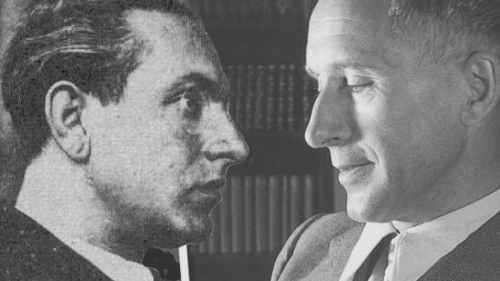

Luc-Olivier d'Algange:

L'œil du cyclone

Julius Evola, Ernst Jünger

« Comme Jack London, et divers autres, y compris Ernst Jünger à

ses débuts, des individualités isolées se vouèrent à l'aventure, à

la recherche de nouveaux horizons, sur des terres et des mers

lointaines, alors que, pour le reste des hommes, tout semblait

être en ordre, sûr et solide et que sous le règne de la science

on célébrait la marche triomphale du progrès, à peine troublée

par le fracas des bombes anarchistes. »

Julius Evola

« Ta répugnance envers les querelles de nos pères avec nos grands

pères, et envers toutes les manières possibles de leur trouver une

solution, trahit déjà que tu n'as pas besoin de réponses mais d'un

questionnement plus aigu, non de drapeaux, mais de guerriers, non

d'ordre mais de révolte, non de systèmes, mais d'hommes. »

Ernst Jünger

On peut gloser à l'infini sur ce qui distingue ou oppose Ernst Jünger et Julius Evola. Lorsque celui-là avance par intuitions, visions, formes brèves inspirées des moralistes français non moins que de Novalis et de Nietzsche, celui-ci s'efforce à un exposé de plus en plus systématique, voire doctrinal. Alors que Jünger abandonne très tôt l'activité politique, même indirecte, la jugeant « inconvenante » à la fois du point de vue du style et de celui de l'éthique, Evola ne cessera point tout au long de son œuvre de revenir sur une définition possible de ce que pourrait être une « droite intégrale » selon son intelligence et son cœur. Lorsque Jünger interroge avec persistance et audace le monde des songes et de la nuit, Evola témoigne d'une préférence invariable pour les hauteurs ouraniennes et le resplendissement solaire du Logos-Roi. Ernst Jünger demeure dans une large mesure un disciple de Novalis et de sa spiritualité romane, alors que Julius Evola se veut un continuateur de l'Empereur Julien, un fidèle aux dieux antérieurs, de lignée platonicienne et visionnaire.

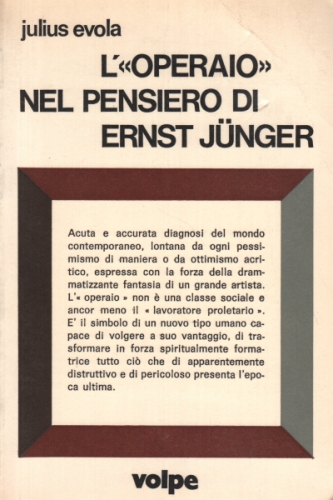

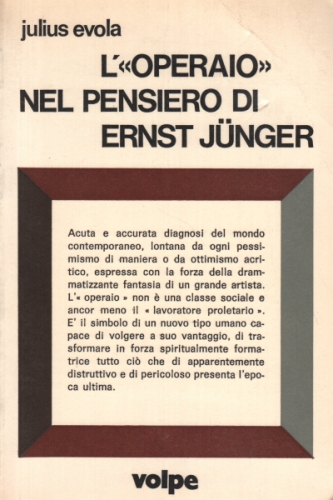

Ces différences favorisent des lectures non point opposées, ni exclusives l'une de l'autre, mais complémentaires. A l'exception du Travailleur, livre qui définit de façon presque didactique l'émergence d'un Type, Jünger demeure fidèle à ce cheminement que l'on peut définir, avec une grande prudence, comme « romantique » et dont la caractéristique dominante n'est certes point l'effusion sentimentale mais la nature déambulatoire, le goût des sentes forestières, ces « chemins qui ne mènent nulle part » qu'affectionnait Heidegger, à la suite d'Heinrich von Ofterdingen et du « voyageur » de Gènes, de Venise et d'Engadine, toujours accompagné d'une « ombre » qui n'est point celle du désespoir, ni du doute, mais sans doute l'ombre de la Mesure qui suit la marche de ces hommes qui vont vers le soleil sans craindre la démesure.

Ces différences favorisent des lectures non point opposées, ni exclusives l'une de l'autre, mais complémentaires. A l'exception du Travailleur, livre qui définit de façon presque didactique l'émergence d'un Type, Jünger demeure fidèle à ce cheminement que l'on peut définir, avec une grande prudence, comme « romantique » et dont la caractéristique dominante n'est certes point l'effusion sentimentale mais la nature déambulatoire, le goût des sentes forestières, ces « chemins qui ne mènent nulle part » qu'affectionnait Heidegger, à la suite d'Heinrich von Ofterdingen et du « voyageur » de Gènes, de Venise et d'Engadine, toujours accompagné d'une « ombre » qui n'est point celle du désespoir, ni du doute, mais sans doute l'ombre de la Mesure qui suit la marche de ces hommes qui vont vers le soleil sans craindre la démesure.

L'interrogation fondamentale, ou pour mieux dire originelle, des oeuvres de Jünger et d'Evola concerne essentiellement le dépassement du nihilisme. Le nihilisme tel que le monde moderne en précise les pouvoirs au moment où Jünger et Evola se lancent héroïquement dans l'existence, avec l'espoir d'échapper à la médiocrité, est à la fois ce qui doit être éprouvé et ce qui doit être vaincu et dépassé. Pour le Jünger du Cœur aventureux comme pour le Julius Evola des premières tentatives dadaïstes, rien n'est pire que de feindre de croire encore en un monde immobile, impartial, sûr. Ce qui menace de disparaître, la tentation est grande pour nos auteurs, adeptes d'un « réalisme héroïque », d'en précipiter la chute. Le nihilisme est, pour Jünger, comme pour Evola, une expérience à laquelle ni l'un ni l'autre ne se dérobent. Cependant, dans les « orages d'acier », ils ne croient point que l'immanence est le seul horizon de l'expérience humaine. L'épreuve, pour ténébreuse et confuse qu'elle paraisse, ne se suffit point à elle-même. Ernst Jünger et Julius Evola pressentent que le tumulte n'est que l'arcane d'une sérénité conquise. De ce cyclone qui emporte leurs vies et la haute culture européenne, ils cherchent le cœur intangible. Il s'agit là, écrit Julius Evola de la recherche « d'une vie portée à une intensité particulière qui débouche, se renverse et se libère en un "plus que vie", grâce à une rupture ontologique de niveau. » Dans l'œuvre de Jünger, comme dans celle d'Evola, l'influence de Nietzsche, on le voit, est décisive. Nietzsche, pour le dire au plus vite, peut être considéré comme l'inventeur du « nihilisme actif », c'est-à-dire d'un nihilisme qui périt dans son triomphe, en toute conscience, ou devrait-on dire selon la terminologie abellienne, dans un « paroxysme de conscience ». Nietzsche se définissait comme « le premier nihiliste complet Europe, qui a cependant déjà dépassé le nihilisme pour l'avoir vécu dans son âme, pour l'avoir derrière soi, sous soi, hors de soi. »

Cette épreuve terrible, nul esprit loyal n'y échappe. Le bourgeois, celui qui croit ou feint de croire aux « valeurs » n'est qu'un nihiliste passif: il est l'esprit de pesanteur qui entraîne le monde vers le règne de la quantité. « Mieux vaut être un criminel qu'un bourgeois », écrivit Jünger, non sans une certaine provocation juvénile, en ignorant peut-être aussi la nature profondément criminelle que peut revêtir, le cas échéant, la pensée calculante propre à la bourgeoisie. Peu importe : la bourgeoisie d'alors paraissait inerte, elle ne s'était pas encore emparée de la puissance du contrôle génétique et cybernétique pour soumettre le monde à sa mesquinerie. Dans la perspective nietzschéenne qui s'ouvre alors devant eux, Jünger et Evola se confrontent à la doctrine du Kirillov de Dostoïevski: « L'homme n'a inventé Dieu qu'afin de pouvoir vivre sans se tuer ». Or, ce nihilisme est encore partiel, susceptible d'être dépassé, car, pour les âmes généreuses, il n'existe des raisons de se tuer que parce qu'il existe des raisons de vivre. Ce qui importe, c'est de réinventer une métaphysique contre le monde utilitaire et de dépasser l'opposition de la vie et de la mort.

Jünger et Evola sont aussi, mais d’une manière différente, à la recherche de ce qu'André Breton nomme dans son Manifeste « Le point suprême ». Julius Evola écrit: « L'homme qui, sûr de soi parce que c'est l'être, et non la vie, qui est le centre essentiel de sa personne peut tout approcher, s'abandonner à tout et s'ouvrir à tout sans se perdre: accepter, de ce fait, n'importe quelle expérience, non plus, maintenant pour s'éprouver et se connaître mais pour développer toutes ses possibilités en vue des transformations qui peuvent se produire en lui, en vue des nouveaux contenus qui peuvent, par cette voie, s'offrir et se révéler. » Quant à Jünger, dans Le Cœur Aventureux, version 1928, il exhorte ainsi son lecteur: « Considère la vie comme un rêve entre mille rêves, et chaque rêve comme une ouverture particulière de la réalité. » Cet ordre établi, cet univers de fausse sécurité, où règne l'individu massifié, Jünger et Evola n'en veulent pas. Le réalisme héroïque dont ils se réclament n'est point froideur mais embrasement de l'être, éveil des puissances recouvertes par les écorces de cendre des habitudes, des exotérismes dominateurs, des dogmes, des sciences, des idéologies. Un mouvement identique les porte de la périphérie vers le centre, vers le secret de la souveraineté. Jünger: « La science n'est féconde que grâce à l'exigence qui en constitue le fondement. En cela réside la haute, l'exceptionnelle valeur des natures de la trempe de Saint-Augustin et de Pascal: l'union très rare d'une âme de feu et d'une intelligence pénétrante, l'accès à ce soleil invisible de Swedenborg qui est aussi lumineux qu'ardent. »

