Reproducimos aquí un escrito de Fernando Trujillo, nuestro colaborador habitual desde Méjico. Si quieres colaborar con nuestro blog enviandonos artículos, contáctate al correo electrónico que figura en rojo. Consideramos de todos modos importante señalar que las opiniones de cada autor aquí volcadas, no son siempre las nuestras. ¡Anímate a colaborar! despertarloeterno@hotmail.com

vendredi, 18 septembre 2009

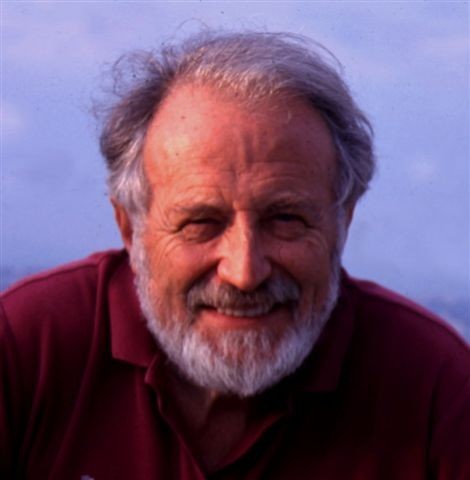

Etre rebelle selon Dominique Venner

Être rebelle selon Dominique Venner

Je me demande surtout comment on pourrait ne pas l’être ! Exister, c’est combattre ce qui me nie. Etre rebelle, ce n’est pas collectionner des livres impies, rêver de complots fantasmagoriques ou de maquis dans les Cévennes. C’est être à soi-même sa propre norme. S’en tenir à soi quoi qu’il en coûte. Veiller à ne jamais guérir de sa jeunesse. Préferer se mettre tout le monde à dos que se mettre à plat ventre. Pratiquer aussi en corsaire et sans vergogne le droit de prise. Piller dans l’époque tout ce que l’on peut convertir à sa norme, sans s’arrêter sur les apparences. Dans les revers, ne jamais se poser la question de l’inutilité d’un combat perdu.

Dominique Venner

Source : Recounquista [1]

Article printed from :: Novopress Québec: http://qc.novopress.info

URL to article: http://qc.novopress.info/6108/etre-rebelle-selon-dominique-venner/

URLs in this post:

[1] Recounquista: http://recounquista.com/

13:15 Publié dans Réflexions personnelles | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : réflexions personnelles, nouvelle droite, philosophie, rebellion, non conformisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les espions de l'or noir

Les espions de l’or noir

Le pétrole, « maître du monde » ? Oui, mais comment en est-on arrivé là ? Des rivalités pour contrôler la route des Indes à l’émergence des Etats-Unis comme puissance mondiale, les pays anglo-saxons ont su étendre leur influence en Asie centrale, dans le Caucase et au Proche-Orient, avec, au final, leur mainmise sur les principales ressources pétrolières mondiales.

Gilles Munier remonte aux origines du Grand jeu et de la fièvre du pétrole pour raconter la saga des espions de l’or noir et la malédiction qui s’est abattue sur les peuples détenteurs de ces richesses. Il brosse les portraits des agents secrets de Napoléon 1er et de l’Intelligence Service, du Kaiser Guillaume II et d’Adolphe Hitler, des irréguliers du groupe Stern et du Shay – ancêtres du Mossad – ou de la CIA, dont les activités ont précédé ou accompagné les grands bains de sang du 19ème et du début du 20ème siècle.

Parmi d’autres, on croise les incontournables T.E Lawrence dit d’Arabie, Gertrude Bell, St John Philby et Kermit Roosevelt, mais aussi des personnages moins connus comme Sidney Reilly, William Shakespear, Wilhelm Wassmuss, Marguerite d’Andurain, John Eppler, Conrad Kilian. Puis, descendant dans le temps, Lady Stanhope, le Chevalier de Lascaris, William Palgrave, Arthur Conolly et David Urquhart.

« On dit que l’argent n’a pas d’odeur, le pétrole est là pour le démentir » a écrit Pierre Mac Orlan. « Au Proche-Orient et dans le Caucase », ajoute Gilles Munier, « il a une odeur de sang ». Lui qui a observé, sur le terrain, plusieurs conflits au Proche-Orient, montre que ces drames n’ont pas grand chose à voir avec l’instauration de la démocratie et le respect des droits de l’homme. Ils sont, comme la guerre d’Afghanistan et celles qui se profilent en Iran ou au Darfour, l’épilogue d’opérations clandestines organisées pour contrôler les puits et les routes du pétrole.

Contact : gilmunier@gmail.com [1]

* Editions Koutoubia – Groupe Alphée-Editplus, 11 rue Jean de Beauvais – 75005 PARIS

Source : http://espions-or.noir.over-blog.com/ [2]

Article printed from :: Novopress Québec: http://qc.novopress.info

URL to article: http://qc.novopress.info/6150/les-espions-de-l%e2%80%99or-noir/

URLs in this post:

[1] gilmunier@gmail.com: http://qc.novopress.infogilmunier@gmail.com

[2] http://espions-or.noir.over-blog.com/: http://espions-or.noir.over-blog.com/

00:10 Publié dans Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : pétrole, hydrocarbures, histoire, espionnage, moyen orient, impérialisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

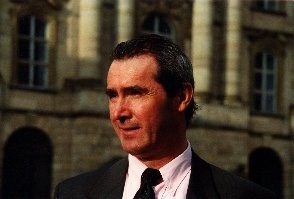

Gespräch mit Dr. Tomislav Sunic

Archiv von "SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES" - 1998

Gespräch mit Dr. Tomislav Sunic

Tomislav Sunic, 1953 in Zagreb/Agram geboren, ist Autor von drei wichtigen Büchern Against Democracy and Equality. The European New Right, Dissidence and Titoism (beide bei Peter Lang, Bern/Frankfurt a. M.) und Americka Ideologija (= Die amerikanische Ideologie). Wegen politischer Dissidenz mußte er 1983 in die Vereinigten Staaten emigrieren, wo er in der California State University von Sacramento und in der University of California in Santa Barbara studierte und promovierte. Er hat in den VSA für verschiedenen Zeitschriften geschrieben und hat in der California State University in Long Beach und in den Juniata College in Pennsylvanien doziert. Seit 1993 ist er zurück in Europa. Heute schreibt er für Chronicles of American Culture und für Eléments (Frankreich).

Dr. Sunic, in welchem Familienkontext sind Sie aufgewachsen? Welche ideologische Einflüße hat ihr Vater auf Ihnen gehabt?

Mein Vater war Anwalt, hat politische Dissidenten verteidigt, wurde zweimal wegen politischer Nonkonformität im kommunistischen Jugoslawien eingesperrt. Er war antikommunistisch und stark vom kroatischen Bauernkatholizismus geprägt. Amnisty International hat ihn als Mustergefangenen adoptiert, weil er 1985 der älteste politische Gefangene im kommunistischen Osteuropa war. Die FAZ und Die Welt haben sich auch für ihn engagiert. Wir lebten in sehr bescheidene Umstände, wir hatten weder Fernsehen noch Pkw. Mein Vater war der Meinung, nur Bücher machen eine richtige Bildung. Wir wurden ständig schikaniert und mein Vater verlor bald das Recht, seinen Beruf auszuüben. Er war während des Krieges nicht Mitglied der Ustascha, stand eher kritisch dem kroatischen Staatswesen von Pavelic gegenüber. Mein Vater war Domobran, d. h. in der Einwohnerwehr. Heute ist er 83 und hat 1996 seine Memoiren unter den Titel “Moji "inkriminari” zapisi” (= Meine “inkriminierten” Papiere) publiziert, wobei er im neuen kroatischen Staat viel Aufmerksamkeit geregt hat.

Aber wie würden Sie ihre eigenen philosophisch-ideologischen Weg beschreiben?

Um es kurz zu fassen, bin ich ein “reaktionärer Linke” oder ein “konservativer Sozialist”. Ich gehöre keiner Sekte oder keiner theologish-ideologischer Partei. Ich war antikommunistisch wie mein Vater, aber, als ich jung war, nahm meine persönliche Revolte den Gewand des Hippismus. Ich pilgerte nach Amsterdam, danach nach Indien im kaschmirischen Srinagar und in der Stadt Goa. Der Ersatz zum Kommunismus war für mich die hippy Gemeinschaft. Ich war gegen alle Formen von Establishment, egal welche ideologische Gestalt es hat. Aber ich verstand sehr bald, daß der Hippismus auch eine traurige Farce war. Um es salopp auszudrucken: “Eben beim Joints-Rauchen, haben die Hippies eine Art Hierarchie mit aller möglichen Heuchelei reproduziert”. Das gilt auch selbstverständlich für den Feminismus und den Schwulenbewegungen. Mein einziger Trost war das Lesen der großen Klassiker der Weltliteratur. Die sind die richtigen Antidoten zum Konformismus. Als Kind las ich Tintin (dt. “Tim”) auf französisch, Karl May auf deutsch sowie den Dichter Nikolas Lenau. Als Jugendlicher las ich weiter deutsche, französische und englische Bücher. Mit dieser klassischen Bildung und meiner Hippy-Erfahrung, habe ich dann die Rock-Musik entdeckt, u. a. “Kraftwerk” und Frank Zappa, der zur gleichen Zeit Anarchist, Pornograph und Nonkonformer war. Zappa war für mich sehr wichtig, da er mich die Realsprache gegen alle Heucheleien der etablierten Gesellschaft gelernt hat. Mit ihm habe ich das amerikanische Slang bemeistern können, die ich oft benutzt in meinem Schreiben, um das links-liberale Establishment diesmal konservativ aber immer ironisch und höhnisch zu bespotten.

