Si l’on estime, comme Spengler, que « la politique n’est qu’un substitut à la guerre utilisant des armes plus intellectuelles » (1), appliquer la grille de raisonnement propre à la stratégie militaire au combat politique peut s’avérer fécond.

Les grands principes en matière de stratégie militaire, sont au nombre de cinq. Le 1er, la concentration des forces, consiste à frapper avec le maximum de puissance l’ennemi, en un point choisi comme étant le plus faible de son dispositif, pour obtenir soit une percée, soit sa destruction totale. En effet, seule l’attaque du fort au faible est payante, l’attaque du fort au fort ne conduisant qu’au carnage, comme l’Histoire l’a montré. Tel fut le cas de Gettysburg en 1863, qui coûta 23 000 hommes aux Nordistes et 28 000 aux Confédérés, soit un tiers de leurs troupes. Même résultat tragique pour l’offensive anglaise de la Somme, en juillet 1916, qui entraîna des pertes ahurissantes, la résistance allemande n’ayant pas été entamée par les tirs d’artillerie préalables : 19 240 morts le 1er jour, et plus de 600 000 jusqu’en novembre ! A noter que la concentration des forces implique la maximisation de la puissance de feu : il faut impérativement concentrer son feu pour s’assurer la destruction de l’ennemi, plutôt que de le disperser sur plusieurs cibles…

2ème grande règle, l’économie des forces, qui consiste à privilégier un objectif principal sans s’attarder sur des objectifs secondaires. La défense cherche à disperser l’attaquant, alors que ce dernier doit se concentrer sur son objectif.

3ème principe, la surprise, l’un des éléments les plus importants de la stratégie militaire. On distingue deux niveaux : la surprise stratégique, qui consiste à cacher son plan de campagne, ses objectifs et ses manœuvres; la surprise tactique qui consiste à dissimuler la marche ou la position de ses armées, un nouveau matériel ou une supériorité technique. Pour profiter pleinement de la surprise, il importe que celle-ci débouche sur un avantage décisif : on revient à la concentration des forces, car il faut à tout prix « tirer pour tuer ».

4 ème règle de base à respecter : l’unité de commandement, qui garantit la rapidité de réaction et l’intégrité du plan initialement mis en œuvre. Elle doit être entendue comme unité de pensée, que se soit entre les armes (Terre, Air, Mer) ou entre les conceptions stratégiques. Mais ce principe est rarement atteint, même au sein d’une armée nationale, encore moins entre des commandements alliés de plusieurs nations. Les Américains ont toujours su unifier leur direction, que ce soit pendant la guerre de Sécession, celle du Pacifique, ou en Europe avec Eisenhower. Le commandement interallié de Foch, nommé commandant en chef du Front de l’Ouest en mars 1918 est un autre exemple de commandement unifié voulu par les Alliés. A l’inverse, les Allemands ont, au cours des deux guerres mondiales, totalement échoué à mettre en place cette unité de commandement, que ce soit au niveau des stratégies nationales ou des armes (Wehrmacht, Luftwaffe, Waffen SS).

Dernier élément, l’initiative des opérations : c’est le but essentiel de la manœuvre, qui découle de la maîtrise des autres principes stratégiques. Le camp qui dispose de l’initiative bénéficie d’un avantage moral considérable. Mais celui qui déclenche les hostilités n’est pas forcément celui qui engage les opérations : en 1939, si les Alliés surprennent Hitler en lui déclarant la guerre, ils restent sur leurs positions, abandonnant toute initiative stratégique au führer.

UN EXEMPLE DE MAITRISE DES PRINCIPES STRATÉGIQUES : AUSTERLITZ

La bataille d’Austerlitz, menée de main de maître par Napoléon, est le meilleur exemple d’une stratégie réussie.

Apprenant la formation de la 3ème coalition, Napoléon exécute un retournement complet de son armée massée à Boulogne, qu’il envoie à Ulm battre l’Autriche, s’emparant de l’initiative stratégique. Face aux Russes et aux restes de l’armée autrichienne, il étudie soigneusement la carte de Moravie et sélectionne le site d’Austerlitz, imposant le champ de bataille aux Coalisés.

