Editor’s Note:

This is the transcript by V. S. of Richard Spencer’s Vanguard Podcast interview of Jonathan Bowden about feminism. You can listen to the podcast here [2].

Richard Spencer: Hello, everyone! Today it’s great to welcome back to the program our friend and contributor Jonathan Bowden. Jonathan, thanks for being back with us! How are things over on your side of the Atlantic?

Jonathan Bowden: Yes, a bit frigid, a bit cold these days, but probably nothing to what it’s like on your side. But otherwise well.

RS: Excellent. Today we are going to talk about another big and important issue for our movement, and that is feminism. It’s obviously an issue of major importance for the world as well.

Jonathan, what makes feminism so complicated and interesting is that it’s had all of these various waves, as they call them, and they’ve often put forward contradictory philosophies and objectives. But maybe that’s what’s made feminism so long lasting and powerful in a way.

To get the conversation started, just talk about that initial impulse towards feminism, where it was coming from, where do you think it cropped up first. What’s sort of the first first-wave, so to speak, of feminism? Do you think this was with women’s suffrage or was it with one of the many liberal revolutions that occurred in Europe over the course of the 19th century? Where do you think that original urge came from?

JB: That’s a complicated and quite a difficult one. Textually, it goes back to Mary Wollstonecraft’s The Rights of Women as against Tom Paine’s Rights of Man produced in a similar timeframe at the beginning of the 19th century and sort of coming out of the later end of the 18th century. She was part of a radical ferment of opinion around William Godwin and his extended family into which she was intermarried.

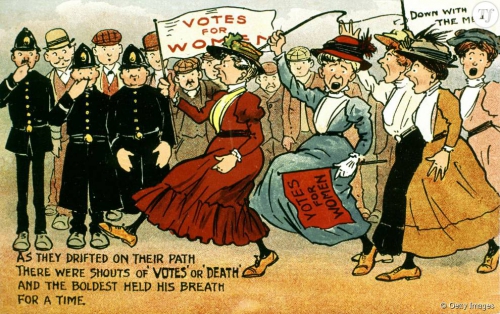

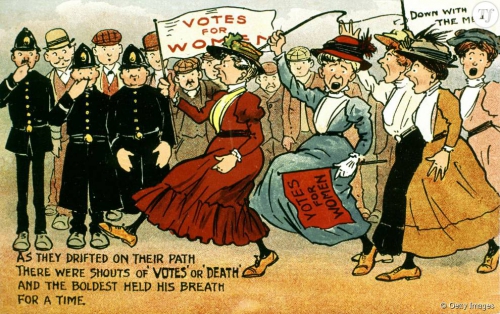

But the political drift of feminism in its first wave that’s discernible has to be in and around the Great War, 1914–1918 in Europe, and just after where you have a militant movement for women’s suffrage concentrating on the vote but often extending out into other areas and you have that split between two wings. Those who would pursue purely non-violent means, who’ve been largely forgotten by history, the suffragists, and those who were prepared to use direct action, and indeed even violence, to get their way, the suffragettes, who are the ones who history remembers. They are the ones who were force-fed in prison. They are the ones who chained themselves to railings. They are the ones who assaulted police officers. They are the ones who threw themselves in front of derby winners, and some were trampled to death on news reels of the time to great and extended excitement and social convulsion.

So, that was the first wave, which then fed into the swinging 1920s as Europe and the West relaxed into a hedonistic decade after the slaughter of the Great War and prior to the coming depression of the ’30s.

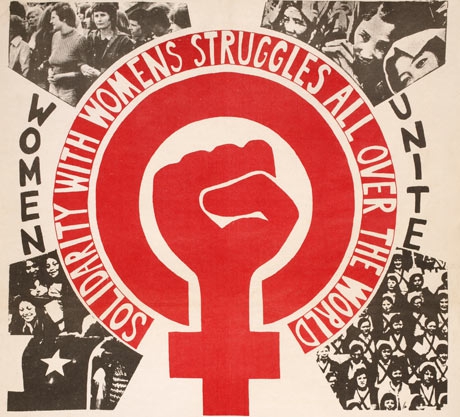

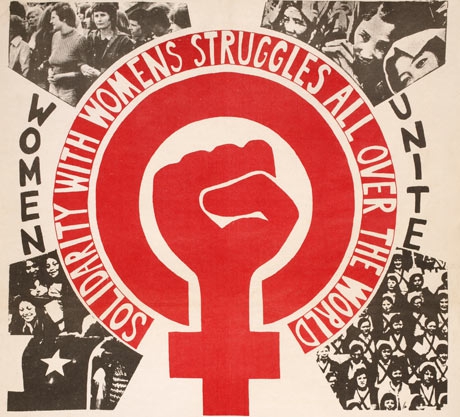

Second-wave feminism, as it is called, is co-relative to the ’60s and has a whole new generation, skipping out several generations, in actual fact, between the first and the second waves. The second wave is notorious for its theorists and its polemics and its going outside the box of what is understood to be political and looking at all areas of life often in a rather caustic and adversarial way.

Culturally, the second wave, you could argue, had far more impact than the first wave, but it wouldn’t have amounted to anything without the first wave, and the first wave did genuinely convulse the society because nothing divided opinion like the issue of if women should get the vote, because it was axiomatic of all sort of other matters in the society. By giving them the vote, it indicated that women could do almost all jobs that men could do up to a point, and it opened the professions to them; it opened the universities to them; it opened higher educational institutions to them; it opened the world of politics and political representation to them, not just voting.

And so, in a way, it changed the world, and that’s why the dynamite of the vote was used.

RS: What do you think was the reigning philosophy of the early suffragists and suffragettes? Was it a liberal one? Do you think it could be connected with some of the early social democratic and Marxian movements? What do you think about that?

JB: Well, I think the honest answer is yes and no. The truth is that female politics resembles male politics pretty closely and that there’s a range of opinion Right, Left, and center. What surprised many sociologists when women got the vote, particularly bourgeois women, is they voted pretty much along the lines that men did and were perceived to have the same social and economic interests that men did.

There have been times when the gender gap has been one way and then the other. For example, today in the Western world, which is quite clearly Anglo-Saxon — the Anglophone world — there seems to be a marked preference for center-Left parties amongst women as against center-Right parties amongst men, and that drift and gap is quite discernible.

But there have been times when women have been much more conservative than men and on certain issues women remain a lot more conservative than men. On law and order issues in the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s, women often had much more conservative attitudes than men.

So, it’s debatable in a way. Certainly, a large number of bourgeois supporters of female suffrage just wanted the vote as a coping stone, as a sort of seal of approval for their admission into social life and once that happened they reverted to essentially a conservative tradition. Some of the first women to be elected, of course, into parliaments were on the conservative side, because it was inevitable that women from a very bourgeois background would be the best educated women and would be the women who, in some ways, wanted to protect the status quo, and all that the suffrage did for them was allow them to do so. In the past, they would have done that through men, really, then they had a chance to do it on their own behalf.

It is true that the vanguard movements were associated, for the most part, with liberal and with social democratic causes and with the culture of the Left, generally speaking. That’s because it was seen to be an out-of-left-field movement. It was seen to be a movement for radical change and it inevitably adhered to the Left rather than the Right.

RS: Just to add onto what you were talking about earlier. A good friend of mine often will tell a powerful anecdote about female voting, and if you’ll forgive me, I’m forgetting some of the details, but as with details it’s the essence of it that matters.

There was a revolutionary parliament in France, and they were actually bringing up the question of whether women should vote, and actually the people who most vigorously opposed it were the far Left of the parliament, and those who supported it with greatest passion were what we would call the Right and even the clerical Right. The reason for this — and I think in some ways that both were rationally correct to hold those viewpoints — was that if given the chance to vote, women would most likely vote the way that their priest told them to vote and that women in this sense were a kind of force of conservatism. They would maintain the existing religious and aristocratic order. The far Left didn’t really want women to vote in this way.

We discussed a little bit last time about the idea of the majority strategy where you have the large White majority and it’s being dispossessed and attacked by a large rainbow coalition. The women are the kind of traitors or kind of wedge in this. Women, for whatever reason, maybe purely out of sentimentality, want to vote for center-Left parties, the parties that push the buttons about taking care of the children or whatever and they are kind of on the wrong side of the dispossession of America’s White historic majority.

So, again, it’s a very complicated issue and the social manifestations of women’s suffrage can occur in quite different ways.

Let me also ask another question about this. In some ways, I want to move on to second-wave feminism, because you find tracks that are at least more obnoxious, extreme, and things like this, but I want to stick just a little bit longer to pre-WWII feminism.

I’m thinking of someone like Margaret Sanger. She is in many ways a fascinating individual. Nowadays, she’s looked upon by many liberals as a wonderful, heroic, right-thinking woman who was fighting for the rights of women to use contraception and women’s rights in general.

But if we take a little closer look and you peel away a few layers of the onion, you find that she was a eugenicist of sorts, that she was afraid of the feebleminded and weak and so on and so forth overwhelming the healthier stock of America and that in a democracy something like that would be a truly terrible consequence. She would actually flirt with people like Lothrop Stoddard and Madison Grant, people who now would be considered totally beyond the pale, fascist, racialist types.

