vendredi, 27 septembre 2013

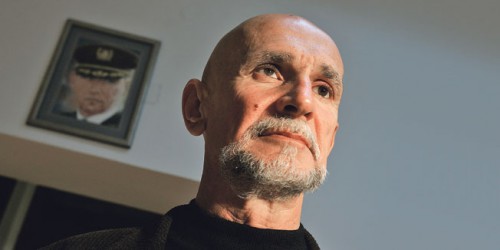

Entretien avec Lucien Cerise

Entretien avec Lucien Cerise auteur de "Oliganarchy"

Version revue et retouchée pour Égalité & Réconciliation du texte paru dans Rébellion, n°58 mars/avril 2013.

Version revue et retouchée pour Égalité & Réconciliation du texte paru dans Rébellion, n°58 mars/avril 2013.

Ex: http://www.scriptoblog.com

Pouvez-vous vous présenter en quelques lignes ?

Venant de l'extrême gauche de l'échiquier politique, je vote « Non » en 2005 au référendum sur le traité établissant une Constitution pour l'Europe, comme 55 % des votants. Quand je vois au cours des années 2006 et 2007 ce que le pouvoir fait du scrutin, cela me décide à m'engager dans les mouvements anti-Union européenne et antimondialistes, donc nationalistes, autonomistes et localistes. L'autogestion signifie pour moi « liberté des peuples à disposer d'eux-mêmes » ainsi que « souveraineté » dans tous les sens du terme : alimentaire, énergétique, économique, politique et cognitive. Au fil du temps et des rencontres, je me suis rendu compte que le clivage politique droite/gauche est en fait complètement bidon et que la seule différence à considérer est entre la vie et la mort.

En 2010, vous faisiez paraître Gouverner par le chaos – Ingénierie sociale et mondialisation chez Max Milo. Pouvez-vous revenir sur l'origine de votre réflexion et sur votre choix de l'anonymat ?

L'origine est multiple. D'abord, comme beaucoup de monde, j'ai observé chez nos dirigeants politiques, économiques et médiatiques une telle somme d'erreurs et une telle persistance dans l'erreur que j'ai été amené à me demander s'ils ne le faisaient pas exprès. En Occident, les résultats catastrophiques des orientations prises depuis des décennies sont évidents à court terme, si bien qu'on ne peut leur trouver aucune excuse. Une telle absence de bon sens est troublante. Cela induit un vif sentiment de malaise, qui peut devenir une dépression plus ou moins larvée, qui a été mon état pendant longtemps. J'en suis sorti progressivement, mais certains éléments ont été plus décisifs que d'autres pour me faire comprendre ce qui se passait vraiment et l'origine de ce malaise.

La lecture de La Stratégie du choc, de Naomi Klein, a été un choc, justement. On comprend enfin à quoi servent ce que l'on pourrait appeler les « erreurs volontaires » de nos dirigeants. Dans un premier temps, on attribue leurs erreurs à de la stupidité, ou à de la rapacité aveugle. En réalité, ces erreurs volontaires obéissent à une méthode générale tout à fait rationnelle et maîtrisée, développée sur le long terme et qui envisage positivement le rôle de la destruction. La Stratégie du choc aborde pour la première fois dans un livre pour le grand public cette doctrine de la destruction positive, qui constitue le cœur du capitalisme depuis le XVIIIe siècle et qui repose sur des crises provoquées et récupérées. Klein met cela en parallèle avec les méthodes de torture et de reconditionnement mental du type MK-Ultra, qui procèdent de la même inspiration : détruire ce que l'on ne contrôle pas, pour le reconstruire de manière plus « rationnelle » et assujettie.

En 2003, j'avais aussi fait des recherches sur le groupe de conseillers ultra-sionistes qui entourait Georges W. Bush et qu'on appelle les néoconservateurs. Je me suis plongé dans leurs publications, A Clean Break, le PNAC, ainsi que dans leur maître à penser, Leo Strauss, lequel m'a ramené sur Machiavel et sur Kojève, et sur une approche de la politique qui ne dédaigne pas le Fürherprinzip de Carl Schmitt, l'État-total cher à Hegel, ni de faire usage de « moyens extraordinaires », selon le bel euphémisme de l'auteur du Prince. De là, je suis allé voir du côté de la synarchie, avec Lacroix-Riz, puis j'ai élargi mon étude à tous ces clubs, groupes d'influence, sociétés secrètes et discrètes qui n'apparaissent que rarement dans les organigrammes officiels du pouvoir.

Par ailleurs, au cours de ces années, j'ai été en contact de deux manières différentes avec le monde du consulting, dans ses diverses branches : management, marketing, intelligence artificielle, mémétique, ingénierie sociale, cybernétique, etc. J'ai rencontré des gens qui étaient eux-mêmes consultants professionnels mais j'ai vu également l'autre côté de la barrière car j'ai subi sur mon lieu de travail des méthodes de management négatif, du même type que celles appliquées à France Telecom. Cela m'a poussé à devenir représentant syndical dans le cadre du Comité hygiène, sécurité et conditions de travail (CHSCT). Je m'étais spécialisé sur les questions de « souffrance au travail », de « burn-out », de « harcèlement moral » (cf. Hirigoyen, Dejours, Gaulejac).

À la même période, j'ai aussi commencé à m'intéresser très sérieusement à l'univers du renseignement, du lobbying, de l'influence et de la guerre cognitive, car j'envisageais de m'y réorienter pour y faire carrière (École de Guerre économique, DGSE, etc.). Pendant toute cette période, j'ai rencontré des gens et lu des publications qui m'ont beaucoup appris sur les méthodes de travail des manipulateurs professionnels, que ce soit en entreprise, en politique ou en tactique militaire, car on y rencontre les mêmes techniques et concepts : storytelling, management des perceptions, opérations psychologiques (psyops), attentats sous faux drapeau, etc.

Au début des années 2000, j'avais aussi exploré la piste du transhumanisme et du posthumanisme. J'y ai adhéré sincèrement, par déception de l'humain essentiellement, avant de comprendre que c'était une impasse évolutive. Ma formation universitaire, que j'ai débutée en philosophie et poursuivie en sciences humaines et sociales, en particulier dans la communication et la sémiotique, m'a donné les outils conceptuels pour synthétiser tout cela. Donc, pour revenir à la question « Nos dirigeants font-ils exprès de commettre autant d'erreurs ? », après vérification, je peux confirmer que oui, et que cela obéit même à une méthodologie extrêmement rigoureuse et disciplinée. Il existe une véritable science de la destruction méthodique, qui s'appuie sur un art du changement provoqué, et dont le terme générique est « ingénierie sociale ». (J'ai introduit par la suite une nuance entre deux formes d'ingénierie sociale, mais nous y reviendrons.)

Pourquoi l'anonymat ? Et j'ajoute une question : pourquoi suis-je en train de le lever plus ou moins ces temps-ci ? Pour tout dire, je me trouve pris dans une double contrainte. Je n'ai aucune envie d'exister médiatiquement ni de devenir célèbre. Une de mes maximes personnelles est « Pour vivre heureux, vivons cachés ». Je préfère être invisible que visible. En même temps, quand on souhaite diffuser des informations, on est contraint de s'exposer un minimum. Or, je veux vraiment diffuser les informations contenues dans Gouverner par le chaos (GPLC), ou dans d'autres publications qui ne sont pas forcément de moi. Je ne vois personne d'autre qui le fait, alors j'y vais. Je pense qu'il est indispensable de diffuser le plus largement possible les méthodes de travail du Pouvoir. J'ai un slogan pour cela : démocratiser la culture du renseignement.

Une autre raison à l'anonymat est de respecter le caractère collectif, ou collégial, de GPLC. Plusieurs personnes ont participé plus ou moins directement à son existence : inspiration, rédaction, médiatisation, etc. J'avoue en être le scribe principal, mais sans la contribution d'autres personnes, ce texte n'aurait pas existé dans sa forme définitive.

Que pensez-vous de la production du « Comité invisible » et de la revue Tiqqun ? L'affaire de Tarnac marque-t-elle une étape supplémentaire dans la manipulation des esprits et de la répression du système contre les dissidents de celui-ci ?

J'ai lu tout ce que j'ai pu trouver de cette mouvance situationniste extrêmement stimulante. Leurs textes proposent un mélange bizarre d'anarchisme de droite, vaguement dandy et réactionnaire, tendance Baudelaire et Debord, avec un romantisme d'extrême ou d'ultra gauche parfois idéaliste et naïf. Le tout sonne très rimbaldien. La vie de Rimbaud, comme celle d'un Nerval ou d'un Kerouac, combine des tendances contradictoires : la bougeotte du nomade cosmopolite avec la nostalgie d'un retour au réel et d'une terre concrète dans laquelle s'enraciner ; mais aussi une soif d'action immanente et révolutionnaire coexistant avec le mépris pour tout engagement dans le monde et la fuite dans un ailleurs fantasmé comme plus authentique. Une constante de ce « topos » littéraire, c'est que l'étranger est perçu comme supérieur au local. Ceci peut conduire à une sorte de masochisme identitaire, une haine ou une fatigue de soi qui pousse à rejeter tout ce que l'on est en tant que forme connue, majoritaire et institutionnelle, au bénéfice des minorités ou des marginaux, si possible venant d'ailleurs. Il y a une sorte de foi religieuse dans les « minorités », desquelles viendrait le Salut, croyance entretenue par de nombreux idéologues du Système, de Deleuze et Guattari à Toni Negri et Michael Hardt, en passant par la rhétorique des « chances pour la France ». Dans L'Insurrection qui vient, les lumpen-prolétaires animant les émeutes de banlieue en 2005 sont idéalisés de manière assez immature (et apparemment sans savoir que des agitateurs appartenant à des services spéciaux étrangers, notamment israéliens et algériens, s'étaient glissés parmi les casseurs).

