Cet article de Jean-Dominique Merchet est paru dans Marianne, n° 707 – Magazine, samedi 6 novembre 2010, p. 70.

Dans « Carnages – Les guerres secrètes des grandes puissances en Afrique », dont nous publions en exclusivité des extraits, Pierre Péan révèle les guerres secrètes que se livrent les puissances occidentales à l’ombre des massacres, dans la région des Grands Lacs. Une cynique partie d’échecs d’où les Etats-Unis, aidés de la Grande-Bretagne et d’Israël, évincent peu à peu la France.

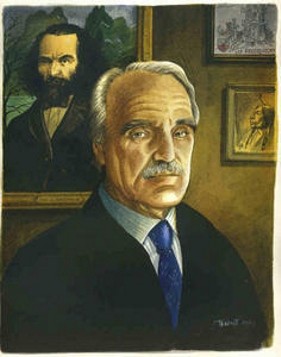

Peut-on cacher un génocide ? La question semble à peine croyable, et c’est pourtant celle qui se trouve au coeur du nouvel ouvrage de Pierre Péan, « Carnages – Les guerres secrètes des grandes puissances en Afrique ». Sur près de 600 pages, le journaliste français revient, avec de nombreuses révélations, sur les «guerres secrètes» en Afrique, en particulier dans la région des Grands Lacs.

La thèse qu’il défend – et qui ne manquera pas de provoquer de vives polémiques – est qu’à la suite du premier génocide au Rwanda, en 1994, un second a été commis, en 1996-1997, par les victimes de la veille – les Tutsis – à l’encontre des Hutus réfugiés en République démocratique du Congo (RDC, ex-Zaïre). Et que ces massacres, qui ont causé la mort de millions de personnes, se sont déroulés avec la bienveillance des Etats-Unis, quand ce n’est pas leur participation directe, comme le montrent les extraits que nous publions.

Une « question irrésolue »

Depuis 1994, la France est régulièrement accusée de complicité dans le génocide du Rwanda. Pierre Péan avait consacré en 2005 un premier livre – « Noires fureurs, blancs menteurs » (Fayard) – à la réfutation de cette thèse. Il renverse aujourd’hui carrément la table en accusant les procureurs d’être complices de massacres à grande échelle !

L’actualité sert sa thèse. Publié en août 2010, un rapport du Haut-Commissariat des Nations unies aux droits de l’homme évoque pour la première fois de manière officielle, même si c’est avec les prudences diplomatiques d’usage, la possibilité qu’un second génocide ait bien été commis par les troupes du président rwandais Paul Kagamé et de ses alliés : « La question de savoir si les nombreux graves actes de violence commis à l’encontre des Hutus (réfugiés et autres) constituent des crimes de génocide demeure irrésolue jusqu’à présent ».

En clair : on ne peut plus l’exclure ! Ce rapport a suscité la colère du Rwanda autant que la gêne chez ses alliés américains. Les soutiens français de Kigali – qui ne veulent connaître que les supposés crimes de l’armée française et les turpitudes de la politique de François Mitterrand – sont consternés.

Fidèle Israël

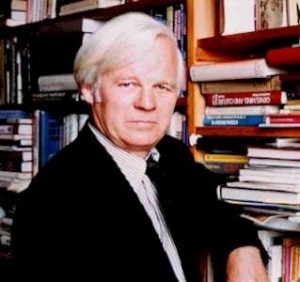

Pierre Péan, lui, jubile. Et cogne encore plus fort, au risque de prendre quelques mauvais coups. L’homme ne fait pas dans la dentelle. On lui doit des enquêtes journalistiques qui ont fait date : celle sur le passé vichyste de Mitterrand (« Une jeunesse française », Fayard, 1994), sur le journal le Monde (« La Face cachée du Monde », avec notre collaborateur Philippe Cohen, Mille et Une Nuits, 2003) ou plus récemment sur Bernard Kouchner (« Le Monde selon K », Fayard, 2009).

Mais la grande passion de ce journaliste, né en 1938, est l’Afrique, un continent qu’il arpente depuis 1962. Carnages est une somme, celle de « Pierre l’Africain », comme disent ses amis. Il y raconte le jeu des grandes puissances, Etats-Unis en tête, sur ce continent depuis la Seconde Guerre mondiale.

Son propos est centré sur la région des Grands Lacs : Rwanda, Ouganda, Soudan, RDC… Une région regorgeant de minerais et de querelles ethniques, d’ambitions politiques et de massacres à grande échelle. Des millions de civils – personne ne connaît le chiffre exact – y sont morts en une quinzaine d’années.

Ce qui révolte Pierre Péan, ce sont « les militants qui trient entre les bons et méchants morts, en usant du tamis de la repentance », comme si les « maux d’Afrique ne s’expliquaient que par un seul mot : la France ».

Cette France qui a été mise hors jeu par les Américains, à deux reprises, lorsque Jacques Chirac voulut déclencher une opération militaro-humanitaire pour venir en aide aux réfugiés (lire pages suivantes). Pierre Péan révèle par exemple comment les hommes de la DGSE infiltrés au Congo durent être rapatriés illico, sans doute à la demande de Bill Clinton.

La parution de « Noires fureurs, blancs menteurs avait valu de sérieux ennuis à son auteur, tant il remettait en cause le consensus « droits-de-l’hommiste » au sujet du Rwanda. Homme de gauche, « j’étais devenu pour une fraction de l’élite française raciste, révisionniste, négationniste et antisémite », confie-t-il. Des procès lui furent intentés, en France et en Belgique.

