mercredi, 20 novembre 2013

Als in Polen die Mark galt

Als in Polen die Mark galt

Während des Ersten Weltkrieges existierte ein von Hohenzollern- und Habsburgerreich errichteter polnischer Nationalstaat

Der 11. November 1918 markiert nicht nur das Ende der Kampfhandlungen des Ersten Weltkrieges, sondern für die Polen zugleich die Wiedergeburt ihres Staates, der 1795 mit der Dritten Teilung des Landes von der Landkarte verschwunden war. Beinahe in Vergessenheit geraten ist in diesem Zusammenhang aber, dass schon fast auf den Tag genau zwei Jahre vorher, nämlich am 5. November 1916, ein neuer polnischer Staat ins Leben gerufen worden war, der als „Regentschaftskönigreich Polen“ in die Annalen einging.

Da es vorläufig noch keinen König gab, wurde im Dezember 1916 zunächst ein Provisorischer Staatsrat als Regierung gebildet. Dieser bestand aus 25 Mitgliedern, wobei 15 aus den seit Beginn des Weltkriegs vom Deutschen Reich besetzten Teilen Kongresspolens kamen und zehn aus dem von Österreich-Ungarn okkupierten Landesteil. Ernannt wurden die Mitglieder des Staatsrates am 11. Januar 1917, die konstituierende Sitzung fand drei Tage später statt. Vorsitzender beziehungsweise Präsident mit dem Titel „Kronmarschall“ wurde Wacław Niemojowski, sein Stellvertreter Józef Mikołwski-Pomorski. Auch der spätere Nationalheld und Gründer der Republik, Józef Piłsudski, gehörte dem Staatsrat an. Er war dort für militärische Angelegenheiten zuständig. Es formierte sich auch ein Parlament, „Nationalrat“ genannt, das vom 16. bis zum 18. März 1917 tagte. Bereits am 9. Dezember 1916 war eine Polnische Nationalbank gegründet worden, die eine neue landeseigene Währung herausgab, die Polnische Mark.

Im April 1917 legte der deutsche Generalgouverneur Generaloberst Hans von Beseler mit Sitz in Warschau die Justiz sowie das Schul- und das Pressewesen in die Hände des Staatsrates. Im selben Monat erfolgte auch ein Werbeaufruf zur Gründung polnischer Streitkräfte. In ihr sollten nur ehemalige russische Untertanen, sogenannte Nationalpolen, dienen, wohingegen die Polen aus dem österreichisch-ungarischen Herrschaftsbereich in der k.u.k. Armee verbleiben sollten. Auf Kritik stieß auch die vom deutschen und dem österreich-ungarischen Generalgouverneur ausgearbeitete Eidesformel: „Ich schwöre zu Gott dem Allmächtigen, dass ich meinem Vaterlande, dem Polnischen Königreich, und meinem künftigen König zu Lande und zu Wasser und an welchen Orten es immer sei, getreu und redlich dienen, in gegenwärtigem Kriege treue Waffenbrüderschaft mit den Heeren Deutschlands und Österreich-Ungarns und der ihnen verbündeten Staaten halten … werde.“ Es gab Vorbehalte dagegen, auf einen König vereidigt zu werden, der noch gar nicht einmal bekannt war. Außerdem wurde kritisiert, dass eine Armee keinen Eid auf eine Waffenbrüderschaft leisten könne, denn nur der Regierung stünde es zu, Bündnisse abzuschließen. Gleichwohl bestätigte der Staatsrat am 3. Juli die Eidesformel, und Soldaten, die den Eid dennoch nicht ablegen wollten, wurden interniert. Aus Protest gegen diese Vorgänge waren Piłsudski und drei weitere dem linken Spektrum angehörige Mitglieder des Staatsrates am Tag zuvor von ihren Ämtern zurückgetreten. Am 22. Juli ließ man Piłsudski schließlich in Schutzhaft nehmen und verbrachte ihn zuerst in die Festung Wesel, später nach Magdeburg. Anfang August 1917 wurde dann die neu aufgestellte polnische Armee an die Ostfront verlegt. Nun zeugten sich die Meinungsverschiedenheiten über den weiteren Weg in aller Deutlichkeit. Ihr Höhepunkt wurde am 6. August erreicht, als Niemojowski darüber sein Amt als Kronmarschall niederlegte. Am 25. August stellte der Staatsrat seine Tätigkeit ein, und in seiner allerletzten Sitzung am 30. August bildete er einen auch „Übergangskomitee“ genannten Interimsausschuss, der vorläufig die Regierungsgeschäfte führen sollte und an dessen Spitze der bisherige stellvertretende Kronmarschall Mikołowski-Pomorski trat.

Bis zum 12. September des Jahres war eine provisorische Verfassung ausgearbeitet. Dieses sogenannte Patent beschrieb Polen als konstitutionelle Monarchie mit einem aus einem Abgeordnetenhaus und einem Senat bestehenden Zweikammerparlament. Bis zur Übernahme der Staatsgewalt durch einen noch zu bestimmenden König sollte diese von einem dreiköpfigen Regentschaftsrat ausgeübt werden, in den man sechs Tage später folgende Personen berief: Aleksander Kardinal Kakowski, Erzbischof von Warschau, Fürst Zdzisław Lubomirski, Stadtpräsident (Oberbürgermeister) von Warschau, und Józef Ostrowski, vormals Vorsitzender des Polenklubs in der russischen Duma in St. Petersburg. Am 15. Oktober 1917, dem 100. Todestag des polnischen Nationalhelden Tadeusz Kosciuszko, wurde der Regentschaftsrat vereidigt. Am 27. Oktober trat er offiziell sein Amt an.

Genau einen Monat später kam es zur Einsetzung einer ersten ordentlichen Regierung unter Ministerpräsident Jan Kucharzewski, nachdem zuvor seit dem 1. Februar 1917 lediglich eine provi-sorische Regierung unter Michał Łempicki, einem Mitglied des Provisorischen Staatsrates, amtiert hatte.

Am 4. Februar 1918 wurde ein Gesetz über die Schaffung eines Parlaments erlassen, das die Bezeichnung „Staatsrat“ erhielt. Dieser setzte sich aus 110 Abgeordneten zusammen. 55 davon wurden von den Gemeinden und Regionalräten am 9. April 1918 gewählt, 43 wurden vom Regentschaftsrat ernannt, und zwölf gehörten ihm kraft ihres Amtes beziehungsweise aufgrund einer Funktion an. Zu letzteren zählten Bischöfe ebenso wie Universitätsrektoren und der Präsident des Obersten Gerichtshofes. An der Spitze fungierte als „Sprecher der Krone“ ein Marschall, ab dem 14. Juni 1918 Francis John Pulaski. Daneben saßen im Parlamentspräsidium zwei Vizemarschälle, Józef Mikołowski-Pomorski und Stefan Badzynski, sowie vier Beisitzer (Sekretäre). Am 21. Juni fand die feierliche Eröffnung statt, und bis zum 7. Oktober, als man die Arbeit einstellte, folgten insgesamt 14 Plenarsitzungen.

Bereits am 6. Januar 1918 war der Regentschaftsrat zum Antrittsbesuch beim Deutschen Kaiser und beim Reichskanzler nach Berlin gekommen. Drei Tage später reiste man weiter nach Wien.

In Polen selbst war man besorgt, ja sogar empört, dass die deutschen Militärbehörden am 11. Dezember 1917 einen unabhängigen litauischen Staat mit Wilna (Vilnius) als Hauptstadt proklamiert hatten, war doch gerade diese Region in der Mehrheit von Polen besiedelt, weshalb die Regierung in Warschau dort auch Territorialansprüche stellte. Dies, die Forderung aus deutschen Militärkreisen nach Schaffung eines „Schutzstreifens“ auf polnischem Gebiet entlang der Grenze zum Deutschen Reich und schließlich die Weigerung der deutschen Besatzungsbehörden, statt nur einer eigeschränkten die volle Verwaltung an die Polen zu übergeben, riefen in der Bevölkerung zunehmend eine antideutsche Haltung hervor, was wiederum den Befürwortern einer austropolnischen Lösung in die Hände spielte, also einer Vereinigung Polens mit dem Habsburgerreich unter einer gemeinsamen Krone. Der österreichische Kaiser Karl I. ging im August 1918 sogar auf Distanz zu allen deutschen Plänen, erklärte eine Anwartschaft Erzherzog Karl Stephans auf die polnische Königskrone für obsolet und favorisierte stattdessen die erwähnte austropolnische Lösung mit ihm selbst als Herrscher über das gesamte Imperium.

Währenddessen wandte sich das Blatt immer mehr zu Ungunsten der Mittelmächte. Am 6. Ok-tober 1918 erklärte der Regentschaftsrat in Warschau die 14 Punkte des US-amerikanischen Präsidenten Woodrow Wilson zur Grundlage einer polnischen Staatsbildung, am folgenden Tag verkündete er gar die vollständige Unabhängigkeit Polens und löste zugleich das Parlament, den Staatsrat, auf. Der deutsche Generalgouverneur von Beseler legte daraufhin die gesamte Administration in polnische Hände und übertrug dem Regentschaftsrat am 23. Oktober auch den Oberbefehl über die polnischen Truppen.

