Le dernier « diable » d’Europe

par Georges FELTIN-TRACOL

Le samedi 2 février 2013 à Paris, à l’initiative du Mouvement Troisième Voie de Serge Ayoub et du mensuel Salut public d’Hugo Lesimple se tenait une manifestation contre tous les impérialismes. Aux côtés des organisateurs s’étaient associés la N.D.P. (Nouvelle Droite populaire), Synthèse nationale, Le Lys Noir et des délégations amies venues du Québec, de Syrie et de Belgique. Plus de 800 personnes marchèrent derrière une banderole sur laquelle on pouvait lire que « les héros du peuple sont immortels » et au dessus de laquelle figuraient cinq portraits de résistants au « Nouveau désordre financiariste mondial » : le combattant tchetnik serbe Draja Mihailovitch (1893 – 1946), le président syrien Bachar El-Assad, le commandante bolivarien du Venezuela Hugo Chavez, le président russe Vladimir Poutine et le président de la Biélorussie Alexandre Loukachenko.

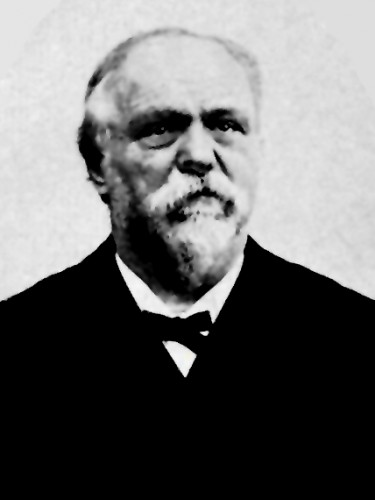

Guère connu en France, le président Loukachenko fait cependant l’objet d’une tout première biographie parue en français. Écrite par Valeri Karbalevitch, l’ouvrage comme l’indique son titre éloquent et grossier, Le satrape de Biélorussie, est une violente charge contre le chef d’État biélorusse. Il faut dire que l’auteur anime une émission en biélorusse sur Radio Liberty, une radio financée par les États-Unis et la C.I.A., ce qui en fait un stipendié de l’Occident globalitaire (1).

Bien que ce livre soit totalement subjectif et partial, Karbalevitch n’arrive pas à taire les indéniables qualités politiques d’Alexandre Loukachenko. Évoquant la grande animosité du futur président envers la nomenklatura soviétique, l’auteur lui attribue « un sentiment parfaitement sincère (p. 45) ». Il l’estime plus loin « armé d’une volonté de fer (p. 76) » et le définit même comme « un véritable animal politique (p. 131) ».

Valeri Karbalevitch dépeint par conséquent un homme d’État dont la stature se fait maintenant rare en Europe et même dans le monde. « Loukachenko possède indiscutablement du charisme et une importante capacité de persuasion (p. 141) »; il « fait preuve d’une réelle audace politique et personnelle (p. 151) ». « Homme politique chevronné (p. 307) », « brillant orateur et agitateur maîtrisant l’art du discours politique à la perfection, le président biélorusse aime la casquette de tribun (p. 139) ». L’auteur cite un politologue russe, Leonid Radzikhovski, pour qui « Loukachenko est un homme fort et un psychologue intelligent (p. 336) ». On comprend mieux pourquoi il dirige la Biélorussie d’une autorité ferme depuis l’été 1994. Mais le tempérament affirmé du « premier des Biélorusses » s’est accordé aux aspirations populaires de ses compatriotes. Cette connaissance intime des mentalités biélorusses provient d’une grande expérience de la vie.

Avant la politique

Alexandre Loukachenko naît le 30 août 1954 à Kopys d’une mère célibataire, Ekaterina, dont il porte le patronyme. Il grandit à la campagne dans un milieu pauvre. Élève brillant et passionné de hockey sur glace, il suit des études d’histoire à l’Institut pédagogique de Moguilev. En 1975, il décroche le diplôme d’historien avec une mention « Très bien » et effectue ensuite son service militaire chez les gardes-frontières soviétiques. Le jeune sergent Loukachenko y est instructeur politique. Libéré de ses obligations militaires en 1978, il devient professeur d’histoire-géographie, mais l’enseignement l’ennuie vite; il s’inscrit alors à des cours d’économie agricole dès 1979. Il y décroche en 1985 un nouveau diplôme. En 1980 – 1981, il est rappelé sous les drapeaux et sert au sein des fusiliers – motocyclistes avec le grade de lieutenant-chef.

Son biographe et adversaire remarque une instabilité professionnelle certaine. Dès sa prime jeunesse, il développe des traits forts de caractère : « Esprit rétif, sens aigu de la justice, défense des faibles et des offensés (p. 36). » Sa franchise et la rudesse de ses propos lui valent deux blâmes de la part du Parti communiste dont il est membre ! Son attitude ne l’empêche pas de devenir député du soviet local de Chklov et secrétaire de kolkhoze en 1985. L’année suivante, il est promu directeur du sovkhoze Goradets qui est en déficit. « Le jeune directeur se mit énergiquement au travail. Il commença par mettre de l’ordre, en réinstaurant la discipline et en assurant le bon état de marche des machines (p. 39). » Vivant de manière très modeste avec son épouse et leurs deux jeunes enfants, Alexandre Loukachenko se donne corps et âme à la réussite du sovkhoze. « En deux ans, le produit brut de son exploitation fut multiplié par 2,2. Le sovkhoze cessa d’être déficitaire (p. 40). »

Les autorités locales, puis de la République socialiste soviétique de Biélorussie, commencent à s’intéresser de près à ce directeur agricole aux coups de gueule retentissants. Alexandre Loukachenko est reçu à Minsk, puis à Moscou, au moment où sont lancées les réformes gorbatchéviennes. « Cet homme ambitieux et énergique n’a pas pu se frayer un chemin jusqu’à la haute nomenklatura avant que ne commence la perestroïka gorbatchévienne (p. 38). » En effet, « à l’époque soviétique, pour moult raisons, Loukachenko n’avait pas l’opportunité de faire carrière, mais la perestroïka gorbatchévienne et l’effondrement du système communiste lui permirent un envol vertigineux. Cependant ce directeur de sovkhoze devait posséder un caractère très particulier et des capacités certaines pour se frayer un chemin jusqu’au fauteuil présidentiel (pp. 27 – 28) ».

Le futur responsable biélorusse soutient au départ la politique réformatrice de Mikhaïl Gorbatchev. Puis, « dans cette période de cataclysme social croissant, les traits de caractère qui le désavantageaient dans le passé le portent en avant. Loukachenko devient un homme connu, au-delà même de la nomenklatura du district. Il acquiert l’image d’un homme courageux, qui n’a pas peur de dire la vérité. Il comprend que son temps est enfin venu (p. 41) ».

Les premiers pas électoraux

En 1989, l’Union Soviétique organise ses premières élections semi-libres pour le Soviet suprême (le Parlement soviétique). Alexandre Loukachenko n’hésite pas à affronter Viatcheslav Kebitch, vice-président du Conseil des ministres de Biélorussie et responsable du Gosplan (ministère de la planification). La campagne électorale est rude pour le jeune directeur – candidat qui affronte l’un des principaux apparatchiki du Régime. « Mais la donne politique avait changé. Même dans un coin perdu, il était désormais difficile d’intimider et d’écraser quelqu’un qui n’avait pas peur. Or Loukachenko n’avait pas peur et il se battait avec un art politique consommé, faisant preuve d’une combativité et d’une capacité de travail hors du commun (p. 44). » Si Kebitch remporte l’élection avec 51 % des suffrages, Alexandre Loukachenko obtient quand même 45,7 % des voix ! L’âpre campagne électorale l’a transformé. « Chez cet homme qui possédait de grandes réserves d’énergie, le goût du risque et une volonté de victoire indomptable, s’éveillera un vrai talent d’homme politique (p. 47). »

En 1990 se déroulent des élections libres pour le Soviet suprême de la Biélorussie. Alexandre Loukachenko pose sa candidature dans une circonscription rurale et tient un discours anti-Système radical, car il « incarne un nouveau type d’homme politique, caractéristique de l’époque post-soviétique. Doté d’un flair politique extraordinaire, il a compris plus vite et mieux que les autres qu’en appeler directement au peuple pour obtenir son soutien était la condition sine qua non de toute prise de pouvoir (p. 28) ». Très vite, « les gens allaient aux meetings de Loukachenko comme s’ils allaient admirer une star de cinéma : il avait un don d’orateur peu ordinaire (du moins selon les standards locaux) et savait utiliser des mots simples qui allaient droit au cœur (p. 46) ». Au premier tour du scrutin, il rassemble 45,51 % et est élu député lors du second tour avec 68,21 %.

