The Legionary Doctrine (also called Legionarism) refers to the philosophy and beliefs presented by the Legion of Michael the Archangel (also commonly known as the Iron Guard), the Romanian Christian Nationalist organization founded by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, who is the key figure in the creation of its doctrine. It is necessary to clarify what the members of the Legionary Movement taught and believed due to many misconceptions arising from ignorance and outright deception, as well as the mistaken assumption that the Legionary Movement was largely an imitation of Fascism or National Socialism.

The Legionary Doctrine (also called Legionarism) refers to the philosophy and beliefs presented by the Legion of Michael the Archangel (also commonly known as the Iron Guard), the Romanian Christian Nationalist organization founded by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, who is the key figure in the creation of its doctrine. It is necessary to clarify what the members of the Legionary Movement taught and believed due to many misconceptions arising from ignorance and outright deception, as well as the mistaken assumption that the Legionary Movement was largely an imitation of Fascism or National Socialism.

Precursors

In 1878 and 1879, after Romania had won its independence from the Ottoman Empire, the new nation wanted to be recognized by other European powers. The Romanians could not achieve this without signing the Treaty of Berlin, which forced them to grant citizenship to Jews, a hostile and alien people on Romanian land. Although the treaty was signed, certain significant cultural and political figures in Romanian history spoke out against the Jews in order to warn their nation that the Jews were culturally and economically harmful. These men’s works from 1879 were significant intellectual sources of the Legionary Movement’s Christian nationalism and awareness of the Jewish Problem. The most influential of them were the following:

- Vasile Conta (1845–1882) – philosopher and politician

- Vasile Alecsandri (1821–1890) – diplomat and politician

- Mihail Kogălniceanu (1817–1891) – statesman and historian

- Mihail Eminescu (1850–1889) – famous poet and journalist

- Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu (1838–1907) – historian and philologist

- Costache Negri (1812–1876) – politician

- A. D. Xenopol (1847–1820) – historian and economist

Other intellectuals, who lived in the early 20th century and saw the birth and growth of the Legionary Movement, also educated Codreanu and other Legionaries about the Jewish Problem, national mysticism, Orthodox mysticism, and economic practices. These men were:

- A. C. Cuza (1857–1947) – politician and professor of law and political economy

- Nicolae Iorga (1871–1940) – historian, professor of history, and politician

- Nicolae Paulescu (1869–1931) – physiologist, professor of medicine, and philosopher

- Ion Gavanescul (1859–1949) – professor of pedagogy

- Nichifor Crainic (1889–1972) – professor of theology, theologian, and philosopher

To avoid misconceptions, it must be noted that it is not implied here that the precursors of the Legionary Movement agreed with Legionary doctrine on every point. For example, some of them had different political attitudes; the Legion rejected republicanism while precursors such as Eminescu supported the democratic system.

Anti-Semitism and the Jewish Problem

Some people today who follow the Legionary doctrine or admire the Legionaries assert that the Legion was not anti-Semitic but only appeared so because of a Jewish problem in Romania. One of the major reasons for which they object to the term “anti-Semitic” is because of a certain way by which that term is defined by Jews and philo-semites. Such groups define it as an irrational hatred of all Jews, and in that case the Legionaries were not truly anti-Semitic, since their hostility to the Jews was not irrational nor were they enemies with every Jew (it has been pointed out that the Legion had a few Jewish supporters, although it should be remembered that the majority of Jews were enemies of the Legion).

However, in the late 19th century and early 20th century the term anti-Semite was simply defined as one who had hostility towards Jews and opposed their presence in one’s nation. This is how Cuza and other precursors, Corneliu Codreanu, and his successor Horia Sima defined it, and they all had no qualms about calling themselves anti-Semitic. Codreanu freely stated in his major book For My Legionaries about his visit to Germany that “I had many discussions with the students at Berlin in 1922, who are certainly Hitlerites today, and I am proud to have been their teacher in anti-Semitism, exporting to them the truths I learned in Iasi.”

It should be noted, however, that while Codreanu had no problem associating with the German National Socialist movement (although he also correctly insisted that his Legion was entirely independent of National Socialism), Horia Sima objected to any connection between the two after World War II. In his 1967 book Istoria Mişcarii Legionare (History of the Legionary Movement) Sima wrote:

The Legionary Movement, since its first manifestation, was the object of all sorts of slander. One of the most common allegations by its countless internal and external enemies was that the Legion was a “branch of Nazism.” Such statements can be made as a result of ignorance or bad faith. The anti-Semitism of the Legionary Movement has nothing in common with German anti-Semitism. By taking a stand against the Jewish danger, a danger extremely active and menacing in Romania, Corneliu Codreanu was simply continuing an almost century old Romanian tradition.

It should also be emphasized that Legionary hostility to the Jews as an ethnic group was actually rational, based not only on the scientific studies of the Jewish problem by intellectuals such as Cuza, Paulescu, Iorga, Xenopol, et al. but also on real experiences and observations made by many average Romanians. The Jewish problem was a vivid reality. Both intellectual observation as well as common observation showed the people beyond any doubt that the majority of Jews not only lived parasitically off of the labor of Romanian workers by their ownership of many companies or financial activity, but also posed a threat to Romanian culture and tradition, which they were damaging through their influence on mass media and certain government policies.

