Alex KURTAGIC

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Adam Fergusson

When Money Dies: The Nightmare of Deficit Spending, Devaluation, and Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany

Old Street Publishing, 2010

Warren Buffett recommendations notwithstanding, it says something about the state of our economy when someone decides it is time to resurrect a 35-year-old account of the Weimar-era hyperinflation.

Written during the stagflationary 1970s, Adam Fergusson’s When Money Dies: The Nightmare of the Weimar Hyperinflation contains much to titillate our morbid curiosity, besides an instructive illustration of what we can expect should the Austrian economists’ gloomiest prophecies ever come true. (The book, long out of print, was fetching close to $700 on eBay this summer, and has now been made available in electronic format.)

Defined in the present text as occurring when the rate of inflation exceeds 50 percent per month, hyperinflation is caused by an uncontrolled increase in the money supply and a loss of confidence in the currency. Because of the absence of a tendency towards equilibrium, fear of the rapid and continuous loss of value makes people unwilling to hold on to the money for any longer than is necessary to convert it into tangible goods or services. Hyperinflation is therefore characterized by very rapid depreciation and a dramatic increase in the velocity of the circulation of money.

Although the most famous (because it was the first to have been systematically observed and because it was deemed to have made Hitler possible), the hyperinflation of Weimar-era Germany, where Papiermark-denominated prices came to double every 3.7 days, takes “only” fourth place in the hyperinflationary hall of fame. The first place belongs to post-World War II Hungary, where in July 1946 pengő-denominated prices doubled every 15 hours. The second place belongs to Mugabe-era Zimbabwe, where in November 2008 Zimbabwean dollar-denominated prices doubled every 24.7 hours. And the third place belongs to Balkans War-era Yugoslavia, where in January 1994 Yugoslav dinar-denominated prices doubled every 1.4 days.

In Germany the inflationary cycle had already begun during World War I, when the paper mark went from 20 to the pound (at the time worth around 4 dollars) to 43 to the pound by war’s end. Although the paper mark continued tumbling downward, spiking momentarily in the first quarter of 1920, it recovered somewhat afterwards and remained more or less stable until the first half of 1921. The London Ultimatum, however, which demanded war reparations to be paid in gold marks to the tune of 2,000,000,000 per annum, plus 26 per cent of the value of German exports, triggered a new leg of rapid depreciation. The French policy towards Germany, backed by the British, was virulently vengeful, and imposed an onerous burden on Germany’s economy: in fact, the amount demanded was in excess of Germany’s total holding of gold or foreign exchange. The deficit in the budget, of which reparations contributed a third, was made up by discounting government Treasury bills and printing money.

Despite a momentary respite during the first half of 1922, during which international reparations conferences caused the paper mark to stabilize at around 320 to the dollar, the lack of an agreement triggered a new crisis, resulting in a phase of hyperinflation. Fuelled by the German government’s policy of passive resistance to French occupation of the Ruhr, which from January 1923 meant subsidizing through money-printing an anti-occupation strike by German workers, said hyperinflation escalated exponentially until November that year, when the introduction of the Rentenmark finally stopped the economic rot. By that time the German currency had fallen to 4,200,000,000,000 paper marks to the dollar.

Fergusson attributed the extraordinary self-inflicted destruction of Germany’s monetary system to a failure on the part of its government and the Reichsbank to link currency depreciation to money printing. Depreciation was initially believed to have been the result of the Entente powers forcing up foreign exchange through market manipulations. The German public appeared equally ignorant, believing that prices were going up as opposed to the value of their currency going down. Anti-Semitic explanations, not refuted by visible examples of vulgar Jewish ostentation, financial acrobatics, and profiteering, were also popular. The consequent misery and economic chaos showed the weaknesses of the chartalist monetary standard.

Combining a clear exposition with contemporary private diary entries, When Money Dies offers a harrowing narrative. The Weimar inflation obliterated savings, devoured wages, and caused assets to be distributed in the most unfair ways imaginable. As the wealthy had the means to protect themselves and even take advantage of the situation, and as the working class was organized and able to secure wage increases through frequent strikes and union demands, the main victims were the middle class — professionals, civil servants, the rentier class, and those on fixed incomes, who were reduced to penury and destitution. Landlords were also affected as a result of government-imposed rent controls.

The industrialist class, on the other hand, was not unhappy with the inflation, as they benefited from it. Indeed, some industrialists and profiteers made fortunes at everyone’s expense. Individual industrialists were able to acquire assets (usually fixed assets and raw materials) for minuscule amounts by securing large bank loans that became virtually worthless within weeks because of the low interest rates. Said industrialists also welcomed the virtual destruction of fiscal burdens: high inflation also made tax assessments worthless by the time taxes were due.