Membre du Soviet suprême, ce gorbatchévien critique se rapproche de l’opposition nationaliste du Front populaire biélorusse. Il approuve ainsi en mai 1991 la souveraineté biélorusse. Il apporte toutefois son soutien à Gorbatchev lors du coup d’État des 19 – 21 août 1991. Quelques semaines plus tôt, il animait un petit groupe parlementaire « centriste » : « Les communistes de Biélorussie pour la démocratie ». Alexandre Loukachenko défend une évolution de l’U.R.S.S. vers un véritable ensemble fédéral. Sa position est donc médiane entre le conservatisme centralisateur et les séparatismes nationaux. Toutefois, son message passe mal, car « faute de savoir jouer en équipe, il reste un politique solitaire (p. 49) ». Ce qui paraît à ce moment-là comme un inconvénient se révèle vite comme un atout majeur parce que « enfant de la glasnost gorbatchévienne, il comprit, plus tôt et plus rapidement que les autres, la force de l’opinion publique. Il ne perdit donc pas de temps à créer un parti politique, mais utilisa son tempérament véhément pour séduire la population (p. 64) ».

L’effondrement de l’U.R.S.S. et l’accession à l’indépendance de la Biélorussie en décembre 1991 le rapprochent des communistes conservateurs et nostalgiques. Par des discours virulents souvent retransmis à la télévision qui le fait connaître dans tout le pays, il condamne la fin de l’Union Soviétique et l’expansion de la corruption. Ce combat contre la corruption devient son thème favori si bien qu’il accède en juin 1993 à la présidence d’une commission parlementaire spéciale ad hoc, ayant la réputation d’« être un homme honnête et audacieux, qui n’avait pas peur des supérieurs (p. 57) ».

L’éclatante victoire de 1994

Le 15 mars 1994, le Soviet suprême biélorusse adopte une nouvelle constitution largement inspirée de la constitution de la Ve République française puisque Robert Badinter et ses juristes hexagonaux ont apporté leur savoir-faire aux nouveaux États d’Europe centrale et orientale. La Constitution biélorusse accorde de larges pouvoirs au président de la République élu au suffrage universel direct. L’élection est prévue pour le 23 juin 1994 avec, le cas échéant, un second tour, le 10 juillet suivant.

La Biélorussie traverse à ce moment une terrible crise économique. La production chute de 35 % et l’inflation mensuelle est de 40 à 50 %. Premier ministre en exercice et homme fort du pays, Viatcheslav Kebitch fait figure de favori.

Bénéficiaire d’une notoriété nationale, Alexandre Loukachenko annonce sa candidature à la présidence de la République. Or, « au début de sa campagne, Loukachenko ne jouissait d’aucun soutien de l’appareil d’État ni de celui d’aucun parti (p. 70) ». Ses collègues députés sont moqueurs d’autant que pour que sa candidature soit validée, il doit rassembler le parrainage de 100 000 citoyens. Les journalistes pensent qu’il ne les obtiendra pas. Mais ils ignorent que « cet acteur de talent […] sent bien son auditoire. Il dépasse de loin tous les autres politiques pour ce qui est de savoir conquérir un électorat (p. 28) ». « En vingt jours, Loukachenko collecta 177 000 signatures ! (p. 70) ».

Outre Kebitch et lui, quatre autres concurrents briguent la nouvelle fonction présidentielle. Alexandre Loukachenko se distingue de ses adversaires par une campagne radicale et populiste. Il s’élève contre la corruption, la cleptocratie et les thèses néo-libérales. Au cours de la campagne électorale, « les sondages montraient que la majorité de la population était pour une approche égalitaire et se prononçait contre “ le marché ” (p. 73) ». Valeri Karbalevitch ajoute même que « dès le début des réformes, la Biélorussie fut une “ Vendée anti-perestroïkiste ”, l’un des centres de l’opposition à la politique de Gorbatchev (p. 67) ». Le terrain est favorable à l’anti-libéralisme conséquent.

« S’il a tiré profit d’un concours de circonstances extraordinaires en arrivant au bon endroit et au bon moment, notre “ héros ” possède un talent politique inné, il faut bien le reconnaître. Les experts, les hommes politiques et les journalistes qui étudient le phénomène Loukachenko lui prêtent une intuition politique aiguë. Selon eux, il dispose d’un instinct naturel qui lui permet d’aller dans la bonne direction et de percevoir très tôt les menaces potentielles. Pour un leader populiste, il est très important de “ sentir ” son peuple et d’en reproduire les archétypes profonds de l’esprit national et à exprimer la voix intérieure de ses électeurs (p. 132). » Rapidement, en dépit d’un système médiatique aux ordres qui le dénigrent, Alexandre Loukachenko parvient à faire jeu égal avec le Premier ministre dans les intentions de vote. Son discours contestataire attire l’intérêt de l’opinion. « La société étant déçue par les uns et les autres, il espérait s’imposer comme troisième force : “ Ni avec la gauche, ni avec la droite, mais avec le peuple ”, proclamait son tract (p. 74) ».

Au soir du premier tour avec une participation de 78,97 %, le « candidat du peuple » crée la surprise. Alexandre Loukachenko recueille 44,82 % des suffrage et est en tête dans 111 circonscriptions sur 118 ! « La province, et la campagne en particulier, l’avait soutenu avec un enthousiasme particulier. Ces résultats provoquèrent un véritable choc auprès de l’élite gouvernante qui fut incapable de s’en relever (p. 78). » Kebitch se qualifie pour le second tour avec 17,33 %. Quinze jours plus tard, alors que la participation baisse à 70,6 %, Alexandre Loukachenko remporte l’élection par 80,34 % contre Kebitch qui ne récolte que 14,70 %. Le nouveau président est investi le 20 juillet 1994.

Il accède à la présidence dans des circonstances économiques dramatiques : la production nationale se contracte de 32 %, le taux d’inflation est de 53 % et le revenu de la population diminue de 23 %. La victoire du nouveau président exprime un profond mécontentement populaire. « La “ révolution populaire ” biélorusse avait un caractère à la fois anti-nomenklaturiste et anti-bourgeois : le peuple acclamait celui qui se dressait passionnément contre la nomenklatura et le business (p. 79). » Une demande de « troisième voie » transparaissait auprès des électeurs minés par la crise et l’incurie gouvernementale.

Le nouveau président avait un gigantesque défi à relever : fonder un État respecté et protecteur du peuple. D’autres auraient tergiversé, puis reculé sous les pressions. Pas Alexandre Loukachenko qui affronta les difficultés avec une rare détermination.

Une révolution « populiste », anti-libérale et anti-bourgeoise

« Nous devons être les premiers en Europe et dans le monde à créer un État pour le peuple », s’exclame le nouveau président. Depuis 1994, avec patience, la Biélorussie édifie un État digne de ce nom et non point une structure infestée par des groupes financiers anonymes. Il n’en fallait pas plus pour que l’Occident décadent « s’en prend à Loukachenko parce qu’il a démontré le succès économique du modèle nationaliste social, ou de ce qu’il appelle le modèle du “ marché social ” par opposition au capitalisme libertaire (2) ». C’est d’ailleurs dans cet état d’esprit que « ses premières prises de parole manifestent […] un enthousiasme sincère, un véritable désir d’aider le peuple et de sortir le pays de la crise (p. 83) ». Par conséquent, son anti-libéralisme foncier « s’appuie sur la partie la plus conservatrice et passive de la société : les retraités, les allocataires de minima sociaux, les paysans. des catégories sociales opposées à la démocratie et au marché (p. 264) ». Ainsi, pour le plus grand regret de Karbalevitch, la Biélorussie ne sanctifie-t-elle pas les sacro-saintes lois du marché. En 2007, le président biélorusse déclarait : « Ce n’est pas moi qui vous ai conduits vers ce marché démentiel ! Moi, je le hais de tout mon cœur, de toute mon âme. » Quelques années auparavant, en 2002, il estimait avec raison que « nous partons ici du fait que la mentalité, les traditions et le mode de vie des gens ne peut pas changer en une nuit. Faut-il les changer ? Il n’est pas possible de jeter des gens sans préparation dans l’abîme du marché (3) ». On ne retrouve pas cette sage prévoyance chez les dirigeants russes et ukrainiens qui paupérisent leurs populations dans les années 1990 – 2000. Dès sa campagne de 1994, Alexandre Loukachenko tonnait contre les ravages de la société de marché. « Quand Loukachenko est arrivé au pouvoir, il avait deux options : libéraliser le pays ou obtenir de la Russie ce qu’elle avait toujours donné. Les usines s’étaient arrêtées, la pauvreté augmentait. La libéralisation n’était pas envisageable pour la bonne raison que tout le capital aurait été détenu aux mains des Russes : il a donc opté pour une économie d’État (4). »

L’État biélorusse agit par conséquent en État stratège dans les affaires économiques. Bien entendu, Karbalevitch se scandalise que « c’est l’État qui définit ce dont les personnes ont besoin (p. 267) ». En Occident, ce sont les groupes privées, souvent transnationaux, qui imposent leurs volontés aux citoyens au moyen d’une incroyable propagande publicitaire. Dans sa préface très nuancée, Stéphane Chmelevsky, ambassadeur de France à Minsk de 2002 à 2006, signale une « publicité discrète et maîtrisée (p. 14) » dans les rues des grandes villes. La Biélorussie résiste à l’emprise spectaculaire de la marchandise. Les « casseurs de pub » du métro parisien le rêvaient; le Président Loukachenko l’a fait !