So, maybe in some of these first waves of feminism that we might think we know what it’s all about if we see it through the lens of modern Left-Right politics, so to speak, but actually it’s something quite different.

Do you have any thoughts on that? Some of the different strands of first wave feminism and how they’re kind of surprising when you look at them from our standpoint?

JB: Yes, I think that’s very true. I think first-wave feminism can’t be divorced from the class backgrounds of most of the women who advocated these positions. Although there’s been a careful pick and mix of the women concerned so that they seem part of a progressive continuum, there are many contradictions and (12:49 ???) that occur. It’s inevitable that these ultra-bourgeois women, for the most part, will often have radically conservative values and a few of them will have cross-fertilized Left-Right values and elitist values at that, despite the fact that they’re in favor of giving the vote to themselves.

This means that they’re not in favor of the vote for others. It also shouldn’t surprise us that when a lot of female literature is published in the late 19th/20th century — in a sense sort of elite literature — it turns out not to be Left-wing particularly. A lot of feminist publishing houses are bemused by the fact that a lot of the literature they publish from the early days isn’t really at all progressive, in their own terms and in the Left’s terms. That’s because the women who wrote it came from upper-class backgrounds. They were the women who were educated at the elite university level in all-female colleges during that era and their values and what they produced reflect that.

You also have a marked partiality for forms of ultra-conservatism among certain early female champions and it’s not for nothing that some of the political leaders who emerge first from the dispensation that gives women the vote turn out to be on the Right rather than on the Left.

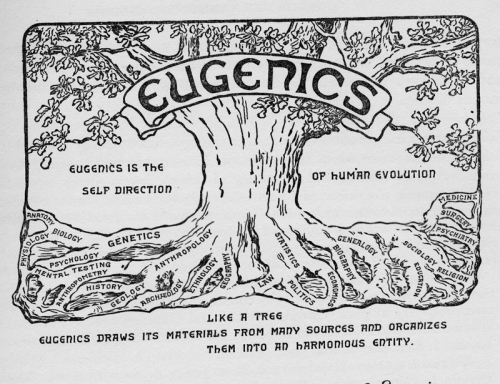

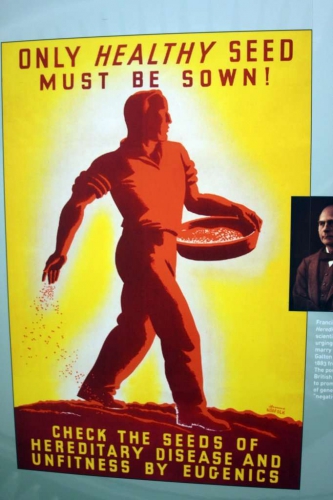

Over time, eugenics and feminism have almost completely separated out, but because feminism is concerned with biological and reproductive health and wanted to give women control of it . . . Abortion, of course, cuts two ways. Although anathema to the Christian Right, abortion does feed into eugenics and gender. Indeed, without some concept of abortion you couldn’t have eugenics in a meaningful sense, because how are you to act to prevent these people that eugenicists believe shouldn’t be born or encouraged from being born in the first place? So, there’s an inevitable correlation between certain sociobiological and Darwinian ideas and certain evolutionary ideas and feminism of a particular sort, particularly un-ideological feminism.

So, it’s inevitable that the sort of Marie Stopes wing of the movement will come out of eugenics and family planning, and abortion and pro-choice movements are all deeply mired in feminism, on the one hand, and eugenics, on the other.

RS: Yes, actually the religious Right in the United States, and I assume in Europe as well, have picked up on this, and they’ll usually make inflated claims of abortionists. “They really want to rid the world of Africans,” or something like that or connect Margaret Sanger with Hitler and various things like that. Obviously, this kind of rhetoric is overdone, but it might actually have a kernel of truth to it. But it also points out the egalitarian nature of the so-called religious Right in the country.

Let’s move on to second-wave feminism and the 1960s. I would say that if you talked to the average Joe in the US or Europe who’s maybe a conservative-thinking guy with pretty normal good instincts when you say the word feminism he probably thinks of some woman who’s maybe tattooed and earringed and has totally outrageous views and hates men and probably got dumped at prom or the dance or something and became a lesbian and is driven purely by her resentment. He probably has that kind of man-hating feminist stereotype in his mind. In some ways, a lot of that is associated with that second-wave feminism that came with the New Left, which came with the ’68 revolutions and so on and so forth in the US and Europe.

So, Jonathan, maybe you can give us an introduction to this movement and it obviously has a quite different vibe, so to speak, to it. It probably has a different philosophical grounding as well. It might not even be related to earlier feminism. But what are your views on the impulse behind feminism that arose in the 1960s and beyond?

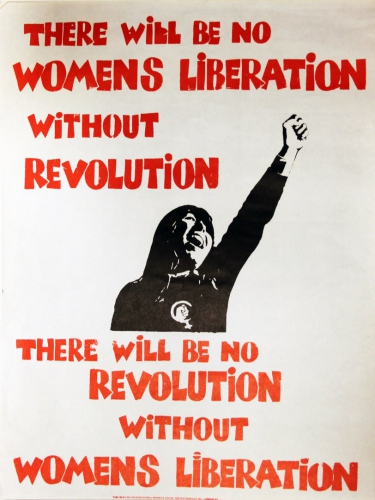

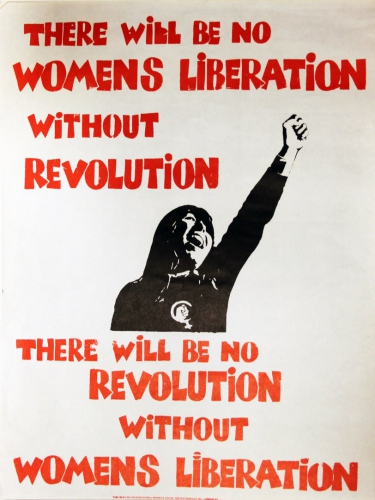

JB: Yes, I think this is the feminism that most people associate the term by whatever their view. Feminism in the ’60s and thereafter and some of its precursors in the late ‘50s tends to be a movement that is concerned almost completely with revolutionary politics, particularly sexual and psychological revolutionism. It only just about fits into Marxism because it relates to biological or pseudo-biological and sort of quasi-biological theories. It’s associated with a range of alternative society and slightly madcap women like Germaine Greer, who wrote a book called The Female Eunuch which at one level was quite well done but is a hysterical rant about the role of women in society, most of which is utopian in a way. It wants the female role to be changed out of all recognition. To such a degree that you could argue that one of the subtexts is that women become men over time and men become women over time, which was one of the unstated psychological goals of second-wave feminism. To see a feminization of men, in relative terms, and a masculinization of women, in relative terms. And that’s not an entirely stupid notion when you look at the theories some of them were proposing.

RS: Well, they seem to have succeeded in this to a large degree.

JB: Yes, well, feminism is unusual in that it’s one of those revolutions that’s succeeded. In absolute terms, of course, it’s completely failed because it addressed itself to utopias that are not possible of realization. Things like radical feminism, the total separation of female and male lives. Women living separate beehive-like existences in communes. That’s all failed.

RS: I’ll jump in here and then you can get back to your thought, but Alex Kurtagić was suggesting that I read Valerie Solanas’ tract, The SCUM Manifesto, and SCUM in this instance means the Society for Cutting Up Men.

JB: That’s right. She was an American, of course, and a schizophrenic. But she was the most extreme feminist that there’s ever been. Other feminists partly regard her tirade as sort of exhibitionistic, Sadean, and tongue-in-cheek. But yes, it advocates physical attacks on men and, of course, she did attack Andy Warhol. She shot him in the stomach with a gun from which he later recovered, and she was imprisoned for three years because of that. She got off quite lightly because it was regarded as an act of insanity.

Yeah, she represent in some ways the lunatic fringe, even the lunatic fringe of the lunatic fringe, within that particular movement. Although there will be feminists who will defend her, because she represents a sort of nethermost position or a position that it’s not possible to get beyond, a virulently man-hating position. Misandrist, I think it is, a word that’s never used, really, but means female detestation of men. Misogyny being a male detestation of women, which is a quite well-known word.

If you take a book like The Women’s Room by Kate Millett [Note: Marilyn French wrote the book by that title. Bowden could be referring to French or to another book by Millett, perhaps The Basement] there’s as strong a detestation of men in that than anything in Solanas, but it’s not expressed in as grotesque a way. So, Solanas’ is a deliberately absurdist text.

But that wing of feminism, Radical Feminism as it’s called with a large R, which is counter-propositional biologically and yet is rooted in biology, because it wants a total separation of the sexes and in the end advocates lesbianism even for heterosexual women. Hence books like Lesbian Nation and that sort of thing which come out of this particular milieu.

Feminist groups had internal debates in the ’70s and ’80s about lesbianism when the vast majority of women had to confess that they were biologically heterosexual and therefore this wasn’t an option for them. And they had endless debates about whether they should have political lesbianism instead, but it never really got anywhere.

So, that wing of feminism, the more lunatic fringe, radical elements of what is anyway a radical doctrine, has fallen by the wayside, although there are important theorists associated with the anti-pornography movement such as Andrea Dworkin and so on who come out of the radical wing who are still current.