It is also worth noting that while Codreanu was first and foremost concerned with the Romanian condition, he believed that an alliance between nations needed to be made to solve the Jewish problem internationally. This is made clear by a statement in For My Legionaries:

There, I shared with my comrades an old thought of mine, that of going to Germany to continue my studies in political economy while at the same time trying to realize my intention of carrying our ideas and beliefs abroad. We realized very well, on the basis of our studies, that the Jewish problem had an international character and the reaction therefore should have an international scope; that a total solution of this problem could not be reached except through action by all Christian nations awakened to the consciousness of the Jewish menace.

The solution to the Jewish problem was not to kill the Jews, as many dishonest people accuse Codreanu of wanting, but to expel the Jews from Romania. This plan for deportation is plainly stated in The Nest Leader’s Manual, where he wrote “Romania for Romanians and Palestine for the Jews.”

Economics and Labor: Anti-Communism and Anti-Capitalism

When Codreanu first went to the University of Iasi in 1919, years before he created the Legion, he discovered that most of the city and university were heavily influenced by Communist political campaigns. The Romanian workers were experiencing terrible working conditions and had very low wages, so they had been drawn to Communism by Marxist propagandists. Professors and students at the University were also largely converted to Communism, and Communist student meetings attacked the Romanian army, the Orthodox Church, the monarchy, and other aspects of traditional Romanian life. It was this situation that drove Codreanu into a heroic fight against Communism, finally leading a conservative group to completely crushing the Communist movement. Codreanu, being a traditionalist, insisted on defending faith in God, nationalism, the Crown, and private property.

On the other hand, Codreanu also believed in fighting the Capitalist system, which he realized was an inherently exploitive system, which allowed corporations to exploit millions of workers. In 1919, when forming the program of “National Christian Socialism,” he stated that “It is not enough to defeat Communism. We must also fight for the rights of the workers. They have a right to bread and a fight to honor. We must fight against the oligarchic parties, creating national workers organizations which can gain their rights within the framework of the state and not against the state.”

Later in 1935 he announced the creation of a new system which he hoped would be adopted by the nation as a whole once the Legionary Movement took power: “Legionary commerce signifies a new phase in the history of commerce which has been stained by the Jewish spirit. It is called: Christian commerce — based on the love of people and not on robbing them; commerce based on honor.” Essentially Codreanu was a Third Position socialist, supporting private property but at the same time opposing the materialistic and money-centered system of capitalism. Another important point of Codreanu’s ideas for Romania is that labor is something in which everyone must be involved in. Laziness was a trait that should be treated as a highly negative vice. All Legionaries in some way did some kind of physical work, often to help lower class Romanians in their own labor and problems. Codreanu wrote: “The law of work: Work! Work every day. Put your heart into it. Let your reward be, not gain, but the satisfaction that you have laid another brick to the building of the Legion and the flourishing of Romania.”

One issue which has often been brought up against Codreanu is the fact that he associates both Capitalism and Communism with the Jews, as both of them were dominated by Jews in Romania. He wrote, connecting Jewish Capitalists and Jewish Communists, “But industrial workers were vertiginously sliding toward Communism, being systematically fed the cult of these ideas by the Jewish press, and generally by the entire Jewry of the cities. Every Jew, merchant, intellectual, or banker-capitalist, in his radius of activity, was an agent of these anti-Romanian revolutionary ideas.” Some of his opponents have objected to this connection by arguing that it is ridiculous to say that Jewish company owners and bankers would support Communists, who supposedly would destroy them upon a revolution, since they would want to eliminate the capitalists. But it should be remembered that not all of the bourgeoisie were exterminated in Communist revolutions across Europe. Sometimes, members of the bourgeoisie who supported Communism before a revolution, who were oftentimes Jews, would be given a place in the Communist system once the revolution was achieved.

Nation and Land

The Legionaries believed that nations were not merely products of history and geography, but were created by God Himself and had a spiritual component to them. Codreanu wrote in For My Legionaries, adopting the teachings of Nichifor Crainic:

If Christian mysticism and its goal, ecstasy, is the contact of man with god through a “leap from human nature to divine nature,” national mysticism is nothing other than the contact of man and crowds with the soul of their people through the leap which these forces make from the world of personal and material interests into the outer world of nation. Not through the mind, since this any historian can do, but by living with their soul.

A nation was also inseparable from the land on which it developed, to which the people grew a spiritual connection with over time. Codreanu wrote of the Romanian people:

We were born in the mist of time on this land together with the oaks and fir trees. We are bound to it not only by the bread and existence it furnishes us as we toil on it, but also by all the bones of our ancestors who sleep in its ground. All our parents are here. All our memories, all our war-like glory, all our history here, in this land lies buried. . . . Here . . . sleep the Romanians fallen there in battles, nobles and peasants, as numerous as the leaves and blades of grass . . . everywhere Romanian blood flowed like rivers. In the middle of the night, in difficult times for our people, we hear the call of the Romanian soil urging us to battle. . . . We are bound to this land by millions of tombs and millions of unseen threads that only our soul feels . . .