One of the effects of inflation was to turn everyone into a speculator — in the stock market, in foreign exchange, in commodities, and in assets, which offered protection from depreciation as well as profit opportunities. Foreign visitors in Germany were also able to take advantage of a notable differential between the official rate of foreign exchange and prices in real terms within Germany, where in relation to solid currencies like the dollar and the pound goods and services were available at bargain prices.

For most of the inflationary period Germany enjoyed full employment, but the incentive to work hard and save was progressively eroded by the increasing fugacity of purchasing power. The main concern was somehow keeping ahead of the mark’s accelerating depreciation, so as to be able to still obtain the necessities of life. Payday had to come with increasing frequency, and finally daily in order to keep up with prices, which rose with increasing rapidity until they changed by the hour. Part of the rise was due to the need to factor in depreciation occurring between the time the money was paid to the merchant and the time the merchant was able to dispose of it. It became the norm to spend money as quickly as it was obtained and for shops to sell out in a single day. Coffees were ordered two at a time, to avoid having to pay more for any second cup. Barter, bribes, and corruption also became universal.

Despite the prodigious nominal amounts, people’s main problem during this period was a chronic scarcity of money. Dozens of paper mills and printing firms and thousands of printing machines working night and day could not keep up with prices, causing the total amount of money in circulation constantly to decrease in real terms. Obviously, the more furious the money printing, the more acute the rate of depreciation, but his was something apparently not understood by Rudolf Havenstein, the president of the Reichsbank (German central bank), whose main preoccupation was ensuring there was enough money available to meet economic needs. Depreciation accelerated to such a degree that it eventually made more sense directly to burn money in the stove than first use it to purchase wood.

The scarcity of money was reflected in the government’s budget, which dwindled to paltry amounts in real terms, further aided by the breakdown of the taxation system and the ridiculously low price of stamps and railway fares. By the end of the hyperinflationary cycle, the government’s income was a fraction of 1 percent of its outgoings.

Food became progressively scarce as a result of hoarding and the refusal by farmers to sell their produce against worthless paper. Farmers were, in fact, relatively well off until almost the end, as they were able to produce their own food. City-dwellers were forced to sell their possessions in exchange for comestibles, and those visiting friends or relatives witnessed the latter’s flats gradually emptying of furniture, paintings, and any movable asset of value. Once these were gone, looting and farm raids was the next step for some. For others it was starvation and death.

The highest denomination note, issued towards the end of 1923, was 100,000,000,000,000 marks (compare with Hungary’s 100,000,000,000,000,000,000 pengő note in 1946). By this time, Dr. Havenstein had the equivalent of 300 ten-tonne train wagons of unissued bank notes awaiting distribution for the day. The mark, however, had become not only worthless but largely shunned in favour of foreign currencies and tangible assets. Also in circulation were not only the official Papiermark issued by the central bank but also emergency money issued by municipalities, local banks, and even private firms in the effort to make up for money shortages. Such an environment had made it impossible to ascertain with precision the value of anything, as sellers used their own indexes and asked whatever they thought they could get people to pay for their goods or services. The chaos and economic breakdown was so complete that Germany by late 1923 was on the verge dismemberment, with the republic having long been under siege from both Communists and the Far Right. Hitler, who attempted his Beer Hall Putsch in November that year, was among the agitators.

The death of Dr. Havenstein and the appointment of Dr. Hjalmar Schacht, marked the end of Weimar hyperinflation. This occurred under the auspices of a military dictatorship, comprised of Hans von Streisser, Otto von Lossow, and Gustav von Kahr, appointed by Prime Minister Eugen von Knilling, who, following a period of political violence an assassinations had declared martial law in September 1923. The discounting of Treasury bills was stopped and the Rentenmark — a temporary currency — was introduced at the rate of 1,000,000,000,000 Papiermark to 1 Rentenmark; also, debts were largely rescinded, unfairly to the detriment of many. Somehow, the confidence trick worked and a semblance of normality returned. Unfortunately, however, the price of stopping hyperinflation was steep and known in advance: mass unemployment, a sharp economic slowdown, and bankruptcies. The hyperinflation was allowed to carry on as long as it did partly because of an absence of political will to swallow the necessary bitter medicine.

