incluso podría argumentarse que si la clase obrera europea admitió pronto formas de socialismo como doctrina propia era, precisamente, porque no hacía mucho tiempo que el proletariano tenía un origen campesino. De ahí que el comunismo tenga un doble aspecto: racionalista de un lado, esto es, heredero de la ilustración y el cartesianismo, pero también tradicional y comunitario, producto de la mentalidad campesina.

El comunismo nunca pudo superar estas dos tendencias: la que procedía de la ideología marxista, fría, materialista y economicista, con pretensiones de explicar e interpretar la historia, y aquella otra que tendía apenas a resaltar los vínculos entre los seres humanos, la necesaria solidaridad entre los hombres, sus intereses comunes, y la libertad de la que un campesino que trabaja su tierra es el primero en conocer. Desde este punto de vista, el comunismo nunca superó la tensión entre estos dos conceptos. El primero estuvo presente en las direcciones, desde Marx y Engels hasta Lenin. Sin embargo, el segundo fue lo que galvanizó a las masas, mucho más que las frías teorías y el hiperrracinaismo (que, por lo demás, jamás “funcionó”, como en Lenin que analizando la clase obrera suiza, llega a la conclusión de que será en ese país en donde estallará la primera revolución proletaria, o bien en Castro y el Ché que, aun sin contar con las “condiciones objetivas necesarias” se lanzan a la guerrilla y, contra todo pronóstico, triunfan, demostrando que lo esencial no es la teoría marxista, sino la voluntad de poder, esto es, lo negado por el hiperracionalismo marxista).

Hay algo en todas las sociedades tradicionales que remite a la solidaridad y a la práctica comunitaria, formas de pre-individualismo que consideran a la sociedad como el escenario “común” ideal para el ser humano. Los proletarios de principios del siglo XX, eran campesinos solamente una generación antes y todavía habían sido educados en esos valores, por lo tanto, pudieron entender mejor que nadie –incluso mejor que los propios líderes bolcheviques- los llamamientos a la solidaridad, y al “comunismo”. Y esto explica también por que la segunda gran revolución marxista se produjo en China… y fue protagonizada solamente por campesinos, contraviniendo todas las previsiones marxistas y leninistas.

Por otra parte, no hay que olvidar que tanto en la revolución soviética como en el triunfo del maoísmo en China, ambas sociedades estaban próximas a la “tradición”. La primera gracis a la presencia de la Iglesia Ortodoxa, seguramente la forma más tradicional del cristianismo, próxima a su concepción medieval. La segunda, gracias a la patina con que el confucionismo había cubierto a la sociedad china desde el siglo VI a. de JC. También aquí cabe decir que los dirigentes bolcheviques y maoístas nunca supieron verdaderamente por qué triunfaban en esos países y no fueron capaces de entenderlo, ni luego supieron por qué el régimen se esclerotizó primero y se convirtió en algo frío, dictatorial e inhumano: fue, simplemente, por que se intentó desarraigar a las poblaciones de las concepciones comunitarias tradicionales, emprender una lucha sin perdón contra todo lo que era “tradición”, considerado como un “residuo pequeño burgués”. Cuando ésta desapareció, lo único que quedó fue el individualismo, tan sólo contenido por una estructura tecnoburocrática dictatorial e inmisericorde. Una vez más, el sueño de la razón, produjo monstruos: las fosas de Katyn, el stalinismo, Pol-Pot, el universo concentracionario soviético, Paracuellos del Jarama, etc.

En este sentido, el “cosmismo” se adaptaba perfectamente a la naturaleza del régimen soviético de los primeros tiempos y a esa tensión dialéctica entre racionalidad extrema y tradición. Por eso, no es raro que los cosmistas se movieran bien dentro del partido bolchevique y que el propio Lenin advirtiera en ellos a su peor enemigo interior. Las casi 400 páginas de su Materialismo y Empirocriticismo van dedicadas especialmente a luchar contra esta corriente interior. Sin embargo, la corriente sobrevivió a Lenin y Stalin y sus sucesores debieron recurrir a ella para hacer de la URSS una potencia en astronáutica y cosmonáutica. A pesar de su evidente deformación, el cosmismo muestra un aroma inequívoco a doctrina que toma algunos elementos “tradicionales”: el cosmos como unidad, el ser humano como algo no concluido, superable, el vínculo entre el ser humano y la naturaleza, la percepción de ésta como de algo vivo… Estas ideas solamente pueden estar depositadas y prosperar en un medio que se haya visto libre de las contaminaciones industriales y que se haya mantenido arraigado en los valores tradicionales, esto es, una sociedad agraria. El Este eslavo era la mayor sociedad agraria de Europa y, por tanto, era allí done solamente una filosofía de este tipo podía enlazar con el folklore y las concepciones ancestrales de la Santa Rusia. El hecho de que la Iglesia Ortodoxa no hubiera “evolucionado” en el sentido en el que lo hizo su homóloga vaticana, acentuaba esta tendencia. Además, como se ha resaltado, uno de los ejes fundamentales de la teología ortodoxa son las relaciones entre el “Creador” y la “Creación”. Algunos cosmistas, como Florenski fueron auténticos teólogos ortodoxos, lo cual no puede extrañarnos. La idea que preside el fondo de la cuestión es la idea de “unidad”. El hombre es una pieza intermedia entre el “Creador” y la “Creación”, la pieza que asegura la unidad total del conjunto. Cuando el hombre toma conciencia de esta dimensión, adquiere su naturaleza “cósmica” que da explicación al nombre de la corriente de pensamiento. Lo “cósmimo”, en este sentido… es también “colectivo” y “común”, de ahí el interés que esta corriente tiene por el “comunismo” y por eso su militancia mayoritaria en el bolchevismo.

Fedorov. La Filosofía de la Causa Común.

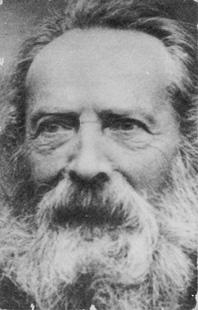

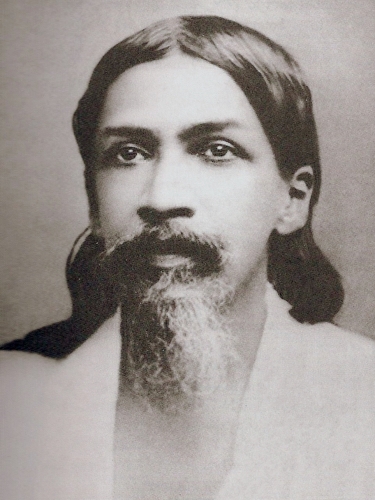

Las bases esenciales de la filosofía cosmista fueron teorizadas por Nikolai Fiodorovich Fedorov (1829-1903) y, posteriormente a él, desarrolladas en tres direcciones: una poético-literaria, con Platonov, Jlebnikov, Zobolotskii, etc.; otra filosófico-religiosa, con Soloviov, Berdiaev, Bulgakov, etc.; y una tercera científico-natural que tuvo a Tsiolkovskii, Umov, Vernadskii, Chizhevskii, etc, como sus jefes de fila. Seguramente, ninguno de todos estos grandes de la cultura rusa hubiera derivado sus trabajos hacia donde lo hicieron de no haber sido por la Filosofía de la Causa Común escrita por su mentor.

Nikolai Fedorovich Fedorov, pertenece casi más a la categoría de los místicos y ascetas que a la de los filósofos, al menos tal como eran concebidos en Occidente en esa misma época. En ruso su nombre se pronuncia Fiodorov pero se escribe Fedorov. Completamente ignorado en las historias de la filosofía escritas en Occidente, sus teorías fueron elogiados por los grandes personajes de la cultura y de la ciencia rusa de su tiempo y tiene, por derecho propio, un sitial en la historia de las ideas en aquel país. Dostoyevsky y Tolstoy glosaron sus ideas, el poeta Afanasiev las compartió, el filósofo Soloviev se inspiró en ellas y el cientifico Tsiolkowski las utilizó después de reconocerle un tributo de gratitud.

Es posible que su origen determinara su ascetismo y e incluso su irracionalismo idealista. Fedorov era hijo bastardo del príncipe Pavel Ivanovich Gagarin y de Elisaveta Ivanova, una mujer de la nobleza que hasta los cuatro años vivió en el palacio de los Gagarin. El fallecimiento del padre, determinó que la madre y sus demás hijos, abandonara el lugar. Pronto, Fedorov apenas cumplidos los 14 años se independizó y empezó a recorrer Rusia alimentándose con las clases que daba a alumnos de primaria. Salvo en esa época, cuando mantuvo una actitud errante y viajera, el resto de la vida de Fedorov a partir de los 25 años fue estable e incluso gris. En 1868 empezó a trabajar como bibliotecario en el musero Rumyantsev (actual Biblioteca Lenin) y luego entró en el ministerio de asuntos exteriores trabajando en sus archivos has la edad de jubilación.

