Une conférence de Pierre-Emile Blairon

Ex: https://liguedumidi.com

Bonsoir, mes amis,

Merci de votre présence, merci à Richard Roudier de m’avoir invité pour évoquer le souvenir de l’un de nos plus chers amis disparus dans la nuit du 6 au 7 mars 2019 : Guillaume Faye ; c’est le 13 mars, dans un petit cimetière du Poitou, un jour pluvieux et triste, parmi des gens que je n’avais pas revu depuis des années, que je me suis posé la question :

Qu’est-ce qu’un ami ?

c’est quelqu’un à qui on ne demande rien, qui ne demande rien, dont on n’a pas besoin, qui n’a pas besoin de vous, que vous pouvez voir tous les jours ou tous les trois ans, mais qui est toujours là en permanence et dont on sait qu’il a une vie parallèle à la vôtre, qu’il a les mêmes réactions que vous sur tel sujet alors qu’il est à l’autre bout de la planète, c’est votre double, pas besoin de regarder sa photo, il suffit de se regarder dans une glace. Vous me direz, à quoi ça sert alors, un ami ? ça sert à savoir que vous n’êtes pas seul au monde même quand ce que vous aimez le plus au monde, c’est votre solitude ; mais, dans notre milieu, un ami, c’est encore plus que ça ; parce que nous ne participons pas du monde tel qu’il est, parce que nous le rejetons et qu’il nous le rend bien ; parce que nous sommes une toute petite minorité de gens lucides et conscients ; l’amitié, dans le monde que nous vivons, c’est une fraternité d’êtres différenciés, comme disait Evola, les hommes qui restent debout parmi les ruines et, parce qu’ils sont lucides et conscients, souffrent plus que les autres de voir leur pays, l’une des cultures qui a apporté le plus au monde rabaissée au rang d’une république bananière, de voir un patrimoine européen vieux de plusieurs milliers d’années abandonné par ceux qui sont en charge de le préserver, voir le sol de leurs ancêtres souillé par des hordes de populations non-européennes qui ne respectent pas la terre qui les accueille.

Les Occidentalistes

Je suis de la génération de Richard ; pour situer, j’avais 20 ans en 68 ; nous avons commencé à militer à la fin des années 60 ; pour la plupart d’entre nous, nous n’avions pas des idées bien formées ; nos références dataient de l’après-guerre mondiale ou de la guerre d’Algérie, nous étions nationalistes ou régionalistes, par atavisme et par intuition, mais nous n’avions pas de solide formation politique ou doctrinale, encore moins spirituelle, nous étions alors ce qu’on appelle des activistes, des militants de terrain. Nous avions surtout des modèles, des héros de l’histoire récente comme le capitaine Sergent, capitaine de la Légion, l’un des responsables de l’OAS, qui avait fondé le MJR, Mouvement Jeune Révolution où j’ai milité, après Occident et avant Ordre nouveau.

Nous étions alors des « occidentalistes », comme le nom même du premier mouvement militant auquel j’ai appartenu l’exprime, Occident, c’est-à-dire : la nation + l’Europe + l’Amérique, voire, pour certains, + Israël.

C’est lorsque j’ai appris, notamment grâce à Guillaume, à séparer l’Europe de l’Occident que je suis devenu un Européen régionaliste. Nous étions anti-marxistes, anti-gaullistes, anti-immigration, en fait plutôt anti tout que pro quelque chose, nous étions bien jeunes, bien ignorants et bien rebelles, mais nous avions déjà repéré quelques dysfonctionnements de l’époque et je me souviens de l’un des slogans d’Ordre nouveau : 3 millions d’immigrés = 3 millions de chômeurs, ce même slogan qu’on pourrait reprendre, en le multipliant par 5 : 15 millions d’immigrés=15 millions de chômeurs, ça doit d’ailleurs correspondre aux véritables chiffres qu’on nous cache.

Ceux qui militaient à l’époque dans ces groupes « natios » étaient au moins aussi contestataires de la société bourgeoise que leurs ennemis gauchistes de l’époque, les petit-bourgeois, fils de grands bourgeois, qui ont lancé la rébellion de mai 1968 ; la plupart des leaders de mai 68 sont maintenant aux postes-clés de cette société capitaliste et uniformiste qu’ils dénonçaient. Il faut dire que, de notre côté, très peu ont conservé les convictions de leur jeunesse ; la grande majorité de ceux qui militaient avec nous est rentrée dans le rang et s’est fondue dans la masse ; seule, une petite élite a continué le combat militant, les éveilleurs sont issus de cette petite élite.

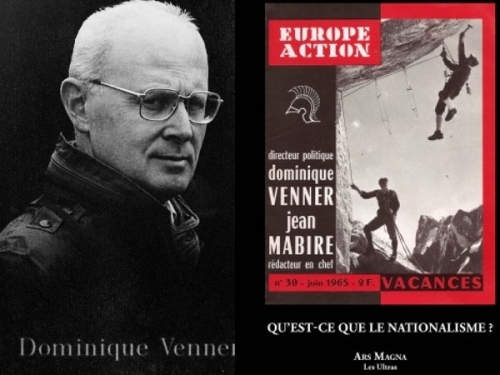

C’est à cette même époque, vers 1968, qu’est apparu un groupe qui s’est appelé d’abord Europe Action, fondé par Dominique Venner, groupe issu, lui aussi, en partie de l’aventure algérienne, quand je dis « aventure », c’est au sens noble, je devrais dire plutôt épopée ; c’est avec eux et grâce à eux que, pour la plupart d’entre nous, nous avons alors reçu nos premières et solides formations politiques et métapolitiques ; et, à mon avis, ce qui est le plus important, c’est grâce à ce groupe que nous avons été confrontés à notre véritable identité, notre passé préchrétien de Gaulois, nous avons rencontré nos racines ; la base était alors construite, il ne restait plus qu’à construire la maison. Ce qui sera fait essentiellement par celui dont aujourd’hui nous célébrons la mémoire, Guillaume Faye.

