Historian of the Future:

An Introduction to Oswald Spengler’s Life and Works

for the Curious Passer-by and the Interested Student

By Stephen M. Borthwick

Ex: https://europeanheathenfront.wordpress.com

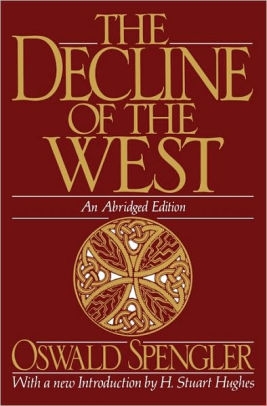

There have been two resurgences in the popularity of Oswald Spengler since the initial blooming of his popularity in the 1920s; the first in the 1980s and the second most recently, with almost ten major books dealing directly with him or his thought published in the last ten years, and more articles in various academic journals. It is a resurgence in the popular mind that may yet be matched in the academy, where Spengler has hardly been obscure but nevertheless an unknown—a forbidden intellectual fruit for what was, in the words of Henry Stuart Hughes, his first English-language biographer, “obviously not a respectable performance from the standpoint of scholarship” calling Decline of the West, in form typical to Hughes’ species “a massive stumbling block in the path to true knowledge”.[1] This is a pervasive attitude amongst academics, whose fields, especially history, are dominated by a specialisation that Spengler’s history defies with its broad perspective and positivist influences. As such when Spengler’s magnum opus first appeared, it was immediately subject to what in popular parlance can only qualify as nit-picking, which did not cease when the author corrected what factual errors could be found in his initial text. Nevertheless, in the popular mind Spengler has remained an influential if obscure author. Most recently, his unique, isolated civilisations encapsulated in their own history has been observed in Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order, though the development of civilisations from Mediterranean to Western that he paints resembles the dominant theory posited by William McNeill in his Rise of the West rather than Spengler’s Decline of the West. Nevertheless, Spengler’s theory of encapsulated cultural organisms growing up next to one another, advanced by subsequent authors like Toynbee, remains a stirring line of thought, growing more relevant in the rising conflict between Western countries and the resurging Islamic world.

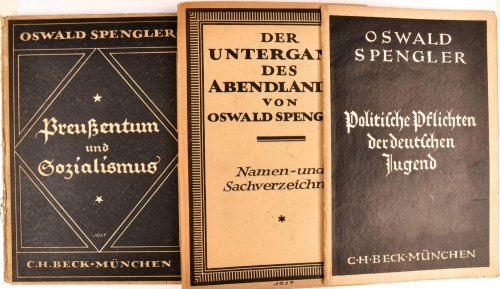

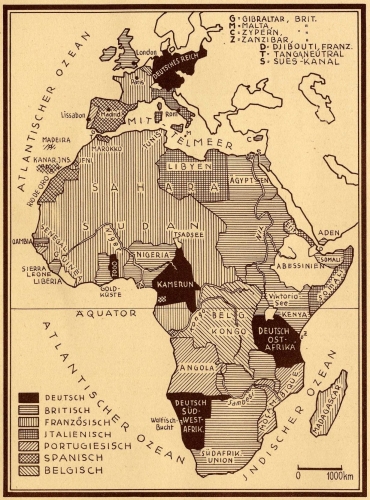

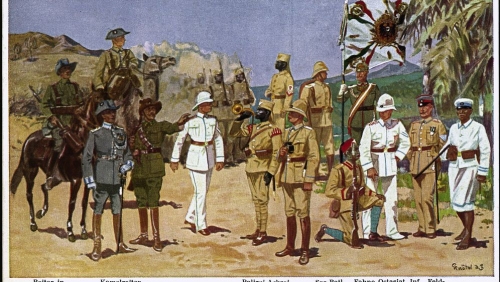

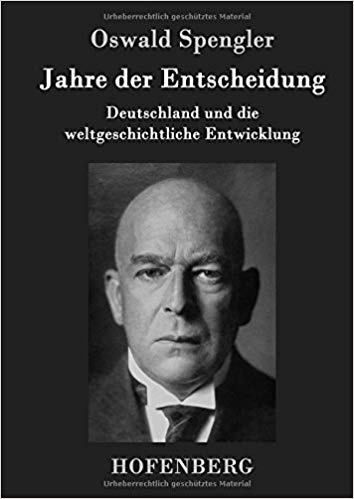

T o understand this adversity that Spengler’s ideas struggle against in the academic establishment, and therefore to know why his ideas have filtered through the decades but left his name and book behind, it is necessary to do what very few academics dare to do: to explore and openly discuss the significance of Spengler’s thought. This is the project of this essay; to explain to any who have recently discovered Spengler, especially if they are a college student or college graduate, why they have never heard the name “Spengler” before, and what his thought entails at its most basic level. This discussion will deal not just with Spengler’s most famous work, Der Untergang des Abendlandes (“The Downfall of the Occident”, popularly known as Decline of the West, after C.F. Atkinson’s translation) but also with his numerous political pamphlets and subsequent works of philosophy and history. His philosophical texts include, chiefly: Man and Technics, a specialised focus expanding on the relationship of the human being and the age of technology in which we live already mentioned in Decline, The Hour of Decision, which foresees the overthrow of the Western world by what today would be called the “Third World”, or what Spengler refers to as the “Coloured World”, and Prussianism and Socialism, his first major political text, prescribing the exact form of political structure needed, in his view, to save Germany immediately after the First World War. Numerous other texts, published by C.H. Beck in Munich, also exist, compiled in two primary collections, Politischen Schriften (“Political Writings”) of 1934 and posthumous Reden und Aufsätze (“Speeches and Essays”) of 1936; these are joined by Gedanken (“Reflections”), also of 1936. His unfinished works, posthumously collected and titled by chief Spengler scholar Anton Koktanek in the 1960s, Urfragen and Frühzeit der Weltgeschichte, will not be touched upon in this brief introduction, since they are not available in the English language, but readers fluent in German are encouraged to explore them as well as Koktanek’s other works.

o understand this adversity that Spengler’s ideas struggle against in the academic establishment, and therefore to know why his ideas have filtered through the decades but left his name and book behind, it is necessary to do what very few academics dare to do: to explore and openly discuss the significance of Spengler’s thought. This is the project of this essay; to explain to any who have recently discovered Spengler, especially if they are a college student or college graduate, why they have never heard the name “Spengler” before, and what his thought entails at its most basic level. This discussion will deal not just with Spengler’s most famous work, Der Untergang des Abendlandes (“The Downfall of the Occident”, popularly known as Decline of the West, after C.F. Atkinson’s translation) but also with his numerous political pamphlets and subsequent works of philosophy and history. His philosophical texts include, chiefly: Man and Technics, a specialised focus expanding on the relationship of the human being and the age of technology in which we live already mentioned in Decline, The Hour of Decision, which foresees the overthrow of the Western world by what today would be called the “Third World”, or what Spengler refers to as the “Coloured World”, and Prussianism and Socialism, his first major political text, prescribing the exact form of political structure needed, in his view, to save Germany immediately after the First World War. Numerous other texts, published by C.H. Beck in Munich, also exist, compiled in two primary collections, Politischen Schriften (“Political Writings”) of 1934 and posthumous Reden und Aufsätze (“Speeches and Essays”) of 1936; these are joined by Gedanken (“Reflections”), also of 1936. His unfinished works, posthumously collected and titled by chief Spengler scholar Anton Koktanek in the 1960s, Urfragen and Frühzeit der Weltgeschichte, will not be touched upon in this brief introduction, since they are not available in the English language, but readers fluent in German are encouraged to explore them as well as Koktanek’s other works.

On the assumption that without understanding a man, one cannot grasp his thought, it seems most appropriate to begin any exploration of Spengler the philosopher with Spengler the man. Spengler was a conservative first, then a German nationalist, then a pessimist (though he regarded himself as a consummate realist). Further, he was one of the few men (if not the only man) to meet Adolf Hitler and come away completely unmoved by the demagogue and future dictator of Germany. He openly attacked National Socialism as “the tendency not to want to see and master sober reality, but instead to conceal it with... a party-theatre of flags, parades, and uniforms and to fake hard facts with theories and programmes” and declared that what Germany needed was “a hero, not merely a heroic tenor.”[2] Nevertheless, when voting in the 1932 elections, Spengler, along with some 13.5 million other Germans, cast his ballot for the National Socialist ticket; he explained his choice to friends by saying enigmatically “Hitler is an idiot—but one must support the movement.”[3] At the time people speculated what he meant, and have subsequently continued to speculate to what he was referring when he said “the movement”, especially after his sustained criticisms of National Socialism well into what other Germans were experiencing as “the German Rebirth” in the years between 1933 and his death in 1936.