A partir de estabilizar su vida, a los 25 años, fue adquiriendo el comportamiento de un verdadera asceta que, por otra parte, no era desconocido en la historia de la civilización rusa. Vivió durante casi toda su vida en una minúscula habitación provista solamente de una cama dura y de un escritorio. Rechazó publicar sus obras que tan solamente se conocieron en vida suya gracias a conversaciones con grandes de la cultura de su tiempo, a los que incluso ayudo a desarrollar sus ideas. Condenó la propiedad privada y él mismo rechazó tener nada que pudiera considerar suyo, ni siquiera abrigos o mantas. Por supuesto, rechazó la fama y los honores públicos. Se cuenta de él que durante meses apenas ingirió comidas calientes. Pasó casi toda su vida escribiendo y dando forma a sus ideas, sin embargo no prtendió publicar nunca ni una sola de ellas y solamente tras su muerte fueron publicadas. Tres años después de su muerte (1903) sus discípulos reunieron sus trabajos en dos gruesos volúmenes publicados bajo el título de Filosofía de la Causa Común.

Sabemos quién era Fedorov, veamos ahora el contenido de sus doctrinas. Fedorov no llamó a su filosofía “cosmismo” sino “supramoralismo”. Podemos establecer seis lineamientos fundamentales, cuya suma constituye lo esencial de la “causa común”:

1) Una interpretación de la evolución de la humanidad

2) Un transhumanismo holístico

3) La “salvación” como una experiencia común

4) Un análisis de la violencia en la historia

5) La necesaria superación de la muerte y

6) El papel central de Rusia en estas experiencias

No albergamos la menor duda de que si un sistema así hubiera irrumpido en Occidente, inmediatamente hubiera sido ridiculizado sin pasar siquiera por un análisis crítico de sus textos. Esta, seguramente, es la causa por la que el cosmismo ruso jamás interesó en Occidente. Cuando se tiene en cuenta, como veremos, que Fedorov predicaba una “superación de la muerte” y la posibilidad de un renacimiento posterior a la muerte, se entiende mejor el por qué en Occidente no fue tomado como una filosofía “aceptable”, sino más bien como un amasijo de corrientes místicas y seudoespiritualistas que, al igual que el ocultismo nacido en nuestras latitudes tampoco ha merecido un lugar en la historia de las ideas “académicas”. Sin embargo, ya hemos visto que las cosas se tomaban de manera muy diferente en Rusia y que el cosmismo fue aceptado y compartido por buena parte de la intelectualidad de su tiempo e incluso que Lenin, percibiendo un peligro en su bagaje neo-espiritualista, le dedicara 400 largas y densas páginas presentándolo como una forma de “idealismo pequeño burgués”.

Fedorov consideraba que el mayor problema que causaba los conflictos en el mundo era la falta de amor entre las personas. Eso generaba vilencia y aniquilaciones. Consideraba que el egoísmo era el motor de los conflictos. El egoísmo aislaba a unas personas de otras y los hacía difentes entre sí, rompiendo la unidad de la especie. En buena medida, esa violencia estaba generada por el miedo del ser humano a su finitud, es decir, por la dependencia del hombre a la naturaleza. Ésta dicta que debe de haber un “final” y, consiguientemente, cada individuo, cada familia, cada pueblo, consideran la supervivencia desde un particular punto de vista aislado del de los demás, en el que queda, por supuesto, excluido cualquier consideración holística de totalidad cósmica. Debemos preocuparnos, ante todo, de nuestra propia conservación, por supuesto defendiéndola de los ataques de los demás que piensan exactamente lo mismo. Lo que se manifiesta en esta actitud son tres condicionantes: egoísmo, individualismo y aislamiento.

Fedorov consideraba que el mayor problema que causaba los conflictos en el mundo era la falta de amor entre las personas. Eso generaba vilencia y aniquilaciones. Consideraba que el egoísmo era el motor de los conflictos. El egoísmo aislaba a unas personas de otras y los hacía difentes entre sí, rompiendo la unidad de la especie. En buena medida, esa violencia estaba generada por el miedo del ser humano a su finitud, es decir, por la dependencia del hombre a la naturaleza. Ésta dicta que debe de haber un “final” y, consiguientemente, cada individuo, cada familia, cada pueblo, consideran la supervivencia desde un particular punto de vista aislado del de los demás, en el que queda, por supuesto, excluido cualquier consideración holística de totalidad cósmica. Debemos preocuparnos, ante todo, de nuestra propia conservación, por supuesto defendiéndola de los ataques de los demás que piensan exactamente lo mismo. Lo que se manifiesta en esta actitud son tres condicionantes: egoísmo, individualismo y aislamiento.

La solución no era el altruismo, sino que cada hombre se identificara con todos los demás. Al mismo tiempo, existía también un conflicto entre “vivos” y “muertos” que hacía el el presente se aislara del pasado y del futuro. Por eso, cuando Fedorov aludía a identificarse con “todos los demás”, estaba aludiendo también a todos los que han sido (ya muertos) y a todos los que serán (los que estarán por nacer). Atribuyó parte de la responsabilidad de este conflicto al cristianismo y a una mala interpretación del cristianismo y llegó a considerar que la resurrección de los muertos y la victoria sobre la muerte no era algo que debía llegar en el momento de la Parusía, sino como objetio tangible a alcanzar en el curso de la evolución del mundo.

La teohumanidad es un concepto clave de la corriente cosmista que aparece en autores tan conocidos como Soloviof y Berdaiev. Alude concretamente a la naturaleza divina y humana de Cristo. No es raro que los estuvieron interesados en el análisis gnoseológico de la personalidad de la figura de Jesucristo. Éste ocupaba un lugar intermedio entre “dios” y el “hombre”, siendo a la vez lo uno y lo otro, una síntesis entre lo divino y lo humano. Cristo es pues el símbolo de la “unidad total” que los cosmistas defendían y a la que querían llegar. La “unidad total” es la unión de lo divino con lo terrenal, de la creación y del creador, de Dios y la naturaleza, del pasado del presente y del futuro. Ante esta “unidad total” el individuo no es nada en la medida en que para él lo que rije es la “finitud”. Para ocultar esta finitud e imponerse a los que considera amenazas, es por lo que recurre a la violencia. Por tanto, habrá violencia, esto es contradicción y conflicto, siempre que no se haya llegado a esa “unidad total”, remanso en el que estarán integrados y reunidos todos los aspectos del Cosmos.

Lo primero para alcanzar esa “unidad total” es tomar conciencia de que el ser humano está en estado de interdependencia con el cosmos. Todo lo que ocurre en él, nos afecta. Comprender el Cosmos, por otra parte, equivale a que el ser humano se comprenda a sí mismo. Si el Cosmos es una totalidad holística, el ser humano (entendido como especie y como unión de muertos, vivos y futuros nacidos) no es pues más que una parte de esa totalidad. Conocer las leyes que rigen a las fuerzas de la naturaleza equivale a dominar a la muerte. Por eso, el cosmismo insiste en algunos elementos paradójicos o aparentemente estrafalarios: Fedorov insiste en que es posible regular el clima y los fenómenos atmosféricos, cree que en la colonización del espacio exterior y en la victoria sobre la muerte como fin y objetivo de su sistema.

La historia era la crónica de las devastaciones y aniquilaciones que los seres humanos han realizado unos contra otros. Pero ello no debería de ser necesariamente así en el futuro. Solamente una humanidad que tomara conciencia de tal, esto es, conciencia colectiva de su unidad fundamental y de su identidad, estaría en condiciones de construir un mundo mejor. Si en el mundo, hasta ese momento, la muerte era la compañía eterna de lo humano, a partir del momento en el que la humanidad tomara conciencia de sí misma, sería posible vencer a la muerte y colonizar el cosmos. Para Fedorov la evolución es el patrón que rije lo humano. La evolución no termina en el momento en el que un homínido desciende de un árbol y se pone a caminar sobre las extremidades posteriores, sino en el momento en que la humanidad adquiere una naturaleza “cósmica”, tomando, primero, conciencia de sí misma y luego, colonizando el espacio exterior. Si puede pasar a esa nueva fase es precisamente por que ha adquirido las mismas características de ese espacio exterior: pureza, sensación de totalidad y porque ha sabido armonizar sus ritmos con los del cosmos. La conquista y colonización del espacio exterior, desde este punto de vista, no es solamente una hazaña técnico-científica, sino un signo inequívoco de evolución de la humanidad y de armonización con el cosmos. Había escrito: “La actividad humana no debe limitarse a los límites del planeta tierra”, a lo que añadió más adelante: “En todos los periodos de la historia es evidente una aspiración que muestra que la humanidad no puede conformarse con los estrechos límites de la tierra”. Para él lo importante de la salida del ser humano del espacio terrstre suponía el que entrara en contacto con las fuerzas cósmicas que prevía traumático si el hombre no había evolucionado y asumido esas mismas fuerzas, pero que era creativo y positivo para confirmarlas: “ante el rostro de las fuerzas cósmicas cesan todos los demás intereses: personales, de clase, nacionales; sólo un interés no se olvida: el interés general de todas las gentes, es decir, de todos los mortales”.

En su sistema Fedorov no considera la lucha de clases como el motor de la historia. Un análisis sociológico de la humanidad confirmaba a Fedorov en estas intuiciones. La humanidad se había convertido después del episodio de la Torre de Babel en una mixtura inextricable de razas y lenguas y luego, posteriormente, de naciones y clases sociales. Todo esto alejaba al ser humano de su propio ser originario: la unidad cósmica.

