Une révolution sous nos yeux

Ex: http://aristidebis.blogspot.com/

Les éditions du Toucan viennent de publier la traduction française du livre de Christopher Caldwell Reflexions on the revolution in Europe, sous le titre Une révolution sous nos yeux.

Je profite donc de cette occasion pour republier - cette fois d'un seul tenant - le compte-rendu que je lui avais consacré, et je vous encourage vivement à lire cet ouvrage et à en parler autour de vous. Ce livre mérite une large audience, et il se pourrait qu'il l'obtienne si chacun de nous y contribue un peu

.

.

Veritas odium parit

Lorsqu’Edmund Burke publia ses Réflexions sur la révolution en France, en 1790, peu de gens lui en furent reconnaissants et moins encore, sans doute, prirent au sérieux ses prévisions concernant la tournure que devaient prendre les événements. Annoncer ainsi les tempêtes qui allaient se déchaîner sur la France et sur l’Europe toute entière, au moment où la plupart des beaux esprits croyaient au contraire voir se lever l’aube radieuse de la liberté, ne pouvait être que le fait d’un réactionnaire furieux ou d’un esprit dérangé. Burke fut ainsi soupçonné de s’être secrètement converti au catholicisme et le bruit courut que son équilibre mental était atteint.

On ne saurait dire si Christopher Caldwell avait présent à l’esprit le sort réservé à l’ouvrage de Burke, et à son auteur, lorsqu’il choisit d’intituler son propre livre Réflexions sur la révolution en Europe. Mais, à coup sûr, Christopher Caldwell pense que la situation qu’il examine est porteuse d’autant de bouleversements et de déchirements que celle dont Burke entrevoyait trop bien les conséquences voici deux siècles. La « révolution » que Christopher Caldwell a en vue est indiquée avec toute la clarté nécessaire par le sous-titre de son livre : « L’immigration, L’islam, et l’Occident ». « L’Europe », écrit-il, « est devenue une société multiethnique dans un moment d’inattention » (p3). Ce sont les conséquences probables de cette « inattention » que Christopher Caldwell se propose d’examiner, et les conclusions auxquelles il parvient ne plairont ni à ceux qui les contesteront ni à ceux qui les accepteront. Que Christopher Caldwell soit un journaliste américain, écrivant pour des publications aussi notoirement « conservatrices » que The Weekly Standard ou le Financial Times, sera pour beaucoup une raison suffisante pour ignorer ses analyses. Ceux qui agiront ainsi le feront à leur propre détriment, car Christopher Caldwell connaît manifestement bien le sujet dont il traite et, s’il n’apporte pas d’éléments réellement nouveaux au dossier, le sérieux et l’intelligence de ses analyses pourraient bien faire de son ouvrage une référence en la matière.

***

Bien qu’il soit devenu presque nécessaire d’affirmer, en public, que les pays européens sont « depuis toujours » des pays d’immigration, nul n’ignore que cette affirmation est au moins à demi mensongère. Le phénomène auquel l’Europe est confrontée depuis bientôt un demi-siècle est celui d’une immigration extra européenne de masse intervenant en un temps relativement court, et ce phénomène là est incontestablement inédit. Ainsi, d’ici 2050, dans la plupart des pays européens, la population d’origine étrangère devrait représenter entre 20% et 32% de la population totale. Ce bouleversement démographique n’est pas dû seulement à l’arrivée massive et continue d’immigrants, mais aussi à la très faible natalité de la plupart des populations européennes. En 2008 le taux de fécondité global au sein de l’Union Européenne était de 1,6 enfants par femme. D’ici 2050 l’Union Européenne devrait donc avoir perdu une bonne centaine de millions d’habitants, hors immigration.

Le déclin sera plus ou moins marqué selon les pays, léger dans certains d’entre eux, comme la France, spectaculaire dans d’autres, comme l’Allemagne, l’Italie ou l’Espagne. Sur la base des tendances actuelles, ces trois derniers pays devraient ainsi avoir perdu entre un quart et un tiers de leur population actuelle en 2050. En 2100, et toujours sur la base des tendances actuelles, ces pays auront, pour ainsi dire, disparu. Les prévisions sont tout aussi sombres pour la plupart des pays d’Europe de l’Est. Si les européens de souche ne font plus guère d’enfants tel n’est pas le cas des populations immigrées qui rentrent en Europe et qui, bien souvent, conservent des taux de fécondité élevés même longtemps après leur installation sur le sol européen. En conséquence la proportion des jeunes d’origine étrangère s’accroît rapidement dans la plupart des pays d’Europe. Christopher Caldwell remarque, avec une certaine ironie, que cette réalité démographique nouvelle transparaît involontairement dans l’euphémisme employé pour désigner une certaine délinquance. Lorsqu’un Parisien parle des déprédations commises par « une bande de jeunes », tout le monde comprend que les jeunes en question sont, la plupart du temps, d’origine africaine ou nord-africaine (p16). Comme le rappelle Christopher Caldwell, la décision de recourir à une immigration extra-européenne massive se fondait essentiellement, à ses débuts, sur des considérations économiques. Les pays européens, ravagés et décimés par la seconde guerre mondiale, avaient un important déficit de main d’œuvre qui paraissait justifier le recours à des travailleurs étrangers. Des programmes furent donc mis en place, un peu partout en Europe, pour les attirer. L’immigration semblait alors une bonne affaire pour les pays d’accueil. En réalité ce calcul apparemment rationnel reposait sur deux hypothèses qui furent insuffisamment examinées. La première était que les besoins couverts par la main d’œuvre étrangère étaient des besoins durables, la seconde était que ces immigrants rentreraient chez eux une fois que ces besoins auraient cessé. A la fin des années 1960, la plupart des emplois industriels occupés par la main d’œuvre immigrée avaient disparu ou étaient en voie de disparition mais la main d’œuvre, elle, était toujours là. Non seulement les « travailleurs invités » (gastarbeiter) ne rentraient pas chez eux, mais leur simple présence sur le sol européen suscitait un flot continu de nouvelles arrivées : « Le premier facteur de l’immigration, c’est l’immigration. Il faut du courage pour se lancer le premier et pour se soumettre aux lois, aux coutumes et aux caprices d’une société qui ne se soucie pas de vous. Mais une fois que vos compatriotes ont établi une tête de pont, l’immigration devient simple et routinière. » (p31). Autrement dit, et sans en avoir bien conscience, en recourant à l’immigration les décideurs européens avaient choisis de résoudre des problèmes économiques transitoires par un changement démographique permanent (p35).

