Introduction to Guillaume Faye’s book Convergence of Catastrophes, published by Arktos Media

An Explosive Cocktail

‘The modern world is like a train full of ammunition running in the fog on a moonless night with its lights out.’ (Robert Ardrey[1])

For the first time in its history, humanity is threatened by a convergence of catastrophes.

For the first time in its history, humanity is threatened by a convergence of catastrophes.

A series of ‘dramatic lines’ are approaching one another and converging like a river’s tributaries with perfect accord (between 2010 and 2020) towards a breaking point and a descent into chaos. From this chaos — which will be extremely painful on the global scale — can emerge the new order of the post-catastrophe era and therefore a new civilisation born in pain.

Let us briefly summarise the nature of these lines of catastrophe.

The first is the cancerisation of the European social fabric. The colonisation of the Northern hemisphere for purposes of permanent settlement by the peoples of the global South, which is increasingly serious despite the reassuring affirmations of the media, is pregnant with explosive situations; the failure of the multiracial society, increasingly full of racism of all kinds with different communities becoming more and more tribal; the progressive ethnic and anthropological metamorphosis of Europe, a true historical cataclysm; the return of poverty to Western and Eastern Europe; the slow but steady growth of criminal activity and drug use; the continual disintegration of family structures; the decline of educational infrastructure and the quality of academic programs; the disruption of the transmission of cultural knowledge and social disciplines (barbarisation and loss of needed skills); the disappearance of popular culture and the increasing degrading of the masses by the culture of spectacles.[2] All this indicates to us that the European nations are moving toward a New Middle Ages.[3]

But these factors of social breakdown in Europe will be aggravated by the economic and demographic crisis which will only get worse and end by producing mass poverty. By 2010 the number of active workers will not be large enough to finance the retirements of the ‘grandpa boomers’. Europe will collapse under the weight of old people; then its ageing countries will see their economies slowed and handicapped by payments for healthcare and retirement benefits for unproductive citizens; in addition, the ageing of the population will dry up technical and economic dynamism. In addition to these problems, the economy will increasingly resemble the Third World because of the uncontrolled immigration of unskilled populations.

Modernity’s third dramatic line of catastrophe will be the chaos of the global South. By displacing their traditional cultures with industrialisation, the nations of the South, in spite of a deceptive and fragile economic growth, have created social chaos that is only going to get worse.

The fourth line of catastrophe, which has recently been explained by Jacques Attali,[4] is the threat of a world financial crisis, which will be much more serious than the crisis of the 1930s and will bring about a general recession. The harbinger of the crisis will be the collapse of the stock markets and currencies of the Far East, like the recession that is striking this region.

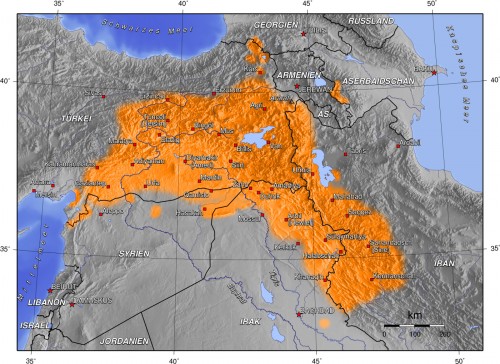

The fifth line of catastrophe is the rise of fanatical religious cults, principally Islam. The rise of radical Islam is the backlash to the excesses of the cosmopolitanism of modernity that wanted to impose on the entire world the model of atheist individualism, the cult of material goods, the loss of spiritual values and the dictatorship of the spectacle. In reaction to this aggression, Islam has radicalised, just as it was already becoming once again a religion of domination and conquest, in conformity with its traditions.

The sixth line of catastrophe: a North-South confrontation, with theological and ethnic roots, will appear on the horizon. It is increasingly likely to replace the risk of an East-West conflict, which we have so far avoided. No one knows what form it will take, but it will be serious, because it will be based on collective challenges and sentiments much stronger than the old and artificial partisan polarity of the USA and USSR, capitalism and Communism.

The seventh line of catastrophe is the uncontrolled increase of pollution, which will not threaten the Earth (which still has four billion years to look forward to and can start evolution over again from zero), but the physical survival of humanity. This collapse of the environment is the fruit of the liberal and egalitarian myth (which was once also a Soviet myth) of universal industrial development and a dynamic economy for everyone.

We can add to all this the probable implosion of the contemporary European Union, which is increasingly ungovernable, the risks involved with nuclear proliferation in the Third World, and the probability of ethnic civil war in Europe.

The convergence of these factors in the heart of a globalised and very fragile civilisation allows us to predict that the Twenty-first century will not be the ‘progressive’ continuation of the contemporary world, but the rise of another world. We must prepare ourselves for this tragic possibility with lucidity.

