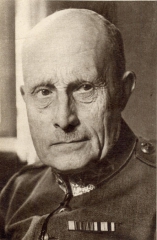

Ernesto Psichari.

Biografía de un centurión.

Sebastián Sánchez.

Profesor y Doctor en Historia. Universidad Católica de Salta. IES Santa María (Argentina).

Ex: http://www.revistalarazonhistorica.com

A dos centuriones de mi Patria:

En el Cuartel Celeste, al Teniente Roberto Estévez

Y aquí, mientras resiste la iniquidad, al Coronel Horacio Losito

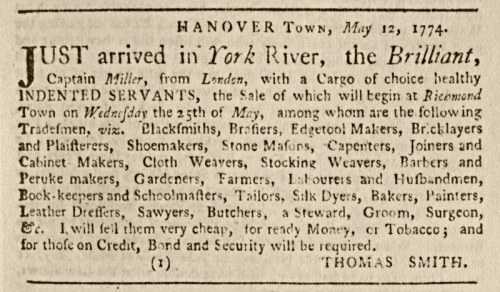

Amanece en Saint Vincent Rossignol, allí donde el Sambre fluye en dos cristalinas vertientes que, internadas en el valle boscoso, parecen transitar hacia la eternidad. En el centro de ambos declives –afeando el paisaje- se alzan las minas de carbón y las industrias del acero que le dan al paraje el nombre de Pays Noir.

Pero esta otrora briosa angostura, cuyas sombras disipa el naciente sol estival, es ahora un gris lodazal cubierto de cadáveres –hombres y bestias-, cráteres, restos de hierro y arboles retorcidos y chamuscados por las explosiones.

Es que franceses y alemanes llevan dos días masacrándose aquí, prolongando la contienda a lo largo del río, en una extensa línea que enfrenta al Ejército francés del general Lanrezac contra dos divisiones del ejército alemán, comandadas por el rudo general von Bülow.

El ataque, que ha principiado cuando el ejército teutón cruza el río y embiste frontalmente a los franceses, pronto se inclina a favor de los primeros. Lanrezac, en una acción que le costará ser degradado, no tiene más alternativa que ordenar la retirada.

Muchas horas lleva la lucha y, tras mil disparos, la artillería francesa que protege el repliegue está al borde del desmayo. Sólo unas pocas baterías de los viejos Soixante quinze del 75 retrasan el ataque intentando evitar la masacre de sus camaradas. Al fin, sólo truenan unos pocos cañones, disparando sin pausa, mientras se reemplaza a los servidores de cada pieza conforme caen por el fuego enemigo.

Allí, junto a su batería, protegiendo el flanco derecho de su regimiento, el teniente Ernest Psichari observa el campo de batalla con gesto grave y silencioso. Es enjuto y la gruesa casaca del uniforme parece irle un poco grande. Lleva fino el bigote, con las puntas terminadas en breve rizo. Las pobladas cejas enmarcan los ojos achinados por el cansancio. Tiene la mandíbula apretada en rictus intenso.

Ernest piensa en sus escasos artilleros y en el enemigo que ya se atisba a simple vista. A eso -¡nada menos!- se reduce ahora su mundo: sus hombres y los alemanes, a los que no odia en absoluto, más allá del esfuerzo que ahora hacen por acabar con su vida.

Ernest nada quiere saber acerca de los sutiles estrategas –o quizás no tanto- que lo han llevado hasta allí. No conoce de estados mayores ni mesas de arena. Es un oficial subalterno, veterano de cien entreveros contra los saharauis en las dunas del Tagant y entre los peñascos del Adrar.

Esta madrugada de verano Ernest es el hombre que ha llegado a ser luego de infinitos combates interiores. Es el hombre de los tres amores: Dios, la Patria y su familia, incluyendo en ella a sus hombres. A ellos dirige ahora una mirada, a sus animosos artilleros que –entre disparos- buscan sus ojos esperando una orden, una mirada de aprobación, una breve arenga. Le miran anhelantes de certezas, mientras musitan entre dientes su admiración al verlo erguido, sin miedo aparente a los proyectiles que estallan cada vez más cerca. Le admiran de tal modo que no prestan atención a sus manos y brazos quemados por el cañón, ni a la sed que los abrasa, ni al enemigo implacable que no ceja en su avance. Un temor supera a todos los demás: faltar al jefe.

De improviso, el silencio se apodera del campo de batalla. Ernest entorna los ojos. Con el instinto del soldado veterano sabe que aquél silencio significa la inminencia del asalto final. Serenamente, ante la expectación de los hombres, desenvaina su sable. Es un centurión y sabe que en ocasiones la verdad sólo esplende en el filo de una espada. Luego se persigna lentamente, mira con gesto marcial a los servidores y ordena ¡fuego!

Entonces todo estalla en infernal vorágine: los alemanes cada vez más cerca, explosiones de derredor, gritos de heridos y moribundos, imprecaciones, gemidos de angustia y él, Ernest, conmovido ante aquél espectáculo humano supremo, con la verdad manifiesta en todas sus dimensiones, ordena el fuego, vocifera vivas a Francia, asiste a los heridos, musita un Avemaría, exhorta a sus agobiados milites. Y así durante dos horas, hasta que la bala, que impacta en su sien, le asesta el golpe glorioso del final. Trastabilla y cae lentamente sobre la cureña del cañón, firme el puño en la empuñadura del sable, envuelta la muñeca en el Rosario de Nuestra Señora. Al llegar al suelo ya ha muerto. Es el 22 de agosto de 1914. Ernest Psichari ha finalizado su duro peregrinaje. Ha partido a la Casa del Padre.

I

De la cuna a las armas

El padre. La familia y la crianza.

Al llegar a Francia junto a su familia, Yanin Psijari tiene catorce años. Ha nacido el año 1854 en Odessa, que por entonces pertenecía a Rusia, pero los suyos son originarios de la isla griega de Quíos, encavada en el Egeo. Su padre, Nicolás, próspero comerciante, ha decidido migrar entusiasmado por la cultura francesa. Su madre, de la familia Biazi Mavro y devota cristiana, le ha criado en la fe de la Iglesia Ortodoxa.

Pero el joven Yanin, que cursa sus estudios en el Liceo Thiers de Marsella, no tarda en desembarazarse de la fe materna y homologarse con el ambiente del siglo francés. Ha comenzado por afrancesar su nombre: ahora se llama Jean Psichari. En 1880 obtiene su licence és lettre con mención en latín, griego y francés. Disciplinado y voluntarioso, ávido de logros académicos, prosigue sus estudios en la École Pratique des Hautes Etudes, donde es discípulo de Louis Havet, Weill y Tournier, entre otros maestros del momento.

En la École sobresale por su condición de políglota (conoce con profundidad latín, alemán, italiano, turco y hebreo, además del francés y el griego natal) y pronto se distingue en filología. Con rapidez llega a ocupar la cátedra de filología bizantina y neogriega. Más tarde será rector de la École y profesor de la Escuela de Estudios Orientales. Merced a su ubicuidad en el siglo, no tarda en llegarle el reconocimiento de los cenáculos intelectuales.

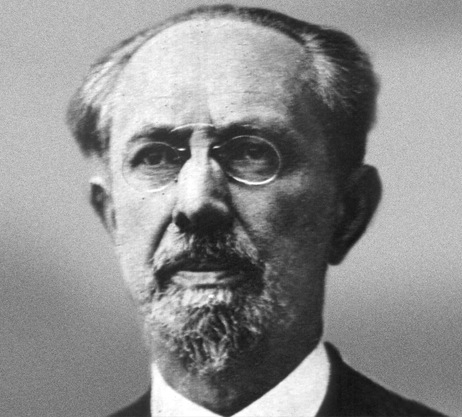

Pero el gran espaldarazo para su ascenso académico y social le llega por una vía distinta. En 1882 conoce a Naomi, la hija de Ernest Renan. Enseguida el famoso apóstata -que ya ha publicado su Vie de Jésus, (financiada por el Barón de Rotschild) y es vanagloriado por toda la progresía intelectual francesa- le acoge como un hijo y le abre las puertas a los clubes y logias, asegurándole un futuro académico promisorio.

De ese matrimonio nacen cuatro hijos: Ernest, que nace en 1883; Henriette (1884), más tarde biógrafa de la familia; Michel (1887) que muy joven se casó con una hija de Anatole France y murió en el Frente Occidental en enero de 1917 y la más pequeña, dilecta de nuestro Ernest, Corrie (1894).

Los Psichari deciden para sus hijos una educación sin Dios, de modo que Ernest conoce el interior de una iglesia siendo adulto. Sin embargo, para consolar a la abuela paterna, Jean aprueba que Ernest sea bautizado. Se realiza el sacramento según el rito ortodoxo -por lo cual es válido para la Iglesia- y tal como señala la tradición la abuela regala al bebe una pequeña cruz de metal que, treinta años después, recibirá de manos de su madre, poco antes de partir al frente belga.

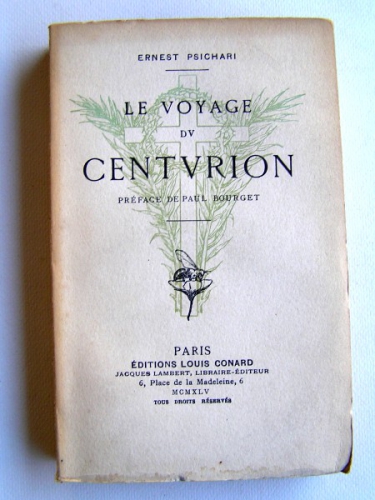

En El Viaje del Centurión, su obra cumbre concluida poco antes de morir, habla Ernest de su padre. Le hace allí militar, cosa que nunca fue, pero por lo demás la descripción se ajusta a la visión que de él tenía. Así, Maxencio, el protagonista y su alter ego, “era hijo de un coronel, hombre culto, de ideas más que volterianas, traductor de Horacio, anciano excelente y honrado, hombre, en fin, de buenas maneras”.

Con rigidez, Jean dicta a su primogénito, de sólo seis años, lecciones diarias de retórica y gramática, pero escatima los gestos afectuosos. Pues, si es cierto que los esposos Psichari comparten la idea de educar a sus hijos en un ambiente profano, no lo es menos que Naomi es una madre atenta y tierna que siente un amor incondicional por sus hijos. Hasta dos días antes de morir, Ernest le dirigirá bellísimas cartas pletóricas de ternura. Por su lado, Jean, radical en esto como en todo lo demás, educa a sus hijos en un ambiente riguroso y voluntarista en el que “las flaquezas infantiles eran vivamente reprendidas, en el que el estímulo se medía por el valor del esfuerzo”.