L’émergence d’un diable de sa boîte

C’est des rangs de ce groupe Europe-Action, lui-même en partie issu de la FEN, Fédération des étudiants nationalistes, qui s’est bientôt appelé GRECE, Groupe de Recherches et d’Etudes pour la Civilisation Européenne, puis « pour la Culture Européenne », qu’a émergé, je dirais plutôt surgi, tel un diable de sa boîte, un jeune homme fringant, bien mis, découvert par Venner, et qui a renversé les tables, toutes les tables, même celles de la Loi, avec sa fougue et son talent ; il se trouve que j’avais fait mes études à Aix, et que j’y suis resté pour y vivre, et le lieu de rencontre estivale du groupe était une grande maison, la Domus, près d’Aix-en-Provence. C’est là que j’ai rencontré pour la première fois celui qui allait devenir le brillant porte-parole de ce qu’on appellera plus tard la « Nouvelle droite » et son inventif théoricien. Je me souviens que, déjà, à l’époque, il n’était pas seulement un intellectuel ; il avait aussi le don du théâtre et de la farce et il nous enchantait avec des saynètes qu’il improvisait pour nous faire rire.

Mais plus de 40 ans après, l’Histoire émet son verdict : Guillaume Faye était bien plus que ça.

Guillaume Faye, un éveilleur

Guillaume Faye était un éveilleur. Les éveilleurs sont des hommes qui viennent de cet autre monde parallèle au nôtre, un monde immanent, immuable, permanent, pour accomplir une mission. Ces hommes-là n’ont pas d’autre préoccupation que de transmettre leur savoir et leur énergie ; leur vie entière est consacrée à cette transmission. Les éveilleurs apparaissent à des périodes critiques de l’Histoire, lorsque tout est chamboulé, que toutes les valeurs sont inversées, que la situation semble désespérée ; ils font passer leur mission avant leur propre personne, leur intérêt personnel, leur confort ; leur règle d’or est celle-ci : fais ce que tu dois, sans préjuger de la réussite. La famille des La Rochefoucault en avait fait sa devise : « Fais ce que dois, advienne que pourra ».

J’ai eu la chance de connaître les principaux éveilleurs français contemporains, certains qui furent mes amis et qui le sont toujours, je pourrais citer, outre Guillaume, Marc Augier, que j’ai rencontré quelques temps avant sa mort à Lyon, Jean Mabire, Robert Dun, de son nom véritable Maurice Martin, Pierre Vial que je rencontre régulièrement, tout comme Paul-Georges Sansonetti ; et vous avez la chance dans votre région d’avoir toute une famille d’éveilleurs, ce qui n’est pas banal, les Roudier ! Au moins deux générations de Roudier, de guerriers qui se battent comme des lions pour notre cause.

Guillaume Faye possédait toutes les caractéristiques de l’éveilleur, comme tous ceux que je viens de citer.Un éveilleur est d’abord un transmetteur, il peut être un exemple, un modèle, voire un maître, mais ce n’est pas un gourou.

Ce n’est pas un intellectuel non plus, tel qu’on l’entend de nos jours, un éveilleur n’est pas là pour perdre son temps à des discussions sans fin sur le sexe des anges ; un éveilleur est un réaliste, même s’il peut apparaître comme mystique. Il a une mission qu’il connaît et qu’il doit accomplir, il est sur cette terre dans cet unique but. Tout le reste n’est que contingence accessoire. Quand il parle ou quand il écrit, il n’emploie pas des mots que personne ne comprend, comme ces pseudo-intellectuels qui ont besoin de pratiquer un quelconque jargon pour faire croire qu’ils sont intelligents, ou pour bien faire comprendre au petit peuple qu’ils font partie d’un cénacle fermé, c’est ridicule et pathétique ; l’éveilleur n’a pas besoin de ces artifices. Il ne cherche pas à se distinguer par la recherche de la nouveauté à tout prix, de toutes façons, il n’y a rien de nouveau sous le soleil.

Ce n’est pas un philosophe, autoproclamé ou pas, même s’il est amoureux de la sagesse, comme l’indique le mot lui-même, mais ce mot a subi tellement d’avatars qu’il ne veut plus dire ce qu’il exprime.

Ce n’est pas un philosophe, autoproclamé ou pas, même s’il est amoureux de la sagesse, comme l’indique le mot lui-même, mais ce mot a subi tellement d’avatars qu’il ne veut plus dire ce qu’il exprime.

Un éveilleur n’est pas un « rebelle » : les rebelles sont toujours des pseudo-rebelles, pas plus rebelles que leurs mèches qu’ils rejettent en arrière avec affectation, rebelles de salons… de coiffure, velléitaires qui se donnent des frissons à bon compte mais qui tiennent avant tout à leur confort matériel et à leur image de marque. Un éveilleur n’est pas un rebelle, c’est un révolutionnaire.

Un éveilleur est un homme simple, modeste, il n’a pas besoin de se mettre en avant ; seuls, les personnes qui se sentent en situation d’infériorité ont besoin de se hausser du col. Il est complètement dépourvu de vanité, il ne souffre pas de narcissisme ni d’ego surdimensionné, car cet état est une véritable maladie, une pathologie bien définie par la science médicale dont sont atteints la quasi-totalité des individus appartenant aux classes dirigeantes. Quand je parle de classes dirigeantes, je ne pense pas seulement aux politiques, mais aussi aux médias, aux syndicats, aux magistrats, aux banksters, aux ONG, aux publicitaires, aux associations, aux multinationales, aux saltimbanques, etc.

Un éveilleur peut s’exprimer de différentes façons, selon son caractère ou les dons que les divinités ont mis à sa disposition pour transmettre le message qu’elles lui ont confié. Guillaume était, entre autres, un éveilleur provocateur.

Guillaume le provocateur

Guillaume Faye a été traité de provocateur, notamment par Martial Bild, lors de sa dernière intervention télévisée, dans un entretien accordé à TV Libertés. Ce à quoi Guillaume a répondu : « mais je suis là pour provoquer ; provocation, c’est un mot qui vient du latin provocare : inciter les autres à vous répondre, à réfléchir. » En quelque sorte, l’éveilleur Faye voulait vérifier sur-le-champ le résultat de son travail, un éveilleur, comme son nom l’indique consiste à réveiller les hommes endormis, à balancer un grand seau d’eau sur la tête de celui qui dort. C’est aussi celui qui empêche un homme perdu dans un désert de glace en haute montagne, par exemple, de s’endormir, celui qui s’endort dans un tel contexte est un homme mort. Et nous sommes dans ce contexte. A l’heure actuelle.

