vendredi, 11 octobre 2013

Too Much Putin?

Too Much Putin?

By Michael O'Meara

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

US hegemony may be approaching its end. Once the world refuses to acknowledge the imperial authority of its humanitarian missiles, and thus stops paying tribute to its predatory model of the universe (as momentarily occurred in Syria), then American power inevitably starts to decline – and not simply on the world stage, but also domestically, among the empire’s subjects, who in the course of the long descent will be forced to discover new ways to assert themselves.

***

Historically, America’s counter-civilizational system was an offshoot of the Second World War, specifically the US conquest of Europe — which made America, Inc. (Organized Jewry/Wall Street/the military-industrial complex) the key-holder not solely to the New Deal/War Deal’s Washingtonian Leviathan, but to its new world order: an updated successor to Disraeli’s money-making empire, upon which the sun never set.[1]

The prevailing race-mixing, nation-destroying globalization of the last two and a half decades, with its cosmopolitan fixation on money and commerce and its non-stop miscegenating brainwashing, is, as such, preeminently a product of this postwar system that emerged from the destruction of Central Europe and from America’s Jewish/capitalist-inspired extirpation of its European Christian roots.[2]

The fate of white America, it follows, is closely linked to the “order” the United States imposed on the “Free World” after 1945 and on the rest of the world after 1989. This was especially evident in the recent resistance of the American “people” to Obama’s flirtation with World War III – a resistance obviously emboldened by the mounting international resistance to Washington’s imperial arrogance, as it (this resistance) momentarily converged with the worldwide Aurora Movements resisting the scorch-earth campaigns associated with US power.[3]

***

Everyone on our side recognizes the ethnocidal implications of America’s world order, but few, I suspect, understand its civilizational implications as well as Russia’s Vladimir Putin.

On September 19, barely a week after our brush with the Apocalypse, the Russian president delivered an address to the Valdai International Discussion Club (an international forum on Russia’s role in the world), which highlighted the extreme degree to which Putin’s vision of world order differs from that of Obama and the American establishment.[4] Indeed, Putin’s entire line of thought, in its grasp of the fundamental challenges of our age, is unlike anything to be found in the discourse of the Western political classes (though from the misleading reports in the MSM on his Valdai address this would never be known).[5]

Putin, to be sure, is no White Nationalist and thus no proponent of a racially-homogenous ethnostate. This makes him like everyone else. Except Putin is not like everyone else, as we’ll see.

Certain East Europeans, instinctively anti-Russian, like our Cold War “conservatives,” refuse to appreciate Russia’s new international role because of historical grievances related to an earlier legacy of Tsarist or Soviet imperialism (though their grievances, they should know, bare little comparison to those “We Irish” hold against the English ruling class). In any case, such tribal grievances are not our concern, nor should they prevent the recognition that East Europeans and Russians, like Irish and English – and like all the national tribes belonging to that community of destiny distinct to the white man – share a common interest (a life-and-death interest) in being all prospective allies in the war against the globalist forces currently assaulting them in their native lands.

It’s not simply because Russia is anti-American that she is increasingly attractive to the conscious remnants of the European race in North America (though that might be reason enough). Rather it’s that Russia, in defying the globalist forces and reaffirming the primacy of her heritage and identity, stands today for principles that lend international legitimacy – and hence a modicum of power – to patriots everywhere resisting the enemies of their blood.

***

Qualitative differences of world-shaping consequence now clearly separate Russians and Americans on virtually every key issue of our age (more so than during the Cold War) – differences in my view that mark the divide between the forces of white preservation and those of white replacement, and, more generally, between the spirit of European man and the materialist, miscegenating depravity of the US system, which approaches the whole world as if it were a flawed and irredeemable version of itself.

In this sense, the decline of American global power and the rising credibility of Russia’s alternative model can only enhance the power of European Americans, increasing their capacity to remain true to their self-identity. US imperial decline might even eventually give them a chance to take back some of the power that decides who they are.

Putin’s discourse at the Valdai Club addressed issues (to paraphrase) related to the values underpinning Russia’s development, the global processes affecting Russian national identity, the kind of 21st-century world Russians want to see, and what they can contribute to this future.

His responses to these issues were historically momentous in being unlike anything in the West today. Cynics, of course, will dismiss his address as mere PR, though the Russian leader has a documented history of saying what he thinks – and thus ought not be judged like American politicians, who say only what’s on the teleprompter and then simply for the sake of spin and simulacra.

Foremost of Russia’s concerns, as Putin defined it in his address to the club’s plenary session, is “the problem of remaining Russian in a globalizing world hostile to national identity.” “For us (and I am talking about Russians and Russia), questions about who we are and who we want to be are increasingly prominent in our society.” In a word, Putin sees identitarianism as the central concern of Russia’s “state-civilization,” (something quite staggering when you consider that the very term [“identitarianism”] was hardly known outside France when I started translating it a decade ago). Identitarianism in the 21st century may even, as Putin implies, prove to be what nationalism and socialism were to the 20th century: the great alternative to liberal nihilism.

Like Bush, Clinton, or other US flim-flam artists, Obama could conceivably mouth a similar defense of national identity if the occasion demanded it, but never, not in a thousand years, could he share the sentiment motivating it, namely the sense that: “It is impossible to move forward without spiritual, cultural, and national self-determination. Without this we will not be able to withstand internal and external challenges, nor will we succeed in global competitions.”[6]

The operative term here is “spiritual, cultural and national self-determination” – not diversity, universalism, or some putative human right; not even money and missiles – for in Putin’s vision, Russia’s historical national, cultural, and spiritual identities are the alpha and omega of Russian policy. Without these identities and the spirit animating them, Russia would cease to be Russia; she would be nothing – except another clone of America’s supermarket culture. With her identity affirmed, as recent events suggest, Russia again becomes a great power in the world.

The question of self-determination is necessarily central to the anti-identitarianism of our global, boundary-destroying age. According to Putin, Russia’s national identity

is experiencing not only objective pressures stemming from globalisation, but also the consequences of the national catastrophes of the twentieth century, when we experienced the collapse of our state two different times [1917 and 1991]. The result was a devastating blow to our nation’s cultural and spiritual codes; we were faced with the disruption of traditions and the consonance of history, with the demoralisation of society, with a deficit of trust and responsibility. These are the root causes of many pressing problems we face.

Then, following the Soviet collapse of 1991, Putin says:

There was the illusion that a new national ideology, a development ideology [promoted by Wall Street and certain free-market economists with Jewish names], would simply appear by itself. The state, authorities, intellectual and political classes virtually rejected engaging in this work, all the more so since previous, semi-official ideology was hard to swallow. And in fact they were all simply afraid to even broach the subject. In addition, the lack of a national idea stemming from a national identity profited the quasi-colonial element of the elite – those determined to steal and remove capital, and who did not link their future to that of the country, the place where they earned their money.

Putin here has obviously drawn certain traditionalist conclusions from the failings of the former Communist experiment, as well as from capitalism’s present globalizing course.

A new national idea does not simply appear, nor does it develop according to market rules. A spontaneously constructed state and society does not work, and neither does mechanically copying other countries’ experiences. Such primitive borrowing and attempts to civilize Russia from abroad were not accepted by an absolute majority of our people. This is because the desire for independence and sovereignty in spiritual, ideological and foreign policy spheres is an integral part of our national character . . . [It’s an integral part of every true nation.]

The former Communist KGB officer (historical irony of historical ironies) stands here on the stump of that political/cultural resistance born in reaction to the French Revolution and its destruction of historical organisms.

In developing new strategies to preserve Russian identity in a rapidly changing world, Putin similarly rejects the tabula rasa contentions of the reigning liberalism, which holds that you can “flip or even kick the country’s future like a football, plunging into unbridled nihilism, consumerism, criticism of anything and everything . . .” [Like Burke, he in effect condemns the “junto of robbers” seeking to rip the traditional social fabric for the sake of short term profit, as these money-grubbers prepare the very revolution they dred.]

Programmatically, this means:

Russia’s sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity [against which America’s counter-civilizational system relentlessly schemes] are unconditional. These are red lines no one is allowed to cross. For all the differences in our views, debates about identity and about our national future are impossible unless their participants are patriotic.” [That is, only Russians, not Washington or New York, ought to have a say in determining who or what a Russian is.]

Self-criticism is necessary, but without a sense of self-worth, or love for our Fatherland, such criticism becomes humiliating and counterproductive. [These sorts of havoc-wreaking critiques are evident today in every Western land. Without loyalty to a heritage based on blood and spirit, Russians would be cast adrift in a historyless stream, like Americans and Europeans.] We must be proud of our history, and we have things to be proud of. Our entire, uncensored history must be a part of Russian identity. Without recognising this it is impossible to establish mutual trust and allow society to move forward. . .

The challenges to Russia’s identity, he specifies, are

linked to events taking place in the world [especially economic globalization and its accompanying destruction of traditional life]. Here there are both foreign policy and moral aspects. We can see how many of the Euro-Atlantic countries are actually rejecting their roots, including the Christian values that constitute the basis of Western civilisation. They are denying moral principles and all traditional identities: national, cultural, religious, and even sexual. They are implementing policies that equate large families with same-sex partnerships, belief in God with the belief in Satan.

