Libérez l’information !

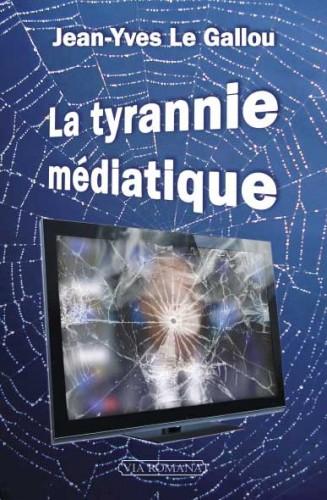

Jean-Yves Le Gallou concilie avec aisance réflexion intellectuelle et praxis politique. Ancien député français au Parlement européen, longtemps conseiller régional d’Île-de-France, énarque, haut-fonctionnaire – il est inspecteur général de l’administration au ministère de l’Intérieur -, il a fondé et dirige depuis 2002 Polémia. Ce laboratoire d’idées anti-conformistes rassemble le meilleur du G.R.E.C.E. et du Club de l’Horloge, deux associations auxquelles il participa activement.

Depuis quelques années, Polémia et son président s’intéressent à l’emprise médiatique en France. Ils ont remarqué que bien souvent les journalistes de l’Hexagone ne présentaient pas les faits de manière objective ou au moins neutre, mais les traitaient en partisans politiques. Contre cet incroyable dévoiement, Jean-Yves Le Gallou a lancé le concept de réinformation qui se concrétise, outre la mise en ligne sur le site de Polémia de contributions cinglantes, par le bulletin quotidien de la réinformation sur Radio Courtoisie.

Du courage, Jean-Yves Le Gallou n’en manque pas, car il s’attaque à ces « saints laïques » que sont les journalistes. Issus du même sérail, ceux-ci sont encensés par leurs confrères. Pour preuve, quand l’un d’eux est enlevé, son nom est cité dans chaque édition du journal télévisé. En revanche, le simple quidam ne bénéficie pas du même traitement. On lui accorde une brève évocation contrite une fois par semaine… Et encore!

Ce décryptage pertinent des tares et habitudes d’un système pervers trouve son achèvement (provisoire ?) dans La tyrannie médiatique. Les assassins de l’information. Passé expert en « médiatologie » (à ne pas confondre avec la médiologie chère à Régis Debray), Jean-Yves Le Gallou sort un manuel de référence qui fourmille d’exemples précis et d’anecdotes savoureuses. Maniant une alacrité certaine (de quoi plus normal venant de l’inventeur de la désormais célèbre cérémonie annuelle des Bobards d’Or ?), il narre son entrevue avec deux journalistes militants du Monde. S’il refuse de déjeuner avec eux, il « accepte de prendre un verre avec ces deux sulfureuses personnalités (p. 35) ». À peine arrivé dans une brasserie branchée bobo-chic, il les allume « avec ce mot de bienvenue : “ Je suis ravi de prendre un pot avec des employés de la banque Lazard ”. Abel Mestre se cabre un peu mais ne se démonte pas : “ Matthieu Pigasse [directeur général de Lazard] est au Monde à titre personnel ”. In petto, je salue la fidélité de ce vaillant chien de garde du Système, qui, même pris sur le vif, a le réflexe de ne jamais mordre la main de son maître – fût-il un laquais du Grand Capital (p. 35) ».