Puedo jactarme de tener un temperamento de hierro -escribe a su padre un jovencísimo Ernest- ¡Seamos fuertes y seamos grandes! No se trata de lloriquear, sino combatir; eso es lo que tú haces y eso lo que yo haré.

La severidad carente de afecto fortaleció su voluntad pero no su espíritu pues “su padre había alimentado su inteligencia, pero no su alma. Las primeras inquietudes de su juventud le hallaron desarmado, sin defensa contra el mal, sin protección contra los sofismas y los engaños del mundo”.

De este modo -en esa orfandad de creencias, acerrojado en la oscuridad de la ideología- Ernest transita accidentadamente sus años adolescentes.

Educación modernista

En semejante contexto, es lógico que Ernest siga el derrotero intelectual señalado por su padre y su abuelo. Hace sus primeras letras en el Liceo Montaigne y más tarde en el Liceo Henri IV donde aprende los rudimentos del latín. Luego comienza el estudio sistemático del griego, la lengua que también se habla en su hogar.

Es el auge del cientificismo, de los Taine y Michelet, Larouse, Zola y Renan. Es el esplendor del racionalismo, la secularización y el naturalismo, del liberalismo ataviado de ciencia positiva. De modo que las instituciones educativas de la elite francesa confluyen en el positivismo “científico” emergente del caletre de Augusto Comte.

Por supuesto, el Liceo en el que estudia nuestro joven Ernest confluye en ese ambiente de positivista y se define por un fin concreto: el socavamiento de la tradición en el espíritu de sus alumnos. Las glorias del pasado, las ideas y creencias que sustancian a Francia, en suma todo el orden tradicional, ha de quedar desfigurado en el fárrago de la deformación ilustrada que etiqueta toda la tradición con la categoría de Ancien Regime.

Los efectos de dicha educación se ven claramente en nuestro joven: “¿Hay algo más hermoso para un país -pregunta retóricamente en carta a su padre- que producir hombres tales como los Picquart, los Havet, los Scheurer –Kestner, los Zola? ¡Qué enseñanza la de este asunto Dreyfuss!”.

Los efectos de dicha educación se ven claramente en nuestro joven: “¿Hay algo más hermoso para un país -pregunta retóricamente en carta a su padre- que producir hombres tales como los Picquart, los Havet, los Scheurer –Kestner, los Zola? ¡Qué enseñanza la de este asunto Dreyfuss!”.

Pues, ¿cómo no ha de dejar huella en el juicio de nuestro joven esa saturación ideológica que además, en el caso de Ernest, se complementa con una crianza de igual jaez? Una carta a su padre nos da muestra de ese sesgo: “¡Ah -exclama- si el pueblo no estuviera cruelmente envenenado como está, cuál no sería su nobleza! Pero ¡ay! El catolicismo y el clericalismo, el antisemitismo, la estrechez de ideas invaden a Francia”.

Y con el desorden de la inteligencia, llega el abandono de la voluntad, la entrega al frenesí de las pasiones. Con cierta ingenuidad -y un matiz de escondida tristeza- el joven Ernest justifica sus excesos:

Por cálculo, y por hedonismo, me entregaré a todos los torbellinos y borrascas de mi alma (…) dejo que la ola me invada, sin oponer resistencia. Qué me importan las tristezas, las desilusiones, los derrumbes del corazón si llego a conocer por un segundo tan sólo la dicha perfecta.

Tal el estado espiritual de nuestro héroe, apenas cumplidos los 19 años.

Amigos. Maritain

No obstante, más allá del agobio ideológico, la circunstancia escolar prodiga un motivo de gozo al joven Ernest pues traba amistad con uno de sus compañeros, un joven de familia protestante que blasona su agnosticismo con irreverencia. Se llama Jacques Maritain y mucho después será instrumento de la Providencia en la conversión de Ernest.

Los dos jóvenes entablan firme amistad. Es lógico pues ambos provienen de familias burguesas donde la increencia y el materialismo son el pan de cada día. Comulgan en intereses y preocupaciones, pero además poseen un temperamento parecido, con cierta oscilación entre la melancolía y el frenesí activista. Ernest, que huye de su padre cuanto puede, pasa largas temporadas en la rue de Rennes, donde está la casa de los Maritain. No tarda en establecer un fuerte lazo de amistad con la señora de la casa, Geneviéve Favre, mujer profundamente imbuida en el espíritu de la época, y que le prodiga especial afecto.

Son los años del affaire Dreyfuss y su mejunje ideológico de laicismo socialista, masónico y antimilitarista, en cuyo remolino se ve peligrosamente envuelto el jovencísimo Ernest. Con cierta audacia asiste a las reuniones que, convocadas por su padre, incluyen a dreifusards y miembros del grupo de Clemenceau y del periódico L’aurore. A pesar de sus pocos años Ernest no duda -haciendo gala de un fuerte temperamento- en expresarse en tales tertulias pero “sus opiniones se corresponden absolutamente con la época y los ánimos del salón”.

Lee y estudia sin pausa. A instancias de uno de sus profesores, el reputado filósofo judío León Brunschvicg, frecuenta la lectura de Condocet, Spinoza, Fichte y Kant. Lee también a Descartes y a Pascal y pasa, sin solución de continuidad, del Dickens de “Tiempos difíciles” a “Mi juventud” de Michelet. Lee también a su abuelo, con emoción pero sin pasión pues no se impresiona con el “aparato crítico y científico” del autor de L’ Avenir de la Science. Ya maduro, llega a decirle a su amigo Maritain que “no había aprendido absolutamente nada con los libros de su abuelo”.

A sus veinte años y oscila entre la deriva y el afán del orden, los excesos y la búsqueda del sosiego, las amistades pérfidas y los amigos de ánimo noble. La crianza, la formación intelectual y el ambiente cultural en el que ha crecido han forjado en él un alma pagana. Formado entre clásicos y modernos, con prescindencia de lo cristiano, sufre lo que Molnar describe como la tentación pagana, es decir el “desafío periódico lanzado a la visión del mundo cristiano por los cultos y los mitos populares y por la teorías elaboradas en el seno de las elites”.

Pero esa mentalidad moderna, que le ha sido inoculada como un veneno, tiene según Belloc una característica esencial: la estupidez; pues “ese espíritu no piensa, y ¡esa es la verdaderamente extraña debilidad de algo que se llama a sí mismo una mentalidad!”.

Quizás por esa debilidad intrínseca Ernest recorre el obligado itinerario modernista con cierta inquietud y progresiva desconfianza. Es mucho lo que no le convence y su alma se encuentra próxima al hastío. Es el suyo un espíritu en búsqueda, en movimiento en pos de lo verdadero, que no permanece cómodo en la insolencia del error y la mentira.

Por esos primeros años del siglo -tal vez como prematuro testimonio de la náusea que le provoca la sofística racionalista- escribe sus primeros poemas, que permanecerán inéditos hasta muchos años después, cuando vean la luz editados por su hermana Henriette.

Colapso e inicio del peregrinaje

A poco de iniciar estudios universitarios sufre un colapso nervioso que lo aleja de todo y le postra durante un año. Le han abandonado las fuerzas, ya no posee el entusiasmo por la diatriba en los clubs, el frívolo regodeo del debate intelectual, la pasión por las lidias de los dreifusards.

Está agobiado por la pena, que es “el mayor de los desenfrenos”, según Péguy. Años después, ya católico, recordará esa época aludiendo al “lodo pestilente” en el que se ahogaba.

No menos que asombro producen los intentos de diversos autores por explicar este penoso pero fundacional episodio. A los que hablan de una decepción amorosa, se suman los que señalan stress estudiantil e incluso quienes, sin razón alguna y quizás con aviesa intención, aventuran el argumento de las tendencias homosexuales.

Sí existió una gran desilusión sentimental pues Ernest se enamoró de Jeanne Maritain, la hermana mayor de su amigo, sin ser correspondido. Pero no es suficiente explicación -ni ésta ni mucho menos las anteriores- para comprender el abatimiento que le abrumó durante ese tiempo. Bien miradas las cosas, no es tan difícil comprender este derrumbe de nuestro héroe. Baste comprender la metanoia que empieza a operarse en él. Sufre en carne viva la contradicción moral y espiritual que lo atormenta, la tensión entre el alma naturalmente cristiana -orientada ya en la búsqueda de la Verdad- y el pensamiento enjaulado neopagano, en el que ha sido formado. Se reconoce enfermo. Sabe que algo está mal, pero no puede adquirir la certeza de qué es: “Maxencio había sido educado lejos de la Iglesia. Era, pues, un enfermo que de ningún modo podía conocer el remedio”.

Aún no ha leído a Bloy pero más tarde sabrá con él que “Dios nos hace la gracia de no dejarnos impregnar por la tristeza, ella vagabundea solamente a nuestro en rededor”. Mientras combate la tristeza sin conocer aún la Alegría, lee ávidamente todo lo que llega a sus manos y sueña con otros horizontes, otros deberes, otras verdades.

La recuperación de la crisis espiritual le lleva largo tiempo pero, para cuando retoma sus estudios de filosofía, un cambio ineluctable se ha iniciado en él. Casi sin darse cuenta, ha iniciado su peregrinaje.

En 1900, luego de terminar sus estudios en el Condorcet, en las antiguas instalaciones del convento de los capuchinos de Saint-Louis-d'Antin, ingresa a la Sorbonne para estudiar filosofía. Junto a Maritain asiste en el College de France a los cursos de Bergson y queda impresionado por la reacción espiritualista ante el positivismo reinante.

El maestro. Péguy

No obstante, el gran acontecimiento de esos tiempos universitarios es la aparición de Charles Péguy, a quien siempre llamará “mi buen maestro”. Péguy, que es diez años mayor que él, ha fundado los Cahiers de la Quinzane en 1900 y es por esos días un reconocido publicista del socialismo.