So, that wing of feminism, the more lunatic fringe, radical elements of what is anyway a radical doctrine, has fallen by the wayside, although there are important theorists associated with the anti-pornography movement such as Andrea Dworkin and so on who come out of the radical wing who are still current.

Yet another odd reverberation is the association that anti-pornography feminism has with conservatism, particularly religiously motivated conservatism. Unlike libertarianism, for example, which would take a laissez-faire attitude towards commercial pornography.

RS: Yeah, let’s put some pressure on this. I actually had porn down as an important subject I wanted to discuss. It obviously didn’t, at least to my knowledge, come up with first-wave feminism, but you have an interesting anti-porn movement that did work hand-in-glove with the religious Right, so-called. You also had, I believe, porn’s first leading lady, Lovelace — I’m forgetting her first name — who was in Deepthroat, one of the early large pornography movies. I think it was the first feature film that was porn, and Lovelace eventually became part of the anti-porn movement and worked with Dworkin and people of this nature.

Again, it gets back to how I opened the conversation. What makes feminism this lasting movement is this ability to mutate and its ability to take on contradictory positions. Because you have now throughout the ’90s and 2000s, I’m sure it’s still going on, whole courses at major universities in the United States, and Europe I’m sure as well, on porn as this way of female power or pure liberation or they probably have other terminologies to describe it that I don’t even understand.

In some ways, there’s almost a yin and a yang to this. There’s the evils of something like pornography, is it’s just expressing how men want to treat women as objects and want to abuse them and so on and so forth, but then porn might be seen on the flipside as this pure expression of a kind of Marcusean, id-driven society of pure liberation and social relations as an orgy and so on and so forth.

Maybe this is part of the power of feminism. It can kind of flip back and forth and radically re-evaluate its social positions.

JB: Yes, I think that’s true, but in a way it’s bound to be like that, because it is slightly ridiculous that half of mankind has a viewpoint. If there was a movement called manism, if there was a movement of men. They’d immediately divide into all the subsections, because men don’t agree on anything.

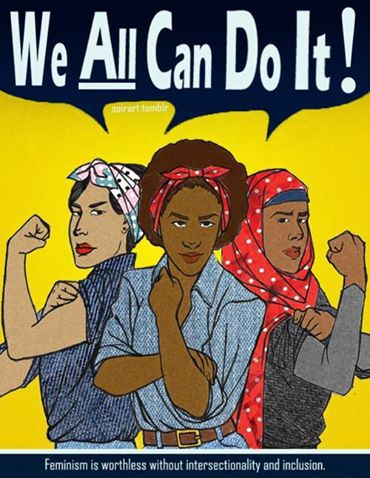

So, there’s a degree to which to expect women to agree on anything beyond a few superficials is fraught with difficulty. So, you have to frame the thing that women feel they’re in a subsidiary place and therefore that gives them an alliance with each other that then allows them to align around certain core issues. But even then they’ll still be divided on most other issues.

RS: And there’s the Marxian legacy where it’s almost like the female as the proletariat. They are oppressed by the current state of being and therefore they become a sort of world historical actor. They become the universal subject or something. It’s like a Marxianism gendered, so to speak.

JB: Yes, there’s a bit of that going on. Although amongst conservative women, and Dworkin once wrote a book called Right-Wing Women, which is about Right-wing women on the Right of the Republican Party because those are the most discernible Right-wing women that she could find, and they’ve always been a source of fascination to feminists. What makes women otherwise conventional and adopt what they consider to be a male-concentric view once they’ve achieved just civic equality in terms of careers and jobs and money and things of that sort?

Of course, there’s a large area of social conservatism which is part of the female view as well. The view that basically women have a different role in life to men and have different tasks in life to men, but they’re not particularly concerned if they’re allowed to do male tasks. So, if a woman wants to be a judge and goes all out to be one the general conservative female attitude now is, “Why shouldn’t she be one?” And she might be quite a tough-minded Right-wing judge at that when it comes down to it. But they don’t think the world should be up-ended so that women can be judges. It’s just an add-on to the female role that remains otherwise unchanged.

Feminism, like a lot of these movements, is a movement that’s only superficially touched the lives of the overwhelming majority of women. Still, after all the propaganda the other way, 67% of women, about 2/3rds of all women in most societies, want the traditional option. They want some sort of stable marital or other union and they want a family with children and that’s pretty much what they want. And feminism doesn’t really have much to say to those sorts of women, although it always postulates the notion that it never stops trying to address them.

So, the bulk of women remain uninfluenced by it, although they have taken advantage of the successes that feminism has scored because although it’s one of these movements that can be seen to have failed completely in its own utopian terms its effect on society has been so great and its effect on men has been so great that in a way it has succeeded far more than other radical currents far more than other ideological currents. It has succeeded because it has forced the law to maximalize those areas of female-male equality and to disprivilege areas of inequality that did exist in the social and civic space between men and women to the degree that now men who talk openly about opening those spaces up again are frowned upon by other men and are in a very small minority.

RS: Yes. You know, it’s interesting. Just to tell two quick little anecdotes. I did notice . . . I’m now involved in an oppressive bourgeois marriage, but when I was dating I did notice that it was still tacitly accepted that I would be paying for every meal, and if I happened to take a girl on a date and say, “Oh, do you want to split it down the middle?” or something like that I would probably get a very nasty look. At the same time, if during that date I ever suggested something like, “Don’t you think since men are the head of the household that maybe they should be paid more across the board, that that’s a good thing and it’s not really unfair? It’s actually fair because men have more financial obligations than women.” Again, I would probably get a horrified and disgusted look.

So, I think feminism succeeds in particular areas, maybe fails in a couple, but does succeed in general.

Let me talk a little bit about someone totally different than someone like Valerie Solanas, who I am sure most people in the population, even someone who would call themselves a feminist, would probably declare she was mentally ill, and maybe she was acting purely out of hatred. And that is the kind of modern girl feminism that represents a kind of compromise solution for women that is actually quite attractive and is about them playing with the big boys at work or having the ability to get a job. Even if they eventually might want to have a family a little bit later that they still have the opportunity to go become a stockbroker or something like this if they want to.

If you meet these women, they are otherwise normal and healthy. They don’t hold any views of men as evil or should be destroyed or anything like that. So, it’s a kind of acceptable compromise feminism.

I don’t want to make this too much of a leading question, but I think it is worth pointing out that since the 1970s real wages have either stagnated or, probably more likely, declined. What I mean by real wages is the wage paid to the head of a household minus inflation. Essentially, the wage is not keeping up with price increases. What we had in the ’80s and ’90s was in essence “mom went to work.” Dad, if he had a normal job, he could no longer sustain a family of four. It was impossible, particularly with education costs, medical costs going up and so on and so forth. So, in a way, mom had to go to work and that dovetailed with this more palatable feminism that came out of all these waves of feminism.

So, in a way, one could say that the Gloria Steinems of the world are the central bankers’ useful idiots. What I mean by that is that due to things like inflation and economic malfeasance it was impossible for the single breadwinner to have a family and these women were out there thinking that they were suggesting something radical by suggesting that women go to work, but really they were just justifying and maybe even sugarcoating the economic decline of the Western world.

I guess that’s kind of my own take on it there, but you can pick up on that if you’d like to talk about that economic element to it. But maybe, Jonathan, you could just talk about that more palatable kind of compromise feminism which seems to be embraced by, I would say, a vast majority of women.

JB: Yes, it’s a sort of very practical solution and women have always bene a very practical sex at one level of consciousness. This middling solution, where you take a little bit of the small R radical feminism and kick the rest into touch and basically can see it as a conceit and as a way to move forward on the career front, is an eminently sensible way of looking at it. It’s not necessarily what men always wanted, but it’s a solution that in a sense neuters the more virulent aspects of feminism whilst retaining a considerable dose of it.

There was a theorist in the 1920s called Wyndham Lewis who wrote a book in 1926, I think, called The Art of Being Ruled in which he suggested that capitalism was the real motivating force behind feminism, because the whole point was that the family was an archaic and reactionary institution that was pre-modern and floated uneasily in the marketplace and dammed up any alternative lifestyle. All these producers and consumers that could be let loose, but they could only be let loose if women were prized out of the home and were treated as auxiliary men and were used in the workplace in that manner.

It’s a remarkably prescient analysis given that it was regarded as quite mad when he came up with it in the 1920s. It accords almost painstakingly with what’s actually happened.

RS: Yes, without question. Also, the welfare state benefits from it. You have women working, they’re paying more taxes. Divorce benefits certain economic groups. If you’re owning apartments, you’re going to benefit by the family no longer being intact. So, in a kind of horrible way, feminists are again the useful idiots of the banking system and American capitalism.

JB: Yes, and you see that in the cultural area as well. The sort of Sex and the City feminism totally divorced in many ways from the lifestyle and instincts of the Left, which can be quite puritanical, goes with a hedonistic market capitalism. You see this sort of combination of feminism and libertarianism and feminism and libertarian capitalism and the two going along together. You see this in the sort of females’ issues magazines like Cosmopolitan, which are the female equivalent of pornography in many ways motivated again by the market and what it is felt the market will bear and is quite distinct from the traditional romantic fiction, so-called female emotional pornography, which are endless stories fictionalized about romances between men and women which tend to adopt deeply socially conservative and sort of old-fashioned timbre.