Können Sie uns ein Paar Worte über ihre Studien sagen?

In Kroatien zur Zeit der kommunistischen Herrschaft habe ich Literatur, moderne Sprachen und Vergleichende Literatur studiert. Ich war 1977 fertig. Ästhetisch und graphisch konnte ich den Jugo-Kommunismus nicht mehr ertragen, Betonsprache und balkanische Vetternwirtschaft machten mich kotzen. 1980 nutzte ich die Gelegenheit, für ein jugoslawisches Unternehmen in Algerien als Dolmetscher zu arbeiten. 1983 emigrierte ich in den Vereinigten Staaten. Dort las ich wiedermal die nonkonforme Literatur. Damals waren meine Lieblingsautoren Kerouac und der Franzose Barbusse; weiter habe ich Sartre gelesen, weil er nicht nur Linker sondern ein bissiger Entlarver war, ohne Hermann Hesse zu vergessen, weil er mich an meine Indien-Reise erinnerte.

In den Vereinigten Staaten haben Sie den amerikanischen Neokonservatismus entdeckt?

Zuerst muß ich sagen, daß der amerikanische Neokonservatismus nicht mit dem europäischen gleichgestellt sein kann. Links, rechts, was heißt das heute? Ich teile die Leute in Konformisten und Nonkonformisten. Der Mann, der mich in diesen Kreisen beeindruckt hat, war Thomas Molnar. Er war damals mein Mentor, weil er Ungarn und Angehöriger des ehemaligen k.u.k-Kulturraumes ist. Molnar ist ganz und klar Konservativer aber er bleibt ein Mann mit Ironie und sehr viel Humor. So trifft er immer das Wesentliche. Der Schmitt- und Hegel-Spezialist Paul Gottfried übte auch auf mich einen tiefen Einfluß. Danach habe ich Paul Fleming kennengelernt, der die Zeitschrift Chronicles of American Culture leitet. Ich bin Autor der Redaktion seit mehr als zehn Jahre. Aber Rebell bin ich geblieben, deshalb interessierte ich mich intensiv für die sogenannten europäischen Neue Rechte bzw. den Neokonservatismus Europas mit Mohler und seinem heroischen Realismus, Schrenck-Notzing und seiner Feindschaft jeder öffentlichen Meinungsdiktatur gegenüber, Kaltenbrunner und seiner Faszination für die Schönheit in unserer geistigen Trümmernwelt, Benoist mit seine Synthese in Von rechts gesehen. Ich habe dann die Autoren gelesen, die die Neue Rechte empfahl. Mein Buch über die Neue Rechte ist eigentlich ein follow-up meines Eintauchens in diese Bildungswelt. Aber die Benennung “Neue Rechte” kann auch trügen: ich ziehe es vor, diese neue Kulturbewegung als “GRECE” zu bezeichnen, d.h. wie Benoist es sieht, als ein dynamische Forschungstelle zur Erhaltung der Lebendigkeit unserer gesamteuropäischen Kultur. Céline (mit seiner groben Pariser Rotwelschsprache die alle eingebürgerten Gewißheiten zertrümmert), Benn und Cioran mit ihrem unnachahmbaren Stil bleiben aber die Lieblingsautoren des Rebells, der ich bin und bleiben werde.

Sie sind in Kroatien und in Europa 1993 zurückgekommen. Wie haben Sie die neue Lage in Ostmitteleuropa beurteilt?

Das Schicksal Kroatiens ist eng mit dem Schicksal Deutschlands verbunden, egal welches politische System in Deutschland herrscht. Sowie der schwedische Gründer der Geopolitik, Rudolf Kjellén, sagte: “man kann seine geopolitischen Bestimmung nicht entweichen”. Andererseits, hat uns Erich Voegelin gelernt, daß man politische Religionen wie Faschismus und Kommunismus wegwerfen kann, aber daß man das Schicksal seines Heimatlandes nicht entrinnen kann. Das deutsche Schicksal, eingrekreist zu sein, ist dem kroatischen Schicksal ähnlich, eben wenn Kroatien nur ein kleiner Staat Zwischeneuropas ist. Ein gemeinsames geographisches Fakt vereint uns Deutsche und Kroaten: die Adria. Das Reich und die Doppelmonarchie waren stabile Staatswesen solange sie eine Öffnung zum Mittelmeer durch die Adria hatten. Die westlichen Mächte haben es immer versucht, die Mächte Mitteleuropas den Weg zur Adria zu versperren: Napoleon riegelte den Zugang Österreiches zur Adria, indem er die Küste direkt an Frankreich annektierte (die sog. “départements illyriens”), später sind die Architekte von Versailles in dieser Politik meisterhaft gelungen. Deutschland verlor den Zugang zum Mittelmeer und Kroatien verlor sein mitteleuropäisches Hinterland sowie seine Souveränität. Das ist der Schlüssel des kroatischen Dramas im 20. Jahrhundert.

Wird Kroatien den Knoten durchhaken können? Seine Position zwischen Mitteleuropa und Mittelmeer optimal benutzen können?

Unsere Mittelschichten und unsere Intelligentsija wurden total durch die Titoistischen Repression nach 1945 liquidiert: Das ist soziobiologisch gesehen die schlimmste Katastrophe für das kroatisches Volk. Der optimale und normale Elitekreislauf ist seitdem nicht mehr möglich. Der “homo sovieticus” und der “homo balkanicus” dominieren, zu Ungunsten des “homini mitteleuropei”.

Wie sehen Sie die Beziehungen zwischen Kroatien und seinen balkanischen Nachbarn?

Jede aufgezwungene Heirat scheitert. Zweimal in diesem Jahrhundert ist die Heirat zwischen Kroatien und Jugoslawien gescheitert. Es wäre besser, mit den Serben, Bosniaken, Albanern und Makedoniern als gute Nachbarn statt als schlechte und zänkische Eheleute zu leben. Jedes Volk in ehemaligen und in Restjugoslawien sollte seinen eigenen Staat haben. Das jugoslawische Experiment ist ein Schulbeispiel für das Scheitern jeder aufgezwungen Multikultur.

Was wird nach Tudjman?

Hauptvorteil von Tudjman ist es, daß er völlig die Geschichtsschreibung des Jugokommunismus entlarvt hat. Größtenteils hat er das kroatische Volk und besonders die Jugend von der Verfälschung der Geschichte genesen.

Herr Dr. Sunic, wir danken Ihnen für dieses Gespräch.

(Robert STEUCKERS, Brüssel, den 13. Dezember 1997).

00:05 Publié dans Entretiens | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : croatie, mitteleuropa, europe centrale, politique internationale, yougoslavie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 17 septembre 2009

Acuerdo bilateral Kosovo-EEUU sobre ayuda economica

Acuerdo bilateral Kosovo-EEUU sobre ayuda económica

Kosovo y Estados Unidos firmaron este lunes su primer acuerdo bilateral de ayuda económica, centrado en las infraestructuras, aunque el monto no fue precisado, anunciaron fuentes oficiales en Pristina.

Kosovo y Estados Unidos firmaron este lunes su primer acuerdo bilateral de ayuda económica, centrado en las infraestructuras, aunque el monto no fue precisado, anunciaron fuentes oficiales en Pristina.

“La ayuda se destinará al desarrollo (de Kosovo) y en particular a las diferentes infraestructuras, y en consecuencia a la economía, los transportes y la educación”, declaró el presidente kosovar, Fatmir Sejdiu.

El canciller kosovar indicó en un comunicado que otro acuerdo de 13 millones de dólares fue firmado con Estados Unidos para reforzar el Estado de derecho en Kosovo.

El ministro de Relaciones Exteriores, Skender Hyseni, indicó que la ayuda sería empleada en crear “una estructura legal estable” en Kosovo.

Estados Unidos fue uno de los primeros países en reconocer la independencia de Kosovo, proclamada de manera unilateral en febrero de 2008.

Belgrado no reconoce la independencia y considera que Kosovo es una provincia serbia.

Extraído de Univisión.

00:20 Publié dans Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, kosovo, etats-unis, économie, balkans, impérialisme, impérialisme américain, géopolitique, europe, affaires européennes, politique, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

A. Chauprade: la Russie, obstacle majeur sur la route de l'Amérique-Monde

Aymeric Chauprade : La Russie, obstacle majeur sur la route de « l’Amérique-monde»

[1]Alors que les Etats-Unis tentent, depuis le 11 septembre 2001, d’accélérer leur projet de transformation du monde à l’image de la société démocratique et libérale rêvée par leurs pères fondateurs, les civilisations non occidentales se dressent sur leur chemin et affirment leur volonté de puissance.

La Russie, en particulier constitue un obstacle géopolitique majeur pour Washington. Elle entend défendre son espace d’influence et montrer au monde qu’elle est incontournable sur le plan énergétique.

