By Murray N. Rothbard

Mises.org & http://www.lewrockwell.com

[This article is excerpted from An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought, vol. 1, Economic Thought Before Adam Smith.]

Communist Zealots: the Anabaptists

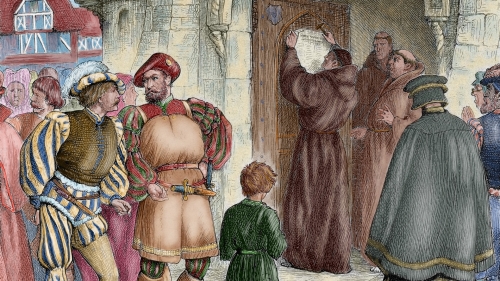

Sometimes Martin Luther must have felt that he had loosed the whirlwind, even opened the gates of Hell. Shortly after Luther launched the Reformation, various Anabaptist sects appeared and spread throughout Germany. The Anabaptists believed in predestination of the elect, but they also believed, in contrast to Luther, that they knew infallibly who the elect were: i.e., themselves. The sign of that election was in an emotional, mystical conversion process, that of being “born again,” baptized in the Holy Spirit. Such baptism must be adult and not among infants; more to the point, it meant that only the elect are to be sect members who obey the multifarious rules and creeds of the Church. The idea of the sect, in contrast to Catholicism, Lutheranism, or Calvinism, was not comprehensive Church membership in the society. The sect was to be distinctly separate, for the elect only.

Given that creed, there were two ways that Anabaptism could and did go. Most Anabaptists, like the Mennonites or Amish, became virtual anarchists. They tried to separate themselves as much as possible from a necessarily sinful state and society, and engaged in nonviolent resistance to the state’s decrees.

The other route, taken by another wing of Anabaptists, was to try to seize power in the state and to shape up the majority by extreme coercion: in short, ultratheocracy. As Monsignor Knox incisively points out, even when Calvin established a theocracy in Geneva, it had to pale beside one which might be established by a prophet enjoying continuous, new, mystical revelation.

As Knox points out, in his usual scintillating style:

in Calvin’s Geneva … and in the Puritan colonies of America, the left wing of the Reformation signalized its ascendancy by enforcing the rigorism of its morals with every available machinery of discipline; by excommunication, or, if that failed, by secular punishment. Under such discipline sin became a crime, to be punished by the elect with an intolerable self-righteousness…

I have called this rigorist attitude a pale shadow of the theocratic principle, because a full-blooded theocracy demands the presence of a divinely inspired leader or leaders, to whom government belongs by right of mystical illumination. The great Reformers were not, it must be insisted, men of this calibre; they were pundits, men of the new learning…

And so one of the crucial differences between the Anabaptists and the more conservative reformers was that the former claimed continuing mystical revelation to themselves, forcing men such as Luther and Calvin to fall back on the Bible alone as the first as well as the last revelation.

The first leader of the ultratheocrat wing of the Anabaptists was Thomas Müntzer (c. 1489–1525). Born into comfort in Stolberg in Thuringia, Müntzer studied at the Universities of Leipzig and Frankfurt, and became highly learned in the scriptures, the classics, theology, and in the writings of the German mystics. Becoming a follower almost as soon as Luther launched the Reformation in 1520, Müntzer was recommended by Luther for the pastorate in the city of Zwickau. Zwickau was near the Bohemian border, and there the restless Müntzer was converted by the weaver and adept Niklas Storch, who had been in Bohemia, to the old Taborite doctrine that had flourished in Bohemia a century earlier. This doctrine consisted essentially of a continuing mystical revelation and the necessity for the elect to seize power and impose a society of theocratic communism by brutal force of arms. Furthermore, marriage was to be prohibited, and each man was to be able to have any woman at his will.

The passive wing of Anabaptists were voluntary anarchocommunists, who wished to live peacefully by themselves; but Müntzer adopted the Storch vision of blood and coercion. Defecting very rapidly from Lutheranism, Müntzer felt himself to be the coming prophet, and his teachings now began to emphasize a war of blood and extermination to be waged by the elect against the sinners. Müntzer claimed that the “living Christ” had permanently entered his own soul; endowed thereby with perfect insight into the divine will, Müntzer asserted himself to be uniquely qualified to fulfil the divine mission. He even spoke of himself as “becoming God.” Abandoning the world of learning, Müntzer was now ready for action.

In 1521, only a year after his arrival, the town council of Zwickau took fright at these increasingly popular ravings and ordered Müntzer’s expulsion from the city. In protest, a large number of the populace, in particular the weavers, led by Niklas Storch, rose in revolt, but the rising was put down. At that point, Müntzer hied himself to Prague, searching for Taborite remnants in the capital of Bohemia. Speaking in peasant metaphors, he declared that harvest time is here, “so God himself has hired me for his harvest. I have sharpened my scythe, for my thoughts are most strongly fixed on the truth, and my lips, hands, skin, hair, soul, body, life curse the unbelievers.” Müntzer, however, found no Taborite remnants; it did not help the prophet’s popularity that he knew no Czech, and had to preach with the aid of an interpreter. And so he was duly expelled from Prague.

After wandering around central Germany in poverty for several years, signing himself “Christ’s messenger,” Müntzer in 1523 gained a ministerial position in the small Thuringian town of Allstedt. There he established a wide reputation as a preacher employing the vernacular, and began to attract a large following of uneducated miners, whom he formed into a revolutionary organization called “The League of the Elect.”

A turning point in Müntzer’s stormy career came a year later, when Duke John, a prince of Saxony and a Lutheran, hearing alarming rumours about him, came to little Allstedt and asked Müntzer to preach him a sermon. This was Müntzer’s opportunity, and he seized it. He laid it on the line: he called upon the Saxon princes to make their choice and take their stand, either as servants of God or of the Devil. If the Saxon princes are to take their stand with God, then they “must lay on with the sword.” “Don’t let them live any longer,” counselled our prophet, “the evil-doers who turn us away from God. For a godless man has no right to live if he hinders the godly.” Müntzer’s definition of the “godless,” of course, was all-inclusive. “The sword is necessary to exterminate” priests, monks and godless rulers. But, Müntzer warned, if the princes of Saxony fail in this task, if they falter, “the sword shall be taken from them … If they resist, let them be slaughtered without mercy….” Müntzer then returned to his favorite harvest-time analogy: “At the harvest-time, one must pluck the weeds out of God’s vineyard … For the ungodly have no right to live, save what the Elect chooses to allow them…. “In this way the millennium, the thousand-year Kingdom of God on earth, would be ushered in. But one key requisite is necessary for the princes to perform that task successfully; they must have at their elbow a priest/prophet (guess who!) to inspire and guide their efforts.

Oddly enough for an era when no First Amendment restrained rulers from dealing sternly with heresy, Duke John seemed not to care about Müntzer’s frenetic ultimatum. Even after Müntzer proceeded to preach a sermon proclaiming the imminent overthrow of all tyrants and the beginning of the messianic kingdom, the duke did nothing. Finally, under the insistent prodding of Luther that Müntzer was becoming dangerous, Duke John told the prophet to refrain from any provocative preaching until his case was decided by his brother, the elector.

“The clergy, which constituted the ruling elite of the state, exempted themselves from taxation while imposing very heavy taxes on the rest of the populace.”

This mild reaction by the Saxon princes, however, was enough to set Thomas Müntzer on his final revolutionary road. The princes had proved themselves untrustworthy; the mass of the poor were now to make the revolution. The poor were the elect, and would establish a rule of compulsory egalitarian communism, a world where all things would be owned in common by all, where everyone would be equal in everything and each person would receive according to his need. But not yet. For even the poor must first be broken of worldly desires and frivolous enjoyments, and must recognize the leadership of a new “servant of God” who “must stand forth in the spirit of Elijah … and set things in motion.” (Again, guess who!)

Seeing Saxony as inhospitable, Müntzer climbed over the town wall of Allstedt and moved in 1524 to the Thuringian city of Muhlhausen. An expert in fishing in troubled waters, Müntzer found a friendly home in Muhlhausen, which had been in a state of political turmoil for over a year. Preaching the impending extermination of the ungodly, Müntzer paraded around the town at the head of an armed band, carrying in front of him a red crucifix and a naked sword. Expelled from Muhlhausen after a revolt by his allies was suppressed, Müntzer went to Nuremberg, which in turn expelled him after he published some revolutionary pamphlets. After wandering through southwestern Germany, Müntzer was invited back to Muhlhausen in February 1525, where a revolutionary group had taken over.

Thomas Müntzer and his allies proceeded to impose a communist regime on the city of Muhlhausen. The monasteries were seized, and all property was decreed to be in common, and the consequence, as a contemporary observer noted, was that “he so affected the folk that no one wanted to work.” The result was that the theory of communism and love quickly became in practice an alibi for systemic theft:

when anyone needed food or clothing he went to a rich man and demanded it of him in Christ’s name, for Christ had commanded that all should share with the needy. And what was not given freely was taken by force. Many acted thus … Thomas [Müntzer] instituted this brigandage and multiplied it every day.