Je me souviens d’avoir été expulsé d’un restaurant en compagnie de Guillaume parce qu’il émettait haut et fort des considérations qui n’étaient pas du tout politiquement correctes et les gens de la table à côté, après avoir essayé de le faire taire, ce qui l’a mis encore plus en forme, ont demandé au tenancier du bistrot de nous faire sortir sous peine d’appeler la police, forts de leur bon droit, du sentiment qu’ils avaient d’être dans la bien-pensance universelle. Ce qui s’est passé, parce que le bistrotier ne voulait pas de scandale, parce qu’il nous a demandé gentiment de déguerpir, ce que nous avons accepté, tout aussi gentiment. A ma connaissance, Guillaume ne s’est jamais fait casser la figure, ce qui aurait pu lui arriver plusieurs fois mais je me suis aperçu – parce que, à son exemple, je continue encore à pratiquer ce type de provocation avec d’autres amis – je me suis aperçu que les gens sont trop timorés pour oser répliquer, ils se demandent qui sont ces vieux fous avec ces drôles d’idées, et puis parce qu’ils n’ont pas d’arguments. La propagande antiraciste a fait des ravages sur les Français. Ils sont atones, muets, décérébrés, ahuris.

C’est l’un de mes désaccords avec Guillaume : la thèse d’un sursaut révolutionnaire global des Français qu’il soutient dans son dernier livre, La Guerre civile raciale ; je crois, moi, que les Français sont trop anesthésiés pour se révolter ; la révolte des Gilets jaunes n’aborde jamais, ou très peu, le problème crucial de l’immigration parce que c’est un sujet tabou. Il y a eu juste quelques manifestations contre le Pacte de Marrakech pendant une courte période. Je crois plutôt que le réveil, si réveil il y a, se fera grâce à une minorité d’hommes différenciés, lucides et combatifs, qui combattront sans états d’âme. Mais, bien sûr, je peux me tromper et il peut avoir eu raison. L’avenir très proche nous le dira, nous n’allons pas attendre bien longtemps pour le vérifier. Sans sursaut révolutionnaire, nous allons disparaître physiquement, sauf à nous enfuir vers un pays de l’Est.

Un talent aux multiples facettes

Le génie de Guillaume Faye s’est exprimé de différentes façons et à diverses époques. Mais la structure de sa pensée est homogène ; quoiqu’on en ait pensé, il ne s’est jamais contredit.

On pourra remarquer, à travers les choix stratégiques qu’il a faits tout au long de sa vie et qu’il a martelés dans son œuvre, une évolution qui s’est faite du haut vers le bas, du concept idéologique vers la réalité du terrain. Guillaume Faye était un militant de terrain : toute son œuvre ne vise, finalement, qu’à suggérer les solutions d’urgence et à définir les modalités nécessaires à leur application réaliste et efficace. Guillaume se réclamait d’Aristote, ce philosophe pour lequel tout devait être démontré.

Guillaume s’est investi dans de nombreuses activités très différentes où il a excellé dans chacune d’entre elles.

C’était d’abord un orateur brillant et passionné, son discours souvent improvisé était marqué par des fulgurance géniales qu’il découvrait en même temps que le public et dont il s’émerveillait lui-même ; la plupart des conférenciers ont besoin de suivre une trame, comme moi qui suis incapable de parler sans notes, à moins d’oublier la moitié de ce que je m’étais promis de dire ; un bout de papier suffisait à Guillaume, et encore faut-il rappeler que je ne l’ai pas vu démarrer une conférence sans une bonne dose de son carburant préféré, bière ou vin.

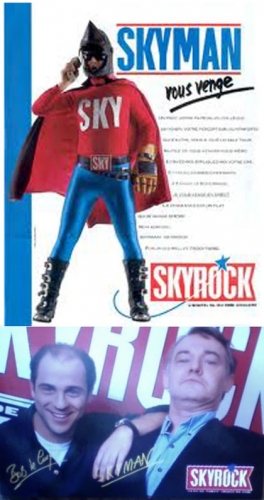

Pendant une période qui a quand même duré dix ans, de 1987 à 1997, Il a été un animateur de radio reconnu sous le nom de Skyman, et aussi de télévision sur France 2 où il imaginait des canulars dans l’émission Télématin. Il a aussi, pendant cette même période, collaboré à des revues de bandes dessinées comme L’Echo des savanes, en compagnie d’auteurs plus ou moins déjantés généralement situés à l’extrême-gauche.

Pendant une période qui a quand même duré dix ans, de 1987 à 1997, Il a été un animateur de radio reconnu sous le nom de Skyman, et aussi de télévision sur France 2 où il imaginait des canulars dans l’émission Télématin. Il a aussi, pendant cette même période, collaboré à des revues de bandes dessinées comme L’Echo des savanes, en compagnie d’auteurs plus ou moins déjantés généralement situés à l’extrême-gauche.

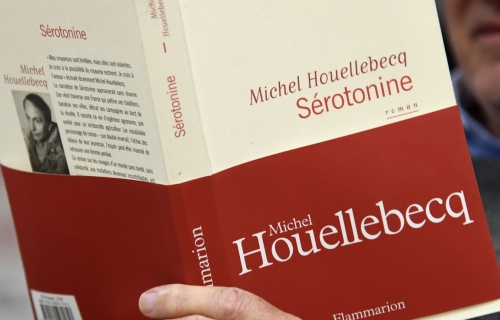

Il reprendra ses activités militantes de conférencier, de journaliste et d’auteur en 1997, quand il réintégrera le GRECE, après en avoir été séparé pendant dix ans. En ce qui concerne son activité littéraire, outre ses très nombreux articles dans diverses revues de la mouvance, il a écrit 28 livres en trois périodes, la première de 1981 à 1987, la deuxième hors circuit métapolitique de 1987 à 1997 et la troisième de 1998 à sa mort ; il sera une nouvelle fois exclu du GRECE en 2000. A cause de la parution de son livre La Colonisation de l’Europe qui aurait été jugé trop politiquement incorrect pour la direction du GRECE.