Au moment où le chômage de masse commençait à frapper l’Europe et où il devenait évident que les maigres gains économiques que l’on pouvait attendre de l’immigration n’étaient plus d’actualité, un nouvel argument apparu pour expliquer à des populations de plus en plus inquiètes pourquoi les flux migratoires ne diminuaient pas. Les pays européens, du fait de leur natalité déclinante, avaient besoin d’un apport massif de jeunes étrangers pour sauvegarder leur Etat-providence. L’idée que les indigents du tiers-monde puissent se porter au secours des avantages acquis et des confortables retraites des travailleurs européens est pourtant encore plus improbable, en termes économiques, que l’idée de recourir à eux pour faire tourner des industries déclinantes. Personne, apparemment, n’avait envisagé que les migrants puissent vieillir et faire un jour valoir leurs droits à la retraite, ni que leur nombreuse famille pourrait peser sur le système social qu’ils étaient censés sauver.

En réalité, pour que les immigrés puissent aider l’Etat-providence, il faudrait qu’eux-mêmes et leurs descendants cotisent plus qu’ils ne reçoivent, mais ce n’est jamais le cas : ils travaillent et gagnent trop peu pour cela (p49). Parmi les nombreuses statistiques que cite Christopher Caldwell sur ce sujet, deux peuvent suffire pour mesurer le problème. En 2005 aux Pays-Bas, 40% des immigrés recevaient une forme ou une autre d’aide sociale. Entre 1971 et 2000, le nombre d’étrangers résidants en Allemagne est passé de 3 à 7,5 millions, mais le nombre de travailleurs étrangers est lui resté constant. Il va sans dire que la situation de l’Allemagne et des Pays-Bas n’a rien d’atypique. Les mêmes phénomènes peuvent être observés dans tous les pays européens.

Les chiffres qu’utilise Christopher Caldwell pour montrer le caractère largement illusoire des gains attendus de l’immigration ne sont pas secrets, la plupart sont même produits par des organismes officiels. Le mécontentement croissant des autochtones face à l’arrivée continue de nouveaux migrants n’est pas un secret non plus. Comment expliquer alors que des gouvernements démocratiquement élus n’aient pas fermé brutalement les portes, au moment où il devenait évident pour tout le monde que l’eau commençait sérieusement à monter ?

Les portes ne se sont pas fermées, car ceux qui les commandaient n’ont pas eu le courage de les actionner. Un pays ne peut guère refuser l’entrée sur son territoire aux migrants qui se pressent à ses frontières que pour deux raisons : pour préserver sa prospérité, ou pour préserver ses lois, ses coutumes, sa religion, ce que l’on appelle ordinairement sa culture. Mais le premier motif paraîtra égoïste, voir injuste si l’on s’est persuadé « qu’ils sont pauvres parce que nous sommes riches ». Le second motif paraîtra xénophobe, voire raciste. Dans une Europe rongée par la culpabilité après les crimes du nazisme et désireuse de désavouer son passé coloniale, de telles accusations étaient insupportables (p55, 268). Plus exactement, ces accusations se révélèrent impossibles à supporter pour les élites européennes. Plutôt que de devoir y faire face, ces élites politiques, économiques et intellectuelles préfèrent donc fermer les yeux sur une immigration dont elles n’avaient guère à supporter personnellement les conséquences, et elles ne purent résister à la tentation de battre leur coulpe sur la poitrine de leurs concitoyens.

Christopher Caldwell insiste sur le fait que les populations européennes n’auraient, dans leur très grande majorité, jamais accepté une telle immigration si elles avaient été consultées sur le sujet (p4, 14, 65, 101, 111, 328). Qu’elles ne l’aient pas été n’est pas un oubli : jusqu’à aujourd’hui presque toutes les décisions prises en matière d’immigration reposent implicitement sur l’idée qu’il n’est pas possible de faire confiance à un électorat démocratique pour se conduire de manière civilisée dans ce domaine (p80, 330). La politique d’immigration fait partie de ces questions sur lesquelles les élites européennes s’accordent, pour reconnaître qu’il ne serait pas raisonnable de demander leur avis aux premiers concernés.

