Survol historique de la Syrie et des Alaouites

Introduction

La prise du pouvoir par les Alaouites en Syrie marque une rupture profonde avec le passé et l’histoire. Depuis des siècles, l’aire syrienne a été gouvernée, en général depuis Damas, par une bourgeoisie commerçante musulmane sunnite des plus orthodoxes, soumise à l’Empire Ottoman, qui a su par la suite composer, non sans diverses manoeuvres, avec la puissance mandataire avant de profiter de la confusion européenne pour échapper à son emprise et tenter, de façon un peu brouillonne, plusieurs formules de partage oligarchique du pouvoir. Quoi qu’il en soit, Damas demeurait, avec Le Caire, l’un des deux grands pôles de la pensée orthodoxe arabe et musulmane. Quant aux minorités religieuses ou ethniques, Chrétiens, Druzes, Alaouites, Juifs, Kurdes, Arméniens, bien que proportionnellement les plus importantes [1] de la région, ou peut être à cause de cela, elles étaient soigneusement tenues dans un état de marginalité politique et sociale, éloignées géographiquement ou institutionnellement des centres et instruments de pouvoir.

L’erreur fondamentale de la bourgeoisie affairiste et conservatrice sunnite de Syrie est sans doute d’avoir cru que son monopole économique et financier lui garantissait sans risque le contrôle permanent d’un appareil d’État plus conçu comme un lieu d’arbitrage et de représentation que comme un réel instrument de pouvoir. L’appareil de contrainte de l’État, Armée, Police, Administration fiscale ou douanière, avait toujours été dans des mains étrangères et l’on avait bien su s’en accommoder. De fait, il n’était nullement perçu comme un instrument valorisant, facteur de promotion et de contrôle sérieux de la société civile. Les minorités ont su profiter de cette lacune politique et culturelle et, au premier rang d’entre elles, les Alaouites. Hérétiques de l’Islam, méprisés, persécutés, démunis, relégués dans leurs montagnes peu hospitalières surplombant la Méditerranée entre les frontières libanaise et turque, désignés à la vindicte depuis la fatwa d’Ibn Taymiya (1268-1328)[2], les Alaouites ne paraissaient pas les mieux placés pour se lancer à la conquête de l’État syrien. En fait ils n’ont pas eu les hésitations des Chrétiens syriens, en majorité orthodoxes, qui ne bénéficient pas comme les Maronites du Liban d’une solution de repli territorial en cas d’échec. Contrairement aux Druzes, qui sont restés fidèles à leur tradition séculaire de ne jamais se mettre en avant pour ne pas désigner la communauté aux coups, les Alaouites, malgré leur passé et leur passif, ont entrepris de profiter d’une conjoncture favorable qui laissait le pouvoir en partie vacant à l’intérieur du pays et qui, au début des années 50, relativisait le poids de l’Islam dans le monde arabe en faveur d’idéologies peu connotées sur le plan religieux (nationalisme, marxisme).

Depuis le coup d’État du 8 mars 1963, la minorité alaouite de Syrie s’est donc progressivement assuré, sous la conduite de l’un des plus discrets mais des plus déterminés de ses membres, le général Hafez el-Assad, un contrôle étroit du pouvoir, de l’appareil civil et militaire de l’État et aussi des ressources économiques et financières du pays. Cette emprise à la fois communautaire et minoritaire n’est ni revendiquée ni même avouée. Elle s’exerce derrière le paravent, parfois avec l’alibi, d’une organisation centralisée et autoritaire mais qui se proclame résolument égalitariste, moderne et progressiste. En fait, elle met en jeu, tant en Syrie même que dans son contexte régional, les ressorts complexes de stratégies et de tactiques communautaires, tribales, claniques et familiales où dominent les rapports d’obligations interpersonnelles. L’édification de ces rapports, ainsi que la sanction de leur respect ou de leur violation, détermine et rythme depuis trente ans la vie publique intérieure mais aussi la politique extérieure de la Syrie qui y gagnent en cohérence et en détermination ce qu’elles y perdent en termes d’ouverture et d’image. Il reste à savoir si cette longue marche au pouvoir de Hafez el-Assad peut conduire à l’intégration de la communauté alaouite dans le pays et dans le siècle, ou si elle porte les germes de sa dissolution et de sa destruction. Car en sortant de son isolement géographique et social pour assumer le pouvoir d’État, la communauté perd ses repères internes, gomme ses différenciations, confrontée au double besoin de faire bloc pour s’imposer à un environnement hostile et de conclure avec cet environnement des alliances permettant de rentabiliser le présent et garantir l’avenir. Elle est bouleversée en son sein par les démarches de légitimation d’élites nouvelles, dynamiques et conquérantes, bousculant les cadres traditionnels qui puisaient leur pouvoir dans une capacité à gérer des réseaux de soumission et de transaction avec un extérieur dominateur. À mesure que s’affermit, s’étend, mais aussi se disperse le pouvoir alaouite sur l’ensemble du pays, la segmentation tribale de la communauté, fondée sur un état donné d’occupation physique d’un terrain précis, s’estompe au profit d’une segmentation en clans, voire en familles, dont les réseaux de solidarités et d’alliances dépassent les limites traditionnelles internes et externes de la communauté dans un contexte d’accès au pouvoir d’État et aux rentes économiques et politiques qui y sont liées [3]. Au terme d’une histoire presque millénaire d’isolement, de soumission et de discrétion, les Alaouites sont entrés dans le siècle, mais à quel prix pour leur identité et leur devenir ?

Repères

Dès le paléolithique et le néolithique, des groupes humains peuplèrent cette région. Dans la vallée de l’Euphrate, formant avec celle du Tigre la Mésopotamie, apparurent l’agriculture, puis les premières villes, les premiers royaumes, ainsi que l’écriture cunéiforme et l’alphabet.

Syrie - Maaloula : abris-sous-roche ou habitations préhistoriques sous un surplomb rocheux.

La Syrie de l’Antiquité

Du fait qu’elle était un lieu de passage entre l’Égypte et la Mésopotamie, la Syrie fut livrée très tôt aux invasions des grandes puissances commerciales du monde de l’époque. Soumise à la domination des Sumériens, puis des Akkadiens, la région passa, à la fin du IIIemillénaire, sous l’influence des Amorites, un peuple sémite nomade. Au XIXe siècle avant notre ère, les Amorides fondèrent la première dynastie de Babylone. Hammourabi, roi de Babylone, étendit sa domination sur toute la région au siècle suivant.

À partir du XVIe siècle, l’Égypte des pharaons (la XVIIIe dynastie) prit le contrôle de la Syrie méridionale, tandis qu’au nord s’établirent les Hittites. Au carrefour commercial entre la Méditerranée et l’Asie, la région prospéra grâce à l’activité des marchands phéniciens qui fondèrent de nombreux ports (Tyr, Byblos, Sidon au Liban, Ougarit en Syrie).

L’équilibre fut rompu par l’arrivée des «Peuples de la mer» qui déferlèrent au XIIIe siècle avant notre ère et dévastèrent le littoral. Alors que les Araméens établissaient de petites principautés de la vallée de l’Oronte à celle de l’Euphrate, le royaume d’Israël étendit sa domination sur la région aux Xe et IXe siècles, en créant des liens de vassalité avec les Araméens. Le royaume de Damas fut fondé vers 1000 avant notre ère. Nabuchodonosor II, illustre représentant de la Xe dynastie de Babylone qui s’établit sur les restes de la puissance assyrienne, étendit son pouvoir jusqu’à Jérusalem; maître de l’Orient, il fit de sa langue, l’araméen, l’idiome de tous les peuples sous sa domination.

En 539, Cyrus le Grand, accueilli en libérateur par les peuples sous le joug babylonien, dévasta l’empire chaldéen. La Syrie passa sous domination perse et fut administrée par les satrapes des Grands Rois pendant les deux siècles qui suivirent. Alexandre le Grand l’annexa ensuite à son empire en 333-332 avant notre ère. Sous influence hellénistique, la Syrie échut après la mort du conquérant à Séleucos Ier Nikator, l’un de ses généraux. Une partie de la Syrie s’hellénisa au cours des siècles suivants, car le grec s’est imposé dans la région.