Pour recentrer sur le corpus de textes en question, aujourd'hui je n'en retiens que le meilleur, le côté « anar de droite », c'est-à-dire une critique radicale et profonde du Capital, de la Consommation et du Spectacle mais qui reste irrécupérable par la gauche capitaliste, libertaire, bobo, caviar, sociétale, bien-pensante et « politiquement correcte ». De Tiqqun, je retiens donc surtout la « Théorie de la Jeune-Fille », texte absolument génial et très drôle. On y trouve des références à l'historien de la publicité Stuart Ewen, dont les recherches montrent comment le féminisme et le jeunisme furent dès les années 1920 les outils du capitalisme et de la société de consommation naissante aux USA.

En outre, je suis très travaillé par la question du rapport entre le visible et l'invisible. J'ai beaucoup « mangé » de phénoménologie pendant mes études de philo, comme tous les gens de ma génération : Husserl, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, Michel Henry, etc. Cette dialectique visible/invisible recoupe aussi le couple « voir et être vu » des théories de la surveillance, de Jeremy Bentham à Michel Foucault, et fait également écho au champ lexical du situationnisme. Et là on revient dans l'univers du Comité invisible.

Sur l'affaire de Tarnac proprement dite. Il se trouve que j'ai croisé certaines personnes de cette mouvance en diverses occasions, sans jamais faire partie directement de leur carnet d'adresses. J'évoluais à peu près dans les mêmes réseaux et la même nébuleuse dans les années 2000-2005, entre les squats, les revues, les collectifs et l'université de Paris 8 (Vincennes/Saint-Denis). Je me suis donc senti visé par l'affaire de Tarnac, dont le seul avantage a été de faire progresser la critique de la criminologie, en particulier dans sa forme actuarielle.

La science actuarielle consiste à calculer le potentiel de dangerosité et à prendre des mesures par anticipation. Sur ce sujet, il faut lire notamment Bernard Harcourt, dont voici l'extrait d'une interview sur le sujet :

« La dangerosité, écrivait il y a plus de 25 ans Robert Castel dans un livre prémonitoire intitulé La Gestion des risques ; la dangerosité, écrivait-il, est cette notion mystérieuse, qualité immanente à un sujet mais dont l'existence reste aléatoire puisque la preuve objective n'en est jamais donnée que dans l'après-coup de sa réalisation. Le diagnostic qui est établi est le résultat d'un calcul de probabilité ; la dangerosité ne résulte pas d'une évaluation clinique personnalisée, mais d'un calcul statistique qui transpose aux comportements humains les méthodes mises au point par l'assurance pour calculer les risques. D'où une nouvelle science (et retenez bien ce mot) : la science actuarielle. »

Globalement, la présomption d'innocence est inversée en présomption de culpabilité. Ce n'est plus au procureur d'apporter la preuve que vous êtes coupable, c'est à vous d'apporter la preuve que vous êtes innocent. Votre « dangerosité évaluée » et votre « potentiel criminel » suffisent à déclencher la machine judiciaire et à faire s'abattre sur vous le GIGN ou le RAID. La « menace terroriste », dont Julien Coupat et ses amis ont été accusés, s'inscrit complètement dans ce dispositif qui permet de criminaliser à peu près quiconque ne pense pas « correctement », tel qu'un Varg Vikernes, le Norvégien établi dans un village de Corrèze (lui aussi !) avec femme et enfants et suspecté de « nazisme ».

L'accusation purement médiatique autorise parfois le Pouvoir à tuer arbitrairement et sans procès, comme on l'a vu avec Mohamed Merah, qui n'a jamais été identifié légalement et formellement comme l'auteur des meurtres de Toulouse, mais qui a été pourtant bel et bien assassiné. Dans un état de droit, la culpabilité d'un accusé émerge au cours d'un procès équitable et contradictoire pendant lequel on apporte les preuves de la culpabilité si elles existent. Il semble que cela soit devenu superflu quant au traitement des prétendus « islamistes », que ce soit en France ou à Guantanamo. Pour tous ceux qui sont tués pendant leur arrestation, nous ne saurons donc jamais s'ils étaient coupables dans le monde réel, et pas seulement dans celui des médias !

Dans la série des montages politico-médiatiques visant à terroriser la population, passons rapidement sur l'affaire Clément Méric, dont l'objectif semblait être de faire exister une « menace fasciste » émanant d'une « droite radicale » pourtant très assagie. Et pour revenir à Tarnac, si le montage s'est effondré rapidement, c'est parce que les inculpés disposaient de soutiens dans l'intelligentsia parisienne ; sans cela, il y a fort à parier qu'ils seraient passés à la postérité comme des terroristes d'ultragauche avérés. Le cauchemar de science-fiction imaginé par Philip K. Dick et transposé au cinéma dans Minority report est devenu réalité. On pense aussi au chef d'œuvre absolu de Terry Gilliam, Brazil.

Pour vous, le contrôle des masses a profondément changé avec l'apparition de l'ingénierie sociale. Que recouvre ce terme selon vous ?

Il y a plusieurs définitions de l'ingénierie sociale. On peut les trouver en tapant sur Google. Certaines universités proposent un diplôme d'État d'ingénierie sociale (DEIS) et donnent quelques descriptions sur leurs sites. Il existe aussi de nombreuses publications, des articles sur la sécurité informatique, de la littérature grise, des manuels de sociologie et de management, des rubriques d'encyclopédies, etc.

Je propose la synthèse suivante de toutes ces définitions : l'ingénierie sociale est la modification planifiée du comportement humain.

Il est difficile de fixer une date précise à l'apparition du terme. En revanche, l'intuition qui est derrière, en gros la mécanisation de l'existence, remonte probablement à l'apparition des premières villes en Mésopotamie et dans l'Égypte pharaonique, vers 3000 avant J.-C. Je pense aux premiers centres urbains rassemblant plusieurs milliers de personnes dans une structure différenciée et néanmoins relativement unifiée sous un seul nom qui en définit les contours.

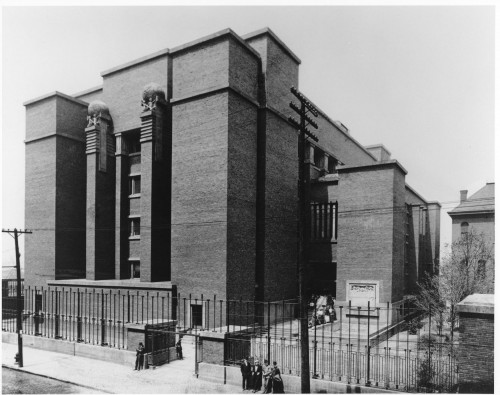

L'échelle du village et de l'artisanat n'est pas suffisante pour percevoir l'existence comme un mécanisme. Le passage des sédentaires ruraux aux sédentaires urbains a fait émerger la première représentation des groupes humains comme étant des objets automates, ou du moins automatisables dans une certaine mesure. En adoptant le point de vue surplombant qui était celui des premiers oligarques du Proche-Orient, une ville ressemble assez à une grosse machine : une horloge, ou un ordinateur, au risque de l'anachronisme. Quand les intellectuels de l'époque, c'est-à-dire les prêtres, ont eu sous leurs yeux les premières villes, donc les premiers mécanismes d'organisations humaines complexes, l'idée du contrôle et de la prévisibilité de ces mécanismes a nécessairement germé en eux. Quelques siècles plus tard, Platon invente le terme de cybernétique, ou l'art du pilotage. L'alchimie et la franc-maçonnerie sont les héritières spirituelles de ces premières observations, avec leurs métaphores physicalistes et architecturales récurrentes.

Le fil conducteur de cette tradition rationaliste en politique est la réduction de l'incertitude, qui est l'objectif poursuivi par tout gestionnaire de système. Quand il s'agit d'un système vivant, cet objectif peut avoir des effets sclérosants et meurtriers. Je ne suis pas loin de partager le point de vue radical de Francis Cousin, à savoir que nos problèmes ont commencé au néolithique !

Cependant, inutile de remonter aux chasseurs-cueilleurs pour retrouver le « paradis perdu ». L'échelle rurale et villageoise, voire la petite agglomération urbaine, me paraissent suffisants pour une relocalisation autogestionnaire satisfaisante qui permette d'éviter certaines pathologies du contrôle à distance. La nouveauté au XXe siècle vient de ce que l'on passe d'un contrôle social par l'ordre à un contrôle social par le désordre. L'ordre par le chaos.

Je fais remonter le projet concret de la gouvernance par le chaos à l'invention du « capitalisme révolutionnaire » entre 1750 et 1800, c'est-à-dire un capitalisme provoquant des révolutions pour faire avancer son agenda. Mais il a fallu attendre les années 1960 pour fabriquer le consentement total des masses au capitalisme en l'introduisant dans les mœurs sous les termes de « libertarisme » ou d'« émancipation des minorités ».

En France, l'événement fondateur de cet arraisonnement complet des masses par le Capital et sa gouvernance par le chaos fut Mai 68. Il faut voir le documentaire Das Netz, de Lutz Dammbeck, qui fait la jonction entre les projets de contrôle social issus de la cybernétique dans les années 1950 et l'émergence dix ans plus tard de la contre-culture pop anglo-saxonne, comme par hasard. Les preuves existent que la contre-culture était un outil du Capital pour produire de l'entropie sociale. On pense au financement de Pollock par la CIA, ou encore à ce que rapporte Mathias Cardet dans L'Effroyable Imposture du rap. À partir des années 1960, donc, une idéologie dominante fondée sur des principes d'anarchie, d'individualisme, d'anomie, d'hédonisme et de « jouissance sans entrave » s'est diffusée dans toute la sphère culturelle occidentale, préparant le tsunami de pathologies mentales et sociales qui nous submerge depuis les années 1980 : dépressions, vagues de suicides, violences conjugales, épidémie d'avortements de confort, enfant-roi hyperactif, délinquance juvénile, toxicomanies, criminalité sociopathe, obésité, cancers, pétages de plombs divers qui finissent en bain de sang, etc.