At that point, the great Peasants’ War erupted throughout Germany, a rebellion launched by the peasantry in favor of their local autonomy and in opposition to the new centralizing, high-tax, absolutist rule of the German princes. Throughout Germany, the princes crushed the feebly armed peasantry with great brutality, massacring about 100,000 peasants in the process. In Thuringia, the army of the princes confronted the peasants on May 15 with a great deal of artillery and 2,000 cavalry, luxuries denied to the peasantry. The landgrave of Hesse, commander of the princes’ army, offered amnesty to the peasants if they would hand over Müntzer and his immediate followers. The peasants were strongly tempted, but Müntzer, holding aloft his naked sword, gave his last flaming speech, declaring that God had personally promised him victory; that he would catch all the enemy cannon balls in the sleeves of his cloak; that God would protect them all. Just at the strategic moment of Müntzer’s speech, a rainbow appeared in the heavens, and Müntzer had previously adopted the rainbow as the symbol of his movement. To the credulous and confused peasantry, this seemed a veritable sign from Heaven. Unfortunately, the sign didn’t work, and the princes’ army crushed the peasants, killing 5,000 while losing only half a dozen men. Müntzer himself fled and hid, but was captured a few days later, tortured into confession, and then executed.

Thomas Müntzer and his signs may have been defeated, and his body may have moldered in the grave, but his soul kept marching on. Not only was his spirit kept alive by followers in his own day, but also by Marxist historians from Engels to the present day, who saw in this deluded mystic an epitome of social revolution and the class struggle, and a forerunner of the chiliastic prophesies of the “communist stage” of the supposedly inevitable Marxian future.

The Müntzerian cause was soon picked up by a former disciple, the bookbinder Hans Hut. Hut claimed to be a prophet sent by God to announce that at Whitsuntide, 1528, Christ would return to earth and give the power to enforce justice to Hut and his following of rebaptized saints. The saints would then “take up double-edged swords” and wreak God’s vengeance on priests, pastors, kings and nobles. Hut and his followers would then “establish the rule of Hans Hut on earth,” with Muhlhausen as the favored capital. Christ was then to establish a millennium marked by communism and free love. Hut was captured in 1527 (before Jesus had had a chance to return), imprisoned at Augsburg, and killed trying to escape. For a year or two, Huttian followers kept emerging, at Augsburg, Nuremberg, and Esslingen, in southern Germany, threatening to set up their communist Kingdom of God by force of arms. But by 1530 they were smashed and suppressed by the alarmed authorities. Müntzerian-type Anabaptism was now to move to northwestern Germany.

Totalitarian Communism in Münster

Northwestern Germany in that era was dotted by a number of small ecclesiastical states, each run by a prince-bishop. The state was run by aristocratic clerics, who elected one of their own as bishop. Generally, these bishops were secular lords who were not ordained. By bargaining over taxes, the capital city of each of these states had usually wrested for itself a degree of autonomy. The clergy, which constituted the ruling elite of the state, exempted themselves from taxation while imposing very heavy taxes on the rest of the populace. Generally, the capital cities came to be run by their own power elite, an oligarchy of guilds, which used government power to cartellize their various professions and occupations.

The largest of these ecclesiastical states in northwest Germany was the bishopric of Münster, and its capital city of Münster, a town of some 10,000 people, was run by the town guilds. The Münster guilds were particularly exercised by the economic competition of the monks, who were not forced to obey guild restrictions and regulations.

During the Peasants’ War, the capital cities of several of these states, including Münster, took the opportunity to rise in revolt, and the bishop of Münster was forced to make numerous concessions. With the crushing of the rebellion, however, the bishop took back the concessions, and reestablished the old regime. By 1532, however, the guilds, supported by the people, were able to fight back and take over the town, soon forcing the bishop to recognize Münster officially as a Lutheran city.

It was not destined to remain so for long, however. From all over the northwest, hordes of Anabaptist enthusiasts flooded into Münster, seeking the onset of the New Jerusalem. From the northern Netherlands came hundreds of Melchiorites, followers of the itinerant visionary Melchior Hoffmann. Hoffmann, an uneducated furrier’s apprentice from Swabia in southern Germany, had for years wandered through Europe preaching the imminence of the Second Coming, which he had concluded from his researches would occur in 1533, the fifteenth centenary of the death of Jesus. Melchiorism had flourished in the northern Netherlands, and many adepts now poured into Münster, rapidly converting the poorer classes of the town.

Meanwhile, the Anabaptist cause in Münster received a shot in the arm, when the eloquent and popular young minister Bernt Rothmann, a highly educated son of a town blacksmith, converted to Anabaptism. Originally a Catholic priest, Rothmann had become a friend of Luther and the head of the Lutheran movement in Münster. Converted to Anabaptism, Rothmann lent his eloquent preaching to the cause of communism as it had supposedly existed in the primitive Christian Church, holding everything in common with no Mine and Thine and giving to each according to his “need.” In response to Rothmann’s reputation, thousands flocked to Münster, hundreds of the poor, the rootless, those hopelessly in debt, and “people who, having run through the fortunes of their parents, were earning nothing by their own industry….” People, in general, who were attracted by the idea of “plundering and robbing the clergy and the richer burghers.” The horrified burghers tried to drive out Rothmann and the Anabaptist preachers, but to no avail.

In 1533, Melchior Hoffmann, sure that the Second Coming would happen any day, returned to Strasbourg, where he had had great success, calling himself the Prophet Elias. He was promptly clapped into jail, and remained there until his death a decade later.

Hoffmann, for all the similarities with the others, was a peaceful man who counselled nonviolence to his followers; after all, if Jesus were imminently due to return, why commit against unbelievers? Hoffmann’s imprisonment, and of course the fact that 1533 came and went without a Second Coming, discredited Melchior, and so his Münster followers turned to far more violent, post-millennialist prophets who believed that they would have to establish the Kingdom by fire and sword.

The new leader of the coercive Anabaptists was a Dutch baker from Haarlem, one Jan Matthys (Matthyszoon). Reviving the spirit of Thomas Müntzer, Matthys sent out missionaries or “apostles” from Haarlem to rebaptize everyone they could, and to appoint “bishops” with the power to baptize. When the new apostles reached Münster in early 1534, they were greeted, as we might expect, with enormous enthusiasm. Caught up in the frenzy, even Rothmann was rebaptized once again, followed by many ex-nuns and a large part of the population. Within a week the apostles had rebaptized 1 400 people.

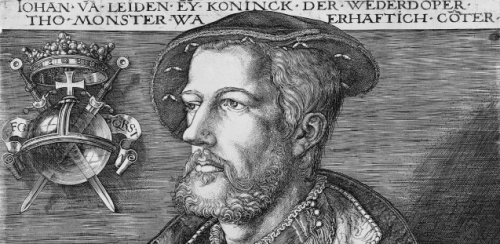

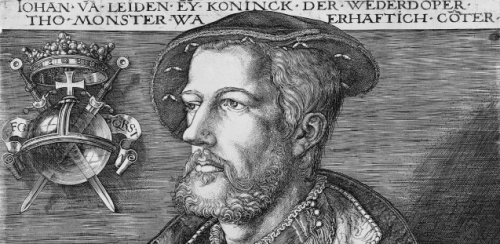

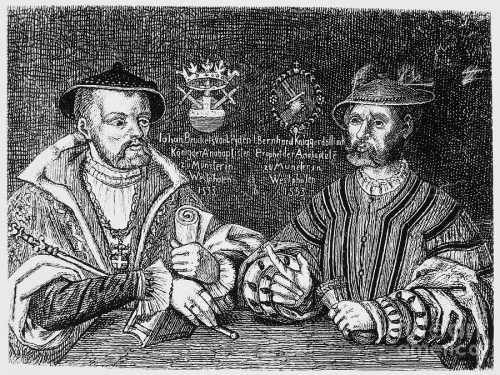

Another apostle soon arrived, a young man of 25 who had been converted and baptized by Matthys only a couple of months earlier. This was Jan Bockelson (Bockelszoon, Beukelsz), who was soon to become known in song and story as Johann of Leyden. Though handsome and eloquent, Bockelson was a troubled soul, having been born the illegitimate son of the mayor of a Dutch village by a woman serf from Westphalia. Bockelson began life as an apprentice tailor, married a rich widow, but then went bankrupt when he set himself up as a self-employed merchant.

In February 1534, Bockelson won the support of the wealthy cloth merchant Bernt Knipperdollinck, the powerful leader of the Münster guilds, and shrewdly married Knipperdollinck’s daughter. On February 8, son-in-law and father-in-law ran wildly through the streets together, calling upon everyone to repent. After much frenzy, mass writhing on the ground, and the seeing of apocalyptic visions, the Anabaptists rose up and seized the town hall, winning legal recognition for their movement.

In response to this successful uprising, many wealthy Lutherans left town, and the Anabaptists, feeling exuberant, sent messengers to surrounding areas summoning everyone to come to Münster. The rest of the world, they proclaimed, would be destroyed in a month or two; only Münster would be saved, to become the New Jerusalem. Thousands poured in from as far away as Flanders and Frisia in the northern Netherlands. As a result, the Anabaptists soon won a majority on the town council, and this success was followed three days later, on February 24, by an orgy of looting of books, statues and paintings from the churches and throughout the town. Soon Jan Matthys himself arrived, a tall, gaunt man with a long black beard. Matthys, aided by Bockelson, quickly became the virtual dictator of the town. The coercive Anabaptists had at last seized a city. The Great Communist Experiment could now begin.