Le commandement est unitaire chez les Français. Clausewitz, fortement influencé par Napoléon, retiendra le principe du « généralissime ». A l’inverse, le conseil de guerre coalisé est bicéphale (Autriche-Russie), et le plan finalement adopté est un compromis boiteux entre les deux alliés.

Le plan de bataille français est simple et expliqué la veille aux soldats par Napoléon : il consiste à attirer l’aile gauche coalisée dans un piège en faisant reculer l’aile droite française, afin de prendre le plateau de Pratzen avec le gros des forces et, à partir de cette brèche, effectuer une manœuvre en tenaille. Au contraire, le plan des Coalisés est compliqué, exposé lors d’un interminable conseil de guerre où le maréchal Koutouzov s’endort ! Pis : les ordres sont donnés aux officiers russes au dernier moment et en allemand !

Les Français pratiquent la concentration des forces avec comme objectif principal le plateau de Pratzen. Les Coalisés se donnent plusieurs objectifs, d’où une dispersion de leurs forces qui sont battues en détail. Résultat : l’emploi des grands principes stratégiques offre sa plus grande victoire à Napoléon.

LA BATAILLE DE FRANCE DE MAI 40

Autre exemple parlant, la campagne de France de 1940. L’avantage de l’initiative stratégique est perdu par les Alliés lors de l’invasion allemande de la Pologne, et ils ne la retrouveront plus.

L’état-major allemand fait preuve de flexibilité en changeant son plan sous l’impulsion d’Hitler. La réédition du plan Schlieffen de 1914 initialement prévu (poussée massive vers le nord de la France à travers la Belgique) est abandonné. Alors que le plan français prévoit une avance du gros des forces alliées pour contrer l’avance ennemie, les allemands attaquent la Belgique et la Hollande tandis que leurs blindés percent à Sedan, dans les Ardennes, un endroit considéré par la doctrine française comme infranchissable par les chars (cours d’eau plus massif forestier). Les Allemands exploitent à fond la surprise.

Sur l’objectif principal, Hitler concentre 7 divisions blindées, face à 7 divisions d’infanterie et 2 divisions de cavalerie légère françaises. Le principe de l’attaque du fort contre le faible est respecté, les Allemands cherchant à réaliser la percée à un point précis, le Schwerponkt, point de rupture, en l’occurrence à Sedan. Grâce à la mobilité de leurs divisions blindées, ils foncent vers la Mer du Nord et isolent le gros de l’armée alliée en Belgique par un « coup de faux ».

PRINCIPES STRATÉGIQUES ET COMBAT POLITIQUE

Ces principes stratégiques ne visant qu’un but, la victoire, il semble donc pertinent de les appliquer aussi sur un plan politique.

Incontournables, la concentration et l’économie des forces, qui consistent à frapper avec le maximum de force militante le point faible de l’adversaire politique. En 1968, Alain Robert créera le GUD en partant du constat qu’un noyau dur de militants concentrés sur un bastion universitaire valait mieux que des centaines d’adhérents éparpillés (cf Occident). Le nid de résistance, véritable Nanterre à l’envers, ne pouvait qu’être Assas, plus favorable sociologiquement. Si l’on excepte Jean-Marie Le Pen, candidat gyrovague (Paris, Auray, Marseille, Nice), tous les dirigeants du FN se sont efforcés de constituer un fief électoral inexpugnable : le couple Stirbois à Dreux, Bruno Mégret à Vitrolles, Marine Le Pen à Hénin-Beaumont. A chaque fois, l’on retrouve les mêmes ingrédients qui assurent la victoire finale : concentration des forces vives du parti sur un point faible de l’ennemi – en l’occurrence, une mairie socialiste gangrénée par l’insécurité, l’immigration et les scandales -, et au final percée électorale décisive qui ouvre une brèche dans le mur du silence politico-médiatique.