Finally, it must be noted that Codreanu also believed that every nation has a mission to fulfill in the world and therefore that only the nations which betray their mission, given to them by God, will disappear from the earth. “To us Romanians, to our people, as to any other people in the world, God has given a mission, a historic destiny,” wrote Codreanu, “The first law that a person must follow is that of going on the path of this destiny, accomplishing its entrusted mission. Our people has never laid down its arms or deserted its mission, no matter how difficult or lengthy was its Golgotha Way.” The aim of a nation, or its destiny in the world of spirit, was that it does not simply live in the world but that it aims for resurrection through the teachings of Christ. “There will come a time when all the peoples of the earth shall be resurrected, with all their dead and all their kings and emperors, each people having its place before God’s throne. This final moment . . . is the noblest and most sublime one toward which a people can rise.” It was for this ideal that the Legion fought tirelessly against all obstacles, corrupt politicians, and alien peoples such as the Jews which insisted on feeding off the Romanian people and land.

Religion and Culture

One aim of the Legionary Movement was the preservation and regeneration of Romanian culture and customs. They knew that culture was the expression of national genius, its products the unique creations of the members of a specific nation. Culture could have international influence, but it was always national in origin. Therefore, the Liberal-Capitalist position that different ethnic groups should be allowed to freely move into another group’s nation, interfering with that nation’s culture and development by their presence and influence, was incredibly wrong. Each ethnic group has its own soul and produces and crystallizes its own form and style of culture. For example, a Romanian cultural image could not be created from German essence any more than a German cultural image could be created from Romanian essence.

Furthermore, religion was an important aspect in a people’s culture, oftentimes the origin of many customs and traditions. The Legionaries believed that Christianity was not only a significant part of their culture, but also that it was the religion which represented divine truth. This is why in order to join the Legion of Michael the Archangel one had to be a Christian and could not be of another religion or an atheist. With these principles clear, the Legion therefore aimed for a Romanian nation made up of only ethnic Romanians and only Christians.

With this in mind, it becomes clear why Codreanu and many other Romanians felt that the Jewish presence in their nation was so threatening. The Jews became influential in economics, finance, newspapers, cinema, and even politics. Through this they even became powerful in the field of culture, slowly changing Romanian customs and Romanian thinking, making it more related to that of the Jews. Codreanu, as concerned about the problem as people such as Cuza and Gavanescul, commented:

Is it not frightening, that we, the Romanian people, no longer can produce fruit? That we do not have a Romanian culture of our own, of our people, of our blood, to shine in the world side by side with that of other peoples? That we be condemned today to present ourselves before the world with products of Jewish essence?” and “Not only will the Jews be incapable of creating Romanian culture, but they will falsify the one we have in order to serve it to us poisoned.

Race

The reality of race was accepted by most Legionaries, and Codreanu wrote of the importance of keeping a nation racially cohesive. In For My Legionaries, Codreanu quoted Conta’s racial separatist arguments, which formed the basis of his own attitudes on race, and even compared them to the German National Socialist view. He wrote: “Consider the attitude our great Vasile Conta held in the Chamber in 1879. Fifty years earlier the Romanian philosopher demonstrated with unshakeable scientific arguments, framed in a system of impeccable logic, the soundness of racial truths that must lie at the foundation of the national state; a theory adopted fifty years later by the same Berlin which had imposed on us the granting of civil rights to the Jews in 1879.”

However, it should be noted that at least a few Legionaries did not agree that race was important. Ion Mota, in 1935 when he met with the NSDAP in Germany, criticized the National Socialists by telling them that “Racism is the most vulgar form of materialism. Peoples are not different by flesh, blood or color of skin. They are different by their spirit, i.e. by their creations, culture and religion.” Of course, Mota’s attitude is unlikely to have been dominant among the Legion, since Codreanu was the founder of the ideas the majority of its members shared. It is also notable that Horia Sima, in his works on Legionary beliefs, agreed with Codreanu that race is real and important. However, Sima disagreed with connecting Romanian racial views with German racialism, censuring the followers of Hitler by asserting that their worldview misused racialism, making it too absolute and materialistic.

The New Man

The Legionary Movement aimed to create a New Man (Omul Nou), to transform the entire nation through Legionary education by transforming each individual into a person of quality. The New Man would be more honest and moral, more intelligent, industrious, courageous, willing to sacrifice, and completely free of materialism. His view of the world would be centered around spirituality, service to his nation, and love of his fellow countrymen. This new and improved form of human being would transform history, setting the foundations of a new era never before seen in Romanian history.

Codreanu wrote:

We shall create an atmosphere, a moral medium in which the heroic man can be born and can grow. This medium must be isolated from the rest of the world by the highest possible spiritual fortifications. It must be defended from all the dangerous winds of cowardice, corruption, licentiousness, and of all the passions which entomb nations and murder individuals. Once the Legionary will have developed in such a milieu . . . he shall be sent into the world. . . . He will be an example; will turn others into Legionaries. And people, in search of better days, will follow him . . . will make a force which will fight and will win.

Therefore, a spiritual revolution would create the basis for a political revolution, since without the New Man no political program could achieve any lasting accomplishment.

Politics

Romania ’s government was that of a constitutional monarchy, thus the nation’s government was considered a democracy. Corneliu Codreanu was a member of the Romanian parliament two times, and his experiences with democratic politics led him to firmly conclude that the democratic system, although claiming to represent the will of the people, rarely ever achieved its goal of representation. In fact, he felt that it did just the opposite. In For My Legionaries, he listed out some major objections he had to the system and the way it worked (the following is a paraphrase of his points):

- Democracy destroys the unity of the people since it creates factionalism.

- Democracy turns millions of Jews (and other alien groups) into Romanian citizens, thus carelessly destroying the ancient ethnic make-up of a nation.