L’un des auteurs classiques de la géopolitique, Halford J. Mackinder (1861-1947), un amiral britannique, qui professa la géographie à Oxford, défendait comme thèse centrale que les grandes dynamiques géopolitiques de la planète s’articulaient autour d’un cœur du monde (heartland), l’Eurasie. Pivot de la politique mondiale que la puissance maritime ne parvenait pas à atteindre, l’Eurasie avait pour cœur intime la Russie, un Empire qui « occupait dans l’ensemble du monde la position stratégique centrale qu’occupe l’Allemagne en Europe ».

Autour de cet épicentre des secousses géopolitiques mondiales, protégé par une ceinture faite d’obstacles naturels (vide sibérien, Himalaya, désert de Gobi, Tibet) que Mackinder appelle le croissant intérieur, s’étendent les rivages du continent eurasiatique : Europe de l’Ouest, Moyen-Orient, Asie du Sud et de l’Est.

Au-delà de ces rivages, par-delà les obstacles marins, deux systèmes insulaires viennent compléter l’encadrement du heartland : la Grande-Bretagne et le Japon, têtes de pont d’un croissant plus éloigné auquel les États-Unis appartiennent.

Selon cette vision du monde, les puissances maritimes mondiales, les thalassocraties que défend Mackinder, doivent empêcher l’unité continentale eurasiatique.

Elles doivent donc maintenir les divisions est/ouest entre les principales puissances continentales capables de nouer des alliances (France/Allemagne, Allemagne/Russie, Russie/Chine) mais aussi contrôler les rivages du continent eurasiatique.

Cette matrice anglo-saxonne, que l’on peut appliquer au cas de l’Empire britannique au XIXe siècle, comme à celui de la thalassocratie américaine au XXe siècle, reste un outil pertinent pour comprendre la géopolitique d’aujourd’hui.

La théorie de Mackinder nous rappelle deux choses que les thalassocraties anglo-saxonnes n’ont jamais oubliées : il n’y a pas de projet européen de puissance (d’Europe puissance) sans une Allemagne forte et indépendante (or l’Allemagne reste largement sous l’emprise américaine depuis 1945) ; il n’y pas d’équilibre mondial face au mondialisme américain sans une Russie forte.

L’Amérique veut l’Amérique-monde ; le but de sa politique étrangère, bien au-delà de la seule optimisation de ses intérêts stratégiques et économiques du pays, c’est la transformation du monde à l’image de la société américaine. L’Amérique est

messianique et là est le moteur intime de sa projection de puissance. En 1941, en signant la Charte de l’Atlantique, Roosevelt et Churchill donnaient une feuille de route au rêve d’un gouvernement mondial visant à organiser une mondialisation libérale et démocratique. Jusqu’en 1947, l’Amérique aspira à la convergence avec l’URSS dans l’idée de former avec celle-ci un gouvernement mondial, et ce, malgré l’irréductibilité évidente des deux mondialismes américain et soviétique. Deux ans après l’effondrement européen de 1945, les Américains comprirent qu’ils ne parviendraient pas à entraîner les Soviétiques dans leur mondialisme libéral et ils se résignèrent à rétrécir géographiquement leur projet : l’atlantisme remplaça provisoirement le mondialisme.

Puis, en 1989, lorsque l’URSS vacilla, le rêve mondialiste redressa la tête et poussa l’Amérique à accélérer son déploiement mondial. Un nouvel ennemi global, sur le cadavre du communisme, fournissait un nouveau prétexte à la projection globale : le terrorisme islamiste. Durant la Guerre froide, les Américains avaient fait croître cet ennemi, pour qu’il barre la route à des révolutions socialistes qui se seraient tournées vers la Russie soviétique. L’islamisme sunnite avait été l’allié des Américains contre la Russie soviétique en Afghanistan. Ce fut le premier creuset de formation de combattants islamistes sunnites, la matrice d’Al Qaida comme celle des islamistes algériens… Puis il y eut la révolution fondamentaliste chiite et l’abandon par les Américains du Shah d’Iran en 1979. Le calcul de Washington fut que l’Iran fondamentaliste chiite ne s’allierait pas à l’URSS, contrairement à une révolution marxiste, et qu’il offrirait un contrepoids aux fondamentalistes sunnites.

Dans le monde arabe, ce furent les Frères musulmans qui, d’Egypte à la Syrie, furent encouragés. Washington poussa l’Irak contre l’Iran, et inversement, suivant le principe du « let them kill themselves (laissez-les s’entretuer) » déjà appliqué aux

peuples russe et allemand, afin de détruire un nationalisme arabe en contradiction avec les intérêts d’Israël. L’alliance perdura après la chute de l’URSS. Elle fut à l’œuvre dans la démolition de l’édifice yougoslave et la création de deux Etats musulmans en Europe, la Bosnie-Herzégovine puis le Kosovo.

L’islamisme a toujours été utile aux Américains, tant dans sa situation d’allié face au communisme durant la Guerre froide, que dans sa nouvelle fonction d’ennemi officiel depuis la fin de la bipolarité. Certes, les islamistes existent réellement ;

ils ne sont pas une création imaginaire de l’Amérique ; ils ont une capacité de nuisance et de déstabilisation indéniable. Mais s’ils peuvent prendre des vies, ils ne changeront pas la donne de la puissance dans le monde.

La guerre contre l’islamisme n’est que le paravent officiel d’une guerre beaucoup plus sérieuse : la guerre de l’Amérique contre les puissances eurasiatiques.

Après la disparition de l’URSS, il est apparu clairement aux Américains qu’une puissance continentale, par la combinaison de sa masse démographique et de son potentiel industriel, pouvait briser le projet d’Amérique-monde : la Chine. La formidable ascension industrielle et commerciale de la Chine face à l’Amérique fait penser à la situation de l’Allemagne qui, à la veille de la Première Guerre mondiale, rattrapait et dépassait les thalassocraties anglo-saxonnes. Ce fut la cause première de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Si la Chine se hisse au tout premier rang des puissances pensent les stratèges américains, par la combinaison de sa croissance économique et de son indépendance géopolitique, et tout en conservant son modèle confucéen à l’abri du démocratisme occidental, alors c’en est fini de l’Amérique-monde. Les Américains peuvent renoncer à leur principe de Destinée manifeste (Principle of Manifest Destiny) de 1845 ainsi qu’au messianisme de leurs pères fondateurs, fondamentalistes biblistes ou franc-maçons.

Alors que l’URSS venait à peine de s’effondrer, les stratèges américains orientèrent donc leurs réflexions sur la manière de contenir l’ascension de la Chine.

Sans doute comprirent-ils alors toute l’actualité du raisonnement de Mackinder. Les Anglo-Saxons avaient détruit le projet eurasiatique des Allemands, puis celui des Russes ; il leur fallait abattre celui des Chinois. Une nouvelle fois la Mer voulait faire pièce à la Terre.

La guerre humanitaire et la guerre contre le terrorisme seraient les nouveaux prétextes servant à masquer les buts réels de la nouvelle grande guerre eurasiatique : la Chine comme cible, la Russie comme condition pour emporter la bataille.

La Chine comme cible parce que seule la Chine est une puissance capable de dépasser l’Amérique dans le rang de la puissance matérielle à un horizon de vingt ans. La Russie comme condition parce que de son orientation stratégique découlera largement l’organisation du monde de demain : unipolaire ou multipolaire.

Face à la Chine, les Américains entreprirent de déployer une nouvelle stratégie globale articulée sur plusieurs volets :

* L’extension d’un bloc transatlantique élargi jusqu’aux frontières de la Russie et à l’ouest de la Chine.

* Le contrôle de la dépendance énergétique de la Chine.

* L’encerclement de la Chine par la recherche ou le renforcement d’alliances avec des adversaires séculaires de l’Empire du Milieu (les Indiens, les Vietnamiens,les Coréens, les Japonais, les Taïwanais…).

* L’affaiblissement de l’équilibre entre les grandes puissances nucléaires par le développement du bouclier anti-missiles.

* L’instrumentalisation des séparatismes (en Serbie, en Russie, en Chine, et jusqu’aux confins de l’Indonésie) et le remaniement de la carte des frontières (au Moyen-Orient arabe).

Washington a cru, dès 1990, pouvoir faire basculer la Russie de son côté, pour former un vaste bloc transatlantique de Washington à Moscou avec au milieu la périphérie européenne atlantisée depuis l’effondrement européen de 1945. Ce fut

la phrase de George Bush père, lequel en 1989 appelait à la formation d’une alliance « de Vladivostok à Vancouver » ; en somme le monde blanc organisé sous la tutelle de l’Amérique, une nation paradoxalement appelée, par le contenu même de son idéologie, à ne plus être majoritairement blanche à l’horizon 2050.