Christopher Caldwell ne manque pas de noter les similarités, et les interactions, entre cette approche des questions migratoires et la construction européenne (p83). Bien qu’elle ait pendant longtemps été officiellement justifiée par des considérations économiques, la construction européen est essentiellement, depuis ses débuts, un projet moral, visant à rédimer les pays européens de leurs pêchés nationalistes et elle procède, depuis toujours, soigneusement à l’abri des réactions électorales des populations concernées. Au fond de l’intégration européenne, comme au fond des politiques migratoires suivies depuis un demi siècle, se lisent le même désir d’expier les crimes de l’Europe, réels ou supposés, et la même défiance vis-à-vis des citoyens ordinaires, soupçonnés, sans doute à juste titre, d’être spontanément attachés à leurs mœurs, à leurs coutumes, à leurs pays.

Non seulement l’intégration européenne rend la défense de vos frontières de plus en plus difficile à justifier – pourquoi défendre ce que vous cherchez par ailleurs à dépasser ? – mais elle tend à priver effectivement les gouvernements nationaux des moyens nécessaires pour le faire. Au sein de l’espace Schengen, n’importe quel Etat-membre est à la merci de l’Etat le plus faible ou le plus corrompu pour régler ses flux migratoires. Par ailleurs cette intégration habitue insensiblement les citoyens des Etats-membres à dépendre, dans leur vie quotidienne, des décisions d’une administration lointaine, opaque et, à strictement parler, irresponsable. Elle les rend peu à peu indifférents au fait de se gouverner eux-mêmes. Bien que la construction européenne ait été pensée tout à fait indépendamment de la question migratoire, cette construction contribue sans doute beaucoup à expliquer la relative passivité avec laquelle les populations européennes ont accepté des politiques migratoires qu’elles désapprouvaient.

Malheureusement pour les pays européens, ce qui avait provoqué l’ouverture de leurs frontières aux migrants extra-européens était aussi ce qui allait rendre leur assimilation de plus en plus difficile.

Outre l’invocation du pieux mensonge selon lequel leurs pays seraient « depuis toujours » des pays d’immigration, un grand nombre d’Européens tentent de se rassurer face à la transformation démographique en marche en invoquant l’exemple des Etats-Unis. Ne sont-ils pas la preuve du fait qu’un pays peut accueillir un très grand nombre d’immigrants et cependant rester essentiellement lui-même ? Mais, comme l’explique Christopher Caldwell, les Etats-Unis ne peuvent guère servir de modèle pour l’Europe. Outre les différences historiques et géographiques considérables entre la situation américaine et la situation européenne, deux éléments principaux expliquent le relatif succès des Etats-Unis, jusqu’à présent, dans l’assimilation de leurs immigrants : un patriotisme vivace et un Etat-providence de taille encore modeste.

Aux Etats-Unis, la plupart des nouveaux venus adoptent rapidement la langue, les mœurs et jusqu’au patriotisme sourcilleux de leur pays d’accueil essentiellement car ils n’ont pas le choix (p338-340). Ne pas s’assimiler signifie l’isolement, l’ostracisme, le confinement aux marges de l’économie. Il n’est nullement besoin de faire signer aux immigrants des « contrats d’intégration », car ceux-ci découvriront très vite que, si les Etats-Unis sont bien une terre d’opportunité, ils sont aussi un pays où la plupart des habitants attendent des nouveaux venus une loyauté sans faille vis-à-vis de leur pays d’accueil et où le système économique rejette impitoyablement ceux qui ne s’adaptent pas à ses exigences.

Cette situation, où la pression pour s’assimiler est d’autant plus forte qu’elle est informelle, était celle qui prévalait dans les pays européens avant la seconde guerre mondiale (p151). Mais aujourd’hui la plupart des immigrants savent, avant même d’arriver sur le sol européen, que le gouvernement viendra à leur secours s’ils déclarent n’avoir pas de ressources et ils savent aussi, ou ils découvrent rapidement, qu’en Europe le patriotisme est passé de mode. Pourquoi donc les nouveaux arrivants devraient-ils se donner de la peine pour s’intégrer sur le marché du travail, alors que l’Etat-providence rend cette intégration à la fois plus difficile et moins nécessaire ? Pourquoi donc devraient-ils s’attacher à leur pays d’accueil, alors que les autochtones paraissent avoir honte de la plus innocente manifestation de patriotisme ? Dans de telles conditions, le fait étonnant n’est pas que l’assimilation n’ait pas lieu mais plutôt le fait qu’elle continue parfois à avoir lieu.

La conjonction malheureuse de l’immigration de masse, de l’extension de l’Etat-providence et de la construction européenne aurait, par elle-même, été porteuse de bouleversements considérables pour les pays européens concernés. Mais, selon Christopher Caldwell, c’est un quatrième facteur qui menace d’élever ces bouleversements au rang d’une véritable révolution. Ce facteur est l’islam.