Among the casualties were some of the industrialists and profiteers who were caught out in the hyperinflationary game of musical chairs once the currency reform was enacted. Those who survived and had benefited from the economic conditions were forced to adjust to the dull world of hard work, thrift, small profits, and taxes. Some, like the Jewish-Lithuanian Barmat brothers, still managed to exploit the situation to their advantage: they converted their assets into the new, strong mark and issued loans at extortionate rates of interest (of up to 100 percent) while credit was nearly impossible to find elsewhere. Hyperinflation had bred universal corruption, however — a world of dog-eat-dog rapacity, opportunism, and pauperized billionaires, where the worst human instincts flourished and became a matter of survival.

The post-hyperinflationary credit crunch was, not surprisingly followed by a credit boom: starved of money and basic necessities for so long (do not forget the hyperinflation had come directly after defeat in The Great War), many funded lavish lifestyles through borrowing during the second half of the 1920s. We know how that ended, of course: in The Great Depression, which eventually saw the end of the Weimar Republic and the beginning of the National Socialist era.

From the vantage-point of 2010, we see glimpses in Fergusson’s account of the way events might play out in the United States and possibly Western Europe in the coming years, absent any political will to tackle the mountain of public and private debt, the enormous budget deficits, and the stupendous above-growth monetary expansion of the past decade. The crises are likely to be similar in kind, but follow a different order. The credit boom of the 2000s has been followed by the credit crunch of the late 2000s. Analysts of the Austrian school deem us to be in the initial stages of a Second Great Depression, and vaticinate much worse to come.

Personally, I sometimes get tired of the unrelenting pessimism coming from some Austrian-influenced quarters, and wonder whether there is not a morbid curiosity there — untempered by personal experience — to witness a catastrophic collapse; but, all the same, I am not going to take chances and risk losing the little I have because I was bored by the truculent fantasies of some cleverer-than-thou commentators. When Money Dies is well worth reading if you are searching for a real-life overview of the sequence of weird phenomena that emerge during a inflationary cycle. Those who can would be well advised to use it and related texts to design in advance coping strategies in the event of monetary failure.

PS: For a fictional preview of what a hyperinflationary blowout might look like in Europe and the United States in 2022, see my novel Mister (Iron Sky Publishing, 2009).

Source: http://www.wermodandwermod.com/newsitems/news130120111511.html

Écrit par un collectif d’auteurs dont certains avaient déjà participé à la rédaction du roman d’anticipation politique Eurocalypse et qui ont assimilé l’œuvre de Jean Baudrillard, Choc et Simulacre est un ouvrage dense qui interprète, d’une manière décapante, les grands événements en cours.

Écrit par un collectif d’auteurs dont certains avaient déjà participé à la rédaction du roman d’anticipation politique Eurocalypse et qui ont assimilé l’œuvre de Jean Baudrillard, Choc et Simulacre est un ouvrage dense qui interprète, d’une manière décapante, les grands événements en cours.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

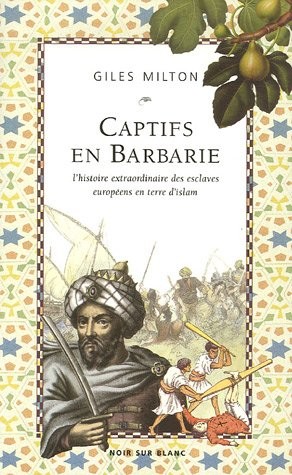

Dans son roman policier Le Phare, paru en 2008 à LGF/Livre de Poche et qu’elle situe à Combe Island, au large de la Cornouailles, l’Anglaise P. D. James signale à plusieurs reprises la terreur exercée par les pirates maghrébins, surtout ceux de Rabat-Salé, sur les côtes sud de l’Angleterre où ils s’étaient emparés de plusieurs îles, transformées en bastions. Le sort tragique et « l’histoire extraordinaire des esclaves européens en terre d’islam », c’est justement ce qu’a étudié l’historien Giles Milton, anglais lui aussi, dans Captifs en Barbarie.

Dans son roman policier Le Phare, paru en 2008 à LGF/Livre de Poche et qu’elle situe à Combe Island, au large de la Cornouailles, l’Anglaise P. D. James signale à plusieurs reprises la terreur exercée par les pirates maghrébins, surtout ceux de Rabat-Salé, sur les côtes sud de l’Angleterre où ils s’étaient emparés de plusieurs îles, transformées en bastions. Le sort tragique et « l’histoire extraordinaire des esclaves européens en terre d’islam », c’est justement ce qu’a étudié l’historien Giles Milton, anglais lui aussi, dans Captifs en Barbarie.