Tel est exactement le dépassement du nihilisme: révéler dans le feu qui détruit la lumière qui éclaire, pour ensuite pouvoir se recueillir dans la « clairière de l'être ». Pour celui qui a véritablement dépassé le nihilisme, il n'y a plus de partis, de classes, de tribus, il n'y a plus que l'être et le néant. A cette étape, le cyclone offre son cœur à « une sorte de contemplation qui superpose la région du rêve à celle de la réalité comme deux lentilles transparentes braquées sur le foyer spirituel. » Dans l'un de ses ultimes entretiens, Jünger interrogé sur la notion de résistance spirituelle précise: « la résistance spirituelle ne suffit pas. Il faut contre-attaquer. »

Il serait trop simple d'opposer comme le font certains l'activiste Evola avec le contemplatif Jünger, comme si Jünger avait trahi sa jeunesse fougueuse pour adopter la pose goethéenne du sage revenu de tout. A celui qui veut à tout prix discerner des périodes dans les œuvres de Jünger et d'Evola, ce sont les circonstances historiques qui donnent raison bien davantage que le sens des œuvres. Les œuvres se déploient; les premiers livres d'Evola et de Jünger contiennent déjà les teintes et les vertus de ceux, nombreux, qui suivront. Tout se tient à l'orée d'une forte résolution, d'une exigence de surpassement, quand bien-même il s'avère que le Haut, n'est une métaphore du Centre et que l'apogée de l'aristocratie rêvée n'est autre que l'égalité d'âme du Tao, « l'agir sans agir ». Evola cite cette phrase de Nietzsche qui dut également frapper Jünger: « L'esprit, c'est la vie qui incise elle-même la vie ». A ces grandes âmes, la vie ne suffit point. C'est en ce sens que Jünger et Evola refusent avec la même rigueur le naturalisme et le règne de la technique, qui ne sont que l'avers et l'envers d'un même renoncement de l'homme à se dépasser lui-même. Le caractère odieux des totalitarismes réside précisément dans ce renoncement.

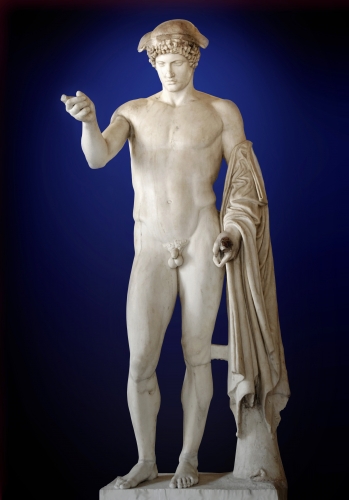

La quête de Jünger et d'Evola fond dans un même métal l'éthique et l'esthétique au feu d'une métaphysique qui refuse de se soumettre au règne de la nature. Toute l'œuvre de Jünger affirme, par sa théorie du sceau et de l'empreinte, que la nature est à l'image de la Surnature, que le visible n'est qu'un miroir de l'Invisible. De même, pour Evola, en cela fort platonicien, c'est à la Forme d'ordonner la matière. Telle est l'essence de la virilité spirituelle. Si Jünger, comme Evola, et comme bien d'autres, fut dédaigné, voire incriminé, sous le terme d'esthète par les puritains et les moralisateurs, c'est aussi par sa tentative de dépasser ce que l'on nomme la « morale autonome », c'est-à-dire laïque et rationnelle, sans pour autant retomber dans un « vitalisme » primaire. C'est qu'il existe, pour Jünger, comme pour Evola qui se réfère explicitement à une vision du monde hiérarchique, un au-delà et un en deçà de la morale, comme il existe un au-delà et un en deçà de l'individu.

Lorsque la morale échappe au jugement du plus grand nombre, à l'utilitarisme de la classe dominante, elle paraît s'abolir dans une esthétique. Or, le Beau, pour Jünger, ce que la terminologie évolienne, et platonicienne, nomme la Forme (idéa) contient et réalise les plus hautes possibilités du Bien moral. Le Beau contient dans son exactitude, la justesse du Bien. L'esthétique ne contredit point la morale, elle en précise le contour, mieux, elle fait de la résistance au Mal qui est le propre de toute morale, une contre-attaque. Le Beau est un Bien en action, un Bien qui arrache la vie aux griffes du Léviathan et au règne des Titans. Jünger sur ce point ne varie pas . Dans son entretien séculaire, il dit à Franco Volpi: « Je dirai qu'éthique et esthétique se rencontrent et se touchent au moins sur un point: ce qui est vraiment beau est obligatoirement éthique, et ce qui est réellement éthique est obligatoirement beau. »

A ceux qui veulent opposer Jünger et Evola, il demeure d'autres arguments. Ainsi, il paraît fondé de voir en l'œuvre de Jünger, après Le Travailleur, une méditation constante sur la rébellion et la possibilité offerte à l'homme de se rendre hors d'atteinte de ce « plus froid des monstres froids », ainsi que Nietzsche nomme l'Etat. Au contraire, l'œuvre d'Evola poursuit avec non moins de constance l'approfondissement d'une philosophie politique destinée à fonder les normes et les possibilités de réalisation de « l'Etat vrai ». Cependant, ce serait là encore faire preuve d'un schématisme fallacieux que de se contenter de classer simplement Jünger parmi les « libertaires » fussent-ils « de droite » et Evola auprès des « étatistes ».

Si quelque vertu agissante, et au sens vrai, poétique, subsiste dans les oeuvres de Jünger et d'Evola les plus étroitement liées à des circonstances disparues ou en voie de disparition, c'est précisément car elles suivent des voies qui ne cessent de contredire les classifications, de poser d'autres questions au terme de réponses en apparence souveraines et sans appel. Un véritable auteur se reconnaît à la force avec laquelle il noue ensemble ses contradictions. C'est alors seulement que son œuvre échappe à la subjectivité et devient, dans le monde, une œuvre à la ressemblance du monde. L'œuvre poursuit son destin envers et contre les Abstracteurs qui, en nous posant de fausses alternatives visent en réalité à nous priver de la moitié de nous-mêmes. Les véritables choix ne sont pas entre la droite et la gauche, entre l'individu et l'Etat, entre la raison et l'irrationnel, c'est à dire d'ordre horizontal ou « latéral ». Les choix auxquels nous convient Jünger et Evola, qui sont bien des écrivains engagés, sont d'ordre vertical. Leurs œuvres nous font comprendre que, dans une large mesure, les choix horizontaux sont des leurres destinés à nous faire oublier les choix verticaux.

La question si controversée de l'individualisme peut servir ici d'exemple. Pour Jünger comme pour Evola, le triomphe du nihilisme, contre lequel il importe d'armer l'intelligence de la nouvelle chevalerie intellectuelle, est sans conteste l'individualisme libéral. Sous cette appellation se retrouvent à la fois l'utilitarisme bourgeois, honni par tous les grandes figures de la littérature du dix-neuvième siècle (Stendhal, Flaubert, Balzac, Villiers de L'Isle-Adam, Léon Bloy, Barbey d'Aurevilly, Théophile Gautier, Baudelaire, d'Annunzio, Carlyle etc...) mais aussi le pressentiment d'un totalitarisme dont les despotismes de naguère ne furent que de pâles préfigurations. L'individualisme du monde moderne est un « individualisme de masse », pour reprendre la formule de Jünger, un individualisme qui réduit l'individu à l'état d'unité interchangeable avec une rigueur à laquelle les totalitarismes disciplinaires, spartiates ou soviétiques, ne parvinrent jamais.

Loin d'opposer l'individualisme et le collectivisme, loin de croire que le collectivisme puisse redimer de quelque façon le néant de l'individualisme libéral, selon une analyse purement horizontale qui demeure hélas le seul horizon de nos sociologues, Jünger tente d'introduire dans la réflexion politique un en-decà et un au-delà de l'individu. Si l'individu « libéral » est voué, par la pesanteur même de son matérialisme à s'anéantir dans un en-deçà de l'individu, c'est-à-dire dans un collectivisme marchand et cybernétique aux dimensions de la planète, l'individu qui échappe au matérialisme, c'est-à-dire l'individu qui garde en lui la nostalgie d'une Forme possède, lui, la chance magnifique de se hausser à cet au-delà de l'individu, que Julius Evola nomme la Personne. Au delà de l'individu est la Forme ou, en terminologie jüngérienne, la Figure, qui permet à l'individu de devenir une Personne.

Qu'est-ce que la Figure ? La Figure, nous dit Jünger, est le tout qui englobe plus que la somme des parties. C'est en ce sens que la Figure échappe au déterminisme, qu'il soit économique ou biologique. L'individu du matérialisme libéral demeure soumis au déterminisme, et de ce fait, il appartient encore au monde animal, au « biologique ». Tout ce qui s'explique en terme de logique linéaire, déterministe, appartient encore à la nature, à l'en-deçà des possibilités surhumaines qui sont le propre de l'humanitas. « L'ordre hiérarchique dans le domaine de la Figure ne résulte pas de la loi de cause et d'effet, écrit Jünger mais d'une loi tout autre, celle du sceau et de l'empreinte. » Par ce renversement herméneutique décisif, la pensée de Jünger s'avère beaucoup plus proche de celle d'Evola que l'on ne pourrait le croire de prime abord. Dans le monde hiérarchique, que décrit Jünger où le monde obéit à la loi du sceau et de l'empreinte, les logiques évolutionnistes ou progressistes, qui s'obstinent (comme le nazisme ou le libéralisme darwinien) dans une vision zoologique du genre humain, perdent toute signification. Telle est exactement la Tradition, à laquelle se réfère toute l'œuvre de Julius Evola: « Pour comprendre aussi bien l'esprit traditionnel que la civilisation moderne, en tant que négation de cet esprit, écrit Julius Evola, il faut partir de cette base fondamentale qu'est l'enseignement relatif aux deux natures. Il y a un ordre physique et il y a un ordre métaphysique. Il y a une nature mortelle et il y a la nature des immortels. Il y a la région supérieure de l'être et il y a la région inférieure du devenir. D'une manière plus générale, il y a un visible et un tangible, et avant et au delà de celui-ci, il y a un invisible et un intangible, qui constituent le supra-monde, le principe et la véritable vie. Partout, dans le monde de la Tradition, en Orient et en Occident, sous une forme ou sous une autre, cette connaissance a toujours été présente comme un axe inébranlable autour duquel tout le reste était hiérarchiquement organisé. »