Les autorités biélorusses savent oser quand il s’agit de défendre des entreprises ou des activités nationales majeures. Si les circonstances l’exigent, elles peuvent nationaliser. Arnaud Montebourg, le ministre français du Redressement productif et naguère chantre de la démondialisation, l’a rêvé, Alexandre Loukachenko l’a fait. Montebourg devrait s’en inspirer et aller à Minsk, là où on n’abdique pas la volonté politique… « À rebours de ce qui semblait la logique politique, Loukachenko n’a pas eu peur de passer pour un rétrograde. Il a choisi de conserver l’essentiel des mécanismes et institutions du système soviétique, et prouvé qu’il n’était pas impossible d’arrêter la course du temps et de renverser le mouvement de l’histoire (p. 28). » Le président biélorusse appartient à une tradition politique spécifique, les « étatistes ». Pour lui, « l’État doit être puissant, honnête et dirigé de manière compétente, parce que l’alternative, c’est le contrôle oligarchique et la substitution du droit privé au droit public. L’État se comporte en protecteur de son peuple – ce qui est une idée originale à une époque où les élites occidentales ont systématiquement sapé les intérêts de leur propre peuple, en particulier en matière d’immigration (5) ».

Il est clair qu’en Biélorussie, dit Evgueniï, un Biélorusse de 29 ans, consultant dans une société de conseil et vivant à Moscou depuis 2001, « l’essentiel pour [ses parents] est qu’ils vivent mieux que dans les années 90. La Biélorussie est une Corée du Nord, mais avec des frontières ouvertes. Si quelque chose te déplaît, tu peux facilement en partir (6) ». Il est facile d’imaginer que la Biélorussie serait un pays-prison. C’est faux ! Un Européen habitué au libre passage des frontières de l’Espace Schengen peut être déstabilisé par l’examen attentif et minutieux de ses documents officiels à la douane. La République de Biélorussie a compris la nécessité de maîtriser et de réguler les admissions étrangères. C’est un bel exemple de « société fermée » qui ne peut qu’agacer la caste libre-échangiste, mondialiste et sans-papiériste (7).

Anti-libérale et anti-mondialiste (la Biélorussie n’appartient pas par bonheur à l’O.M.C.), la politique économique d’Alexandre Loukachenko présente une remarquable originalité.

Une troisième voie économique ?

Dans la décennie 2000, l’économie étatisée et nationalisée n’a pas heurté les investisseurs étrangers, russes en particulier. Des rapports d’organismes économiques internationaux mentionnent la Biélorussie comme un « Tigre slave » en référence au « Dragon celtique », l’Irlande, et les N.P.I. (nouveaux pays industrialisés) asiatiques des décennies 1970 – 1980 (Corée du Sud, Taïwan, Hong Kong) (8).

L’économie marchande se développe avec des restrictions précises. L’État biélorusse facilite la constitution d’unions corporatives (Fédération des syndicats, Union des femmes…) qu’on aurait pu appeler ailleurs en d’autres temps des « syndicats nationaux ». Ces unions sont les actrices principales d’une économie sociale et solidaire de proximité. « L’État est occupé principalement à mobiliser et à redistribuer les ressources entre les cellules sociales, militaires et productives primitives, appelées clusters (9). » Dans ce contexte holistique dans lequel les intérêts nationaux et du peuple passent en priorité, les forces de l’Argent sont sévèrement contenues. Zélote défenseur de la société libérale de marché totalitaire dans laquelle on crève aisément de faim, Valeri Karbalevitch s’offusque que « Loukachenko veut faire des banques des outils au service de sa politique […]. Par conséquent, les autorités obligent les banques à financer des programmes d’État (construction de logements et d’« agrovilles », etc.) et à soutenir des entreprises non rentables au détriment de leurs intérêts (p. 278) ». Alexandre Loukachenko démontre que la Finance, cet « ennemi sans visage » selon François Hollande, peut être vaincue. Notre Flanby normal devrait lui aussi effectuer un stage semestriel à Minsk… de véritables campagnes de désinformation, et cette biographie en est une preuve supplémentaire, se déroulent en Occident contre la Biélorussie et son chef.

« Sur quoi se fonde le leadership de Loukachenko, s’interroge Matthew Raphael Johnson ? La réponse est : l’idée “ sociale nationaliste et d’un marché social ”. La doctrine officielle biélorusse sur le développement dit ceci :

“La Biélorussie a choisi de suivre la route du développement évolutif, et rejeté les dispositions du Fonds monétaire international comme thérapie de choc et privatisations à tout va. Après plusieurs années de travail créatif, le modèle biélorusse de développement socio-économique a été mis en place : un modèle qui réunit les avantages de l’économie de marché et une protection sociale efficace. Notre concept de développement a été élaboré en conformité avec la continuité historique et les traditions du peuple. Ce modèle biélorusse a pour but d’améliorer la base économique existante plutôt que de provoquer une cassure révolutionnaire de l’ancien système. Le modèle économique biélorusse comporte les éléments de continuité dans le fonctionnement des institutions d’État partout où il s’est révélé efficace. ”

En d’autres termes, la vision qui est celle de Loukachenko ici, est celle d’une “ troisième voie ” entre le socialisme et le capitalisme. Elle retient ce qui est bon dans l’économie de marché mais maintient l’idée d’un État fort qui s’assure qu’une certaine croissance économique ne bénéficie pas uniquement à quelques personnes bien placées. Ce que marxisme et capitalisme ont en commun ce sont leurs résultats : inégalité totale devant le pouvoir, devant la richesse et devant l’accès. Qu’il s’agisse du parti ou de la classe des oligarques, ces systèmes modernes et matérialistes ne servent guère à autre chose qu’à des transferts massifs de richesse de l’homme qui travaille vers l’oligarque. Que ces oligarques prétendent travailler “ pour le peuple ”, “ pour le parti ” ou “ pour la liberté de l’Amérique ” ne change rien. Le résultat est exactement le même (10). » Pour contrecarrer cette assertion judicieuse, Karbalevitch en vient à recourir aux rapports annuels de la Heritage Foundation et du Wall Street Journal qui sont d’une fiabilité et d’une objectivité plus que douteuse.

La Biélorussie ose appliquer une « économie de mobilisation ». C’est possible parce que les Européens de l’Est conservent encore une attitude pré-moderne, voire non moderne, qui s’apparente à une faculté innée de privilégier le groupe. Quand bien même son étude concerne la Russie, l’ouvrage d’Alexandre P. Prokhorov éclaire notablement certains mécanismes psychiques collectifs des Biélorusses. Il remarque qu’« en Russie, le désir d’enrichissement ne joua pas dans l’activité humaine un rôle aussi efficace que cela doit l’être dans une économie normale de concurrence (11) ». À bien des égards, l’économie biélorusse se conformerait dans les faits à un anti-utilitarisme empirique.

En dépit donc d’une conjoncture mondiale mauvaise (crise profonde en Grèce, en Italie, en Espagne, aux États-Unis et en France), on remarque avec surprise que « les résultats de Loukachenko sont brillants. D’après les statistiques de la Banque mondiale mises à jour en 2010, la Biélorussie a évité la récession/dépression qui enserre l’Occident. Les banques biélorusses, la plupart propriétés de l’État, ont surpassé toutes les banques européennes en 2009. Ces banques propriétés de l’État ont augmenté leur capitalisation de près de 20 % au moment où le contribuable occidental était contraint de renflouer les banques mêmes qui ont condamné le gouvernement de Minsk. De 2001 à 2008, la croissance économique moyenne biélorusse a été de près de 9 %, ce qui équivaut à peu près à celle de la Chine. Tandis que les économies occidentales diminuent en 2010, l’économie biélorusse a augmenté d’environ 6 %, avec une augmentation de 10 % dans la production agricole et de 27 % dans les exportations. Le revenu réel, c’est-à-dire le revenu ajusté à l’inflation et au coût de la vie, a augmenté d’environ 7 % en 2010 (12) ».