Sans doute le grand romancier trouva-t-il aussi dans le livre du philosophe, comme le remarque José Luis Goyenna dans son intéressante (quoique pleine de fautes) préface, en plus d'images étonnantes bien propres à enthousiasmer l'écrivain, une authentique philosophie de la liberté comme accomplissement métaphysique du moi qui, à la différence de celle de Sartre qualifiée par l'auteur d'Ultramarine de «pensée de seconde main» (2), ne se dépêcherait pas bien vite de déposer aux pieds de l'idole le fardeau trop pesant, enchaînant ainsi la liberté à la seule discipline stupide des masses. Tout lecteur de La révolte des masses aime je crois, en tout premier lieu, l'écriture de ce livre érudit, pressé, menaçant, parfois prodigieusement lucide et même, osons ce mot tombé dans l'ornière journalistique, prophétique.

Sans doute le grand romancier trouva-t-il aussi dans le livre du philosophe, comme le remarque José Luis Goyenna dans son intéressante (quoique pleine de fautes) préface, en plus d'images étonnantes bien propres à enthousiasmer l'écrivain, une authentique philosophie de la liberté comme accomplissement métaphysique du moi qui, à la différence de celle de Sartre qualifiée par l'auteur d'Ultramarine de «pensée de seconde main» (2), ne se dépêcherait pas bien vite de déposer aux pieds de l'idole le fardeau trop pesant, enchaînant ainsi la liberté à la seule discipline stupide des masses. Tout lecteur de La révolte des masses aime je crois, en tout premier lieu, l'écriture de ce livre érudit, pressé, menaçant, parfois prodigieusement lucide et même, osons ce mot tombé dans l'ornière journalistique, prophétique.

Hervé Juvin n’est pas qu’un économiste, ni uniquement un essayiste, non plus seulement le président d’Eurogroup Institute, il est encore et surtout un analyste incomparable, aussi lucide que courageux, du monde comme il ne va plus.

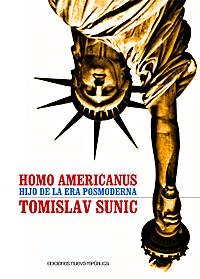

Hervé Juvin n’est pas qu’un économiste, ni uniquement un essayiste, non plus seulement le président d’Eurogroup Institute, il est encore et surtout un analyste incomparable, aussi lucide que courageux, du monde comme il ne va plus.  « (…) Tout dans l’Amérique est une copie grotesque de la réalité », constate l’universitaire et géopoliticien Tomislav Sunic dans Homo americanus, rejeton de la postmodernité, passionnante étude que viennent de publier les éditions Akribeia. « L’Amérique postmoderne fonctionne depuis 1945 comme une photocopie géante de la métaréalité ; non l’Amérique telle qu’elle est, mais l’Amérique telle qu’elle devrait être dans le monde entier. La seule différence est que, au XXIe siècle, l’histoire (…) est passée à la vitesse supérieure. Les événements se succèdent de façon désordonnée et foncent à toute allure vers un chaos total » – ce « chaos total » que l’idéologue néo-conservateur Michael Ledeen, pilier de la World Jewish Review et l’un des principaux inspirateurs de George W. Bush dans la guerre contre l’Irak, appelait de ses vœux dès 2001 car il y voyait le seul moyen d’instaurer un gouvernement mondial.

« (…) Tout dans l’Amérique est une copie grotesque de la réalité », constate l’universitaire et géopoliticien Tomislav Sunic dans Homo americanus, rejeton de la postmodernité, passionnante étude que viennent de publier les éditions Akribeia. « L’Amérique postmoderne fonctionne depuis 1945 comme une photocopie géante de la métaréalité ; non l’Amérique telle qu’elle est, mais l’Amérique telle qu’elle devrait être dans le monde entier. La seule différence est que, au XXIe siècle, l’histoire (…) est passée à la vitesse supérieure. Les événements se succèdent de façon désordonnée et foncent à toute allure vers un chaos total » – ce « chaos total » que l’idéologue néo-conservateur Michael Ledeen, pilier de la World Jewish Review et l’un des principaux inspirateurs de George W. Bush dans la guerre contre l’Irak, appelait de ses vœux dès 2001 car il y voyait le seul moyen d’instaurer un gouvernement mondial. « Pendant que les Juifs russes inventent le socialisme et que les Juifs autrichiens découvrent la psychanalyse, les Juifs américains participent, au tout premier rang, à la naissance du capitalisme américain et à l’américanisation du monde », a reconnu, cité par Sunic, Jacques Attali dans Les Juifs, le monde et l’argent (Fayard 2002). Il est donc logique que Homo americanus et Homo sovieticus aient présenté tant de points communs tels le non-respect des Conventions de Genève sur les prisonniers de guerre ou l’envoi des dissidents dans des hôpitaux psychiatriques – sort réservé en 1945 à Ezra Pound, le plus grand poète états-unien jugé trop favorable au fascisme italien. Et logique aussi que « l’américanisation du monde », y compris du monde ex-soviétique (par le truchement de certains oligarques patrons de presse), soit menée tambour battant.