Cosmopolitan and Sex and the City are the exact inverse of all of that and advocate an almost predatory and slightly sluttish sort of sexuality for women that traditional moralists were appalled by and women as a whole have tended to regard as a harmful lifestyle for women but is now a sort of market-tested to destruction attitude that’s favored on every newsstand.

RS: Oh, without question. I don’t want to sound too haughty by saying this, but I’m afraid that too many of the women who move to, say, London or Manhattan, they get a job and they’re little miss career gal and they live the Sex and the City lifestyle and at some point in their mid-40s they wake up alone and lonely living with cats. Again, I’m not trying to demean anyone. It just seems to be the case and there seems to be a hangover of the Sex and the City lifestyle, which is something I don’t think anyone wants.

So, Jonathan, expound a little bit, if you would, on how feminism has changed men. I think it’s something a lot more complicated than wussification or men have become like women. I think it’s something deeper and more varied than that.

JB: Yes, I think it is. I think what’s happened is that a whole storehouse or memory chain of male archetypes and types has gone down, has been sort of zapped and factored down. Certain types of raw heterosexuality in a relatively traditional and very Masculine, capital M, have gone away and gone down the memory hole, but so have elements of the dandy and the sort of over-stepping, flamboyant heterosexual. Those roles, which were quite marked and quite varied, and bohemian male roles as well of a traditional type. They’ve gone as well or they’ve been rather neutered and confined as well.

There’s a whole intermediate zone of masculine identities who had their card marked and have gone into the past. The question is why has this occurred? And I think the motivation is almost completely male and completely internalized. I think it’s many men do not feel that they can be successful in private life, do not feel they can attract the women they wish to attract or be seen as attractive to such women and certainly not get alongside of them if they are otherwise than the present sort of postmodern man. They feel like they’ve got really no chance in the private lifestakes if they remain loyal to traditional and rather heedless masculinities that are in conflict with the egalitarianism of the present order.

There’s a whole intermediate zone of masculine identities who had their card marked and have gone into the past. The question is why has this occurred? And I think the motivation is almost completely male and completely internalized. I think it’s many men do not feel that they can be successful in private life, do not feel they can attract the women they wish to attract or be seen as attractive to such women and certainly not get alongside of them if they are otherwise than the present sort of postmodern man. They feel like they’ve got really no chance in the private lifestakes if they remain loyal to traditional and rather heedless masculinities that are in conflict with the egalitarianism of the present order.

This is something where theory is all very well, but if you want to have a happy or beneficent life you have to do various things to make that turn around in the private area and men have basically just bitten on the bullet really and adopted a whole new set of masculine constructs in order to be successful with women and they think they’ve actually been quite clever because they’ve adopted an element of male feminist language, posture, and behavior in order to get on with women once equality was formalized in civics and in law and in social behavior.

Men haven’t changed deep down that much maybe, but behaviorally they’ve changed a great deal, and this goes to show that men don’t revert to something else when they’re on their own these days except very occasionally and under the influence of all-male banter or drink or whatever. But that’s pretty rare and it’s not the reversal that scandalized feminists would expect on the whole either.

So, I think that a lot of men feel that in order to have successful families, in order to have successful private lives, they need to downplay certain prior forms and play up certain attitudes and variants which are acceptable today. And I think that’s happened right across the board.

RS: Yes, as we discussed off-air, our side sometimes underestimates the importance of that 20% of things that is nurture as opposed to nature and, in the case of men, it’s almost as if the post-feminist man is a new, different biological species. I mean, he’s not exactly, but that nurture end of the equation is quite powerful.

JB: Yes, well, no one would engage in politics, no one would engage in any social ideology if the 20–25% of the things that is nurture as against nature was unimportant. So, it’s in some ways the crucial vortex through which everything becomes what it’s bound to be. If you just left it to nature, you would end up with a semblance of what nature wanted, but you would probably give the game away to all sorts of people who wish to denature nature as much as possible. So, nature on its own isn’t enough and men have not fundamentally biologically changed, but their behavior has altered out of all recognition.

If your average man in the 1920s looked at what happened today, he’d be baffled. And yet a part of him wouldn’t be, because he’d just perceive it as a tactic that is adopted in order to be successful.

RS: Do you think that’s all it is, a tactic?

JB: It’s a tactic that goes quite deep. It’s rather like learning a stage part in a play, but you learn it so well it sort of becomes your unguent. It becomes what you wish to be when you’re off set. I think it’s a part that’s been learned to such a degree that it’s become second nature now.

Maybe that proves that part of the prior masculinities were also slightly rhetorical that they’ve proved themselves to be so adaptable and so changeable. But I think it’s the pressing need to be successful in this area that is the prime motivator.

Also, I just think it goes with the egalitarian discourse. Because what is the alternative? Is the alternative a cult of male superiority? Many men would feel uncomfortable with that because the idea of superiority and hence inferiority in any area strikes people as axiomatically discomforting in present circumstances.

RS: To bring this conversation to a close, let’s talk a little bit about the woman question from a deeper and anthropological standpoint and that is the role of the woman in the West. Certainly, it’s no coincidence that many of these feminist movements were arising out of Europe writ large. Even if you want to blame it on Marxism, it’s arising out of the European milieu at some level. A lot of that has to do with the fact that, despite some of the horror stories told by Leftist academics, women are treated better in the Western world than they are in the rest of the world, quite frankly.

One likes to imagine the oppressive bourgeois marriage or something, but in comparison with most other gender relations around the world the oppressive bourgeois marriage is quite equitable. So, it’s probably no surprise that feminism would grow out of the Western world.

There seems to be a tension in the West between let’s just call it liberalism granting people more equality, thinking that people can transcend their biological or material rootings and kind of decide for themselves and then also another deep Western tradition, which is the family.

I should point this out. If one wants to be a crude Darwinist, in some ways the monogamous family is also a great victory for feminism. I mean, obviously, if we were going to live in a truly Darwinian atmosphere we’d have some sort of polygamy where the big man, strongest guy gets all the women, and all the weaklings are either killed or serve as slaves or something.

But in many ways this tradition of the family and monogamous relations, a very deep tradition, one that predates Christianity, that is also something uniquely Western. You don’t see a lot of monogamy in, say, the Old Testament or Semitic traditions. You see polygamy and tribal relations. But that monogamous family is something uniquely Western.

So, just taking up on some of these thoughts that I’ve put forward, Jonathan, what do you think from an anthropological standpoint is the role of the woman in our European culture?

JB: Yes, I think it’s really the traditional role. It’s the role that predates ’60s feminism. I think it can be compatible with doing various jobs, but I think it is the mother’s role and traditional female roles extended out into the educational area, into nursing, into areas like that. But essentially the mother role, the Madonna role . . . Of course, there is a sexual role as well. And the scarlet female role is part of that continuum. It has to be because all areas have to be covered by it. So, that’s all part of the package.

JB: Yes, I think it’s really the traditional role. It’s the role that predates ’60s feminism. I think it can be compatible with doing various jobs, but I think it is the mother’s role and traditional female roles extended out into the educational area, into nursing, into areas like that. But essentially the mother role, the Madonna role . . . Of course, there is a sexual role as well. And the scarlet female role is part of that continuum. It has to be because all areas have to be covered by it. So, that’s all part of the package.

All of those survive in the West quite markedly, actually, despite feminism’s impact. So, feminism’s changed everything, yet everything’s remained the same. All of the female lifestyles that pre-existed feminism co-exist with those that have been changed by it.

I think what’s really happened is that feminism hasn’t changed women at all. It’s changed certain patterns of female opportunity, but it hasn’t changed women one iota. What it has changed is it’s changed men a great deal.

I think men have been the real recipients of feminist ideology, and it’s men who have been transformed by it or have been reluctantly so transformed because they feel as though there’s no option but to accept a certain dose of it in order to have some successful private life.

So, I personally believe it’s feminism’s action on the male agenda that’s the crucial issue. Women have changed to a degree, because they’ve adopted some of its vocabulary, but men have had to adapt in a much, much greater degree because it was an alien vocabulary as far as they were concerned. They have adopted it, and they have had to get rid of or junk an enormous prior traditional male set of vocabularies, only a proportion of which are heard anymore even amongst men even when they’re on their own.

Feminism has bitten very deep and has changed men and probably not for the best. If you look at the way men are depicted in 1950s films, which is before the cultural watershed, and how men and women are depicted and allow themselves to be depicted, and depict themselves more is the point, from the 1970s onwards you notice a really radical transformation in the way masculinity is configured, the way heroic masculinity is configured, the way all forms of masculinity are configured. Certain traditional forms of masculinity where the Humphrey Bogart character slaps the woman because she’s misbehaving would now be regarded as so unacceptable as to cause a frisson if they were to occur in contemporary cinema, for example.

RS: Well, it’s interesting that there’s a deep ambivalence with all of this. I’ve noticed this with the success of the television show Mad Men, which in some ways represented men behaving badly so women could kind of gawk at the oppressiveness and outmodedness. So, you’d have men openly hitting on their secretary and lots of ass-slapping and having little affairs during lunch breaks and so on and so forth.

