Galvanisée par la dégradation progressive de ses relations avec l’Occident à la suite de son action en Ukraine et en Syrie, la Russie de Vladimir Poutine a toujours voulu voir en la Chine un partenaire “alternatif” sur lequel elle pourrait s’appuyer, à la fois sur les plans économique et international. Cette ambition se heurte toutefois très souvent à la réalité des objectifs de Pékin, dont les dirigeants n’ont jamais été particulièrement enthousiasmés par le concept d’un bloc anti-occidental au sens strict du terme. Les notions de “partenariat stratégique” ou même d’“alliance”, si elles sont devenues très à la mode dans les dîners mondains, ne recouvrent donc que très imparfaitement la logique du fait sino-russe.

Nous vous proposons cette analyse des relations sino-russes en deux parties, voici la première.

« Nous ne sommes ni de l’Orient, ni de l’Occident », concluait sur un ton particulièrement pessimiste le philosophe russe Tchaadaïev dans l’une de ses plus célèbres Lettres philosophiques. Principal précurseur du bouillonnement intellectuel de la Russie impériale de la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle, celui-ci fut l’un des premiers à théoriser l’idée d’une spécificité russe qui justifierait le fait qu’elle n’ait d’autre choix que de s’appuyer sur deux “béquilles”, dont l’une serait occidentale et l’autre orientale. Comme si le génie politique et industriel de l’Europe ne pouvait qu’être associé avec la créativité et la rationalité organisatrice de la Chine, qui partageait déjà avec la Russie la problématique de l’immensité du territoire et de sa bonne administration. Peine perdue pour Tchaadaïev, qui considérait que nul espoir n’était permis tant que le pays resterait engoncé dans l’archaïsme des tsars indignes de l’œuvre de Pierre le Grand, alors même que la Russie ne connaissait pas encore la violence anarchiste qui marquera la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle. Dans Apologie d’un fou, publié en 1837, il écrit et se désole : « Situés entre les deux grandes divisions du monde, entre l’Orient et l’Occident, nous appuyant d’un coude sur la Chine et de l’autre sur l’Allemagne, nous devrions réunir en nous les deux grands principes de la nature intelligente, l’imagination et la raison, et joindre dans notre civilisation les histoires du globe entier. Ce n’est point-là le rôle que la Providence nous a départi. »

« Nous ne sommes ni de l’Orient, ni de l’Occident », concluait sur un ton particulièrement pessimiste le philosophe russe Tchaadaïev dans l’une de ses plus célèbres Lettres philosophiques. Principal précurseur du bouillonnement intellectuel de la Russie impériale de la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle, celui-ci fut l’un des premiers à théoriser l’idée d’une spécificité russe qui justifierait le fait qu’elle n’ait d’autre choix que de s’appuyer sur deux “béquilles”, dont l’une serait occidentale et l’autre orientale. Comme si le génie politique et industriel de l’Europe ne pouvait qu’être associé avec la créativité et la rationalité organisatrice de la Chine, qui partageait déjà avec la Russie la problématique de l’immensité du territoire et de sa bonne administration. Peine perdue pour Tchaadaïev, qui considérait que nul espoir n’était permis tant que le pays resterait engoncé dans l’archaïsme des tsars indignes de l’œuvre de Pierre le Grand, alors même que la Russie ne connaissait pas encore la violence anarchiste qui marquera la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle. Dans Apologie d’un fou, publié en 1837, il écrit et se désole : « Situés entre les deux grandes divisions du monde, entre l’Orient et l’Occident, nous appuyant d’un coude sur la Chine et de l’autre sur l’Allemagne, nous devrions réunir en nous les deux grands principes de la nature intelligente, l’imagination et la raison, et joindre dans notre civilisation les histoires du globe entier. Ce n’est point-là le rôle que la Providence nous a départi. »

De manière générale, la prophétie de Tchaadaïev s’est confirmée. L’équilibre qu’il appelait de ses vœux n’a jamais pu être trouvé, en particulier dans les relations de la Russie avec la Chine. Lorsque l’on “efface” le relief donné par la perspective historique, on a en effet tendance à voir dominer l’image d’un rapprochement constant et inexorable entre Moscou et Pékin, dont l’alliance servirait de contrepoids dans un monde dominé par la vision occidentale des relations internationales. Cette impression s’est particulièrement renforcée avec le discours de Vladimir Poutine donné à la 43e conférence de la sécurité de Munich en 2007, où ce dernier fustigea l’unilatéralisme qui avait présidé au déclenchement de la guerre en Irak en 2003 ainsi que le projet de bouclier antimissile prévu par l’Otan en Europe orientale. Ce serait toutefois négliger le fait que le premier mandat du président russe (2000-2004) fut marqué par un mouvement marqué d’affinité avec l’Occident, à tel point qu’il fut l’un des premiers à contacter George W. Bush à la suite du 11 septembre 2001 pour l’assurer de son soutien. Ce serait aussi oublier hâtivement que la relation sino-russe fut dominée pendant cinq siècles par l’importance des litiges territoriaux et que la Guerre froide fut pour les deux pays un théâtre d’affrontement pour le leadership du camp socialiste, ce qui annihila toute perspective d’un bloc unifié.

Cinq siècles de conflictualité

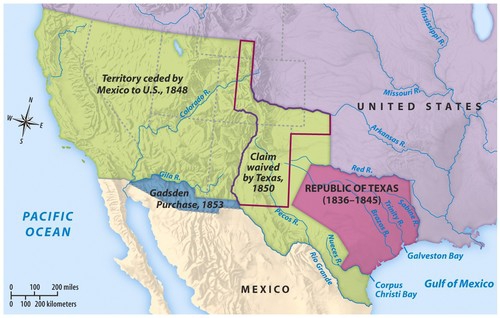

Si elles semblent très éloignées de par la langue et la culture, la Russie et la Chine ont toutefois toujours eu en commun de partager une réalité géographique similaire, dont l’immensité du territoire est la pierre angulaire. Une proximité également traduite dans les institutions, le modèle impérial historiquement développé par les deux pays ayant constitué un facteur favorable à une tradition administrative très fortement centralisatrice. Il y a aussi la question de la diaspora, particulièrement prégnante pour Moscou comme pour Pékin, avec 25 millions de Russes en dehors des frontières – principalement dans les anciens États de l’Union soviétique – et 20 millions de Chinois sur la seule île de Taïwan. Des nationaux “du dehors” souvent considérés comme des compatriotes perdus qu’il conviendrait a minima de protéger, et au mieux de faire revenir dans l’escarcelle nationale. Il y a enfin cette immense frontière commune de 4250 km qui s’étend de la Mongolie jusqu’aux rives de l’océan Pacifique, et dont la définition exacte n’a, jusqu’à récemment, jamais été arrêtée.