No divide a la humanidad entre quienes poseen los medios de producción y quienes no los poseen, sino que considera que existe una diferenciación fundamental entre el ser humano que posee cultura y el que no la posee. Mientras esta diferencación fundamental siga existiendo será imposible la evolución de la humanidad. Pero el problema es mucho más complejo que conseguir extender la cultura a todos los seres humanos. Un científico o un filósofo, por eruditos que sean, no detentan una posición esencialmente diferente de la del ignorante, si han abandonado las referencias morales. Para Fedorov, “cultura” se identifica con ética y con moralidad, no con conocimiento técnico y saber científico. La falta de una perspectiva ética y moral es lo que hace que el científico no sea capaz de entender la interrelación entre todos los fenómenos que se producen en el cosmos.

Pero allí en donde se demuestra en la naturaleza humana, el triunfo de la inmoralidad y la ceguera es en la persistencia del hecho de la muerte. Al examinar al ser humano, Fedorov entiende que los padres dan la vida para criar a sus hijos, pero estos no dedican su vida para levantar a los muertos, sino que se dedican de nuevo a crear nueva vida y a entregarse a sus hijos. En uno de los extremos más turbadores de su doctrina, Fedorov –el hijo natural de un noble que nunca se casó ni tuvo hijos, que jamás conoció a su padre más que cuando era muy pequeño y que no tuvo apenas recuerdos suyos- sostiene que es preciso resucitar a los muertos, mucho más que crear nuevas vidas. A poco uno consigue evitar la perplejidad ante esta idea, termina entendiendo que Fedorov de lo que está hablando es del “eterno retorno” (un tema que en aquellos mismos momentos, Nietzsche estaba enunciando), sólo que el lo define desde una perspectiva científica. Fedorov sabía que la cantidad de átomos existentes en el mundo es desmesurada pero finita. Sabía también que una vida dada no es más que la ordenación de esos átamos de una manera concreta y que, por tanto, tras la muerte, los átomos que habían dado lugar a una vida seguían existiendo solo que ordenados de otra manera. De ahí que considerara posible reconstruir una vida –esto es, resucitar a un muerto- simplemente uniendo lo que la muerte había desintegrado.

Pero allí en donde se demuestra en la naturaleza humana, el triunfo de la inmoralidad y la ceguera es en la persistencia del hecho de la muerte. Al examinar al ser humano, Fedorov entiende que los padres dan la vida para criar a sus hijos, pero estos no dedican su vida para levantar a los muertos, sino que se dedican de nuevo a crear nueva vida y a entregarse a sus hijos. En uno de los extremos más turbadores de su doctrina, Fedorov –el hijo natural de un noble que nunca se casó ni tuvo hijos, que jamás conoció a su padre más que cuando era muy pequeño y que no tuvo apenas recuerdos suyos- sostiene que es preciso resucitar a los muertos, mucho más que crear nuevas vidas. A poco uno consigue evitar la perplejidad ante esta idea, termina entendiendo que Fedorov de lo que está hablando es del “eterno retorno” (un tema que en aquellos mismos momentos, Nietzsche estaba enunciando), sólo que el lo define desde una perspectiva científica. Fedorov sabía que la cantidad de átomos existentes en el mundo es desmesurada pero finita. Sabía también que una vida dada no es más que la ordenación de esos átamos de una manera concreta y que, por tanto, tras la muerte, los átomos que habían dado lugar a una vida seguían existiendo solo que ordenados de otra manera. De ahí que considerara posible reconstruir una vida –esto es, resucitar a un muerto- simplemente uniendo lo que la muerte había desintegrado.

Fedorov considera que el amor a los antepasados encubre realmente una tendencia al egoísmo propio de lo humano. Amar los antepasados supone reconocer que estamos separados de ellos y aceptar lo inaceptable: la tristeza de la muerte. No se puede aceptar la muerto porque esto implicaría que cualquier persona es reemplazable por otra. Y no es así: cada ser humano, cada ser querido es único e irremplazable. No basta con sustituir el amor hacia la persona muerta por un nuevo amor: es preciso vencer a la muerte. Si nos parece irracional la muerte es porque no entendemos su proceso, pero para eso está la física y la ciencia para ayudarnos a desentrañar su misterio Y lo lograrán cuando unan a su erudición y profundización una visión ética y moral del mundo como totalidad.

La idea de “unidad” se repite en toda la literatura cosmista. Es omnipresente y obsesiva: todo el cosmos forma una “unidad”, el ser humano forma parte de esa unidad y solamente adquiriendo la conciencia de su pertenencia a esa totalidad logrará evolucionar hacia el siguiente estadio de la creación. Cada fenómeno que se produce en el cosmos, incluso en los lugares más remotos del mismo, repercute en la totalidad del cosmos. De ahí que, en su filosofía, una vez superada la antítesis entre el egoísmo y el altruismo, aparezca un “cristianismo cósmico” que no tiene en mente a tal o a cuales individuos, sino a la totalidad de los hombres.

Fedorov no se plantea el problema de la salvación personal que está implícita en todas las variantes de cristianismo, sino la “salvación completa y universal”. Seguramente al formular esta teoría se inspiró en el budismo mahayánico que establece ese mismo objetivo para el “iluminado”. Ahora bien, la “salvación universal” no es completamente dependiente de la actitud de los seres humanos. Escribe que “la salvación también podría existir sin la participación de los hombres y aun cuando estos no se unan en la tarea común”. No es que Fedorov crea en que la bondad de Dios, generará un marco adecuado para la salvación, sino que el mundo evoluciona independientemente de la actitud y de la voluntad de los humanos. Basta con que éstos se integren completamente en el Cosmos, para que se produzcan las condiciones favorables para una victoria sobre la muerte y para la salvación universal. En este sentido Fedorov recrimina al cristianimo que “no ha salvado completamente al mundo porque no ha estado completamente integrado en él” y que sea “una doctrina de redención, pero explique cual es la verdadera tarea de la redención”.

Es evidente que el cosmismo no hubiera podido prosperar en ningún otro marco geográfico, salvo en Rusia. Algunos de sus temas hunden sus raíces en el inconsciente colectivo de la nación rusa y de su cultura. En 1928, algunos exiliados rusos radicados en París iniciaron la publicación de la revista Evrazii (Eurasia) que apenas duró un año, pero en la que se encuentran algunos elementos interesantes para nuestro estudio, especialmente porque los pensadores euroasiáticos estaban influidos en buena medida por las concepciones cosmistas. En efecto, para ellos, Rusia no era un país “occidental” sino que, en sí mismo, era una síntesis de Oriente y de Occidente, con elementos eslavos, indoeuropeos, torfónofos y tártaro-mongoles. Los euroasiáticos exiliados llegaron a ver en la revolución de octubre, no un movimiento de carácter marxista y por tanto materialista, sino la expresión de las potencialidades más positivas de Rusia. Rusia, con el movimiento de octubre de 1917 dejó de ser un Estado que tendía a occidentalizarse bajo presión del zarismo, para ser esa síntesis de Oriente y Occidente que reclamaba un lugar en la historia. Rusia era, a partir de entonces, en definitiva, la estructura política que podía facilitar la realización de la “causa común” de la humanidad.

En su análisis sobre Rusia, Fedorov había concluido que no estaba contaminada por el individualismo occidental y que, por tanto, estaba más próxima de la “unidad” necesaria para poder realizar la “causa común”. Y este extremo es importante por que indica hasta qué punto Fedorov transformaba el mesianismo ruso de siempre, formulado en términos religiosos o místico-religiosos, en una concepción laica. Rusia, sostenía, Fedorov y uno de sus discípulos, Chaadaev, estaba llamada a tomar la vanguardia de la humanidad en la recuperación de su unidad originaria, pues no en vano, en la estructura misma de Rusia y en las corrientes que habían contribuido a su fundación, esa unidad estaba presente.

Hay en la filosofía cosmista algo que remite al viejo titanismo tal como fue descrito en la imagen de Prometeo. Había escrito, sintetizando su pensamiento: “Dios educa al hombre con su propia experiencia; Él es el Zar que hace todo, no sólo para el hombre, sino y a través del hombre; por algo no hay racionalidad en la naturaleza, porque debe ser el hombre quien la introduzca, y precisamente en esto reside la racionalidad superior. El Creador vuelve a crear el mundo a través de nosotros … Nosotros no podremos saber con seguridad con qué fuerza se mueve nuestra Tierra mientras no dirijamos su marcha”.

Los Constructores de Dios

Nuestro querido Pierre Pascal, titulala un parágrafo de su obra Las grandes corrientes del pensamiento roso comteporáneo, “Una herejía entre los bolcheviques: los constructores de Dios” y pasa revista en cuatro densas páginas a esta corriente inserta en el partido leninista. También el Diccionario Soviético de Filosofía habla de esta corriente bolchevique, aludiendo especialmente a sus jefes de fila, Lunacharsky, Bazarof, Gorki y, el más siniestro de todos ellos, Bogdanov. Puede haber algún malentendido: ¿cómo es posible que en una corriente cuyo eje era el materialismo algunos de sus miembros derivran hacia posiciones místicas?