L’extension du bloc transatlantique est la première dimension du grand jeu eurasiatique. Les Américains ont non seulement conservé l’OTAN après la disparition du Pacte de Varsovie mais ils lui ont redonné de la vigueur : premièrement l’OTAN est passé du droit international classique (intervention uniquement en cas d’agression d’un Etat membre de l’Alliance) au droit d’ingérence. La guerre contre la Serbie, en 1999, a marqué cette transition et ce découplage entre l’OTAN et le droit international. Deuxièmement, l’OTAN a intégré les pays d’Europe centrale et d’Europe orientale. Les espaces baltique et yougoslave (Croatie, Bosnie, Kosovo) ont été intégrés à la sphère d’influence de l’OTAN. Pour étendre encore l’OTAN et resserrer l’étau autour de la Russie, les Américains ont fomenté les révolutions colorées (Géorgie en 2003, Ukraine en 2004, Kirghizstan en 2005), ces retournements politiques non violents, financés et soutenus par des fondations et des ONG américaines, lesquelles visaient à installer des gouvernements anti-russes. Une fois au pouvoir, le président ukrainien pro-occidental demanda naturellement le départ de la flotte russe des ports de Crimée et l’entrée de son pays dans l’OTAN.

Quant au président géorgien il devait, dès 2003, militer pour l’adhésion de son pays dans l’OTAN et l’éviction des forces de paix russes dédiées depuis 1992 à la protection des populations abkhazes et sud-ossètes.

À la veille du 11 septembre 2001, grâce à l’OTAN, l’Amérique avait déjà étendu fortement son emprise sur l’Europe. Elle avait renforcé l’islam bosniaque et albanais et fait reculer la Russie de l’espace yougoslave.

Durant les dix premières années post-Guerre froide, la Russie n’avait donc cessé de subir les avancées américaines. Des oligarques souvent étrangers à l’intérêt national russe s’étaient partagés ses richesses pétrolières et des conseillers libéraux proaméricains entouraient le président Eltsine. La Russie était empêtrée dans le conflit tchétchène, remué largement par les Américains comme d’ailleurs l’ensemble des abcès islamistes. Le monde semblait s’enfoncer lentement mais sûrement dans l’ordre mondial américain, dans l’unipolarité.

En 2000, un événement considérable, peut-être le plus important depuis la fin de la Guerre froide (plus important encore que le 11 septembre 2001) se produisit pourtant : l’accession au pouvoir de Vladimir Poutine. L’un de ces retournements de l’histoire qui ont pour conséquences de ramener celle-ci à ses fondamentaux, à ses constantes.

Poutine avait un programme très clair : redresser la Russie à partir du levier énergétique. Il fallait reprendre le contrôle des richesses du sous-sol des mains d’oligarques peu soucieux de l’intérêt de l’Empire. Il fallait construire de puissants opérateurs pétrolier (Rosneft) et gazier (Gazprom) russes liés à l’Etat et à sa vision stratégique. Mais Poutine ne dévoilait pas encore ses intentions quant au bras de fer américano-chinois. Il laissait planer le doute. Certains, dont je fais d’ailleurs partie puisque j’analysais à l’époque la convergence russo-américaine comme passagère et opportune (le discours américain de la guerre contre le terrorisme interdisait en effet momentanément la critique américaine à propos de l’action russe en Tchétchénie), avaient compris dès le début que Poutine reconstruirait la politique indépendante de la Russie ; d’autres pensaient au contraire qu’il serait occidentaliste. Il lui fallait en finir avec la Tchétchénie et reprendre le pétrole. La tâche était lourde. Un symptôme évident pourtant montrait que Poutine allait reprendre les fondamentaux de la grande politique russe : le changement favorable à l’Iran et la reprise des ventes d’armes à destination de ce pays ainsi que la relance de la coopération en matière de nucléaire civil.

Pourquoi alors l’accession de Poutine était-elle un événement si considérable ?

Sans apparaître à l’époque de manière éclatante, cette arrivée signifiait que l’unipolarité américaine, sans la poursuite de l’intégration de la Russie à l’espace transatlantique, était désormais vouée à l’échec, et avec elle, par conséquent, la grande stratégie visant à briser la Chine et à prévenir l’émergence d’un monde multipolaire.

Au-delà encore, nombre d’Européens ne perçurent pas immédiatement que Poutine portait l’espoir d’une réponse aux défis de la compétition économique mondiale fondée sur l’identité et la civilisation. Sans doute les Américains, eux, le comprirent-ils mieux que les Européens de l’Ouest. George Bush n’en fit-il pas l’aveu lorsqu’il avoua un jour qu’il avait vu en Poutine un homme habité profondément par l’intérêt de son pays ?

Le 11 septembre 2001 offrit pourtant l’occasion aux Américains d’accélérer leur programme d’unipolarité. Au nom de la lutte contre un mal qu’ils avaient eux-mêmes fabriqués, ils purent obtenir une solidarité sans failles des Européens (donc plus d’atlantisme et moins « d’Europe puissance »), un rapprochement conjoncturel avec Moscou (pour écraser le séparatisme tchétchéno-islamiste), un recul de la Chine d’Asie centrale face à l’entente russo-américaine dans les républiques musulmanes ex-soviétiques, un pied en Afghanistan, à l’ouest de la Chine donc et au sud de la Russie, et un retour marqué en Asie du Sud-est.

Mais l’euphorie américaine en Asie centrale ne dura que quatre ans. La peur d’une révolution colorée en Ouzbékistan poussa le pouvoir ouzbek, un moment tenté de devenir la grande puissance d’Asie centrale en faisant contrepoids au grand frère russe, à évincer les Américains et à se rapprocher de Moscou. Washington perdit alors, à partir de 2005, de nombreuses positions en Asie centrale, tandis qu’en Afghanistan, malgré les contingents de supplétifs qu’elle ponctionne à des Etats européens incapables de prendre le destin de leur civilisation en main, elle continue de perdre du terrain face à l’alliance talibano-pakistanaise, soutenue discrètement en sous-main par les Chinois qui veulent voir l’Amérique refoulée d’Asie centrale.

Les Chinois, de nouveau, peuvent espérer prendre des parts du pétrole kazakh et du gaz turkmène et construire ainsi des routes d’acheminement vers leur Turkestan (le Xinjiang). Pékin tourne ses espoirs énergétiques vers la Russie qui équilibrera à l’avenir ses fournitures d’énergie vers l’Europe par l’Asie (non seulement la Chine mais aussi le Japon, la Corée du Sud, l’Inde…).

Le jeu de Poutine apparaît désormais au grand jour. Il pouvait s’accorder avec Washington pour combattre le terrorisme qui frappait aussi durement la Russie. Il n’avait pas pour autant l’intention d’abdiquer quant aux prétentions légitimes de la Russie : refuser l’absorption de l’Ukraine (car l’Ukraine pour la Russie c’est une nation sœur, l’ouverture sur l’Europe, l’accès à la Méditerranée par la mer Noire grâce au port de Sébastopol en Crimée) et de la Géorgie dans l’OTAN. Et si l’indépendance du Kosovo a pu être soutenue par les Américains et des pays de l’Union européenne, au nom de quoi les Russes n’auraient-ils pas le droit de soutenir celles de l’Ossétie du Sud et de l’Abkhazie, d’autant que les peuples concernés eux-mêmes voulaient se séparer de la Géorgie ?

Mackinder avait donc raison. Dans le grand jeu eurasiatique, la Russie reste la pièce clé. C’est la politique de Poutine, bien plus que la Chine (pourtant cible première de Washington car possible première puissance mondiale) qui a barré la route à Washington. C’est cette politique qui lève l’axe énergétique Moscou (et Asie centrale)-Téhéran-Caracas, lequel pèse à lui seul ¼ des réserves prouvées de pétrole et près de la moitié de celles de gaz (la source d’énergie montante). Cet axe est le contrepoids au pétrole et au gaz arabes conquis par l’Amérique. Washington voulait étouffer la Chine en contrôlant l’énergie. Mais si l’Amérique est en Arabie Saoudite et en Irak (1ère et 3e réserves prouvées de pétrole), elle ne contrôle ni la Russie, ni l’Iran, ni le Venezuela, ni le Kazakhstan et ces pays bien au contraire se rapprochent. Ensemble, ils sont décidés à briser la suprématie du pétrodollar, socle de la centralité du dollar dans le système économique mondial (lequel socle permet à l’Amérique de faire supporter aux Européens un déficit budgétaire colossal et de renflouer ses banques d’affaires ruinées).

Nul doute que Washington va tenter de briser cette politique russe en continuant à exercer des pressions sur la périphérie russe. Les Américains vont tenter de développer des routes terrestres de l’énergie (oléoducs et gazoducs) alternatives à la toile russe qui est en train de s’étendre sur tout le continent eurasiatique, irriguant l’Europe de l’Ouest comme l’Asie. Mais que peut faire Washington contre le cœur énergétique et stratégique de l’Eurasie ? La Russie est une puissance nucléaire.

Les Européens raisonnables et qui ne sont pas trop aveuglés par la désinformation des médias américains, savent qu’ils ont plus besoin de la Russie qu’elle n’a besoin d’eux. Toute l’Asie en croissance appelle le pétrole et le gaz russe et iranien.

Dans ces conditions et alors que la multipolarité se met en place, les Européens feraient bien de se réveiller. La crise économique profonde dans laquelle ils semblent devoir s’enfoncer durablement conduira-t-elle à ce réveil ? C’est la conséquence positive qu’il faudrait espérer des difficultés pénibles que les peuples d’Europe vont endurer dans les décennies à venir.