Sur le plan idéologique aussi, il s’agit de frapper du fort au faible, et sur un nombre limité d’ «objectifs ». Pour percer, un mouvement politique doit se limiter à quelques idées simples et porteuses. L’émergence du FN dans les années 80 s’explique ainsi par « la règle des trois I » : Immigration, Insécurité, Impôts. Lorsque Le Pen reniera ce triptyque, en 2007, il obtiendra son pire score présidentiel. En revanche, l’attaque du faible au fort, c’est-à-dire sur des thèmes totalement verrouillés par le Système – antisémitisme, révisionnisme – déclenche immédiatement un violent tir de barrage médiatique et relève du grand suicide politique… Lancer l’offensive sur ces forteresses puissamment défendues par 50 ans de terrorisme intellectuel, c’est faire bien peu de cas de l’élément primordial de toute stratégie : la surprise.

Autre principe à ne pas ignorer, l’unité de commandement. L’expérience a montré la supériorité du principe du chef (qui a parlé de « führerprinzip » ?…) sur une direction collégiale. Initiative nationale, mensuel du Parti des forces nouvelles, présentait deux photos, l’une de Le Pen, l’autre du bureau politique du PFN, ainsi sous-titrées : « Face à face : Président (…) et Bureau Politique. Deux conceptions de l’action » (2). L’histoire a tranché entre un leader charismatique et une direction multiple et, au final, acéphale. Alors que Le Pen persévéra dans la dénonciation du giscardisme et de la « fausse droite », les jeunes gens du PFN multiplieront les stratégies les plus variées, passant d’un soutien à VGE en 1974, à un ralliement à Chirac en 1977, puis au lancement de l’Eurodroite avec le MSI néo-fasciste !

Ces principes stratégiques théorisés par les auteurs classiques suivent ce que l’historien de l’Antiquité gréco-latine Victor D. Hanson a appelé Le modèle occidental de la guerre (3), qui repose entièrement sur la recherche de la bataille décisive, chère à Clausewitz – bataille qui doit conduire à l’écrasement de l’adversaire -, ignorant d’autres formes de guerre, comme la guerre assymétrique.

Edouard Rix, Réfléchir & Agir, automne 2010, n°36.

NOTES

(1) O. Spengler, L’Homme et la technique, Gallimard, 1969, p. 120.

(2) Initiative nationale, novembre 1977, n°22, pp. 18-19.

(3) Victor D. Hanson, Le modèle occidental de la guerre, Les Belles Lettres, 2001, 298 p.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Es war kurz vor Weihnachten. US-Präsident Obama durfte seinen letzten Auftritt als »starker« US-Präsident absolvieren, bevor mit Jahreswechsel Senat und Repräsentantenhaus in neuer Zusammensetzung zusammentreten, die ihn vollends zur lahmen Ente degradiert.

Es war kurz vor Weihnachten. US-Präsident Obama durfte seinen letzten Auftritt als »starker« US-Präsident absolvieren, bevor mit Jahreswechsel Senat und Repräsentantenhaus in neuer Zusammensetzung zusammentreten, die ihn vollends zur lahmen Ente degradiert.

Na 249 dagen tegen dezelfde nieuwscarrousel aan te moeten kijken, ontwikkelt een mens zo onderhand een filter om zin van onzin te scheiden. Zo waren er de afgelopen week twee berichten die door mijn persoonlijke crisisfilter raakten:

Na 249 dagen tegen dezelfde nieuwscarrousel aan te moeten kijken, ontwikkelt een mens zo onderhand een filter om zin van onzin te scheiden. Zo waren er de afgelopen week twee berichten die door mijn persoonlijke crisisfilter raakten:

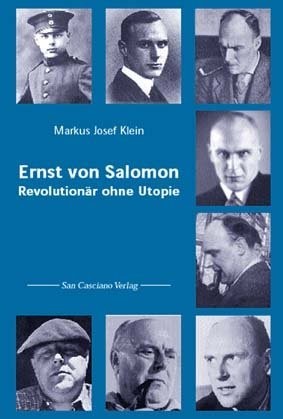

Assez récemment, les éditions Bartillat ont eu l’excellente idée de rééditer Ernst von Salomon, auteur culte, certes, mais seulement pour un petit nombre d’adeptes. Et ses livres majeurs n’étaient plus disponibles depuis plusieurs années. Jean Mabire notait, dans son Que lire ? de 1996, pour le regretter, que « la mort d’Ernst von Salomon, en 1972 n’avait « pas fait grand bruit, et, aujourd’hui, on parle fort peu de cet écrivain singulier ».