- Democracy is incapable of enduring effort and responsibility because by design it inherently leads to an unending change in leadership over short period of time. A leader or party works to improve the nation with a specific plan, but only rules for a few years before being replaced by a new one with a new plan, who largely if not completely disregard the old one. Thus little is achieved and the nation is harmed.

- Democracy lacks authority since it does not give a leader the power he needs to accomplish his duties to the nation and turns him into a slave of his selfish political supporters.

- Democracy is manipulated by financiers and bankers, since most parties are dependent on their funding and are thus influenced by them.

- Democracy does not guarantee the election of virtuous leaders, since the majority of politicians are either demagogues or corrupt, and the masses of common people usually are not capable or knowledgeable enough to elect good men. Codreanu rhetorically remarked about the idea of the masses choosing its elite, “Why then do soldiers not choose the best general?”

Therefore, Codreanu aimed for a new form of government, rejecting both republicanism and dictatorship. In this new system the leaders would not inherit power through heredity, nor would they be elected as in a republic, but rather they would be selected. Thus, selection and not election is the method of choosing a new elite. Natural leaders, demonstrating bravery and skill, would rise up through Legionary ranks, and the old elite would be responsible for choosing the new elite. The concept of the New Man is important to Codreanu’s system of leadership, because only by the establishment of the New Man would the right leaders rise and become the leaders of the nation. The elite would be founded on the principles Codreanu himself laid out: “a) Purity of soul. b) Capacity of work and creativity. c) Bravery. d) Tough living and permanent warring against difficulties facing the nation. e) Poverty, namely voluntary renunciation of amassing a fortune. f) Faith in God. g) Love.”

This new system of government which Codreanu aimed to establish would be authoritarian, but it would not be totalitarian. He described it in this way: “He (the leader) does not do what he wants, he does what he has to do. And he is guided, not by individual interests, nor by collective ones, but instead by the interests of the eternal nation, to the consciousness of which the people have attained. In the framework of these interests and only in their framework, personal interests as well as collective ones find the highest degree of normal satisfaction.”

An important point in the Legionary political system is that the Legion recognized three entities: “1) The individual. 2) The present national collectivity, that is, the totality of all the individuals of the same nation, living in a state at a given moment. 3) The nation, that historical entity whose life extends over centuries, its roots imbedded deep in the mists of time, and with an infinite future.”

Each of these entities had their own rights in a hierarchical sense. Republicanism recognized only the rights of the individual, but the Legionary Movement recognized the rights of all three. The nation was the most important entity, and thus the rights of the national collectivity were subordinate to it, and finally the rights of the individual were subordinate to the rights of the national collectivity. The destructive individualism of “democracy” infringed on the rights of the national collectivity and the rights of the nation, since it ignored the rights of those two entities and placed that of the individual above all.

With these facts in mind, it becomes clear that to accuse the Legionary Movement of wishing to establish a tyrannical dictatorship or of being “Fascist” is nothing more than mindless or deceitful propaganda against the movement.

Martyrdom

“The Legionary embraces death,” wrote Codreanu, “for his blood will serve to mold the cement of Legionary Romania.” Throughout the struggles and intense persecutions it faced, the Legionary Movement produced many martyrs, two of the most often referenced being Ion Mota and Vasile Marin, who died in 1937 helping Franco fight against Marxist Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. Other martyrs of the Legion include Sterie Ciumetti, Nicoleta Nicolescu, Lucia Grecu, and Victor Dragomirescu among hundreds of others. Finally, in 1938, Corneliu Codreanu himself became a martyr after Armand Calinescu, acting outside of the law, had him murdered. Martyrs were often honored in songs all Legionaries sang and in Legionary rituals, when their names were announced in the roll call, all Legionaries attending spoke “present!” They believed that the souls of Romanian dead would still be present with them in their battles.

Violence

Along with martyrdom, in which death was received, there was an occasional violence committed by Legionaries against their enemies. Codreanu originally intended that the Legionary Movement would be nonviolent, but the unusually ruthless and cruel manner in which their enemies treated them created conditions in which violence was inevitable. When their political opponents physically attacked them, the Legionaries often struck back. In certain select cases, certain top enemies of the Legion were assassinated. There are three most prominent examples:

- In 1933, the government of I. G. Duca had banned the Legion to keep it from participating in elections, arrested 18,000 Legionaries, and tortured and murdered several others. On December 29–30 of that year, the Legionaries Nicolae Constantinescu, Doro Belimace, and Ion Caranica (who are often referred to as the Nicadori) assassinated Duca in revenge.

- In 1934, Mihail Stelescu, a member of the Legion, was investigated by top Legionaries and discovered to have had planned to betray the Legion and create his own group and was therefore expelled. Stelescu then created the group in 1935, calling it Cruciada Romanismuliu (“The Crusade of Romanianism”), and slandered Codreanu in its newspaper. There is also evidence that Stelescu was plotting to assassinate Codreanu and that, after contacting top political figures, he received government support for this plan. In this situation, ten Legionaries later called the Decemviri (“The Ten Men”) shot him.

- In November of 1938, Armand Calinescu had the military police illegally murder Codreanu (who was earlier that year imprisoned for ten years for unproven charges at unfair trials), the Nicadori, and the Decemviri. On September 21, 1939 nine Legionaries referred to as the Rasbunatorii (“The Avengers”) assassinated Calinescu. After they turned themselves in, they were tortured and executed without trial. These nine men were: Miti Dumitrescu, Cezar Popescu, Traian Popescu, Nelu Moldoveanu, Ion Ionescu, Ion Vasiliu, Marin Stanciulescu, Isaia Ovidiu, and Gheorghe Paraschivescu.