Par la suite, le royaume de Syrie fut envahi par les Romains de Pompée venus en Orient vaincre les Parthes; le royaume devint une province romaine en 64 avant notre ère. Mais la Syrie demeura quand même hellénisée sous la domination romaine, à tel point qu’elle devint l’une des principales provinces de l’Empire. Toutefois, après la fragmentation de l’Empire romain en 395 de notre ère, la Syrie fut intégrée à l’Empire byzantin. Elle connut une période de prospérité économique et de stabilité politique, troublée par les querelles religieuses qui déchirèrent l’Église d’Antioche. À partir de 611, les Perses tentèrent de mettre à profit les troubles religieux pour rétablir leur domination sur la région. Les Byzantins les chassèrent définitivement en 623, pour faire face à une nouvelle menace, celle de l’islam.

La Syrie arabe

Dès le IVe siècle avant notre ère, des tribus arabes venues du sud de l’Arabie s’étaient établies en Syrie. Affaiblis par les luttes qui les opposaient, Byzantins et Perses ne purent résister à l’expansion arabo-musulmane. La victoire du Yarmouk (636) sur les troupes d’Héraclius Ier permit aux Arabes de s’assurer le contrôle de la Syrie, qui s’islamisa et s’arabisa. La dynastie omeyyade (661-750), fondée par Moawiyya, exerça son rayonnement depuis Damas, la capitale. La marine du calife s’empara des îles de la Méditerranée orientale (Chypre, Crète, Rhodes), tandis que les troupes terrestres virent camper sous les murs de Constantinople. L’administration fut réorganisée, les sciences se développèrent, les mosquées et les palais se multiplièrent. Pourtant, les Omeyyades tombèrent sous les coups des Abbassides, qui firent de Bagdad la capitale de leur nouvel empire (750-1258), dont la Syrie devint une simple province. Le pays connut ensuite une période troublée lorsque l’empire commença à se démembrer.

Aux Xe et XIe siècles, le désordre qui régnait dans le pays, divisé entre des dynasties arabes et turques rivales, favorisa l’établissement des croisés occidentaux qui, après la prise d’Antioche (1098) et de Jérusalem (1099), occupèrent le littoral et le nord de l’actuelle Syrie. Les croisés édifièrent une série de châteaux forts tournés vers la mer. En 1173, Saladin, fondateur du sultanat ayyubide, mena la lutte des musulmans contre les croisés et unifia l’intérieur de la Syrie. Affaibli par la guerre opposant croisés et musulmans, le pays subit au XIIIe siècle l’invasion destructrice des Mongols. Les mamelouks, dynastie d’esclaves qui s’était imposée en Égypte, stoppèrent leur avance, expulsèrent les croisés en 1291 et dominèrent la Syrie jusqu’en 1516.

En réalité, la multiplicité des invasions étrangères s’est traduite dans le domaine religieux. Ainsi, si 90 % de la population est devenue musulmane, 10 % de celle-ci est restée chrétienne, avec le maintien de minorités chiite, druze, ismaélienne et surtout alaouite.

La Syrie ottomane

Après avoir pris Constantinople, les Ottomans vainquirent les mamelouks en 1516, annexèrent la Syrie à leur nouvel empire et divisèrent celle-ci en trois, puis en quatre pachaliks ou provinces (Damas, Tripoli, Alep et Saïda). La Syrie ottomane fut gérée au nom du sultan par des gouverneurs nommés pour un an. Cependant, la domination turque se fit principalement sentir dans les villes, les émirs locaux exerçant partout ailleurs leur propre pouvoir.

Durant quatre siècles, la Syrie redevint un carrefour commercial important et développa des relations avec le monde occidental. Puis l’affaiblissement graduel de la puissance ottomane attisa les ambitions territoriales, tantôt du premier consul Bonaparte en 1799, tantôt par les troupes du vice-roi d’Égypte Méhémet Ali en 1831. En 1860, Napoléon II intervint en Syrie afin de favoriser les chrétiens.

Puis ce fut le tour des Britanniques. Ayant gagné l’appui des Arabes syriens, les Anglais promirent l’indépendance du pays en cas de victoire sur l’Empire ottoman. Cependant, le 16 mai 1916, la Grande-Bretagne et la France conclurent des accords secrets, les accords Sykes-Picot, par lesquels les deux puissances se partageaient les terres arabes sous domination ottomane. Cet accord résulte d’un long échange de lettres entre Paul Cambon, ambassadeur de France à Londres, et sir Edward Grey, secrétaire d’État au Foreign Office; par la suite, un accord ultra-secret fut conclu à Downing Street entre sir Mark Sykes pour la Grande-Bretagne et François Georges-Picot pour la France. Cet accord équivalait à un véritable dépeçage de l’espace compris entre la mer Noire, la Méditerranée, la mer Rouge, l’océan Indien et la mer Caspienne. La région fut découpée de la façon suivante:

1) Une zone bleue française, d’administration directe (Liban et Cicilie);

2) Une zone arabe A, d’influence française (Syrie du Nord et province de Mossoul);

3) Une zone rouge anglaise, d’administration directe (Koweït et Mésopotamie);

4) Une zone arabe B, d’influence anglaise, (Syrie du Sud, Jordanie et Palestine);

5) Une zone brune, d’administration internationale comprenant Saint-Jean-d’Acre, Haiffa et Jérusalem.

Bref, la Syrie et le Liban actuels revirent à la France, l’Irak et la Palestine furent attribuées au Royaume-Uni.

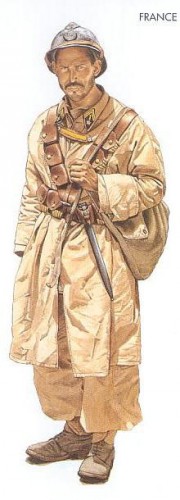

Le mandat français (1920-1941)

Les Britanniques et les Arabes participèrent à la prise de Damas en 1918. L’année suivante, les forces britanniques se retirèrent de la zone d’influence revenant à la France, cédant le contrôle aux troupes françaises. En 1920, la Société des Nations (SDN) confia à la France un mandat sur la Syrie et le Liban, lesquels devaient rapidement aboutir, du moins en théorie, à l’indépendance des deux territoires. Toutefois, les nationalistes syriens, organisés depuis la fin du XIXe siècle, espéraient la création d’une Syrie indépendante, incluant la Palestine et le Liban. En mars 1920, le Congrès national syrien (élu en 1919) refusa le mandat français et proclama unilatéralement l’indépendance du pays. Celui-ci devint une monarchie constitutionnelle dirigée par le fils de Hussein, le prince Fayçal.

Néanmoins, en avril 1920, la conférence de San Remo confirma les accords Sykes-Picot, qui légitimaient l’intervention militaire française: les troupes du général Gouraud entrèrent à Damas en juillet. Fayçal, contraint à l’exil, trouva alors refuge en Irak, où il sera couronné en 1921. Ce fut alors l’effondrement du «grand projet arabe» de rassembler autour de Damas les terres arabes autrefois placées sous contrôle ottoman. Alors qu’elle avait été hostile envers les Turcs, la population syrienne développa rapidement un sentiment antifrançais.

|

Le Mandat français sur la Syrie fut organisé en un «Grand Liban» composé de quatre provinces: l’État de Damas, l’État d’Alep, l’État des Alaouites (1920) et l’État du Djebel druze (1921), auxquels s’ajouta, en mars 1923, le sandjak d’Alexandrette (au nord) détaché d’Alep et peuplé d’une minorité turque. La même année, le général Gouraud créa la Fédération syrienne, qui regroupait Damas, Alep et l’État alaouite, sans le Djebel druze, ni Alexandrette. En 1924, l’État alaouite en fut également séparé. De 1925 à 1927, le Djebel druze entra en état d’insurrection, dirigée par le sultan Pacha-El-Atrache. Le général Sarrail y fut chargé de rétablir l’ordre français. En 1926, le «Grand Liban» devint la République libanaise. |

La frontière syro-libanaise fut tracée par les Français, protecteurs traditionnels des chrétiens dans la région, afin de satisfaire les ambitions des maronites à la création d’un «plus grand Liban». La Syrie ne reconnut jamais ce tracé. Sachant proche l’indépendance du mandat français du Levant, la Turquie fit savoir, dès 1936, qu’elle se refusait à ce que la population minoritaire turque du Sandjak d’Alexandrette puisse passer sous l’autorité syrienne indépendante. Paris, soucieux de ne pas contrarier un État dont la position revêtait une grande importance stratégique quant à la défense des intérêts français au Levant, accéda à la demande d’Ankara, et le Sandjak d’Alexandrette (ou république du Hatay) passa sous souveraineté turque le 23 juin 1939, sous le nom de «province du Hatay», au grand dam des nationalistes syriens.