Péguy, Maritain y Psichari, como tantos otros jóvenes de la época, son también exaltados dreifusards. Mas es necesario matizar aquí con las palabras de Eugenio D’Ors este dreyfusismo de Péguy y los suyos, incluyendo a Psichari: “fueron dreyfusistas porque en el dreyfusismo veían el instrumento para la realización de una sublime revolución moral. Fueron dreyfusistas por encontrar en el dreyfusismo un tema de religiosidad apto para dar contenido a las inspiraciones de orden ético que, recibidas de Proudhon sobre todo –y también del monarquismo y también del catolicismo- habían nutrido a aquellas juventud”. Diez años después, ya en manos de la izquierda y la masonería “que ocupaba el poder con todos los halagos, todos los compromisos, todas las tentaciones, todas las corrupciones, todos los abusos de poder “la revolución estaba ganada pero su religiosa espiritualidad, su exigencia moral, habían quedado en la puerta. Y, a esto, Charles Péguy llamaba traición”.

Esa traición, que trajo aparejado el profundo desengaño con los hombres e ideas que tan apasionadamente habían defendido, sumado a la soledad en que quedaron, fue una de las causas por las cuales Péguy y Psichari se acercan a la Iglesia -acercamiento casi total en el caso del primero, absoluto en el otro- y a un patriotismo por el que terminan ofrendando la vida en la Gran Guerra.

En esos años de enconadas luchas sociales y políticas, de largas noches de tertulias en la sede de los Cahiers, en la Rue de la Sorbonne, Péguy comienza a representar para Ernest una columna vertebradora, la oportunidad de volver la mirada hacia las cosas trascendentes, una sujeción cada vez más firme a lo real. Es que tiene “una sed terrible de lo concreto”, como dice en carta a la madre de Maritain.

La llegada de las armas

Pero la vida de Ernest continúa plagada de excesos, de búsqueda epicúrea, de frívolos, tormentosos y fútiles regodeos. Es cierto que ha pasado sin dificultad los estadios académicos pues bachillerato y licenciaturas, con la formación recibida en el hogar, le resultan sencillos. Pero, al mismo tiempo, vive en el desorden y la confusión, aturdiéndose con poesía rebelde, relativismo filosófico y moral y un ateísmo rayano con el nihilismo. Él mismo describe este estado con palabras claras que denotan no poca angustia:

Vorágine: vuelvo siempre a esta triste palabra vertiginosa! Torbellinos internos del alma e la inmovilidad, o torbellinos de la agitación exterior: en eso consiste mi vida (…) El ser se derrama hacia afuera, parecería que uno está vacío.

Tiene 21 años, ha terminado sus estudios de filosofía y tiene ante sí, asegurado, un promisorio futuro académico y social. Todo indica -su origen, su propia historia- que será un hombre de las logias puesto al servicio del Progreso para erradicar los resabios del “prefacio de la Humanidad”, como gustaba decir su abuelo.

Sin embargo, para sorpresa de todos, Ernest decide abandonarlo todo. Quiere dejar atrás a los falsos amigos, le urge desaparecer del ambiente de los poetastros de la rebeldía, las tertulias de la intelligentsia petulante, las noches del frenesí, los matinales remordimientos. Anhela una nueva vida, aventurera, emocionante…real. Quiere “alejarse de las fuerzas del desorden” pero no ve, no puede ver aún, si existe un Orden al cual encaminarse.

En carta a su padre explica los motivos aparentes que lo mueven a la vida militar, su “deseo de acción, lo que me gustaría salir de campaña, la satisfacción de tener hombres bajo mi mando, ejercer sobre ellos una autoridad firme y al mismo tiempo hacerme querer”. Pero también, casi como al pasar, habla de la milicia “como si fuera un poco una liberación para mí de la vida civil”.

Durante algún tiempo piensa en incorporarse a la escuela de oficiales de Saint Maixent o quizás a Saint Cyr. Por su condición social puede optar sin problemas. Sin embargo, a mediados de 1903 se une al Regimiento 51 de Infantería, en Beauvais, como simple soldado de segunda clase.

Pasa su primer año en Beauvais, iniciándose en la milicia y adaptándose al proverbial tedio -y a la rudeza- de la vida cuartelera. Durante ese tiempo escribe algo, pero lee mucho más, con un sosiego que le resulta inédito. Le roba horas al sueño -al ansiado descanso de todo soldado- para acudir a Bossuet y al releído Pascal.

Pero Ernest no quiere un destino en Francia. Le urge viajar, consolidarse como soldado en la marcha. Anhela un destino colonial donde vivir aventuras “concretas”. Por eso al cabo del año de instrucción solicita el reenganche por cinco años y es transferido al 1° Regimiento Colonial, con base en Lorient. Hasta ese momento, sus padres y hermanos han visto su incursión en la milicia como una suerte de capricho temporal, un desliz juvenil. Sin embargo, con su decisión de convertirse en soldado profesional, se produce un escándalo familiar y se profundiza la distancia con su padre.

En Lorient conoce a un oficial, “el ilustre jefe de escuadrón Lenfant”, que tanta influencia tendrá en su formación como soldado primero y como oficial más tarde. Pronto se cumple su deseo: Lenfant le requiere para una misión en el Congo. Ernest está feliz.

Ese destino colonial le permite escapar de Francia, alejarse “para siempre de las blasfemias y las imprecaciones proferidas con la cabeza echada hacia atrás y tambaleando la frente en un movimiento convulsivo”.

Ha cumplido veintidós años hastiado de vivir recorriendo “los jardines envenenados del vicio (…), perseguido por oscuros remordimientos, turbado ante la ponzoña de la mentira, abrumado bajo la horrible inanidad de una vida entregada al desorden de las ideas y los sentimientos”.

El Ernest que huye es un joven aventurero que prefiere errar por el mundo a quedarse atado a las miserias que impone el círculo que le rodea. Por eso, al advertir “lo que de Francia conocía, la mentira y la fealdad, huía de continente en continente, de océano en océano, sin que ninguna estrella le guiase a través de las variedades de la tierra”.

No es por tanto un peregrino, no todavía, sino un soldado errante que camina sin asiento fijo, sin camino trazado, sin destino al cual enderezar la marcha.

II

Nace un centurión

En ocasiones, la verdad sólo esplende en el filo de una espada

El Congo

En septiembre de 1906 llega Ernest al Congo, a las órdenes del Comandante Lenfant, “el mejor jefe que se pueda tener en la marcha”.

Ebrio de espacio, anhela recorrer el país en búsqueda de bélicas aventuras. No tiene descanso en sus viajes junto a Lenfant, que es tan aventurero como él. Explora, se adentra, registra, inspecciona todo con curiosidad y deleite. África le prodiga algo nuevo, un espacio que se abre ante él -paradojalmente inhóspito y acogedor, mortal y redentor- e incrementa las posibilidades de sondear las profundidades interiores. Ejercicio doloroso sí, pero al que le ve prontos frutos.

La tierra -dice bellamente- por su parte no sirve, visiblemente, sino de soporte a este cielo, y por ese mismo papel de esclava que asume, ensancha el corazón del viajero y lleva su ánimo a la contemplación silenciosa.

Ernest busca el vasto silencio del África. Su espíritu convulsionado anhela el reposo, salirse de la náusea de la blasfemia y la mentira, someter el alma inquieta a la serenidad de la obediencia. Pero la obediencia, ¿a quién? Todavía no lo sabe. Por ahora, sólo aspira a la vida nueva que sigue al asentimiento del llamado de las armas.

¡Vita nouva! ¡Vita nouva! Vida aérea y saltarina, como salta el saltamontes sobre la corteza del globo -combates, mandobles, una acción violenta rompiendo la rigidez de la envoltura corporal, un espíritu flexible en un cuerpo ágil-, tardes de batalla, los musulmanes perseguidos hasta sus guaridas, el odio; y después (…) largas meditaciones, con la frente entre las manos, sobre las causas y el efecto.

En esos primeros tiempos en campaña un feliz y libre Ernest, novato soldado raso, disfruta las misiones por el interior del país y el contacto con los nativos (“¿No son acaso los días más hermosos de mi vida los que estoy viviendo…?”).

Surge en él una particular estima por su jefe, que se mantendrá hasta el fin de sus días y ciertamente llama a atención, por lo sugerente, cómo le caracteriza al escribirle a su madre:

Es un hombre que mantiene durante el camino una jovialidad constante, un humor parejo y un carácter afable: un verdadero padre de familia, pero con un vuelo, con una pizca de poesía latente que le da un encanto inapreciable”.

Meditaciones sobre la vida militar

Ernest anhela el combate. “Estoy hecho para la guerra y la deseo como un pintor desea pintar”, dice con cierta afectación. Le fascina la prueba viril, la superación del miedo, la posibilidad del testimonio heroico. Desea formar parte de la “misteriosa comunión de la sangre vertida”.

Quiere forjarse en el servicio a los otros, a la patria, en el cultivo de las virtudes que son exigibles para todo hombre de guerra: “el valor, la alegría, el espíritu de iniciativa y el honor”.

Su anhelo de peripecias bélicas tiene además otro componente: es un modo más de alejarse definitivamente del Ernest de otros tiempos en los que aspiraba a una vida intelectual desprovista -hoy lo sabe- de un vínculo auténtico con lo real. Si aquél hubiese sido su derrotero, hoy estaría en París, o en Ginebra, como tantos de sus contemporáneos, ajenos a la vida auténtica, la vida en todo el esplendor de su dramática y maravillosa realidad.

Ernest no es un necio. Sabe que hay algo más en ese oficio suyo de mandar y obedecer. Sabe que es preciso elegir y que no alcanza con abandonarse al cómodo expediente de la verticalidad del mando. En lo que a su metier respecta, reconoce sólo dos opciones: o rechazar la autoridad y el ejército -que es su fundamento- o aceptar toda la autoridad: la humana o la divina.

En el sistema del orden hay el sacerdote y el soldado. En el sistema del desorden ni hay sacerdote ni hay soldado (…) Es preciso estar con los que se rebelan o contra ellos. Pero, ¿qué hacer si el objeto de la fidelidad resulta inaprehensible y el espíritu permanece impotente? .

De a poco Ernest comprende la trascendencia de la institución de la que forma parte. Comienza por reconocer a la milicia como el ámbito del orden, pero también como esfera de certezas. Al observar una sencilla fortaleza enclavada en el desierto, Ernest concluye la sustantiva relación entre el orden y la verdad.

La planta cuadrangular, la unidad en la materia -muros y techos iguales-, el sistema métrico, todo indica el orden, la medida en la fuerza. La regla armoniosa. Todos los que en su construcción intervinieron, todos eran soldados. Pero estos constructores improvisados han realizado una obra henchida de una singular significación. La morada que se han dado a sí mismos es en cierto modo la morada de lo absoluto.