De cette discussion et par une observation assidue du « médiocosme », Jean-Yves Le Gallou tire un constat inquiétant qui explique le sous-titre de son essai. L’âge médiatique est une ère tyrannique qui, par l’usage incessant de la novlangue, travestit la réalité et contribue à asservir les institutions et les peuples. L’information a été chassée par la communication, le stade suprême de la propagande. Celle-ci applique les injonctions de son seigneur, l’hyper-classe mondialiste qui vomit tout ce qui comporte peu ou prou un caractère traditionnel et enraciné. Dans ses Commentaires sur la société du spectacle (1988), Guy Debord voyait la convergence fusionnelle des spectaculaires diffus et concentré dans un spectaculaire intégré. Plus prosaïque, Jean-Yves Le Gallou évoque l’amalgame réussi d’anciens adversaires avec « l’alliance des trotskystes de salle de rédaction et de la finance internationale. Sur le fond, les uns et les autres sont d’accord sur l’essentiel : il faut attaquer tout ce qui s’oppose à leur vision partagée d’un monde de plus en plus “ liquide ” – haro sur les frontières, haro sur les traditions, haro sur les cultures, et haro sur ceux qui s’opposent à l’avènement du gigantesque espace de marché libéral – libertaire qu’ils appellent de leurs vœux (p. 36) ». Cette collusion permet l’affirmation d’une puissante entité devant laquelle se plie la classe politicienne. L’auteur aurait pu se référer aux deux excellentes éditions complémentaires de Serge Halimi, Les nouveaux chiens de garde (1997 et 2005). Il y dénonçait déjà les liens incestueux entre les médiats et la politique qui se vérifient par les mariages entre hommes politiques et femmes journalistes. La réponse à cette situation déplorable doit être un refus de toute coopération avec les médiats. Il faut opposer à leurs invitations ou demandes un fin de non-recevoir comme l’ont fait le national-centriste flamand Bert De Wever en Belgique et l’Italien Beppe Grillo.

La confusion de la communication, de la politique et des affaires est possible parce que la presse écrite et les médiats sont en France la propriété de banques et de grands groupes industriels. TF1 est à Bouygues, Libération dépend de la banque Rothschild, Le Figaro appartient à Dassault, Les Échos à Bernard Arnault, Le Monde au trio Pigasse – Niel (Free) – Pierre Bergé, le milliardaire rose de la subversion. La presse quotidienne régionale est tout aussi sujette de la finance et des marchands : « le Crédit agricole contrôle toute la presse nordiste et picarde; le Crédit mutuel est aux manettes des journaux alsaciens, bourguignons et rhônalpins (p. 36) ». On peut même y ajouter La Provence, Nice Matin et Corse Matin achetés par l’honorable Bernard Tapie grâce à la générosité forcée des contribuables français… Par conséquent, du fait de cette inféodation, le journaliste « délivre une information “ orientée ”, partielle, partiale, biaisée (p. 37) ».

Jean-Yves Le Gallou insiste aussi sur le désir impératif du soutier des médiats à faire passer en priorité son point de vue. Il se sert alors de l’instant, de l’image et de l’émotion. À partir de ce triptyque, il scénarise un événement et n’hésite pas à colporter, le cas échéant, des ragots d’ordre privée guère intéressants (l’abjecte peoplisation). Mais cette quête aux ragots a des limites. Jamais la grasse presse n’a révélé au public l’existence de Mazarine, la fille cachée de Mitterrand, qui se logeait sur les deniers publics.

Le godillot folliculaire arrive à manipuler l’opinion soit par la diabolisation, soit par l’angélisation. La première concerne tous les mal-pensants de l’intérieur (Marine Le Pen, Jean-Marie Le Pen, Dieudonné, Alain Soral, les militants solidaristes et identitaires…) et les dirigeants étrangers qui résistent au nouveau désordre mondial (feu Hugo Chavez, Bachar al-Assad, Vladimir Poutine, Alexandre Loukachenko, Kim Jong-eun…). La seconde salue des minorités sociologiques qu’il faut mettre en valeur dans l’édification des masses tel un drogué qui, pour payer ses doses, agresse les vieilles dames et s’offusque qu’une salle parisienne de shoot ne soit toujours pas ouverte du fait des réticences « populistes » du voisinage. Les journalistes sont les nervis de la désinformation et de l’intoxication mentale. Ils s’imaginent en (post)modernes Joseph Rouletabille, en Zorro démasqués des injustices sociétales…

Le président de Polémia n’a d’ailleurs pas tort d’affirmer qu’on dispose des meilleurs journalistes au monde. En mars 2012, lors des tueries de Montauban et de Toulouse, le tueur porte un casque de motard intégral. Cela n’empêche pas les médiats, indéniables Hercule Poirot à la puissance mille, de le dépeindre en Européen blond aux yeux bleus qui se prénommerait même Adolf… Malheureusement pour cette belle construction médiatique, l’assassin est finalement une « chance pour la France » de retour du Pakistan et d’Afghanistan… Dès que son identité fut divulguée, les médiats s’interdirent le moindre amalgame. Il ne fallait pas « stigmatiser » des populations « fragilisées par l’histoire coloniale ».