Malgré son hostilité à l’égard de la France, la Syrie se rangea aux côtés des Alliés en 1939. En juin 1940, après la capitulation française, la Syrie passa sous le contrôle du gouvernement de Vichy. En 1941, les forces de la France libre et les Britanniques chassèrent le général Dentz, haut-commissaire du Levant. Le général Catroux, au nom de la France libre, reconnut officiellement l’indépendance de la Syrie, mais les troupes franco-britanniques demeurèrent sur le sol syrien. Les Français ne se retirèrent totalement du Liban et de la Syrie qu’en 1946, après avoir violemment réprimé de nouvelles émeutes nationalistes et bombardé Damas. Cette même année, la Syrie devient membre des Nations unies.

Soulignons que, lors du mandat français, les Kurdes ne firent l’objet d’aucune mesure répressive. Même s’ils ne jouissaient d’aucun statut officiel, ils pouvaient librement pratiquer leur religion et utiliser leur langue, voire diffuser leurs journaux. C’est dans le Kurdistan syrien que beaucoup d’intellectuels Kurdes persécutés en Turquie vinrent trouver refuge, bien qu’ils ne disposaient d’aucun droit politique. Les Kurdes ont bel et bien demandé leur autonomie à l’intérieur des frontières du pays. Une pétition fut adressée à l’Assemblée constituante de Syrie le 23 juin 1928 et y a inclus les trois demandes suivantes:

1) L’usage de la langue kurde dans les zones kurdes, concurremment avec d’autres langues officielles (arabe et français);

2) L’éducation en langue kurde dans ces régions;

3) Le remplacement des employés du gouvernement de ces régions par des Kurdes.

Les autorités du mandat français ne favorisèrent pas l’autonomie kurde dans cette partie de la Syrie en raison de l’intolérance manifestée par la Turquie et l’Irak à l’égard «d’un territoire autonome kurde» près de leurs frontières. En fait, l’usage du kurde était libre, sans être officielle, dans la région. Mais l’absence de matériel pédagogique en langue kurde aurait rendu l’organisation de l’éducation particulièrement difficile, bien que ce soit des considérations d’ordre politique qui ait joué.

Quant à la minorité religieuse alaouite, elle fut favorisée par les Français. Longtemps persécutés dans le passé, les alaouites (issus des chiites) purent s’instruire et se faire embaucher dans l’armée coloniale française, ce qui assura leur promotion sociale, dont les élites dirigeront ensuite le Parti Baas à partir de 1963. Les Français avaient créé le «Territoire des alaouites», qui allait devenir l’«État des Alaouites», puis en 1930 le «territoire de Lattaquié» ou «gouvernement de Lattaquié». Afin de faire contrepoids au nationalisme arabe des sunnites, les Français encouragèrent pendant l’entre-deux-guerres le particularisme alaouite, qui prétendait faire des alaouites un peuple à part entière, mais cette politique colonialiste échoua.

LES ALAOUITES

Alep

Dans les années 860, Ibn Nosayr, originaire de Bassorah et disciple du dixième imam chiite Ali al-Hadi, entre en dissidence et prêche une foi chiite extrémiste divinisant Ali [4] au sein d’une sorte de trinité dont Mahomet et son compagnon Salman sont les autres pôles. Fuyant l’Irak, les disciples de Ibn Nosayr sont récupérés par les Hamdanides de Alep qui trouvent expédient de les envoyer stimuler le zèle des tribus vivant aux marches de l’Empire Byzantin en Syrie du Nord. La prédication d’Ibn Nosayr rencontrera un succès inespéré parmi ces populations mal islamisées, encore fortement imprégnées de christianisme oriental chez qui son mysticisme, son culte du martyre et sa doctrine trinitaire provoquent des échos familiers. Il en résultera un syncrétisme mystique incorporant des éléments du chiisme le plus extrême, du christianisme byzantin et de paganisme ou de panthéisme hellénistique.

La constitution des royaumes francs, qui jouaient sur les divisions locales, a favorisé localement l’adhésion au Nosaïrisme et son implantation durable dans le nord-ouest de la Syrie, mais la répression qui a suivi la reconquête musulmane n’en a été que plus féroce. Traqués en tant que traîtres et apostats, les membres des tribus alaouitisées de Syrie se réfugient dans les montagnes surplombant Lattaquieh où elles vivent en retrait du reste du pays, tributaires d’une maigre agriculture de subsistance, en butte à de permanentes persécutions politiques et religieuses, entretenant des relations de dépendance difficile avec les villes de la côte et de l’intérieur. Cette situation, émaillée d’affrontements sporadiques et toujours sanglants avec les autorités de droit ou de fait, durera jusqu’à l’effondrement de l’Empire Ottoman. Des expéditions punitives de Baïbars vers 1360 à l’établissement du mandat français en 1920, les Alaouites se sont figés en collectivités défensives régulièrement décimées dans toutes les hauteurs de la montagne côtière qui s’étend de Tartous à Alexandrette, ne descendant dans la plaine que pour louer leurs services comme ouvriers agricoles ou vendre leurs filles comme servantes [5]. Ce régime de persécutions religieuses et sociales conduit la communauté à se réfugier, comme les Druzes, dans l’hermétisme et la dissimulation. Les secrets ultimes de la religion sont réservés à une petite classe d’initiés et l’ensemble de la communauté intègre au plus haut degré la pratique de la taqiya [6]qui peut aller jusqu’au reniement public de l’appartenance à la communauté et la reconnaissance de l’appartenance à la religion dominante. Cependant contrairement aux Druzes, les Alaouites ne refusent pas les alliances matrimoniales hors de la communauté et même les encouragent quand elles peuvent lui profiter.

On retrouve chez les Alaouites de Syrie toutes les formes les plus classiques des sociétés côtières sédentarisées de la Méditerranée. La structure de base de la communauté est la famille (ahl) au sens élargi, sur laquelle règne sans partage l’autorité patriarcale. La famille est elle-même membre d’un clan (‘ashîra) regroupant plusieurs familles alliées, qui est la véritable unité de base de la communauté en laquelle on se reconnait principalement. Ces clans informels sont, regroupés par agrégation ou seuls suivant leur importance, constitutifs d’une tribu (qabîla) dont l’existence est plus liée aux relations d’alliance et aux solidarités de voisinage qu’à la référence à un lignage attesté ou mythique commun. La sédentarité des Alaouites explique évidemment que, contrairement aux nomades, ils se réfèrent plus au sol qu’au sang et, dans la pratique courante, l’Alaouite se réfère essentiellement à son “village”, entité à la fois humaine et géographique, lieu géométrique de ses relations affectives et sécuritaires. La tribu est dominée par un sheikh “temporel” dont l’autorité ne se confond pas avec celle des chefs religieux. Enfin, la plupart des tribus alaouites sont regroupées en quatre grandes “fédérations” (ahlaf) dont la segmentation, perpendiculaire à la côte, paraît essentiellement due aux contraintes locales de la géographie physique qui conditionnent l’orientation des voies de communication et a contribué à donner des caractéristiques communes aux tribus qui les constituent [7] :

- Les Haddâdîn dans la région de Dreikish et Safita,

- Les Khayyâtîn dans la région de Qadmus et Marqab,

- Les Matawira dans la région de Matwa et Aïn Sharqiyyah,

- Les Jurûd [8] dans le triangle Qardaha-Slenfé-Alexandrette, fédération dont la tribu des Kalbiyyeh, la plus importante en nombre, est celle de Hafez el-Assad qui appartient au clan des Karahil [9].