Believing in Miracles

We are dealing with a general prejudice inherited from the egalitarian and humanitarian utopias, like the philosophy of Progress, according to which ‘we can have everything at the same time’ and that reality never has negative consequences.

People believe they can have their cake and eat it too. They imagine, according to the liberal faith, that an ‘invisible hand’ will spontaneously restore a harmonious equilibrium. I shall mention a few examples of believing in miracles:

• Imagining that the dogma of the unlimited economic development of every nation is possible without massive pollution and ecological catastrophes that will destroy this very development. This is the illusion of indefinite development.

• Believing that a permissive society will not produce a social jungle, and that you can obtain at the same time libertarian emancipation and self-disciplined harmony. We see this drama being acted out in the shipwreck of our schools, where violence, insecurity, ignorance, and illiteracy are arising out of the illusion of progressive education, an educational method which rejects any form of discipline for its students.

• Believing that it will be possible to preserve retirement systems and social and medical entitlements while remaining faithful, in a period of demographic decline, to the ideal of ‘solidarity of distribution’. This is the illusion of the Communist conception of solidarity.

• Believing that large-scale alien immigration is compatible with the ‘values of the French Republic’ and the preservation of the civilisation of the nations and peoples of Europe; and that Islam can become secular and blend in with republican values. Believing also that we can renew the working population by importing immigrants, when these immigrants are unskilled welfare recipients and our responsibility. Imagining also that by regularising the status of masses of illegal immigrants, it will be possible to assimilate them and avoid the arrival of new masses, although we observe exactly the opposite. This is the illusion of the benefits of immigration.

• Extolling the assimilation and integration of aliens while wanting to preserve and maintain their special characteristics, their original cultures, their memories and native mores. This is the communitarian illusion, one of the most harmful of all, which is particularly cherished by ‘ethno-pluralist’ intellectuals.

• Imagining that by cancelling Third World debt we can encourage their economic growth and prevent new indebtedness in the future. This is the Third Worldist illusion.

• Demanding at one and the same time that we abandon nuclear energy programs and replace them with power plants using natural gas, coal and petroleum, while advocating the reduction of polluting gases. This is the ecologist’s illusion.

• Thinking that a world economy founded on short term speculation based on computerised markets and replacing monetary policies with the caprice of financial markets will guarantee a lasting ‘new growth’. This is the illusion of the new economy.

• Believing that democracy and ‘republican values’ will be reinforced by eliminating ‘populism’, that is, the direct expression of the will of the people.

I could make the list longer. In all these matters, believing in miracles can be explained by the incorrigible optimism of the secular religion of egalitarian progressivism, but also by the fact that, although it has reached an impasse, the dominant ideology does not dare deny its dogmas or make heartbreaking revisions, while clinging to the idea that ‘the storm will never come’. The whole thing is explained by the sophisms of bogus experts, whose conclusions are always that everything is going well and getting better and that we have the situation under control. They are like a driver who speeds through a red light and justifies it by explaining that the faster he drives, the less time he spends in the intersection and therefore reduces the risk of a collision.

Man, a Sick Animal

Paul MacLean,[5] Konrad Lorenz,[6] Arthur Koestler,[7] and Jean Rostand[8] have sensed that man is a sick animal, endowed with a brain that is too large. Conscience is perhaps, on the evolutionary scale, an illness and intelligence a burden. Man has lost touch with his natural survival instincts. We have not been on the Earth for a long time and it may be that, from life’s point of view, or Gaïa’s,[9] we are a failed species, an abortive experiment; and that, especially by destroying the ecosystem that supports it, the suicidal human race is hastening its own disappearance.

Our neocortex, which some biologists compare to a tumour, does not function sufficiently in symbiosis with our reptilian brain. This is ‘cerebral schizo-physiology’, the source of a chaotic and self-destructive culture: wars, religious fanaticisms, frenzied exploitation of nature, aberrant demographic proliferation or, on the other hand, catastrophically low birth levels, frustrating natural selection, etc.: Homo sapiens sapiens does not deserve the name he has given himself. He is not ‘wise’, only intelligent. But he will perhaps perish from this excessive intelligence, which is pushing him to excess, hybris[10], and is making him lose every instinct of collective survival and all capacity to ‘feel’ the dangers that are piling up.

The Golem Parable, or the Machine that Went Mad

Humanity has lost control of the forward rush of the technological and globalised civilisation born in the Nineteenth century. We should remember the parable of the Golem, the Jewish allegory from Prague, in which a mud figure brought to life by magic escapes its maker, becomes an autonomous and out of control entity, and then starts spreading terror.

Today’s little Jules Vernes[11] are mistaken. Optimistic and short-sighted mechanics, they are only making the situation worse. More than that, they are not in control of the machine and have no idea where it is heading. There really is a pilot in the airplane, but he is convinced that he is driving a locomotive.

