Certaines familles semblent vouées dès l'abord - on pourrait presque dire « abonnées » - à des destins exceptionnels. Tel fut le cas de la famille Koltchak.

Certaines familles semblent vouées dès l'abord - on pourrait presque dire « abonnées » - à des destins exceptionnels. Tel fut le cas de la famille Koltchak. Les ancêtres de l'amiral Alexandre Vassilievitch Koltchak, commandant en chef des Armées blanches de Sibérie durant la guerre civile qui suivit la révolution rouge de 1917, étaient, en fait, bosniaques. L'un d'eux, pacha de l'Empire turc, fut fait prisonnier par les Russes en 1739, alors qu'il combattait en Moldavie, et décida de devenir Cosaque et de se fixer en Russie. Toute une lignée de militaires valeureux était ainsi inaugurée.

C'est au cours de la guerre de Crimée que Vassili Koltchak, père de l'amiral et lui-même brillant officier du génie, connut une aventure hors du commun. Comme, après la prise du fort de Malakoff, des soldats français s'employaient à dégager un monceau de cadavres russes, ils s'aperçurent que l'un des « morts » respirait encore.

Vassili Koltchak se rétablit et termina sa carrière comme général, après avoir écrit un livre à succès « en captivité », sur son expérience de prisonnier de guerre.

Son fils Alexandre, né en 1872, a choisi, quant à lui, la marine et, d'emblée, sa carrière s'annonce fort brillante à plus d'un égard. Il s'est spécialisé dans les rercherches hydrographiques et océanographiques, sujets sur lesquels il publia des articles qui commencent à faire autorité.

En 1899, à l'âge de vingt-sept ans, il accompagne dans l'Arctique un célèbre explorateur polaire, le baron Toll. Il revient au bout de deux ans, Mais, en 1903, repart à la recherche du baron dont on est sans nouvelles.

Un mariage mouvementé

Cette fois, deux événements vont marquer son retour, en 1904 : le déclenchement de la guerre russo-japonaise et un mariage qui va se dérouler dans d'assez étranges conditions. S'étant rendu compte qu'il n'aurait pas le temps matériel de se rendre à Saint-Pétersbourg, où habite sa fiancée, avant de rejoindre son poste à Port-Arthur, le lieutenant de vaisseau Koltchak télégraphie à son père de lui amener la jeune fille à Irkoutsk, en Sibérie orientale. Là, la cérémonie a lieu, et, le jour même, les jeunes époux regagnent l'un Saint-Pétersbourg et l'autre Port-Arthur.

Après une congestion pulmonaire qui l'immobilise quelque temps, Koltchak prend le commandement d'un mouilleur de mines et se distingue rapidement par sa compétence et sa bravoure. Blessé, il est fait prisonnier et détenu au Japon, avant de pouvoir regagner la Russie par le Canada.

Le sabre à la mer

En 1911, il revient à l'état-major comme responsable du secteur-clé de la Baltique, poste où le trouvera la Première Guerre mondiale.

Il se distingue - en particulier par son utilisation des mines, - au point qu'il sera nommé contre-amiral dès 1915, à l'âge de quarante-trois ans, vice-amiral et commandant en chef de la flotte de la mer Noire en 1916.

Il occupe encore ce poste lorsque éclatent les troubles de 1917. Les marins mutinés envahissent la passerelle du navire amiral, cernent Koltchak et le somment de rendre le sabre d'honneur gagné durant la guerre russo-japonaise, qu'il porte à la ceinture. Calme, méprisant, le regard lointain, l'amiral détache le sabre de son ceinturon et le jette par-dessus bord.

- Ce qui est venu de la mer retourne à la mer, dit-il seulement.

Les mutins reculent, impressionnés. Néanmoins, l'amiral doit se mettre à la disposition du gouvernement provisoire de Kerenski, qui, se méfiant de cet officier par trop intransigeant, le charge, pour l'éloigner, d'une mission technique auprès du Secrétariat à la Marine des Etats-Unis.