Ces quatre fédérations regroupent environ 80% des Alaouites de Syrie, les autres se répartissant en tribus au rattachement incertain comme les Bichraghiyyah (du nom de la région de Bichragh dont ils sont les habitants, qui marque la limite entre les tribus du nord du Djebel alaouite et celles du sud aux pratiques religieuses et sociales légèrement différentes) ou en sortes de confréries à vocation plus religieuse que sociale comme les Murchidiyyin ou les Hawakhissa. D’une manière générale, la notion de tribu chez les Alaouites, agriculteurs attachés à leur terroir, apparaît donc plus liée à l’établissement de liens de solidarité et de protection réciproques entre familles élargies voisines qu’à des références communes à des ancêtres ou des passés mythiques qui sont le fondement du tribalisme nomade des pasteurs dans l’hinterland steppique [10]. Il en résulte une certaine perméabilité et un flou des contours, un caractère mouvant des critères de légitimité, une grande disponibilité aux modifications des systèmes d’alliances ou d’antagonismes.

A la tête de la communauté on trouve traditionnellement un “Conseil communautaire des Alaouites” (Majlis al-Milli) qui paraît tenir plus d’un conseil de famille consultatif que d’une autorité exécutive ou contraignante. Composé de dix-huit membres cooptés parmi les cheikhs religieux et temporels des différentes tribus, il rend les grands arbitrages et définit les lignes de conduite générales de la communauté. Sa composition est en principe secrète et il se réunit de façon informelle. Son importance paraît avoir fortement diminué à mesure que se développait le pouvoir personnel de Hafez el-Assad pour lequel a été créé le siège inédit de Président d’honneur.

Premier drapeau de la Syrie sous mandat français (1920-1946)

L’instauration du mandat français en 1920 introduit une rupture brutale dans l’ordre interne de la communauté et dans ses rapports avec le reste du pays. Elle pose en fait les bases de la future accession au pouvoir de la communauté. Le 31 août 1920, la France, fidèle à sa politique de protection des minorités et soucieuse de se prémunir contre un “empire arabe” en jouant sur les divisions régionales, crée le Territoire autonome des Alaouites auquel font pendant diverses entités minoritaires chrétienne ( Liban) et druze (Djebel Druze). Un grand nombre de notables alaouites se rallient avec enthousiasme à l’idée d’une indépendance par rapport à la Syrie sunnite et, malgré quelques fausses notes comme la révolte de 1921 menée par cheikh Saleh al-Alawi, ils iront, en comparant leur sort à celui des Juifs de Palestine, jusqu’à élaborer en 1936 une déclaration de refus de rattachement à la Syrie à laquelle plusieurs centaines d’entre eux, dont le grand-père du Président, souscrivent. Sur le plan religieux et juridique, l’autorité mandataire essaie d’appliquer les principes qu’elle met en oeuvre dans ses autres possessions arabes. Le trop petit nombre et le manque de formation des cadres locaux conduisent, par une assimilation abusive des Alaouites au chiisme, à faire appel à des experts en matière religieuse et de statut personnel issus des communautés chiites du sud du Liban. Ils se sont plutôt bien adaptés, en laissant à la fois leur empreinte et quelques systèmes de relations utiles pour l’avenir quand le désordre interne du Liban conduira la Syrie dominée par des Alaouites à y rendre des arbitrages entre les communautés. C’est auprès de leur chef charismatique, l’Imam Moussa Sadr, que Hafez el-Assad avait d’ailleurs été se faire délivrer , au début des années 70, des brevets d’appartenance de la communauté alaouite à l’Islam chiite (Kramer, 1987:246 sqq.). Enfin, toujours soucieux de s’appuyer sur les minorités pour faire pièce au pouvoir sunnite de Damas, les Français favorisent et organisent la scolarisation, jusque là presque inconnue, des enfants des communautés minoritaires et poussent les plus brillants d’entre eux vers les carrières administratives et, en particulier, le métier des armes.

La confusion européenne au lendemain de la seconde guerre mondiale, le départ sans gloire de la puissance mandataire, suivi peu après de l’affrontement généralisé avec l’État juif nouvellement créé, a contraint la communauté alaouite dans son ensemble à revoir son système d’insertion dans le contexte régional selon trois grandes lignes directrices :

- Les effondrements successifs de l’Empire Ottoman puis des grands États d’Europe intéressés au Levant ont prouvé qu’aucune puissance extérieure à la région ne peut garantir durablement la survie d’une entité alaouite autonome ou indépendante. La communauté doit donc accepter de vivre à l’état de minorité dans l’ensemble arabe et musulman. Cette considération condamnait les notables qui s’étaient ouvertement prononcés, presque en totalité, pour une indépendance sous protection française et, en les dévalorisant, conduisit dans un premier temps et par défaut au renforcement du pouvoir des responsables religieux de la communauté qui avaient eu la prudence de ne pas s’engager sur ce terrain, puis à l’émergence rapide de cheikhs tribaux plus jeunes et plus dynamiques que ne le voulait la coutume.

- L’Islam sunnite demeurant l’adversaire principal, il convenait d’en neutraliser la menace en faisant si possible reconnaître la communauté comme musulmane en “gommant” sa spécificité, donc en adoptant en toutes circonstances des postures qui ne prêtent le flanc à aucune critique tant sur le plan de la religion que de l’arabisme. Cette stratégie conduira la communauté et ses leaders à des positions maximalistes sur tous les dossiers régionaux et internationaux concernant la question nationale arabe et les problèmes musulmans. Ils seront toujours, parfois jusqu’à la caricature, à la pointe des causes du monde arabe et les derniers à faire des concessions dans ce domaine, après que tous les responsables sunnites auront montré l’exemple.

- Enfin il convient de s’assurer le contrôle de l’État syrien afin de se prémunir, puisqu’il va bien falloir vivre avec eux, contre la vindicte prévisible des notables sunnites locaux ou étrangers, contre leur volonté latente d’islamiser les institutions ou de fondre le pays dans un vaste ensemble “arabo-musulman” [11]. Ce contrôle de l’État doit viser essentiellement celui de son appareil de contrainte et tendre à dissocier par tous les moyens le concept d’arabisme de celui d’Islam, en tous cas d’Islam sunnite.

La prise du pouvoir

C’est dans ce contexte et en fonction de ces principes que de jeunes responsables civils et militaires alaouites vont s’emparer du pouvoir en février 1966. Sans verser dans une explication conspiratoire de l’histoire [12], on doit constater qu’ils s’y sont longuement préparés. L’initiative en est venue principalement du nord de la région alaouite, c’est-à-dire de la confédération des Jurûd, probablement pour la double raison qu’ils étaient à la fois les plus humbles de la communauté et les plus exposés au voisinage turc. Dès 1933, Zaki al-Arsouzi, Alaouite d’Alexandrette, fonde une “Ligue d’action nationale” qui se veut nationaliste et socialiste sur le modèle des partis fascistes européens, comme le feront peu après les Maronites avec les “Phalanges” de Pierre Gemayel et les Grecs-orthodoxes avec le Parti Populaire Syrien d’Antoun Saadé. Au-delà de ses objectifs affichés d’indépendance, de réveil culturel et de panarabisme, la Ligue se veut intégratrice. Il s’agit, comme pour le P.P.S., de substituer à la référence religieuse une référence nationale qui permettrait à la minorité de ne plus voir son existence sociale et politique contestée sur une base religieuse. Arsouzi se heurte à la fois aux Français, aux Turcs à qui la puissance mandataire cède en 1939 le Sandjak d’Alexandrette, mais aussi aux notables indépendantistes alaouites des autres confédérations et au pouvoir bourgeois de Damas. Ses idées font cependant leur chemin chez les jeunes Alaouites du nord et chez les Druzes tandis que leur volet social séduit les jeunes Sunnites des provinces périphériques, “oubliés” eux aussi du développement industriel et commerçant des villes. Fin 1940, Arsouzi quitte la Ligue, maintenant exclusivement tournée vers la contestation de l’occupation turque du Sandjak, et crée à Damas une première version d’un “Baath al-Arabi” (Parti de la résurrection arabe), avec une idéologie similaire à celle initiale de la Ligue. Il ne rencontre guère de succès dans la capitale et se retire en 1942 à Lattaquieh où son influence morale reste très grande et d’où il poussera ses jeunes coreligionnaires à adhérer massivement au nouveau Baath, totalement inspiré du sien, que fondent en 1943 le Chrétien Michel Aflaq et le Sunnite Salaheddin Bitar. Panarabe, nationaliste, laïque, social, le Baath séduit à la fois les minorités non musulmanes ou dissidentes de l’Islam et nombre de ruraux musulmans orthodoxes face à l’hégémonie de la bourgeoisie sunnite. Son caractère authentiquement arabe le rend plus attractif et moins sujet à controverse que le “syrianisme” réducteur du P.P.S. ou l’athéisme importé du P.C., autres refuges idéologiques et militants des minoritaires. Pendant vingt ans, le Parti va être patiemment infiltré puis instrumentalisé par les Alaouites au détriment des autres groupes qui le composent (Chrétiens, Druzes, Ismaéliens, Sunnites provinciaux) pour prendre le contrôle de l’appareil militaire, puis politique et enfin économique et financier de l’État syrien.