The excesses of political correctness have reached the point where people are seriously talking about registering political parties whose aim is to promote paedophilia. People in many European countries are embarrassed or afraid to talk about their religious affiliations. Holidays are abolished or even called something different; their essence is hidden away, as is their moral foundation. And people [i.e., the Americans and their vassals] are aggressively trying to export this model all over the world. I am convinced that this opens a direct path to degradation and primitivism, resulting in a profound demographic and moral crisis. [Hence, the US-sponsored desecrations of Pussy Riot.]

What else but the loss of the ability to self-reproduce could act as the greatest testimony of the moral crisis facing a human society? Today almost all developed nations [infected with the system’s counter-civilizational ethos] are no longer able to reproduce themselves, even with the help of migration. Without the values embedded in Christianity and other world religions, without the standards of morality that have taken shape over millennia, people will inevitably lose their human dignity. We consider it natural and right to defend these values. One must respect every minority’s right to be different, but the rights of the majority must not be put into question.

Tolerant and pluralist though he is here, Putin nevertheless affirms the primacy of Russia herself. Our politicians get this 100 percent wrong, Putin only 50 percent – which puts him at the head of the class.

At the same time we see attempts to somehow revive a standardized [i.e., Americanized] model of a unipolar world and to blur the institutions of international law and national sovereignty. Such a unipolar, standardised world does not require sovereign states; it requires vassals. In a historical sense this amounts to a rejection of one’s own identity, of the God-given diversity of the world.

Russia agrees with those who believe that key decisions should be worked out on a collective basis, rather than at the discretion of and in the interests of certain countries or groups of countries. Russia believes that international law, not the right of the strong, must apply. And we believe that every country, every nation is not exceptional [as the Americans think they are], but unique, original, and benefits from equal rights, including the right to independently choose their own development path . . .

This is our conceptual outlook, and it follows from our own historical destiny and Russia’s role in global politics. [Instead, then, of succumbing to America’s suburban consumer culture and its larger dictates, Russia seeks to preserve her own identity and independence.]

Our present position has deep historical roots. Russia itself has evolved on the basis of diversity, harmony and balance, and brings such a balance to the international stage.

The grandeur of Putin’s assertion here has to be savored: against the latest marketing or policy scheme the US tries to impose on Russia, he advances his queen, pointing to a thousand years of Russian history, as he disperses America’s corrupting ploys with a dismissive smirk.

Though seeing Russia as a multiethnic/multi-confessional state that has historically recognized the rights of minorities, he insists she must remain Russian:

Russia – as philosopher Konstantin Leontyev vividly put it – has always evolved in ‘blossoming complexity’ as a state-civilisation, reinforced by the Russian people, Russian language, Russian culture, Russian Orthodox Church and the country’s other traditional religions. It is precisely the state-civilisation model that has shaped our state polity….

Thus it is that Russians, among other things, “must restore the role of great Russian culture and literature. . . to serve as the foundation for people’s personal identity, the source of their uniqueness, and their basis for understanding the national idea. . .” Following Yeats, he might have added that the arts dream of “what is to come,” providing Russians new ways of realizing or re-inventing themselves.

I want to stress again that without focusing our efforts on people’s education and health, creating mutual responsibility between the authorities and each individual, and establishing trust within society, we will be losers in the competition of history. Russia’s citizens must feel that they are the responsible owners of their country, region, hometown, property, belongings and their lives. A citizen is someone who is capable of independently managing his or her own affairs . . .

Think of how the “democratic” powers of the Americanosphere now hound and persecute whoever insists on managing his own affairs: e.g., Greece’s Golden Dawn.

The years after 1991 are often referred to as the post-Soviet era. We have lived through and overcome that turbulent, dramatic period. Russia has passed through these trials and tribulations and is returning to herself, to her own history, just as she did at other points in its history. [This forward-looking orientation rooted in a filial loyalty to the Russian past makes Putin something of an archeofuturist.] After consolidating our national identity, strengthening our roots, and remaining open and receptive to the best ideas and practices of the East and the West, we must and will move forward.

***

As an ethnonationalist concerned with the preservation and renaissance of my own people, I hope Russia succeeds not only in defending her national identity (and ideally that of others), but in breaking America’s anti-identitarian grip on Europe, so as to insure the possibility of a future Euro-Russian imperium federating the closely related white, Christian peoples, whose lands stretch from the Atlantic to the Urals.

But even barring this, Russia’s resistance to the ethnocidal forces of the US global system, will continue to play a major role in enabling European Americans trapped in the belly of the beast to better defend their own blood and spirit.

And even if Europeans should persist in their servility and the United States continues to lead its “mother soil and father culture” into the abyss, Russians under Putin will at least retain some chance of remaining themselves – which is something no mainstream American or European politician seeks for his people.

If only for this reason, I think there can never be “too much Putin,” as our Russophobes fear.

Notes

1. Desmond Fennell, Uncertain Dawn: Hiroshima and the Beginning of Post-Western Civilization (Dublin: Sanas, 1996); Julius Evola, “Disraeli the Jew and the Empire of the Shopkeepers” (1940), http://thompkins_cariou.tripod.com/id34.html [2].

2. “Boreas Rising: White Nationalism and the Geopolitics of the Paris-Berlin-Moscow Axis [3]” (2005).

3. “Against the Armies of the Night: The Aurora Movements [4]” (2010).

4. President of Russia, “Address to the Valdai International Discussion Club” September 19, 2013. http://eng.news.kremlin.ru/transcripts/6007/print [5]. (I have made several grammatical and stylistic changes to the translation.)

5. Much of my understanding of this comes from Dedefensa, “Poutine, la Russie et le sens de la crise” (September 23, 2013) at http://www.dedefensa.org/article-poutine_la_russie_et_le_sens_de_la_crise_23_09_2013.html [6].

6. Samuel P. Huntington was the last major representative of the US elite to uphold a view even vaguely affirmative of the nation’s historical culture – and he caught hell for see. Who Are We?: The Challenges to America’s National Identity (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005).

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2013/10/too-much-putin/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/putin.jpg

[2] http://thompkins_cariou.tripod.com/id34.html: http://thompkins_cariou.tripod.com/id34.html

[3] Boreas Rising: White Nationalism and the Geopolitics of the Paris-Berlin-Moscow Axis: http://www.counter-currents.com/2011/08/boreas-risingwhite-nationalism-the-geopolitics-of-the-paris-berlin-moscow-axis-part-1/

[4] Against the Armies of the Night: The Aurora Movements: http://www.counter-currents.com/2010/07/against-the-armies-of-the-night/

[5] http://eng.news.kremlin.ru/transcripts/6007/print: http://eng.news.kremlin.ru/transcripts/6007/print

[6] http://www.dedefensa.org/article-poutine_la_russie_et_le_sens_de_la_crise_23_09_2013.html: http://www.dedefensa.org/article-poutine_la_russie_et_le_sens_de_la_crise_23_09_2013.html

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : politique internationale, poutine, russie, europe, affaires européennes, actualité |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 10 octobre 2013

LE ELEZIONI TEDESCHE E LA POLITICA ESTERA

LE ELEZIONI TEDESCHE E LA POLITICA ESTERA

Marco Zenoni

Ex: http://www.eurasia-rivista.org

Il 22 settembre scorso si sono tenute in Germania le elezioni per il rinnovo del 18° Bundestag. Le elezioni, seguite in tutto il mondo con una certa attenzione vista l’importanza crescente della Federazione tedesca nell’equilibrio economico e politico globale, hanno portato dei risultati da un lato inattesi, dall’altro prevedibili. Inattesa, ad esempio, è stata l’esclusione del Partito Liberal Democratico (Freie Demokratische Partei), un partito storico nel paese, che per anni ha avuto un importante ruolo di sostegno ai governi succedutesi al parlamento tedesco. Dagli anni ’90 era inoltre divenuto un importante alleato della CDU (Cristilich Demokratische Union Deutschland). L’esclusione del FDP dal parlamento tedesco implica dei cambiamenti nel nuovo esecutivo; il ministero degli esteri del passato governo Merkel era infatti tenuto da Guido Westerwelle, membro del partito liberal democratico. Altra esclusione, meno sorprendente, è quella dell’Alternative Fur Deutschland, il partito degli “euroscettici” che si pensava avrebbe potuto rosicchiare qualche voto alla CDU, costringendo quest’ultima a rivedere in parte le proprie politiche europeiste. Di fatto, pare invece che l’AFD abbia tolto voti decisivi proprio al partito liberal democratico.