Mais le véritable rapprochement entre les deux pays ne s’imposera qu’à la faveur de la proximité idéologique offerte par les effets conjugués de la révolution russe d’octobre 1917 et de la prise de pouvoir du Parti communiste chinois (PCC) emmené par la figure emblématique de Mao Zedong en 1949. Le 14 février 1950, un premier traité d’amitié, d’alliance et d’assistance mutuelle est signé entre les deux États. L’URSS de Staline, auréolée de l’immense prestige de sa victoire sur l’Allemagne nazie en 1945 et forte d’un important savoir-faire en matière industrielle, envoie dans ce cadre plus de 10 000 ingénieurs en Chine afin de former le personnel local. Malgré la divergence fondamentale avec les conceptions économiques de Mao Zedong, qui privilégiait le développement agraire massif et pas l’industrie lourde, cette coopération se poursuit jusqu’au milieu des années 1950. Portée par l’espoir de Moscou de pouvoir constituer avec la Chine un grand bloc socialiste qui lui permettrait de peser de manière plus importante sur les affaires internationales, cette politique se heurte toutefois à la dégradation progressive des relations entre les deux pays. Ces discordances croissantes sont, en grande partie, liées au refus de Nikita Khrouchtchev de transférer la technologie nucléaire au régime chinois, à la publication du rapport portant son nom sur les crimes du stalinisme et à son choix de dialoguer régulièrement avec Washington dans le cadre de la “coexistence pacifique”, une véritable hérésie conceptuelle pour un Mao Zedong resté très attaché à l’orthodoxie marxiste-léniniste.

La rupture est finalement consommée entre 1961 et 1962, notamment après une gestion de la crise des missiles de Cuba jugée calamiteuse par Pékin. Dans la conception maoïste, la Chine possédait une légitimité au moins équivalente à celle de l’URSS pour assurer le leadership du camp socialiste. C’est la raison pour laquelle le pays chercha à se détacher du grand-frère soviétique en dégageant une voie qui lui était spécifique. En ce sens, la Chine est incontestablement parvenue à certains résultats : obtention de l’arme nucléaire en 1964, reconnaissance par la France la même année et admission au Conseil de sécurité de l’Onu en 1971, en lieu et place de Taïwan. Elle développe dans ce cadre la doctrine du “tiers-mondisme” afin de concurrencer Moscou dans le soutien aux États attirés par l’idéologie marxiste, politique dont Pékin tirera bien peu de fruits puisque seule l’Albanie d’Enver Hoxha finira par s’y rallier à la faveur de la rupture avec l’Union soviétique en 1961.

Un pic de tension avec l’URSS est atteint en 1969, lorsque l’Armée rouge et l’Armée populaire de libération s’affrontent à l’occasion de plusieurs escarmouches aux abords du fleuve Amour, sur l’affluent de l’Oussouri. Si l’enjeu tient dans le contrôle de l’île de Damanski (Zhenbao en mandarin), ces incidents illustrent principalement le problème plus large des différends frontaliers entre les deux pays, abordés plusieurs fois par la voie des traités, mais jamais véritablement réglés et toujours présents à l’esprit des deux parties.

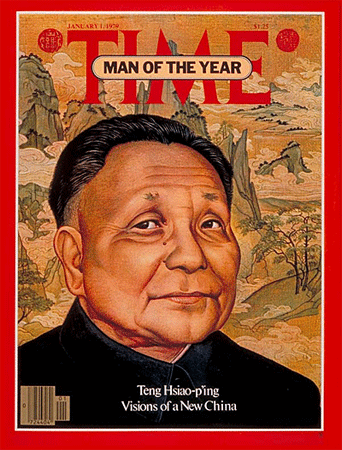

Seule la mort de Mao Zedong en 1976, qui entraînera en Chine un certain recul de l’impératif de “pureté marxiste”, permettra d’engager un premier rapprochement. Son successeur, Deng Xiaoping, a longtemps été considéré comme un acteur majeur de la réconciliation sino-soviétique, dans un contexte où le traité d’amitié signé en 1950 était sur le point d’expirer (en 1979). Mais le Deng Xiaoping “réconciliateur” des années 1980 fut aussin aux côtés de Mao, l’un des plus solides partisans de la “ligne dure” face au révisionnisme soviétique initié par Khrouchtchev. Il définira même, en 1979, l’URSS comme « l’adversaire le plus résolu de la République populaire de Chine », avant même les États-Unis. Deng Xiaoping posa donc trois préalables au rapprochement avec Moscou : le retrait des divisions de l’Armée rouge encore stationnées en Mongolie, l’arrêt du soutien soviétique aux opérations militaires que le Vietnam menait au Cambodge depuis 1977 et le démantèlement de toutes les bases militaires situées dans les pays avoisinants la Chine. S’il s’éloigna radicalement du maximalisme de Mao Zedong, il prouva en revanche que la logique de blocs ou le suivisme idéologique n’avaient rien d’automatique dans un contexte où l’URSS redoublait d’activité sur la scène internationale. L’invasion de l’Afghanistan initiée en 1979 par la Russie a d’ailleurs mis fin à ces premières négociations. Cette situation n’a guère connu d’amélioration dans une Union soviétique minée par des difficultés économiques structurelles et une forte instabilité politique interne, avec une première moitié des années 1980 où se succèdent pas moins de quatre dirigeants différents (Brejnev, Andropov, Tchernenko et Gorbatchev). Seul le retrait partiel d’Afghanistan, initié en 1986, permettra d’ouvrir la voie à ce qui constitue le véritable tournant du rapprochement sino-russe : la “parenthèse Eltsine” dans les années 1990.

Seule la mort de Mao Zedong en 1976, qui entraînera en Chine un certain recul de l’impératif de “pureté marxiste”, permettra d’engager un premier rapprochement. Son successeur, Deng Xiaoping, a longtemps été considéré comme un acteur majeur de la réconciliation sino-soviétique, dans un contexte où le traité d’amitié signé en 1950 était sur le point d’expirer (en 1979). Mais le Deng Xiaoping “réconciliateur” des années 1980 fut aussin aux côtés de Mao, l’un des plus solides partisans de la “ligne dure” face au révisionnisme soviétique initié par Khrouchtchev. Il définira même, en 1979, l’URSS comme « l’adversaire le plus résolu de la République populaire de Chine », avant même les États-Unis. Deng Xiaoping posa donc trois préalables au rapprochement avec Moscou : le retrait des divisions de l’Armée rouge encore stationnées en Mongolie, l’arrêt du soutien soviétique aux opérations militaires que le Vietnam menait au Cambodge depuis 1977 et le démantèlement de toutes les bases militaires situées dans les pays avoisinants la Chine. S’il s’éloigna radicalement du maximalisme de Mao Zedong, il prouva en revanche que la logique de blocs ou le suivisme idéologique n’avaient rien d’automatique dans un contexte où l’URSS redoublait d’activité sur la scène internationale. L’invasion de l’Afghanistan initiée en 1979 par la Russie a d’ailleurs mis fin à ces premières négociations. Cette situation n’a guère connu d’amélioration dans une Union soviétique minée par des difficultés économiques structurelles et une forte instabilité politique interne, avec une première moitié des années 1980 où se succèdent pas moins de quatre dirigeants différents (Brejnev, Andropov, Tchernenko et Gorbatchev). Seul le retrait partiel d’Afghanistan, initié en 1986, permettra d’ouvrir la voie à ce qui constitue le véritable tournant du rapprochement sino-russe : la “parenthèse Eltsine” dans les années 1990.

