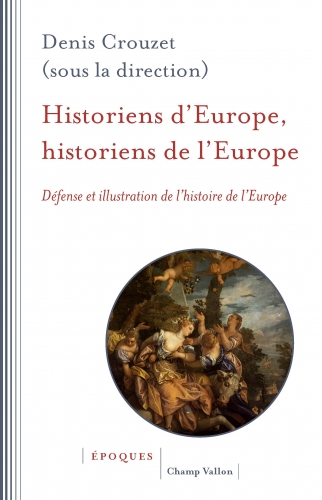

L’historien français Denis Crouzet, spécialiste mondialement reconnu du XVIe siècle français et européen, livre ici en avant-première au Grand Continent l’avant-propos d’Historiens d’Europe, historiens de l’Europe, ouvrage qu’il a dirigé, à paraître le 5 octobre prochain chez Champ Vallon et dédié à la place de l’Europe comme échelle et objet géopolitiques dans la pensée de nombre des plus célèbres historiens européens du XXe siècle.

Cet avant-propos est l’occasion d’une réflexion d’une formidable richesse problématique sur la possibilité d’écrire une nouvelle histoire de l’Europe. Dans la lignée des préoccupations du Grand Continent, entre les apories d’une accumulation d’histoires nationales autosuffisantes et, parfois, les insuffisances théoriques d’une histoire globale automotrice ou réduite à une somme d’histoires parallèles, Denis Crouzet nous invite, fort de quarante années de recherches consacrées notamment à une analyse anthropologique des phénomènes de violence et de pacification en France et en Europe, à considérer les inestimables vertus heuristiques d’une échelle d’analyse intermédiaire européenne dans la compréhension des phénomènes historiques.

Loin de sacrifier aux mythes d’une Europe donnée en propre ou de la lente genèse d’une civilisation partagée, c’est peut-être surtout dans le cadre d’un « jeu d’échelle » que Denis Crouzet envisage l’Europe. Aux prémisses du raisonnement est l’impossibilité de donner sens à des phénomènes historiques sans les inscrire dans un cadre de compréhension qui est avant tout celui de l’Europe davantage peut-être que celui du monde et en tout cas de la nation. C’est parce que l’Europe est par nature une succession de contingences historiques qu’elle est d’ailleurs la métaphore même de l’histoire et mérite donc de sortir de l’impensé et du refoulé. C’est parce qu’à rebours de toute téléologie elle est non hypostase mais hypothèse qu’elle éclaire peut-être si bien le passé. Elle permettrait de réévaluer à la hausse les mérites d’une histoire qui, sans être utilitariste, refuserait en tout cas de définir son objet comme l’impératif catégorique et autosuffisant de la simple connaissance historique et viserait plutôt l’hypothétique, condition d’une pensée libre et vivante intéressée au contemporain et à ses enjeux géopolitiques. Une histoire « thérapie », magister vitæ, serait donc possible en somme, entendu qu’en empruntant ce chemin de sortie de la plus sèche neutralité axiologique positiviste l’on ne débouche pas sur une essentialisation civilisationnelle de l’Europe mais sur une ligne de crête où résonne depuis la vallée de l’histoire l’écho de la quête, depuis le XVIe siècle et l’éclatement de la chrétienté, d’une unité et d’une totalité d’être ; au bout de cette ligne, le sommet de l’universel ? – P.S.

L’intuition qui a donné naissance à la rencontre d’où est issu ce livre est que la crise idéologique subie par l’Europe actuelle relève autant d’un déficit d’historicisation, et donc de nomination, que de la projection de peurs ambiantes ou de fictions négatives issues moins de l’Europe même que d’une fantasmagorie excitatoire liée à l’accélération d’un processus de globalisation. Un processus qui n’est jamais qu’une mise en hypervisibilité, peut-être plus perceptible qu’auparavant, de faits de longue durée que, pourtant, un simplisme démagogique porte à ignorer, à dissimuler, à encore charger de culpabilité. Tout se passe comme si s’était produite la dilatation d’un vide dans la mémoire, un trou noir, une sorte de maladie d’Alzheimer lentement infusée dans les sphères de la pensée commune par des procédures tant conscientes qu’inconscientes, aux ressorts paniques.

Il n’est pas alors étonnant que l’Europe en vienne toujours plus subrepticement à être appréhendée en tant qu’une déraison de l’histoire, le contresens d’une histoire que l’imaginaire ne voudrait voir programmée simultanément, téléologiquement et antinomiquement, qu’en termes de « nation » ou de « patrie », voire plus encore naïvement d’« identité ». C’est-à-dire d’une forme d’atomisation ou d’absolutisation contradictoire du concept de culture démocratique dans laquelle prime l’égalité des individus et qui est conditionnée par, précisément, l’acceptation de la désidentification. L’identité est la relation toujours expansive, sans limite, de la relation à l’autre, et non pas un cercle clos et fini relevant d’un refoulement loin de soi de l’altérité. Elle est par là même mobile et transgressive, moins composite que composée et, pourrait-on dire, de l’ordre de l’irreprésentable, l’indicible tant elle se doit de s’excentrer.