Il reste plusieurs mois aux Etats-Unis, puis, au mois de novembre, le gouvernement Kerenski étant tombé, il décide de regagner la Russie en passant par le Japon. A Tokyo, il apprend l'ouverture par les Bolcheviks des pourparlers de Brest-Litovsk en fin d'un armistice avec les Allemands. Il n'est pas question pour lui de servir un gouvernement qui déserte ses alliés en pleine guerre.

Il va donc trouver l'ambassadeur de Grande-Bretagne à Tokyo, sir Conyngham Greene, et lui propose, conformément à son devoir d'officier russe, d'aller combattre « si possible sur le front occidental, dans les troupes terrestres et, si nécessaire, comme simple soldat. »

De Kharbine à Orusk

L'ambassadeur britannique considère, à juste titre, que l'emploi d'un personnage de cette qualité à un rang obscur serait un incroyable gaspillage. Il télégraphie en ce sens à Londres, et, en janvier 1918, Koltchak est invité à rejoindre en Mésopotamie la mission militaire spéciale commandée par l'étonnant général Dunsterville - celui-là même qui servit de modèle à Kipling dans « Stalky and Co ».

Mais, faisant escale à Singapour, l'amiral y reçoit un message des Britanniques lui demandant de se mettre en rapport de toute urgence avec le prince Koudatchev, ambassadeur de Russie à Pékin, afin de se joindre aux dirigeants du Chemin de Fer de l'Est chinois, en Mandchourie. Il accepte avec beaucoup de réticence, pensant qu'on veut le mettre ainsi sur la touche en tant que combattant, mais se rend à Pékin pour être finalement expédié à Kharbine, au mois de mai, avec mission de réorganiser les troupes russes quelque 3.000 hommes - du Chemin de Fer.

Le climat d'intrigue, de chaos et de corruption qu'il trouve à Kharbine ne fait rien pour dissiper la méfiance initiale de l'amiral. Les Japonais, dirigés par le général Nakajima, le chef de leur mission militaire, contrôlent le territoire et tirent les ficelles. Koltchak ne l'admet pas, pas plus qu'il n'admet les prétentions du chef cosaque Semenov à se tailler un royaume personnel en Mandchourie.

Finalement, au mois de juillet, l'amiral se rend personnellement à Tokyo pour tirer la situation au clair avec le haut commandement japonais. Il n'obtient que des réponses dilatoires qui achèvent de l'exaspérer. Ce seront les Britanniques, une fois de plus, qui feront appel à lui. Afin qu'il se rende en Sibérie, où s'est installé un directoire politique pour le moins mélangé, et où une remise en ordre serait, de toute évidence, nécessaire. C'est le 13 octobre que l'amiral arrive par le Transsibérien à Omsk, où siège le gouvernement provisoire en question. On le nomme aussitôt ministre de la Guerre et de la Marine, mais il ne tarde pas à se rendre compte qu'un gigantesque coup de balai est nécessaire dans cet endroit où règnent en maîtres le marché noir et la gabegie, et où les troupes, mal encadrées et encore plus mal commandées, ont tendance à plier devant les offensives des Rouges.

Le dit coup de balai aura lieu dans la nuit du 17 au 18 novembre 1918.

En cette nuit, un détachement militaire, comprenant notamment de jeunes officiers, vient arrêter trois membres socialistes du directoire, dont le président Avksentiev, pour les conduire à la frontière. Le reste du directoire se réunit à l'aube et prononce sa propre dissolution, en demandant à Koltchak d'assumer le pouvoir suprême.

L'amiral met plusieurs heures à se laisser convaincre, mais accepte finalement en protestant de son absence totale d'esprit partisan dans le domaine politique.