Él sabe que el espíritu militar no está sujeto a lo geométrico y cuantofrénico -que todo lo mide, pesa y calcula- sino al afán de concreción del camino trazado, al orden que el soldado se impone en el cumplimiento del deber. Es aquello que Chesterton dice a través de Syme, el poeta de Saffron Park: “lo raro, lo extraño, es llegar a la meta; lo vulgar, lo obvio, es no llegar. El militar cumple con su misión menos por ánimo de obediencia que por fidelidad al orden, por amor a lo ordenado.

Ernest -que viene del caos y la rebeldía- necesita este orden como el alimento de cada día. Está por ello orgulloso de su condición de soldado. En ese sentido, como en otros, se verifica el contraste con el pensamiento de Alfred de Vigny, cuyo Servidumbre y grandeza militar ha sido tan sobreestimado a la hora de estudiar la vida militar.

La mochila del teniente Psichari, que trae siempre tres libros (los Sermones de Bossuet, los Pensamientos de Pascal y el Reglamento para la artillería de Campaña) no incluye a Servidumbre, al que objeta con cierto desdén. Porque es mucho lo que le distancia de su predecesor. En éste la vida militar es limitación sin sentido, en aquél se torna vocación al modo del sacerdote. La propia esencia de lo militar los separa irremediablemente. Mientras de Vigny dice que “es triste que todo se modifique entre nosotros y que el ejército sea lo único inmóvil”, Psichari reconoce al ejercito como “la antigua institución que nos ata al pasado, siempre parecida e idéntica a sí misma y cuya belleza reside en su inmutabilidad”.

Es cierto que, en esta época, en los albores de su vocación militar, Ernest le adjudica al ejército un rol supletorio al de la Iglesia. No ve, no puede ver todavía, que una y otra institución, tan lejos pero tan cerca, se complementan. Para él, el ejército allí “plantado, nada moderno, con el papel, la misión superior de vanguardia que tenía antes la Iglesia y que ésta ya no puede tener…”.

Por esa época, antes de comprender la íntima relación entre la espada y la Cruz, Ernest comparte con Péguy la idea de que “el ejército es la única realidad que el mundo moderno no había podido envilecer, porque ella no pertenece al mundo”.

Ernest no es un mero “soldado profesional”. Aspira a mucho más, y de ahí su búsqueda constante, en la que permanece y no ceja. No le es suficiente conocer los rudimentos de su oficio, ni le desvelan los ascensos ni los premios. Ni siquiera le conmueven en demasía las medallas que obtiene en el cumplimiento estricto de su deber, en el campo de batalla, con la vida puesta en riesgo. No. Busca nuestro héroe algo más. Se cuestiona a sí mismo. Procura salirse de los lindes de la mera observancia militar y se proyecta hacia otras preocupaciones, hacia nuevos interrogantes:

¿Por qué, si es un fiel soldado, -se pregunta Maxencio- ha consentido tantos abandonos y se ha hecho culpable de tantas negaciones? ¿Por qué, si detesta el progreso, rechaza a Roma, que es la piedra de toda fidelidad? Y si contempla con amor la espada inmutable, ¿por qué aparta sus ojos de la inmutable Cruz?

En la soledad de los campamentos, luego del agobio del día militar, “con la cabeza entre las manos”, Ernest medita sobre las virtudes ínsitas en su vocación y su vinculación con la pietas patriótica y religiosa. No teme al prurito del mero activismo ni a la supuesta contradicción entre el soldado y el contemplativo.

Se asemeja en tal sentido a la reflexión de Junger, el literato héroe que combatió toda la Gran Guerra, respecto del recogimiento en el campo de batalla: “En estos páramos -dice el teniente Sturm, su alter ego- los de la vida contemplativa están más a gusto. (…) Pues también puede considerar uno los acontecimientos con los ojos de la Edad Media, y entonces tendrá el fragor de las armas en los castillos y la soledad del monasterio, será al mismo tiempo monje y guerrero”.

Es por eso que Ernest no vacila en compartir el rebalse de sus contemplaciones escribiendo sus primeras novelas. En efecto, en esos días congoleños nacen sus Carnets de route y Terres de soleil et de sommeil, que constituyen una serie de impresiones sobre su viaje. Se atisban allí, en esos cuadernos de soldado nuevo y poeta antiguo, las preocupaciones metafísicas que van a caracterizar al resto de sus obras. Es ésta una contradicción sólo aparente entre la vida militar, pletórica de urgencias concretas y resoluciones inmediatas, y la contemplación de quien filosofa sobre sí mismo y el Cosmos. “Nada más acorde en este mundo que el espíritu religioso y el espíritu militar”, dice José de Maistre, a quien Psichari leyó asiduamente en sus Veladas de San Petersburgo.

Ernest comienza a serenarse, a dejar reposar su espíritu. En esas jornadas -en las que recorre el Congo en marcha a pie, navega el Alto Longone en piraguas o cabalga la sabana, sus pensamientos se dirigen, con renovado entusiasmo, hacia su Patria.

Francia. La política y la República

La Francia que “había muerto para él”, va develándose en su auténtico contorno, en la intimidad de su forma. Poco a poco, en el contraste con los moros y su religión herética, advierte la inmensidad del legado del cual es ahora representante.

El develamiento de Francia trae a los ojos de Ernest nuevas perspectivas y descubrimientos. Es cierto que por su condición militar - “la materia política está legítimamente vedada a los oficiales”- y sus empeños espirituales presta poca atención a los diarios aconteceres políticos.

No obstante, le llegan noticias y pensamientos a través de las grandes inteligencias del momento. Por supuesto, Péguy le mantiene al tanto a través de los Cahiers y su constante flujo de cartas. Pero también mantiene correspondencia con Maurice Barrés, que le contagia su ánimo nacionalista y que siente por Ernest una gran estima: en 1912 le dedica su libro de sobre El Greco y Toledo con una frase que emociona al joven oficial: “a Ernest Psichari, teniente de artillería colonial y coronel de las letras francesas”.

Pero la comprensión cabal de la política francesa la obtiene Ernest con su aproximación, acotada pero entusiasta, a Action Française.

Es usted el único hombre de nuestros días, -le escribe a Maurras en 1913- el único que haya construido una doctrina política realmente coherente, realmente grande; el único que haya aprendido la política, no el cotorreos y asambleas, sino en Aristóteles y Santo Tomás….

Como señala Molnar, “en una Francia todavía monárquica de corazón, Maurras no tenía gran dificultad en encontrar apoyos para la restauración. Desde el caso Dreyffus hasta la derrota de 1940, medio siglo, Maurras fue el indiscutible modelo de los oficiales del Ejército, del clero, de las señoras elegantes, de las clases burguesas e incluso de algunos patriotas izquierdistas que encontraban su ‘república’ no suficientemente militante”. Y, justamente el problema para Maurras y sus contemporáneos es encontrarse con una República a la que han crecido admirando y ahora les resulta extraña, intrusa, hostil.

El crimen de la República -escribe Ernest en carta a otro ex republicano, Henri Massis- es haber desorganizado la enseñanza y el ejército, las dos fuerzas de una nación; o más bien, haber querido rebajar el espíritu militar y el espíritu universitario, considerados ambos como antidemocráticos. No hay régimen más intolerante que la República, tal vez porque no hay nada más inestable. Todo lo que es de orden espiritual ha sido perseguido: el sacerdote, el soldado, el sabio. Y ese crimen ha sido querido, premeditado.

Ernest, con la objetividad que otorga la lejanía, advierte ahora las facultades disolventes de la República y su manía destructiva de todo orden natural. Aquél jovencito que otrora blasonaba de revolucionario se ha convertido en un hombre que detesta la irreverencia, la insurrección, la perturbación revolucionaria. Coincide en tal sentido con Chesterton en aquella pregunta esencial: “¿Qué hay de poético en una revuelta? Del mismo modo podría decirse que es poético estar mareado. Estar enfermo es una revuelta. En términos abstractos, rebelarse es como tener el estómago revuelto. No es más que un vomito”.

No se trata de plantear un imposible retorno al Ancien Regime, no. Pero, ¿no estaban acaso en esa época garantizadas, aunque atontadas, las virtudes que Ernest anhela?

Ahora todos ellos, los que alejados de los bienpensantes finalmente piensan bien, comprenden que los tiempos modernos son “el reino inexpiable del dinero”, como ha dicho Péguy. Y Maurras en su lucha contra la III República y sus adláteres - el Estado, el Dinero y la Opinión- es el hombre en quien confiar la empresa urgente de la restauración.

Ahora, esa pléyade de la que forma parte Ernest, que contiene lo mejor de su patria, comprende que la salvación de Francia depende de la restauración de la Francia antigua y sus pilares esenciales: la Iglesia, la monarquía, el ejército.

A propósito, es claro lo que dice nuestro Anzoátegui: “la Francia de hoy debe ser rescatada de la Francia de ayer. Lo proclamó ya Psichari convocando a somatén: ‘Luchemos contra nuestros padres al lado de nuestros antepasados’”.

Desde el silencio africano, entre bélicas jornadas y expediciones hacia la desértica lontananza, con el sólo contacto de los musulmanes, Ernest comprende por primera vez a su patria. Al fin se siente orgulloso de Francia y de ser francés. Está feliz en ese reencuentro. Pero entiende que tiene que luchar contra su padre, contra esa generación que ha corrompido a su patria pues “una, dos generaciones pueden olvidar la ley, y hacerse culpables de todos los abandonos, de todas las ingratitudes. Pero es preciso que, en la hora señalada, la cadena sea rehecha, y que la lamparilla vacilante brille de nuevo en la casa”.

Ha llegado la “hora señalada”, en la que es preciso emanciparse del pretérito infausto y contribuir en la restauración del hogar.

La “emancipación del pretérito”. El tránsito del centurión pagano al cristiano

Ernest siente cómo se ensanchan su espíritu y su inteligencia. África le prodiga el acceso a la belleza y al silencio. Accede aquí a la visión de su auténtica patria y también a una oración que sus labios aún no pronuncian pero que está en ciernes, ascendiendo desde los intersticios de su corazón. Su mirada se ha vuelto más clara. Ha transitado de la miopía causada por la ideología al esfuerzo por leer dentro de las cosas. Los hombres, la familia, la patria, la fe, la Iglesia, todo se le muestra ahora con mayor refulgencia. Ha llegado para nuestro héroe la hora de liberarse, de desatarse, de quitarse las viejas y carcomidas ataduras que lo sujetan al hombre según la carne: “Maxencio, silencioso, no sentía en su interior sino una inmensa emancipación de lo pretérito”.