Among the inescapable trends at work today, there are other risks that are unforeseeable today but which will make things worse (or perhaps better, but this is less likely), or else create new tendencies or new earth-shattering phenomena. At any rate, it is hard to see any positive signs. All the indictors are flashing red.

In futurology, there are only two types of extrapolation from current trends that one can make with a high degree of probability: the weak and the strong. Today predictions are typically based on weak extrapolations. These latter are, for example, the pursuit of economic growth, linear and continuous technological progress, scientific civilisation, the affirmation of democracy everywhere in the world (who is telling us that Europe will be ‘democratic’ in 2030?); the lasting character of the United Nations; the effectiveness of antibiotics in the next century, and so on.

We are less concerned with strong extrapolations, which have a good chance of being realised in the next twenty years: the demographic disequilibrium of North and South that will grow massively; the unavoidable ageing of the indigenous European population; the growth of mass immigration into rich countries; the worsening of pollution, atmospheric warming and the exhaustion of resources, which is growing worse regardless of what measures may be taken today on a global level (and they are not being taken); the rising power of Islam; the worsening of social disintegration in Europe along ethnic lines, etc. All these strong extrapolations are headed in the direction of the system’s breakdown, and are what we might call ‘pessimistic’.

The ‘Billiard Ball’ Theory

The current implicit ideology that dominates the world, especially in the West, still continues to profess, officially, the utopia inherited from the egalitarian philosophy of the Enlightenment (Eighteenth century), positivism[12] and scientism (Nineteenth century): to create a situation where, in a few decades from now, some eight billion people will live on the planet with a good standard of living and democracy for all. All this resembles the billiard player who imagines that after four or five rebounds his ball will automatically fall into the hole. These professors of ballistics are playing golf, but they do not know it.

It is a quasi-certainty that this persistent belief in progress and modernity, concepts which the political classes of the West are always jabbering about and which are totally obsolete, will never see its objectives occur. The dream will shatter into pieces. Constraining forces, a physical wall, makes this ideology resemble a mass of intellectual stupefaction and belief in miracles.

The demanding parameters, mentioned above, based upon the assumption that current realities will persist and that current projections for the future will be realised, are not taken into account. No one is looking at the dashboard or the fuel gauge. Only the short-term counts, but for how much more time? The majority of the elites do not concern themselves with the long term, or even the middle term, in this civilisation of the here and now. The fate of future generations does not interest the decision-makers at all. They care only about their own careers.

* * *

They are helped by the experts in every field, who practice constant disinformation and censorship of pessimism, taking advantage of the good old Coué method of optimistic autosuggestion:[13] ‘Everything is going badly, so, to reassure myself, I say that everything is going well.’ Actually pessimism would be more convincing, since it incites people to improve matters and to try to cure the disease. Alas, I think that is already too late. We have passed the point of no return.

The majority of intellectuals, media people, politicians and businessmen maintain a language of utopian optimism, clinging to their dogmas and making a gross travesty of reality: ‘republican assimilation is making progress and will continue to make progress in France’; ‘we are on the path to control massive illegal immigration’; ‘Islamism is in decline’; ‘we are on track to win the war on terror’; ‘economic growth will resume next year and, because of the economic recovery, unemployment will go down’ (when tomorrow comes, erasing it will cost nothing); ‘we are going to establish democracy in the Near East’; ‘we can stop using nuclear power and reduce pollution by making more efficient use of other resources, even if we go back to power plants that use petroleum, natural gas and coal’; ‘we are going to find the money to pay for the costs of healthcare insurance without increasing public borrowing’; and so on.

We go forward each time either by lying and misrepresenting the objective situation, or by deliberately ignoring the parameters and changes that are taking place.

If elites of all different kinds pretend to believe this nonsense, public opinion (once upon a time we used to say, ‘the people’) subscribes to it less and less. Pessimism is present everywhere, like a sort of presentiment of a coming apocalypse. Already in 1995, an IFOP[14] poll published in the Leftist newspaper Libération revealed that to the question, ‘In ten years will we live in a better world?’ 64 % of those polled responded in the negative. They were not mistaken.

‘Catastrophe Theory’ and ‘Discrete Structural Metamorphoses’

In his ‘catastrophe theory’ French mathematician René Thom[15] explained that a ‘system’ (whether physical-chemical, mechanical, climatic, organic, social, civilisational, etc.) is an always fragile ensemble that can suddenly lurch into chaos, without anyone anticipating it, as a result of an accumulation of factors. It is the famous ‘drop of water that causes the cup to overflow’. Every system is unstable and every civilisation is mortal, like everything in the universe. But sometimes the collapse is violent and sudden. For a long time a system can be worn away from inside by an endemic crisis; it holds out for a long time and then, suddenly, everything tips over. We find here the law of viral and bacterial biology: incubation is slow, but the final attack is as fast as lightning. A tree, apparently in good health, falls down during the first storm, although no one suspected that its insides were eaten away.