SOS Racisme l’accusa d’ « incitation à la haine raciale », son président, Dominique Sopo, expliquant qu’ « évoquer le sang des Hutus, c’est salir le sang des Tutsis ». Débouté en appel en novembre 2009, SOS Racisme s’est pourvu en cassation. Auprès de ses ennemis, le nouveau livre de Péan ne va pas arranger son cas.

Non seulement il s’en prend au « trucage des chiffres des victimes » par le régime rwandais, mais il décrit en détail le rôle peu connu de l’Etat d’Israël dans cette région. L’Etat hébreu, fidèle allié de Kagamé – une alliance qui va au-delà des intérêts stratégiques bien réels des parties en présence et repose sur la vision d’une concordance symbolique entre la Shoah et le génocide de 1994. Critiquer le Rwanda reviendrait en quelque sorte à s’en prendre à la Shoah…

« J’en vins à me demander s’il n’y avait pas un lien entre les attaques dont j’étais l’objet de la part de l’Union des étudiants juifs de France, de l’Union des patrons et des professionnels juifs de France et d’intellectuels comme Elie Wiesel, et l’intérêt géopolitique porté par Israël au Rwanda », s’interroge Péan.

L’enquêteur ajoute aujourd’hui une nouvelle pièce au dossier, en abordant la question du Soudan. Il établit un lien entre la volonté de l’Etat d’Israël d’affaiblir – en le divisant – le plus grand pays d’Afrique et les campagnes humanitaires, en France comme aux Etats-Unis, sur les massacres au Darfour. Voilà qui ne va certainement pas apaiser le débat… Mieux vaut donc juger sur pièces.

——————————-

EXTRAITS

Une version tronquée de l’histoire des Grands Lacs

Plus de 8 millions de morts ? Qui en parle ? Depuis la fin de la guerre froide, la région des Grands Lacs est devenue celle de la mort et du malheur dans une indifférence quasi générale.

Avec 2 millions de Rwandais exterminés en 1994 à l’intérieur du Rwanda (1), plus de 6 millions de morts rwandais et congolais dans l’ex-Zaïre, des centaines de milliers de Soudanais tués, de nombreuses victimes ougandaises, plus de un demi-million de morts angolais, des millions de déplacés, quatre chefs d’Etat et des centaines de ministres et autres dirigeants assassinés, des dizaines de milliers de femmes violées, des pillages éhontés, cette zone a le triste privilège d’avoir subi plus de dommages que ceux additionnés de toutes les guerres intervenues de par le monde depuis la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale.

Pourtant, les médias, dans leur très grande majorité, n’ont parlé, ne parlent et ne pleurent que les centaines de milliers de victimes tutsies du Rwanda, dénoncent les Hutus comme seuls responsables directs de ces boucheries, et les Français, qui les auraient aidés dans leur horrible besogne, faisant de François Mitterrand et d’Edouard Balladur des réincarnations d’Hitler, et des soldats français, celles de Waffen SS.

Une version officielle, affichée non seulement par Paul Kagamé, l’actuel président du Rwanda, mais également par le Tribunal pénal international pour le Rwanda (TPIR), le bras justicier de la communauté internationale, et par les Etats-Unis, le Royaume-Uni et la majorité des autres pays…

(1) Chiffre fourni par le ministère de l’Intérieur rwandais en décembre 1994.

Les gardiens de la vérité officielle

Convaincu par mes enquêtes que Paul Kagamé, l’actuel chef d’Etat du Rwanda, avait commandité l’attentat contre l’avion qui transportait son prédécesseur – attentat qui déclencha en avril 1994 le génocide des Tutsis et des massacres de Hutus -, quand il était attribué aux extrémistes hutus, je décidai en 2004 de chercher à comprendre ce qui s’était réellement passé.

Je découvris rapidement l’incroyable désinformation qui avait accompagné la conquête du pouvoir par Paul Kagamé, et les moyens mis en oeuvre pour décourager ceux qui seraient tentés de s’opposer à la doxa. Des moyens qui ressemblent fort à des armes de destruction massive : grâce à une analogie abusive entre le génocide des Tutsis et la Shoah, les gardiens de la vérité officielle traitent les contrevenants de négationnistes, de révisionnistes, de racistes, voire d’antisémites.

[...] J’ai décidé de reprendre mon enquête et de l’étendre en l’insérant dans l’histoire de la région des Grands Lacs et de l’Afrique centrale, pour comprendre comment et pourquoi avait pu ainsi s’installer une version tronquée de l’histoire de la tragédie rwandaise. [...]

J’ai travaillé à mettre au jour les actions – ouvertes et clandestines – des Etats-Unis, depuis les années 80, dans la région des Grands Lacs, visant à un nouveau partage des zones d’influence sur le continent africain, et le » scandale géologique » que constitue le fabuleux sous-sol du Zaïre, redevenu aujourd’hui Congo et convoité par tous. [...]

Contre-offensive impossible

Officiellement, à partir d’octobre 1996, le Zaïrois Laurent-Désiré Kabila a mené une guerre de libération en vue de chasser le président corrompu Mobutu Sese Seko. La réalité fut bien différente : Laurent-Désiré Kabila n’était alors qu’une marionnette de Kigali, de Kampala et de Washington.