Cette idéologie dominante individualiste et an-archique, voire acéphale, commune à la gauche libertaire et à la droite libérale, n'a qu'un but : faire monter l'entropie, c'est-à-dire le désordre et le déséquilibre dans les groupes humains, pour les disloquer, les atomiser et améliorer l'asservissement des masses en rendant leur auto-organisation impossible. Diviser pour régner. Pousser les masses à « jouer perso », les éduquer au « chacun pour soi », pour enrayer la force des collectifs. Donc dépolitiser. En effet, le geste fondateur du phénomène politique consiste à soumettre la liberté individuelle à l'intérêt collectif. En inversant les priorités par le sacrifice de l'intérêt collectif sur l'autel de la sacro-sainte liberté individuelle, l'ingénierie sociale du Capital paralyse et sape ainsi toute capacité organisationnelle concrète. Comme on le voit, le capitalisme contrôle les masses par le désordre. Le véritable anticapitalisme, c'est donc l'ordre. La rébellion, la dissidence, la résistance, la subversion, c'est l'ordre.

La psychanalyse semble avoir un rôle ambivalent dans ce phénomène. Quelle est votre opinion sur cette école (sur Freud, Jung ou Lacan) ?

La psychanalyse passe son temps à rétablir du surmoi, c'est-à-dire de l'ordre, de l'autorité morale, des limites comportementales et de la stabilité mentale. Elle est donc l'ennemie du capitalisme. Mais elle est perçue aussi comme une ennemie par les religions, car elle leur fait concurrence dans une certaine mesure. Donc, tout le monde la déteste et la passe en procès.

Le problème, c'est que ce mauvais procès fait à la psychanalyse n'est pas toujours très cohérent. On dit simultanément : « La psychanalyse ne marche pas » et « La psychanalyse détruit les êtres qui s'y adonnent ». Il faudrait choisir. Les deux accusations sont mutuellement incompatibles sur le plan strictement logique. Si elle ne marchait pas, elle n'aurait aucun effet, même pas destructeur. Ce serait un facteur nul, un zéro, ni « plus », ni « moins ». En fait, la psychanalyse marche, raison pour laquelle elle peut effectivement détruire les gens qui sont sous son influence. Ses applications excèdent le cadre de la thérapie et se retrouvent aussi beaucoup en management, en marketing et, ce que l'on sait moins, en sécurité informatique, dans sa branche ingénierie sociale, justement.

Le fait que Freud ait été chez les B'nai B'rith est une raison supplémentaire pour s'informer sur les méthodes de manipulation et de déconstruction psychologique qui nous sont appliquées. C.-G. Jung est indispensable à connaître également, mais Jacques Lacan est encore plus précis et nous propose une vraie boîte à outils permettant d'agir directement sur soi ou sur autrui. Pour user de métaphores biologiques ou informatiques, la psychanalyse lacanienne, et le structuralisme en général, donnent accès au « code génétique », ou au « code source » de l'esprit et de la société.

Par exemple, un mathème lacanien, le schéma R (pour Réalité), modélise le mécanisme de la construction de confiance, qui est exactement le même que le mécanisme de la construction de la réalité : on peut donc appliquer ce schéma pour abuser de la confiance d'autrui en lui créant une réalité virtuelle, ou à l'inverse pour empêcher la construction de confiance, en soi ou en autrui, et ainsi empêcher la construction d'une réalité viable et habitable. Si vous observez les choses de près, vous trouverez l'équation « confiance = réalité ». Quand la confiance disparaît, c'est la réalité qui s'effondre. En revanche, si vous me faites confiance, je commence à construire votre réalité.

On voit le danger : si la psychanalyse dévoile et met à nu les règles de base de la construction de la réalité, du psychisme et de la vie en société, elle peut être utilisée également pour déconstruire la réalité, le psychisme et rendre impossible la vie en société. Comment ? En jouant sur l'Œdipe, c'est-à-dire le sens dialectique. Je détaille.

Une société possède nécessairement des différences. Une société parfaitement homogène n'existe pas. Or, la gestion des différences, leur articulation fonctionnelle et organique, ne se fait pas toute seule. L'articulation des différences porte un nom : la dialectique. La dialectique, cela s'apprend. Les différences premières, fondatrices de toute société, se résument par un concept : le complexe d'Œdipe. Ce sont les différences hommes/femmes et parents/enfants (par extension jeunes/vieux). Ces différences sont néanmoins articulées et fonctionnent ensemble, de manière organique, au sein de la famille. Le schéma familial offre ainsi le modèle originel du fonctionnement de tout groupe social : des différences respectées, on ne fusionne pas, mais fonctionnant ensemble.

Si on n'intériorise pas ce premier système de différences articulées, on ne peut pas en intérioriser d'autres et on développe des problèmes d'identité et d'adaptation sociale. En effet, l'identité est à l'image du système social : dialectique. Je ne sais qui je suis que par opposition et différenciation. L'identité, la construction identitaire, repose donc sur la position d'une différence première, originelle, fondatrice. Pour que je puisse agir dans le monde et me socialiser normalement, je dois donc sortir du flou identitaire pré-œdipien, le flou fusionnel qui précède la perception des différences.

Dans sa vidéo de janvier 2013, Alain Soral et son équipe rapportent un document stupéfiant. À l'occasion d'une audition sur le projet de « mariage pour tous », l'anthropologue Maurice Godelier préconisait de remplacer les termes « père » et « mère » par le terme générique de « parents ». D'après lui, le mot « parent », qui peut désigner simultanément le père, la mère, comme le grand-père et la grand-mère, présente ce double avantage d'effacer la différence des sexes et d'effacer la différence des générations. Quiconque possède quelques éléments d'anthropologie ou de psychanalyse repère immédiatement où Godelier veut en venir : produire intentionnellement du flou identitaire, donc de la psychose, en effaçant le complexe d'Œdipe, les différences hommes/femmes et parents/enfants, donc les différences au sein de la famille, et par extension au sein de la société.

En fait, les différences persistent dans le réel, mais elles ne sont plus perçues, ni intériorisées. Si les différences ne sont plus perçues, les identités non plus. Cette incapacité à percevoir, intérioriser et gérer les différences et les identités porte un nom : la psychose, le flou identitaire. « Je ne sais pas qui je suis parce que je ne sais pas ce qui est en face de moi. » Godelier et les partisans de la théorie du genre, qu'il faudrait renommer « théorie de la confusion des genres », cherchent à produire du flou identitaire chez les enfants, et pourquoi pas chez les adultes. Ils cherchent donc à produire des handicapés mentaux, incapables de se socialiser. Ils cherchent à créer des problèmes d'identité et à générer des pathologies mentales et sociales, qui finiront en suicides, en meurtres ou en toxicomanies de compensation.

L'effacement des différences fondatrices, c'est l'effacement des limites, de toutes les limites. L'objectif, c'est la plasticité identitaire infinie, qu'on renommera « liberté identitaire infinie » pour mieux hameçonner la proie avec une accroche désirable, au prix de l'émergence de nouvelles souffrances. Toujours dans sa vidéo de janvier 2013, Soral remarquait fort justement que « la liberté, c'est la folie ». C'est bien de cette folie que Deleuze et Guattari se sont faits les chantres à partir de L'Anti-Œdipe, cette bible de l'antipsychiatrie dont le sous-titre est « Capitalisme et schizophrénie ». Publié en 1972, ce texte a profondément marqué la pensée libertaire. Il y est fait une apologie de la schizophrénie comme étant le parachèvement du capitalisme en tant que libération de toutes les structures et affranchissement de toutes les limites psychiques, comportementales et identitaires. L'alliance objective entre libertarisme et libéralisme est donc conclue officiellement et revendiquée depuis une bonne quarantaine d'années.

Une liberté sans limite rend fou et empêche donc la socialisation. À l'opposé, la psychanalyse tourne entièrement autour de cet adage : « Ma liberté s'arrête où commence celle des autres. » La limite, le surmoi dans le jargon freudien, a un effet positif et négatif en même temps. La limite réprime l'expression libre du désir. Apprendre à vivre en société, c'est apprendre qu'on ne fait pas ce qu'on veut et qu'il y a des limites à respecter. Il y a des bornes à l'expression de mon désir, il y a des règles, des lois, des structures, des cadres, des interdits à respecter et sans lesquels la société ne peut pas fonctionner. Cette répression de la liberté du désir permet donc de vivre en société, mais induit également une frustration. Cette frustration peut s'accumuler, s'enkyster, et devenir une névrose. C'était la pathologie la plus courante jusque dans les années 1970. L'ordre social exercé par une autorité morale et l'intériorisation d'une limite (un Père ou un phallus symbolique) était simultanément répressif et socialisant, frustrant et structurant, névrotique et normatif. C'était le mode de socialisation normal dans l'espèce humaine, avec des avantages et des inconvénients. C'est la gouvernance par l'ordre, par l'imposition de limites rigides à ne jamais dépasser, sous peine de punition.

Cet ordre ancien, celui de notre espèce et de ses constantes anthropologiques depuis ses origines, est aujourd'hui attaqué. L'Occident postmoderne a vu naître un « ordre nouveau », un mode de gouvernance par le chaos qui est une forme de contrôle social entièrement neuve consistant à lever toutes les limites et à laisser le désir s'exprimer librement. Dans un premier temps, on a l'impression de respirer enfin, on s'amuse, sans le surmoi phallique et surplombant. Le problème, quand on tue le Père, c'est qu'on est récupéré par la Mère, qui est en réalité tout aussi despotique que le Père. En Mai 68, Lacan disait à ses étudiants libertaires : « Vous aussi, vous cherchez un maître. » En l'occurrence, une Maîtresse, car la libre expression du désir, sans plus aucune limite ni structure, est le mode d'être hystérique, puis pervers, puis psychotique. Sans répression du désir, pas de sublimation, pas de symbolisation, pas de structuration psychique et comportementale possible, pas d'accès au langage et à la dialectique articulée.

Il existe donc une véritable ingénierie psychosociale de la levée des limites, de la transgression des interdits, des lois, des tabous et de l'abolition des frontières, donc une ingénierie de la désocialisation, de l'ensauvagement, de la déstructuration des masses et de la régression civilisationnelle provoquée, en un mot une ingénierie de la dés-œdipianisation, mise en œuvre par des gens qui savent exactement ce qu'ils font, grâce ou à cause de Freud et Lacan (Jung n'ayant pas reconnu le caractère fondateur de l'Œdipe et de la limite), qu'il s'agisse de psychanalystes à proprement parler ou d'auteurs imprégnés de psychanalyse. La théorie de la confusion des genres n'est qu'un outil de cette offensive du Capital pour transformer l'humain en une matière plastique modelable à l'infini, fluidifier toutes les structures comme le recommande l'Institut Tavistock, afin de parvenir à la « société liquide » décrite par Zygmunt Bauman.