History offers us examples of sudden and unforeseen collapses: the Amerindian civilisation after the Spanish invasion, or else the Egyptian empire facing the assault of the Romans. I am defending the thesis that this is what awaits today’s global civilisation in the next twenty years. We are going to hit a very sudden breaking point arising from the simultaneous convergences of great crises. It is easy to envisage spectacular and rapid historical reversals.

* * *

It is always necessary to beware of surprises, these unforeseen and sometimes discrete transformations, which turn everything upside down. They radically modify a system’s structure, without making a loud noise and suddenly, their consequences explode and change everything. That is what is heading for us today. They are ‘discrete structural metamorphoses’.

We believe that we are still living in world X, when we are already in world Y, and the house of cards of the old world collapses without warning. These metamorphoses do not always make the front pages of newspapers; they take place without making a fuss. They constitute history’s infrastructure, not its ephemeral surface.

The founding of the Fifth Republic,[16] the fall of Communism, the results of American elections, etc., are events that depend on the superstructure. On the other hand, what we have called the ‘discrete structural metamorphoses’ will have incalculable consequences. For a generation they have been increasingly frequent and rapid. They are transforming the face of our civilisation.

Let us mention some cases. In France and Belgium, and soon in other countries, the number of active practitioners of Islam is soon going to surpass that of the Christian churches; the depopulation of Europe has begun as the radical ethnic modification of its population; the Spanish language has already equalled and even surpassed English in the American Southwest; some twenty nations possess the technology for making nuclear weapons; in a number of Western countries the traditional family is collapsing and a demographic coma is in place; the ‘casino economy’, purely speculative and unregulated, stretches over the entire world, especially in China, which still calls itself ‘Communist’; antibiotics are less and less effective against bacterial epidemics, and so on.

We are in control of none of these structural metamorphoses. And very few people are aware of the power of their interaction.

We Must Stop Believing in Sorcerers: Techno-science Gone Mad

The elites who direct the Western world, the over-credentialed ‘experts’, are pulling the wool over our eyes. They possess neither strategy nor mastery of analysis and are satisfied with tactics. The real problems are never investigated. The solutions are rhetorical or electoral. The good apostles, bureaucrats with MBAs from prestigious schools, are only masters of words. No improvement is in sight. The Golem’s inexorable march continues.

The burden of ‘doing nothing’ is the heaviest. But the experts and specialists (once called ‘savants’) are consoling us. They play the role sorcerers played in ancient societies.

* * *

No one is directing science and technology any longer and, far from improving the human condition as they used to, they are making it worse, notably by exhausting resources and destroying the environment. The modern myth of ‘development’, which is venerated more than ever all over the world, leads to its opposite, a gigantic regression, a race to the bottom. No authority, no international planning has emerged. Globalisation is anarchy. The backdrop of this fatal movement is generalised individual consumerism, the search for the highest possible standard of living, unbridled enthusiasm for the free market, the speculative economy and the cult of ‘taking each day as it comes’.

Similarly, democracy has to be seen as an aggravating factor, for this type of regime removes any central authority that can, when it sees the storm appearing, react in an emergency. Liberal democracy favours improvidence, the law of the market, and short-term calculation by individuals or corporations. If once upon a time this type of regime was efficient, today it seems incompetent, as it shows every day, to stem the rise of dangers.

International conferences on the environment are a futile waste of time. Just as there is no control over mass immigration, so the destruction of fish reserves and our forest heritage, the increased emission of greenhouse gases, the demographic gap between North and South, etc., are out of control. Even the authorities who arise to reverse the catastrophic course of events, whether they represent countries or the United Nations, do not succeed in correcting the direction of the cargo ship that is going full sail, faster and faster, towards the reefs.

* * *

But we are reassured by the ‘experts’ and are still fascinated by techno-science, believing that it will solve all our problems using some new form of magic. Computers, the electric or low-polluting engines, organic agriculture, and pharmaceutical research will not prevent the return of famines and epidemics or the exponential growth of pollution. It is too late. The machine is racing. Intellectuals and ‘philosophers’ have been telling us over and over again for decades that ‘the myth of Progress’ is dead. On the contrary, it has never been in such good shape, especially in the developing countries of the South. We are victims of the psychological condition of derealisation, a loss of the sense of reality of what is happening. Our contemporaries have persuaded themselves that ‘catastrophe cannot happen’ and that this civilisation is at the same time eternal and continually getting better and better, that it will never experience a reversal, and a fortiori[17] not a collapse. Not only is this a possibility, but it will happen, and very soon.