« Je me fixe comme objectifs essentiels, proclame-t-il, la création d'une armée efficace, la victoire sur le bolchevisme et le rétablissement de l'ordre et de la légalité afin que le peuple puisse choisir librement et sans aucune entrave la forme de gouvernement répondant à ses vœux. »

Par moins 45 degrés

Le coup d'Etat est, dans l'ensemble, fort bien accueilli par la population, lasse de la corruption et de l'incapacité du défunt directoire. Il est également vu d'un œil très favorable par les Britanniques de la mission militaire du général Knox. Mais, du coup, il se heurte immédiatement à la méfiance et à l'hostilité du calamiteux général Janin, chef de la mission militaire française. Atteint du délire de la conspiration, cet officier général, dont la seule blessure de guerre répertoriée est une luxation de l'épaule gauche sur un quai de gare, veut à toutes forces voir « la main de la perfide Albion » derrière l'intervention de Koltchak, qu'il prend aussitôt en grippe. Il ne veut pas en démordre et son obstination maladive aboutira à livrer la Sibérie aux Rouges.

En revanche, l'accession au pouvoir de l'amiral rallie tous les suffrages du général Dénikine et de l'Armée blanche du sud de la Russie.

Dès le mois de décembre 1918, Koltchak fait reprendre l'offensive contre les Bolcheviques, avec d'appréciables succès. La jeune armée sibérienne, malgré les carences de son équipement, se bat avec brio, réussissant sur certains points du front de huit cents kilomètres sur lequel elle est engagée, à avancer de trente-cinq kilomètres par jour, par un froid de -45°. Des chefs militaires de haute valeur s'y révèlent, comme le jeune colonel Kappel, bientôt nommé général.

Mais l'amiral doit faire face à bien des problèmes. Le premier est celui de sa santé ; atteint d'une affection pulmonaire presque chronique, il est miné par la fièvre, sans, pour autant, ralentir son activité. De plus, à Omak, le désordre et le marché noir ont recommencé à sévir. Le 21 décembre, une tentative de soulèvement socialiste a été aisément jugulée par l'armée, mais les intrigues se poursuivent.

Le plus inquiétant de tout est l'attitude de la Légion tchèque, qui avait assuré, au début, une partie de l'effort militaire contre les Rouges. Cette légion avait toute une histoire. Elle avait été constituée à l'origine par Kerensky avec des Tchèques ayant servi, contraints et forcés, dans l'armée austro-hongroise et, faits prisonniers par les Russes, ayant accepté de reprendre les armes dans l'autre camp.

En mars 1918, les Bolcheviques avaient signé un accord les remettant à la disposition des Alliés. Ils devaient être acheminés avec leurs armes vers Vladivostok pour y être embarqués à destination du front occidental. Mais, en mai, alors que les trains les transportant se dirigeaient vers l'Oural, les Rouges avaient tenté de les désarmer, et de violents incidents avaient éclaté dans plusieurs gares, et notamment dans celle de Tcheliabinsk. Sur quoi, ayant mis les gardes rouges en déroute, les Tchèques avaient rejoint les forces antibolcheviques de Sibérie.

Mais ces soldats tchèques sont - à de remarquables exceptions près, comme le capitaine Rudolf Gaïda, devenu général russe à moins de trente ans - des « corps étrangers » dans les armées blanches. Beaucoup se réclament du gouvernement en exil social-démocrate fondé sous la protection des Alliés par Masaryk, qui considère Koltchak et les siens comme « réactionnaires ». Et, surtout, ils sont placés sous le commandement théorique du général Janin.

Lénine découragé

Dès le mois de décembre, ils doivent être relevés sur le front occidental et sont affectés à la garde du chemin de fer transsibérien entre Tcheliabinsk et le lac Baïkal.

Pourtant, au mois de mars 1919, l'offensive de l'armée sibérienne se poursuit avec un plein succès. Elle menace Kazan, et son objectif principal est bel et bien devenu Moscou. En avril, les troupes de Koltchak, qui progressent sur un front de trois cents kilomètres, sont à moins de six cents kilomètres de la capitale.