One may object to such actions on the part of the Legionaries, asserting that they are thus taking part in un-Christian actions. However, to correctly understand this, one must remember that throughout the history of Christianity there were many people who had committed violent acts or killed for the sake of their religion. Certain crusader knights who had killed huge numbers of people were even sainted. Clearly it is nothing new for Christian zealots to engage in combat against their enemies. Some would argue that because Christ taught people to “love their enemies” that therefore Codreanu was openly violating Christian teaching. But it is not quite so clear.

It should be remembered that in the original Greek and Latin the phrase “love your enemies” (Matthew 5:44; Luke 6:27) referred specifically to private enemy, not public enemy or national enemy (who could therefore be hated). This is why Codreanu said to the Legionaries:

Forgive those who struck you for personal reasons. Those who have tortured you for your faith in the Romanian people, you will not forgive. Do not confuse the Christian right and duty of forgiving those who wronged you, with the right and duty of our people to punish those who have betrayed it and assumed for themselves the responsibility to oppose its destiny. Do not forget that the swords you have put on belong to the nation. You carry them in her name. In her name you will use them for punishment-unforgiving and unmerciful. Thus and only thus, will you be preparing a healthy future for this nation.

These are the facts which need to be remembered in order to properly understand why Codreanu and the Legionaries did what they did. Otherwise, a proper historical study cannot be done.

Bibliography

Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, For My Legionaries, third edition, translated and edited by Dr. Dimitrie Gazdaru (York, S.C., USA: Liberty Bell Publications, 2003).

Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, The Nest Leader’s Manual (USA: CZC Books, 2005).

Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, The Prison Notes (USA: Reconquista Press, 2011).

Radu Mihai Crisan, Eminescu Interzis: Gândirea Politică (Forbidden Eminescu: Political Thought) (Bucharest: Criterion Publishing, 2008).

Radu Mihai Crisan, Istoria Interzisă (Forbidden History) (Bucharest: Editura Tibo, 2008).

Alexander E. Ronnett and Faust Bradescu, “The Legionary Movement in Romania,” The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 193–228.

Alexander E. Ronnett, Romanian Nationalism: The Legionary Movement (Chicago: Romanian-American National Congress, 1995).

Horia Sima, Doctrina legionară (Legionary Doctrine) (Madrid: Editura Mişcării Legionare, 1980).

Horia Sima, Era Libertaţii – Statul naţional-Legionar, vol. 1 (It was Freedom – National Legionary State, vol. 1) (Madrid: Editura “Miscarii Legionare, 1982).

Horia Sima, Era Libertaţii – Statul naţional-Legionar, vol. 2 (It was Freedom – National Legionary State, vol. 2) (Madrid: Editura Miscãrii Legionare, 1990).

Horia Sima, Istoria Mişcarii Legionare (History of the Legionary Movement) (Timişoara: Editura Gordian, 1994).

Horia Sima, Guvernul National Român de la Viena (Romanian National Government in Vienna) (Madrid: Editura Miscarii Legionare, 1993).

Horia Sima, The History of the Legionary Movement (Liss, England: Legionary Press, 1995).

Horia Sima, Menirea Nationalismului (The Meaning of Nationalism) (Salamanca: Editura Asociaţiei Culturale Hispano-Române, 1951).

Horia Sima, Prizonieri ai Puterilor Axei (Prisoners of the Axis Powers) (Madrid: Editura Miscarii Legionare, 1990).

Horia Sima, Sfârşitul unei domnii sângeroase (The End of a Bloody Reign) (Madrid: Editura Miscarii Legionare, 1977).

Horia Sima, The History of the Legionary Movement (Liss, England: Legionary Press, 1995).

Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007).

Michael Sturdza, The Suicide of Europe: Memoirs of Prince Michael Sturdza, Former Foreign Minister of Rumania (Boston & Los Angeles: Western Islands Publishers, 1968).