Dans cette perspective anhistorique, les médiats usent volontiers de l’indulgence. Quand la racaille des banlieues de l’immigration attaquent les manifestations étudiantes contre le C.P.E. en 2006, agressent les lycéens et cassent les boutiques environnantes, les excuses sont vite trouvées parce que ces « jeunes » pâtissent de la misère sociale alors qu’ils sont largement assistés. En revanche, à l’occasion des « Manif pour tous » contre le mariage contre-nature, les centaines de milliers de manifestants qui ne cassent rien sont perçus comme des délinquants et des demeurés. En plus, si en leur sein se trouvent d’ignobles faf, alors on atteint là l’acmé de la manipulation !

Le travail médiatique sur les esprits ne passe pas que par le journal télévisé et les émissions politiques. Il y a l’info-divertissement (les fameux talk shows), les jeux abrutissants, la publicité et la fiction. Pour contrer la montée du Front national à la fin des années 1980, François Mitterrand demanda à Pierre Grimblat de concevoir une série populaire distillant des valeurs « belles et généreuses » de la République : L’Instit. Aujourd’hui, Plus belle la vie célèbre l’homosexualisme et le mirifique « vivre ensemble » dans un quartier imaginaire de Marseille. Il n’est pas non plus anodin que 24 ou 48 h. avant un scrutin, la télévision programme un documentaire, une émission ou un film consacrés aux années 1930 – 1940… Le 11 mai 2013, France 3, une chaîne payée par les Français via le racket légal de la redevance, proposait à 20 h 35 un téléfilm, Le choix d’Adèle : les édifiantes péripéties d’une « professeuse » des écoles face à une nouvelle élève étrangère clandestine « sans papier ». Il s’agit d’inculquer l’idée que les clandestins, délinquants de ce fait, sont chez eux dans la « patrie des droits de l’homme (non français) » !

Les médiats ne forment donc pas un fantomatique quatrième pouvoir; ils constituent le premier, car ils tiennent par l’influence les politiciens et les magistrats. Cette domination ratifiée par aucune consultation étouffe toute disputatio sérieuse nuit à la sérénité du débat intellectuel : « Le système médiatique exclut le débat et la confrontation des idées (p. 182) ». On privilégie la connivence dans le même milieu où pullulent les « faussaires », de B.H.L. – Botule à Caroline Fourest. Parallèlement, le plateau ayant remplacé la réunion publique sous le préau, les politiciens s’affichent en « médiagogues » pour complaire aux médiats. Le personnel politique conformiste veut paraître dans les émissions de radio ou de télé les plus regardés (ou écoutés). Ils sont prêts à satisfaire leurs hôtes en disant ce qu’ils veulent entendre. Ainsi, l’actuel président socialiste allemand du Parlement européen et éventuel président de la Commission européenne en 2014, Martin Schultz, déclare-t-il qu’« en démocratie, ce sont les médias qui contrôlent le pouvoir (p. 195) ». Or les médiats dépendent du fric. Mieux encore, les hommes publics acceptent que leur « image » soit géré par des agences de relations publiques qui aseptisent tout propos tranchant !

Le Système médiatique n’ignore pas sa puissance considérable. Fort de ce constat, son impudence a atteint son sommet au cours de la campagne présidentielle de 2012. Ils « se sont souciés comme d’une guigne des règles de pluralisme (p. 202) » et ont traité les candidats non convenus – les fameux « petits candidats » – avec une rare condescendance. Mécontents d’être obligés de les accueillir, passent dans la presse écrite des tribunes libres et des pétitions qui exigent la fin de la règle de l’égalité entre les candidats. Déjà, dans le passé, cette mesure avait été enfreinte : les « petits candidats » (trotskystes, chasseur, souverainistes…) passaient en plein milieu de la nuit ! Pour 2012, le « coup d’État médiatique » fut flagrant : négation des petits candidats, sous-estimation de Marine Le Pen et de François Bayrou, survalorisation de François Hollande, de Nicolas Sarközy et de Jean-Luc Mélenchon. Les journalistes rêvent d’une couverture des campagnes à l’étatsunienne où seuls les deux candidats officiels du Régime pourraient accéder aux plateaux et aux studios. Sait-on qu’aux présidentielles étatsuniennes de 2012, outre Barack Hussein Obama et Mitt Romney se présentaient le libertarien Gary Earl Johnson, l’écologiste Jill Stein, le socialiste Stewart Alexander et dix autres candidats ? Il va de soi que ces candidats ni démocrates ni républicains furent occultés par les médiats oligarchiques. Dans cette nouvelle configuration post-démocratique, l’électeur « a simplement pour rôle d’apporter une légitimité démocratique à un candidat jugé acceptable par la superclasse mondiale pour représenter ses intérêts en France (p. 25) ». Sont donc truqués le débat et le processus électoraux !