Le résultat de cette déshumanisation, ou dés-hominisation, c'est ce que d'autres psys dénoncent, dont Julia Kristeva, dès les années 1980 dans Les Nouvelles Maladies de l'âme, ou l'Association lacanienne internationale (ALI), notamment Charles Melman et Jean-Pierre Lebrun dans L'Homme sans gravité : l'explosion de ces pathologies très contemporaines, dépression, perversion, toxicomanie, hystérie banalisée, « psychoses froides », « états limites », « borderline », sociopathie, psychopathie. On lira aussi Dominique Barbier, Dany-Robert Dufour ou Jean-Claude Michéa.

Vous évoquiez dans un de vos récents textes « l'industrie du changement ». Qui sont pour vous ces « faiseurs » des bouleversements que nous subissons ? Que recherchent-ils ?

À l'occasion d'un séminaire auquel j'ai assisté, un consultant spécialisé en conduite du changement nous avait dit que son entreprise travaillait à « industrialiser la compétence relationnelle ». Les changements provoqués au moyen de crises dirigées ne servent donc pas à améliorer le fonctionnement des choses, mais à l'industrialiser, c'est-à-dire à le rationaliser, le standardiser, l'automatiser. Cela consiste à changer d'échelle de production et de contrôle. Quand on passe de l'artisanat à l'industrie, on passe aussi d'une production locale à une production globale. La production locale est décentralisée, enracinée, contextualisée, démocratique, quand la production globale est centralisée, déracinée, décontextualisée, oligarchique. L'industrie du changement consiste à transférer tout le contrôle de la production de l'échelle locale à l'échelle globale. La gouvernance par le chaos consiste à détruire le pilotage local et autonome de l'existence pour le remplacer par un pilotage global et hétéronome, toujours à distance.

En géopolitique, la transitologie est la discipline qui traite du « regime change », les changements de régime que l'Empire américano-israélien cherche à produire dans les pays arabo-musulmans, et un peu partout en fait, pour s'approprier le pilotage à distance de ces pays. En dernière instance, le but recherché est la modification de la structure générale des relations humaines : passer d'un lien social normal, fondé sur l'altruisme, l'empathie et la mutualité, à un lien social sociopathe, retravaillé par le capitalisme et le libertarisme, fondé sur la liberté individuelle. C'est ça, l'industrialisation de la compétence relationnelle. Concrètement, cela donne le « mariage homo », la GPA, soit la location du ventre des femmes, la PMA, soit le commerce des enfants, et pour finir l'euthanasie pour tous.

En fait, le « comment ? », la méthode appliquée, m'intéresse plus que le « qui ? », l'identité. En outre, la réponse au « comment ? » donne la réponse au « qui ? » Donc, qui sont les faiseurs des bouleversements pathogènes que nous subissons ? Réponse : tous ceux qui appliquent la méthode générale de bouleversement contrôlé. En gros, ce sont tous les acteurs du capitalisme et des révolutions de rupture, dont 1789 et 1917 sont les prototypes, et dont les « révolutions colorées », de Mai 68 au « printemps arabe », sont les prolongements, jusqu'en Libye et en Syrie aujourd'hui. Ces acteurs du capitalisme sont secondés par ce que l'on dénommait jadis les conseillers en propagande du Prince, et qu'on appelle aujourd'hui des spin doctors, des consultants, des influenceurs, des communicants, bref tous ceux qui travaillent à faire du storytelling et de la désinformation dans des entreprises, des think tanks, des lobbies, des médias, des services de renseignement, des sociétés de pensée plus ou moins ésotériques.

Cette stratégie du choc amène la notion de chaos que vous utilisez pour définir la logique du système. Pouvez-vous revenir sur la généalogie de cette soif de destruction de l'oligarchie mondiale ?

La pulsion de mort est largement partagée dans l'espèce humaine. Il semble néanmoins que certains groupes sociologiques l'actualisent davantage que d'autres. En termes de topologie structurale lacanienne, la destruction est une place à occuper, et en termes de psychologie archétypale jungienne, le Destructeur est un rôle à endosser. La question qui me vient tout de suite est : qui occupe cette place dans mon environnement immédiat, que je puisse m'en protéger ?

Si l'on fait une généalogie de la destruction en Occident, on arrive à un résultat qui n'est pas « politiquement correct ». Une histoire des idées impartiale montre que, sous nos latitudes monothéistes, le premier exposé d'un programme politique fondé sur la destruction est déposé dans le texte que les juifs appellent la Torah, et les chrétiens le Pentateuque. Pour certaines personnes, détruire est donc un commandement divin, consigné noir sur blanc dans des textes sacrés. Un échantillon :

Deutéronome : chapitre 20, versets 10 à 16.

« Quand tu t'approcheras d'une ville pour l'attaquer, tu lui offriras la paix. Si elle accepte la paix et t'ouvre ses portes, tout le peuple qui s'y trouvera te sera tributaire et asservi. Si elle n'accepte pas la paix avec toi et qu'elle veuille te faire la guerre, alors tu l'assiégeras. Et après que l'Éternel, ton Dieu, l'aura livrée entre tes mains, tu en feras passer tous les mâles au fil de l'épée. Mais tu prendras pour toi les femmes, les enfants, le bétail, tout ce qui sera dans la ville, tout son butin, et tu mangeras les dépouilles de tes ennemis que l'Éternel, ton Dieu, t'aura livrés. C'est ainsi que tu agiras à l'égard de toutes les villes qui sont très éloignées de toi, et qui ne font point partie des villes de ces nations-ci. Mais dans les villes de ces peuples dont l'Éternel, ton Dieu, te donne le pays pour héritage, tu ne laisseras la vie à rien de ce qui respire. »

Cela dit, personne ne détient le monopole de la pulsion de mort. Le Japon ou la Corée du Sud connaissent des processus d'auto-génocide liés au « tout technologique ». Certaines régions d'Orient et d'Asie sont à la pointe de tous les délires post-humains et cybernétiques ; on y parle sérieusement de clonage reproductif ou de remplacement du peuple par des robots, ce genre de choses.

Je pense que la soif de destruction et d'autodestruction remonte en fait à un profil psychologique qui porte au moins trois noms : sociopathe, psychopathe, pervers narcissique. Le psychiatre polonais Lobaczewski est l'un des premiers à l'avoir étudié et il en a tiré une science, la ponérologie, ou la science du Mal. Je suis extrêmement convaincu par ce modèle ; pour ma part, je situe l'origine du Mal sur Terre dans ce profil psychologique sociopathe. Sa caractéristique est l'absence d'empathie, ce qui le conduit à traiter autrui comme un objet, un moyen, et à le chosifier. On peut rencontrer ce profil psychologique dans toutes les cultures, mais il semble néanmoins que certaines conjonctures favorisent son apparition. Notamment, les environnements socioculturels marqués par les thèmes de la destruction et du génocide sont, par excellence, des fabriques de sociopathes.

Lucien Cerise

Retrouvez le dernier roman de Lucien, Oliganarchy sur notre boutique.

00:05 Publié dans Entretiens | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : lucien cerise, entretien, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Drones. L'absence de l'industrie européenne

Drones. L'absence de l'industrie européenne

par Jean-Paul Baquiast

Ex: http://www.europesolidaire.eu

De premiers types de drones ont été depuis la guerre du Vietnam voire auparavant, utilisés par l'US Air Force. Mais il s'agissait d'engins encore primitifs, très liés à un pilotage terrestre de proximité. Les Israéliens, toujours soucieux de moderniser leur défense et conquérir de nouveaux marchés, ont depuis au moins 10 ans compris l'opportunité non seulement stratégique mais industrielle que représente la mise au point et l'exportation de nouvelles générations d'appareils. Les Etats-Unis, avec toute la force de leurs lobbies militaires et industriels, n'ont pas tardé à suivre. Aujourd'hui, ils fabriquent et utilisent des milliers de drones, dont les capacités, non seulement aéronautiques ou concernant l'armement, mais en terme d'intelligence artificielle et de capteurs embarqués, sont constamment améliorées.

Obama en avait fait ces dernières années un élément essentiel des guerres menées au Moyen-Orient, y compris dans le cadre d'opérations « furtives » menées à l'encontre de groupes dits terroristes dans des pays supposés amis comme le Pakistan. De telles opérations suscitent aujourd'hui de plus en plus de protestations de la part de ces pays. Mais elles ne cesseront pas pour autant. Elles pourront être étendues, au moins sous la forme de la surveillance, aux deux grandes zones ou l'Amérique entend maintenir son influence, l'Amérique centrale et la mer de Chine. Peut-être verra-t-on de tels drones opérer également aux frontières orientales de l'Europe, voire en Europe même, à partir de bases de l'Otan, avec l'accord implicite des Etats européens concernés.

Dans le cadre de la compétition mondiale qui met désormais en présence l'Amérique et la Chine, le gouvernement de ce dernier pays a entrepris depuis quelques années de se doter en matière de drones d'une industrie indépendante des technologies occidentales. Il s'agit non seulement de répondre à ses besoins propres en termes militaires, de police ou d'environnement, mais d'alimenter un courant d'exportation pour lequel la Chine disposera de ses avantages habituels, notamment en termes de coûts. Les grands fabricants chinois en matériels aéronautiques et militaires disposent désormais de centres de recherche dédiés aux drones. Ils exposent leurs prototypes dans les manifestations internationales, comme le Salon du Bourget en France.