Là encore, le rôle des Jurûd et, en leur sein, celui des Kalbiyyeh et de la famille Assad est déterminant. Originaire du bourg de Qardaha, la famille Assad, sans être pauvre, vit modestement de l’agriculture. Le père, Ali ben Sleiman, a voulu sortir de sa condition mais n’en a guère les moyens. Comme la plupart des Jurûd, il ne dispose ni des réseaux d’affaires dont bénéficient les Shamsites [13], ni des réseaux de pouvoir en général accaparés par les Matawira. Après la tentative familiale infructueuse de donner des signes d’allégeance aux Français, il mise tout sur ses fils pour lesquels il consentira de lourds sacrifices en vue de leur assurer une instruction la plus complète possible. Intelligent et rusé, discret et opiniâtre, doté d’une force physique peu commune, Hafez el-Assad, né en 1930, adhère au Parti Baath alors qu’il est encore lycéen sur l’instigation de Zaki Arsouzi et de son disciple Wahib Ghanem, également Alaouite d’Alexandrette, qui est un ami de la famille. Après avoir animé la section étudiante du parti au lycée de Lattaquieh, où il rencontre beaucoup de ceux qui seront ses compagnons de route, Hafez el-Assad passe son baccalauréat à Banyas puis se présente à l’école des officiers de Homs en 1950. Nanti de ses épaulettes de sous- lieutenant, il choisit l’aviation et rejoint en 1952 la toute nouvelle école de l’air d’Alep. Comme au lycée, il noue dans ces deux écoles les liens d’amitié, de confiance et de solidarité de promotion, les “réseaux”, qui le conduiront au pouvoir. Si dans son environnement les Alaouites comme son “co-pilote” Mohammad el-Khouli dominent, Assad sait aussi rechercher l’amitié de Sunnites modestes, provinciaux, hostiles aux bourgeois damascènes comme Naji Jamil, originaire de Deir ez-Zor – son équipier à l’Ecole de l’Air dont il fera son premier coordinateur des services de sécurité – ou Moustafa Tlass, né à Rastan – son compagnon à l’Ecole de Homs – qui deviendra son inamovible ministre de la Défense – assez forts pour l’aider, pas assez pour lui nuire…

On voit déjà se dessiner l’esquisse du dispositif ternaire qui reste encore aujourd’hui le schéma de base de toutes les stratégies du Président syrien, toujours entouré de trois cercles concentriques constitués chacun de trois éléments fidèles à sa personne et rivaux entre eux, donc manipulables. Si les Kalbiyyeh sont bien représentés dans son entourage, il sait qu’il lui faut composer avec les autres tribus alaouites qui ne verraient certainement pas d’un bon oeil l’un des moins prestigieux d’entre eux monopoliser le devenir communautaire. Il se lie donc à des représentants d’autres tribus comme Mohammed Omran (jeune cheikh d’un des clans les plus prestigieux des Haddâdîn) et Salah Jedid (du plus puissant des clans Matawira à l’époque), avec lesquels il formera en 1960 le noyau d’un comité militaire hostile à l’union avec l’Egypte, ou Mohammed el-Khouli (Haddâdîn), qui sera le chef de son premier “service de renseignements” personnel quand il sera lui-même le chef de l’armée de l’air. En 1958, il épouse Anisseh Makhlouf, d’une famille aisée de la prestigieuse confédération des Haddâdîn. Elle lui donnera cinq enfants et la collaboration fidèle de tout son clan puisque Adnan Makhlouf, son plus proche cousin, est depuis plus de vingt ans le chef de la garde présidentielle.

Quand, confrontés à la double pression des Anglo-Saxons pour un alignement de la Syrie sur le Pacte de Baghdad et des jeunes officiers subalternes pour une politique encore plus indépendante et nationaliste, les dirigeants bourgeois de Damas, soutenus par la “vieille garde” du Baath, s’en remettent à la tutelle de l’Égypte

Al-Bitar, Louai al-Atassi et Nasser en mars 1963.

nassérienne le 12 janvier 1958, les Alaouites comprennent vite qu’ils sont victimes d’un marché de dupes. Rapidement confirmés dans cette opinion par les maladresses de l’administration égyptienne qui les marginalise aussi bien en tant que minorité que dans leurs privilèges de fonction si difficilement acquis, ils entreprennent une série de manoeuvres souterraines pour sortir de l’union qui reçoivent vite l’adhésion de tous les laissés pour compte de l’unité. Le comité militaire clandestin, alors constitué autour de Omrane, Jedid et Assad, va devenir pour presque dix ans le creuset où va s’élaborer la prise du pouvoir par les prétoriens alaouites aux dépens des Sunnites de Damas d’abord, puis des politiciens du Baath et enfin des “aventuristes” de la communauté. Hafez el-Assad et ses fidèles y développent jusqu’au raffinement l’art de l’action clandestine, les vertus de la patience et de la discrétion, l’habileté des manipulations complexes.

Le 28 septembre 1961, un premier coup d’État militaire à Damas prononce la rupture avec Le Caire et rétablit une République bourgeoise dominée par ses éléments traditionnels contre lesquels la réaction égyptienne ne peut qu’être mesurée. Le 8 mars 1963, un second pronunciamento militaire conduit par le capitaine druze Salim Hatoum renverse le régime civil, rappelle les officiers limogés, dont Hafez el-Assad, pendant la période unioniste ou la république “sécessionniste” et remet le pouvoir au parti Baath renforcé par sa prise du pouvoir en Irak un mois plus tôt. L’armée passe cependant sous le contrôle du comité militaire animé par les Alaouites. Devenu chef de l’Armée de l’Air, Assad y met sur pied, dès 1963 et dans la plus stricte illégalité, un service de renseignements efficace relayé dès 1965 au niveau de l’action par une milice au statut ambigu, les Détachements de Défense (saraya ad-difaa) qu’il confie à son frère Rifaat, passé en 1962 de l’administration des douanes au service de l’Armée. Le 23 février 1966, un nouveau putsch militaire chasse la vieille garde politique du Baath. Le Chrétien Aflaq et le Sunnite Bitar prennent le chemin de l’exil, remplacés par l’aile gauchiste du Parti pilotée par des militaires populistes sous la direction de Salah Jedid. Ce dernier commet l’erreur des bourgeois damascènes en abandonnant le contrôle de l’armée pour se consacrer à une action politique qu’il veut résolument socialiste et nationaliste sans référence réelle aux intérêts particuliers de sa communauté. Hafez el-Assad devient ministre de la Défense et asseoit son emprise sur l’Armée, laissant son rival s’user en projets généreux et utopiques, sans omettre de saisir toute occasion de saper subtilement son pouvoir et ses plans. Le 25 février 1969, l’Armée prend le contrôle du pays et, sans chasser Salah Jedid, l’oblige à mettre un terme à ses expériences progressistes devenues impopulaires et à son monopole sur les décisions politiques en rappelant aux affaires des membres de l’establishment traditionnel ainsi que des ténors de diverses formations politiques. Jouant sur ce pluralisme qu’il a suscité, Hafez el-Assad, sans apparaître personnellement, fait prononcer le 12 novembre 1970 la destitution de Jedid, l’arrestation des officiers qui lui sont encore hostiles et prend enfin le contrôle de l’État qui lui sera officiellement confié début 1971 par son accession à la Présidence largement plébiscitée.