Le 14 mai, les Alliés adressent à l'amiral un télégramme où ils se déclarent prêts, contre certaines garanties politiques, à tenir le gouvernement d'Omsk comme représentant l'ensemble de la Russie, une assemblée constituante devant être convoquée« dès l'arrivée à Moscou ».

Koltchak répond favorablement, en faisant tenir un double de sa correspondance à Dénikine, qui, le 30 mai, dans un ordre du jour daté d'Eksterinoder, reconnaît spontanément l'autorité de l'amiral « comme le chef suprême du gouvernement russe et le commandant en chef de toutes les armées russes ».

Malgré les tergiversations des Alliés - et, en particulier, il faut bien le dire, des Français la partie semble presque gagnée pour les Blancs. D'autant qu'au Sud, les troupes de Dénikine ; passées, le 2 mars, à une offensive ayant connu, deux mois durant, un sort incertain, ont fini par s'imposer - à quarante-cinq mille contre cent cinquante mille Rouges - et avancent de telle manière qu'une jonction avec Koltchak est envisagée.

C'est au point qu'à Moscou, Lénine se laisse aller à une déclaration pieusement tue, maintenant, par les historiographes marxistes :

« C'est entendu, nous avons raté notre coup. Mais notre grande réussite peut se résumer par une comparaison capitale : à Paris, la Commune avait tenu quelques jours. En Russie, elle aura tenu quelques mois... »

Il est vrai qu'à la différence de son compère Trotski, toujours tenace, combatif et courageux, Lénine était facilement lâche devant l'événement comme il le montra aussi bien à Pétrograd en 1917 que lors de l'offensive du général Ioudénitch, commandant l'Armée blanche du nord-ouest, en octobre 1919. Mais sa réaction n'en demeure pas moins significative.

Malheureusement, la situation ne tarde pas à se dégrader sur le front tenu par les troupes sibériennes. A la fin du mois de mai 1919, alors que la victoire semblait en vue, la progression est stoppée. Puis on commence à reculer devant des forces bolcheviques considérablement renforcées et, surtout, mieux équipées et mieux ravitaillées.

L'Armée blanche de Sibérie a, en effet, des lignes de communication dangereusement étirées. Et si, depuis quelque temps, des navires alliés ont commencé à débarquer du matériel à Vladivostok, son acheminement jusqu'à la zone du front est extrêmement difficile, long et hasardeux.

En juin, l'armée sibérienne du centre doit se replier, et l'armée du nord, commandée par Gaïda, est contrainte de suivre le mouvement pour n'être pas prise à revers sur son flanc gauche. Durant tout l'été, la retraite se poursuit.

Face aux intrigues

A Omsk aussi, le temps se gâte. Les revers militaires n'ont fait qu'attiser les intrigues diverses, menées aussi bien par les politiciens locaux que par certains représentants des Alliés. Koltchak, de plus en plus miné par la maladie, continue néanmoins à se battre sur tous les fronts.

La corruption qui continue à régner parmi les fonctionnaires et même certains officiers indigne l'amiral.

Il mène une existence austère, sort peu, ne reçoit pas, n'assiste qu'aux dîners officiels et ne participe en rien à cette « dolce vita » fin de siècle qui fait tant de ravages parmi les cadres anciens et nouveaux du Gouvernement local.

Certes, il a une maîtresse, mais, bien qu'étant de notoriété publique, cette liaison unique, visiblement fondée sur des sentiments profonds, décourage les amateurs de scandales.

De plus, Anna Timireva, femme séparée d'un amiral, ancien subordonné de Koltchak, n'est pas de celles qui suscitent l'esclandre.

Le dernier convoi

Au mois d'octobre, l'offensive rouge est devenue carrément impossible à enrayer. Du côté sibérien, on ne compte plus guère que sur l'hiver pour ralentir la progression des Bolcheviques, mais l'hiver, précisément, tarde à venir cette année-là.