Ceci n'a pas manqué d'inquiéter les experts de défense aux Etats-Unis. Un rapport pour 2012 du Defense Science Board, utilisé comme conseil par le Pentagone, prévoit déjà la perte du monopole américain dans le domaine des UAV . Le document est déclassifié et est accessible sur le web (http://www.acq.osd.mil/dsb/reports/AutonomyReport.pdf). La Chine n'a pas fourni de statistiques concernant ses moyens, mais Taiwan estime que l'aviation chinoise dispose déjà de 280 unités, des milliers d'autres étant réparties ailleurs. La flotte chinoise serait donc la seconde au monde, après l'américaine, qui compterait actuellement environ 7000 drones. Dans l'immédiat, il apparaît que la Chine utilisera ses drones dans des zones où elle cherche à imposer se présence militaire: Tibet, Xinjiang, frontières avec le Japon, par exemple. A terme, le rapport fait valoir que les Chinois pourraient en cas de conflit détruire avec succès un porte-avion américain en utilisant des flottilles de drones, bien plus difficiles à contrôler que des flottilles de vedettes.

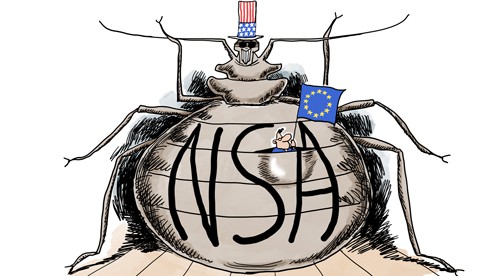

Le contre-espionnage américain attire aujourd'hui l'attention sur la cyber-guerre que mènerait actuellement la Chine pour détourner les principales données industrielles et de recherche mises au point par les entreprises américaines travaillant pour la défense. Une offensive générale contre des hackers travaillant pour le compte de la Chine se déroule actuellement aux Etats-Unis. Selon la firme américaine FireArm (http://www.fireeye.com/) qui opère dans le cadre de la cyber-défense, une opération massive serait conduite par un groupe de hackers nommé Comment Crew basé à Shanghai. Ceci n'aurait rien d'étonnant, puisque c'est de cette façon que beaucoup d'industriels asiatiques ont pris connaissance des savoir-faires américains et européens. La NSA américaine n'est pas en reste, puisque l'on sait maintenant qu'elle espionne systématiquement toutes les entreprises européennes, civiles ou de défense.

En matière de drones malheureusement, il n'y aurait pas grand chose à espionner en Europe, y compris chez les grands industriels de l'aéronautique et du spatial. Nous avons indiqué en introduction que ni l'Union européenne ni les gouvernements de l'Union n'ont actuellement proposé de politiques industrielles et de recherche sérieuses dans le domaine des drones. Une recherche attentive montrerait cependant que certains programmes sont à l'étude. Mais manifestement leurs ambitions tant militaires que civiles sont timides et lointaines. Les Européens, et la France en premier lieu, se privent ainsi d'un important atout pour le « redressement industriel ». Il faudrait rechercher les responsables de cette démission, qui a certainement profité à certains intérêts (allemands?). Nous ne le ferons pas ici, car une enquête sérieuse s'imposerait, dépassant le cadre de cet article. Bornons nous à signaler cette inadmissible absence des entreprises et du gouvernement français dans un secteur essentiel.

00:05 Publié dans Affaires européennes, Défense | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : drones, défense, europe, affaires européennes, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

L’eredità romano-bizantina della Russia nel pensiero di Arnold Toynbee

L’eredità romano-bizantina della Russia nel pensiero di Arnold Toynbee

Preambolo

Preambolo

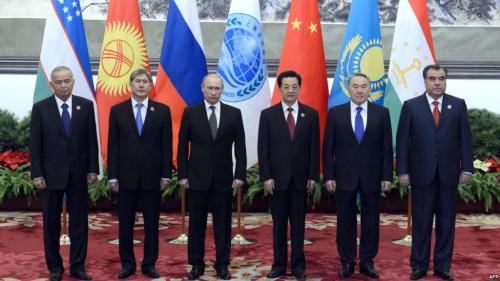

La recentissima iniziativa diplomatica di Vladimir Putin in relazione alla crisi siriana ha riproposto e rilanciato il ruolo internazionale della Russia, dopo un ventennio di declino seguìto allo smembramento ed al collasso dell’Unione Sovietica nel 1991.

In precedenza, con varie scelte di politica interna (l’azione penale contro le Femen, la lotta contro l’oligarchia affaristico-finanziaria, la polemica e l’opposizione al modello occidentale delle adozioni da parte dei gay), Putin si era posto come esponente di un modello alternativo rispetto a quello del “politicamente corretto” di matrice statunitense, differenziandosi anche da altri esponenti della classe dirigente russa che esprimono un atteggiamento più filo-occidentale.

Nella attuale crisi siriana, la Russia esprime ed afferma una visione geopolitica multipolare che si è concretizzata nell’esito del G-20 di S. Pietroburgo, in cui la sua opposizione all’intervento militare USA in Siria ha coagulato intorno a sé i paesi del BRICS (Brasile, India, Cina, Sudafrica, oltre alla Russia stessa). Il presidente russo ha però compreso che non era sufficiente limitarsi a dire no alla guerra nel teatro siriano, ma occorreva mettere in campo un’iniziativa diplomatica che sottraesse ad Obama il pretesto delle armi chimiche per un intervento bellico ammantato da giustificazioni “umanitarie” e legato, in realtà, ad un preciso disegno geopolitico di smembramento e destabilizzazione delle guide politiche “forti” del mondo arabo e dell’area mediorientale in particolare, in moda da garantirsi il controllo delle fonti energetiche (compreso il grande bacino di gas presente nel sottosuolo del Mediterraneo orientale) e consolidare la supremazia militare e politica di Israele.

Questo rilancio del ruolo internazionale della Russia sia rispetto agli USA, sia rispetto al dialogo euro-mediterraneo, unitamente alla riaffermazione di una diversità culturale russa rispetto ad un occidente americanizzato, sollecita una riflessione sulle radici storico-culturali della Russia e sulla possibilità di riscoprire una koiné culturale euro-russa che investe le origini storiche di questa Nazione e la sua diversità rispetto al modello di un Occidente che graviti sul modello americano.

La diffusione e il rilancio della teoria politica “euroasiatica” (espressa in Italia dalla rivista Eurasia e che vanta illustri precedenti teorici) e la recentissima enucleazione del progetto “Eu-Rus” rendono tale riflessione ancora più attuale e necessaria.

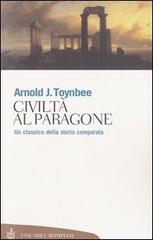

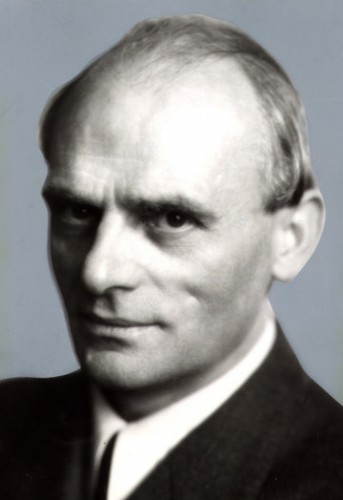

A tale riguardo è molto pertinente considerare un saggio dello storico inglese Arnold Toynbee (Londra 1889-York 1975), dal titolo Civilisation on trial (Oxford, 1948), pubblicato poi in traduzione italiana per le edizioni Bompiani nel 1949 e poi riedito tre volte, fino all’ultima edizione del 2003. Il saggio appare quindi in piena epoca staliniana, quando l’URSS sembrava l’antagonista dell’Occidente nello scenario della “guerra fredda”.

In questo libro – che è un classico della storia comparata e che pur risente fortemente del momento storico in cui viene scritto (il passaggio all’era atomica, la supremazia militare ed economica americana), lo storico inglese si interroga sulle radici remote e sull’ eredità bizantina della Russia, illuminandone una dimensione profonda che, nel contesto storico in cui venne teorizzata, denota la capacità di trascendere le apparenze e identificare le “costanti” della storia.

Toynbee divise la sua attività fra gli incarichi accademici e quelli politico-istituzionali. Fu docente di storia bizantina all’Università di Londra (e questo è un aspetto importante per capire il saggio di cui ci occupiamo) e docente di storia internazionale alla London School of Economics. Egli fece parte di numerose delegazioni inglesi all’estero e fu direttore del Royal Insitute of International Affairs. La sua opera maggiore è A Study of History (Londra-Oxford, 1934-1961) in 12 volumi, ma ricordiamo anche L’eredità di Annibale, pubblicato in Italia da Einaudi, in cui approfondisce le linee guida della politica estera di Roma antica e le conseguenze devastanti della guerra annibalica; siamo in presenza di uno storico famoso la cui opera spazia da Bisanzio a Roma antica, da Annibale alle civiltà orientali, offrendo al lettore un grande scenario d’insieme. Egli unisce lo studio della storia all’esperienza diplomatica ed alla conoscenza della realtà contemporanea.

L’eredità bizantina della Russia

In Civiltà al paragone Toynbee dedica un‘ intero capitolo al tema dell’eredità bizantina della Russia e lo apre con la citazione di una massima di Orazio: “Naturam espellas furca, tamen usque recurret” (“Allontana pure la natura; tuttavia essa ritornerà”).

In Civiltà al paragone Toynbee dedica un‘ intero capitolo al tema dell’eredità bizantina della Russia e lo apre con la citazione di una massima di Orazio: “Naturam espellas furca, tamen usque recurret” (“Allontana pure la natura; tuttavia essa ritornerà”).

“Quando tentiamo di rinnegare il passato - scrive lo storico inglese - quest’ultimo ha, come Orazio ben sapeva, un suo modo sornione di tornare fra noi, sottilmente travestito”. Egli non crede quindi alle affermazioni del regime di Stalin secondo cui la Russia avrebbe compiuto un taglio netto col suo passato. In realtà, le radici di un popolo possono manifestarsi in forme nuove, adattate al mutato contesto storico, ma è falso ed illusorio pretendere di cancellare il passato.

Nel decimo secolo d.C. i Russi scelgono deliberatamente – secondo Toynbee – di abbracciare il Cristianesimo ortodosso orientale. Essi avrebbero potuto seguire l’esempio dei loro vicini di sud-est, i Kazars delle steppe – che si convertirono al Giudaismo (v. op.cit., p. 242) – o quello dei Bulgari Bianchi, lungo il Volga, che si convertirono all’Islam nel decimo secolo. Essi preferirono invece accogliere il modello religioso di Bisanzio.

