To understand why Europeans were the progenitors of the highest accomplishments in history – close to one hundred percent of the great ideas in philosophy, science, anthropology, sociology, economics, geography, geology, astronomy, mathematics, architecture, technology, dance, and music – you must understand the Presocratic self-conscious separation of the knowing “I” from the “not-I.” The Presocratics were the first humans to discover that they have a mind that is the seat of thinking and thus of knowledge, the only agency in the whole realm of nature able to separate itself from everything that is not its own, as well as making itself “a possible object of thought to itself,” as Aristotle would put it in a clear-cut manner later on [On the Soul, Bk. III: Ch. 4, 429b]. The Presocratics were the first men to detach their ego consciousness from the surrounding natural world, establishing their thinking “I” as the cognitive center, the decision-maker as to what makes truthful statements possible, in contradistinction to traditions handed down without reflection, the voices of gods and demons.

To understand why Europeans were the progenitors of the highest accomplishments in history – close to one hundred percent of the great ideas in philosophy, science, anthropology, sociology, economics, geography, geology, astronomy, mathematics, architecture, technology, dance, and music – you must understand the Presocratic self-conscious separation of the knowing “I” from the “not-I.” The Presocratics were the first humans to discover that they have a mind that is the seat of thinking and thus of knowledge, the only agency in the whole realm of nature able to separate itself from everything that is not its own, as well as making itself “a possible object of thought to itself,” as Aristotle would put it in a clear-cut manner later on [On the Soul, Bk. III: Ch. 4, 429b]. The Presocratics were the first men to detach their ego consciousness from the surrounding natural world, establishing their thinking “I” as the cognitive center, the decision-maker as to what makes truthful statements possible, in contradistinction to traditions handed down without reflection, the voices of gods and demons.

It is barely possible today to say that the Greek achievement was unique and even less possible to speak of a “Greek miracle.” The situation is so bad in our pathological universities that some academics are now insisting that to teach about the foundational role of the Greeks in the making of Western civilization is “a slippery slope to white supremacy.” This is the culmination of many decades of “novel” interpretations by classicists themselves, starting with the claim that the Greeks were not original but ungrateful imitators of their “African and Asian neighbors.” Postmodernists have long been trying to persuade white students that Greek-European rationality is itself mythological or, conversely, that there are other rationalities – Bantu, Aztec, and Hindu – no less valuable than Western rationality.

A major flaw in attempts to downgrade the ancient Greeks is that no matter how many links may have been established between the ancient Greeks (and Western peoples generally) with other cultures, it is always the Europeans who do the achieving, who brought forth the invention of universities, the twelfth-century Renaissance, the Papal Revolution, the invention of mechanical clocks, the discovery and mapping of the world, “an extraordinary burst of innovations in microscopy, human anatomy, optics, electrical studies, and the science of mechanics during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,” the Enlightenment, and the Industrial Revolution. Another flaw is that it is hard to hide the far superior achievements of the ancient Greeks in multiple fields of knowledge and the arts compared to the meager achievements of other Axial Age civilizations in religion and conventional ethics.

In response to the now-institutionalized downgrading of the Greeks, I decided to study recent defenses of the traditional view of the Greeks as an exceptional people. I also decided to read Havelock’s Preface to Plato, a now classic book which can be fruitfully understood as a study of the birth of self-consciousness, rather than as a mere study of the rise of a literate, alphabetic culture over an oral culture, or a defense of Plato’s attack on the poetic tradition.

André Laks, The Concept of Presocratic Philosophy: Its Origin, Development, and Significance (2006 in French, 2018 in English).

Maria Michela Sassi, The Beginnings of Philosophy in Greece (2009 in Italian, 2018 in English).

Christopher Lyle Johnstone, Listening to Logos: Speech and the Coming of Wisdom in Ancient Greece (2009).

Constantine J. Vamvacas, The Founders of Western Thought: The Presocratics (2001 in Greek, 2009 in English).

Eric A. Havelock, Preface to Plato (1963).

[2]The Concept of Presocratic Philosophy

I will write a brief exegesis of each book in the order in which I read them. Laks’s book is a historiographical survey of “the various senses in which Presocratic philosophers [were] considered Presocratic” from ancient to contemporary times (35). For a long time, beginning with Aristotle and Diogenes Laertius (third century AD, author of a biography of Greek philosophers, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers [3]), the Presocratics were viewed as “natural philosophers” who conducted inquiries into nature – the “principle” or “substrate” in Aristotle’s words – “of which all beings are made,” the way in which the universe and the Earth were formed, including the study of specialized topics such as the distance and size of the heavenly bodies, the luminosity of the Moon, the causes of earthquakes, and the origins of living things. They were seen as the “first ones to philosophize” about the nature of things. Hegel continued this “Aristotelian” interpretation of the Presocratics, but Nietzsche criticized this idea and focused instead on the “tragic” element in early Greek culture and the power of myths, while Heidegger reinterpreted Presocratic writings not as inquiries into the nature of things but as inquiries into man’s relationship-of-Being towards the “world.” Then came Horkheimer and Adorno, members of the Frankfurt School, blaming the Presocratics for starting the Western presumption that its own particular form of thinking was disinterested and purely concerned with the pursuit of truth. It was, rather, a will to dominate nature, not superior to mythological accounts but a myth itself, a totalitarian myth seeking to displace other forms of thinking. Anthropologists welcomed this critique, “by showing either that rationality is at work in myth itself or that there are other rationalities besides Western rationality” (37).

Laks brings up studies about the “Orientalizing” aspects of Greek culture, borrowings from the Near East, briefly mentioning Jaspers’ thesis about similar breakthroughs elsewhere in the world from mythology to rationality during the Axial Age period between 800 and 200 BC. He also pays particular attention to J. P. Vernant’s central book, The Origins of Greek Thought (1962), and its claim that there was no “Greek miracle” in the sense that Greek reason did not arise suddenly out of some innate Greek genius but was a product of the democratizing political atmosphere within the city-states, which encouraged debate and a form of rationality that was then extended to the study of nature.

Laks brings up studies about the “Orientalizing” aspects of Greek culture, borrowings from the Near East, briefly mentioning Jaspers’ thesis about similar breakthroughs elsewhere in the world from mythology to rationality during the Axial Age period between 800 and 200 BC. He also pays particular attention to J. P. Vernant’s central book, The Origins of Greek Thought (1962), and its claim that there was no “Greek miracle” in the sense that Greek reason did not arise suddenly out of some innate Greek genius but was a product of the democratizing political atmosphere within the city-states, which encouraged debate and a form of rationality that was then extended to the study of nature.

Laks wants to defend the older Aristotelian interpretation, but in a way that acknowledges more recent interpretations, making his more than 100-page book a rather weak (never elaborated) defense of the “new rationality” of the Presocratics. He spends a chapter valuing Ernest Cassirer’s early twentieth-entury writings on the Greeks, closing the book with a nice “Hegelian” passage from Cassirer that “Greek philosophy can be characterized to a certain extent as the first manifestation of the act of thinking itself: as a thought that in the midst of its pure movement gives to itself its content and its firm configuration.” This great passage, however, is left hanging without explanation. Laks does not explain what it means for thought to give itself its own content, but instead offers a rather unclear and contorted summation of the relationship between Cassirer’s philosophy of symbolic forms and Greek thought.

The Beginnings of Philosophy in Greece

Maria Sassi’s book is a more decisive defense of the Aristotelian interpretation. The Presocratics were responsible for the birth of philosophy, the cultivation of a “rationalistic” approach to the study of nature, and “the elaboration of a critical stance toward received opinions” (xiv). She gives serious attention to the “revisionists” and acknowledges early influences from the Near East and the continued presence of magic, mythological motifs and soteriological aspirations among the Greeks, while explaining, nevertheless, how Presocratic thought “represents a truly new contribution to the understanding of the nature of things . . . an epochal break from the structure of the mythological cosmogonies” (xv-xvi).

Rather than emphasizing the link between Greek philosophy and the rise of the city-states, Sassi pays attention to the role of prose writing during the second half of the fifth century in expressing and solidifying “rational argumentation.” She objects to the way an “anticlassicistic trend has become mandatory” in academia; the way academics today are “obsessed with the need to push as far back as possible the infancy of philosophy, to the point of causing philosophy to ‘disappear’ into myth” (14-15). She mentions the “indebtedness” of archaic Greece to the Semitic East, “from technology to medicine to mythology,” but insists that after the Homeric Age “logos gains more and more importance as the designation of speech that does not depend on tradition but only needs to be evaluated with respect to its internal organization . . . in the context of argumentative strategies” (19).