No es difícil entender cómo se produjo este proces que, de hecho, tenía similitudes con otros similares en Europa Occidental. La pieza de transmisión fue el positivismo de Compte. A pesar de su voluntad de ser rigurosos, “científicos” y de apelar solamente a “datos positivos” (esto es, fehacientes), los positivistas fueron místicos de la peor especie que podríamos calificar con propiedad como la última rama del socialismo utópico aparecida en el tiempo. Los positivistas de Europa Occidentales crearon un “religión laica”, con sus dogmas, sus santos, sus apóstoles, sus rituales y sus profetas. Y lo hicieron deliberadamente. No es raro que en Europa Occidental el positivismo, los librepensadores, los teósofos, los vegetarianos, los esperantistas, los higienistas, etcétera, tuvieran frecuentes nexos con la izquierda política, laica, progresista y atea, hast el punto de que es muy difícil establecer dónde empiezan unos y terminan otros. Frecuentemente, todos estos grupos aparecían en manifestaciones obreras y de izquierdas en las dos últimas décadas del siglo XIX y hasta los años 30 del XX.

Los positivistas estaban presentes en todas las formaciones de izquierdas, no como corriente organizada, sino como individualidades que compartían el pensamiento de Auguste Compte. En Rusia, donde el positivismo estuvo fuertemente arraigado y contó con partidarios, algunos se adhirieron con posterioridad al conato revolucionario de 1905, al partido bolchevique. Poco antes, en 1903, Bulgakov hacía escrito una serie de artículos titulados “Del marxismo al idealismo” en los que resume las características de esta corriente. Por primera vez, en el seno del marxismo ruso, un grupo de intelectuales rompen la disciplina materialista y se configuran como los iniciadores de lo que ellos mismos califican como “nueva filosofía religiosa”.

Ha en esa serie de artículos de Bulgakov un lamento por una ideología, el marxismo, que percibe incompleta. Explica que “no se puede basar la conducta social y la búsqueda del progreso únicamente en la ciencia. No se puede proponer realizar el bien en la historia sin reslver el problema de la naturaleza del bien y, por tanto de Dios y del hombre” (Pierre Pascal). Dovstoyeski lo demostró: “Si hay un ideal, Dios, el esfuerzo hacia el bien, es decir, la organización de la sociedad en base a la igualdad y a la liberad, a la abolición de las clases y de todas las amenazas exteriores, ya no será un sueño, sin un tarea de la humanidad”. Tal era también la posición de Vladimir Soloviev que durante un tiempo coqueteó con la Sociedad Teosófica (véase la obra de René Guénon, El Teosofismo, en donde se alude a estas relaciones circunstanciales).

Si el marxismo era una corriente económico-filosófica, los “constructores de Dios” era una corriente filosófico-religiosa. Había irrumpido tras la derrota de la revolución de 1905. Esta derrota los animó a intentar completar el marxismo mediante el recurso a la religión, a una especie de religión atea y positivista, muy parecida en su esencia a lo que Compte había intentado.

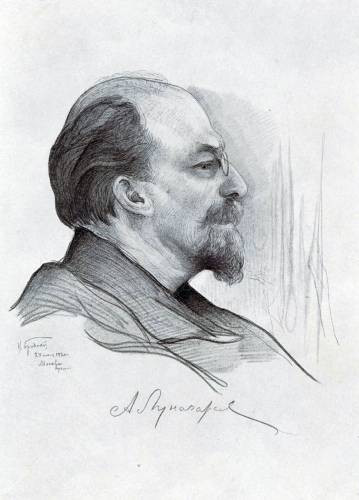

Durante un tiempo, Máximo Gorki participó de los ideales de esta corriente formando parte del grupo de “Los Constructores de Dios”. Dos de sus obras de ese período están inspirados por esta curiosa filosofía: «Confesión», de 1907 y «La destrucción de la personalidad», de 1909). Lenin polemizó con él duante un largo período y, finalmente, le indujo a romper con dicha corriente. Para publicitar sus argumentos contra este grupo ideológicamente disidente, Lenin escribió su voluminoso Materialismo dialéctico y empirocriticismo, una obra extremadamente sectaria y sin el menor paño caliente. Lenin no buscaba siquiera convencer, simplemente aspira a machacar a esta corriente y a impedir su acceso al bolchevismo. No hay medias tintas, tan sólo beligerancia y hostilidad manifiestas: Lenin se declaraba así radicalmente opuesto a la pretensión de unir el socialismo científico con la religión, desdiciendo así una de las frases que hicieron célebre a Lunacharsky: «…El socialista –escribió éste– es más religioso que el hombre religioso a la antigua» («Religión y socialismo», parte 1, 1908, pág. 45). Adora dos cosas: la humanidad y el cosmos.

Bogdanov, del que hablaremos específicamente más adelante, difundía la doctrina de los constructores de Dios desde la isla de Capri. Lenin y Plejanov contraatacaron calificando a la doctrina de los constructores de dios como “un reflejo de las vacilaciones ideológicas de una parte del proletariado influido por la ideología pequeño burguesa” (Diccionario de Filosofía Soviética). Lenin la condenó en bloque y sin paliativo posible: «…Tanto en Europa como en Rusia –escribió Lenin– toda defensa o justificación de la idea de Dios, hasta la más refinada y bienintencionada, es una justificación del espíritu reaccionario» (t. XXXV, pág. 93). Esta intolerancia, propia del leninismo, obligó a los constructores de dios a disolverse como corriente organizada. Pero siguieron actuando entre bastidores, no asumieron la ideología oficial, ni realizaron autocrítica en ningún momento. La muerte de Bodganov, como veremos, se debió, precisamente a haber llevado hasta el final sus principios ideológicos. En junio de 1909 la corriente fue oficialmente condenada por el comité central del partido bolchevique.

Aparte de las obras de Bogdanov -a las que nos referiremos más adelante- los constructores de dios se expresaron a través de Bazarov y Lunacharsky. El primero, justo antes de su condena por los bolcheviques explicó su concepción de lo que aspiraba su corriente: no había que confundir “búsqueda de Dios”, con “construcción de Dios”. Lo primero era una forma que adquiría el idealismo, vana tarea, por que según él, Dios no existía. Sin embargo, podía llegar a existir, “construido por el esfuerzo colectivo de la humanidad que edificaría un dios social y socialista”. Lenín tronó contra esta insensatez: “La búsqueda de Dios no se distingue en nada de la construcción, creación o invención de dios más que un diablo amarillo de un diablo azul”.

Ya fuera de la disciplina bolchevique, Bazarov pubicó en 1910 sus nsayos sobre la filosofía del colectivismo, en los que completaba este orden de ideas. Insistía en que el socialismo no se construiría por el cambio en las relaciones de producción ni por el acceso del proletariado a la propiedad de los medios de producción, sino por el advenimiento de una “nueva cultura proletaria”. Cuando estalla la revolución de 1917, la corriente todavía no ha sido barrida del partido bolchevique y está presente entre bambalinas, como lo demuestra el que en 1917, uno de los teóricos bolcheviques, Deborin escribiera una Introducción a la filosofía del materialismo dialéctico centrada en atacar a la filosofía de Ernst Mach y de Avenarius, consideradas como la fuente ideológica de la que bebían los “constructores de Dios”.

Es cierto que esta corriente no estuvo solamente presente en el bolchevismo (si bien, Bogdanov, Bazarov y Lunacharsky lo fueron), sino que también tuvo jefes de fila en el bando menchevique (Yushkevich y Valentinov). Pero, a pesar de esta aparente división, todos estaban de acuerdo en realizar una crítica al materialismo dialéctico y al economicismo de la doctrina marxista. Afirmaban querer “mejorar” el marxismo, algo contra lo que Lenin se rebela, nuevamente iracundo: les achaca un ataque taimado y velado contra los fundamentos histórico-científicos del marxismo, les acusa de no ser “francos ni honrado”, sino “hipócritas y, finalmente, los denuncia como enemigos del amrxismo que están realizando una “labor de zapa” y, por tanto, son “más peligrosos para el partido”.

“En menos de medio año -escribía Lenin en Materialismo y Empirocriticismo- han visto la luz cuatro libros consagrados fundamental y casi exclusivamente a atacar el materialismo dialéctico. Entre ellos, y en primer lugar, figura el titulado Apuntes sobre (contra, es lo que debería decir) la filosofía del marxismo, San Petersburgo, 1908; una colección de artículos de Basarov, Bogdanov, Lunacharski, Berman, Helfond, Yushkevich y Suvorov. Luego vienen los libros de Yushkevich, El materialismo y el realismo crítico; Berman, La dialéctica a la luz de la moderna teoría del conocimiento y Valentinov, Las construcciones filosóficas del marxismo… ¡Todos estos individuos unidos -a pesar de las profundas diferencias que hay entre sus ideas políticas- por su hostilidad al materialismo dialéctico, pretenden, al mismo tiempo, hacerse pasar, en filosofía, por marxistas! La dialéctica de Engels es un “misticismo”, dice Berman; las ideas de Engels se han quedado “anticuadas”, exclama Basarov de pasada, como algo que no necesita de demostración; el materialismo se da por refutado por nuestros valientes paladines, quienes se remiten orgullosamente a la “moderna teoría del conocimiento”, a la “novísima filosofía” (o al “novísimo positivismo”), a la “filosofía de las modernas ciencias naturales” e incluso a la “filosofía de las ciencias naturales del siglo XX” (Lenin, t. XIII, pág. 11, ed. rusa).