« Pendant que les Juifs russes inventent le socialisme et que les Juifs autrichiens découvrent la psychanalyse, les Juifs américains participent, au tout premier rang, à la naissance du capitalisme américain et à l’américanisation du monde », a reconnu, cité par Sunic, Jacques Attali dans Les Juifs, le monde et l’argent (Fayard 2002). Il est donc logique que Homo americanus et Homo sovieticus aient présenté tant de points communs tels le non-respect des Conventions de Genève sur les prisonniers de guerre ou l’envoi des dissidents dans des hôpitaux psychiatriques – sort réservé en 1945 à Ezra Pound, le plus grand poète états-unien jugé trop favorable au fascisme italien. Et logique aussi que « l’américanisation du monde », y compris du monde ex-soviétique (par le truchement de certains oligarques patrons de presse), soit menée tambour battant. Fiction: en juillet 1940, Hitler parvient à forcer la main au général Franco qui laisse passer les troupes allemandes sur son territoire. Gibraltar tombe et les panzers, après avoir traversé le Maroc et l'Algérie, foncent sur Le Caire. 300.000 prisonniers français sont libérés et commis aux moissons. La popularité du vieux maréchal est au zénith. Un débarquement allemand a lieu en Irlande du Sud. Malte tombe aux mains des paras de la Luftwaffe de Goering. Churchill est mis en minorité et remplacé par Lord Halifax, qui fait la paix, en échange des puits de pétrole du Moyen Orient, qui restent sous contrôle britannique. Pourquoi faire la guerre dans ces conditions? Le succès de l'opération Barbarossa est quasi complet et, rapidement, les troupes de l'Axe font jonction dans le Caucase. Par un coup d'audace inouï (Skorzeny?), Vladivostok tombe. C'est la panique au Japon, qui se rapproche des Américains. Dans l'Empire, c'est le délire: d'ailleurs, à Berlin, on joue Sartre à guichets fermés! Dans cette atmosphère de triomphalisme, l'épuration ethnique dont sont victimes les Juiffss prend heureusement fin et l'Empire favorisera même, pour gêner les Anglais, la naissance d'un Etat hébreu, armé par l'Allemagne. A Berlin, l'aile modérée menée par Bibbentrop, le cher Otto Tabetz, ou Krommel élimine les “natzis” forcenés. Une fausse explosion nucléaire, vers 1943, calme les Américains, qui se contentent d'armer la résistance soviétique (Staline combat toujours en Yakoutie). Une vraie bombe, que le Führer obtient grâce à ses réseaux d'espions (juiffss?) aux Etats-Unis, assure définitivement la neutralité américaine. Hitler meurt le 30 décembre 1946, à la veille du réveillon. Speer, l'amiral Panaris et surtout Gersdorff entreprennent une première “dénatzification” et, de 59 à 78, Stendel, le Führer suivant, proscrit le racisme et le remplace par le différentialisme critériologique: les Juiffss sont incités à collaborer ou à émigrer en Israël, où ils forment une tête de pont de l'Empire.