Ce dessein médiatcratique (comme naguère il exista une ambition théocratique de la part de l’Église) n’est nullement neutre puisque plus de 80 % des journalistes ont des opinions de gauche ou d’extrême gauche. Ils devraient s’indigner, se scandaliser, protester contre cette prise d’otage permanente de la population. Ils s’en félicitent plutôt car le petit peuple a tendance, en dépit du bourrage de crâne et des thérapies collectives de rééducation télévisée, à accorder son suffrage aux partis « populistes ». Le milieu médiatique hexagonal préfère contester la décision du Premier ministre national-conservateur Viktor Orban de créer un « Conseil des médiats » censeur. Or le chef du gouvernement hongrois s’inspire du précédent français avec un C.S.A. nommé par le pouvoir politique.

Opposant farouche des lois liberticides, Jean-Yves Le Gallou souhaite la suppression de cet organisme qui muselle la liberté d’expression. Dernièrement, le C.S.A. a condamné un éditorial radiophonique d’Éric Zemmour contre Christiane Taubira, la madone des délinquants, et empêche l’expansion de Radio Courtoisie en ne lui accordant pas de nouvelles fréquences en France alors qu’elle en cède d’autres aux stations commerciales décadentes… Pis, cette instance censoriale accable le président de Radio Courtoisie, Henry de Lesquen, pour avoir cité un passage sulfureux de Jules Ferry (les hiérarques censeurs expriment leur profonde ignorance historique). Est-ce si étonnant ? Non, car cet organisme n’est ni indépendant, ni représentatif. « Épée et bouclier de la pensée unique (p. 332) », le C.S.A. continue à défendre « une vision marchande, technophobe et poussiéreuse de l’audiovisuel (p. 333) » quand il ne cherche pas à imposer la « diversité ». Malgré une dotation annuelle de 40 millions d’euros, il est incapable d’endiguer le raz-de-marée d’Internet. C’est une bonne nouvelle pour l’auteur qui y voit un contre-pouvoir ou un pouvoir alternatif efficace à la condition de savoir s’en servir. Par chance, les nouveaux dissidents européens ont de belles compétences si bien qu’Internet a vu l’éclosion d’une myriade de sites, de blogues et de radios rebelles. Un projet de télévision, Notre Antenne, est même en cours en s’appuyant sur le remarquable succès du journal hebdomadaire francophone de Pro Russia T.V. – La Voie de la Russie. Fortifié par tous ces exemples, Jean-Yves Le Gallou envisage un « gramscisme technologique » pertinent et redoutable.

La tyrannie médiatique est un remarquable essai qui dénonce les privilèges inacceptables de ces indic – menteurs – désinformateurs qui coûtent aux honnêtes gens 2,1 milliards sous la forme de diverses aides versées par le Régime ? Par temps de récession économique, il y a là un formidable gisement d’économies à réaliser…