[4]She believes that Aristotle was correct in identifying the Presocratics as the first philosophers of nature in their search for the “principle” of things and something ultimate beneath the sensory variations we observe in nature without appealing to any divine force. Already in Hesiod (700 BC), we have the first author in history “to talk about himself in the first person” rather than anonymously, as was the case in the Near East. This is an important observation Sassi makes, though, without explaining why writing in the first person was such a significant attribute of Greek originality. We will see below that speaking in the first person, using your name to signal that you are the author (authority) of your ideas, was part of the expression of the Presocratic liberation of the self from external controls and obfuscations. They were the first humans to discover the self and to separate the knower from the immemorial grip of traditional myths. Hesiod is just the beginning; he was still inhabiting a world of myths, but, as Sassi tells us, he was the first to compose a systematic genealogy of the gods, “an organizational system for the gods’ respective spheres of influence . . . exhibiting unprecedented, encyclopedic ambition, with the aim of presenting his own arrangement as the right one” (32-33, her italics). Hesiod wants to know, in his words, “how in the beginning the gods, the earth and the rivers were born, and the boundless sea seething with its swell, and the bright stars and the broad sky above.” Sassi shows that there is “a logic in this [Hesiod’s] cosmogony. Rather than the product of a mytho-poetic process, it appears to be the result of a series of systematic choices stemming from an original reflection” (36).

Beginning with Thales’ use of a common noun, water, rather than a mythic name, as the ultimate source of all things, Anaximander (610-546 BC), writing some forty years after his teacher Thales, would try to locate in a precise sequence the increasing distance from the Earth of the Moon, Sun, and stars. Anaximander wrote about heavenly bodies as impersonal forces without any anthropomorphic traits, using a language “keen on processes of abstraction and conceptualization” (41). Even in political thinking, one finds in the works of Solon an emphasis on human responsibility for their own misfortune and a denial of intentionality on the part of gods. Around 500 BC we have Heraclitus describing the universe as a kosmos, an orderly arrangement characterized by regularity without divine influences. She notes the “pointedly polemical character” of Heraclitus’ writing and, indeed, how each Presocratic thinker, from Heraclitus on, proposed a new theory in self-conscious refutation of preceding theories, engaging in “second-order questions” as to why their theoretical approaches were superior to previous assessments. Sassi says that this “self-conscious knowledge” bespeaks of thinkers who were increasingly aware that knowledge flows out of their own knowing minds in competition with other rationalizing minds. She cites Heraclitus’ proclamation, “I went in search of myself,” in order “to stress that he extrapolated the contents of logos from an isolated and highly personal reflection” (73). She notes as well how Heraclitus developed a conception of the psyche as the source of cognition away from the Homeric notion of the psyche as vital breath. Knowledge is the product of the activity of the psyche.

Beginning with Thales’ use of a common noun, water, rather than a mythic name, as the ultimate source of all things, Anaximander (610-546 BC), writing some forty years after his teacher Thales, would try to locate in a precise sequence the increasing distance from the Earth of the Moon, Sun, and stars. Anaximander wrote about heavenly bodies as impersonal forces without any anthropomorphic traits, using a language “keen on processes of abstraction and conceptualization” (41). Even in political thinking, one finds in the works of Solon an emphasis on human responsibility for their own misfortune and a denial of intentionality on the part of gods. Around 500 BC we have Heraclitus describing the universe as a kosmos, an orderly arrangement characterized by regularity without divine influences. She notes the “pointedly polemical character” of Heraclitus’ writing and, indeed, how each Presocratic thinker, from Heraclitus on, proposed a new theory in self-conscious refutation of preceding theories, engaging in “second-order questions” as to why their theoretical approaches were superior to previous assessments. Sassi says that this “self-conscious knowledge” bespeaks of thinkers who were increasingly aware that knowledge flows out of their own knowing minds in competition with other rationalizing minds. She cites Heraclitus’ proclamation, “I went in search of myself,” in order “to stress that he extrapolated the contents of logos from an isolated and highly personal reflection” (73). She notes as well how Heraclitus developed a conception of the psyche as the source of cognition away from the Homeric notion of the psyche as vital breath. Knowledge is the product of the activity of the psyche.

Sassi could have said more about how Heraclitus connected his conception that there is a rational order in the world, a logos, with the idea that the logos is present within the inner self in the degree to which the psyche is self-conscious of being the source of knowledge (115). The logos can only be revealed to humans who know that their minds are the agency through which the rationality of the world can be revealed. In order to achieve knowledge, the individual must be self-conscious of his psyche as the repository of knowledge, as the only vehicle through which the logos of the world can be understood. By looking “within themselves,” inside their thinking minds, humans can reveal the logos that is outside them.

Sassi contrasts as well the “conservation” role of writing in the Near East, which remained religious and was “composed anonymously within a circle of priests and then copied for centuries without any conceptual changes” (75), to the writing of the Greeks, which was open to everyone. She estimates that about thirty percent of male citizens in the polis were able to read and write. The Greeks adopted prose writing in the last decades of the fifth century, she says, in their “search for directness and unambiguousness” and their preference for truths freed from the “restraints of prosody,” and in contradistinction to the texts of Mesopotamia with their “revelations of a preestablished traditional” worldview immune “from authorial interventions” (142). Herodotus’ Histories was the “first extended prose narrative of Greek literature,” followed by Zeno, Melissus, the Pythagoreans, Anaxagoras, Leucippus, and Democritus. This was a prose “rich in elaborate syntactical structures in unison with a linguistic inquiry that prefers precision over metaphors and evocative expressions” (171).

Sassi contrasts as well the “conservation” role of writing in the Near East, which remained religious and was “composed anonymously within a circle of priests and then copied for centuries without any conceptual changes” (75), to the writing of the Greeks, which was open to everyone. She estimates that about thirty percent of male citizens in the polis were able to read and write. The Greeks adopted prose writing in the last decades of the fifth century, she says, in their “search for directness and unambiguousness” and their preference for truths freed from the “restraints of prosody,” and in contradistinction to the texts of Mesopotamia with their “revelations of a preestablished traditional” worldview immune “from authorial interventions” (142). Herodotus’ Histories was the “first extended prose narrative of Greek literature,” followed by Zeno, Melissus, the Pythagoreans, Anaxagoras, Leucippus, and Democritus. This was a prose “rich in elaborate syntactical structures in unison with a linguistic inquiry that prefers precision over metaphors and evocative expressions” (171).

The Greeks knew they had a mind intended for thought. This found expression in their determination to stand out as singular authors capable of relying on their own minds, as testified in their increasing use of “I” when formulating a new argument. Herodotus used the first person 1,087 times, to show his authorial presence in his understanding of the Persian wars, “accompanied by a growing focus on methodological questions, such as the role of empirical observation and the evaluation of symptoms/testimonies as proof of an argument” (173). What they claim to know are the reflections of their own minds.

Sassi knows there is a relationship between the redefinition of the psyche as the source of reasoning and the pursuit of truth, the emphasis on authorial responsibility, the emergence of prose writing, and the description of the nature of things through the use of increasingly abstract concepts. But she never says in a clear-cut manner that the essential achievement of the Presocratics, which made possible their magnificent creativity in multiple fields, and which laid the grounds for Socrates and after, was their discovery that knowledge ultimately comes from the faculty of the mind, the ability of the thinking self to turn in upon itself as the one self-conscious agent in the universe that is capable not only of knowing but of knowing that it is the agent that can decide what it means to know.

Listening to the Logos

Only one-third of Christopher Johnstone’s book is about the Presocratics, and he does not engage with postmodernists or multicultural revisionists. Nevertheless, he offers a tighter account of the relationship between the invention of alphabetic writing, the appearance of prose composition, the discovery of the mind, the rise of a consciousness “rooted in a distinction between the knower and the known,” and the idea that the psyche of man, “in its deepest nature,” is logos. He also brings out in a slightly acuter way the seminal ideas of Eric Havelock. In the end, however, Johnstone’s conclusion about the exact contribution of the Presocratics is similar to Sassi’s. The Presocratics, he writes, offered a new understanding of the world “from a purely mythopoetic view to include a naturalistic/philosophical orientation” (2). This conclusion is flawed in giving the impression that the Presocratics merely originated a rational and critical approach to the study of nature that would culminate in modern science. But Johnstone does have a keener sense, though he never says it directly, about the Presocratic discovery of the faculty of the mind as the only authorial agency that can be trusted in the pursuit of truth.