D’un partenariat constructif à une alliance stratégique

Paradoxalement, la chute de l’URSS en 1991 et l’émergence d’une Fédération de Russie la même année ne constituent pas – du moins dans un premier temps – un facteur de rapprochement avec la Chine. Dans son choix d’une rupture radicale avec un passé soviétique dont le deuil ne sera jamais véritablement fait par la population russe, Boris Eltsine s’appuie sur de jeunes cadres formés dans les années 1980. C’est par exemple le cas de Boris Nemtsov, dont l’assassinat à Moscou le 25 février 2015 a fait grand bruit, en Russie comme dans les médias occidentaux. Sous le patronage du Ministre de l’économie Iegor Gaïdar, ces nouveaux cadres résolument libéraux conduisent la Russie à opérer dans un premier temps un certain alignement sur la politique de l’Union européenne et des États-Unis, dans la continuité des choix effectués par Mikhaïl Gorbatchev pendant la Guerre du Golfe. Autant d’éléments qui ne laisseront qu’une place limitée à une politique ambitieuse de rapprochement avec la Chine, alors que celle-ci cherchait dans le même temps à améliorer ses relations avec Washington, considérablement dégradées par la question latente de Taïwan et la répression des manifestations de la place Tian’anmen en 1989.

Il est assez coutumier de désigner Vladimir Poutine, arrivé au pouvoir en 2000 mais dont l’ascension a été permise par Boris Eltsine, comme l’artisan fondateur du repositionnement russe dans la politique internationale, et en particulier du rapprochement avec la Chine. Il serait toutefois plus juste d’attribuer ce rôle au Ministre des affaires étrangères nommé par Eltsine en 1996, Evgueni Primakov. Brillant arabisant et ancien officier des services de renseignement soviétiques, il se distingua par une saille restée célèbre dans le pays : « la Russie doit marcher sur ses deux jambes ». Il s’agissait déjà d’une référence – massivement réutilisée par la suite par Vladimir Poutine – au positionnement central occupé par la Russie dans l’espace eurasiatique, mais aussi à cette “particularité” chère à Tchaadaïev et dont elle devrait user afin de poursuivre la voie qui est la sienne. Le rapprochement avec Pékin apparaissait alors comme une évidence dans un contexte où l’économie russe était minée par le choc brutal des privatisations impulsées par Iegor Gaïdar, tandis que le gouvernement et les autorités militaires subissaient l’humiliation de leur défaite dans la Première guerre de Tchétchénie.

Il est assez coutumier de désigner Vladimir Poutine, arrivé au pouvoir en 2000 mais dont l’ascension a été permise par Boris Eltsine, comme l’artisan fondateur du repositionnement russe dans la politique internationale, et en particulier du rapprochement avec la Chine. Il serait toutefois plus juste d’attribuer ce rôle au Ministre des affaires étrangères nommé par Eltsine en 1996, Evgueni Primakov. Brillant arabisant et ancien officier des services de renseignement soviétiques, il se distingua par une saille restée célèbre dans le pays : « la Russie doit marcher sur ses deux jambes ». Il s’agissait déjà d’une référence – massivement réutilisée par la suite par Vladimir Poutine – au positionnement central occupé par la Russie dans l’espace eurasiatique, mais aussi à cette “particularité” chère à Tchaadaïev et dont elle devrait user afin de poursuivre la voie qui est la sienne. Le rapprochement avec Pékin apparaissait alors comme une évidence dans un contexte où l’économie russe était minée par le choc brutal des privatisations impulsées par Iegor Gaïdar, tandis que le gouvernement et les autorités militaires subissaient l’humiliation de leur défaite dans la Première guerre de Tchétchénie.

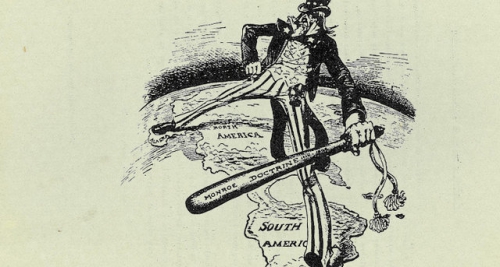

Du côté chinois, le nouveau président Jiang Zeming cherchait quant à lui à construire pour la Chine une stature à sa mesure sur le plan international, alors que le pays se trouvait encore sous le coup de plusieurs sanctions européennes et américaines en réponse aux évènements de la place Tian’anmen. Sur le plan régional, les autorités chinoises se trouvaient de plus en plus préoccupées par le “pivot Pacifique” engagé par les États-Unis au milieu des années 1990, et qui avait conduit Washington à intervenir militairement dans la crise de Taïwan en 1995 ou encore à se rapprocher de son allié japonais.

Pour les deux pays, les conditions du rapprochement étaient donc assez largement réunies, ce qui aboutira à la signature par Boris Eltsine et Jiang Zeming d’un premier partenariat en avril 1996. Il est d’ailleurs très intéressant d’observer le subtil changement sémantique opéré par la diplomatie russe dans la définition de sa relation avec Pékin : qualifié dans la première moitié des années 1990 de « partenariat constructif » (« konstrouktivnoyé partnerstvo »), le lien avec la Chine est désormais défini comme un « partenariat stratégique » (« strategitcheskoyé partnerstvo »), une formule nettement plus offensive proposée par Evgueni Primakov, qui s’inscrit dans une certaine stratégie de communication vis-à-vis des autres partenaires de la Russie. Ce qui commence déjà à prédominer, c’est bien la nécessité d’une certaine convergence pratique dans la gestion des relations internationales, ce qui sera confirmé par la déclaration conjointe sino-russe de 1997, conçue pour compléter le partenariat de 1996. On y retrouve avec intérêt tous les éléments de langage qui sont encore aujourd’hui utilisés par Pékin et Moscou dans leur traitement des affaires internationales : « nécessité d’un monde multipolaire », « refus de l’hégémonie », « primauté du droit et de la coopération entre les peuples », « non-intervention et respect de la souveraineté nationale »… La “multipolarité” en particulier est ainsi transformée en un quasi-slogan de principe pour Moscou, qui y voyait un concept efficace pour contester la prééminence américaine dans la limite des moyens dont disposait le Kremlin dans les années 1990.

La gestion du dossier particulièrement complexe de la Yougoslavie ne fait qu’accentuer ce sentiment de dépossession et d’impuissance. La Russie se révèle incapable de soutenir son alliée serbe en empêchant une intervention militaire de l’Otan au Kosovo entre mars 1998 et juin 1999. Pékin comme Moscou adopteront par ailleurs une position similaire sur le dossier, l’action de l’Alliance atlantique en Serbie étant perçue comme une atteinte au principe de souveraineté nationale orchestrée avec un contournement du système décisionnel du Conseil de Sécurité de l’Onu – l’opération fut effectivement déclenchée sans mandat. Même à quinze ans d’intervalle, le précédent du Kosovo continue de résonner – à tort ou à raison – pour Pékin et Moscou comme la preuve indéniable que le système de concertation offert par l’Onu est vicié dans son principe même.