Francis Puyalte et Saphia Azzedine ont un point commun : leur livre comporte une épigraphe extraite de Bagatelles pour un massacre. Thème identique de surcroît : « C’est toujours le toc, le factice, la camelote ignoble et creuse qui en impose aux foules, le mensonge toujours ! jamais l’authentique... » (Puyalte) et « Les peuples toujours idolâtrent la merde, que ce soit en musique, en peinture, en phrases, à la guerre ou sur les tréteaux. L’imposture est la déesse des foules. » (Azzedine). La comparaison s’arrête là. Car, pour le reste, l’univers décrit par la beurette (« Guerre des boutons version al-Qaida », dixit un critique) ¹ et celui de Puyalte sont bien différents. Journaliste à Paris-Jour, puis à L’Aurore et au Figaro, Francis Puyalte est aujourd’hui à la retraite. Cela lui confère la liberté de dénoncer sans fard ce qu’il nomme l’inquisition médiatique, et ce à travers des exemples concrets. De l’affaire de Bruay-en-Artois au procès d’Omar Raddad, Puyalte montre comment la presse d’aujourd’hui fabrique des innocents ou des coupables et surtout comment elle parvient à imposer ce qu’il convient de penser. Jamais auparavant un journaliste n’avait aussi franchement révélé ce qui se passe dans les coulisses du quatrième pouvoir. Dans ce livre, il ne traite donc pas d’une autre de ses passions – Céline – qui lui a notamment permis de rencontrer Lucette dont il a recueilli les propos dans deux articles mémorables ². Dans Bagatelles, le mot « imposture » est l’un de ceux qui revient le plus souvent. C’est précisément ce que dénonce Puyalte dans cet ouvrage salué par un (autre) esprit libre : « Une incroyable liberté de ton, de pensée, de critique et de démolition. Un pamphlet vif, argumenté, salubre et dévastateur sur le journalisme, ses dérives, ses conforts intellectuels, ses paresses et ses préjugés. (…) Ces dysfonctionnements et vices du journalisme ont parfois été dénoncés mais jamais avec cette verve... » ³. Savoureux aussi, le premier chapitre consacré à ses débuts dans le journalisme. Il rappelle – ce n’est pas un mince compliment – les pages analogues de François Brigneau dans Mon après-guerre. Voyez plutôt : « Le lecteur ? J’apprendrai vite que ce n’est pas le principal souci de la rédaction en chef, qui planche, dès la fin de la matinée, sur la manchette de la Une. Ce qui importe, c’est un titre accrocheur, vendeur, selon le terme si souvent entendu. Il est vrai qu’un journal est fait pour être vendu, même lorsque l’actualité est pauvre. Alors, faute d’un événement d’intérêt, on va en gonfler un autre qui n’en a aucun. Au départ, il faisait hausser les épaules. À l’arrivée, il fait la manchette. Drôle de situation pour le reporter. À lui la débrouille et non la bredouille. ». On aura compris que c’est un livre décapant, très célinien dans la démarche (« Tout dire ou bien se taire »). Raison pour laquelle, on s’en doute, Francis Puyalte ne sera pas invité dans les médias. Peu importe, son livre existe et fera date.

Francis Puyalte et Saphia Azzedine ont un point commun : leur livre comporte une épigraphe extraite de Bagatelles pour un massacre. Thème identique de surcroît : « C’est toujours le toc, le factice, la camelote ignoble et creuse qui en impose aux foules, le mensonge toujours ! jamais l’authentique... » (Puyalte) et « Les peuples toujours idolâtrent la merde, que ce soit en musique, en peinture, en phrases, à la guerre ou sur les tréteaux. L’imposture est la déesse des foules. » (Azzedine). La comparaison s’arrête là. Car, pour le reste, l’univers décrit par la beurette (« Guerre des boutons version al-Qaida », dixit un critique) ¹ et celui de Puyalte sont bien différents. Journaliste à Paris-Jour, puis à L’Aurore et au Figaro, Francis Puyalte est aujourd’hui à la retraite. Cela lui confère la liberté de dénoncer sans fard ce qu’il nomme l’inquisition médiatique, et ce à travers des exemples concrets. De l’affaire de Bruay-en-Artois au procès d’Omar Raddad, Puyalte montre comment la presse d’aujourd’hui fabrique des innocents ou des coupables et surtout comment elle parvient à imposer ce qu’il convient de penser. Jamais auparavant un journaliste n’avait aussi franchement révélé ce qui se passe dans les coulisses du quatrième pouvoir. Dans ce livre, il ne traite donc pas d’une autre de ses passions – Céline – qui lui a notamment permis de rencontrer Lucette dont il a recueilli les propos dans deux articles mémorables ². Dans Bagatelles, le mot « imposture » est l’un de ceux qui revient le plus souvent. C’est précisément ce que dénonce Puyalte dans cet ouvrage salué par un (autre) esprit libre : « Une incroyable liberté de ton, de pensée, de critique et de démolition. Un pamphlet vif, argumenté, salubre et dévastateur sur le journalisme, ses dérives, ses conforts intellectuels, ses paresses et ses préjugés. (…) Ces dysfonctionnements et vices du journalisme ont parfois été dénoncés mais jamais avec cette verve... » ³. Savoureux aussi, le premier chapitre consacré à ses débuts dans le journalisme. Il rappelle – ce n’est pas un mince compliment – les pages analogues de François Brigneau dans Mon après-guerre. Voyez plutôt : « Le lecteur ? J’apprendrai vite que ce n’est pas le principal souci de la rédaction en chef, qui planche, dès la fin de la matinée, sur la manchette de la Une. Ce qui importe, c’est un titre accrocheur, vendeur, selon le terme si souvent entendu. Il est vrai qu’un journal est fait pour être vendu, même lorsque l’actualité est pauvre. Alors, faute d’un événement d’intérêt, on va en gonfler un autre qui n’en a aucun. Au départ, il faisait hausser les épaules. À l’arrivée, il fait la manchette. Drôle de situation pour le reporter. À lui la débrouille et non la bredouille. ». On aura compris que c’est un livre décapant, très célinien dans la démarche (« Tout dire ou bien se taire »). Raison pour laquelle, on s’en doute, Francis Puyalte ne sera pas invité dans les médias. Peu importe, son livre existe et fera date.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

L’arrestation spectaculaire de l’ancien chef de l’état-major de l’armée turque, Ilker Basbug (photo), et la plainte déposée contre l’ancien chef de la direction militaire du coup d’Etat de 1980 et ex-président de la République, Kenan Evren, a crée l’événement et éveillé toutes les attentions, bien au-delà des frontières turques. Cette arrestation et cette mise en examen ont montré clairement combien profondes sont les césures qui déchirent la société et le monde politique dans ce pays, qui est une pierre angulaire de l’OTAN. Le motif qui se profile derrière ces manoeuvres politico-judiciaires est à rechercher dans le fameux procès, qui est en cours depuis 2007, contre le réseau secret “Ergenekon”, auquel les organes du gouvernement d’Erdogan et le procureur général reprochent d’entretenir, par le biais de la terreur, des peurs et des émotions dans la population pour justifier un nouveau putsch militaire.