Une nouvelle boucherie, après celle du Rwanda, visant cette fois à exterminer les seuls Hutus ayant fui le Rwanda, déclarés « extrémistes » par la propagande, se déroula dans un silence assourdissant des principaux médias.

Les services secrets français étaient parfaitement au courant que des forces spéciales américaines, les services secrets et des avions américains renseignaient les soldats rwandais et ougandais dans leur chasse aux Hutus dans l’immense Est congolais. L’exécutif français s’interrogea alors sur l’opportunité d’arrêter la marche de Kabila et de ses « parrains » sur Kinshasa.

La désinformation efficace sur le rôle de la France en Afrique en général et au Rwanda en particulier rendait désormais impossible toute contre-offensive, qui aurait mis face à face Français et Américains. Jacques Chirac décida in fine de ne pas envoyer de forces spéciales françaises à Kisangani début 1997.

Quand l’armée américaine participe à la traque des Hutus au Congo…

Washington porte une lourde responsabilité dans ce qu’un prérapport de l’ONU rendu public en août 2010 décrit comme un probable génocide commis en République démocratique du Congo en 1996 et 1997.

Pourquoi tant de diplomates, tant de militaires et d’agents secrets américains ont-ils été mobilisés pour parler d’une situation que les journalistes ne pouvaient directement appréhender ? Parce que la grande puissance américaine, celle qui, avec ses satellites, ses écoutes, ses hélicoptères et ses avions, aidait ceux qu’on nommait « rebelles », mais qui, en réalité, étaient en très grande majorité des Rwandais ou des Ougandais, à localiser les prétendus « génocidaires » pour les liquider.

Comment ne pas être révolté par la passivité, voire par la bienveillante sollicitude du Haut-Commissariat aux réfugiés ? Comment accepter la propagande officielle de l’époque, qui voulait que les Hutus n’eussent que ce qu’ils méritaient et que les Tutsis exerçassent là un légitime droit de revanche ? Alors que, justement, la version officielle de l’histoire, reçue et acceptée par la communauté internationale, est fausse ?

[...] Les services secrets français – Direction du renseignement militaire (DRM) et Direction générale de la sécurité extérieure (DGSE) – sont très avertis de ce qui se passe aux frontières du Kivu, fin octobre-début novembre 1996.

Le camp de Kibumba dans la région de Goma est bombardé : quelque 200.000 réfugiés partent vers le camp de Mugunga. Le camp de Katale est attaqué à l’arme lourde, et Bukavu, la capitale du Sud-Kivu, est pris par les « rebelles ». Les camps des alentours sont détruits, provoquant la fuite de 250.000 personnes à travers la forêt équatoriale vers Kisangani…

Militaires et services ne se contentent pas des images satellite fournies par les Américains, sur lesquelles on ne voit pas de réfugiés ; elles ne donnent à rien voir qui corresponde aux informations qui leur remontent du terrain, par de nombreuses sources humaines. Début novembre 1996, un Breguet Atlantic localise des cohortes de réfugiés et rapporte des photos qui montrent deux hélicoptères américains, des Black Hawks.

Poker menteur entre Paris et Washington

Les espions français s’interrogent sur le rôle des bérets verts, les commandos des US Army Special Forces, lors des massacres qui ont suivi la prise de Bukavu, fin octobre 1996. Ils se demandent aussi quelle est l’origine des mitraillages aériens opérés de nuit contre les camps de réfugiés : « Cela pose de graves questions quand on sait que parmi les avions américains déployés figurait au moins un C-130 Gunship des forces spéciales, véritable canonnière volante. Que faisait-il là si, comme le disait alors le commandement américain, il s’agissait seulement de rechercher des réfugiés pour étudier ensuite les moyens de leur porter assistance ? »

Malgré ce questionnement sur le rôle ambigu de Washington, pas plus l’état-major que les politiques français n’envisagent une quelconque action sans les Américains ou, à plus forte raison, contre eux. Mais la « forte dégradation de la situation humanitaire » entraîne les uns et les autres à envisager dans les plus brefs délais une opération militaire multinationale dans le Kivu, tout au moins à en émettre l’idée. Le Centre opérationnel interarmées (COIA) est chargé par l’état-major d’en définir les contours possibles.

Le 5 novembre, une note signée de Jean-Pierre Kelche, major général de l’état-major, arrive sur le bureau du ministre de la Défense, Charles Millon : « L’effet majeur d’une opération militaire au Kivu visera à stabiliser les réfugiés dans une zone dégagée de forces constituées ».

Les rédacteurs estiment indispensable la participation de pays européens (France, Espagne, Belgique, Allemagne et Grande-Bretagne), mais soulignent qu’un «commandement centralisé (préconisé) devrait être proposé aux Américains dont la présence au sol garantirait la neutralité rwandaise». « L’action militaire sera limitée à une sécurisation de zones, au profit des organisations humanitaires ». Le général Kelche envisage un déploiement de 1.500 à 2.000 hommes.

Le lendemain, lors d’un conseil restreint de défense, Jacques Chirac accepte les propositions du COIA, et insiste sur l’implication américaine, c’est-à-dire que « la France interviendra si les Américains interviennent avec du personnel au sol ». Et, quant à la nationalité française ou américaine du commandement de l’opération, le président n’a pas de préférence. Après le fiasco politico-médiatique, deux ans plus tôt, de l’opération «Turquoise», il n’est pas question pour la France de se lancer seule dans une telle opération…

Immédiatement après ce conseil restreint, diplomates et militaires prennent langue avec les Américains. [...] Les Français s’aperçoivent vite que les Américains, malgré quelques bonnes paroles, jouent déjà une autre partition. Si le général George A. Joulwan promet de mettre à disposition des C5 Galaxy pour projeter, si nécessaire, matériels et hommes vers le Kivu, les interlocuteurs des Français refusent d’engager leurs troupes sur le terrain.