Cette idée justifie un rapprochement des deux capitales sur des questions plus sensibles liées à la sécurité régionale et internationale, déjà engagée par la réunion des “Shanghai Five” en 1996 (Chine, Russie, Kirghizstan, Kazakhstan, Tadjikistan). Même l’institution militaire russe, encore très imprégnée par un personnel majoritairement issu de l’establishment soviétique et très conservatrice vis-à-vis du secret industriel, accepte des transferts de technologies militaires de plus en plus nombreux en direction de Pékin. Ce choix ne fut d’ailleurs pas uniquement pris pour des raisons purement politiques : il a été rendu impérativement nécessaire par le délitement complet du complexe militaro-industriel russe et par la perte de ses principaux clients en Europe centrale et orientale (Allemagne de l’Est, Hongrie, Tchécoslovaquie, Bulgarie, Roumanie, Pologne, etc.). La Chine s’est alors rapidement imposée comme un débouché naturel, en particulier pour une industrie de l’armement dont le revenu reposait à 80 % sur les recettes des exportations d’armes.

À l’échelle de l’histoire longue, le rapprochement sino-russe pourrait donc être considéré comme un épiphénomène, particulièrement lorsque l’on sait l’importance des litiges territoriaux qui ont régulièrement empoisonné les relations entre les deux pays, de même que leur lutte acharnée pour l’hégémonie sur le camp socialiste durant la Guerre froide. La rapidité de l’évolution du monde après la chute de l’empire soviétique – que presque aucune âme n’avait été capable de prédire – a favorisé un rapprochement devenu non pas naturel, mais légitime pour deux pays dont les intérêts géopolitiques et la conception antilibérale des relations internationales constituent, en apparence au moins, les deux piliers d’une relation potentiellement “stratégique”. La Russie de Vladimir Poutine, très largement enfantée par celle de Boris Eltsine, exploitera ainsi cet héritage et tentera – avec un succès parfois assez largement contestable – d’en faire un des principaux vecteurs de son “retour” sur la scène internationale.

Nos Desserts :

- L’importance historique des “traités inégaux » dans la relation de la Chine à la Russie

- Comprendre pourquoi et comment l’Otan ne prépare pas la paix avec la Russie avec Le Monde diplomatique

- Le rapprochement sino-russe vu par Le Monde

- La rupture de l’Albanie avec l’Union soviétique a été magnifiquement contée dans le roman d’Ismaïl Kadaré, L’Hiver de la grande solitude

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Frederick asserts that laws should aim to promote “[g]ood manners and public safety.” He is enormously concerned with civil peace, saying French chancellor Michel de l’Hôpital’s efforts to increase tolerance and defuse tensions between Catholics and Protestants during the Wars of Religion “worked for the salvation of the fatherland.” Laws may deal with politics (government), manners (criminal), and civil matters (contracts, usury).

Frederick asserts that laws should aim to promote “[g]ood manners and public safety.” He is enormously concerned with civil peace, saying French chancellor Michel de l’Hôpital’s efforts to increase tolerance and defuse tensions between Catholics and Protestants during the Wars of Religion “worked for the salvation of the fatherland.” Laws may deal with politics (government), manners (criminal), and civil matters (contracts, usury).

Frederick’s advocacy of paternal authority is all the more poignant and significant in that his own father, Frederick-William, also known as the Soldier King, had been a harsh one. Frederick-William had often beaten his son and executed before Frederick’s eyes his youthful best friend (and possible lover), Hans von Katte, for “desertion.”

Frederick’s advocacy of paternal authority is all the more poignant and significant in that his own father, Frederick-William, also known as the Soldier King, had been a harsh one. Frederick-William had often beaten his son and executed before Frederick’s eyes his youthful best friend (and possible lover), Hans von Katte, for “desertion.”

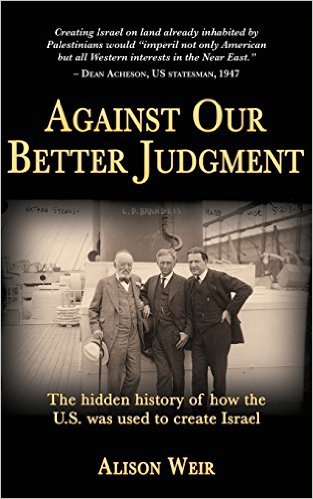

Alison Weir's relatively short book covers the history of Zionism in the United States from the last decades of the 19th century until the creation of the state of Israel in 1948. (She is working on a second volume that will carry this history to the present.) Its brevity does not mean, however, that it is in any sense superficial, as it brings out key historical information, all well-documented, that sets the stage for the troubled world in which we now live. While histories of Zionism have usually focused on Europe, Weir shows that American adherents of this ideology have been far more important than generally has been recognized

Alison Weir's relatively short book covers the history of Zionism in the United States from the last decades of the 19th century until the creation of the state of Israel in 1948. (She is working on a second volume that will carry this history to the present.) Its brevity does not mean, however, that it is in any sense superficial, as it brings out key historical information, all well-documented, that sets the stage for the troubled world in which we now live. While histories of Zionism have usually focused on Europe, Weir shows that American adherents of this ideology have been far more important than generally has been recognized Kallen was regarded by some as first promoting the idea for what became the Balfour Declaration, which would set the stage for the modern state of Israel. He promoted this scheme in 1915 when the U.S. was still a neutral. He told a British friend that this would serve to bring the United States into World War I. It should be pointed out that at that time, despite serious diplomatic issues regarding German submarine warfare, the great majority of the American people wanted to avoid war and Wilson would be re-elected president in November 1916 on the slogan “He kept us out of war.” Kallen’s idea for advancing the Zionist goal, however, soon gained traction.

Kallen was regarded by some as first promoting the idea for what became the Balfour Declaration, which would set the stage for the modern state of Israel. He promoted this scheme in 1915 when the U.S. was still a neutral. He told a British friend that this would serve to bring the United States into World War I. It should be pointed out that at that time, despite serious diplomatic issues regarding German submarine warfare, the great majority of the American people wanted to avoid war and Wilson would be re-elected president in November 1916 on the slogan “He kept us out of war.” Kallen’s idea for advancing the Zionist goal, however, soon gained traction. Although Segev is a daring historian who often rejects the Zionist myths on the creation of Israel, in this case he essentially relies on a classic Zionist-constructed strawman, which involves greatly exaggerating the view that the Zionists (and Jews in general) don’t like. It is highly doubtful that the British foreign office believed that Jews were so powerful as to be “turning the wheels of history.” (If that had been the case, one would think that the British would have offered Jews much more than Palestine from the very start of the war.) Furthermore, as noted earlier, Weir does not subscribe to anything like this Zionist strawman in regard to the Balfour Declaration, or anything else, I should add.

