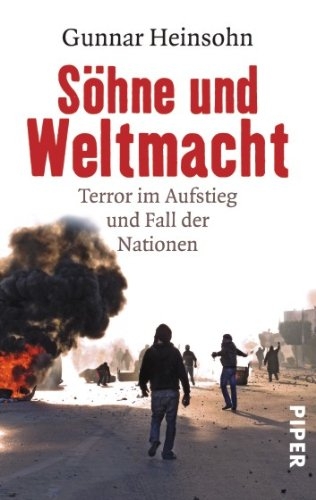

Gunnar Heinsohn

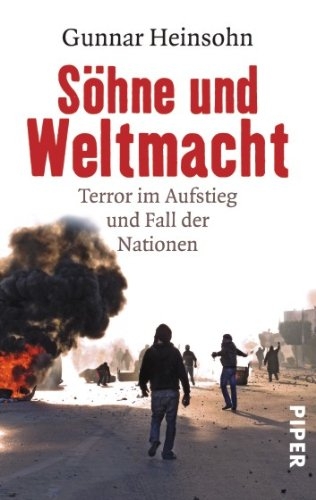

Söhne und Weltmacht: Terror im Aufstieg und Fall der Nationen

Zürich, Switzerland: Orell Füssli Verlag, 2020 (2003)

Robert Malthus’s essay on population growth is widely known and widely refuted, mostly by commentators who have not read it. In his Essay on the Principle of Population, Malthus argued that population growth undermined the achievements which technology had brought and was bringing to human society and ironically had first made that population growth possible. Populations, he wrote, increased faster than the rate of increase in food production necessary to keep pace with the demand for more food. According to Malthus, this discrepancy between supply and demand would lead inevitably to a decline in living standards and to famine. That Malthus’s prediction proved (broadly) not to be the case in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is largely due to the fact that human societies have vastly improved agricultural efficiency and available agricultural land far in excess of the slow growth in food production which Malthus had projected. This improvement in food production to meet the demands of growing populations could only be achieved, and was only achieved, by improved logistics, improved science, and exploiting nature — not only more efficiently, but also more extensively. The fear of famine and outbreaks of famine have continued down to the present day, however, and although Malthus is officially repudiated, his ghost has not been lain to rest. The burden put upon nature incurred by meeting the challenge of the appetites of the human population increase continues to this day. Has Malthus been proved entirely wrong, and is his thesis applicable in relation to challenges other than that of famine?

Robert Malthus’s essay on population growth is widely known and widely refuted, mostly by commentators who have not read it. In his Essay on the Principle of Population, Malthus argued that population growth undermined the achievements which technology had brought and was bringing to human society and ironically had first made that population growth possible. Populations, he wrote, increased faster than the rate of increase in food production necessary to keep pace with the demand for more food. According to Malthus, this discrepancy between supply and demand would lead inevitably to a decline in living standards and to famine. That Malthus’s prediction proved (broadly) not to be the case in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is largely due to the fact that human societies have vastly improved agricultural efficiency and available agricultural land far in excess of the slow growth in food production which Malthus had projected. This improvement in food production to meet the demands of growing populations could only be achieved, and was only achieved, by improved logistics, improved science, and exploiting nature — not only more efficiently, but also more extensively. The fear of famine and outbreaks of famine have continued down to the present day, however, and although Malthus is officially repudiated, his ghost has not been lain to rest. The burden put upon nature incurred by meeting the challenge of the appetites of the human population increase continues to this day. Has Malthus been proved entirely wrong, and is his thesis applicable in relation to challenges other than that of famine?

Söhne und Weltmacht by Gunnar Heinsohn, professor at the University of Bremen, is written in the Malthusian tradition of seeking in demographics the key to understanding social and political challenges. It is the principal argument of Söhne und Weltmacht that it is neither a struggle for resources, nor of religion, nor a conspiracy, that is the principal driving force of terror and war, but rather a surplus of young men who, by virtue of a demographic spike, are too many competing for too few positions in their own communities.

More exactly, according to Heinsohn, it is a diminished opportunity to obtain “property benefit” (Eigentumsprämie), a key term in Heinsohn’s argument. This book is Walt Whitman’s cry of “Go West, young man!” with a vengeance. A society whose population increase, or more exactly, increase in young men, cannot be met by a commensurate increase in opportunities for those young men to thrive by obtaining property benefits and social standing, is the major trigger of terrorism, war, colonialism, and mass emigration. This is a startling thesis, but it is argued cogently and with abundant recourse to evidence. Indeed, Heinsohn’s work abounds with references, citations, and graphs and tables to support the main thesis.