L’arrestation spectaculaire de l’ancien chef de l’état-major de l’armée turque, Ilker Basbug (photo), et la plainte déposée contre l’ancien chef de la direction militaire du coup d’Etat de 1980 et ex-président de la République, Kenan Evren, a crée l’événement et éveillé toutes les attentions, bien au-delà des frontières turques. Cette arrestation et cette mise en examen ont montré clairement combien profondes sont les césures qui déchirent la société et le monde politique dans ce pays, qui est une pierre angulaire de l’OTAN. Le motif qui se profile derrière ces manoeuvres politico-judiciaires est à rechercher dans le fameux procès, qui est en cours depuis 2007, contre le réseau secret “Ergenekon”, auquel les organes du gouvernement d’Erdogan et le procureur général reprochent d’entretenir, par le biais de la terreur, des peurs et des émotions dans la population pour justifier un nouveau putsch militaire.

Chesterton disait que le sens commun ne consistait pas à répéter ce que tout le monde piaille, de ci de là, sans ton ni accent, dans l’ignorance béate de ce qui nous entoure. Mais qu’il consistait à retrouver ce que tous savent (ou ce que tous, nous savons entre nous), mais que personne ne se risque à déclarer, la plupart du temps, par autocensure individuelle et auto-répression personnelle.

Chesterton disait que le sens commun ne consistait pas à répéter ce que tout le monde piaille, de ci de là, sans ton ni accent, dans l’ignorance béate de ce qui nous entoure. Mais qu’il consistait à retrouver ce que tous savent (ou ce que tous, nous savons entre nous), mais que personne ne se risque à déclarer, la plupart du temps, par autocensure individuelle et auto-répression personnelle.

PSL: Que les Frères Musulmans allaient constituer le premier parti d’Egypte, ça, nous le savions dès le départ. Ce qui m’a surpris, c’est la force des mouvements salafistes; elle s’explique partiellement par deux faits: d’abord, les petites gens, surtout dans les campagnes, adhèrent à une forme rigoriste de l’islam; ensuite, les salafistes reçoivent appui et financement de l’Arabie Saoudite.

PSL: Que les Frères Musulmans allaient constituer le premier parti d’Egypte, ça, nous le savions dès le départ. Ce qui m’a surpris, c’est la force des mouvements salafistes; elle s’explique partiellement par deux faits: d’abord, les petites gens, surtout dans les campagnes, adhèrent à une forme rigoriste de l’islam; ensuite, les salafistes reçoivent appui et financement de l’Arabie Saoudite.

Angus Robertson est chef de la fraction SNP. Sur le site internet de son parti, il commente les assertions intrusives de Cameron: “Il est clair que la balourdise de David Cameron, à vouloir sauver la vieille union, s’est avérée contre-productive dès que les Ecossais ont entendu parler des possibilités que leur offrirait l’indépendance. Toutes les démarches qu’ont entreprises les partis anti-indépendantistes depuis l’immixtion désordonnée de Cameron n’ont suscité qu’un désir général d’indépendance et l’ampleur de ce désir montre que nous pouvons être confiants d’obtenir un ‘oui’ lors du référendum prévu pour l’automne de l’année 2014”. Le soutien à l’indépendantisme se perçoit également dans l’augmentation du nombre des membres du SNP: “Personne ne se soucie autant du développement de l’Ecosse que ceux qui y vivent. C’est pourquoi ce ceux eux, et non d’autres, qui doivent recevoir le pouvoir de décision”.

Angus Robertson est chef de la fraction SNP. Sur le site internet de son parti, il commente les assertions intrusives de Cameron: “Il est clair que la balourdise de David Cameron, à vouloir sauver la vieille union, s’est avérée contre-productive dès que les Ecossais ont entendu parler des possibilités que leur offrirait l’indépendance. Toutes les démarches qu’ont entreprises les partis anti-indépendantistes depuis l’immixtion désordonnée de Cameron n’ont suscité qu’un désir général d’indépendance et l’ampleur de ce désir montre que nous pouvons être confiants d’obtenir un ‘oui’ lors du référendum prévu pour l’automne de l’année 2014”. Le soutien à l’indépendantisme se perçoit également dans l’augmentation du nombre des membres du SNP: “Personne ne se soucie autant du développement de l’Ecosse que ceux qui y vivent. C’est pourquoi ce ceux eux, et non d’autres, qui doivent recevoir le pouvoir de décision”.