Paris et Washington ont déjà commencé une partie de poker menteur. Alors que, sur le terrain, les acteurs rwandais, ougandais et américains ont parfaitement conscience de mener un combat indirect contre Paris, les contacts entre diplomates et militaires à Washington, Paris ou Stuttgart se déroulent entre gens de bonne compagnie.

[...] Le Monde du 8 novembre 1996 résume ainsi la situation : « La France a du mal à convaincre l’ONU de l’urgence d’une intervention au Zaïre ». Elle a du mal parce que Washington et ses alliés africains ne veulent pas que la France revienne dans la région et contrarie leurs plans, mais Paris veut croire qu’il a encore la main.

Pour ne pas s’opposer frontalement à la France, Washington monte alors une opération astucieuse destinée à enterrer le projet sans pour autant se mettre à dos l’opinion publique : elle consiste à demander au Canada de constituer cette force, d’en réunir les éléments et d’en déterminer les règles… Commence alors une grande agitation qui n’est qu’un leurre.

Politiques et militaires français n’ont pas compris tout de suite que l’opération lancée par le Premier ministre canadien Jean Chrétien à la demande des Américains ne vise qu’à enterrer le projet de Chirac et à laisser les mains libres aux Américains, ainsi qu’à leurs marionnettes rwandaises et ougandaises dans la région des Grands Lacs.

Pendant quelques jours, l’état-major croit à l’acceptation d’un déploiement d’une force franco-britannique sous commandement canadien dans la région sud du Kivu. A preuve, une mission de reconnaissance effectuée par des militaires britanniques, sous le commandement du brigadier général Thomson (Royal Marines), avec trois officiers français, dirigés par le colonel Philippe Tracqui, qui est le numéro 2 du Centre opérationnel de l’armée de terre (Coat).

Dès le début, Tracqui et ses deux compagnons ont compris que quelque chose ne collait pas. [...] Le rapport de Tracqui, daté du 21 novembre, lève les dernières interrogations sur la place désormais accordée à la France dans les Grands Lacs et sur les manoeuvres américaines. «Les Américains sont tout à fait opposés à une action militaire au Sud-Kivu», écrit Tracqui. [...]

Thomson a donné à Tracqui un mémorandum du général Smith, rédigé le 16 novembre à Entebbe, qui dévoile la position américaine. « Depuis vingt-quatre heures, la situation s’est arrangée, tout va bien à Goma, et la nature des besoins humanitaires s’en trouve changée. Bien qu’il ne soit pas encore possible d’apprécier exactement le nombre total des réfugiés qui vont rentrer ou ceux qui auraient l’intention de le faire dans les prochains jours, il est clair qu’il n’existe plus en ce moment de crise humanitaire justifiant une action militaire d’urgence », écrit le général américain qui ne réclame donc aucun moyen supplémentaire.

[...] Le soir de ce 16 novembre 1996, à Entebbe, le général américain Smith dirige une réunion de planification à laquelle participe le lieutenant-colonel Pouly, de la Direction du renseignement militaire française. Pouly [...] sait que la situation décrite par l’Américain est fausse. Il ose prendre la parole après le général américain et lui fait remarquer que son appréciation de la situation ne fait aucun cas des 700.000 réfugiés et 300.000 déplacés du Sud-Kivu.

Le numéro 2 du Coat rapporte toutes les informations fournies par Pouly, le meilleur spécialiste militaire français de la région des Grands Lacs. Pouly est convaincu que « les Américains présents dans la région des Grands Lacs, qu’il s’agisse des diplomates de Kigali ou des militaires isolés à Entebbe, ne souhaitent aucune présence dans la région ».

Il a noté « l’existence à Kigali d’une importante mission militaire de coopération américaine qui a compté jusqu’à 50 personnels. Elle s’occupe de la formation militaire de l’APR [l'Armée patriotique rwandaise], fait de l’instruction de déminage, de la formation à l’action psychologique avec des spécialistes appartenant au 4e bataillon de Fort Bragg, notamment pour ce qui concerne les opérations de propagande liée à l’organisation des retours ». L’espion français a appris que « les équipes psyops américaines, chargées des opérations psychologiques, c’est-à-dire d’influencer l’opinion, sont en place et opèrent à partir de Kigali, depuis trois mois ».

L’initiative de la France pour venir en aide aux réfugiés rwandais a été brisée dans l’oeuf, au grand soulagement des Etats-Unis, du Rwanda et de l’Ouganda.

Décrédibilisée par l’action de tous les psyops rwandais et américains relayés par les porte-voix occidentaux du Front patriotique rwandais, le parti du président Kagamé, et par la plupart des médias, y compris par de nombreuses bonnes âmes françaises, la France n’a rien pu faire pour stopper les massacres de masse organisés de Hutus. Les massacres vont donc pouvoir se poursuivre, après l’enterrement sans fleurs ni couronnes de la force multinationale.