Qu'est-ce que la Figure ? La Figure, nous dit Jünger, est le tout qui englobe plus que la somme des parties. C'est en ce sens que la Figure échappe au déterminisme, qu'il soit économique ou biologique. L'individu du matérialisme libéral demeure soumis au déterminisme, et de ce fait, il appartient encore au monde animal, au « biologique ». Tout ce qui s'explique en terme de logique linéaire, déterministe, appartient encore à la nature, à l'en-deçà des possibilités surhumaines qui sont le propre de l'humanitas. « L'ordre hiérarchique dans le domaine de la Figure ne résulte pas de la loi de cause et d'effet, écrit Jünger mais d'une loi tout autre, celle du sceau et de l'empreinte. » Par ce renversement herméneutique décisif, la pensée de Jünger s'avère beaucoup plus proche de celle d'Evola que l'on ne pourrait le croire de prime abord. Dans le monde hiérarchique, que décrit Jünger où le monde obéit à la loi du sceau et de l'empreinte, les logiques évolutionnistes ou progressistes, qui s'obstinent (comme le nazisme ou le libéralisme darwinien) dans une vision zoologique du genre humain, perdent toute signification. Telle est exactement la Tradition, à laquelle se réfère toute l'œuvre de Julius Evola: « Pour comprendre aussi bien l'esprit traditionnel que la civilisation moderne, en tant que négation de cet esprit, écrit Julius Evola, il faut partir de cette base fondamentale qu'est l'enseignement relatif aux deux natures. Il y a un ordre physique et il y a un ordre métaphysique. Il y a une nature mortelle et il y a la nature des immortels. Il y a la région supérieure de l'être et il y a la région inférieure du devenir. D'une manière plus générale, il y a un visible et un tangible, et avant et au delà de celui-ci, il y a un invisible et un intangible, qui constituent le supra-monde, le principe et la véritable vie. Partout, dans le monde de la Tradition, en Orient et en Occident, sous une forme ou sous une autre, cette connaissance a toujours été présente comme un axe inébranlable autour duquel tout le reste était hiérarchiquement organisé. »

Affirmer, comme le fait Jünger, la caducité de la logique de cause et d'effet, c'est, dans l'ordre d'une philosophie politique rénovée, suspendre la logique déterministe et tout ce qui en elle plaide en faveur de l'asservissement de l'individu. « On donnera le titre de Figure, écrit Jünger, au genre de grandeur qui s'offrent à un regard capable de concevoir que le monde peut être appréhendé dans son ensemble selon une loi plus décisive que celle de la cause et de l'effet. » Du rapport entre le sceau invisible et l'empreinte visible dépend tout ce qui dans la réalité relève de la qualité. Ce qui n'a point d'empreinte, c'est la quantité pure, la matière livrée à elle-même. Le sceau est ce qui confère à l'individu, à la fois la dignité et la qualité. En ce sens, Jünger, comme Evola, pense qu'une certaine forme d'égalitarisme revient à nier la dignité de l'individu, à lui ôter par avance toute chance d'atteindre à la dignité et à la qualité d'une Forme. « On ne contestera pas, écrit Julius Evola, que les êtres humains, sous certains aspects, soient à peu près égaux; mais ces aspects, dans toute conception normale et traditionnelle, ne représentent pas le "plus" mais le "moins", correspondent au niveau le plus pauvre de la réalité, à ce qu'il y a de moins intéressant en nous. Il s'agit d'un ordre qui n'est pas encore celui de la forme, de la personnalité au sens propre. Accorder de la valeur à ces aspects, les mettre en relief comme si on devait leur donner la priorité, équivaudrait à tenir pour essentiel que ces statues soient en bronze et non que chacune soit l'expression d'une idée distincte dont le bronze ( ici la qualité générique humaine) n'est que le support matériel. »

Ce platonisme que l'on pourrait dire héroïque apparaît comme un défi à la doxa moderne. Lorsque le moderne ne vante la « liberté » que pour en anéantir toute possibilité effective dans la soumission de l'homme à l'évolution, au déterminisme, à l'histoire, au progrès, l'homme de la Tradition, selon Evola, demeure fidèle à une vision supra-historique. De même, contrairement à ce que feignent de croire des exégètes peu informés, le « réalisme héroïque » des premières œuvres de Jünger loin de se complaire dans un immanentisme de la force et de la volonté, est un hommage direct à l'ontologie de la Forme, à l'idée de la préexistence. « La Figure, écrit Jünger, dans Le Travailleur, est, et aucune évolution ne l'accroît ni ne la diminue. De même que la Figure de l'homme précédait sa naissance et survivra à sa mort, une Figure historique est, au plus profond d'elle-même, indépendante du temps et des circonstances dont elle semble naître. Les moyens dont elle dispose sont supérieurs, sa fécondité est immédiate. L'histoire n'engendre pas de figures, elle se transforme au contraire avec la Figure. »

Sans doute le jugement d'Evola, qui tout en reconnaissant la pertinence métapolitique de la Figure du Travailleur n'en critique pas moins l'ouvrage de Jünger comme dépourvu d'une véritable perspective métaphysique, peut ainsi être nuancée. Jünger pose bien, selon une hiérarchie métaphysique, la distinction entre l'individu susceptible d'être massifié (qu'il nomme dans Le Travailleur « individuum ») et l'individu susceptible de recevoir l'empreinte d'une Forme supérieure (et qu'il nomme « Einzelne »). Cette différenciation terminologique verticale est incontestablement l'ébauche d'une métaphysique, quand bien même, mais tel n'est pas non plus le propos du Travailleur, il n'y est pas question de cet au-delà de la personne auquel invitent les métaphysiques traditionnelles, à travers les œuvres de Maître Eckhart ou du Védantâ. De même qu'il existe un au-delà et un en-deçà de l'individu, il existe dans un ordre plus proche de l'intangible un au-delà et un en-deçà de la personne. Le « dépassement » de l'individu, selon qu'il s'agit d'un dépassement par le bas ou par le haut peut aboutir aussi bien, selon son orientation, à la masse indistincte qu'à la formation de la Personne. Le dépassement de la personne, c'est-à-dire l'impersonnalité, peut, selon Evola, se concevoir de deux façons opposées: « l'une se situe au-dessous, l'autre au niveau de la personne; l'une aboutit à l'individu, sous l'aspect informe d'une unité numérique et indifférente qui, en se multipliant, produit la masse anonyme; l'autre est l'apogée typique d'un être souverain, c'est la personne absolue. »

Loin d'abonder dans le sens d'une critique sommaire et purement matérialiste de l'individualisme auquel n'importe quelle forme d'étatisme ou de communautarisme devrait être préféré aveuglément, le gibelin Julius Evola, comme l'Anarque jüngérien se rejoignent dans la méditation d'un ordre qui favoriserait « l'apogée typique d'un être souverain ». Il est exact de dire, précise Evola, « que l'état et le droit représentent quelque chose de secondaire par rapport à la qualité des hommes qui en sont les créateurs, et que cet Etat, ce droit ne sont bons que dans le mesure où ils restent des formes fidèles aux exigences originelles et des instruments capables de consolider et de confirmer les forces mêmes qui leur ont donné naissance. » La critique évolienne de l'individualisme, loin d'abonder dans le sens d'une mystique de l'élan commun en détruit les fondements mêmes. Rien, et Julius Evola y revient à maintes reprises, ne lui est aussi odieux que l'esprit grégaire: « Assez du besoin qui lie ensemble les hommes mendiant au lien commun et à la dépendance réciproque la consistance qui fait défaut à chacun d'eux ! »

Pour qu'il y eût un Etat digne de ce nom, pour que l'individu puisse être dépassé, mais par le haut, c'est-à-dire par une fidélité métaphysique, il faut commencer par s'être délivré de ce besoin funeste de dépendance. Ajoutées les unes aux autres les dépendances engendrent l'odieux Léviathan, que Simone Weil nommait « le gros animal », ce despotisme du Médiocre dont le vingtième siècle n'a offert que trop d'exemples. Point d'Etat légitime, et point d'individu se dépassant lui-même dans une généreuse impersonnalité active, sans une véritable Sapience, au sens médiéval, c'est-à-dire une métaphysique de l'éternelle souveraineté. « La part inaliénable de l'individu (Einzelne) écrit Jünger, c'est qu'il relève de l'éternité, et dans ses moments suprêmes et sans ambiguïté, il en est pleinement conscient. Sa tâche est d'exprimer cela dans le temps. En ce sens, sa vie devient une parabole de la Figure. » Evola reconnaît ainsi « en certains cas la priorité de la personne même en face de l'Etat », lorsque la personne porte en elle, mieux que l'ensemble, le sens et les possibilités créatrices de la Sapience.

Quelles que soient nos orientations, nos présupposés philosophiques ou littéraires, aussitôt sommes-nous requis par quelque appel du Grand Large qui nous incline à laisser derrière nous, comme des écorces mortes, le « trop humain » et les réalités confinées de la subjectivité, c'est à la Sapience que se dédient nos pensées. Du précepte delphique « Connais-toi toi-même et tu connaîtras le monde et les dieux », les œuvres de Jünger et d'Evola éveillent les pouvoirs en redonnant au mot de « réalité » un sens que lui avaient ôté ces dernières générations de sinistres et soi-disant « réalistes »: « ll est tellement évident que le caractère de "réalité" a été abusivement monopolisé par ce qui, même dans la vie actuelle, n'est qu'une partie de la réalité totale, que cela ne vaut pas la peine d'y insister davantage» écrit Julius Evola. La connaissance de soi-même ne vaut qu'en tant que connaissance réelle du monde. Se connaître soi-même, c'est connaître le monde et les dieux car dans cette forme supérieure de réalisme que préconisent Jünger et Evola: « le réel est perçu dans un état où il n'y a pas de sujet de l'expérience ni d'objet expérimenté, un état caractérisé par une sorte de présence absolue où l'immanent se fait transcendant et le transcendant immanent. » Et sans doute est-ce bien en préfiguration de cette expérience-limite que Jünger écrit: « Et si nous voulons percevoir le tremblement du cœur jusque dans ses plus subtiles fibrilles, nous exigeons en même temps qu'il soit trois fois cuirassé. »

Foi et chevalerie sont les conditions préalables et nécessaires de la Sapience, et c'est précisément en quoi la Sapience se distingue de ce savoir banal et parfois funeste dont les outrecuidants accablent les simples. La Sapience advient, elle ne s'accumule, ni ne se décrète. Elle couronne naturellement des types humains dont les actes et les pensées sont orientés vers le Vrai, le Beau et le Bien, c'est-à-dire qu'elle vibre et claque au vent de l'Esprit. La Sapience n'est pas cette petite satisfaction du clerc qui croit se suffire à lui-même. La Sapience ne vaut qu'en tant que défi au monde, et il vaut mieux périr de ce défi que de tirer son existence à la ligne comme un mauvais feuilletoniste. Les stances du Dhammapada, attribué au Bouddha lui-même ne disent pas autre chose: "« Plutôt vivre un jour en considérant l'apparition et la disparition que cent ans sans les voir."