L’expansion de l’islam en Europe est devenue ce sujet auquel tout le monde pense, mais dont il est bien entendu qu’il ne faut surtout pas parler entre gens de bonne compagnie. La raison officielle de ce silence est que l’islam n’est pas du tout un problème, mais la raison véritable est bien plutôt que nul ne sait comment résoudre ce problème. Etant Américain, Christopher Caldwell n’a pas ces pudeurs et il n’a pas non plus à craindre l’ostracisme qui, en Europe, frapperait celui qui cesserait d’être de bonne compagnie.

L’Europe, depuis une cinquantaine d’années, est devenue terre d’accueil pour une immigration de masse. Ces migrants sont d’origines diverses, mais une grande partie d’entre eux partagent une caractéristique très importante : ils sont musulmans. A ce caractère majoritairement musulman de l’immigration extra-européenne s’ajoutent les taux de fécondité en général élevés de ces migrants. Comme le remarque Christopher Caldwell, la religiosité est le meilleur indicateur de la fécondité et, même longtemps après leur arrivée, les populations musulmanes conservent un taux de fécondité supérieur à celui des autochtones (p118). La conséquence est la croissance continue de la population musulmane en Europe. Ainsi, en Autriche, un pays presque uniformément catholique à la fin du siècle dernier, l’Islam sera probablement devenue la religion majoritaire parmi les moins de quinze ans en 2050. A Bruxelles, en 2006, 57% des nouveaux-nés étaient nés dans des familles musulmanes. Par conséquent il est probable que, d’ici vingt ans, la capitale de l’Union Européenne sera devenue une ville à majorité musulmane. A un journaliste allemand qui lui demandait, en 2004, si l’Europe serait une grande puissance à la fin du siècle, le grand orientaliste Bernard Lewis avait répondu sans ciller que, à cette date, l’Europe serait devenue une partie du Maghreb (p14).

Cette transformation religieuse de l’Europe aurait pu passer relativement inaperçue parmi des populations européennes de plus en plus indifférentes à leur propre religion, si les européens de souche n’avaient pas remarqué, avec un malaise grandissant, que ces populations musulmanes paraissaient avoir beaucoup plus de mal à s’assimiler que toutes les autres. Bien pire, certains indicateurs semblaient même montrer que les dernières générations allaient plutôt dans le sens de la désassimilation (p133). Un moyen relativement sûr de juger de l’assimilation d’une population immigrée est d’observer ses pratiques matrimoniales.

Une population en voie d’assimilation est une population dont les enfants se marient, pour l’essentiel, avec des autochtones. Mais, partout en Europe, les populations musulmanes montrent une nette préférence pour les mariages à l’intérieur de leur communauté religieuse et ethnique. Cette préférence parait même plus marquées pour les plus jeunes générations. En Allemagne, en 2004, plus de la moitié des citoyens allemands d’origine turque allaient chercher leurs conjoints en Turquie. En Grande-Bretagne, on estime couramment que 60% des mariages à l’intérieur des communautés pakistanaises et bangladeshi se font avec des conjoints venus de l’étranger. Comme le note Christopher Caldwell, les statistiques de ce genre émeuvent légitimement les pays concernés, car elles sont le signe clair d’un refus collectif de l’assimilation (p225). Plus immédiatement inquiétant, les taux de réussite scolaire des jeunes hommes issus de l’immigration musulmane se révèlent, là où les statistiques existent, parmi les plus bas et leurs taux de délinquance parmi les plus hauts. En France l’absence de statistiques officielles permet de jeter un voile pudique sur cette réalité, mais tous les professionnels de la justice savent parfaitement que l’islam est vraisemblablement aujourd’hui la première religion des prisons françaises (p136). Que, lors des émeutes qui se sont déroulées en octobre 2005 autour de Paris, l’écrasante majorité des émeutiers aient été des jeunes gens d’origine africaine ou nord-africaine n’a pas échappé au grand public, pas plus que le fait qu’un bon nombre d’entre eux paraissaient attacher une grande importance à leurs racines musulmanes (p141-142).

La seule interprétation publiquement acceptable de ces particularités est que les populations musulmanes ne s’assimilent pas à cause du racisme et des discriminations dont elles seraient victimes dans leur pays d’accueil. Christopher Caldwell n’est manifestement pas convaincu par ce genre d’explications. Il n’est pas vraisemblable que les sociétés européennes soient plus racistes aujourd’hui ou plus portées à la xénophobie qu’au début du siècle dernier. Le contraire est même presque certain. Pourtant les immigrants arrivés au siècle dernier se sont fondus bien plus rapidement dans leur pays d’accueil que les migrants actuels. Personne, en France, n’a jamais parlé des Italiens ou des Polonais de la seconde génération, car cette seconde génération ne se distinguait plus du reste de la population que par son patronyme. Ces immigrés Italiens, Polonais, Russes, Portugais n’avaient aucun organisme gouvernemental pour les aider à leur arrivée, pas de travailleurs sociaux pour les informer sur leurs « droits », pas ou peu de prestations sociales, pas d’habitations à loyer modéré pour se loger, et cependant l’assimilation se faisait rapidement. Mais aujourd’hui, en dépit de tous ces nouveaux avantages, en dépit de milliards d’euros dépensés en « politiques de la ville », en dépit d’une traque aux « discriminations » de plus en plus obsessionnelle de la part des pouvoirs publics, parmi les populations musulmanes chaque génération est toujours, dans une large mesure, une première génération (p228).