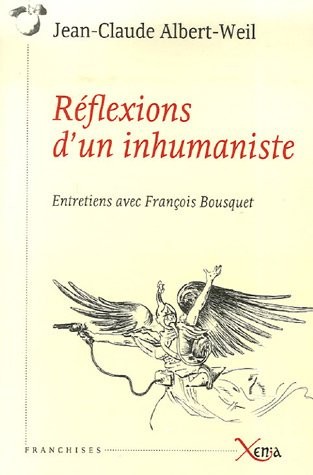

Fiction: en juillet 1940, Hitler parvient à forcer la main au général Franco qui laisse passer les troupes allemandes sur son territoire. Gibraltar tombe et les panzers, après avoir traversé le Maroc et l'Algérie, foncent sur Le Caire. 300.000 prisonniers français sont libérés et commis aux moissons. La popularité du vieux maréchal est au zénith. Un débarquement allemand a lieu en Irlande du Sud. Malte tombe aux mains des paras de la Luftwaffe de Goering. Churchill est mis en minorité et remplacé par Lord Halifax, qui fait la paix, en échange des puits de pétrole du Moyen Orient, qui restent sous contrôle britannique. Pourquoi faire la guerre dans ces conditions? Le succès de l'opération Barbarossa est quasi complet et, rapidement, les troupes de l'Axe font jonction dans le Caucase. Par un coup d'audace inouï (Skorzeny?), Vladivostok tombe. C'est la panique au Japon, qui se rapproche des Américains. Dans l'Empire, c'est le délire: d'ailleurs, à Berlin, on joue Sartre à guichets fermés! Dans cette atmosphère de triomphalisme, l'épuration ethnique dont sont victimes les Juiffss prend heureusement fin et l'Empire favorisera même, pour gêner les Anglais, la naissance d'un Etat hébreu, armé par l'Allemagne. A Berlin, l'aile modérée menée par Bibbentrop, le cher Otto Tabetz, ou Krommel élimine les “natzis” forcenés. Une fausse explosion nucléaire, vers 1943, calme les Américains, qui se contentent d'armer la résistance soviétique (Staline combat toujours en Yakoutie). Une vraie bombe, que le Führer obtient grâce à ses réseaux d'espions (juiffss?) aux Etats-Unis, assure définitivement la neutralité américaine. Hitler meurt le 30 décembre 1946, à la veille du réveillon. Speer, l'amiral Panaris et surtout Gersdorff entreprennent une première “dénatzification” et, de 59 à 78, Stendel, le Führer suivant, proscrit le racisme et le remplace par le différentialisme critériologique: les Juiffss sont incités à collaborer ou à émigrer en Israël, où ils forment une tête de pont de l'Empire.  L'Empire est résolument non humaniste et rejette sagement les droits de l'homme, qui ne sont jamais que “les droits du client”: “droit de chier des litanies de progénitures débilo-crédulo-proliférantes, pulluliques, malsaines, ivres de tuer leur prochain ou de leur passer la Grande Maladie”. Car la Maladie, venue de l'Ouest est interdite dans l'Empire: un corps d'élite veille et nettoie, liquidant impitoyablement malades infiltrés par les démothalassocrates, agents d'influence de la pourriture utilitairo-protestante et militants nationalistes (des Gagaouzes aux Vourdalaks). Pas question d'affaiblir l'Empire! Les chrétiens, et les croyeux

L'Empire est résolument non humaniste et rejette sagement les droits de l'homme, qui ne sont jamais que “les droits du client”: “droit de chier des litanies de progénitures débilo-crédulo-proliférantes, pulluliques, malsaines, ivres de tuer leur prochain ou de leur passer la Grande Maladie”. Car la Maladie, venue de l'Ouest est interdite dans l'Empire: un corps d'élite veille et nettoie, liquidant impitoyablement malades infiltrés par les démothalassocrates, agents d'influence de la pourriture utilitairo-protestante et militants nationalistes (des Gagaouzes aux Vourdalaks). Pas question d'affaiblir l'Empire! Les chrétiens, et les croyeux

Jean-Claude Rolinat a publié dernièrement, aux éditions Dualpha, une remarquable biographie d'Eva Peron.

Jean-Claude Rolinat a publié dernièrement, aux éditions Dualpha, une remarquable biographie d'Eva Peron.

There is no question for him that the liberal project is doomed: although its proponents paint it as good and inevitable, egalitarian modernity is, in fact, a highly artificial condition, an unsustainable one, which will fall victim to the very processes it set in motion. Faye believes that we are currently facing a ‘convergence of catastrophes’. These include: the colonization of the North by Afro-Asian peoples from the South; an imminent economic and demographic crisis, caused by an aging population in the West, falling birthrates, and unfunded promises made by the democratic welfare state; chaos in the countries of the South, caused by absurd Western-sponsored development and development programs; a global economic crisis, much worse than the depression of the 1930s, led by the financial sector; ‘the surge of religious fundamentalist fanaticism, particularly in Islam;’ ‘the confrontation of North and South, on theological and ethnic grounds;’ unchecked environmental degradation; and the convergence of these catastrophes against a backdrop of nuclear proliferation, international mafias, and the reemergence of viral and microbial diseases, such as AIDS. For Faye, the way out is not through reform, because a system that is contrary to reality is beyond reform), but through collapse and revolution. As a catastrophic collapse is inevitable, revolutionary thought and action must today be post-catastrophic in outlook. He further suggests that inaction on our part will only open European civilization to conquest by Islam.