Le silence et la contemplation de la Sapience sont vertige et éblouissement et non point cette ignoble recherche de confort et de méthodes thérapeutiques dont les adeptes du « new-age » parachèvent leur arrogance technocratique. « L'Occident ne connaît plus la Sapience, écrit Evola: il ne connaît plus le silence majestueux des dominateurs d'eux-mêmes, le calme illuminé des Voyants, la superbe réalité de ceux chez qui l'idée s'est faite sang, vie, puissance... A la Sapience ont succédé la contamination sentimentale, religieuse, humanitaire, et la race de ceux qui s'agitent en caquetant et courent, ivres, exaltant le devenir et la pratique, parce que le silence et la contemplation leur font peur. »

Le moderne, qui réclame sans cesse de nouveaux droits, mais se dérobe à tous les devoirs, hait la Sapience car, analogique et ascendante, elle élargit le champ de sa responsabilité. L'irresponsable moderne qui déteste la liberté avec plus de hargne que son pire ennemi ( si tant est qu'il eût encore assez de cœur pour avoir un ennemi) ne peut voir en la théorie des correspondances qu'une menace à peine voilée adressée à sa paresse et à son abandon au courant d'un « progrès » qui entraîne, selon la formule de Léon Bloy, « comme un chien mort au fil de l'eau ». Rien n'est plus facile que ce nihilisme qui permet de se plaindre de tout, de revendiquer contre tout sans jamais se rebeller contre rien. L'insignifiance est l'horizon que se donne le moderne, où il enferme son cœur et son âme jusqu'à l'a asphyxie et l'étiolement. « L'homme qui attribue de la valeur à ses expériences, écrit Jünger, quelles qu'elles soient, et qui, en tant que parties de lui-même ne veut pas les abandonner au royaume de l'obscurité, élargit le cercle de sa responsabilité. » C'est en ce sens précis que le moderne, tout en nous accablant d'un titanisme affreux, ne vénère dans l'ordre de l'esprit que la petitesse, et que toute recherche de grandeur spirituelle lui apparaît vaine ou coupable.

Nous retrouvons dans les grands paysages intérieurs que décrit Jünger dans Héliopolis, ce goût du vaste, de l'ampleur musicale et chromatique où l'invisible et le visible correspondent. Pour ce type d'homme précise Evola: « il n'y aura pas de paysages plus beaux, mais des paysages plus lointains, plus immenses, plus calmes, plus froids, plus durs, plus primordiaux que d'autres: Le langage des choses du monde ne nous parvient pas parmi les arbres, les ruisseaux, les beaux jardins, devant les couchers de soleil chromos ou de romantiques clairs de lune mais plutôt dans les déserts, les rocs, les steppes, les glaces, les noirs fjords nordiques, sous les soleils implacables des tropiques- précisément dans tout ce qui est primordial et inaccessible. » La Sapience alors est l'éclat fulgurant qui transfigure le cœur qui s'est ouvert à la Foi et à la Chevalerie quand bien même, écrit Evola: « le cercle se resserre de plus en plus chaque jour autour des rares êtres qui sont encore capables du grand dégoût et de la grande révolte. » Sapience de poètes et de guerriers et non de docteurs, Sapience qui lève devant elle les hautes images de feu et de gloire qui annoncent les nouveaux règnes !

Nous retrouvons dans les grands paysages intérieurs que décrit Jünger dans Héliopolis, ce goût du vaste, de l'ampleur musicale et chromatique où l'invisible et le visible correspondent. Pour ce type d'homme précise Evola: « il n'y aura pas de paysages plus beaux, mais des paysages plus lointains, plus immenses, plus calmes, plus froids, plus durs, plus primordiaux que d'autres: Le langage des choses du monde ne nous parvient pas parmi les arbres, les ruisseaux, les beaux jardins, devant les couchers de soleil chromos ou de romantiques clairs de lune mais plutôt dans les déserts, les rocs, les steppes, les glaces, les noirs fjords nordiques, sous les soleils implacables des tropiques- précisément dans tout ce qui est primordial et inaccessible. » La Sapience alors est l'éclat fulgurant qui transfigure le cœur qui s'est ouvert à la Foi et à la Chevalerie quand bien même, écrit Evola: « le cercle se resserre de plus en plus chaque jour autour des rares êtres qui sont encore capables du grand dégoût et de la grande révolte. » Sapience de poètes et de guerriers et non de docteurs, Sapience qui lève devant elle les hautes images de feu et de gloire qui annoncent les nouveaux règnes !

« Nos images, écrit Jünger, résident dans ces lointains plus écartés et plus lumineux où les sceaux étrangers ont perdu leur validité, et le chemin qui mène à nos fraternités les plus secrètes passe par d'autres souffrances. Et notre croix a une solide poignée, et une âme forgée dans un acier à double tranchant. » La Sapience surgit sur les chemins non de la liberté octroyée, mais de la liberté conquise. « C'est plutôt le héros lui-même, écrit Jünger, qui par l'acte de dominer et de se dominer, aide tous les autres en permettant à l'idée de liberté de triompher... »

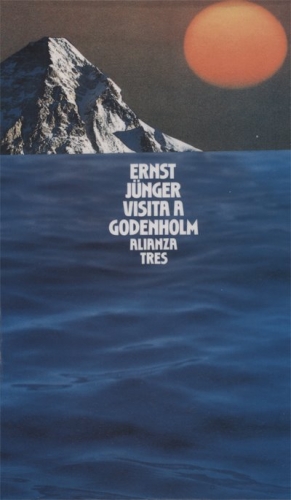

Dans l'œil du cyclone, dans la sérénité retrouvée, telle qu'elle déploie son imagerie solaire à la fin de La Visite à Godenholm, une fois que sont vaincus, dans le corps et dans l'âme, les cris des oiseaux de mauvais augure du nihilisme, L'Anarque jüngérien, à l'instar de l'homme de la Tradition évolien, peut juger l'humanisme libéral et le monde moderne, non pour ce qu'ils se donnent, dans une propagande titanesque, mais pour ce qu'ils sont: des idéologies de la haine de toute forme de liberté accomplie. Que faut-il comprendre par liberté accomplie ? Disons une liberté qui non seulement se réalise dans les actes et dans les œuvres mais qui trouve sa raison d'être dans l'ordre du monde. « Libre ? Pour quoi faire ? » s'interrogeait Nietzsche. A l'évidence, une liberté qui ne culmine point en un acte poétique, une liberté sans « faire » n'est qu'une façon complaisante d'accepter l'esclavage. L'Anarque et l'homme de la Tradition récusent l'individualisme libéral car celui-ci leur paraît être, en réalité, la négation à la fois de l'Individu et de la liberté. Lorsque Julius Evola rejoint, non sans y apporter ses nuances gibelines et impériales, la doctrine traditionnelle formulée magistralement par René Guénon, il ne renonce pas à l'exigence qui préside à sa Théorie de l'Individu absolu, il en trouve au contraire, à travers les ascèses bouddhistes, alchimiques ou tantriques, les modes de réalisation et cette sorte de pragmatique métaphysique qui tant fait défaut au discours philosophique occidental depuis Kant. « C'est que la liberté n'admet pas de compromis: ou bien on l'affirme, ou bien on ne l'affirme pas. Mais si on l'affirme, il faut l'affirmer sans peur, jusqu'au bout, - il faut l'affirmer, par conséquent, comme liberté inconditionnée. » Seul importe au regard métaphysique ce qui est sans condition. Mais un malentendu doit être aussitôt dissipé. Ce qui est inconditionné n'est pas à proprement parler détaché ou distinct du monde. Le « sans condition » est au cœur. Mais lorsque selon les terminologies platoniciennes ou théologiques on le dit « au ciel » ou « du ciel », il faut bien comprendre que ce ciel est au coeur.

Dans l'œil du cyclone, dans la sérénité retrouvée, telle qu'elle déploie son imagerie solaire à la fin de La Visite à Godenholm, une fois que sont vaincus, dans le corps et dans l'âme, les cris des oiseaux de mauvais augure du nihilisme, L'Anarque jüngérien, à l'instar de l'homme de la Tradition évolien, peut juger l'humanisme libéral et le monde moderne, non pour ce qu'ils se donnent, dans une propagande titanesque, mais pour ce qu'ils sont: des idéologies de la haine de toute forme de liberté accomplie. Que faut-il comprendre par liberté accomplie ? Disons une liberté qui non seulement se réalise dans les actes et dans les œuvres mais qui trouve sa raison d'être dans l'ordre du monde. « Libre ? Pour quoi faire ? » s'interrogeait Nietzsche. A l'évidence, une liberté qui ne culmine point en un acte poétique, une liberté sans « faire » n'est qu'une façon complaisante d'accepter l'esclavage. L'Anarque et l'homme de la Tradition récusent l'individualisme libéral car celui-ci leur paraît être, en réalité, la négation à la fois de l'Individu et de la liberté. Lorsque Julius Evola rejoint, non sans y apporter ses nuances gibelines et impériales, la doctrine traditionnelle formulée magistralement par René Guénon, il ne renonce pas à l'exigence qui préside à sa Théorie de l'Individu absolu, il en trouve au contraire, à travers les ascèses bouddhistes, alchimiques ou tantriques, les modes de réalisation et cette sorte de pragmatique métaphysique qui tant fait défaut au discours philosophique occidental depuis Kant. « C'est que la liberté n'admet pas de compromis: ou bien on l'affirme, ou bien on ne l'affirme pas. Mais si on l'affirme, il faut l'affirmer sans peur, jusqu'au bout, - il faut l'affirmer, par conséquent, comme liberté inconditionnée. » Seul importe au regard métaphysique ce qui est sans condition. Mais un malentendu doit être aussitôt dissipé. Ce qui est inconditionné n'est pas à proprement parler détaché ou distinct du monde. Le « sans condition » est au cœur. Mais lorsque selon les terminologies platoniciennes ou théologiques on le dit « au ciel » ou « du ciel », il faut bien comprendre que ce ciel est au coeur.