Les gouvernants européens, aidés en cela par une certaine sociologie, tentent de dissimuler ce fait massif en substituant à la notion d’assimilation celle d’intégration et en définissant l’intégration comme certains comportements extérieurs. Les nouveaux venus sont censés être « intégrés » à leur société d’accueil s’ils adoptent certaines de ses particularités insignifiantes, ou s’ils acquièrent des diplômes, ou s’ils obéissent aux lois. Mais bien sûr la question qui taraude l’Européen ordinaire n’est pas de savoir si les immigrants obéissent aux lois, puisque cela est de toutes façons obligatoire, ni s’ils acquièrent des diplômes, puisque cela est leur intérêt évident, ni s’ils connaissent la différence entre une Schinkenwurst et une Bratwurst, mais s’ils sont loyaux envers le pays qui est censé être le leur (p154-158). Si leur attachement envers leur patrie d’accueil est, comme pour les autochtones, supérieur à tous les autres éléments de leur « identité ». C’est ce que l’Européen ordinaire entend par « assimilation », mais c’est ce dont les gouvernants européens ne veulent plus entendre parler, en partie sans doute car ils devinent trop bien la réponse.

Bien qu’il ne le dise pas tout à fait aussi explicitement, Christopher Caldwell estime à l’évidence que le facteur essentiel qui s’oppose à l’assimilation des populations musulmanes est leur religion. Christopher Caldwell semble penser que l’islam, au moins tel qu’il existe actuellement, n’est pas compatible avec des institutions et, surtout, avec des mœurs démocratiques. Il rappelle ainsi que l’islam n’est pas seulement une foi mais aussi une loi religieuse hautement détaillée (la Sharia) qui règle tous les aspects de la vie des croyants. Il rappelle aussi que « les cultures musulmanes ont produit régulièrement des régimes autoritaires - si régulièrement en fait que, lorsque des savants bien intentionnés veulent apporter des preuves que l’islam est ouvert aux réinterprétations et au débat rationnel, ils se tournent en général vers les innovations éphémères des Mu’tazilites au neuvième siècle. » (p278).

En suggérant que l’islam est incompatible avec des principes démocratiques aussi fondamentaux que la liberté de conscience ou la liberté de parole, Christopher Caldwell reprend simplement à son compte une interprétation vénérable et qui, jusqu’à une date récente, était très majoritaire parmi les penseurs européens, l’interprétation selon laquelle l’islam est fondamentalement la religion du despotisme. De nos jours cette interprétation est bien évidemment frappée d’anathème parmi les élites européennes, mais elle transparaît néanmoins involontairement dans l’assurance donnée par ces mêmes élites que l’islam serait sur la voie de la « modernisation ». La « modernisation » en question est celle qui devrait amener l’islam au point où en est parvenu le christianisme : une religion qui accepte la séparation des autorités temporelles et spirituelles et qui respecte toutes les grandes libertés démocratiques.

Les deux prémisses essentielles du dogme de la « modernisation » sont que toutes les religions sont fondamentalement identiques et que ce qui est arrivé au christianisme arrivera nécessairement à l’islam. Ces deux prémisses sont fausses. Certaines religions sont, de par leurs caractéristiques intrinsèques, plus « modernisables » que d’autres et cette « modernisation » dépend aussi de conditions extérieures qui ne sont pas toujours réunies. Comme le rappelle à juste titre Christopher Caldwell, la « modernisation » du christianisme fut en partie le produit de luttes intenses, et parfois violentes, entre les autorités religieuses et leurs adversaires (p201). Mais aujourd’hui l’obsession européenne de la « tolérance » et de « l’anti-racisme » protège efficacement l’islam contre le genre de pressions auquel le christianisme fut soumis pendant des siècles. Les libres-penseurs européens, qui se réclament de Voltaire lorsqu’il s’agit de ridiculiser le christianisme, seraient parmi les premiers à exiger sa condamnation pour « islamophobie » si celui-ci venait à publier son Mahomet aujourd’hui. Ce n’est pas qu’au fond de leur cœur ils jugent l’islam plus aimable que le christianisme, mais ils espèrent, sans oser le dire, que l’islam aura l’amabilité de bien vouloir s’écrouler tout seul, de l’intérieur.

La situation serait déjà suffisamment sérieuse si les populations musulmanes d’Europe se contentaient de former des enclaves de plus en plus séparées du reste de la population. Mais une partie de ces populations, et notamment leur fraction la plus jeune, montre des signes aussi clairs qu’inquiétants d’hostilité franche envers le pays qui est censé être le leur. Leur attachement, leur loyauté, ne vont pas au pays européen dans lequel ils résident, et dont beaucoup d’entre eux sont désormais citoyens, mais à l’Oumma, la communauté mondiale des musulmans.