Il ne s’agit pas ici de dire que l’Europe souffre d’un manque d’histoire et que là se trouverait l’explication de la distorsion qui ouvre à tous les possibles négativistes. Là n’est pas le problème, car l’Europe est aussi victime d’un trop d’histoire qui n’est pas, précisément, son histoire, qui l’oblitère plus qu’elle ne l’éclaire. Parce qu’il faut postuler que son histoire ne peut pas s’écrire avec les normes convenues et les outils conventionnels.

Ceci parce que l’histoire n’a pas inventé de manière efficace un discours pouvant « conscientiser » l’Europe autrement que comme une discontinuité d’états, plus ou moins fragiles ou provisoires, de conscience ou de non-conscience de soi. Tout le problème, qui ouvre aux dérives néo-identitaires, relève du langage et de sa dispersion sémiotique. L’Europe est réduite bien souvent à un agrégat d’histoires parallèlement concordantes, quand sa virtualité n’est pas artificieusement rapportée aux concepts problématiques de « civilisation » et de « culture » qui, lentement, au fil des siècles, auraient suivi une progression ascendante conduisant à une situation actuelle voyant le continent osciller entre le méta-national et le global. Plusieurs axes énonciatifs ont été valorisés dans cette double optique.

Une constatation préliminaire intéresse le premier de ces axes. Il n’existe pas d’histoire générale récente de l’Europe en français qui puisse prétendre être à jour des problématiques et des évolutions récentes de la discipline pas plus que présenter un champ interprétatif nouveau adapté aux doutes, aux interrogations du présent. Ainsi le fil directeur apparaît ici être une certaine désidéologisation. Si, peut-être, la conceptualisation « moderniste » d’une histoire de l’Europe peut remonter à François Guizot et à l’Histoire générale de la civilisation en Europe depuis la chute de l’Empire romain jusqu’à la Révolution française (1838), il n’en est pas moins vrai que rien de véritablement ambitieux n’a été écrit depuis la grande tentative du grand historien belge Henri Pirenne et les quatre volumes de l’Histoire de l’Europe – dont le premier volume seul (jusqu’au XVIe siècle) est en réalité de sa plume. Cette histoire est européenne en ce qu’elle appréhende de manière transversale l’ensemble des phénomènes structurant le continent depuis la fin du monde romain, qu’ils soient d’ordre intellectuel ou religieux, socio-économique ou politique. Elle est européenne en ce qu’elle met en rapport ces phénomènes structurants avec l’espace européen dans sa totalité et à travers les configurations successives qu’ils contribuent à déterminer, y compris les divisions qu’ils ont générées.

Cette démarche a servi de modèle à bien des tentatives ultérieures qui n’en ont guère dépassé les fondements ou la méthode. Certes, on peut noter l’existence d’une Histoire générale de l’Europe en trois volumes sous la direction de Georges Livet et Roland Mousnier (Paris, 1980), qui suit une segmentation triséquentielle très classique (« L’Europe des origines au début du XIVe siècle » ; « L’Europe du début du XIVe siècle à la fin du XVIIIe siècle » ; « L’Europe de 1789 à nos jours »). Conçue selon les mêmes normes et entrant dans la sphère des manuels de vulgarisation, on citera l’Histoire de l’Europe donnée par Serge Berstein et Pierre Milza (tome 1 : « L’héritage antique » ; tome 2 : « De l’Empire romain à l’Europe, Ve-XIVe siècle » ; tome 3 : « États et identité européenne, XIVe siècle-1815 » ; tome 4 : « Nationalismes et concerts européens 1815-1919 », etc.). Mais on en demeure à des problématiques périodisées et surtout à des cadres hypothético-déductifs peu renouvelés, quand le créneau chronologique ne se limite pas aux XIXe et XXe siècles – cf. Jean- Michel Gaillard et Antony Rowley, L’Histoire du continent européen (1850-2000) (Paris, 2001). Le principe de base est celui, au sein d’une temporalité qui est présumée posséder une unité d’action, de la succession d’études de cas territoriaux ou étatiques. Dans le même filon d’une temporalité coagulée et coupée en tranches, il est possible d’évoquer un ouvrage synthétique : Histoire de l’Europe de Jean Carpentier et François Lebrun (dir.) (Paris, 1992). Enfin, peut être relevée une tentative d’écriture européenne, qui reste toutefois éclatée en histoires nationales tout en n’échappant pas totalement à une certaine tentation téléologique, l’Histoire de l’Europe par douze historiens européens, sous la direction de Frédéric Delouche (Paris, 1992).