[5]He explains well that mythical accounts as such are not irrational insofar as they are efforts to make sense of the world, to give meaning and order “to the variety and variability in what happens around us and of apprehending the causes behind events”. A myth is a story, “a narrative that enables a people – a tribe, a clan, a culture – to make sense of the mysterious,” how things came into being, where did we come from, and who are our original ancestors. Myths allow individuals and groups to “fit into” the order of things, to find a moral ground for action, and a means to pass from one generation to another the most fundamental truths of a people. Using Jean Piaget’s language [6], we can say that myths are accounts by a people who don’t have the cognitive capacity to engage in formal operational thinking, though they do have a capacity to engage in concrete operational thinking in their daily survival strategies. If we identify rationality with formal thinking and the ability to offer explanations of natural events without appealing to, or appeasing, gods and demons, then the Presocratics were the first to rely on rational concepts.

But this Piagetian emphasis on formal rationality does not hit the spot. Mythological people are unable to understand the real causes behind events precisely because they lack consciousness of their consciousness and have no concept of an “I” in separation from the world around them. They are overwhelmed by multifarious forces within and without, feelings and instincts, noises and natural events, storms and hurricanes, the darkness of the forests, the vastness of the sea and the sky, all intermingled with their dreams, fears, emotions, and appetites. Johnstone brings Julian Jaynes’ view about the inability of the Homeric Greeks to identify the logos within them, their own minds as the locus of the “I” in distinction from what lies outside the self. The characters of the Iliad, he cites Jaynes, “do not sit down and think out what to do. They have no conscious minds such as we say we have, and certainly no introspections . . . The beginnings of action are not in conscious plans, reasons, and motives; they are in the actions and speeches of gods.” He also cites Bruno Snell’s estimation that “in Homer every new turn of events is engineered by the gods . . . For human initiative has no source of its own” (20).

I have written about [7] the immense value of Jaynes and Snell in identifying the emergence of “consciousness of consciousness” after Homer as a pivotal factor in ancient Greek culture. I will not rehearse the limitations in Jaynes and Snell except to say that their denial of introspection in the Iliad went too far. I see the Iliad as a transitional work exhibiting signs of free deliberation. Jaynes also confounded matters in attributing the emergence of self-consciousness to external historical factors, such as the weakening and collapse of theocratic empires, the intermingling of peoples from different nations with different beliefs, which supposedly weakened the “auditory power” of gods and the rigid norms occupying the brains of peoples. His explanation that the development of a language sophisticated enough to produce metaphors of “me” and of “analog I” made matters even more confounding since the Iliad is packed with some of the best metaphors in Western literature. Snell, for his part, never offered an explanation as to how the “inner self” suddenly emerged in Greek lyrical poetry after 650 BC.

Johnstone deserves credit for bringing up some key passages from Jaynes and Snell. Most Classicists today don’t even know Jaynes, and the few who have read Snell are under the delusional belief that their hyper-specialized research about trivial subjects stands above his “dated” ideas. In a strong way, Johnstone incorporates Havelock’s ideas. In my estimation Havelock’s book, Preface to Plato, published in 1963, is similarly important in identifying the emergence of self-conscious personalities as the central breakthrough of the Greeks. Unfortunately, Havelock misdirected attention from this insight by attributing the origins of Greek self-consciousness to the rise of a new “technology of communication,” or the “invention of alphabetic writing” per se. Every time Havelock’s name comes up, it is about his “theory” that alphabetic writing engendered a different attitude of mind, or, in the words of Johnstone, about how the transition from an oral to a literate culture “induce[d] a form of consciousness rooted in a distinction between the knower and the known” (39). As I see it, alphabetic writing, the fact that Greek prose came to be “characterized by unparalleled lucidity,” to cite Vamvacas, “precision, suppleness, and aesthetic dexterity” (7), was itself a manifestation of the self-awareness and self-knowledge developed by the Greeks in tandem with their uniquely aristocratic lifestyle and ethos of personal heroism.

Johnstone’s account is thus limited in its focus on alphabetic writing as such, which leads him to ponder about other “conditions . . . that incubated the seeds of Western scientific and philosophical thought.” He brings up the city of Miletos, from which the first Presocratics came, as a location at the “crossroads for east and west.” He says that exposure in this city “to a wide variety of mythic traditions and to alternative ways of understanding” somehow produced, in the words of an academic he cites, “a breakthrough in man’s thinking, a shift toward rationalism” (38). Academics love this stuff about diverse cities creating cultural “enrichment.” They never care to ask why the far older cosmopolitan cities of the Near East failed to produce any rationalism and why whites are always the ones responsible for new ideas.

Johnstone’s account is thus limited in its focus on alphabetic writing as such, which leads him to ponder about other “conditions . . . that incubated the seeds of Western scientific and philosophical thought.” He brings up the city of Miletos, from which the first Presocratics came, as a location at the “crossroads for east and west.” He says that exposure in this city “to a wide variety of mythic traditions and to alternative ways of understanding” somehow produced, in the words of an academic he cites, “a breakthrough in man’s thinking, a shift toward rationalism” (38). Academics love this stuff about diverse cities creating cultural “enrichment.” They never care to ask why the far older cosmopolitan cities of the Near East failed to produce any rationalism and why whites are always the ones responsible for new ideas.

For all this, Johnstone appreciates how original the Greeks were; how they subjected all accounts, including mythic tales, to critical questioning; how their speech was no longer characterized by ritualistic formulas, but was based on open debate; and how they developed a language capable of the abstraction that is necessary for analytical and rational accounts. He thus tells us how Anaximander was the “first Greek to produce a written account of the workings of nature” (47), a language which still contained mythopoetic images, but which also bespoke of impersonal forces governing the universe. Subsequently, Presocratics would produce “more abstract conceptualizations.” Heraclitus would find a logos, unity and harmony, beneath the apparent multiplicity evinced by the senses, coupled with the realization that fire, not water and not earth, was responsible for the changes we observe, the unstable and dynamic side of natural processes, which are likewise “ordered” by the “measures” of a logos. It is the rational mind within humans, the logos inside them, expressed through speech, which grasps the logos of the cosmos. Parmenides rationalized reality even more in claiming that Being itself is what is logically possible and that the logos of the soul is the instrument by which we can grasp the truth of Being.

While Johnstone sometimes misdirects by concentrating too much on the transition from a mythical to a rational account of nature, he is well aware of the “psychological side” in the Presocratic revolution, the way the Greek thinker “was rid of interference from the gods in his/her inner life and was therefore free to develop a sense of self-directedness . . . The move toward subjectivity and agency is an important departure from the Homeric mind, marking the origin of the Western concept of self-hood as autonomous and morally responsible” (80).

The Founders of Western Thought: The Presocratics

Published as Volume 257 of the Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, Constantine Vamvacas’ book has a textbook-like quality, with a chapter dedicated to each of the major Presocratics. The first three general chapters and the “Epilogue” will do for our purposes. There is one passage in which Vamvacas brings up directly the realization of self-consciousness by the Greeks: “[T]he Greek of the Homeric period did not feel independent, and thus did not consider himself responsible for his actions and feelings. He attributed everything to the gods, and he even lacked the realization that he himself could be the cause of his decisions and feelings” (9). But this passage stands alone. He does not reference Jaynes and Havelock. He cites Snell a few times, but not in regards to his central argument about the Greek “discovery of the mind.” The main figure in Vamvacas’ study is Karl Popper, who argued that the Presocratics “created the rational or scientific attitude, and with it our Western civilization, the only civilization, which is based upon science.” Those who think that the rise of Galilean-Newtonian science is the defining attribute separating the West from the Rest will be drawn to Popper’s interpretation. My view is that the continuous creativity of Europeans in all the spheres of life since ancient times has been a result of their growing realization that inside them there is a mind (soul or psyche) capable of being the seat of autonomous reflection. I will address this point again in the last section, on Havelock.

[8]Vamvacas finds Jaspers’ argument that there were breakthroughs in civilizations outside Greece limited in its inability to appreciate the Greek scientific spirit. The Chinese were concerned with practical-ethical questions about “proper human relations” and the Axial writings of India remained within the ambit of religious longings about the meaning of life. Only the Greeks sought to understand the “ultimate reality hidden beneath the phenomenal world of sense-experience” (249). It was the Greeks who provided the principles and concepts that would make possible modern science: the idea that there are universal laws of nature, that there is an underlying reality beneath sensory experience explainable through the proper use of deductive and inductive methods, that there is a mathematical order in the natural world, that all things are ultimately made of atomic particles, and that there is symmetry and proportion in the natural world.