Aymeric CHAUPRADE

Source du texte : ACADÉMIE DE GÉOPOLITIQUE DE PARIS [2]

Article printed from :: Novopress.info Flandre: http://flandre.novopress.info

URL to article: http://flandre.novopress.info/5057/aymeric-chauprade-la-russie-obstacle-majeur-sur-la-route-de-l%e2%80%99amerique-monde/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://flandre.novopress.info/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/chauprade_barbe.jpg

[2] ACADÉMIE DE GÉOPOLITIQUE DE PARIS: http://www.strategicsinternational.com/

00:15 Publié dans Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : géopolitique, russie, etats-unis, géostratégie, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

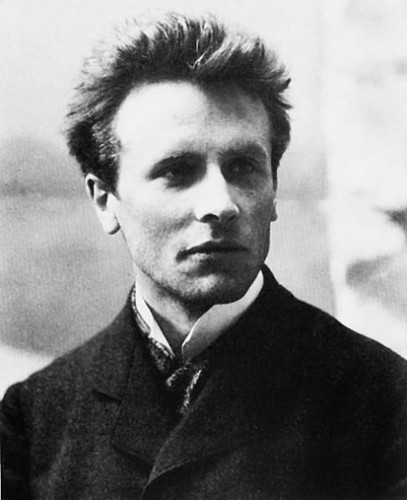

On The Biocentric Metaphysics of Ludwig Klages

On The Biocentric Metaphysics of Ludwig Klages

by John Claverley Cartney

Without a doubt, "The Spirit as Adversary of the Soul" by Klages is a great work of philosophy. -- Walter Benjamin

Out of Phlegethon!

Out of Phlegethon,

Gerhart

Art thou come forth out of Phlegethon?

with Buxtehude and Klages in your satchel… -- From Canto LXXV by Ezra Pound

Oliveira said, "Let’s keep on looking for the Yonder, there are plenty of Yonders that keep opening up one after the other. I’d start by saying that this technological reality that men of science and the readers of France-Soir accept today, this world of cortisone, gamma rays, and plutonium, has as little to do with reality as the world of the Roman de la Rose. If I mentioned it a while back to our friend Perico, it was in order to make him take note that his æsthetic criteria and his scale of values are pretty well liquidated and that man, after having expected everything from intelligence and from the spirit, feels that he’s been betrayed, is vaguely aware that his weapons have been turned against him, that culture and civiltà, have misled him into this blind alley where scientific barbarism is nothing but a very understandable reaction. Please excuse my vocabulary."

"Klages has already said all of that," said Gregorovius. -- From Chapter 99 of "Hopscotch" by Julio Cortázar

Ludwig Klages is primarily responsible for providing the philosophical foundations for the pan-Romantic conception of man that we now find among many thinkers in different scientific disciplines, for example, Edgar Dacqué, Leo Frobenius, C. G. Jung, Hans Prinzhorn, Theodor Lessing, and, to a certain extent, Oswald Spengler. -- From "Man’s Place in Nature" by Max Scheler

In the field of scientific psychology, Klages towers over all of his contemporaries, including even the academic world’s most renowned authorities. -- Oswald Spengler

"The Spirit as Adversary of the Soul" by Ludwig Klages ranks with Heidegger’s "Being and Time" and Hartmann’s "The Foundation of Ontology" as one of the three greatest philosophical achievements of the modern epoch. -- Erich Rothacker

Klages is a fascinating phenomenon, a scientist of the highest rank, whom I regard as the most important psychologist of our time. -- Alfred Kubin

Ludwig Klages is renowned as the brilliant creator of profound systems of expression-research and graphology, and his new book, entitled "Concerning the Cosmogonic Eros," possesses such depth of psychological insight and so rich and fructifying an atmosphere, that it moved me far more deeply than I have ever been moved by the writings of men like Spengler and Keyserling. In the pages of this book on the "Cosmogonic Eros," Klages almost seems to have found the very words with which to speak that which has hitherto been considered to be beyond the powers of speech. -- Hermann Hesse

When we survey the philosophical critiques of Nietzsche’s thought that have been published thus far, we conclude that the monograph written by Ludwig Klages, "The Psychological Achievements of Nietzsche," can only be described as the towering achievement. -- Karl Löwith

DURING THE CLOSING YEARS of the 19th century, the limitations and inadequacies of the superficial positivism that had dominated European thought for so many decades were becoming increasingly apparent to critical observers. The wholesale repudiation of metaphysics that Tyndall, Haeckel and Büchner had proclaimed as a liberation from the superstitions and false doctrines that had misled benighted investigators of earlier times, was now seen as having contributed significantly to the bankruptcy of positivism itself. Ironically, a critical examination of the unacknowledged epistemological assumptions of the positivists clearly revealed that not only had Haeckel and his ilk been unsuccessful in their attempt to free themselves from metaphysical presuppositions, but they had, in effect, merely switched their allegiance from the grand systems of speculative metaphysics that had been constructed in previous eras by the Platonists, medieval scholastics, and post-Kantian idealists whom they abominated, in order to adhere to a ludicrous, ersatz metaphysics of whose existence they were completely unaware.

DURING THE CLOSING YEARS of the 19th century, the limitations and inadequacies of the superficial positivism that had dominated European thought for so many decades were becoming increasingly apparent to critical observers. The wholesale repudiation of metaphysics that Tyndall, Haeckel and Büchner had proclaimed as a liberation from the superstitions and false doctrines that had misled benighted investigators of earlier times, was now seen as having contributed significantly to the bankruptcy of positivism itself. Ironically, a critical examination of the unacknowledged epistemological assumptions of the positivists clearly revealed that not only had Haeckel and his ilk been unsuccessful in their attempt to free themselves from metaphysical presuppositions, but they had, in effect, merely switched their allegiance from the grand systems of speculative metaphysics that had been constructed in previous eras by the Platonists, medieval scholastics, and post-Kantian idealists whom they abominated, in order to adhere to a ludicrous, ersatz metaphysics of whose existence they were completely unaware.

The alienation of younger thinkers from what they saw as the discredited dogmas of positivism and materialism found expression in the proliferation of a wide range of philosophical schools, whose adherents had little in common other than the will to revolt against outmoded dogma. "Back to Kant!" became the battle-cry of the neo-Kantians at Marburg. "Back to the things themselves!" proclaimed the "phenomenologist" Edmund Husserl; there were "neo-positivists," "empirio-critical" thinkers, and even the invertebrate American ochlocracy lent its cacaphonous warblings to the philosophical choir when William James proclaimed his soothing doctrine of "Pragmatism," with which salesmen, journalists, and other uncritical blockheads have stupefied themselves ever since.

A more substantial and significant revolt, however, emerged from another quarter altogether when several independent scholars began to re-examine the speculative metaphysical systems of the "philosophers of nature" who had flourished during the Romantic Period. Although the astonishing creativity of these men of genius had been forgotten whilst positivism and materialism ruled the roost, of course, men like Nietzsche, Burckhardt, and Bachofen had preserved elements of the Romantic heritage and had thereby, as it were, already prepared the soil in which younger men would sow the precious seed of a Romantic Revival. By the turn of the 20th century the blossoms had emerged in the form of the philosophers of the "vitalist" school. In France, Henri Bergson became the leading proponent of philosophical vitalism, and his slogan of élan vital as well as his doctrine of évolution créatrice thrilled audiences in the salons as well as in the university lecture halls. In Hungary, the astonishingly gifted philosopher and physicist, Melchior Palágyi—a thinker of an altogether higher order than the superficial Bergson—conducted profound research into celestial mechanics, which clearly anticipated the theory of relativity; he developed the theory of "virtual" movement; and his critical powers enabled him to craft a definitive and withering refutation of Husserl’s pseudo-phenomenology, and his insights retain their validity even now in spite of the oblivion to which the disciples of Husserl have consigned them.

In the German-speaking world the doctrines of Lebensphilosophie, or "philosophy of life," achieved academic respectability when Wilhelm Dilthey became their spokesman. Sadly, candor demands that we draw the reader’s attention to the troubling fact that it was Dilthey who inaugurated a disastrous trend that was to be maintained at German universities for the next hundred years by such able obfuscators and logomachs as Heidegger and his spawn, for, to put it as charitably as possible, Dilthey was the first significant German philosopher to achieve wide renown in spite of having nothing significant to say (that is why, perhaps, Dilthey and Heidegger furnish such mountains of grist for the philosophical proles who edit and annotate and comment and publish and—prosper).

Among these "philosophers of life," there were "amalgamists," among whom we find Hans Driesch, who sabotaged his own project by indulging in futile attempts to combine the irreconcilable doctrines of Kantian idealism and vitalism in his theory of the "entelechy," which, although he proclaimed it to be a uniquely vitalistic notion, is always analyzed mechanistically and atomistically in his expositions. The profound speculative metaphysics of Houston Stewart Chamberlain also succumbed to the Kantian infection, for even Chamberlain seems to have been blind to the ineluctable abyss that divides vitalism and Kantianism.

Finally, and most significantly, we encounter the undisputed master-spirit of the "vitalist" school in the German world, the philosopher and polymath Ludwig Klages, whose system of "biocentric" metaphysics displays a speculative profundity and a logical rigor that no other vitalist on the planet could hope to equal.