Und dann ging alles ganz schnell: Am 6. November bildet sich unter der Führung des Sozialisten Ignacy Daszynski in Lublin eine „Provisorische Volksregierung der polnischen Republik“, die den Regentschaftsrat für abgesetzt erklärte. Das rief in Warschau den Protest gemäßigter Kräfte hervor, und weil sowohl der Regentschaftsrat als auch dessen Kabinett unter Ministerpräsident Władysław Wróblewski im Amt verblieben, amtierten einige Tage lang zwei Regierungen nebeneinander. Nachdem jedoch am 11. November 1918 der kurz zuvor aus deutscher Haft entlassene Józef Piłsudski in Warschau eingetroffen war und die polnische Republik ausgerufen hatte, übertrugen ihm sowohl die Regierung in Warschau als auch die Gegenregierung in Lublin die Regierungsgewalt. Die deutschen Truppen in der Hauptstadt, die sich geweigert hatten, auf polnische Aufständische zu schießen, wurden entwaffnet, und als der Regentschaftsrat am 14. November endgültig alle Staatsgewalt in die Hände Piłsudskis legte, wurde auch der abschließende Akt besiegelt: Das Regentschaftskönigreich Polen, die vierte und letzte Monarchie auf polnischem Boden, hatte aufgehört zu existieren.

Wolfgang Reith

00:05 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, pologne, europe centrale, première guerre mondiale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 15 novembre 2013

Historical Reflections on the Notion of “World War”

Robert Steuckers:

Historical Reflections on the Notion of “World War”

First thesis in this paper is: a World War was started in 1756, during the “Seven Years’ War” or “Austrian Succession War” and has lasted till now. We still experiment the effects of this 1756 World War and present-day events are far results of the scheme inaugurated during that remoted 18th century era.

Of course, it’s impossible to ignore all the dramatic events of the 17th century, which lead to the situation of the mid-18th century, but it would make this short paper too exhaustive. Even if Britain could already master the Western Mediterranean by controling Gibraltar and the Balears Isles after the “Spanish Succession War”, many British historians are anyway aware nowadays that British unmistakeable supremacy was born immediately after the “Seven Years’ War” and that seapower became the most determining factor for global superiority since then. Also it would be silly to forget about a certain globalization of conflicts in the 16th century: Pizzaro conquered the Inca Empire and stole its gold to finance Charles V’s war against the Ottomans in Northern Africa, while the Portuguese were invading the shores of the Indian Ocean, beating the Mameluks’ fleet in front of the Gujarat’s coasts and waging war against the Yemenite and Somali allies of the Turks in Abyssinia. The Spaniards, established in the Philippines, fought successfully against the Chinese pirates, who wanted to disturb Spanish trade in the Pacific. Ivan IV the Terrible by conquering the Volga basin till the Caspian made the first steps in the direction of the Russian conquest of Northern Asia. The war between Christianity (as defined by Emperor Charles V and Philipp II of Spain) and the Muslims was indeed a World War but not yet fully coordinated as it would always be the case after 1759.

For the British historian Frank McLynn, the British could beat their main French enemy in 1759 —the fourth year of the “Seven Years’ War”— on four continents and achieve absolute mastery of the seas. Seapower and sea warfare means automatically that all main wars become world wars, due to the technically possible ubiquity of vessels and the necessity to protect sea routes to Europe (or to any other place in the world), to transport all kind of materials and to support operating troops on the continental theatre. In India the Moghul Empire was replaced by British rule that introduced the harsh discipline of incipient industrialism to a traditional non hectic society and let the derelict Indian masses —of which one-third perished during a famine in 1769— produce huge bulks of cheap goods to submerge the European markets, preventing for many decades the emerging of a genuine large-scale industry in the main kingdoms of continental Europe. While France was tied up in a ruinous war in Europe, the British Prime Minister Pitt could invest a considerable amount of money in the North American war and defeat the French in Canada, taking the main strategical bases along the Saint-Lawrence river and conquering the Great Lakes region, leaving a giant but isolated Louisiana to the French. From 1759 on, Britain as a seapower could definitively control the Northern Atlantic Ocean and the Indian Ocean, even if the French could take revenge by building a new efficient and modern fleet in the 1770s anyway without regaining full global power.

The Treaty of Paris of 1763 marked the end of French domination in India and Canada, a situation that didn’t preoccupy Louis XV and his mistress Madame de Pompadour but puzzled the King’s successor, the future Louis XVI, who is generally considered as a weak monarch only interested in making slots. This is pure propaganda propagated by the British, the French revolutionaries and the modern trends in political thought. Louis XVI was deeply interested in seapower and sea exploration, exactly as the Russian were when they sent Captain Spangberg who explored the Kurils and the main Northern Japanese island of Hokkaido in 1738 and some years or decades later when they sent brilliant sailors and captains around the world such as Bering and his Lieutenant Tshirikov —who was the first officer to hoist the Russian imperial flag on the Pacific coast of Northern America— and Admiral von Krusenstern (who claimed the Hawai Islands for Russia), Fabian Gottlieb Bellingshausen (who circumnavigated the Antarctic for the first time in mankind’s history) and Otto von Kotzebue (who explored Micronesia and Polynesia), working in coordination with land explorers such as Aleksandr Baranov who founded twenty-four naval and fishing posts from the Kamtshatka peninsula to California. If the constant and precious work of these sea and land explorers would have been carried on ceaselessly, the Pacific would have become a Russian lake. But fur trade as a single practiced economical activity was not enough to establish a Russian New World empire directly linked to the Russian possessions in East Siberia, even if Tsar Aleksandr I was —exactly as Louis XVI was for France— in favour of Pacific expension. Tsar Nikolai I, as a strict follower of the ultraconservative principles of Metternich’s diplomacy, refused all cooperation with revolutionary Mexico that had rebelled against Spain, a country protected by the Holy Alliance, which refused of course all modifications in political regimes in name of a too uncompromising traditional continuity.

Louis XVI, after having inherited the crown, started immediately to prepare revenge in order to nullify the humiliating clauses of the 1763 Paris Treaty. Ministers Choiseul and Praslin modernized the dockyards, proposed a better scientific training of the naval officers and favoured explorations under the leading of able captains like Kerguelen and Bougainville. On the diplomatic level, they imposed the Spanish alliance in order to have two fleets totalizing more vessels than the British fleet, especially if they could table on the Dutch as a third potential ally. The aim was to build a complete Western European alliance against British supremacy, while Russia as another latent ally in the East was trying to concentrate its efforts to control the Black Sea, the Eastern Mediterranean and the Northern Pacific. This was a genuine, efficient and pragmatical Eurasianism avant la lettre! The efforts of the French, Spaniards and Dutch contributed to the American revolt and independance, as the colonists of the thirteen British colonies on the East Coast of the present-day US-territory were crushed under a terrible fiscality coined by non-elected officials to finance the English war effort. It is a paradox of modern history that traditional powers like France and Spain contributed to the birth of the most anti-traditional power that ever existed in mankind’s history. But modernity is born out the simple existence of a worldwide thalassocracy. The power which detains seapower (or thalassocracy) is ipso facto the bearer of modern dissolution as naval systems are not bound to Earth, where men live, have always lived and created the continuities of living history.

Pitt ,who was governing England at that time, could not tolerate the constant challenge of the French-Spanish-Dutch alliance, that forced Britain to dedicate huge budgets to cope with the united will of the challenging Western European powers. This lethal alliance had to be broken or the civil peace within the enemies’ borders reduced to nothing in order to paralyze all fruitful foreign policies. French historians such as Olivier Blanc put the hypothesis that the riots of the French Revolution were financed by Pitt’s secret funds in order to annihilate the danger of the French numerous and efficient vessels. And indeed the fall of the French monarchy implied the decay of the French fleet: for a time, vessels were still built in the dockyards to consolidate the seapower of which Louis XVI dreamt of but as the officers were mainly noblemen, they were either dismissed or eliminated or compulsed to emigrate so that there was no enough commanding staff anymore and no able personnel that could have been easily replaced by conscription as for the regiments of the land forces. Prof. Bennichon, as a leading French historian of navies, concludes a recent study of him by saying that workers in the dockyards of Toulon weren’t paid anymore, they and their families were starving and consequently looted the wood reserves, so that the new Republican regime was totally unable to engage the British forces on sea. Moreover, the new violent and chaotic regime was unable to find allies in Europe, the Spaniards and the Dutch prefering to join their forces to the British-lead coalition. The English were then able to reduce French naval activities to coastal navigation. A British blocus of the continent could from then on be organized. On the Mediterranean stage, the French after the battle of Abukir were unable to repatriate their own troops from Egypt and after Trafalgar unable to threaten Britain’s coasts or to attempt a landing in rebelling Ireland. Napoleon didn’t believe in seapower and was finally beaten on the continent in Leipzig and Waterloo. Prof. Bennichon: “Which conclusions can we draw from the Franco-British clash (of the 18th century)? The mastery of seapower implies first of all the long term existence of a political will. If there is no political will, the successive interruptions in naval policy compels the unstable regime to repeated expensive fresh starts without being able in the end to face emergencies... Fleets cannot be created spontaneously and rapidly in the quite short time that an emergency situation lasts: they always should preexist before a conflict breaks out”. Artificially created interruptions like the French revolution and the civil disorders it stirred up at the beginning of the 1790s, as they were apparently instigated by Pitt’s services —or like the Yeltsin era in Russia in the 1990s— have as an obvious purpose to lame long term projects in the production of efficient armaments and to doom the adverse power plunged into inefficiency to yield power on the international chessboard.

