Le dernier essai de Jean Vioulac est à la fois ample dans son déroulement parce qu'il nous fait naviguer dans les hautes eaux de toute la philosophie occidentale, et terrifiant dans sa perspective parce qu'il nous indique le point d'arrivée : " L'universel réduction au Même et au Pareil ". D'où son titre : La logique totalitaire. Essai sur la crise de l'Occident. Or, il y a des crises (systémiques et métaphysiques) dont on ne peut pas sortir parce qu'elles arrivent tout simplement au terme d'un processus, et recouvrent l'ensemble de ses étapes de la finalité qu'elles portaient en leurs seins depuis le départ. Pour Jean Vioulac, il s'agit ni plus ni moins de la fin de la philosophie en ce qu'elle est parvenue à l'arraisonnement total du monde : conceptuel, politique, technique, économique, social, etc. Tout est soumis à l'universalité abstraite dont le capitalisme est l'ultime avatar, avant extinction des feux.

Le dernier essai de Jean Vioulac est à la fois ample dans son déroulement parce qu'il nous fait naviguer dans les hautes eaux de toute la philosophie occidentale, et terrifiant dans sa perspective parce qu'il nous indique le point d'arrivée : " L'universel réduction au Même et au Pareil ". D'où son titre : La logique totalitaire. Essai sur la crise de l'Occident. Or, il y a des crises (systémiques et métaphysiques) dont on ne peut pas sortir parce qu'elles arrivent tout simplement au terme d'un processus, et recouvrent l'ensemble de ses étapes de la finalité qu'elles portaient en leurs seins depuis le départ. Pour Jean Vioulac, il s'agit ni plus ni moins de la fin de la philosophie en ce qu'elle est parvenue à l'arraisonnement total du monde : conceptuel, politique, technique, économique, social, etc. Tout est soumis à l'universalité abstraite dont le capitalisme est l'ultime avatar, avant extinction des feux. samedi, 23 novembre 2013

Le règne de la totalité et la fin de l'humain

Le dernier essai de Jean Vioulac est à la fois ample dans son déroulement parce qu'il nous fait naviguer dans les hautes eaux de toute la philosophie occidentale, et terrifiant dans sa perspective parce qu'il nous indique le point d'arrivée : " L'universel réduction au Même et au Pareil ". D'où son titre : La logique totalitaire. Essai sur la crise de l'Occident. Or, il y a des crises (systémiques et métaphysiques) dont on ne peut pas sortir parce qu'elles arrivent tout simplement au terme d'un processus, et recouvrent l'ensemble de ses étapes de la finalité qu'elles portaient en leurs seins depuis le départ. Pour Jean Vioulac, il s'agit ni plus ni moins de la fin de la philosophie en ce qu'elle est parvenue à l'arraisonnement total du monde : conceptuel, politique, technique, économique, social, etc. Tout est soumis à l'universalité abstraite dont le capitalisme est l'ultime avatar, avant extinction des feux.

Le dernier essai de Jean Vioulac est à la fois ample dans son déroulement parce qu'il nous fait naviguer dans les hautes eaux de toute la philosophie occidentale, et terrifiant dans sa perspective parce qu'il nous indique le point d'arrivée : " L'universel réduction au Même et au Pareil ". D'où son titre : La logique totalitaire. Essai sur la crise de l'Occident. Or, il y a des crises (systémiques et métaphysiques) dont on ne peut pas sortir parce qu'elles arrivent tout simplement au terme d'un processus, et recouvrent l'ensemble de ses étapes de la finalité qu'elles portaient en leurs seins depuis le départ. Pour Jean Vioulac, il s'agit ni plus ni moins de la fin de la philosophie en ce qu'elle est parvenue à l'arraisonnement total du monde : conceptuel, politique, technique, économique, social, etc. Tout est soumis à l'universalité abstraite dont le capitalisme est l'ultime avatar, avant extinction des feux.

00:03 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Philosophie, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, totalitarisme, théorie politique, sciences politiques, politologie, logique totalitaire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 22 novembre 2013

Le tireur de Libération: un ami du journal

Il voyait des fascistes partout

Raoul Fougax

Ex: http://metamag.fr

09:04 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : tireur fou, politique internationale, france, europe, affaires européennes, délires, paris, terrorisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Tientallen burgerorganisaties roepen op tot tweede Amerikaanse revolutie

'Obama heeft ongekende veiligheidsstaat opgezet, met meer macht dan de SS, de Stasi en de KGB bij elkaar'

Oud-admiraal Lyons uitte forse kritiek op Obama, die militairen in Afghanistan heeft verboden in te grijpen bij misdaden zoals het verkrachten van zeer jonge kinderen, omdat ze respect voor de daar heersende islamitische cultuur moeten hebben.

Zeker 30 burgerorganisaties en - groepen, waaronder 2 Million Bikers tot DC, Jihad Watch, Freedom Watch, Gun Owners of America, Accuracy in Media, Tea Party Patriots en het Western Center for Journalism hebben zich verenigd in de Reclaim America Now coalitie, die hoopt dat er een tweede Amerikaanse revolutie komt om het land te ontdoen van president Obama en de corrupte politieke kliek in Washington.

Larry Klayman, voormalig advocaat bij het ministerie van Justitie onder president Reagan, hoopt dat 19 november ooit dezelfde status zal krijgen als 4 juli, de Amerikaanse Onafhankelijkheidsdag. Tijdens een kleinschalige demonstratie van de conservatieve coalitie in Washington riep hij 19 november uit als het begin van de 'Tweede Amerikaanse Revolutie'.

Genoeg van tirannie en corruptie

Klayman beschuldigde Obama van het vestigen van een tiranniek bewind in Amerika, en eiste zijn aftreden. 'Wij, het volk, hebben genoeg van de corrupte en incompetente koers van de regering Obama en zijn steunbetuigers bij beide politieke partijen. Het is tijd voor actie, geen woorden.'

'In de stijl van Gandhi, Martin Luther King en anderen die de geschiedenis hebben veranderd en de vrijheid hebben herwonnen, hebben Amerikanen geen andere keus. De drie takken van de regering hebben compleet afstand gedaan van het vertegenwoordigen van de klachten van het volk. Als de zaken in Washington niet veranderen, moet de overheid bang zijn dat het volk in opstand zal komen.'

Ook oud-senator Gordon Humprey waarschuwde dat 'we ons op de rand van tirannie bevinden, en dat is niet overdreven. Het is ons doel deze beginnende tirannie terug te duwen, en opnieuw de vrijheid te bewerken voor de komende generaties.' Volgens Humprey heeft de regering Obama een 'ongekende veiligheidsstaat' opgezet, met 'meer macht dan de SS, de Stasi en de KGB bij elkaar.' De belastingdienst (IRS) is een middel geworden om degenen die zich uitspreken tegen de regering lastig te vallen.

Gestoord, verraad en taqiya

Een andere spreker, oud-admiraal James Lyons, wees erop hoe 'gestoord' Obama de situatie voor militairen in Afghanistan heeft gemaakt. Zo mogen de militairen niet ingrijpen als een Afghaanse man zijn vrouw slaat of een 5-jarig kind verkracht - waargebeurde voorvallen die enige tijd geleden in het nieuws zijn geweest-, omdat 'wij voldoende rekening moeten houden met hun 7e eeuwse (islamitische) waarden.'

Lyons noemde het 'verraad' dat de leden van SEAL team VI, die Bin Laden zouden hebben gedood, tijdens een verdacht helikopterongeluk in augustus 2011 allemaal om het leven kwamen. De helikopter zou zijn neergehaald door terroristen, maar critici geloven dat Obama van het team af wilde, om te voorkomen dat de waarheid rond het veronderstelde uitschakelen van Bin Laden boven tafel zou komen.

Naast het Benghazischandaal, dat op 11 september 2012 ontstond toen Amerikaanse troepen het bevel kregen niet in te grijpen toen terroristen het consulaat aanvielen, waardoor de ambassadeur en enkele andere Amerikanen om het leven kwamen, noemde de oud-admiraal ook Iran, waarmee onderhandelen geen zin zou hebben vanwege 'taqiya, de islamitische richtlijn die moslims toestemming geeft te liegen als dat hun religie dient.'

Linkse indoctrinatie op scholen

Voorganger Michael Carl bekritiseerde de linkse overheidsindoctrinatie op scholen, waarmee de scholieren een verdraaid beeld van de geschiedenis wordt geleerd, zodat ze de 'progressieve' agenda van de regering gaan steunen. Echt herstel van Amerika komt volgens hem niet van een politicus, maar van het volk. 'Bedenk eens wat er kan gebeuren als we op God vertrouwen en Hem onderdanig zijn.'

Volgens Brooke McGowan van het Tea Party News Network bevindt de VS zich nu onder Gods oordeel. Ook zij riep de bevolking daarom op om tot Hem terug te keren en Zijn leiding te zoeken. (1)

Xander

(1) World Net Daily

Zie ook o.a.:

15-11: Oud studiegenoot: Obama wil VS en christelijk Amerika van binnenuit vernietigen

03-11: Time journalist: Obama zei heel goed te zijn in moorden

25-10: Militairen in VS krijgen te horen dat christenen de nieuwe vijand zijn

11-10: 'Obama kan shutdown gebruiken om absolute macht te grijpen'

12-09: Gigantisch anti-Obama protest in VS genegeerd door media

24-08: Bios-docu '2016: Obama's America' schetst duistere toekomst VS

15-08: Belangrijke peiling: Amerikanen banger voor Obama dan voor terrorisme

25-06: Ex-leider spionagedienst Oostblok: Obama meester in verspreiden desinformatie

18-06: Global Research denktank: Obama veel erger dan George Bush

11-06: Zal Amerika Obama's tweede termijn overleven?