Here is one historical case which Heinsohn examines: Nepal. How could it be, he asks, that Nepal changed almost overnight from a happy hippy Mecca, where the stardust children of the West sought enlightenment and inspiration in the 1960s and 1970s, into a land racked by civil war, strife and terrorism in the 1990s? What was the cause of the Maoist rebellion? Standards of living? The oppression and solidification of the proletariat, in accordance with Marxist theory? The desperation of famine, in accordance with Malthusian theory? None of that. The people were not starving and living standards were in fact rising. The population was not desperate or threatened from outside. Journalists speculated on Chinese influence undermining the small land by infiltrating it with Maoist revolutionary theory. Heinsohn comments on the theory of Maoist subversion laconically:

If Bakunin’s work had been widely read in Nepal instead of Mao’s, the media might be reporting about anarchists against the police instead of Maoists against the police. Young people will always find something. Irony to one side, the killers took great chunks out of their differentiated convictions. They not only attacked feudalists and fascists but the national Marxist-Leninist movement as well as the united Marxist-Leninists and finally, the Indian army. (p. 105)

The real reason for the upsurge in conflict is clear to Heinsohn:

Rising from 8.5 to 26 million, the population tripled from 1950 to 2005. In 1995 and 2000 the children bulge was at 41%. With over 4000 deaths between November 2001 and January 2003 talks over a ceasefire between the authorities and the insurgents began. Were the talks to collapse, so the Minister of Culture Kuber Prasad Scharma at the end of May 2003, the country would be facing “Cambodian relations” viz. genocide. Peace was finally concluded on November 21st, 2006. The conflict had cost near to 18,000 lives.

Then Heinsohn throws in his final comment, the fact which for him is decisive and not brought into calculations of war and peace: namely, the falling birth rate. “From 6 children per woman between 1950 and 1985, the birth rate had fallen to under two by 2020.” (pp 105-106).

What is the “children bulge” referred to here? Heinsohn has much to say about what he calls demographic “bulges”: youth bulge, baby bulge, children bulge. A bulge refers simply to a disproportionate dominance by one age group in a nation’s or group’s demographic structure. A youth bulge is defined by this writer as follows:

The existence of a youth bulge results from the places which are becoming available to the number of places which sons who are becoming adults demand.” (p. 55) It is the existence of a baby bulge becoming a youth bulge (a baby bulge does not necessarily become a youth bulge if there is a high infant mortality rate) which is the prime course, Heinsohn argues, of “migration, crime, mass flight, prostitution, forced labor, murder, gang crime, terror, putsches, revolutions, civil war, expulsions of groups, genocide. . . As a rule of thumb: nations with 30 to 50% of their populations under 15 years of age will be experiencing one or more of these. (p. 115)

The Biblical tale of Cain and Able is, for Heinsohn, a fable that tells the story of a fundamental truth. Two brothers competing for one position, one recognition, one property benefit, must emigrate, colonize or kill one another.

Heinsohn also refers to what he calls the Kriegsindex (war index). This is the yardstick he has devised to measure the military potential of a group in terms of its manpower by comparing the number of 55 to 59 year-olds to the number of youths between 15 and 19 in the studied group. If the number of 15-19 year-olds is higher than the number of 55-59 year-olds, the war index is positive, and negative in the reverse case. So if there are 1000 old people to 2000 youths, the war index is 2+. The US-Vietnam conflict cost nearly a million lives, of which an astonishing 95% were North Vietnamese, but the Vietnamese war index was 4 to the American 2. The North Vietnamese could afford their losses better than the Americans.

An objection can certainly be made that Heinsohn ignores the factor of technical superiority — possession of the atomic bomb, for example — to counteract or even nullify the war index factor. However, in the great majority of conflicts that have taken place since the Second World War, the superiority of military hardware does not seem to have played the decisive role which might be expected of it. As for atomic confrontation, the wars since the Second World War have been wars of proxy insofar as the nuclear powers were involved. Arguably, Israel is the one country that keeps numerically superior forces at bay by its possession of the technology to destroy entire nations, but it also has a high war index.

The objection can be made that in terms of conflicts between major powers, the war index factor may play a less considerable role. My impression is that Heinsohn indeed tends to gloss over facts and factors such as firepower superiority which might weigh against his principle theory of youth bulges and war. However, it is questionable how far even a nuclear deterrent can stop a human tidal wave which has reached a vastly disproportionate superiority in numbers. Was it not Mao Tse Tung who once callously remarked that in the event of nuclear war, China would win simply by virtue of its huge population? One of Heinsohn’s many statistics, extrapolated from data provided by the World Bank for 2020, is that the proportion of children under 15 years old from nations with a children bulge (30-50% of the population) in relation to children in the United States is 1.3 billion to 61 million.

We should, of course, be aware of statistics. Heinsohn offers his readers an abundance of them, but are they conclusive? It may be that hikes in the population are not the direct cause of the factors he describes, but bring about developments which trigger them. Yet even to admit that populations hikes are the indirect rather than direct cause of war and famine is still to admit that they play a decisive role, and to argue that the effect is indirect would be to qualify Heinsohn’s thesis without in any way refuting it.