The first mighty program of this rigid theocracy was, of course, to purge the New Jerusalem of the unclean and the ungodly, as a prelude to their ultimate extermination throughout the world. Matthys called therefore for the execution of all remaining Catholics and Lutherans, but Knipperdollinck’s cooler head prevailed, since he warned Matthys that slaughtering all other Christians than themselves might cause the rest of the world to become edgy, and they might all come and crush the New Jerusalem in its cradle. It was therefore decided to do the next best thing, and on February 27 the Catholic and Lutherans were driven out of the city, in the midst of a horrendous snowstorm. In a deed prefiguring communist Cambodia, all non-Anabaptists, including old people, invalids, babies and pregnant women were driven into the snowstorm, and all were forced to leave behind all their money, property, food and clothing. The remaining Lutherans and Catholics were compulsorily rebaptized, and all refusing this ministration were put to death.

The expulsion of all Lutherans and Catholics was enough for the bishop, who began a long military siege of the town the next day, on February 28. With every person drafted for siege work, Jan Matthys launched his totalitarian communist social revolution.

The first step was to confiscate the property of the expelled. All their worldly goods were placed in central depots, and the poor were encouraged to take “according to their needs,” the “needs” to be interpreted by seven appointed “deacons” chosen by Matthys. When a blacksmith protested at these measures imposed by Dutch foreigners, Matthys arrested the courageous smithy. Summoning the entire population of the town, Matthys personally stabbed, shot, and killed the “godless” blacksmith, as well as throwing into prison several eminent citizens who had protested against his treatment. The crowd was warned to profit by this public execution, and they obediently sang a hymn in honour of the killing.

A key part of the Anabaptist reign of terror in Münster was now unveiled. Unerringly, just as in the case of the Cambodian communists four-and-a-half centuries later, the new ruling elite realized that the abolition of the private ownership of money would reduce the population to total slavish dependence on the men of power. And so Matthys, Rothmann and others launched a propaganda campaign that it was unchristian to own money privately; that all money should be held in “common,” which in practice meant that all money whatsoever must be handed over to Matthys and his ruling clique. Several Anabaptists who kept or hid their money were arrested and then terrorized into crawling to Matthys on their knees, begging forgiveness and beseeching him to intercede with God on their behalf. Matthys then graciously “forgave” the sinners.

After two months of severe and unrelenting pressure, a combination of propaganda about the Christianity of abolishing private money, and threats and terror against those who failed to surrender, the private ownership of money was effectively abolished in Münster. The government seized all the money and used it to buy or hire goods from the outside world. Wages were doled out in kind by the only remaining employer: the theocratic Anabaptist state.

Food was confiscated from private homes, and rationed according to the will of the government deacons. Also, to accommodate the immigrants, all private homes were effectively communized, with everyone permitted to quarter themselves anywhere; it was now illegal to close, let alone lock, doors. Communal dining-halls were established, where people ate together to readings from the Old Testament.

This compulsory communism and reign of terror was carried out in the name of community and Christian “love.” All this communization was considered the first giant steps toward total egalitarian communism, where, as Rothmann put it, “all things were to be in common, there was to be no private property and nobody was to do any more work, but simply trust in God.” The workless part, of course, somehow never arrived.

A pamphlet sent in October 1534 to other Anabaptist communities hailed the new order of Christian love through terror:

For not only have we put all our belongings into a common pool under the care of deacons, and live from it according to our need; we praise God through Christ with one heart and mind and are eager to help one another with every kind of service.

And accordingly, everything which has served the purposes of selfseeking and private property, such as buying and selling, working for money, taking interest and practising usury … or eating and drinking the sweat of the poor … and indeed everything which offends against love – all such things are abolished amongst us by the power of love and community.

With high consistency, the Anabaptists of Münster made no pretence about preserving intellectual freedom while communizing all material property. For the Anabaptists boasted of their lack of education, and claimed that it was the unlearned and the unwashed who would be the elect of the world. The Anabaptist mob took particular delight in burning all the books and manuscripts in the cathedral library, and finally, in mid-March 1534, Matthys outlawed all books except the Good Book – the Bible. To symbolize a total break with the sinful past, all privately and publicly owned books were thrown upon a great communal bonfire. All this ensured, of course, that the only theology or interpretation of the scriptures open to the Münsterites was that of Matthys and the other Anabaptist preachers.

At the end of March, however, Matthys’s swollen hubris laid him low. Convinced at Eastertime that God had ordered him and a few of the faithful to lift the bishop’s siege and liberate the town, Matthys and a few others rushed out of the gates at the besieging army, and were literally hacked to pieces. In an age when the idea of full religious liberty was virtually unknown, one can imagine that any Anabaptists whom the more orthodox Christians might get hold of would not earn a very kindly reward.

The death of Matthys left Münster in the hands of young Bockelson. And if Matthys had chastised the people of Münster with whips, Bockelson would chastise them with scorpions. Bockelson wasted little time in mourning his mentor. He preached to the faithful: “God will give you another Prophet who will be more powerful.” How could this young enthusiast top his master? Early in May, Bockelson caught the attention of the town by running naked through the streets in a frenzy, falling then into a silent three-day ecstasy. When he rose again, he announced to the entire populace a new dispensation that God had revealed to him. With God at his elbow, Bockelson abolished the old functioning town offices of council and burgomasters, and installed a new ruling council of 12 elders, with himself, of course, as the eldest of the elders. The elders were now given total authority over the life and death, the property and the spirit, of every inhabitant of Münster. A strict system of forced labour was imposed, with all artisans not drafted into the military now public employees, working for the community for no monetary reward. This meant, of course, that the guilds were now abolished.

The totalitarianism in Münster was now complete. Death was now the punishment for virtually every independent act, good or bad. Capital punishment was decreed for the high crimes of murder, theft, lying, avarice, and quarreling! Also death was decreed for every conceivable kind of insubordination: the young against their parents, wives against their husbands and, of course, anyone at all against the chosen representatives of God on earth, the totalitarian government of Münster. Bernt Knipperdollinck was appointed high executioner to enforce the decrees.

The only aspect of life previously left untouched was sex, and this now came under the hammer of Bockelson’s total despotism. The only sexual relation permitted was marriage between two Anabaptists. Sex in any other form, including marriage with one of the “godless,” was a capital crime. But soon Bockelson went beyond this rather old-fashioned credo, and decided to establish compulsory polygamy in Münster. Since many of the expellees had left their wives and daughters behind, Münster now had three times as many marriageable women as men, so that polygamy had become technologically feasible. Bockelson converted the other rather startled preachers by citing polygamy among the patriarchs of Israel, as well as by threatening dissenters with death.

Compulsory polygamy was a bit too much for many of the Münsterites, who launched a rebellion in protest. The rebellion, however, was quickly crushed and most of the rebels put to death. Execution was also the fate of any further dissenters. And so by August 1534, polygamy was coercively established in Münster. As one might expect, young Bockelson took an instant liking to the new regime, and before long he had a harem of 15 wives, including Divara, the beautiful young widow of Jan Matthys. The rest of the male population also began to take to the new decree as ducks to water. Many of the women did not take as kindly to the new dispensation, and so the elders passed a law ordering compulsory marriage for every women under (and presumably also over) a certain age, which usually meant being a compulsory third or fourth wife.

Moreover, since marriage among the godless was not only invalid but also illegal, the wives of the expellees now became fair game, and were forced to “marry” good Anabaptists. Refusal to comply with the new law was punishable, of course, by death, and a number of women were actually executed as a result. Those “old” wives who resented the new wives coming into their household were also suppressed, and their quarreling was made a capital crime. Many women were executed for quarreling.

But the long arm of the state could reach only just so far and, in their first internal setback, Bockelson and his men had to relent, and permit divorce. Indeed, the ceremony of marriage was now outlawed totally, and divorce made very easy. As a result, Münster now fell under a regime of what amounted to compulsory free love. And so, within the space of only a few months, a rigid puritanism had been transmuted into a regime of compulsory promiscuity.

Meanwhile, Bockelson proved to be an excellent organizer of a besieged city. Compulsory labour, military and civilian, was strictly enforced. The bishop’s army consisted of poorly and irregularly paid mercenaries, and Bockelson was able to induce many of them to desert by offering them regular pay (pay for money, that is, in contrast to Bockelson’s rigid internal moneyless communism). Drunken ex-mercenaries were, however, shot immediately. When the bishop fired pamphlets into the town offering a general amnesty in return for surrender, Bockelson made reading such pamphlets a crime punishable by – of course – death.