10-06: Glenn Beck: Stop Obama, of wij worden het kwaadaardigste land ooit

09-06: Amerikaanse volkspetitie eist aftreden president Obama

08-06: Obama's verleden: Communisten VS planden al in 1983 overname Witte Huis tijdens economische crisis

25-05: Irak veteraan roept op tot gewapende opstand tegen regering Obama

22-05: Sterjournalist CBS: Obama heeft blokkeren info aan publiek eperfectioneerd

06-03: WikiLeaks (7): Obama in 2008 gekozen door stembusfraude en Russisch geld

03-03: Plotseling overleden journalist had extreem belastende video's Obama met terroristen

07-02: Witte Huis lanceert 'Cyber-Warriors for Obama' project tegen conservatieve sites

2011:

30-12: Overheidswaakhond VS noemt Barack Obama bij 10 meest corrupte politici

2010:

03-05: Boek 'The Manchurian President' bewijst extreem radicale agenda Obama

2009:

19-10: Witte Huis: 'Wij controleren de media volledig'

21-05: Pravda ziet Amerika pijlsnel veranderen in Marxistische slavenstaat

27-01: Alex Jones: 'Obama wordt een tweede Adolf Hitler'

00:05 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : politique internationale, actualité, états-unis, obama |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

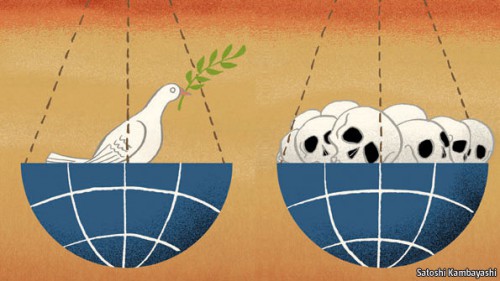

La "Responsabilité de protéger" (R2P) comme instrument d'agression

La « responsabilité de protéger » est une fausse doctrine conçue pour miner les fondements mêmes du droit international. C’est le droit réécrit en faveur des puissants. « Les structures et les lois qui fondent l’application de la R2P exemptent bel et bien les Grandes Puissances – défenseurs du droit international – du respect des lois et des règles mêmes qu’elles imposent aux autres pays.»

La « responsabilité de protéger » est une fausse doctrine conçue pour miner les fondements mêmes du droit international. C’est le droit réécrit en faveur des puissants. « Les structures et les lois qui fondent l’application de la R2P exemptent bel et bien les Grandes Puissances – défenseurs du droit international – du respect des lois et des règles mêmes qu’elles imposent aux autres pays.»La Responsabilité de Protéger (R2P) et le concept d’intervention humanitaire datent tous les deux du lendemain de l’effondrement de l’Union Soviétique – qui levait subitement toutes les entraves que cette Grande Puissance avait pu jusqu’ici opposer à la constante projection de puissance des États-Unis. Dans l’idéologie occidentale, bien sûr, les États-Unis s’étaient efforcés depuis la Seconde Guerre mondiale de contenir les Soviétiques ; mais ça, c’est l’idéologie… En réalité, l’Union Soviétique avait toujours été bien moins puissante que les États-Unis, avec des alliés plus faibles et moins fiables, et de 1945 à sa disparition en 1991 elle avait finalement toujours été sur la défensive. Agressivement lancés à la conquête du monde depuis 1945, les États-Unis, eux, n’avaient de cesse d’augmenter le nombre de leurs bases militaires dans le monde, de leurs sanglantes interventions grandes ou petites sur tous les continents, et bâtissaient méthodiquement le premier empire véritablement planétaire. Avec une puissance militaire suffisante pour constituer une modeste force d’endiguement, l’Union Soviétique freinait l’expansionnisme américain mais elle servait aussi la propagande américaine en tant que soi-disant menace expansionniste. L’effondrement de l’Union Soviétique engendrait donc un besoin vital de nouvelles menaces pour justifier la continuation voire l’accélération de la projection de puissance américaine, mais on pouvait toujours en trouver : depuis le narco-terrorisme, Al-Qaïda et les armes de destruction massive de Saddam Hussein, jusqu’à une nébuleuse menace terroriste dépassant les limites de la planète et de l’espace environnant.

Tensions inter-ethniques et violations des Droits de l’Homme ayant engendré une prétendue menace globale, planétaire, contre la sécurité, qui risquait de provoquer des conflits encore plus vastes, la communauté internationale (et son superflic) se retrouvaient face à un dilemme moral et à la nécessité d’intervenir dans l’intérêt de l’humanité et de la justice. Comme nous l’avons vu, cette poussée moraliste arrivait justement au moment où disparaissait l’entrave soviétique, où les États-Unis et leurs proches alliés célébraient leur triomphe, où l’option socialiste battait de l’aile et où les puissances occidentales avaient enfin toute liberté d’intervenir à leur guise. Bien sûr, tout cela impliquait de passer outre le principe westphalien multiséculaire gravé au centre des relations internationales – à savoir le respect de la souveraineté nationale – qui, si l’on y adhérait, risquait de protéger les pays les plus petits et les plus faibles contre les ambitions et les agressions transfrontalières des Grandes Puissances. Cette règle était en outre l’essence même de la Charte des Nations Unies et on peut dire qu’elle était même la clé de voûte de ce document que Michael Mandel décrivait comme « la Constitution du monde ». Passer outre cette règle et le principe de base de cette Charte impliquait l’entrée en lice de la Responsabilité de Protéger (R2P) et des Interventions Humanitaires (IH), et ouvrait à nouveau la voie à l’agression pure et simple, classique, avec des visées géopolitiques, mais parée désormais du prétexte commode de la R2P et de l’IH.

Bien évidemment, lancer des interventions humanitaires transfrontalières au nom de la R2P reste l’apanage absolu des Grandes Puissances – spécificité communément admise et regardée comme parfaitement naturelle à chaque fois que ces mesures ont été appliquées au cours des dernières années. Les Grandes Puissances sont seules à disposer des connaissances et des moyens matériels nécessaires pour mener à bien cette œuvre sociale planétaire. En effet, comme l’expliquait en 1999 Jamie Shea, responsable des relations publiques de l’OTAN, lorsque on commença à se demander si le personnel de l’OTAN ne risquait pas d’être poursuivi pour les crimes de guerre liés à la campagne de bombardements de l’OTAN contre la Serbie, ce qui découlait logiquement du texte même de la Charte du TPIY (Tribunal Pénal International pour l’ex-Yougoslavie) : Les pays de l’OTAN ont « organisé » le TPIY et la Cour Internationale de Justice, et les pays de l’OTAN « financent ces tribunaux et soutiennent quotidiennement leurs activités. Nous sommes les défenseurs, non les violateurs du droit international ». La dernière phrase est évidemment contestable mais pour le reste, Shea avait parfaitement raison.

Détail particulièrement éloquent, lorsqu’un groupe de juristes indépendants déposa en 1999 un dossier détaillé qui documentait les violations manifestes des règles du TPIY par l’OTAN, après un délai considérable et suite à des pressions exercées ouvertement par les responsables de l’OTAN, les plaintes contre l’OTAN étaient déboutées par le Procureur du TPIY au prétexte que, avec seulement 496 victimes documentées tuées par les bombardements de l’OTAN, il n’y avait « simplement aucune preuve d’intention criminelle » imputable à l’OTAN – alors que pour inculper Milosevic en mai 1999, 344 victimes suffisaient largement. On trouvera intéressant aussi que le Procureur de la Cour Pénale Internationale (CPI), Luis Moreno-Ocapmo, ait lui aussi refusé de poursuivre les responsables de l’OTAN pour leur agression contre l’Irak en 2003, malgré plus de 249 plaintes portées auprès de la CPI, au prétexte que là aussi, « il n’apparaissait pas que la situation ait atteint le seuil requis par le Statut de Rome » pour intenter une action en justice.

Ces deux cas montrent assez clairement que les structures et les lois qui fondent l’application de la R2P (et des IH) exemptent bel et bien les Grandes Puissances – défenseurs du droit international – du respect des lois et des règles mêmes qu’elles imposent aux autres pays. Leurs alliés et clients en sont d’ailleurs exempts aussi. Ce qui signifie très clairement que, dans le monde réel, personne n’a le devoir de protéger les Irakiens ou les Afghans contre les États-Unis, ou les Palestiniens contre Israël. Lorsque sur une chaîne nationale en 1996, la Secrétaire d’État américaine, Madeleine Albright, reconnaissait que 500 000 enfants irakiens [de moins de cinq ans] avaient sans doute perdu la vie, victimes des sanctions imposées à l’Irak par l’ONU (en réalité par les États-Unis), et déclarait : Pour les responsables américains « l’enjeu en vaut la peine » ; il n’y eut de réaction ni sur le plan national ni sur le plan international pour exiger la levée de ces sanctions et le déclenchement d’une IH en application de la R2P, afin de protéger les populations irakiennes qui en étaient victimes. De même aucun appel ne fut lancé pour une IH au nom de la R2P pour protéger ces mêmes Irakiens lorsque les forces anglo-américaines envahirent l’Irak en mars 2003 ; invasion qui, doublée d’une guerre civile induite, allait faire plus d’un million de morts supplémentaires.

Lorsque la Coalition Internationale pour la Responsabilité de Protéger, sponsorisée par le Canada, se pencha sur la guerre d’Irak, ses auteurs conclurent que les exactions commises en Irak par Saddam Hussein en 2003, n’étaient pas d’une ampleur suffisante pour justifier une invasion. Mais la coalition ne souleva jamais la question de savoir si les populations irakiennes n’auraient pas de facto besoin d’être protégées contre les forces d’occupation qui massacraient la population. Ils campaient simplement sur l’idée que les Grandes Puissances, qui imposent le respect du droit international, même lorsque leurs guerres d’agression violent ouvertement la Charte des Nations Unies et font des centaines de milliers de morts, restent au-dessus des lois et ne peuvent faire l’objet d’une R2P.