Le 10 novembre, les avantgardes rouges ne se trouvent plus qu'à une soixantaine de kilomètres d'Omsk, déjà abandonnée par les missions militaires alliées. Et le 14, la 27e Division rouge s'emparera de la capitale après quelques brèves escarmouches.

Le Gouvernement s'est embarqué quatre jours plus tôt en direction d'Irkoutsk. Koltchak, lui, attend le dernier moment et ne part que quelques heures avant l'entrée des troupes rouges dans les faubourgs d'Omsk.

Il a pris place avec Anna Timireva, son état-major, sa garde personnelle et quelques civils, à bord d'un extraordinaire convoi de sept trains, dont l'un, comportant, vingt-neuf fourgons clos, transporte la réserve d'or du Gouvernement russe, stockée en Sibérie. Il sera rejoint le 7 décembre, à la gare de Taïga, par le président du conseil, Victor Pepelaïev.

Ce dernier voyage de l'amiral va prendre rapidement les allures d'un véritable chemin de croix. Autour de lui, tout s'effrite et tout s'effondre. Les Tchèques, soutenus par l'éternel général Janin, sont passés de la neutralité hargneuse à un véritable sabotage.

Et, le 13 décembre, à la gare de Marinsk, ils n'hésitent pas à faire passer le convoi de Koltchak sur la voie annexe - où l'on n'avance qu'à vitesse réduite en raison de l'encombrement. Toutes les protestations envoyées par l'amiral, tant au général Janin qu'au général Syrovy, commandant les troupes tchèques, restent vaines. La trahison est en train de se consommer.

La situation est telle que, le 16 décembre, le jeune général Kappel, devenu commandant en chef des troupes sibériennes, envoie à Syrovy un télégramme furibond où il exige du général tchèque réparation immédiate. C'est en vain.

Cependant, à Irkoutsk, une organisation regroupant les socialistes révolutionnaires et les mencheviks tente un putsch. Bientôt, la ville se trouve partagée entre elle et les troupes fidèles à Koltchak...

L'amiral trahi

Le 5 janvier 1920, Janin fait transmettre à l'amiral, toujours bloqué par les Tchèques, la proposition suivante : il sera escorté jusqu'à Irkoutsk par les Alliés, mais à la condition qu'il abandonne son convoi et voyage dans un seul wagon. Après quelques hésitations, Koltchak accepte, et, le 8 janvier au soir, l'unique wagon, accroché à une locomotive, s'ébranle, avec, à son bord, l'amiral, Anna Timireva et Victor Pepelaïev. des sentinelles tchèques armées stationnent dans les couloirs. Et lorsque, le 15, le train arrive à lrkoutsk, ce sont des miliciens socialistes à brassards rouges qui occupent les quais de la gare : l'amiral Koltchak vient d'être livré à ses ennemis...

D'ailleurs, deux officiers tchèques montent à bord du train et précisent : sur ordre du général Janin, l'amiral et ses compagnons vont être remis aux « autorités politiques locales ».

Koltchak conserve son calme glacial.

- Ainsi, c'est vrai, dit-il simplement, les Alliés m'ont trahi...

Le 20 janvier, les dirigeants socialistes cèdent officiellement la place à un « Comité révolutionnaire » bolchevique, et le lendemain, 21, Koltchak est appelé à comparaître devant une « Commission d'enquête extraordinaire » de cinq membres, présidée par les commissaires politiques rouges Tchoudnovsky et Popov. Coïncidence : l'aimable général Janin est parti pour un long et mystérieux voyage...

Une double exêcution

Mais un homme n'abandonne pas la partie : Kappel.