Dopo la presa di Costantinopoli da parte dei Turchi nel 1453 e la scomparsa degli ultimi resti dell’Impero Romano d’Oriente, il principato di Mosca assunse in piena coscienza dai Greci l’eredità di Bisanzio.

Nel 1472 il Gran Duca di Mosca, Ivan III, sposò Zoe Paleològos, nipote dell’ultimo imperatore greco di Costantinopoli, ultimo greco a portare la corona dell’Impero Romano d’Oriente. Tale scelta riveste un senso simbolico ben preciso, indicando l’accoglimento e la riproposizione di un archetipo imperiale, come evidenziato da Elémire Zolla.

Nel 1547, Ivan IV (“il Terribile”) “si incoronò Zar, ovvero – scrive Toynbee – Imperatore Romano d’Oriente. Sebbene il titolo fosse vacante, quel gesto di attribuirselo era audace, considerando che nel passato i principi russi erano stati sudditi ecclesiatici di un Metropolita di Mosca o di Kiev, il quale a sua volta era sottoposto al Patriarca Ecumenico di Costantinopoli, prelato politicamente dipendente dall’Imperatore Greco di Costantinopoli, di cui ora il Granduca Moscovita assumeva titolo, dignità e prerogative”.

Nel 1589 fu compiuto l’ultimo e significativo passo, quando il Patriarca ecumenico di Costantinopoli, a quel tempo in stato di sudditanza ai Turchi, fu costretto, durante una sua visita a Mosca, a innalzare il Metropolita di Mosca, già suo subordinato, alla dignità di Patriarca indipendente. Per quanto il patriarcato ecumenico greco abbia mantenuto, nel corso dei secoli fino ad oggi, la posizione di primus inter pares fra i capi delle Chiese ortodosse (le quali, unite nella dottrina e nella liturgia, sono però indipendenti l’una dall’altra come governo), tuttavia la Chiesa ortodossa russa divenne, dal momento del riconoscimento della sua indipendenza, la più importante delle Chiese ortodosse, essendo la più forte come numero di fedeli ed anche perché l’unica a godere dell’appoggio di un forte Stato sovrano.

Nel 1589 fu compiuto l’ultimo e significativo passo, quando il Patriarca ecumenico di Costantinopoli, a quel tempo in stato di sudditanza ai Turchi, fu costretto, durante una sua visita a Mosca, a innalzare il Metropolita di Mosca, già suo subordinato, alla dignità di Patriarca indipendente. Per quanto il patriarcato ecumenico greco abbia mantenuto, nel corso dei secoli fino ad oggi, la posizione di primus inter pares fra i capi delle Chiese ortodosse (le quali, unite nella dottrina e nella liturgia, sono però indipendenti l’una dall’altra come governo), tuttavia la Chiesa ortodossa russa divenne, dal momento del riconoscimento della sua indipendenza, la più importante delle Chiese ortodosse, essendo la più forte come numero di fedeli ed anche perché l’unica a godere dell’appoggio di un forte Stato sovrano.

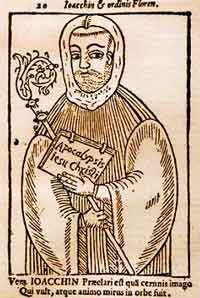

Tale assunzione dell’eredità bizantina non fu un fatto accidentale né il frutto di forze storiche impersonali; secondo lo storico inglese i Russi sapevano benissimo quale ruolo storico avessero scelto di assumere. La loro linea di “grande politica” fu esposta nel sedicesimo secolo con efficace e sintetica chiarezza dal monaco Teofilo di Pakov al Gran Duca Basilio III di Mosca, che regnò fra il terzo e il quarto Ivan (quindi nella prima metà del ‘500):

“La Chiesa dell’antica Roma è caduta a causa della sua eresia; le porte della seconda Roma, Costantinopoli, sono state abbattute dall’ascia dei Turchi infedeli; ma la Chiesa di Mosca, la Chiesa della Nuova Roma, splende più radiosa del sole nell’intero universo… Due Rome sono cadute, ma la Terza è incrollabile; una quarta non vi può essere” .

È significativa questa identificazione esplicita di Mosca con la terza Roma, a indicare l’assunzione, in una nuova forma, dell’ideale romano dell’Imperium, ossia la unificazione di un mosaico di etnie diverse in una entità politica sovranazionale, che è – nella forma storica russa – anche l’autorità da cui dipende quella religiosa ortodossa, così come in precedenza il Patriarca ecumenico di Costantinopoli dipendeva dall’Imperatore di Bisanzio.

In questo messaggio del monaco Teofilo si coglie, inoltre, un esplicito riferimento allo scisma del 1054 d.C. fra le Chiese ortodosse orientali e quella cattolica di Roma, considerata eretica (Toynbee ricorda, al riguardo, la famosa disputa teologica sul “filioque” nel testo del Credo in latino).

Lo storico inglese si chiede perché crollò la Costantinopoli bizantina e perché invece la Mosca bizantina sopravvisse. Egli reputa di trovare la risposta ad entrambi gli enigmi storici in quella che egli chiama “l’istituzione bizantina dello Stato totalitario”, intendendo per tale lo Stato – Impero che esercita il controllo su ogni aspetto della vita dei sudditi. L’ingerenza dello Stato nella vita della Chiesa e la mancanza di autonomia e di libertà di quest’ultima sarebbero state le cause dell’inaridimento delle capacità creative della civiltà bizantina, soprattutto dopo la restaurazione dell’impero di Bisanzio da parte di Leone il Siriano, due generazioni prima della restaurazione dell’Impero d’Occidente da parte di Carlo Magno (restaurazione che Toynbee, da buon inglese fedele ad un’impostazione di preminenza “talassocratica”, considera come un fortunoso fallimento).

La stessa istituzione dello Stato totalitario sarebbe stata invece all’origine della potenza e della continuità storica della Russia, sia perché ne assicurava l’unità interna, sia anche perché tale unità consentiva alla Russia, unitamente alla sua remota posizione geografica rispetto a Bisanzio, di non essere coinvolta nel disfacimento dell’impero bizantino e di restare l’unico Stato sovrano e forte che professasse il cristianesimo ortodosso orientale.

Tale configurazione politica e religiosa implica però che i Russi, nel corso dei secoli, abbiano riferito a se stessi, secondo lo storico inglese, quella primogenitura e supremazia culturale che noi occidentali ci attribuiamo quali eredi della civiltà greco-romana e – secondo Toynbee – anche quali eredi di Israele e dell’Antico Testamento (ma qui il tema si fa più complesso e discusso, perché il cristianesimo occidentale si afferma storicamente in quanto si romanizza e diviene cattolicesimo romano che è fenomeno ben diverso dalla corrente cristiana di Pietro e della primitiva comunità cristiana di Gerusalemme).

Pertanto in tutti i momenti storici in cui vi sia un conflitto, una divergenza di vedute fra l’Occidente e la Russia, per i Russi l’Occidente ha sempre torto e la Russia, quale erede di Bisanzio, ha sempre ragione. Tale antagonismo si manifesta per la prima volta in modo plastico con lo scisma del 1054 fra le Chiese ortodosse orientali e quella di Roma ma è una costante che si sviluppa in tutto il corso della storia russa, seppure con alterne vicende ed oscillazioni, dovute ad una componente filo-occidentale che pur è presente, talvolta, con Pietro il Grande e con la sua edificazione di san Pietroburgo, la più occidentale delle città russe.

Questo Stato totalitario ha avuto due riformulazioni innovative, una appunto con Pietro il Grande e l’altra con Lenin nel 1917. Agli occhi di Toynbee, il comunismo sovietico si configura come una sorta di nuova religione laicizzata e terrestrizzata, di nuova chiesa, ma la Russia nella sua sostanza, resta pur sempre uno Stato-Impero totalitario – nel senso specificato in precedenza - che raccoglie l’eredità simbolica e politico-religiosa dell’Impero Romano d’Oriente. Ciò equivale a vedere – e in questo il suo sguardo era acuto – il comunismo come una sovrastruttura ideologica, come fenomeno di superficie rispetto alla struttura dell’anima russa, rovesciando così l’impostazione del materialismo storico. In quel momento epocale in cui scrive, Toynbee vede un grande dilemma presentarsi davanti alla Russia: se integrarsi nell’Occidente (che egli vede come sinonimo di una civiltà di impronta anche anglosassone e quindi, implicitamente, nel quadro euro-americano) oppure delineare un suo modello alternativo anti-occidentale. La conclusione dello storico inglese – impressionante per la sua lungimiranza – è che la Russia, come anima, come indole del suo popolo, sarà sempre la “santa Russia” e Mosca sarà sempre la “terza Roma”. Tamen usque recurret.

Considerazioni critiche

L’eredità bizantina della Russia è, in ultima analisi l’eredità romana, la visione imperiale come unità sovrannazionale nella diversità, visione geopolitica dei grandi spazi e della grande politica, ivi compresa la proiezione mediterranea, perché un Impero necessita sempre di un suo sbocco sul mare come grande via di comunicazione.

Tale retaggio romano (lo Czar ha una sua precisa assonanza fonetica con il Caesar romano, come già notava Elémire Zolla in Archetipi, ove evidenzia anche la componente fortemente germanica della dinastia dei Romanov) è la base, il fondamento della koiné culturale con l’Europa occidentale ed è anche la linea di demarcazione, di profonda distinzione rispetto agli USA.

Tale retaggio romano (lo Czar ha una sua precisa assonanza fonetica con il Caesar romano, come già notava Elémire Zolla in Archetipi, ove evidenzia anche la componente fortemente germanica della dinastia dei Romanov) è la base, il fondamento della koiné culturale con l’Europa occidentale ed è anche la linea di demarcazione, di profonda distinzione rispetto agli USA.

In altri termini, la Russia è Europa, mentre gli USA risalgono ad un meticciato di impronta culturale protestante e calvinista che è tutta’altra cosa in termini di visione della vita e del mondo, nonché di modello di civiltà.