Lorsque la Coalition Internationale pour la Responsabilité de Protéger, sponsorisée par le Canada, se pencha sur la guerre d’Irak, ses auteurs conclurent que les exactions commises en Irak par Saddam Hussein en 2003, n’étaient pas d’une ampleur suffisante pour justifier une invasion. Mais la coalition ne souleva jamais la question de savoir si les populations irakiennes n’auraient pas de facto besoin d’être protégées contre les forces d’occupation qui massacraient la population. Ils campaient simplement sur l’idée que les Grandes Puissances, qui imposent le respect du droit international, même lorsque leurs guerres d’agression violent ouvertement la Charte des Nations Unies et font des centaines de milliers de morts, restent au-dessus des lois et ne peuvent faire l’objet d’une R2P.Et c’est comme ça depuis le sommet de la structure internationale du pouvoir, jusqu’en bas : Bush, Cheney, Obama, John Kerry, Susan Rice, Samantha Power au sommet et en descendant Merkel, Cameron, Hollande, puis au-dessous Ban Ki-Moon et Luis Moreno-Ocampo – qui n’ont aucune base politique en dehors du monde des affaires et des médias. Ban Ki-Moon et son prédécesseur Kofi Annan ont toujours œuvré ouvertement au service des principales puissances de l’OTAN, auxquelles ils doivent leur position et leur autorité. Kofi Annan était un fervent partisan de l’agression de l’OTAN contre la Yougoslavie, de la nécessité de renforcer la responsabilité des puissances de l’OTAN, et de l’institutionnalisation de la R2P. Ban Ki-Moon est exactement sur la même fréquence.

Cette même structure internationale du pouvoir implique aussi la possibilité de créer et d’utiliser à volonté des tribunaux internationaux ad hoc et des Cours Internationales contre des pays cibles. Ainsi en 1993, lorsque les États-Unis et leurs alliés souhaitaient démanteler la Yougoslavie et affaiblir la Serbie, ils n’avaient qu’à utiliser le Conseil de Sécurité [dont les États-Unis, l’Angleterre et la France sont membres permanents] pour créer un tribunal précisément à cet effet, le TPIY, qui allait s’avérer parfaitement fonctionnel. De même, lorsqu’ils souhaitaient aider un de leurs clients, Paul Kagame, à assoir sa dictature au Rwanda, ils créèrent le même type de tribunal : le TPIR (ou tribunal d’Arusha). Lorsque ces mêmes pays souhaitèrent attaquer la Libye et en renverser le régime, il leur suffit de faire condamner Kadhafi par la CPI pour crimes de guerre, aussi rapidement que possible et sans contre-enquête indépendante sur aucune des allégations de crime, lesquelles reposaient essentiellement sur des anticipations de massacres de civils [jamais commis]. Bien sûr, comme nous l’avons vu plus haut, concernant l’Irak, la CPI ne trouvait vraiment rien qui puisse justifier des poursuites contre l’occupant, dont les massacres de civils étaient de proportions autrement supérieures et avaient bel et bien été commis, et non simplement anticipés. En réalité, un vaste Tribunal International pour l’Irak a finalement été organisé afin de juger les crimes commis en Irak par les États-Unis et leurs alliés [le BRussell Tribunal], mais sur une base privée et avec un parti-pris clairement anti-belliciste. De fait, bien que ses séances se soient tenues très officiellement dans de nombreux pays et que de nombreuses personnalités importantes y soient venues témoigner, les médias n’y prêtèrent littéralement aucune attention. Ses dernières sessions et son rapport, rendu en juin 2005, ne furent même évoqués dans aucun grand média américain ou britannique.

La R2P correspond parfaitement à l’image d’un instrument au service d’une violence impériale exponentielle, qui voit les États-Unis et leur énorme complexe militaro-industriel engagés dans une guerre mondiale contre le terrorisme et menant plusieurs guerres de front, et l’OTAN, leur avatar, qui élargit sans cesse son « secteur d’activité » bien que son rôle supposé d’endiguement de l’Union Soviétique ait expiré de longue date. La R2P repose très commodément sur l’idée que, contrairement à ce qui était la priorité des rédacteurs de la Charte des Nations Unies, les menaces auxquelles le monde se trouve aujourd’hui confronté ne dérivent plus d’agressions transfrontalières comme c’était traditionnellement le cas, mais émanent des pays eux-mêmes. C’est parfaitement faux ! Dans son ouvrage Freeing the World to Death (Common Courage, 2005, Ch. 11 et 15), William Blum dresse une liste de 35 gouvernements renversés par les États-Unis entre 1945 et 2001 (sans même compter les conflits armés déclenchés par George W. Bush et Barak Obama).

Dans le monde réel, tandis que la R2P parait merveilleusement auréolée de bienveillance, elle ne peut être mise en œuvre qu’à la demande exclusive des principales puissances de l’OTAN et ne saurait donc être utilisée dans l’intérêt de victimes sans intérêt, à savoir celles de ces mêmes Grandes Puissances [ou de leurs alliés et clients] (Cf. Manufacturing Consent, Ch. 2 : « Worthy and Unworthy Victims »). Jamais on n’invoqua la R2P [ou quoi que ce soit de similaire] pour mettre fin aux exactions lorsque en 1975 l’Indonésie décida d’envahir et d’occuper durablement le Timor Oriental. Cette occupation allait pourtant se solder par plus de 200 000 morts sur une population de 800 000 au total – ce qui proportionnellement dépassait largement la quantité de victimes imputables à Pol Pot au Cambodge. Les États-Unis avaient donné leur feu vert à cette invasion, fourni les armes à l’occupant et lui offraient leur protection contre toute réaction de l’ONU. Dans ce cas précis, il y avait violation patente de la Charte des Nations Unies et le Timor avait impérativement besoin de protection. Mais dès lors que les États-Unis soutenaient l’agresseur, on n’entendrait jamais parler de réponse des Nations Unies. [Ndt : En tant que membre permanent du Conseil de Sécurité de l’ONU, les USA ont droit de veto sur toutes les décisions de l’ONU ; or toute décision d’intervention ou de sanction passe nécessairement par le Conseil de Sécurité]

Ce qui est réellement éloquent c’est de voir comment Evans gère ce passif notoire pour promouvoir la R2P. Interrogé à ce sujet lors d’une session de l’Assemblée Générale des Nations Unies sur la R2P, Evans en appelait au bon sens : La R2P « se définit d’elle-même », et les crimes mis en cause, y compris le nettoyage ethnique, sont tous intrinsèquement révoltants et par leur nature même d’une gravité qui exige une réponse […]. Il est réellement impossible de parler ici de chiffres précis ». Evans souligne que parfois, des chiffres minimes peuvent suffire : « Nous nous souvenons très clairement de l’horreur de Srebrenica… [8 000 morts seulement]. Avec ses 45 victimes au Kosovo en 1999, Racak suffisait-il à justifier la réponse qui fut déclenchée par la communauté internationale ? » En fait, l’événement de Racak avait effectivement paru suffisant pour une bonne et simple raison : il donnait un coup d’accélérateur au programme de démantèlement de la Yougoslavie d’ores et déjà lancé par l’OTAN. Mais Evans évite soigneusement de répondre à sa propre question au sujet de Racak. Inutile de dire qu’Evans ne s’est jamais demandé et n’a jamais cherché à expliquer pourquoi le Timor Oriental, avec plus de 200 000 morts n’avait jamais suscité aucune réaction de la communauté internationale ; et l’Irak pas davantage malgré [un million de morts dus aux sanctions, dont 500 000 enfants de moins de cinq ans] et plus d’un million supplémentaires suite à l’invasion. Les choix sont ici totalement politiques mais manifestement, Evans a si parfaitement intégré la perspective impériale qu’un aussi vertigineux écart ne le révolte pas le moins du monde. Mais ce qui est encore plus extraordinaire, c’est qu’un criminel de cette envergure avec un parti pris aussi évident puisse être considéré internationalement comme une autorité dans ce domaine et que des positions aussi ouvertement partiales que les siennes puissent être regardées avec respect.

Il est intéressant aussi de constater qu’Evans ne mentionne jamais Israël et la Palestine, où un nettoyage ethnique est activement mené depuis des décennies et ouvertement – comme en témoigne le très grand nombre de réfugiés aux quatre coins du monde. D’ailleurs, aucun autre membre de la pyramide du pouvoir ne considère la région israélo-palestinienne comme une zone révoltante où la nature et l’envergure des exactions commises exige une réponse de la « communauté internationale ». Pour obtenir le titre d’Ambassadeur des États-Unis auprès de l’ONU, Samantha Power jugea même nécessaire de se présenter très officiellement devant un groupe de citoyens américains pro-israéliens pour les assurer, les larmes aux yeux, de son profond regret pour avoir laissé entendre que l’AIPAC était une puissante organisation sur l’influence de laquelle il serait nécessaire de reprendre contrôle afin de pouvoir développer une politique à l’égard d’Israël et de la Palestine qui puisse œuvrer dans l’intérêt des États-Unis. Elle prêta même serment de rester dévouée à la sécurité nationale d’Israël. Manifestement, le monde devra attendre longtemps avant que Samantha Power et ses Parrains exigent que la R2P soit appliquée aussi au nettoyage ethnique de la Palestine.