Il risultato è dunque una vittoria della politica europeista “del rigore” promossa da Angela Merkel. La maggioranza ottenuta dalla coalizione CDU/CSU non si è rivelata tuttavia sufficiente ad un governo solitario, ed anche questa volta, per la formazione del governo, sarà necessaria la collaborazione di altri partiti. Secondo i maggiori analisti è certa la formazione della cosiddetta “Großer Koalition [1]” (la grande coalizione), ovvero una coalizione tra Socialdemocratici (SPD) e CDU. L’SPD, nonostante il netto ridimensionamento (25,7% il risultato, contro il 42,5% della CDU), avrà dunque con alta probabilità un ruolo importante nel prossimo governo, il cui insediamento si prevede andrà per le lunghe. L’alternativa resta un governo sostenuto dai Verdi, un’opportunità non del tutto rigettata ma sicuramente secondaria. Il ripiego su quest’ultimi potrebbe esclusivamente essere dovuto ad un eccessivo irrigidimento da parte della SPD, a cui l’ultima “Großer Koalition [1]” è costata l’attuale sostanzioso ridimensionamento. I dirigenti del partito Socialdemocratico hanno infatti dichiarato che questa volta una coalizione si potrà fare solo attraverso una decisa convergenza di obiettivi, e non rinunciando a fondamentali prerogative.

Il risultato dunque, è la stabilità. E’ molto probabile che non si vedranno cambiamenti sostanziosi nella politica tedesca, né nei confronti dell’Unione Europea, né rispetto alle questioni economiche e politiche globali. Vale la pena dunque di analizzare quali sono le proposte in materia di politica estera da parte dei due principali schieramenti, e quale è stata la politica estera effettiva dell’ultimo governo, politica che probabilmente non muterà. Nonostante la politica estera non abbia avuto un peso centrale nella campagna elettorale, se si esclude la questione europea, entrambi i partiti hanno delle proposte chiare in merito.

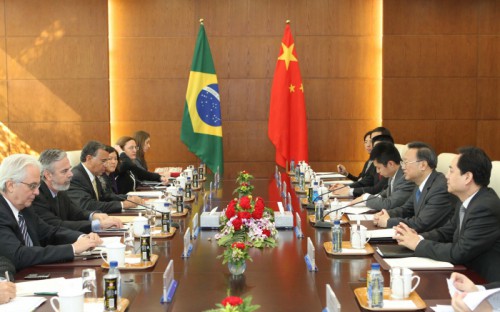

In sostanza, non sono molte le differenze fra i due programmi. In entrambi il punto centrale sembra essere la “sicurezza”, intesa come stabilità e cooperazione a vantaggio reciproco. Il programma della politica estera della CDU esordisce con un “il mondo bipolare è finito” e da qui muove alcune importanti considerazioni, economiche prima di tutto[1]. “Senza sicurezza non c’è sviluppo, e senza sviluppo non c’è sicurezza”, si potrebbe riassumere così la proposta politica del partito della Merkel, attento a cogliere ogni cambiamento in atto, e interessato a coglierne i frutti. Si muove dunque sempre da concezioni meramente economiche, sulla linea della stabilità e della cooperazione. Se quindi viene dato un peso centrale ai BRICS, a Russia e Cina in particolare, allo stesso tempo viene ribadita l’indiscutibilità dei rapporti con gli Stati Uniti e in particolare del ruolo della NATO. Per quanto riguarda la regione mediterranea e i mutamenti in atto, anche qui viene promossa la stabilità, la collaborazione con l’Unione Africana, la promozione dell’Islam moderato e l’intransigenza nei confronti dell’estremismo islamico. Se c’è una differenza, pur lieve, tra i programmi dei due partiti, questa è la centralità data agli Stati Uniti. Nel programma della CDU si legge un elogio degli Stati Uniti come “liberatori” dell’Europa dal giogo comunista e nazista, si ribadisce l’amicizia con Washington e l’intenzione di intensificare l’integrazione economica e l’interscambio commerciale. L’SPD, pur ribadendo a sua volta l’importanza dell’asse atlantico, sottolinea l’importanza dell’Asia, promuove l’intensificazione dei rapporti fra questa e l’Unione Europea. Allo stesso modo viene espressa la consapevolezza del ruolo positivo svolto dalla Cina nel continente africano, attraverso un efficiente dinamismo economico. Nel programma della SPD inoltre vi è un chiaro riferimento alla questione siriana. La soluzione, viene scritto, può essere solo diplomatica, e non militare. L’uso della forza non viene ritenuta una soluzione adeguata. E’ inoltre necessario sostenere gli Stati arabi “in transizione”[2]. Un’ultima differenza, non di meno conto, è la posizione riguardo all’ingresso della Turchia nell’Unione Europea, una questione centrale se si considera il numero di immigrati turchi in Germania. Mentre infatti la CDU si oppone all’ingresso, promuovendo comunque la cooperazione economica, l’SPD si dice favorevole anche all’effettivo ingresso, affiancata in questo anche da Verdi e Die Linke[3].

Queste dunque le linee su cui si muoverà la Germania del futuro. In perfetta coerenza con quella politica cauta e quel paziente e intenso lavoro diplomatico svolto negli ultimi anni. Nessun sensibile cambiamento di rotta dunque.

Detto di quella che sarà la politica estera tedesca, vale la pena di muovere qualche passo indietro e analizzare quella che è stata la proiezione esterna della Germania negli ultimi anni di governo Merkel.

Unione EuropeaLa politica nei confronti dell’Unione Europea negli ultimi anni non è assolutamente mutata. La posizione resta quella dell’intransigenza e del rigore economico, nonostante l’ambiguità cui questa politica conduce. La Germania ha infatti bisogno di un’Unione Europea globalmente stabile e economicamente competitiva, seppur il rigore promosso dalla CDU non faccia che aggravare le condizioni economico-finanziarie dei paesi periferici (i cosiddetti PIIGS). Se infatti il rapporto economico con i paesi emergenti va rafforzandosi, l’export nella regione europea rimane fondamentale. Il che suggerirebbe una politica più morbida nei confronti dei vicini europei, oltre ad una cooperazione al fine di stabilizzare le economie e promuoverne lo sviluppo. Politiche finora accantonate dalla CDU. In questo senso un ingresso in parlamento dell’AFD avrebbe probabilmente potuto portare se non altro ad un leggero cambiamento, ammesso che il partito degli economisti, guidato da Bernard Lucke, avrebbe potuto avere un seppur minimo ruolo all’interno di un ipotetico governo. A queste ambiguità si aggiunga il totale disaccordo sulla proiezione esterna dell’Unione Europea, affrontata in modo diverso, se non opposto, dalle principali potenze europee. Basta vedere la netta opposizione tra la Francia e la Germania (rapporto che fra l’altro va indebolendosi anche a causa del rallentamento economico dei primi) sulle questioni della regione mediterranea, quella siriana su tutte. Francois Hollande è infatti stato sin da subito tra i più grandi sostenitori dell’intervento armato in Siria, mentre Angela Merkel si è sempre detta contraria a questa opzione, nonostante le recenti aperture al G20, dove comunque non è stato menzionato l’uso della forza.

ONU e missioni internazionaliL’ONU è il meccanismo diplomatico in cui la Germania si confronta ed impegna maggiormente, in piena coerenza con la ricerca di stabilità e cooperazione promossa negli ultimi anni. Da anni ormai la Germania chiede un seggio permanente in seno al consiglio di sicurezza, in virtù anche dell’apporto dato dal paese alle Nazioni Unite: con l’8% circa del contributo al budget dell’organismo, la Germania è infatti il terzo contribuente in assoluto, oltre a coprire finanziariamente per l’8% delle missioni di peacekeeping [4]. A ciò si aggiunga che tutt’ora la Germania è impegnata in Kosovo attraverso la missione internazionale KFOR, in Afghanistan con l’ISAF (missione questa per conto della NATO) e con l’UNIFIL, missione di peacekeeping in Libano.

La Germania partecipa esclusivamente a missioni a basso rischio e solo per missioni di pace. Un “pacifismo” spesso criticato all’interno della NATO, nonostante in Afghanistan la Germania abbia in impiego 4.100 soldati, 35 i morti totali nel corso degli anni[5].

D’altronde il ministro degli esteri in uscita, Guido Westerwelle, si disse a suo tempo contrario sia all’UNIFIL che all’intervento in Libia, cui infatti la Germania non ha partecipato. Stesso discorso vale per la Siria, altro paese in cui l’intervento viene fermamente condannato dal governo tedesco, nonostante Westerwelle stesso abbia dichiarato di non aver apprezzato alcuni atteggiamenti di Cina e Russia nel consiglio di sicurezza[6].

Seppur i rapporti con l’alleato d’oltreoceano non siano mai stati messi in discussione, le questioni recentemente emerse hanno senz’altro portato a qualche ripensamento. Prima di tutto, la Germania considera evidenti gli errori commessi dagli Stati Uniti negli ultimi anni (intervento in Iraq, in Libia, ad esempio). Ma il punto cruciale, non di rottura ma senz’altro uno scossone, è stata la questione dello spionaggio. Dopo lo scandalo della NSA infatti, la Germania ha cancellato il patto ormai cinquantennale di sorveglianza (patto firmato da Germania, Francia, Gran Bretagna e Stati Uniti). La Germania d’altronde si è scoperta come il paese europeo più spiato dall’alleato, e questo non è certamente un caso. E’ infatti risaputo il timore che si prova a Washington nei confronti della crescita economica tedesca, una crescita che finora rimane nei ranghi designati, ma che presto si troverà a doversi confrontare con delle scelte, inevitabilmente. Anche la recente amicizia fra Germania e Cina non è certo vista di buon occhio dagli Stati Uniti. Nonostante ciò Westerwelle stesso ha ribadito che con gli Stati Uniti gli interessi condivisi sono fin troppi per poter solo considerare una pur tiepida rottura. L’irrisolta questione siriana, l’espansione economica tedesca e la sempre maggior cooperazione con Russia e Cina avranno sicuramente come conseguenza qualche riflessione da parte di entrambi gli schieramenti.