Spengler’s sustained pessimism about the National Socialist future (he remarked sarcastically shortly before his death that “in ten years the German Reich will probably no longer exist”) is reflective of a realism he had well before the beginning of the First World War, when the idea that would become Decline of the West were first conceived shortly after the Agadir crisis in 1911. Spengler lived and wrote largely in unhappy times; his chief contributions were made in Germany’s darkest hours of the interwar period, dominated by an unstable, incompetent government, extraordinary tributes exacted by the victorious allies, and as a result unrivalled poverty, inflation, and unemployment while the former Allied Powers (save for Italy) were experiencing the so-called “Roaring ‘20s”. He was born and he died, however, in times when things were looking bright. Few regular Germans in 1936 could or did foresee the barbarity of Hitler’s reign, five gruelling years of World War and the planned extermination of non-“Aryans” in conquered territories as well as at home, just as Wilhelmine Germany was oblivious to the consequences of the First World War almost right through it. All that the Germans saw was Germany, their Germany, was on the rise! In 1880, when the young Oswald was born to Bernhard Spengler and his wife Pauline, the German Empire was led by Kaiser Wilhelm I and his Iron Chancellor Bismarck, and the German Reich was still celebrating its formation and the unification of the German nation. Aside from the tribulation of the “year of three emperors” when the young Oswald was eight, there was no reason for the average German to worry about catastrophe: the kindly old Kaiser Wilhelm was replaced by his young, virulent grandson, Wilhelm II, who promised his people “a place in the Sun”. Later, in 1936, when the now established scholar died in his sleep of a heart-attack, the German people were again in good spirits; from the popular perspective, all they could see was that they at last had jobs again, inflation no longer loomed as so painful a memory, their shattered Reich was being rebuilt, and someone had finally reasserted German control over the Rhineland and the Saar—where the memory of the insulting use of colonial occupation forces by the French, and the various abuses civilians suffered during the occupation, still lingered in the German mind.

Early Life (From Youth to Decline, 1880-1917)

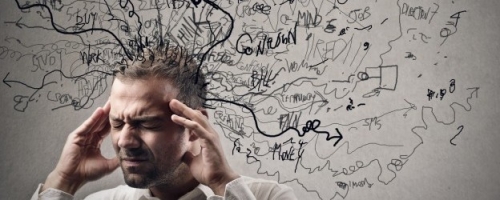

All of this blithe cheerfulness and celebration, though, did not affect either the young or the old Oswald Spengler. The opening chapter of Koktanek’s biography of him is titled “Ursprung und Urangst” – “Origin and Original Anxiety”, and not without good reason. Throughout his life, Spengler suffered a nervous affliction and anxiety, leading to chronic headaches in later years so bad that they caused minor short-term memory loss. He would later reflect in his planned autobiography that in his youth he had “no friends, with one exception, [and] no love: a few sudden, stupid [infatuations], fearful of the bond [of relationship]. [I had] only yearning and melancholy.”[4] His home life was similarly dismal. John Farrenkopf characterises it as the typical bourgeois home of the period; his father, a former copper miner turned civil servant, was proud of the Fatherland, conservative in social attitudes, and generally took for granted his loyalty to the Prussian State. It was, in Spengler’s own eyes, a cold place, and an unhappy one. Spengler remarked that his parents were “unliterarisch”—“unlettered, unliterary”—and they “never opened our bookcase nor bought a book”; he himself developed an early love for reading, which earned him ire from his father, of whom he wrote was characterised by a “hatred for all recreation, most of all books”.[5] Despite his newspaper reading and bourgeois sensibilities, though, Bernhard Spengler rarely raised the topic of politics in the household, and young Oswald was only exposed to the workings of the State by outside influences. He would break from this aloofness of politics only once in his life, shrinking after his failure back into scholastic and theoretical efforts to influence the political climate.

Spengler’s mother led an unhappy life; she married Bernhard, it would seem, out of convenience rather than deep feeling, and bitter about her lot. Originally from the famous Grantzow clan of ballerinas and ballet masters, Pauline Spengler was prevented from ballet and the stage because of her figure, and then forced to leave her beloved home town, the quiet hamlet of Blanckenburg in the Harz mountains, for the bustling Hessian city of Halle-an-der-Saale when young Oswald was ten and her husband changed his trade from mining to postal work (a change he was not especially excited about, either). She displayed her dissatisfaction by brooding over her painting (an effort to cling to what artistry she could maintain in competition with her sisters) and playing petty tyrant over her children.

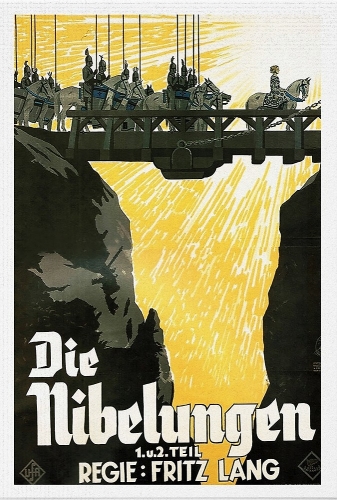

The young Spengler escaped this life through fantasy and fiction, inventing imaginary kingdoms and world-empires and writing childish theatre-plays with echoes of Wagner. He found further escape after he began his schooling at the Latina, administered by the Franckean Foundation in Halle, where he formally studied Greek and Latin, but in his free time devoured Goethe and Schiller, the first of literary influences that would later be joined by such eclectic writers as William Shakespeare, Gerhart Hauptmann, Henrik Ibsen, Maksim Gorky, Honoré de Balzac, Heinrich von Kleist, E.T.A. Hoffmann, Friedrich Hebbel, Heinrich Heine, Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Émile Zola, Gutave Flaubert, and others.[6] Spengler complained of the Franckean focus on Greek and Latin that prevented him from learning “practical languages”, and he was forced as a result to teach himself French, English, Italian, and, later, during his university days, Russian, through reading authors in those languages. His fluency in the languages was astounding to many, but he himself never felt comfortable enough with them to correspond with many of the authors he would later read and who would bring to bear influence on his own magnum opus in their own languages. Anton Koktanek blames this anxiety and lack of formal training in modern foreign languages for Spengler remaining “a German phenomenon”.[7]

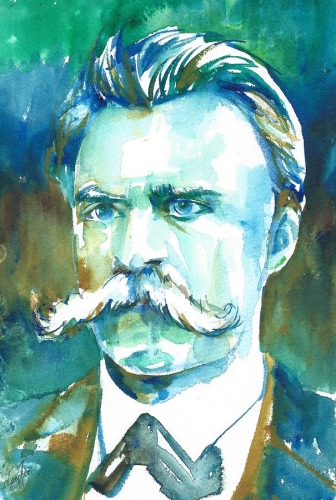

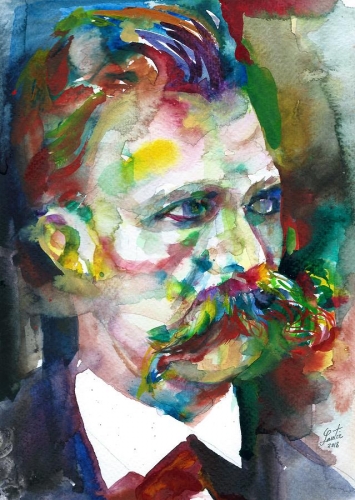

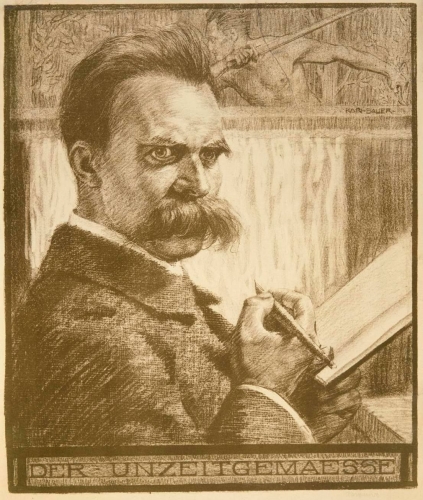

Spengler’s interest in world history and contemporary history also began here, and added to the fiction he wrote, including a short story set in the Russo-Japanese War titled Der Sieger as well as poetry, librettos, dramatic sketches, and other notes and such, most of which he would commit to the flames in 1911.[8] At University, he read the entirety of Goethe’s corpus and discovered two men who would bear tremendous influence on his later writing: Arthur Schopenhauer, and Friedrich Nietzsche. He would also become a devotee of Richard Wagner during this time, declaring his favourite work to be Tristan and Isolde.[9] His interest in Nietzsche especially would have great bearing on his choice of thesis topic, the pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus.