Although Segev is a daring historian who often rejects the Zionist myths on the creation of Israel, in this case he essentially relies on a classic Zionist-constructed strawman, which involves greatly exaggerating the view that the Zionists (and Jews in general) don’t like. It is highly doubtful that the British foreign office believed that Jews were so powerful as to be “turning the wheels of history.” (If that had been the case, one would think that the British would have offered Jews much more than Palestine from the very start of the war.) Furthermore, as noted earlier, Weir does not subscribe to anything like this Zionist strawman in regard to the Balfour Declaration, or anything else, I should add.

One minor criticism here is that the reader might incorrectly get the impression that the King-Crane Commission dealt solely with Palestine, while it actually involved all the territories severed from, or expected to be severed from, the Ottoman Empire (Turkey).

One minor criticism here is that the reader might incorrectly get the impression that the King-Crane Commission dealt solely with Palestine, while it actually involved all the territories severed from, or expected to be severed from, the Ottoman Empire (Turkey).

A quick aside here: somewhat ironically, in my view, Weir barely touches on the United States decision to recognize Israel. Moreover, what does exist is largely in the endnotes. Although there will be a second volume to Weir’s history, and the cut-off point for this volume has to be somewhere, still the fact that the book does make reference to events in 1948 would seem to have made it appropriate to discuss in some detail the issue of America’s quick recognition of Israel.

A quick aside here: somewhat ironically, in my view, Weir barely touches on the United States decision to recognize Israel. Moreover, what does exist is largely in the endnotes. Although there will be a second volume to Weir’s history, and the cut-off point for this volume has to be somewhere, still the fact that the book does make reference to events in 1948 would seem to have made it appropriate to discuss in some detail the issue of America’s quick recognition of Israel. Weir includes a brief reference to Leon Uris’s bestselling 1958 novel on the Exodus ship, and though it falls outside the chronological purview of this volume, I would add that the impact of the already mythologized Exodus event was greatly magnified by Uris’s book, which sold over 7 million copies and was turned into a blockbuster movie in 1960 by Otto Preminger, a leading film director of the era. The film has been identified by many commentators as having greatly enhanced support for Israel in the United States by Jews as well as gentiles and in the view of some scholars this movie has had a lasting effect on how Americans view the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Weir even acknowledges that it had initially shaped her thinking on the subject.

Weir includes a brief reference to Leon Uris’s bestselling 1958 novel on the Exodus ship, and though it falls outside the chronological purview of this volume, I would add that the impact of the already mythologized Exodus event was greatly magnified by Uris’s book, which sold over 7 million copies and was turned into a blockbuster movie in 1960 by Otto Preminger, a leading film director of the era. The film has been identified by many commentators as having greatly enhanced support for Israel in the United States by Jews as well as gentiles and in the view of some scholars this movie has had a lasting effect on how Americans view the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Weir even acknowledges that it had initially shaped her thinking on the subject. In 1939, Time Magazine named Thompson the second most popular and influential woman in America behind Eleanor Roosevelt.

In 1939, Time Magazine named Thompson the second most popular and influential woman in America behind Eleanor Roosevelt.

Profondément européen, il prôna l’alliance de la France avec l’Angleterre et l’Allemagne, anticipant le temps des empires.

Profondément européen, il prôna l’alliance de la France avec l’Angleterre et l’Allemagne, anticipant le temps des empires.

In the West, the so-called “Roman Catholic Church” (another misnomer – there is nothing Roman or “catholic” – meaning “universal” – about the Papacy as it is Frankish and local) likes to present itself as the original Church whose roots and traditions go back to the Apostolic times. This is simply false. The reality is that the religion which calls itself “Roman Catholic” is a relatively new religion, younger than Islam by several centuries, which was born in the 11th century of a rejection of the key tenets of the 1000 year long Christian faith. Furthermore, from the moment of its birth, this religion has embarked on an endless cycle of innovations including the 19th century (!) dogmas of the Papal infallibility and the Immaculate Conception. Far from being conservative or traditionalists, the Latins have always been rabid innovators and modernists.

In the West, the so-called “Roman Catholic Church” (another misnomer – there is nothing Roman or “catholic” – meaning “universal” – about the Papacy as it is Frankish and local) likes to present itself as the original Church whose roots and traditions go back to the Apostolic times. This is simply false. The reality is that the religion which calls itself “Roman Catholic” is a relatively new religion, younger than Islam by several centuries, which was born in the 11th century of a rejection of the key tenets of the 1000 year long Christian faith. Furthermore, from the moment of its birth, this religion has embarked on an endless cycle of innovations including the 19th century (!) dogmas of the Papal infallibility and the Immaculate Conception. Far from being conservative or traditionalists, the Latins have always been rabid innovators and modernists. Regardless of the actual level of religiosity in Russia, Russia remains the objective historical and cultural heir to the Roman Empire: the First Rome fell in 476, the Second Rome fell in 1453 while the Third Rome fell in 1917.

Regardless of the actual level of religiosity in Russia, Russia remains the objective historical and cultural heir to the Roman Empire: the First Rome fell in 476, the Second Rome fell in 1453 while the Third Rome fell in 1917.

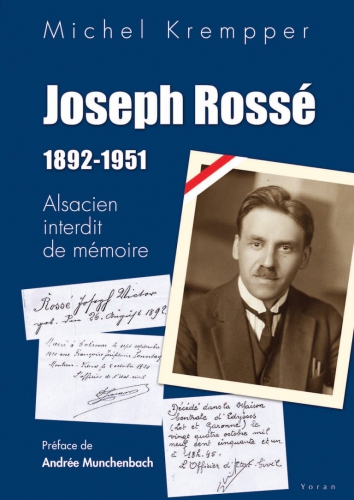

Mais de ses contacts avérés avec le colonel von Stauffenberg, le porteur de la bombe qui devait tuer le Führer le 20 juillet 1944, la justice politique de la Libération n’en tiendra nul compte. Il ne sera pas plus porté à sa décharge l’intense activité de Rossé pour venir en aide à ses compatriotes alsaciens victimes de l’hitlérisme ou pour éditer clandestinement les auteurs chrétiens interdits dans l’Allemagne nazie.

Mais de ses contacts avérés avec le colonel von Stauffenberg, le porteur de la bombe qui devait tuer le Führer le 20 juillet 1944, la justice politique de la Libération n’en tiendra nul compte. Il ne sera pas plus porté à sa décharge l’intense activité de Rossé pour venir en aide à ses compatriotes alsaciens victimes de l’hitlérisme ou pour éditer clandestinement les auteurs chrétiens interdits dans l’Allemagne nazie.