At the same time, if it were just that I don’t think it would be a successful show. It might be a successful show for men, you know, on the Spike network, the stupid jock all-men programming cable network. But the reason why Mad Men was successful was at some level that Don Draper figure, that tall, dark, masculine, strong, self-confident, willing to put someone in their place type of man is something deeply attractive to women, and it’s something they continually long for maybe even despite themselves, certainly despite feminism.

But, Jonathan, I think we have just scratched the surface on this issue. Thank you for being with us and I look forward to talking with you again next week.

JB: All the best! Bye for now!

Related

The Iraqi nation grew increasingly wealthy, as oil revenues rose from $500 million in 1972 to over $26 billion in 1980, an increase of almost 50 times in nominal terms.

The Iraqi nation grew increasingly wealthy, as oil revenues rose from $500 million in 1972 to over $26 billion in 1980, an increase of almost 50 times in nominal terms.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

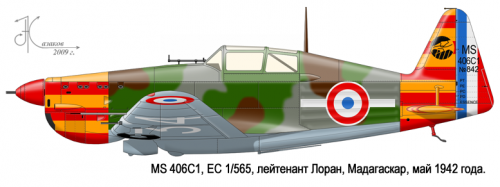

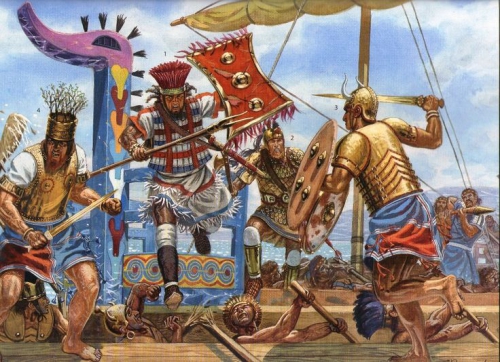

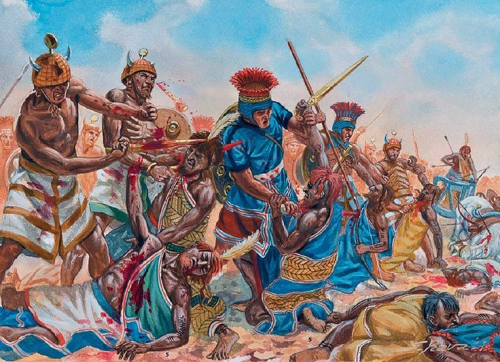

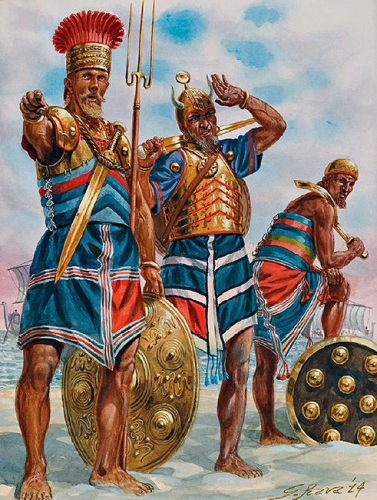

La Thaïlande, qui s’appelait alors le Siam, voit arriver, fin 1940, l’heure de la revanche. En effet, l’humiliante politique de la canonnière, pratiquée par les Français dans la région en 1893, avait conduit à la défaite des Siamois. Au début du mois de janvier 1941, les Thaïs attaquent avec deux divisions, soit 60.000 hommes et 130 chars. Les Français de Vichy sont commandés par l’Amiral Jean Decoux. Ils sont obligés de battre en retraite. L’aviation siamoise bombarde Hanoi le 11 janvier 1941. Les chasseurs de Vichy interceptent les avions thaïlandais et abattent trois chasseurs ennemis et un bombardier. Mais ils perdent également trois appareils.

La Thaïlande, qui s’appelait alors le Siam, voit arriver, fin 1940, l’heure de la revanche. En effet, l’humiliante politique de la canonnière, pratiquée par les Français dans la région en 1893, avait conduit à la défaite des Siamois. Au début du mois de janvier 1941, les Thaïs attaquent avec deux divisions, soit 60.000 hommes et 130 chars. Les Français de Vichy sont commandés par l’Amiral Jean Decoux. Ils sont obligés de battre en retraite. L’aviation siamoise bombarde Hanoi le 11 janvier 1941. Les chasseurs de Vichy interceptent les avions thaïlandais et abattent trois chasseurs ennemis et un bombardier. Mais ils perdent également trois appareils.

So, that wing of feminism, the more lunatic fringe, radical elements of what is anyway a radical doctrine, has fallen by the wayside, although there are important theorists associated with the anti-pornography movement such as Andrea Dworkin and so on who come out of the radical wing who are still current.

So, that wing of feminism, the more lunatic fringe, radical elements of what is anyway a radical doctrine, has fallen by the wayside, although there are important theorists associated with the anti-pornography movement such as Andrea Dworkin and so on who come out of the radical wing who are still current.

There’s a whole intermediate zone of masculine identities who had their card marked and have gone into the past. The question is why has this occurred? And I think the motivation is almost completely male and completely internalized. I think it’s many men do not feel that they can be successful in private life, do not feel they can attract the women they wish to attract or be seen as attractive to such women and certainly not get alongside of them if they are otherwise than the present sort of postmodern man. They feel like they’ve got really no chance in the private lifestakes if they remain loyal to traditional and rather heedless masculinities that are in conflict with the egalitarianism of the present order.

There’s a whole intermediate zone of masculine identities who had their card marked and have gone into the past. The question is why has this occurred? And I think the motivation is almost completely male and completely internalized. I think it’s many men do not feel that they can be successful in private life, do not feel they can attract the women they wish to attract or be seen as attractive to such women and certainly not get alongside of them if they are otherwise than the present sort of postmodern man. They feel like they’ve got really no chance in the private lifestakes if they remain loyal to traditional and rather heedless masculinities that are in conflict with the egalitarianism of the present order. JB: Yes, I think it’s really the traditional role. It’s the role that predates ’60s feminism. I think it can be compatible with doing various jobs, but I think it is the mother’s role and traditional female roles extended out into the educational area, into nursing, into areas like that. But essentially the mother role, the Madonna role . . . Of course, there is a sexual role as well. And the scarlet female role is part of that continuum. It has to be because all areas have to be covered by it. So, that’s all part of the package.

JB: Yes, I think it’s really the traditional role. It’s the role that predates ’60s feminism. I think it can be compatible with doing various jobs, but I think it is the mother’s role and traditional female roles extended out into the educational area, into nursing, into areas like that. But essentially the mother role, the Madonna role . . . Of course, there is a sexual role as well. And the scarlet female role is part of that continuum. It has to be because all areas have to be covered by it. So, that’s all part of the package.

En 1781, il passe en France afin de récolter des fonds pour la cause indépendantiste, puis se morfond dans la ferme que le nouvel État de New York lui a offerte pour ses bons services. En mai 1787, il propose à l’administration royale française, en grosses difficultés financières, un projet de pont métallique, qui sera réalisé en 1796, en Grande-Bretagne.

En 1781, il passe en France afin de récolter des fonds pour la cause indépendantiste, puis se morfond dans la ferme que le nouvel État de New York lui a offerte pour ses bons services. En mai 1787, il propose à l’administration royale française, en grosses difficultés financières, un projet de pont métallique, qui sera réalisé en 1796, en Grande-Bretagne.

In many ways the Progressive Era embodies the best of white America. It was a period of compassion, community concern, attempts to raise the living standard of average Americans, a desire to achieve class harmony, to end (or at least reduce) capitalist corruption, and to create a workable, harmonious racial nationalism that would ensure the long-term fitness of American society. The concerns of the Progressives were as much for the future as they were for the present, something almost wholly lacking in contemporary American politics. These scholars, politicians, and activists thought deeply about future generations and recognized, almost to a man, the validity of race science and the crucial role race plays in the historical trajectory of any country.

In many ways the Progressive Era embodies the best of white America. It was a period of compassion, community concern, attempts to raise the living standard of average Americans, a desire to achieve class harmony, to end (or at least reduce) capitalist corruption, and to create a workable, harmonious racial nationalism that would ensure the long-term fitness of American society. The concerns of the Progressives were as much for the future as they were for the present, something almost wholly lacking in contemporary American politics. These scholars, politicians, and activists thought deeply about future generations and recognized, almost to a man, the validity of race science and the crucial role race plays in the historical trajectory of any country.

The 1911 publication of Frederick Taylor’s The Principles of Scientific Management was a watershed moment for Progressives. It offered a scientific method for improving workplace efficiency. By measuring and analyzing everything from workplace break times to the weight of shoveled material, industry would be able to maximize efficiency down to the minute and the pound. Taylorism has since become an epithet, used to describe the dehumanizing effects of the time clock, the oppressive nature of constant managerial supervision, and the turn away from skilled labor in the workforce. However, for Progressives it promised a new approach to the workplace that could make life better for everyone. Those experts who would take charge of industry would be able to maximize the public good while minimizing the power of capitalists and financiers. Men such as the Progressive political philosopher Herbert Croly believed that Taylorism would “[put] the collective power of the group at the hands of its ablest members” (p. 62). For Progressives, scientific management was a noble goal and a model to be followed. It fit perfectly with their basic beliefs and soon spread elsewhere, including into the home, the conservation movement, and even churches (p. 66-69).