Assez récemment, les éditions Bartillat ont eu l’excellente idée de rééditer Ernst von Salomon, auteur culte, certes, mais seulement pour un petit nombre d’adeptes. Et ses livres majeurs n’étaient plus disponibles depuis plusieurs années. Jean Mabire notait, dans son Que lire ? de 1996, pour le regretter, que « la mort d’Ernst von Salomon, en 1972 n’avait « pas fait grand bruit, et, aujourd’hui, on parle fort peu de cet écrivain singulier ». Le roman La Ville parait en 1932 (en 1933 en France). C’est le portrait d’un agitateur vagabondant dans le radicalisme absolu, c’est encore une sorte d’autobiographie, autour de ses engagements « paysans ».

Le roman La Ville parait en 1932 (en 1933 en France). C’est le portrait d’un agitateur vagabondant dans le radicalisme absolu, c’est encore une sorte d’autobiographie, autour de ses engagements « paysans ».

James O’Meara on Henry James & H. P. Lovecraft

The Lesson of the Monster; or, The Great, Good Thing on the Doorstep

James J. O'Meara

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

We’ve been very pleased by the response to our essay “The Eldritch Evola,” which was not only picked up by Greg Johnson (whose own Confessions of a Reluctant Hater is out and essential reading) for his estimable website Counter-Currents, but even managed to lurch upwards and lay a terrible, green claw on the bottom rung of the “Top Ten Most Visited Posts” there in January.

Coincidentally, we’ve been delving into the newer Penguin Portable Henry James , being a sucker for the Portables in general, and especially those in which a wise editor goes to the trouble of cutting apart a life’s work of legendary unreadability and stitching together a coherent, or at least assimilable, narrative, for the convenience of us amateurs, from Malcolm Cowley’s first, the legendary Portable Faulkner

, being a sucker for the Portables in general, and especially those in which a wise editor goes to the trouble of cutting apart a life’s work of legendary unreadability and stitching together a coherent, or at least assimilable, narrative, for the convenience of us amateurs, from Malcolm Cowley’s first, the legendary Portable Faulkner that rescued “Count No-Account,” as he was known among his homies, to the recent Portable Jack Kerouac

that rescued “Count No-Account,” as he was known among his homies, to the recent Portable Jack Kerouac epic saga recounted by Ann Charters.

epic saga recounted by Ann Charters.

The “new” Portable Henry James attempts something of the sort (as opposed to the older one, which was your basic collection) by recognizing the impossibility of even including large excerpts from the “major” works, and instead gives us some of the basic short works (Daisy Miller, Turn of the Screw, “The Jolly Corner,” etc.) and then hundreds of pages of travel pieces, criticism, letters, even parodies and tributes, as well a a list of bizarre names (Cockster? Dickwinter?) and above all, in a section called “Definition and Description,” little vignettes, often only a paragraph, exemplifying the Jamesian precision, a sort of anthology of epiphanies, the great memorable moments from “An Absolutely Unmarried Woman” to “An American Corrected on What Constitutes ‘the Self’” from the novels, and similar nonfiction moments from James’ travels, such as “The Individual Jew” to “New York Power” to “American Teeth” and “The Absence of Penetralia.”

The latter section in particular is part of a defense which the editor seems to feel needs to be mounted in his Introduction, of the Jamesian “difficult” prose style (as are the collection of tributes, including the surprising, to me at least, Ezra Pound).

I bring these two together because I could not help but think of ol’ Lovecraft himself in this context. Is Lovecraft not the corresponding Master of Bad Prose? As Edmund Wilson once quipped, the only horror in Lovecraft’s corpus was the author’s “bad taste and bad art.”

One can only imagine what James would have thought of Lovecraft, although we know, from excerpts here on Baudelaire and Hawthorne, what he thought of Poe, and more importantly, of those who were fans: “to take [Poe] with more than a certain degree of seriousness is to lack seriousness one’s self. An enthusiasm for Poe is the mark of a decidedly primitive stage of reflection”; James may even have based the poet in “The Aspern Papers,” a meditation on America’s cultural wasteland, on Poe. However, his distaste is somewhat ambiguous, as compared with Baudelaire, Poe is “vastly the greater charlatan of the two, as well as the greater genius.”