Vamvacas makes the very important point that “Presocratic philosophy is not the culmination of a sudden awakening of the Greek spirit. It is the culminating result of a long development and maturation of the Greek mind” (19). He says little, however, about this long development, apart from noticing that Hesiod’s Theogony goes beyond standard mythological accounts in placing the gods “in a consistent, complete, ordered system,” and posing questions about the beginning of the world, and communicating an interest in “truths.” Vamvacas refers briefly to the “awakening of the personality of the Greek” in early lyric poetry, the fact that such poets as Archilochus, Simonides, and Sappho (writing in the seventh century after Homer, and before the Presocratics) expressed their own “personal values.” But not much else is said. Snell still remains the go-to source for the argument that Greek lyric poets were the first ones to separate the individual self from prescribed expressions and norms. Vamvacas is nevertheless an excellent source for a comprehensive argument about the scientific orientation of the Presocratics. I like the statement that during the Presocratics era “for the first time the human mind focuses on the truth” (20). He does not explain the connection between the discovery of the mind and the pursuit of truth, but it is implicit in his overall argument that there can be no truth-seeking without an inner awareness of the faculty of reason, the only faculty that can legislate for itself principles, concepts, and theories, because, if I may use the words of Aristotle, it is the only faculty that is “able to think itself” [On the Soul, Bk. III: Ch. 4, 429b].

Vamvacas makes the very important point that “Presocratic philosophy is not the culmination of a sudden awakening of the Greek spirit. It is the culminating result of a long development and maturation of the Greek mind” (19). He says little, however, about this long development, apart from noticing that Hesiod’s Theogony goes beyond standard mythological accounts in placing the gods “in a consistent, complete, ordered system,” and posing questions about the beginning of the world, and communicating an interest in “truths.” Vamvacas refers briefly to the “awakening of the personality of the Greek” in early lyric poetry, the fact that such poets as Archilochus, Simonides, and Sappho (writing in the seventh century after Homer, and before the Presocratics) expressed their own “personal values.” But not much else is said. Snell still remains the go-to source for the argument that Greek lyric poets were the first ones to separate the individual self from prescribed expressions and norms. Vamvacas is nevertheless an excellent source for a comprehensive argument about the scientific orientation of the Presocratics. I like the statement that during the Presocratics era “for the first time the human mind focuses on the truth” (20). He does not explain the connection between the discovery of the mind and the pursuit of truth, but it is implicit in his overall argument that there can be no truth-seeking without an inner awareness of the faculty of reason, the only faculty that can legislate for itself principles, concepts, and theories, because, if I may use the words of Aristotle, it is the only faculty that is “able to think itself” [On the Soul, Bk. III: Ch. 4, 429b].

Eric Havelock’s Preface to Plato

This book, published in 1963, is part of the older school of thought about Greek uniqueness. It is a book I have known for some time as a defense of Plato’s attack on the oral Homeric tradition and as a study of the rise of a literate culture in Greece. Suspecting there was more to it, I recently decided to read it, learning that it inhabits indeed a similar interpretative world as the books by Jaynes and Snell in its emphasis on self-consciousness. This is not how Havelock frames his own study, and this is why the full implications of his book have not been fully absorbed. But the standard interpretation is not inconsistent with the view that Havelock was not solely concerned with the emergence of alphabetic writing and Platonic rationalism, but with arguing that the realized condition of self-consciousness and inner freedom required an abstract and theoretical language with a different syntax away from the oral Homeric tradition with its formulaic rhythms, visual imagery, and memorialized thoughts.

However, I don’t want to force my own interpretation onto Havelock, and so we can say that the thesis of his book is that the invention of the Greek alphabet, in contrast to all previous systems of communication, including the Phoenician, brought about a revolution from a Homeric state of being in which Greeks could not differentiate a man’s breath or his life blood from his mind, and were thus devoid of self-consciousness, to a Platonic state of mind in which they came to develop a conception of their personalities as autonomous agents no longer absorbed within an oral tradition and a poetic language incapable of abstract thinking. What I find most persuasive in this thesis is its emphasis on the Greek discovery of the psyche as the seat of self-consciousness involving the separation of the knower from the known.

[9]But I find it hard to accept the claim that the introduction of alphabetic writing was the one factor that brought about this revolution. Havelock writes about how “the alphabet proved so much more effective and powerful an instrument for the preservation of fluent communication than any syllabary had been” (137). Oral cultures are preoccupied with “formulaic directives” and the transmission of immemorial norms through incantation and repetition. In oral poetry the utterance is immediate, mnemonic, surviving only in memory and recitation, accepted without inviting inquiring minds to think for themselves. The alphabet, by contrast, encourages a form of consciousness in which pronouns are used, “both personal and reflexive . . . in new syntactical contexts . . . as objects of verbs of cognition, or placed in antithesis to the ‘body’ . . . in which the ‘ego’ was thought as residing” (198). The “I” as the authorial agent of his own ideas becomes the norm, together with prose writing without any metrical (or rhyming) structure but aiming at analytical precision and open argumentation. Havelock also points out that the written word exists independently of the subject, outside the reader, and can be studied, underlined, and analyzed – not merely memorized and recited as sacred oral tales, but as accounts which can be subjected to endless questioning.

But while alphabetic writing eventually became an indispensable means of communicating truths (during the fourth century BC), beyond poetic recitations about the norms to be valued in a community, I would argue, as Havelock admits in passing, that “there are clear signs in Homer himself that the Greek mind would one day reach out in search of a different kind of experience” beyond poetic recitation. I will not repeat my view that Homer was a transitional figure. It may suffice to point out Havelock’s own recognition that alphabetic writing barely existed before Euripides, by which time the Presocratics had already achieved so much. Havelock knows this: “the Presocratics themselves were essentially oral thinkers . . . but they were trying to device a vocabulary and syntax for a new future, when thought should be expressed in categories organized in a syntax suitable to abstract statement” (x).

But while alphabetic writing eventually became an indispensable means of communicating truths (during the fourth century BC), beyond poetic recitations about the norms to be valued in a community, I would argue, as Havelock admits in passing, that “there are clear signs in Homer himself that the Greek mind would one day reach out in search of a different kind of experience” beyond poetic recitation. I will not repeat my view that Homer was a transitional figure. It may suffice to point out Havelock’s own recognition that alphabetic writing barely existed before Euripides, by which time the Presocratics had already achieved so much. Havelock knows this: “the Presocratics themselves were essentially oral thinkers . . . but they were trying to device a vocabulary and syntax for a new future, when thought should be expressed in categories organized in a syntax suitable to abstract statement” (x).

I would argue that the gradual emergence of personalities capable of introspection, already evident in the Iliad, and in the poetic heroic literature of Indo-Europeans generally, and certainly in the (emerging abstract) thoughts of the Presocratics, is what precipitated the widespread use of alphabetic writing. I disagree with the cause-effect relationship Havelock identifies in this key passage:

One is entitled to ask . . . given the immemorial grip of the oral method of preserving group tradition, how a self-consciousness could ever have been created . . .The fundamental answer must lie in the changing technology of communication (208).

This tendency to identify alphabetic writing as an independent variable has led Havelock’s interpreters to view Preface to Plato as an argument about the importance of alphabetic writing. No one has paid much attention to Havelock’s qualifications: “In fact it is probably more accurate to say that while the discovery [of the psyche as the seat of self-consciousness] was affirmed and exploited by Socrates, it was the slow creation of many minds among his predecessors and contemporaries. One thinks particularly of Heraclitus and Democritus” (197-8).

Once we look past the idea of alphabetic writing as an independent variable that somehow came onto the scene as a “new technology of communication” pushing the Greeks into philosophical reflection, we may be able to appreciate how insightful Preface to Plato remains. There is more to this book than what I outlined above. I will close this article with a few more passages from this book which bring out Havelock’s realization that Greek uniqueness was about the coming to self-consciousness by humans for the first time in history.

Homeric man . . . was part of all he had seen and heard and remembered. His job was not to form individual and unique convictions but to retain tenaciously a precious hoard of exemplars. These were constantly present with him in his acoustic reflexes and also visually imagined before his mind’s eye. His mental condition, though not his character, was one of passivity, of surrender, and a surrender accomplished through the lavish employment of the emotions and of the motor reflexes (199).

The speech of men who have remained in the Greek sense ‘musical’ and have surrendered themselves to the spell of the tradition, cannot frame words to express the conviction that ‘I’ am one thing and the tradition is another; that ‘I’ can stand apart from the tradition and examine it; that ‘I’ can and should break the spell of its hypnotic force; and that ‘I’ should divert some at least of my mental powers away from memorisation and direct them instead into channels of critical inquiry and analysis (199-200).