What comforts us in this gloomy illusion is our techno-scientific environment, which we consider to be indestructible, when on the contrary this global civilisation is a colossus with feet of clay. The politicians and the experts, who possess neither audacity nor imagination, reject every radical solution. They always prefer little solutions, tactical or rigged, compromises that please an electorate with cold feet, always respecting the status quo. They believe, like King Arthur, that ‘the fortress is impregnable’ when no one is guarding the walls.[18]

The groundswell — or rather the different groundswells arriving at the same time, demographic, strategic, sociological, economic, environmental — is arrogantly ignored. In France we even use the surreal expression ‘sustainable development’! The dominant ideology, which calls itself rationalist, is really magical. In every area it plays the role of an ‘ideology of sleep’.

* * *

We must not forget — and it is one of the central theses of this work — that mini-catastrophes reinforce one another, multiplying their effects among one another to produce a global mega-catastrophe. An accident (of an airplane, for instance) is the result of a series of causes and never just one: for example, the conjunction of a technical problem in the controls, bad weather and pilot error.

It is the same with the situation we are living through, or rather that we are soon going to be living through. For example, the natural calamities produced by global warming aggravate the famines caused by other economic and demographic causes and thus make the economic situation even worse and push the populations of the South to emigrate to the North, thus destabilising the West still more. Growing poverty in certain countries feeds religious fanaticism that, in turn, complicates political instability. And so on.

The system is holistic and interactive, which explains the acceleration of the arrival of the breaking point, since a multitude of crises converge at the same moment, without anyone being able to treat them separately.

[1] Robert Ardrey (1908-1980) was a widely read and discussed author during the 1960s, particularly his books African Genesis (1961) and The Territorial Imperative (1966). Ardrey’s most controversial hypothesis, known as the ‘killer ape theory’, posits that what distinguished humans’ evolutionary ancestors from other primates was their aggressiveness, which caused them to develop weapons to conquer their environment and also leading to changes in their brains which led to modern humans. In his view, aggressiveness was an inherent part of the human character rather than an aberration. Ardrey’s ideas were highly influential at the time, most notably in the ‘Dawn of Man’ sequence of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and also in the writings of GRECE, in which Ardrey was frequently cited.

[2] Presumably a reference to ‘society of the spectacle’, a term coined by Guy Debord (1931-1994), a French Marxist philosopher and the founder of the anarchist Situationist International. The spectacle, as described in his principal work, The Society of the Spectacle, is one of the means by which the capitalist establishment maintains its authority in the modern world — namely, by reducing all genuine human experiences to representational images in the mass media, thus allowing the powers-that-be to determine how individuals experience reality.

[3] This is a concept developed by the French author Alain Minc, in which he predicts a coming time of chaos and hardship resembling the Middle Ages, which will end in the development of a much smaller, but more sustainable, global economy. He discusses this idea in Le Nouveau Moyen-âge (Paris: Gallimard, 1993).

[4] Jacques Attali (b. 1943) is a French economist who was an advisor to Mitterrand during the first decade of his presidency. Many of his writings are available in translation. Faye may be referring to Attali’s article ‘The Crash of Western Civilisation: The Limits of the Market and Democracy’, which appeared in the Summer 1997 issue of the American journal Foreign Policy. In it, Attali claimed that democracy and the free market are incompatible, writing: ‘Unless the West, and particularly its self-appointed leader, the United States, begins to recognise the shortcomings of the market economy and democracy, Western civilisation will gradually disintegrate and eventually self-destruct.’ In many ways his arguments resemble Faye’s.

[5] Paul D. MacLean (1913-2007) was an American neuroscientist who developed the triune theory of the human brain, postulating that, over the course of its evolution, the brain was actually made up of three distinct elements: the reptilian complex, the limbic system, and the neocortex. As a result, human behavior is the product of all three tendencies.

[6] Konrad Lorenz (1903-1989) was an Austrian ethologist who won the Nobel Prize in 1973. He was a member of the National Socialist Party during the Third Reich. He speculated that the supposed advances of modern life were actually harmful to humanity, since they had removed humans from the biological effects of natural competition and replaced it with the far more brutal competition inherent in relations between individuals in modern societies. After the war, his books on popular scientific and philosophical topics earned him international fame.

[7] Arthur Koestler (1905-1983) was a Hungarian writer who, in his 1967 book The Ghost in the Machine, speculated that the triune model of the brain as described by Paul MacLean was responsible for a failure of the various parts to fully interconnect with each other, resulting in a conflict of desires within each individual leading to self-destructive tendencies.

[8] Jean Rostand (1894-1977) was a French biologist who was a proponent of eugenics as a means for humanity to take responsibility for its own destiny. He was also a pioneer in the field of cryogenics.

[9] Gaïa is the Ancient Greek name for the goddess of the Earth. In recent decades, the name has been adopted by ecologists, who use it to depict the combined components of the Earth as a living organism with its different parts acting in symbiosis with one another, rather than as a resource merely intended to be exploited by humans.

[10] Latin: ‘pride’.