For all his “better” taste and talent for reflection, it’s little realized today, as well, that James’s reputation went into steep decline after his death, and was only revived in the fifties, as part of a general reconsideration of 19th century American writers, like Melville, so that even James could be said to have, like Lovecraft, been forgotten after death except for a small coterie that eventually stage managed a revival years later.

Are James and Lovecraft as different as all that? One can’t help but notice, from the list above, that a surprising amount of James’s work, and among it the best, is in the ‘weird’ mode, and in precisely the same “long short story” form, “the dear, the blessed nouvelle,” in which Lovecraft himself hit his stride for his best and most famous work. (Both “Daisy Miller” and “At the Mountains of Madness” suffered the same fate: rejection by editors solely put off by their ‘excessive’ length for magazine publication.) The nouvelle of course accommodated James’ legendary prolixity.

The editor, John Auchard, puts James’s prolixity into the context of the 19th century ‘loss of faith.’ Art was intended to take the place of religion, principally by replacing the lost “next world” by an increased concentration on the minutia of this one. Experience might be finite, but it could still “burn with a hard, gem-like flame” as Pater famously counseled.

That counsel, of course, took place in the first, then self-suppressed, then retained afterword to his The Renaissance . René Guénon has in various places diagnosed this as the essential fraud of the Renaissance, the exchange of a vertical path to transcendence for a horizontal dissipation and dispersal among finite trivialities, usually hoked-up as “man discovered the vast extent of the world and himself,” blah blah blah. As Guénon points out, it’s a fool’s bargain, as the finite, no matter how extensive and intricate, is, compared to the infinite, precisely nothing.

. René Guénon has in various places diagnosed this as the essential fraud of the Renaissance, the exchange of a vertical path to transcendence for a horizontal dissipation and dispersal among finite trivialities, usually hoked-up as “man discovered the vast extent of the world and himself,” blah blah blah. As Guénon points out, it’s a fool’s bargain, as the finite, no matter how extensive and intricate, is, compared to the infinite, precisely nothing.

Baron Evola, on the other hand, distinguishes several types of Man, and is willing to let some of them find their fulfillment in such worldliness. It is, however, unworthy of one type of Man: Aryan Man. See the chapter “Determination of the Vocations” in his The Doctrine of Awakening: The Attainment of Self-Mastery According to the Earliest Buddhist Texts .

.

So the nouvelle length accumulation of detail and precision of judgment, in James, is intended to produce some kind of this-worldly ersatz transcendence. Was this perhaps the same intent in Lovecraft, the use of the nouvelle length tale to pile up detail until the mind breaks?

Lovecraft of course was also a thorough-going post-Renaissance materialist, a Cartesian mechanist with the best of them; when he finally got “The Call of Cthulhu” published, he advised his editor that:

Now all my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large. One must forget that such things as organic life, good and evil, love and hate, and all such local attributes of a negligible and temporary race called mankind, have any existence at all.

But as John Miller notes, this is exactly what is needed to produce the Lovecraft Effect:

That’s nihilism, of course, and we’re free to reject it. But there’s nothing creepier or more terrifying than the possibility that our lives are exercises in meaninglessness.

What is there to choose, between the unrealized but metaphysically certain nothingness of the Jamesian finite detail, and the all-too-obvious nothingness of Lovecraft’s worldview?

What separates James from Lovecraft and Evola is, along the lines of our previous effort, is precisely what T. S. Eliot, in praise of James (the essay is in the Portable too): “He has a mind so fine no idea could penetrate it.” Praise, note, and contrasted with the French, “the Home of Ideas,” and such Englishmen, or I guess pseudo-Englishmen, as Chesterton, “whose brain swarms with ideas” but cannot think, meaning, one gathers, stand apart with skepticism. One notes the Anglican Eliot seeming to flinch back, like a good English gentleman, from those dirty, unruly Frenchmen like Guénon, and such Englishmen who, like Chesterton, went “too far” and went and “turned Catholic” out of their love of “smells and bells.”