The artificially created French revolution can so be perceived as a revenge for the lost battle of Yorktown in 1783, the very year Empress Catherine II of Russia had taken Crimea from the Turks. In 1783 the thalassocratic power in Britain had apparently decided to crush the French naval power by all secret and unconventional means and to control the development of Russian naval power in the Eastern Mediterranean and in the Black Sea, so that Russian seapower couldn’t trespass the limits of the Bosphorus and interfere in the Eastern Mediterranean. What concerns explicitly Russia, an anonymous document from a British government department was issued in 1791 and had as title “Russian Armament”; it sketched the strategy to adopt in order to keep the Russian fleet down, as the defeats of the French in the Mediterranean implied of course the complete British control of this sea area, so that the whole European continent could be entangled from Norway to Gibraltar and from Gilbraltar to Syria and Egypt. This brings us to the conclusion that any single largely dominating seapower is strategically compelled to meddle into other powers’ internal affairs to create civil dissension to weaken any candidate challenger. These permanent interferences —now known as “orange revolutions”— mean permanent war, so that the birth of a global seapower implies quasi automatically the emerging process of permanent global war, replacing the previous state of large numbers of local wars, that couldn’t be thoroughly globalized.

After Waterloo and the Vienna Conference, Britain had no serious challenger in Europe anymore but had now as a constant policy to try to keep all the navies in the world down. The non entirely secured mastery of the Atlantic and the Indian Oceans and the largely but not completed mastery of the Mediterranean was indeed the puzzle that British decision-makers had to solve in order to gain definitively global power. Aiming at acquiring completely this mastery will be the next needed steps. Controling already Gibraltar and Malta, trying vainly to annex to Britain Sicily and Southern Italy, the British had not a complete grasp on the Eastern Mediterranean area, that could eventually come under control of a reborn Ottoman Empire or of Russia after a possible push in direction of the Straights. The struggle for getting control overthere was thus mainly a preventive struggle against Russia and was, in fact, the plain application of the strategies settled in the anonymous text of 1791, “Russian Armament”. The Crimean War was a conflict aiming at containing Russia far northwards beyond the Turkish Straights in order that the Russian navy would never become able to bring war vessels into the Eastern Mediterranean and so to occupy Cyprus of Creta and, by fortifying these insular strong points, to block the planned shortest highway to India through a future digged canal through one of the Egyptian isthmuses. The Crimean War was therefore an wide-scale operation directly or indirectly deduced from the domination of the Indian Ocean after the French-British clash of 1756-1763 and from the gradual mastery of the Mediterranean from the Spanish Succession War to the expulsion of Napoleon’s forces out of the area, with as main obtained geostrategical asset, the taking over of Malta in 1802-1804. The mastery of this island, formerly in the hands of the Malta Knights, allowed the British and the French to benefit from an excellent rear base to send reinforcements and supplies to Crimea (or “Tavrida” as Empress Catherine II liked to call this strategic place her generals conquered in 1783).

The next step to link the Northern Atlantic Ocean to the Indian Ocean through the Mediterranean corridor was to dig the Suez Canal, what a French engineer Ferdinand de Lesseps did in 1869. The British by using the non military weapon of bank speculation bought all the shares of the private company having realised the job and managed so to get the control of the newly created waterway. In 1877 the Rumanians and the Bulgars revolted against their Turkish sovereign and were helped by Russian troops that could have reached the coasts of the Aegean Sea and controled the Marmara Sea and the Straights. The British sent weapons, military trainers and ships to protect the Turkish capital City from any possible Bulgarian invasion and occupation in exchange of an acceptance of British sovereignty on Cyprus, which was settled in 1878. The complete control of the Mediterranean corridor was acquired by this poker trick as well as the English domination on Egypt in 1882, allowing also an outright supervision of the Red Sea from Port Said till Aden (under British supervision since 1821). The completion of the dubble mastery upon the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean, that had already been acquired but was not yet fully secured, made of Britain the main and uncontested superpower on the Earth in the second half of the 19th century.

The question one should ask now is quite simple: “Is a supremacy on the Atlantic and Indian Oceans and in the Mediterranean area the key to a complete global power?”. I would answer negatively. The German geopolitician Karl Haushofer remembered in his memoirs a conversation he had with Lord Kitchener in India on the way to Japan, where the Bavarian artillery officer was due to become a military attaché. Kitchener told Haushofer and his wife that if Germany (that dominated Micronesia after Spain had sold the huge archipelago just before the disasters of the American-Spanish war of 1898) and Britain would lost control of the Pacific after any German-British war, both powers would be considerably reduced as global actors to the straight benefit of Japan and the United States. This vision Kitchener disclosed to Karl and Martha Haushofer in a private conversation in 1909 stressed the importance of dominating three oceans to become a real global unchallenged power: the Atlantic, the Pacific and the Indian Ocean. If there is no added domination of the Pacific the global superpower dominating the Atlantic, the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean, i. e. Britain at the time of Kitchener, will be inevitably challenged, risking simultaneously to change down and fall back.

In 1909, Russia had sold Alaska to the United States (1867) and had only reduced ambitions in the Yellow Sea and the Sea of Japan, especially after the disaster of Tshushima in 1905. France was present in Indochina but without being able to cut maritime routes dominated by the British. Britain had Australia and New Zeland as dominions but no strategical islands in the Middle and the Northern Pacific. The United States had developped a Pacific strategy since they became a bioceanic power after having conquered California during the Mexican-American war of 1848. The several stages of the gradual Pacific strategy elaborated by the United States were: the results of the Mexican-American War in 1848, i. e. the conquest of all their Pacific coast; the purchase of Alaska in 1867; and the events of the year 1898 when they colonized the Philippines after having waged war against Spain. Even if the Russian Doctor Schaeffer tried to make of the volcanic archipelago of Hawai a Russian protectorate in 1817, US American whale hunters used to winter in the islands so that the islands came gradually under US domination to become an actual US strong point immediately after the conquest of the formerly Spanish Philippines in 1898. But as Japan had inherited in Versailles the sovereignty on Micronesia, the clash foreseen by Lord Kitchener in 1909 didn’t happen in the Pacific between German and British forces but during the Second World War between the American and Japanese navies. In 1945, Micronesia came under American influence, so that the United States could control the entire Pacific area, the North Atlantic area and gradually the Indian Ocean, especially when they finished building a navy and airforce strong point in Diego Garcia in the very middle part of the Indian Ocean, from where they can now strike every position along the coasts of the so-called “Monsoon countries”. According to the present-day American strategist Robert Kaplan, the control of the “Monsoon lands” will be crucial in the near future, as it allows the domination of the Indian Ocean linking the Atlantic to the Pacific where US hegemony is uncontested.

Kaplan’s book on the “Monsoon area” is indeed the proof that American have inherited the British strategy in the Indian Ocean but that, contrary to the British, they also control the Pacific except perhaps the maritime routes along the Chinese coasts in the South China Sea and the Yellow Sea, that are protected by a quite efficient Chinese fleet that is steadily growing in strength and size. They nevertheless are able to disturb intensely the Chinese vital highways if Taiwan, South Korea or Vietnam are recruited into a kind of East Asian naval NATO.

What could be the answer to the challenge of a superpower that controls the three main oceans of this planet? To create a strategical thought system that would imitate the naval policy of Choiseul and Louis XVI, i. e. unite the available forces (for instance the naval forces of the BRICS-countries) and constantly build up the naval forces in order to exercice a continuous pressure on the “big navy” so that it finally risks “imperial overstretch”. Besides, it is also necessary to find other routes to the Pacific, for instance in the Arctic but we should know that if we look for such alternative routes the near North American Arctic bordering powers will be perfectly able to disturb Northern Siberian Arctic coastal navigation by displaying long range missiles along their own coast and Groenland.

History is not closed, despite the prophecies of Francis Fukuyama in the early 1990s. The main problems already spotted by Louis XVI and his brilliant captains as well as by the Russian explorers of the 18th and 19th centuries are still actual. And another main idea to remember constantly: A single World War had been started in 1756 and is not finished yet, as all the moves on the world chessboard made by the actual superpower of the time are derived from the results of the double British victory in India and Canada during the “Seven Years’ War”. Peace is impossible, is a mere and pure theoretical view as long as a single power is trying to dominate the three oceans, refusing to accept the fact that sea routes belong to all mankind.

Robert Steuckers.

(Vorst-Flotzenberg, november 2013).

Bibliography:

-

Philippe Conrad (ed.), “La puissance et la mer”, numéro spécial hors-série (n°7) de La nouvelle revue d’histoire, automne-hiver 2013.

-

Philippe Conrad, “Quand le Pacifique était un lac russe”, in “La puissance et la mer”, op. cit..

-

Philippe Bonnichon, “La rivalité navale franco-anglaise (1755-1805)”, in “La puissance et la mer”, op. cit.

-

Niall Ferguson, Empire – How Britain Made the Modern World, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 2004.

-

Richard Harding, Seapower and Naval Warfare – 1650-1830, UCL Press, London, 1999.

-

Robert Kaplan, Monsoon – The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power, Random House, New York, 2011.

-

Charles King, The Black Sea – A History, Oxford University Press, 2004.

-

Frank McLynn, 1759 – The Year Britain BecameMaster of the World, Pimlico, London, 2005.

-

Richard Overy, Atlas of 20th Century History, Collins Books, London, 2005.

-

Tom Pocock, Battle for Empire – The Very First World War – 1756-63, Caxton Editions, London, 1998.

-

Robert Steuckers, “Karl Haushofer: l’itinéraire d’un géopoliticien allemand”, sur: http://robertsteuckers.blogspot.com (juillet 2012).