L'inconditionné n'est pas hors de la périphérie, mais au centre. C'est au plus près de soi et du monde qu'il se révèle. D'où l'importance de ce que Jünger nomme les « approches ». Plus nous sommes près du monde dans son frémissement sensible, moins nous sommes soumis aux généralités et aux abstractions idéologiques, et plus nous sommes près des Symboles. Car le symbole se tient entre deux mondes. Ce monde de la nature qui flambe d'une splendeur surnaturelle que Jünger aperçoit dans la fleur ou dans l'insecte, n'est pas le monde d'un panthéiste, mais le monde exactement révélé par l'auguste science des symboles. « La science des symboles, rappelle Luc Benoist, est fondée sur la correspondance qui existe entre les divers ordres de réalité, naturelle et surnaturelle, la naturelle n'étant alors considérée que comme l'extériorisation du surnaturel. » La nature telle que la perçoivent Jünger et Evola (celui-ci suivant une voie beaucoup plus « sèche ») est bien la baudelairienne et swedenborgienne « forêt de symboles ». Elle nous écarte de l'abstraction en même temps qu'elle nous rapproche de la métaphysique. « La perspective métaphysique, qui vise à dépasser l'abstraction conceptuelle, trouve dans le caractère intuitif et synthétique du symbole en général et du Mythe en particulier un instrument d'expression particulièrement apte à véhiculer l'intuition intellectuelle. »écrit George Vallin. Les grandes imageries des Falaises de Marbre, d'Héliopolis, les récits de rêves, des journaux et du Cœur aventureux prennent tout leur sens si on les confronte à l'aiguisement de l'intuition intellectuelle. Jünger entre en contemplation pour atteindre cette liberté absolue qui est au cœur des mondes, ce moyeu immobile de la roue, qui ne cessera jamais de tourner vertigineusement. Dans ce que George Vallin nomme l'intuition intellectuelle, l'extrême vitesse et l'extrême immobilité se confondent. Le secret de la Sapience, selon Evola: « cette virtu qui ne parle pas, qui naît dans le silence hermétique et pythagoricien, qui fleurit sur la maîtrise des sens et de l'âme » est au cœur des mondes comme le signe de la « toute-possibilité » . Tout ceci, bien sûr, ne s'adressant qu'au lecteur aimé de Jünger: « ce lecteur dont je suppose toujours qu'il est de la trempe de Don Quichotte et que, pour ainsi dire, il tranche les airs en lisant à grands coups d'épée. »

Luc-Olivier d'Algange.

Le maître ajoute :

Le maître ajoute :

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

L'IRGET (Institut René Guénon d'études traditionnelles), fondé en 1984 dans la ville de São Paulo par le journaliste Luiz Pontual, se consacre à l'étude et à l'enseignement de l'œuvre de René Guénon, comme l'indique la page d'accueil de cet institut. Il est intéressant de noter que Luiz Pontual est également un admirateur de l'œuvre d’Evola, reconnaissant son opposition tout aussi radicale au monde moderne. Cependant, sur le site de l'IRGET, Pontual déclare : "D'autre part, les partisans d'Evola nous reprochent de ne pas le mettre à niveau ou de le placer au-dessus de Guénon. À ces derniers, nous faisons référence à Evola lui-même, qui a écrit dans ses livres, plus d'une fois, la fierté d'être un Kshatrya (porteur du pouvoir temporel) et reconnaissait en Guénon le figure d’un Brahmane (détenteur de l’autorité spirituelle). Cela nous dispense de toute autre explication". Le journaliste Luiz Pontual montre qu'il ne connaît pas l'œuvre d'Evola en profondeur, car le penseur italien affirme que, dans les temps primordiaux, à l'âge d'or, il n'y avait pas de séparation entre l'autorité spirituelle et le pouvoir temporel. La figure de la royauté sacrée, du roi-prêtre, du pontifex, du divin empereur dans les civilisations traditionnelles, atteste la présence d'une autorité supérieure à la caste des prêtres et à celle des guerriers.

L'IRGET (Institut René Guénon d'études traditionnelles), fondé en 1984 dans la ville de São Paulo par le journaliste Luiz Pontual, se consacre à l'étude et à l'enseignement de l'œuvre de René Guénon, comme l'indique la page d'accueil de cet institut. Il est intéressant de noter que Luiz Pontual est également un admirateur de l'œuvre d’Evola, reconnaissant son opposition tout aussi radicale au monde moderne. Cependant, sur le site de l'IRGET, Pontual déclare : "D'autre part, les partisans d'Evola nous reprochent de ne pas le mettre à niveau ou de le placer au-dessus de Guénon. À ces derniers, nous faisons référence à Evola lui-même, qui a écrit dans ses livres, plus d'une fois, la fierté d'être un Kshatrya (porteur du pouvoir temporel) et reconnaissait en Guénon le figure d’un Brahmane (détenteur de l’autorité spirituelle). Cela nous dispense de toute autre explication". Le journaliste Luiz Pontual montre qu'il ne connaît pas l'œuvre d'Evola en profondeur, car le penseur italien affirme que, dans les temps primordiaux, à l'âge d'or, il n'y avait pas de séparation entre l'autorité spirituelle et le pouvoir temporel. La figure de la royauté sacrée, du roi-prêtre, du pontifex, du divin empereur dans les civilisations traditionnelles, atteste la présence d'une autorité supérieure à la caste des prêtres et à celle des guerriers.

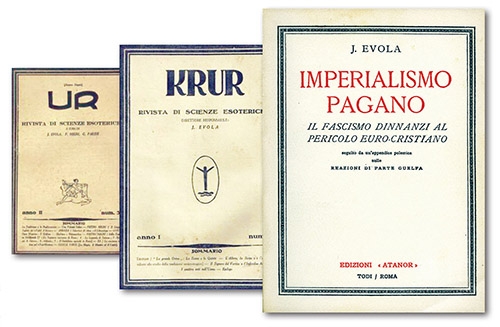

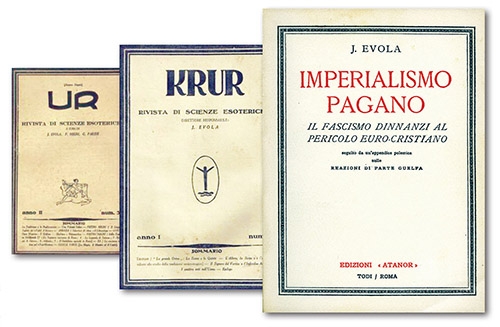

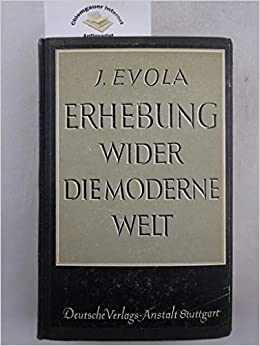

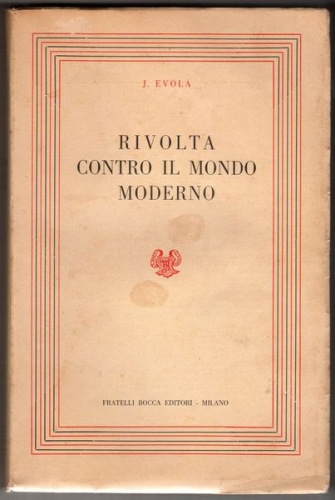

Le 14 mai 1995, le journal Folha de São Paulo, l'un des plus grands journaux du pays, a publié un article de l'écrivain italien Umberto Eco. L'article était intitulé "La nébuleuse fasciste". Le célèbre écrivain italien a tenté d'élaborer un ensemble de traits, de caractéristiques, de ce qu'il a appelé "protofascisme ou fascisme éternel". Parmi les traits énumérés par Eco figure le culte de la tradition, le traditionalisme. À ce propos, il déclare : "Il suffit de jeter un coup d'œil aux parrains de n'importe quel mouvement fasciste pour trouver les grands penseurs traditionalistes. La gnose nazie se nourrissait d'éléments traditionalistes, syncrétiques et occultes. La source théorique la plus importante de la nouvelle droite italienne, Julius Evola, a fusionné le Saint Graal et les Protocoles des Sages de Sion, l'alchimie et le Saint Empire romain-germanique". L'opposition d'Eco à la pensée d'Evola est évidente. L'écrivain italien n'a pas connaissance des critiques de Julius Evola sur le fascisme [2] dans des ouvrages tels que Le fascisme vu de droite et Notes sur le Troisième Reich. Dans ces deux livres, Julius Evola démontre les aspects anti-traditionnels du fascisme italien et du national-socialisme allemand, tels que le culte du chef, le populisme, le nationalisme, le racisme biologique, etc. Quant à la Nouvelle Droite italienne, elle ne se nourrit que de quelques aspects de l'œuvre d'Evola. En tout cas, l'article d'Eco, largement lu par l'intelligentsia brésilienne, ne sert qu'à dénigrer l'image d'Evola et à déformer sa pensée.

Le 14 mai 1995, le journal Folha de São Paulo, l'un des plus grands journaux du pays, a publié un article de l'écrivain italien Umberto Eco. L'article était intitulé "La nébuleuse fasciste". Le célèbre écrivain italien a tenté d'élaborer un ensemble de traits, de caractéristiques, de ce qu'il a appelé "protofascisme ou fascisme éternel". Parmi les traits énumérés par Eco figure le culte de la tradition, le traditionalisme. À ce propos, il déclare : "Il suffit de jeter un coup d'œil aux parrains de n'importe quel mouvement fasciste pour trouver les grands penseurs traditionalistes. La gnose nazie se nourrissait d'éléments traditionalistes, syncrétiques et occultes. La source théorique la plus importante de la nouvelle droite italienne, Julius Evola, a fusionné le Saint Graal et les Protocoles des Sages de Sion, l'alchimie et le Saint Empire romain-germanique". L'opposition d'Eco à la pensée d'Evola est évidente. L'écrivain italien n'a pas connaissance des critiques de Julius Evola sur le fascisme [2] dans des ouvrages tels que Le fascisme vu de droite et Notes sur le Troisième Reich. Dans ces deux livres, Julius Evola démontre les aspects anti-traditionnels du fascisme italien et du national-socialisme allemand, tels que le culte du chef, le populisme, le nationalisme, le racisme biologique, etc. Quant à la Nouvelle Droite italienne, elle ne se nourrit que de quelques aspects de l'œuvre d'Evola. En tout cas, l'article d'Eco, largement lu par l'intelligentsia brésilienne, ne sert qu'à dénigrer l'image d'Evola et à déformer sa pensée.