The Early Years

Ludwig Klages was born on December 10, 1872, in the northern German city of Hannover. He seems to have been a solitary child, but he developed one intense friendship with a class-mate named Theodor Lessing, who would himself go on to achieve fame as the theorist of "Jewish Self-Hatred," a concept whose origins Lessing would later trace back to passionate discussions that he had had with Klages during their boyhood rambles on the windswept moors and beaches of their Lower Saxon home.

In 1891 he received his "Abitur," and immediately journeyed to Leipzig to begin his university studies in Chemistry and Physics. In 1893, he moved to Munich, where he would live and work until the Great War forced him into Swiss exile in 1915.

Klages continued his undergraduate studies in Chemistry and Physics during the day, but at night he could usually be found in the cafés of Schwabing, then as now the Bohemian district of Munich. It was in Schwabing that he encountered the poet Stefan George and his "circle." George immediately recognized the young man’s brilliance, and the poet eagerly solicited contributions from Klages, both in prose and in verse, to his journal, the Blätter für die Kunst.

Klages also encountered Alfred Schuler (1865-1923), the profoundly learned Classicist and authority on ancient Roman history, at this time. Schuler was also loosely associated with the George-circle, although he was already becoming impatient with the rigidly masculine, "patriarchalist" spirit that seemed to rule the poet and his minions. Klages eventually joined forces with Schuler and Karl Wolfskehl, an authority on Germanistics who taught at the University of Munich, to form the Kosmische Runde, or "Cosmic Circle," and the three young men, who had already come under the influence of the "matriarchalist" anthropology of the late Johann Jakob Bachofen, soon expressed their mounting discontent with George and his "patriarchal" spirit. Finally, in 1904, Klages and Schuler broke with the poet, and the aftermath was of bitterness and recrimination "all compact." Klages would in later years repudiate his association with George, but he would revere Schuler, both as a man and as a scholar, to the end of his life.

The other crucial experience that Klages had during this last decade of the old century was his overwhelming love affair with Countess Franziska zu Reventlow, the novelist and Bohemian, whose "Notebooks of Mr. Lady" provides what is, perhaps, the most revealing—and comical—rendition of the turbulent events that culminated in the break between the "Cosmic Circle" and the George-Kreis; Wolfskehl, who was himself an eyewitness to the fracas, held that, although Franziska had called the book a novel, it was, in fact, a work of historical fact. Likewise, the diaries of the Countess preserve records of her conversations with Klages (who is referred to as "Hallwig," the name of the Klages-surrogate in her "Mr. Lady": she records Klages telling her that "There is no ‘God’; there are many gods!" At times "Hallwig" even frightens her with oracular allusions to "my mystical side, the rotating Swastika" and with his prophecies of inevitable doom). When the Countess terminated the liaison, Klages, who suffered from serious bouts with major depression throughout his long life, experienced such distress that he briefly contemplated suicide. Fate, of course, would hardly have countenanced such a quietus, for, as Spengler said, there are certain destinies that are utterly inconceivable—Nietzsche won’t make a fortune at the gambling tables of Monte Carlo, and Goethe won’t break his back falling out of his coach, he remarks drily.

And, we need hardly add, Klages will not die for love…

On the contrary: he will live for Eros.

Works of Maturity

After the epoch-making experiences of the Schwabing years, the philosopher’s life seems almost to assume a prosaic, even an anticlimactic, quality. The significant events would henceforth occur primarily in the thinker’s inner world and in the publications that communicated the discoveries that he had made therein. There were also continuing commitments on his part to particular institutions and learned societies. In 1903 Klages founded his "Psychodiagnostic Seminars" at the University of Munich, which swiftly became Europe's main center for biocentric psychology. In 1908, he delivered a series of addresses on the application of "Expression Theory" (Ausdruckskunde) to graphological analysis at one such seminar.

In 1910, in addition to the book on expression-theory, Klages published the first version of his treatise on psychology, entitled Prinzipien der Charakterologie. This treatise was based upon lectures that Klages had delivered during the previous decade, and in its pages he announced his discovery of the "Id," which has popularly, and hence erroneously, for so long been attributed to Freud. He came in personal contact with several members of rival psychological schools during this period, and he was even invited—in his capacity as Europe's leading exponent of graphology—to deliver a lecture on the "Psychology of Handwriting" to the Wednesday Night Meeting of the Freudian "Vienna Society" on the 25th of October in 1911.

The philosopher also encountered the novelist Robert Musil, in whose masterpiece, Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften, Klages appears—in caricatured form, of course—as the eerie and portentous prophet Meingast, that "messenger from Zarathustra’s mountain." The novelist seems to have been most impressed by the philosopher’s speculations in Vom kosmogonischen Eros concerning the ecstatic nature of the "erotic rapture" and the Klagesian "other condition" (andere Zustand). Paradoxically, however, Musil’s novel presents Meingast [Klages] as a manic and domineering worshiper of power, which is quite strange when one considers that Klages consistently portrays the Nietzschean "Will to Power" as nothing but a modality of hysteria perfectly appropriate to our murderous age of militarism and capitalism. Anyone familiar with the withering onslaught against the will and its works which constitutes the section entitled Die Lehre der Wille in Klages’s Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele must, in addition, feel a certain amazement at Meingast’s ravings concerning the necessity for a "determined will"! Another familiar (and depressing) insight into the resistance mounted by even sympathetic writers to the biocentric philosophy can be derived from a perusal of Musil’s Tagebücher, with its dreary and philistine insistence that the Klagesian rapture must at all costs be constrained by Geist, by its pallid praise for a "daylight mysticism," and so on. Admittedly, Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften will remain an astonishing and beautifully-crafted masterpiece of 20th Century belles lettres, in spite of its author’s jejune "philosophical" preachments.

During this same period, Klages rediscovered the late-Romantic philosopher Carl Gustav Carus, author of the pioneering Psyche: Zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der Seele ("Psyche: Towards a Developmental History of the Soul") in which the unconscious is moved to center-stage (sadly, the Jung-racket falsely credits their master with this discovery). The very first sentence of this work indicates the primacy attributed by Carus to the unconscious: "The key to the understanding of the conscious life of the soul lies in the realm of the unconscious." During the Romantic Revival that took place in the Germany of th 1920s, Klages would edit a new, abridged version of Psyche, in which Carus is purged of his logocentric and Christian errors. Klages, however, fully accepts Carus’s definition of the soul as synonymous with life, a formulation that he rates as epochally significant. He finds Carus’s statement to be as profound as the aphorism of Novalis in which he locates the soul at the point of contact between the inner and outer worlds.

In 1913, Klages presented his Zur Theorie und Symptomatologie des Willens to the Vienna Congress of International Societies for Medical Psychology and Psychotherapy. In that same year, Klages delivered an address entitled Mensch und Erde to a gathering of members of the German Youth Movement. This seminal work has recently received its due as the "foundational" document of the "deep ecology" movement when a new edition was published in 1980 in coordination with the establishment of the German "Green" political party.

In his Heidnische Feuerzeichen, which was completed in 1913, although it would not be published in book form until 1944, Klages has some very perceptive remarks on consciousness, which he regards as always effect and never cause. He cautions us to realize that, because our feelings are almost always conscious, we tend to attribute far too much importance to them. Reality is composed of images [Bilder] and not feelings, and the most important idea that Klages ever developed is his conception of the "actuality of the images" [Wirklichkeit der Bilder]. He also savages the insane asceticism of Christianity, arguing that a satisfied sexuality is essential for all genuine cosmic radiance. Christ is to be detested as the herald of the annihilation of earth and the mechanization of man.

The pioneering treatise on "expression theory," the Ausdruckskunde und Gestaltungskraft, also appeared in 1913. The first part of his treatise on the interpretation of dreams (Vom Traumbewusstsein) appeared in 1914, but war soon erupted in Europe, swiftly interrupting all talk of dreams. Sickened by the militaristic insanity of the "Great War," Klages moved to neutral Switzerland. In 1920 he made his last move to Kilchberg, near Zurich, Switzerland, where he would spend the rest of his life.

The first substantial excerpt from the treatise that would eventually become his Hauptwerk (Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele) was published as Geist und Seele in a 1916 number of the journal Deutsche Psychologie. He soon turned his attention to the more mundane matter of the contemporary world situation, and in 1918, concerned by the spread of "One World"-humanitarianism and other pernicious forms of "humanism," Klages published the classic Brief über Ethik, in which he re-emphasized his opposition to all ethical and individualistic attempts to improve the world. The modern world’s increasing miscegenation has hatched out a horde of mongrels, slaves, and criminals. The world is falling under the dominion of the enemies of life, and it matters not a bit whether the ethical fanatic dubs his hobbyhorse Wille, Tat, Logos, Nous, Idee, Gott, the "Supreme Being," reines Subjekt, or absolutes Ich: these phrases are merely fronts behind which spirit, the eternal adversary of life, conducts her nefarious operations. Only infra-human nature, wherein dwells a principle of hierarchical order in true accord with the laws of life, is able to furnish man with genuine values. The preachers of morality can only murder life with their prohibitive commands so stifling to the soul’s vitality. As Klages’s disciple Hans Prinzhorn cautions us, the vital order "must not be falsified, according to the Judæo-Christian outlook, into a principle of purposefulness, morality, or sentimentality." The "Letter on Ethics" urges us to avoid all such life-hostile values, and to prize instead those moments when we allow our souls to find warmth in the love which manifests itself as adoration, reverence, and admiration. The soul’s true symbol is the mother with her beloved child, and the soul’s true examples are the lives of poets, heroes, and gods. Klages concludes his sardonic "Letter" by informing the reader, in contemptuous and ironical tones, that if he refuses to respond to these exemplary heroes, he may then find it more congenial to sit himself down and listen, unharmed, to a lecture on ethics!