00:05 Publié dans Géopolitique, Histoire, Synergies européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : robert steuckers, histoire, thalassocratie, puissance maritime, marine, thalassopolitique, géopolitique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Okinawa : la « bataille Ragnarök »

Okinawa : la « bataille Ragnarök » (1er avril – 21 juin 1945)

par Rémy VALAT

En mémoire du soldat Tsukamoto Sakuichi, mort au combat à Okinawa (1945)

塚本作一氏を偲んで

Il y a 68 ans s’est déroulée sur l’île d’Okinawa une des batailles les plus sanglantes de la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Les habitants de l’île, retournée sous la souveraineté du Japon en 1972, vivent dans le souvenir de cette bataille et subissent au quotidien les conséquences de celle-ci : présence de l’armée américaine d’occupation, à la fois fardeau financier et source de crimes sexuels, un sol miné par 2 100 tonnes d’obus encore intacts, des séquelles psychologiques et morales. En un mot, le Japon paye encore le prix de la défaite face aux forces alliées en septembre 1945.

Une île martyre…

L’île est encore occupée par un fort contingent de troupes de marine américaines, bien que 9 000 soldats vont être prochainement déplacés sur l’échiquier de la zone Pacifique, en application des accords bilatéraux nippo-américains, récemment révisés, sur le redéploiement des forces américaines stationnées à Okinawa (2006). Les États-Unis vont relocaliser une partie de leurs unités à Guam et à Darwin (Australie). Ces mouvements sont une réponse à la montée en puissance de la flotte de guerre chinoise au sud et à l’est de la Mer de Chine, flotte qui mène d’audacieuses actions de déstabilisations près des îlots dont ils revendiquent la souveraineté (les îles japonaises Senkaku). La stratégie navale chinoise aurait pour ambition de prévenir la présence de porte-avions américains, par la construction de bâtiments de la même catégorie et l’amélioration de son équipement en missiles balistiques anti-navires : la dispersion des unités américaines aurait pour objectif de multiplier les cibles potentielles et de créer une nouvelle donne stratégique. Les unités restantes (9 000 hommes environ) aurait pour zone d’intervention l’Asie du nord-est (péninsule coréenne et façade orientale de la Chine comprise), celle de Guam la zone du Pacifique ouest, et enfin, celle de Darwin, le sud de la Mer de Chine et l’Océan Indien. La présence de la 3e force expéditionnaire du corps des Marine (IIIrd Marine Expeditionary Force) (1) et d’une formation équivalente à un régiment (les 2 200 hommes du 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit) est jugé indispensable par les autorités américaines qui considèrent l’île comme une « position clé de la ligne de front (key frontline base) face à la Chine et à la Corée du Nord. Washington a aussi argué que cette nouvelle répartition faciliterait les interventions humanitaires américaines en cas de catastrophe naturelle majeure dans la zone du Pacifique, ce qui ne peut laisser le gouvernement japonais indifférent après le désastre du 11 mars 2011.

Or la population tolère de moins en moins le coût financier et la présence de l’armée américaine dans l’île, dont 10 % du territoire est affecté aux installations militaires. La soldatesque commet régulièrement des actes de délinquance et les habitants subissent les nuisances des entraînements, et aussi un certain mépris des autorités états-uniennes pour leur sécurité. 24 Osprey MV-22, appareils destinés au remplacement des hélicoptères de transport de troupes CH-46 ont été officiellement choisis pour leurs meilleures capacités techniques comparativement aux hélicoptères CH-46 (vitesse double et capacité de portage triple). Leur rayon d’action (3 900 km) permettrait une rapide projection de troupes sur la péninsule coréenne. Mais, les déficiences techniques à répétition ayant occasionné le décès des personnels embarqués (Maroc, Floride et le 5 août 2013 sur une base américaine d’Okinawa) inquiètent les habitants et autorités locales qui se sont opposés vigoureusement à leur arrivée. Les Okinawaiens font également obstacle au déménagement de la base aéronavale de Futenma (qui doit être réinstallée dans la la baie de Henoko). Cette résistance passive, qui rappelle sur la forme celui du « Mouvement d’opposition à l’extension du camp du Larzac » des années 1970 : un noyau de militants, soutenus par la population, se relaient en permanence sur le chantier pour empêcher la progression des travaux. S’ajoute à cela le fléau des viols perpétrés régulièrement et en quasi-impunité (en raison de l’extra-territorialité des polices militaires) depuis 1945 par des soldats américains (118 viols ont été commis par des GI’s entre 1972 et 2008, selon un décompte de l’association des femmes d’Okinawa contre la violence militaire, réalisé à partir de rapports de police et de la presse locale (2). Ce phénomène récurrent (deux marins américains ont été condamnés cette année par un tribunal japonais à 9 et 10 ans de prison pour le viol en octobre 2012 d’une habitante de l’île) a obligé l’état-major des marines a décrété un couvre-feu pour ses hommes.

L’actualité entretient le souvenir douloureux de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, la bataille est ancrée dans les mémoires, et aussi souvent dans les chairs. L’année dernière (le 23 juin 2012, en marge des cérémonies officielles) des contemporains de l’affrontement ont relaté leur histoire. « Maman, je suis encore venue te voir cette année », susurre une habitante de Naha, Keiko Oshiro (68 ans). Nourrisson en 1945, Oshiro ne se souvient pas du visage de sa jeune mère, Tomi, âgée de 21 ans, atteinte à l’épaule par une balle alors qu’elle l’alimentait au sein. Selon le témoignages de proches, Tomi serait décédée dans une des grottes servant d’abris et d’hôpitaux aux militaires et aux civils. Lorsque le nom de sa mère a été gravé sur l’un des murs du Mémorial en 1995, Oshiro a pu commencer à faire le deuil de cette disparition… Fumi Nakamura (79 ans), une habitante du village de Nakagusuku est également venue rendre hommage à son père, mort de la malaria dans un camp des prisonniers. Résidant à proximité d’un aérodrome militaire américain, Nakamura déclare se crisper lorsqu’elle entend le rugissement du moteur des avions…

On comprend, à la lecture des récits de ces témoins que les habitants de l’île souffrent encore des conséquences de cet épisode de leur histoire : la guerre est restée quelque part en eux. En août 2012, 40 résidents de l’île (survivants ou membres de la famille des victimes) ont décidé d’ester contre le gouvernement : ils réclament un dédommagement financier et moral (une compensation financière de 440 millions de yen et des excuses officielles) pour les souffrances endurées pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, soulevant au passage la douloureuse question de l’implication des civils dans la bataille. Cette réclamation s’insère dans un mouvement plus large de reconnaissance des excès de l’armée impériale commis à l’encontre des habitants pendant la guerre.

Okinawa est une île marquée par l’Histoire… De par sa position géostratégique, et les derniers développements dans la région le confirment, l’île reste et restera une pièce maîtresse de l’« échiquier nord-américain» dans la région, notamment en raison de l’importance militaire des îles Nansei, passage obligé pour la marine de guerre chinoise voguant vers le Pacifique. Okinawa est un « porte-avion fixe » et une base avancée de l’armée américaine faisant face au continent est-asiatique. Pour ces raisons, les États-Unis ne sont pas prêts de retirer leurs troupes d’une position aussi importante, de surcroît acquise par la mort au combat de milliers de GI’s et de marines, au cours de ce qui a probablement été la bataille la plus sanglante de la bataille du Pacifique. Bataille ayant eu également pour conséquence (même si ce n’était pas la raison première), les bombardements atomiques de Hiroshima et de Nagasaki… Position qui cependant pourrait légitimement défendue par les forces japonaises elles-mêmes, si l’article 9 de la Constitution venait enfin à être modifié et redonnerait au Japon (troisième puissance économique mondiale) sa dignité et sa place comme grande puissance à part entière. De grands espoirs sont portés sur le Premier ministre Abe Shinzô qui œuvre en ce sens dans un contexte international devenu favorable (3).

La bataille : enjeux, unités engagées, déroulement des opérations et bilan des pertes humaines

Okinawa est une bataille majeure de la guerre Asie – Pacifique : l’ « Opération Iceberg », nom de code donné à l’automne 1944 par l’état-major américain au plan d’invasion des îles Ryûkyû, est l’opération amphibie ayant mobilisé le plus de moyens humains et matériels sur le front Pacifique depuis 1941. Pour la seconde fois, l’armée impériale japonaise va défendre le sol national avec opiniâtreté et courage (Iwo Jima est tombée le26 mars). Surtout, il s’agit d’empêcher l’armée américaine de contrôler les deux bases aériennes de l’île (Yontan et Kadena), autant de facilités pour les flottes de bombardiers stratégiques d’atteindre les îles principales du Japon et sa capitale (550 km environs séparent les deux archipels). Okinawa prise, les troupes américaines pourraient y stationner en prévision de l’invasion du Japon, programmée pour le printemps 1946 (Opération DownFall).

Les troupes alliées, très majoritairement américaines (la contribution britannique et des pays du Commonwealth, plus modeste, est navale et logistique) sont appuyées par une importante marine de guerre. L’armée d’invasion (la Xe armée), de plus de 180 000 hommes ayant une expérience du feu inégale, a été subdivisée en deux corps d’armée et en unités de réserve : le IIIe corps amphibie, composé de deux divisions de marines (1re et 6e divisions); le XXIVe corps d’infanterie (7e et 96e divisions d’infanterie), et en réserve la 2e division de marines ainsi que les 27e et 77e divisions d’infanterie. Cette armée est dirigée par le général Raymond A. Spruance.