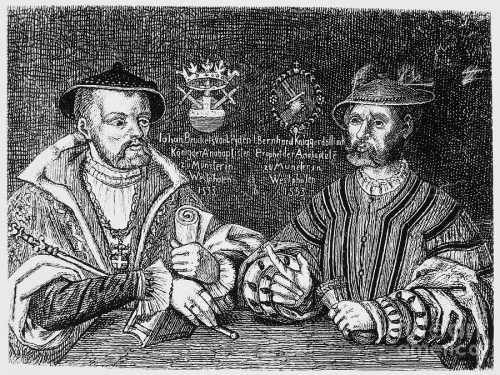

At the end of August 1534, the bishop’s armies were in disarray and the siege temporarily lifted. Jan Bockelson seized this opportunity to carry his “egalitarian” communist revolution one step further: he had himself named king and Messiah of the Last Days.

Proclaiming himself king might have appeared tacky and perhaps even illegitimate. And so Bockelson had one Dusentschur, a goldsmith from a nearby town and a self-proclaimed prophet, do the job for him. At the beginning of September, Dusentschur announced to one and all a new revelation: Jan Bockelson was to be king of the whole world, the heir of King David, to keep that Throne until God himself reclaimed his Kingdom. Unsurprisingly, Bockelson confirmed that he himself had had the very same revelation. Dusentschur then presented a sword of justice to Bockelson, anointed him, and proclaimed him king of the world. Bockelson, of course, was momentarily modest; he prostrated himself and asked guidance from God. But he made sure to get that guidance swiftly. And it turned out, mirabile dictu, that Dusentschur was right. Bockelson proclaimed to the crowd that God had now given him “power over all nations of the earth’; anyone who might dare to resist the will of God “shall without delay be put to death with the sword.”

And so, despite a few mumbled protests, Jan Bockelson was declared king of the world and Messiah, and the Anabaptist preachers of Münster explained to their bemused flock that Bockelson was indeed the Messiah as foretold in the Old Testament. Bockelson was rightfully ruler of the entire world, both temporal and spiritual.

It often happens with “egalitarians” that a hole, a special escape hatch from the drab uniformity of life, is created – for themselves. And so it was with King Bockelson. It was, after all, important to emphasize in every way the importance of the Messiah’s advent. And so Bockelson wore the finest robes, metals and jewellery; he appointed courtiers and gentlemen-at-arms, who also appeared in splendid finery. King Bockelson’s chief wife, Divara, was proclaimed queen of the world, and she too was dressed in great finery and had a suite of courtiers and followers. This luxurious court of some two hundred people was housed in fine mansions requisitioned for the occasion. A throne draped with a cloth of gold was established in the public square, and King Bockelson would hold court there, wearing a crown and carrying a sceptre. A royal bodyguard protected the entire procession. All Bockelson’s loyal aides were suitably rewarded with high status and finery: Knipperdollinck was the chief minister, and Rothmann royal orator.

If communism is the perfect society, somebody must be able to enjoy its fruits; and who better but the Messiah and his courtiers? Though private property in money was abolished, the confiscated gold and silver was now minted into ornamental coins for the glory of the new king. All horses were confiscated to build up the king’s armed squadron. Also, names in Münster were transformed; all the streets were renamed; Sundays and feastdays were abolished; and all new-born children were named personally by the king in accordance with a special pattern.

“Some of the main victims to be executed were women: women who were killed for denying their husbands their marital rights, for insulting a preacher, or for daring to practice bigamy — polygamy, of course, being solely a male privilege.”

In a starving slave society such as communist Münster, not all citizens could live in the luxury enjoyed by the king and his court; indeed, the new ruling class was now imposing a rigid class oligarchy seldom seen before. So that the king and his nobles might live in high luxury, rigorous austerity was imposed on everyone else in Münster. The subject population had already been robbed of their houses and much of their food; now all superfluous luxury among the masses was outlawed. Clothing and bedding were severely rationed, and all “surplus” turned over to King Bockelson under pain of death. Every house was searched thoroughly and 83 wagonloads of “surplus” clothing collected.

It is not surprising that the deluded masses of Münster began to grumble at being forced to live in abject poverty while the king and his courtiers lived in extreme luxury on the proceeds of their confiscated belongings. And so Bockelson had to beam them some propaganda to explain the new system. The explanation was this: it was all right for Bockelson to live in pomp and luxury because he was already completely dead to the world and the flesh. Since he was dead to the world, in a deep sense his luxury didn’t count. In the style of every guru who has ever lived in luxury among his credulous followers, he explained that for him material objects had no value. How such “logic” can ever fool anyone passes understanding. More important, Bockelson assured his subjects that he and his court were only the advance guard of the new order; soon, they too would be living in the same millennial luxury. Under their new order, the people of Münster would forge outward, armed with God’s will, and conquer the entire world, exterminating the unrighteous, after which Jesus would return and they would all live in luxury and perfection. Equal communism with great luxury for all would then be achieved.

Greater dissent meant, of course, greater terror, and King Bockelson’s reign of “love” intensified its intimidation and slaughter. As soon as he proclaimed the monarchy, the prophet Dusentschur announced a new divine revelation: all who persisted in disagreeing with or disobeying King Bockelson would be put to death, and their very memory blotted out. They would be extirpated forever. Some of the main victims to be executed were women: women who were killed for denying their husbands their marital rights, for insulting a preacher, or for daring to practice bigamy – polygamy, of course, being solely a male privilege.

Despite his continual preaching about marching forth to conquer the world, King Bockelson was not crazy enough to attempt that feat, especially since the bishop’s army was again besieging the town. Instead, he shrewdly used much of the expropriated gold and silver to send out apostles and pamphlets to surrounding areas of Europe, attempting to rouse the masses for Anabaptist revolution. The propaganda had considerable effect, and serious mass risings occurred throughout Holland and northwestern Germany during January 1535. A thousand armed Anabaptists gathered under the leadership of someone who called himself Christ, son of God; and serious Anabaptist rebellions took place in west Frisia, in the town of Minden, and even in the great city of Amsterdam, where the rebels managed to capture the town hall. All these risings were eventually suppressed, with the considerable help of betrayal to the various authorities of the names of the rebels and of the location of their munition dumps.

“At all times the king and his court ate and drank well, while famine and devastation raged throughout the town of Münster, and the masses ate literally everything, even inedible, they could lay their hands on.”

The princes of northwestern Europe by this time had had enough; and all the states of the Holy Roman Empire agreed to supply troops to crush the monstrous and hellish regime at Münster. For the first time, in January 1535, Münster was totally and successfully blockaded and cut off from the outside world. The Establishment then proceeded to starve the population of Münster into submission. Food shortages appeared immediately, and the crisis was met with characteristic vigour: all remaining food was confiscated, and all horses killed, for the benefit of feeding the king, his royal court and his armed guards. At all times the king and his court ate and drank well, while famine and devastation raged throughout the town of Münster, and the masses ate literally everything, even inedible, they could lay their hands on.

King Bockelson kept his rule by beaming continual propaganda and promises to the starving masses. God would definitely save them by Easter, or else he would have himself burnt in the public square. When Easter came and went, Bockelson craftily explained that he had meant only “spiritual” salvation. He promised that God would change cobblestones to bread, and of course that did not come to pass either. Finally, Bockelson, long fascinated with the theatre, ordered his starving subjects to engage in three days of dancing and athletics. Dramatic performances were held, as well as a Black Mass. Starvation, however, was now becoming all-pervasive.

The poor hapless people of Münster were now doomed totally. The bishop kept firing leaflets into the town promising a general amnesty if the people would only revolt and depose King Bockelson and his court and hand them over. To guard against such a threat, Bockelson stepped up his reign of terror still further. In early May, he divided the town into 12 sections, and placed a “duke” over each one with an armed force of 24 men. The dukes were foreigners like himself; as Dutch immigrants they were likely to be loyal to Bockelson. Each duke was strictly forbidden to leave his section, and the dukes, in turn, prohibited any meetings whatsoever of even a few people. No one was allowed to leave town, and any caught plotting to leave, helping anyone else to leave, or criticizing the king, was instantly beheaded, usually by King Bockelson himself. By mid-June such deeds were occurring daily, with the body often quartered and nailed up as a warning to the masses.

The poor hapless people of Münster were now doomed totally. The bishop kept firing leaflets into the town promising a general amnesty if the people would only revolt and depose King Bockelson and his court and hand them over. To guard against such a threat, Bockelson stepped up his reign of terror still further. In early May, he divided the town into 12 sections, and placed a “duke” over each one with an armed force of 24 men. The dukes were foreigners like himself; as Dutch immigrants they were likely to be loyal to Bockelson. Each duke was strictly forbidden to leave his section, and the dukes, in turn, prohibited any meetings whatsoever of even a few people. No one was allowed to leave town, and any caught plotting to leave, helping anyone else to leave, or criticizing the king, was instantly beheaded, usually by King Bockelson himself. By mid-June such deeds were occurring daily, with the body often quartered and nailed up as a warning to the masses.

Bockelson would undoubtedly have let the entire population starve to death rather than surrender; but two escapees betrayed weak spots in the town’s defence, and on the night of June 24, 1535, the nightmare New Jerusalem at last came to a bloody end. The last several hundred Anabaptist fighters surrendered under an amnesty and were promptly massacred, and Queen Divara was beheaded. As for ex-King Bockelson, he was led about on a chain, and the following January, along with Knipperdollinck, was publicly tortured to death, and their bodies suspended in cages from a church tower.