In 1921, Klages published his Vom Wesen des Bewusstseins, an investigation into the nature of consciousness, in which the ego-concept is shown to be neither a phenomenon of pure spirit nor of pure life, but rather a mere epiphenomenal precipitate of the warfare between life and spirit. In this area, Klages’s presentation invites comparion with the Kantian exposition of "pure subjectivity," although, as one might expect, Klages assails the subjectivity of the ego as a hollow sham. The drive to maximize the realm of ego, regardless of whether this impulse clothes itself in such august titles as "The Will to Power" (Nietzsche), the "Will to Live" (Schopenhauer), or the naked obsession with the "Ego and its Own" (Stirner), is merely a manifestation of malevolent Geist. Klages also ridicules the superficiality of William James’s famous theory of "stream of consciousness," which is subjected to a withering critical onslaught. After James’s "stream" is conclusively demolished, Klages demonstrates that Melchior Palágyi’s theory more profoundly analyzes the processes whereby we receive the data of consciousness. Klages endorses Palágyi’s account of consciousness in order to establish the purely illusory status of the "stream" by proving conclusively that man receives the "images" as discrete, rhythmically pulsating "intermittencies."

We should say a few words about the philosopher whose exposition of the doctrine of consciousness so impressed Klages. Melchior Palágyi [1859-1924] was the Hungarian-Jewish Naturphilosoph who was regarded as something of a mentor by the younger man, ever since 1908, when they first met at a learned conference. Like Klages, Palágyi was completely devoted to the thought-world of German Romantic Naturphilosophie. Klages relied heavily on this thinker’s expert advice, especially with regard to questions involving mechanics and physics, upon which the older man had published outstanding technical treatises. The two men had spent many blissful days together in endless metaphysical dialogue when Palagyi visited Klages at his Swiss home shortly before Palágyi’s death. They were delighted with each other’s company, and reveled even in the cut and thrust of intense exchanges upon matters about which they were in sharp disagreement. Although this great thinker is hardly recalled today even by compilers of "comprehensive" encyclopedias, Palagyi’s definitive and irrefutable demolition of Edmund Husserl’s spurious system of "phenomenology" remains one of the most lethal examples of philosophical adversaria to be found in the literature. Palágyi, who was a Jew, had such a high opinion of his anti-semitic colleague, that when Palágyi died in 1925, one of the provisions of his will stipulated that Ludwig Klages was to be appointed as executor and editor of Palágyi’s posthumous works, a task that Klages undertook scrupulously and reverently, in spite of the fact that the amount of labor that would be required of him before the manuscripts of his deceased colleague could be readied for publication would severely disrupt his own work upon several texts, most especially the final push to complete the three-volume Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele. One gets the impression that Klages felt the task that had been imposed upon him was also one of the highest honors, and Klages’s high regard for Palágyi’s thought can best be appreciated when we realize that among the numerous thinkers and scholars whose works are cited in his collected works, the contemporary philosopher who is cited most frequently, and at the greatest length, is none other than Melchior Palágyi.

Klages published his influential anthropological-historical study, Vom kosmogonischen Eros, in 1922, and in the Selbstbericht which serves as an introduction to this work he details the points of agreement and the points of disagreement between his views and those of Friedrich Nietzsche.

In 1923 Klages published his Vom Wesen des Rhythmus (a revised edition of which would be issued in 1934). Then in 1925, two fervent admirers of Klagesian biocentrism—one was Niels Kampmann who would go on to publish some of Klages’s works in book form—brought out the first issue of a scholarly journal, the brilliant Zeitschrift für Menschenkunde, which would continue to publish regularly until the rigors of war eventually forced the editors to suspend publication in 1943 (eight years after the end of the war, the journal began a new career in 1953.)

A revised and enlarged edition of the treatise on characterology appeared in 1926 with the new title Die Grundlagen der Charakterkunde. Klages also published Die psychologischen Errungenschaften Nietzsches in this same year, a work which, more than a quarter of a century after its initial appearance, the Princeton-based Nietzsche-scholar Walter Kaufmann—surely no friend to Klages!—would nevertheless admire greatly, even feeling compelled to describe Klages’s exegesis of Nietzsche’s psychology as "the best monograph" ever written on its subject.

A collection of brief essays entitled Zur Ausdruckslehre und Charakterkunde, was brought out by Kampmann in 1927; many of them date from the early days of the century and their sheer profundity and variety reinforce our conviction that Klages was a mature thinker even in his twenties.

The first two volumes of his magnum opus, the long-awaited and even-longer pondered, Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele, finally appeared in 1929. One year later the Graphologisches Lesebuch appeared, and the third and final volume of Der Geist hit the book-shops in 1932, a year that seems to have been a very busy one indeed for our polymathic philosopher, since he also found time to revamp his slender monograph entitled Goethe als Naturforscher, a short work that can only be compared to the Goethe-books of H. S. Chamberlain and Friedrich Gundolf for breadth of scholarship and insight into the creativity of a great seer and scientist (this study was a revised edition of a lecture that had originally been published in the Jahrbuch des Freien Deutschen Hochstifts in 1928).

Hans Prinzhorn, the psychologist, translator of D. H. Lawrence and compiler of the landmark treatise on the artistry of the mentally-disturbed, had long been a friend and admirer of Klages, and in 1932 he organized the celebration for the sixtieth birthday of the philosopher. The tributes composed the various scholars who participated in this event were collected and edited by Prinzhorn for publication in book-form, with the title Festschrift zum 60. Geburtstag.

National Socialist Germany, World War II, and their Aftermath

Shortly after the NSDAP seized power at the beginning of 1933, one of Klages’s disciples established the Arbeitskreises für biozentrisches Forschung. At first the German disciples of Klages were tolerated as harmless philosophical eccentrics, but soon the Gestapo began keeping a close eye on members and contributors to the biocentric circle’s house organ Janus. By 1936 the authorities forcibly shut down the journal and from that time until the fall of the regime, the Gestapo would periodically arrest and question those who had been prominent members of the now-defunct "circle." From 1938 onwards, when Reichsleiter Dr. Alfred Rosenberg delivered a bitter attack on Klages and his school in his inaugural address to the summer semester at the University of Halle, the official party spokesmen explicitly and repeatedly condemned Klages and his friends as enemies of the National Socialist Weltanschauung.

Klages traveled widely during the 1930s, and he especially enjoyed his journeys to Greece and Scandinavia. In 1940 he published Alfred Schuler: Fragmente und Vorträge. Aus dem Nachlass, his edition of Alfred Schuler’s literary remains. The "Introduction" to the anthology is a voluminous critical memoir in which Klages rendered profound tribute to his late mentor. However, in the pages of that introduction, Klages introduced several statements critical of World-Jewry that were to dog his steps for the rest of his life, just as they have compromised his reputation after his death. Unlike so many ci-devant "anti-semites" who prudently saw the philo-semitic light in the aftermath of the war, however, Klages scorned to repudiate anything that he had said on this or any other topic. He even poured petrol on the fires by voicing his conviction that the only significant difference between the species of master-race nonsense that was espoused by the National Socialists and the variety adopted by their Jewish enemies was in the matter of results: Klages blandly proclaims that the Jews, after a two-thousand year long assault on the world for which they felt nothing but hatred, had actually won the definitive victory. There would be no re-match. He sneered at all the kow-towing to Jewry that had already become part of the game in the immediate post-war era, because, he reasoned, even as a tactical ploy such sycophantic behavior has always doomed itself to complete and abject failure.

In December of 1942, the official daily newspaper of the NSDAP, the Völkischer Beobachter, published a vicious and ungracious attack on Klages in the edition that appeared on the philosopher’s 70th birthday. During the war years, Klages began compiling notes for a projected full-dress autobiography that was, sadly, never completed. Still, the notes are fascinating in their own right, and are well worth consulting by the student of his life and thought.

In 1944, Barth of Leipzig published the Rhythmen und Runen, a self-edited anthology of Klages’s prose and verse writings stemming from the turn of the century (unfortunately, however, when Bouvier finally brought out their edition of his "Collected Works," which began to appear in the mid-1960s, Rhythmen und Runen, along with the Stefan George-monograph and such provocative pieces as the "Introduction" to Schuler’s writings, were omitted from the set, in spite of the fact that the original prospectus issued to subscribers announced that these works would, in fact, be included. The reasons for this behavior are—need we say?—quite obvious).