L’ouvrage de Jean-Yves Le Gallou confirme le sentiment patent de défiance du public à l’égard des médiats. Dans son édition du 4 mai 2013, Le Monde présentait un curieux sondage. Réalisé en mai 2012 en France par Opinion Way et payé par l’Open Society du néfaste milliardaire George Soros, ce sondage aborde les « théories du complot » à partir d’un panel d’environ 2500 personnes. À la question « Qui sont pour vous les groupes qui manœuvrent la France dans les coulisses ? », le pourcentage le plus élevé n’évoque pas « certains groupes religieux », « d’autres pays qui cherchent à nous dominer » ou des « groupes secrets comme les francs-maçons », mais « les grandes chaînes de télévision ou la presse écrite » : 53,9 % pour les électeurs de Marine Le Pen; 49,4 pour ceux de Nicolas Sarközy; 44,3 pour les mélenchonistes; 43,6 chez les abstentionnistes; 43,5 pour les bayrouistes; 37,4 pour les électeurs de François Hollande et 36,7 pour ceux d’Éva Joly. Serait-ce le signe précurseur d’une exaspération envers le Diktat médiatique ? Souhaitons-le!

Georges Feltin-Tracol

http://www.europemaxima.com/

• Jean-Yves Le Gallou, La tyrannie médiatique. Les ennemis de l’information, Via Romana, Versailles, 2013, 379 p., 23 €.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

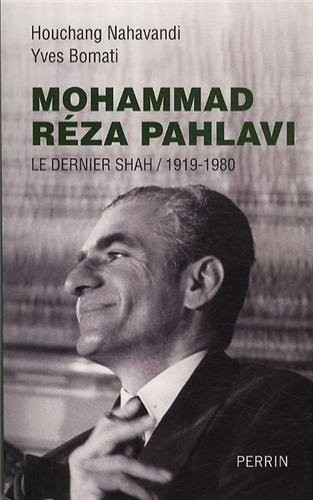

Janvier 1978-janvier 1979. C’est au moment où elle se modernisait que la monarchie des Pahlavi s’est défaite dans la confusion. De là date l’essor de l’islamisme radical.

Janvier 1978-janvier 1979. C’est au moment où elle se modernisait que la monarchie des Pahlavi s’est défaite dans la confusion. De là date l’essor de l’islamisme radical.

Né en 1956, Pierre Le Vigan a grandi en proche banlieue de Paris. Il est urbaniste et a travaillé dans le domaine du logement social. Collaborateur de nombreuses revues depuis quelque 30 ans, il a abordé des sujets très divers, de la danse à l’idéologie des droits de l'homme, en tentant toujours de s'écarter des pensées préfabriquées. Attentif tant aux mouvements sociétaux ou psychiques qu'aux idées philosophiques, il a publié, notamment dans la revue Éléments, des articles nourris de ses lectures et de ses expériences et a été un des principaux collaborateurs de Flash Infos magazine.

Né en 1956, Pierre Le Vigan a grandi en proche banlieue de Paris. Il est urbaniste et a travaillé dans le domaine du logement social. Collaborateur de nombreuses revues depuis quelque 30 ans, il a abordé des sujets très divers, de la danse à l’idéologie des droits de l'homme, en tentant toujours de s'écarter des pensées préfabriquées. Attentif tant aux mouvements sociétaux ou psychiques qu'aux idées philosophiques, il a publié, notamment dans la revue Éléments, des articles nourris de ses lectures et de ses expériences et a été un des principaux collaborateurs de Flash Infos magazine. When the ban on D.H. Lawrence’s controversial novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, was finally lifted in 1960 it was a watershed moment for censorship in Britain. But many assume it was only Lawrence’s novels that suffered at the hands of the censors.

When the ban on D.H. Lawrence’s controversial novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, was finally lifted in 1960 it was a watershed moment for censorship in Britain. But many assume it was only Lawrence’s novels that suffered at the hands of the censors.

Surfant sur la vague de l’opuscule philosophique mi-sérieux mi-drôle (ou plutôt : traitant sérieusement d’un sujet à première vue saugrenu) comme le célèbre On Bullshit de Harry G. Frankfurt ou le récent Art of Procrastination de John Perry, Aaron James nous livre avec Assholes: A Theory une analyse d’un phénomène somme toute assez peu étudié : le connard (ma traduction de l’anglais “assholes”, même si celui-ci se traduit plus littéralement par “trou-du-cul” - j’espère que ce choix apparaîtra comme justifié à la lecture de ce qui suit ).