La teoria del blocco continentale russo-germanico – sostenuta, negli anni ’20 del Novecento dal gruppo degli intellettuali di Amburgo nell’ambito del filone della “rivoluzione conservatrice” – e la visione “euroasiatica” affermata da Karl Haushofer trovano il loro fondamento in questi precedenti storico-culturali, senza la conoscenza dei quali non si comprende la storia contemporanea della Russia, la sua proiezione mediterranea, la sua vocazione ad un ruolo di grande potenza nello scacchiere mondiale.

Sta a noi europei – ed a noi italiani, in particolare, per la specificità della nostra storia e delle nostre origini – ritrovare e diffondere la consapevolezza delle radici comuni euro-russe nella prospettiva auspicabile di un blocco continentale euro-russo che sia un modello distinto e alternativo rispetto a quello “occidentale” di impronta statunitense, sia sul piano politico ma soprattutto su quello “culturale”.

In questa ottica, gioveranno anche altri ulteriori approfondimenti teorico-culturali su temi affini, quali il pensiero di Spengler sull’anima russa, la lettura spengleriana della dicotomia Tolstoj-Dostojevski come simbolo di un’ambivalenza russa, il contributo di Zolla sul rapporto fra la Russia e gli archetipi che essa riprende e sviluppa, l’elaborazione culturale della Konservative Revolution sul rapporto russo-germanico.

Il presente contributo è solo l’inizio di uno studio storico-culturale più ampio.

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : russie, byzance, arnold toynbee, philosophie, philosophie de l'histoire, byzantologie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 26 septembre 2013

PIERRE LE VIGAN : UN OUVRAGE EN PERSPECTIVE

Entretien avec http://metamag.fr

Propos recueillis par Jean PIERINOT

00:05 Publié dans Entretiens | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : pierre le vigan, entretien |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Actualité de René Guénon

Actualité de René Guénon

par Georges FELTIN-TRACOL

René Guénon (1886 – 1951) est mal vu des milieux identitaires qui n’apprécient pas sa conversion à l’islam soufi dès 1911 sous le nom musulman d’Abd el-Wâhed Yahia, « Serviteur de l’Unique ». Quant aux milieux contre-révolutionnaires, outre ce tropisme oriental marqué, ils l’accusent d’être passé par la franc-maçonnerie et certains cénacles gnostiques. Or ces attaques bien trop réductrices éclipsent une œuvre intellectuelle majeure. « La pensée de Guénon constitue un chapitre original, et non négligeable, de l’histoire intellectuelle (p. 488). »

René Guénon (1886 – 1951) est mal vu des milieux identitaires qui n’apprécient pas sa conversion à l’islam soufi dès 1911 sous le nom musulman d’Abd el-Wâhed Yahia, « Serviteur de l’Unique ». Quant aux milieux contre-révolutionnaires, outre ce tropisme oriental marqué, ils l’accusent d’être passé par la franc-maçonnerie et certains cénacles gnostiques. Or ces attaques bien trop réductrices éclipsent une œuvre intellectuelle majeure. « La pensée de Guénon constitue un chapitre original, et non négligeable, de l’histoire intellectuelle (p. 488). »

Par une brillante étude, David Bisson expose d’une manière précise et intelligible le parcours de ce penseur méconnu sans s’arrêter à sa seule vie et à ses idées. Il s’attache aussi à saisir son aura, directe ou non, sur ses contemporains et étudie même sa postérité intellectuelle.

Né à Blois dans un milieu catholique pratiquant, l’enfant Guénon à la santé très fragile se différencie par une intelligence vive et précoce. Sa jeunesse est occultiste, gnostique et pleine de fougue pour le martinisme du « Philosophe inconnu » Louis-Claude de Saint-Martin (1743 – 1803).

L’auteur détermine trois grandes périodes dans la vie de Guénon. De 1906 à 1920, ce sont les années de « l’apprentissage occulte »; puis de 1921 à 1930, le temps de « la reconnaissance intellectuelle », et, enfin, de 1931 à 1951, le moment de « l’accomplissement doctrinale ». Cette dernière commence le 5 mars 1930 quand Guénon part pour Le Caire sans savoir qu’il ne reviendra jamais plus en France.

L’éloignement géographique ne l’empêche pas de suivre avec attention l’activité de ses disciples. Le chercheur rapporte que l’homme du Caire relit toujours tous les articles paraissant dans la revue Études Traditionnelles. Par ailleurs, c’est un grand épistolier qui dispose d’« un réseau international de correspondants (p. 163) ».

La publication de livres, la rédaction d’articles et de recensions ainsi que l’envoi de ses missives forment un ensemble théorique complet. Guénon construit ainsi une œuvre entre l’unité intellectuelle (la métaphysique) et la réalité métahistorique (la tradition). La notion de métahistoire est très importante, car « pour Guénon, l’histoire n’est que contrefaçon. Elle correspond à la dernière étape d’un processus de déclin qui s’accélère au fur et à mesure que l’humanité avance dans l’âge sombre (p. 103) ». En revanche, hors de ce champ profane existe la Tradition. « Une partie essentielle de la pensée guénonienne tient dans cette formule imaginée : d’un côté, la Tradition se déploie en de multiples branches en fonction des conditions historiques et des aires géographiques et, de l’autre, le monde moderne a rompu avec ses attaches traditionnelles jusqu’à mettre en péril l’équilibre universel. D’où le remède envisagé : se ressourcer dans la connaissance orientale afin de retrouver son axe véritable (p. 45). » Or comment faire concrètement ? Se pose ici la question de l’initiation largement développée par l’auteur. Pour Guénon, l’initiation relève d’un groupe rattaché à une tradition viable parce que « la tradition primordiale doit effectivement déboucher sur une réalisation métaphysique, c’est-à-dire une voie de ressourcement intérieur qui engage l’individu sur le chemin de la connaissance (p. 81) ». Les modes d’accès en Occident sont la franc-maçonnerie demeurée opérative et non pas sa version spéculative et laïciste, et l’Église catholique. Mais il reconnaît que ces deux voies sont presque fermées et invite ceux qui le souhaitent à se convertir à une religion d’Orient, l’islam par exemple. Pour les personnes tentées par l’hindouisme, il les invite à s’installer en Inde. René Guénon est conscient de sa fonction de pôle intellectuel. Son « écriture […] comporte une part vocationnelle. Elle doit dire la métaphysique dans une “ langue profane ”, c’est-à-dire rappeler les principes immémoriaux de la connaissance à un monde coupé de ses racines transcendantes (p. 91). »

Les écrits de Guénon favorise au fil des années la formation de groupes soufis en Europe ainsi qu’un courant spiritualiste au sein de la franc-maçonnerie. Bien entendu, toutes ces initiatives demeurent confidentielles.

David Bisson consacre une longue partie de son essai à la période 1951 – 1980 et à l’ascendance post mortem de Guénon. Déjà, de son vivant, il intriguait déjà quelques fins lettrés : Pierre Drieu la Rochelle ou la philosophe de l’enracinement et amie indéniable du monde ouvrier Simone Weil qui « a lu avec intérêt les ouvrages de Guénon sans pour autant épouser la perspective traditionnelle (p. 295) ».

Dès les années 1930, René Guénon rencontre un élève talentueux en la personne de Frithjof Schuon. Converti à l’islam et devenu très tôt cheikh (chef spirituel) d’une tarîqa (communauté) soufie, Schuon entend régler la question de l’initiation des Européens par l’islam. Il déclare ainsi qu’« il faut islamiser l’Europe (p. 172) » avant de revenir à des dispositions plus nuancées. Après 1945, le musulman Schuon est devenu un fin connaisseur du christianisme. Il considère que les sacrements chrétiens font des chrétiens des initiés involontaires ou ignorants. Il vouera ensuite un culte particulier à la Vierge Marie et s’ouvrira au chamanisme amérindien. En 1981, Schuon s’installe aux États-Unis dans l’Indiana d’où il décédera dix-sept ans plus tard.

Dès les années 1930, René Guénon rencontre un élève talentueux en la personne de Frithjof Schuon. Converti à l’islam et devenu très tôt cheikh (chef spirituel) d’une tarîqa (communauté) soufie, Schuon entend régler la question de l’initiation des Européens par l’islam. Il déclare ainsi qu’« il faut islamiser l’Europe (p. 172) » avant de revenir à des dispositions plus nuancées. Après 1945, le musulman Schuon est devenu un fin connaisseur du christianisme. Il considère que les sacrements chrétiens font des chrétiens des initiés involontaires ou ignorants. Il vouera ensuite un culte particulier à la Vierge Marie et s’ouvrira au chamanisme amérindien. En 1981, Schuon s’installe aux États-Unis dans l’Indiana d’où il décédera dix-sept ans plus tard.

Schuon insiste sur une « gnose universaliste (p. 332) » et s’apparente parfois à un syncrétisme qui met mal à l’aise d’autres fidèles guénoniens comme Michel Vâlsan, le gardien d’un soufisme guénonien de stricte observance. Des traditionalistes accusent Schuon de se faire « le porte-parole d’un ésotérisme universaliste ou essentialiste qui tend à dépasser le cadre limité des formes traditionnelles (p. 356) ».

Outre Schuon qui s’oriente vers de « nouvelles voies spirituelles », expression plus appropriée que « nouveaux mouvements religieux (p. 468) », David Bisson ne peut pas ne pas mentionner l’Italien Julius Evola dont les réflexions suscitent de fortes contestations de la part des milieux guénoniens. Si « l’auteur italien a trouvé […] le moyen de ne pas sombrer dans le nihilisme grâce à ses lectures traditionnelles. Ainsi, l’homme doit être capable de s’ouvrir à la transcendance pour faire de la volonté pure une source de transfiguration (p. 229) », il n’en demeure pas moins qu’Evola fait figure d’hétérodoxe de la Tradition par ses prises de position politiques radicales, ses références païennes et son engagement partisan.