Contestando a Lunacharski, que, en la pretensión de justificar a sus amigos, los revisionistas en el campo filosófico, decía: “Por lo que se refiere a mí, también yo soy, en filosofía, un “indagador”. En estos apuntes, me he propuesto como tarea indagar en qué ha venido a para esa gente que predica, bajo el nombre de marxismo, algo increíblemente caótico, confuso y reaccionario” (Obra citada, pág. 12).

Anatoli Vasílievich Lunacharski (1975-1933), conoció en la universidad de Zurich a los que luego serían máximos dirigentes espartakistas alemanes, Rosa Luxemburgo y Leo Jogiches. Adherido al partido socialdemócrata, optó 1903 por sumarse a los bolcheviques de Lenin con quien colaboró en los dos años siguientes en el periódico Vperiod, pero, a partir de 1905, sus caminos se fueron distanciando. Lunachrsky a partir de esa época empezó a asumir la filosofía cosmista y a sostener la necesidad de incorporar la religión a la política marxista. Después de la Revolución de Octubre fue nombrado Comisario de Instrucción y formó junto a Bogdanov el movimiento Prolekult. Durante su labor como comisario de instrucción impulso un cómico y grotesco juicio contra Dios por sus crímenes “contra la humanidad” (primera vez que el tema aparece en escena). Una biblia figuraba en el banquillo de los acusados. Al final Dios fue declarado culpable. Poco después, un pelotón de fusilamiento disparó cinco ráfagas contra la Biblia para cumplir la sentencia. En 1933 fue nombrado por Stalin embajador en España. Murió en Francia antes de tomar posesión de su cargo. Nunca renunció a sus posiciones, por lo que hay que entender, que después de Lenin, los “constructores de dios” consiguieron ser aceptados por Stalin –mucho más interesado por la fidelidad a su persona que por la fidelidad a sus principios- en el aparato del partido.

Bogdanov: La Sangre es Vida

En 1926, León Trotksy escribió una despedida al poeta Sergio Esenin que fue incluido como apéndice del libro Literatura y Revolución. Esenin había nacido en 1895. De él dijo Lunacharski que “llegó de la aldea no como aldeano, sino en cierta forma, como un exponente de la inteligencia campesina”. Ganado para la agitación revolucionaria. Alcanza en Petogrado fama literaria cantando la vida campesina y la belleza de la naturaleza. Hay mucho espiritualismo en su obra que desemboca finalmente en una especie de panteísmo que percibe las estrellas, las flores, los árboles, tratados como objetos animados y en constante movimiento, transformándose unos en otros. Formó parte del grupo de socialistas místicos dirigido por Ivanov-Razumnik que proclamaban que “en el socialismo el sufrimiento del mundo salva al hombre”. Nunca pudo dejar atrás completamente su educación cristiana hasta el punto de aludir en 1971 a la Revolución de Octubre con Cristo resucitado, lo que no le impidió recibir una calurosa glosa por parte de Trotsky cuando falleció.

El elogio fúnebre de Trotsky es un pequeño texto de apenas cuatro páginas titulado En Memoria de Sergio Esenin. Escribe Trotsky: “Se ha ido por voluntad propia, diciendo adiós con su sangre a un amigo desconocido, quizá, para todos nosotros”, y más adelante, añade: “En su último momento, ¿a quién escribió Esenin su carta de sangre?”. Y apenas una página después: “cada uno de cuyos versos estaba escrito con la sangre de sus heridas venas”. Y finalmente, entre los últimos párrafos, Trostky escribe: “Los artistas vivían y viven en una atmósfera burguesa, respiran el aire de los salones burgueses, se impregnan cada día, en su carne y en su sangre, de las sugerencias de su clase. Los procesos subconscientes de su actividad creadora se alimentan ahí”. ¿A qué viene tanta insistencia con el tema de la “sangre”…?

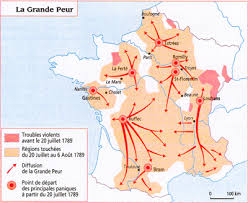

La sangre ejerció una fascinación particular en la Revolución Rusa, tal como antes la hubo ejercido en la Francesa. El recuerdo de esta última está inevitablemente asociado a la sombra de la guillotina, sin duda la forma más sangrienta y espectacular de ejecución. En la revolución de octubre todos estos elementos están incluso más acentuados y dominados por la bandera roja tomada como estandarte revolucionario. De hecho, la bandera roja ya se había utilizado como insignia de los movimientos obreros durante la Revolución Francesa. La Ley del 20 de octubre de 1789 decretaba el despliegue de una bandera roja para anunciar que el ejército iba a intervenir, con el fin de reprimir revueltas y motives urbanos. La Comuna de París utilizó como bandeja la roja que a partir de ese momento se convirtió en el símbolo de la insurrección revolucionaria y del movimiento obrero. En aquella ocasión, en marzo de 1871, los revolucionarios se apoderaron del Hotel de Ville en París, que era el centro de operaciones de la Comuna de París, e izaron la bandera roja de la revolución hasta el punto de que Marx pudo escribir en La guerra civil en Francia: “El viejo mundo se retorció en convulsiones de rabia ante el espectáculo de la Bandera Roja”. Antes, se había utilizado como símbolo de la insurrección contra Louis Philipe y de nuevo en febrero de 1848 volvió a ser estandarte de luchas sociales. Ya durante la insurrección de la Comuna de París, los revolucionarios proclamaron: “¡La bandera de la Comuna es la bandera de la República mundial!”. Años después, Federico Engels dijo de la Comuna: “Fue un valiente desafío a toda expresión de chovinismo burgué”s.

Comentando todo esto, Julius Evola, el genial compilador del pensamiento contra-revolucionario de la postguerra escribió en un artículo en el diario Roma (4 de mayo de 1955): “Nos podemos referir en primer lugar al simbolismo del color rojo. Se conoce muy bien aquel cántico que nos dice: “Levántate o pueblo para la liberación, bandera roja triunfará”. A partir de la bandera del Terror de los jacobinos en la Revolución Francesa , el “rojo” ha señalado permanentemente las consignas del radicalismo revolucionario, luego fue la insignia del marxismo y del comunismo hasta arribar a las “guardias rojas”, a la estrella roja de los Soviet y a la armada roja de la Rusia bolchevique”. Pero, añade Evola, no siempre fue así: “El color rojo, que se ha convertido ya en emblema exclusivo de la subversión mundial, es también aquel que, como la púrpura, se ha vinculado habitualmente con la función regia e imperial, es más, no sin relación con el carácter sagrado que tal función, fue muchas veces reconocido de esta manera. Al rojo de la revolución se le contrapone el rojo de la realeza. La tradición podría remitirnos hacia la antigüedad clásica, en donde tal color, que tenía una correspondencia con el fuego, concebido como el más noble entre todos los elementos (es el elemento radiante que, de acuerdo a los Antiguos, indicaría al cielo más elevado, el cual por tal causa fue denominado empíreo), se asoció también al simbolismo triunfal. En el rito romano del triunfo que, en la antigüedad tuvo un carácter más religioso que militar, el imperator vencedor no sólo vestía la púrpura, sino que en su origen se teñía de este mismo color, en el intento por representar a Júpiter, el rey de los dioses; esto en tanto se pensaba que Júpiter hubiese actuado a través de su persona, en modo tal de ser él el verdadero artífice de la victoria y el principio de la gloria humana”.

Evola prosigue su análisis simbólico citando ejemplos en los que, en otro tiempo rojo y púrpura fueron emblemas de la realeza: “En el mismo catolicismo, los ’purpurados’ son los ’príncipes de la Iglesia’. Existía el dicho: “haber nacido en la púrpura”, con referencia a una cámara del palacio imperial bizantino, en donde se hacía en modo que nacieran los príncipes de la Casa reinante. Entró en el uso de la lengua inglesa la expresión: he was born in the purple, para significar que una persona había nacido en un ambiente regio o, por lo menos elevadísimo”. Nuestro autor termina percibiendo una “inversión”: “El hecho que, sucesivamente, la asociación del rojo con la subversión puede haber tenido ciertas relaciones con el Terror, con el esparcimiento de sangre que formaba parte integrante de los pregoneros de la religión jacobina de la humanidad, no le quita para nada su carácter singular de proceso efectivo de inversión: el color de los reyes se convierte en color de la revolución”. Y, apurando este punto de vista, añade: “Justamente el uso moderno de la palabra “revolución” acusa una idéntica inversión de significado. En efecto el término ’revolución’, en su sentido primario y originario no quiere decir subversión y revuelta, sino justamente lo contrario, es decir el retorno a un punto de partida y movimiento ordenado alrededor de un centro inmóvil: por lo cual, en el lenguaje astronómico la “revolución” de un cuerpo celeste es justamente el movimiento que el mismo cumple gravitando alrededor de un centro, centro que regula la fuerza centrífuga, obedeciendo a la cual el mismo se perdería en el espacio infinito. Por lo cual, en razón de una natural analogía, también este concepto ha tenido un papel importante en la doctrina de la realeza. El simbolismo del ’pueblo’ aplicado al Soberano, punto firme, ’neutro’ y estable alrededor del cual se ordenan las diferentes actividades político-sociales, ha tenido carácter y difusión casi universales. He aquí por ejemplo un dicho característico de la antigua tradición extremo-oriental: “Aquel que reina a través de la virtud del Cielo (en términos occidentales se diría ’por la gracia de Dios’) se asemeja a la misma estrella polar: la misma permanece fija en su lugar, pero todas las otras estrellas giran a su alrededor”. En el cercano Oriente el término Qutb, ’polo’, ha designado no solamente al Soberano, sino también a aquel que en un determinado período histórico decreta la ley como jefe de la tradición.