Spengler’s father died in 1901, just as Oswald was beginning University studies. He was by and large emotionally unaffected by the loss, and began all the more focusing on his studies. Like most students at University in those days, Spengler matriculated at several Universities while formally enrolled at the University of Halle. First, he travelled to Munich, a city with which he would fall in love and later make his home. Subsequently he would also study at the University of Berlin and then returned to Halle to complete his dissertation topic, entitled “Heraklit: eine Studie über den energetischen Grundgedanken seiner Philosophie” (“Heraclitus: A Study of the Energetic Fundamental Thought of his Philosophy”). It was, as Klaus Fischer observes, “a daring subject for a young scholar because Heraclitus had only left a few and highly cryptic fragments of his thought.”[10] Spengler, however, dared, and presented the first form of his thesis in 1903, but failed the oral defence. Despite his own typically depressed personality, however, he was not downtrodden at the failure; rather, he agreed with almost every criticism that was offered against his work—in his autobiography he called himself “naïve”. He had not, as most biographers observe, consulted any professors on his thesis before submitting it, and therefore had made errors and omissions that one only really avoids from consultation and discussion of one’s work.[11] The primary complaint was his lack of citations. He would repeat this mistake with the first edition of Decline of the West in 1917, writing the book entirely alone and isolated from the outside world—after initial criticism of the book he would revisit and largely revise the text, such that when it arrived in second edition in 1922 he had fixed most of his errors, but did not, as the academics insisted he should, increase the number of citations.

Spengler received his Ph.D. in 1904 and immediately went on to pass State examinations in a number of subjects that allowed him to become a Gymnasium teacher. His first assignment was a major turning point in his life, when he resolved not to be a teacher after stepping off the train in the little town of Lüneburg, taking a glance about at the town and the school and realising how terribly provincial his life would be. Spengler promptly boarded a train for his home town of Blankenburg and had a nervous breakdown. From this point forward he resolved to use teaching as a support for his true passions of study and writing. He recovered from his breakdown and took a different assignment, this time in Saarbrücken, happy to be so close to the French border that would allow him to take several holidays in France.[12] After a year there, he moved on to Düsseldorf, where he taught for another year before taking on a permanent (or so it appeared at the time) position in Hamburg.

Spengler flourished in these cities of big industry and metropolitan life—despite his writings criticising money power and the soul-stealing metropolis, Spengler remained a cosmopolitan urbanite throughout his life. An attestation to this aspect of his personality is his behaviour while teaching. Spengler remembered his days in the Franckean Latina with mixed disdain for the parochial moralists he had as teachers and gratitude for the training he received. He resolved, in the words of Klaus Fischer, “to avoid the foibles commonly attributed to schoolteachers: pedantry, narrow provincialism, and incivility” and made an effort to keep himself fully attuned to the petty culture of fashion and the latest advances in his scholarly fields (he taught German, mathematics, and geography). He would also frequent the theatre (where he would weep easily at especially moving plots and concertos) and local museums—in Düsseldorf he was even spotted frequently in the casino, a place quite foreign to most schoolteachers![13] His time in teaching, however, was short-lived. By almost all accounts Spengler hated Hamburg, not for itself, nor because he disliked the people, his colleagues or his students—indeed in all these respects he was well-respected and well-loved and returned these feelings of affection—but because of the weather. The cold, wet north German city terrorised him, increasing the acuteness and the frequency of his chronic headaches to such a degree that he took a year sabbatical in 1911 from which he would never return. His immediate plans were a holiday in Italy, where he would sojourn frequently in imitation of Goethe.[14]

His complete departure from teaching, much to the disappointment of both colleagues and students, who regarded him as a superlative teacher and amicable fellow, was by and large decided by his mother’s death in 1910. He had little regard for his mother, who psychologically tortured his sister Gertrude, disdained his other sister Hildegard, and was no kinder to his beloved sister Adele.[15] While he marked his father’s passing in 1901 with reflections of the latter’s loyalty to Prussia, his mother’s death was marked only with his inheritance and departure from his childhood home, leaving his sister Adele to dissolve the household.[16] Adele, a frustrated bohemian and largely talentless aspiring virtuoso, quickly spent the 30,000DM she inherited and committed suicide in 1917. Oswald’s inheritance, on the other hand, was wisely invested and used with some measure of thrift, giving him a comfortable lifestyle in Munich and allowing him to pursue his desire to be a writer.

At first, Spengler hadn’t the slightest idea what to write about. In Heraklit he displayed some of the budding thought which came to fruition as his magnum opus, to be sure. In one of the thicker sections of notes for Eis Heauton, the author proclaims that “my great book, Untergang des Abendlandes, was already emotionally conceived in my twentieth year” (four years before he would submit his doctoral thesis).[17] Farrenkopf observes that Spengler’s dissertation bears the marks of Decline as well, declaring that “what Spengler later attempted as a philosopher of history is analogous to what he claimed Heraclitus had accomplished in Greek philosophy”.[18] The true inspiration for Decline, however, came not from Heraclitus nor from Goethe or Nietzsche; nor did it come to him, as it did with Gibbon and Toynbee, from a physical visit to any landmarks. Rather, the genesis of Decline of the West was in a much different, political work titled Liberal and Conservative, which Spengler began writing in response to the Agadir Crisis of 1911.

Agadir, briefly put, was an attempt on the part of Kaiser Wilhelm II to imitate the American support of the Panamanian rebellion against Columbia, which was accomplished by placing the American fleet off the coast of Panama to prevent Columbian intervention. When Moroccans rebelled against the puppet Sultan Abdelhafid after years of allowing his country to be exploited by European powers, the French offered to support Fez by sending in troops. Wilhelm attempted to assert German interests in the region by sending the gunboat Panther to the harbour of Agadir, much to the chagrin of the French, who would later take over Morocco as part of their colonial Empire, and the British, who viewed the act as a challenge to their own power and a threat to peace in Europe. The end result of the whole event was a strengthened Entente cordiale that would eventually become the Allied Powers in the First World War.

Spengler was keenly aware of the situation at the time, and took on the task of writing a book on the subject that would contrast German and British world-aims and national spirits. The general thrust of this work would become his later work Prussianism and Socialism of 1919, but as he worked on Liberal and Conservative, he found his topic broadening more and more, to the point where he was taking into account not the national rivalries of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but the great trials and tribulations of entire civilisations over the course of millennia. Thus the work transformed into the first volume of his Decline of the West, the title of which he probably derived from discovering Otto Seeck’s Geschichte des Untergangs der antiken Welt (“History of the Downfall of the Ancient World” or The History of the Decline of Antiquity) in a store-front window.[19] He would complete the work over the next few years, well into the World War, about which he maintained a positive outlook, to the extent that his introduction to the first volume of Decline, appearing in 1917, bore the hope of the author (omitted in Atkinson’s translation) that “this book might not stand entirely unworthy next to the military achievements of Germany.”[20]

The book that took shape was sweeping in scale, painting the picture of a broad history of mankind as the life cycle(s) of massive organisms to which Spengler gave two names: Kultur and Zivilisation, each representing the youth and the adulthood of the organism. These organisms passed through four seasons of life—(as Kultur) Spring, Summer, (as Zivilisation) Autumn, and Winter—before passing from existence and leaving the soil to which it is tied to give rise to a new organism. A more detailed discussion of the theory may be required before departing into Spengler’s life after the War and the publication of Decline.

Decline of the West and its Influences

Der Untergang des Abendlandes occurs as a part of a long tradition of German historical writing, dating from the early nineteenth century and in which the giants of the field, both famous and infamous, stand: G.W.F. Hegel, Karl Marx, Heinrich von Treitschke, Leopold von Ranke, Heinrich Friedjung, among others. It also occurs as a part of a long tradition of German philosophy and social thought, dating even further into history and starting, not with the rational Kant, but with the intuitive and romantic, sometimes quasi-mystical writings of Goethe, following to Nietzsche, Ferdinand Tönnies, Max Weber, and still more. More can be said of Spengler’s influences, and has been said in the works of Farrenkopf and Fischer on the subject, but a brief discussion of chief influences will be sufficient for our purposes.

If Spengler was the first to propose a World-Historical view, as he claims in the early pages of Decline, Leopold von Ranke preceded him by for the first time proposing a European-Historical view in his two-volume Deutsche Geschichte im Zeitalter der Reformation (“German History in the Age of Reformation”) of 1845/47.[21] Ranke wrote a history which belongs to a very specific school of historical inquiry, dependent on objectivity and a slice of historical fact drawn from primary source work with bearing only on that exact moment in history, showing things wie es eigentlich gewesen, as he proclaims in his 1824 work Geschichte der romanischen und germanischen Völker von 1494 bis 1514 (“History of the Latin and Teutonic Peoples, 1494-1514”). For all his efforts at objectivity in history, he was a firm believer in the balance of power of nation-states, and his loyalty to this state philosophy bleeds through in his writing. He is significant to Spengler in that both men sought to broaden historical inquiry into an objective rather than national project, and that Spengler was certainly beholden to the school of narrative historicism that Ranke would found, inasmuch as his project was heavily criticised by more loyal Rankeans than himself.