Christopher Caldwell s’attarde longuement sur l’affaire des caricatures de Mahomet publiées en septembre 2005 par le quotidien danois Jyllands-Posten, car cette affaire lui semble particulièrement révélatrice. Outre le fait que les protestations extrêmement violentes qui secouèrent le monde musulman après la publication de ces caricatures avaient été orchestrées par deux imans danois, « l’aspect le plus alarmant de cette affaire était que les musulmans d’Europe tendaient à prendre parti pour les manifestants à l’étranger plutôt que pour leurs concitoyens » (p207). Cet aspect de la question ne passa pas inaperçu des gouvernants et des milieux d’affaire européens qui, dans leur immense majorité, rivalisèrent d’obséquiosité pour bien montrer à la « communauté musulmane » de leur pays à quel point ils désapprouvaient « l’offense » qui lui était faite. Derrière les déclarations solennelles sur le « respect » dû à toutes les religions et sur « l’insensibilité » des éditeurs du Jyllands-Posten, il n’était guère difficile, en effet, de percevoir qu’un tout autre sentiment était à l’oeuvre : la peur. Christopher Caldwell remarque ainsi qu’il existe désormais en Europe, de facto, une loi contre le blasphème, à l’usage exclusif des musulmans (p203). Cette loi repose sur la détermination de certains fanatiques religieux à assassiner ceux qui parleraient de l’islam d’une manière qui leur déplait. Ces fanatiques ne se trouvent pas seulement dans les pays musulmans, mais aussi un peu partout sur le sol européen. De Salman Rushdie à Robert Redeker en passant par Ayaan Hirsi Ali, nombreux sont désormais ceux qui ont dû basculer dans la clandestinité ou quitter le territoire européen pour avoir blessé certaines sensibilités musulmanes ; trop heureux de ne pas avoir été assassinés, comme Théo Van Gogh ou l’éditeur Norvégien des Versets sataniques. Sans doute seraient-ils plus nombreux encore, si les menaces adressées à certains n’avaient pas eu pour effet d’amener la plus grande partie des élites politiques et intellectuelles à renoncer, par avance, à tout ce qui pourrait de près où de loin ressembler à une critique de l’islam (p204).

Le caractère manifestement très fragile de la loyauté d’une partie de la population musulmane à l’égard du pays dans lequel elle vit est évidemment particulièrement inquiétant dans le contexte actuel de la lutte contre le terrorisme islamiste. Nul n’ignore que les auteurs des attentats de Londres, le 7 juillet 2005, étaient de jeunes musulmans britanniques. Cette lutte contre le terrorisme est officiellement présentée, en Occident, comme une lutte contre une frange infime de mauvais musulmans qui pervertiraient l’islam. Nombre d’hommes politiques occidentaux se sont ainsi transformés du jour au lendemain en expert en théologie islamique, et affirment gravement que l’islam est une religion pacifique et tolérante qui est défigurée par ceux qui tuent en son nom. Peut-être est-il de bonne politique de dire de telles choses en public, mais Christopher Caldwell ne parait pas tout à fait convaincu que ce genre d’affirmation soit plus qu’un pieux mensonge.

Bien qu’il ne se prononce pas définitivement sur la question, Christopher Caldwell semble plutôt être de l’avis du sociologue anglais David Martin, selon lequel l’islam recherche certes la paix, mais à ses propres conditions (p277, 298). Les gouvernants européens cherchent eux désespérément à obtenir le soutien des « musulmans modérés » face aux islamistes, afin de valider leur thèse sur le caractère essentiellement pacifique de l’islam. Mais les interlocuteurs les plus « modérés » qu’ils parviennent à trouver condamnent du bout des lèvres les méthodes d’Al-Quaida, tout en insistant sur le fait que l’Occident doit surtout veiller à ne pas « offenser » les musulmans de par le monde. Christopher Caldwell remarque, avec un peu d’ironie : « Al-Quaida dit que l’Occident doit faire certaines choses ou subir des attaques terroriste. Les modérés disent que l’Occident doit faire certaines choses ou les modérés rejoindront les rangs d’Al-Quaida. S’il s’agit là du choix de l’Occident, il est difficile de voir ce qu’il pourrait gagner en courtisant les musulmans modérés. » (p287).

***

L’avenir est par définition inconnu et Christopher Caldwell reste légitimement prudent lorsqu’il s’agit d’envisager les développements de la révolution qu’il décrit. Mais il est assez clair qu’il ne pense pas que le futur de l’Europe sera radieux. Il insiste notamment sur le fait que l’immigration massive à laquelle l’Europe fait face aura un coût élevé en termes de libertés (p13, 93, 209, 214, 229, 237), ce qui en réalité est moins une prévision qu’une constatation. La peur, le politiquement correct et les lois « anti-discriminations » ont déjà réduit à bien peu de choses la liberté de paroles quand il s’agit de traiter le sujet de l’immigration en général et de l’islam en particulier. Par ailleurs, lorsqu’un gouvernement européen tente timidement de s’opposer à des pratiques importées contraires aux coutumes et aux mœurs du pays, il ne parvient en général à le faire qu’en restreignant les droits de tous ses citoyens. Ainsi, pour stopper la progression du foulard islamique dans ses écoles publiques, la France a pris une loi bannissant tous les signes religieux ostensibles des lieux publics. Pour s’opposer aux mariages arrangés pratiqués par une partie de leur population musulmane, plusieurs pays européens, comme les Pays-Bas ou le Danemark, ont imposé des restrictions à tous leurs citoyens qui désireraient épouser un étranger ou une étrangère. Pour s’opposer aux mutilations génitales pratiquées par certains immigrants musulmans originaires d’Afrique, un ministre suédois a proposé que soit instauré un examen gynécologique obligatoire pour toutes les petites suédoises.