A further controversial argument of this book is that dictatorship and children bulges tend to accompany one another. Heinsohn notes that the Algerian military overruled unwelcome election results in 1991 at a time when the population had more than doubled, rising between 1960 and 1990 from 10 to 25 million. More people were killed in the course of internal conflict in Algeria between 1992 and 2002 (180,000) than in Arab-Israeli wars over the same period. (p. 116) Algeria used to record a birth rate of 6 to 8 children per mother; the birth rate has fallen in recent years to 3 children per mother. Heinsohn feels it unnecessary to point out that conflict has subsided in Algeria since the beginning of this century. The reader gets the point.

The core argument of the book is, therefore, that problems of war and famine are demographic — not climatic or economic in the traditional sense of rich and poor. It is certainly the case that the role of population is rarely treated earnestly by political and economic writers, professors, and journalists. This reviewer shares Heinsohn’s belief that exponential population growth lies behind many major global challenges, if not all of them, and the current system of ignoring population and seeking solutions to problems such as pollution in tackling secondary causes (e.g. global warming) is to evade the real challenge.

Heinsohn’s message about war can be summed up thus: “It’s population, stupid.”

A table on pages 120-127 highlights a remarkably regular congruence between nations where armed conflict dominates and/or the murder rate is higher than the global average, and nations with an above-average youth/children bulge. In fact, Heinsohn can find very few conflicts, widespread acts of terrorism, high crime rates, or acts of genocide which do not find their origin one way or another in the struggle of a youth bulge cohort to obtain their Eigentumsprämie.

This leads to the deeply pessimistic conclusion that populations without youth bulges — those either with declining birth rates or which achieve an equilibrium of births to deaths, a picture of stability — will be considerably more pacifistic than societies with a youth bulge, but such societies are victims waiting to be discovered. History would seem to bear this out: Societies with stable populations do seem to be more pacifistic than those with growing populations, and therefore more likely to fall victim to them. The Indians of the Caribbean falling victim to the Europeans or the Bushmen falling victim to the Bantu are obvious cases that come to mind. It seems to be that all human societies are condemned to take part in a sort of cradle race to outbreed and thereby dominate one another. Irish nationalists have long been aware of the population factor in overcoming Protestant and British rule and uniting Ireland, although they remain willfully ignorant of the cradle challenge Ireland is itself now facing from Black immigrants.

Söhne und Weltmacht may be criticized for being less than systematic in the development of its argument. The argument is based not so much on theory or a model of society as evidence. Historical cases accompanied by tables are presented to the reader and thereafter evidence is cited to show the validity of the argument, but the theory is not examined in depth, nor are contrary interpretations of the cause of war and terrorism examined at all. Heinsohn is saying in effect that the “coincidence” of correlation between youth bulge and war is so overwhelming that it would be the onus of a skeptic to provide an alternative interpretation.

The evidence of what Heinsohn is claiming is plentiful and strong. The reader may be forgiven for wondering why the argument has not been put forward previously, or even debated previously, if it is all so obvious. Heinsohn says (and here we are with Malthus again) that in societies or countries with soaring birth rates, there will be too few prestigious positions (defined in terms of property right) to content aspiring male youth, too little opportunity to devote energy to worthwhile enterprises, there will be diminishing resources available to rising numbers of young men, and that will lead to internal conflict over the scarce resources or emigration or both. It is not that favorite explanation offered by NGO charities, a “poverty trap,” which triggers mass emigration.

Against the belief that low living standards are the prime force prompting conflict, Heinsohn notes that the standard of living of the Ivory Coast, for example, was rising before it entered into its main period of conflict — in fact, the standard of living actually declined as a result of civil war. Conflicts negatively affect standards of living, and it is not poverty alone which causes conflict, so Heinsohn. Conflict, he argues, is caused by rising expectations that cannot be met fast enough.

Heinsohn also looks at the expansion and global dominance of Europe from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century. When Europe’s expansion began at the very end of the fifteenth century, the population was, as a result of widespread pestilence, actually lower than it had been previously (60 million in 1500 compared to 90 million in 1340). What took place was not a simple increase in total population compared to the past, but a dramatic change in the median age of European populations. Large numbers of children were growing up without prospects. It was not only or even principally acres which were not available, but prestige and ownership (Eigentumsprämie). Heinsohn is at pains to argue that this is not simply a matter of “Lebensraum“. He also ignores those cases where expansion or migration will be more convincingly interpreted as just that: diminishing living space under the pressure of rising population. Ireland and Germany in the nineteenth century would be obvious cases, and after the Great Famine, the Irish emigrated out of economic compulsion. Even here, however, it is certainly the case that the plight of the Irish was more perilous because of their high fertility at the time of the Great Famine.