L’armée japonaise (la 32e armée, composée de deux divisions d’infanterie – 24e, 62e divisions – et d’une brigade mixte indépendante), d’un effectif avoisinant 70 000 combattants. La 62e division est une unité aguerrie ayant combattu en Chine. Ce corps principal a été renforcé par des unités à terre de la marine (9 000 hommes), des habitants des îles Ryûkyû réquisitionnés comme combattants ou comme auxiliaires du génie (39 000 individus) et des formations plus modestes composées de lycéens servant de coursiers, de miliciens ou affectés aux hôpitaux de campagne. Les forces navales sont inexistantes ou presque et les forces aériennes reposent sur les unités de Tokubetsu kôgeki-tai (特別攻撃隊), les kamikaze. Comme le firent les officiers commandant les positions de Tarawa ou d’Iwo Jima, les troupes japonaises se sont fortifiées et cantonnées dans des positions souterraines aménagées, construites le plus souvent avec les seuls outils individuels du fantassin (pelle, pioches), un éclairage sommaire et dans des conditions sanitaires pénibles d’un sous-sol volcanique (chaleur et humidité). Les soldats-ouvriers ont ainsi creusé un dense réseau de tunnels de communication et d’installations connectés entre-eux et équipés de discrets systèmes de ventilation. Cette défense a été conçu pour compenser la nette supériorité de la puissance de feu de l’armée d’invasion (aviation, marine et infanterie). D’un point de vue tactique, les fantassins japonais, outre leur valeur intrinsèque, disposent de lance-grenades à tir courbe, très utiles en défense.

L’armée japonaise (la 32e armée, composée de deux divisions d’infanterie – 24e, 62e divisions – et d’une brigade mixte indépendante), d’un effectif avoisinant 70 000 combattants. La 62e division est une unité aguerrie ayant combattu en Chine. Ce corps principal a été renforcé par des unités à terre de la marine (9 000 hommes), des habitants des îles Ryûkyû réquisitionnés comme combattants ou comme auxiliaires du génie (39 000 individus) et des formations plus modestes composées de lycéens servant de coursiers, de miliciens ou affectés aux hôpitaux de campagne. Les forces navales sont inexistantes ou presque et les forces aériennes reposent sur les unités de Tokubetsu kôgeki-tai (特別攻撃隊), les kamikaze. Comme le firent les officiers commandant les positions de Tarawa ou d’Iwo Jima, les troupes japonaises se sont fortifiées et cantonnées dans des positions souterraines aménagées, construites le plus souvent avec les seuls outils individuels du fantassin (pelle, pioches), un éclairage sommaire et dans des conditions sanitaires pénibles d’un sous-sol volcanique (chaleur et humidité). Les soldats-ouvriers ont ainsi creusé un dense réseau de tunnels de communication et d’installations connectés entre-eux et équipés de discrets systèmes de ventilation. Cette défense a été conçu pour compenser la nette supériorité de la puissance de feu de l’armée d’invasion (aviation, marine et infanterie). D’un point de vue tactique, les fantassins japonais, outre leur valeur intrinsèque, disposent de lance-grenades à tir courbe, très utiles en défense.

Avant les opérations terrestres du printemps 1945, l’île a été intensément bombardée : lors du raid du 10 octobre 1944, l’aviation stratégique américaine procède à 1 400 sorties et a lancé 600 tonnes de bombes sur les installations portuaires de Naha et les positions de l’armée. 65 000 civils périrent. Le Jour J, le principal débarquement américain (1er avril 1945) se déroule sans opposition et fait suite aux attaques des îles Kerama et des îlots de Keise prises d’assaut respectivement les 26 et 31 mars.

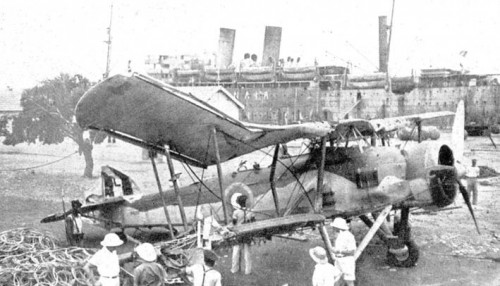

Sur mer, les unités déployées le long de la côte subissent, à partir du 6 avril, des attaques massives et répétées des unités aériennes de kamikaze : entre le 26 mars et le 30 avril, 20 bâtiments lourds sont coulés et 157 unités ont été endommagées; l’armée de l’air japonaise perd 1 100 appareils… Du début des raids massifs au 22 juin, 1 465 unités de kamikaze ont été engagées avec pour cibles privilégiées : les porte-avions. Dans le même esprit, le cuirassé Yamato (le bâtiment était escorté par 8 destroyers), lancé dans une attaque suicide contre l’U.S. Navy, est coulé par l’aviation embarquée américaine (7 avril) sans avoir pu faire le moindre dégât à la flotte de débarquement alliée. Sur une échelle stratégique générale (période du 3 mars au 16 août 1945), les forces aériennes de l’armée de terre et de la marine japonaises ont perdu 2 571 pilotes et aéronefs; la flotte américaine recense 13 navires coulés (dont 9 destroyers) et un grand nombre de navires sérieusement endommagés (9 cuirassés, 10 porte-avions, 4 croiseurs, 58 destroyerset 93 navires de différentes catégories).

Sur terre, les unités américaines ont lancé l’offensive sur deux axes après leur débarquement sur les plages de Hagushi (au nord de Naha). La partie nord de l’île est tombée assez rapidement : les aérodromes, enjeux de la bataille, ont été capturés peu après le débarquement (Kadena et Yomidan); le 21 avril, un aérodrome est rendu opérationnel sur l’île de Ie. Le 18 avril, la résistance nippone n’est plus que sporadique et locale dans cette partie de l’île.

Mais, comme à Iwo Jima, Ushijima a concentré et fortifié ses unités sur un terrain difficile et c’est dans la partie sud de l’île que va se livrer une sanglante guerre d’usure, proche des combats de la Grande Guerre en Europe. Les positions méridionales de l’île d’Okinawa ont été renforcées et les unités japonaises défendent le terrain pied à pied, avec l’énergie du désespoir et au prix de pertes humaines importantes. Le 12 avril, les unités japonaises contre-attaquent nuitamment avant d’être repoussées et récidivent le 14 avril avec un même résultat. L’offensive américaine reprend, après une relève des unités les plus marquées par l’attrition. La dernière contre-attaque japonaise, le 4 mai, échoue également : mise à découvert, l’artillerie mise en batterie pour appuyer l’assaut a été partiellement anéantie par les canons lourds américains. En juin, sous une pluie continuelle (le phénomène de « mousson japonais », le « tsuyu »), la bataille fait rage autour de la position dite du « Shuri Castle »; celle-ci tombée, la 32e armée se replie, fin mai, encore plus au sud et se positionne sur sa dernière ligne de défense, dans la péninsule de Kiyan. Le dernier carré japonais (environ 40 000 hommes) se bat avec l’énergie du désespoir : face à l’attaque de la 6e division de marines, 4 000 marins japonais (dont l’amiral Minoru Ota) se suicident dans les constructions souterraines leur servant de quartier-général (13 juin).

Le 21 juin se livrent les derniers combats d’importance : les généraux Ushijima et Chô se donnent la mort par éventration dans leurs quartiers généraux de la cote 89. Jusqu’en août 1945, des éléments isolés poursuivaient encore le combat contre l’armée américaine en différents points de l’île.

Les pertes humaines sont sans précédent sur le front du Pacifique : l’armée américaine déplore 62 000 hommes mis hors de combat (dont 12 500 tués ou portés disparus), à titre de comparaison 58 000 GI’s trouveront la mort au Vietnam entre 1967 et 1973… L’armée japonaise déplore 95 000 morts au combat ou s’étant donné la mort par seppuku ou à l’aide d’une grenade à main (voir l’épisode poignant du film de Clint Eastwood, Letters from Iwo Jima, montrant la mort de soldats japonais selon ce procédé). 7 400 soldats japonais ont été faits prisonniers. Les pertes humaines au sein de la population civile sont estimées être entre 42 000 et 150 000 tués; mais les statistiques officielles de l’armée américaine – qui prennent en considération les civils réquisitionnés – avancent le chiffre de 142 058 victimes (soit ? de la population).

Suicides volontaires ou sacrifice programmé ? Un phénomène d’implication totale de l’individu impliquant les militaires…

La bataille d’Okinawa frappe encore les imaginations par les suicides de masse de combattants et de civils, mais aussi par la détermination des combattants (attaques nocturnes au corps-à-corps, collision volontaire de pilotes kamikaze sur les bâtiments de la flotte américaine, flottilles de bateaux suicides, sortie du cuirassé Yamato).