If Spengler was the first to propose a World-Historical view, as he claims in the early pages of Decline, Leopold von Ranke preceded him by for the first time proposing a European-Historical view in his two-volume Deutsche Geschichte im Zeitalter der Reformation (“German History in the Age of Reformation”) of 1845/47.[21] Ranke wrote a history which belongs to a very specific school of historical inquiry, dependent on objectivity and a slice of historical fact drawn from primary source work with bearing only on that exact moment in history, showing things wie es eigentlich gewesen, as he proclaims in his 1824 work Geschichte der romanischen und germanischen Völker von 1494 bis 1514 (“History of the Latin and Teutonic Peoples, 1494-1514”). For all his efforts at objectivity in history, he was a firm believer in the balance of power of nation-states, and his loyalty to this state philosophy bleeds through in his writing. He is significant to Spengler in that both men sought to broaden historical inquiry into an objective rather than national project, and that Spengler was certainly beholden to the school of narrative historicism that Ranke would found, inasmuch as his project was heavily criticised by more loyal Rankeans than himself.

Spengler’s other major historical inheritance was G.W.F. Hegel, who stood with Ranke in his typical nineteenth century fascination with the nation-state but was completely opposed to Ranke’s objective, slice-of-history approach, demanding a broader view, and the ability to see the future in the past. Hegel was also a dedicated Prussian, much like Spengler’s father and Spengler himself—so much so, in fact, that he is among several German historians of preceding centuries who are mentioned by Shirer in his fumbling, attempt to link National Socialism and the Prussian state in Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. His declaration in Grundlinien der Philosophie des Rechts (“Elements of the Philosophy of Right”) that “the course of God in the world—that is the State—and its foundation is the mighty force of Reason actualising itself as Will” is reflected in Spengler’s own firm belief in the role of fate in the lifespan of Kultur-Zivilisation organisms.[22] Furthermore, like Hegel, Spengler’s history is a designated march to a designated end: for Hegel, the “end of history” is a progressive, linear movement from antiquity to modernity and the pinnacle of mankind’s development—a belief that has earned Hegel accusations of arrogance and stubbornness, among other things, from detractors. He would pass this view onto his student Karl Marx, who proclaimed the same progression, but from a strictly economic view, of modes of production through history, culminating in the elimination of alienation and the realisation of Species-being in Communism. The difference between the Hegelian and Marxian view of history and Spengler, however, is two-fold: while the given lifespan of a Kultur-Zivilisation organism can be viewed as linear, it is a downward motion rather than the upward motion Hegel and Marx see; further, there is no single linear history of all mankind, the way Hegel and Marx see it. Quite the contrary, Spengler echoes Goethe, declaring that “‘Mankind’ is a zoological concept or merely an empty word.”[23]

It seems contradictory, of course, that Spengler would reject that “mankind” exists while attempting very earnestly to write a “world-history.” As much as Spengler reflects Hegel and Ranke as historical predecessors, his views of the organism of society bear the marks of Ferdinand Tönnies, whose famous work Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft would practically found the discipline of sociology, influencing both Max Weber’s seminal The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism as well as Emile Durkheim’s functional theories of society.[24] Tönnies summarises his project in Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft in the very first page, saying “The connexion will be understood either as real and organic – this being the nature of the Gemeinschaft – or in an ideological and mechanistic form – this being the notion of Gesellschaft” and further summarising the difference between the two by saying that, “all that is familiar, private, living together exclusively (we find) is understood as life in a Gemeinschaft. Gesellschaft is the public sphere, it is the World”.[25]

Spengler’s structure of the communal, agrarian Kultur passing into individualised, urban Zivilisation has much in common with Tönnies’ conception of the organic Gemeinschaft and its artificial counterpart Gesellschaft. It is also important to bear in mind that the key to the Gemeinschaft/Gesellschaft schema is two-fold—both the contrast of the private with the public spheres as well as the organic with the artificial—when considering Spengler’s own contrast of the representative of Kultur, which is the “country-town” with the representative of Zivilisation, which is the megalopolis. As Spengler says himself, “long ago the country bore the country-town and nourished it with her best blood. Now the giant city sucks the country dry, insatiably and incessantly demanding and devouring fresh streams of men, till it wearies and dies in the midst of an almost uninhabited waste of country.”[26]

The contrast of the organic with the artificial, the personal with the impersonal, and the village with the city runs throughout Spengler’s whole structure. Spengler’s vision is two-fold: both the binary progression of Kultur crystallising and stagnating into Zivilisation as well the four-phase life cycle that all Kultur-Zivilisation structures (or, more properly, organisms) follow. Describing this, Spengler uses two sets of terms: organic terms, describing the actual birth, growth, decline, and death of the Kulture-Zivilization organism as a life form, and the fatalistic language for which he has been so criticised: he declares “the Civilisation is the inevitable destiny of a Culture… Civilisations are… a conclusion, the thing-become succeeding the thing-becoming, death following life”.[27] The central concept there—Werden and Gewordene, “becoming” and “become”—are ideas for which Spengler is deeply indebted (as he admits) to Goethe, and play strong role in the contrast he makes between the vivacious, developing Kultur and the stagnant, crystallised Zivilisation.[28]

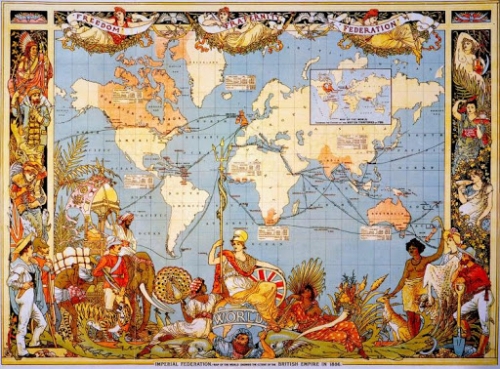

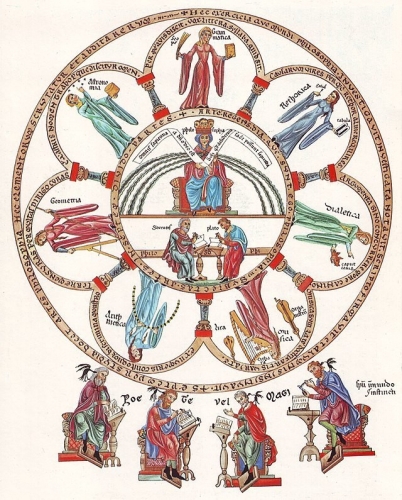

These Kultur-Zivilisation organisms are detailed in three tables he includes in his work: the first details the passage of Spring-Summer-Autumn-Winter, which for the Occident begins in 900, after the Carolingian period and the final death of Antiquity, and ends (or begins to end) with modernity, completely the roughly thousand-year lifespan which Spengler assigns to his Kultur-Zivilisation organisms (except those of the far east). Each Kultur-Zivilisation organism has a symbol which accompanies it in the Kultur phase; for the West it is infinite space; for the Egyptian, the long corridor; the Semitic, the cavern; the Greeks, the idealised statue, etc. Spengler also specifically names three of the “souls” of these organisms with especial bearing on the Occident. The West itself is “Faustian” defined by Goethe’s own character and his constant outward-reaching for knowledge and more; Antiquity, which the West has replaced, is “Apollonian”, a term readily borrowed from Nietzsche, defined by the Nietzschean Apollonian rationality and thirst for worldly perfection; finally, the Semitic, being Jewish, Arabic, etc. is a sort of mixed Kultur-Zivilisation organism called “Magian”, after the mystics who visited the birth of the Christ-child, and is defined by the preoccupation with essence rather than space.

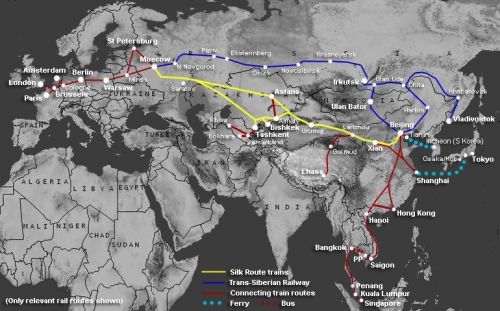

The Magian requires some further discussion, since it represents for Spengler a different “mutation” (to keep with the biological sense of an organism) of the main species of Kultur-Zivilizationen. This is because of a process Spengler describes in the second volume of Decline called “pseudomorphosis”. He asserts in the first volume that the “Arabian soul was cheated of its maturity—like a young tree that is hindered and stunted in its growth by a fallen old giant of the forest,” but after critiques of the work began to circulate back to him, realised that this was inadequate to explain the unique situation that the Magian Kultur-Zivilisation finds itself.[29] He therefore suggests a parallel with mineralogy, pointing the phenomenon of “pseudomorphosis”, by which volcanic molten rock flows into spaces left by washed away minerals in the hollows of rocks; likewise, since the Arabian culture’s pre-historical period is encompassed by Babylonian Civilization, and later as it develops it is stunted by Antiquity with the Roman conquest of Egypt.[30] Spengler sees a similar occurrence with the Russian Kultur-Zivilisation, which is pressed between the Faustian Kultur-Zivilisation and the Asiatic hordes which repeatedly conquer it. He maintains even in his last work, Jahre der Entscheidung, that the Bolshevist revolution represented a part of this pseudomorphosis that Russia is experiencing: “Asia has conquered Russia back from “Europe” to which it had been annexed by Peter the Great”.[31]