El cosmismo y la cosmonáutica soviética

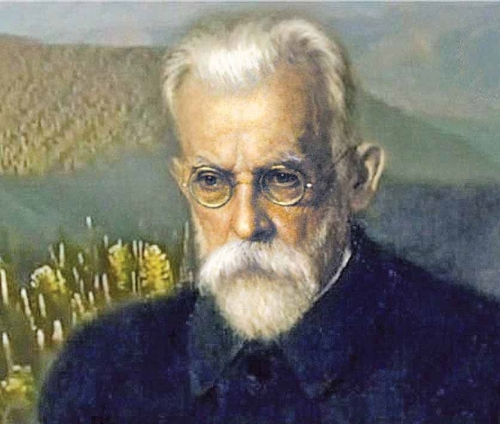

Uno de los cosmistas rusos más conocidos fue el físico ruso Konstantin Tsiolkovski, pionero de la astronáutica soviética. En 1903 escribió su obra La exploración del espacio cósmico por medio de los motores a reacción, primera obra científica en la que se anticipaba la posibilidad de viajar al espacio exterior mediante chetes. Sus intuiciones solamente pudieron llevarse a la práctica sesenta años después: sustitución de combustibles sólidos por líquidos, relación entre la masa de los cohetes y las posibilidades de abandonar la gravedad mediante una fórmula física, cohetes por fases, cabinas presurizadas dentro de las naves, giroscopios para el control de la altitud, formas de proteger a a los astronautas de la aceleración, etc. Tsiolkovski construyó el primer túnel aerodinámico para dirigiles y diseñó el primero de estas aeronaves. El título de una de sus obras en las que definió la importancia y posibilidades de realizar exploraciones interplanetarias sobre bases científicas, es significativo: Filosofía Cósmica. En 1919 ingresó en la Academia Socialista de Ciencias. Tsiolkovski fue uno de los cosmistas más famosos de su tiempo y la puesta en órbita del Sputnik 1 y del primer astronauta, Yuri Gagarin, se debió a sus cálculos y teorías. Gracias al cosmismo, los principios sobre los que se desarrollo la cosmonáutica soviética fueron completamente diferentes de los que nacieron en Alemania en el entorno de Werner von Braun que, finalmente, lograron colocar un hombre en la Luna.

Con Tsiolkovsky, el cosmismo deja de ser solamente una forma de filosofía particular para convertirse en una teoría científica. Es su “filosofía cósmica”, el cosmos es algo vivo y sensible: es materia, pero no sólo materia inerte, sino materia que tiene conciencia de ser tal. Su visión del mundo sostenía que la materia del cosmos es andrógina: masculina y femenina a la vez, es un compuesto inerte y material (“uno”), pero también sensible (“una”). Y toda la materia del cosmos forma una “unidad”. Tsiolkovsky había llegado al “en to pan” (todo en uno) de la filosofía hermética alejandrina a través del cosmismo de Fiodorov. El cosmos es, a la postre, una unidad orgánica y sensible.

El ser humano, por tanto, no es un proyecto acabo sino en constante evolución, de la misma forma que el ser humano actual es un ser a medio camino entre la animalidad y la excepcionalidad. Así pues el ser humano no es algo concluido, sino un “proyecto” que solamente se realizará por completo cuando logre entender su relación con la Tierra y adueñarse, por tanto, de ella. En ese momento, el ser humano tendrá la posibilidad de empezar a abordar su tarea “cósmica”. Esa etapa supondrá la madurez de la humanidad. De ahí que Tsiolkovsky dijera: “La Tierra es la cuna del hombre, el cosmos es su casa”. Así pues, el papel de la ciencia es la mejora de la evolución de la humanidad y la construcción de una sociedad más justa.

Tsiolkovsky desalló sus fórmulas y sus visiones sobre el futuro de la astronáutica no como ciencia pura, sino como instrumentos científicos al servicios de la filosofía cosmista. Para él, la exploración del espacio exterior, no era solamente una apasionante aventura científica, sino la aplicación de una filosofía en la que encontraba sus razones últimas. Lo sorprendente del pensamiento de Tsiolkovsky es que supone el último eco en el que la ciencia no tenía razón de ser en sí misma, sino era como aplicación técnica de una filosofía. A ese estadio, en Occidente, se le considera “pre-científico” y propio de épocas “pre-modernas”. En el fondo, en este terreno, el cosmismo es un eco remoto y ya casi irreconocible de las antiguas doctrinas tradicionales que dieron vida a la astrología, la magia, la alquimia, etc., antes de que nacieran la astronomía, la física o la química, ciencias, en definitiva, que aparecen sobre las bases de las antiguas tradiciones y conocimientos específicos.

El padre de la cosmonáutica soviética aceptaba la doctrina de Fiodorov según la cual “La Tierra no es sólo un cuerpo cósmico pasivo que recibe la influencia del cosmos, sino que, por ser parte del cosmos, participa activamente en la vida del mismo, en su evolución”. Así pues, el ser humano está implicado en un sistema de equilirios en el planeta tierra, tanto en su superficie (lo que le interesaba a Vernadski), como en el mundo subterráneo (que cautivaba al siniestro Bogdanov), como en el espacio (que seducía a Tsiolkovsky). Por ello el hombre es una entidad de “naturaleza cósmica”. Salir al cosmos, al espacio exterior y conquistarlo es, pues, un síntoma de evolución. El cosmos es, además, en esta concepción, sinónimo de perfección. Tiolkovski había escrito: “en el cosmos sólo existe verdad, perfección, poder y satisfacción, dejando para lo demás tan poco, que se puede considerar como una minúscula mota de polvo negro sobre una hoja de papel blanco”. Explorar el cosmos es, pues, empararse de esta perfección, actividad que solamente podía estar en condiciones de realizar un “hombre nuevo”.

Tsiolkovski fue contemporáneo de Fiodorov y asumió la totalidad de sus ideas. En este sentido tuvo algo de místico (es decir, de pensamiento pre-científico y pre-racionalista), pero también era lo suficientemente inteligente, imaginativo y dotado del espíritu cientófico como para llevar sus intuiciones a las abstracciones matemáticas y a las ecuaciones. A fin de cuentas, la filosofía de Fiodorov implicaba un evolucionismo extremo en el que todo está en constante movimiento y progreso y en el que incluso lo inanimado encierra en sí mismo la posibilidad de albergar cierto tipo de sensibilidad y la materia inanimada puede, por lo mismo, tener vida en estado de latencia que antes o después podrá manifestarse. Fiodorov sostenía –y Tsiolkovwky lo asumía- que la evolución no era solamente un proceso biológico de escalada hacia estadios superiores de organización de la materia, sino que incluso la sociología demostraba que también en ese terreno se tendía a formas “ascendentes” de organización social, en el límite de las cuales se situaría la “comunidad de bienes”. Al llegar a ese nivel, el ser humano “administraría la Tierra” y eso le generaría la posibilidad de saltar al espacio exterior y colonizar el cosmos. La ciencia y la técnica, para Tsiolkovski, eran los recursos necesario para abordar el progreso. En este sentido la polémica sobre la neutralidad de la ciencia, Tsiolkovski y los cosmistas la cerraban diciendo que la ciencia no puede ser neutral, no puede ser utilizada tanto para el “bien” como para el “mal”, sino que solamente puede conducir al “bien” en tanto que este “bien” se identifica con el “progreso” de la humanidad. Tsiolkovski aceptaba también la tesis de Fiodorov de que la ciencia, en el límite, debía garantizar la inmortalidad y su victoria sobre la muerte debía ser algo más que un hito científico para convertirse en el signo inequívoco de que la ciencia humana había evolucionado hasta convertirse en algo, en realidad, superior a la ciencia o bien en el instrumento a través del cual la humanidad se diviniza, pues la esencia de lo divino es la superación de la muerte. Probablemente, las ideas de Tsiolkovski eran menos inquietantes que las de Bogdanov y su afición siniestra por las transfusiones de sangre o su admiración enfermiza por unos “marcianos” deformes y dotados de los rasgos que habitualmente se han concedido a Satán y al infienro, pero no eran esencialmente diferentes. No es raro, pues, que ambos terminaran en el partido bolchevique. Por si hubiera alguna duda, el propio Tsiolkovski lo había confesado explícitamente: “por naturaleza o por carácter, soy revolucionario y comunista. [creo en] los beneficios de la comuna en el sentido amplio de esta palabra”.