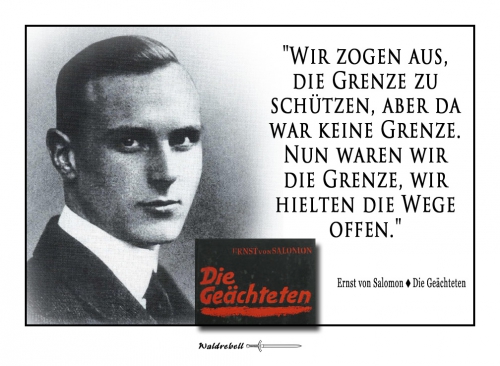

L’architecture générale du livre s’appuie sur les quelques 130 questions auxquelles les Américains demandèrent aux Allemands de répondre en 1945 afin d’organiser la dénazification du pays, mais en les détournant souvent et prenant à de nombreuses reprises le contre-pied des attentes des vainqueurs. A bien des égards, le livre est ainsi non seulement à contre-courant de la doxa habituelle, mais camoufle également bien des aspects d’une réalité que l’Allemagne de la fin des années 1940 refusait de reconnaître : « Ma conscience devenue très sensible me fait craindre de participer à un acte capable, dans ces circonstances incontrôlables, de nuire sur l’ordre de puissances étrangères à un pays et à un peuple dont je suis irrévocablement ». Certaines questions font l’objet de longs développements, mais presque systématiquement un humour grinçant y est présent, comme lorsqu’il s’agit simplement d’indiquer son lieu de naissance : « Je découvre avec étonnement que, grâce à mon lieu de naissance (Kiel), je peux me considérer comme un homme nordique, et l’idée qu’en comparaison avec ma situation les New-Yorkais doivent passer pour des Méridionaux pleins de tempérament m’amuse beaucoup ». Et à la même question, à propos des manifestations des SA dans la ville avant la prise du pouvoir par les nazis : « Certes, la couleur de leurs uniformes était affreuse, mais on ne regarde pas l’habit d’un homme, on regarde son coeur. On ne savait pas au juste ce que ces gens-là voulaient. Du moins semblaient-ils le vouloir avec fermeté … Ils avaient de l’élan, on était bien obligé de le reconnaître, et ils étaient merveilleusement organisés. Voilà ce qu’il nous fallait : élan et organisation ». Au fil des pages, il revient à plusieurs reprises sur son attachement à la Prusse traditionnelle, retrace l’histoire de sa famille, développe ses relations compliquées avec les religions et les Eglises, évoque des liens avec de nombreuses personnes juives (dont sa femme), donne de longues précisions sur ses motivations à l’époque de l’assassinat de Rathenau, sur son procès ultérieur et sur son séjour en prison. Suivant le fil des questions posées, il détaille son éducation, son cursus scolaire, son engagement dans les mouvements subversifs « secrets », retrace ses activités professionnelles successives avec un détachement qui parfois peu surprendre mais correspond à l’humour un peu grinçant qui irrigue le texte, comme lorsqu’il parle de son éditeur et ami Rowohlt. Il revient bien sûr longuement sur les corps francs entre 1919 et 1923, sur l’impossibilité à laquelle il se heurte au début de la Seconde guerre mondiale pour faire accepter son engagement volontaire, tout en racontant qu’il avait obtenu en 1919 la plus haute de ses neuf décorations en ayant rapporté à son commandant… « un pot de crème fraîche. Il avait tellement envie de manger un poulet à la crème ! ». Toujours ce côté décalé, ce deuxième degré que les Américains n’ont probablement pas compris. La première rencontre avec Hitler, le putsch de 1923, la place des élites bavaroises et leurs rapports avec l’armée de von Seeckt, la propagande électorale à la fin des années 1920, et après l’arrivée au pouvoir du NSDAP les actions (et les doutes) des associations d’anciens combattants et de la SA, sont autant de thèmes abordés au fil des pages, toujours en se présentant et en montrant la situation de l’époque avec détachement, presque éloignement, tout en étant semble-t-il hostile sur le fond et désabusé dans la forme. Les propos qu’il tient au sujet de la nuit des longs couteaux sont parfois étonnants, mais finalement « dans ces circonstances, chaque acte est un crime, la seule chose qui nous reste est l’inaction. C’est en tout cas la seule attitude décente ». Ce n’est finalement qu’en 1944 qu’il lui est demandé de prêter serment au Führer dans le cadre de la montée en puissance du Volkssturm, mais « l’homme qui me demandait le serment exigeait de moi que je défende la patrie. Mais je savais que ce même homme jugeait le peuple allemand indigne de survivre à sa défaite ». Conclusion : défendre la patrie « ne pouvait signifier autre chose que de la préserver de la destruction ». Toujours les paradoxes. Dans la dernière partie, le comportement des Américains vainqueurs est souvent présenté de manière négative, évoque les difficultés quotidiennes dans son petit village de haute Bavière : une façon de presque renvoyer dos-à-dos imbécilité nazie et bêtise alliée… et donc de s’exonérer soi-même.

L’architecture générale du livre s’appuie sur les quelques 130 questions auxquelles les Américains demandèrent aux Allemands de répondre en 1945 afin d’organiser la dénazification du pays, mais en les détournant souvent et prenant à de nombreuses reprises le contre-pied des attentes des vainqueurs. A bien des égards, le livre est ainsi non seulement à contre-courant de la doxa habituelle, mais camoufle également bien des aspects d’une réalité que l’Allemagne de la fin des années 1940 refusait de reconnaître : « Ma conscience devenue très sensible me fait craindre de participer à un acte capable, dans ces circonstances incontrôlables, de nuire sur l’ordre de puissances étrangères à un pays et à un peuple dont je suis irrévocablement ». Certaines questions font l’objet de longs développements, mais presque systématiquement un humour grinçant y est présent, comme lorsqu’il s’agit simplement d’indiquer son lieu de naissance : « Je découvre avec étonnement que, grâce à mon lieu de naissance (Kiel), je peux me considérer comme un homme nordique, et l’idée qu’en comparaison avec ma situation les New-Yorkais doivent passer pour des Méridionaux pleins de tempérament m’amuse beaucoup ». Et à la même question, à propos des manifestations des SA dans la ville avant la prise du pouvoir par les nazis : « Certes, la couleur de leurs uniformes était affreuse, mais on ne regarde pas l’habit d’un homme, on regarde son coeur. On ne savait pas au juste ce que ces gens-là voulaient. Du moins semblaient-ils le vouloir avec fermeté … Ils avaient de l’élan, on était bien obligé de le reconnaître, et ils étaient merveilleusement organisés. Voilà ce qu’il nous fallait : élan et organisation ». Au fil des pages, il revient à plusieurs reprises sur son attachement à la Prusse traditionnelle, retrace l’histoire de sa famille, développe ses relations compliquées avec les religions et les Eglises, évoque des liens avec de nombreuses personnes juives (dont sa femme), donne de longues précisions sur ses motivations à l’époque de l’assassinat de Rathenau, sur son procès ultérieur et sur son séjour en prison. Suivant le fil des questions posées, il détaille son éducation, son cursus scolaire, son engagement dans les mouvements subversifs « secrets », retrace ses activités professionnelles successives avec un détachement qui parfois peu surprendre mais correspond à l’humour un peu grinçant qui irrigue le texte, comme lorsqu’il parle de son éditeur et ami Rowohlt. Il revient bien sûr longuement sur les corps francs entre 1919 et 1923, sur l’impossibilité à laquelle il se heurte au début de la Seconde guerre mondiale pour faire accepter son engagement volontaire, tout en racontant qu’il avait obtenu en 1919 la plus haute de ses neuf décorations en ayant rapporté à son commandant… « un pot de crème fraîche. Il avait tellement envie de manger un poulet à la crème ! ». Toujours ce côté décalé, ce deuxième degré que les Américains n’ont probablement pas compris. La première rencontre avec Hitler, le putsch de 1923, la place des élites bavaroises et leurs rapports avec l’armée de von Seeckt, la propagande électorale à la fin des années 1920, et après l’arrivée au pouvoir du NSDAP les actions (et les doutes) des associations d’anciens combattants et de la SA, sont autant de thèmes abordés au fil des pages, toujours en se présentant et en montrant la situation de l’époque avec détachement, presque éloignement, tout en étant semble-t-il hostile sur le fond et désabusé dans la forme. Les propos qu’il tient au sujet de la nuit des longs couteaux sont parfois étonnants, mais finalement « dans ces circonstances, chaque acte est un crime, la seule chose qui nous reste est l’inaction. C’est en tout cas la seule attitude décente ». Ce n’est finalement qu’en 1944 qu’il lui est demandé de prêter serment au Führer dans le cadre de la montée en puissance du Volkssturm, mais « l’homme qui me demandait le serment exigeait de moi que je défende la patrie. Mais je savais que ce même homme jugeait le peuple allemand indigne de survivre à sa défaite ». Conclusion : défendre la patrie « ne pouvait signifier autre chose que de la préserver de la destruction ». Toujours les paradoxes. Dans la dernière partie, le comportement des Américains vainqueurs est souvent présenté de manière négative, évoque les difficultés quotidiennes dans son petit village de haute Bavière : une façon de presque renvoyer dos-à-dos imbécilité nazie et bêtise alliée… et donc de s’exonérer soi-même.