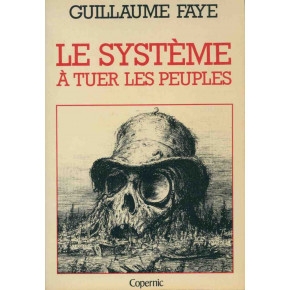

Il y a une logique chrono-logique dans le déroulement de sa production littéraire : la première période correspond à l’élaboration d’un corpus doctrinal avec son premier livre : Le Système à tuer les peuples paru en 1981 et avec un livret très intéressant qui s’appelle L’Occident comme déclin paru en 1984.

La deuxième période présente pour nous moins d’intérêt, sauf pour les passionnés de BD.

La troisième période va voir arriver un char d’assaut avec L’Archéofuturisme et les premiers pamphlets contre l’islam, comme La Colonisation de l’Europe, paru en 2000, pamphlets qui vont devenir, dans son dernier livre, La Guerre civile raciale, un réquisitoire contre l’invasion de l’Europe par les masses musulmanes du Maghreb et de l’Afrique noire sub-saharienne.

La pensée de Guillaume suivait très exactement l’évolution de la situation et il réagissait comme un général sur un champ de bataille, un général qui maîtrise l’ensemble des paramètres minute après minute et qui prend des décisions que la plupart de ses subordonnés ne comprennent pas. Ses lecteurs et ses amis ont souvent été désarçonnés par ce qu’ils croyaient être des revirements ; il n’en était rien ; Guillaume Faye se portait à l’assaut exactement là où les défenses faiblissaient et là où elles avaient besoin de renfort. Petit à petit, il a pointé très exactement – comme une « frappe chirurgicale » – le danger le plus important, écartant tous les autres et préconisant des alliances momentanées, avec Israël d’abord, ce qui n’a pas plu à tout le monde ; le danger auquel on devait prêter toute notre attention et tous nos efforts étant le Grand remplacement des populations européennes par des populations africaines manipulées et rassemblées par la religion musulmane. Dans son dernier livre paru post mortem, Guillaume ne fait plus la distinction entre islam et islamisme, il emploie donc le terme générique de « musulman ». J’ai acheté ce dernier livre à Daniel Conversano, son dernier éditeur, qui l’a tiré du coffre de sa voiture, dans l’enceinte même du cimetière où a été inhumé Guillaume. C’était encore une façon de lui rendre hommage.

La pensée de Guillaume suivait très exactement l’évolution de la situation et il réagissait comme un général sur un champ de bataille, un général qui maîtrise l’ensemble des paramètres minute après minute et qui prend des décisions que la plupart de ses subordonnés ne comprennent pas. Ses lecteurs et ses amis ont souvent été désarçonnés par ce qu’ils croyaient être des revirements ; il n’en était rien ; Guillaume Faye se portait à l’assaut exactement là où les défenses faiblissaient et là où elles avaient besoin de renfort. Petit à petit, il a pointé très exactement – comme une « frappe chirurgicale » – le danger le plus important, écartant tous les autres et préconisant des alliances momentanées, avec Israël d’abord, ce qui n’a pas plu à tout le monde ; le danger auquel on devait prêter toute notre attention et tous nos efforts étant le Grand remplacement des populations européennes par des populations africaines manipulées et rassemblées par la religion musulmane. Dans son dernier livre paru post mortem, Guillaume ne fait plus la distinction entre islam et islamisme, il emploie donc le terme générique de « musulman ». J’ai acheté ce dernier livre à Daniel Conversano, son dernier éditeur, qui l’a tiré du coffre de sa voiture, dans l’enceinte même du cimetière où a été inhumé Guillaume. C’était encore une façon de lui rendre hommage.

Les grands thèmes de l’œuvre de Guillaume Faye

On peut dégager de l’œuvre de Guillaume Faye quelques grands thèmes qu’il a portés en lui tout au long de sa vie et qu’il a répété dans presque chacun de ses livres et de ses interventions ; c’est une constante qu’on trouvera chez tous les artistes et tous les auteurs qui ont un message à transmettre ; ils vont le marteler pour que ça rentre bien dans la tête, dans les yeux, dans les oreilles. Nous avons fait nôtres la plupart de ces thèmes qui constituent l’essentiel de nos combats et de nos conversations.

La lutte contre l’uniformisation et le mondialisme :

Dans les années 70, c’était surtout les Etats-Unis qui nous imposaient leurs diktats marchands et leur société du tout-à-jeter ; le règne de la quantité s’est étendu à l’ensemble de la planète.

Le clivage gauche-droite qui subsistait encore à la fin du siècle dernier n’est plus de mise ; nous avons pris conscience que la lutte se situait entre deux pôles extrêmes : les mondialistes contre les identitaires, l’uniformisation du monde contre la préservation des terroirs, la nature contre l’artificiel, le localisme contre la zonification des espaces.

L’Europe

L’Europe

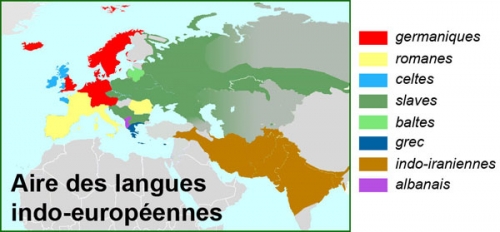

Pour Guillaume Faye, l’Europe ne représente pas seulement la puissance qui a façonné le monde par sa créativité et son génie technique. Elle est aussi, dans la diversité de ses peuples, le dernier drapeau du monde blanc. La première chose à faire et qui fut faite essentiellement par Guillaume était de bien distinguer le monde occidental, qui allait devenir celui de Big Brother qui nous prépare un gouvernement mondial, du monde de la Tradition plurimillénaire, celui des racines sans lesquelles rien ne peut croître. L’Europe, non pas celle de Bruxelles, qui n’est qu’un relais de ce mondialisme, mais la véritable Europe du sang et du sol, celle du monde blanc qui se dresse contre le monde gris des mondialistes, des marchands et des esclaves.