R : Le livre vise à montrer la caractérisation archétypale de ce que serait un Homme de Tradition, y compris - donc - les objectifs qu'il devrait s'efforcer d'atteindre, afin de servir de modèle à tous ceux de nos semblables qui aspirent à s'élever au-dessus de la médiocrité de l'homme moderne (et, plus encore, post-moderne), médiocrité qui est hégémonique en nos temps de dissolution. En gardant toujours à l'esprit quels sont les traits essentiels qui définissent l'Homme de Tradition, il sera possible d'aspirer, petit à petit, à se forger intérieurement ; avoir ce modèle comme miroir dans lequel se regarder (et qui sait s'il ne sera pas possible d'aspirer à ne pas écarter la possibilité d'opérer un renouvellement ontologique intérieur). La difficulté ou l'impossibilité de trouver, de nos jours, quelque maillon des chaînes initiatiques qui nous relient à la Sagesse de la Tradition Primordiale nous amène à donner une valeur particulière à ce qu'Evola appelle la "voie autonome de réalisation". Le contenu de ce livre peut peut-être aider dans une certaine mesure à faire en sorte que ce chemin ne soit pas une chimère.

R : Le livre vise à montrer la caractérisation archétypale de ce que serait un Homme de Tradition, y compris - donc - les objectifs qu'il devrait s'efforcer d'atteindre, afin de servir de modèle à tous ceux de nos semblables qui aspirent à s'élever au-dessus de la médiocrité de l'homme moderne (et, plus encore, post-moderne), médiocrité qui est hégémonique en nos temps de dissolution. En gardant toujours à l'esprit quels sont les traits essentiels qui définissent l'Homme de Tradition, il sera possible d'aspirer, petit à petit, à se forger intérieurement ; avoir ce modèle comme miroir dans lequel se regarder (et qui sait s'il ne sera pas possible d'aspirer à ne pas écarter la possibilité d'opérer un renouvellement ontologique intérieur). La difficulté ou l'impossibilité de trouver, de nos jours, quelque maillon des chaînes initiatiques qui nous relient à la Sagesse de la Tradition Primordiale nous amène à donner une valeur particulière à ce qu'Evola appelle la "voie autonome de réalisation". Le contenu de ce livre peut peut-être aider dans une certaine mesure à faire en sorte que ce chemin ne soit pas une chimère.

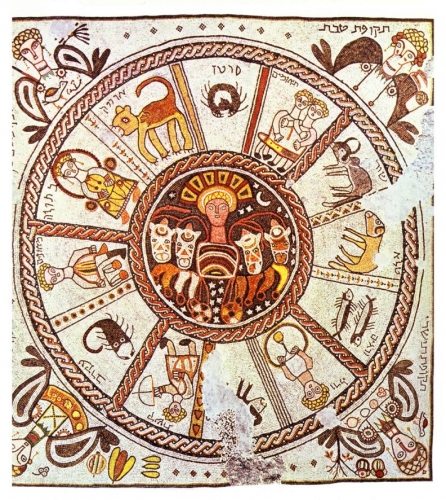

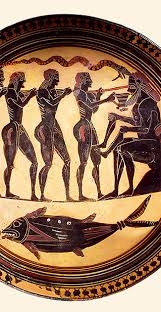

« On peut se demander si les migrations successives des foyers de civilisation ne sont pas réglées, elles aussi, par des lois mathématiques. Les foyers de civilisation se sont déplacés de l’Est vers l’Ouest, par exemple d’Our en Chaldée et Athènes à Paris. Ces trois villes se trouvent sur le même arc de cercle et les distances Our-Athènes et Athènes-Paris sont sensiblement égales de même que leurs apogées successives sont séparées par le même laps de temps de vingt et un siècles et demi environ [= la précession des équinoxes]. Ceci nous conduit à supposer que le déplacement du point vernal, parcourant les signes du Zodiaque en vingt et un siècle et demi, régit en même temps que les rythmes de civilisation, leurs déplacements successifs à la surface du globe. »

« On peut se demander si les migrations successives des foyers de civilisation ne sont pas réglées, elles aussi, par des lois mathématiques. Les foyers de civilisation se sont déplacés de l’Est vers l’Ouest, par exemple d’Our en Chaldée et Athènes à Paris. Ces trois villes se trouvent sur le même arc de cercle et les distances Our-Athènes et Athènes-Paris sont sensiblement égales de même que leurs apogées successives sont séparées par le même laps de temps de vingt et un siècles et demi environ [= la précession des équinoxes]. Ceci nous conduit à supposer que le déplacement du point vernal, parcourant les signes du Zodiaque en vingt et un siècle et demi, régit en même temps que les rythmes de civilisation, leurs déplacements successifs à la surface du globe. » « La vieille tradition se trompe : l’Occident n’est plus européen, et l’Europe n’est plus l’Occident. Dans sa marche vers l’ouest, le soleil de notre civilisation s’est terni. Parti d’Hellade, investissant l’Italie, puis l’Europe occidentale, puis l’Angleterre, et enfin, ayant traversé les mers, s’étant installé en Amérique, le centre de l’‘Occident’ s’est lentement défiguré. Aujourd’hui, comme le comprit Raymond Abellio, c’est la Californie qui s’est instaurée comme épicentre et comme essence de l’Occident. (…) L’Occident alors, dans un mouvement planétaire qui est d’ailleurs déjà commencé, continuera sa marche vers l’Ouest en installant son centre là où il se prépare déjà, dans l’extrême-est, dans les archipels de l’Océan Pacifique, du coté du Japon et des Indes orientales… C’est la réversion absolue du mouvement de traversée des mers parti d’Europe au XVIe siècle… »

« La vieille tradition se trompe : l’Occident n’est plus européen, et l’Europe n’est plus l’Occident. Dans sa marche vers l’ouest, le soleil de notre civilisation s’est terni. Parti d’Hellade, investissant l’Italie, puis l’Europe occidentale, puis l’Angleterre, et enfin, ayant traversé les mers, s’étant installé en Amérique, le centre de l’‘Occident’ s’est lentement défiguré. Aujourd’hui, comme le comprit Raymond Abellio, c’est la Californie qui s’est instaurée comme épicentre et comme essence de l’Occident. (…) L’Occident alors, dans un mouvement planétaire qui est d’ailleurs déjà commencé, continuera sa marche vers l’Ouest en installant son centre là où il se prépare déjà, dans l’extrême-est, dans les archipels de l’Océan Pacifique, du coté du Japon et des Indes orientales… C’est la réversion absolue du mouvement de traversée des mers parti d’Europe au XVIe siècle… »

Au sommaire du volume 1 :

Au sommaire du volume 1 : Je renvoie les lecteurs à mes fiches

Je renvoie les lecteurs à mes fiches  En 2018, j’ai publié un ouvrage qui est à la fois un pamphlet (par le ton) et un essai (par ses analyses et son appareil de notes abondant). Son titre résume bien les critiques que mes amis et moi adressons à la DR française : De la confrérie des Bons Aryens à la nef des fous. Par « Bons Aryens », je vise bien sûr les bons à rien franco-gaulois et leurs tares apparemment inguérissables : le « réalisme » à courte vue de ceux qui, pourtant cocufiés tous les dix ou vingt ans à ce petit jeu, s’imaginent encore que le commencement du salut viendra de la politique ; la frivolité et la futilité typiquement françaises, héritées des salons de la noblesse décadente d’Ancien Régime et sur lesquelles Abel Bonnard et Céline ont écrit des lignes féroces, mais justes ; le manque de soubassement historique (la France n’a pas connu de vrai mouvement fasciste, mais seulement des intellectuels fascistes, le seul mouvement sérieux dans le paysage ayant été le PPF, d’ascendance communiste comme par hasard) ; l’anti-intellectualisme (le pseudo-fascisme français est avant tout littéraire) et l’indifférence méprisante à la formation doctrinale ; l’esthétisme à corps perdu, stéréotypé et envahissant, façon typiquement bourgeoise de se donner une posture — mais seulement une posture — de révolutionnaire, et qui est une pathologie du « connaître par sensation immédiate », antérieurement à tout discours (c’est le sens même du terme « esthétique »), comme l’idéologie est une projection pathologique et passionnelle de la subjectivité.

En 2018, j’ai publié un ouvrage qui est à la fois un pamphlet (par le ton) et un essai (par ses analyses et son appareil de notes abondant). Son titre résume bien les critiques que mes amis et moi adressons à la DR française : De la confrérie des Bons Aryens à la nef des fous. Par « Bons Aryens », je vise bien sûr les bons à rien franco-gaulois et leurs tares apparemment inguérissables : le « réalisme » à courte vue de ceux qui, pourtant cocufiés tous les dix ou vingt ans à ce petit jeu, s’imaginent encore que le commencement du salut viendra de la politique ; la frivolité et la futilité typiquement françaises, héritées des salons de la noblesse décadente d’Ancien Régime et sur lesquelles Abel Bonnard et Céline ont écrit des lignes féroces, mais justes ; le manque de soubassement historique (la France n’a pas connu de vrai mouvement fasciste, mais seulement des intellectuels fascistes, le seul mouvement sérieux dans le paysage ayant été le PPF, d’ascendance communiste comme par hasard) ; l’anti-intellectualisme (le pseudo-fascisme français est avant tout littéraire) et l’indifférence méprisante à la formation doctrinale ; l’esthétisme à corps perdu, stéréotypé et envahissant, façon typiquement bourgeoise de se donner une posture — mais seulement une posture — de révolutionnaire, et qui est une pathologie du « connaître par sensation immédiate », antérieurement à tout discours (c’est le sens même du terme « esthétique »), comme l’idéologie est une projection pathologique et passionnelle de la subjectivité. Or, avec Sparta nous entendons précisément renouer avec des formes de vraie critique sociale, au lieu du « on nous cache tout, on nous dit rien » d’aujourd’hui, beaucoup moins drôle que la chanson de Jacques Dutronc qui avait égayé la fin de mon adolescence. Alors que la DR franco-gauloise s’est ruée goulûment sur l’Internet et ses innombrables poubelles psychiques — soit pour y fouiller, soit encore pour les remplir à son tour —, nous entendons développer une critique argumentée de la pénétration invasive du « tout-numérique » dans la vie quotidienne et de ses conséquences sur le plan anthropologique. Cela nous permettra de bien mettre en relief la tare majeure, en plus de celles déjà énumérées, de la DR franco-gauloise : un énorme « déficit d’incarnation » entre les idées supposément défendues et la vie casanière et bourgeoise de tant de soi-disant « antimodernes » qui n’ont pas compris que, fondamentalement, le monde moderne est une gigantesque entreprise d’avilissement de l’humain, autrement dit, en termes nietzschéens, une usine à fabriquer le « Dernier Homme », lequel, en dépit (ou à cause ?) des prothèses technologiques qui l’entourent, relève d’une forme de sous-humanité. À ce sujet, la vertu de probité chère à Nietzsche oblige à reconnaître que l’on observe bien plus de cohérence chez certains libertaires et certains héritiers de l’Internationale situationniste – je pense en particulier au groupe réuni autour des éditions L’Échappée, déjà en pointe il y a quelques années dans la défense de l’objet-livre face à la barbarie internétique. Les vrais « réactionnaires », au meilleur sens du terme, ne sont en effet pas toujours là où l’on s’attend à les trouver…