Puis, alors que précisément l’Europe devenait une réalité toujours plus politique, rien ou presque rien, ou des livres qui, sous le couvert d’une globalité européenne, période par période historiographique, sont des successions de monographies « nationales » et débouchent téléologiquement sur la césure d’après une seconde guerre mondiale pensée comme ouvrant sur un moment de sublimation ; ceci, alors que prolifèrent parallèlement les histoires « nationales » retraçant bien souvent, par exemple pour ce qui est de la France, les données présupposées d’une construction logique reposant sur divers enracinements originels et enquêtant, jusqu’à aujourd’hui, sur les conditions ayant présidé à cette logique et sur les permanences ou les ruptures… Sans se poser la question que l’histoire et la logique des continuités ne sont pas synonymes…

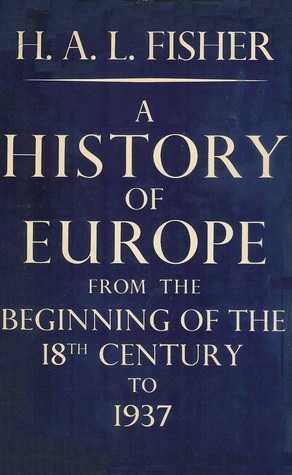

La même constatation d’une situation de relative déshérence historiographique et surtout de la priorité donnée au choix de coupures par périodes (Renaissance, XVIIe siècle) peut être constatée pour ce qui est de la recherche anglo-saxonne, après les deux volumes de l’History of Europe de H. A. L. Fisher (Londres, 1935). Citons l’exemple de la Short Oxford History of Europe qui, si elle est récente, n’en est pas moins très traditionnelle dans sa conception clivant le passé en grandes séquences classiques si ce n’est anachronisantes, à commencer par « Classical Greece » ou « Roman Europe » ; citons aussi, plus originales, les New Approaches to European History de Cambridge Uni- versity Press et les Fontana History of Europe Series qui reposent sur un projet thématico-chronologique. À quoi s’ajoute The Penguin History of Europe, de J. M. Roberts (1996), fort heureusement renouvelée dans les Penguin History of Europe Series grâce aux contributions de grands spécialistes comme Chris Wickham ou Mark Greengrass. Là est le paradoxe, c’est la Grande-Bretagne du Brexit d’aujourd’hui qui a donné récemment les ouvrages scientifiques les plus parachevés sur une Europe désanachronisée et pensée comme une totalité d’histoire ayant fonctionné plus sur des connexions que sur des spécificités ou sur des collections de particularités. Pour aller dans cette direction, l’histoire de l’Europe se trouve travaillée outre-Manche surtout systématiquement sur le plan de l’histoire économique, avec The Cambridge Economic History of Europe et The Fontana Economic History of Europe. Un peu à part, original, et soupçonné aujourd’hui d’européo-centrisme parce que donnant le primat à la question de l’exceptionnalité du continent désormais passé de mode, il y a le livre important d’Eric Jones, The European Miracle (Cambridge, 1981) à l’inverse du plus superficiel Europe. A History, de Norman Davies (Oxford, 1996). Il faudrait signaler encore Eugen Weber et Une histoire de l’Europe, Paris (2 vol., Paris, 1986-1987), qui insiste sur le concept postromantique d’héritage légué au monde mais noie le lecteur sous une avalanche factuelle donnant une certaine invisibilité à l’objet même Europe.