Pero esta emancipación, menester es aclararlo, no es el grito descastado del revolucionario que deprecia toda creencia antigua. Por el contrario, Ernest se emancipa con el anhelo restaurador de quien se sabe objeto y sujeto de la transmisión de una tradición pretérita y permanente.

Los soldados no son hombres de progreso, -dice Ernest- su corazón no lo cambian ni los príncipes ni las ideas. No es el progreso lo difícil. Lo difícil, por el contrario, es seguir siendo uno mismo, como la roca que ningún huracán sacude.

En Ernest esta “emancipación de lo pretérito” conlleva la liberación, gradual y constante, de los despojos de su alma pagana: “¡Bendita esta definitiva emancipación mía de los hombres entregados a la mentira y a la iniquidad!”. Porque el alma, luego de conocido Cristo, no puede ser pagana: es cristiana y, si no, anticristiana.

El último día de 1906, mientras continúa de comisión en el Alto Logone, afluente del Congo, el Comandante Lenfant le nombra sargento. El tiempo en el Congo ha servido para forjar al soldado que Ernest ha querido ser. Ha respondido a la voz de las armas, la voz poderosa de la disciplina, la obediencia, la abnegación.

Pero otra Voz se hace presente en su espíritu. Ernest cree que se trata de un monólogo suyo, un mero ensimismamiento. Pero pronto caerá en la cuenta de que esa Voz en su interior es la de la Verdad que habita en él.

A mediados de 1907, Lenfant lo propone como aspirante a la Escuela de Artillería de Versalles. Regresa entonces a Francia, que ya es otra Francia para él, y durante dos años cursa sus estudios militares. En 1909 egresa como subteniente en 1909. Es ya un oficial del Ejército francés. Y también es, aunque todavía no lo comprende cabalmente, un centurión cristiano.

III

Domine non sum dignus…

El centurión cristiano

África, otra vez

En diciembre de 1909 el subteniente Psichari regresa a África, esta vez a Mauritania, “la tierra de los soldados, donde las armas siguen siendo veneradas”. Forma parte de un regimiento de artillería destinado a la región del Adrar, en pleno Sahara.

En esta ocasión su mochila trae un libro nuevo, regalo de Maritain: La dolorosa Pasión de nuestro Señor Jesucristo de Anna Catherina Emmerich.

África le brinda a Ernest la posibilidad del silencio. Porque él ha venido escapando del ruido moderno, ese “ruido que nos llama sin cesar a la superficie de nosotros mismos”, como dice Thibon. El hombre moderno le teme al silencio, que implica el retorno del alma a sí misma y es el inicio, casi diríamos la causa eficiente, del itinerario a Dios.

Por eso, Ernest busca el silencio, “ese poco de cielo que desciende hacia el hombre”. Y ese es, sin que él aún termine de comprenderlo, su primer paso hacia la conversión.

En África -dice Maxencio- la regla es el silencio. Como el monje en su claustro, guardas silencio el desierto envuelto en su blanca cogulla. Maxencio se pliega sin esfuerzo a la estricta observancia; oye piadosamente caer las horas en la eternidad que las encuadra y muere para el mundo que le ha defraudado.

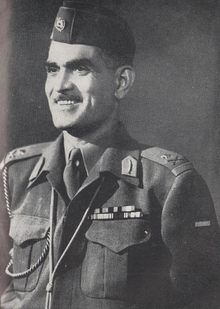

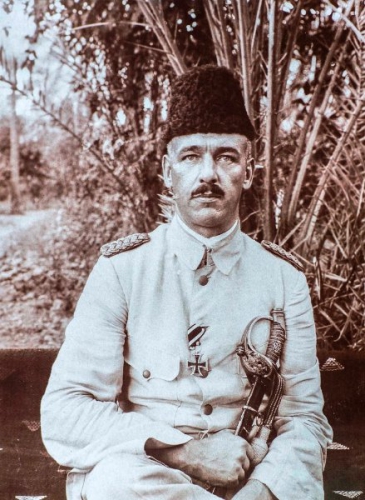

En esos días las tribus beduinas amenazan las rutas entre Marruecos y el África Occidental Francesa y se ha designado al Coronel Henri Gouraud como Comisario del Gobierno General de Mauritania para combatirlas. Gouraud es una leyenda del Ejército francés.

Pero Ernest no está muy convencido con su nuevo jefe, el Coronel Patey, quien comanda el regimiento de meharistas: “un hombre frío, siempre muy atento, pero muy duro (…) es el tipo de oficial que se ha paseado por todos los Estados Mayores, del género Escuela de Guerra, o si se puede decir, del género cordones”.

Poco después conoce al Comandante Frérejean, quien le causa gran admiración por sus condiciones militares y la leyenda que le rodea: “verdadero jefe de banda, especie de condotiero africano, es ilustre en Mauritania, donde, a lo que creo, no hay moro que no lo conozca. Él fue quien, en 1905, mató a Bakar, rey de Dovich, nuestro antiguo enemigo (…) No es, por cierto, un intelectual, pero sí un valiente y buen soldado”.

A fines de 1909, a instancias de Frérejean, a quien le ha caído en gracia, se convierte en oficial meharista. Pronto se ve al mando de uno de los goums de camelleros del Adrar y se dispone “a nomadizar durante algunos meses al azar de los pastos”. Es el súmmum de la vida errante. Tiene unos 50 hombres bajo su mando, incluyendo algunos “guerrilleros moros”: “Con este pequeño goum soy el más feliz y el más libre de los hombres…

Es ahora un jefe, un conductor de hombres. Conoce a sus hombres y ellos a él pues “la vida los ha enlazado entre sí y juntos forman un pequeño sistema completo, un sistema de gravitación moral, que se mueve a través de la inmensidad sin límites, combatido en todos los frentes por el huracán de las arenas”.

Pero Ernest no es sólo el jefe de una sección camellera perdida en el Sahara. Es el centurión de todas las épocas, el comandante intemporal “semejante a aquellos oficiales humildes de las cohortes romanas que de tarde en tarde aparecen en el Evangelio para que la preferencia de Dios quede manifiesta”.

Es cierto que las circunstancias le han llevado a optar por el arma de artillería aunque él se siente realmente a gusto entre los infantes y caballeros, a los que considera arquetipos del soldado. Son los hombres como Lenfant, Gouraud, Frérejean o Dubois -o un joven infante de marina que le asiste en sus aventuras y los alegres combates contra los saharauis- quienes le resultan genuinos guerreros y no esos “politécnicos de la artillería, sabihondos de lentes y cráneo pelado”. Quiere seguir siendo meharista, oficial camellero, que es el símbolo señero del oficial colonial africano, para seguir rindiendo sus servicios a esa Francia que cada vez se le aparece más clara y a la que comienza a amar con fervor para él desconocido.

El auténtico servicio a Francia: el soldado de la Cristiandad

Ernest, que vive por esos días “henchido de serenas armonías”, cumple sus deberes militares con entusiasmo.

Le interesan especialmente los moros, “esta noble y vetusta raza que se remonta al Oriente místico”, compuesta por hombres que son al mismo tiempo, “unos pillastres, viven de las guerras y de las rapiñas, son orgullosos como mendigos, ardientes en la acción, bravos y astutos”. Si alguna vez, al inicio de su periplo africano, vio con cierta admiración al musulmán, ahora comprende la herejía en la que está inmerso y la hondura de su enemistad con los cristianos, a los que despectivamente llama “nazarenos”.

No sin cierta paradoja, Ernest se acerca a la Francia auténtica, es decir la Francia cristiana, a través del contacto con estas tribus. Adquiere la certeza de su pertenencia a la tradición de la Cristiandad a través de la oposición entre el la Media Luna y la Cruz. Son los moros lo que “le han hecho entrever la Francia oculta que él desconocía y en sus labios han sustituido la filial acción de gracias a la infame negación”. Comprende que “es el enviado de un pueblo que sabe muy bien lo que vale la sangre de sus mártires”. Ahora, ante el moro, vuelve a ser “un franco con la certidumbre de su raza”. Y el orgullo que ahora siente ante el musulmán “¿qué podría ser sino un orgullo católico?”.

Porque, “¡dónde está Francia sino en Reims (…) en la pascual alegría de Chartres y en la nave protectora en la cual dicen que se complace la Reina de los Cielos, y también en aquellos campanarios campesinos, únicos testigos de la inmensa sucesión de generaciones!”.

Por esos días nace su tercer libro, L´Appel des Armes, en el que cifra renovadas esperanzas ya no sólo literarias sino espirituales. Se trata de una meditación sobre la vida de la milicia pero también una meditación cristiana, o tal vez protocristiana. Lo dedica a su “buen maestro”, a “aquél cuyo espíritu me acompañaba en las soledades de África, a ese otro solitario, alma de Francia hoy, y cuya obra ha vencido por el amor a nuestra juventud, a nuestro maestro, Charles Péguy”.

En L’Appel, Ernest señala ya la esencial ligazón entre la patria francesa y la Cristiandad de la que ha sido primogénita. Vinculación esta que se simboliza en la unión entre la espada y la Cruz que son “las figuras de los dos dogmas y las imágenes de los dos sistemas. Metafísicas diferentes, jamás aliadas, jamás coaligadas contra un enemigo común (…) y sin embargo qué maridaje el de los dos signos en el cielo iluminado y cómo los percibe tan juntos el uno del otro, apareciendo separados, y aureolados con luces sobrenaturales! (…) es que todos los místicos tienen el mismo sello, y esta señal es la persecución de una alta pasión que nos lanza fuera de nosotros mismos, y nos obliga a llorar de amor.

Iglesia y Cristiandad, dice Psichari a través del centurión Maxencio, han de ser verdades absolutas que no pueden ser una leyenda, una mentira, una legitimación como dicen los adláteres de la revolución.

Que esta misma nave de Nuestra Señora sea para siempre arrasada si María no es verdaderamente Nuestra Señora y Nuestra verdadera Emperatriz. Perezca Francia y sean borrados para siempre de la Historia estos veinte siglos de cristiandad si esta Cristiandad es mentira.