Près de deux décennies de présidence Loukachenko ont façonné la vie quotidienne des Biélorusses. En la comparant à celle de leurs « grands frères » russes, les témoignages démentent l’image sulfureuses montée et diffusée par certaines officines subversives. « Nous avons des routes bien meilleures qu’en Russie, déclare Irina, une traductrice du chinois et de l’allemand de 24 ans, à Moscou depuis 2008, le système de santé publique est gratuit – nous n’apportons qu’une boîte de bonbons ou une bouteille de cognac pour que le médecin soit plus attentionné, rien de plus (13) ». Pour Georguiï, 22 ans, un étudiant en Master à l’Institut de droit européen, résident à Moscou depuis 2007, « il y a des différences de mentalité qui sont flagrantes. Les Biélorusses sont plus polis, et plus respectueux des lois : nous avons moins de corruption, moins de violation du code de la route. Minsk est une ville très propre. En ce qui concerne la vie de tous les jours, je dirais que le coût des produits de consommation courante sont à peu près les mêmes. Par contre, à Minsk, on peut louer un appartement pour à peu près 250 dollars. Les restaurants sont de deux voire trois fois moins chers, et les services comme le transport ou Internet sont eux aussi moins coûteux (14) ». Certes, « la Biélorussie a une économie quarante fois moins importante que la Russie. La République s’appuie sur quatre piliers : l’achat d’énergie russe à moindre prix, l’accès ouvert au marché russe, une économie gérée à 82 % par l’État et un marché fermé [vingt-deux restrictions existent sur les produits russes à l’importation, N.D.L.R. du Courrier de la Russie] (15) ».

La forte homogénéité ethnique de la Biélorussie ne joue-t-elle pas aussi un rôle dans le maintien de ce sens commun relevé par ces deux Biélorusses de Moscou ? La Russie est une fédération d’espaces multi-ethniques et pluri-religieux, d’où d’inévitables tensions réglées par l’État, incarnation de la majorité russo-slave. Si la Biélorussie accueille des immigrés chinois et installe dans le Sud des familles venues d’Asie Centrale, la cohésion slave perdure avec 81,2 % de Biélorusses, 11,4 % de Russes, 3,9 % de Polonais et 2,4 % d’Ukrainiens ! Il importe de ne pas négliger ce facteur bien souvent ignoré pour des motifs politiquement corrects.

L’auteur de cette biographie ironise qu’« en Biélorussie, l’agriculture est considérée comme une “ branche stratégique ” et la sécurité alimentaire est la grande priorité du régime. Elle mobilise 12 % du budget de l’État, alors que ce chiffre ne dépasse pas 3 à 4 % dans les pays développés. […] À l’époque postindustrielle de l’information, faire, de cette façon, de l’agriculture la priorité nationale est contraire à la logique du développement mondial (pp. 276 – 277) ». Pourquoi ? En cas de disette ou de famine, le geek mangera-t-il ses clefs U.S.B. ? En pariant au contraire sur l’agriculture, véritable « arme nucléaire verte du XXIe siècle », Alexandre Loukachenko est un visionnaire génial. outre des considérations géostratégiques sur la souveraineté alimentaire et l’auto-suffisance agricole, ce grand intérêt pour l’agriculture explique que « la nourriture chez nous est meilleure, le contrôle de qualité y est extraordinaire, déclare Irina. Ici [à Moscou], les produits laitiers, la viande, les légumes… C’est immangeable ! Ma mère m’envoie toutes les deux semaines un colis par le train avec des produits biélorusses (16) ». Échappant aux industries agro-alimentaires, les Biélorusses n’auraient donc pas la chance de manger du bœuf au cheval en attendant les savoureux légumes aux O.G.M.

Valeri Karbalevitch s’inquiète du « bas niveau de consommation (p. 264) ». Or la consommation n’est jamais la panacée idéale. Elle détruit lentement le tissu social alors que « les Biélorusses sont de meilleurs gens, affirme Evgueniï, les familles sont plus soudées. Ici [à Moscou] tout le monde se fiche de tout le monde, et les liens familiaux sont assez formels (17) ».

Une conception schmittienne de l’État

Il faut se demander si, dans sa jeunesse, le président Loukachenko a lu Le Prince de Machiavel et La psychologie des foules de Gustave Le Bon ainsi que les écrits du plus grand penseur allemand du politique du XXe siècle, Carl Schmitt, tant il paraît évident qu’il en est leur plus brillant praticien. « Le leader biélorusse souligne toujours son lien de sang avec le peuple, persuadé qu’il est le seul homme politique qui comprend les problèmes des gens ordinaires, qui se soucie d’eux et exprime leurs intérêts (p. 149). » On a vu que « dès qu’il a été élu, Loukachenko a promu l’idée d’un État fort, seul capable d’instaurer “ un ordre de fer ” (p. 193) ». Il remplace par exemple les exécutifs locaux élus par « une “ verticale ” de l’exécutif – un système de dépendance directe, par le jeu des nominations – qui renforçait le pouvoir présidentiel (p. 87) ». Son objectif est d’édifier des institutions saines et efficace parce qu’il « a probablement le désir sincère que les fonctionnaires servent les gens (p. 196) ».

Pour cela, dès août 1994, il affronte le Parlement et demande aux citoyens de trancher le contentieux par référendum. Le 14 mars 1995, il soumet à la décision du peuple quatre questions qui sont un triomphe pour lui : 83 % des électeurs approuvent que le russe devienne langue officielle de la Biélorussie, 75 % entérine les nouvelles armoiries (et donc le nouveau drapeau national), 82 % accepte une intégration avec la Russie et 78 % avalise la possibilité par le Président de dissoudre le Soviet suprême. Aigri, Karbalevitch commente « ces résultats, qui démontraient l’immaturité de l’État national biélorusse, vinrent confirmer que la population était nostalgique de l’U.R.S.S. (p. 93) ». Il est toujours plaisant de voir les donneurs de leçons démocrates exprimer leur rage quand le peuple va à l’encontre de leurs désirs pathologiques…

Afin de contourner les blocages institutionnels, le Président Loukachenko organise, le 24 novembre 1996, un nouveau référendum à cinq questions. Une fois encore, le peuple accorde toute sa confiance à son Batka : 70,5 % entérine la nouvelle Constitution; 69,9 % rejette la possibilité de rétablir les exécutifs locaux élus; 65,9 % récuse les financements administratifs; 82,9 % refuse le droit de vente illimité des terres et, enfin, 80,4 % maintient la peine de mort. En 2004, un autre référendum abroge la limitation du nombre de mandats présidentiels. Pour Karbalevitch, « le référendum marqua le seuil du changement de l’idéologie d’État. Ainsi, l’unité slave – autrement dit, le panslavisme – supplanta la renaissance nationale et devint l’idéologie dominante (p. 94) ». La renaissance du panslavisme n’est ni fortuite ni futile. C’est un pilier fondateur de la politique du président Loukachenko qui, le 12 avril 1995, lançait : « On regarde la Biélorussie comme le sauveur de la civilisation slave, et nous devons en effet sauver cette civilisation ! ». Le volontarisme panslaviste commence à avoir une résonance extérieure. Depuis le début de l’année, la Bulgarie connaît de graves troubles politiques. Des manifestations gigantesques ont provoqué la démission du gouvernement de centre-droit, le 20 février 2013. Les manifestants ont des revendications qui « ont jeté un froid au sein de l’intelligentsia bulgare. “ Leur modèle social semble osciller entre la Libye de Kadhafi et la Biélorussie ”, s’énerve Konstantin Pavlov, auteur d’un blogue politique très lu dans le pays (18) ». Verra-t-on bientôt une exportation du modèle biélorusse ? Il faut l’espérer pour l’avenir viril de l’Europe.

En bon larbin de la démocratie illusoire du marché, Karbalevitch juge le référendum comme un procédé non-démocratique et populiste… Il s’élève en outre contre l’usage du vote anticipé. Or ces maîtres, les États-Unis, le pratiquent très largement. Lors de la présidentielle de 2012, Barack Obama vota par anticipation à Chicago fin octobre ! Les conditions de vote aux États-Unis sont bien plus aléatoires qu’en Biélorussie, mais, obsédé par le mirage yankee, l’auteur ne souhaite pas le savoir. À tort, car il apprendrait que John F. Kennedy en 1960 et George W. Bush en 2000 ont gagné à la suite de fraudes monstrueuses orchestrées pour l’un par la maffia et, pour l’autre, par des clans du complexe militaro-industriel. Quant aux bourrages des urnes, ils existent aussi en France à Hénin-Beaumont ou à Marseille.