La même constatation d’une situation de relative déshérence historiographique et surtout de la priorité donnée au choix de coupures par périodes (Renaissance, XVIIe siècle) peut être constatée pour ce qui est de la recherche anglo-saxonne, après les deux volumes de l’History of Europe de H. A. L. Fisher (Londres, 1935). Citons l’exemple de la Short Oxford History of Europe qui, si elle est récente, n’en est pas moins très traditionnelle dans sa conception clivant le passé en grandes séquences classiques si ce n’est anachronisantes, à commencer par « Classical Greece » ou « Roman Europe » ; citons aussi, plus originales, les New Approaches to European History de Cambridge Uni- versity Press et les Fontana History of Europe Series qui reposent sur un projet thématico-chronologique. À quoi s’ajoute The Penguin History of Europe, de J. M. Roberts (1996), fort heureusement renouvelée dans les Penguin History of Europe Series grâce aux contributions de grands spécialistes comme Chris Wickham ou Mark Greengrass. Là est le paradoxe, c’est la Grande-Bretagne du Brexit d’aujourd’hui qui a donné récemment les ouvrages scientifiques les plus parachevés sur une Europe désanachronisée et pensée comme une totalité d’histoire ayant fonctionné plus sur des connexions que sur des spécificités ou sur des collections de particularités. Pour aller dans cette direction, l’histoire de l’Europe se trouve travaillée outre-Manche surtout systématiquement sur le plan de l’histoire économique, avec The Cambridge Economic History of Europe et The Fontana Economic History of Europe. Un peu à part, original, et soupçonné aujourd’hui d’européo-centrisme parce que donnant le primat à la question de l’exceptionnalité du continent désormais passé de mode, il y a le livre important d’Eric Jones, The European Miracle (Cambridge, 1981) à l’inverse du plus superficiel Europe. A History, de Norman Davies (Oxford, 1996). Il faudrait signaler encore Eugen Weber et Une histoire de l’Europe, Paris (2 vol., Paris, 1986-1987), qui insiste sur le concept postromantique d’héritage légué au monde mais noie le lecteur sous une avalanche factuelle donnant une certaine invisibilité à l’objet même Europe.

Pour ce qui est de la production allemande, mêmes stratégies d’édition et d’écriture par voie de compartimentages spatio-temporels, avec, par exemple, les sept tomes du Handbuch der europaïschen Geschichte, publié par Theodor Schieder (Stuttgart, 1968-1991) ou les dix volumes du Handbuch der Geschichte Europas, dirigé par Peter Bickle (Stuttgart, 2000). L’histoire en tranches face à laquelle s’est dressé Wolfgang Schmale, dans sa Geschichte Europas (Stuttgart, 2000), qui est peut-être le seul pari vraiment « européiste » mais ayant privilégié l’angle culturel pour le moins réductionniste. Pour l’Italie, il faudrait citer bien sûr ensuite la récente Storia d’Europa de Giuseppe Galasso (Bari, 2001) qui envisage l’Europe comme sous l’angle de « contrasioni e di espansioni di un grande spazio di civiltà ». Le thème problématique d’un espace de convergence postulée entre une identité géographique et une identité qui serait « psychoculturelle ». Le mythe de la civilisation partagée… Un autre danger…

Second axe : arrêtons-nous sur la tradition de l’essai centré sur l’histoire d’une conscience ou d’une préconscience européenne. Y appartiennent des livres importants, au premier rang desquels figure l’ouvrage de Lucien Febvre, L’Europe, genèse d’une civilisation. Ce cours, professé au Collège de France en 1944-1945, pose l’Europe non comme un déterminisme, géographique, naturel voire biologique, mais comme un fait historique qui doit être analysé en termes de culture, de civilisation, et au final, de manière implicite, de projet politique relevant d’une série de dynamiques. Doit être encore citée de manière privilégiée la Storia dell’idea d’Europa de Federico Chabod (1961), qui a une tonalité particulière dans la mesure où l’important de la démonstration tient dans la succession et la réaccommodation de valeurs morales et spirituelles d’identification collective depuis le temps des Grecs jusqu’au XVIIIe siècle. Jean-Baptiste Duroselle a fait figure de pionnier tant en 1965 dans son Idée d’Europe dans l’Histoire, mettant en relief une conscience commune, que dans L’Europe, histoire de ses peuples (Paris, 1990), qui se situe dans la perspective de Pirenne et de Febvre ; y est dégagée une succession de scansions, depuis les mégalithes ou l’expansion celte jusqu’à la démocratisation des nations de l’Est, qui ont fini par déterminer un mouvement de dépassement des langues, des cultures, des conflits politiques ou économiques. Et là encore, on retrouve le mythe de la civilisation partagée…

On peut, entre autres travaux individuels ou collectifs, ajouter à cette sphère d’écriture Krzysztof Pomian, L’Europe et ses nations (Paris, 1990), puis Jacques Le Goff, La Vieille Europe et la nôtre (Paris, 1994) ou L’Europe est-elle née au Moyen Âge ? (Paris, Seuil, 2003). L’ouvrage de Denis de Rougemont, Vingt-huit siècles de l’Europe, la conscience européenne à travers les textes d’Hésiode à nos jours (Paris, 1961), est un produit militant issu de la réflexion de l’un des fondateurs du projet européen de l’après-1945. Notons encore Identités nationales et conscience européenne, sous la direction de Joseph Rovan et Gilbert Krebs (Paris, 1992). Et encore, L’Europe dans son histoire. La vision d’Alphonse Dupront, publié par François Crouzet et François Furet (Paris, 1998). Ou Penser l’Europe, d’Edgar Morin (Paris, 1987), qui met l’accent sur la complexité européenne, et sur le dialogue des pluralités ou l’interculturalité étant le moteur interne de l’histoire de l’Europe, « unitas multiplex ».