En définitive, dans le monde post-soviétique, la structure internationale du pouvoir n’a fait qu’aggraver l’inégalité internationale, renforçant dans le même temps l’interventionnisme et la liberté d’agression des Grandes Puissances. L’accroissement du militarisme a certainement contribué à l’accroissement des inégalités mais il a surtout été conçu pour servir et favoriser la pacification, tant à l’étranger que dans nos propres pays. Dans un tel contexte, IH et R2P ne sont que des évolutions logiques qui apportent une justification morale à des actions qui scandaliseraient énormément de gens et qui, éclairées froidement, constituent des violations patentes du droit international. Présentant les guerres d’agressions sous un jour bienveillant, la R2P en est devenu un instrument indispensable. En réalité, c’est seulement un concept aussi frauduleux que cynique et anticonstitutionnel (anti-Charte des Nations Unies).

Edward S. Herman

Article original en anglais :

Humanitarian Bombs anthony freda“Responsibility to Protect” (R2P): An Instrument of Aggression. Bogus Doctrine Designed to Undermine the Foundations of International Law, 30 octobre 2013

Traduit de l’anglais par Dominique Arias

Edward S. Herman est Professeur Emérite de Finance à la Wharton School, Université de Pennsylvanie. Economiste et analyste des médias de renommée internationale, il est l’auteur de nombreux ouvrages dont : Corporate Control, Corporate Power (1981), Demonstration Elections (1984, avec Frank Brodhead), The Real Terror Network (1982), Triumph of the Market (1995), The Global Media (1997, avec Robert McChesney), The Myth of The Liberal Media: an Edward Herman Reader (1999) et Degraded Capability: The Media and the Kosovo Crisis (2000). Son ouvrage le plus connu, Manufacturing Consent (avec Noam Chomsky), paru en 1988, a été réédité 2002.

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Définitions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : r2p, responsabilité de protéger, onu, nations-unies, agression, politique internationale, droit international |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Elementos n°58: Critica de la sociedad de consumo

ELEMENTOS Nº 58. CRÍTICA DE LA SOCIEDAD DE CONSUMO: DE SIMMEL A BAUDRILLARD

Descargar con scribd.com

Descargar con docs.google.com

Descargar con pageflip-flap. com

Sumario

El fin del Pacto con el Diablo,

Teorías del consumo simbólico: del consumo estatutario al consumo identitario,

Simmel y la cultura del consumo,

Consumismo y sociedad: una visión crítica del homo consumens,

El Consumo como Cultura. El Imperio total de la Mercancía,

El Imperio del Consumo,

El consumo como signo en Baudrillard,

Thorstein Veblen y la tiranía del consumo,

Consumismo-Capitalismo, la nueva religión de masas del siglo XXI,

Del mundo del consumo al consumo-mundo. Lipovestky y las paradojas del consumismo,

La fábula del bazar. Orígenes de la cultura del consumo,

00:05 Publié dans Nouvelle Droite, Philosophie, Revue, Sociologie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : revue, nouvelle droite, sociologie, philosophie, société de consommation, consumérisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Pro-Russia-TV rencontre Yvan Blot

Pro-Russia-TV rencontre Yvan Blot

("Démocratie directe")

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Entretiens, Politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : démocratie directe, yvan blot, politique, france, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

L’ITALIE S’OUVRE ENFIN À LA DIVERSITÉ

L’ITALIE S’OUVRE ENFIN À LA DIVERSITÉ

Ex: http://dernieregerbe.hautetfort.com

L’Italie était un peu pâlichonne, ne trouvez-vous pas ? Cette population désespérément blanche, ces patronymes si uniformes avec leur terminaison en -i (parfois en -o ou en -a), ces grandes villes dépourvues d’enclaves africaines ou asiatiques, comme en France, en Grande-Bretagne ou en Allemagne… Mais tout cela est révolu, grâce au ciel. Depuis une bonne vingtaine d’années, la vieille Italie est enfin entrée dans le monde moderne, cosmopolite, métissé, riche de toutes ses différences. Comme dans les autres pays d’Europe, les grandes villes y ont maintenant leurs communautés étrangères, qui viennent apporter leur dynamisme, leur mobilité, leur altérité et surtout, chose infiniment précieuse, leur rapport différent au travail, à la propriété, à la citoyenneté. Jusqu’à présent, le plus visible de ces Italiens « issus de la diversité » était le pittoresque Mario Barwuah Balotelli, un foutebôleur éminemment sympathique et estimable, dont le comportement, sur le terrain ou en dehors, constitue un modèle pour la jeunesse. Ceux qui n’auraient pas suivi les frasques de ce joueur si habile dans l’art d’enfiler une chasuble en trouveront un résumé ici, qu’il faudrait compléter puisqu’il date de décembre 2011. Par exemple, il vient de se signaler à nouveau en offrant aux joueurs du Real Madrid une nuit d’amour avec sa copine : bel exemple de cet art du partage par lequel les populations sub-sahariennes viennent renouveler notre conception archaïque et sclérosée des rapports entre l’homme et la femme.

Cependant Balotelli était un peu le baobab qui cachait une forêt transalpine encore très monocolore, quasiment menacée d’extinction par excès de consanguinité. Qu’on se rassure ! L’Italie a décidé de prendre son destin en mains, d’assumer résolument son bariolage naissant et de se donner les moyens d’accroître celui-ci. Pour la première fois, une négresse a été nommée ministre : Cécile Kashetu Kyenge, originaire du Congo-Kinshasa, vient de recevoir le portefeuille de l’Intégration dans le nouveau gouvernement italien.

D’une autre manière que Balotelli, Mme Kashetu Kyenge apporte avec elle une conception renouvelée du couple. En effet, son père, quoique catholique, est polygame, marié à quatre femmes et père de pas moins de 38 enfants. Or la nouvelle ministresse est loin de réprouver la polygamie, ayant tiré un grand profit de son enfance au milieu de ses 37 germains consanguins : « Grandir avec tant de frères et sœurs m’a donné l’impression de vivre dans une communauté. Cela facilite les relations avec l’autre partie de la société, en dehors de la famille ». On s’en réjouit pour elle, et on applaudit un tel franc-parler. Au moment où la France vient de légaliser le mariage homosexuel, il est nécessaire que des voix autorisées se fassent entendre pour accélérer l’inéluctable étape suivante, celle du mariage polygamique.

Mais le plus merveilleux dans cette nomination inédite, c’est que Mme Kashetu Kyenge n’entend nullement rester une exception sans lendemain. Bien au contraire, elle a d’emblée annoncé… la couleur : elle va tout faire pour que des millions d’Africains viennent apporter leur sang neuf à l’Italie moribonde (où elle-même est arrivée à l’âge de 19 ans), de façon que son exemple soit suivi massivement. C’est que Mme Kashetu Kyenge n’est pas du genre à mettre son identité dans sa poche, à singer les Italiens de souche et à tenir un discours assimilationniste aux évidents relents fachistes, comme une Malika Sorel ou un Éric Zemmour chez nous. Elle a même pris le risque de choquer les Italiens en déclarant qu’elle ne se sentait pas italienne à 100%, mais plutôt italo-congolaise : magnifique exemple de cette identité plurielle devenue si courante, et qui devrait même être la norme. Qu’on ne croie pas cependant que cette demi-italianisation l’aurait amenée à demi-renier sa négritude. Tout au contraire : « Je ne suis pas une femme de couleur, je suis noire, c’est important de le dire, et je le répète avec fierté. Nous devons faire tomber ces murs : ne pas connaître l’autre rend méfiant et augmente les discriminations. L’immigration est une richesse, les différences une ressource ». Et cette fierté noire va se traduire en actes. Un sommaire article du Figaro nous permet d’en savoir un peu plus sur ses idées et ses projets. Déjà première Africaine à siéger au Parlement italien, elle était en train de préparer un rapport sur le racisme institutionnel dans son pays d’accueil. Un énorme pavé, sans doute ! Consciente, j’imagine, que l’Italie souffre d’un taux de chômage beaucoup trop bas qui pénalise les entreprises (les obligeant à recruter n’importe qui à des salaires exorbitants), elle souhaite rendre le marché du travail plus accessible aux étrangers : excellente idée, qui permettra de combler l’excédent d’offre d’emplois. Peut-être même y aura-t-il alors, à l’inverse, un peu trop de demandeurs d’emploi : mais qu’importe, puisque les ressources pléthoriques de la péninsule permettent de subvenir largement aux besoins des chômeurs, lesquels jouent du reste un rôle notable dans la bonne santé du pays, notamment en augmentant les taux d’audience des chaînes de télévision ou en dynamisant la vie urbaine.

Mieux encore : Mme Kashetu Kyenge milite pour l'abrogation du délit d'immigration clandestine (et pour cause : elle a elle-même avoué être entrée en Italie de façon irrégulière). Voilà une idée magnifique, dont on se demande bien pourquoi elle n’est pas brandie par tous les partis en France. Il est évident que dans notre monde enfin ouvert et cosmopolite, les États-Nations, ces inventions criminelles, sont des archaïsmes caducs qu’il convient de dissoudre d’en haut et de démanteler d’en bas. Il y a une seule humanité sur une seule planète : donc tout homme doit pouvoir aller et venir à sa guise, et s’installer où il veut quand il veut. Les migrations sont saines, utiles, nécessaires : autorisons-les sans aucune restriction ! En outre, les multiples prestations sociales (éducation, santé, logement, etc) qu’il faudra bien fournir, même à ceux qui n’apporteront rien d’autre que leur souriante présence, seront une bien maigre compensation (mais ô combien légitime et nécessaire) aux irréparables dommages que le colonialisme a infligés à leurs ancêtres.