CinaSe per gli Stati Uniti la Germania come alleato, pur vacillando, rimane una sicurezza indipendentemente dal cancelliere insediato, la Cina ha guardato con apprensione alle recenti elezioni[7]. Secondo alcuni politologi cinesi infatti, il Partito Comunista Cinese temeva che una (seppur improbabile) vittoria da parte del centro-sinistra, con la formazione di un governo sostenuto potenzialmente da Verdi e Linke, avrebbe potuto portare alla ribalta alcune delle tematiche tradizionalmente portate avanti dall’occidente nel tentativo di penetrare negli affari interni cinesi, una su tutte la questione dell’indipendenza tibetana, un tasto su cui la Cina non ha intenzione trattare. Anche con il governo Merkel non sono tuttavia mancate le frizioni, ad esempio nel 2007, quando la cancelliera ricevette a Berlino il Dalai Lama, una provocazione agli occhi del governo cinese. Nonostante queste frizioni, il lavoro, considerato pragmatico, del governo tedesco viene visto positivamente dalla Cina e il rapporto fra i due paesi, già decisamente migliorato, sembra andare in direzione di un’ulteriore cooperazione, non solo in campo economico, seppur sia questo il settore preponderante.

Tenuta dunque considerazione di quella che finora è stata la politica tedesca e di quello che è il programma dei due principali partiti è senz’altro difficile prevedere drastici cambiamenti di rotta. Nonostante ciò, il nuovo governo si troverà comunque ad affrontare un equilibrio geopolitico in mutamento, un mutamento sostanziale che non potrà essere trascurato dal governo tedesco. Sarà dunque interessante vedere come risponderà la Germania alle problematiche che presto si presenteranno.

*Marco Zenoni è laureando in Relazioni Internazionali all’Università di Perugia

[1] Programma politico della CDU, consultabile online.

[2] Programma politico dell’SPD, consultabile online.

[3] http://temi.repubblica.it/limes/la-germania-al-voto-si-interroga-sul-suo-ruolo-nel-mondo/51996 [2]

[4] http://www.ispionline.it/it/articoli/articolo/europa/la-politica-estera-della-germania-9018 [3]

[5] Ibidem

[6] http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/interview-with-german-foreign-minister-guido-westerwelle-a-900611.html [4]

[7] http://www.ispionline.it/it/articoli/articolo/europa/la-politica-estera-della-germania-9018 [3]

Article printed from eurasia-rivista.org: http://www.eurasia-rivista.org

URL to article: http://www.eurasia-rivista.org/le-elezioni-tedesche-e-la-politica-estera/20184/

URLs in this post:

[1] Großer Koalition: http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/seehofer-kritisiert-spd-mitgliederbefragung-a-925032.html

[2] http://temi.repubblica.it/limes/la-germania-al-voto-si-interroga-sul-suo-ruolo-nel-mondo/51996: http://temi.repubblica.it/limes/la-germania-al-voto-si-interroga-sul-suo-ruolo-nel-mondo/51996

[3] http://www.ispionline.it/it/articoli/articolo/europa/la-politica-estera-della-germania-9018: http://www.ispionline.it/it/articoli/articolo/europa/la-politica-estera-della-germania-9018

[4] http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/interview-with-german-foreign-minister-guido-westerwelle-a-900611.html: http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/interview-with-german-foreign-minister-guido-westerwelle-a-900611.html

[5]

- : http://twitter.com/intent/tweet?text=LE%20ELEZIONI%20TEDESCHE%20E%20LA%20POLITICA%20ESTERA%20-%20http%3A%2F%2Fwww.eurasia-rivista.org%2Fle-elezioni-tedesche-e-la-politica-estera%2F20184%2F%20

- : https://mail.google.com/mail/?view=cm&fs=1&to&su=LE%20ELEZIONI%20TEDESCHE%20E%20LA%20POLITICA%20ESTERA&body=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.eurasia-rivista.org%2Fle-elezioni-tedesche-e-la-politica-estera%2F20184%2F&ui=2&tf=1&shva=1

- : http://www.stumbleupon.com/submit?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.eurasia-rivista.org%2Fle-elezioni-tedesche-e-la-politica-estera%2F20184%2F&title=LE%20ELEZIONI%20TEDESCHE%20E%20LA%20POLITICA%20ESTERA

- : http://www.google.com/reader/link?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.eurasia-rivista.org%2Fle-elezioni-tedesche-e-la-politica-estera%2F20184%2F&title=LE%20ELEZIONI%20TEDESCHE%20E%20LA%20POLITICA%20ESTERA&srcURL=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.eurasia-rivista.org%2Fle-elezioni-tedesche-e-la-politica-estera%2F20184%2F&srcTitle=eurasia-rivista.org+Rivista+di+studi+Geopolitici

[9] Image: http://www.blinklist.com/index.php?Action=Blink/addblink.php&Url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.eurasia-rivista.org%2Fle-elezioni-tedesche-e-la-politica-estera%2F20184%2F&Title=LE%20ELEZIONI%20TEDESCHE%20E%20LA%20POLITICA%20ESTERA

- : http://www.myspace.com/Modules/PostTo/Pages/?u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.eurasia-rivista.org%2Fle-elezioni-tedesche-e-la-politica-estera%2F20184%2F&t=LE%20ELEZIONI%20TEDESCHE%20E%20LA%20POLITICA%20ESTERA

- : http://reddit.com/submit?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.eurasia-rivista.org%2Fle-elezioni-tedesche-e-la-politica-estera%2F20184%2F&title=LE%20ELEZIONI%20TEDESCHE%20E%20LA%20POLITICA%20ESTERA

- : http://news.ycombinator.com/submitlink?u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.eurasia-rivista.org%2Fle-elezioni-tedesche-e-la-politica-estera%2F20184%2F&t=LE%20ELEZIONI%20TEDESCHE%20E%20LA%20POLITICA%20ESTERA

- : http://sphinn.com/index.php?c=post&m=submit&link=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.eurasia-rivista.org%2Fle-elezioni-tedesche-e-la-politica-estera%2F20184%2F

[14] Tweet: https://twitter.com/share

00:10 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : allemagne, politique internationale, europe, affaires européennes, angela merkel, actualité |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

La finance-Système réduite au Saudi Arabia Dream

La finance-Système réduite au Saudi Arabia Dream

Ex: http://www.dedefensa.org

L’explication technique et savante des arcanes extraordinaires de la situation du monde de la finance-Système, dont le centre est évidemment américaniste, a régulièrement échoué à nous en donner une perception à la fois simple et claire. Cela vaut essentiellement depuis l’événement de l’automne 2008 qui était en lui-même extraordinaire, et qui a entraîné des développements eux-mêmes extraordinaires, faisant évoluer la crise de ce qui paraissait un accident très grave (selon la perception rassurante que le Système voulait en donner) en un phénomène inscrit dans l’infrastructure crisique, c’est-à-dire une situation de crise permanente où ce que la raison perçoit comme extraordinaire dans le sens de monstrueux est devenu la norme de l’évolution.

On comprend qu’aujourd’hui cette question de la perception et de la “compréhension” plutôt symbolique de cette situation crisique infrastructurelle est plus insistante que jamais, alors que Washington est en crise de government shutdown et s’approche du moment où, paraît-il, se posera l’autre question institutionnelle du relèvement du plafond de la dette. (En principe le 17 octobre, mais rien n’est plus incertain que la prévision datée, aujourd’hui, d’une semaione à l’autre.) Le département US du trésor fait son travail, qui est technique mais a aussi dimension politicienne en ajoutant un élément de pression sur les protagonistes de la crise government shutdown, essentiellement les républicains adversaires d’Obama, pour qu’ils cèdent devant la perspective ; la dite perspective, par rapport à la dette, étant décrite évidemment comme apocalyptique, – ce qui n’est, après tout, qu’un risque prévisionnel mineur dans le cadre crisique où nous vivotons.

«The federal government is expected to exhaust its cash reserves by October 17 and if US lawmakers do not reach an agreement to raise the nation’s debt ceiling, the government will not be able to pay its bills and will default on its legal obligations. “In the event that a debt limit impasse were to lead to a default, it could have a catastrophic effect on not just financial markets but also on job creation, consumer spending and economic growth,” said the Treasury in a report on Thursday. “Credit markets could freeze, the value of the dollar could plummet, US interest rates could skyrocket, the negative spillovers could reverberate around the world, and there might be a financial crisis and recession that could echo the events of 2008 or worse,” warned the Treasury.» (PressTV.ir, le 3 octobre 2013.)