L’ethnomasochisme

Ce terme a été inventé par Guillaume et il est passé dans le langage, je ne dirai pas courant, mais averti, le langage de ceux qui tiennent à bien définir les comportements ; les Européens ont été soumis à une propagande intensive qui a consisté à leur enlever tout sentiment de fierté de leur propre histoire, de leur culture, de leur patrimoine, de la beauté de leurs peuples, de la beauté de leurs créations, de la beauté de leurs femmes, de la beauté de leurs paysages, de la beauté tout court. Ils se sont laissés prendre à ce piège morbide qui ne vise qu’à les faire disparaître, étape par étape, les privant de toutes leurs raisons de vivre et les acculant au suicide comme c’est le cas pour nos paysans.

La convergence des catastrophes

Guillaume Faye, à la suite du mathématicien français René Thom, établit la menace d’une convergence des catastrophes, catastrophe démographique, catastrophe épidémique, catastrophe naturelle, guerres, famines, catastrophes écologiques, suicide des peuples, etc.

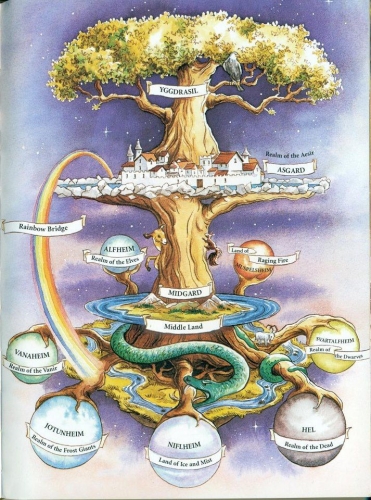

La convergence des catastrophes a des racines plus anciennes si l’on se reporte à un temps plus long, dans l’histoire sacrée des dieux plutôt que dans l’histoire récente des hommes, l’histoire profane. Toutes les anciennes traditions qui fonctionnent selon le système cyclique ont évoqué ce type de catastrophes ultimes dans le passé ; il suffit de lire Eliade, Daniélou, Evola ou Guénon pour s’en convaincre. La convergence des catastrophes, pour nos anciens, se manifeste par une conjonction de cycles astrologiques, les petits s’emboîtant dans les grands et qui, à un moment, se rejoignent tous pour arriver à leur fin pour ensuite repartir de plus belle, tout comme les aiguilles d’une montre se rejoignent sur le 6 (le 666) pour remonter ensuite toutes ensemble à des vitesses différentes. Guillaume m’avait d’ailleurs fait la surprise – je ne sais pas si c’est pour me faire plaisir – de citer un de mes articles sur le sujet dans sa Convergence des catastrophes, qu’il avait signée Corvus, mais je doute qu’il ait été vraiment convaincu par les références appuyées aux anciennes traditions de ce texte. Il s’agissait d’un article de la revue Roquefavour que j’éditais à l’époque, article datant de 2004, que j’ai repris ensuite dans mon livre La Roue et le sablier.

La convergence des catastrophes a des racines plus anciennes si l’on se reporte à un temps plus long, dans l’histoire sacrée des dieux plutôt que dans l’histoire récente des hommes, l’histoire profane. Toutes les anciennes traditions qui fonctionnent selon le système cyclique ont évoqué ce type de catastrophes ultimes dans le passé ; il suffit de lire Eliade, Daniélou, Evola ou Guénon pour s’en convaincre. La convergence des catastrophes, pour nos anciens, se manifeste par une conjonction de cycles astrologiques, les petits s’emboîtant dans les grands et qui, à un moment, se rejoignent tous pour arriver à leur fin pour ensuite repartir de plus belle, tout comme les aiguilles d’une montre se rejoignent sur le 6 (le 666) pour remonter ensuite toutes ensemble à des vitesses différentes. Guillaume m’avait d’ailleurs fait la surprise – je ne sais pas si c’est pour me faire plaisir – de citer un de mes articles sur le sujet dans sa Convergence des catastrophes, qu’il avait signée Corvus, mais je doute qu’il ait été vraiment convaincu par les références appuyées aux anciennes traditions de ce texte. Il s’agissait d’un article de la revue Roquefavour que j’éditais à l’époque, article datant de 2004, que j’ai repris ensuite dans mon livre La Roue et le sablier.

L’archéofuturisme

Pour Guillaume Faye, L’Archéofuturisme, selon ce qu’il en dit en dernière de couverture de ce livre paru en 1998, est « un livre où il est exposé que nos racines ont de l’avenir si nous savons les métamorphoser et les projeter dans le futur. » On retrouve là une image intellectuellement élaborée d’un processus naturel : tout simplement le destin d’un arbre qui a besoin de ses racines pour croître et embellir avec ses feuilles et ses fleurs, ou une référence à la première invention humaine : le concept de la roue, un monde en mouvement qui tourne autour d’un moyeu immobile, gardien des valeurs éternelles. Politiquement, on peut rapprocher le concept d’archéofuturisme de celui de conservateur-révolutionnaire, qui paraît antinomique mais qui est la condition même de la vie humaine.

A signaler que Julius Evola s’était investi en tant que peintre futuriste dans ce mouvement éponyme créé par le peintre italien Marinetti.

La technoscience

La technoscience

Guillaume prônait les vertus de la technoscience. Il est vrai que l’Europe a donné au monde la technique, sorte de prothèse artificielle visant à remplacer les attributs que les hommes ne possèdent pas (ou ne possèdent plus) naturellement. Cette frénésie technologique a envahi toutes nos sphères de vie, du plus petit électroménager jusqu’aux fusées Ariane dans des conditions qui n’ont pas toujours été guidées par le sens de la mesure qu’affectionnait Guillaume en tant que disciple de Socrate, et cette dernière affirmation est vraie, même si elle peut faire sourire à son propos. Guillaume avait élaboré une sorte de philosophie pré-transhumaniste romantique exaltant ce génie technique européen mais, ce faisant, il gommait le danger véritable du schéma transhumaniste visant à transformer l’Homme en une sorte de robot obéissant à quelques savants fous financés par quelques milliardaires tout aussi dérangés qui dirigent la planète. Tout comme il s’était fait le chantre des valeurs surhumanistes et prométhéistes qui nous ont conduits à la froide technocratie de nos élites et au gigantisme sans âme de nos villes.