El 21 de enero de 1912, al mando de su sección meharista Ernest entabla un duro combate con los saharauis y los persigue durante varios kilómetros a través de los pedruscos de las laderas del Adrar. El asalto, que resulta favorable a la tropa francesa, tiene un aditamento para Ernest pues ese día mata por primera vez a un hombre. Lo relata impersonalmente, como si hubiese sido realmente otro, en este caso su Maxencio, quien “ebrio de cólera se precipita, sable en mano, hacia adelante. Extiende el brazo y experimenta la sensación de que su arma se hunde en la grasa humana”.

Como todo soldado de ley no necesita alardear con sus proezas. Por ello, no ha quedado registro detallado de esa breve pero fiera batalla, salvo su descripción literaria, que nos aproxima a esa realidad:

Maxencio sabe lo que son estos combates africanos en los cuales las dos líneas enemigas se contemplan, frente a frente, y se lanzan formidables insultos en el medio de formidables ráfagas de fuego, con la alegría y el odio visibles en todos los rostros (…) y el jefe, con el uniforme desgarrado sobre el pecho desnudo, intenta dominar con su voz el fragoroso tumulto: en una palabra, el intenso color militar, todo el poder de la belleza épica.

Luego de este combate, por el que recibe la Croix de Guerre, reflexiona acerca de la muerte: “cuando llegué a rozar la muerte en África, me creía valiente, pero esa hermosa seguridad ha sucumbido, y hoy advierto que la vida me da mucho más miedo que la muerte”.

Pero no son los entreveros terrestres los que le quitan el sueño. Sabe que existe otro combate que él hace tiempo viene librando. Es ese “cuerpo a cuerpo del hombre consigo mismo en el azul del espacio interior”. Y Ernest empieza a comprender que no bastan sus solas fuerzas para obtener esa victoria.

El soldado combate y esta es la aplicación exterior -dice Paul Bourget, gran escritor católico que gozó de la amistad de nuestro héroe-. Pero lo que importa al auténtico paladín cristiano, más allá del perfeccionamiento en el arte militar, es el desarrolló en sí, “secretamente, hasta su máxima tensión, de determinadas virtudes; a través de su oficio, alimenta y enriquece su alma. Y esta es la labor interior.

Ernest es ya un hombre de 27 años acostumbrado a los combates interiores y exteriores. La Verdad comienza a hacérsele patente, bien que con algunas sombras aún. Sabe que la muerte que le espera no puede ser la muerte del incrédulo, del que ha perdido toda esperanza, la del mero desaparecer. De algún modo anhela ya la muerte martirial pues reconoce que no hay verdadera Cruzada sin la opción del Martirio. Y es que sin vocación, sin alma de mártir, no hay centurión auténtico. Es lo que enseña el P. Castellani: “San Pedro tenía espada y le cortó la oreja a Malco; pero después fue y negó a Cristo, a pesar de sus buenas intenciones, solamente porque, teniendo en efecto alma de Cruzado, no había en su alma preparación de mártir. Se había dormido durante la Oración”.

Pero el centurión Psichari ya no duerme pues va despertando de su larga pesadilla y está atento como un centinela, procurando escuchar por sobre las voces del mundo, la Voz en su interior.

La Búsqueda de la Verdad

En su segundo año en el Sahara, Ernest va sintiendo “crecer su capacidad interior y ensancharse el círculo de sus posibilidades espirituales”.

Lee mucho, como siempre, Pero ahora se sumerge en la lectura de los Evangelios, que ocupan muchas de sus meditaciones. Ya no los lee como antes, emulando el afán historicista de su abuelo, sino con nueva reverencia y un temor creciente que no acierta a comprender.

Harto de los libros que le envían viejos amigos, colmados de los sofismas acostumbrados, espera ansioso los Cahiers que puntualmente le envía su madre. Péguy le dedica uno con palabras que merecen ser transcriptas:

Tú que en una casa gloriosa por los trabajos de la paz has introducido la guerra y la antigua gloria guerrera. Latino, romano, francés, con todas esas sangres nos das una sangre francesa y un heroísmo a la francesa (…) tú que impones la hoz por la guerra, tú que haces la paz con las armas, tú que impones el orden por la fuerza de las armas.

Es justamente Péguy el íntimo vínculo personal que lo une a Francia. Su figura le fascina cada vez más y, por contraste, desprecia profundamente todo el pensamiento y la literatura del progresismo modernista. Comparte aquellos que ha dicho el mismo Péguy, “nada es tan peligroso como la falsa cultura. Y desgraciadamente es verdadero que casi toda la cultura universitaria es falsa cultura". En el mismo sentido, Psichari en carta a su “buen maestro” señala su “disgusto profundo hacia la fofa literatura actual”.

Admira a Péguy por sus escritos que posibilitan el “por el gozo indecible de encontrar por fin el sentido justo y afinado de nuestros clásicos (…) todo ello con una fuerza, una destreza incomparables: es de un clasicismo refinado, de la más rara y pura elegancia francesa. (Esta elegancia, término adulterado que puede parecer horrible si se aplica a la elegancia adulterada de un Lemaitre, término detestable cuando se aplica a France o a Renán…)”.

Es esta la primera vez que se permite expresar una crítica sobre el pensamiento de su abuelo, aunque más tarde lo hará con cierta insistencia. Alejarse de su abuelo, de sus ideas y su apostasía es parte de la tarea espiritual que tanto se exige. Alejarse de su figura implica salirse del “fango del mundo moderno” en el que ha vivido tanto tiempo atrapado.

Ernest quiere ser uno de quienes derriben ese entramado revolucionario, predispuestos a la destrucción de Francia, quiere derribar toda “esa escoria intelectual, esa cáfila de bárbaros, novelistas de adulterios, mundanos podridos, francmasones, radical-socialistas, que dan a nuestra época ese aspecto de confusión anárquica”.

Lo que su inteligencia requiere ahora son afirmaciones, luego de la duda metódica y el ánimo relativista en los que se ha alimentado tanto tiempo, pues anhela tan sólo “la alegría exultante de la certidumbre”.

Tentación y caída. Presencia de Nuestra Señora

Pero si su inteligencia ya ha aprehendido la distinción clara entre el error de la verdad, si su razón se va haciendo recta, es su voluntad la que aún se resiste. Se ha convertido sí, pero sigue siendo, como él mismo dice, un “católico sin fe”. Y si ese absurdo es posible es por su la precariedad de su conversión reciente. En realidad, se trata de la precariedad ínsita a todo hombre que, tentado, está siempre está al borde del pecado; la labilidad que nos lleva a hacer el mal que no queremos y eludir el bien que anhelamos.

Ernest es tentado. Y peca una y otra vez. Advierte como se inicia “la pendiente que conduce a la inevitable catástrofe, a aquella dimisión de sí mismo que ya le es conocida y cuyo resultado es que ninguna repugnancia ni rencor alguno vendrán a llenar el inmenso y negro abismo de la caída.

En El viaje nuestro héroe da cuenta de un hecho infausto que le hace retroceder en ese camino de conversión. Narra el abuso de una jovencita por parte de Maxencio quien “ante aquella forma inmóvil, ante aquella cosa que le pertenecía, sintió una inmensa compasión. Por un momento pensó en despedirla, avergonzado ante aquél pobre botín. Pero su alma no le obedecía ya….

Confesión triste y valiente la suya, pero también pedagógica, catequética. “Vigilad y orad”, dice Ernest pues, ¿qué es entrar en tentación, sino salirse de la fe?

Ernest sabe con Pascal, a quien lee desde adolescente, que “si uno no se conoce a sí mismo como un ser lleno de soberbia, de ambición, de concupiscencia, de debilidad, de miseria y de injusticia, se es bien ciego”. Pero, reconoce al mismo tiempo que esa visión de sí tiene remedio, tiene liberación a través de la fe. Su camino de conversión no tiene ya vuelta atrás.

Uno de los más significativos episodios de su acercamiento a la fe en aquellos días en el desierto es la recepción de una postal enviada por Maritain.

Es una sencilla tarjeta con la imagen de la Dolorosa de La Salette, con un breve mensaje de su amigo: “hemos rezado por ti en la cima de la santa montaña. Siento como si esta Virgen tan bella llorase por ti y por tu apartamiento. ¿No la escucharás?

Pero, según parece, ha sido “vana aquella salutación de la rosa al cardo” pues Maxencio deja sobre la arena la estampa de la Dolorosa, que vuela al viento…”. No obstante, más tarde Ernest reconocerá al amigo la importancia de aquél envío y su propio papel como intermediario para la recepción de la Gracia.

Al fin, Jesucristo

La conversión implica un retorno, recorrer en sentido inverso el camino realizado. Ernest ya casi ha finalizado ese “camino de vuelta, pero le queda aún un breve trecho. ¿Qué le falta para trasponer el umbral de lo Absoluto? ¿Por qué subsiste en él esa angustia misteriosa mezclada con la alegría de “haber conquistado el mundo”?

Es que persiste en él cierta inclinación a percibir la fe como una mera filiación, como un simple pertenecer, pero no como un estar definitivo. Le sucede todavía lo que señala el P. Clerissac -quien será su director espiritual- en su obra cumbre: “Ser Iglesia (¿cuántos saborean esta fórmula vibrante?), pertenecer a la Iglesia, para muchos no es más que estar inscritos, haber sido inscritos antes del uso de razón en una sociedad encargada de velar por las buenas costumbres”. Por momentos Ernest sigue pensando en la Iglesia de este modo. Lo que escribe en carta a Maritain es significativo: “De la religión espero todo, menos mi salvación”.

En sus últimos meses en Mauritania ha iniciado un libro que narra la historia de una conversión en el silencio de los desiertos de África. Se trata de El viaje del Centurión que terminará en Francia y que nunca verá publicado. Es un libro autobiográfico, como todos los suyos, aún cuando niegue que se trate del relato de su conversión pues le teme al hacer en “los detestables excesos de la psicología, en ese abuso de la observación interna, en esa verdadera complacencia de sí mismo que caracteriza a los escritores modernos”.

El viaje es sin dudas su obra maestra, aunque de género difícil de definir pues es tanto una novela como un diario espiritual, un relato de aventuras como la narración en tercera persona de los vaivenes psicológicos y morales del propio Psichari.

No obstante, a diferencia de sus libros anteriores, ésta es la obra de un converso. Es el libro de un hombre que no escribe lo que le viene al caletre por el afán de gloria literaria sino el de un cristiano que escribe para la mayor gloria de Dios.

Esa aprehensión del sentido cristiano de la literatura es lo que Ernest define en carta a Paul Bourget: “¡Ah, el de la pluma es un sacerdocio real, regale sacerdotium, pero también terrible y sería imposible ejercerlo dignamente si no se recurriera en todo momento a la Santísima Trinidad, nuestro único refugio!”.