L’histoire des kamikaze a fait coulé beaucoup d’encre. Les morts volontaires de pilotes japonais (et américains) dans le Pacifique étaient avant cela des actes héroïques et isolés, d’hommes aux commandes d’un engin sérieusement endommagé et se trouvant dans une situation sans issue. Dès 1942, des pilotes japonais se sacrifient dans de semblables situations et l’idée d’attaques suicides massives chemine dans les esprits en raison du renversement de la situation militaire. La 201e escadrille est la première formation de volontaires a avoir été formée dans ce but et engagée pendant la bataille de Leyte (la première mission se déroule le 25 octobre 1944). Selon Raymond Lamont-Brown, les pilotes auraient eu différents profils à différents moments de leur implication dans la guerre; des profils qui auraient évolués dans le temps. Dans un premier temps se seraient engagés uniquement des volontaires, patriotes fervents, romantiques et inspirés par l’esprit de la chevalerie japonaise : ce sont eux qui instituent les pratiques et les rituels attribués aux kamikaze (écriture de testaments et de poèmes, port d’attributs patriotiques et faisant référence à l’esprit guerrier japonais, la consommation de la dernière coupe de saké, etc.). Les générations suivantes de volontaires auraient eu des motivations plus « rationnelles » : ces jeunes hommes sont souvent des étudiants dont la formation a été interrompue par la guerre ou plus généralement des individus ayant reçu une excellente éducation (85 % étaient lycéens ou étudiants). La lettre de Sasaki Hachirô ci-dessus témoigne d’une grande maturité, mais aussi et surtout d’une forme de résignation : on se sacrifie par devoir, par nécessité… À l’extrême fin de la guerre, toujours selon Raymond Lamont-Brown, d’autres jeunes pilotes auraient été recrutés parmi les délinquants ou des personnes dont le comportement les mettaient en marge de la société. Il est difficile de prendre pour argent comptant une telle catégorisation, mais il est probable qu’il y ait eu une « dépréciation » de la qualité morales des pilotes (des volontaires éduqués aux exclus de la société) en raison du manque de candidats à la mort… La jeunesse (17 ans pour certains) et le niveau d’éducation élevé des kamikaze montre la volonté consciente ou non des autorités militaires à priver la nation d’un futur… Il témoigne aussi peut-être d’une forte intériorisation des valeurs patriotiques apprises, notamment (mais pas seulement) en milieu scolaire. Pendant la bataille d’Okinawa les pilotes étaient aux commandes de chasseurs de combats ou de bombardiers-torpilles (ohka). Ils ont été engagés dans 10 raids majeurs contre la flotte américaine (6 avril – 2 juin 1945). Sur mer, des navires-torpilles, basés dans l’île de Kerama, n’ont pu être engagés et ont été détruits dans leurs installations par les soldats de la 77e division américaine et le cuirassé Yamato, nous l’avons vu, a été coulé avec 4 destroyers de son escorte.

Enfin, sur terre, l’armée impériale se livre à des attaques nocturnes ayant pour objectif d’engager l’ennemi en limitant les effets ravageurs de sa puissance de feu. On constate pendant la bataille que, comme pendant la Grande Guerre, l’usage d’une puissance de feu considérable ne peut empêcher la confrontation directe et rapprochée des infanteries ennemies. Celle-ci est souvent d’une brutalité multipliée, parce que fondée sur la recherche du corps-à-corps en réponse à la volonté d’annihilation par les armes de destructions massives (exemple des Stosstruppen de la Première Guerre mondiale). Le soldat japonais s’est bâti une solide réputation de combattant résolu autant pour cette raison que pour sa valeur intrinsèque. Toutefois, la détermination des soldats nippons est une composante de la stratégie des armées alliées qui a pris en considération ce « facteur ». Le maréchal William Slim, commandant des forces alliées en Inde aurait déclaré : « Tout le monde parle de se battre jusqu’au dernier homme, mais actuellement seuls les Japonais le font ». Si les « charges banzai » ont eu un impact moral sur les combattants alliés, les moteurs psychologiques de celles-ci sont plus complexes qu’il n’y parait. Dans son ouvrage, Joanna Bourke (4) souligne l’importance de l’action de « tuer ». Sans minorer l’importance des facteurs et effets psychologiques collectifs (camaraderie, propagande, diabolisation de l’ennemi) et individuels, essentiellement la peur de la mort, cette étude apporte un éclairage significatif l’« intimité » de l’homicide en temps de guerre, la mort donnée au contact de l’ennemi. Les représentations de l’acte de tuer, bâtie souvent sur une éducation, une vision romantique de la guerre ou instrumentalisée par la propagande, tiennent une place importante; et bien souvent l’attaque à la baïonnette ou à l’arme blanche, est considérée être la plus virile et prend une dimension mythique (au Japon le « mythe du samurai »), que renforce le « culte de l’offensive » prôné par l’état-major (qui rappelle la doctrine française des premiers mois de la Grande Guerre). L’entraînement et la discipline (très difficiles dans l’armée impériale japonaise) stimulent le sentiment d’agressivité tout en se mariant aux représentations positives (le mythe du guerrier/« nous ») et négatives (dévalorisation de l’ennemi/« eux ») : l’accent est mis sur les comportements instinctifs et les pulsions primales. Ces facteurs « théoriques » prennent une ampleur plus importante avec l’enchaînement des violences et le sentiment de livrer un combat désespéré. Ces facteurs sont des pistes utiles à la compréhension des moteurs psychologiques externes et généraux sous-jacents aux attaques suicides, conduites dans un contexte militaire ayant pour horizon la défaite.

Le suicide individuel ou collectif à la grenade était une pratique de l’armée impériale en campagne, souvent le fait de soldats épuisés, grièvement blessés et d’aucune « utilité » militaire. Le sergent Nishiji Yasumasa, décrit une scène de mort collective dans la jungle birmane :« Il arrivait souvent que les soldats prennent leur propres vies par paires. Ils s’étreignaient et plaçaient une grenade entre eux. Nous appelions cela un suicide double. »

Les officiers supérieurs pratiquaient généralement l’éventration au sabre (exemple sus-mentionné des généraux Ushijima et Chô) ou livraient le dernier combat avec leurs hommes.

Les modes opératoires pourraient être divisés en deux catégories : celui du combattant en pleine potentialité (et correspondant aux normes admises par le groupe) et les autres. Les premiers se donnent la mort avec « noblesse » (seppuku, suicide des pilotes kamikaze) ou au combat avec des armes nobles et viriles (arme blanche, baïonnette); un combat visant au corps-à-corps. Concernant les pilotes d’avion, il pourrait s’agir ici d’une importation des valeurs martiales occidentales qui assimile le combat aérien à un duel chevaleresque (constatations de Joanna Bourke). Que se soit l’arme blanche ou les commandes d’un avion, l’« arme » (avion, sabre, baïonnette) est un prolongement de la main de l’homme : la mort est donnée par la volonté et l’aptitude du combattant à tuer. Il s’agit d’un acte jugé authentique. Les armes de projection (fusils, fusils-mitrailleurs, mitrailleuses, etc.) ou projetées (grenade à main) sont moins valorisantes (parce que utilisées à distance par un tireur susceptible d’atteindre sa cible à l’insu de celle-ci), c’est pourquoi, elles sont utilisées par les combattants ne se trouvant plus en mesure de se battre. Il y a peut-être, au regard de ces constatations, une dimension culturelle et symbolique dans ces actes. Une dimension que nous replacerons dans un contexte général, en infra.

Il est surtout intéressant de constater le phénomène de contagion de la pratique et des méthodes suicidaires des militaires aux civils.

… Et, par contagion, les populations civiles

C’est surtout l’implication directe des civils dans la bataille, phénomène majeur de la Seconde Guerre mondiale (et déjà constaté pendant la Grande Guerre) qui marque encore les esprits, même si en cela la bataille d’Okinawa ne constitue pas un précédent : celle de Saipan (15 juin – 9 juillet 1944), la préfigurait déjà. Pourquoi ? Parce que la prise de cette île signifiait le bombardement régulier du sol national… Le général Saito n’a fait aucune distinction entre civils et militaires dans les derniers moments de la bataille (préconisant que les premiers s’arment de lances en bambou) qui s’est conclue par une attaque suicide de grande ampleur. Dans le cas de la bataille de Saipan également, des civils se sont jetés du haut de falaises…

À la différence de la population d’Iwo Jima, qui a été évacuée sur l’ordre du général Kuribayashi, les habitants d’Okinawa ont dû rester sur place et ont été mobilisés pour des travaux de terrassement et comme combattants. D’ailleurs une population aussi nombreuse aurait-elle pu être déplacée, compte tenu de l’état de délabrement de la flotte japonaise, après plus de trois années de guerre dans le Pacifique ?

La population a souffert des excès de militaires (confiscation de nourriture, exécution d’habitants soupçonnés d’espionnage en raison de la différence de leur dialecte) et des conditions sanitaires. Si une frontière perméable exista entre le statut de civil et de combattant (Jean-Louis Margolin les qualifient de « civils militarisés »), c’était autant pour des motifs opérationnels qu’idéologiques (une nation unie contre l’envahisseur) : les habitants de l’île sont des auxiliaires précieux en raison de leur connaissance du terrain, mais aussi, pratique peu honorable, comme chair à canons : si des soldats porteurs d’une charge d’explosif ont pu se faire passer pour des civils pour commettre des attaques suicides, les civils étaient souvent utilisés pour cette mission ou comme boucliers humains pour couvrir une attaque… Sur l’île d’Ie, des femmes armées de lances se sont opposées aux troupes américaines. Ailleurs, des collégiens ont été enrôlés dès l’âge de 13 ans et divisés en escouades, souvent armés de sabres, voire d’explosifs : leur mission dans ce cas était de se précipiter sur les chars américains ou d’aller au contact de l’ennemi. Imamine Yasunabu témoigne : « Il y eut un cas où le groupe avec qui j’étais aperçut 40 ou 50 militaires américains à peu près à 100 mètres. Nous priâmes notre professeur de nous permettre d’ouvrir le feu. À ce moment, nous disposions de fusils. Il refusa, et l’ennemi finit par disparaître sans que nous ayons eu une chance d’agir. Je fus à cette époque stupéfait du comportement du professeur. Maintenant, je le comprends. Il réalisait que le Japon était en train de perdre, et il ne voulait pas sacrifier ses élèves. Nous n’avions que 6 balles chacun. Si nous avions ouvert le feu, les Américains, bien équipés, nous auraient aisément anéantis. »

La similitude des décisions et du comportement des officiers supérieurs à l’endroit des populations civiles à Saipan et à Okinawa laissent supposer la possible existence de directives de l’état-major général à l’endroit des populations civiles (ce qui a été partiellement admis par le ministère de l’ Éducation japonais en 2006), mais il ne fait aucun doute que celles-ci étaient considérées comme des « combattants ».