Prenant prétexte que depuis 1999, les O.N.G. sont strictement surveillées par les autorités biélorusses qui connaissent leur rôle frauduleux et subversif, Karbalevitch décrit une Biélorussie qui serait… totalitaire. Dans la même veine mensongère, l’auteur dénonce et la forte criminalité qui y régnerait et de supposés liens établis entre la pègre et l’État. Ne sait-il pas que de telles relations sont nécessaires afin de contenir dans un périmètre défini les activités illégales ? Ignore-t-il qu’au Japon, les Yakuza sont un élément essentiel de la société civile ? Où est-il le plus dangereux de se promener le soir, dans une rue de Minsk ou dans les quartiers Nord de Marseille ? D’ailleurs, quand on consulte la page « Conseils aux voyageurs » du ministère français des Affaires étrangères, on lit que « la police est bien assurée à Minsk, comme à Grodno, Brest, Gomel, Moguilev et Vitebsk, il est cependant recommandé, comme partout ailleurs, de ne pas faire étalage d’objets de valeur ou d’argent liquide en public (19). »

Dans la même veine outrancière, l’auteur attaque une justice qui ne serait pas indépendante. Et en France alors ? Avec une mauvaise foi consommée, Karbalevitch accuse Alexandre Loukachenko de rejeter « complètement l’idée d’un pouvoir judiciaire indépendant (p. 209) ». La Biélorussie a plutôt la chance de ne pas pâtir d’un gouvernement irresponsable des juges, cette lubie pour esprits naïfs. Ne se soumettant à aucune décision d’une pseudo-morale droit-de-l’hommesque, elle demeure l’ultime État européen à mépriser les arrêts de la Cour européenne des droits de l’homme de Strasbourg et d’appliquer la peine de mort. Sur ce sujet, l’auteur montre son arrogance à l’égard du choix souverain des Biélorusses pour la peine capitale. « Si tous les États européens ont proclamé l’abolition de la peine de mort par un vote parlementaire, évitent ainsi de soumettre au verdict des urnes cette décision au caractère très délicat, Loukachenko choisit pour sa part, en 1996, la voie référendaire et obtient le soutien de la majorité de la population pour le maintien de la peine capitale (pp. 133 – 134). » Où va-t-on si le peuple se met à prendre des décisions à la place de ses élus corrompus et incompétents ? Et puis, qui est le plus démocrate ? Le président Loukachenko ou bien Nicolas Sarközy qui viole le vote référendaire négatif du 29 mai 2005 ou la Cour suprême de Californie qui autorise l’homoconjugalité refusée par référendum ? Le président Loukachenko confirme par sa pratique l’énoncé célèbre de Carl Schmitt : « Est souverain celui qui décide lors d’une situation exceptionnelle (20). »

Un hyper-présidentialisme assumé

Agent d’influence de l’Occident et des États-Unis à Minsk, Valeri Karbalevitch voue un culte pour l’abject régime présidentiel étatsunien et son ineffable équilibre des pouvoirs qui démontrent maintenant leur grande inefficacité, voire leur perversité constitutionnelle. L’auteur déplore qu’« en Biélorussie, contrairement à ce qui se fait ailleurs de la façon la plus classique, on ne discute pas des mesures importantes de manière collégiale (p. 201) ». Les décisions collectifs prises au 10, Downing Street, à la Maison Blanche ou à l’Élysée sont bien connues des citoyens occidentaux à moins que l’auteur ne se réfère aux groupes d’influence et de pression (Bilderberg, Trilatérale, Fabian Society, Le Siècle…).

Au pays d’Alexandre Loukachenko, le pouvoir « doit être monolithique […]. Et de proposer une conception politique originale : celle d’un “ tronc ” (le pouvoir présidentiel) d’où poussent des “ branches ” (les pouvoirs législatif et judiciaire). ce qui permit aux juristes biélorusses d’ironiser sur le mutant botanique biélorusse… (p. 192) ». À la place de l’auteur et de ces « juristes » de pacotille, plutôt que de ricaner bêtement, ils auraient du rechercher d’autres exemples de cette « mutation botanique ». Le 7 mars 2009, le président équatorien anti-libéral de gauche, Rafael Correa, déclarait que « le président de la République n’est pas seulement le chef du pouvoir exécutif. Il est le chef de tout l’État équatorien. Et l’État équatorien, c’est le pouvoir exécutif, le pouvoir législatif, le pouvoir judiciaire et le pouvoir électoral ! (21) » Karbalevitch rétorquerait que Correa ne sert pas Washington et qu’il incarne le « satrape de l’Équateur »… « S’il doit être évidemment entendu que l’autorité indivisible de l’État est confiée tout entière au Président par le peuple qui l’a élu, qu’il n’en existe aucune autre, ni ministérielle, ni civile, ni militaire, ni judiciaire, qui ne soit conférée et maintenue par lui… » proclame non pas Alexandre Loukachenko, mais… Charles de Gaulle en conférence de presse, le 31 janvier 1964. Sans le savoir, le président biélorusse suit les conseils du fondateur de la Ve République française parce qu’au cours de cette intervention, le président, seul détenteur de la légitimité de l’État, est présenté comme l’homme de la nation d’où procède tout autorité réelle.

Contrairement aux voisins fragilisés par des partis politiques fauteurs de divisions, la Biélorussie a écarté les partis sans les abolir ou les interdire. Il n’existe pas de parti loukachenkiste, ni a fortiori de parti unique. Avec une avance de deux décennies sur le mouvement anti-Système de l’Italien « Beppe » Grillo, Alexandre Loukachenko a compris la fin programmée des partis. Il a en revanche saisi l’influence majeure du pouvoir médiatique et s’en est assuré la maîtrise, car « les médias sont l’une des armes les plus puissantes du monde. Ils doivent donc être régulés comme n’importe quelle autre arme. Les élites des médias sont souvent oligarchiques et centralisées, et elles utilisent leur empire pour pouvoir contrôler les autres. Par conséquent, l’information médiatique libre doit être diversifiée et permettre l’exposition de divers points de vue. Ce qui est bien davantage le cas en Russie et en Biélorussie qu’aux États-Unis (22) ». Plutôt que travailler pour le privé, télévisions et radios dépendent du secteur public. En parallèle existe une vivace presse d’opposition qui prépare les esprits à une quelconque révolution colorée. Matthew Raphael Johnson rappelle que « ce n’est pas un hasard si le gros de son opposition américaine provient de l’Université de Harvard, en particulier de la faculté de droit, y compris de Yarik Kryovi, qui à un moment donné a travaillé pour la Radio Liberty, propriété de Soros, et a fait fonction d’avocat pour la Banque mondiale (23) ». Or c’est à Radio Liberty qu’officie aussi Karbalevitch !!!

Financée par les États-Unis, l’opposition biélorusse existe, mais demeure minoritaire. « L’organisme T.N.S. Global Research, basé à Londres, a sondé 10 000 Biélorusses à propos de leur président, constate Matthew Raphael Johnson. Le sondage a démontré la solide popularité de Loukachenko qui a obtenu près de 75 % à l’automne 2010. Par conséquent, les accusations selon lesquelles il aurait truqué les élections sont absurdes. Qui plus est, son opposition est fortement divisée, inefficace et profondément sceptique sur sa propre raison d’être (24). » Sans exagérer, on est plus libre en ces temps du politiquement correct à Minsk qu’à Paris, Los Angeles ou Londres. Est-ce en Biélorussie qu’interviennent des policiers dans les établissements scolaires ou que la vidéo-surveillance espionne la sortie des poubelles aux mauvaise heures ? Non, c’est au Texas et au Royaume-Uni (25).

Un parler vrai et libre

« La Biélorussie reste au travers de la gorge des Américains », a lancé une fois le Président Loukachenko qui aime provoquer. Maniant un sens de l’humour au troisième degré incompréhensible pour le Yankee d’adoption qu’est Karbalevitch, « le président biélorusse défie les usages en vigueur de la communauté internationale (p. 344) ». Sa libre parole tord les convenances diplomatiques compassées. « Son style est tout sauf politiquement correct. En Biélorussie, chacun s’est habitué à ce que le président tutoie tout le monde. […] Loukachenko ne modère jamais son expression et dit des choses imprononçables dans une société civilisée. Il profère facilement des grossièretés, comme beaucoup de ses électeurs dans la vie de tous les jours. Dans ce sens, il n’y a pas de différences entre le président et le peuple (p. 135) », assène avec un rare mépris à l’égard des Biélorusses qui votent si mal Karbalevitch. La Biélorussie et son peuple sont pour l’heure exemptés du puritanisme en vogue outre-Atlantique et qui pollue la planète entière.