There is no question for him that the liberal project is doomed: although its proponents paint it as good and inevitable, egalitarian modernity is, in fact, a highly artificial condition, an unsustainable one, which will fall victim to the very processes it set in motion. Faye believes that we are currently facing a ‘convergence of catastrophes’. These include: the colonization of the North by Afro-Asian peoples from the South; an imminent economic and demographic crisis, caused by an aging population in the West, falling birthrates, and unfunded promises made by the democratic welfare state; chaos in the countries of the South, caused by absurd Western-sponsored development and development programs; a global economic crisis, much worse than the depression of the 1930s, led by the financial sector; ‘the surge of religious fundamentalist fanaticism, particularly in Islam;’ ‘the confrontation of North and South, on theological and ethnic grounds;’ unchecked environmental degradation; and the convergence of these catastrophes against a backdrop of nuclear proliferation, international mafias, and the reemergence of viral and microbial diseases, such as AIDS. For Faye, the way out is not through reform, because a system that is contrary to reality is beyond reform), but through collapse and revolution. As a catastrophic collapse is inevitable, revolutionary thought and action must today be post-catastrophic in outlook. He further suggests that inaction on our part will only open European civilization to conquest by Islam.

VARSOVIE (NOVOpress) – Boguslaw Woloszanski, journaliste polonais, continue dans son nouvel ouvrage, 39-45 : les dossiers oubliés, aux Editions Jourdan, d’explorer les faces méconnues de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, sur la base notamment de la récente ouverture des archives de l’ex-Union Soviétique.

VARSOVIE (NOVOpress) – Boguslaw Woloszanski, journaliste polonais, continue dans son nouvel ouvrage, 39-45 : les dossiers oubliés, aux Editions Jourdan, d’explorer les faces méconnues de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, sur la base notamment de la récente ouverture des archives de l’ex-Union Soviétique.

Man mag nicht glauben, daß 56 Jahre seit der Erstveröffentlichung des vorliegenden Bandes vergangen sind! Die Fragen, denen Sieburg sich hier in neun Kapiteln (etwa »Die Kunst, Deutscher zu sein«, »Vom Menschen zum Endverbraucher«) widmet, lesen sich nicht als Rückblick auf Gefechte von gestern. Sie sind noch ebensogut unsere Themen: Identitätssuche, Vergangenheitsbewältigung, Konsumwahn, die Grenze zwischen Privatheit und Öffentlichkeit. Auch wo seine Angelegenheiten einmal der unmittelbaren Aktualität entbehren – etwa in seiner bemerkenswerten Replik auf Curzio Malaparte (d.i. K.E. Suckert) oder in seinen Einlassungen zum Verlust der Ostgebiete – nickt man staunend. Ohne Twitter oder Ryan Air gekannt zu haben, spottet Sieburg über »das Management des Vergnügens«, die »Mechanisierung der Freizeit«. Er meinte damit – wie bescheiden aus heutiger Warte! – »Betriebsausflüge an den Comer See« und Klassenfahrten in die Alpen. »Der Vorschlag, die Kinder sollten an der Nidda Blumen suchen, würde heute auf allen Seiten große Heiterkeit hervorrufen.« Für Sieburg waren die Deutschen »ein Volk ohne Mitte«: »Im Deutschen, so glaubte die Welt gestern noch, ist mehr Explosivstoff angehäuft als in jedem anderen Erdenbewohner. Hat sich diese Ansicht geändert, sind beim Anblick des fleißigen und lammfrommen Bundesdeutschen, der sogar den Karneval straff organisiert und wirtschaftsbewußt dem Konsum dienstbar macht, der das Wort Europa dauernd im Mund führt, (…) den kein Aufmarsch mit Fahnen mehr aus seinem Wochenendhaus, seinem Faltboot und Volkswagen herauslocken kann, der nur noch zu den Vertretern versunkener Fürstenhäuser und zu Filmstars aufschaut, der einen harmonischen Bund zwischen Preußentum und Nackenfett eingegangen ist, (…) der vom Golf von Neapel bis zum Nordkap die schnellsten Wagen fährt, sich in Capri bräunen läßt (…), der sich aus Ordnungssinn mit der abstrakten Kunst und dem Nihilismus beschäftigt – sind, so frage ich, beim Anblick dieses Musterknaben, der sich in der Schule der Demokratie zum Primus aufarbeitet, alle Ängste und mißtrauische Befürchtungen verschwunden? Ich antworte, nein.«