Avec son adjoint Voitzek-Hovsky et les maigres troupes qui lui restent, il est décidé à sauver l'amiral à tout prix. Il fonce vers Irkoutsk, et, le 20 janvier, s'empare de Nijneoudinsk. Mais le jeune général a les deux jambes gelées et les poumons atteints. Il refuse de se faire évacuer et continue sa route sur un simple traîneau, sur la neige. Le 27 janvier, il expire, en passant son commandement à Voitzekhovsky.

Celui-ci est son digne successeur. Enlevant à un train d'enfer ses troupes, pourtant épuisées, il arrive le 5 février aux portes d'Irkoutsk en ayant tout balayé sur son passage.

Le jour même, la « Commission d'enquête extraordinaire », muée en tribunal avec l'approbation du soviet de Tomsk, a décidé de faire fusiller Koltchak et Victor Pepelaïev. Les deux condamnés sont amenés au bord de la rivière Outchakovka, entièrement gelée. On a creusé un trou dans la glace. Ayant récité leurs prières, les deux hommes viennent se mettre devant, le dos à la rivière. Koltchak a refusé qu'on lui bande les yeux.

Une salve, puis une seconde.

Frappés à mort, les deux corps ont basculé dans l'eau immobile. Au-dessus d'eux, la glace commence à se reformer.

_________________

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

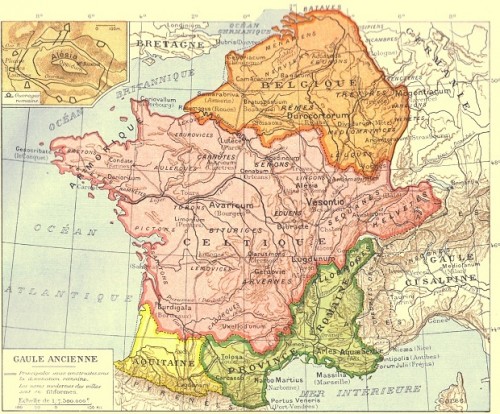

Ainsi les Wisigoths envahirent-ils dans ce but, peu après la grande migration de 406, d'abord l'Italie complètement, puis une partie de la Gaule méridionale et une partie de l'Espagne méditerranéenne. Mais, si la grande migration de 406 les servit, en épuisant les moyens militaires de l'empereur Honorius contraint, en plus, d'affronter un usurpateur en Gaule dès 407 et un autre encore en 411, elle les desservit tout autant, en suscitant une virulente réaction des Romains antigermains qui les assimilèrent aux barbares de Radagaise ou de l'invasion des Vandales-Alains-Suèves et qui, même, redoutèrent plus ces anciens fédérés que les autres envahisseurs barbares. La seconde invasion de l'Italie par Alaric et la prise de Rome, le 24 août 410, firent des Wisigoths des ennemis intolérables de l'Empire, de sorte que leur établissement dans des provinces gauloises en 418, après leur retour au statut de fédérés en 416, réalisa en partie seulement les buts de leurs sept années d'invasions.

Ainsi les Wisigoths envahirent-ils dans ce but, peu après la grande migration de 406, d'abord l'Italie complètement, puis une partie de la Gaule méridionale et une partie de l'Espagne méditerranéenne. Mais, si la grande migration de 406 les servit, en épuisant les moyens militaires de l'empereur Honorius contraint, en plus, d'affronter un usurpateur en Gaule dès 407 et un autre encore en 411, elle les desservit tout autant, en suscitant une virulente réaction des Romains antigermains qui les assimilèrent aux barbares de Radagaise ou de l'invasion des Vandales-Alains-Suèves et qui, même, redoutèrent plus ces anciens fédérés que les autres envahisseurs barbares. La seconde invasion de l'Italie par Alaric et la prise de Rome, le 24 août 410, firent des Wisigoths des ennemis intolérables de l'Empire, de sorte que leur établissement dans des provinces gauloises en 418, après leur retour au statut de fédérés en 416, réalisa en partie seulement les buts de leurs sept années d'invasions.