Mais ce n’est pas suffisant. À quoi bon permettre à quiconque de venir vivre en Italie, si c’est pour y être l’objet de discriminations permanentes ? Il convient donc de faire en sorte que les immigrés puissent le plus vite possible être considérés comme des Italiens à part entière. Aussi Mme Kashetu Kyenge fait-elle du droit du sol sa priorité : « Je rencontrerai probablement des résistances, nous devrons beaucoup travailler pour y arriver », a-t-elle reconnu alors que la citoyenneté italienne est basée sur le droit du sang (le droit du sang ! Pourquoi pas la pureté de la race ? On sent l’héritage fachiste). « Un enfant, fils d'immigrés, qui est né ici et qui se forme ici doit être un citoyen italien », a-t-elle expliqué, avec autant de bon sens que de cohérence.

Pour autant, elle ne sous-estime pas la radicalité des transformations qu’elle va provoquer : « C'est un pas décisif pour changer concrètement l'Italie ». Mais vivre, c’est changer, n’est-ce pas ? Ce pays avait un côté moisi et sclérosé qui faisait honte à toute l’Europe. Il doit assumer sa vocation pluriethnique et multiculturelle : l’entrée dans la modernité est à ce prix, la vraie modernité, diverse et métissée. C’est bien ce qu’a déclaré le nouveau chef du gouvernement, M. Enrico Letta, se réjouissant de ce choix qui « démontre avec cohérence le fait de croire à une Italie plus intégratrice et vraiment multiculturelle ». Et bien entendu, la lutte contre le racisme ne se distingue pas de la lutte contre toutes les autres discriminations : pour Cécile Kashetu Kyenge, il est également nécessaire de « lutter contre la violence sexiste, raciste, homophobe et de toute autre nature ». Il s’agit d’extirper le virus de l’intolérance du corps et du cerveau de l’Italien moyen. S’il récalcitre, il faudra bien l’opérer de force.

Et cependant je crains que l’opération soit longue et difficile. La nomination de Mme Kyenge a été accueillie par les plus honteuses injures racistes, preuve que le ventre de la bête immonde est toujours fécond. Les ignobles cris de singes, qui polluent si souvent les stades italiens quand des athlètes kémites viennent y déployer leur puissance, nous rappellent les heures les plus sombres de notre histoire, et l’Italie en compte plus qu’on croit, de ces heures sombres : il n’est malheureusement que trop facile de trouver des pages d’infamie, quand on se penche sur la littérature italienne ou latine.

Je songe par exemple à Juvénal (environ 45-128 ap. JC), oui, ce Juvénal salué fraternellement par Hugo : « Retournons à l'école, ô mon vieux Juvénal. / Homme d'ivoire et d'or, descends du tribunal / Où depuis deux mille ans tes vers superbes tonnent... » (Châtiments, VI, 13), mais il est vrai que Hugo était lui-même un raciste patenté, comme le prouve son inqualifiable discours sur l’Afrique du 18 mai 1879. C’est peut-être pour cela qu’il se sentait si proche de Juvénal, ce pseudo-poète atrabilaire et enflé, parangon d’esprit réactionnaire, misogyne (sa satire VI est tout entière un déchaînement de haine contre les femmes) et homophobe (voir notamment les satires II, VI et IX), mais surtout antisémite et xénophobe comme pas deux. Pour l’antisémitisme, on peut lire cet article de Sylvie Laigneau-Fontaine, une universitaire dijonnaise, paru dans la Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire, 2006, n°84-1, p. 45-57. Elle conclut ainsi : « La conversion de citoyens romains au judaïsme est, pour Juvénal, la preuve manifeste de l’aliénation décadente de la société romaine. C’est pourquoi il se fait antisémite virulent et trace du Juif, dans ses Satires, une image grotesque, méprisable et inquiétante ». Pour le racisme et la xénophobie, on retiendra telle ou telle saillie lâchée ici ou là (« un Éthiopien basané, porte-poisse à ne jamais croiser le matin ! » satire VI, v. 600-601), plus encore la satire XV, où il répand les pires calomnies contre les Égyptiens (qu’il traite de cannibales), et en priorité la satire III, écrite vers 87, qui serait à citer presque intégralement. Je me contenterai de quelques extraits, en priant les enfants et les esprits sensibles de ne pas poursuivre la lecture, car il s’agit d’un texte immonde. Publié aujourd’hui, il tomberait immanquablement sous le coup des justes lois qui limitent la licence d’expression et proscrivent les propos scandaleux, car on ne peut pas tolérer une telle critique des étrangers :

« Puisque les états honorables n’ont plus leur place à la Ville, que le travail n’y paie pas, que ce qui valait hier quelque chose vaut aujourd’hui bien moins et demain moins que rien, j’ai décidé de m’en aller là-bas où Dédale épuisé déposa ses ailes. […] Qu’ils fassent leur vie ici, les Artorius et les Catulus, qu’ils y restent ceux qui font du blanc avec du noir, ceux qui sont doués pour soumissionner les temples, les fleuves, les ports, la vidange des égouts, l’incinération des cadavres, et pour vendre à l’encan de l’esclave sur pied ! Ils étaient sonneurs de cor aux arènes, pète-joues fameux dans les fanfares de cirque. Les spectacles maintenant c’est eux qui les financent, eux qui, bien démagogiquement, quand le public renverse le pouce pour commander un cadavre, ordonnent la mise à mort avant de s’en retourner prendre la ferme des chiottes publiques. Pourquoi pas ? Pourquoi le hasard ne propulserait-il pas cette racaille du ras du sol aux plus hautes cimes des affaires, puisque tout peut arriver quand il a décidé de faire une farce ? […] Ceux que je fuis d’abord, la race la mieux en cour aujourd’hui dans nos milieux friqués, je vais vite vous l’avouer sans vergogne, vieux Romains : je ne peux pas supporter une Ville grecque. Et encore, quel pourcentage d’Achéens dans cette bouillasse ? Il y a belle lurette que l’Oronte s’est épandu de la Syrie jusqu’au Tibre, charriant avec lui langue, mœurs, gratteurs de harpe et joueurs de flûte, sans oublier les tambourins folkloriques et les filles envoyées à tapiner le long du cirque. Allez-y donc, les amateurs de louvettes orientales à mitres peinturlurées ! Ô Romulus ! Voilà ton péquenaud qui enfile des trechedipnas et porte une batterie de niketerias à son cou keromatisé ! Mais ce paysan-là est de Sicyone-le-Haut, celui-ci a quitté Amydonas, celui-ci Andros, celui-là Samos, celui-ci vient de Tralles ou bien d’Alabanda se jeter sur l’Esquilin et le Viminal où poussait l’osier, et bientôt se greffer sur nos grandes familles et les dominer. Comprenant au quart de tour, toupet éperdu, un discours toujours prêt, plus baratineur qu’Isée, devine qui c’est ! C’est qui tu veux, c’est l’homme-orchestre : grammairien, rhéteur, géomètre, peintre, masseur, voyant, acrobate, médecin, sorcier, il sait tout faire le petit Grécoulos crève-la-faim. Au ciel, tu le lui commandes, il y monte ! Finalement ce n’était ni un Maure ni un Sarmate ni un Thrace celui qui se mit des plumes au dos, c’était un natif d’Athènes ! Et moi je ne fuirais pas ces gens-là et leur pourpre ? Il signera avant moi, il se calera à table sur un meilleur coussin, un Syrien poussé à Rome par le vent avec une cargaison de prunes et de figues ? Alors au total ça vaut zéro que notre enfance ait bu la pluie du ciel aventin et ait été nourrie à l’olive sabine ? […] Non, nous ne sommes pas à égalité. Il gagne forcément celui qui est capable une fois pour toutes de composer jour et nuit son expression d’après la figure d’un autre, toujours prêt à crier bravo et à envoyer des baisers si "l’ami" a bien fait son rot, s’il a pissé droit, si le pot de chambre à bascule tout en or a claqué comme il faut. Et avec ça rien de sacré, rien à l’abri de sa queue, pas plus la maîtresse de maison que la fille vierge, le fiancé encore imberbe ou le fils toujours puceau. Faute de mieux c’est la grand-mère qui y passe ! […] Pas de place pour le Romain là où règne un Protogénès, un Diphilus ou un Hermarchus. C’est un vice de race : il ne partage jamais un "ami". Il le possède seul. Dès qu’il a craché dans une oreille influençable la plus impalpable goutte de son venin naturel et atavique, me voilà à la porte, c’est comme si mes longues années de service n’avaient jamais existé. Nulle part, on ne jette un client aussi facilement qu’ici. » [1].

Et il y en a comme ça sur douze pages (322 vers) ! Juvénal stigmatise avec une virulence insoutenable l’hypocrisie de ces immigrés, de fieffés bonimenteurs capables de débiter n’importe quoi à n’importe qui ; l’inégalité de la société romaine, qui humilie en permanence les pauvres au profit d’une caste de privilégiés égoïstes ; la corruption généralisée, qui permet de bâtir de vastes fortunes de façon malhonnête ; la cherté de la vie dans la capitale, qui en éloigne la classe moyenne ; l’irresponsabilité des promoteurs immobiliers, qui laissent à l’abandon des bâtiments fragiles et insalubres, etc. On croirait lire un texte contemporain ! Il est patent qu’à plus de dix-neuf siècles d’intervalle, ce sont toujours les mêmes rengaines antimodernistes, les mêmes jérémiades contre le progrès, les mêmes pleurnicheries contre ceux qui réussissent, qui apportent du sang neuf, qui créent un monde nouveau. Juvénal fait partie de ces aigris qui n’ont pas su s’adapter au cours des choses et qui exhalent leur dépit en se réfugiant dans le mythe d’un passé idéalisé où tout était forcément plus heureux. Et comme d’habitude, le bouc-émissaire à leurs malheurs est tout trouvé : l’étranger, l’étranger forcément coupable de tous les maux, l’étranger forcément malhonnête, dégénéré, subversif. Que dirait-il aujourd’hui, ce triste taré, s’il contemplait la joyeuse Italie bigarrée qui émerge ! On peut en avoir une idée si on a le courage d’ouvrir (en se bouchant le nez) les torchons putrides de nos Jean Raspail et nos Renaud Camus, dont on voit qu’ils n’ont rien inventé. Gageons que notre monde connaîtra le même glorieux destin que le monde romain dans les siècles qui ont suivi celui de Juvénal. D’ailleurs nos chers musulmans sont en train de le transformer comme les chrétiens ont su transformer la romanité, exsangue, décatie, épuisée. En attendant, l’analogie entre l’infâme Juvénal et les salopards d’extrême-droite est flagrante : un jeune étudiant suisse, M. Louis Noël, a su établir un parallèle saisissant entre son discours fétide et celui de l’UDC, le parti des néo-nazis helvétiques. Son mémoire, présenté en 2010, est consultable sur le net [2]. Vivement que les cours de justice internationale viennent interdire ces groupuscules abjects, et souhaitons que Mme Kashetu Kyenge puisse purger l’Italie des remugles racistes qui la polluent depuis deux-mille ans.