Les analyses financières et économistes abondent, la plupart étant sur fond prospectif d’effondrement et selon des mécanismes viciés, pervers, etc., pour pouvoir donner une explication satisfaisante d’une situation marquées par des déséquilibres colossaux, jusqu’au plus basique d’entre tous qui est l’inégalité engendrant un déséquilibre phénoménal entre l’extrême minorité des riches et l’extrême majorité des pauvres, – le fameux symbole des 1% versus les 99%. Ce “déséquilibre colossal”-là n’a jamais été aussi grand selon l’histoire statistique du domaine. (On vient de dépasser les pires situations statistiques de l’inégalité riches-pauvres, datant des années 1920 aux USA.) Finalement, ces diverses et très nombreuses supputations et analyses, chacune avec leur allant et leur apparente rationalité, toutes avec leur langage assuré du jugement à qui on ne la fait pas, ne donnent pas une image satisfaisante de la situation. Il leur manque l’ampleur, la représentation concrète acceptable, c’est-à-dire ce qui nourrit le jugement d’une manifestation assez claire de l’écho d’une certaine vérité de la situation. Cette faiblesse est aujourd’hui mise en lumière par la pression des événements, c’est-à-dire de la crise washingtonienne qui comprend évidemment des éléments techniques du domaine financier et des facteurs économiques fondamentaux, mais qui renvoie également à d’autres domaines, politiques, sociaux et psychologiques, essentiellement dans le domaine du système de la communication pour leur exposition.

Ainsi nous semble-t-il qu’une description imagée, hyperbolique et symbolique à la fois, avec des références et des analogies nourries de concepts généraux non-financiers qui nous sont familiers, permet de mieux saisir l’ampleur des déséquilibres et des déformations monstrueuses de la situation. Un document qui va dans ce sens, du fait de la verve imagée de la personne concernée, est une interview de Max Keyser, spécialiste boursier et spécialiste des aspects absolument virtualistes de la situation financière ; et aussi, essentiellement présentateur de l’émission Keyser Report de la station Russia Today, qui lui fait obligation de s’exprimer en langage imagé et effectivement hyperbolique et symbolique. Cette interview a été diffusée sur Russia Today le 3 octobre 2013 et nous en reproduisons les passages justement non-techniques, où la description de l’ensemble-Système économico-financier fait appel à des notions hors de la technique financière. On a ainsi, à notre sens une meilleure appréciation de la situation.

Russia Today : «There’s a lot of hype and some would say overreaction around all of this but the tell-tale sign is the markets. They haven’t reacted negatively. Is there really a crisis here?»

Max Keyser : «I think we should take the words of Warren Buffet to heart. He basically described the Federal Reserve Bank and the American economy as one giant hedge fund. And he is absolutely correct. [...] Remember America is run by what I call financial jihadists who are basically suicide bankers. Warren Buffett, of course, is one of these suicide bankers and America, from the outside of course, looks like they’re trying to commit financial suicide. But that’s what a financial jihadist does, or a suicide banker. They blow themselves up for their cause and in this case it’s market fundamentalism, a belief in the profit – not the prophet.»

Russia Today : « But other tell-tale signs of the economy improving are there, Max. Are we to believe the economic indicators which suggest the US economy is on the up?»

Max Keyser : « [...] ... What will happen here – this is the outcome, there’s two outcomes – either the Federal Reserve Bank will increase their monthly buyback of bonds from $85 billion a month to $120 or $130 billion a month, or America defaults on its sovereign debt like it did in 1971 when it closed the gold window. Those are the two outcomes. So what we see here is jockeying between these two powerful sources in Washington, Congress, and the Senate. By the way - they all own stocks. Insider trading is legal. They’re all trading this information, they’re on their little phones and they’re trading stocks up and down and making money at the expense of the American people because they are financial terrorists as well. Financial terrorists have captured the American economy. I mean that’s plain and simple. Warren Buffet hit the nail on the head – America is just one giant hedge fund.»

Russia Today : «But they will raise the debt ceiling won’t they? Or will they not, because Obama is clearly worried about that? They’re arguing about Obama’s health care. What’s going to happen with that crisis?»

Max Keyser : «[...] ... That’s the insider’s scoop; I’m telling you how to make money on this façade, this Kabuki theater that has become America. America is the most watched soap opera in the world right now; it’s a huge hedge fund. You’ve got CNBC covering it like it’s an episode from “Breaking Bad,” the popular show about methamphetamine on cable TV. Ben Bernake and Barack Obama, you can almost picture them in the back room cooking up some meth and selling it on the street to finance their habit, which is defense spending, torture, extraordinary rendition, bombing people overseas, droning people that costs a lot of money. The only way they can finance that is by treating the entire economy like it’s a hedge fund where they just extract wealth second by second, manipulating markets, trading inside information. JP Morgan, Lloyd Blankfein, HSBC, Barclays, inside trading, market manipulation; they’ve been caught at it time and time again. Laundering money from drug cartels in the face of HSBC over and over again. It’s just drugs, insider trading, market manipulation, and Warren Buffett. That’s all that’s left in America.»

Russia Today : «You’re great with the plot lines so how is this particular episode going to end? The episode of the federal government shutdown. Is it going to end soon? Could it drag on for three weeks like we’ve seen in the past?»

Max Keyser : « A lot of people get hurt but the people in Washington consider the American public to be expendable. They don’t need the American public. They don’t need their taxes, they don’t need them working – because when they need money they just print it. It’s like Saudi Arabia in America. In Saudi Arabia when they need more money they just pump more oil. They don’t need the population, that’s why they live in destitute and why there’s so much poverty in Saudi Arabia. It’s the same thing in America – there’s a huge amount of poverty because... when they need some cash, they just get Ben Bernake to print it. It’s Saudi Arabia, it’s called the new American dream. The Saudi Arabian dream is alive in America.»

Ayant lu cette interview, vous ne savez absolument pas ce qui va se passer ; ou plutôt, nuance de taille et de bonne santé mentale, vous ne pouvez croire une seconde que vous savez absolument ce qui va se passer. Cela vous mettra temporairement dans une position d’infériorité lors de la conversation de salon ou de la discussion de café du jour, quand chacun affirme sa conviction et sa propre perspective pêchée chez son analyste préféré pour annoncer le futur catastrophique et immédiat. Ce n’est pas plus mal car personne, à notre sens, n’est évidemment capable d’une telle prévision, disons sur les quinze jours (passé le 17 octobre), ou même sur les trois prochains jours, sur la situation à Washington et le bouleversement mondial annoncé. Cela n’a aucune importance car nous n’avons pas à annoncer le bouleversement mondial, puisque nous sommes en son cœur, que nous l’expérimentons chaque jour, chaque minute, sans trop nous préoccuper de le savoir.

La description de Keyser est beaucoup plus intéressante parce qu’elle nous instruit sur l’essentiel en laissant l’accessoire (la prévision, dito la divination) à la salvatrice inconnaissance. Elle nous instruit sur la vérité du Système, qui singe les situations les plus abracadabrantesques nées du développement délirant de lui-même (le Système se singe lui-même), depuis 9/11 et surtout depuis l’automne 2008. Vous ne savez pas ce qui va se passer, – et, en cela, bien installé dans la lucidité, – mais vous avez une idée assez sympathique de la façon dont cette farce grotesque et eschatologique est en train de se dérouler. Vous savez au moins, ce qui est un sommet de l’art du grotesque eschatologique dont il importe d'être instruit, que l’American Dream s’est transmuté en Saudi Arabia Dream... Cela permet de continuer à rêver, occupation semble-t-il importante pour leurs psychologies endolories.

00:07 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : finance, système, crise, politique internationale, arabie saoudite |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Arabische landen en Israël proberen samen toenadering VS tot Iran te stoppen

Arabische landen en Israël proberen samen toenadering VS tot Iran te stoppen

Iraanse generaal: Obama heeft zich overgegeven

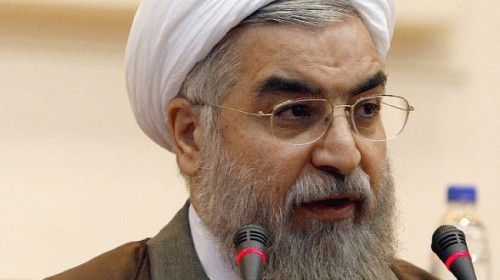

Na 5 jaar dreigen met militair ingrijpen kampt de Israëlische premier Netanyahu (hier tijdens zijn VN-toespraak eerder deze week) met een geloofwaardigheidsprobleem. Inzet: in Iran wordt Obama als krijgsgevangene van generaal Soleimani afgebeeld.

Het op het laatste moment annuleren van een ogenschijnlijk zekere Amerikaanse aanval op Syrië was een forse streep door de rekening van Saudi Arabië, de Arabische Golfstaten en Israël. De Arabieren en Israëliërs hebben dan ook de bijna onwaarschijnlijke stap gezet hun diplomatieke krachten te bundelen, om te voorkomen dat president Obama zijn toenadering tot Iran doorzet en definitief het omstreden Iraanse nucleaire programma accepteert.