Le problème essentiel, selon Christopher Caldwell, est que, dans sa confrontation avec l’islam, l’Europe apparaît bien comme la partie spirituellement la plus faible. Elle a perdu de vue depuis longtemps, non seulement ce qui faisait la spécificité de la civilisation occidentale mais aussi les raisons pour lesquelles celle-ci mériterait d’être défendue (p82, 347). Son relativisme l’empêche de mener plus que des combats d’arrière-garde contre ceux qui voudraient changer ses mœurs et ses lois. Un demi-siècle d’Etat-providence et de construction européenne ont considérablement affaibli l’attachement de ses habitants à leurs libertés essentielles et à leurs patries. Sa déchristianisation accélérée la laisse sans grande ressource face à une religion conquérante, incapable même de comprendre la séduction qu’une vie organisée autour de la religion peut exercer (p181). Au vu de tous ces éléments, il est aisé de comprendre pourquoi le livre de Christopher Caldwell ne dit pas un mot sur la manière dont l’Europe pourrait sortir de l’impasse où elle s’est engagée. Il conclut en ces termes :

« Il est certain que l’Europe émergera changée de sa confrontation avec l’islam. Il est beaucoup moins certain que l’islam se révèlera assimilable. L’Europe se trouve engagée dans une compétition avec l’islam pour gagner l’allégeance de ses nouveaux arrivants. Pour le moment l’islam est la partie la plus forte, dans un sens démographique bien sûr, mais aussi dans un sens philosophique moins évident. Dans de telles circonstances, les mots « majorité » et « minorité » ont peu de signification. Lorsqu’une culture doutant d’elle-même, malléable, relativiste, rencontre une culture bien ancrée, confiante et fortifiée par des doctrines communes, c’est en général la première qui change pour s’adapter à la seconde. »

Par Amaury Watremez. A propos de la sortie en Folio d’une partie de la correspondance de Céline, les Lettres à la NRF, passionnantes.

Par Amaury Watremez. A propos de la sortie en Folio d’une partie de la correspondance de Céline, les Lettres à la NRF, passionnantes.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Suicide has stirred some controversy in the mainstream media for stating what for many is, or should be, known and obvious, but which for the majority is either not so or taboo: the negative consequences of immigration, diversity, and multiculturalism.

Suicide has stirred some controversy in the mainstream media for stating what for many is, or should be, known and obvious, but which for the majority is either not so or taboo: the negative consequences of immigration, diversity, and multiculturalism. Buchanan is correct to identify the decline of Christianity in America as one of the roots of its decline. In doing so, however, he has Edward Gibbon as his inverse counterpart, for Gibbon identified the rise of Christianity in Rome, that is, the decline of the Roman religion, as one of the causes of Rome’s fall. Gibbon would have sympathised, perhaps, with the statement, ‘When the faith dies, the culture dies, the civilization dies, the people die.’ Yet, given that the fall of Rome did not mean the end of European man, and that if the rise of Christianity was linked to Rome’s fall, the rise of Christianity was also linked to the rise of Faustian civilisation. All this tells us, therefore, is that we may be witnessing the end of a cycle involving Christianity. However, even if it is Christianity’s fate to pass, as have other religions, or to become a ‘Third World religion’, as Buchanan puts it, European man will still be there, at least for a while, and, provided he survives as a race, he will give rise to a new civilisation, traceable to the Greek, the Roman, and the Faustian, but founded on somewhat different principles. This will bring no comfort to Christians, nevertheless, and Buchanan, as a Christian, is justified in his alarm.

Buchanan is correct to identify the decline of Christianity in America as one of the roots of its decline. In doing so, however, he has Edward Gibbon as his inverse counterpart, for Gibbon identified the rise of Christianity in Rome, that is, the decline of the Roman religion, as one of the causes of Rome’s fall. Gibbon would have sympathised, perhaps, with the statement, ‘When the faith dies, the culture dies, the civilization dies, the people die.’ Yet, given that the fall of Rome did not mean the end of European man, and that if the rise of Christianity was linked to Rome’s fall, the rise of Christianity was also linked to the rise of Faustian civilisation. All this tells us, therefore, is that we may be witnessing the end of a cycle involving Christianity. However, even if it is Christianity’s fate to pass, as have other religions, or to become a ‘Third World religion’, as Buchanan puts it, European man will still be there, at least for a while, and, provided he survives as a race, he will give rise to a new civilisation, traceable to the Greek, the Roman, and the Faustian, but founded on somewhat different principles. This will bring no comfort to Christians, nevertheless, and Buchanan, as a Christian, is justified in his alarm.

Wenn Siegfried bei seiner Ankunft in Worms Gunther grundlos zum Duell fordert, dann bezeichnet Fernau das als „peinlich“ – so benimmt sich kein Ritter, das machen höchstens Abenteurer oder Rumtreiber. Hagens „Nibelungentreue“ wird zur „schauerlich-imposanten Geradlinigkeit“. Bei Fernau ist nichts bis wenig von diesem ehrfürchtigen Schauer zu spüren, der – so glaubt man doch als Jugendlicher – bei einem Text dieser Größe und dieses Alters angemessen wäre.