The old Establishment of Münster was duly restored and the city became Catholic once more. The stars were once again in their courses, and the events of 1534–35 understandably led to an abiding distrust of mysticism and enthusiast movements throughout Protestant Europe.

This article is excerpted from An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought, vol. 1, Economic Thought Before Adam Smith.

The Best of Murray N. Rothbard

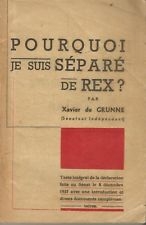

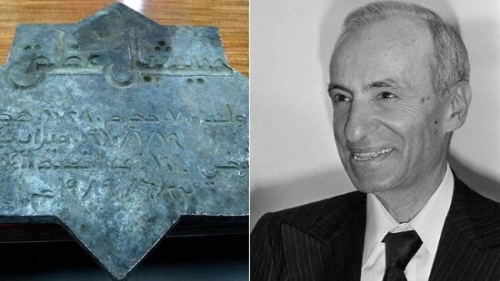

Qui est Xavier de Grunne ?

Qui est Xavier de Grunne ? Pierre Nothomb, fondateur au cours des années 1920 des Jeunesses nationales, a été inquiété à plusieurs reprises durant la guerre par les Allemands pour ses actes de résistance. La Légion Nationale, organisation nationaliste belge fondée en 1922 et qui devient ensuite un mouvement d’Ordre nouveau qui affronte physiquement les milices socialistes et communistes, entre dès le début de l’occupation dans la Résistance. Plusieurs de ses membres sont fusillés par les Allemands et son dirigeant, l’avocat Paul Hoornaert, meurt en déportation. Un certain nombre de rexistes ou d’anciens rexistes se sont également retrouvés dans la Résistance. L’écrivain Robert du Bois de Vroylande, ainsi que le rédacteur en chef du quotidien rexiste Le Pays Réel et membre du Conseil politique du mouvement rexiste Hubert d’Ydewalle, qui ont tous deux rompu avec Rex avant la guerre, meurent en déportation. Le Mouvement National Royaliste (Nationale Koninklijke Beweging), une des organisations de résistance du pays, est fondé par des rexistes restés fidèles au Roi Léopold III. Ajoutons que les intellectuels adeptes de l’Ordre nouveau et professeurs d’université Fernand Desonay et Charles Terlinden se sont retrouvés eux aussi dans la Résistance.

Pierre Nothomb, fondateur au cours des années 1920 des Jeunesses nationales, a été inquiété à plusieurs reprises durant la guerre par les Allemands pour ses actes de résistance. La Légion Nationale, organisation nationaliste belge fondée en 1922 et qui devient ensuite un mouvement d’Ordre nouveau qui affronte physiquement les milices socialistes et communistes, entre dès le début de l’occupation dans la Résistance. Plusieurs de ses membres sont fusillés par les Allemands et son dirigeant, l’avocat Paul Hoornaert, meurt en déportation. Un certain nombre de rexistes ou d’anciens rexistes se sont également retrouvés dans la Résistance. L’écrivain Robert du Bois de Vroylande, ainsi que le rédacteur en chef du quotidien rexiste Le Pays Réel et membre du Conseil politique du mouvement rexiste Hubert d’Ydewalle, qui ont tous deux rompu avec Rex avant la guerre, meurent en déportation. Le Mouvement National Royaliste (Nationale Koninklijke Beweging), une des organisations de résistance du pays, est fondé par des rexistes restés fidèles au Roi Léopold III. Ajoutons que les intellectuels adeptes de l’Ordre nouveau et professeurs d’université Fernand Desonay et Charles Terlinden se sont retrouvés eux aussi dans la Résistance. Contrairement à ce qui a été souvent écrit, il apparaît que Xavier de Grunne est resté lié à Rex jusqu’en 1939, et que la rupture annoncée en 1937 au sein de l’ouvrage de Xavier de Grunne intitulé Pourquoi je suis séparé de Rex ? est purement stratégique afin de disposer de la liberté de pouvoir critiquer l’Église qui attaque Rex, tout en ne froissant pas les électeurs rexistes qui sont pour la plupart des catholiques convaincus.

Contrairement à ce qui a été souvent écrit, il apparaît que Xavier de Grunne est resté lié à Rex jusqu’en 1939, et que la rupture annoncée en 1937 au sein de l’ouvrage de Xavier de Grunne intitulé Pourquoi je suis séparé de Rex ? est purement stratégique afin de disposer de la liberté de pouvoir critiquer l’Église qui attaque Rex, tout en ne froissant pas les électeurs rexistes qui sont pour la plupart des catholiques convaincus.

» La HUAC avait été mise en place à la Chambre des Représentants en 1934

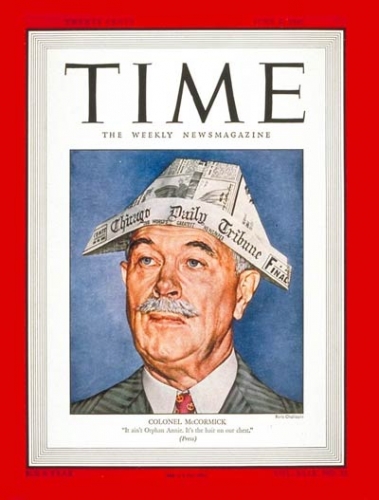

» La HUAC avait été mise en place à la Chambre des Représentants en 1934  » Ce n'était que la plus visible des mesures répressives qui furent prises lors de la “Brown Scare” et qui furent ensuite réutilisées lors de la “Red Scare”. Il s’agissait d’un simple ajustement suivant le tournant de la politique étrangère américaine et un changement ultérieur de l'opinion publique américaine. Le FBI avait infiltré des groupes comme le Comité America First qui s'opposait à l'entrée des Etats-Unis dans la Seconde Guerre mondiale, il avait mis sur écoutes des dirigeants conservateurs tel que le directeur du Chicago Tribune Robert McCormick ; il suffisait alors de réorienter toutes ces procédures vers les cibles de gauche. Mais rappelez-vous l’essentiel : c’est la gauche qui lança tout cela et fit mettre en place la répression dans toute son ampleur, alors qu’elle tenait le fouet.

» Ce n'était que la plus visible des mesures répressives qui furent prises lors de la “Brown Scare” et qui furent ensuite réutilisées lors de la “Red Scare”. Il s’agissait d’un simple ajustement suivant le tournant de la politique étrangère américaine et un changement ultérieur de l'opinion publique américaine. Le FBI avait infiltré des groupes comme le Comité America First qui s'opposait à l'entrée des Etats-Unis dans la Seconde Guerre mondiale, il avait mis sur écoutes des dirigeants conservateurs tel que le directeur du Chicago Tribune Robert McCormick ; il suffisait alors de réorienter toutes ces procédures vers les cibles de gauche. Mais rappelez-vous l’essentiel : c’est la gauche qui lança tout cela et fit mettre en place la répression dans toute son ampleur, alors qu’elle tenait le fouet. (D’un autre côté, Roosevelt, qui était d’abord un politicien roué assez éloigné de l’image idéalisée qu’on en fit et qui persiste, s’opposait aux tentatives légales d’avancement trop affirmé de la gauche radicale, comme par exemple lorsqu’il sabota indirectement la campagne de l’écrivain

(D’un autre côté, Roosevelt, qui était d’abord un politicien roué assez éloigné de l’image idéalisée qu’on en fit et qui persiste, s’opposait aux tentatives légales d’avancement trop affirmé de la gauche radicale, comme par exemple lorsqu’il sabota indirectement la campagne de l’écrivain

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Tocqueville décrit cette préparation à la grande guerre européenne (et je crois que mon ami

Tocqueville décrit cette préparation à la grande guerre européenne (et je crois que mon ami  Puis Tocqueville met les pieds dans le plat sans mâcher ses mots cette fois :

Puis Tocqueville met les pieds dans le plat sans mâcher ses mots cette fois : Comme notre Poutine, le tzar Nicolas garde son sang-froid :

Comme notre Poutine, le tzar Nicolas garde son sang-froid :

At an early age Yeats became involved in mysticism which would prove controversial his whole life. Kodani explains, “The early poetry of William Butler Yeats was very much bound up with the forces and interests of his early years. Many of these influences — such as that of Maud Gonne, his father, and his own mystic studies — have been elucidated by some careful scholarship.” Yeats’ writing was influenced by his study of mysticism. He joined the Theosophical Society as his immediate family’s tradition was not very religious. Later he “became interested in esoteric philosophy, and in 1890 was initiated into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn” (Seymour-Smith). He would pursue mystical philosophy the rest of his life to a greater or lesser degree.

At an early age Yeats became involved in mysticism which would prove controversial his whole life. Kodani explains, “The early poetry of William Butler Yeats was very much bound up with the forces and interests of his early years. Many of these influences — such as that of Maud Gonne, his father, and his own mystic studies — have been elucidated by some careful scholarship.” Yeats’ writing was influenced by his study of mysticism. He joined the Theosophical Society as his immediate family’s tradition was not very religious. Later he “became interested in esoteric philosophy, and in 1890 was initiated into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn” (Seymour-Smith). He would pursue mystical philosophy the rest of his life to a greater or lesser degree.