This amounts to accepting the premise that there is a ‘me’, a ‘self’, a ‘soul’, a consciousness which is self governing and which discovers the reason for action in itself rather than in imitation of the poetic experience (200).

It was his [Plato’s] self-imposed task, building to be sure on the work of predecessors, to establish two main postulates: that of the personality which thinks and knows, and that of a body of knowledge which is thought and known. To do this he had to destroy the immemorial habit of self-identification with the oral tradition. For this had merged the personality with the tradition, and made a self-conscious separation from it impossible (201).

So it is that the long sleep of man is interrupted and his self-consciousness, separating itself from the lazy play of endless saga-series of events, begins to think and to be thought of, ‘itself of itself’, and as it thinks and is thought, man in his new inner isolation confronts the phenomenon of his own autonomous personality and accepts it (210).

Conclusion

What needs to be explained, the explanandum, is the rise of self-consciousness, and the explanation for this, the explanans, is not a new technology of communication, a cosmopolitan life in Miletos, or the geography of Greece, however important these explanans were to the whole historical dynamic. Our focus should be on the aristocratic male culture of ancient Greece and its promotion of ego-consciousness. The Presocratics brought self-consciousness to a level never witnessed before in history through the initiation of true philosophical reflection, a process of introspection initiated by the heroes of the Iliad and the Odyssey, expressed particularly through the greater self-control and power of deliberation the character Odysseus represents. The Indo-Europeans and the heroic Homeric Greeks intensified the consciousness of the male ego, inventing the patriarchal rule of Olympus, the supremacy of sky gods in opposition to the original cult of demonic and inherently unconscious fertility goddesses, which had hitherto ruled all societies, and from which non-Europeans males never managed to detach themselves in the same degree as Indo-European males. We will examine in a future article how the more intense masculinization process associated with the Indo-European pastoral, horse-riding, aristocratic way of life started the emancipation of ego-consciousness from the enveloping world of the Great Mother, in which humans were ruled by the irrationality of chance, demons and witches, entrapped to a world of chthonian darkness, embedded to nature, the emotional impulses of the body, and orgiastic frenzies and hallucinations.

This article was reprinted from the Council of European Canadians [10] Website.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

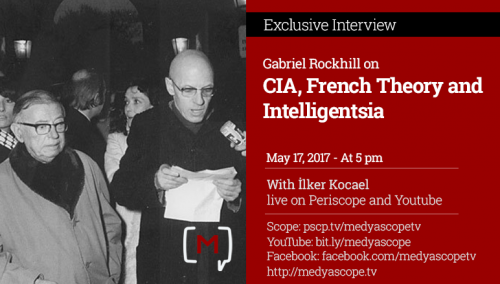

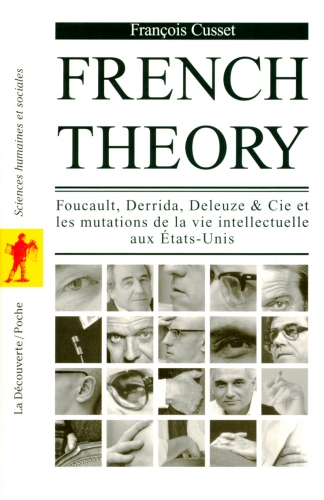

L’interprétation de la French theory par la CIA devrait nous faire réfléchir, dans ce cas, à reconsidérer le vernis radical chic qui a accompagné en grande partie sa réception anglophone. Selon une conception étapiste d’une histoire progressiste (généralement aveugle à sa téléologie implicite), l’œuvre de figures comme Foucault, Derrida et d’autres théoriciens français d’avant-garde est souvent intuitivement associée à une forme de critique radicale et sophistiquée qui dépasse sans doute de loin tout ce que l’on trouve dans les traditions socialistes, marxistes ou anarchistes. Il est certainement vrai, et mérite d’être souligné que la réception anglophone de la French theory, comme John McCumber l’a souligné à juste titre, a eu d’importantes implications politiques en tant que pôle de résistance aux fausses neutralités politiques, aux formalismes techniques rassurants de la logique et du langage, ou au conformisme idéologique direct opérant dans la tradition philosophique anglo-américaine et soutenu par McCarthy. Cependant, les pratiques théoriques des philosophes qui ont tourné le dos à ce que

L’interprétation de la French theory par la CIA devrait nous faire réfléchir, dans ce cas, à reconsidérer le vernis radical chic qui a accompagné en grande partie sa réception anglophone. Selon une conception étapiste d’une histoire progressiste (généralement aveugle à sa téléologie implicite), l’œuvre de figures comme Foucault, Derrida et d’autres théoriciens français d’avant-garde est souvent intuitivement associée à une forme de critique radicale et sophistiquée qui dépasse sans doute de loin tout ce que l’on trouve dans les traditions socialistes, marxistes ou anarchistes. Il est certainement vrai, et mérite d’être souligné que la réception anglophone de la French theory, comme John McCumber l’a souligné à juste titre, a eu d’importantes implications politiques en tant que pôle de résistance aux fausses neutralités politiques, aux formalismes techniques rassurants de la logique et du langage, ou au conformisme idéologique direct opérant dans la tradition philosophique anglo-américaine et soutenu par McCarthy. Cependant, les pratiques théoriques des philosophes qui ont tourné le dos à ce que

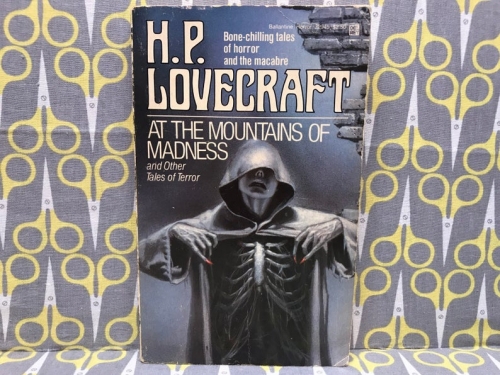

A group led by Lake sets off to investigate the source of the prints and discovers the remains of fourteen mysterious amphibious specimens with star-shaped heads, wings, and triangular feet. They are highly evolved creatures, with five-lobed brains, yet the stratum in which they were found indicates that they are about forty million years old. Shortly thereafter, Lake and his team (with the exception of one man) are slaughtered. When Dyer and the others arrive at the scene, they find six of the specimens buried in large “snow graves” and learn that the remaining specimens have vanished, along with several other items. Additionally, the planes and mechanical devices at the camp were tampered with. Dyer concludes that the missing man simply went mad, wreaked havoc upon the camp, and then ran away.

A group led by Lake sets off to investigate the source of the prints and discovers the remains of fourteen mysterious amphibious specimens with star-shaped heads, wings, and triangular feet. They are highly evolved creatures, with five-lobed brains, yet the stratum in which they were found indicates that they are about forty million years old. Shortly thereafter, Lake and his team (with the exception of one man) are slaughtered. When Dyer and the others arrive at the scene, they find six of the specimens buried in large “snow graves” and learn that the remaining specimens have vanished, along with several other items. Additionally, the planes and mechanical devices at the camp were tampered with. Dyer concludes that the missing man simply went mad, wreaked havoc upon the camp, and then ran away.

27-year-old Hanio Yamada, the protagonist, is a Tokyo-based copywriter who makes a decent living and leads a normal life. But his work leaves him unfulfilled. He later remarks that his job was “a kind of death: a daily grind in an over-lit, ridiculously modern office where everyone wore the latest suits and never got their hands dirty with proper work” (p. 67). One day, while reading the newspaper on the subway, he suddenly is struck by an overwhelming desire to die. That evening, he overdoses on sedatives.

27-year-old Hanio Yamada, the protagonist, is a Tokyo-based copywriter who makes a decent living and leads a normal life. But his work leaves him unfulfilled. He later remarks that his job was “a kind of death: a daily grind in an over-lit, ridiculously modern office where everyone wore the latest suits and never got their hands dirty with proper work” (p. 67). One day, while reading the newspaper on the subway, he suddenly is struck by an overwhelming desire to die. That evening, he overdoses on sedatives.