Se trata, en definitiva, de transformar el propio trabajo “en una larga y silenciosa oración”.

Al momento de terminar El viaje, en agosto de 1913, Ernest ha traspuesto el umbral e ingresado en la Iglesia. Atrás quedaron las dilaciones y las dudas. Ahora le parece “imposible seguir mirando como extraño mucho tiempo más a este adorable pensamiento cristiano”.

Ha llegado el Gozo. Jesucristo se ha develado. La alegría del Señor lo invade. Ernest vive ahora lo que enseña el P. Clerissac: “En la noche de nuestras búsquedas filosóficas se nos enciende la Revelación de Cristo (…). La grandeza del Misterio nos aturde; y está tan lejos que su belleza se nos convierte un poco en aridez matemática. Pero de ahí viene toda vida.

Luego de tantas lides libradas en el desierto exterior y en la aridez de su propia alma nuestro centurión ha llegado a Jesucristo. Todo le parece ahora claro, diáfano y sencillo en su raigal hermosura. Tan elemental le resulta ahora la Verdad que le parece inconcebible la pertinacia con la que durante años la ha negado.

¡Pues qué, Señor! -exclama al fin Maxencio- ¿Es, en verdad, tan sencillo amaros?

IV

“La Mansión de todos mis anhelos”

Dichosas las espigas y los trigos segados

Charles Péguy

El ingreso a la Mansión. Bautismo solemne y confirmación.

Como quien cambia de piel, Ernest ha perdido los vestigios de su espíritu pagano. No ha sido una conversión paulina la suya. No hay rayo, ni caída del caballo, ni visión celeste. Es un tránsito arduo, una suerte de monólogo consigo mismo que, gradualmente, ha dado paso a un diálogo con Dios. Y es que, aquí sí se impone cierto relativismo, hay tantos caminos de conversión como hombres.

A Ernest ya no le atosiga la inquietud enfermiza de la incertidumbre. Su espíritu ya no sufre el desorden de no estar allí donde debe. Siente al fin que ha llegado a ser un hombre entero “y cuando, con su espada desnuda clavada en el suelo, jura sobre las cenizas de sus compañeros ser un buen servidor, es ya cristiano y participa ya en la gracia de la santa Iglesia”.

Ernest sabe que ha de alimentar esa certeza beatífica con la ayuda de la gracia y de los instrumentos que ésta pone a su alcance. Por eso es también significativa la presencia de algunas personas que le enseñan a andar el nuevo camino. Además de Maritain, es el P. Humbert Clerissac quien le acompaña en el traspaso del Umbral y el definitivo retorno al Redil. Maritain se lo presenta a fines de 1912 y Ernest vive el encuentro como obra de la Providencia, “para aproximarse más a Dios y para enseñarme todo lo que ignoraba hasta entonces”.

Vendrán entonces largas jornadas catequéticas, conversaciones y retiros espirituales. Poco a poco, el catecúmeno Ernest se prepara para el momento más importante de su vida.

Finalmente, el 1 de enero de 1913, el bautismo que propiciara la religiosa abuela, valido de toda validez, se realiza ahora con toda solemnidad. Poco después, tras una peregrinación a Chartres, la Primera Comunión y finalmente, el 9 de febrero de 1913, el Sacramento de la Confirmación de manos de Monseñor Gibier, Obispo de Orleáns. Narra Mons. Olgiati que, al finalizar la ceremonia Ernest exclamó: “¡Monseñor, me parece tener otra alma!”.

El inicio de la vida sacramental, la asiduidad de las lecturas espirituales, la dirección espiritual del P. Clerissac, todo converge en el alma de Ernest en beatífico torbellino: “Hay que ser santos -le escribe al dominico- no puedo menos que temblar cuando pienso en la enorme desproporción entre lo que merezco y lo que deseo”.

Va acercándose a la paz de espíritu que Santo Tomás llamó quies animi, es decir “esa calma que invade lo más íntimo y profundo del ser humano, una paz que es ‘sello’ y fruto de orden”. Es la tranquilidad en el orden que se desenvuelve naturalmente en la Iglesia, del mismo modo que en el hogar cuando éste es sano y fecundo.

Ernest ha vivido errabundo la mayor parte de su vida, sin poder asirse al orden que tanto ha ansiado. Por eso al entrar al Redil siente que vuelto al hogar. Lo explica bellamente: “Nosotros los desterrados sabemos mejor que nadie lo que es la Casa. A ella se dirigen todos nuestros pensamientos cuando vagamos por el desierto; es ella la que, bajo la carpa, desean nuestras tiernas añoranzas. En ella depositamos nuestra fe….

Comienza a comprender la Iglesia y la esencia de su misión salvadora en el mundo. Y adquiere conciencia cabal de que el mundo mundano, del que ha logrado desasirse, será de ahora en más su enemigo, del mismo modo que lo es de Cristo. Con el P. Clerissac cree que “si toda alma cristiana es un cántico, la Iglesia es el Cántico de los Cánticos, la patria del lirismo sagrado, el preludio de las sinfonías eternas”. Y razona también que la Iglesia es el freno de la injusticia, que en medio de los avances del demonio, del crimen y la iniquidad “se alza el Obispo, en pie sobre la piedra inconmovible, y con el sólo gesto de sus dedos levantados detiene el avance de la multitud aulladora y la invasión de la barbarie.

Ernest vive desbordado por la alegría de la fe, por el gozo que hace nuevas la hace nuevas todas las cosas en su vida, el júbilo de encontrarse al fin en Casa. Sólo una desazón le desgarra: la incomprensión de su familia respecto de su conversión.

Resulta tristemente paradojal que mientras él descubre al Padre Celestial, se distancie cada vez más de su padre terreno, de quien se aleja cada vez más.

Jean Psichari tiene un temperamento violento y cada vez más despótico lo que genera frecuentes encontronazos con Ernest que no le admite ya los egoísmos malsanos a los que los ha acostumbrado.

Pero todo se desbarranca cuando Jean, a principios de 1912, atenazado por la lujuria, se atreve a llevar al hogar familiar a una joven amante. Como es lógico Noemí, a pesar de que sigue amando a su esposo, no tolera la cohabitación escandalosa y los Psichari se divorcian. Mientras abandona a su esposa, y ante el escándalo social generado, Jean Psichari escribe una suerte de descargo en un mamotreto titulado Le crime du poete.

Ernest siente desgarrársele el corazón ante esta situación. No se acongoja como un burgués farisaico preocupado por el escándalete sino por la mella espiritual en su familia, por la dureza de corazón de su padre -cada vez más ofuscado en su ideología- por su madre abandonada y por sus hermanos, que no quieren vivir la fe.

A Ernest le pesa enormemente la incredulidad de los suyos. Como en el caso de Péguy, su familia no puede aceptar su conversión. Su madre, que no abandona su agnosticismo raigal y no comprende la conversión de su hijo. Y sufre también por sus hermanos: por Michel y Henriette, pero sobre todo por Corrie, su predilecta.

En marzo de 1913 viaja a Bélgica junto a su apenada madre. En el periplo, que incluye varias ciudades, conversa con ella como nunca antes. Quiere mostrarle la luz que acaba de descubrir. Y las conversaciones parecen dar frutos: “Creo que no hay que desesperar de ver volver un día al redil a esta alma de elección”.

Terciario dominico. Discernimiento sacerdotal

Ernest intenta recuperar el tiempo que considera perdido. En los momentos que le dejan sus deberes militares hace todo lo posible por insertarse en la vida de la Iglesia: ingresa en la Sociedad de San Vicente de Paul, concurre a retiros ignacianos, envía óbolos para la construcción de la Catedral de Dakar.

Pero el contacto primero con los dominicos -especialmente con el P. Clerissac pero también con los PP. Hebert y Augier- le predispone de manera especial hacia la Orden de Santo Domingo. No tarda en llegar la invitación para su ingreso en la Tercera Orden, lo que se formaliza el día 19 de octubre de 1913, en ceremonia presidida por el P. Clerissac.

Ahora Ernest está pensando en el siguiente paso: el discernimiento sacerdotal. Así se lo dice a su director espiritual, manifestando su especial interés en ingresar a la Orden de los Predicadores a quienes admira por los pilares en los que se sostienen: la oración, la comunidad, el estudio y la predicación compendiados en el lema: contemplata aliis tradere; contemplar y dar a los demás lo contemplado.

En bellos versos, Claudel afirma esa vocación:

Dentro del uniforme aún me encuentro a mí

mismo y estos galones ¿qué hacen en mi manga?

Necesito el capuchón sobre la nuca para

perderme en él, y el hábito profundo de lana blanca.

Sin embargo, Ernest piensa que esa vocación que ha de discernir está sujeta a no pocas dificultades interiores y exteriores. Entre esos escollos “una de las más grandes es la pena inmensa que mi decisión le ocasionaría a mi madre, y la obligación que tendría de vivir lejos de ella”.

Pero el principal obstáculo es el gran interrogante que aún no puede responder: ¿quiere Dios que sea sacerdote? La respuesta definitiva la dará la Providencia con el curso de los acontecimientos. Lo cierto es que su vocación cumplida, llevada a la cima de la entrega, fue la del centurión cristiano.

El soldado de Cristo: la guerra y el fin del peregrinaje

El 28 de julio de 1914, el Imperio austro húngaro apoyado por Alemania declara la guerra a Serbia y el sistema de alianzas se pone en marcha: Rusia, aliada de Serbia, declara la guerra a Austria-Hungría; y el 1 de agosto Alemania declara la guerra a Rusia y dos días más tarde a Francia. Al día siguiente, el ejército alemán abre el frente occidental invadiendo Bélgica y Luxemburgo, con un ataque a la ciudad de Lieja y obteniendo el control militar de regiones industriales importantes del este de Francia.

Ernest ha permanecido en el cuartel de Cherburgo a la espera de órdenes. Tiene ansiedad por presentar combate junto sus entusiastas muchachos, de los que está orgulloso: “Tengo a mi alrededor -le escribe a su madre- una pandilla de mocetones muy orgullosos de marchar contra el enemigo y muy decididos a portarse como bravos.

Ernest siente la felicidad de aquél que, limpia la conciencia, se dispone a entregarse en el cumplimiento de su deber. Es feliz de estar aquí con los suyos, con algunos de los cuales comparte la esencia de su misión: para él, combatir por Francia es combatir por la Fe: “¡Ay, qué hermosa sería Francia si fuera cristiana!”.