Another highly interesting factor highlighted in this book is the notion of the sanctity of life. From the end of the Roman Empire to the sixteenth century, Europe did not experience a dramatic increase in population nor did it experience a birth rate anything like as high as that which began suddenly at the end of the fifteenth century and continued down to the twentieth century. What had happened? According to Heinsohn, the notion of the “sanctity of life” and hostility towards contraception, infanticide, and abortion of an intensity not seen since the days of Rome (but highly characteristic of Islamic society) began at the end of the fifteenth century — and it is at the end of the fifteenth century that Europe set out on a course of world conquest. The writer refers to well-documented evidence from several English counties. On the basis of this evidence, between 1441 and 1465, 100 fathers were leaving 110 surviving sons. Between 1491 and 1505 a dramatic change had taken place: 100 fathers were leaving behind them 202 surviving sons. By the nineteenth century, between 5 and 6.5 children per mother were being raised in Europe, a rate only reached in the last century by twenty-four states in Sub-Saharan Africa and Afghanistan.

Another highly interesting factor highlighted in this book is the notion of the sanctity of life. From the end of the Roman Empire to the sixteenth century, Europe did not experience a dramatic increase in population nor did it experience a birth rate anything like as high as that which began suddenly at the end of the fifteenth century and continued down to the twentieth century. What had happened? According to Heinsohn, the notion of the “sanctity of life” and hostility towards contraception, infanticide, and abortion of an intensity not seen since the days of Rome (but highly characteristic of Islamic society) began at the end of the fifteenth century — and it is at the end of the fifteenth century that Europe set out on a course of world conquest. The writer refers to well-documented evidence from several English counties. On the basis of this evidence, between 1441 and 1465, 100 fathers were leaving 110 surviving sons. Between 1491 and 1505 a dramatic change had taken place: 100 fathers were leaving behind them 202 surviving sons. By the nineteenth century, between 5 and 6.5 children per mother were being raised in Europe, a rate only reached in the last century by twenty-four states in Sub-Saharan Africa and Afghanistan.

At exactly the same time as the hike in the European birth rate, the great witch hunts and trials began, which were to cost the lives of up to 100,000 women. Experts are at a loss to explain the ferocity, extent, and above all, suddenness of the persecution of witches. Heinsohn offers a fascinating and persuasive interpretation. Many observers have pointed out the connection between fear and hatred of witches and rumors of infanticide and other “ungodly” practices by midwives. In Heinsohn’s interpretation, the target of the persecution of witches was in large part an assault on the medical knowledge which midwives possessed and utilized, including knowledge relating to contraception and birth control. The witch trials, in Heinsohn’s thought-provoking interpretation, were first and foremost an assault on nature-based science by a Church and state whose new piety sought to extirpate all activity which could prevent human reproduction. It may be that neither Church nor State were consciously promoting a population surge, but that is the effective result of their measures. Consciously induced or unconsciously, the fact remains, cited by Heinsohn, that between 1000 and 1500 two to three women were being born per woman and after 1500 that figure rose abruptly to 5-7 children (p. 14).

In 1484, Innocent VIII issued his famous Bull against contraception, and a condemnation of contraception has been characteristic of the Roman Catholic faith ever since. Contraception and abortion were subject to capital laws. “Witches” were closely associated with those who sought to provide women with the means to exercise birth control. The persecution of witches, by Protestant and Catholic alike, was the assertion of the will to “go forth and multiply.” All sexual pleasure which was not conducted under the bonds of holy matrimony and for the purposes of reproduction was condemned as sinful and often punishable by death.

Heinsohn does not state but strongly implies that were it not for the opportunities offered in the nineteenth century for expansion and relief of the youth bulge by means of colonial expansion and deportation, the nineteenth century would not have been the relatively peaceful century for Europe that it became. The colonies were a release valve. By 1914, there were no more lands to colonize. In the twentieth century, European countries including Russia had cannon fodder at home to spend. Heinsohn’s system and message are emphatic and coldly cynical:

It was the strictly enforced penalties for birth control which can explain the fact that regardless of all emigration, wars, epidemics and high infant mortality, the European population explosion in this time did not once let up, reaching (with Russia) nearly 500 million by 1915 and it could afford the cannon fodder of 8 million in the Great War. After the Second World War, the Western powers continued to build the most deadly weapons but could no longer raise enough sons. This, along with the threat of assured mutual destruction through nuclear war, and not any supposed process of increased sensitivity and scrupulousness, is the not very noble reason why the numbers of Europeans dead in battle has fallen so low. (p. 150)

Hans Grimm’s Volk ohne Raum, a novel written in 1926 which portrayed Germany as a country suffering from overpopulation and therefore a lack of living space (Lebensraum) accords entirely with Heinsohn’s thesis. Once it was Europe’s turn. Now it is the turn of non-European peoples with great youth bulges, warring against one another and seeking their fortunes in other lands, especially when in those lands, the indigenous population cannot challenge them with expendable sons of its own. The bitter truth, argues Heinsohn, is that societies with high youth bulges can — in terms of human material — literally afford to go to war. Islamic martyrs nearly always possess siblings to mourn their passing and to swear revenge. If there were a white resistance movement with the same resolution and determination to die for its cause in martyrdom, there would nevertheless be no brothers to mourn and swear revenge for the fallen. In numbers is strength. Heinsohn is serving up an old socialist truism here, but it is one that needs to be restated. Many people have lost sight of it in efforts to obfuscate the challenge of the ambitious millions of the world with humanist hand ringing about the calamity of war. The success of the white race in conquering the world was not, according to Heinsohn, due to racial superiority, as Gobineau among many other racial supremacy theorists have argued. European world domination was maintained and caused by its youth bulge. (p. 153)