Arrêté

Arrêté

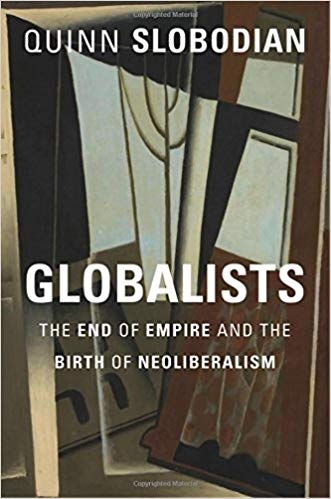

One of the seminal ideological battles of recent history has been that between internationalism, in one form or another, and nationalism. Countless words have been devoted to dissecting the causes, effects, merits, and drawbacks of the various incarnations of these two basic positions. Neoliberalism has, however, succeeded in becoming the dominant internationalist ideology of the power elite and, because nationalism is its natural antithesis, great effort has been expended across all levels of society towards normalizing neoliberal assumptions about politics and economics and demonizing those of nationalism.

One of the seminal ideological battles of recent history has been that between internationalism, in one form or another, and nationalism. Countless words have been devoted to dissecting the causes, effects, merits, and drawbacks of the various incarnations of these two basic positions. Neoliberalism has, however, succeeded in becoming the dominant internationalist ideology of the power elite and, because nationalism is its natural antithesis, great effort has been expended across all levels of society towards normalizing neoliberal assumptions about politics and economics and demonizing those of nationalism. Slobodian begins with the dramatic shift in political and economic conceptions of the world following the First World War. As he observes, the very concept of a “world economy,” along with other related concepts like “world history,” “world literature,” and “world affairs,” entered the English language at this time (p. 28). The relevance of the nineteenth-century classical liberal model was fading as empire faded and both political and economic nationalism arose. As the world “expanded,” so too did the desire for national sovereignty, which, especially in the realm of economics, was seen by neoliberals as a terrible threat to the preservation of the separation of imperium and dominium. A world in which the global economy would be segregated and subjected to the jurisdiction of states and the collective will of their various peoples was antithetical to the neoliberal ideal of free trade and economic internationalism; i.e., the maintenance of a “world economy.”

Slobodian begins with the dramatic shift in political and economic conceptions of the world following the First World War. As he observes, the very concept of a “world economy,” along with other related concepts like “world history,” “world literature,” and “world affairs,” entered the English language at this time (p. 28). The relevance of the nineteenth-century classical liberal model was fading as empire faded and both political and economic nationalism arose. As the world “expanded,” so too did the desire for national sovereignty, which, especially in the realm of economics, was seen by neoliberals as a terrible threat to the preservation of the separation of imperium and dominium. A world in which the global economy would be segregated and subjected to the jurisdiction of states and the collective will of their various peoples was antithetical to the neoliberal ideal of free trade and economic internationalism; i.e., the maintenance of a “world economy.”

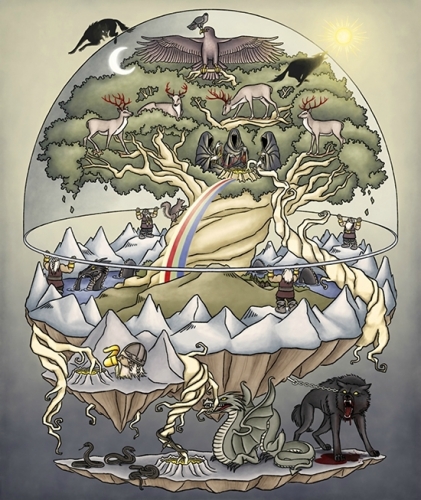

La mythologie nordique et le monde germano-scandinave jouissent d’un intérêt grandissant, et d’une vulgarisation pas toujours heureuse. La série Vikings, plutôt décevante, n’est pas vraiment ce que l’on peut appeler une « série historique réaliste ». D’ailleurs feu Régis Boyer préférait ne pas faire de commentaire à son sujet… Cependant, et d’un point de vue positif, certains ont pu (re)découvrir un imaginaire, une culture, et un univers qui leur ait souvent plus proche qu’il n’y paraît. En bonus, ils auront pu également découvrir l’excellente musique du groupe norvégien Wardruna !

La mythologie nordique et le monde germano-scandinave jouissent d’un intérêt grandissant, et d’une vulgarisation pas toujours heureuse. La série Vikings, plutôt décevante, n’est pas vraiment ce que l’on peut appeler une « série historique réaliste ». D’ailleurs feu Régis Boyer préférait ne pas faire de commentaire à son sujet… Cependant, et d’un point de vue positif, certains ont pu (re)découvrir un imaginaire, une culture, et un univers qui leur ait souvent plus proche qu’il n’y paraît. En bonus, ils auront pu également découvrir l’excellente musique du groupe norvégien Wardruna ! Nous parlions d’un auteur « maison » en la personne de Halfdan Rekkirson. Celui-ci compte deux ouvrages à son actif. Le premier s’intitule Calendrier runique Asatru. L’Asatru est une religion néo-païenne qui s’est donnée comme mission de réanimer la vielle foi du Nord. Ce courant, qui se porte bien soit dit en passant, se rencontre principalement en Islande et dans les pays anglo-saxons, États-Unis et Grande-Bretagne en tête. L’ouvrage de Rekkirson témoigne avant toute chose d’un travail sérieux. Élaborer un calendrier n’est pas chose facile ! Le pari est pourtant relevé ! En outre, l’auteur développe certains sujets comme l’interprétation des contes ou l’importance de la Déesse Frigg. C’est un livre roboratif et plaisant à lire.

Nous parlions d’un auteur « maison » en la personne de Halfdan Rekkirson. Celui-ci compte deux ouvrages à son actif. Le premier s’intitule Calendrier runique Asatru. L’Asatru est une religion néo-païenne qui s’est donnée comme mission de réanimer la vielle foi du Nord. Ce courant, qui se porte bien soit dit en passant, se rencontre principalement en Islande et dans les pays anglo-saxons, États-Unis et Grande-Bretagne en tête. L’ouvrage de Rekkirson témoigne avant toute chose d’un travail sérieux. Élaborer un calendrier n’est pas chose facile ! Le pari est pourtant relevé ! En outre, l’auteur développe certains sujets comme l’interprétation des contes ou l’importance de la Déesse Frigg. C’est un livre roboratif et plaisant à lire.

However, Stoddard departed from Grant in meaningful ways and, while some of Grant’s work is commendable, Stoddard’s deviations from it are almost uniformly for the better. In

However, Stoddard departed from Grant in meaningful ways and, while some of Grant’s work is commendable, Stoddard’s deviations from it are almost uniformly for the better. In  Stoddard foresaw that capitalism would encourage the importation of non-white labor that would outcompete whites not in its quality, but in its quantity and its willingness to work for practically nothing. This willingness is owed to the fact that, given the Malthusian pressures triggered by the overpopulation of their nations, even the most meager subsistence would be preferable from their perspective. Needless to say, this prediction has been made manifest in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and elsewhere. Stoddard predicted that the Islamic Revival would bring the Muslim world into war against the West and that black Africans would align with Muslims in this effort. Stoddard predicted that internecine rivalries between non-whites would be put aside in favor of a sort-of rainbow coalition that would persist up until the moment that the white world had been defeated. He also predicted that the moral grandstanding about national self-determination during and after the First World War would make continued maintenance of the massive European colonial empires an impossibility. This seems obvious in retrospect – the values codified at Versailles both incentivized the creation of nationalist movements across the European colonies and made the ruling position blatantly and indefensibly hypocritical – but it must not have been to the contemporary British and French ruling class, who made efforts (with varying degrees of intensity) to cling to their empires into the 1960s. He predicted that the Bolsheviks would persuade discontented colored nationalists to the cause of Communism. He predicted that Japan would challenge the West for hegemony over Asia – another accurate prediction, although its impressiveness is mitigated by the fact that this was already a widespread belief following the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. He also presaged Samuel Huntington by prophesying that the struggle between various races and cultures, rather than Marxist materialist concerns, would be the primary cause of conflict and consciousness in the twentieth century and beyond.