Le Président Loukachenko ne fait pas dans la langue de bois. Il traite tour à tour la politique de Washington d’« idiotie » et l’entité pseudo-européenne manipulée depuis Bruxelles de « sauvagerie » et de « stupidité ». Quant aux membres de la Commission dite « européenne », ce sont des « imbéciles ». Des propos virils qui tranchent nettement avec les zombies politiciens de l’Ouest.

En avril 2001 à la télévision biélorusse, il s’attaquait à la multinationale de la malbouffe et du conditionnement psychique des enfants : « Ces Mac Donald’s sont comme des nœuds de vipères qui s’installent à nos carrefours ! Il est temps de manger biélorusse. Nous n’avons pas besoin de cette contagion chez nous ! » Il va de soi que le Président assume ses actes (et ses sentences bien senties), ce qui lui vaut d’être interdit de séjour en Occident ainsi que plus de cent trente hauts-fonctionnaires biélorusses. Étrange cette Union européenne qui refuse la venue d’hommes de qualité et accepte le déferlement massif des clandestins… Manque de chance pour cette U.E. néo-puritaine en triste état, le populisme fleurit, y compris en hiver, sur tout le Vieux Continent si bien qu’il serait un jour possible que la Biélorusse et son excellent président prennent la tête d’une Ligue européenne des États populistes avec la Hongrie d’Orban, la Grèce de l’Aube dorée, l’Italie grilliniste… En attendant la concrétisation de cette possibilité, Minsk s’ouvre aux puissances émergentes du Sud.

Une diplomatie révolutionnaire anti-mondialiste

N’adhérant à aucun corset économique mondialiste et libre-échangiste libéral, le gouvernement de Minsk en récuse aussi la version judiciaire en niant l’existence de la Cour pénal internationale et du Tribunal pénal international pour l’ex-Yougoslavie. En bon larbin des États-Unis, Karbalevitch lui en fait le reproche. « Sous prétexte que chaque pays a la liberté de choisir sa voie de développement, Loukachenko défend de facto le droit des pays voyous et leurs dirigeants autoritaires à ne pas se conformer aux normes internationales, et à mener leur politique intérieure et étrangère à leur guise (pp. 345 – 346). » On retrouve la rhétorique habituelle des néo-conservateurs occidentalistes et bellicistes. En réalité, les seuls vrais États voyous s’appellent les États-Unis, le Royaume-Uni, Israël, la République hexagonale, l’Allemagne fédérale dégénérée, la Suède, les Pays-Bas, l’Arabie Saoudite et le Qatar.

Au printemps 1999, méprisant un danger certain, Alexandre Loukachenko se rend à Belgrade réconforter le président Slobodan Milosevic agressé par l’organisation terroriste appelée O.T.A.N. « Il faut être capable d’un sang-froid peu ordinaire et être prêt à mettre son avenir en jeu (p. 152). » Il soutient ensuite les martyrs de la liberté des peuples que sont Saddam Hussein et Mouammar Kadhafi. Il contribue à devenir aux côtés de feu Hugo Chavez et du président bolivien Evo Morales « le champion de la résistance à l’Occident (p. 315) ».

Dans cette perspective d’affrontement géopolitique d’ampleur planétaire, cet « orthodoxe athée » souhaitait riposter en mars 1997 au prochain élargissement de l’Alliance Atlantique totalitaire par la formation d’un bloc continental Minsk – Moscou – Pékin. Quelques mois plus tard, il réitéra sa suggestion en s’adressant à la Russie, à la Chine, à l’Inde, à l’Iran et à des États arabes : « C’est ensemble que nous créerons un contrepoids au bloc de l’O.T.A.N. et des États-Unis. C’est nécessaire […] pour sauver la civilisation, sauver la planète. » Face à l’Occident barbare, la Biélorussie d’Alexandre Loukachenko incarne une anti-barbarie conséquente.

Le président de la Biélorussie insiste beaucoup sur la renaissance du panslavisme et d’une Orthodoxie plus politique. « En opposition au catholicisme, il exalte la religion orthodoxe qui sert de base spirituelle à l’unité des Slaves de l’Est (p. 309). » Nonobstant un enclavement préjudiciable, l’absence de toute façade maritime et une taille démographique modeste (une dizaine de millions d’habitants), la Biélorussie ne craint pas grâce à son chef d’État énergique de participer au Grand Jeu des puissances. Elle a aussi su s’adosser à la Russie d’autant qu’auprès des Russes, « le président biélorusse mène sa barque avec brio (p. 311) ».

Minsk – Moscou : des relations tourmentées

L’essai Réflexions à l’Est évoque longuement les différentes tentatives d’Alexandre Loukachenko d’assumer la direction d’un ensemble commun Russie – Biélorussie dans la décennie 1990. L’ouvrage de Karbalevitch, en particulier le chapitre 10 (pp. 295 à 337), en confirme l’analyse et y apporte des détails supplémentaires. En 1994, la victoire du président Loukachenko est bien reçue en Russie. « Son charisme et son populisme y furent accueillis avec enthousiasme, non seulement par le petit peuple, mais aussi par une partie des élites : il fut ovationné par des hauts fonctionnaires et des académiciens (p. 300). » « Dès 1995, il laisse entrevoir qu’il désire ardemment exercer la présidence de l’État uni (p. 299). »

Au chaos intérieur, politique, social et économique, russe et à l’absence de volonté d’Eltsine, « le président biélorusse s’assure une présence quasi permanente dans les médias russes en leur accordant davantage d’entretiens que n’importe quel politique russe. L’ambassade biélorusse à Moscou organise plusieurs voyages de journalistes en Biélorussie (p. 312) ». De 1996 à 2001, Alexandre Loukachenko visite de nombreuses régions de la Fédération, rencontre leurs gouverneurs et « se positionne clairement comme un futur candidat à l’élection présidentielle, qui doit avoir lieu en 2000 (p. 313) ». En 1999, il est même prêt à fusionner son État avec la Russie afin d’obtenir une citoyenneté commune apte à lui ouvrir les portes du Kremlin.

Mais son dessein se heurte à l’entourage familial, maffieux et libéral d’Eltsine. « L’etablishment russe ne voulait pas que le “ frangin slave ” vienne perturber la campagne présidentielle de 2000 : il devenait un candidat sérieux. À Moscou, on craignait que Loukachenko ne casse le système qui s’était mis en place avec Boris Eltsine, pour instaurer un régime de type biélorusse. Malgré ses visées impérialistes, l’élite russe a donc sauvé la souveraineté biélorusse. Quel paradoxe ! (p. 322). » À l’été 1999, cet entourage présidentiel promeut Vladimir Poutine. Son arrivée modifie les relations russo-biélorusses par un net refroidissement. Le nouvel homme fort de la Russie veut soumettre son homologue biélorusse. Sans succès. Au contraire ! Dans le même temps, certains politiciens russes comme cherche à réduire au silence le second. Entre 2001 et 2002, certains politiciens russes tels Boris Nemtsov, de l’Union des forces de droite, un groupuscule libéral et atlantiste, se comportent en Biélorussie comme si c’était une colonie. À l’instar de Nemtsov, ces bradeurs de la civilisation slave sont expulsés manu militari.

En 2006, Moscou cherche encore à inféoder la Biélorussie récalcitrante. En pleine guerre du gaz russo-biélorusse, le président Loukachenko, exaspéré par cette morgue, offre à l’Ukraine alors « Orange » une entente renforcée destinée à contrer un danger russe avéré… Contre les menaces sérieuses d’annexion rampante voulue par Moscou, Minsk en vient à menacer de transformer la Biélorussie, vieille terre de guerre des partisans, en une nouvelle Tchétchénie mille fois pire… À l’été 2010, la chaîne russe N.T.V. diffuse « Le Parrain paternel », un « documentaire » inqualifiable de sottises qui vise à déstabiliser la présidence biélorusse. Sans succès, heureusement…

Depuis 2011 – 2012, on observe un apaisement des tensions russo-biélorusses, car Vladimir Poutine sait pouvoir compter sur l’appui international de la Biélorussie d’autant qu’ils affrontent les mêmes ennemis (financiers véreux, Pussy Riot, FemHaine…). Il est d’ailleurs intéressant d’observer que la directrice de la collection dans laquelle sort ce livre, Galia Ackerman, collaboratrice au Monde, consacre tout un ouvrage aux FemHaine. La guerre culturelle est patente. Que ces mégères, jeunes et moins jeunes, sachent bien que nous la conduirons sur tous les fronts sans pitié…

Alexandre Loukachenko demeure un recours possible, quoique ténu, pour des Russes déboussolés. En effet, la Russie s’engage malheureusement dans une direction complaisante envers l’Occident en espérant l’amadouer. Marie Jégo rapporte que « face à la déliquescence institutionnelle ambiante, le gouvernement russe, conseillé par Goldman Sachs, ambitionne de faire de Moscou un centre financier international. Les banquiers se frottent les mains à l’idée d’acheter de la dette russe (l’endettement extérieur public est très faible, soit 11 % du P.I.B.) (26) ».