Notes

[1] En 1994, la Syrie compte environ 13 millions d’habitants. Les minorités non sunnites et/ou non arabes représentent environ 35% de la population (extrapolations selon la méthode préconisée par Seurat, 1980:92): Alaouites (12%), Chrétiens de diverses obédiences (7%), Kurdes (6%), Druzes (5%), Arméniens (3%), Divers (Juifs, Tcherkesses, Assyriens, etc…environ 2%).

[2] “La guerre sainte est légitime…contre ces sectateurs du sens caché, plus infidèles que les Chrétiens et les Juifs, plus infidèles que les idôlatres, qui ont fait plus de mal à la religion que les Francs…”. (Cité par Pipes 1989:434.)

[3] Si l’on prend cette évolution en considération, les controverses entre Perthes (1992:105-113) et Landis (1993:143-151) ou entre Pipes (1989:429-450) et Sadowsky (1988:168), que l’auteur n’a ni vocation ni surtout autorité à trancher, peuvent apparaître comme la vision d’un même phénomène selon deux perspectives différentes.

[4] D’où le nom d’Alaouites qui leur a été donné par les Sunnites (‘Alawiyyîn, partisans de Ali); comme il a été donné, sans qu’il y ait aucun lien entre eux, à l’actuelle dynastie filalienne marocaine qui revendique sa descendance au Prophète via Abdallah Kamil, l’un des arrière petit fils de Ali et Fatima, qui serait venu s’installer au Tafilalet. Selon les périodes, les Alaouites de Syrie se désignent eux-mêmes sous le nom d’Alaouites quand ils souhaitent entretenir la confusion sur leur appartenance à l’Islam chiite ou sous celui de Nosaïris quand ils entendent être clairement distingués des Musulmans.

[5] Jusqu’aux années 60, les familles aisées des grandes villes de Syrie et du Liban “embauchaient” comme bonnes à tout faire des fillettes alaouites dès l’âge de huit ou dix ans. L’enfant étant mineur, une somme forfaitaire était versée , au titre de sa rémunération et pour solde de tout compte, au père ou au représentant légal qui abandonnait de facto tout élément de puissance parentale au profit de l’employeur. Prise en charge, mais non rémunérée, par la famille d’accueil, l’enfant entrait alors dans une vie de quasi-esclavage. La mémoire collective de cette pratique séculaire courante, que l’on se garde bien d’évoquer aujourd’hui, a pesé extrêmement lourd dans les formes de l’établissement du pouvoir alaouite en Syrie et dans son comportement au Liban.

[6] La taqiya (aussi connue sous le nom persan de ketman) est, très grossièrement, la faculté laissée au croyant de dissimuler son appartenance ainsi que de mentir ou de ne pas tenir ses engagements pour protéger la collectivité ou sa propre personne en tant que membre de la communauté.

[7] Voir carte

[8] Littéralement, “ceux qui habitent le jurd (zone de la montagne où rien ne pousse)”. De fait, avec la cession du Sandjak, cette confédération s’est trouvée pratiquement réduite en territoire syrien à sa composante Kalbiyyeh sous le nom desquels on la désigne usuellement..

[9] Une légende tenace veut que Hafez el-Assad se rattache au clan Noumeïtila de la confédération des Matawira, sans doute parce que ces derniers ont été les premiers de la communauté à investir les circuits de pouvoir en Syrie et qu’il était alors inconcevable qu’un Kalbiyyeh pût avoir des prétentions à ce sujet. On remarque aussi que Qardaha, village situé à l’extrémité sud du territoire des Jurûd, à quelques kilomètres de Matwa, est limitrophe du territoire des Matawiras. La même confusion s’attache à d’autres responsables actuels du régime (Mohammed el-Khouli, Ali Aslan). Voir sur ce point Le Gac (1991:78-79).

[10] Sur le passage d’un référentiel de solidarité à l’autre, voir Khalaf (1993:178-194)

[11] Il convient de noter que de 1946 à 1958 , sous la pression des diplomaties anglo-saxonnes pour la constitution d’un Pacte anti-soviétique ancré à Baghdad et pour la protection des accès aux ressources pétrolières, le Moyen Orient était dominé par les faits séoudite et hachémite. L’édification d’un grand “Royaume arabe” était encore un mythe vivace et la seule alternative offerte était le ralliement, à partir de 1952, au panarabisme nassérien peu sensible aux intérêts minoritaires.

[12] Plusieurs auteurs cités par Pipes (1989:429) font allusion à des réunions “secrètes” tenues dans les années 60 entre responsables civils, militaires et religieux de la communauté pour mettre au point une stratégie clandestine de prise et de gestion du pouvoir organisée dans ses moindres détails. L’impartialité de ces auteurs -quand ils ne se réfugient pas dans l’anonymat – est cependant sujette à caution et ils n’apportent guère d’éléments incontestables permettant d’étayer l’idée d’une démarche aussi élaborée.

[13] Les quatre grandes confédérations alaouites se partagent en “shamsites” (Haddâdîn, Khayyâtîn) et en “Qamarites” (Jurûd, Matawira) suivant des considérations subtiles sur l’importance religieuse respective qu’ils accordent au Soleil (shams) et à la Lune (qamar). Lors de sa brève existence sous le mandat français, l’État des Alaouites s’était doté d’un drapeau représentant un soleil flamboyant sur fond blanc, témoignant à la fois une distance par rapport aux couleurs et symboles traditionnels de l’Islam et la dominance des confédérations du sud.

When I visited the Naval Museum in Madrid several years ago, I took away as a souvenir a facsimile of a coloured 1756 naval manual illustration entitled Banderas que las naciones arbolan en la mar. It shows ninety different flags that might conceivably be met with upon the high seas by Spanish sailors—ranging from the personal standard of the Hapsburgs and the banner of the Papal States to the presumably more frequently encountered flags of Brabant, Corsica, the English East India Company, Flanders, Pomerania, Riga, Stettin, Zeeland and many other names now relegated to history’s footnotes.

When I visited the Naval Museum in Madrid several years ago, I took away as a souvenir a facsimile of a coloured 1756 naval manual illustration entitled Banderas que las naciones arbolan en la mar. It shows ninety different flags that might conceivably be met with upon the high seas by Spanish sailors—ranging from the personal standard of the Hapsburgs and the banner of the Papal States to the presumably more frequently encountered flags of Brabant, Corsica, the English East India Company, Flanders, Pomerania, Riga, Stettin, Zeeland and many other names now relegated to history’s footnotes.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Dans son nouveau livre, Dominique Venner revient sur l’un de ses thèmes forts : l’imprévu dans l’histoire, à l’occasion de la réédition enrichie d’un ouvrage paru en 1988 et consacré au meurtre politique. Ce livre offre des récits vifs et ouvrent de vastes horizons à la réflexion.

Dans son nouveau livre, Dominique Venner revient sur l’un de ses thèmes forts : l’imprévu dans l’histoire, à l’occasion de la réédition enrichie d’un ouvrage paru en 1988 et consacré au meurtre politique. Ce livre offre des récits vifs et ouvrent de vastes horizons à la réflexion.![9783937820170[1].JPG](http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/media/01/02/3354357282.JPG)

L'action débute sur le front méridional : venant de Palestine, le 10 juin la 7e Division australienne d'infanterie avance le long de la côte de Saint-Jean d'Acre vers Beyrouth, couverte par les canons de la marine britannique, tandis que la 5e brigade indienne d'infanterie et les Français "Libres" progressent à l'intérieur vers Damas. Au bout d'une semaine, ces progressions sont bloquées, souvent repoussées par des contre-attaques françaises, mais trop diffuses et d'ampleur limitée ; Dentz n'ose pas concentrer tactiquement ses moyens — déployés sur tout le front sur trois lignes parallèles — et profiter de la supériorité ponctuelle momentanée ; sitôt le terrain reconquis, il n'exploite pas le trouble adverse, mais organise la réoccupation systématique des positions défensives, il est vrai plutôt bonnes, qui s'appuient sur le relief.