When the war ended, Klages began to face true financial hardship, for his market, as well as his publishers, had been devastated by the horrific saturation bombing campaign with which the democratic allies had turned Germany into a shattered and burnt-out wasteland. Klages also suffered dreadfully when he learned that his beloved sister, Helene, as well as her daughter Heidi, the philosopher’s niece, had perished in the agony of post-war Germany, that nightmare world wherein genocidal bestiality and sadistic cruelty were dealt out by occupying forces with a liberal hand in order most expeditiously to "re-educate" the survivors of the vanquished Reich. Although Klages had sought permission from the occupying authorities to visit his sister as she lay dying, his request was ignored (in fact, he was told that the only civilians who would be permitted to travel to Germany were the professional looters who were officially authorized to rob Germany of industrial patents and those valiant exiles who had spent the war years as literary traitors, who made a living writing scurrilous and mendacious anti-German pamphlets). This refusal, followed shortly by his receipt of the news of her miserable death, aroused an almost unendurable grief in his soul.

His spirits were raised somewhat by the Festschrift that was organized for his 75th birthday, and his creative drive certainly seemed to be have remained undiminished by the ravages of advancing years. He was deeply immersed in the philological studies that prepared him to undertake his last great literary work, the Die Sprache als Quell der Seelenkunde, which was published in 1948. In this dazzling monument of 20th century scholarship, Klages conducted a comprehensive investigation of the relationship between psychology and linguistics. During that same year he also directed a devastating broadside in which he refuted the fallacious doctrines of Jamesian "pragmatism" as well as the infantile sophistries of Watson’s "behaviorism." This brief but pregnant essay was entitled Wie Finden Wir die Seele des Nebenmenschen?

During the early 1950s, Klages’s health finally began to deteriorate, but he was at least heartened by the news that there were serious plans afoot among his admirers and disciples to get his classic treatises back into print as soon as possible. Death came at last to Ludwig Klages on July 29, 1956. The cause of death was determined to have been a heart attack. He is buried in the Kilchberg cemetery, which overlooks Lake Zurich.

Understanding Klagesian Terms

A brief discussion of the philosopher’s technical terminology may provide the best preparation for an examination of his metaphysics. Strangely enough, the relationship between two familiar substantives, "spirit" [Geist] and "soul" [Seele], constitutes the main source of our terminological difficulties. Confusion regarding the meaning and function of these words, especially when they are employed as technical terms in philosophical discourse, is perhaps unavoidable at the outset. We must first recognize the major problems involved before we can hope to achieve the necessary measure of clarity. Now Klages regards the study of semantics, especially in its historical dimension, as our richest source of knowledge regarding the nature of the world (metaphysics, or philosophy) and an unrivalled tool with which to probe the mysteries of the human soul (psychology, or characterology [Charakterkunde]). We would be well advised, therefore, to adopt an extraordinary stringency in lexical affairs. We have seen that the first, and in many ways the greatest, difficulty that can impede our understanding of biocentric thought confronts us in our dealings with the German word Geist. Geist has often been translated as "spirit" or "mind," and, less often, as "intellect." As it happens, the translation of Hegel’s Phänomenologie des Geistes that most American students utilized in their course-work during the 1960s and 1970s was entitled "The Phenomenology of Mind" (which edition was translated with an Introduction and Notes by J. B. Bailey, and published by Harper Torchbooks, New York, 1967).

Lest it be thought that we are perversely attributing to the word Geist an exaggeratedly polysemic status, we would draw the reader’s attention to the startling fact that Rudolf Hildebrandt’s entry on this word in the Grimm Wörterbuch comprises more than one hundred closely printed columns. Hildebrandt’s article has even been published separately as a book. Now in everyday English usage, spirit (along with its cognates) and soul (along with its cognates) are employed as synonyms. As a result of the lexical habits to which we have grown accustomed, our initial exposure to a philosopher who employs soul and spirit as antonyms can be a somewhat perplexing experience. It is important for us to realize that we are not entering any quixotic protest here against familiar lexical custom. We merely wish to advise the reader that whilst we are involved in the interpretation of Klagesian thought, soul and spirit are to be treated consistently as technical philosophical terms bearing the specific meanings that Klages has assigned to them.

Our philosopher is not being needlessly obscure or perversely recherché in this matter, for although there are no unambiguous distinctions drawn between soul and spirit in English usage, the German language recognizes some very clear differences between the terms Seele and Geist, and Hildebrandt’s article amply documents the widely ramified implications of the distinctions in question. In fact, literary discourse in the German-speaking world is often characterized by a lively awareness of these very distinctions. Rudolf Kassner, for instance, tells us that his friend, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, inhabited a world of soul [Seele], not one of spirit [Geist]. In speaking of Rilke’s world as that the soul, Kassner is proclaiming the indisputable truth that Rilke’s imagination inhabits an innocent, or pagan, world, a realm that is utterly devoid of such "spiritual" baggage as "sin" and "guilt." Likewise, for Kassner, as for Rilke, the world of spirit is the realm of labor and duty, which is ruled by abstractions and "ideals." I can hardly exaggerate the significance of the spirit-soul dichotomy upon which Kassner has shed so much light in these remarks on Rilke as the man of "soul." If the reader bears their substance in mind, he will find that the path to understanding shall have been appreciably cleared of irksome obstacles.

Therefore, these indispensable lexical distinctions are henceforth to function as our established linguistic protocol. Bearing that in mind, when the reader encounters the Klagesian thesis which holds that man is the battlefield on which soul and spirit wage a war to the death, even the novice will grasp some portion of the truth that is being enunciated. And the initiate who has immersed his whole being in the biocentric doctrine will swiftly discover that he is very well prepared indeed to perpend, for instance, the characterological claim that one can situate any individual at a particular point on an extensive typological continuum at one extreme of which we situate such enemies of sexuality and sensuous joy as the early Christian hermits or the technocrats and militarists of our own day, all of whom represent the complete dominance of spirit; and at the opposite extreme of which we locate the Dionysian maenads of antiquity and those rare modern individuals whose delight in the joys of the senses enables them to attain the loftiest imaginable pinnacle of ecstatic vitality: the members of this second group, of course, comprise the party of life, whose ultimate allegiance is rendered to soul.

Before we conclude this brief digression into terminological affairs, we would advise those readers whose insuperable hostility to every form of metaphysical "idealism" compels them to resist all attempts to "place" spirit and soul as "transcendental" entities, that they may nevertheless employ our terms as heuristic expedients, much as Ampére employed the metaphor of the "swimmer" in the electric "current."

Biocentric Metaphysics in its Historical Context

Perhaps a brief summary will convey at least some notion of the sheer originality and the vast scope of the biocentric metaphysics. Let us begin by placing some aspects of this philosophical system in historical context. For thousands of years, western philosophers have been deeply influenced by the doctrine, first formulated by the Eleatic school and Plato, which holds that the images that fall upon our sensorium are merely deceitful phantoms. Even those philosophers who have rebelled against the schemes devised by Plato and his successors, and who consider themselves to be "materialists," "monists," "logical atomists," etc., reveal that have been infected by the disease even as they resist its onslaught, for in many of their expositions the properties of matter are presented as if they were independent entities floating in a void that suspiciously resembles the transcendent Platonic realm of the "forms."

Ludwig Klages, on the other hand, demonstrates that it is precisely the images and their ceaseless transformations that constitute the only realities. In the unique phenomenology of Ludwig Klages, images constitute the souls of such phenomena as plants, animals, human beings, and even the cosmos itself. These images do not deceive: they express; these living images are not to be "grasped," not to be rigidified into concepts: they are to be experienced. The world of things, on the other hand, forms the proper subject of scientific explanatory schemes that seek to "fix" things in the "grasp" of concepts. Things are appropriated by men who owe their allegiance to the will and its projects. The agents of the will appropriate the substance of the living world in order to convert it into the dead world of things, which are reduced to the status of the material components required for purposeful activities such as the industrial production of high-tech weapons systems. This purposeful activity manifests the outward operations of an occult and dæmonic principle of destruction.

Klages calls this destructive principle "spirit" (Geist), and he draws upon the teaching of Aristotle in attempting to account for its provenance, for it was Aristotle who first asserted that spirit (nous) invaded the substance of man from "outside." Klages’s interpretation of this Aristotelian doctrine leads him to conclude that spirit invaded the realm of life from outside the spatio-temporal world. Likewise, Klages draws on the thought of Duns Scotus, Occam and other late mediæval English thinkers when he situates the characteristic activity of spirit in the will rather than in the intellect. Completely original, however, is the Klagesian doctrine of the mortal hostility that exists between spirit and life (=soul). The very title of the philosopher’s major metaphysical treatise proclaims its subject to be "The Spirit as Adversary of the Soul" (Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele).

The indivisible body-soul unity that had constituted the living substance of man during the "primordial," or prehistoric, phase of his existence, in time becomes the focus of spirit’s war against life. Spirit severs the vital connection by thrusting itself, like the thin end of an invasive wedge, between the poles of body and soul. History is the tragic chronicle that recounts the ceaseless war that is waged by spirit against life and soul. When the ever-expanding breach between body and soul finally becomes an unbridgeable abyss, the living substance is no more, although no man can predict how long man may endure as a hollow shell or simulacrum. The ceaseless accumulation of destructive power by spirit is accompanied by the reduction of a now devitalized man to the status of a mere machine, or "robot," who soullessly regurgitates the hollow slogans about "progress," "democracy," and the delights of "the consumer society" that are the only values recognized in this world of death. The natural world itself becomes mere raw material to be converted into "goods" for the happy consumer.

A Unified System of Thought: Graphology