Enfin, sur ordre de l’armée, les habitants auraient été incités ou contraints de se suicider sur le modèle des militaires. Les suicides se sont produits par vagues, tout au long de la bataille : la première a eu lieue au moment du débarquement, voire dans certains cas, avant celui-ci, par crainte des représailles et des exactions américaines. Les circonstances ont été décrites par l’historien Jean-Louis Margolin : les responsables, civils ou militaires, organisèrent des regroupements communautaires (familles, voisins); les participants après un toast d’adieu se donnaient la mort (une personne dégoupillait une grenade au milieu d’un petit groupe de participants). Des témoins auraient assistés à des scènes d’horreur entre membres d’une même famille : assassinat à l’arme blanche, matraquages à mort, lapidations…

Komine Masao (77 ans en 2007), un survivant des suicides compulsifs de l’île de Tokashiki, raconte (propos recueillis par Kamata Satoshi, le narrateur dans l’extrait qui suit) :« Monsieur Komine m’a montré une grotte d’évacuation [des populations] construite à flanc de colline. Il avait 15 ans au moment de la bataille, et avec l’aide de son jeune frère (qui avait atteint le premier grade [sic]), il l’a creusé pour que sa famille puisse y trouver refuge. La cavité était large de 3 mètres et profonde de 10 mètres. À l’intérieur, Masao, sa grand-mère , tantes et autres parents y ont trouvé refuge des attaques aériennes et des tirs de l’artillerie de marine, mais le 28 mars, le jour suivant le débarquement américain dans l’île, ils se rendirent à Nishiyama, désigné comme un “ point de rassemblement ”. Ce jour-là, des grenades ont été distribuées aux personnes réunies. Massao et ses parents s’assirent en cercle. Sa mère et sa sœur, qui étaient allées chercher du ravitaillement, à leur retour se joignirent au cercle. Sa mère étreignit ses enfants comme s’ils étaient deux jeunes oisillons. Alors le cercle de chaque famille se resserra, se pressant les uns contre les autres et les grenades détonnèrent. Des explosions assourdissantes se firent écho et les gens crièrent. À cet instant, un feu de mortier américain s’abattit sur eux. Comme il était un enfant, Masao n’a pas reçu de grenade, mais le milicien (“ local defense soldier ” dans le texte, ou bôeitai) près de lui en avait une et elle explosa. Sur le sol gisaient des gens recouverts de sang. Les corps allongés les uns sur les autres. Ce jour-là, 315 personnes moururent sur l’île de Tokashiki, soit le tiers de la population du village de Awaren. Les personnes en familles qui ne parvinrent pas à faire exploser leurs grenades s’entre-tuèrent à la faucille ou au rasoir, en se frappant avec des battes ou des rochers ou s’étranglèrent avec des cordes…Ceux qui encore en vie se pendirent eux-mêmes ».

Dans d’autres cas, les militaires accompagnent en les contraignant peut-être les civils dans la mort, comme en témoigne notamment le récit de Frank Barron, combattant de la 77e division d’infanterie. L’action se déroule à Kerama Retto, le 26 mars 1944 : « Comme nous atteignions le sommet du premier repli de terrain, j’ai réalisé que les fantassins autour de moi étaient pétrifiés. Aussitôt mon attention a été attiré par un groupe de civils. Sur notre droite, sur le rebord du précipice, une jeune femme portant un nourrisson dans ses bras, avec derrière elle, une autre jeune femme, précédée d’un enfant de 2 ou 3 ans. Elles étaient à 30 ou 40 pieds de moi, toutes les deux nous regardant fixement comme de petits animaux apeurés. À cet instant, apparu la tête d’un homme derrière les épaules de la femme (sic). Je n’ai pu seulement voir que sa tête et son cou, mais il avait un collet d’uniforme. Si cet homme a une arme, à savoir une grenade, nous serions réellement en situation périlleuse, à moins que nous n’ouvrions le feu et tuions l’ensemble des individus se trouvant sur cette colline. J’ai fait signe à l’homme de s’approcher de moi, tandis que je me déplaçai de quelques pas pour voir si il avait quelque chose à aux mains. En un instant, ils étaient tous évanouis. Si j’avais fait quelques pas de plus, j’aurais pu voir leurs corps rebondir le long de la paroi jalonnant leur chute. »

Ailleurs, les suicides en masse se firent avec de la mort-au-rat, quand les grenades vinrent à manquer (île de Zamami, en ce lieu 358 civils trouvèrent la mort). Il y eu des cas, où des officiers poussèrent la population au suicide, puis se rendirent aux troupes américaines (îles de Tokashiki et de Zamami).

Cet ensemble de témoignages illustre le contexte d’extrême tension nerveuse dans laquelle se trouvait les habitants. Si il est impossible de connaître les mobiles exacts des personnes à s’entre-tuer ou à commettre l’acte suprême d’autodestruction. Les actes perpétrés par les uns et les autres sont révélateurs d’un contexte : il existe probablement une étude sur ces questions, mais pour saisir ces mécanismes, je renvoie à la lecture du livre d’Alain Corbin (Le village des cannibales), une analyse du massacre d’Hautefaye en 1870.

En définitive, cette tactique délibérée ou non a eu pour effet de raidir l’affrontement : les soldats américains préférant souvent ouvrir le feu, et même sur des enfants, que d’être victimes d’une potentielle attaque suicide.

Okinawa : une « bataille Ragnarök » dans une guerre totale ?

Nous pourrions qualifier l’affrontement d’Okinawa de « bataille Ragnarök », une bataille ultime, eschatologique (nous signalons au passage que cette dimension n’apparaît pas dans la mythologie japonaise). Pourquoi ?

Tout d’abord parce qu’elle se déroule sur le sol national, comme à Iwo Jima. Il ne s’agit plus d’îles lointaines comme auparavant. Nous sommes dans le contexte des bombardements de Tôkyô, celui de la nuit du 9 au 10 mars (20 jours avant l’attaque générale sur Okinawa), surpasse en victimes et en intensité celui de Dresde (100 000 victimes de bombes incendiaires lancées de manière à provoquer un maximum de dégâts sur la population et leurs habitations, 30 km2 de surface urbaines ont été détruits). En cette fin de conflit (commencé en 1937), la violence devient quasi-paroxystique et le nombre des pertes humaines augmente sensiblement (186 000 combattants jusqu’en 1941, puis 2 millions, dont 400 000 civils entre 1942 et 1945).

Les officiers supérieurs (et probablement une large partie de la population) ont conscience de livrer une bataille perdue d’avance… Le capitaine Koichi Itoh a déclaré, lorsqu’il a été interrogé sur ces événements plusieurs années après : « Je n’ai jamais envisagé, après le commencement de la guerre, que nous puissions la gagner. Mais après la chute de Saipan, je me suis résolu à admettre que nous l’avions perdue. »

Quelque puisse être le mobile, l’honneur, la défense de la patrie, différer l’invasion américaine, etc., la guerre est perdue et l’on redoute la ire du vainqueur (le sentiment de peur est entretenu par la propagande) et peut-être la fin d’une vision du Japon.

À cela s’ajoute des facteurs internes, tout d’abord le rôle de la propagande. Si cette dernière a pu être intériorisée par les combattants japonais (et en particulier sur les officiers) et peut-être les plus jeunes habitants d’Okinawa, son impact est difficile à déterminer, mais les acteurs ont dû se positionner par rapport à elle. De la lucide méfiance (dans sa lettre Sasaki Hachirô qualifie de « litanies creuses » les discours des « chefs militaires ») à l’adhésion sincère et naïve (dans son journal personnel un jeune habitant d’Okinawa de 16 ans qualifie les Américains de « Bêtes démoniaques », plusieurs passages du texte répète son patriotisme et son attachement au Japon au point de donner sa vie), la palette des motivations a pu varier dans le temps. Les femmes et les enfants qui se donnent la mort « à chaud » dans la bataille n’ont probablement pas suivi le même « raisonnement » qu’un pilote de kamikaze qui « à froid » décide de se porter volontaire pour une mission sans retour.

Ces suicides marquent aussi un refus de la réalité, de la défaite et de ses possibles conséquences. D’autant et bien qu’occulté par l’ampleur du nombre des suicides parmi les civils, il apparaîtrait aujourd’hui que, comme sur le sol français (et à une échelle moins importante que l’armée russe en Allemagne au printemps 1945), des soldats américains aient violé des habitantes de l’île (peut-être 10 000 cas).