Or, avec Sparta nous entendons précisément renouer avec des formes de vraie critique sociale, au lieu du « on nous cache tout, on nous dit rien » d’aujourd’hui, beaucoup moins drôle que la chanson de Jacques Dutronc qui avait égayé la fin de mon adolescence. Alors que la DR franco-gauloise s’est ruée goulûment sur l’Internet et ses innombrables poubelles psychiques — soit pour y fouiller, soit encore pour les remplir à son tour —, nous entendons développer une critique argumentée de la pénétration invasive du « tout-numérique » dans la vie quotidienne et de ses conséquences sur le plan anthropologique. Cela nous permettra de bien mettre en relief la tare majeure, en plus de celles déjà énumérées, de la DR franco-gauloise : un énorme « déficit d’incarnation » entre les idées supposément défendues et la vie casanière et bourgeoise de tant de soi-disant « antimodernes » qui n’ont pas compris que, fondamentalement, le monde moderne est une gigantesque entreprise d’avilissement de l’humain, autrement dit, en termes nietzschéens, une usine à fabriquer le « Dernier Homme », lequel, en dépit (ou à cause ?) des prothèses technologiques qui l’entourent, relève d’une forme de sous-humanité. À ce sujet, la vertu de probité chère à Nietzsche oblige à reconnaître que l’on observe bien plus de cohérence chez certains libertaires et certains héritiers de l’Internationale situationniste – je pense en particulier au groupe réuni autour des éditions L’Échappée, déjà en pointe il y a quelques années dans la défense de l’objet-livre face à la barbarie internétique. Les vrais « réactionnaires », au meilleur sens du terme, ne sont en effet pas toujours là où l’on s’attend à les trouver…

J’ai également rédigé pour cette première livraison une très longue étude sur « le mythologue du romantisme », à savoir le Suisse Johann J. Bachofen (1815-1887), qui croisa Nietzsche à l’université de Bâle. Encore trop peu connu en France, Bachofen bénéficia pourtant d’une « réception » considérable : il est établi qu’il fut lu par des esprits aussi différents que Friedrich Engels, Walter Benjamin, Thomas Mann, Robert Musil, Hermann Hesse, Baeumler, Rosenberg et Klages, sans oublier le grand helléniste Walter F. Otto et, bien sûr, Julius Evola. Notre dossier sur Bachofen comprend d’ailleurs des textes d’Evola sur l’auteur suisse. L’Italie est encore à l’honneur avec plusieurs textes d’un sociologue de l’art italien consacrés à l’histoire de la subversion organisée des arts visuels en Occident par des « avant-gardes » nihilistes. Cette première livraison contient également un article de J. Haudry sur la notion grecque d’aidôs, terme souvent rendu par « retenue, pudeur », mais qui connote aussi le sens de « respect, révérence » envers sa propre conscience et ceux à qui l’on est uni par des devoirs réciproques ; un témoignage de Pierre Krebs sur le mouvement national-révolutionnaire allemand Der Dritte Weg, dont les méthodes ne sont pas sans rappeler celles du mouvement romain Casa Pound ; un article inédit d’Evola sur la véritable signification de l’« antimilitarisme » des nations victorieuses à l’issue de la Seconde Guerre mondiale ; et un index pour se repérer dans toute cette matière.

J’ai également rédigé pour cette première livraison une très longue étude sur « le mythologue du romantisme », à savoir le Suisse Johann J. Bachofen (1815-1887), qui croisa Nietzsche à l’université de Bâle. Encore trop peu connu en France, Bachofen bénéficia pourtant d’une « réception » considérable : il est établi qu’il fut lu par des esprits aussi différents que Friedrich Engels, Walter Benjamin, Thomas Mann, Robert Musil, Hermann Hesse, Baeumler, Rosenberg et Klages, sans oublier le grand helléniste Walter F. Otto et, bien sûr, Julius Evola. Notre dossier sur Bachofen comprend d’ailleurs des textes d’Evola sur l’auteur suisse. L’Italie est encore à l’honneur avec plusieurs textes d’un sociologue de l’art italien consacrés à l’histoire de la subversion organisée des arts visuels en Occident par des « avant-gardes » nihilistes. Cette première livraison contient également un article de J. Haudry sur la notion grecque d’aidôs, terme souvent rendu par « retenue, pudeur », mais qui connote aussi le sens de « respect, révérence » envers sa propre conscience et ceux à qui l’on est uni par des devoirs réciproques ; un témoignage de Pierre Krebs sur le mouvement national-révolutionnaire allemand Der Dritte Weg, dont les méthodes ne sont pas sans rappeler celles du mouvement romain Casa Pound ; un article inédit d’Evola sur la véritable signification de l’« antimilitarisme » des nations victorieuses à l’issue de la Seconde Guerre mondiale ; et un index pour se repérer dans toute cette matière.

« [En Inde, juste avant l’apparition du bouddhisme] La civilisation la plus élevée qu’un peuple puisse atteindre dans un état ordonnancé était atteinte. La loi et le droit réglaient la vie des membres de l’Etat. La division du peuple en castes indiquait à chacun la voie de sa vie. Le trône des princes était environné de pompe et de luxe ; la caste des prêtres et celle des guerriers étaient près du trône et menaient une vie confortable, aux dépens du peuple, il est vrai ; cependant les castes des artisans, des commerçants et des agriculteurs avaient leurs cercles juridiques qui leur étaient garantis par la loi et dans l’intérieur desquels elles pouvaient se mouvoir librement. Il y avait bien de nombreuses castes inférieures, castes de serviteurs dont la vie se passait à travailler pour d’autres, mais on consolait ces castes par des promesses religieuses, de sorte que ça et là un rayon d’espoir, une divine étincelle de joie, tombait sur la misère de leur vie. »

« [En Inde, juste avant l’apparition du bouddhisme] La civilisation la plus élevée qu’un peuple puisse atteindre dans un état ordonnancé était atteinte. La loi et le droit réglaient la vie des membres de l’Etat. La division du peuple en castes indiquait à chacun la voie de sa vie. Le trône des princes était environné de pompe et de luxe ; la caste des prêtres et celle des guerriers étaient près du trône et menaient une vie confortable, aux dépens du peuple, il est vrai ; cependant les castes des artisans, des commerçants et des agriculteurs avaient leurs cercles juridiques qui leur étaient garantis par la loi et dans l’intérieur desquels elles pouvaient se mouvoir librement. Il y avait bien de nombreuses castes inférieures, castes de serviteurs dont la vie se passait à travailler pour d’autres, mais on consolait ces castes par des promesses religieuses, de sorte que ça et là un rayon d’espoir, une divine étincelle de joie, tombait sur la misère de leur vie. » « Il y a là plus que des classes, qui sont une dégradation économique et matérialiste ; les castes reflètent un ordre métaphysique où chaque individu accomplit sa fonction selon sa vraie volonté – ou devoir, dharma – en tant que manifestation de l’ordre cosmique. Pour les fidèles de la Tradition Pérenne, la caste est une manifestation de l’ordre divin et pas seulement une division économique du travail en vue d’une grossière exploitation. »

« Il y a là plus que des classes, qui sont une dégradation économique et matérialiste ; les castes reflètent un ordre métaphysique où chaque individu accomplit sa fonction selon sa vraie volonté – ou devoir, dharma – en tant que manifestation de l’ordre cosmique. Pour les fidèles de la Tradition Pérenne, la caste est une manifestation de l’ordre divin et pas seulement une division économique du travail en vue d’une grossière exploitation. »

« Le premier devoir est de combattre pour la restauration de l’Ordre. Pas tel ou tel Ordre particulier, telle ou telle formule politique contingente, mais l’Ordre sans adjectifs, la hiérarchie immuable des pouvoirs spirituels à l’intérieur de l’individu et de l’Etat qui place au sommet ceux qui sont ascétiques, héroïques et politiques et au-dessous ceux qui sont simplement économiques et administratifs. »

« Le premier devoir est de combattre pour la restauration de l’Ordre. Pas tel ou tel Ordre particulier, telle ou telle formule politique contingente, mais l’Ordre sans adjectifs, la hiérarchie immuable des pouvoirs spirituels à l’intérieur de l’individu et de l’Etat qui place au sommet ceux qui sont ascétiques, héroïques et politiques et au-dessous ceux qui sont simplement économiques et administratifs. » L’espace, la terre, le territoire, la zone de contrôle et d’influence constituent le contenu corporel de l’Empire et correspondent au corps de l’homme. (…) Le peuple correspond à l’âme ; il vit et se déplace, aime et déteste, tombe et se relève, s’envole et souffre. (…) La religion correspond à l’esprit. Elle montre des perspectives montagneuses, elle assure le contact avec l’éternité, elle dirige le regard vers le ciel.

L’espace, la terre, le territoire, la zone de contrôle et d’influence constituent le contenu corporel de l’Empire et correspondent au corps de l’homme. (…) Le peuple correspond à l’âme ; il vit et se déplace, aime et déteste, tombe et se relève, s’envole et souffre. (…) La religion correspond à l’esprit. Elle montre des perspectives montagneuses, elle assure le contact avec l’éternité, elle dirige le regard vers le ciel. « …la Russie nouvelle est une démocratie de type ‘gaullien’ avec des libertés, des élections, l’ouverture sur l’étranger mais la hiérarchie des trois fonctions a été rétablie. C’est une démocratie ‘tripartitionnelle’, différente du totalitarisme communiste qui avait détruit la troisième fonction, et différente de l’Occident dominé par le Gestell qui entraîne la dégénérescence des deux premières fonctions de souveraineté et militaire. En Russie, on est en économie libre de marché mais la primauté de la fonction de souveraineté est rétablie, et la fonction de défense est réévaluée dans la vie sociale. »

« …la Russie nouvelle est une démocratie de type ‘gaullien’ avec des libertés, des élections, l’ouverture sur l’étranger mais la hiérarchie des trois fonctions a été rétablie. C’est une démocratie ‘tripartitionnelle’, différente du totalitarisme communiste qui avait détruit la troisième fonction, et différente de l’Occident dominé par le Gestell qui entraîne la dégénérescence des deux premières fonctions de souveraineté et militaire. En Russie, on est en économie libre de marché mais la primauté de la fonction de souveraineté est rétablie, et la fonction de défense est réévaluée dans la vie sociale. »

Dans Liquid Modernity, le sociologue polonais Zygmunt Bauman décrit comment la politique des Lumières a voulu éroder ce qui était devenu statique et oppressif. L'idée était qu'une fois l'ancien régime ruiné, de nouveaux systèmes, plus équitables et plus gratifiants, seraient mis en place. Mais ce n'est pas ce qui s'est passé. L'acide corrosif a continué à désintégrer tout ce qu'il touche, de sorte que nous avons maintenant une "modernité liquide", une modernité où tout est léger, fugace, fluide, mutant, autodestructeur, et peut-être surtout, dénué de sens.