La révolte poétique sera l’expression d’un refus de cette expression culturelle de la Raison d’Etat. Les champions en seront, dans le domaine théâtral, Hardy, le grand Corneille lui-même, avant qu’il ne se convertisse aux règles, et en poésie, Régnier, anti-conformiste, individualiste original, Théophile de Viau, libertin converti, qui, bien que « moderniste », avait toujours sous sa plume le mot de « franchise », mort à 36 ans après avoir été mis au cachot par les cagots, Boisrobert, sévère pour un siècle voué à l’argent, Saint-Amant, La Ménardière, qui célébra « le grand Ronsard », le concettiste Tristan… Tous ces écrivains sont des êtres de plein air, des amants de la liberté, de la libre expression de soi, sans laquelle il n’est pas de noblesse. Même Sorel, le satirique qui ne l’aimait pas, louait « l’âme véritablement généreuse ». (1) Et il n’est pas d’auteur exprimant mieux cette aspiration qu’Honoré d’Urfé, qui a donné à la France l’exquis roman pastoral L’Astrée, qu’il situe dans le Forez, au milieu des bergers et des druides. Rien de plus étranger à l’ancien ligueur catholique que la médiocrité. Il prône une éthique platonicienne, fondée sur l’amour, le sublime, l’enthousiasme, la générosité, tous mouvements de l’âme et du cœur qui portent le fini vers Dieu. Honoré d’Urfé, c’est l’anti-Descartes, le négateur de l’esprit géométrique. Racan le suivra dans ses Bergeries, célébrant l’âge d’or. Mais l’Astrée est une utopie dans un siècle qui s’adonne à l’intérêt, à l’utilité, à l’ambition calculée, à la ruse, à la mathématique appliquée.

La révolte poétique sera l’expression d’un refus de cette expression culturelle de la Raison d’Etat. Les champions en seront, dans le domaine théâtral, Hardy, le grand Corneille lui-même, avant qu’il ne se convertisse aux règles, et en poésie, Régnier, anti-conformiste, individualiste original, Théophile de Viau, libertin converti, qui, bien que « moderniste », avait toujours sous sa plume le mot de « franchise », mort à 36 ans après avoir été mis au cachot par les cagots, Boisrobert, sévère pour un siècle voué à l’argent, Saint-Amant, La Ménardière, qui célébra « le grand Ronsard », le concettiste Tristan… Tous ces écrivains sont des êtres de plein air, des amants de la liberté, de la libre expression de soi, sans laquelle il n’est pas de noblesse. Même Sorel, le satirique qui ne l’aimait pas, louait « l’âme véritablement généreuse ». (1) Et il n’est pas d’auteur exprimant mieux cette aspiration qu’Honoré d’Urfé, qui a donné à la France l’exquis roman pastoral L’Astrée, qu’il situe dans le Forez, au milieu des bergers et des druides. Rien de plus étranger à l’ancien ligueur catholique que la médiocrité. Il prône une éthique platonicienne, fondée sur l’amour, le sublime, l’enthousiasme, la générosité, tous mouvements de l’âme et du cœur qui portent le fini vers Dieu. Honoré d’Urfé, c’est l’anti-Descartes, le négateur de l’esprit géométrique. Racan le suivra dans ses Bergeries, célébrant l’âge d’or. Mais l’Astrée est une utopie dans un siècle qui s’adonne à l’intérêt, à l’utilité, à l’ambition calculée, à la ruse, à la mathématique appliquée.

Was de geschiedenis van Rome een voorafspiegeling van die van het Duitsland waarin Theodor Mommsen leefde en stierf?

Was de geschiedenis van Rome een voorafspiegeling van die van het Duitsland waarin Theodor Mommsen leefde en stierf?  Zijn die harde woorden, die harde oordelen van Mommsen over Bismarck en het door hem verenigde Duitsland wel gerechtvaardigd?

Zijn die harde woorden, die harde oordelen van Mommsen over Bismarck en het door hem verenigde Duitsland wel gerechtvaardigd?

Recensé : Paulin Ismard,

Recensé : Paulin Ismard,

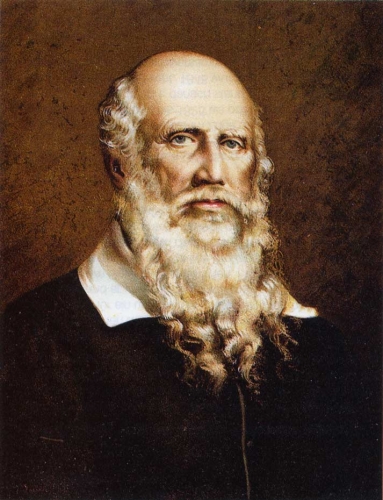

There are some differences between Jahn and the National Socialists: Jahn’s gymnastics unions were loosely organized and lacked hierarchies of authority, whereas the Hitler Youth was highly regulated and its program of physical education was more regimented and militaristic. Nonetheless both upheld a völkisch “blood and soil” worldview. For both the purpose of physical exercise was twofold: to prepare youths for combat by strengthening the body and mind and to instill in them a sense of national unity and purpose. Furthermore Jahn’s movement and National Socialism were both populist in nature (unlike the conservatism of the Prussian Junkers, as Viereck points out). Jahn endorsed classless communitarianism and likewise National Socialism was a mass movement that transcended class lines.

There are some differences between Jahn and the National Socialists: Jahn’s gymnastics unions were loosely organized and lacked hierarchies of authority, whereas the Hitler Youth was highly regulated and its program of physical education was more regimented and militaristic. Nonetheless both upheld a völkisch “blood and soil” worldview. For both the purpose of physical exercise was twofold: to prepare youths for combat by strengthening the body and mind and to instill in them a sense of national unity and purpose. Furthermore Jahn’s movement and National Socialism were both populist in nature (unlike the conservatism of the Prussian Junkers, as Viereck points out). Jahn endorsed classless communitarianism and likewise National Socialism was a mass movement that transcended class lines.

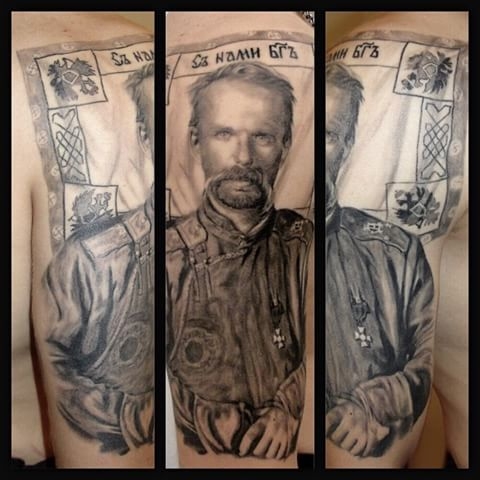

Le baron Ungern-Sternberg a été rendu célèbre par la description qu’en fit Ossendowski dans son fameux « Bêtes, hommes et Dieux », récit de ses voyages à travers la Mongolie. La figure du baron n’est d’ailleurs pas étrangère au succès du livre tant il semble concentrer en sa personne toutes les qualités qui font le charme si mystérieux de l’ouvrage, à commencer par le titre. « Bête, homme et Dieu » : il est tout à la fois. Au demeurant, il plane autour de lui comme un halo de légende qui, comme pour le récit d’Ossendowski, rend difficile de faire la part entre l’histoire et le mythe. Mais, si l’histoire d’Ossendowski, à l’image de celle d’Ungern, est pleine d’épisodes fabuleux très probablement inventés, il faut rappeler qu’elle fut accrédité pour l’essentiel par René Guénon, y compris des éléments parmi les plus merveilleux, lorsqu’il fit paraître, en réponse aux détracteurs d’Ossendowski, Le Roi du Monde, qui replace certains éléments du récit sur un plan initiatique.

Le baron Ungern-Sternberg a été rendu célèbre par la description qu’en fit Ossendowski dans son fameux « Bêtes, hommes et Dieux », récit de ses voyages à travers la Mongolie. La figure du baron n’est d’ailleurs pas étrangère au succès du livre tant il semble concentrer en sa personne toutes les qualités qui font le charme si mystérieux de l’ouvrage, à commencer par le titre. « Bête, homme et Dieu » : il est tout à la fois. Au demeurant, il plane autour de lui comme un halo de légende qui, comme pour le récit d’Ossendowski, rend difficile de faire la part entre l’histoire et le mythe. Mais, si l’histoire d’Ossendowski, à l’image de celle d’Ungern, est pleine d’épisodes fabuleux très probablement inventés, il faut rappeler qu’elle fut accrédité pour l’essentiel par René Guénon, y compris des éléments parmi les plus merveilleux, lorsqu’il fit paraître, en réponse aux détracteurs d’Ossendowski, Le Roi du Monde, qui replace certains éléments du récit sur un plan initiatique.