Surfant sur la vague de l’opuscule philosophique mi-sérieux mi-drôle (ou plutôt : traitant sérieusement d’un sujet à première vue saugrenu) comme le célèbre On Bullshit de Harry G. Frankfurt ou le récent Art of Procrastination de John Perry, Aaron James nous livre avec Assholes: A Theory une analyse d’un phénomène somme toute assez peu étudié : le connard (ma traduction de l’anglais “assholes”, même si celui-ci se traduit plus littéralement par “trou-du-cul” - j’espère que ce choix apparaîtra comme justifié à la lecture de ce qui suit ).

Anarchie et Christianisme, deux gros mots pour certains, deux mots inconciliables pour d’autres. Jacques Ellul ne s’y trompe pas et l’écrit lui-même en introduction:

Anarchie et Christianisme, deux gros mots pour certains, deux mots inconciliables pour d’autres. Jacques Ellul ne s’y trompe pas et l’écrit lui-même en introduction:

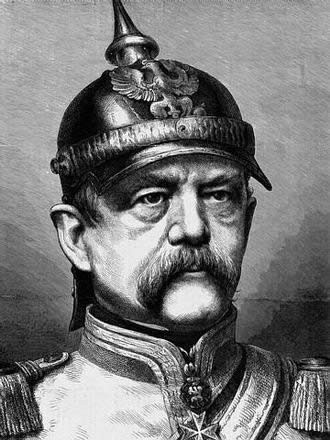

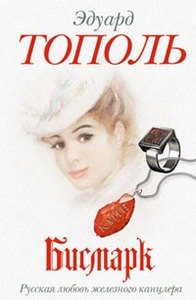

Am 6. August 1862 begegnet Otto von Bismarck in Biarritz dem russischen Fürsten Nikolai Orloff und dessen Gattin Katharina, geborene Trubezkaja. Der künftige „Eiserne Kanzler“ verknallt sich auf der Stelle in die 22-jährige Blondine. Er selbst ist bereits 47.

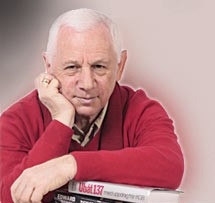

Am 6. August 1862 begegnet Otto von Bismarck in Biarritz dem russischen Fürsten Nikolai Orloff und dessen Gattin Katharina, geborene Trubezkaja. Der künftige „Eiserne Kanzler“ verknallt sich auf der Stelle in die 22-jährige Blondine. Er selbst ist bereits 47. Der heute 74-jährige Topol (Bild), der in den 70er-Jahren nach Europa und anschließend in die USA ausgewandert war, sich später aber auch in seiner postsowjetischen Heimat einen Namen machte, hat nämlich für Erotik einiges übrig. Mit seinen Büchern „Russland im Bett“, „Neues Russland im Bett“, „Die unschuldige Nastja, oder: Die ersten 100 Männer“, „Ich will dein Mädchen“ etc. sorgte er dafür, dass seine Leserschaft in jedem neuen Werk von ihm auf Prickelndes wartet. In „Bismarck“ kommt sie – wenn auch nicht mehr so ausgiebig wie früher – auf ihre Kosten. „Ich kann mich noch erinnern, wie das funktioniert“, gesteht der Autor schmunzelnd.

Der heute 74-jährige Topol (Bild), der in den 70er-Jahren nach Europa und anschließend in die USA ausgewandert war, sich später aber auch in seiner postsowjetischen Heimat einen Namen machte, hat nämlich für Erotik einiges übrig. Mit seinen Büchern „Russland im Bett“, „Neues Russland im Bett“, „Die unschuldige Nastja, oder: Die ersten 100 Männer“, „Ich will dein Mädchen“ etc. sorgte er dafür, dass seine Leserschaft in jedem neuen Werk von ihm auf Prickelndes wartet. In „Bismarck“ kommt sie – wenn auch nicht mehr so ausgiebig wie früher – auf ihre Kosten. „Ich kann mich noch erinnern, wie das funktioniert“, gesteht der Autor schmunzelnd.  Katharina stirbt aber noch viel früher als er mit 35. Als Bismarck das erfährt, verfällt er für sieben Jahre in Depression. Inzwischen hat er als Politiker ziemlich alles erreicht, die Liebe seines Lebens ist aber nicht mehr auf dieser Welt. Wozu dann das Ganze?