Wenn Siegfried bei seiner Ankunft in Worms Gunther grundlos zum Duell fordert, dann bezeichnet Fernau das als „peinlich“ – so benimmt sich kein Ritter, das machen höchstens Abenteurer oder Rumtreiber. Hagens „Nibelungentreue“ wird zur „schauerlich-imposanten Geradlinigkeit“. Bei Fernau ist nichts bis wenig von diesem ehrfürchtigen Schauer zu spüren, der – so glaubt man doch als Jugendlicher – bei einem Text dieser Größe und dieses Alters angemessen wäre.

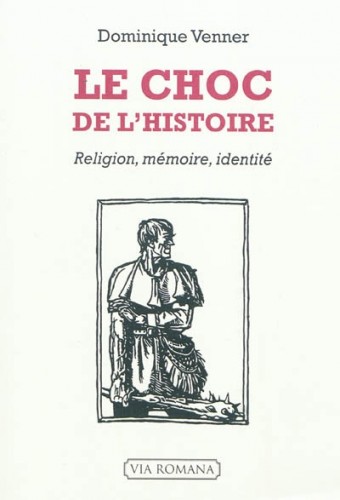

Dans un livre d’entretien conduit par la journaliste Pauline Lecomte, « Le choc de l’histoire » publié aux éditions « Via Romana », Venner se penche une nouvelle fois sur notre époque en crise. On retrouvera en filigrane la grille d’analyse affûtée qu’il avait déjà exposée dans son ouvrage « Le siècle de 1914 », mais cette fois pour en dépasser le cadre restreint de la discipline historique.

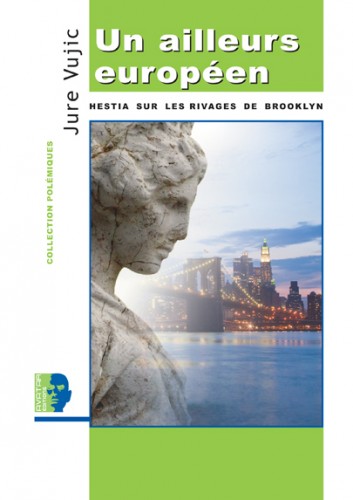

Dans un livre d’entretien conduit par la journaliste Pauline Lecomte, « Le choc de l’histoire » publié aux éditions « Via Romana », Venner se penche une nouvelle fois sur notre époque en crise. On retrouvera en filigrane la grille d’analyse affûtée qu’il avait déjà exposée dans son ouvrage « Le siècle de 1914 », mais cette fois pour en dépasser le cadre restreint de la discipline historique.  „La tradition est inversée. L’Europe ne raconte plus l’Occident. C’est l’Occident qui comte l’Europe. La marche en avant des proto-iraniens, peuples de cavaliers vers leur foyer « européen », la « hache barbare » du peuple des demi-dieux hyperboréens, Alexandre, Charlemagne, Hoffenstaufen, Charles Quint, Napoléon ne font plus rêver. L’Occident hyperréel sublimé, le mirage du « standing », du bonheur à la carte est le songe éveillé et névrotique du quart-monde favellisé, d’un imaginaire tiers-mondiste « bolly-woodisé ». Il n’y a plus de grand métarécit européen faute de diégèse authentiquemment européenne. La « mimesis vidéosphérique » occidentale dévoile, déshabille, montre et remontre dans l’excès de transparence. Loin des rivages de l’Hellade, Hestia s’est trouvé un nouveau foyer sur les bords de Brooklyn, aussi banal et anonyme que les milliers d’« excréments existentiels » qui jonchent les rivages de Long Island.“

„La tradition est inversée. L’Europe ne raconte plus l’Occident. C’est l’Occident qui comte l’Europe. La marche en avant des proto-iraniens, peuples de cavaliers vers leur foyer « européen », la « hache barbare » du peuple des demi-dieux hyperboréens, Alexandre, Charlemagne, Hoffenstaufen, Charles Quint, Napoléon ne font plus rêver. L’Occident hyperréel sublimé, le mirage du « standing », du bonheur à la carte est le songe éveillé et névrotique du quart-monde favellisé, d’un imaginaire tiers-mondiste « bolly-woodisé ». Il n’y a plus de grand métarécit européen faute de diégèse authentiquemment européenne. La « mimesis vidéosphérique » occidentale dévoile, déshabille, montre et remontre dans l’excès de transparence. Loin des rivages de l’Hellade, Hestia s’est trouvé un nouveau foyer sur les bords de Brooklyn, aussi banal et anonyme que les milliers d’« excréments existentiels » qui jonchent les rivages de Long Island.“ En abordant la question du devenir de l’Europe, l’auteur rend compte des mutations du „monde européen“ contemporain dans le sens symbolique, essentialiste et métaphysique, asphyxié sous l’empire d'un „occidentalo-centrisme“ mécaniciste qui l'a indéniablement absorbé et consumé, est qui du reste constitue son degré zéro de la puissance symbolique.

En abordant la question du devenir de l’Europe, l’auteur rend compte des mutations du „monde européen“ contemporain dans le sens symbolique, essentialiste et métaphysique, asphyxié sous l’empire d'un „occidentalo-centrisme“ mécaniciste qui l'a indéniablement absorbé et consumé, est qui du reste constitue son degré zéro de la puissance symbolique.