The Magian requires some further discussion, since it represents for Spengler a different “mutation” (to keep with the biological sense of an organism) of the main species of Kultur-Zivilizationen. This is because of a process Spengler describes in the second volume of Decline called “pseudomorphosis”. He asserts in the first volume that the “Arabian soul was cheated of its maturity—like a young tree that is hindered and stunted in its growth by a fallen old giant of the forest,” but after critiques of the work began to circulate back to him, realised that this was inadequate to explain the unique situation that the Magian Kultur-Zivilisation finds itself.[29] He therefore suggests a parallel with mineralogy, pointing the phenomenon of “pseudomorphosis”, by which volcanic molten rock flows into spaces left by washed away minerals in the hollows of rocks; likewise, since the Arabian culture’s pre-historical period is encompassed by Babylonian Civilization, and later as it develops it is stunted by Antiquity with the Roman conquest of Egypt.[30] Spengler sees a similar occurrence with the Russian Kultur-Zivilisation, which is pressed between the Faustian Kultur-Zivilisation and the Asiatic hordes which repeatedly conquer it. He maintains even in his last work, Jahre der Entscheidung, that the Bolshevist revolution represented a part of this pseudomorphosis that Russia is experiencing: “Asia has conquered Russia back from “Europe” to which it had been annexed by Peter the Great”.[31]

This is the structure within which the subject of Spengler’s title exists. Spengler remarked on his title at length in an essay titled “Pessimismus?” (“Pessimism?”) appearing in the Preußischer Jahrbücher in 1921:

But there are men who confuse the downfall [literally “going under”] of Antiquity with the sinking of an ocean liner. The notion of a catastrophe is not contained in the word. If one said—instead of downfall—completion, an expression that is linked in a special way with Goethe’s thought, the “pessimistic” side is removed without the real sense of the term having been altered.[32]

He is not, therefore, discussing a cataclysmic event that would bring about the end of Western civilisation, though no doubt much of the appeal of his work was the recent catastrophe of the Great War. What he sees instead is a general inadequacy in the trends coming out of his contemporary West, which the Great War only compounded. Faustian civilisation had come to stagnate with the rise of bourgeois economists; as he says, “through the economic history of every Culture there runs a desperate conflict waged by the soil-rooted tradition of a race, by its soul, against the spirit of money”.[33] The capitalism and industrialisation of liberal Europe represents the bleeding dry of the soul of Faustian Kultur; it, too, however, shall pass in the coming Ceasarism of the Faustian Winter that Spengler predicts. He speaks of “the sword” being triumphant over money-power and finance capital, bringing about the final period of where violence of spirit triumphs and is marked by the rise of the “Caesars”, demagogues who will bring about a Western World Imperium that Spengler envisioned being headed by Germany. It is worth noting that John Farrenkopf believes this to remain an accurate prediction for America, which Spengler himself discounted, as most Europeans at the time, as an adolescent child of Europe, hardly capable of contributing to Faustian Zivilisation in any great way.

It is, at last, important to note that while Spengler offers this structure that explains history, it is not his intent to “save” the Occident. He participated in politics that would, in his view, further the progression of Faustian Zivilization out of its Autumn and into Winter, but, in true Nietzschean fashion, he encourages his readers to adopt an amor fati toward the decline of their Kultur-Zivilisation. Indeed, the hope one retains after reading Spengler is of a peculiar kind—since all Kultur-Zivilisationen are destined to wither and die, the Faustian man should embrace the destruction of the Occident with an eye to the subsequent Kultur-Zivilisation organism that will take its place, which Spengler predicts will be Russian, a society which due to close contact to both the Occidental and Asian Kultur-Zivilisation organisms has not been able to come into itself—in short, it is not yet Werden, existing in the historyless period that marks the beginning and end of every Kultur-Zivilisation organism.

The Conservative Revolutionary (Political Writings and Speeches, 1919-1924)

The Decline of the West marks a high-point in Spengler’s life, and also a turning point for both his own life and the life of Germany as a whole. Decline appeared complete in two volumes in 1922, four years after Germany’s defeat in the First World War and in the midst of the Weimar Republic struggling to get on its feet. As mentioned above, this contributed greatly to the book’s circulation, though it is unclear how many enthusiasts made an effort to read the entire text. Spengler found himself now ushered into higher intellectual circles, battling with intellectual greats over the value of his work, and once again able to enjoy the delicacies he had to go without for the duration of the War (he wrote that much of the work he did on Decline was done by candlelight). In 1919 he joined such famous names as Hermann Alexander Graf Keyserling (for his seminal work Reisetagebuch eines Philosophen, “Travel-Diary of a Philosopher”) and distinguished Kant scholar Dr. Hans Vaihinger (for his work Philosophie des Als Ob, “The Philosophy of As-If”) in being awarded the Nietzsche Archives’ “Distinguished Scholar Award” with an academic diploma and the sum of 1,500.00DM (roughly $45.00 in 1919).[34]

Despite his acute sense of the depressing reality of his work, Spengler was materially well-off and led a generally comfortable life because of its popularity. He moved from the small flat where he had written Decline during the war to a spacious apartment that overlooked the Isar River. He decorated it with a variety of fine paintings, Chinese and Greek-styled vases, and other pieces obtained at auctions or gifted to him by admirers, and shocked visitors with his vast library, which literally lined the walls of his new home. He covered the fine hard-wood floors with even finer rugs, most markedly a strikingly red carpet in his office upon which he was known to pace endlessly in the night while he worked.[35] He was, though, of relatively modest tastes, and was frugal with his money. He took holidays to Italy frequently, but otherwise only left Germany when another party could pay for his travel; his tastes at home included trips to the theatre, fine wines, and a regular supply of dark cigars. He never hired a housekeeper or married, and his sister Hildegard, widowed by the World War, would keep house for him. He rarely entertained and continued to devote himself to work. His work now, though, was not strictly scholarly.

A well-known name now, Spengler began to take a greater interest in politics than he had hitherto. He wrote to Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz in 1920 regarding the recovery of the flag from the SMS Scharnhorst, which was sunk in the Battle of the Falkland Islands in 1914, taking Admiral Maximillian Graf von Spee to the bottom with it; the flag, Spengler wrote, had fallen into the hands of an anti-German party who wished to send it to Britain to be a trophy of war, something offensive to Spengler as a German nationalist.[36] Admiral von Tirpitz replied that he would refer the matter to the admiralty, but the flag was undoubtedly not that from the Scharnhorst’s main post, which went down flying, and therefore the value of the demands of the original owners for the flag (50,000-60,000DM) was probably not equal even to its sentimental value. The admiral added, probably much to Spengler’s satisfaction, that he had thoroughly enjoyed reading Prussianism and Socialism, and wrote “I only wish that your ideas could find response in the Marxist-infected working classes.”[37]

A well-known name now, Spengler began to take a greater interest in politics than he had hitherto. He wrote to Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz in 1920 regarding the recovery of the flag from the SMS Scharnhorst, which was sunk in the Battle of the Falkland Islands in 1914, taking Admiral Maximillian Graf von Spee to the bottom with it; the flag, Spengler wrote, had fallen into the hands of an anti-German party who wished to send it to Britain to be a trophy of war, something offensive to Spengler as a German nationalist.[36] Admiral von Tirpitz replied that he would refer the matter to the admiralty, but the flag was undoubtedly not that from the Scharnhorst’s main post, which went down flying, and therefore the value of the demands of the original owners for the flag (50,000-60,000DM) was probably not equal even to its sentimental value. The admiral added, probably much to Spengler’s satisfaction, that he had thoroughly enjoyed reading Prussianism and Socialism, and wrote “I only wish that your ideas could find response in the Marxist-infected working classes.”[37]

The work Admiral Tirpitz praised so highly was Spengler’s second attempt to reflect on the Agadir crisis and the significance of German and British relations. Prussianism and Socialism appears in English translation by Donald O. White with a number of other shorter articles that Spengler penned in the early 1920s. The work appears in White’s 1967 collection Selected Essays, which is roughly a translation of Politischen Schriften, but making some omissions and drawing also from Rede und Aufsätze. The overall collection gives a decent introductory glance at Spengler’s social and political thought, which merits it some exposition here. Other works included in it are “Pessimism?”, which was written as a response to the charge levelled against Decline, his two speeches “The Two Faces of Russia and Germany’s Eastern Problems” (delivered to a conference of influential Ruhr industrialists in 1922) and “Nietzsche and his Century” (delivered at a conference hosted by the Nietzsche Archive in 1924 before Spengler severed ties with Elizabeth Förster-Nietzsche because of her alignment with Hitler ten years later), another short essay titled “On the German National Character”, published in 1927, and finally a brief response given by Spengler to a query posited internationally by Hearst International’s The Cosmopolitan, titled “Is World Peace Possible?”, which was published in what White calls “barely adequate translation” in 1936 alongside answers from Mohandas K. Gandhi, Eleanor Roosevelt, General Billy Mitchell, and Lin Yu-tang.[38]