On peut, entre autres travaux individuels ou collectifs, ajouter à cette sphère d’écriture Krzysztof Pomian, L’Europe et ses nations (Paris, 1990), puis Jacques Le Goff, La Vieille Europe et la nôtre (Paris, 1994) ou L’Europe est-elle née au Moyen Âge ? (Paris, Seuil, 2003). L’ouvrage de Denis de Rougemont, Vingt-huit siècles de l’Europe, la conscience européenne à travers les textes d’Hésiode à nos jours (Paris, 1961), est un produit militant issu de la réflexion de l’un des fondateurs du projet européen de l’après-1945. Notons encore Identités nationales et conscience européenne, sous la direction de Joseph Rovan et Gilbert Krebs (Paris, 1992). Et encore, L’Europe dans son histoire. La vision d’Alphonse Dupront, publié par François Crouzet et François Furet (Paris, 1998). Ou Penser l’Europe, d’Edgar Morin (Paris, 1987), qui met l’accent sur la complexité européenne, et sur le dialogue des pluralités ou l’interculturalité étant le moteur interne de l’histoire de l’Europe, « unitas multiplex ».

En troisième lieu, il faut relever l’axe très actif de l’histoire de la construction européenne, donc une histoire du terminus ad quem à épistémologie courte. Une étonnante prolifération d’ouvrages oscillant entre manuels et études d’intérêt général. Citons entre autres, et au milieu d’un océan textuel, Pierre Gerbet, La Construction de l’Europe (Paris, 1996), Serge Bernstein et Pierre Milza, Histoire de l’Europe contemporaine (2 t., Paris, 1992), Marie-Thérèse Bitsch, Histoire de la construction européenne, Paris, 1996, Gérard Bossuat, Les Fondateurs de l’Europe (Paris, 1994), P. Fabre, Histoire de l’Europe au XXe siècle, 1945-1974 (2 vol., Paris, 1995), Michel Foucher, Fragments d’Europe (Paris, 1993), etc. Une prolifération d’ouvrages érudits dont le propre est de gommer ou estomper, au profit d’analyses détaillées des mécanismes du processus de la construction européenne, la durée longue et en conséquence le questionnaire de la dialectique des possibles en amont de l’immédiate contemporanéité. Tout se passe comme si l’histoire de l’Europe devait être écrite et sur-écrite de manière nécessairement positiviste, sans qu’il soit tenu compte de la réflexion de Mark Mazower, pour qui la question est de savoir si « l’Europe a une histoire au sens habituel du mot ».

Le danger serait de partir à la recherche d’un invariant identifié, qui serait appelé Europe, qui aurait une histoire plus ou moins sinusoïdale, mais qui aurait « une histoire » en développement fait d’avancées et retraites, d’émergences et d’occultations, donc de significations et de désignifications se neutralisant dans une logique de l’incertitude ; alors qu’il faudrait articuler précisément « histoire » à ce qui serait sa négation même, une aporie autogénérée d’une pluralité de contingences négatives ou positives. Aporie au sens donné par Diodore Kronos dans l’analyse de Jules Vuillemin : « Est contingent ce qui est possible et ce qui est non nécessaire, c’est-à-dire la conjonction logique de ce qui est ou sera et de ce qui n’est pas ou ne sera pas. Cette définition a pour effet qu’est contingent ce qui n’est pas et sera ou ce qui est et ne sera pas ou ce qui sera et ne sera pas. »

En quatrième lieu, un autre axe a pris forme autour d’histoires de l’Europe œuvrant sur la longue durée mais en se fixant sur une chronologie particularisée pour les uns, autour d’une approche thématique pour d’autres. Citons, à titre d’exemples, les ouvrages qui ont fait le choix, sur une période distincte, d’analyser, dans les années 1960-1970, l’Europe par le biais de la problématique de la « civilisation » : La Civilisation de l’Occident médiéval (Jacques Le Goff), La Civilisation de la Renaissance (Jean Delumeau), La Civilisation de l’Europe classique (Pierre Chaunu), La Civilisation de l’Europe des Lumières (Pierre Chaunu), L’Europe des Lumières (Jean Meyer, 1989), Napoléon et l’Europe. Regards d’historiens (Thierry Lentz dir., Paris, 2004), etc. D’autres ont pris le parti d’analyser l’histoire européenne sous l’angle des villes, avec l’Histoire de l’Europe urbaine, sous la direction de Jean-Luc Pinol, Paris 2003 (t. I, « De l’antiquité au XVIIIe siècle, genèse des villes européennes » ; t. II, « De l’Ancien Régime à nos jours. Expansion et limites d’un modèle »)…