Briljante Putin voorkomt oorlog

De landen op het Arabische schiereiland zijn aartsvijanden van Iran. Hetzelfde geldt voor de Joodse staat Israël. Omdat Syrië de krachtigste bondgenoot van de islamitische Republiek is, en beide landen samen de shi'itische terreurbeweging Hezbollah in Libanon steunen, lobbyden zowel de (soennitische, salafistische en wahabistische) Arabieren als de Israëliërs in Washington voor een militaire aanval op het regime van de Syrische president Assad.

De Russische president Vladimir Putin gooide echter roet in het eten met een voorstel dat best briljant mag worden genoemd. Mede door zijn eigen 'rode lijn', het gebruik van chemische wapens, zat Obama behoorlijk in de knel en kon hij, ondanks het massale verzet van het Congres en de Amerikaanse bevolking, weinig anders dan marineschepen en vliegtuigen bevelen zich gereed te maken voor de aanval op Syrië. Plotseling bood Putin hem echter een uitweg door Syrië over te halen akkoord te gaan met het vernietigen van het chemische wapenarsenaal. (3)

Wereld opgelucht, Israël en Arabieren niet blij

De wereld haalde opgelucht adem, zeker omdat veel analisten en Midden Oosten experts hadden voorspeld dat een aanval op Syrië wel eens een nieuwe grote regionale oorlog zou kunnen veroorzaken, en mogelijk zelfs de Derde Wereldoorlog. Zo'n omvangrijk militair conflict zou de genadeklap betekenen voor de toch al zeer wankele wereldeconomie.

De Arabieren en Israëliërs laten het er echter niet bij zitten, zeker niet nu president Obama tot hun afgrijzen openlijk toenadering zoekt tot Iran, en bereid lijkt om het omstreden nucleaire programma van het land te accepteren. Voor de duidelijkheid: het gaat niet om Irans recht op kernenergie, zoals de mullahs in Teheran voortdurend beweren. Zoals we onlangs opnieuw uitlegden is de uraniumverrijking tot 20%, wat bevestigd wordt door zowel het IAEA als Iraanse officials, totaal onnodig voor kernenergie, en dient -na verdere verrijking- enkel voor de productie van kernwapens.

Iran ontkende jarenlang uraniumverrijking

Wat de rest van de wereld gemakshalve ook vergeet is dat Iran jarenlang heeft ontkend dat het uranium verrijkte. Pas toen Westerse satellieten en inlichtingendiensten harde, onontkenbare bewijzen leverden, erkenden de leiders in Teheran plotseling dat ze in het geheim toch verrijkingsfabrieken hadden gebouwd, al haastten ze zich te verklaren dat deze enkel voor vreedzame doeleinden zouden worden gebruikt.

De huidige president Hassan Rouhani was 6 jaar geleden, toen nog hoofdonderhandelaar namens de islamitische Republiek, openlijk trots op het misleiden van het Westen, dat hij jarenlang aan het lijntje had weten te houden met de bewering dat Iran geen uranium verrijkte, terwijl er ondertussen op geheime locaties duizenden verrijkingscentrifuges werden geïnstalleerd.

Tellen we hier de regelmatige oorlogszuchtige taal van Iraanse militaire en geestelijke officials aan het adres van de Arabische Golfstaten en Israël bij op, dan wekt het geen verbazing dat de meeste landen in het Midden Oosten nauwelijks vertrouwen hebben in de plotselinge, zogenaamd goede bedoelingen van Iran.

Unieke samenwerking Arabische landen en Israël

Medewerkers van de Israëlische premier Netanyahu maakten gisteren bekend dat hoge officials uit Saudi Arabië en andere Arabische Golfstaten in Israël hebben overlegd over een gezamenlijke strategie, waarmee voorkomen moet worden dat Obama zijn softe benadering van Iran doorzet.

Nog nooit eerder vond er in de Joodse staat op zo'n hoog niveau overleg over samenwerking plaats tussen de Arabieren en Israëliërs, normaal gesproken vijanden van elkaar. Het is des te meer een overduidelijk signaal dat de Arabische oliestaten en Israël zeer ontevreden zijn over het wispelturige en onberekenbare beleid van president Obama.

Zorgen in Europa over nieuwe koers VS

Zelfs in het doorgaans zo passieve en timide Europa groeien de zorgen over Amerika's toenadering tot Iran. Duitse en Franse diplomaten drongen bij Israël zelfs op een harde opstelling aan, hopende dat Obama hiermee zou kunnen worden afgeremd. In sommige Europese landen dringt langzaam het besef door dat Obama hen slechts heeft gebruikt voor de jarenlange onderhandelingen met Iran, en hen nu laat vallen voor directe overeenkomsten met de theocratische leiders in Teheran.

Premier Netanyahu hield tijdens zijn recente VN-toespraak dan ook vast aan zijn eis dat Iran zijn nucleaire programma moet ontmantelen, en onderstreepte bovendien dat Israël nog steeds bereid is desnoods alleen in te grijpen. Ondanks het feit dat Iran hier de spot mee dreef -tenslotte dreigt Netanyahu hier al jaren mee, en heeft hij nog altijd niets gedaan-, zijn de shi'itische leiders wel degelijk bevreesd voor Israëls militaire macht.

Netanyahu's invloed in Washington tanende

Netanyahu's ferme taal was mogelijk nog meer aan het adres van het Witte Huis gericht. De Amerikaanse ambassadeur voor Israël, Dan Shapiro, was zichtbaar niet blij met de openlijke poging van de Israëlische premier om Obama's nieuwe Iranstrategie te dwarsbomen. De premier van de Joodse staat beseft echter dat hij Obama hoogstwaarschijnlijk niet van zijn nieuwe koers zal kunnen doen afzien, en verwacht dan ook dat de sancties tegen Iran -die het land op de rand van de afgrond hebben gebracht- binnenkort zullen worden verlicht.

De Israëlische leider ziet zich nu gesteld voor de lastige taak zijn tanende geloofwaardigheid, het gevolg van vijf jaar lang dreigen maar in werkelijkheid niets doen, te repareren. Of dat hem gaat lukken is maar de vraag, want nu het islamitische regime in Teheran tot de conclusie is gekomen dat een Amerikaanse aanval definitief van de baan is, vermoedt men dat ook Israël feitelijk heeft afgezien van militair ingrijpen. De komende tijd zal Iran dus proberen om de kloof tussen Israël en de VS verder te vergroten. (1)

Obama afgebeeld als krijgsgevangene van Iraanse generaal

De verzoenende taal van Obama tijdens zijn VN-toespraak vorige week wordt in Iran als een Amerikaanse nederlaag opgevat. De Iraanse Quds strijdkrachten publiceerden een foto van Obama in uniform, met zijn handen boven zijn hoofd als een krijgsgevangene. Boven hem het gezicht van de commandant van de Quds strijdkrachten, generaal Qasem Soleimani. De tekst op de afbeelding: 'In de niet al te verre toekomst - Eén Qasem Soleimani is genoeg voor al de vijanden van dit land.'

Bovendien voegde Seyed Hosseini, lid van de parlementaire commissie voor Nationale Veiligheid en Buitenlands Beleid, daar aan toe dat Iran weliswaar instemt met het Non-Proliferatieverdrag, maar nooit het aanvullende protocol zal ondertekenen. Dat betekent dat het IAEA geen toestemming krijgt om ter plekke te verifiëren of Iran zich inderdaad aan de regels houdt. Hosseini onderstreepte tevens dat Teheran geen enkele opschorting van het nucleaire programma zal accepteren.

Iran toont nieuwe raketten

Generaal Yahya Safavi, voormalig hoofdcommandant van de Revolutionaire Garde en thans speciaal adviseur van opperleider Ayatollah Khamenei, zei dat Amerika eindelijk begrijpt dat het 'niet op kan tegen het machtige Iran. Natuurlijk zal Iran agressief zijn eisen aan Amerika blijven stellen.'

Enkele weken geleden toonde het islamitische regime tijdens een militaire parade vol trots 30 nieuwe ballistische raketten met een bereik van 2000 kilometer. Deze raketten kunnen -behalve natuurlijk Israël- heel het Midden Oosten bereiken, en ook de Europese hoofdsteden Athene, Boekarest en Moskou. De Iraanse leiders verklaarden vol bravoure dat de Iraanse militaire kracht de machtsbalans in het Midden Oosten en zelfs de wereld zal veranderen. (2)

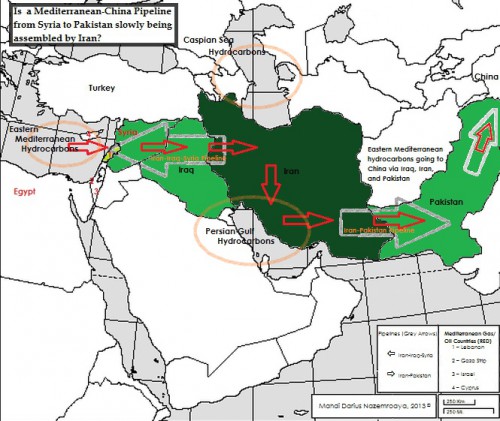

Hoog explosief kruitvat

De hele regio is hoe dan ook één groot hoogexplosief kruitvat, waar verschillende (wereld)machten een complex geopolitiek schaakspel tegen elkaar spelen, waarvan de uitkomst ongewis is - behalve dat eigenlijk alle analisten verwachten dat vroeg of laat de vlam in de pan zal slaan. Eén van de belangrijkste, in de media vrijwel onbelichte beweegreden is de controle over olie en gas, en daarmee over energie en miljardeninkomsten (zie linken onderaan voor meer uitleg). Voorlopig lijkt het blok Rusland-Iran-Irak-Syrië-Hezbollah de eerste slag te hebben gewonnen van het blok VS-Europa-Saudi Arabië-Golfstaten-Turkije-Israël.