Quelques notes subtilisées aux services secrets ougandais et rwandais montrent même un engagement américain et britannique beaucoup plus accentué. Les moyens qui ont été mis en oeuvre sont énormes. Un réseau ultramoderne de satellites espions (intelligence communication network), couvrant la zone de Kigali à Brazzaville pour recueillir, contrôler et neutraliser toutes les informations en langues française et locales, a bien été déployé pour le compte des Américains, des Britanniques et des Ougandais.

Pas d’objection à l’ « anéantissement »

Selon les documents ougandais et rwandais, des avions américains seront spécialement affectés à la traque des Hutus qui se cachent dans les forêts (Report 678 ref 567/JL/RW/UG) : « Il a été conclu que les forces aériennes américaines enverront 3 P-3 Orion Propeller Planes à Entebbe. Ils opéreront pendant la journée d’Entebbe au Zaïre, à la recherche des Hutus qui se cachent dans les forêts. Les avions seront équipés de trois équipements [il s'agit en réalité de trois spécialistes chargés de contrôler une cinquantaine d'ordinateurs] destinés à traquer les mouvements des gens sur le terrain ».

Concoctés par Paul Kagamé, les plans d’attaque et de démantèlement des camps de réfugiés hutus dans l’ex-Zaïre sont présentés aux Américains pour approbation, comme le montre une note (Plan 67 ref 67/JL/RW/ZR) : « Les plans visant à attaquer les Hutus dans l’est du Zaïre ont été finalisés. Octobre et novembre 1996 sont les meilleurs mois pour l’opération. L’ONU sera engagée dans le processus de fournir les prochaines livraisons de vivres et nous saboterons ce processus ».

Une réunion entre services ougandais et rwandais (Crisis 80/L ref 78/RW. Doc) définit le modus operandi d’une action dans laquelle 30 soldats rwandais vont monter une attaque déguisés en miliciens hutus : « Il y a besoin de liquider les Hutus Interahamwe [miliciens impliqués dans le génocide de 1994] dans l’est du Zaïre. Nous avons pénétré les camps de réfugiés de Katale et Kahindo. Nous allons aider le Rwanda à exécuter l’opération afin de forcer l’ONU à fermer les deux camps. Opération : 30 soldats de l’APR vont déclencher une attaque contre les autochtones zaïrois en se faisant passer pour Interahamwe. On procédera à la destruction de leurs propriétés. Une attaque similaire avec armes à feu sera mise en oeuvre aux heures de nuit au Rwanda. Le gouvernement du Rwanda devra alors se plaindre auprès de l’ONU. Si l’ONU est lente à réagir, une opération sans annonce préalable se perpétrera alors et anéantira toutes les milices hutues se trouvant dans ces camps. L’opération d’anéantissement est approuvée sans aucune objection ».

Les dates d’un conflit

1994, premier génocide.

Le 6 avril, l’assassinat du président du Rwanda, Juvénal Habyarimana, met le feu aux poudres. Déclenchement du génocide contre la minorité tutsie et les Hutus modérés (800.000 morts). Venu de l’Ouganda, le Front patriotique rwandais (FPR) de Paul Kagamé (Tutsi) conquiert le pays et le pouvoir. Devant l’échec de la communauté internationale, la France déclenche l’opération « Turquoise ». Des centaines de milliers de Hutus – dont certains responsables du génocide – fuient le pays vers le Zaïre, où ils s’entassent dans des camps.

1996-1997, second génocide.

La guerre se déplace dans l’est du Zaïre. Avec le soutien du Rwanda et de l’Ouganda, des Zaïrois menés par Laurent-Désiré Kabila renversent le président Mobutu. Le Zaïre devient la République démocratique du Congo (RDC). Des massacres de grande ampleur – le second génocide aujourd’hui évoqué – sont commis à l’encontre des réfugiés hutus. Les Américains empêchent, à deux reprises, une intervention française pour y mettre fin. La guerre va se poursuivre en RDC jusqu’en 2002. Elle aurait fait plusieurs millions de morts.

Lire aussi : « Noires fureurs, blancs menteurs : Rwanda 1990-1994 »

Ex:

Ex:

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Comme adjectif, le mot « chronique » désigne quelque chose qui dure longtemps. Comme une maladie, ou comme l’avenir dont chacun sait, au moins depuis Althusser, qu’il dure longtemps puisque sous ce titre il publia un livre. Précisément, les chroniques de Philippe Randa, dont il nous livre le huitième volume, concernent une maladie durable. C’est celle de notre pays. Comment nommer ce mal ?

Comme adjectif, le mot « chronique » désigne quelque chose qui dure longtemps. Comme une maladie, ou comme l’avenir dont chacun sait, au moins depuis Althusser, qu’il dure longtemps puisque sous ce titre il publia un livre. Précisément, les chroniques de Philippe Randa, dont il nous livre le huitième volume, concernent une maladie durable. C’est celle de notre pays. Comment nommer ce mal ?

Der 2009 verstorbene Philosoph Franco Volpi hatte bereits einige kleine Textsammlungen zu Arthur Schopenhauer herausgegeben, darunter Die Kunst, glücklich zu sein. Nun ist ein weiterer Band dieser Reihe erschienen. Die Kunst, sich Respekt zu verschaffen ist eine heitere Lektüre, die gegen einen Aberglauben über die Ehre ankämpft.