Prussianism and Socialism abandons Spengler’s earlier, less informed political alignment with the Kaiser, but beyond this minor change it expresses and sets the tone for almost all of Spengler’s other political writings before and after, including his final major work, Hour of Decision. It is also the work that initiated Spengler’s name into the collection of intellectuals and aristocrats that formed the “Conservative Revolution” movement in Weimar Germany. The names he is included with range from the completely obscure to the internationally famous. Among them are obscure authors like Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, for his work, later appropriated by the Nazis, Das Dritte Reich (1923—available in English as Germany’s Third Empire) and Edgar Julius Jung, who is seen as the leader of the movement, for his work Die Herrschaft der Minderwertigen (“The Reign of the Mediocre”, 1927), and more famously for Franz von Papen’s “Marburg Speech”, the last open condemnation of Nazism made in Weimar Germany. However, members of the movement also included men like the internationally acclaimed Ernst Jünger, for his famous memoir of the World War, In Stahlgewittern (first published in 1920 and having been revised by the author 7 times, it is now available in very good translation by Michael Hoffmann as Storm of Steel), Der Kampf als inneres Erlebnis (“Battle as Inner Experience”, 1922), Das Wäldchen 125 (“Copse 125”, 1925) and Feuer und Blut (“Fire and Blood”, 1925) as well as the famous and widely translated Carl Schmitt, now well known for his works Die Diktatur (1921—now available in translation as On Dictatorship), Politische Theologie (1922—available as Political Theology), Die geistesgeschichtliche Lage des heutigen Parlamentarismus (1923—now available in a good translation by Ellen Kennedy titled The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy), and his extremely significant Der Begriff des Politischen (1926—now available as The Concept of the Political). The unifying feature of the movement was a desire to bridge the gap between nationalist conservatism and socialism, though another major factor was the distaste that all the men had for Adolf Hitler and his, in the words of Moeller van den Bruck, “proletarian primitiveness”.[39]

Spengler’s interactions with other conservatives were largely done through his involvement in the Juniclub (“June Club”) a gathering of Conservatives and Monarchists who shared Spengler’s hatred of the Versailles Treaty (commonly known in Germany as the Versailles Diktat because of the lack of input allowed from the German delegation). Among the group’s founding members was Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, with whom Spengler had many encounters from 1919 until Moeller’s suicide in 1925 through lectures that both gave to the Juniclub. At the Juniclub he also had the opportunity to meet and begin correspondence with Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria, Walther Rathenau, Erich Ludendorff, Hans von Seeckt, and create friendships and lasting ties to major industrialists like Paul Reusch, Roderich Schlubach, Alfred Hugenberg, Karl Helfferich, and Hugo Stinnes.[40] Aside from Moeller, however, his encounters with the other major thinkers of the Conservative Revolutionary movement seemed few; he had some contact later with Jung, who wrote him on several occasions. However, his major inclination during his years of involvement with the Juniclub was toward becoming actively involved in conservative politics, not merely being a theoretician. His ambitions during this time were as disparate and far-flung as leading German intellectuals into politics and founding a newspaper cartel in imitation of William Randolph Hearst.[41]

Spengler’s letters during this time are often brief (owing to his preference for meeting people rather than writing them) and to a wide variety of people, including invitations to tea with Erich Ludendorff and his wife, which he maintained as a regular affair until Ludendorff’s involvement in the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923. There was also an extended correspondence with the German government regarding interaction with General Jan C. Smuts, who had invited General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck (with whom Spengler also corresponded) to a dinner for African commanders of the war.[42] He also met semi-regularly, it would seem, with the Prussian royal family; Crown Prince Wilhelm wrote him a number of times, and Spengler sent copies of his magnum opus to Huis Doorn. He also managed to elicit a positive response from Gregor Strasser, a prominent rival of Hitler’s in the National Socialist party who was murdered in the Night of the Long Knives.[43]

Spengler’s letters during this time are often brief (owing to his preference for meeting people rather than writing them) and to a wide variety of people, including invitations to tea with Erich Ludendorff and his wife, which he maintained as a regular affair until Ludendorff’s involvement in the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923. There was also an extended correspondence with the German government regarding interaction with General Jan C. Smuts, who had invited General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck (with whom Spengler also corresponded) to a dinner for African commanders of the war.[42] He also met semi-regularly, it would seem, with the Prussian royal family; Crown Prince Wilhelm wrote him a number of times, and Spengler sent copies of his magnum opus to Huis Doorn. He also managed to elicit a positive response from Gregor Strasser, a prominent rival of Hitler’s in the National Socialist party who was murdered in the Night of the Long Knives.[43]

Spengler, however, remained primarily a theoretician; he met many men with whom he had lasting friendships, but he was not a man of political action and he was acutely aware of that. Throughout his brief political career, he was advised by friends not to waste his genius on petty affairs of state, and he eventually gave in and retreated from public life in 1924 after five years of immense popularity and prolific writing. In addition to the one or two speeches and articles in the White collection, in 1924 alone Spengler published Frankreich und Europa (“France and Europe”), Aufgaben des Adels (“Tasks of the Nobility”), Politische Pflichten der deutschen Jugend (“Political Duties of the German Youth”), Neubau des deutschen Reiches (“Reconstruction of the German Reich”), Neue Formen der Weltpolitik (“New Forms of Global Politics”) all of which were derived from speeches and lectures he had given at the Juniclub or at various Industrial clubs and conferences during his involvement there. Some of them, including Politische Pflichten and Neubau would appear in Spengler’s Politischen Schriften of 1932, the others would only be published together in 1937 in the posthumous Reden und Aufsätze collection. The works, all expressing a common theme of the necessity to “reclaim socialism” from Marx and bring about a new birth of “Prussianism” in the German population, brought Spengler immense notoriety in Germany while Decline was making its way through foreign circles. Other presentations included his Das Verhältnis von Wirtschaft und Steuerpolitik seit 1750 (“The Relationship of Economy and Tax Policy since 1750”, 1924). His lectures drew tremendous crowds and he participated in a number of public debates between 1919 and 1924.

Prussianism and Socialism: A Brief Glance

Of all Spengler’s political writings and speeches, both from his public career and after, the most detailed and the most significant remains Prussianism and Socialism. In the work, Spengler makes two arguments, one unique to his own time and one with far-reaching relevance. The work’s principal argument surrounds the “true German spirit” with “the German Michel”, which Spengler declares “the sum of all our weaknesses: our fundamental displeasure at turns of events that demand attention and response; our urge to criticise at the wrong time; our pursuit of ideals instead of immediate action; our precipitate action at times when careful reflection is called for; our Volk as a collection of malcontents; our representative assemblies as glorified beer gardens.”[44] The thrust of the work is a contrast between “English” parliamentarianism and liberalism, which the “German Michel” typifies, the Marxist socialist movement of the Sparticists, which at least has the integrity that the “German Michel” lacked, and real “German” socialism, which Spengler ties to Prussian military spirit and civic duty to create the “Prussian socialism” that he insists is the only way to bring about a rebirth of the German Reich.

The opening of Prussianism and Socialism declares the same sense of destiny found in Decline, quoting Seneca's aphorism ducunt volentem fata, nolentem trahunt (“Fate leads along the willing soul and drags the unwilling”).[45] He declares that “the spirit of Old Prussia and the socialistic attitude, at present driven by brotherly hatred to combat each other, are in fact one in the same”, defining “socialism” itself, which he claims “everyone thinks… means something different”.[46] Spengler’s hero of socialism is August Bebel, the Marxist founder of the SPD who was famously born in a Prussian army barracks. He praises Bebels’ party for its “militant qualities…the clattering footsteps of workers’ battalions, a calm sense of determination, good discipline, and the courage to die for a transcendent principle” and damns the SPD in power in the Weimar Republic for abandoning the revolution and throwing in its lot with the “foe of yesteryear” and encouraging the Freikorps to crush the Spartacists, who Spengler felt “retained a modicum of integrity”.[47] It is not the Marxism of the Social Democrats Spengler admires, however; rather, it is their integrity and their dedication to their beliefs—something that simply does not exist for the “German Michel”, the contemporary parliamentarian.

He goes on to condemn the “so-called German Revolution” that took place in November, saying that the Germans “produced pedants, schoolboys, and gossips in the Paulskirche and in Weimar, petty demonstrations in the streets, and in the background a nation looking on with faint interest”—not at all what a real revolution entails, but something feeble, something belonging to the parliamentarian and the “German Michel”.[48] Spengler establishes the foundation of Prussian Socialism with “the real German Socialist Revolution” which he says happened in 1914—a real revolution because it involved “the whole people: one outcry, one brazen act, one rage, one goal”.[49] He further asserts that the revolution is not over—a notion he expands on in later speeches and essays. The Revolution of the German people cannot come to full fruition for Spengler and his fellow conservatives, until the German nation is truly born—for 1918 in Germany was not 1789 in France; the nation and the revolution were not the same.