Les éditions Allia ont fait paraître il y a quelques mois, dans la paisible tiédeur d’une fin d’été, une nouvelle traduction de La Guerre de Jugurtha écrite par Salluste peu de temps après l’assassinat politique de César. L’excellent travail philologique mené par Nicolas

Les éditions Allia ont fait paraître il y a quelques mois, dans la paisible tiédeur d’une fin d’été, une nouvelle traduction de La Guerre de Jugurtha écrite par Salluste peu de temps après l’assassinat politique de César. L’excellent travail philologique mené par Nicolas

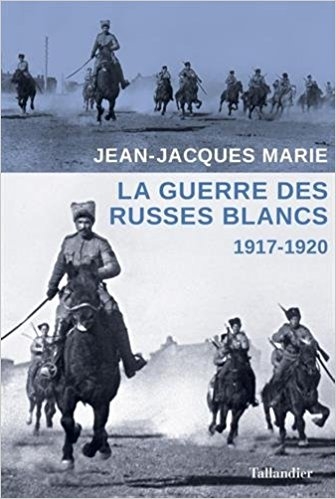

De fait, cette guerre se prolongea bien jusqu’en 1922 ; mais en 1920, la dernière armée de Russes blancs, celle de Wrangel, est battue et quitte la Crimée. Il reste certes des bandes armées mais plus d’armées. Les puissances étrangères qui soutiennent les Russes blancs l’ont compris, à commencer par la France et la Grande-Bretagne qui aident les forces de Wrangel à fuir avant d’abandonner le terrain et de remplacer sans tarder la pression militaire par la pression économique. Les techniques de combat sont rudimentaires et le grand nombre de victimes (environ quatre millions cinq cent mille) est beaucoup plus le fait des épidémies de typhus et de choléra, sans compter l’absence presque totale de soins pour les blessés, que des combats eux-mêmes. Il faudrait par ailleurs évoquer le rôle de la Légion tchécoslovaque (entre trente et quarante mille hommes), d’anciens prisonniers de guerre de l’armée austro-hongroise.

De fait, cette guerre se prolongea bien jusqu’en 1922 ; mais en 1920, la dernière armée de Russes blancs, celle de Wrangel, est battue et quitte la Crimée. Il reste certes des bandes armées mais plus d’armées. Les puissances étrangères qui soutiennent les Russes blancs l’ont compris, à commencer par la France et la Grande-Bretagne qui aident les forces de Wrangel à fuir avant d’abandonner le terrain et de remplacer sans tarder la pression militaire par la pression économique. Les techniques de combat sont rudimentaires et le grand nombre de victimes (environ quatre millions cinq cent mille) est beaucoup plus le fait des épidémies de typhus et de choléra, sans compter l’absence presque totale de soins pour les blessés, que des combats eux-mêmes. Il faudrait par ailleurs évoquer le rôle de la Légion tchécoslovaque (entre trente et quarante mille hommes), d’anciens prisonniers de guerre de l’armée austro-hongroise. Peu après sa nomination en 1904 comme gouverneur de la province de Saratov, le ministre de l’Intérieur Viatcheslav Plehve (photo) est assassiné. L’année suivante le général Viktor Sakharov est victime d’un attentat chez Stolypine, Stolypine qui a déjà échappé à trois tentatives d’assassinat, sans compter les courriers anonymes menaçant jusqu’à ses enfants.

Peu après sa nomination en 1904 comme gouverneur de la province de Saratov, le ministre de l’Intérieur Viatcheslav Plehve (photo) est assassiné. L’année suivante le général Viktor Sakharov est victime d’un attentat chez Stolypine, Stolypine qui a déjà échappé à trois tentatives d’assassinat, sans compter les courriers anonymes menaçant jusqu’à ses enfants. L’impératrice devint peu à peu implacablement hostile à Stolypine, une hostilité sur fond d’hémophilie, celle de son fils, un secret qui ne sortait pas du cercle étroit de la famille impériale et dont Stolypine ne sut jamais rien, ce qui lui rendit incompréhensible et insupportable la présence de Raspoutine au Palais, Raspoutine dont il ignorait les pouvoirs de thaumaturge. L’eût-il su, il aurait sans doute agi autrement. Il se montrait avant tout soucieux de la réputation de la famille impériale, une réputation qui se dégradait avec la présence de Raspoutine considéré comme un débauché, une rumeur dont le bien-fondé n’a pas été établi. Quoiqu’il en soit, Stolypine était sensible à cette rumeur qui se répandait, et il chargea le colonel Guérassimov, responsable de l’Okhrana, de lui faire un rapport sur ce personnage, un rapport peu favorable qu’il présenta au tsar qui en prit connaissance sans lui donner suite et en continuant à taire la maladie de son fils. Stolypine prit alors la décision de faire éloigner Raspoutine de Saint-Pétersbourg, une mission qu’il confia au colonel Guérassimov. L’impératrice protesta mais le tsar refusa de désavouer son ministre ; et elle se mit à haïr Stolypine en qui elle vit celui privait son fils ce qui le maintenait en vie.

L’impératrice devint peu à peu implacablement hostile à Stolypine, une hostilité sur fond d’hémophilie, celle de son fils, un secret qui ne sortait pas du cercle étroit de la famille impériale et dont Stolypine ne sut jamais rien, ce qui lui rendit incompréhensible et insupportable la présence de Raspoutine au Palais, Raspoutine dont il ignorait les pouvoirs de thaumaturge. L’eût-il su, il aurait sans doute agi autrement. Il se montrait avant tout soucieux de la réputation de la famille impériale, une réputation qui se dégradait avec la présence de Raspoutine considéré comme un débauché, une rumeur dont le bien-fondé n’a pas été établi. Quoiqu’il en soit, Stolypine était sensible à cette rumeur qui se répandait, et il chargea le colonel Guérassimov, responsable de l’Okhrana, de lui faire un rapport sur ce personnage, un rapport peu favorable qu’il présenta au tsar qui en prit connaissance sans lui donner suite et en continuant à taire la maladie de son fils. Stolypine prit alors la décision de faire éloigner Raspoutine de Saint-Pétersbourg, une mission qu’il confia au colonel Guérassimov. L’impératrice protesta mais le tsar refusa de désavouer son ministre ; et elle se mit à haïr Stolypine en qui elle vit celui privait son fils ce qui le maintenait en vie. Soirée du 14 septembre. Dmitri Bogrov prétexte un attentat en préparation dont il démasquera sur place les suspects, un coup de bluff. Ainsi obtient-il une invitation délivrée par l’Okhrana. Il atteint Stolypine sans peine, d’une balle dans la poitrine. Il mourra quatre jours plus tard, le 18. Dmitri Bogrov venait d’assassiner un homme qui s’était employé à alléger la législation contraignante qui pesait sur les Juifs de l’Empire.

Soirée du 14 septembre. Dmitri Bogrov prétexte un attentat en préparation dont il démasquera sur place les suspects, un coup de bluff. Ainsi obtient-il une invitation délivrée par l’Okhrana. Il atteint Stolypine sans peine, d’une balle dans la poitrine. Il mourra quatre jours plus tard, le 18. Dmitri Bogrov venait d’assassiner un homme qui s’était employé à alléger la législation contraignante qui pesait sur les Juifs de l’Empire.

The poor hapless people of Münster were now doomed totally. The bishop kept firing leaflets into the town promising a general amnesty if the people would only revolt and depose King Bockelson and his court and hand them over. To guard against such a threat, Bockelson stepped up his reign of terror still further. In early May, he divided the town into 12 sections, and placed a “duke” over each one with an armed force of 24 men. The dukes were foreigners like himself; as Dutch immigrants they were likely to be loyal to Bockelson. Each duke was strictly forbidden to leave his section, and the dukes, in turn, prohibited any meetings whatsoever of even a few people. No one was allowed to leave town, and any caught plotting to leave, helping anyone else to leave, or criticizing the king, was instantly beheaded, usually by King Bockelson himself. By mid-June such deeds were occurring daily, with the body often quartered and nailed up as a warning to the masses.

The poor hapless people of Münster were now doomed totally. The bishop kept firing leaflets into the town promising a general amnesty if the people would only revolt and depose King Bockelson and his court and hand them over. To guard against such a threat, Bockelson stepped up his reign of terror still further. In early May, he divided the town into 12 sections, and placed a “duke” over each one with an armed force of 24 men. The dukes were foreigners like himself; as Dutch immigrants they were likely to be loyal to Bockelson. Each duke was strictly forbidden to leave his section, and the dukes, in turn, prohibited any meetings whatsoever of even a few people. No one was allowed to leave town, and any caught plotting to leave, helping anyone else to leave, or criticizing the king, was instantly beheaded, usually by King Bockelson himself. By mid-June such deeds were occurring daily, with the body often quartered and nailed up as a warning to the masses.