Je songe à Claudien (370-408), pseudo-poète décadent, dont l’œuvre sombra dans un oubli mérité en même temps que cet empire odieux qui trépassa comme il le devait, faute d’avoir su faire leur juste place aux migrants prétendus « barbares » qui venaient le régénérer en l’enrichissant de leurs différences. Dans sa Guerre contre Gildon, il dresse un tableau apocalyptique du Maghrèbe pendant la sécession de Gildon (ce prince maure et général romain se révolta en 397-398 contre Rome, l’empereur Honorius et le régent Stilicon. Bien qu'il fût soutenu par la cour de Constantinople (l'empereur Arcadius et le chambellan Eutrope), il fut vaincu par son propre frère Mascezel : trop souvent, hélas, les colonisés sont victimes de leurs propres querelles internes, qui profitent au conquérant. Il est vrai que, quelque vingt-cinq ans plutôt, Gildon avait lui-même vaincu, au service de Rome, son frère Firmus, auteur d’une première rébellion contre l’oppression impérialiste). Voici un extrait des hallucinations nauséabondes de Claudien. Il s’agit d’une prosopopée par laquelle l’Afrique allégorisée, s’adressant à Jupiter, gémit des outrages que lui inflige Gildon (l’artifice du procédé va de pair avec la fausseté du contenu) :

« Il oblige les veuves à se mêler au cortège de ses serviteurs à la chevelure frisée et des jeunes gens à la voix mélodieuse, et à sourire, quand leurs maris viennent d’être égorgés. […] Mais ces outrages faits à la pudeur ne lui suffisent pas. Les femmes les plus nobles, quand il en est las, sont livrées aux Maures : au milieu de leur ville, on prend les mères carthaginoises, pour les marier de force à des barbares. Le tyran nous impose un Éthiopien pour gendre, un Nasamon pour époux : l’enfant, d’une autre couleur que sa mère, est l’effroi de son berceau. […] Il arrache les citoyens au foyer de leurs ancêtres, il chasse les paysans de leurs vieux domaines. Exilés et dispersés ! le retour leur est-il à jamais interdit, et ne pourrai-je rendre à leur patrie mes citoyens errants ? » [3].

On ne peut lire sans dégoût un tel tissu de calomnies racistes et d’hostilité bornée au sain brassage des populations. Comment cet imbécile croit-il que les nations se renouvellent, sinon par le métissage culturel et ethnique, donc par des unions mixtes et des déménagements ? Le vers 193 est le plus atroce : « l’enfant, d’une autre couleur que sa mère, est l’effroi de son berceau », ce qu’on peut exprimer encore plus littéralement, pour coller à la concision du latin : le nourrisson d’une autre couleur épouvante son berceau (« Exterret cunabula discolor infans » : on pourrait traduire « discolor » par « hétérochrome », mais ce serait trop pédant). Voilà le préjugé raciste dans toute son abomination. Faut-il être perverti par des idéologies morbides pour ne pas se réjouir d’avoir un enfant d’une autre couleur que la sienne ! Qu’est-ce que Claudien, cette hyène fachiste, dirait s’il voyait l’Italie actuelle ? On n’ose pas l’imaginer. Heureusement la civilisation a fait des progrès, les mentalités se sont adaptées, et on ne peut plus, aujourd’hui, garder les idées périmées d’autrefois. Qui, aujourd’hui, ne se réjouirait pas d’avoir un métis pour enfant, un nègre pour gendre ou un arabe pour époux ? (et je ne parle pas seulement des femmes…).

Je songe à Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), poète bien surfait qu’on ne devrait plus faire lire dans les classes que dans des éditions expurgées ad usum Delphini, tant il déploie dans ses œuvres les pires insanités homophobes, racistes, antisémites et islamophobes. Pour ce dernier point, mentionnons que Saladin, ce héros, Averroès et Avicenne, ces génies, sont placés en Enfer dans la Divine Comédie (chant IV), et surtout que Mahomet et son gendre Ali y sont atrocément châtiés dans la neuvième fosse du huitième cercle de l’Enfer :

« Les uns montrant leurs membres transpercés,

D’autres, tronqués : rien ne pourrait atteindre

À la hideur de la neuvième fosse.

Jamais tonneau fuyant par sa barre ou sa douve

Ne fut troué comme je vis une ombre,

Ouverte du menton jusqu’au trou qui pète.

Les boyaux lui pendaient entre les jambes ;

On voyait les poumons, et le sac affreux

Qui change en merde ce que l’homme avale.

Tandis que tout entier je m’attache à le voir,

Lui, m’avisant, s’ouvre des mains la poitrine

Et dit : "Regarde donc : je me déchire !

Vois Mahomet comme il est mutilé !

Et Ali devant moi s’en va pleurant,

La face fendue de la houppe au menton.

Et tous les autres que tu vois ici

Vécurent en semant scandale et schisme :

C’est pour cela qu’ils sont ainsi fendus.

Un diable est là derrière qui nous schismatise

Cruellement au fil de son épée,

Puis nous remet chacun dans cette file,

Quand nous avons bouclé le triste tour :

Car toutes nos blessures sont déjà refermées

Avant que nous repassions devant lui" ». [4]

Texte horrible et infernal en effet, mais non comme Dante le croyait : par l’intolérance haineuse qu’il manifeste bien plutôt, et l’atteinte sacrilège qu’il porte à la sainte personne du Prophète. On comprend que l’association droidlomiste Gherush92 s’en soit scandalisée. Par la voix de sa présidente Valentina Sereni, elle a eu raison de braver les sarcasmes italianocentristes en réclamant que Dante soit exclu des programmes scolaires et universitaires, retiré des établissements d’enseignement secondaire, et dûment republié avec des avertissements explicatifs, comme Mein Kampf. Ces courageux militants de la tolérance, pour qui la viande cascher et hallal constitue un droit de l’homme, osent appuyer là où ça fait mal, en pointant la haine de l’autre qui constitue le fondement de la culture italienne : « La poursuite d’enseignements de ce genre constitue une violation des droits de l’homme et met en évidence la nature raciste et antisémite de l’Italie, dont le christianisme constitue l’âme. Les persécutions anti-juives sont la conséquence de l’antisémitisme chrétien qui a ses fondements dans les Évangiles et dans les œuvres qui s’en inspirent, comme la Divine Comédie. […] Certainement, la Divine Comédie a inspiré les Protocoles des Sages de Sion, les lois raciales et la solution finale ». Oui, Dante et le Nouveau Testament sont à l’origine de la Choa, il faut avoir le courage de le dire ! L’Italie doit se regarder en face et cesser de s’exonérer lâchement de son écrasante responsabilité dans la genèse d’Auschwitz. Gherush92 ne manque pas d’idées judicieuses, qui mériteraient d’être reprises et amplifiées dans toute l’Europe : « L’antisémitisme, l’islamophobie, la haine anti-Roms, le racisme doivent être combattus en recherchant une alliance entre les victimes historiques du racisme, précisément sur des thèmes et des sujets qu’ils puissent partager, comme la diversité culturelle ». Une alliance entre les victimes historiques du racisme… voilà quelque chose à creuser ! Une coalition des Juifs, des Noirs, des Arabes, des Amérindiens, des Asiatiques, des Roms, tous ligués contre l’Occident blanc pour lui faire rendre gorge, pour lui arracher toutes ses griffes, pour le guérir à jamais de son venin de haine et d’intolérance, pour lui imposer définitivement cette diversité et ce bariolage qu’il refuse de toute son âme… Il faudra sans doute en venir là un jour, s’il refuse de se transformer de lui-même.

Je songe à Cesare Lombroso (1835-1909), ce pseudo-savant aux thèses répugnantes, scientiste fou qui a passé sa vie à traquer le gène du crime, collectionneur et mesureur de crânes humains comme Vacher de Lapouge, obsédé d’atavisme et de dégénérescence sociale, propagandiste de l’eugénisme, parfait représentant de cette pseudo-science ultra-déterministe du XIXème siècle qui a inventé le délire raciologique et se trouve donc à l’origine directe des cauchemars génocidaires du XXème. Heureusement, il existe encore en ce monde des êtres dotés de mémoire, désireux que les infamies de nos ancêtres ne soient pas offertes à l’admiration des nouvelles générations, et qui, pour cette raison, mènent une action courageuse et inlassable en faveur d’une censure très vigilante du legs du passé, selon les dernières normes du moralement et politiquement correct. C’est ainsi qu’une campagne a été lancée en 2010 pour que la municipalité de Milan débaptise la via Cesare Lombroso, cet affront aux droits de l’homme : on lira ici le texte de leur accablant réquisitoire (en anglais).