L’actuelle dyarchie russe entre Vladimir Poutine et son Premier ministre, Dmitri Medvedev, un familier des réunions de Davos, ferait l’objet de dissensions internes possibles. Des enquêtes d’opinion révèlent l’impopularité croissante de la politique gouvernementale menée par Medvedev. Plus proche des cénacles occidentalistes, celui-ci qui semble avoir pour modèle historique Catherine II la Grande qui parvint au pouvoir en 1762 après l’élimination de son mari germanophile, le tsar Pierre III, pourrait un jour prendre l’initiative de « normaliser » la Russie (c’est-à-dire de l’assujettir à l’Occident) en écartant son mentor Poutine. Outre les précédents de 1762 et de 1801 qui vit l’assassinat du tsar Paul Ier par des éléments anglophiles, il existe un exemple tunisien désormais ancien. En 1987, le Premier ministre Ben Ali destitua le vieux président Habib Bourguiba pour un motif sanitaire et s’empara de la présidence. Dans ce cas très hypothétique, Alexandre Loukachenko retrouverait peut-être une chance réelle de peser à nouveau sur le destin de la Russie et du bloc eurasien en voie de formation.

L’ouvrage de Valeri Karbalevitch appartient à une collection particulière de l’éditeur, « Les moutons noirs », qui est financée par Pierre Bergé. On comprend mieux maintient le violent réquisitoire contre le président Loukachenko quand on sait l’extrême nuisance de ce milliardaire hexagonal, ancien parrain de Globe et de S.O.S. – Racisme. Les prochains titres ne dénonceront pas ces véritables ennemis des peuples que sont, outre Pierre Bergé lui-même, George Soros, Boris Bérézovski qui vient de disparaître, le groupe de Bilderberg, la Commission Trilatérale ou les entités mondialistes occultes.

En 2010 – 2011, Alain Soral et son mouvement Égalité et Réconciliation organisèrent une campagne réclamant « un Chavez à la française ». Il serait plus approprié d’exiger « un Loukachenko à la française », car l’ouvrage partial de Karbalevitch présente l’unique mérite de montrer un dirigeant européen d’exception. Loin d’être un « mouton noir », Alexandre Loukachenko est un grand renard, le « Renard de Biélorussie » !

Georges Feltin-Tracol

Notes

1 : Le présent article corrige, modifie et approfondit les précédentes contributions de l’auteur des lignes, en particulier les chapitres 8, 9, 14 et 15 de Réflexions à l’Est, Alexipharmaque, 2012, « Le diable de l’Europe et la troisième voie biélorusse », Salut public, n° 9, octobre 2012, et « La troisième voie biélorusse », conférence donnée au Local 92 à Paris, le 8 novembre 2012, qu’on peut écouter sur le site Troisième Voie et sur YouTube :

http://troisiemevoie.fr/4897-la-troisieme-voie-bielorusse-conference-de-georges-feltin-tracol-au-local/

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H4_ieJQJK1o

2 : Matthew Raphael Johnson, « La pensée politique d’Alexandre Loukachenko (Biélorussie) hors de la désinformation », mis en ligne sur Polémia, le 3 novembre 2011, et d’abord paru en anglais sur Occidental Observer, le 27 octobre 2011.

3 : cité par Matthew Raphael Johnson, art. cit.

4 : Andreï Soudaltsev, « Le sacrifice biélorusse face à l’Union douanière », entretien pour Le Courrier de la Russie mis en ligne le 28 octobre 2011.

5 : Matthew Raphael Johnson, art. cit.

6 : « Biélorussie, notre douleur », Le Courrier de la Russie, mis en ligne le 4 avril 2012.

7 : cf. Georges Feltin-Tracol, « Pour une société fermée », dans Orientations rebelles, Éditions d’Héligoland, 2009, pp. 97 – 100.

8 : cf. Laurent Blancy, « Le “ Tigre ” de Minsk », Rivarol, 19 février 2010.

9 : Alexandre P. Prokhorov, Le modèle russe de gouvernance, Cherche-Midi, coll. « Documents », Paris, 2011, p. 99. Un cluster désigne « un groupement autosuffisant composé d’unités homogènes ».

10 : Matthew Raphael Johnson, art. cit.

11 : Alexandre P. Prokhorov, op. cit., pp. 359 – 360.

12 : Matthew Raphael Johnson, art. cit.

13 : « Biélorussie, notre douleur », art. cit. L’accès aux soins est gratuit en Biélorussie, quelque soit le statut du patient (citoyen, résident ou touriste).

14 : Idem.

15 : Andreï Soudaltsev, art. cit.

16 : « Biélorussie, notre douleur », art. cit.

17 : Id.

18 : Alexandre Lévy, « Le suicide d’un activiste électrise la Bulgarie », Le Figaro, 5 mars 2013.

19 : « Conseils aux voyageurs », dernière mise à jour, le 19 octobre 2012 et information toujours valide le 4 mars 2013, cf. http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/conseils-aux-voyageurs/conseils-par-pays/bielorussie-12211/

Les seules consignes de sécurité sont alimentaires du fait des conséquences de la catastrophe nucléaire de Tchernobyl.

20 : Carl Schmitt, Théologie politique, Gallimard, 1988. On reprend ici la célèbre formule dans la traduction de Julien Freund, « Les lignes de force de la pensée politique de Carl Schmitt », Nouvelle École, n° 44, printemps 1987.

21 : cité par Le Figaro, 16 et 17 février 2013.

22 : Matthew Raphael Johnson, art. cit.

24 : Id.

25 : cf. Chris McGreal, « Au Texas, un bon élève est un élève fliqué », The Gardian, traduit dans Courrier International, 2 – 8 février 2012; Rose Claverie, « Les Britanniques espionnés en sortant leurs poubelles », Le Figaro, 23 août 2012

26 : Marie Jégo, « Lettre de Russie – Roulette russe : faites vos jeux ! », Le Monde, 1er mars 2013.

• Valeri Karbalevitch, Le satrape de Biélorussie. Alexandre Loukachenko, dernier tyran d’Europe, François Bourin Éditeur, coll. « Les moutons noirs », préface de Stéphane Chmelewsky, traduit du russe, adapté et annoté par Galia Ackerman, Paris, 2012, 442 p., 24 €.

Article printed from Europe Maxima: http://www.europemaxima.com

URL to article: http://www.europemaxima.com/?p=3005

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

A revolutionary imperial struggle against the Atlanticist Leviathan (aka the NWO)—the struggle to which Yockey gave his life—revolves around the formation of a Euro-Russian federation to fight the thalassocratic powers: les Anglos-Saxons incarnating the Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism—England and America—whose hedonist dictatorship of “creative destruction” was not the invention of maniacal Jews, but entirely homegrown, given that it was born at Runnymede; came of age with Henry VIII’s sacrileges, which turned Christianity into a religion of capitalism (Protestantism); and triumphed with the Whig Oligarchy that has dominated the Western world since 1789, when its Continental ideologues overthrew the French monarchy, representing a “Catholic” and regalian modernity.[13]

A revolutionary imperial struggle against the Atlanticist Leviathan (aka the NWO)—the struggle to which Yockey gave his life—revolves around the formation of a Euro-Russian federation to fight the thalassocratic powers: les Anglos-Saxons incarnating the Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism—England and America—whose hedonist dictatorship of “creative destruction” was not the invention of maniacal Jews, but entirely homegrown, given that it was born at Runnymede; came of age with Henry VIII’s sacrileges, which turned Christianity into a religion of capitalism (Protestantism); and triumphed with the Whig Oligarchy that has dominated the Western world since 1789, when its Continental ideologues overthrew the French monarchy, representing a “Catholic” and regalian modernity.[13]

José Antonio Primo de Rivera y Saenz de Heredia Marques de Estella or José Antonio (as he is more commonly called) was born on April 24, 1903 in Madrid to grow up in a healthy aristocratic family environment as the eldest son of General Miguel Primo de Rivera, who was the Leader of Spain from 1923 to 1930. His family was socially prominent in Andalusia, having intermarried with large landholders and merchants around Jerez de la Frontera. From his father José Antonio inherited the title marqués de Estella.