Heinsohn does not pretend that a youth bulge alone explains the expansionist or imperialist development of any people, but he claims that a youth bulge is a precondition for such a development. If his argument is correct, then the white race can offer no effective policy for its own survival in the face of expansionist challenges without a reproductive riposte commensurate to that of Islamic or African migrants. This is not only for the obvious reason of numbers and proportional weight of influence, but also by virtue of the fact that according to Heinsohn, no group of people is sociologically and perhaps not biologically triggered to expand or even seek conflict without the assurance that there are sufficient sons to take the place of those who fall in war.

It is worth noting the paradox that only does the white race have far fewer children per capita than other races, but those who are most conscious of the demographic decline and most readily deplore it themselves usually have few or no children at all.

It is worth noting the paradox that only does the white race have far fewer children per capita than other races, but those who are most conscious of the demographic decline and most readily deplore it themselves usually have few or no children at all.

Heinsohn’s book belongs to a long tradition of culturally pessimistic “realist” writings, which include Hobbes, Malthus, Spengler, and more recently Huntingdon and Rolf Peter Sieferle, whose Epochenwechsel I have reviewed for Counter-Currents. The core of Heinsohn’s argument is very simple and very persuasive. Towards the end of his book, which consists largely of cases of conflict which can be explained by his theory and tables to illustrate those cases, he notes: “If Germany had increased its population between 1950 and 2020 at the same rate as The Gaza strip, (0.2-2 million), it would not have a population of 83 million today, but 700 million, and 90 million of those would be between 15 and 29 years old.” (p. 231)

There is nothing original in stating that wars can be won through the cradle, but Heinsohn goes further. He argues that all wars are caused by the cradle. He posits no conspiracy (the book is without so much as a hint of a conspiracy). However, politicians do blatantly, as in the case of President Erdogan of Turkey, call for the mothers of the homeland to be fruitful and have many children as a duty to the nation. Ho Chi Minh (quoted by Heinsohn) famously boasted that he would defeat the French because Vietnam had more sons ready for sacrifice than France had. France’s war index at the end of the Second World War was 1.6, meaning that for 1000 men between 55 and 59 there were 1600 young men between 15 and 19, but on the Vietnamese side there were 3000, twice as many. With a war index of 3, Vietnam enjoyed the advantage of being able to draw on a far larger supply of human beings to sacrifice (p. 28).

Heinsohn does not make clear the extent to which youth bulges are created intentionally and I would have appreciated an examination of this point. Was, for example, the Church with its edicts against homosexuality,

infanticide, and contraception, consciously seeking to boost the population, or was this the incidental consequence of measures which had other motivations? Heinsohn would probably say that it is not important to know. He certainly implies with his description of the anti-contraceptive mores and laws of Europe (surprisingly and disappointingly, he spends comparatively little time in discussing similar edicts and laws in Islamic countries) that higher fertility is increased through the express design of religious and political leaders, but he also notes several times the role played by medical discovery and improved hygiene in lowering infant mortality.

Europeans have played the major, if not exclusive, role in boosting Africa’s population, first by medical and prophylactic intervention and care and second by the import of religious strictures and penalties against non-reproductive sexual activity — strictures which, in the meantime, have been widely rejected by more liberal and religiously skeptical European populations. There are measures which undoubtedly have nothing to do with the express wish for any increase in population, but which will nevertheless have exactly that effect; another example is the legalization of abortion in Japan in 1949. (Heinsohn refers to abortion in this book, somewhat misleadingly and presumably for reasons of his own belief, as “infanticide”.)

While Heinsohn writes about various triggers that cause youth bulges, he has little to say about what prevents them or reduces them. It seems that they slow down when the demands of youth are satisfied and where having children is an impediment to career advancement instead of an investment in the future. What, exactly, is it that the superfluous sons of a youth bulge desperately seek and go to war in order to obtain? Here our writer becomes — at least to this reviewer’s thinking — a trifle obscure and difficult to follow. What the superfluous sons of the youth bulge seek, already mentioned in this review, is what Heinsohn calls Eigentumsprämie. This word is not easy to translate into English, all the more as it is a word of Heinsohn’s own invention! It may be translated as “ownership (or title-holding) preference” or “ownership benefit.” Keynes’ “Liquidity Preference” comes to mind, a term which is commonly rendered in German as Liquiditätsprämie. For Heinsohn, the difference between ownership of property (Eigentum) and possession (Besitz) is crucial to an understanding of the motivation of the young men who fight in wars. He relies on a thesis expounded in another of his works: Eigentum, Zins, und Geld (Ownership, Interest, and Money) which holds that a concept of ownership precedes trade and is a precondition of trade and of the need for a token to denote ownership, namely money. Whatever they may formally possess, young men in any society seek ownership in order to establish themselves.