What Evola and Lovecraft had was precisely an Idea, the idea of Tradition; in Lovecraft’s case, a made-up, fictional one, but designed to have the same effect. But that’s the issue: when is Tradition only made up? For Evola and Guénon, the mind of Traditional Man is indeed not “fine” enough to evade penetration by the Idea; he is open to the transcendent, vertical dimension, which is realized in Intellectual Intuition.

I’ve suggested elsewhere that Intellectual Intuition, or what Evola calls his “Traditional Method” is usefully compared with what Spengler called, speaking of his own method, “physiognomic tact.” I wrote: “A couple years ago I found a passage in one of the few books on Spengler in English, by H. Stuart Hughes, where it seemed like he was actually giving a good explication of Guénon’s metaphysical (vs. systematic philosophy) method. I think it could apply to Evola’s method as well” Hughes writes:

Spengler rejected the whole idea of logical analysis. Such “systematic” practices apply only in the natural sciences. To penetrate below the surface of history, to understand at least partially the mysterious substructure of the past, a new method — that of “physiognomic tact”— is required.

This new method, “which few people can really master,” means “instinctively to see through the movement of events. It is what unites the born statesman and the true historian, despite all opposition between theory and practice.” [It takes from Goethe and Nietzsche] the injunction to “sense” the reality of human events rather than dissect them. In this new orientation, the historian ceases to be a scientist and becomes a poet. He gives up the fruitless quest for systematic understanding. . . . “The more historically men tried to think, the more they forgot that in this domain they ought not to think.” They failed to observe the most elementary rule of historical investigation: respect for the mystery of human destiny.

So causality/science, destiny/history. Rather than chains of reasoning and “facts” the historian employs his “tact” [really, a kind of Paterian "taste"] to “see” the big picture: how facts are composed into a destiny. Rather than compelling assent, the historian’s words are used to bring about a shared intuition.

I suppose Guénon and Co. would bristle at being lumped in with “poets” but I think the general point is helpful in understanding the “epistemology” of what Guénon is doing: not objective (but empty) fact-gathering but not merely aesthetic and “subjective” either, since metaphysically “seeing” the deeper connection can be “induced” by words and thus “shared.”

What Guénon, Evola, and Spengler seek to do deliberately, what Lovecraft did fictionally or even accidentally, what James’s mind was “too fine” to do at all, is to not see mere facts, or see a lot of them, or even see them very very intently, but to see through them and thus acquire metaphysical insight, and, through the method of obsessive accumulation of detail, share that insight by inducing it in others.

To do this one must be “penetrated” by the Idea, Guénon’s metaphysics, Evola’s historical cycles, Lovecraft’s Mythos, and allow it be be generated within oneself. Only then can you see.

Speaking of “penetration,” one does note James’s obsession with “penetralia”; also one recalls the remarkable way Schuon brings out how in Christianity the Word is brought by Gabriel to Mary, who in mediaeval paintings is often shown with a stream of words penetrating her ear, thus conceiving virginally, while in Islam, Gabriel brings the Word to Muhammad, who recites (gives birth to) the Koran. Itself a wonderful example of the Traditional Method: moving freely among the material elements of various traditions to weave a pattern that re-creates an Idea in the mind of the listener. Do you see how Christianity and Islam relate? Do you see?

Finally, we should note that Lovecraft, for his own sake, did get in a preemptive shot at James:

In The Turn of the Screw, Henry James triumphs over his inevitable pomposity and prolixity sufficiently well to create a truly potent air of sinister menace; depicting the hideous influence of two dead and evil servants, Peter Quint and the governess, Miss Jessel, over a small boy and girl who had been under their care. James is perhaps too diffuse, too unctuously urbane, and too much addicted to subtleties of speech to realise fully all the wild and devastating horror in his situations; but for all that there is a rare and mounting tide of fright, culminating in the death of the little boy, which gives the novelette a permanent place in its special class.– Supernatural Horror in Literature, Chapter VIII.

Source: http://jamesjomeara.blogspot.com/