On pourrait encore évoquer le centrage sur la démographie, avec l’Histoire des populations de l’Europe éditée par Jean-Pierre Bardet et Jacques Dupaquier (3 vol., Paris, 1997), sur l’histoire de l’écosystème, avec l’Histoire de l’environnement européen de Robert Delort (préface de Jacques Le Goff, Paris, 2001). L’Europe peut encore s’écrire dans la longue durée de son histoire économique tendant vers une « unité organique » malgré ses « diversités », avec L’Histoire de l’économie européenne 1000-2000 de François Crouzet (Paris, 2000) : « On essaiera constamment de considérer l’Europe comme un ensemble, et de prêter attention aux relations entre ses diverses parties : au commerce intra-européen, qui s’est développé de bonne heure, notamment sur la base des dotations différentes en ressources de l’Europe du Nord et de celle du Sud ; à la diffusion des institutions, des organisations et des technologies, aux migrations de main-d’œuvre et de capitaux. On recherchera les forces qui ont rapproché les régions européennes et contribué à créer une économie européenne intégrée – même si ce ne fut que de façon lâche. Cependant, ni les forces centrifuges, ni les rapports avec le monde extérieur ne seront négligés… ». D’autres enquêtes se sont fixées dans la problématique de Les Racines de l’identité européenne, de Francis Dumont (Paris, 1999) ou de La Conscience européenne au XVIe siècle de Françoise Autrand et Nicole Cazauran (éd.) (Paris, 1983) ; ou dans le champ de l’histoire des relations internationales avec L’Ordre européen du XVIe au XXe siècle, dirigé par Georges-Henri Soutou (Paris, 1998) ou La Société des princes (Paris, 1999), de Lucien Bély.

On pourrait encore évoquer le centrage sur la démographie, avec l’Histoire des populations de l’Europe éditée par Jean-Pierre Bardet et Jacques Dupaquier (3 vol., Paris, 1997), sur l’histoire de l’écosystème, avec l’Histoire de l’environnement européen de Robert Delort (préface de Jacques Le Goff, Paris, 2001). L’Europe peut encore s’écrire dans la longue durée de son histoire économique tendant vers une « unité organique » malgré ses « diversités », avec L’Histoire de l’économie européenne 1000-2000 de François Crouzet (Paris, 2000) : « On essaiera constamment de considérer l’Europe comme un ensemble, et de prêter attention aux relations entre ses diverses parties : au commerce intra-européen, qui s’est développé de bonne heure, notamment sur la base des dotations différentes en ressources de l’Europe du Nord et de celle du Sud ; à la diffusion des institutions, des organisations et des technologies, aux migrations de main-d’œuvre et de capitaux. On recherchera les forces qui ont rapproché les régions européennes et contribué à créer une économie européenne intégrée – même si ce ne fut que de façon lâche. Cependant, ni les forces centrifuges, ni les rapports avec le monde extérieur ne seront négligés… ». D’autres enquêtes se sont fixées dans la problématique de Les Racines de l’identité européenne, de Francis Dumont (Paris, 1999) ou de La Conscience européenne au XVIe siècle de Françoise Autrand et Nicole Cazauran (éd.) (Paris, 1983) ; ou dans le champ de l’histoire des relations internationales avec L’Ordre européen du XVIe au XXe siècle, dirigé par Georges-Henri Soutou (Paris, 1998) ou La Société des princes (Paris, 1999), de Lucien Bély.

L’Europe, malgré toutes ces tentatives, pâtit donc de la dispersion ou de la division de son histoire, d’une dramatique occultation de sens tenant en grande partie à ce que cette histoire est le contraire de ce qu’elle devrait chercher à être. Elle pâtit de ce que son histoire est écrite comme si elle était n’importe quelle histoire. Alors qu’elle doit s’analyser différenciellement. Écrire l’histoire revient à produire un système de contingences et intermittences multiples et pas seulement à fabriquer un discours cumulatif de données inspirant des parallélismes ou des convergences. Et c’est ce « faire comprendre » qui a manqué et qui toujours manque aujourd’hui. Le projet de ceux qui ont pris part à la confection de cet ouvrage est de prendre part à une autre écriture de l’histoire de l’Europe, qui serait « nouvelle » parce qu’elle serait moins facticiste ou téléologique que dialectique.