En France, une telle épuration a déjà été menée avec succès : ainsi, à Lyon, la faculté de médecine Alexis-Carrel (eugéniste crypto-nazi) a été rebaptisée R.T.H. Laennec en 1996. La plupart des rues portant le nom de ce sinistre individu ont aussi changé de nom ; par exemple à Saint-Brieuc, la rue Alexis Carrel est devenue rue Anne Frank : une petite juive néerlandaise, qui scribouillait ses fantasmes d’adolescente sur des cahiers d’écolier, à la place d’un prix Nobel français aux idées nauséabondes : voilà un exemple à généraliser ! Puissent toutes nos rues, portant le nom d’un auteur qui a écrit ne serait-ce qu’une phrase incorrecte, se voir vite attribuer, à la place, le nom d’un martyr du droidlomisme ou d’un représentant de nos chères minorités visibles !

Je songe à Oriana Fallaci (1929-2006), cette pseudo-journaliste qui acheva sa triste carrière au service de l’impérialisme occidental en révélant son hideux visage raciste et islamophobe. Après le 11 septembre 2001, elle disjoncta complètement, à moins que ce ne fussent l’âge et bientôt la maladie qui l’eussent persuadée d’ôter le masque hypocrite qui lui avait acquis une réputation plus ou moins honorable. Elle publia deux pamphlets ignobles, La Rage et l’orgueil (Plon, 2002) et La Force de la raison (Rocher, 2004), qui furent poursuivis en justice dans plusieurs pays, tant ils exhalent les miasmes les plus putrides. Elle y étale en effet son aversion rabique de l’islam, dont elle prétend qu’il « sème la haine à la place de l'amour et l'esclavage à la place de la liberté » (alors que c’est évidemment tout l’inverse). Sous sa plume en délire, les injures les plus répugnantes se donnent libre cours : « Au lieu de contribuer au progrès de l’humanité, [les fils d'Allah] passent leur temps avec le derrière en l'air à prier cinq fois par jour » (agression vulgaire, d’autant plus monstrueuse que, comme on le sait, l’islam est une religion de paix et de lumières, qui ennoblit ses adeptes et améliore la civilisation, partout où la Providence la répand en lui ouvrant les cœurs). Forcément, Mme Fallaci assimile tout musulman à un fanatique prêt à tout faire sauter : « les mosquées grouillent jusqu'à la nausée de terroristes ou aspirants terroristes » (elle fait semblant d'ignorer que les attentats terroristes ne sont qu'une légitime réplique aux agressions incessantes dont les monstrueuses puissances coloniales et leur allié sioniste accablent les peuples arabes, sans parler du martyre permanent du peuple palestinien dont les enfants meurent chaque jour sous les balles de Tsahal quand ce n'est pas de faim, de soif ou de désespoir). Mais ce qui est encore plus atroce, c’est qu’elle ne se contente pas de critiquer une religion dont la grandeur passe au-dessus de son entendement borné : elle avoue sans vergogne la répugnance physique que lui inspirent les Arabes, nos indomptables frères orientaux. « Il y a quelque chose, dans les hommes arabes, qui dégoûte les femmes de bon goût », ose-t-elle écrire, toute honte bue, révélant par là, n’en doutons pas, sa frustration sexuelle de femme qui n’a jamais été épanouie par la sauvage virilité des fils du désert, laquelle a pourtant l’art de contenter, depuis des siècles, les ânes, les chèvres et les chameaux les plus insatiables. Conséquence inévitable : possédée par la fièvre obsidionale, elle voit l’Europe comme une citadelle assiégée, que dis-je, comme une contrée envahie, bientôt transformée en partie intégrante de l’oumma. Pour elle, les Arabes submergent l'Europe sous couvert de migrations pour propager l'islam, et comme ils « se multiplient comme des rats » (notez l’animalisation de l’étranger), il en résulte que « l'Europe est devenue chaque jour davantage une province de l'Islam, une colonie de l'Islam ». Même si elle était encore de ce monde, il serait sans doute vain de lui faire observer que non seulement une telle perspective est loin d’être à l’ordre du jour (puisque nos communautés étrangères s’intègrent harmonieusement dans notre société multiculturelle), mais que si elle devait advenir, elle ne pourrait être que hautement profitable à tout le monde, et d’abord à l’Europe : quel pays n’a-t-il pas été merveilleusement embelli, enrichi et bonifié, dès lors qu’il est devenu à majorité musulmane ? Les bénéfices culturels, spirituels, scientifiques, économiques, sociaux d'une telle évolution seraient tout simplement prodigieux. En outre, comme l’a dit un jour Jaques Chirac, « les racines de l’Europe sont autant musulmanes que chrétiennes » (Figaro, 29 octobre 2003) : dès lors, l’islamisation intégrale ne serait qu’un retour aux sources. Et puis, de toute façon, la vie, c’est le changement, n’est-ce pas ? Tout organisme qui n’évolue pas se sclérose et meurt. Cela fait vingt siècles que nous sommes chrétiens, il est temps de passer à autre chose.

Le plus intéressant, dans le cas pathologique de Mme Fallaci, c’est qu’elle nous montre que cette prétendue hostilité intellectuelle à l’islam, que d’aucuns voudraient nous faire passer pour l’application d’un esprit critique hérité des Lumières, devant être protégé coûte que coûte par le droit de libre expression, – n’est en réalité que l’envers du racisme le plus abominable. Mme Fallaci, cette dégénérée, triste reflet d’une Italie d’hier qu’il faut faire disparaître à jamais, confond dans sa haine bestiale les Arabes et les musulmans. Étrangers à physionomie, couleur de peau, odeur différentes de la sienne, ou croyants professant une foi différente de la sienne : pour elle, c’est tout un, ce ne sont que deux incarnations d’un même Autre qu’elle refuse de côtoyer, qu’elle refuse de considérer comme un semblable, qu’elle refuse d’accueillir dans sa cité monocolore et consanguine. Ce rejet de l’étranger est la quintessence du racisme, et c’est ce comportement odieux qu’il convient de bannir et d'éliminer à jamais. Qu’est-ce que le projet ultime du droidlomisme, sinon l’édification d’un monde où tous les pays ayant été remplis d’étrangers, il n’y ait plus aucun étranger nulle part ? Une planète, une humanité, une nation, une culture, une langue, un drapeau : généraliser la différence jusqu’à ce qu’elle se confonde avec l’identité.

Et je songe à bien d’autres encore, tant est longue la liste du déshonneur italien !... On le voit, toute la culture italienne, parce qu’elle est catholique, est foncièrement raciste, et ce n’est pas exagérer que de n’y voir qu’une énorme déclaration de guerre contre les non-catholiques, contre les non-Italiens, contre les non-mâles blancs hétérosexuels. Mme Cécile Kashetu Kyenge a un énorme travail devant elle, une montagne de préjugés à renverser, vingt siècles de culture à dissoudre. Heureusement, son combat va dans le sens de l’Histoire, car elle lutte pour le Vrai, le Bien et le Beau. Tous les hommes de bonne volonté sont avec elle, et seuls les sales fachos, proclamés ou honteux, peuvent la critiquer. Cette triste engeance n’est composée que d’imbéciles, de malades, d’aigris et de ratés. Comment peut-on ne pas avoir de la sympathie pour les nègres ? Comment peut-on ne pas avoir d’attirance pour l’étranger ? Comment peut-on ne pas trépigner d’enthousiasme devant cette Europe nouvelle, métissée, multicolore, multiculturelle qui naît sous nos yeux ? On se le demande…

Note:

[1] Vers 21-25 ; 29-40 ; 58-85 ; 104-113 ; 119-125. J’ai repris la traduction d’Oliviers Sers (Les Belles-Lettres, 2002, coll. classiques en poche n°61) en l’amendant très légèrement. Artorius et Catulus sont deux affranchis célèbres, c’est-à-dire des anciens esclaves émancipés, sans doute d’origine étrangère, qui ont pris le nom de leur maître et ont acquis une immense fortune dans des métiers vils, au début du premier siècle. On a compris que les Grecs dont se plaint Juvénal ne sont pas forcément de purs Hellènes de l’Attique ou du Péloponnèse : après quatre siècles d’hellénisation du bassin oriental de la Méditerranée, un bon nombre d’Orientaux pouvaient se faire passer pour des Grecs aux yeux des Romains (qui eux-mêmes n’étaient plus depuis longtemps de purs Latins du Latium). Tralles et Alabanda sont dailleurs des villes d’Asie mineure.

[2] Je suis ahuri par la qualité de ce travail scolaire, qui me paraît correspondre à un honorable mémoire de master français (soit bac+4). Or, si j’ai bien compris le système scolaire suisse, ce « travail de maturité », provenant du Gymnase Auguste Piccard de Lausanne, date de la dernière année de l’enseignement secondaire, soit l’équivalent de notre année de terminale, et même à cheval sur la 1ère et la Tle puisque réalisé entre février et novembre. L’auteur a donc 17-18 ans ! On trouvera sur cette page d’autres mémoires effectués par des condisciples de Louis Noël, la même année. Quiconque connaît les daubes lamentables qu’un groupe de lycéens d’ici peut produire, en guise de « T.P.E. », ne peut manquer d’être pris de vertige devant l’écart de niveau entre le système français et le système suisse. C’est comme si une équipe de troisième division se voyait brusquement confrontée à une équipe habituée aux huitièmes de finale de la Ligue des champions ! Ou bien ce Gymnase Auguste Piccard est un établissement d’élite, qui ne peut se comparer qu’aux meilleures classes des vingt meilleurs lycées français ? Si ce n'est qu'un établissement ordinaire, alors l'arriération mentale de la jeunesse française dépasse nos pires cauchemars…

[3] Vers 183-186 ; 188-193 ; 197-200. J’ai repris la traduction de Victor Crépin (Claudien, Œuvres complètes, Garnier, 1933, tome premier, page 195), en la corrigeant parfois avec l’aide de la traduction de la collection Nisard (Dubochet et Cie, 1837, rééd. Firmin-Didot, 1871) qu’on trouve notamment sur l’indispensable site de Philippe Remacle ou sur Gallica. Désiré Nisard avait paresseusement repris la traduction de l’abbé Guillaume-Jean-François Souquet de La Tour (1768-1850), futur curé de Saint-Thomas d’Aquin, qui date de 1798, et qui se soucie plus d’élégance que de fidélité. Celle de V. Crépin m’a paru à la fois plus précise et plus expressive, sauf pour le vers 193, qu’il traduit lourdement ainsi : « et les enfants qui naissent ainsi de parents différents de couleur apportent l’épouvante dans leurs berceaux ». — Les Nasamons étaient un peuple libyque nomade, vivant au sud de Syrte.