Stoddard foresaw that capitalism would encourage the importation of non-white labor that would outcompete whites not in its quality, but in its quantity and its willingness to work for practically nothing. This willingness is owed to the fact that, given the Malthusian pressures triggered by the overpopulation of their nations, even the most meager subsistence would be preferable from their perspective. Needless to say, this prediction has been made manifest in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and elsewhere. Stoddard predicted that the Islamic Revival would bring the Muslim world into war against the West and that black Africans would align with Muslims in this effort. Stoddard predicted that internecine rivalries between non-whites would be put aside in favor of a sort-of rainbow coalition that would persist up until the moment that the white world had been defeated. He also predicted that the moral grandstanding about national self-determination during and after the First World War would make continued maintenance of the massive European colonial empires an impossibility. This seems obvious in retrospect – the values codified at Versailles both incentivized the creation of nationalist movements across the European colonies and made the ruling position blatantly and indefensibly hypocritical – but it must not have been to the contemporary British and French ruling class, who made efforts (with varying degrees of intensity) to cling to their empires into the 1960s. He predicted that the Bolsheviks would persuade discontented colored nationalists to the cause of Communism. He predicted that Japan would challenge the West for hegemony over Asia – another accurate prediction, although its impressiveness is mitigated by the fact that this was already a widespread belief following the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. He also presaged Samuel Huntington by prophesying that the struggle between various races and cultures, rather than Marxist materialist concerns, would be the primary cause of conflict and consciousness in the twentieth century and beyond. Today, the unfortunate veracity of Stoddard’s predictions has reignited interest in his scholarship, sympathetically in dissident circles and, of course, negatively in the establishment. The similarity of his predictions to the “Great Replacement” which we observe today will not be lost on any conscious reader. It is safe to say that this is the reason that Stoddard has recently begun reappearing in Leftist publications.

Today, the unfortunate veracity of Stoddard’s predictions has reignited interest in his scholarship, sympathetically in dissident circles and, of course, negatively in the establishment. The similarity of his predictions to the “Great Replacement” which we observe today will not be lost on any conscious reader. It is safe to say that this is the reason that Stoddard has recently begun reappearing in Leftist publications.  The central question of the debate was “Shall the Negro Be Encouraged to Seek Cultural Equality?,” a concept which had never been relevant to Stoddard’s research but was the entire raison d’etre for Du Bois’ career. Moreover, the framing of the question was such that, even at the time, it would have been impossible to make a cogent argument against it. The contrary position, that whites should actively discourage blacks from bettering themselves, would not have been how segregationists presented their position. And, of course, Du Bois was not asking for whites to “encourage” blacks to “seek” their own achievements – that was the position of Booker T. Washington, his hated nemesis. Du Bois’ goal was to dissolve white institutions, or at least inject blacks into them, and to accomplish a Marxist redistribution of wealth along racial lines.

The central question of the debate was “Shall the Negro Be Encouraged to Seek Cultural Equality?,” a concept which had never been relevant to Stoddard’s research but was the entire raison d’etre for Du Bois’ career. Moreover, the framing of the question was such that, even at the time, it would have been impossible to make a cogent argument against it. The contrary position, that whites should actively discourage blacks from bettering themselves, would not have been how segregationists presented their position. And, of course, Du Bois was not asking for whites to “encourage” blacks to “seek” their own achievements – that was the position of Booker T. Washington, his hated nemesis. Du Bois’ goal was to dissolve white institutions, or at least inject blacks into them, and to accomplish a Marxist redistribution of wealth along racial lines. Stoddard says that “the more enlightened men of southern white America” are trying to ensure that, while the races are kept separate, that the facilities to which they have access are nonetheless equal in quality. This elicited laughter from the black audience, who found the claim to be ridiculous. Stoddard then informed them that he did not see the joke, apparently eliciting more whooping. Angered, Stoddard rebutted that bi-racial cooperation of the Atlanta Compromise mold was making more progress than anything Du Bois was attempting – another apt prediction, for Du Bois died having accomplished none of his goals. Du Bois gave up on “progress” in the US and eventually moved to observe and admire Mao Zedong’s brutality in China before settling in Ghana. His NAACP was and remains little more than a debating and protesting society. From its inception in 1909, the NAACP incessantly complained for over fifty years until other acronymous black organizations, aided by the bayonets of the National Guard and the Cold War exigencies of “winning hearts and minds,” ended the white near-monopoly on American political power.

Stoddard says that “the more enlightened men of southern white America” are trying to ensure that, while the races are kept separate, that the facilities to which they have access are nonetheless equal in quality. This elicited laughter from the black audience, who found the claim to be ridiculous. Stoddard then informed them that he did not see the joke, apparently eliciting more whooping. Angered, Stoddard rebutted that bi-racial cooperation of the Atlanta Compromise mold was making more progress than anything Du Bois was attempting – another apt prediction, for Du Bois died having accomplished none of his goals. Du Bois gave up on “progress” in the US and eventually moved to observe and admire Mao Zedong’s brutality in China before settling in Ghana. His NAACP was and remains little more than a debating and protesting society. From its inception in 1909, the NAACP incessantly complained for over fifty years until other acronymous black organizations, aided by the bayonets of the National Guard and the Cold War exigencies of “winning hearts and minds,” ended the white near-monopoly on American political power.

Philippe de Villiers en vilipende les fondements intellectuels. Ceux-ci reposeraient sur un trio infernal, sur une idéologie hors sol ainsi que sur un héritier omnipotent. Le trio regroupe Robert Schuman, Walter Hallstein et Jean Monnet. Le premier fut le ministre démocrate-chrétien français des Affaires étrangères en 1950. Le deuxième présida la Commission européenne de 1958 à 1967. Le troisième incarna les intérêts anglo-saxons sur le Vieux Continent. Ensemble, ils auraient suscité un élan européen à partir des prémices du droit national-socialiste, du juridisme venu d’Amérique du Nord et d’une défiance certaine à l’égard des États membres. Quant à l’héritier, il désigne « le fils spirituel (p. 255) », George Soros.

Philippe de Villiers en vilipende les fondements intellectuels. Ceux-ci reposeraient sur un trio infernal, sur une idéologie hors sol ainsi que sur un héritier omnipotent. Le trio regroupe Robert Schuman, Walter Hallstein et Jean Monnet. Le premier fut le ministre démocrate-chrétien français des Affaires étrangères en 1950. Le deuxième présida la Commission européenne de 1958 à 1967. Le troisième incarna les intérêts anglo-saxons sur le Vieux Continent. Ensemble, ils auraient suscité un élan européen à partir des prémices du droit national-socialiste, du juridisme venu d’Amérique du Nord et d’une défiance certaine à l’égard des États membres. Quant à l’héritier, il désigne « le fils spirituel (p. 255) », George Soros. Outre le rappel du passé national-socialiste de Hallstein, il insiste que Robert Schuman, « le père de l’Europe fut ministre de Pétain et participa à l’acte fondateur du régime de Vichy (p. 67) ». Oui, Robert Schuman a appartenu au premier gouvernement du Maréchal Pétain. Il n’était pas le seul. Philippe de Villiers ne réagit pas quand Maurice Couve de Murville lui dit à l’occasion d’une conversation au Sénat en juillet 1986 : « Je me trouvais à Alger […] quand Monnet a débarqué. J’étais proche de lui, depuis 1939. À l’époque, j’exerçais les fonctions de commissaire aux finances de Vichy (p. 109). » L’ancien Premier ministre du Général De Gaulle aurait pu ajouter que membre de la Commission d’armistice de Wiesbaden, il était en contact quotidien avec le Cabinet du Maréchal. Sa présence à Alger n’était pas non plus fortuite. Il accompagnait en tant que responsable des finances l’Amiral Darlan, le Dauphin du Maréchal !

Outre le rappel du passé national-socialiste de Hallstein, il insiste que Robert Schuman, « le père de l’Europe fut ministre de Pétain et participa à l’acte fondateur du régime de Vichy (p. 67) ». Oui, Robert Schuman a appartenu au premier gouvernement du Maréchal Pétain. Il n’était pas le seul. Philippe de Villiers ne réagit pas quand Maurice Couve de Murville lui dit à l’occasion d’une conversation au Sénat en juillet 1986 : « Je me trouvais à Alger […] quand Monnet a débarqué. J’étais proche de lui, depuis 1939. À l’époque, j’exerçais les fonctions de commissaire aux finances de Vichy (p. 109). » L’ancien Premier ministre du Général De Gaulle aurait pu ajouter que membre de la Commission d’armistice de Wiesbaden, il était en contact quotidien avec le Cabinet du Maréchal. Sa présence à Alger n’était pas non plus fortuite. Il accompagnait en tant que responsable des finances l’Amiral Darlan, le Dauphin du Maréchal !