Cette bataille (par un phénomène déjà constaté dans d’autres engagements nippo-américains dans le Pacifique et en particulier à Saipan) prend une dimension symbolique : le Japon offre la valeur (et les valeurs traditionnelles) de ses combattants aux moyensimpersonnels et techniques de l’armée américaine… Cette interprétation paraît résulter autant d’une décision pragmatique sur le champ de bataille que d’une interprétation dépréciative sur la combativité du soldat américain. L’exemple des femmes armées de lance (à l’instar des « fédérés » de la Révolution française, mais aussi parce que les armes longues sont généralement l’apanage des femmes au Japon, par exemple le naginata) symbolise l’engagement total d’un peuple (les femmes étant généralement tenues éloignées du métier des armes) pour défendre son sol, teintés de la part de quelques officiers d’une forme de mépris de la vie humaine. La dimension symbolique se retrouve peut-être également dans les suicides de mères et de leurs enfants du haut des falaises d’Itoman, peut-être un répétition involontaire et inconsciente du sacrifice du jeune empereur Antoku, précipité dans les flots par sa grand-mère Nii qui l’accompagne dans la mort lorsque la bataille navale de Dan-no-Ura (1185) a été perdue pour le clan Taira (face aux Minamoto qui instaureront le premier shôgunat).

Si ces facteurs ont motivés les suicides compulsifs (coercition des militaires, propagande et l’éducation données aux jeunes habitants de l’île dans le cadre d’une politique d’assimilation), on recherche aussi échapper à l’ennemi et la mort paraît être le seul refuge, comme pour les défenseurs de Massada… On redoute la culpabilité et l’infamie pour avoir préféré le déshonneur de vivre et d’endosser une partie de la responsabilité de la défaite… On retrouve un écho de cet état d’esprit (notamment dans la littérature et les mangas) dans la jeune génération n’ayant pas pris les armes de l’après-guerre… Les arguments culturels ont été avancés, le code de l’honneur du « bushidô » (en réalité une construction intellectuelle à destination des Occidentaux) notamment… Mais que penser de la lettre de Ichizu Hayashi, pilote de confession chrétienne ? On se rend bien compte qu’il est quasi-impossible de comprendre totalement le phénomène.

En 1944, le Japon était entré, selon l’expression de Maurice Pinguet, dans l’« engrenage du sacrifice » : « Dans la guerre du Pacifique, l’armée japonaise avait mis son existence en jeu, la défaite serait sa mort – ce serait donc aussi la mort du Japon : elle s’identifiait trop étroitement à la nation pour imaginer une autre conclusion. » Cela, je pense, résume bien ce qui s’est déroulé à Okinawa à une échelle ayant atteint quasiment son paroxysme.

Rémy Valat

Notes

1 : L’accord initial prévoyait, selon une source rendue disponible par la marine américaine en 2009, le départ de l’état-major du IIIrd M.E.F. pour Guam. Cette structure est un élément singulier des forces américaines outre-mers : elle est dirigé par un lieutenant-général qui commande les forces américaines sur l’île et sert de coordinateur pour la « zone d’Okinawa ».

2 : Cf. http://japon.aujourdhuilemonde.com/au-japoncontre-les-viols-des-soldats-americains-les-femmes-lancent-un-cri-dalarme

3 : Le 28 août dernier, le ministre de la Défense japonais, Itsunori Onodera et le secrétaire d’État à la Défense nord-américain, Chuck Hagel, ont entamé une discussion en faveur d’une possibilité pour les forces aériennes d’autodéfense japonaise d’effectuer des frappes préventives sur des bases ennemies (c’est-à-dire contre la Corée du Nord).

4 : Joanna Bourke, Intimate Story of Killing. Face-to-Face Killing in Twentieth-Century Warfare, Londres, Granta, 1999. Cette étude aborde aussi la guerre du Pacifique, bien que centrée sur la Première Guerre mondiale.

Bibliographie

• Astor Gerald, Operation Iceberg. The invasion and conquest of Okinawa in World War II, World War II Library, 1995.

• Daily Yomiuri (The), 24 juin et 16 août 2012.

• Kakehashi Kumiko, Lettres d’Iwo Jima. La plus violente bataille du Pacifique racontée par les soldats japonais, Les Arènes, 2011.

• Lamont-Brown Raymond, Kamikaze. Japan’s suicide samurai, Cassell Military Paperbacks, 1997.

• Margolin Jean-Louis, Violences et crimes du Japon en guerre (1937 – 1945), Hachette, Pluriel, 2007.

• Pinguet Maurice, La mort volontaire au Japon, Tel – Gallimard, 1984.

• Rabson Steve, The Politics of Trauma. Compulsory Suicides During the Battle of Okinawa and Postwar Retrospectives, http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue24/rabson.htm.

• U.S. Army in the World War II. The War in the Pacific. Okinawa The last battle,www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-P-Okinawa/USA-P-Okinawa.

Concernant les violences et leur dimension psychologiques en temps de guerre, voici quelques pistes de lectures :

— Alain Corbin, Le village des cannibales, Aubier, 1990.

— Christopher R. Browning, Des hommes ordinaires, le 101e bataillon de réserve de police allemande et la solution finale en Pologne, Belles Lettres, 1994, (chapitre « Des hommes ordinaires »).

— Louis Crocq, Les traumatismes de guerre, Odile Jacob, 2006.

— Jacques Sémelin, Purifier et détruire. Usages politiques des massacres et des génocides, Le Seuil, 2003.

— Rémy Valat, Les calots bleus et la bataille de Paris. Une force de police auxiliaire pendant la guerre d’Algérie, Michalon, 2007 (chapitre « Salah est mort ! Les moteurs psychologiques d’une unité en guerre »).

Article printed from Europe Maxima: http://www.europemaxima.com

URL to article: http://www.europemaxima.com/?p=3397

00:05 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : japon, asie, histoire, kamikaze, seconde guerre mondiale, okinawa, deuxième guerre mondiale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 09 novembre 2013

Wall Street & the November 1917 Bolshevik Revolution

Wall Street & the November 1917 Bolshevik Revolution

By Kerry Bolton

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

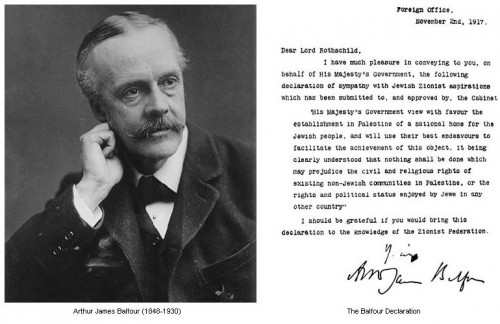

My last article [2] documented the funding of the March 1917 Revolution in Russia.[1] The primary financier of the Russian revolutionary movement 1905–1917 was Jacob Schiff, of Kuhn Loeb and Co., New York. In particular Schiff had provided the money for the distribution of revolutionary propaganda among Russians prisoners-of-war in Japan in 1905 by the American journalist George Kennan who, more than any other individual, was responsible for turning American public and official opinion against Czarist Russia. Kennan subsequently related that it was thanks to Schiff that 50,000 Russian soldiers were revolutionized and formed the cadres that laid the basis for the March 1917 Revolution and, we might add–either directly or indirectly–the consequent Bolshevik coup of November. The reaction of bankers from Wall Street and The City towards the overthrow of the Czar was enthusiastic.

This article deals with the funding of the subsequent Bolshevik coup eight months later which, as paradoxical as it might seem to those who know nothing of history other than the orthodox version, was also greeted cordially by banking circles in Wall Street and elsewhere.

Apologists for the bankers and other highly-placed individuals who supported the Bolsheviks from the earliest stages of the communist takeover, either diplomatically or financially, justify the support for this mass application of psychopathology as being motivated by patriotic sentiment, in trying to thwart German influence over the Bolsheviks and to keep Russia in the war against Germany. Because Lenin and his entourage had been able to enter Russia courtesy of the German High Command on the basis that a Bolshevik regime would withdraw Russia from the war, Wall Street capitalists explained that their patronage of the Bolsheviks was motivated by the highest ideals of pro-Allied sentiment. Hence, William Boyce Thompson in particular stated that by funding Bolshevik propaganda for distribution in Germany and Austria this would undermine the war effort of those countries, while his assistance to the Bolsheviks in Russia was designed to swing them in favor of the Allies.

These protestations of patriotic motivations ring hollow. International banking is precisely what it is called–international, or globalist as such forms of capitalism are now called. Not only have these banking forms and other forms of big business had overlapping directorships and investments for generations, but they are often related through intermarriage. While Max Warburg of the Warburg banking house in Germany advised the Kaiser and while the German Government arranged for funding and safe passage of Lenin and his entourage from Switzerland across Germany to Russia;[2] his brother Paul,[3] a partner of Jacob Schiff’s at Wall Street, looked after the family interests in New York. The primary factor that was behind the bankers’ support for the Bolsheviks whether from London,[4] New York, Stockholm,[5] or Berlin, was to open up the underdeveloped resources of Russia to the world market, just as in our own day George Soros, the money speculator, funds the so-called “color revolutions” to bring about “regime change” that facilitates the opening up of resources to global exploitation. Hence there can no longer be any doubt that international capital a plays a major role in fomenting revolutions, because Soros plays the well-known modern-day equivalent of Jacob Schiff.

Recognition of Bolsheviks Pushed by Bankers

This aim of international finance, whether centered in Germany, England or the USA, to open up Russia to capitalist exploitation by supporting the Bolsheviks, was widely commented on at the time by a diversity of well-informed sources, including Allied intelligence agencies, and of particular interest by two very different individuals, Henry Wickham Steed, editor of The London Times, and Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labor.