José Antonio Primo de Rivera y Saenz de Heredia Marques de Estella or José Antonio (as he is more commonly called) was born on April 24, 1903 in Madrid to grow up in a healthy aristocratic family environment as the eldest son of General Miguel Primo de Rivera, who was the Leader of Spain from 1923 to 1930. His family was socially prominent in Andalusia, having intermarried with large landholders and merchants around Jerez de la Frontera. From his father José Antonio inherited the title marqués de Estella.

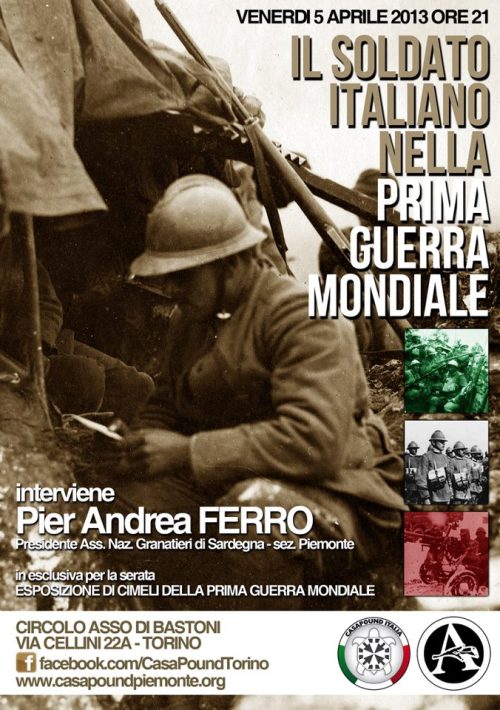

Cofundador del Comité d’Action de Défense des Belges à l’Áfrique (CADBA), constituído en julio de 1960, inmediatamente después de las violaciones de Leopoldvlile y de Thysville, de las que fueron víctmas los belgas de Congo y cofundador del Mouvement d’Action Civique que sucedió al CADBA, el belga JeanThiriart, en diciembre de 1960, lanzó la organización Jeune Europe, que durante varios meses será el principal sostén logístico y base de retaguardia de la OAS-Metro.

Cofundador del Comité d’Action de Défense des Belges à l’Áfrique (CADBA), constituído en julio de 1960, inmediatamente después de las violaciones de Leopoldvlile y de Thysville, de las que fueron víctmas los belgas de Congo y cofundador del Mouvement d’Action Civique que sucedió al CADBA, el belga JeanThiriart, en diciembre de 1960, lanzó la organización Jeune Europe, que durante varios meses será el principal sostén logístico y base de retaguardia de la OAS-Metro.

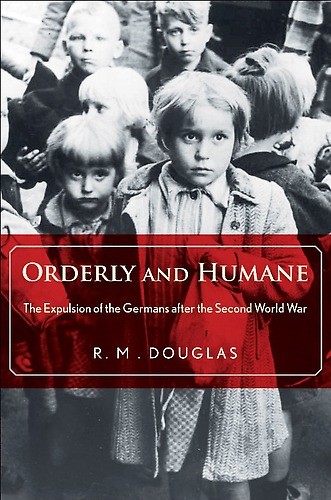

In December 1944 Winston Churchill announced to a startled House of Commons that the Allies had decided to carry out the largest forced population transfer -- or what is nowadays referred to as "ethnic cleansing" -- in human history.

In December 1944 Winston Churchill announced to a startled House of Commons that the Allies had decided to carry out the largest forced population transfer -- or what is nowadays referred to as "ethnic cleansing" -- in human history.  The regime for prisoners in many of these facilities was brutal, as Red Cross officials recorded, with beatings, rapes of female inmates, gruelling forced labour and starvation diets of 500-800 calories the order of the day. In violation of rarely-applied rules exempting the young from detention, children routinely were incarcerated, either alongside their parents or in designated children's camps. As the British Embassy in Belgrade reported in 1946, conditions for Germans "seem well down to Dachau standards."

The regime for prisoners in many of these facilities was brutal, as Red Cross officials recorded, with beatings, rapes of female inmates, gruelling forced labour and starvation diets of 500-800 calories the order of the day. In violation of rarely-applied rules exempting the young from detention, children routinely were incarcerated, either alongside their parents or in designated children's camps. As the British Embassy in Belgrade reported in 1946, conditions for Germans "seem well down to Dachau standards."

As the author points out, the Second World War did not end in 1945. In large parts of the continent, the contest lasted a lot longer as Polish, Ukrainian, Baltic and Greek partisans battled on in the mountains and forests of Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean. Some of these stories, such as the post-war travails of the Greeks, are well known to Western audiences, but the activities of the Lithuanian, Latvian and Estonian anti-Soviet "Forest Brothers" are not. Perhaps the most arresting fact in this compelling book is that the last Estonian guerrilla fighter, August Sabbe, was killed as late as 1978, trying to escape capture.

As the author points out, the Second World War did not end in 1945. In large parts of the continent, the contest lasted a lot longer as Polish, Ukrainian, Baltic and Greek partisans battled on in the mountains and forests of Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean. Some of these stories, such as the post-war travails of the Greeks, are well known to Western audiences, but the activities of the Lithuanian, Latvian and Estonian anti-Soviet "Forest Brothers" are not. Perhaps the most arresting fact in this compelling book is that the last Estonian guerrilla fighter, August Sabbe, was killed as late as 1978, trying to escape capture. Europe was also in political flux. The war had destroyed the standing of the old elites, and brought the Red Army into the heart of the continent. It was Soviet power, rather than the failure of the ancien regime as such, which underpinned the wave of Communist takeovers in Eastern Europe. Lowe describes the Romanian case in fascinating detail. Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Bulgaria all met broadly similar fates: red terror, arrests, expropriation of land and property, and executions. In Greece, the boot was on the other foot, as the right-wing government parlayed first British then American help into brutal victory over the communists. Lowe notes the "unpleasant symmetry" caused by Cold War imperatives without in any way denying that "the capitalist model of politics was self-evidently more inclusive, more democratic and ultimately more successful than Stalinist communism".

Europe was also in political flux. The war had destroyed the standing of the old elites, and brought the Red Army into the heart of the continent. It was Soviet power, rather than the failure of the ancien regime as such, which underpinned the wave of Communist takeovers in Eastern Europe. Lowe describes the Romanian case in fascinating detail. Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Bulgaria all met broadly similar fates: red terror, arrests, expropriation of land and property, and executions. In Greece, the boot was on the other foot, as the right-wing government parlayed first British then American help into brutal victory over the communists. Lowe notes the "unpleasant symmetry" caused by Cold War imperatives without in any way denying that "the capitalist model of politics was self-evidently more inclusive, more democratic and ultimately more successful than Stalinist communism".

Roger Griffin,

Roger Griffin,  Amongst the epiphanic modernists Griffin includes Nietzsche, Eliot, Joyce, Proust, van Gogh, Kandinsky, and Malevich, but perhaps the truth of Griffin’s argument is demonstrated by the man widely acknowledged as the greatest modern painter: Picasso. In his earlier cubist works, Picasso sought inspiration from the primitivism of African masks, and later in the archetypal Mediterranean symbols of horses and particularly bulls (which surprisingly Griffin doesn’t mention).

Amongst the epiphanic modernists Griffin includes Nietzsche, Eliot, Joyce, Proust, van Gogh, Kandinsky, and Malevich, but perhaps the truth of Griffin’s argument is demonstrated by the man widely acknowledged as the greatest modern painter: Picasso. In his earlier cubist works, Picasso sought inspiration from the primitivism of African masks, and later in the archetypal Mediterranean symbols of horses and particularly bulls (which surprisingly Griffin doesn’t mention).

The true heirs to Hegel’s universalism are Marx and his followers, who really believed that the dialectic would lead to universal freedom. Alexandre Kojève, Hegel’s greatest 20th-century Marxist interpreter, came to believe that both Communism and bourgeois capitalism/liberal democracy were paths to Hegel’s vision of universal freedom. After the collapse of communism, Kojève’s pupil Francis Fukuyama declared that bourgeois capitalism and liberal democracy would create what Kojève called the “universal homogeneous state,” the global political and economic order in which all men would be free.

The true heirs to Hegel’s universalism are Marx and his followers, who really believed that the dialectic would lead to universal freedom. Alexandre Kojève, Hegel’s greatest 20th-century Marxist interpreter, came to believe that both Communism and bourgeois capitalism/liberal democracy were paths to Hegel’s vision of universal freedom. After the collapse of communism, Kojève’s pupil Francis Fukuyama declared that bourgeois capitalism and liberal democracy would create what Kojève called the “universal homogeneous state,” the global political and economic order in which all men would be free.