Man mag nicht glauben, daß 56 Jahre seit der Erstveröffentlichung des vorliegenden Bandes vergangen sind! Die Fragen, denen Sieburg sich hier in neun Kapiteln (etwa »Die Kunst, Deutscher zu sein«, »Vom Menschen zum Endverbraucher«) widmet, lesen sich nicht als Rückblick auf Gefechte von gestern. Sie sind noch ebensogut unsere Themen: Identitätssuche, Vergangenheitsbewältigung, Konsumwahn, die Grenze zwischen Privatheit und Öffentlichkeit. Auch wo seine Angelegenheiten einmal der unmittelbaren Aktualität entbehren – etwa in seiner bemerkenswerten Replik auf Curzio Malaparte (d.i. K.E. Suckert) oder in seinen Einlassungen zum Verlust der Ostgebiete – nickt man staunend. Ohne Twitter oder Ryan Air gekannt zu haben, spottet Sieburg über »das Management des Vergnügens«, die »Mechanisierung der Freizeit«. Er meinte damit – wie bescheiden aus heutiger Warte! – »Betriebsausflüge an den Comer See« und Klassenfahrten in die Alpen. »Der Vorschlag, die Kinder sollten an der Nidda Blumen suchen, würde heute auf allen Seiten große Heiterkeit hervorrufen.« Für Sieburg waren die Deutschen »ein Volk ohne Mitte«: »Im Deutschen, so glaubte die Welt gestern noch, ist mehr Explosivstoff angehäuft als in jedem anderen Erdenbewohner. Hat sich diese Ansicht geändert, sind beim Anblick des fleißigen und lammfrommen Bundesdeutschen, der sogar den Karneval straff organisiert und wirtschaftsbewußt dem Konsum dienstbar macht, der das Wort Europa dauernd im Mund führt, (…) den kein Aufmarsch mit Fahnen mehr aus seinem Wochenendhaus, seinem Faltboot und Volkswagen herauslocken kann, der nur noch zu den Vertretern versunkener Fürstenhäuser und zu Filmstars aufschaut, der einen harmonischen Bund zwischen Preußentum und Nackenfett eingegangen ist, (…) der vom Golf von Neapel bis zum Nordkap die schnellsten Wagen fährt, sich in Capri bräunen läßt (…), der sich aus Ordnungssinn mit der abstrakten Kunst und dem Nihilismus beschäftigt – sind, so frage ich, beim Anblick dieses Musterknaben, der sich in der Schule der Demokratie zum Primus aufarbeitet, alle Ängste und mißtrauische Befürchtungen verschwunden? Ich antworte, nein.« Müdigkeit und Geschichtslosigkeit zeige, »die mit einer nie dagewesenen Nüchternheit« gepaart sei. »Nur der Deutsche schwärzt seinen Landsmann bei Fremden an, nur der Deutsche verständigt sich lieber mit einem Exoten als mit einem politischen Gegner eigenen Stammes (…), nur der Deutsche verleugnet Flagge, Hymne und Staatsform des Mutterlandes vor Dritten.« Als »dümmstes Schlagwort« seiner Zeit erschien dem Publizisten der schon damals opportune Vorwurf, »restaurative Tendenzen« zu befördern. Alles Große, Geniale, das Heldenhafte ohnehin, dessen die Deutschen einst fähig waren, werde nun verhöhnt und gegeißelt unter dem Vorwand, »daß die alten Zeiten nicht wiederkommen dürfen«. Ja, und wie furchtbar war auch der »deutsche Spießer!« Allerdings, so Sieburg, sei zu befürchten, daß der Spießer in neuem Gewand, nämlich mit »heraushängendem Hemd« nach US-Vorbild wiedergekehrt sei, und daß die »Vorurteilslosigkeit in der Kleidung, im Umgang mit dem anderen Geschlecht und den Nerven der Mitmenschen nicht eine höhere sittliche Freiheit und einen souveränen Geist« mit sich führe.

Müdigkeit und Geschichtslosigkeit zeige, »die mit einer nie dagewesenen Nüchternheit« gepaart sei. »Nur der Deutsche schwärzt seinen Landsmann bei Fremden an, nur der Deutsche verständigt sich lieber mit einem Exoten als mit einem politischen Gegner eigenen Stammes (…), nur der Deutsche verleugnet Flagge, Hymne und Staatsform des Mutterlandes vor Dritten.« Als »dümmstes Schlagwort« seiner Zeit erschien dem Publizisten der schon damals opportune Vorwurf, »restaurative Tendenzen« zu befördern. Alles Große, Geniale, das Heldenhafte ohnehin, dessen die Deutschen einst fähig waren, werde nun verhöhnt und gegeißelt unter dem Vorwand, »daß die alten Zeiten nicht wiederkommen dürfen«. Ja, und wie furchtbar war auch der »deutsche Spießer!« Allerdings, so Sieburg, sei zu befürchten, daß der Spießer in neuem Gewand, nämlich mit »heraushängendem Hemd« nach US-Vorbild wiedergekehrt sei, und daß die »Vorurteilslosigkeit in der Kleidung, im Umgang mit dem anderen Geschlecht und den Nerven der Mitmenschen nicht eine höhere sittliche Freiheit und einen souveränen Geist« mit sich führe.