L’islam

Guillaume avait donc bien désigné l’Islam, tout au long de son œuvre, comme l’ennemi prioritaire, dont il faut se débarrasser de toute urgence ; l’islam qui n’est pas seulement une religion, mais tout un système totalitaire qui règle chaque geste des croyants et qui est investi d’une mission prosélyte et de soumission de la terre entière à ses vues, ce qui définit l’islam comme une secte dangereuse.

Sa vie

Il me reste à évoquer la vie de Guillaume qui n’a pas été un long fleuve tranquille.

J’ai écrit dans un article après sa mort : « C’était un météore, brûlant sa vie de mille feux. Un météore est un corps céleste qui ne touche jamais terre et qui disparaît en se consumant. »

Issu de la grande bourgeoisie, il en rejettera très vite les « idéaux conformistes et matérialistes » comme il le disait lui-même. Dès lors, sa vie sera continuellement en butte aux jalousies et injonctions de rentrer dans le rang ; « les braves gens n’aiment pas que l’on suive une autre route qu’eux », chantait Georges Brassens. Il faut dire que Guillaume Faye n’a rien épargné aux bourgeois et aux censeurs, lesquels n’ont pas manqué de le lui rendre.

Il était diplômé de Sciences-Po et s’était engagé très vite dans la métapolitique puisqu’il n’avait que 21 ans lorsque Dominique Venner l’a appelé au sein du GRECE en 1970 ; ce qui fait qu’il n’a jamais eu la possibilité d’envisager une vie rangée dépourvue de soucis matériels que sa vive intelligence et sa culture auraient tôt fait de porter à de hautes fonctions. Mais l’a-t-il voulue, cette vie paisible ?

La seule fois où il aurait pu composer avec le Système, c’est lorsque sa brouille d’avec le GRECE en 1986 conduisit à la séparation et qu’il vécut sa parenthèse showbizz ; il n’a jamais voulu passer sous les fourches caudines de ce monde qu’il exécrait et, lorsqu’il l’a fait à cette occasion, il l’a fait de manière parodique, pour s’en moquer et se moquer de tous ceux qui participaient à sa pérennité.

D’après le long article que Robert Steuckers vient de faire paraître sur Guillaume, ceux qui l’ont appelé à s’investir corps et âme au sein du GRECE l’auraient gratifié d’un SMIC qui ne lui aurait jamais permis de s’autoriser quelque fantaisie que ce soit et je rajoute que ce n’est pas la vente de ses livres qui lui permettait de vivre décemment.

Un statut qu’il acceptait néanmoins car il lui permettait de développer en partie ses idées et d’accomplir sa mission.

Très vite, en effet, notre mouvance s’est aperçue du génie de Guillaume, de cette capacité de réinventer le monde à chaque instant, de s’adapter à ses aléas et de s’insérer harmonieusement à son mouvement perpétuel, ce qui constitue l’un des grands caractères de la culture celte dont Jean Markale avait si bien perçu les contours. Guillaume Faye était né à Angoulême, en pays charentais, pays des celtes Santons et Pétrocores, le 7 novembre 1949.

Selon Pierre Vial et Robert Steuckers, les deux ruptures successives d’avec le GRECE l’ont traumatisé -.il n’a jamais abordé le sujet avec moi, par pudeur ? – son caractère impulsif peut l’avoir amené à blesser certaines personnes dans la fougue de ses réactions, mais il en prenait conscience et il le regrettait rapidement. Il est devenu alors un garçon fragile et vulnérable qu’on aurait dû protéger et non pas accabler.

Selon Pierre Vial et Robert Steuckers, les deux ruptures successives d’avec le GRECE l’ont traumatisé -.il n’a jamais abordé le sujet avec moi, par pudeur ? – son caractère impulsif peut l’avoir amené à blesser certaines personnes dans la fougue de ses réactions, mais il en prenait conscience et il le regrettait rapidement. Il est devenu alors un garçon fragile et vulnérable qu’on aurait dû protéger et non pas accabler.

Pierre Vial écrivait à son sujet : « Quand le divorce avec certains hiérarques de la Nouvelle Droite est devenu inévitable, il a été touché au plus profond de son être et nous avons été peu nombreux à nous en rendre compte. Il y avait en lui des blessures qui ne se sont jamais refermées. Les dérives dans lesquelles il s’est noyé, ensuite, ont largement là leur explication, j’en suis persuadé. »

Et Steuckers rajoutait : « Vial, en quelques phrases parfaitement ciselées, a bien mis le doigt sur le tréfonds de la problématique psychologique qui fut celle de la personne Faye, sur cette tristesse indicible et immense, inguérissable, qui l’avait transformé lentement et fait, du garçon généreux, joyeux et curieux qu’il était, un homme qui a basculé dans la farce pendant dix ans mais a voulu en sortir, un homme vieilli avant l’âge, miné par un mal sournois. »

C’est encore Robert Steuckers qui me donnera le mot de la fin lorsqu’il faisait remarquer que Guillaume était enterré dans le cimetière du vieux village sur la commune duquel s’est installé le site du Futuroscope. Archéo et futurisme. Tout un symbole !

Guillaume restera pour ses amis le bienveillant et jovial compagnon dont ils auront essayé de préserver, tant bien que mal, la fragile mais flamboyante destinée.

Pierre-Emile Blairon

Pierre-Émile Blairon réside près d’Aix-en-Provence.

Pierre-Émile Blairon réside près d’Aix-en-Provence.

Il partage ses activités littéraires entre deux passions :

– La Provence – il anime la revue Grande Provence, il a écrit deux biographies sur deux grands provençaux : Jean Giono et Nostradamus et Le Guide secret d’Aix-en-Provence.