Der 2009 verstorbene Philosoph Franco Volpi hatte bereits einige kleine Textsammlungen zu Arthur Schopenhauer herausgegeben, darunter Die Kunst, glücklich zu sein. Nun ist ein weiterer Band dieser Reihe erschienen. Die Kunst, sich Respekt zu verschaffen ist eine heitere Lektüre, die gegen einen Aberglauben über die Ehre ankämpft. Most of my readers would agree that the West’s modern political correctness regarding race and gender is an insult to the intelligence of anyone who has given any thought to human nature and its evolutionary source. So the triumph of the PC ideology needs an explanation. With regards to feminism, Steve Moxon thinks he has an answer. In The Woman Racket, he looks to evolutionary psychology to shed light on our prejudices and documents how they lead to misperceptions about the sexes and how that in turn leads to failed policy.

Most of my readers would agree that the West’s modern political correctness regarding race and gender is an insult to the intelligence of anyone who has given any thought to human nature and its evolutionary source. So the triumph of the PC ideology needs an explanation. With regards to feminism, Steve Moxon thinks he has an answer. In The Woman Racket, he looks to evolutionary psychology to shed light on our prejudices and documents how they lead to misperceptions about the sexes and how that in turn leads to failed policy.

L’anno in cui si incontrarono, il 1928, Victoria Ocampo era una bella e ricca argentina non ancora quarantenne, sposata, ma di fatto separata e con un unico grande amore alle spalle, e Pierre Drieu La Rochelle un brillante trentacinquenne senza lavoro fisso, al secondo e già fallito matrimonio, con molte avventure sentimentali dietro di lui. Che cosa spingesse l’una nelle braccia dell’altro e viceversa non è facile dire: negli scrittori Victoria cercava gli uomini, anche se pur sempre come intesa di anime, più che di corpi; quanto a Drieu, la sua attrazione era figlia della prevenzione, il fascino esercitato da una donna intelligente, ovvero ai suoi occhi un controsenso, se non un elemento contro natura.

L’anno in cui si incontrarono, il 1928, Victoria Ocampo era una bella e ricca argentina non ancora quarantenne, sposata, ma di fatto separata e con un unico grande amore alle spalle, e Pierre Drieu La Rochelle un brillante trentacinquenne senza lavoro fisso, al secondo e già fallito matrimonio, con molte avventure sentimentali dietro di lui. Che cosa spingesse l’una nelle braccia dell’altro e viceversa non è facile dire: negli scrittori Victoria cercava gli uomini, anche se pur sempre come intesa di anime, più che di corpi; quanto a Drieu, la sua attrazione era figlia della prevenzione, il fascino esercitato da una donna intelligente, ovvero ai suoi occhi un controsenso, se non un elemento contro natura. Ma chi era veramente Victoria Ocampo, al di là dell’eco di un nome che oggi, escluso qualche specialista, evoca pallide frequentazioni letterarie fra le due sponde dell’Oceano Atlantico, il nome di una rivista, Sur, e di un collaboratore d’eccezione, Borges?

Ma chi era veramente Victoria Ocampo, al di là dell’eco di un nome che oggi, escluso qualche specialista, evoca pallide frequentazioni letterarie fra le due sponde dell’Oceano Atlantico, il nome di una rivista, Sur, e di un collaboratore d’eccezione, Borges?

La distanza, le differenze di opinioni politiche, la stanchezza che si insinua in ogni legame sentimentale, allenteranno nel tempo i rapporti, senza mai però reciderli. Negli anni ’30, un ciclo di conferenze in Argentina organizzato dalla Ocampo sarà per Drieu l’occasione per mettere a fuoco ideologie e scelte di campo: «È stato lì che ho capito che la vita del mondo occidentale stava uscendo dal suo torpore e che si apprestava ad essere lacerata dal dilemma fascismo-comunismo. Da quel momento, ho camminato rapidamente verso la caduta in un destino politico». La summa di tutto questo sarà, nel 1943, L’uomo a cavallo, storia di un dittatore boliviano che sogna l’unità del continente latino-americano e la riconciliazione delle classi sociali. Camilla, l’eroina del romanzo, è in realtà Victoria Ocampo, e naturalmente il loro è un amore destinato al fallimento. «Sarebbe ora che tu capissi che le donne sono anche esseri umani» gli aveva rimproverato un giorno... Perché Ocampo sapeva che «nella sua maniera di amare la Francia riconosco il suo modo di amare le donne che gli ho spesso rimproverato e che era poi così irritante, ma non meschino. Se Drieu è per una politica che non ci piace, non lo è per ragioni inconfessabili, basse o interessate. Un giorno gli dissi: Tu sei Pietro, e su questa pietra non costruirò la mia chiesa. Ma la mia tenerezza gli resta fedele, incurabilmente fedele».

La distanza, le differenze di opinioni politiche, la stanchezza che si insinua in ogni legame sentimentale, allenteranno nel tempo i rapporti, senza mai però reciderli. Negli anni ’30, un ciclo di conferenze in Argentina organizzato dalla Ocampo sarà per Drieu l’occasione per mettere a fuoco ideologie e scelte di campo: «È stato lì che ho capito che la vita del mondo occidentale stava uscendo dal suo torpore e che si apprestava ad essere lacerata dal dilemma fascismo-comunismo. Da quel momento, ho camminato rapidamente verso la caduta in un destino politico». La summa di tutto questo sarà, nel 1943, L’uomo a cavallo, storia di un dittatore boliviano che sogna l’unità del continente latino-americano e la riconciliazione delle classi sociali. Camilla, l’eroina del romanzo, è in realtà Victoria Ocampo, e naturalmente il loro è un amore destinato al fallimento. «Sarebbe ora che tu capissi che le donne sono anche esseri umani» gli aveva rimproverato un giorno... Perché Ocampo sapeva che «nella sua maniera di amare la Francia riconosco il suo modo di amare le donne che gli ho spesso rimproverato e che era poi così irritante, ma non meschino. Se Drieu è per una politica che non ci piace, non lo è per ragioni inconfessabili, basse o interessate. Un giorno gli dissi: Tu sei Pietro, e su questa pietra non costruirò la mia chiesa. Ma la mia tenerezza gli resta fedele, incurabilmente fedele».