It is fourteen years since the renowned philosopher Peter Sloterdijk opined enthusiastically in the pages of the Kölner Stadt Anzeiger that Söhne und Weltmacht would become required reading for politicians and journalists. His prediction has not been fulfilled, and this new and updated edition has been published by a small Swiss imprint. The fact is that books like Söhne und Weltmacht cannot expect to receive much attention from journalists or politicians. They point to truths which the presently-dominating ideology is loathe to review or discuss.

It is fourteen years since the renowned philosopher Peter Sloterdijk opined enthusiastically in the pages of the Kölner Stadt Anzeiger that Söhne und Weltmacht would become required reading for politicians and journalists. His prediction has not been fulfilled, and this new and updated edition has been published by a small Swiss imprint. The fact is that books like Söhne und Weltmacht cannot expect to receive much attention from journalists or politicians. They point to truths which the presently-dominating ideology is loathe to review or discuss.

Gunnar Heinsohn focuses on population increase as a key to understanding the world and believes that it is in population hikes that we will find an explanation for many of the woes of the modern world. The title of one chapter of this book, “Africa’s banner of victory: reproduction,” is worth a score of soul-searching mainstream talk shows. Millions without perspective are ready to die to obtain respect and standing in the world. If they cannot do so, they readily grasp violence, not out of need, religious piety, or political orthodoxy, but out of deep internal compulsion. The project of this book is to show the reader what that means and has always meant for human beings in real terms.

It is a pity that Peter Sloterdijk was wrong.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Le grand projet rooseveltien était d’américaniser la production agricole et industrielle et de faire de la planète un grand marché – l’URSS étant exclue, qui devait servir de repoussoir, de contre-exemple, au moins pour les premiers temps de l’ère du « One World–One Government ». Qu’il ait ou non développé le projet d’une fusion des races et des peuples en une « moyenne humaine », on ne le saura jamais, car Roosevelt ne s’est guère exprimé sur ce point... là encore, les complotistes vont un peu vite en besogne.

Le grand projet rooseveltien était d’américaniser la production agricole et industrielle et de faire de la planète un grand marché – l’URSS étant exclue, qui devait servir de repoussoir, de contre-exemple, au moins pour les premiers temps de l’ère du « One World–One Government ». Qu’il ait ou non développé le projet d’une fusion des races et des peuples en une « moyenne humaine », on ne le saura jamais, car Roosevelt ne s’est guère exprimé sur ce point... là encore, les complotistes vont un peu vite en besogne.

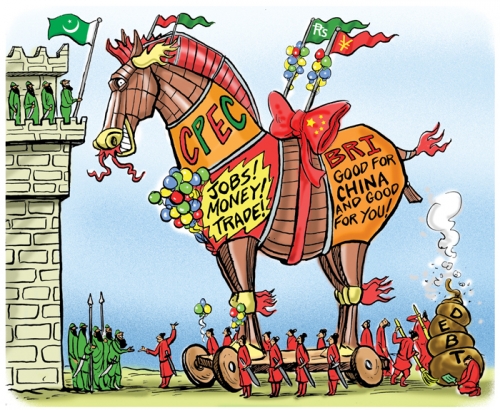

La transformation de la mondialisation pourrait même être analysée, non pas à la lumière du mouvement de globalisation entamée après la chute du mur de Berlin, mais plutôt à travers une histoire continue qui débuterait à l’époque des grandes découvertes et de la Compagnie des Indes orientales. Fernand Braudel l’a magistralement analysé dans « La Dynamique du capitalisme », en décrivant l’économie-monde avec son centre, dont découlent tous les échanges : « Le soleil de l’histoire fait briller les plus vives couleurs, là que se manifestent les hauts prix, les hauts salaires, la banque, les marchandises royales, les industries profitables, les agricultures capitalistes ; là que se situent le point de départ et le point d’arrivée des longs trafics, l’afflux des métaux précieux, des monnaies fortes et des titres de crédit. »

La transformation de la mondialisation pourrait même être analysée, non pas à la lumière du mouvement de globalisation entamée après la chute du mur de Berlin, mais plutôt à travers une histoire continue qui débuterait à l’époque des grandes découvertes et de la Compagnie des Indes orientales. Fernand Braudel l’a magistralement analysé dans « La Dynamique du capitalisme », en décrivant l’économie-monde avec son centre, dont découlent tous les échanges : « Le soleil de l’histoire fait briller les plus vives couleurs, là que se manifestent les hauts prix, les hauts salaires, la banque, les marchandises royales, les industries profitables, les agricultures capitalistes ; là que se situent le point de départ et le point d’arrivée des longs trafics, l’afflux des métaux précieux, des monnaies fortes et des titres de crédit. »