– Les spiritualités traditionnelles – Il anime la revue Hyperborée qui se consacre à l’histoire spirituelle du monde et à son devenir. La Roue et le sablier résume la vue-du-monde de l’auteur et des collaborateurs de la revue.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Thierry Pfister fut mon éditeur chez Albin Michel et me publia la deuxième version du Mitterrand grand initié. Ce grand professionnel était un gentilhomme et un homme de gauche convaincu qui avait rompu avec le mitterrandisme deuxième mouture des années 84-85 qui dégénérait alors en « tonton mania ». En 1989 il publia sa splendide lettre à la génération Mitterrand qui vendit 300 000 exemplaires. Les années 90 marquèrent l’agonie du mitterrandisme revenu depuis à la mode dans ce pays sans mémoire et sans histoire.

Thierry Pfister fut mon éditeur chez Albin Michel et me publia la deuxième version du Mitterrand grand initié. Ce grand professionnel était un gentilhomme et un homme de gauche convaincu qui avait rompu avec le mitterrandisme deuxième mouture des années 84-85 qui dégénérait alors en « tonton mania ». En 1989 il publia sa splendide lettre à la génération Mitterrand qui vendit 300 000 exemplaires. Les années 90 marquèrent l’agonie du mitterrandisme revenu depuis à la mode dans ce pays sans mémoire et sans histoire.

"La exaltación de la Iglesia española durante la dominación visigótica es obra de los bárbaros; pero no es obra de su voluntad, sino de su impotencia, incapaces para gobernar a un pueblo más culto, se resignaron a conservar la apariencia del poder, dejando el poder efectivo en manos más hábiles. De suerte, que el principal papel que en este punto desempeñaron los visigodos fue no desempeñar ninguno y dar, con ello, involuntariamente, ocasión para que la Iglesia se apoderara de los principales resortes de la política y fundase de hecho el estado religioso, que aún subsiste en nuestra patria, de donde se originó la metamorfosis social del cristianismo en catolicismo; esto es, en religión universal, imperante, dominadora, con posesión real de los atributos temporales de la soberanía." (Idearium Español, Agilar, Madrid, 1964; p. 11).

"La exaltación de la Iglesia española durante la dominación visigótica es obra de los bárbaros; pero no es obra de su voluntad, sino de su impotencia, incapaces para gobernar a un pueblo más culto, se resignaron a conservar la apariencia del poder, dejando el poder efectivo en manos más hábiles. De suerte, que el principal papel que en este punto desempeñaron los visigodos fue no desempeñar ninguno y dar, con ello, involuntariamente, ocasión para que la Iglesia se apoderara de los principales resortes de la política y fundase de hecho el estado religioso, que aún subsiste en nuestra patria, de donde se originó la metamorfosis social del cristianismo en catolicismo; esto es, en religión universal, imperante, dominadora, con posesión real de los atributos temporales de la soberanía." (Idearium Español, Agilar, Madrid, 1964; p. 11). La lucha por la independencia, ya fuera ante Roma, ante los moros o ante Napoleón vendría dada por un supuesto "espíritu del territorio", que Ganivet maneja al modo de una especie de constante histórica. En realidad, tal constante difusamente descrita por el ensayista, es el factor geopolítico. España, junto con Portugal, está en una península. Las dos puertas que debe guardar son los Pirineos, al norte, y el Estrecho, al sur. En las penínsulas, los pueblos invasores entran fácilmente pero a menudo salen escaldados en una lucha contra los nativos agresivamente amantes de su independencia. Sólo Roma venció verdaderamente en ésta península ibérica (así llamada, aunque en dos tercios era península celta más bien). Cuando Ganivet habla de la insularidad agresiva (hacia el exterior) de los ingleses, más bien habla de modo difuso de una talasocracia (el poder de los barcos y sobre los mares, con una escasa y torpe milicia en la propia patria). De igual manera, cuando habla de la resistencia de los continentales (franceses, alemanes), alude al factor geopolítico de la escasa entidad física de las fronteras en las potencias "telúricas". Así pues, da igual que hablemos de los hunos o de los soviéticos: las cabalgadas de aquellos, o los tanques blindados de éstos, podían allegarse al corazón de Europa, y aun hasta Lisboa, en cuestión de días. Las potencias telúricas pueden llegar muy lejos por vía terrestre de acuerdo con los medios de su época, aunque a su paso hallan bolsas de saboteadores y resistentes que siempre pueden cortar la cadena de dominación, romper eslabones de control.

La lucha por la independencia, ya fuera ante Roma, ante los moros o ante Napoleón vendría dada por un supuesto "espíritu del territorio", que Ganivet maneja al modo de una especie de constante histórica. En realidad, tal constante difusamente descrita por el ensayista, es el factor geopolítico. España, junto con Portugal, está en una península. Las dos puertas que debe guardar son los Pirineos, al norte, y el Estrecho, al sur. En las penínsulas, los pueblos invasores entran fácilmente pero a menudo salen escaldados en una lucha contra los nativos agresivamente amantes de su independencia. Sólo Roma venció verdaderamente en ésta península ibérica (así llamada, aunque en dos tercios era península celta más bien). Cuando Ganivet habla de la insularidad agresiva (hacia el exterior) de los ingleses, más bien habla de modo difuso de una talasocracia (el poder de los barcos y sobre los mares, con una escasa y torpe milicia en la propia patria). De igual manera, cuando habla de la resistencia de los continentales (franceses, alemanes), alude al factor geopolítico de la escasa entidad física de las fronteras en las potencias "telúricas". Así pues, da igual que hablemos de los hunos o de los soviéticos: las cabalgadas de aquellos, o los tanques blindados de éstos, podían allegarse al corazón de Europa, y aun hasta Lisboa, en cuestión de días. Las potencias telúricas pueden llegar muy lejos por vía terrestre de acuerdo con los medios de su época, aunque a su paso hallan bolsas de saboteadores y resistentes que siempre pueden cortar la cadena de dominación, romper eslabones de control.