Le choc de la Grande Guerre devait anéantir ses tentatives alternatives, mais d’autres devaient naitre sur les ruines de notre continent. L’expérience révolutionnaire et poétique de Fiume en 1917 sera une autre forme de cette recherche d’une communauté idéale. Mais cela est déjà une autre histoire.

Le choc de la Grande Guerre devait anéantir ses tentatives alternatives, mais d’autres devaient naitre sur les ruines de notre continent. L’expérience révolutionnaire et poétique de Fiume en 1917 sera une autre forme de cette recherche d’une communauté idéale. Mais cela est déjà une autre histoire.

Qui se cache derrière les légendaires Amazones ? Quelles preuves archéologiques avons-nous de l'existence de femmes guerrières chez les anciens nomades de la steppe ? Qui sont leurs héritières ? Pour "Les Hommes aux semelles de vent", l'historien Iaroslav Lebedynsky démêle mythe et réalité.

Qui se cache derrière les légendaires Amazones ? Quelles preuves archéologiques avons-nous de l'existence de femmes guerrières chez les anciens nomades de la steppe ? Qui sont leurs héritières ? Pour "Les Hommes aux semelles de vent", l'historien Iaroslav Lebedynsky démêle mythe et réalité.

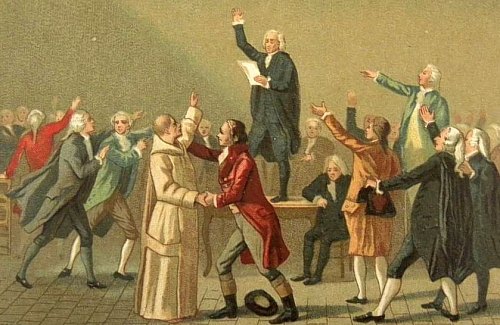

Ceux-ci, dans le sillage de Sieyès, vont très vite s’affirmer « représentants de la nation ». Cela est faux : juridiquement et statutairement ils ne représentent pas la « nation » mais l’Ordre qui les a élus (la Noblesse, le Clergé ou le Tiers Etat). De fait, les trois Ordres délibèrent séparément et chaque député vote au sein de son Ordre. Celui qui représente la nation, qui incarne le Royaume, c’est le Roi (théorie des deux corps : le Royaume est un corps mystique incarné par le corps du Roi). Cependant le 15 juin, passant outre, les députés décident illégalement de la délibération en commun et du vote par tête. Le 17 juin, ils se constituent même, tout aussi illégalement, en « Assemblée nationale ». Leur objectif ? : marquer, au nom du peuple français qu’ils disent représenter, leur prééminence sur le Roi, affirmer que ce n’est plus le monarque qui incarne le Royaume mais la « représentation nationale ». Dès lors, les députés de l’Assemblée captent la légitimité pour légiférer et gouverner en lieu et place du Roi. Il s’agit véritablement d’une prise illégale de pouvoir, le corps de l’Assemblée remplaçant celui du Roi à la tête du Royaume.

Ceux-ci, dans le sillage de Sieyès, vont très vite s’affirmer « représentants de la nation ». Cela est faux : juridiquement et statutairement ils ne représentent pas la « nation » mais l’Ordre qui les a élus (la Noblesse, le Clergé ou le Tiers Etat). De fait, les trois Ordres délibèrent séparément et chaque député vote au sein de son Ordre. Celui qui représente la nation, qui incarne le Royaume, c’est le Roi (théorie des deux corps : le Royaume est un corps mystique incarné par le corps du Roi). Cependant le 15 juin, passant outre, les députés décident illégalement de la délibération en commun et du vote par tête. Le 17 juin, ils se constituent même, tout aussi illégalement, en « Assemblée nationale ». Leur objectif ? : marquer, au nom du peuple français qu’ils disent représenter, leur prééminence sur le Roi, affirmer que ce n’est plus le monarque qui incarne le Royaume mais la « représentation nationale ». Dès lors, les députés de l’Assemblée captent la légitimité pour légiférer et gouverner en lieu et place du Roi. Il s’agit véritablement d’une prise illégale de pouvoir, le corps de l’Assemblée remplaçant celui du Roi à la tête du Royaume.

Les Réprouvés s’ouvre sur une citation de Franz Schauweker : « Dans la vie, le sang et la connaissance doivent coïncider. Alors surgit l’esprit. » Là est toute la leçon de l’œuvre, qui oppose connaissance et expérience et finit par découvrir que ces deux opposés s’attirent inévitablement. Une question se pose alors : faut-il laisser ces deux attractions s’annuler, se percuter, se détruire et avec elles celui qui les éprouve ; ou bien faut-il résoudre la tension dans la création et la réflexion.

Les Réprouvés s’ouvre sur une citation de Franz Schauweker : « Dans la vie, le sang et la connaissance doivent coïncider. Alors surgit l’esprit. » Là est toute la leçon de l’œuvre, qui oppose connaissance et expérience et finit par découvrir que ces deux opposés s’attirent inévitablement. Une question se pose alors : faut-il laisser ces deux attractions s’annuler, se percuter, se détruire et avec elles celui qui les éprouve ; ou bien faut-il résoudre la tension dans la création et la réflexion.