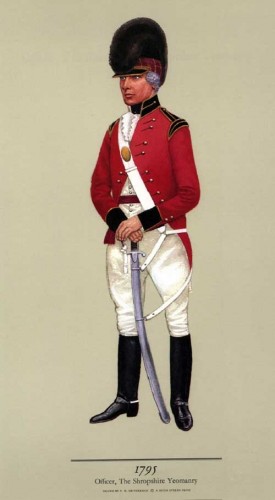

L'action débute sur le front méridional : venant de Palestine, le 10 juin la 7e Division australienne d'infanterie avance le long de la côte de Saint-Jean d'Acre vers Beyrouth, couverte par les canons de la marine britannique, tandis que la 5e brigade indienne d'infanterie et les Français "Libres" progressent à l'intérieur vers Damas. Au bout d'une semaine, ces progressions sont bloquées, souvent repoussées par des contre-attaques françaises, mais trop diffuses et d'ampleur limitée ; Dentz n'ose pas concentrer tactiquement ses moyens — déployés sur tout le front sur trois lignes parallèles — et profiter de la supériorité ponctuelle momentanée ; sitôt le terrain reconquis, il n'exploite pas le trouble adverse, mais organise la réoccupation systématique des positions défensives, il est vrai plutôt bonnes, qui s'appuient sur le relief. Like primitive Rome, England, during the Middle Ages, had an unusually homogeneous population of farmers, who made a remarkable infantry. Not that the cavalry was defective; on the contrary, from top to bottom of society, every man was a soldier, and the aristocracy had excellent fighting qualities. Many of the kings, like Coeur-de-Lion, Edward III, and Henry V, ranked among the ablest commanders of their day; the Black Prince has always been a hero of chivalry; and earls and barons could be named by the score who were famous in the Hundred Years’ War.

Like primitive Rome, England, during the Middle Ages, had an unusually homogeneous population of farmers, who made a remarkable infantry. Not that the cavalry was defective; on the contrary, from top to bottom of society, every man was a soldier, and the aristocracy had excellent fighting qualities. Many of the kings, like Coeur-de-Lion, Edward III, and Henry V, ranked among the ablest commanders of their day; the Black Prince has always been a hero of chivalry; and earls and barons could be named by the score who were famous in the Hundred Years’ War. At the outset the remedy applied was comparatively mild, for able-bodied mendicants were only to be whipped until they were bloody, returned to their domicile, and there whipped until they put themselves to labor. As no labor was supplied, the legislation failed, and in 1537 the emptying of the convents brought matters to a climax. Meanwhile Parliament tried the experiment of killing off the unemployed; by the second act vagrants were first mutilated and then hanged as felons.[6]

At the outset the remedy applied was comparatively mild, for able-bodied mendicants were only to be whipped until they were bloody, returned to their domicile, and there whipped until they put themselves to labor. As no labor was supplied, the legislation failed, and in 1537 the emptying of the convents brought matters to a climax. Meanwhile Parliament tried the experiment of killing off the unemployed; by the second act vagrants were first mutilated and then hanged as felons.[6]

Piotr Stolypin nació en el seno de una familia aristocrática en 1862, que era fiel a los zares desde el siglo XVI. Amigo de Gogol y Tolstoi, también estaba emparentado con Lermontov y en un ambiente de tanta cultura, el joven Stolypin hablará con fluidez el francés, inglés y el alemán. Cuando cumpla 19 años será enviado a la Universidad de San Petersburgo, donde estudiará en la facultad de Física y matemáticas. Cuando se licencié ocupará el puesto de comisario de la nobleza en Kovno en 1889, donde permanecerá hasta 1902. En aquel lugar es donde el joven funcionario se hará un experto en temas de agricultura y administración local. Allí es donde llegará a la conclusión que la suerte de Rusia estaba unida a su inmenso campesinado, más de un 80 % de la población, y que la solución pasaba por la eliminación de los comunales existentes y su distribución entre los campesinos, transformando a estos en pequeños propietarios.

Piotr Stolypin nació en el seno de una familia aristocrática en 1862, que era fiel a los zares desde el siglo XVI. Amigo de Gogol y Tolstoi, también estaba emparentado con Lermontov y en un ambiente de tanta cultura, el joven Stolypin hablará con fluidez el francés, inglés y el alemán. Cuando cumpla 19 años será enviado a la Universidad de San Petersburgo, donde estudiará en la facultad de Física y matemáticas. Cuando se licencié ocupará el puesto de comisario de la nobleza en Kovno en 1889, donde permanecerá hasta 1902. En aquel lugar es donde el joven funcionario se hará un experto en temas de agricultura y administración local. Allí es donde llegará a la conclusión que la suerte de Rusia estaba unida a su inmenso campesinado, más de un 80 % de la población, y que la solución pasaba por la eliminación de los comunales existentes y su distribución entre los campesinos, transformando a estos en pequeños propietarios.

Au début du mois de mars 1920, Ehrhardt entre en rébellion contre l’ordre de dissolution et rejoint le putsch dit de Kapp, mené par un haut fonctionnaire prussien, Wolfgang Kapp, et par un général d’infanterie, Walther von Lüttwitz. La mission de la Brigade Ehrhardt était d’occuper le quartier gouvernemental de la capitale. Au cours de ce putsch, Ehrhardt a fait savoir ce qu’il entendait par “application de la violence” en cas de coup d’Etat: après que les fonctionnaires berlinois aient refusé de travailler pour le gouvernement putschiste, Ehrhardt aurait dit: “Eh bien, nous allons coller au mur les trois premiers fonctionnaires qui refusent de travailler. On verra bien alors si le reste va se mettre à travailler ou non”. Lorsque Kapp refusa d’appliquer cette mesure drastique, Ehrhardt a lâché ce commentaire: “Alors le putsch est fichu!”.

Au début du mois de mars 1920, Ehrhardt entre en rébellion contre l’ordre de dissolution et rejoint le putsch dit de Kapp, mené par un haut fonctionnaire prussien, Wolfgang Kapp, et par un général d’infanterie, Walther von Lüttwitz. La mission de la Brigade Ehrhardt était d’occuper le quartier gouvernemental de la capitale. Au cours de ce putsch, Ehrhardt a fait savoir ce qu’il entendait par “application de la violence” en cas de coup d’Etat: après que les fonctionnaires berlinois aient refusé de travailler pour le gouvernement putschiste, Ehrhardt aurait dit: “Eh bien, nous allons coller au mur les trois premiers fonctionnaires qui refusent de travailler. On verra bien alors si le reste va se mettre à travailler ou non”. Lorsque Kapp refusa d’appliquer cette mesure drastique, Ehrhardt a lâché ce commentaire: “Alors le putsch est fichu!”. Dès ce moment, les nationaux-socialistes considèreront Ehrhardt comme une personnalité peu fiable. Le Capitaine a perdu aussi beaucoup de son prestige dans les rangs des droites allemandes. En avril 1924, vu l’imminence d’un procès pénal, Hermann Ehrhardt quitte le Reich pour l’Autriche; il revient en octobre 1926 après une amnistie générale décrétée par le Président Paul von Hindenburg. En 1931, Ehrhardt fonde le groupe “Gefolgschaft” (littéralement: la “Suite”), qui, malgré la perte de prestige subie par Ehrhardt, parvient encore à rassembler plus de 2000 de ses adhérants, ainsi que des nationaux-socialistes et des communistes déçus. Ils voulaient empêcher Hitler de prendre le pouvoir et fustigeaient la “mauvaise politique de la NSDAP”. Ehrhardt entretenait des rapports avec Otto Strasser et l’aile socialiste de la NSDAP. En 1933, Ehrhardt s’installe sur les terres du Comte von Bredow à Klessen dans le Westhavelland. En juin 1934, quand Hitler élimine Röhm, Ehrhardt aurait normalement dû faire partie des victimes de la purge. Il a réussi à prendre la fuite à temps devant les SS venus pour l’abattre, en se réfugiant dans la forêt toute proche. Les sicaires ne l’ont que mollement poursuivi car, dit-on, beaucoup de membres de sa Brigade avaient rejoint les SS. Ehrhardt s’est d’abord réfugié en Suisse puis, en 1936, en Autriche, où son épouse, le Princesse Viktoria zu Hohenlohe-Öhringen possédait un château à Brunn im Walde dans le Waldviertel. Ehrhardt n’a plus fait autre chose que gérer ces terres, que participer à des chasses au gibier et que s’adonner à la sylviculture. Il s’est complètement retiré de la politique.