[11] Jules Verne (1828-1905) was a French novelist who is regarded as the inventor of the science fiction genre. Several of his books are notable for their predictions of future technological developments.

[12] Positivism holds that the only knowledge which can be considered reliable is that which is obtained directly through the senses and via the (supposedly) objective techniques of the scientific method.

[13] Émile Coué (1857-1926) was a French psychologist whose method involved repeating ‘Every day, in every way, I am getting better and better’ at the beginning and end of each day in a ritualized fashion, believing that this would influence the unconscious mind in a manner that would allow the practitioner to be more inclined toward success.

[14] The Institut français d’opinion publique, or French Institute of Public Opinion, is an international marketing firm.

[15] René Thom (1923-2002) was a French mathematician who made many achievements during his career, but is best remembered for his development of catastrophe theory. The theory is complex, but in essence it states that small alterations in the parameters of any system can cause large-scale and sudden changes to the system as a whole.

[16] The Fifth Republic began after the collapse of the Fourth Republic in 1958 as a result of the crisis in Algeria, bringing Charles de Gaulle to power and resulting in the drafting of a new constitution. It has remained in effect up to the present day.

[17] Latin: ‘an argument with a stronger foundation’.

[18] King Arthur’s Camelot was frequently left unguarded while his knights were engaged in lengthy quests.

François Lenglet est un journaliste économique compétent, honnête et de bon sens. Arrêtons-nous pour bien peser, car le phénomène ne court pas les rues : entre les spécialistes (ceux qui savent tout sur l’inessentiel et ramènent tout à leurs marottes), les mercenaires (ceux qui vendent leur salade), les demi-savants (ceux qui en savent un peu plus que les autres, sans tout à fait dominer leur sujet), les idéologues (ceux qui ont la réponse avant la question) et les Guignols de l’Info, la place est mince pour ceux qui se contentent de dire simplement, honnêtement, modestement, des choses de bon sens sur des sujets compliqués. Ceci, en ayant des idées. À ce titre, soit dit en passant, François Lenglet, journaliste économiste, est un peu le frère jumeau de Christian Saint-Étienne, économiste communicant.

François Lenglet est un journaliste économique compétent, honnête et de bon sens. Arrêtons-nous pour bien peser, car le phénomène ne court pas les rues : entre les spécialistes (ceux qui savent tout sur l’inessentiel et ramènent tout à leurs marottes), les mercenaires (ceux qui vendent leur salade), les demi-savants (ceux qui en savent un peu plus que les autres, sans tout à fait dominer leur sujet), les idéologues (ceux qui ont la réponse avant la question) et les Guignols de l’Info, la place est mince pour ceux qui se contentent de dire simplement, honnêtement, modestement, des choses de bon sens sur des sujets compliqués. Ceci, en ayant des idées. À ce titre, soit dit en passant, François Lenglet, journaliste économiste, est un peu le frère jumeau de Christian Saint-Étienne, économiste communicant.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les médiats n’expliquent jamais que les fréquentes tueries qui ensanglantent les États-Unis seraient survenues quand bien même la détention de n’importe quelle arme aurait été proscrite. Le problème de ce pays n’est pas le nombre d’armes en circulation, mais leur usage qui témoigne de la profonde névrose de la société. Modèle planétaire de la modernité tardive, les États-Unis pressurent ses habitants au nom d’une quête à la rentabilité effrénée au point que certains voient leur psychisme flanché. La pratique dès le plus jeune âge de jeux vidéos ultra-violents, la sortie de milliers de films parsemés de scènes sanglantes et la consommation de plus en plus répandue de drogues et de produits pharmaceutiques éclairent le passage à l’acte. Entre aussi en ligne de compte la cohabitation toujours plus difficile d’une société en voie de métissage avancé fondée sur le génocide amérindien et les vagues successives d’immigration de peuplement. Enfin, le mode de vie totalitaire doux avec sa technolâtrie, son vide existentiel, son individualisme outrancier et sa compétition féroce de tous contre tous cher au libéralisme perturbe le cerveau de millions d’individus fragiles. Ce qui est arrivé, le 3 janvier 2013, à Daillon en Suisse dans le canton du Valais confirme le diagnostic : le tueur, un assisté social, alcoolique et fumeur de marijuana âgé de 33 ans, était suivi pour des troubles psychiatriques. En tant que société ouverte, la Suisse pâtit, elle aussi, de tels phénomènes qui seraient quasi-inexistants dans une société vraiment fermée.