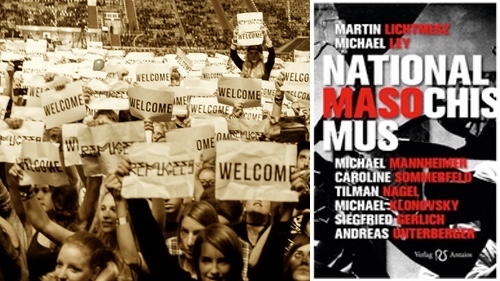

In the Platz der deutschen Einheit (German Unity Square) in Düsseldorf, someone has covered the street name with Simone de Beauvoir Platz. This is one example among many that anyone living in the Federal Republic of Germany may encounter – evidence of the hatred of their country which some Germans feel. Evidence is all around. Now a book has been published stating and stressing this tendency of Germans to despise their birthright and identity.

In the Platz der deutschen Einheit (German Unity Square) in Düsseldorf, someone has covered the street name with Simone de Beauvoir Platz. This is one example among many that anyone living in the Federal Republic of Germany may encounter – evidence of the hatred of their country which some Germans feel. Evidence is all around. Now a book has been published stating and stressing this tendency of Germans to despise their birthright and identity. The first essay by Lichtmesz (photo) is an overview of the notion of national masochism. In medical terms, masochism is the desire to obtain and/or the pleasure obtained from pain administered either by oneself or by others to oneself. The earliest use of the expression “national masochism,” according to Lichtmesz, comes from the actor Gustav Gründgens – ironic, if true – since the central figure in Klaus Mann’s Mephisto, Hendrik Höfgen, is a thinly-disguised Gründgens, and that book is a case study in German shame. The novel is about an actor who makes his peace with National Socialism for the sake of his professional career, drawing a parallel between Gründgens working in Germany after 1933 and Faust selling his soul to Mephistopheles for twenty-four years of youth, pleasure, and success. However, this theme had already been appropriated with vastly more skill, talent, and subtlety in his father Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus. Klaus Mann worked for American propaganda during the war and committed suicide in 1949. He himself might serve as an exemplary case of German self-loathing.

The first essay by Lichtmesz (photo) is an overview of the notion of national masochism. In medical terms, masochism is the desire to obtain and/or the pleasure obtained from pain administered either by oneself or by others to oneself. The earliest use of the expression “national masochism,” according to Lichtmesz, comes from the actor Gustav Gründgens – ironic, if true – since the central figure in Klaus Mann’s Mephisto, Hendrik Höfgen, is a thinly-disguised Gründgens, and that book is a case study in German shame. The novel is about an actor who makes his peace with National Socialism for the sake of his professional career, drawing a parallel between Gründgens working in Germany after 1933 and Faust selling his soul to Mephistopheles for twenty-four years of youth, pleasure, and success. However, this theme had already been appropriated with vastly more skill, talent, and subtlety in his father Thomas Mann’s Doktor Faustus. Klaus Mann worked for American propaganda during the war and committed suicide in 1949. He himself might serve as an exemplary case of German self-loathing.

Klonovsky’s writing style is not unlike that of Tarki and other journalists at the British Spectator: intelligent, angry, snide. He recounts a program about Hans Michael Frank and an interview with his son, Niklas Frank. Niklas Frank takes masochism to new heights by explaining that everywhere he goes, he carries a picture with him depicting his father hanging from the gallows at Nuremberg. That way he can always reassure himself that Daddy “is well and truly dead” (p. 123). This must have been a repeat of an old program, since I remember a German girlfriend of mine being appalled by Niklas Frank when she watched the program on television in the late 1980s.

Klonovsky’s writing style is not unlike that of Tarki and other journalists at the British Spectator: intelligent, angry, snide. He recounts a program about Hans Michael Frank and an interview with his son, Niklas Frank. Niklas Frank takes masochism to new heights by explaining that everywhere he goes, he carries a picture with him depicting his father hanging from the gallows at Nuremberg. That way he can always reassure himself that Daddy “is well and truly dead” (p. 123). This must have been a repeat of an old program, since I remember a German girlfriend of mine being appalled by Niklas Frank when she watched the program on television in the late 1980s.

Koestler was a pivotal figure in the post-war generation that rejected communism as “the God that failed”— the title of a celebrated book of essays,

Koestler was a pivotal figure in the post-war generation that rejected communism as “the God that failed”— the title of a celebrated book of essays,

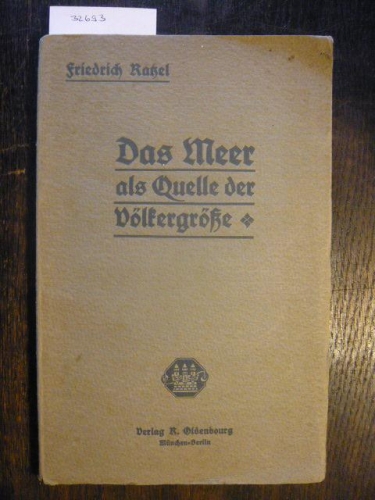

It is clearly visible that from such an organic approach, Ratzel understood territorial expansion to be a natural, living process, similar to the growth of living organisms.

It is clearly visible that from such an organic approach, Ratzel understood territorial expansion to be a natural, living process, similar to the growth of living organisms.

But all of these disciplines, which Kjellen cultivated in parallel with geopolitics, did not receive more widespread recognition aside from the term “Geopolitics,” which steadily became established in quite varied circles.

But all of these disciplines, which Kjellen cultivated in parallel with geopolitics, did not receive more widespread recognition aside from the term “Geopolitics,” which steadily became established in quite varied circles. In his book “Mitteleuropa” (1915), Naumann gave a geopolitical diagnosis that matches exactly with the concepts of Rudolf Kjellen. From Naumann’s point of view, to withstand competition from such organized geopolitical formations like England (and its colonies), the USA, and Russia, the peoples inhabiting Central Europe should unify and organize in new integrative, political-economic ways in this space. The axis of this space, would of course, naturally, be Germany.

In his book “Mitteleuropa” (1915), Naumann gave a geopolitical diagnosis that matches exactly with the concepts of Rudolf Kjellen. From Naumann’s point of view, to withstand competition from such organized geopolitical formations like England (and its colonies), the USA, and Russia, the peoples inhabiting Central Europe should unify and organize in new integrative, political-economic ways in this space. The axis of this space, would of course, naturally, be Germany.

2/

2/