Dans Liquid Modernity, le sociologue polonais Zygmunt Bauman décrit comment la politique des Lumières a voulu éroder ce qui était devenu statique et oppressif. L'idée était qu'une fois l'ancien régime ruiné, de nouveaux systèmes, plus équitables et plus gratifiants, seraient mis en place. Mais ce n'est pas ce qui s'est passé. L'acide corrosif a continué à désintégrer tout ce qu'il touche, de sorte que nous avons maintenant une "modernité liquide", une modernité où tout est léger, fugace, fluide, mutant, autodestructeur, et peut-être surtout, dénué de sens.

Ces différences favorisent des lectures non point opposées, ni exclusives l'une de l'autre, mais complémentaires. A l'exception du Travailleur, livre qui définit de façon presque didactique l'émergence d'un Type, Jünger demeure fidèle à ce cheminement que l'on peut définir, avec une grande prudence, comme « romantique » et dont la caractéristique dominante n'est certes point l'effusion sentimentale mais la nature déambulatoire, le goût des sentes forestières, ces « chemins qui ne mènent nulle part » qu'affectionnait Heidegger, à la suite d'Heinrich von Ofterdingen et du « voyageur » de Gènes, de Venise et d'Engadine, toujours accompagné d'une « ombre » qui n'est point celle du désespoir, ni du doute, mais sans doute l'ombre de la Mesure qui suit la marche de ces hommes qui vont vers le soleil sans craindre la démesure.

Ces différences favorisent des lectures non point opposées, ni exclusives l'une de l'autre, mais complémentaires. A l'exception du Travailleur, livre qui définit de façon presque didactique l'émergence d'un Type, Jünger demeure fidèle à ce cheminement que l'on peut définir, avec une grande prudence, comme « romantique » et dont la caractéristique dominante n'est certes point l'effusion sentimentale mais la nature déambulatoire, le goût des sentes forestières, ces « chemins qui ne mènent nulle part » qu'affectionnait Heidegger, à la suite d'Heinrich von Ofterdingen et du « voyageur » de Gènes, de Venise et d'Engadine, toujours accompagné d'une « ombre » qui n'est point celle du désespoir, ni du doute, mais sans doute l'ombre de la Mesure qui suit la marche de ces hommes qui vont vers le soleil sans craindre la démesure.

Qu'est-ce que la Figure ? La Figure, nous dit Jünger, est le tout qui englobe plus que la somme des parties. C'est en ce sens que la Figure échappe au déterminisme, qu'il soit économique ou biologique. L'individu du matérialisme libéral demeure soumis au déterminisme, et de ce fait, il appartient encore au monde animal, au « biologique ». Tout ce qui s'explique en terme de logique linéaire, déterministe, appartient encore à la nature, à l'en-deçà des possibilités surhumaines qui sont le propre de l'humanitas. « L'ordre hiérarchique dans le domaine de la Figure ne résulte pas de la loi de cause et d'effet, écrit Jünger mais d'une loi tout autre, celle du sceau et de l'empreinte. » Par ce renversement herméneutique décisif, la pensée de Jünger s'avère beaucoup plus proche de celle d'Evola que l'on ne pourrait le croire de prime abord. Dans le monde hiérarchique, que décrit Jünger où le monde obéit à la loi du sceau et de l'empreinte, les logiques évolutionnistes ou progressistes, qui s'obstinent (comme le nazisme ou le libéralisme darwinien) dans une vision zoologique du genre humain, perdent toute signification. Telle est exactement la Tradition, à laquelle se réfère toute l'œuvre de Julius Evola: « Pour comprendre aussi bien l'esprit traditionnel que la civilisation moderne, en tant que négation de cet esprit, écrit Julius Evola, il faut partir de cette base fondamentale qu'est l'enseignement relatif aux deux natures. Il y a un ordre physique et il y a un ordre métaphysique. Il y a une nature mortelle et il y a la nature des immortels. Il y a la région supérieure de l'être et il y a la région inférieure du devenir. D'une manière plus générale, il y a un visible et un tangible, et avant et au delà de celui-ci, il y a un invisible et un intangible, qui constituent le supra-monde, le principe et la véritable vie. Partout, dans le monde de la Tradition, en Orient et en Occident, sous une forme ou sous une autre, cette connaissance a toujours été présente comme un axe inébranlable autour duquel tout le reste était hiérarchiquement organisé. »

Qu'est-ce que la Figure ? La Figure, nous dit Jünger, est le tout qui englobe plus que la somme des parties. C'est en ce sens que la Figure échappe au déterminisme, qu'il soit économique ou biologique. L'individu du matérialisme libéral demeure soumis au déterminisme, et de ce fait, il appartient encore au monde animal, au « biologique ». Tout ce qui s'explique en terme de logique linéaire, déterministe, appartient encore à la nature, à l'en-deçà des possibilités surhumaines qui sont le propre de l'humanitas. « L'ordre hiérarchique dans le domaine de la Figure ne résulte pas de la loi de cause et d'effet, écrit Jünger mais d'une loi tout autre, celle du sceau et de l'empreinte. » Par ce renversement herméneutique décisif, la pensée de Jünger s'avère beaucoup plus proche de celle d'Evola que l'on ne pourrait le croire de prime abord. Dans le monde hiérarchique, que décrit Jünger où le monde obéit à la loi du sceau et de l'empreinte, les logiques évolutionnistes ou progressistes, qui s'obstinent (comme le nazisme ou le libéralisme darwinien) dans une vision zoologique du genre humain, perdent toute signification. Telle est exactement la Tradition, à laquelle se réfère toute l'œuvre de Julius Evola: « Pour comprendre aussi bien l'esprit traditionnel que la civilisation moderne, en tant que négation de cet esprit, écrit Julius Evola, il faut partir de cette base fondamentale qu'est l'enseignement relatif aux deux natures. Il y a un ordre physique et il y a un ordre métaphysique. Il y a une nature mortelle et il y a la nature des immortels. Il y a la région supérieure de l'être et il y a la région inférieure du devenir. D'une manière plus générale, il y a un visible et un tangible, et avant et au delà de celui-ci, il y a un invisible et un intangible, qui constituent le supra-monde, le principe et la véritable vie. Partout, dans le monde de la Tradition, en Orient et en Occident, sous une forme ou sous une autre, cette connaissance a toujours été présente comme un axe inébranlable autour duquel tout le reste était hiérarchiquement organisé. »

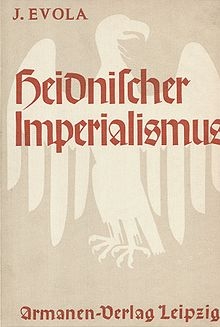

Julius Evola n'était ni "fasciste" ni "antifasciste" (comme il l'écrivait de façon polémique dans sa revue bimensuelle "La Torre" au début de 1930), et par conséquent il n'était ni "nazi" ni "anti-nazi" : était-il alors un incertain, un attentiste, un hypocrite, un - comme on le dit en Italie - "un poisson dans un tonneau" ? Non: il a accepté les idées, les thèses, les positions, les attitudes et les choix pratiques du fascisme, et donc du nazisme, qui étaient en accord avec ceux d'une droite traditionnelle et, plus tard, de ce que l'on a appelé la révolution conservatrice allemande. Une vision qui était à l'époque gibeline, impériale, aristocratique, qui - même si elle est "utopique" - l'éloignait certes de la Weltanschauung populiste "démocratique" et "plébéienne" du fascisme mais surtout du nazisme, dont le matérialisme biologique lui était totalement insupportable. Il ne s'agit pas de justifications a posteriori, comme quelqu'un l'a malicieusement pensé en lisant les pages de Il cammino del cinabro (1963), car Evola n'est pas ce qu'on appelle aujourd'hui un "repenti" : il n'a jamais rien répudié ni rejeté de son passé ; même s'il a rectifié et pris ses distances par rapport à certaines de ses positions de jeunesse (tout le monde oublie ce qu'il a écrit sur l'impérialisme païen en 1928 : "Dans le livre, dans la mesure où il suivait - je dois le reconnaître - l'impulsion d'une pensée radicaliste faisant usage d'un style violent, il était typique d’une absence juvénile de mesure et de sens politique et à une utopique inconscience de l'état des choses" : non pas "le repentir" mais la maturation logique d'un homme de pensée). Le fait que ce ne sont pas des justifications est démontré par les documents qui, au fil des ans, après sa mort en 1974, sont lentement apparus dans les archives publiques et privées italiennes et allemandes. D'eux émerge un Julius Evola qui était tout sauf "organique au régime" comme on l'a écrit, mais même pas aussi marginal qu'on le croyait : un essayiste, journaliste, polémiste, conférencier, qui a connu des hauts et des bas et qui, après la crise de 1930 avec l’interdiction de "La Torre" et sa marginalisation, a accepté de se rapprocher de personnalités comme Giovanni Preziosi, Roberto Farinacci, Italo Balbo, c'est-à-dire, on pourrait dire, les fascistes les plus "révolutionnaires" et les plus "intransigeants", afin d'exprimer ses idées critiques à l'abri de ces niches, agissant comme une sorte de "cinquième colonne" traditionaliste pour tenter l'entreprise utopique de "rectifier" le Régime dans ce sens : Il commence donc à écrire à partir de mars 1931 dans "La Vita Italiana", à partir de janvier 1933 dans "Il Corriere Padano" et "Il Regine Fascista", puis - sortant du "ghetto" des disgraciés - à partir d'avril 1933 dans "La Rassegna Italiana", à partir de février 1934 dans la revue d’inspiration autoritaire "Lo Stato" et dans "Roma", à partir de mars 1934 dans "Bibliografia Fascista".