Le vieil homme rentre chez lui, en ressort avec un fusil et, avant de tirer sur l’intrus, justifie son acte : « Le monde qui est le mien ne vivra peut être pas au-delà de demain matin et j’ai l’intention de profiter intensément de ses derniers instants. […] Vous, vous n’êtes pas mon semblable. Vous êtes mon contraire. Je ne veux pas gâcher cette nuit essentielle en compagnie de mon contraire. Je vais donc vous tuer. » Un peu plus tard, le professeur rejoindra la dizaine de combattants qui auront choisi de renouveler Camerone et se feront tous enterrer sous les bombes d’une escadrille française, les plus hautes autorités du pays ayant capitulé devant l’invasion.

Le vieil homme rentre chez lui, en ressort avec un fusil et, avant de tirer sur l’intrus, justifie son acte : « Le monde qui est le mien ne vivra peut être pas au-delà de demain matin et j’ai l’intention de profiter intensément de ses derniers instants. […] Vous, vous n’êtes pas mon semblable. Vous êtes mon contraire. Je ne veux pas gâcher cette nuit essentielle en compagnie de mon contraire. Je vais donc vous tuer. » Un peu plus tard, le professeur rejoindra la dizaine de combattants qui auront choisi de renouveler Camerone et se feront tous enterrer sous les bombes d’une escadrille française, les plus hautes autorités du pays ayant capitulé devant l’invasion. Alain Cotta, grand pourfendeur de l'euro devant l'Eternel, sort un nouvel ouvrage Le règne des oligarchies (éditions Plon).

Alain Cotta, grand pourfendeur de l'euro devant l'Eternel, sort un nouvel ouvrage Le règne des oligarchies (éditions Plon).

Cette vision a été élaborée en utilisant une méthodologie fondée sur de nombreux emprunts aux enseignements de Marcel Merle (1), à la méthode prospective d'Hugues de Jouvenel et à l'œuvre d'Edgar Morin avec lesquels j'ai eu la chance de partager des réflexions dans le cadre de Futuribles et de la Fondation pour les études de défense à l'époque où elle était présidée par le général Buis.

Cette vision a été élaborée en utilisant une méthodologie fondée sur de nombreux emprunts aux enseignements de Marcel Merle (1), à la méthode prospective d'Hugues de Jouvenel et à l'œuvre d'Edgar Morin avec lesquels j'ai eu la chance de partager des réflexions dans le cadre de Futuribles et de la Fondation pour les études de défense à l'époque où elle était présidée par le général Buis.

Brett and Kate McKay

The Art of Manliness: Classic Skills and Manners for the Modern Man

Cincinnati: How Books, 2009

It’s hard not to like this book. However, it’s really the idea of the book that I like, rather than the book itself. In fact, I almost hesitate to write this review (which will not be wholly positive) because I think the authors have their hearts in the right place, and because I like their website http://artofmanliness.com/

When I showed this book to a young friend of mine he was incredulous: “Do we really need a manual on being a man?” he asked. Well, yes it appears we do. As the authors say in their introduction “something happened in the last fifty years to cause . . . positive manly virtues and skills to disappear from the current generations of men.” They don’t really tell us what they think that something is, but two paragraphs later they remark: “Many people have argued that we need to reinvent what manliness means in the twenty-first century. Usually this means stripping manliness of its masculinity and replacing it with more sensitive feminine qualities. We argue that masculinity doesn’t need to be reinvented.”

I wanted to let out a cheer at this point, but I was sitting in the American Film Academy Café in Greenwich Village, surrounded by young white male geldings and their Asian girlfriends. So I kept my mouth shut and noted to myself that the McKays are clearly not PC, though there are minor nods to political correctness here are there. One gets the feeling that they know more than they are letting on in this book. And one gets the feeling they are employing a simple and sound strategy: to seduce male readers with the natural appeal of traditional manliness – while revealing just-so-much of their political incorrectness so as not to completely alienate their over-socialized readers.

Still, the McKays are pretty socialized themselves, and one sees this immediately on opening the book and finding that it is dedicated to two members of “the greatest generation.” Ugh. Yes, I do think there’s much to admire about my grandfather’s generation, but I long ago came to detest the conventional-minded romanticism about America’s great crusade in WWII. And the very use of the phrase “greatest generation” has become a cliché.

However, the real trouble begins after the introduction, when one finds that the first section of the book is devoted to how to get fitted for a suit. Then we are instructed in how to tie a tie. For some unaccountable reason the tying of the Windsor knot is included here. (Like Ian Fleming, I have always regarded the Windsor knot as a mark of a vain and unserious man.) This is followed by sections on how to select a hat, how to iron a shirt, how to shave, and how not to be a slob at the dinner table. So far so good: I know all this stuff, so I guess I’m pretty manly. Of course, the problem here is that this is all in the realm of appearance. To be fair, the McKays do go on to include much in their book about character, but one must wade through a lot of inessential stuff to get there.