The 1911 publication of Frederick Taylor’s The Principles of Scientific Management was a watershed moment for Progressives. It offered a scientific method for improving workplace efficiency. By measuring and analyzing everything from workplace break times to the weight of shoveled material, industry would be able to maximize efficiency down to the minute and the pound. Taylorism has since become an epithet, used to describe the dehumanizing effects of the time clock, the oppressive nature of constant managerial supervision, and the turn away from skilled labor in the workforce. However, for Progressives it promised a new approach to the workplace that could make life better for everyone. Those experts who would take charge of industry would be able to maximize the public good while minimizing the power of capitalists and financiers. Men such as the Progressive political philosopher Herbert Croly believed that Taylorism would “[put] the collective power of the group at the hands of its ablest members” (p. 62). For Progressives, scientific management was a noble goal and a model to be followed. It fit perfectly with their basic beliefs and soon spread elsewhere, including into the home, the conservation movement, and even churches (p. 66-69). In chapter six, “Darwinism in Economic Reform,” Dr. Leonard relates how Darwinism was used by Progressives to acquire the “imprimatur of science” (p. 105). Darwinism proved to be a very flexible conceptual tool. It allowed for incorporation into various fields of thought and, within those, still more differing points of view: it was used to advocate for capitalism and for socialism; war and peace; individualism and collectivism; natalism and birth control; religion and atheism (p. 90). Darwinism and related ideas (such as Lamarckism) provided Progressives with a scientific basis upon which to argue for both economic improvement and biological improvement. There was no consensus on which aspects of Darwinism to incorporate into their logic but something the vast majority had in common was the belief in the importance of heredity and that artificial selection, as opposed to natural selection, was the most efficient means of securing a healthy society comprised of evolutionarily fit individuals.

In chapter six, “Darwinism in Economic Reform,” Dr. Leonard relates how Darwinism was used by Progressives to acquire the “imprimatur of science” (p. 105). Darwinism proved to be a very flexible conceptual tool. It allowed for incorporation into various fields of thought and, within those, still more differing points of view: it was used to advocate for capitalism and for socialism; war and peace; individualism and collectivism; natalism and birth control; religion and atheism (p. 90). Darwinism and related ideas (such as Lamarckism) provided Progressives with a scientific basis upon which to argue for both economic improvement and biological improvement. There was no consensus on which aspects of Darwinism to incorporate into their logic but something the vast majority had in common was the belief in the importance of heredity and that artificial selection, as opposed to natural selection, was the most efficient means of securing a healthy society comprised of evolutionarily fit individuals. These “unemployables” were seen as being parasitic. They undercut wages and threatened American racial integrity. The capitalist drive towards cheap labor was certainly seen as partly to blame for this problem, but Progressive discourse began to focus more on biology than economics. Blame was increasingly shifted towards the actual laborers themselves rather than the system that encouraged them to accept lower wages. In what was known as the “living-standard theory of wages,” the unemployables were seen as being able to live on less than the average American worker due to their willingness (either racially-determined or resulting from inferior minds) to accept poor living conditions. The white American worker, it was believed, would reduce his number of children rather than sacrifice his standard of living, thereby increasing the risk of Americans being outbred by inferior stock. This line of argument gained popular currency with the sometimes violent union activism against Chinese workers. Edward Ross wrote that “should wors[e] come to the worst, it would be better for us if we were turn our guns upon every vessel bring [Asians] to our shores rather than permit them to land” (p. 135). The notion of immigrants and others being regarded as scab labor was widely accepted across the political spectrum but was central to Progressive concerns because they were able to see it as symptomatic of multiple grave problems with American society. In order to correct these problems, better methods were needed to identify and exclude the inferiors who were threatening American jobs and lowering the American quality of life.

These “unemployables” were seen as being parasitic. They undercut wages and threatened American racial integrity. The capitalist drive towards cheap labor was certainly seen as partly to blame for this problem, but Progressive discourse began to focus more on biology than economics. Blame was increasingly shifted towards the actual laborers themselves rather than the system that encouraged them to accept lower wages. In what was known as the “living-standard theory of wages,” the unemployables were seen as being able to live on less than the average American worker due to their willingness (either racially-determined or resulting from inferior minds) to accept poor living conditions. The white American worker, it was believed, would reduce his number of children rather than sacrifice his standard of living, thereby increasing the risk of Americans being outbred by inferior stock. This line of argument gained popular currency with the sometimes violent union activism against Chinese workers. Edward Ross wrote that “should wors[e] come to the worst, it would be better for us if we were turn our guns upon every vessel bring [Asians] to our shores rather than permit them to land” (p. 135). The notion of immigrants and others being regarded as scab labor was widely accepted across the political spectrum but was central to Progressive concerns because they were able to see it as symptomatic of multiple grave problems with American society. In order to correct these problems, better methods were needed to identify and exclude the inferiors who were threatening American jobs and lowering the American quality of life.

C’est pour rompre avec cet obscurantisme officiel que j’invite le lecteur à parcourir quelques extraits du premier chapitre de l’excellente étude de l’historien britannique Norman Cohn, Les Fanatiques de l’Apocalypse (1957). Au travers du cas particulier du millénarisme antique et médiéval, on peut aisément s’apercevoir que la religion n’est pas une force transhistorique flottant au-dessus de la vie sociale, mais au contraire un produit de l’activité des hommes, fluctuant dans les remous de l’Histoire.

C’est pour rompre avec cet obscurantisme officiel que j’invite le lecteur à parcourir quelques extraits du premier chapitre de l’excellente étude de l’historien britannique Norman Cohn, Les Fanatiques de l’Apocalypse (1957). Au travers du cas particulier du millénarisme antique et médiéval, on peut aisément s’apercevoir que la religion n’est pas une force transhistorique flottant au-dessus de la vie sociale, mais au contraire un produit de l’activité des hommes, fluctuant dans les remous de l’Histoire. « Déjà les livres prophétiques de l’Ancien Testament, dont certains remontent au VIIIème siècle, décrivaient une immense catastrophe cosmique, dont émergeraient une Palestine qui ne serait rien de moins qu’un nouvel Éden, un paradis reconquis. Ayant négligé son Dieu, le peuple élu devait connaître la famine, la peste, la guerre et la captivité, avant d’être soumis à un jugement qui, par sa sévérité, effectuerait une rupture totale avec un passé coupable. D’abord viendra le Jour de Jéhovah, le jour de colère. Le soleil, la lune et la étoiles seront enveloppés de ténèbres, les cieux se replieront comme un parchemin qu’on roule, et la terre tremblera. Alors sonnera l’heure du Jugement qui verra les mécréants (c’est-à-dire les élus qui n’auront pas eu foi dans leur Seigneur et les païens, ennemis d’Israël) jugés et éliminés, sinon totalement anéantis. Mais ce ne sera pas tout : certains Juifs, « les restes salvifiques », survivront à ces châtiments et deviendront l’instrument des desseins de Dieu. Le peuple élu ainsi amendé et régénéré, Jéhovah renoncera à sa vengeance et se muera en Libérateur. Les Justes […] se regrouperont en Palestine et Jéhovah viendra s’établir parmi eux. Il sera leur Seigneur et leur Juge. Il régnera sur Jérusalem reconstruite, sur Sion devenue capitale spirituelle du monde, vers laquelle convergeront tous les peuples. […]

« Déjà les livres prophétiques de l’Ancien Testament, dont certains remontent au VIIIème siècle, décrivaient une immense catastrophe cosmique, dont émergeraient une Palestine qui ne serait rien de moins qu’un nouvel Éden, un paradis reconquis. Ayant négligé son Dieu, le peuple élu devait connaître la famine, la peste, la guerre et la captivité, avant d’être soumis à un jugement qui, par sa sévérité, effectuerait une rupture totale avec un passé coupable. D’abord viendra le Jour de Jéhovah, le jour de colère. Le soleil, la lune et la étoiles seront enveloppés de ténèbres, les cieux se replieront comme un parchemin qu’on roule, et la terre tremblera. Alors sonnera l’heure du Jugement qui verra les mécréants (c’est-à-dire les élus qui n’auront pas eu foi dans leur Seigneur et les païens, ennemis d’Israël) jugés et éliminés, sinon totalement anéantis. Mais ce ne sera pas tout : certains Juifs, « les restes salvifiques », survivront à ces châtiments et deviendront l’instrument des desseins de Dieu. Le peuple élu ainsi amendé et régénéré, Jéhovah renoncera à sa vengeance et se muera en Libérateur. Les Justes […] se regrouperont en Palestine et Jéhovah viendra s’établir parmi eux. Il sera leur Seigneur et leur Juge. Il régnera sur Jérusalem reconstruite, sur Sion devenue capitale spirituelle du monde, vers laquelle convergeront tous les peuples. […] On retrouve là l’essentiel de ce qui allait devenir le thème central de l’eschatologie révolutionnaire. L’univers est dominé par une puissance maléfique et tyrannique dont la capacité de destruction est infinie, puissance d’ailleurs conçue comme surhumaine et démoniaque. Sous cette dictature, les outrages se multiplient, les souffrances des victimes deviennent de plus en plus intolérables, jusqu’à ce que sonne l’heure où les saints de Dieu seront à même de se dresser pour l’abattre. Alors les saints eux-mêmes, le peuple élu, ce peuple saint, qui n’a cessé de gémir sous le joug de l’oppresseur, héritera à son tour de l’hégémonie universelle. Ce sera l’apogée de l’histoire. Le Royaume des Saints surpassera en gloire tous les règnes antérieurs : bien plus, il n’aura pas de successeurs. C’est par cette chimère que l’apocalyptique juive et ses nombreux dérivés, devaient exercer une incomparable fascination sur tous les insurgés, sur tous les mécontents à venir. » (p.16-19)