Le but est de fournir au lectorat universitaire comme non universitaire les lignes de forces d’une anthropologie historique des possibles, qui ne doit pas être subvertie par les forces démagogiques qui instrumentent les incertitudes, les angoisses, les fixations collectives. L’Europe ne serait pas alors à évaluer sous l’angle d’une quête de ses origines, de sa lente maturation, de ses échecs, de ses antagonismes internes, de ses expériences plus ou moins brèves et marquantes. L’Europe historique a en effet un trait comme structurel : elle est contingence et par là même elle se révèle en tant qu’herméneutique. Il y eut une Europe des humanistes, une Europe de la république des Lettres, une Europe des idéaux de 1789…, comme il y a eu à partir de 1951 et de la CECA le déclenchement de la mise en œuvre d’une Europe économique. Comme il y a eu une Europe des clivages de religion, des nations et nationalismes, des haines et des atrocités… L’Europe existe aussi, c’est ce que l’on tend à ignorer ou euphémiser, dans le sang et la violence.

C’est cette discontinuité dans l’ambivalence, qui est bien souvent gommée au profit d’une téléologie simpliste. D’où l’hypothèse que pour trouver un point d’origine à une réflexion qui se prévaut d’une histoire « magister vitæ », il faut aller vers les grands historiens qui ont tous croisé durant le XXe siècle, avec une intensité variable et des modes de polarisation différents, la nécessité herméneutique des possibles contingents de l’Europe ; qui ont pensé par l’Europe et pour certains pour l’Europe, parce que l’Europe donnait sens à l’histoire qu’ils entendaient réécrire ou reconstruire, donnait sens tout simplement. L’histoire est une succession de possibles plus ou moins réalisés et donc plus ou moins perdus, et l’Europe est alors la métaphore de l’histoire. Elle existe parce qu’elle se confond avec l’histoire.

C’est dans cette perspective qu’ont été ainsi distinguées dix-neuf grandes figures britanniques, allemandes, hollandaises, belges, italiennes, russes et bien sûr françaises qui, selon des stratégies différenciées, ont été conduites de manière plus ou moins parachevée et englobante à observer ou constater que l’Europe pouvait ou pourrait avoir eu sur le long comme les moyen et court termes une histoire conjointe transcendant les frontières établies et surtout les cadres analytiques présumés. Une histoire collective permettant autant de regarder vers un avenir dédramatisé que de déphaser dialectiquement l’étude de chaque construction géopolitique du passé vers la structure métasignifiante qu’est ou a été le cadre européen. Si l’on y réfléchit, tous ces grands historiens ont participé au grand changement de l’épistémologie historique parce que l’Europe, avec plus ou moins de centralité ou d’intensité, s’est glissée entre eux et leurs objets de recherche, qu’elle les a guidés dans leurs analyses de manière directe ou indirecte. Il ne s’est pas agi de faire l’inventaire de « tous » les historiens ayant intégré l’Europe dans leur épistémologie, mais de travailler sur les caractérisations et les déterminations d’approches tentant de produire l’Europe comme relevant autant de la distinction d’un référent commun que de mises en problèmes ouvrant au dépassement des habitus historiographiques et opérant sur les plans soit autonomes soit solidaires de l’histoire économique, sociale, culturelle, politique… De la nécessité donc de l’Europe dans la conscience des Européens parce que leur histoire, à tous ses niveaux travaillée et expertisée scientifiquement par les plus grands historiens, se pense par l’Europe, qu’ils ont été et sont historiquement des Européens de la dialectique des possibles et des impossibles de l’Europe, dans les temps de paix comme de guerre, malgré eux bien souvent…

Répétons-le, il ne s’est agi ici que de procéder par une sorte de carottage dans les profondeurs du discours historique, car l’objectif n’a pas été de dresser un inventaire de tous les grands historiens ayant pensé par ou pour l’Europe. L’exhaustivité aurait entraîné trop loin, jusqu’à une remontée vers la seconde moitié du XVIe siècle ; alors les inventeurs de l’histoire parfaite tentaient en effet de tirer les leçons de la fin de l’unité chrétienne et des atroces déchirements qui étaient vécus dans le présent en opérant un dépassement géopolitique, comme Lancelot Voisin de La Popelinière avec L’histoire de France enrichie des plus notables occurrances survenues ez provinces de l’Europe & pays voisins, soit en paix soit en guerre : tant pour le fait séculier qu’eclésiastic. Quand les rêves les plus destructeurs et barbares s’emparaient des imaginaires dans le royaume de France du temps des guerres de Religion, l’Europe autorisait la prise de conscience d’une unité qui était douloureuse certes, mais aidait ceux qui étaient persécutés et qui étaient troublés au point de voir l’avenir fermé, à conserver l’espérance. Il aurait donc été possible de s’engager dans cette veine herméneutique sur la longue durée et de composer un ouvrage sur la distanciation positive que l’Europe a pu générer par rapport à l’immédiateté de son histoire. Une Europe qui était une thérapie.