Alors que l’Europe civilisationnelle meurt jour après jour devant nous, sous les coups de boutoir conjugués du modernisme, du mondialisme et du consumérisme, il demeure fondamental de comprendre l’histoire de notre continent, si nous voulons encore croire à un avenir digne de ce nom… À ce titre j’ai récemment découvert, au gré de mes recherches, une petite merveille intellectuelle qui décrypte avec faits, objectifs et arguments circonstanciés, la mort programmée de l’Autriche-Hongrie. Cette dernière reste couramment mais improprement appelée Empire austro-hongrois, alors que son nom exact devrait être Double Monarchie austro-hongroise.

Alors que l’Europe civilisationnelle meurt jour après jour devant nous, sous les coups de boutoir conjugués du modernisme, du mondialisme et du consumérisme, il demeure fondamental de comprendre l’histoire de notre continent, si nous voulons encore croire à un avenir digne de ce nom… À ce titre j’ai récemment découvert, au gré de mes recherches, une petite merveille intellectuelle qui décrypte avec faits, objectifs et arguments circonstanciés, la mort programmée de l’Autriche-Hongrie. Cette dernière reste couramment mais improprement appelée Empire austro-hongrois, alors que son nom exact devrait être Double Monarchie austro-hongroise. Effectivement avant la Grande Guerre, l’Empire jouait un rôle stabilisateur en Europe centrale, comme nous l’avons malheureusement appris à nos dépends depuis son homicide : Deuxième Guerre mondiale, agitations et instabilités politiques chroniques dans cette zone géographique, guerres ethnico-religieuses dans les années 90, etc. Nous citons également le texte introductif de Joseph Roth qui figure dans l’avant-propos, démontrant la cohésion des peuples derrière leur souverain légitime : « Dans cette Europe insensée des États-nations et des nationalismes, les choses les plus naturelles apparaissent comme extravagantes. Par exemple, le fait que des Slovaques, des Polonais et des Ruthènes de Galicie, des juifs encafetanés de Boryslaw, des maquignons de la Bácska, des musulmans de Sarajevo, des vendeurs de marrons grillés de Mostar se mettent à chanter à l’unisson le Gott erhalte (2) le 18 août, jour anniversaire de François-Joseph, à cela, pour nous, il n’y a rien de singulier (3). » Il n’est guère étonnant que les babéliens d’hier et d’aujourd’hui, pourfendeurs des frontières et des identités, ne comprennent pas la nature réelle et profonde de ce cosmopolitisme chrétien et monarchique qui heurte leurs convictions maçonniques…

Effectivement avant la Grande Guerre, l’Empire jouait un rôle stabilisateur en Europe centrale, comme nous l’avons malheureusement appris à nos dépends depuis son homicide : Deuxième Guerre mondiale, agitations et instabilités politiques chroniques dans cette zone géographique, guerres ethnico-religieuses dans les années 90, etc. Nous citons également le texte introductif de Joseph Roth qui figure dans l’avant-propos, démontrant la cohésion des peuples derrière leur souverain légitime : « Dans cette Europe insensée des États-nations et des nationalismes, les choses les plus naturelles apparaissent comme extravagantes. Par exemple, le fait que des Slovaques, des Polonais et des Ruthènes de Galicie, des juifs encafetanés de Boryslaw, des maquignons de la Bácska, des musulmans de Sarajevo, des vendeurs de marrons grillés de Mostar se mettent à chanter à l’unisson le Gott erhalte (2) le 18 août, jour anniversaire de François-Joseph, à cela, pour nous, il n’y a rien de singulier (3). » Il n’est guère étonnant que les babéliens d’hier et d’aujourd’hui, pourfendeurs des frontières et des identités, ne comprennent pas la nature réelle et profonde de ce cosmopolitisme chrétien et monarchique qui heurte leurs convictions maçonniques…

Le général Smedley Butler, auteur du livre "War is a Racket"

Le général Smedley Butler, auteur du livre "War is a Racket"

En France, l’identité politique des historiens de la Révolution est toujours passée au crible et leurs conclusions soupçonnées d’être biaisées par un parti pris idéologique. La polémique récente,

En France, l’identité politique des historiens de la Révolution est toujours passée au crible et leurs conclusions soupçonnées d’être biaisées par un parti pris idéologique. La polémique récente,  Ces idées communes incarnent ce qu’il nomme « la libre pensée ». Cochin dénonce la logique nihiliste de cette esprit né des idéaux philosophiques des Lumières qui tend à déraciner les hommes en les coupant de leurs attaches traditionnelles. Elle s’attaque violemment à l’ordre ancien sans lui proposer d’alternative. Cette philosophie fondée sur un idéal d’égalité entre les individus représente pour lui une abstraction dangereuse. Quand l’ancienne société était organique, composée d’ordres et d’états, la nouvelle société jacobine, dont on voit l’avènement sous la Révolution, est caractérisée par « l’anomie ». Le peuple devient un composé « d’atomes politiques » désorganisé et affaibli. L’historien Gérard Grunberg explique : « Pour Cochin, la Révolution est davantage l’avènement d’un nouveau type de socialisation qu’une bataille sociale ou un transfert de propriété. Elle est discours plus qu’action. » Ce phénomène se concrétise en 1789, mais il est, pour Cochin, l’aboutissement d’un travail de sape amorcé autour des années 1750. « Avant la Terreur sanglante de 93, il y eut, de 1765 à 1780, dans la république des lettres, une terreur sèche, dont l’Encyclopédie fut le comité de salut public, et d’Alembert le Robespierre. » L’enjeu de ses recherches est ainsi de montrer la passerelle entre ce pouvoir intellectuel et le pouvoir politique.

Ces idées communes incarnent ce qu’il nomme « la libre pensée ». Cochin dénonce la logique nihiliste de cette esprit né des idéaux philosophiques des Lumières qui tend à déraciner les hommes en les coupant de leurs attaches traditionnelles. Elle s’attaque violemment à l’ordre ancien sans lui proposer d’alternative. Cette philosophie fondée sur un idéal d’égalité entre les individus représente pour lui une abstraction dangereuse. Quand l’ancienne société était organique, composée d’ordres et d’états, la nouvelle société jacobine, dont on voit l’avènement sous la Révolution, est caractérisée par « l’anomie ». Le peuple devient un composé « d’atomes politiques » désorganisé et affaibli. L’historien Gérard Grunberg explique : « Pour Cochin, la Révolution est davantage l’avènement d’un nouveau type de socialisation qu’une bataille sociale ou un transfert de propriété. Elle est discours plus qu’action. » Ce phénomène se concrétise en 1789, mais il est, pour Cochin, l’aboutissement d’un travail de sape amorcé autour des années 1750. « Avant la Terreur sanglante de 93, il y eut, de 1765 à 1780, dans la république des lettres, une terreur sèche, dont l’Encyclopédie fut le comité de salut public, et d’Alembert le Robespierre. » L’enjeu de ses recherches est ainsi de montrer la passerelle entre ce pouvoir intellectuel et le pouvoir politique.