Robert Malthus’s essay on population growth is widely known and widely refuted, mostly by commentators who have not read it. In his Essay on the Principle of Population, Malthus argued that population growth undermined the achievements which technology had brought and was bringing to human society and ironically had first made that population growth possible. Populations, he wrote, increased faster than the rate of increase in food production necessary to keep pace with the demand for more food. According to Malthus, this discrepancy between supply and demand would lead inevitably to a decline in living standards and to famine. That Malthus’s prediction proved (broadly) not to be the case in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is largely due to the fact that human societies have vastly improved agricultural efficiency and available agricultural land far in excess of the slow growth in food production which Malthus had projected. This improvement in food production to meet the demands of growing populations could only be achieved, and was only achieved, by improved logistics, improved science, and exploiting nature — not only more efficiently, but also more extensively. The fear of famine and outbreaks of famine have continued down to the present day, however, and although Malthus is officially repudiated, his ghost has not been lain to rest. The burden put upon nature incurred by meeting the challenge of the appetites of the human population increase continues to this day. Has Malthus been proved entirely wrong, and is his thesis applicable in relation to challenges other than that of famine?

Robert Malthus’s essay on population growth is widely known and widely refuted, mostly by commentators who have not read it. In his Essay on the Principle of Population, Malthus argued that population growth undermined the achievements which technology had brought and was bringing to human society and ironically had first made that population growth possible. Populations, he wrote, increased faster than the rate of increase in food production necessary to keep pace with the demand for more food. According to Malthus, this discrepancy between supply and demand would lead inevitably to a decline in living standards and to famine. That Malthus’s prediction proved (broadly) not to be the case in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is largely due to the fact that human societies have vastly improved agricultural efficiency and available agricultural land far in excess of the slow growth in food production which Malthus had projected. This improvement in food production to meet the demands of growing populations could only be achieved, and was only achieved, by improved logistics, improved science, and exploiting nature — not only more efficiently, but also more extensively. The fear of famine and outbreaks of famine have continued down to the present day, however, and although Malthus is officially repudiated, his ghost has not been lain to rest. The burden put upon nature incurred by meeting the challenge of the appetites of the human population increase continues to this day. Has Malthus been proved entirely wrong, and is his thesis applicable in relation to challenges other than that of famine?

Another highly interesting factor highlighted in this book is the notion of the sanctity of life. From the end of the Roman Empire to the sixteenth century, Europe did not experience a dramatic increase in population nor did it experience a birth rate anything like as high as that which began suddenly at the end of the fifteenth century and continued down to the twentieth century. What had happened? According to Heinsohn, the notion of the “sanctity of life” and hostility towards contraception, infanticide, and abortion of an intensity not seen since the days of Rome (but highly characteristic of Islamic society) began at the end of the fifteenth century — and it is at the end of the fifteenth century that Europe set out on a course of world conquest. The writer refers to well-documented evidence from several English counties. On the basis of this evidence, between 1441 and 1465, 100 fathers were leaving 110 surviving sons. Between 1491 and 1505 a dramatic change had taken place: 100 fathers were leaving behind them 202 surviving sons. By the nineteenth century, between 5 and 6.5 children per mother were being raised in Europe, a rate only reached in the last century by twenty-four states in Sub-Saharan Africa and Afghanistan.

Another highly interesting factor highlighted in this book is the notion of the sanctity of life. From the end of the Roman Empire to the sixteenth century, Europe did not experience a dramatic increase in population nor did it experience a birth rate anything like as high as that which began suddenly at the end of the fifteenth century and continued down to the twentieth century. What had happened? According to Heinsohn, the notion of the “sanctity of life” and hostility towards contraception, infanticide, and abortion of an intensity not seen since the days of Rome (but highly characteristic of Islamic society) began at the end of the fifteenth century — and it is at the end of the fifteenth century that Europe set out on a course of world conquest. The writer refers to well-documented evidence from several English counties. On the basis of this evidence, between 1441 and 1465, 100 fathers were leaving 110 surviving sons. Between 1491 and 1505 a dramatic change had taken place: 100 fathers were leaving behind them 202 surviving sons. By the nineteenth century, between 5 and 6.5 children per mother were being raised in Europe, a rate only reached in the last century by twenty-four states in Sub-Saharan Africa and Afghanistan. It is worth noting the paradox that only does the white race have far fewer children per capita than other races, but those who are most conscious of the demographic decline and most readily deplore it themselves usually have few or no children at all.

It is worth noting the paradox that only does the white race have far fewer children per capita than other races, but those who are most conscious of the demographic decline and most readily deplore it themselves usually have few or no children at all. It is fourteen years since the renowned philosopher Peter Sloterdijk opined enthusiastically in the pages of the Kölner Stadt Anzeiger that Söhne und Weltmacht would become required reading for politicians and journalists. His prediction has not been fulfilled, and this new and updated edition has been published by a small Swiss imprint. The fact is that books like Söhne und Weltmacht cannot expect to receive much attention from journalists or politicians. They point to truths which the presently-dominating ideology is loathe to review or discuss.