Dès ce moment, les nationaux-socialistes considèreront Ehrhardt comme une personnalité peu fiable. Le Capitaine a perdu aussi beaucoup de son prestige dans les rangs des droites allemandes. En avril 1924, vu l’imminence d’un procès pénal, Hermann Ehrhardt quitte le Reich pour l’Autriche; il revient en octobre 1926 après une amnistie générale décrétée par le Président Paul von Hindenburg. En 1931, Ehrhardt fonde le groupe “Gefolgschaft” (littéralement: la “Suite”), qui, malgré la perte de prestige subie par Ehrhardt, parvient encore à rassembler plus de 2000 de ses adhérants, ainsi que des nationaux-socialistes et des communistes déçus. Ils voulaient empêcher Hitler de prendre le pouvoir et fustigeaient la “mauvaise politique de la NSDAP”. Ehrhardt entretenait des rapports avec Otto Strasser et l’aile socialiste de la NSDAP. En 1933, Ehrhardt s’installe sur les terres du Comte von Bredow à Klessen dans le Westhavelland. En juin 1934, quand Hitler élimine Röhm, Ehrhardt aurait normalement dû faire partie des victimes de la purge. Il a réussi à prendre la fuite à temps devant les SS venus pour l’abattre, en se réfugiant dans la forêt toute proche. Les sicaires ne l’ont que mollement poursuivi car, dit-on, beaucoup de membres de sa Brigade avaient rejoint les SS. Ehrhardt s’est d’abord réfugié en Suisse puis, en 1936, en Autriche, où son épouse, le Princesse Viktoria zu Hohenlohe-Öhringen possédait un château à Brunn im Walde dans le Waldviertel. Ehrhardt n’a plus fait autre chose que gérer ces terres, que participer à des chasses au gibier et que s’adonner à la sylviculture. Il s’est complètement retiré de la politique. Tirpitz (1849-1930) German admiral and politician, was born at Kiistrin March Iq 1849. He entered the Prussian navy in 1865, and by 1890 had risen to be chief-of-staff of the Baltic station in the Imperial navy. In 1892 he was in charge of the work of the chief-of-staff in the higher command of the navy. He was promoted to be rear-admiral in 1895, and in 1896 and 1897 he was in command of the cruiser division in east Asiatic waters. In 1899 he reached the rank of vice-admiral and in 1903 that of admiral. For the long period of 19 years, from 1897 to 1916, he was Secretary of State for the Imperial navy, and in this capacity advocated the navy bills of 1898, 1900, 1907 and 1912 for increasing the German fleet and successfully carried them through the Reichstag. In 1911 he received the rank of grand-admiral, and he retired in 1916.

Tirpitz (1849-1930) German admiral and politician, was born at Kiistrin March Iq 1849. He entered the Prussian navy in 1865, and by 1890 had risen to be chief-of-staff of the Baltic station in the Imperial navy. In 1892 he was in charge of the work of the chief-of-staff in the higher command of the navy. He was promoted to be rear-admiral in 1895, and in 1896 and 1897 he was in command of the cruiser division in east Asiatic waters. In 1899 he reached the rank of vice-admiral and in 1903 that of admiral. For the long period of 19 years, from 1897 to 1916, he was Secretary of State for the Imperial navy, and in this capacity advocated the navy bills of 1898, 1900, 1907 and 1912 for increasing the German fleet and successfully carried them through the Reichstag. In 1911 he received the rank of grand-admiral, and he retired in 1916.

Otto Strasser nasce il 10 settembre 1897 in una famiglia di funzionari bavaresi. Suo fratello Gregor (che sarà uno dei capi del partito nazista ed un serio concorrente di Hitler) è maggiore di cinque anni. L’uno e l’altro beneficiano di solidi antecedenti familiari: il padre Peter, che si interessa di economia politica e di storia, pubblica sotto lo pseudonimo di Paaul Weger un opuscolo intitolato Das neue Wesen, nel quale si pronuncia per un socialismo cristiano e sociale. Secondo Paul Strasser, fratello di Gregor e Otto, “in questo opuscolo si trova già abbozzato l’insieme del programma culturale e politico di Gregor e Otto, cioè un socialismo cristiano sociale, che è indicato come la soluzione alle contraddizioni e alle mancanze nate dalla malattia liberale, capitalista e internazionale dei nostri tempi.” Quando scoppia la Grande Guerra, Otto Strasser interrompe i suoi studi di diritto e di economia per arruolarsi il 2 agosto 1914 (è il più giovane volontario di Baviera). Il suo brillante comportamento al fronte gli varrà la Croce di Ferro di prima classe e la proposta per l’ Ordine Militare di Max-Joseph. Prima della smobilitazione nell’aprile/maggio 1919, partecipa con il fratello Gregor, nel Corpo Franco von Epp, all’assalto contro la Repubblica sovietica di Baviera. Ritornato alla vita civile Otto riprende i suoi studi a Berlino nel 1919 e fonda la “Associazione universitaria dei veterani socialdemocratici”.

Otto Strasser nasce il 10 settembre 1897 in una famiglia di funzionari bavaresi. Suo fratello Gregor (che sarà uno dei capi del partito nazista ed un serio concorrente di Hitler) è maggiore di cinque anni. L’uno e l’altro beneficiano di solidi antecedenti familiari: il padre Peter, che si interessa di economia politica e di storia, pubblica sotto lo pseudonimo di Paaul Weger un opuscolo intitolato Das neue Wesen, nel quale si pronuncia per un socialismo cristiano e sociale. Secondo Paul Strasser, fratello di Gregor e Otto, “in questo opuscolo si trova già abbozzato l’insieme del programma culturale e politico di Gregor e Otto, cioè un socialismo cristiano sociale, che è indicato come la soluzione alle contraddizioni e alle mancanze nate dalla malattia liberale, capitalista e internazionale dei nostri tempi.” Quando scoppia la Grande Guerra, Otto Strasser interrompe i suoi studi di diritto e di economia per arruolarsi il 2 agosto 1914 (è il più giovane volontario di Baviera). Il suo brillante comportamento al fronte gli varrà la Croce di Ferro di prima classe e la proposta per l’ Ordine Militare di Max-Joseph. Prima della smobilitazione nell’aprile/maggio 1919, partecipa con il fratello Gregor, nel Corpo Franco von Epp, all’assalto contro la Repubblica sovietica di Baviera. Ritornato alla vita civile Otto riprende i suoi studi a Berlino nel 1919 e fonda la “Associazione universitaria dei veterani socialdemocratici”. The Legionary Doctrine (also called Legionarism) refers to the philosophy and beliefs presented by the Legion of Michael the Archangel (also commonly known as the Iron Guard), the Romanian Christian Nationalist organization founded by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, who is the key figure in the creation of its doctrine. It is necessary to clarify what the members of the Legionary Movement taught and believed due to many misconceptions arising from ignorance and outright deception, as well as the mistaken assumption that the Legionary Movement was largely an imitation of Fascism or National Socialism.

The Legionary Doctrine (also called Legionarism) refers to the philosophy and beliefs presented by the Legion of Michael the Archangel (also commonly known as the Iron Guard), the Romanian Christian Nationalist organization founded by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, who is the key figure in the creation of its doctrine. It is necessary to clarify what the members of the Legionary Movement taught and believed due to many misconceptions arising from ignorance and outright deception, as well as the mistaken assumption that the Legionary Movement was largely an imitation of Fascism or National Socialism.

Diana was married to Bryan Guinness when she met Mosley, and soon became his mistress. Mosley’s wife died suddenly of peritonitis in 1933 (though he was plagued the rest of his life that infidelities and political stress might have been the cause). Mosley and Diana were married at the home of Joseph Goebbels in 1936, with Hitler as guest of honor.

Diana was married to Bryan Guinness when she met Mosley, and soon became his mistress. Mosley’s wife died suddenly of peritonitis in 1933 (though he was plagued the rest of his life that infidelities and political stress might have been the cause). Mosley and Diana were married at the home of Joseph Goebbels in 1936, with Hitler as guest of honor.