Plus surprenant, on apprend que Carl Schmitt était lui aussi un lecteur assidu du Français du Caire sans être pour autant traditionaliste primordial. Il en déduit surtout une nouvelle forme d’« étaticité ». « La tradition oubliée et la religion dépecée, Schmitt tente de construire un nouveau rempart contre l’homme lui-même : l’État souverain et décisionniste (p. 281). »

David Bisson prévient toutefois que René Guénon « garde une certaine méfiance vis-à-vis des auteurs qui accordent une place trop importante à la sphère politique. Une nouvelle fois, il s’agit de protéger la Tradition de toutes récupérations partisanes (p. 170) ». Le message guénonien se veut apolitique ou même anti-politique. « À la différence du conservateur, le penseur antimoderne s’attache à la défense de valeurs établies (statu quo ante) qu’il ne projette ses propres valeurs, considérées comme éternelles, dans l’histoire présente et à venir (p. 9). » Existe cependant un cas particulier, le Roumain Mircea Eliade.

Pendant l’Entre-Deux-Guerres, ce jeune homme doué a déjà lu Guénon et a séjourné en Inde de 1929 à 1931. Puis, de retour en Roumanie, de 1932 à 1935, ses centres d’intérêt sont philosophiques, religieux et historiques. Il se détourne de la politique et ne se commet pas avec la Garde de Fer de Corneliu Codreanu. Si certains guénoniens roumains s’en détournent, d’autres au contraire le rejoignent avec enthousiasme. Puis, entre 1935 et 1938, Eliade milite au sein de la Légion de l’Archange Saint-Michel en compagnie d’un autre grand esprit dace du XXe siècle, Cioran. Suite à quelques avanies politiques, Eliade cesse toute activité militante en 1938, prend ses distances avec la Tradition et commence à travailler sur l’histoire des religions. La distanciation avec la politique semble être une constante dans la pensée guénonienne. Néanmoins, David Bisson estime que la pensée de Guénon porte en elle une indéniable part politique qui se vérifient avec le parcours d’Eliade. « Plus que l’engagement politique des années trente, circonstancié et ponctuel, c’est le cadre normatif dans lequel Eliade inscrit toute sa pensée qui le relie à Guénon. Si les deux hommes ne partagent pas exactement les mêmes conceptions, ils forgent leurs idées dans le même creuset idéologique (p. 388). » Sa brillante carrière postérieure à la seconde Guerre mondiale a soulevé de virulentes controverses. désormais universitaire reconnu aux États-Unis, Eliade ne préoccupe que de l’homo religiosus, sujet bien éloigné de ses engagements de jeunesse. David Bisson fait preuve à ce sujet d’une grande objectivité intellectuelle, contrairement aux dénommés Alexandra Laignel – Lavastine et Daniel Dubuisson, petits épurateurs de la douze millième heure…

Nombreux sont les héritiers, revendiqués ou putatifs, de Guénon. L’auteur mentionne Raymond Abellio qui veut « partir de Guénon pour mieux le dépasser (p. 429) ». de ce fait, les thèmes abelliennes, concrétisés par la « Structure absolue », célèbrent l’« auto-initiation de l’individu, [la] création d’une nouvelle dialectique, [la] dimension messianique de l’Occident, etc. (p. 430) », qui vont à l’encontre des orientations traditionnelles. Le désaccord majeur entre Guénon et Abellio porte sur l’initiation. « Là où Guénon évoque la transmission d’une influence spirituelle au sein de groupes initiatiques légitimement constitués, Abellio insiste sur la dimension individuelle et le processus rationnel qui débouche sur la transfiguration du monde dans l’homme. Ce qui évite, d’une part, les débats “ sectaires ” relatifs à la régularité de telle ou telle chaîne initiatique et permet, d’autre part, la reprise sans cesse renouvelé du chemin gnostique (pp. 432 – 433). »

Dans son Manifeste de la nouvelle gnose (Gallimard, coll. « N.R.F. – Essais », 1989), Abellio qualifie René Guénon d’« ésotériste réactionnaire (Abellio, op. cit., p. 60) » et, hormis Schuon envers qui il se montre élogieux, il critique « les traditionalistes guénoniens [qui] refusent de considérer que l’œuvre de Guénon, si efficace qu’elle ait été dans l’« épuration » du fatras occultiste des siècles passés et notamment du XIXe siècle, est essentiellement non dialectique et, comme telle, improductive pour l’avenir. Aussi en sont-ils réduits à répéter pieusement les anathèmes de leur maître (Abellio, op. cit., note 32, p. 95) ».

En Iran, lecteur de Guénon et disciple de Schuon, Seyyed Hossein Nasr élabore en accord avec le Shah un cadre traditionaliste-intégral musulman. Bisson le signale rapidement mais une partie des sources théoriques de la révolution islamique de 1979 qui obligera Nasr à s’exiler aux États-Unis ont pour noms Guénon et Heidegger… Mais c’est dans l’Université française qu’on assiste à une lente découverte de la pensée de Guénon. En général, « le nom de Guénon est très rarement cité dans les ouvrages scientifiques alors même que certains de leurs auteurs puisent dans ces textes une source non négligeable d’inspiration (p. 379) ». Sans le nommer ouvertement, Henry Corbin s’en inspire. Ami de Denis de Rougemont, lecteur de Heidegger et spécialiste réputé du chiisme iranien, Corbin « partage le sentiment de nombreux non-conformistes qui prônent dans un même élan la révolution spirituelle (contre l’esprit matérialiste) et la libération individuelle (contre la société bourgeoise) (p. 393) ».

Il n’entérine pas totalement l’enseignement du Cairote d’origine française. « Chez Guénon, toutes les traditions religieuses proviennent d’un noyau primordial et ésotérique tandis que chez Corbin, toutes les gnoses monothéistes confluent vers le même sommet herméneutique (p. 403). » L’auteur signale que le seul universitaire qui se réfère clairement à Guénon est l’« intellectuel antimoderne (p. 407) » Gilbert Durand. Inspiré par son ami Corbin et par « Nietzsche, Spengler, Maistre, etc. (p. 408) », Durand travaille en faveur d’une « science traditionnelle (p. 406) » et pose des « jalons pour une réaction antimoderne (p. 409) ». Corbin, Eliade, Durand, Carl Gustav Jung, etc., participent chaque année aux « rencontres d’Eranos » en Suisse. Bisson y voit dans ces réunions annuelles « un réseau intellectuel international (p. 414) » de sensibilité non-moderne.

La présence de Guénon est plus forte encore chez « Jean Hani, Jean Biès et Jean Borella [qui] tiennent finalement une place particulière dans la galaxie traditionniste. Outre leur formation universitaire, ils ont toujours cherché à concilier Guénon, le “ maître de doctrine ”, avec son principal continuateur, Schuon, le “ maître de spiritualité ”. […] Ils peuvent être considérés comme les premiers intellectuels chrétiens d’inspiration guénonienne (p. 479) ». Le philosophe eurasiste russe et orthodoxe vieux-croyant Alexandre Douguine reconnaît volontiers la dette qu’il doit à l’auteur d’Orient et Occident. Il cite d’ailleurs cet ouvrage dans son essai Pour une théorie du monde multipolaire (Ars Magna Éditions, 2013).

David Bisson constate dans la décennie 1960 l’essor oxymorique d’un « ésotérisme de masse » sous la férule de l’homme de presse Louis Pauwels. Co-auteur du Matin des magiciens avec Jacques Bergier qui méconnaît Guénon et exècre Evola, Pauwels poursuit sa démarche de vulgarisation ésotérique avec la revue Planète quand bien même des thèmes non traditionnelles (extra-terrestres, télépathie…). Pourquoi l’auteur étend-il ensuite ses recherches à la « Nouvelle Droite » (N.D.) ? La personnalité de Pauwels sert-elle de fil-conducteur ou bien parce que ce courant de pensée reprend à son compte le concept de métapolitique ? Alain de Benoist « réactualise le terme “ métapolitique ” dans deux sens complémentaires : la constitution d’un “ appareil d’action intellectuelle ” et le façonnement d’une socialité organique (p. 454) ». Or, terme technique de l’idéalisme allemand, repris par Joseph de Maistre dans son Essai sur le principe générateur des constitutions politiques et des autres institutions humaines, la métapolitique « ancre le politique (versant critique et propositionnel) dans un socle métaphysique (versant idéel et référentiel). C’est ensuite un adjectif qualificatif (“ le combat métapolitique ”) qui caractérise une posture intellectuelle de surplomb par rapport aux luttes partisans (p. 19) ». David Bisson avoue la grande complexité de démêler les multiples influences de la N.D. Toutefois, Guénon ne représente pas une figure tutélaire à la différence de Julius Evola. Quant à Alain de Benoist, il eut peut-être une période traditionaliste à la fin des années 1980, marqué par un recueil intitulé L’empire intérieur (1995) avant de suivre une autre direction plus post-moderne…

Finalement, sous une apparence volontairement détachée de la politique, la pensée de René Guénon serait très politique, ce qui renforcerait ses liens avec à son « véritable maître caché […] Joseph de Maistre. […] Ce sont des traditionalistes illuminés, c’est-à-dire des penseurs qui réinterprètent la tradition à l’aune de leurs propres révélations (p. 131) ». Quoi qu’il en soit, il importe de relire ou de découvrir l’œuvre considérable de Guénon et de prendre connaissance du livre captivant de David Bisson qui doit faire date dans l’histoire des idées.

Georges Feltin-Tracol

• David Bisson, René Guénon. Une politique de l’esprit, Pierre-Guillaume de Roux, 2013, 527 p., 29,90 €.

Article printed from Europe Maxima: http://www.europemaxima.com

URL to article: http://www.europemaxima.com/?p=3317

00:05 Publié dans Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : rené guénon, traditionalisme, tradition |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Monothéisme et laïcité : un débat capital

Monothéisme et laïcité : un débat capital

Guillaume Faye

Ex: http://www.gfaye.com

Le philosophe Luc Ferry a publié dans Le Figaro (22/08/2013) une chronique intitulée « De la place des religions » dans laquelle il développe l’opinion selon laquelle la laïcité (avec pour corollaire l’autonomie des lois par rapport à la sphère théologique) serait une idée essentiellement d’origine chrétienne, qui échapperait aux autres religions. Son analyse, très brillante, souffre néanmoins de lacunes. Mais tout d’abord, il faut résumer la forte thèse de Luc Ferry.