At one point we are instructed in how to deliver a baby. The McKays’ core piece of advice here is “get professional help!” Curiously, this is also the central tenet of their brief lectures on dealing with a snakebite and landing a plane. The baby having been delivered, the reader will find further instructions on how to change a diaper and how to braid your daughter’s hair. (This is what happens when you co-author a book with your wife.) The McKays’ advice on raising children is sound. They advise us not to try and be our child’s best friend.

Once you have tended to your daughter’s snakebite and braided her hair (in that order, please), you can turn to manlier things like how to win a fight, how to break down a door, how to change a flat tire, how to jump start a car, how to go camping, how to navigate by the stars, and how to tie knots. Then it will be Miller time, and you will want some manly friends to hang out with.

The section on male friendship, in fact, is one of the best parts of the book. The McKays remind us that in ancient times “men viewed male friendship as the most fulfilling relationship a person [i.e., a man] could have.” They attribute this, however, to the fact that men saw women as inferior. This is at best a half-truth. The real reason men saw male friendship as more fulfilling than relations with women is because it is. There are vast differences between men and women, and while they may be able to have close, loving relationships they never really understand each other, and their values clash.

Women are primarily concerned with the perpetuation of the species. They are the peacemakers, who just want us all to get along, because their main concern is what Bill Clinton called “the children.” By contrast, men find their greatest fulfillment in achieving something outside the home: they are only fully alive when they are fighting for some kind of value. A man can only be truly understood by another man.

Thus was born what the McKays refer to as “the heroic friendship”: “The heroic friendship was a friendship between two men that was intense on an emotional and intellectual level. Heroic friends felt bound to protect one another from danger.” The McKays devote some discussion to the decline of close male friendships, and they have a lot to say about the disappearance of affection among male friends.

A while back I found myself in a bookstore flipping through a book of photographs from WWII. Many of them depicted soldiers, sailors, and marines relaxing or goofing around. What was remarkable about many of these pictures was the affection the men displayed for one another. There was one photo, for example, of a sailor asleep with his head in another sailor’s lap. This is the sort of thing that would be impossible today, because of fear of being thought “gay.” The McKays mention this problem. As George Will once said, the love that dare not speak its name just can’t seem to shut up lately. And it has ruined male bonding. Thus was born the “man hug” with the three slaps on the back that say I’M (THUMP) NOT (THUMP) GAY (THUMP). (Yes, the McKays instruct us on how to perform the man hug in both its American and international versions.)

Another thing that has ruined male friendships is women, but in a number of different ways. First of all, as every man knows, women have now invaded countless previously all-male areas in life. This usually results in ruining them for men. Second, many women resent it when their husbands or partners want to spend time with their male friends. In earlier times, men would spend a significant amount of time away from their wives working or playing with male peers. But no longer. Now women expect to be their husband’s “best friend,” and men today passively go along with this. The result is that they often become completely isolated from their male friends. It is quite common today, in fact, for men to expect that marriage means the end of their friendship with another man. Please note that all of the above problems have only been made possible by the cooperation of men – by their not being manly enough to say “no” to women.

Eventually, one finds the McKays dealing with matters having to do with manly character, such as their discussion of the characteristics of good leadership. A lot of what they have to say is sound advice, but it is not without its problems. At one point they invoke old Ben Franklin and his homey list of virtues. Anyone interested in this topic should read D. H. Lawrence’s hilarious demolition of Franklin in Studies in Classic American Literature. Franklin is the archetypal American, extolling (among other things) temperance, frugality, industry, and cleanliness. This is setting our sights very low, and it’s not the least bit manly. If I’m going to take lessons in manliness from an American I’d much rather get them from Charles Manson.

There are other problems I could go on about, such as the McKays advising us to give up porn because it “objectifies women” (“But that’s the whole point!” a friend of mine responded when I told him this). However, as I said earlier, their heart is in the right place. Whatever its flaws, this book is a celebration of traditional manhood and an honest, well-intentioned attempt to improve men.

Still, there is something undeniably creepy and postmodern about this book. If you follow all of its instructions you won’t be a traditional manly man, you’ll be an incredible, life-like simulation of one. The reason is that everything they talk about came naturally to our forebears. It flowed from their characters, and their characters flowed from their life experience. But their life experience was quite different from ours. They were not constantly shielded from danger and from risk taking. They had myriad ways open to them to express and refine their manly spirit. They had manly rites of passage. Their spirits were not crushed by decades of PC propagandizing. They had been tested by wars, famines, depressions. They were tough sons of bitches, and nobody needed to tell them how to win a fight. And if you tried to tell them how to braid their daughters’ hair you’d better be ready for a fight.

True manliness is not the result of acquiring the sort of “how to” knowledge the McKays try to provide us with. Manliness is not an art, not a techne – but it’s inevitable that we moderns, even good moderns like the McKays, would think that it is. Manliness is a way of being forged through trials and tribulations. In a world without trials and tribulations, in the “safe” and “nice” modern, industrial, liberal, democratic world it’s not at all clear that true manliness is possible anymore. Except, perhaps, through rejecting that world. The subtext to The Art of Manliness is anti-modern. But the achievement (or resurrection) of manliness has to raise that anti-modernism out from between the lines and make it the central point.

At its root, modernity is the suppression of manly virtues and manly values. This is the key to understanding the nature of the modern world and our dissatisfaction with it. Manliness today can only be truly asserted through revolt against all the forces arrayed against manliness – through revolt against the modern world .

.