Les médiats n’expliquent jamais que les fréquentes tueries qui ensanglantent les États-Unis seraient survenues quand bien même la détention de n’importe quelle arme aurait été proscrite. Le problème de ce pays n’est pas le nombre d’armes en circulation, mais leur usage qui témoigne de la profonde névrose de la société. Modèle planétaire de la modernité tardive, les États-Unis pressurent ses habitants au nom d’une quête à la rentabilité effrénée au point que certains voient leur psychisme flanché. La pratique dès le plus jeune âge de jeux vidéos ultra-violents, la sortie de milliers de films parsemés de scènes sanglantes et la consommation de plus en plus répandue de drogues et de produits pharmaceutiques éclairent le passage à l’acte. Entre aussi en ligne de compte la cohabitation toujours plus difficile d’une société en voie de métissage avancé fondée sur le génocide amérindien et les vagues successives d’immigration de peuplement. Enfin, le mode de vie totalitaire doux avec sa technolâtrie, son vide existentiel, son individualisme outrancier et sa compétition féroce de tous contre tous cher au libéralisme perturbe le cerveau de millions d’individus fragiles. Ce qui est arrivé, le 3 janvier 2013, à Daillon en Suisse dans le canton du Valais confirme le diagnostic : le tueur, un assisté social, alcoolique et fumeur de marijuana âgé de 33 ans, était suivi pour des troubles psychiatriques. En tant que société ouverte, la Suisse pâtit, elle aussi, de tels phénomènes qui seraient quasi-inexistants dans une société vraiment fermée.

Dès lors, débarrassé du souci fondamental de vivre, c’est-à-dire essentiellement de se préparer à l’idée de mourir, egobody, réduit à un corps formaté par les écrans, n’a plus qu’à simplement jouir. Jouir par le divertissement qui est son « tropisme principal » et l’enfonce toujours plus dans un quotidien « lunaparkisé » [

Dès lors, débarrassé du souci fondamental de vivre, c’est-à-dire essentiellement de se préparer à l’idée de mourir, egobody, réduit à un corps formaté par les écrans, n’a plus qu’à simplement jouir. Jouir par le divertissement qui est son « tropisme principal » et l’enfonce toujours plus dans un quotidien « lunaparkisé » [ Professeur de philosophie et écrivain, R. Redeker se lance dans une virulente polémique: il entend "passer au scanner" l'homme contemporain – baptisé "Egobody"– que nous serions tous devenus "à des degrés divers". Il dissèque cet homme nouveau en l'opposant à l'ancien, disparu selon lui, dans les années 1970. Les riches références philosophiques et religieuses, évitant l'écueil de la déploration moralisante, visent à nous convaincre que nous vivons une "véritable révolution anthropologique": celles du "des-humain", du "neg-humain". Toutes les valeurs, idéaux et interdits qui liaient les hommes et donnaient du sens à l'existence individuelle et collective ont disparu : les 18ème et 19ème ont annoncé la mort de Dieu, du diable et du péché originel; le 20ème celle de l'homme et des idéologies politiques... Face à cet horizon amputé de toute verticalité, de toute métaphysique, la publicité, les industries du divertissement, les nouvelles technologies ont eu le champ libre pour "fabriquer" Egobody: ayant perdu son "âme" – son for intérieur –, il ne distingue plus son "moi" de son corps: ego=body.

Professeur de philosophie et écrivain, R. Redeker se lance dans une virulente polémique: il entend "passer au scanner" l'homme contemporain – baptisé "Egobody"– que nous serions tous devenus "à des degrés divers". Il dissèque cet homme nouveau en l'opposant à l'ancien, disparu selon lui, dans les années 1970. Les riches références philosophiques et religieuses, évitant l'écueil de la déploration moralisante, visent à nous convaincre que nous vivons une "véritable révolution anthropologique": celles du "des-humain", du "neg-humain". Toutes les valeurs, idéaux et interdits qui liaient les hommes et donnaient du sens à l'existence individuelle et collective ont disparu : les 18ème et 19ème ont annoncé la mort de Dieu, du diable et du péché originel; le 20ème celle de l'homme et des idéologies politiques... Face à cet horizon amputé de toute verticalité, de toute métaphysique, la publicité, les industries du divertissement, les nouvelles technologies ont eu le champ libre pour "fabriquer" Egobody: ayant perdu son "âme" – son for intérieur –, il ne distingue plus son "moi" de son corps: ego=body.  • Prenons du recul! Pour nous alerter, Redeker nous provoque: il cultive l'excès, multiplie les généralisation hâtives et sans nuances, se fait pamphlétaire; toutefois le propos mérite réflexion. "Je suis mon corps" croit Egobody; publicité, champions, mannequins en donnent à voir une image standard: chacun tente de s'y conformer car notre corps constitue notre horizon – limité – : notre projet ne serait que de le garder jeune, séduisant et quasi-immortel. Redeker nous met en garde: cette dictature de l'apparence, les nouvelles technologies, exterminent l'intériorité de l'homme. Convaincus que l'on ne peut plus changer le monde ni se changer soi-même, nous en serions venus à n'avoir pour idéal que notre "épanouissement" personnel, dès que s'interrompt le stress du "labeur" qui, à l'inverse du travail, nous transforme en boule d'énergie sans projet. Or, se prendre soi-même pour fin ne signifie pas être heureux souligne l'auteur. Matérialiste et narcissique, consommateur d'événements festifs propres à combler son vide intérieur, Egobody ne sait plus lutter contre ses travers ni leur résister. Il s'épanouit donc au détriment d'autrui; ainsi le sport est-il dangereux qui, en développant un mental de "gagnant", transforme les partenaires en autant d' ennemis.