On retrouve là l’essentiel de ce qui allait devenir le thème central de l’eschatologie révolutionnaire. L’univers est dominé par une puissance maléfique et tyrannique dont la capacité de destruction est infinie, puissance d’ailleurs conçue comme surhumaine et démoniaque. Sous cette dictature, les outrages se multiplient, les souffrances des victimes deviennent de plus en plus intolérables, jusqu’à ce que sonne l’heure où les saints de Dieu seront à même de se dresser pour l’abattre. Alors les saints eux-mêmes, le peuple élu, ce peuple saint, qui n’a cessé de gémir sous le joug de l’oppresseur, héritera à son tour de l’hégémonie universelle. Ce sera l’apogée de l’histoire. Le Royaume des Saints surpassera en gloire tous les règnes antérieurs : bien plus, il n’aura pas de successeurs. C’est par cette chimère que l’apocalyptique juive et ses nombreux dérivés, devaient exercer une incomparable fascination sur tous les insurgés, sur tous les mécontents à venir. » (p.16-19) « Au IIIème siècle eut lieu la première tentative visant à discréditer les doctrines chiliastiques : Origène, le plus influent peut-être des théologiens de l’Église, assure en effet que l’avènement du Royaume se situera non pas dans l’espace et dans le temps, mais uniquement dans l’âme des fidèles. A une eschatologie millénariste collective, il substitue donc une eschatologie de l’âme individuelle. […] De fait, ce déplacement d’intérêt répond admirablement aux besoins d’une Église désormais organisée, jouissant d’une paix pratiquement ininterrompue et d’un statut universellement admis. Lorsqu’au IVème siècle, le christianisme établit son hégémonie sur le monde méditerranéen et devint la religion officielle de l’Empire, l’Église prit de plus en plus nettement ses distances à l’égard des théories chiliastiques. L’Église catholique, institutionnalisée, puissante et prospère, suivait une routine solidement établie, et ses responsables n’éprouvaient aucune envie de voir les chrétiens se cramponner à des rêves démodés et trompeurs d’un nouveau paradis terrestre. Au début du Vème siècle, saint Augustin élabora la doctrine correspondant à ces circonstances nouvelles. La Cité de Dieu explique que l’Apocalypse doit être interprétée comme une allégorie spirituelle. Quant au millénium, la naissance du christianisme en avait marqué l’avènement et l’Église en était la réalisation sans faille. Cette théorie prit rapidement valeur de dogme, au point que le Concile d’Éphèse (431) condamna la croyance au Millénium comme une superstition aberrante. » (p.32)

« Au IIIème siècle eut lieu la première tentative visant à discréditer les doctrines chiliastiques : Origène, le plus influent peut-être des théologiens de l’Église, assure en effet que l’avènement du Royaume se situera non pas dans l’espace et dans le temps, mais uniquement dans l’âme des fidèles. A une eschatologie millénariste collective, il substitue donc une eschatologie de l’âme individuelle. […] De fait, ce déplacement d’intérêt répond admirablement aux besoins d’une Église désormais organisée, jouissant d’une paix pratiquement ininterrompue et d’un statut universellement admis. Lorsqu’au IVème siècle, le christianisme établit son hégémonie sur le monde méditerranéen et devint la religion officielle de l’Empire, l’Église prit de plus en plus nettement ses distances à l’égard des théories chiliastiques. L’Église catholique, institutionnalisée, puissante et prospère, suivait une routine solidement établie, et ses responsables n’éprouvaient aucune envie de voir les chrétiens se cramponner à des rêves démodés et trompeurs d’un nouveau paradis terrestre. Au début du Vème siècle, saint Augustin élabora la doctrine correspondant à ces circonstances nouvelles. La Cité de Dieu explique que l’Apocalypse doit être interprétée comme une allégorie spirituelle. Quant au millénium, la naissance du christianisme en avait marqué l’avènement et l’Église en était la réalisation sans faille. Cette théorie prit rapidement valeur de dogme, au point que le Concile d’Éphèse (431) condamna la croyance au Millénium comme une superstition aberrante. » (p.32) « Cet état de choses se mit à évoluer à partir du XIème siècle, plusieurs régions d’Europe bénéficiant d’une paix assez durable pour permettre l’accroissement de la population et l’essor du commerce. […] Dès le XIème siècle, le Nord-Est de la France, les Pays-Bas et la vallée du Rhin avaient atteint une densité de population telle que le système agricole traditionnel se révélait incapable d’en assurer la subsistance. Nombre de paysans se mirent à défricher des forêts, des marécages et des franges côtières, ou prirent la route de l’Est pour participer à la grande colonisation allemande des terres slaves : ces pionniers eurent généralement la vie plus facile. Restaient de nombreux paysans sans terre, ou que leur lopin ne suffisait pas à nourrir : il leur fallait donc se débrouiller tant bien que mal. Une partie de cette population excédentaire alla grossir les rangs du prolétariat rural. D’autres affluèrent dans les nouveaux centres urbains et industriels pour donner naissance à un prolétariat urbain. » (p.48)

« Cet état de choses se mit à évoluer à partir du XIème siècle, plusieurs régions d’Europe bénéficiant d’une paix assez durable pour permettre l’accroissement de la population et l’essor du commerce. […] Dès le XIème siècle, le Nord-Est de la France, les Pays-Bas et la vallée du Rhin avaient atteint une densité de population telle que le système agricole traditionnel se révélait incapable d’en assurer la subsistance. Nombre de paysans se mirent à défricher des forêts, des marécages et des franges côtières, ou prirent la route de l’Est pour participer à la grande colonisation allemande des terres slaves : ces pionniers eurent généralement la vie plus facile. Restaient de nombreux paysans sans terre, ou que leur lopin ne suffisait pas à nourrir : il leur fallait donc se débrouiller tant bien que mal. Une partie de cette population excédentaire alla grossir les rangs du prolétariat rural. D’autres affluèrent dans les nouveaux centres urbains et industriels pour donner naissance à un prolétariat urbain. » (p.48)

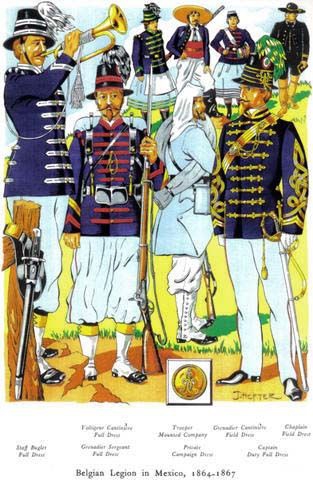

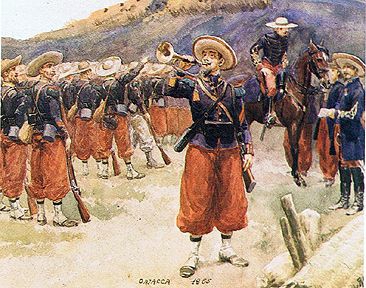

So ended the short life of Maximilian, and the much briefer life of Imperial Hapsburg Mexico. Often viewed as a sort of black comedy out of Evelyn Waugh—aristocratic simpleton moves to the tropics and gets lynched by noble savages—the Maximilian story is a grave one that reverberates to the present day. Put simply, Maximilian’s rule was a valiant attempt to turn a perpetually bankrupt, disorderly Mexico into something else—an orderly, prosperous, Europeanized country. A transformed Mexico, newly planted with arrivals from Austria, Hungary, Germany, France and, perhaps most importantly, the Confederate States of America.

So ended the short life of Maximilian, and the much briefer life of Imperial Hapsburg Mexico. Often viewed as a sort of black comedy out of Evelyn Waugh—aristocratic simpleton moves to the tropics and gets lynched by noble savages—the Maximilian story is a grave one that reverberates to the present day. Put simply, Maximilian’s rule was a valiant attempt to turn a perpetually bankrupt, disorderly Mexico into something else—an orderly, prosperous, Europeanized country. A transformed Mexico, newly planted with arrivals from Austria, Hungary, Germany, France and, perhaps most importantly, the Confederate States of America. The U.S.’s persistent and calculated support for the rebels shows that Maximilian’s fall was neither inevitable nor foreordained. Which makes it very compelling to imagine what might have become of Mexico had Maximilian’s cause prevailed. Would Imperial Hapsburg Mexico have become a sort of Austria-Hungary of the tropics, full of ski resorts, opera festivals and retirement chalet-condos in the Sierra Madre? Perhaps the current Hapsburg heir would be Emperor of Mexico.