He concludes that “Socialism is not an instinct of dark primeval origin… it is, rather, a political, social, and economic instinct of realistically-minded peoples, as such it is a product of one stage of our civilisation—not of our culture.”[50] He asserts a thoroughly modern origin and a thoroughly modern role for socialism: the realistic, the enemy of the dictatorship of money and capitalism, defined in socialistic form by a sense of duty to the whole, that whole being the German nation. It is in this way that “all Germans are workers”, so that the failing of Marx, he asserts, is his inability to grasp anything more in Hegel, “who by and far represented Prussianism at its best” than mere method.[51] Marx misleads socialism by creating class antagonism when in reality the bourgeois is a meaningless term, Spengler asserts—and the real enemy is the English spirit of mercantilism and parliamentarianism of the feeble “German Michel”; it is not worker against burgher, nor burgher against elite, but German against the Englishman in himself. This is why the German Revolution is incomplete: because the national revolution that unites and brings about the birth of the German nation has not been achieved.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of this and subsequent political texts is the complete absence of any mention of Germany’s Jews. Spengler did not believe, as many of his day did, that the Jewish people had any connexion to parliamentarianism or Marxism or Capitalism or any other distinctly Western phenomenon; rather Western man was at war with himself and himself alone in the conflict between Prussian Socialism and English Mercantilism, between Revolution and Cowardice. He calls Marx “an exclusively English thinker”, unable to see beyond mere economics and ignoring the notion of everyone working for the whole, but each in his own destined place—the King for Spengler’s socialist is “the first servant of the state”, in the highest place among the rest of the nation serving a single, national goal. It is such a different picture than the typical anti-Bolshevik stance in Germany that never tired of reminding the world of Marx’s Jewish origins (his grandfather was a rabbi). This, for Spengler, was as much a simplification as Marx’s class antagonism, because it directed anger and action toward an invented foe instead of directing it toward corrective measures in the West itself.

The Hermit-Scholar (Return to Private Life 1924-1930)

After he retreated from public life, Spengler returned to the lonely life of the hermit scholar, and rededicated himself to work on the theories put forth in Decline. His re-entry into politics was prevented both my deteriorating health as well as a decrease in opportunity with the rising tide of National Socialism. Of all the Conservative Revolutionary thinkers, only Jünger and Schmitt would live to see the Second World War, and their literary lives were even shorter; Spengler was silenced by the Nazi state as early 1933, Jung was murdered, along with several of Spengler’s friends, in the Night of the Long Knives in 1934, and Moeller van den Bruck had a nervous breakdown and committed suicide as early as 1925. Others, like Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Stefan George (especially famous for his Das Neue Reich of 1928), died of natural causes, Hofmannsthal of a stroke in 1929, George four years later of old age. It is indubitable with his voracious appetite for the latest works that Spengler encountered these men through their writing, but no correspondence between them exists. This is not terribly surprising—Spengler wrote letters when he felt the passion to do so (such as to Admiral Tirpitz), or when it furthered his studies (such as the many letters to academics and professors). This was not out of a dislike of people; rather, it was because he detested the task of writing letters and preferred to grant an interview or meet with friends in person, something he did frequently—his sister, Hilde, who became primary caretaker of his estate after his death, remarked that “he always disliked writing letters, even when he was a child.”[52] Those political letters he did write he wisely burned in 1933 to protect himself and others from the National Socialist state.

The return to private living gave Spengler a tremendous opportunity to begin scholarly work again after some years of pamphleteering (something he himself hated, remarking to a friend in 1919, referring to Prussianism and Socialism that “I am not a born journalist and consequently I wrote out 500 pages of rough draft in four weeks and then started paring to get 100 pages of readable German. I realise now how I ought to work and shall never again accept any assignment that carries a deadline with it”).[53] He never ceased his correspondences with high-level academics and contributors in almost every field of study, but after 1924 he was able to begin to write more widely. He wrote frequently to Elizabeth Förster-Nietzsche and it was in 1924 after his departure from public life that he presented his paper “Nietzche and His Century”.

From 1925 onward his time was dominated by lectures, correspondences, and his old reading habits. He took several holidays in Italy and elsewhere, and as early as 1925 was in correspondence with Benito Mussolini, who would write a review of Hour of Decision in 1933 for Il Popolo d’Italia in December of that year. The Italian dictator, it would seem, was somewhat reserved about Spengler, who he felt tread close to Fascism but was not close enough.[54] He was not alone; after Spengler’s retreat from politics, was when his works came under heaviest fire from popular political personalities. His correspondence with Gregor Strasser in 1925 displays the chief dispute with Spengler, which seems to be his dislike of “popular movements”, like National Socialism, which he regarded as vulgar and mob-driven.[55] Aside from these, however, the bulk of his letters are not with political men but with academics.

The reason for this likely had much to do with Germany’s growing stability after 1925. Arthur Helps, who translated Spengler’s letters, suggests that Spengler left the public sphere precisely because of this; however, it is more likely that Spengler simply tired of the time he spent in the public eye—the constant assault of attention from both enthusiastic supporters and detractors of all stripes wore on the man whose sensitivity was well-known only to his sister and perhaps very close friends. He was a man who throughout his life was soft-hearted and sympathetic, ever striving to overcome the little boy whose nightmares in his bedroom in Halle haunted him vividly until he was well into his forties; the image he had inadvertently created of the hard-hearted, iron-willed prophet of doom was not an easy persona for him to fulfil on a constant basis, and put tremendous stress on his body. Fischer observes in his biographical sketch that “he agonised about his weaknesses with the same honesty as Rousseau did in the Confessions, with the difference that Spengler rarely tried to project his shortcomings on society… [he] believed that, in the final analysis, the individual has to assume responsibility for his own weaknesses”.[56]

The reason for this likely had much to do with Germany’s growing stability after 1925. Arthur Helps, who translated Spengler’s letters, suggests that Spengler left the public sphere precisely because of this; however, it is more likely that Spengler simply tired of the time he spent in the public eye—the constant assault of attention from both enthusiastic supporters and detractors of all stripes wore on the man whose sensitivity was well-known only to his sister and perhaps very close friends. He was a man who throughout his life was soft-hearted and sympathetic, ever striving to overcome the little boy whose nightmares in his bedroom in Halle haunted him vividly until he was well into his forties; the image he had inadvertently created of the hard-hearted, iron-willed prophet of doom was not an easy persona for him to fulfil on a constant basis, and put tremendous stress on his body. Fischer observes in his biographical sketch that “he agonised about his weaknesses with the same honesty as Rousseau did in the Confessions, with the difference that Spengler rarely tried to project his shortcomings on society… [he] believed that, in the final analysis, the individual has to assume responsibility for his own weaknesses”.[56]

Spengler’s physical weaknesses became acute during his time in politics, as the stress increased his headaches and other ailments. In 1925, rarely does a letter mention an illness or time of sickness—he seemed to recover from his ailments from getting away from stress of politics and the dismal state in which he perceived his beloved German Reich to be. He took cures in the sun of Italy, writing in February of 1925 from Palermo, after which he travelled to Rome and elsewhere.[57] In 1926, deep in the scholarly world once again, Spengler was invited by the Philosophical Congress in the United States to travel to America and conduct a lecture tour (C.F. Atkinson’s translation of the first volume of Decline appeared that very year). His excuse for declining the offer was that he felt America would leave too deep an impression on him that would disrupt the work he was conducting on his latest book (still unfinished at his death), Urfragen (“Primordial Questions”). His letters are strewn with questions to experts and professors of ancient history after information about Babylonian tablets and other Middle Eastern interests.

These interests, as a preparation for Urfragen, had begun as early as 1924, when Spengler appeared before the Oriental Institute in Munich with a lecture titled “Plan eines neuen Atlas Antiquus” (“Plan for a new Atlas Antiquus”), which detailed the need of a new cartographic project to map the ancient world within the scope of the Apollonian Kultur-Zivilisation organism.[58] The general thrust of his work, whether this lecture or the later letters to colleagues, is a collaborative effort that would overcome the increasing specialisation of history already in its adolescence in Spengler’s day and still increasing in contemporary academic history. During subsequent years he also became first enthralled and then embroiled with the famous archaeologist and ethnographer of Africa, Leo Frobenius, whose initial agreement with cyclical history caught Spengler’s attention, but his argued proofs for slow, gradual development of civilisations drew the censure of the author of Decline, who believed in epochal moments rather than gradual evolution (he detested all forms of Darwinism). His correspondence took him in more positive directions with the famous Assyriologist Alfred Jeremias, who took an immense interest in Spengler’s work.