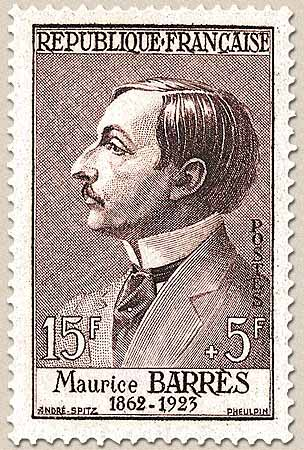

Katharina stirbt aber noch viel früher als er mit 35. Als Bismarck das erfährt, verfällt er für sieben Jahre in Depression. Inzwischen hat er als Politiker ziemlich alles erreicht, die Liebe seines Lebens ist aber nicht mehr auf dieser Welt. Wozu dann das Ganze?  Longtemps principale figure de la République des Lettres et modèle de plusieurs générations d’écrivains, Maurice Barrès est aujourd’hui bien oublié tant des institutions que du public. 2012 marquait les cent cinquante ans de sa naissance, le 20 août 1862. Cet événement n’a guère mobilisé les milieux officiels plus inspirés par les symptômes morbides d’une inculture abjecte. Le rattrapage demeure toutefois possible puisque 2013 commémorera la neuvième décennie de sa disparition brutale, le 4 décembre 1923 à 61 ans, à la suite d’une crise cardiaque. belle session de rattrapage pour redécouvrir la vie, l’œuvre et les idées de ce député-académicien.

Longtemps principale figure de la République des Lettres et modèle de plusieurs générations d’écrivains, Maurice Barrès est aujourd’hui bien oublié tant des institutions que du public. 2012 marquait les cent cinquante ans de sa naissance, le 20 août 1862. Cet événement n’a guère mobilisé les milieux officiels plus inspirés par les symptômes morbides d’une inculture abjecte. Le rattrapage demeure toutefois possible puisque 2013 commémorera la neuvième décennie de sa disparition brutale, le 4 décembre 1923 à 61 ans, à la suite d’une crise cardiaque. belle session de rattrapage pour redécouvrir la vie, l’œuvre et les idées de ce député-académicien. Par delà ce talent polémique, Jean-Pierre Colin perçoit dans l’œuvre de Barrès politique la préfiguration des idées gaullistes de la V

Par delà ce talent polémique, Jean-Pierre Colin perçoit dans l’œuvre de Barrès politique la préfiguration des idées gaullistes de la V Het jaar van het gevaarlijke dromen bestaat grofweg uit twee delen. Eerst maakt Zizek een aantal opmerkingen over de dynamiek van het kapitalisme, waardoor deze ideologie er steeds weer in slaagt zich aan de veranderende omstandigheden aan te passen zonder evenwel haar principes van uitbuiting en onrechtvaardigheid op te geven.

Het jaar van het gevaarlijke dromen bestaat grofweg uit twee delen. Eerst maakt Zizek een aantal opmerkingen over de dynamiek van het kapitalisme, waardoor deze ideologie er steeds weer in slaagt zich aan de veranderende omstandigheden aan te passen zonder evenwel haar principes van uitbuiting en onrechtvaardigheid op te geven. Canale Mussolini ist ein Epochen- und Familienroman, der – autobiographisch angereichert – davon erzählt, wie aus den Männern und Frauen einer norditalienischen, mittellosen Bauernsippe handfeste Faschisten werden: un-ideologische zwar, aber ist das nicht immer so, wenn es um die Masse unterhalb der weltanschaulich gefestigten Revolutionäre geht?

Canale Mussolini ist ein Epochen- und Familienroman, der – autobiographisch angereichert – davon erzählt, wie aus den Männern und Frauen einer norditalienischen, mittellosen Bauernsippe handfeste Faschisten werden: un-ideologische zwar, aber ist das nicht immer so, wenn es um die Masse unterhalb der weltanschaulich gefestigten Revolutionäre geht?

![[Lecture] Contre l’Europe de Bruxelles – Fonder un Etat européen, par Gérard Dussouy](http://fr.novopress.info/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/dussouy_modifie-1.jpg)