A pesar de la poca simpatía que Lenin tenía hacia el cosmismo y hacia los “constructores de Dios”, la capacidad científica de Tsiolkovsi, hizo que ya en vida de Lenin éste lo situara bajo la protección del Estado. Más tarde, Stalin reconoció oficialmente su aportación a la ciencia soviética y sus consignas y frases fueron convertidas en eslóganes del régimen. Éste celebró el setenta aniversario del viejo profesor homenajeándolo y concediéndose la orden de la Bandera Roja del Trabajo. Tsiolkovsky murió cosmista y bolchevique.

En 1926 fue reeditado el libro La investigación del cosmos con aparatos a reacción y en 1927 y 1929, fueron publicados los libros El cohete cósmico y Los trenes-cohetes cósmicos, escritos por Tsiolkovski, alcanzando siempre tiradas superiores a los 40.000 ejemplares. La sociedad soviética de la época experimentó, pues, una especie de interés irrefrenable por la cosmonáutica todavía balbuciente y en estadio de mera teoría. Se crearon grupos de amantes del espacio exterior, de aficionados a la astronomía que veía un cosmos al otro lado de sus ópticas que consideraban como nuestro “hábitat futuro”. Surgió también un estusiasmo creciente en los medios científicos al percibir que la exploración del espacio exterior era aceptada por el régimen soviético y no existiría contradicción –al menos en ese terreno- entre los principios del marxismo-leninismo y las ciencias aplicadas. Luego, cuando se produjo en escándalo Lysenko, cuando la genética clásica entró en contradicción con el marxismo, se vio que un científico que investigara en áreas conflictivas podía terminar en el universo concentracionario soviético. Aparecieron entonces las figuras de Kondratiuk (que en 1929 publicó un libro de título evolados: La conquista de los espacios interplanetarios en el que diseñó de manera extremadamente precisa el sistema hoy utilizado de “cohete por fases” y estableció que la Luna sería la “etapa previa” a la conquista del espacio). Más joven que él, Alexandr Chizhevski, científico, filósofo cosmista y bolchevique demostró la influencia del sol en la biosfera y en el ser humano en un intento de confirmar la intuición de Fiodorov de que “el Todo influye en todo”, una visión holística –hoy aceptaba, por lo demás- en el que cualquier repercusión negativa en el medio ambiente, influye también negativamente en la totalidad de la vida humana y en el que la búsqueda de “equilibrios cósmicos” es esencial para garantizar la “evolución de la especie humana”. La tesis de Chizhevski era importante también por que tendía a demostrar que el “cosmos” influye en cada uno de nosotros.

Koroliov, no pudo evitar tener en un momento de su vida (en 1938) problemas con el régimen y resultó condenado a 10 años de prisión. Sin embargo, en julio de 1940 envió una larga carta a Stalin en la que explicaba que había sido víctima de un complot que pretendía impedir la continuación de sus trabajos sobre motores a reacción. Liberado en 1944 y recibido por Stalin, se convirtió en el director de la industria soviética de cohetes, siendo completamente rehabilitado en 1957 tras la puesta en órbita del Sputnik. Hoy está enterrado en las muerallas del Kremlim como máximo gesto de reconocimiento del régimen soviético.

El Sputnik 1 y la hazaña de Yuri Gagarin, primer astronauta que salió al espacio exterior, son hijos directos de estas concepciones cosmistas que demuestran que esta corriente filosófica no se había agotado sino que permanecía viva y en el tiempo. No en vano, el primer satélite artificial Sputnik se lanzó el 4 de octubre de 1957, cuarenta años después de que los bolcheviques asaltaran el Palacio de Invierno. Tsiolvoksy lo había previsto en su obra Sueños de la Tierra y el Cielo. De apenas 83 kilos y dotado de dos transmisores de racio, envio información sobre las concentraciones de electrones, temperatura y presión de la ionosfera. Sputnik significa: “compañero de viaje”, esto es, “satélite”. Su forma era esférica (a pesar de que el primer diseño era cónico, por algún motivo, se modificó: ¿acaso inspirado en la consideración platónica de que la esfera es el cuerpo sólido más perfecto –y, por tanto, en la filosofía cosmita, el más “digno” de penetrar en el espacio exterior, puro y virginal- en la medida en que todos los puntos de su superficie tienen la misma distancia del centro y que éste es a la vez, uno e infinito, pues no en vano de él parten los infinitos radios que constituyen la superficie de la esfera?). Pero hasta llegar al Sputnik, toda la industria aeroespacial soviética parecía dirigida por cosmistas y ordenada según los principios de la filosofía de Fiodorov. Es significativo, por otra parte, que el primer astronauta, Yuri Gagarin, estuviera lejanamente emparentado con Fiodorov, el cual era hijo de Fiodorov Pavel Ivanovich Gagarin.

Se ha señalado así mismo que los cosmistas atribuyeron particular importancia a las virtudes éticas y morales de los primeros astronautas. Así como en los EEUU se tendió solamente a elegir como astronautas a pilotos de pruebas, algunos de los cuales –como es el caso de Neil Amstrong, primer hombre que pisó la luna, era, lo que humanamente se puede definir como un verdadero patán y que se limitó a repetir las frases que le habían sido escritas para pronunciar cuando pisó el satélite, siendo el resto de conversaciones que no se llegaron a difundir, con su compañero, con la cápsula que orbitaba en torno a la luna y con la NASA, instrascendentes (sobre perritos calientes y asadores de carne)- a militares que encarnaban en sí mismos las cualidades cosmistas. Esto se debía, como hemos dicho, a la intuición de que un espacio “puro” solamente puede ser invadido por quienes sintonizan con él, esto es, cosmonautas igualmente “puros”. Así mismo, como en las doctrinas ocultistas que veremos a continuación, cada astronauta, tenía a su “doble” y Titov era el “doble” de Gagarin. En ambos casos se trató de fervientes y abnegados comunistas con un compotamiento ético, político y social, ejemplar. Gagarin murió en accidente de aviación, pero Titov, al desplomarse la URSS abandonó sus cargos políticos en el Ejército Soviético y en 1999 fue elegido miembro de la Duma por el Partido Comunista.

La cosmonáutica soviética encontró a Tsiolkovski como a su genial inspirador y teórico, pero otros muchos cosmistas participaron de ella y fue otro cosmista, Serguei Pavlovich Koroliov quien llevó el proyecto a la práctica. Koroliov seleccionó personalmente a la primera generación de cosmonautas soviéticos. Les decía: “Nuestro interés en el conocimiento del Universo no es un objetivo en sí mismo. No hay conocimiento por el placer del conocimiento. Nosotros nos introduciremos en el cosmos para estudiar mejor el pasado y el presente de nuestro planeta, para prever su futuro. Nosotros queremos poner los recursos y posibilidades del cosmos al servicio del ser humano, investigar otros cuerpos celestes, y sí las circunstancias lo exigen, estar preparados para poblar otros planetas”, y terminaba su arenga citando a su mentor: “Como dijo Tsiolkovskii, la conquista del cosmos nos promete montañas de pan …”.

Inicialmente, Koroliov solamente aspiraba a construir aviones a reacción hasta que conoció a Tsiolkovsky. Él mismo explica el encuentro: “como ya he dicho, tuvo una gran influencia sobre mí, [y] decidí construir sólo cohetes. Konstantin Eduardovich nos asombró, ya entonces, a todos con su fe en la posibilidad de la navegación cósmica. Cuando nos separamos yo me fui con un sólo pensamiento: volar hacia las estrellas. Con un gran respeto recuerdo al segundo de mis maestros, quien también tuvo una gran influencia sobre mí, me refiero a Fridrij Arturovich Tsander. Nunca olvidaremos sus palabras: “¡Viva el trabajo para los viajes interplanetarios al servicio de toda la humanidad! ¡Cada vez más y más alto, hacia las estrellas!”. Tsander, por supuesto, también era cosmista, fue el primero en diseñar motores de cohetes capaces de navegar por el espacio exterior. Cosmista, fue al mismo tiempo, un fervoroso comunista que se entrevistó con Lenin a quien interesó en las posibilidades de la exploración del espacio exterior y del que recibió apoyo para sus trabajos que luego, Stalin amplificó.

El hecho de que la estación espacial inicialmente soviética y luego rusa, llevara el nombre de Mir no es tampoco inocente o casual. En lengua rusa MIR significa mundo, comunidad campesina, paz, sociedad humana, tranquilidad, silencio, conceptos todos ellos que engarzar directamente con el nudo de la filosofía cosmista. Es significativo que cuando la segunda tripulación de la MIR reemplazó a la primera, el 8 de febrero de 1987, éstos se encontraran en la estación el pan y la sal, símbolo de bienvenida en las tradiciones campesinas. Así mismo, resulto extraordinariamente significativo el que a partir de 1987 la estación espacial “se abriera” a otras nacionalidades, como si el primer intento de colonizar de manera estable el espacio exterior (la duración de la estación espacial MIR fue de 13 años y a partir de 1987 fue permanentemente ocupada por astronautas) no fuera competencia solamente de una nacionalidad (la soviética), sino de toda la humanidad con astronautas aportados por la Agencia Espacial Europea o por la NASA. Este programa “humanista” alcanzó su clímax cuando llegó a la estación MIR el primer cosmonauta afgano, Abdul Mohamed, quien al llegar a la estación abrazó el Corán y entonó una plegaria. También se incorporó durante algunos días, de manera simbólica un cosmonauta japonés, Toehiro Akiyami e incluso el español Pedro Duque participó en la coordinación de algunas de estas misiones desde la tierra.