Most striking about Spengler’s time as a private scholar in the late 1920s was the vast amount of interest being generated in his works abroad. 1927 saw contacts coming from The New York Times attempting to solicit an article from him; the paper had featured him in full-page articles twice before, and after including him in an article “Will our Civilization Survive?” of 1925, hoped he might appear in print with them—they even offered a sum of $100, which was no small sum of money in Germany at the time.[59] No response to their inquest ever came, however, and it does not appear Spengler showed any interest in taking up any journalistic venture. A query that Spengler felt did merit response came from André Fauconnet, a professor at Poitiers whose Un philosophe allemeand contemporain Oswald Spengler. Le prophète du déclin de l'Occident (“A Contemporary German Philosopher: Oswald Spengler, the Prophet of the Decline of the Occident”) appeared in 1925. He also received an invitation to speak at the University of Saragossa, which promised he could speak in German and translations of his speech would be distributed beforehand.[60] Spengler accepted the engagement, spending the entire month of April of 1928 on holiday in Spain; he loved the climate and found the place to have a profoundly positive affect on his demeanour—he even did some mountain climbing. He wrote his sister Hilde from Granada (where he stayed for about a week), “Grenada is beautiful beyond all description… I could live here”, and, later that week, that “here every day pleases me better”.[61]

During all of his touring and international correspondence, Spengler did manage to make one or two forays back into political life; the first occasion was a speech in Düsseldorf before the Industry-Club titled “Das heutige Verhältnis zwischen Weltwirtschaft und Weltpolitik” (“The Contemporary Relationship between World Economics and World Politics”) in 1926, and was solicited by Edgar Julius Jung a year later to make a speech before the German Student Union, historically a hotbed for right-wing politics. 1927 also saw him begin writing on the topic again, with “Zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der Deutschen Presse” (“Toward a Developmental History of the German Press”) appearing in the Der Zeitungsverlag and “Vom Deutscher Volkscharakter” (“On the German National Character”) appearing in Deutschland the same year. After some time of soliciting his attention, Richard Korherr also finally convinced Spengler to write a brief introduction to his thesis “Über den Geburtenrückgang” (“Regarding the Decline of Birthrates”) of two years previous, which the author had dedicated to Spengler. Korherr hounded Spengler with information of the thesis, especially when it was translated into Italian by deputies of Mussolini’s in 1928.[62] Spengler regarded the young student well, and congratulated him on his success; he would probably not have had so positive a view of the young Dr. Korherr twelve years later, when he became one of Heinrich Himmler’s most loyal lieutenants in executing the “Final Solution”.[63]

During all of his touring and international correspondence, Spengler did manage to make one or two forays back into political life; the first occasion was a speech in Düsseldorf before the Industry-Club titled “Das heutige Verhältnis zwischen Weltwirtschaft und Weltpolitik” (“The Contemporary Relationship between World Economics and World Politics”) in 1926, and was solicited by Edgar Julius Jung a year later to make a speech before the German Student Union, historically a hotbed for right-wing politics. 1927 also saw him begin writing on the topic again, with “Zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der Deutschen Presse” (“Toward a Developmental History of the German Press”) appearing in the Der Zeitungsverlag and “Vom Deutscher Volkscharakter” (“On the German National Character”) appearing in Deutschland the same year. After some time of soliciting his attention, Richard Korherr also finally convinced Spengler to write a brief introduction to his thesis “Über den Geburtenrückgang” (“Regarding the Decline of Birthrates”) of two years previous, which the author had dedicated to Spengler. Korherr hounded Spengler with information of the thesis, especially when it was translated into Italian by deputies of Mussolini’s in 1928.[62] Spengler regarded the young student well, and congratulated him on his success; he would probably not have had so positive a view of the young Dr. Korherr twelve years later, when he became one of Heinrich Himmler’s most loyal lieutenants in executing the “Final Solution”.[63]

Cassandra (Last Writings and Death, 1930-1936)

The years of 1929 and 1930 were eventful for Germany, but for Spengler much of the same that he had experienced in the second half of the 1920s. His pessimism was beginning to be proven true, with the stock market crash in 1929 and the swift rise of National Socialist and German Communist party power in the shattered Weimar Republic. In September 1930, the results gave the Nazis 107 seats in the Reichstag, and increased the Communist seats from 54 to 77. When the Reichstag took its seats, no business could be conducted, with the National Socialist “delegates” showing up in full uniform, sometimes with flags, interrupting the proceedings with chants, shouts, and songs; the Communists, not to be outdone, followed suit, and together they made a mockery of what was left of Weimar democracy.[64] Spengler was generally not disappointed with the turn of events, and, having put his Urfragen project on hold, wrote a prolegomena to his planned work titled Der Mensch und die Technik (“Man and Technics”) in 1931.

The work can hardly be said to be of the same calibre as Decline or even of Prussianism and Socialism—but then, it was never meant to be. The most important introductory note that can be given on Man and Technics is that it is fundamentally meant to be a primer for planned works. It is, by and large, a restatement of things said in Decline, and an expansion on the relationship between human beings and the tools they create. Fischer describes the book by saying “Spengler tried to show that primitive man was a magnificent predatory animal who possessed two major advantages over other beasts of prey: a superior brain and ambidextrous hands.”[65] The work is a true experiment in Nietzschean psychology by Fischer’s estimate: a tragic conflict between a naturally savage and predatory human being with the moral codes he makes to contain his savagery, but he cannot flee from it, for as he develops his technology, he also develops his means of savagery, and therefore his savagery itself.[66]

In greater detail, the book develops themes of conflict between man and external nature as well. Farrenkopf highlights that Spengler sees a religious grounding for this conflict—a suggestion not lost on several subsequent environmentalists—declaring that Spengler “claims to have uncovered the ‘religious origins’ of Western technical thought in the meditations of early Gothic monks, who in their prayers and fastings wrung God’s secrets from Him.”[67] Farrenkopf, working at the turn of the twenty-first century, attempts to make Spengler the prophet of “climate change” and “ecological disasters”, and points to a thesis in his own work—that Spengler’s thought changed from Decline to his later works—to say that Spengler was arguing for the inevitable failure of mankind’s struggle against nature. Whether his thesis has merit or not is not really a line of inquiry this introduction need undertake, but the conflict and eventual failure of humankind because of its own “progress” is certainly present in the work. A line from Decline of the West, quoted above, accurately encapsulates the entire purpose of Man and Technics: “the giant city sucks the country dry, insatiably and incessantly demanding and devouring fresh streams of men, till it wearies and dies in the midst of an almost uninhabited waste of country.”[68]

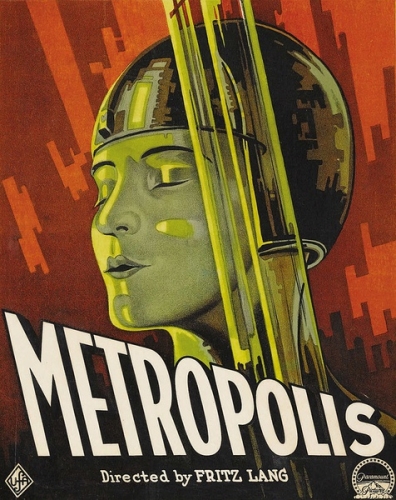

The urban sprawl and disappearance of the “green belt” that contemporary commentators, especially in America, where there is so much of the “green belt”, have witnessed is somewhat captured in this picture. The dangers of an industrial dystopia and plea for an agrarian Reich was one also being preached by the National Socialists at this time—Walther Darré’s 1928 pamphlet “Das Bauerntum als Lebensquell der nordischen Rasse” (“The Peasantry as the Life-source of the Nordic Race”) stands as a testament to that. The Nazis, though, were better at selling their message than Spengler was his own, primarily because of what each promised the German people. Spengler promised that the path of Western civilisation was destined and irreversible, and the coming destruction guaranteed by the very nature of Faustian man of his home-soil should be greeted with a Nietzschean amor fati. The Germans in 1931 were in no mood to hear that they were themselves to blame for their situation, and that it was an inescapable destiny.

The Nazis, on the other hand, gave the Germans an enemy—the Jews—that were causing this industrialisation and destruction of the nation, and if they could just get rid of them, there was a bright hope and future for Germans. The German people declared which message they preferred with dismal sales for Man and Technics, and subsequent tremendous victories at the ballot for the National Socialists. Hitler’s biographer, Lord Bullock gives a deep insight into the exact state of affairs; “taking 1928 as a measuring rod,” he declares, “the gains made by Hitler – close on thirteen million in four years – are still more striking,” adding that by early 1932, “with a voting strength of 13,700,000 electors, a party membership of over a million and a private army of 400,000 S.A. and S.S., Hitler was the most powerful political leader in Germany, knocking on the doors of the Chancellery at the head of the most powerful political party Germany had ever seen.”[69]

Spengler was shocked, if not a little appalled, by this turn of events. To Spengler, as he had been to Moeller, Adolf Hitler was an idiot in the scientific sense of the word: a vulgar proletarian clown shouting and flailing his arms and playing about in the muck, not a statesman who could lead Germany to her rebirth or a realistic forward-thinker. For the time being, though, there were few other options, and Spengler was willing to give the Führer the benefit of the doubt before meeting him—a meeting at which he hoped that his stature as one of Germany’s leading conservative intellectuals might moderate the Austrian firebrand somewhat.[70] He was dreadfully wrong.