• Prenons du recul! Pour nous alerter, Redeker nous provoque: il cultive l'excès, multiplie les généralisation hâtives et sans nuances, se fait pamphlétaire; toutefois le propos mérite réflexion. "Je suis mon corps" croit Egobody; publicité, champions, mannequins en donnent à voir une image standard: chacun tente de s'y conformer car notre corps constitue notre horizon – limité – : notre projet ne serait que de le garder jeune, séduisant et quasi-immortel. Redeker nous met en garde: cette dictature de l'apparence, les nouvelles technologies, exterminent l'intériorité de l'homme. Convaincus que l'on ne peut plus changer le monde ni se changer soi-même, nous en serions venus à n'avoir pour idéal que notre "épanouissement" personnel, dès que s'interrompt le stress du "labeur" qui, à l'inverse du travail, nous transforme en boule d'énergie sans projet. Or, se prendre soi-même pour fin ne signifie pas être heureux souligne l'auteur. Matérialiste et narcissique, consommateur d'événements festifs propres à combler son vide intérieur, Egobody ne sait plus lutter contre ses travers ni leur résister. Il s'épanouit donc au détriment d'autrui; ainsi le sport est-il dangereux qui, en développant un mental de "gagnant", transforme les partenaires en autant d' ennemis.

Et yndet argument mod dem, der ønsker befolkningsudskiftningen og globalismen tilbagerullet, er, at det er urealistisk eller ganske enkelt ikke kan lade sig gøre. Det har derfor stor værdi, at den franske filosof Guillaume Faye nu for sit eget lands vedkommende har skrevet et meget konkret og udførligt program for national genopretning med undertitlen: ”Et revolutionært program, der ikke skal ændre spillets regler, men ændre selve spillet.”

Et yndet argument mod dem, der ønsker befolkningsudskiftningen og globalismen tilbagerullet, er, at det er urealistisk eller ganske enkelt ikke kan lade sig gøre. Det har derfor stor værdi, at den franske filosof Guillaume Faye nu for sit eget lands vedkommende har skrevet et meget konkret og udførligt program for national genopretning med undertitlen: ”Et revolutionært program, der ikke skal ændre spillets regler, men ændre selve spillet.”

Dans les années 1990, deux géopoliticiens canadiens, Gérard A. Montifroy et Marc Imbeault, publiaient cinq ouvrages majeurs consacrés à la géopolitique et à ses relations avec les démocraties, les idéologies, les économies, les philosophies et les pouvoirs dont certains furent en leur temps recensés par l’auteur de ces lignes. Aujourd’hui, Gérard A. Montifroy et Donald William, auteur du Choc des temps, viennent d’écrire un nouvel essai présentant les rapports complexes entre la géopolitique et les cultures qu’il importe de comprendre aussi dans les acceptions d’identités et de mentalités. Ils observent en effet qu’en géopolitique, « les mentalités constituaient un premier “ pilier ”, se prolongeant naturellement avec les données propres aux identités, celles-ci débouchant sur le contexte dynamique des rivalités (p. 7) ».

Dans les années 1990, deux géopoliticiens canadiens, Gérard A. Montifroy et Marc Imbeault, publiaient cinq ouvrages majeurs consacrés à la géopolitique et à ses relations avec les démocraties, les idéologies, les économies, les philosophies et les pouvoirs dont certains furent en leur temps recensés par l’auteur de ces lignes. Aujourd’hui, Gérard A. Montifroy et Donald William, auteur du Choc des temps, viennent d’écrire un nouvel essai présentant les rapports complexes entre la géopolitique et les cultures qu’il importe de comprendre aussi dans les acceptions d’identités et de mentalités. Ils observent en effet qu’en géopolitique, « les mentalités constituaient un premier “ pilier ”, se prolongeant naturellement avec les données propres aux identités, celles-ci débouchant sur le contexte dynamique des rivalités (p. 7) ».

Despite past attempts by the Second and Third Theories to claim the crown of modernity, Dugin believes that Liberalism has triumphed here and has managed to irrevocably present itself as the only truly “modern” way. It has also succeeded in presenting itself as the “natural order,” rather than a mere ideology.

Despite past attempts by the Second and Third Theories to claim the crown of modernity, Dugin believes that Liberalism has triumphed here and has managed to irrevocably present itself as the only truly “modern” way. It has also succeeded in presenting itself as the “natural order,” rather than a mere ideology.