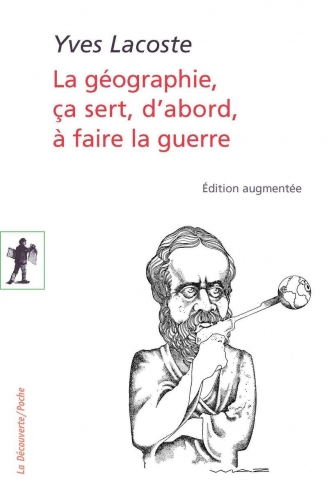

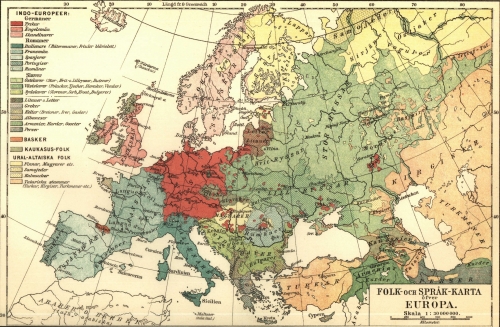

Les principaux manuels de géopolitiques, notamment celui que le Professeur David Criekemans a rédigé selon les critères de la plus haute scientificité dans le cadre de l’Université de Louvain, commencent presque toujours par une histoire de cette discipline depuis les premières tentatives de saisir conceptuellement les faits géographiques, non pas tant dans une perspective purement empirique mais surtout dans une perspective stratégique, notamment à l’aide de la cartographie établie par Carl Ritter, de l’anthropo-géographie de Ratzel ou des définitions données par le Suédois Rudolf Kjellén. C’est, personne ne le niera, un travail des plus utiles, ce qui était aussi mon intention lorsque feu le Professeur Jean-François Mattéi m’avait invité à présenter les penseurs de la géopolitique dans sa remarquable Encyclopédie des Œuvres philosophiques entre 1990 et 1992, encyclopédie qui fut ultérieurement publiée aux Presses Universitaires de France. L’intention du Prof. Mattéi correspondait à celle qu’avait déjà formulée le géopolitologue Yves Lacoste, à savoir élargir le cadre de la discipline, philosophique pour le premier, géographique/géopolitique pour le second. Mattéi voulait donc élargir le champ de la philosophie, tout simplement parce que plus aucune philosophie sérieuse ne peut encore être pensée sans tenir compte du temps et de l’espace, de l’émergence de tous les phénomènes, faits, modes de pensée et aspirations religieuses ou éthiques qui, tous, nécessairement, se déploient en des lieux et des périodes précises qu’ils influencent ensuite en profondeur, les inscrivant dans la durée et leur assurant une résilience difficilement éradicable.

Les principaux manuels de géopolitiques, notamment celui que le Professeur David Criekemans a rédigé selon les critères de la plus haute scientificité dans le cadre de l’Université de Louvain, commencent presque toujours par une histoire de cette discipline depuis les premières tentatives de saisir conceptuellement les faits géographiques, non pas tant dans une perspective purement empirique mais surtout dans une perspective stratégique, notamment à l’aide de la cartographie établie par Carl Ritter, de l’anthropo-géographie de Ratzel ou des définitions données par le Suédois Rudolf Kjellén. C’est, personne ne le niera, un travail des plus utiles, ce qui était aussi mon intention lorsque feu le Professeur Jean-François Mattéi m’avait invité à présenter les penseurs de la géopolitique dans sa remarquable Encyclopédie des Œuvres philosophiques entre 1990 et 1992, encyclopédie qui fut ultérieurement publiée aux Presses Universitaires de France. L’intention du Prof. Mattéi correspondait à celle qu’avait déjà formulée le géopolitologue Yves Lacoste, à savoir élargir le cadre de la discipline, philosophique pour le premier, géographique/géopolitique pour le second. Mattéi voulait donc élargir le champ de la philosophie, tout simplement parce que plus aucune philosophie sérieuse ne peut encore être pensée sans tenir compte du temps et de l’espace, de l’émergence de tous les phénomènes, faits, modes de pensée et aspirations religieuses ou éthiques qui, tous, nécessairement, se déploient en des lieux et des périodes précises qu’ils influencent ensuite en profondeur, les inscrivant dans la durée et leur assurant une résilience difficilement éradicable. Lacoste a prouvé que la géographie sert les chefs de guerre en démontrant que les premières tentatives de dessiner des cartes dans la Chine de l’antiquité servaient à indiquer les voies à suivre aux chefs de guerre, de manière à ce qu’ils puissent mouvoir leurs armées de manière optimale dans les paysages et terrains divers de leur propre pays ou dans le pays de l’ennemi. Ensuite, dans un livre succinct, mais rédigé de manière magistrale, il nous a montré que le Prince Henri du Portugal, Anglais par sa mère, a fondé et soutenu son « école de la mer » afin de trouver de nouvelles voies maritimes extra-méditerranéennes pour que l’écoumène chrétien/européen de son époque puisse trouver le chemin vers les épices indiennes et vers le mystérieux « Cathay » en échappant aux blocus terrestres et maritimes que lui imposait le contrôle turc/ottoman des accès aux routes continentales vers l’Asie et des voies maritimes en Méditerranée. Quelques décennies plus tard, les Portugais livreront bataille dans la Corne de l’Afrique et des navires lusitaniens surgiront face aux côtes du Gujarat en Inde pour vaincre glorieusement une flotte musulmane. Tant les seigneurs de la guerre que les empereurs chinois du monde antique et que le Prince Henri du Portugal ont donc fait dessiner des cartes pour que des militaires ou des marins avisés puissent mener la guerre ou des expéditions exploratrices de manière optimale. Le raisonnement de Lacoste est parfaitement exact, et fut posé en dépit de son engagement idéologique dans les rangs de la gauche pacifiste.

Lacoste a prouvé que la géographie sert les chefs de guerre en démontrant que les premières tentatives de dessiner des cartes dans la Chine de l’antiquité servaient à indiquer les voies à suivre aux chefs de guerre, de manière à ce qu’ils puissent mouvoir leurs armées de manière optimale dans les paysages et terrains divers de leur propre pays ou dans le pays de l’ennemi. Ensuite, dans un livre succinct, mais rédigé de manière magistrale, il nous a montré que le Prince Henri du Portugal, Anglais par sa mère, a fondé et soutenu son « école de la mer » afin de trouver de nouvelles voies maritimes extra-méditerranéennes pour que l’écoumène chrétien/européen de son époque puisse trouver le chemin vers les épices indiennes et vers le mystérieux « Cathay » en échappant aux blocus terrestres et maritimes que lui imposait le contrôle turc/ottoman des accès aux routes continentales vers l’Asie et des voies maritimes en Méditerranée. Quelques décennies plus tard, les Portugais livreront bataille dans la Corne de l’Afrique et des navires lusitaniens surgiront face aux côtes du Gujarat en Inde pour vaincre glorieusement une flotte musulmane. Tant les seigneurs de la guerre que les empereurs chinois du monde antique et que le Prince Henri du Portugal ont donc fait dessiner des cartes pour que des militaires ou des marins avisés puissent mener la guerre ou des expéditions exploratrices de manière optimale. Le raisonnement de Lacoste est parfaitement exact, et fut posé en dépit de son engagement idéologique dans les rangs de la gauche pacifiste. Mais s’il existe des permanences immuables en géopolitique, comment devons-nous repérer celles qui se manifestent dans le cadre géographique de nos bas pays ? La méthode, que je souhaite utiliser ici, et que j’ai toujours utilisée notamment dans l’écriture de ma trilogie, qui porte pour titre Europa, est celle d’un géopolitologue non politisé du temps de la République de Weimar. Son nom était Richard Henning (1874-1951), auteur d’un ouvrage très copieux, Geopolitik – Die Lehre vom Staat als Lebewesen, qui a connu cinq éditions successives. Henning avait une écriture très claire, limpide, n’utilisait jamais un jargon compliqué et illustrait chacun de ses arguments par des cartes précises. Au départ, sa discipline était la géographie des communications et des transports, renforcée par une géographie historique, où il mettait toujours l’accent sur le rôle des états, des hommes d’état et des surdoués politiques dans l’organisation et la transformation des espaces. Sa thèse centrale était de dire, à son époque, que les données spatiales d’un peuple devaient être davantage valorisées conceptuellement plutôt que les facteurs raciaux, ce qui le fit entrer en conflit avec les thèses officielles du pouvoir sous le Troisième Reich, même si, Prussien natif de Berlin, il défendait le principe clausewitzien d’une nécessaire militarisation défensive de tout état, en tenant compte, bien sûr, du vieil adage romain, Si vis pacem, para bellum. Dans les années 50 et 60 du 20ème siècle, son œuvre exerça une influence importante en Argentine sous le régime du Général Juan Peron et, plus tard, s’est retrouvée en filigrane dans les cours des écoles militaires du pays.