Pero cuando esto ocurría, las ideas cosmistas apenas se conocían ya en Moscú. El régimen bolchevique había caído. La URSS había entrado en un proceso de “americanización” que duró desde 1986 hasta 1999, había perdido en poco tiempo las tradiciones culturales y filosóficas. La inteligentsia rusa dejó de mirar hacia sus propias fuentes y prefirió abrirse a “occidente”. El cosmismo resultó olvidado. Sin embargo, la doctrina cosmista encontró algunos reflejos en la ideología humanista y universalista de la UNESCO que, por lo demás, más conocida en Occidente, fue la que alimentó la transformación de la Estación Espacial MIR, en Estación Espacial Internacional. Por lo demás, tampoco había tantas diferencias… En Occidente, las mismas ideas cosmistas se habían difundido por otros canales.

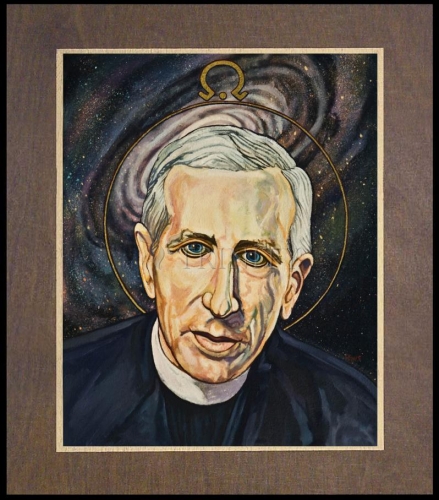

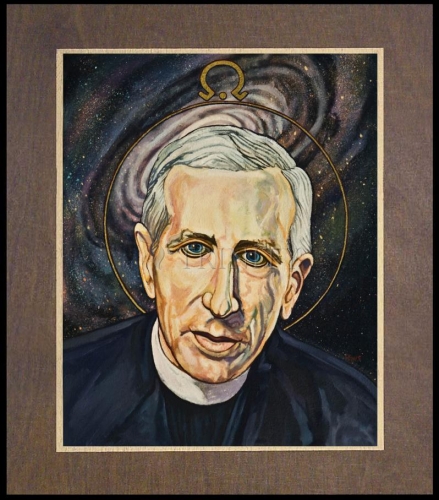

Teilhard de Chardin, la New Age y la Noosfera

El pensamiento del padre jesuita Teilhard de Chardin es en más de un sentido parelelo al del cosmismo ruso y modela solo unas décadas después de que los discípulos de Fedorov recopilaran sus escritos bajo el título de Filosofía de la Causa Común. Teilhard se mueve en tres direcciones: en primer lugar en dirección científica, intentando completar la teoría de la evolución que ocupa un lugar central en su doctrina. Intenta, en este terreno, buscar pistas paleontográficas sobre los “eslabones perdidos” que certifiquen de una vez y para siempre que el ser humano es un producto de la evolución de especies inferiores. En segundo lugar, confirmada la evolución de las especies como nuestro destino, establece que ésta no ha terminado todavía sino que prosigue y que solamente se detendrá cuando la humanidad alcance su punto límite en la evolución. En tercer lugar, establece la “noosfera” como el teatro en el que se desarrolla la actual etapa de evolución de la humandiad. Y es precisamente éste último concepto el que permite vincularlo directamente a la filosofía cosmista y, en especial, a uno de sus exponentes, Vladimir Ivanovich Vernadski.

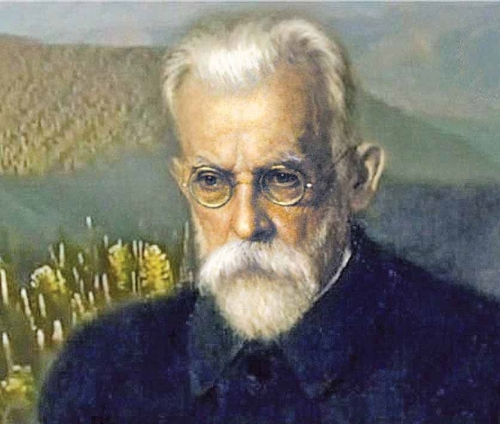

Vernadski es contemporáneo de Teilhard y sólo unos años más joven que él. No es filósofo, sino científico y a lo largo de su vida realizó incursiones en el estudio de la biósfera, siendo uno de los precursores en este orden y contribuyendo a la fundación de ramas de la ciencia como la mineralogía, la genética, la bioquímica o la radiogeología. Los estudiosos de su obra resaltan su carácter multidisciplinario y sintético. Pero, además, la obra de Vernadski tiene también una componente política. Alineado inicialmente en las filas de la contrarrevolución, se exilió al termina la guerra civil con la derrota de los “blancos” hasta que unos años después volvió a Rusia, reconocimiento explícitamente que los fundamentos del bolchevismo no estaban muy alejados de la filosofía cosmita que compartía y reorganizó la Academia de Ciencias de la URSS logrando influir decisivamente en las orientaciones de las nuevas generaciones de científicos y en la política científica del régimen soviético.

Su concepción de la biósfera, concretamente, enlazaba directamente con las preocupaciones habituales de Fedorov y de sus discípulos, la idea de la “unidad”. Para Vernadski, la biósbefa es el lugar donde existe la vida y es fuente de toda materia viva. Es el habita del ser humano al que está vinculado y del que es dependiente. La biósfera pertenece a la Tierra, pero también al cosmos al estar en contacto, directamente, con la parte exterior de la Tierra. De ahí que los seres vivos tengan, precisamente por eso, una dimensión cósmica. En este sentido no existe una “libertad absoluta”, sino un estado de dependencia entre todos los seres vivos y entre ellos y la biósfera.

Vernadski había elegido la ciencia como un método para alcanzar la verdad. Los otros dos terrenos que habían competido con ella en el mismo objetivo eran la religión y la filosofía. La superioridad de la ciencia en relación a la religión y a la filosofía residía en que solamente ella era capaz de incorporar a sus reflexiones el estudio sobre la biósfera. Ella, era pues, la madre de las otras dos muestras del genio humano porque aludía al hecho básico de la naturaleza humana: la vida, esa vida desarrollada en la biósfera. Vernadski tenía una confianza ciega en la ciencia y seguía en esto los desarrollos de Fedorov sobre la necesaria integración de ciencia y moral, síntesis progresista del futuro. Había escrito: “La ciencia representa la fuerza que salvará a la humanidad”.

El optimismo de Vernadski se basaba en que a principios del siglo XX, los avances científicos en la comprensión de los mecanismos de la materia y de la biósfera, habían sido inigualables en relación a períodos anteriores. Las exploracines, los transportes, los medios de comunicación entonces incipientes, permitían al ser humano tomar posesión de la biósfera. Vernadski opinaba que esa posesión debía de hacerse en nombre de la “humanidad” Pero si el hombre estaba en posición de dominar la biósfera se debía a que poseía un elemento superior: la razón y la voluntad. Y esto le llevó a formular un concepto nuevo, el de “noosfera”.

En la concepción de Vernadski (que aceptaba la clave cosmista de cinco ramas integradas en un todo que ya hemos visto en Bogdanov y en el símbolo egipcio del duat) la Tierra es una unidad compuesta por cinco realidades integradas: litósfera, atmósfera, biosfera, tecnosfera y noosfera. Ésta última sería la “esfera del pensamiento”. Vernadski observó que todas estas capas estaban interrelacionadas y que no sería posible la existencia de ninguna de ellas sin algún tipo de colaboración o compenetración con las demás. Todas además estarían en permanente evolución (Vernadski no se planteaba hacia dónde). Los últimos desarrollos de la física de su tiempo ya aludían a la existencia de isótopos que no serían más que minerales que mediante la pérdida de algún electrón se van transformando progresivamente. Nada que la antigua alquimia clásica no hubiera ya definido anticipadamente aludiendo a la evolución inevitable de los metales y a que todos tienden hacia el oro mediante un lento proceso de “maduración” que el alquimista puede acelerar mediante la fabricación de un catalizador o “piedra filosofal”. Por tanto, cuando Vernanski y los cosmistas hablan de “evolución”, a diferencia de la ciencia occidental que alude solamente a evolución de las especies, se están refiriendo también a la evolución geológica y a la evolución de la cultura.

Sin embargo, el nombre de Vernadski estará indisolublemente unido al concepto de noosfera que promovió y estudió. La noosfera es, a la vez, su contribución al cuerpo científico-filosófico del cosmismo ruso y el nexo de unión con Teilhard de Chardin. Vernandski llama noosfera la “esfera del pensamiento”, esto es, a la específicamente humana que deriva de la evolución de las células más perfectas del ser humano, esto es, a la vanguardia en la evolución de las especies, las neuronas. La noosfera debe su nombre al término griego “noos”, pensamiento y se define como el conjunto de los seres inteligentes con el medio en que viven.