Xander

(1) DEBKA

(2) World Net Daily

(3) KOPP

Zie ook o.a.:

01-10: Iran heeft nog voor drie maanden geld en staat op instorten

29-09: 'Israël wordt uitgelokt tot nieuwe preventieve aanval in Syrië'

26-09: CIA-klokkenluider: VS levert rechtstreeks wapens aan Al-Qaeda

25-09: Iraanse president Rohani openlijk trots op misleiden Westen

20-09: Turkije erkent leveren wapens aan Al-Qaeda en wil oorlog tegen Syrië

20-09: Deal Amerika-Rusland over Syrische chemische wapens wankelt (/ Obama schrapt wet die leveren wapens aan Al-Qaeda verbiedt)

15-09: Syrische rebellen passen Nazi-methoden toe bij afdwingen Sharia (/ Rebellen woedend dat VS geen oorlog tegen Assad begint)

14-09: Inlichtingen-insider: Mogelijk alsnog oorlog tegen Syrië door enorme false-flag aanslag

08-09: (/ Uitvoerig bewijs dat chemische aanval een provocatie van door Turkije en Saudi Arabië gesteunde oppositie was

06-09: VS, Rusland en China bereid tot oorlog over Syrië om controle over gas en olie (/ 'Rusland valt Saudi Arabië aan als Amerika ingrijpt in Syrië')

02-09: (/ Saudi Arabië en Golfstaten eisen massale aanval op Syrië)

02-08: Nieuwe president Iran: Israël is wond die verwijderd moet worden

31-08: 'Binnenkort mega false-flag om publiek van oorlog te overtuigen'

27-08: Inlichtingen insider: Derde Wereldoorlog begint in Syrië

30-07: 9e Mahdi Conferentie: Iran waarschuwt dat Armageddon nabij is

05-06: Gatestone Instituut: VS helpt herstel Turks-Ottomaans Rijk

2012:

27-11: IAEA ontdekt schema's voor krachtige Iraanse kernbom

09-10: Overgelopen topofficial Iran bevestigt vergevorderd kernwapenprogramma

09-07: Ayatollah Khamenei: Iran moet zich voorbereiden op 'het einde der tijden'

22-05: Stafchef Iraanse strijdkrachten herhaalt hoofddoel: Totale vernietiging Israël

16-05: Ayatollah Khamenei tegen oud premier Spanje: Iran wil oorlog met Israël en VS

25-04: Iran bereidt zich voor op 'laatste 6 maanden': kernoorlog en komst Mahdi

00:05 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : arabie saoudite, israel, états-unis, iran, politique internationale, géopolitique, moyen orient, proche orient |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Geopolitics and Islam

Geopolitics and Islam

Ex: http://orientalreview.org

The geopolitical changes that have taken place at the beginning of the 21st century within the nations of the Islamic world, and which would appear to be the culmination of many spontaneous factors, are, in fact, a manifestation of a very complex qualitative shift in the global balance of power. For some political analysts, all of this can be attributed to merely the shortsighted games of politicians from the most powerful nation in the world, the United States, a legacy of their apparent intellectual shortcomings and strategic myopia.

Of course the Americans manage to have a hand in almost everything that occurs in the world today. And to their credit, they are adept at defending their own national interests. But in order to identify the true origins of the current disturbances, one must look atmore than just the events of recent years, taking a wider view of the historical perspective.

The United States is fully aware that in the Middle East, the entire twentieth century marched under the banner of the Islamic intellectual revival. But that was brought home to the Americans all the more acutely during the Islamic revolution in Iran in 1979, and later – at the dawn of the new millennium, during the upheavals caused by the tragic events of September 11, 2001.

After centuries of stagnation, Islamic intellectuals of the late 19th – early 20th centuries, including Islamic reformers, educators, and fierce opponents of colonialism, such as Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani, Abd al-Rahman al-Kawakibi, Syed Ahmad Khan, Muhammad Abduh, and Rashid Rida, as well as representatives of the Tatar Revival Movement (Jadidism), signaled the beginning of this intellectual renaissance. They set out to try to make sense of the role Muslims would play in the new world that was to come, and, above all, to come to grips with the social essence of Islamic doctrine and designate the place of the state in the development and modernization of contemporary society. Among the ideas of these reformers, the common thread was the notion that Islam should be at the forefront of human development, and that the Muslim world was obliged to ensure the well-being of not only its own faithful subjects, but also those of other faiths, a provision that had been the hallmark of the Caliphate since its golden age.

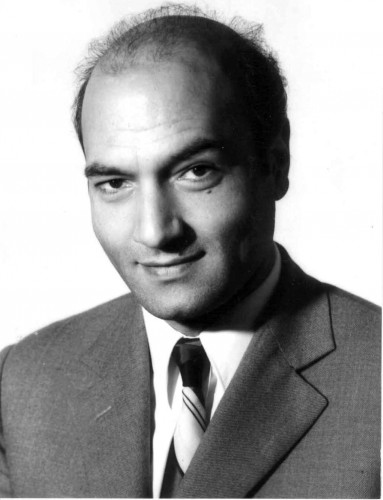

Dr. Ali Shariati

In the mid-20th century these ideas were most clearly manifested in the teachings of Ali Shariati, who made a significant contribution to the development of the social doctrine of Islam. The strict system of Shiite hierarchy helped spread Shariati’s views among Iranian clerics.

The fruits of these teachings were the Islamic revolution of 1979, under the direction of its charismatic leader, Ayatollah Khomeini. In the past,the primary focus was on the backwardness of that semi-colonial state, but now the Islamic Republic of Iran is over thirty years old and has become a leading regional power that has made great intellectual strides. (For example, by 2013 Iran had risen to 17th place in the global academic rankings, and the pace of its scientific advances has outstripped almost all major countries, including China. The state plans to increase public spending on research from the current 1% of GDP to 4% in 2029, and by 2019 the Iranians intend to send a man into space aboard their own rocket.) All this demonstrates the real potential of true political Islam.

The example of Iran, as well as the prospect that the residents of the Middle East might suddenly decide to channel their combined wealth and potential to serve the goals of their own development, has put the Americans more than a bit on edge.

The aging and weakening West has sensed a rival in the resurgent Islamic East. In the real world, Shiite Islam has demonstrated a powerful capacity to mobilize, plus the ability to defend its own interests (although in fact, Shiites make up only 15% of the 1.6 billion Muslims worldwide). If Sunni Islam were likewise able to show evidence of such success, American analysts predict that the consequences could pose a serious challenge to the United States. It is no coincidence that many US politicians have been open about the fact that the more the Islamic nations are rocked by internal wars and strife, the easier it will be for the US to ensure its hegemony. Thus, the primary goal of the United States at this stage is to split the Islamic and Arab world as much as possible and to take advantage of any means necessary to promote the emergence of new hotbeds of ongoing tension, including the use of provocation in regard to weapons of mass destruction. This leads to the desire to create docile regimes, regardless of whether they are religious or secular, republics or monarchies. The Americans’ reasoning is simple: if the Middle East is left undisturbed even for a decade, a dangerous and virtually uncontrollable global player would emerge that could choose how to avail itself of its available energy resources, in addition to potentially withdrawing all of its assets from foreign banks and repositories, leading to unprecedented disruptions and crises for the West’s economy. To prevent this, regional interstate and intrastate conflicts are regularly triggered, and time bombs are systematically planted under the region. The initiators of these actions do not shy away from any method of inciting inter-ethnic, inter-national, or inter-religious crises, or direct military interventions. All in all, Americans are very well aware of what they are doing and why.

An analysis of reports in the Western press from recent weeks shows the prevalence of the idea of the futility of the political aspirations of Sunni Islam, as evidenced by the failed attempt of the Muslim Brotherhood to govern the state. There is a pervasive notion that Sunnis and Shiites will always exist in a state of eternal conflict, a viewpoint that could only have one realistic outcome – a period of growing tension culminating in a phase of mutual annihilation. From time to time, there seems to be an accidental eruption in the global media of the voices of those who feel that the Shiites are not only not Muslims, but the outright heretics, amoral sectarians and consummate fanatics who do not deserve to live.

A deliberate campaign is being waged to marginalize Islam, spreading assertions that Islam is not capable of developing its own positive agenda and that Islam always preaches violence, blood, vandalism, and the destruction of traditional society. This propaganda is being quite skillfully disseminated at both the level of academic research as well as through the mass media.