The U.S.’s persistent and calculated support for the rebels shows that Maximilian’s fall was neither inevitable nor foreordained. Which makes it very compelling to imagine what might have become of Mexico had Maximilian’s cause prevailed. Would Imperial Hapsburg Mexico have become a sort of Austria-Hungary of the tropics, full of ski resorts, opera festivals and retirement chalet-condos in the Sierra Madre? Perhaps the current Hapsburg heir would be Emperor of Mexico. The many evasive characterizations of the Maximilian story—European interference, imperial aggrandizement, debt-collection, et al.—all avoid the fundamental reason why Maximilian was brought in. And that was the horrifying disorder and lawlessness that had characterized Mexico in the generation or so since independence. One can argue that disorder is just innate to Mexico. Regardless, the chaos had become particularly noticeable by the early 1860s, when after years of governmental corruption, the Benito Juarez administration announced it would default on the loans made by overseas investors. (The crisis that precipitated the 1862 military intervention by France, along with Britain and Spain.) A good example of this corruption, or incompetence, is shown by the Veracruz-to-Mexico City railway mentioned above. This had originally been planned, and concession granted, in 1837. But construction of the 300-mile route never really commenced till 1865, under Maximilian. At this time Mexico did not have a single long-distance railway.

The many evasive characterizations of the Maximilian story—European interference, imperial aggrandizement, debt-collection, et al.—all avoid the fundamental reason why Maximilian was brought in. And that was the horrifying disorder and lawlessness that had characterized Mexico in the generation or so since independence. One can argue that disorder is just innate to Mexico. Regardless, the chaos had become particularly noticeable by the early 1860s, when after years of governmental corruption, the Benito Juarez administration announced it would default on the loans made by overseas investors. (The crisis that precipitated the 1862 military intervention by France, along with Britain and Spain.) A good example of this corruption, or incompetence, is shown by the Veracruz-to-Mexico City railway mentioned above. This had originally been planned, and concession granted, in 1837. But construction of the 300-mile route never really commenced till 1865, under Maximilian. At this time Mexico did not have a single long-distance railway.

Pour son dernier et très ambitieux ouvrage, l’historien africanologue, auquel on doit déjà une Histoire de l’Egypte (1) et une autre du Maroc (2), a étudié son et plutôt ses sujets non pas géographiquement, mais chronologiquement, comme l’avait fait il y a trente ans Jean Duché pour sa passionnante Histoire du Monde (3). Choix judicieux car les destins des contrées concernées, et qui, depuis l’Antiquité ont durablement été soumises aux mêmes maîtres, l’Empire romain puis l’Empire ottoman s’interpénètrent. Avec la lecture « horizontale » adoptée par Bernard Lugan, on discerne mieux les interactions, les similitudes mais aussi les contradictions entre les cinq composantes de la rive sud de la Méditerranée, avec une inexorable constante : le facteur ethnique.

Pour son dernier et très ambitieux ouvrage, l’historien africanologue, auquel on doit déjà une Histoire de l’Egypte (1) et une autre du Maroc (2), a étudié son et plutôt ses sujets non pas géographiquement, mais chronologiquement, comme l’avait fait il y a trente ans Jean Duché pour sa passionnante Histoire du Monde (3). Choix judicieux car les destins des contrées concernées, et qui, depuis l’Antiquité ont durablement été soumises aux mêmes maîtres, l’Empire romain puis l’Empire ottoman s’interpénètrent. Avec la lecture « horizontale » adoptée par Bernard Lugan, on discerne mieux les interactions, les similitudes mais aussi les contradictions entre les cinq composantes de la rive sud de la Méditerranée, avec une inexorable constante : le facteur ethnique.

The ancient Greeks are more than strange beings so far as post-60s “liberal democracy” is concerned. Certainly, the Greeks had that egalitarian and individualist sensitivity that Westerners are so known for.

The ancient Greeks are more than strange beings so far as post-60s “liberal democracy” is concerned. Certainly, the Greeks had that egalitarian and individualist sensitivity that Westerners are so known for.

L’idéologie, domaine des idées, est la chasse gardée des intellos. Ceux-ci alimentent les politiciens ignares par des constructions abstraites, vendables aux masses, autrement dit une bouillie où l’on se pose surtout ‘contre’ et rarement ‘pour’. « Il y a les préjugés de tout ce monde ‘affranchi’. Il y a là une masse de plus en plus figée, de plus en plus lourde, de plus en plus écrasante. On est contre ceci, contre cela, ce qui fait qu’on est pour le néant qui s’insinue partout. Et tout cela n’est que faible vantardise » p.1131. Yaka…

L’idéologie, domaine des idées, est la chasse gardée des intellos. Ceux-ci alimentent les politiciens ignares par des constructions abstraites, vendables aux masses, autrement dit une bouillie où l’on se pose surtout ‘contre’ et rarement ‘pour’. « Il y a les préjugés de tout ce monde ‘affranchi’. Il y a là une masse de plus en plus figée, de plus en plus lourde, de plus en plus écrasante. On est contre ceci, contre cela, ce qui fait qu’on est pour le néant qui s’insinue partout. Et tout cela n’est que faible vantardise » p.1131. Yaka… On parle aujourd’hui volontiers dans les meetings de 1789, de 1848, voire de 1871. Mais la grande politique va bien au-delà, de Gaulle la reprendra à son compte et Mitterrand en jouera. Marine Le Pen encense Jeanne d’Arc (comme Drieu) et Mélenchon tente de récupérer les grandes heures populaires, mais avec le regard myope du démagogue arrêté à 1793. Or « il y avait eu la raison française, ce jaillissement passionné, orgueilleux, furieux du XIIè siècle des épopées, des cathédrales, des philosophies chrétiennes, de la sculpture, des vitraux, des enluminures, des croisades. Les Français avaient été des soldats, des moines, des architectes, des peintres, des poètes, des maris et des pères. Ils avaient fait des enfants, ils avaient construit, ils avaient tué, ils s’étaient fait tuer. Ils s’étaient sacrifiés et ils avaient sacrifié. Maintenant, cela finissait. Ici, et en Europe. ‘Le peuple de Descartes’. Mais Descartes encore embrassait la foi et la raison. Maintenant, qu’était ce rationalisme qui se réclamait de lui ? Une sentimentalité étroite et radotante, toute repliée sur l’imitation rabougrie de l’ancienne courbe créatrice, petite tige fanée » p.1221. Marc Bloch, qui n’était pas fasciste puisque juif, historien et résistant, était d’accord avec Drieu pour accoler Jeanne d’Arc à 1789, le suffrage universel au sacre de Reims. Pour lui, tout ça était la France : sa mystique. Ce qui meut la grande politique et ce qui fait la différence entre la gestion d’un conseil général et la gestion d’un pays.

On parle aujourd’hui volontiers dans les meetings de 1789, de 1848, voire de 1871. Mais la grande politique va bien au-delà, de Gaulle la reprendra à son compte et Mitterrand en jouera. Marine Le Pen encense Jeanne d’Arc (comme Drieu) et Mélenchon tente de récupérer les grandes heures populaires, mais avec le regard myope du démagogue arrêté à 1793. Or « il y avait eu la raison française, ce jaillissement passionné, orgueilleux, furieux du XIIè siècle des épopées, des cathédrales, des philosophies chrétiennes, de la sculpture, des vitraux, des enluminures, des croisades. Les Français avaient été des soldats, des moines, des architectes, des peintres, des poètes, des maris et des pères. Ils avaient fait des enfants, ils avaient construit, ils avaient tué, ils s’étaient fait tuer. Ils s’étaient sacrifiés et ils avaient sacrifié. Maintenant, cela finissait. Ici, et en Europe. ‘Le peuple de Descartes’. Mais Descartes encore embrassait la foi et la raison. Maintenant, qu’était ce rationalisme qui se réclamait de lui ? Une sentimentalité étroite et radotante, toute repliée sur l’imitation rabougrie de l’ancienne courbe créatrice, petite tige fanée » p.1221. Marc Bloch, qui n’était pas fasciste puisque juif, historien et résistant, était d’accord avec Drieu pour accoler Jeanne d’Arc à 1789, le suffrage universel au sacre de Reims. Pour lui, tout ça était la France : sa mystique. Ce qui meut la grande politique et ce qui fait la différence entre la gestion d’un conseil général et la gestion d’un pays. Mais la démocratie parlementaire a montré que la mystique pouvait surgir, comme sous Churchill, de Gaulle, Kennedy, Obama. Sauf que le parlementarisme reprend ses droits et assure la distance nécessaire entre l’individu et la masse nationale. Délibérations, pluralisme et État de droit sont les processus et les garde-fous de nos démocraties. Ils permettent l’équilibre entre la vie personnelle de chacun (libre d’aller à ses affaires) et la vie collective de l’État-nation (en charge des fonctions régaliennes de la justice, la défense et les infrastructures). Notre système requiert des administrateurs rationnels plus que des leaders charismatiques, malgré le culte du chef réintroduit par la Vè République.