It is fourteen years since the renowned philosopher Peter Sloterdijk opined enthusiastically in the pages of the Kölner Stadt Anzeiger that Söhne und Weltmacht would become required reading for politicians and journalists. His prediction has not been fulfilled, and this new and updated edition has been published by a small Swiss imprint. The fact is that books like Söhne und Weltmacht cannot expect to receive much attention from journalists or politicians. They point to truths which the presently-dominating ideology is loathe to review or discuss.

L’Argent, puisqu’il est parlé du bourgeois que Valois substantifie en quelque sorte en lui accordant, comme au métal précieux d’ailleurs, une majuscule, est le thème sous-jacent de notre livre et on peut sans trop craindre de se tromper affirmer qu’il est, comme la

L’Argent, puisqu’il est parlé du bourgeois que Valois substantifie en quelque sorte en lui accordant, comme au métal précieux d’ailleurs, une majuscule, est le thème sous-jacent de notre livre et on peut sans trop craindre de se tromper affirmer qu’il est, comme la

He earned fame in Berlin, where he became a hero of the international artistic community. It was in Berlin that he published his resonant essay "Zur Psychologie des Individuums. I - Chopin und Nietzsche. II - Ola Hansson" 1892 as well as poems Totenmesse, 1895 (Polish version: Requiem aeternam, 1904), Vigilien, 1895 (Polish version: Z cyklu wigilii, 1899), De profundis, 1895 (Polish version 1900), Androgyne, 1900. They introduced themes which would be central to all of his work: individualism, the metaphysical and social status of creative individuals, fate of geniuses, the sense of such attributes of genius as "degeneration" and "illness". He continued to present his philosophical views in essays published in a number of magazines and later collected in the volumes "Auf den Wegen der Seele" 1897 ("Na drogach duszy" [On the Paths of the Soul], 1900), "Szlakiem duszy polskiej" [On the Paths of the Polish Soul], 1917, "Ekspresjonizm, Słowacki i Genesis z ducha" [Expressionism, Slowacki and Genesis from the Spirit], 1918.

He earned fame in Berlin, where he became a hero of the international artistic community. It was in Berlin that he published his resonant essay "Zur Psychologie des Individuums. I - Chopin und Nietzsche. II - Ola Hansson" 1892 as well as poems Totenmesse, 1895 (Polish version: Requiem aeternam, 1904), Vigilien, 1895 (Polish version: Z cyklu wigilii, 1899), De profundis, 1895 (Polish version 1900), Androgyne, 1900. They introduced themes which would be central to all of his work: individualism, the metaphysical and social status of creative individuals, fate of geniuses, the sense of such attributes of genius as "degeneration" and "illness". He continued to present his philosophical views in essays published in a number of magazines and later collected in the volumes "Auf den Wegen der Seele" 1897 ("Na drogach duszy" [On the Paths of the Soul], 1900), "Szlakiem duszy polskiej" [On the Paths of the Polish Soul], 1917, "Ekspresjonizm, Słowacki i Genesis z ducha" [Expressionism, Slowacki and Genesis from the Spirit], 1918. Przybyszewski translated the philosophical issues raised in his essays and narrative poems into the language of literary prose and drama. A very prolific writer, he published many novels, all of them trilogies, in German and Polish, notably Homo Sapiens, German edition 1895-96, Polish edition. 1901; Satans Kinder, 1897; Synowie ziemi [Sons of the Earth], 1904-11; Dzieci nędzy [Children of Poverty], 1913-14; Krzyk [The Cry], 1917; Il Regno Doloroso, 1924. All of his novels had basically the same type of protagonists, i.e. outstanding individuals destroyed by the social world and by their internal demons. These doomed characters were presented in extreme, frequently pathological, emotional states of alcoholism, jealousy, destructive love. The plots were weak and served as a pretext to analyze the characters' internal states. This new type of the protagonist required appropriate narration techniques that were different from those used in realistic novels. Przybyszewski made innovative use of (seemingly) indirect speech and of internal monologue.

Przybyszewski translated the philosophical issues raised in his essays and narrative poems into the language of literary prose and drama. A very prolific writer, he published many novels, all of them trilogies, in German and Polish, notably Homo Sapiens, German edition 1895-96, Polish edition. 1901; Satans Kinder, 1897; Synowie ziemi [Sons of the Earth], 1904-11; Dzieci nędzy [Children of Poverty], 1913-14; Krzyk [The Cry], 1917; Il Regno Doloroso, 1924. All of his novels had basically the same type of protagonists, i.e. outstanding individuals destroyed by the social world and by their internal demons. These doomed characters were presented in extreme, frequently pathological, emotional states of alcoholism, jealousy, destructive love. The plots were weak and served as a pretext to analyze the characters' internal states. This new type of the protagonist required appropriate narration techniques that were different from those used in realistic novels. Przybyszewski made innovative use of (seemingly) indirect speech and of internal monologue.

MOYEN(S) UTILISÉ(S) :

MOYEN(S) UTILISÉ(S) :

![ineptocracie_thumb[2].png](http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/media/01/02/1259712049.png)