The current geopolitical reality is such that the decline of Western civilization forces its elite to seek ever-newer sources of “rejuvenation.” The United States is not as concerned with rescuing its allies amidst the unfolding global economic and civilizational crisis, as with ensuring its own survival and preserving its hegemony, even at Europe’s expense. Hence its desire to draw Europeans into the conflicts in the Middle East, while at the same time safeguarding its own homeland security.

Despite statements by officials in Washington, the actions of the US suggest that it is essentially contributing to the growth of Islamic radicalism, which it uses as a tried-and-true mechanism to undermine the position of any potential competitor. They are literally contriving to generate hotbeds of extremist, terrorist activities in Syria, Iraq, Libya, and many other countries, and the flames of all kinds of animosity are being kindled. They are calculating that the internal struggle will become extremely drawn out, exhausting the region and bleeding it dry, which will utterly debilitate any potential rivals or competitors.

It seems that Washington believes that the military and economic power of the US, as well as its geographical position,will enable it to keep itself above the fray, thus retaining its pivotal role in international politics.

But in fact, dreaming up all these schemes is not without its dangers, because, as the episode with the Tsarnaev brothers and the trial of Maj.Nidal Hasan has shown, such a policy, despite the careful calculations that would seem to be behind it, will eventually backfire onto the US itself. In addition, “challengers to the regime” can emerge within the system, and we are already witnessing the first seeds of that phenomenon in the actions of Pfc.Bradley Manning and the former NSA employee Edward Snowden.

Many Islamic medieval norms are not only in clear conflict with twenty-first-century realities, but give stir up tensions within society. And the problem here is not found in religion, but in the lack of a creative, constructive approach to understanding how the teachings of the Prophet should be viewed from a modern perspective.

The lack of any real progress in the creative development of the social teachings of Islam, and in some cases those processes have been deliberately handicapped – even amid the claim that it is being done for society’s benefit – is, in fact, clearing the path for new, radical groups. A vicious circle is formed. The situation is reaching the point in which Muslim youth look for guidance to the ideas expressed by the conservative ulamas, who claim that this conflict between a medieval system of values and the challenges of the modern age can only be eradicated by force, which includes violence and terror against intractable “unbelievers.”

These are the circumstances under which Russia is increasingly engaging with the Islamic world, discrediting the West’s projects (which are detrimental for all mankind) to manipulate countries and peoples, information and public opinion. Unlike the West, Russia is not only uninterested in splintering or reshaping the Islamic world, it demonstrates a consistent, firm commitment to upholding that region’s unity and integrity.

Russia is not interested in any type of bias – either toward West or the East. We want stability and prosperity – in both the West and the East, but not at the expense of the welfare of one over the other. We do not need a neighbor whose “house is on fire.”

In the current uneasy atmosphere, Russia calls upon the West to: “Stop trying to split the Islamic world,” while urging the Islamic world, in the name of the Qur’an and teachings of the Prophet Muhammad: “Do not be enemies of one other!”

Veniamin Popov – director of the Center for the Partnership of Civilizations at MGIMO (the school of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

Yuri Mikhailov – editor-in-chief at Ladomir,Academic Publishers

Source in Russian: REGNUM

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Géopolitique, Islam | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : géopolitique, islam, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

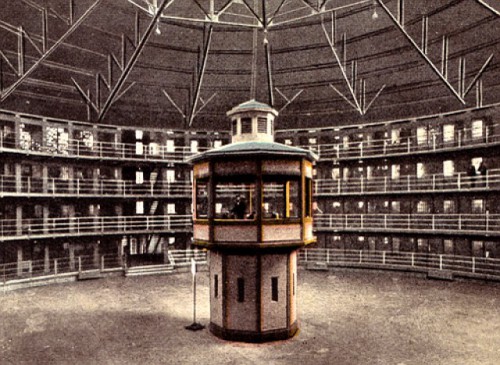

L'Affaire Snowden et le « Réseau Echelon »

Rémy VALAT

Ex: http://metamag.fr

00:05 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : politique internationale, panopticon, actualité, affaire snowden, eduard snowden, espionnage, prism, echelon, ukusa |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Corporativismo del III millenio

00:05 Publié dans Evénement | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : événement, corporatisme, italie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 09 octobre 2013

Café politique, Nantes

13:33 Publié dans Evénement | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : événement, nantes, bretagne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les noyés de Lampedusa : quand on culpabilise les Européens

Les noyés de Lampedusa : quand on culpabilise les Européens

Le 3 septembre, un navire de ”réfugiés” africains (Somaliens), en provenance de Libye (1) a fait naufrage au large de l’île italienne de Lampedusa qui est devenue une porte d’entrée admise des clandestins en Europe. 130 noyés, 200 disparus. Ils ont mis le feu à des couvertures pour qu’on vienne les aider et le navire a coulé à cause de l’incendie. Les garde-côtes italiens, ainsi que des pêcheurs, ont sauvé les survivants.

Immédiatement, le chœur des pleureuses a donné de la voix. Le maire de l’île, en larmes (réellement) a déclaré à l’agence de presse AFSA : « une horreur ! une horreur ! ». Le chef du gouvernement italien, M. Enrico Letta a parlé d’une « immense tragédie » et a carrément décrété un deuil national. Et, pour faire bonne mesure, le Pape François, qui était déjà allé accueillir des ”réfugiés” africains à Lampedusa, a déclaré : « je ne peux pas évoquer les nombreuses victimes de ce énième naufrage. La parole qui me vient en tête est la honte.[...] Demandons pardon pour tant d’indifférence. Il y a une anesthésie au cœur de l’Occident ». On croit rêver.

Sauf le respect dû au Saint-Père, il se trompe et il trompe. Et, en jésuite, pratique une inversion de la vérité. Car tout a été fait pour sauver ces Somaliens. Tout est fait pour les accueillir et ils ne seront jamais expulsés. Ils se répandront, comme tous leurs prédécesseurs, en Europe. (2) Comment interpréter cet épisode ?

Tout d’abord que le Pape François cherche à culpabiliser les Européens (la ”honte”, l’ ”anesthésie du cœur”, “indifférence”) d’une manière parfaitement injuste et par des propos mensongers. Cela semble tout à fait en accord avec la position suicidaire d’une partie des prélats qui sont objectivement partisans (souvenons-nous de l‘Abbé Pierre) d’une immigration invasive sans contrôle (l’accueil de l’Autre) sous prétexte de charité. Avec, en prime, l’islamisation galopante. On pourrait rétorquer à ces prélats catholiques hypocrites qu’ils ne font pas grand chose pour venir en aide aux chrétiens d’Orient (Égypte, Irak, Syrie…) persécutés, chassés ou tués par les musulmans. N’ont-ils pas ”honte“ ?

Deuxièmement, toutes ces manifestations humanitaristes déplacées des autorités européennes, tous ces larmoiements sont un signe de faiblesse, de démission. Ils constituent un puissant encouragement aux masses de migrants clandestins potentiels qui fuient leurs propres sociétés incapables pour venir en Europe, en parasites. Certains d’être recueillis, protégés et inexpulsables.

Troisièmement – et là, c’est plus gênant pour les belles âmes donneuses de leçons de morale – si l’Europe faisait savoir qu’elle ne tolérera plus ces boat people, le flux se tarirait immédiatement et les noyades cesseraient. Les responsables des noyades des boat people sont donc d’une part les autorités européennes laxistes et immigrationnistes et d’autre part les passeurs. Et, évidemment, les clandestins eux-mêmes que l’on déresponsabilise et victimise et qui n’avaient qu’à rester chez eux pour y vivre entre eux et améliorer leur sort (3).

Quatrièmement, et là gît le plus grave : les professeurs d’hyper morale qui favorisent au nom de l’humanisme l’immigration de peuplement incontrôlée favorisent objectivement la naissance d’une société éclatée de chaos et de violence. La bêtise de l’idéologie humanitaro-gauchiste et l’angélisme de la morale christianomorphe se mélangent comme le salpêtre et le souffre. Très Saint-Père, un peu de bon sens : relisez Aristote et Saint Thomas.

Notes:

(1) Avant le renversement de Khadafi par l’OTAN, et avant donc que la Libye ne devienne un territoire d’anarchie tribalo-islamique, il existait des accords pour stopper ces transits par mer.

(2) Depuis le début de 2013, 22.000 pseudo-réfugiés en provenance d’Afrique ont débarqué sur les côtes italiennes, soit trois fois plus qu’en 2012 . C’est le Camp des Saints…

(3) En terme de philosophie politique, je rejette l’individualisme. Un peuple est responsable de lui-même. Le fait de légitimer la fuite de ces masses d’individus hors de leur aire ethnique du fait de la ”pauvreté”, de la ”misère” ou de n’importe quoi d’autre, revient à reconnaître l’incapacité globale de ces populations à prendre en main leur sort et à vivre entre elles harmonieusement. C’est peut-être vrai, mais alors qu’elles n’exportent pas en Europe leurs insolubles problèmes.

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : guillauem faye, nouvelle droite, lampedusa, italie, europe, affaires européennes, immigration, politique internationale, frontex, méditerranée |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

The Western Challenge to Eurasian Integration

|

The Western Challenge to Eurasian Integration |

|