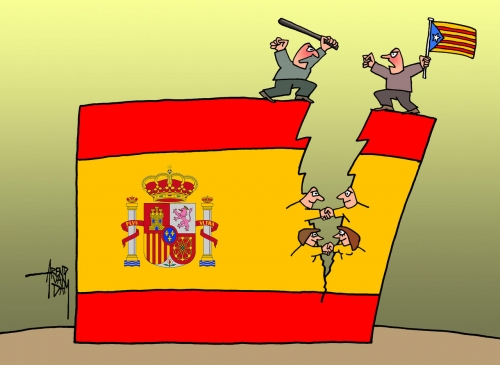

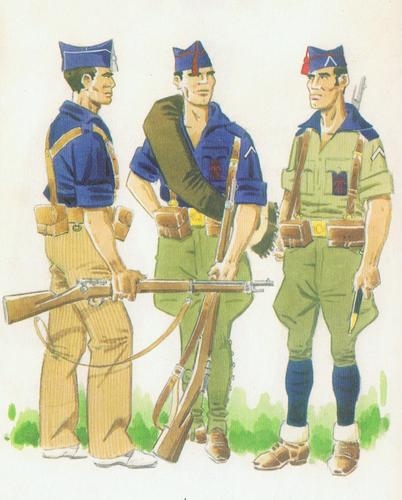

Les républicains comme les nationalistes tentent de rallier les différents pays européens à leur cause respective. En France, les élections du 3 mai 1936 ont porté au pouvoir une coalition de partis de gauche. Le Front populaire répond, d’abord dans un premier temps, favorablement à la demande de son homologue espagnol avant de faire machine arrière devant la forte opposition de droite qui oscille du côté des nationalistes conduit par le général Francisco Bahamonde y Franco. Parmi les partisans de ce général entré en sédition, le mouvement monarchiste Action française (AF) de Charles Maurras. Son organe de presse éponyme lance une virulente attaque dans ses colonnes contre les républicains et lance des appels aux dons.

Les républicains comme les nationalistes tentent de rallier les différents pays européens à leur cause respective. En France, les élections du 3 mai 1936 ont porté au pouvoir une coalition de partis de gauche. Le Front populaire répond, d’abord dans un premier temps, favorablement à la demande de son homologue espagnol avant de faire machine arrière devant la forte opposition de droite qui oscille du côté des nationalistes conduit par le général Francisco Bahamonde y Franco. Parmi les partisans de ce général entré en sédition, le mouvement monarchiste Action française (AF) de Charles Maurras. Son organe de presse éponyme lance une virulente attaque dans ses colonnes contre les républicains et lance des appels aux dons. Si d’autres officiers marquent la vie de cette brigade de volontaires monarchistes, tel que le général (cagoulard) Lavigne-Delville (1866-1957), elle n’échappe aux dissensions internes. Chaque groupe nationaliste tentant de s’approprier un leadership à peine reconnu par l’état-major franquiste, quelque peu agacé par l’esprit gaulois de ces volontaires qui s’entendent que trop avec les requetés carlistes. Si ces « légitimistes espagnols » ont rallié le général Franco c’est autant par haine de la république qu’ils entendent restaurer la monarchie au profit du prince Charles –Alphonse de Bourbon. Franco se méfie de ces monarchistes traditionalistes mais ne peut « se payer le luxe » de s’en séparer. Le prétendant carliste est aussi un roi de France (Charles XII) pour la minorité légitimiste française présente au sein de ces volontaires. Face aux camelots du roi, ceux que l’on surnomme les « aplhonsistes » se distinguent par le port du béret vert que l’on retrouve chez les monarchistes de la Rénovation espagnole. Un soutien logique attendu quand on sait que légitimistes français et carlistes partageaient les mêmes convictions et que ces deux groupes s’étaient retrouvés sur les mêmes champs de batailles lors des 3 guerres carlistes qui mèneront un de leur champion (don Carlos VII ou Charles XI) sur un éphémère trône d’Espagne à la fin du XIXème siècle.

Si d’autres officiers marquent la vie de cette brigade de volontaires monarchistes, tel que le général (cagoulard) Lavigne-Delville (1866-1957), elle n’échappe aux dissensions internes. Chaque groupe nationaliste tentant de s’approprier un leadership à peine reconnu par l’état-major franquiste, quelque peu agacé par l’esprit gaulois de ces volontaires qui s’entendent que trop avec les requetés carlistes. Si ces « légitimistes espagnols » ont rallié le général Franco c’est autant par haine de la république qu’ils entendent restaurer la monarchie au profit du prince Charles –Alphonse de Bourbon. Franco se méfie de ces monarchistes traditionalistes mais ne peut « se payer le luxe » de s’en séparer. Le prétendant carliste est aussi un roi de France (Charles XII) pour la minorité légitimiste française présente au sein de ces volontaires. Face aux camelots du roi, ceux que l’on surnomme les « aplhonsistes » se distinguent par le port du béret vert que l’on retrouve chez les monarchistes de la Rénovation espagnole. Un soutien logique attendu quand on sait que légitimistes français et carlistes partageaient les mêmes convictions et que ces deux groupes s’étaient retrouvés sur les mêmes champs de batailles lors des 3 guerres carlistes qui mèneront un de leur champion (don Carlos VII ou Charles XI) sur un éphémère trône d’Espagne à la fin du XIXème siècle.

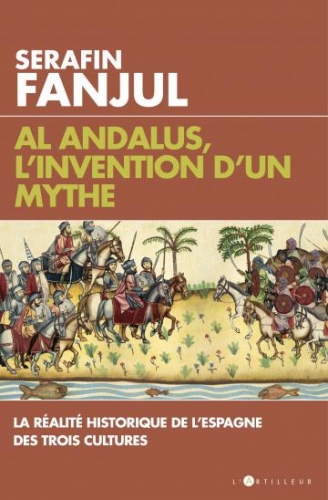

Lo de ser o no un «arabista» es una cuestión de perspectiva y de lo que queramos indicar con la palabra. En la actualidad, cualquier licenciado al que un periódico encarga un comentario ya se considera tal y arabista era don Emilio García Gómez que dedicó toda su larga vida a los estudios árabes. Si no se utiliza como una condecoración o signo distintivo especialísimo, sino como lo que debe ser, una mera descripción, sí creo que soy bastante arabista, aunque no le otorgue mayor importancia a esta clase de catalogaciones. Sí rechazo algo que se está haciendo mucho ahora y es afirmar «los arabistas dicen esto o aquello» sobre el tema que sea. Ni hay opiniones unánimes ni es deseable que las haya. Bien es cierto que no faltan quienes pretenden pastorearnos de un modo más bien ridículo enviándonos –sobre todo por emilio– comunicados, condenas y declaraciones retóricas contra Israel, Estados Unidos o José Mª Aznar para que manifestemos nuestra fervorosa adhesión a las tonterías que se les ocurren, tonterías –además– nada inocentes ni desinteresadas.

Lo de ser o no un «arabista» es una cuestión de perspectiva y de lo que queramos indicar con la palabra. En la actualidad, cualquier licenciado al que un periódico encarga un comentario ya se considera tal y arabista era don Emilio García Gómez que dedicó toda su larga vida a los estudios árabes. Si no se utiliza como una condecoración o signo distintivo especialísimo, sino como lo que debe ser, una mera descripción, sí creo que soy bastante arabista, aunque no le otorgue mayor importancia a esta clase de catalogaciones. Sí rechazo algo que se está haciendo mucho ahora y es afirmar «los arabistas dicen esto o aquello» sobre el tema que sea. Ni hay opiniones unánimes ni es deseable que las haya. Bien es cierto que no faltan quienes pretenden pastorearnos de un modo más bien ridículo enviándonos –sobre todo por emilio– comunicados, condenas y declaraciones retóricas contra Israel, Estados Unidos o José Mª Aznar para que manifestemos nuestra fervorosa adhesión a las tonterías que se les ocurren, tonterías –además– nada inocentes ni desinteresadas. No voy a exponer aquí el contenido de ese capítulo dedicado a los moriscos en América: es excesivamente largo. Pero sí puedo aclarar que mis conclusiones, después de dos años de trabajo (para un solo capítulo) son difíciles de modificar. La presencia de moriscos es irrelevante, aunque las comunidades árabes de América y los siempre temibles divulgadores se apliquen a repetir lo contrario por tierra, mar y aire. Sin probar nada, claro. Como «se sabe que fue así» no hay que demostrar nada.

No voy a exponer aquí el contenido de ese capítulo dedicado a los moriscos en América: es excesivamente largo. Pero sí puedo aclarar que mis conclusiones, después de dos años de trabajo (para un solo capítulo) son difíciles de modificar. La presencia de moriscos es irrelevante, aunque las comunidades árabes de América y los siempre temibles divulgadores se apliquen a repetir lo contrario por tierra, mar y aire. Sin probar nada, claro. Como «se sabe que fue así» no hay que demostrar nada. «Islam» en árabe significa «sumisión». Pertenece a la misma raíz verbal de «paz», pero significa sumisión. Contar otra cosa es salirse por peteneras. «Yihad» significa, sobre todo y antes que nada, «guerra santa o combate por la fe», como se prefiera. También vale lo de las peteneras.

«Islam» en árabe significa «sumisión». Pertenece a la misma raíz verbal de «paz», pero significa sumisión. Contar otra cosa es salirse por peteneras. «Yihad» significa, sobre todo y antes que nada, «guerra santa o combate por la fe», como se prefiera. También vale lo de las peteneras.