Siente la tranquilidad de estar donde el deber lo llama y no lejos, a salvo de la guerra, exiliado entre placeres mundanos y escribiendo libros malos, como tantos otros de su generación. Es lo que señala Ernest Junger al referirse a los literatos que miraron la guerra desde la comodidad de un club, en medio de las diatribas pseudoliterarias, ajenos al drama magnifico de la contienda.

Ellos han quedado desconectados, mientras en nosotros vibra el gran sentido de la vida (…) el último soldado alemán de uniforme gris o el último soldado francés de poblada barba que disparaba y recargaba en la batalla del Marne es más relevante para el mundo que todos los libros que puedan apilar esos literatos.

El 19 de julio, ante la inminencia de la guerra, parte con su regimiento, en el que comanda la 3° batería. En la marcha, “confiados y gozosos” los soldados entonan alegres marchas y canciones, mientras piensan en las madres, esposas y novias que dejan atrás.

Ernest marcha confiado en la victoria. No triunfará el mal, se dice. Su patria lo llama y él ha respondido con solicitud. Cree firmemente que seguir sirviendo a Francia es el deseo de Dios y sólo ambiciona “ser un soldado de Cristo, miles Christi”.

No le teme a la muerte, tampoco la anhela: "la muerte gloriosa del cristiano, pues ese día el cielo también se alegra. ¡Qué hermoso ha de ser eso, y qué dicha, la de pensar en ello desde ahora, maguer el peso terrible de nuestra miseria humana!”.

Las órdenes a su regimiento son lacónicas: contribuir a detener el avance de los alemanes, que han invadido Bélgica y prosiguen su marcha hacia Francia. La unidad se despliega entonces en las inmediaciones de un desfiladero que a Ernest le resulta familiar, pues lo ha visitado el anterior invierno, de viaje con su madre. El paraje se llama Saint Vicent de Rossignol y es allí donde el Sambre fluye en dos cristalinas vertientes que, internadas en el valle boscoso, parecen transitar hacia la eternidad.

Bibliografía

. - Cf. Diane ORGEOLET: “Évocation de Jean Psichari vivant”, en: Bulletin de l’Association Guillaume

Budé, n° 2. Juin, 1978, pp. 180-181.

.- Sobre Renan véase de Rubén CALDERÓN BOUCHET el estudio “Renan o la religiosidad” en su libro El espíritu del capitalismo, Buenos Aires, Nueva Hispanidad, 2008, pp. 317-343. Y un buen estudio introductorio en: Estanislao CANTERO: “Literatura, religión y política en la Francia del siglo XIX: Ernest Renan”, en: Verbo, n° 447-448, 2006, pp. 557-592.

.- Ernest PSICHARI: El viaje del Centurión, Buenos Aires, Difusión, 1941, pp.24-25. Resulta curioso que uno de los libros principales de Jean Psichari se haya titulado Mi viaje. Allí describe un periplo por tierra griega, con el que proclama el uso de la lengua griega moderna en detrimento de la tradicional. Como veremos, la opaca presencia del padre tiene peso propio en la vida, y la obra, de Ernest.

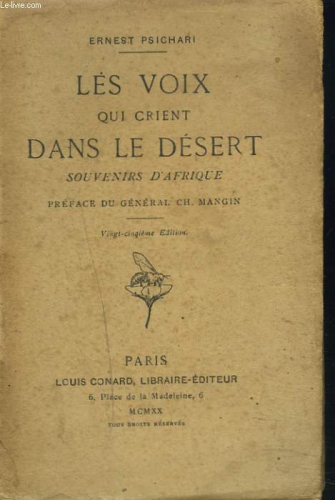

.- Rita TELLIER (SEJ): Les voix qui crient dans le desert. L’ evolution spirituelle d’ Ernest Psichari, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, 1962, p. 21. Este libro, nacido de una tesis de la Hna. Tellier y lamentablemente no traducido al castellano, constituye una excelente introducción a la vida espiritual de Ernesto Psichari.

.- Henriette PSICHARI: “Introducción” a: Ernesto PSICHARI: Cartas del Centurión, Buenos Aires, Sapientia, 1946, p. 7.

.- Ernest PSICHARI: “Carta a su padre”, 13 de junio de 1898, en: Cartas, pp. 23-24..

.- PSICHARI: El viaje, p. 25

.- Cf. TELLIER: Op. cit., p. 32.

.- Dice el P. Castellani respecto de estos hombres que han odiado a Dios: “Es, pues, cierto que hay hoy día un número creciente de hombres decididos a enseñar a sus hermanos que no hay Dios, que no hay otra vida, y que lo único por lo que se debe bregar, es para conseguir una sociedad próspera y feliz en este mundo. ‘El cielo se lo dejamos a los ángeles y a los gorriones’-blasfemaba Heine. Todo lo que impida fabricar un Edén en la tierra y un Rascacielos que efectivamente llegue hasta el cielo, debe ser combatido con la máxima fuerza y por todos los medios según estos hombres. Los que desde cualquier modo atajen o estorben la creación de esa Sociedad Terrena Perfecta y Feliz deben ser eliminados a cualquier costo. Todas las inmensas fuerzas del Dinero, la Política y la Técnica Moderna deben ser puestas al servicio de esta gran empresa de la Humanidad, que un gran político francés, Viviani, definió con el tropo bien apropiado de ‘apagar las estrellas’. Estos hombres no son solamente los herejes; ni tampoco son ellos todos los judíos y todos los herejes; aunque es cierto que a esa trenza de tres se pueden reducir aducir como a su origen todos los que hoy día están ocupados—ocupados ¡y con qué febril eficiencia a veces!— en ese trabajito de pura cepa demoníaca. Cf. Leonardo CASTELLANI: Seis ensayos y tres cartas, Buenos Aires, Dictio, 1968, p150.

.- Charles Péguy, describe esta educación ideologizada en párrafo esclarecedor: "todos mis compañeros se han quitado de encima, como yo, su catolicismo […]. Los trece o catorce siglos de cristianismo implantado entre mis antepasados, los once o doce años de enseñanza y a veces de educación católica sincera y fielmente recibida han pasado por mí sin dejar huella". Cit. por Gianni VALENTE: “Péguy en el umbral”, en: 30 Giorni, Roma, n° 1997, p. 19.

.- El General Marie - Georges Picquart, jefe de la Segunda Cartera (inteligencia militar) tuvo un rol preponderante en el Caso Dreyffus, en el bando progresista. Esa actuación le garantizó gloria administrativa y llegó a ser jefe del Estado Mayor. Fue muy amigo de Jean Psichari, quien le dedicó uno de sus libros. Auguste Scheurer-Kestner fue un industrial y político que, siendo senador, cumplió un papel importante a favor de Dreyfuss. La participación de Émile Zola en el Affaire con su famoso líbelo, J’accuse, es harto conocida.

.- PSICHARI: “Carta a su padre”, 13 de junio de 1898, en: Cartas, p. 25.

.- PSICHARI: “Carta a la señora Favre”, Septiembre de 1902, en: Cartas, p. 35.

.- TELLIER: Op. cit., p. 29.

.- Jacques MARITAIN: “La Revue universelle”, cit. por TELLIER: Op. Cit., p. 28.

.- Thomas MOLNAR: “La tentación pagana”, en: Verbo, n° 193-194, 19…, p.285.

.- Hilaire BELLOC: Sobrevivientes y recién llegados, Buenos Aires, Pórtico, 2004, p. 233. Vale ampliar aquí, aunque en apretada síntesis, la perspectiva de Belloc sobre la mentalidad moderna que “da por supuestos sin examen una cantidad de primeros principios como, por ejemplo, que hay un progreso regular de lo pero a lo mejor en los siglos de la experiencia humana, o que las oligarquías parlamentarias son democráticas, o que la democracia es obviamente la mejor forma de gobierno humano, o que el objetivo del esfuerzo humano es el dinero y que la palabra ‘éxito’ significa acumulación de la riqueza”, cf. BELLOC: Op, cit., p. 234.

.- Cf. Stephen SCHOLOESSER: Jazz age Catholicism. Mystic Modernism in Postwar Paris, 1919- 1933, University of Toronto press, Toronto, 2005, p.74.

.- Hacia el final de sus días Ernest, ya converso, mantendrá contacto con Jeanne, también abrazada a la Fe. Vid. Infra cap. IV.

.- PSICHARI: El viaje, p.25

.- El 5 de enero de 1900 sale el primer número de sus “Cuadernos de la Quincena” (“Cahiers de la Quinzaine”). Péguy lo editará por trece años, cada dos semanas (¡228 textos en los primeros diez años!). La sede es un taller en Rue de la Sorbonne, en dos piezas chicas. Daniel Rops dirá de los Cuadernos: “Los Cahiers fueron una empresa heroica”. Péguy escribe, barre, empaqueta, recibe, escucha, discute y corrige los textos. La revista tiene más de 80 colaboradores de los cuales entre los más famosos se encuentra a Jaures, Bergson, Anatole France, Zola, Rolland, Jacques Maritain. No pocos de ellos negarán más tarde al Péguy cristiano de los últimos años.

.- Eugenio D’ORS: Diccionario filosófico portátil, Madrid, Criterio Libros, 1999, pp.136-137.

.- PSICHARI: “Carta a la señora de Favre”, agosto de 1902, en: Cartas, p. 31.

.- PSICHARI: “Carta a la señora de Favre”, 26 de enero de 1903, en: Cartas, pp. 35-36.

.- PSICHARI: El viaje, p. 46.

.- PSICHARI: “Carta a su padre”, 2 de febrero de 1904, en: Cartas, pp.40-41.

.- PSICHARI: El viaje, p. 31.

.- Ídem, p. 25. En 1906 Jacques Maritain, ya casado con Raissa Oumansoff, ingresa en la Iglesia de Cristo con el padrinazgo de León Bloy. Su conversión causa estupor en su familia -sobre todo en Genevieve Favre- y cierta desorientación en Ernest que, sin embargo, ya intuía la decisión de su amigo. Todavía en 1911, cuando él mismo marchaba a paso firme hacia la Nave, piensa la conversión de Maritain como una suerte de distorsión intelectualista.

.- PSICHARI: “Carta a su madre”, 10 de septiembre de 1906, en: Cartas, p.63.

.- PSICHARI: El viaje, p. 90.

.- PSICHARI: El viaje, p. 31.