Otto Strasser nasce il 10 settembre 1897 in una famiglia di funzionari bavaresi. Suo fratello Gregor (che sarà uno dei capi del partito nazista ed un serio concorrente di Hitler) è maggiore di cinque anni. L’uno e l’altro beneficiano di solidi antecedenti familiari: il padre Peter, che si interessa di economia politica e di storia, pubblica sotto lo pseudonimo di Paaul Weger un opuscolo intitolato Das neue Wesen, nel quale si pronuncia per un socialismo cristiano e sociale. Secondo Paul Strasser, fratello di Gregor e Otto, “in questo opuscolo si trova già abbozzato l’insieme del programma culturale e politico di Gregor e Otto, cioè un socialismo cristiano sociale, che è indicato come la soluzione alle contraddizioni e alle mancanze nate dalla malattia liberale, capitalista e internazionale dei nostri tempi.” Quando scoppia la Grande Guerra, Otto Strasser interrompe i suoi studi di diritto e di economia per arruolarsi il 2 agosto 1914 (è il più giovane volontario di Baviera). Il suo brillante comportamento al fronte gli varrà la Croce di Ferro di prima classe e la proposta per l’ Ordine Militare di Max-Joseph. Prima della smobilitazione nell’aprile/maggio 1919, partecipa con il fratello Gregor, nel Corpo Franco von Epp, all’assalto contro la Repubblica sovietica di Baviera. Ritornato alla vita civile Otto riprende i suoi studi a Berlino nel 1919 e fonda la “Associazione universitaria dei veterani socialdemocratici”.

Otto Strasser nasce il 10 settembre 1897 in una famiglia di funzionari bavaresi. Suo fratello Gregor (che sarà uno dei capi del partito nazista ed un serio concorrente di Hitler) è maggiore di cinque anni. L’uno e l’altro beneficiano di solidi antecedenti familiari: il padre Peter, che si interessa di economia politica e di storia, pubblica sotto lo pseudonimo di Paaul Weger un opuscolo intitolato Das neue Wesen, nel quale si pronuncia per un socialismo cristiano e sociale. Secondo Paul Strasser, fratello di Gregor e Otto, “in questo opuscolo si trova già abbozzato l’insieme del programma culturale e politico di Gregor e Otto, cioè un socialismo cristiano sociale, che è indicato come la soluzione alle contraddizioni e alle mancanze nate dalla malattia liberale, capitalista e internazionale dei nostri tempi.” Quando scoppia la Grande Guerra, Otto Strasser interrompe i suoi studi di diritto e di economia per arruolarsi il 2 agosto 1914 (è il più giovane volontario di Baviera). Il suo brillante comportamento al fronte gli varrà la Croce di Ferro di prima classe e la proposta per l’ Ordine Militare di Max-Joseph. Prima della smobilitazione nell’aprile/maggio 1919, partecipa con il fratello Gregor, nel Corpo Franco von Epp, all’assalto contro la Repubblica sovietica di Baviera. Ritornato alla vita civile Otto riprende i suoi studi a Berlino nel 1919 e fonda la “Associazione universitaria dei veterani socialdemocratici”.

O “mito”, como a “representação de uma batalha”, surge espontaneamente e exerce um efeito mobilizador sobre as massas, incute-lhes uma “fé” e torna-as capazes de actos heróicos, funda uma nova ética: essas são as pedras angulares do pensamento de Georges Sorel (1847-1922). Este teórico político, pelos seus artigos e pelos seus livros, publicados antes da primeira guerra mundial, exerceu uma influência perturbante tanto sobre os socialistas como sobre os nacionalistas.

O “mito”, como a “representação de uma batalha”, surge espontaneamente e exerce um efeito mobilizador sobre as massas, incute-lhes uma “fé” e torna-as capazes de actos heróicos, funda uma nova ética: essas são as pedras angulares do pensamento de Georges Sorel (1847-1922). Este teórico político, pelos seus artigos e pelos seus livros, publicados antes da primeira guerra mundial, exerceu uma influência perturbante tanto sobre os socialistas como sobre os nacionalistas.

The Legionary Doctrine (also called Legionarism) refers to the philosophy and beliefs presented by the Legion of Michael the Archangel (also commonly known as the Iron Guard), the Romanian Christian Nationalist organization founded by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, who is the key figure in the creation of its doctrine. It is necessary to clarify what the members of the Legionary Movement taught and believed due to many misconceptions arising from ignorance and outright deception, as well as the mistaken assumption that the Legionary Movement was largely an imitation of Fascism or National Socialism.

The Legionary Doctrine (also called Legionarism) refers to the philosophy and beliefs presented by the Legion of Michael the Archangel (also commonly known as the Iron Guard), the Romanian Christian Nationalist organization founded by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, who is the key figure in the creation of its doctrine. It is necessary to clarify what the members of the Legionary Movement taught and believed due to many misconceptions arising from ignorance and outright deception, as well as the mistaken assumption that the Legionary Movement was largely an imitation of Fascism or National Socialism.

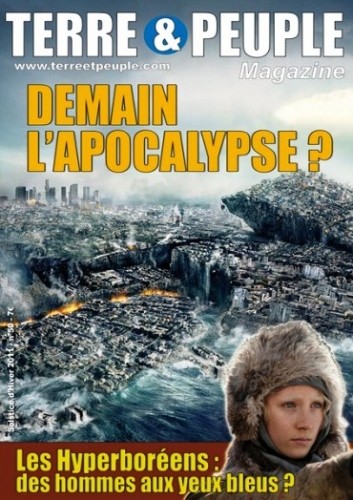

Le numéro 50 de TP Magazine est centré autour d’un dossier bien fourni sur le thème ‘Demain l’apocalypse ?’

Le numéro 50 de TP Magazine est centré autour d’un dossier bien fourni sur le thème ‘Demain l’apocalypse ?’