[4] Chant XXVIII, vers 19-42. J’ai repris la traduction de Marc Scialom (Pochothèque, 1996, pages 710-711), que j’ai corrigée avec l’aide de celle de Jacqueline Risset (Flammarion, 1985, pages 254-257).

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : diversité, multiculturalisme, société multiculturelle, immigration, italie, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 21 novembre 2013

Le tireur fou est un Arabe d’extrême-gauche

L’algérien Abdelhakim Dekhar, le tireur présumé du quotidien Libération, a été placé en garde à vue mercredi soir, confondu par son ADN.

La police et les médias s’étaient donc un peu emballés en évoquant jusqu’à présent, et avec insistance, un « homme de type européen »…

C’était la même chose avec les meurtres de Mohamed Merah, dont l’extrême-droite avait même été imprudemment chargée…

Il faudra encore attendre pour avoir un Breivik français !

Sinon, on peut relever que cet Abdelhakim Dekhar, figure de l’extrême-gauche des années 90, a été impliqué dans l’affaire Rey-Maupin : une fusillade au cours de laquelle cinq personnes dont trois policiers ont été tuées en 1994. Bien que présenté comme le mentor du duo meurtrier d’alors, et ayant acheté le fusil à pompe utilisé pour les meurtres, il n’écopa que de… 4 ans de prison.

12:04 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : paris, france, europe, affaires européennes, tireur fou |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Elementos n°59 y 60: Juan Donoso Cortés

ELEMENTOS Nº 60. DONOSO CORTÉS: DECISIÓN, REACCIÓN Y CONTRARREVOLUCIÓN (Vol. II)

ELEMENTOS Nº 59. DONOSO CORTÉS: DECISIÓN, REACCIÓN Y CONTRARREVOLUCIÓN (Vol. I)

Descargar con scribd.com

Descargar con pageflip-flap.com

Descargar con google.com

Sumario

00:05 Publié dans Nouvelle Droite, Revue, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : réaction, théorie politique, sciences politiques, politologie, philosophie, juan donoso cortés, nouvelle droite, espagne, 19ème siècle |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Pietro Barcellona: il potere della parola e l'illusoria strategia dei diritti

di Alessandro Lattarulo

Ex: http://www.ariannaeditrice.it

È arduo cercare di sintetizzare il pensiero di Pietro Barcellona, recentemente scomparso, anche semplicemente mossi dalla pretesa di riannodare i fili del ragionamento intessuto negli ultimi anni. Difficile perché nell’epoca degli specialismi, dei tecnicismi, l’opera dell’intellettuale siciliano si è distinta per una sempre più spiccata apertura verso la complessità del presente, al fine di abbracciarlo non più solamente mediante la chiave interpretativa giuridico-politica, aderente alla propria formazione accademica, ma con ripetute esplorazioni nella psicanalisi, nella teologia, nella filosofia. La contaminazione dei saperi, d’altronde, come ineludibile sforzo per chiunque non si accontenti delle decodificazioni gestite dai mass-media, è la frontiera estrema di resistenza al pensiero omologante che inaridisce le fonti della conoscenza e della riflessione dell’uomo sul suo essere in società.

Incanalata entro questa visione delle turbolenze che rendono questo torno di tempo sempre più etichettato come “di crisi”, la parola, sulla quale Barcellona è ritornato anche nella sua ultima monografia, Parolepotere (Castelvecchi, Roma, 2013), è la trincea dalla quale organizzare una resistenza contro l’onnipotenza della Tecnica – metafora ma anche dispositivo narcotizzante dei vincitori –, nella consapevolezza che dietro il lessico vi sia l’arcano del potere. Non solamente nella misura in cui la parola venga forgiata continuamente dai vincitori, per quanto temporanei, che si arrogano il diritto di riscrivere la storia, quanto e soprattutto affinché la pur necessaria riduzione della complessità non si trasformi in un’operazione volta a oggettivare il dato di realtà. Questa operazione, infatti, non soltanto rappresenta la meschina rimozione di tutte quelle forme di sapere che non abbaino raggiunto la lucidità concettuale del discorso dei vincitori, benché contengano depositi di sapienza che potrebbero essere d’ausilio a una rilettura multilaterale delle vicende umane, ma segnala anche una residua possibilità di ancoraggio a un protagonismo del soggetto contro la mistificazione, o forse ossessione, scientista dell’attribuzione al mondo di una modalità di funzionamento fondata su leggi oggettive e non, viceversa, su azioni consapevoli e intenzionali.

In questo cul de sac, le residue possibilità di trasformazione sociale sono affidate alla parola poetica, perché è il poeta che, come il folle nella declinazione erasmiana, destruttura il discorso e rimodula, a uso proprio e della comunità, il linguaggio attraverso cui provare a rappresentare il mondo. Il poeta, come scrive Barcellona, «inaugura sempre un nuovo uso delle parole, o addirittura crea vocaboli che innovano radicalmente l’ordine del discorso» (ibidem, p. 27). La parola poetica, insomma, anticipa i cambiamenti nelle prassi, non semplicemente in maniera oracolare, ma (ri)accompagnando l’uomo lungo il sentiero del dubbio dell’interrogazione esistenziale e di senso. La parola poetica, cioè, al di là del suo incasellamento in un’inclinazione più spiccatamente civile o intimistica, opera proprio per far capire quel quid al quale il discorso convenzionale, dialogico o narrativo, non giunge. In questo sforzo, di carattere prettamente soggettivo come in tutte le arti asemantiche, che, a differenza per esempio della musica, corrono il rischio di avere una “scadenza” per la fruizione più ravvicinata nel tempo, vi è chi ha interpretato uno degli snodi più rilevanti tra il Barcellona ateo e comunista e il Barcellona in dialogo con l’anima e con Dio degli ultimi anni. Con l’usuale, saccente, pretesa, di periodizzare la vita altrui, quasi che la stessa non costituisca comunque un unicum, benché arricchito da nuove ricalibrazioni del pensiero, dalla coltivazione di domande sempre più pressanti. Eppure in Barcellona immutata è rimasta la tensione (e il malessere per la calante aspirazione comune) alla rappresentazione di un universo simbolico soggettivo e collettivo, in grado di restituire “senso” a quest’era post-ideologica con una grande narrazione (cfr. L’oracolo di Delfi e l’isola della capre, Marietti, Genova-Milano, 2009).

Le grandi narrazioni, lungi dal costituire un’anticaglia cestinata dalla “fine della storia” teorizzata da Fukuyama, sono la palestra entro la quale esercitare il conflitto sociale e coltivare gli interrogativi. La palestra, cioè, nella quale ricercare una narrazione comune non già per ingabbiare e omologare ruoli, appiattire status, narcotizzare passioni, ma della quale ridisegnare continuamente il perimetro mediante la forza antagonista della parola, per dare vita a sempre nuove catene significanti. Appunto per non macerare nell’ovvio, nel dominio dell’oggettività, ma per riscoprire la dimensione misterica dell’esistente. In fondo, anche il formidabile strumento della parola non è onnipotente, ma nasce all’interno di uno spazio che i greci ritennero di definire “anima”.

L’indagine sull’anima ha avuto, nell’ultimo quindicennio della produzione barcelloniana – fatta anche di poesia e di pittura –, appunto lo scopo di restituire alla parola la funzione simbolica di relazione emotiva con la “cosa”, liberandola dalla gabbia d’acciaio in cui la stessa, trasformata in strumento di ordinamento del reale, ha finito per chiudere il mondo dell’accadere, deformando il “dire” da creazione/scoperta di figure e forme in un pre-dire non autenticamente creativo ma adattivo alla sfera del fare così come organizzata dalle logiche della produzione e riproduzione seriale tipiche dell’economia capitalistica (cfr. La parola perduta, Dedalo, Bari, 2007).

Il punto è che, dinanzi alla potenza ineffabile della Tecnica postulata da Severino, che sembra delineare un orizzonte in cui il ribaltamento della datità si configura come difficilmente scardinabile anche con gli esperimenti di mobilitazione collettiva pienamente sbocciati nel Novecento, come i partiti, i sindacati, ecc., diventa cardinale immaginare e sperimentare un lessico mentale che viaggi su frequenze differenti da quelle del lessico del mondo. Questa, come già accennato, è una delle residue possibilità di resistenza alla costruzione di paradigmi interpretativi della realtà schiacciati sull’accondiscendenza ossequiosa a una presentificazione assoluta che non soltanto cancella ogni labile legame con la memoria e la sua rielaborazione, ma occupa, con brutale violenza, anche l’orizzonte, per definire il futuro a propria immagine.

Il paradigma del post-umano utilizzato da Barcellona quale cartina di tornasole della tragedia nichilistica dell’Occidente trova proprio nella fine della parola, nella sua riduzione a segno, secondo quanto codificato dalla Scienza e dalla Tecnica, il prosciugamento nefasto della percezione del tempo che ci fonda come Uomini.