Mais il a été préféré de mettre en action une dynamique de focalisation sur certains des historiens ayant participé du grand renouvellement historiographique du XXe siècle. Des historiens ayant mis en œuvre des procédures décentrant leur écriture de l’histoire « nationale » ou campaniliste ou de l’histoire globale (histoire des civilisations, World History, Connected History…) ; ceci soit en expérimentant que c’est par le détour obligé vers l’Europe que peuvent se construire les processus de compréhension de l’histoire dans tous ses points d’imputation, soit en usant d’une optique européenne leur permettant de penser ou de repenser un passé qui serait matriciel dans le présent de l’Europe en fonction de la détection de possibles contingents, et donc un futur en rupture avec les drames et conflits que cette dernière a connus. L’Europe donc pour penser l’histoire, ou l’histoire pour penser l’Europe. L’Europe pour ne pas rester enfermé en soi, mais pour se situer dans toutes les virtualités de ce « soi ».

Il a fallu procéder à des choix. Georges Duby, pour ne citer que lui, est un des grands absents du livre, tout comme Benedetto Croce, ou Alphonse Dupront qui n’a pas été retenu puisque ayant donné occasion à une publication axée précisément sur son « européité » – L’Europe dans son histoire. La vision d’Alphonse Dupront (Paris, PUF, 1998). Quant à un autre grand absent du livre, Marc Bloch, c’est une absence subie qui doit être cette fois déplorée puisque l’auteur de la communication, pourtant spécialiste incontesté et donc incontournable, n’a pas daigné rendre son texte.

Le principe a été empiriquement d’isoler quelques parcours intellectuels qui ont lié la quête d’une alternative aux déchirements guerriers et nationalistes ayant affecté historiquement le continent au XXe siècle, et une écriture s’étant donné pour objectif le discernement, par voie comparatiste ou structuraliste et hors de toute téléologie, de ce que l’on peut appeler un « sens » transcendant les spécificités et les différences. L’Europe comme « matrice d’unité » s’imposant à l’écriture même à la fois de son histoire et de l’histoire, et dont l’évocation des jeux possibles et impossibles est aujourd’hui nécessaire en un temps peut-être périlleux de fragilisation. Comme quoi la nécessité exige bien, comme cela a été entrevu, une herméneutique de la contingence.

L’Europe n’a pas été alors pour nombre d’historiens l’objet d’une déclaration de foi les portant à chercher dans l’histoire un sens leur permettant de poser les cadres d’un dépassement heuristique. Elle a bien souvent été moins une finalité qu’un instrument cognitif fournissant un support ou une impulsion à leur réflexion, selon des objectifs et des procédures très variables, voire multiples. Une « matrice nourricière » selon l’expression d’Alphonse Dupront.

Elle peut se dissimuler, d’après Jean-Pierre Poussou, dans l’arrière-fond du travail du grand historien Trevelyan et ce à travers une fascination pour une Italie qui serait portée à « importer le modèle anglais sur le continent » et, de la sorte, à initier une autre histoire européenne, le paradigme libéral d’une supériorité de la civilisation anglaise s’enracinant dans les autres paradigmes de la république romaine et des républiques de la Renaissance signifiant l’avenir de l’histoire. Paradoxalement ou du moins en apparence, l’affirmation d’une supériorité britannique s’accompagne d’un regard sur l’Europe.

Pour le Russe Aaron Gourevitch, décrypté par son ancien secrétaire Pavel Ouvarov, ce furent sans doute ses propres études sur l’Angleterre du haut Moyen Âge puis sur la Scandinavie qui l’entraînèrent dans une mutation heuristique capitale remettant en cause les postulats marxistes obligés et façonnant une image de l’Europe médiévale concordant avec celle que présentait synchroniquement Jacques Le Goff. L’Europe, parce qu’elle avait un rôle historique particularisé dont l’anthropologie permettait de dessiner les contours et parce qu’elle nécessitait de penser autrement, fut ainsi l’agent d’une grande remise en cause idéologique anticipatrice puis accompagnatrice de l’effondrement de l’URSS. Un effondrement qui rendit à l’Europe une partie d’elle-même.

Quant à John Bossy, on peut deviner qu’il polarisa ses enquêtes sur l’Europe moderne parce que l’Angleterre, son premier champ d’études, le conduisit à faire le tableau d’un catholicisme résiduel, fonctionnant en parallèle des sectes protestantes, et que cette situation de marge sollicitait à ses yeux la remontée dans un espace-temps européen antérieur aux ruptures du XVIe siècle ; d’où la nécessité d’analyser, dans leurs impacts civilisationnels, les mécanismes des changements religieux conditionnant le phénomène de grand basculement d’un temps vers un autre. Seule l’Europe semble permettre de penser et de comprendre, et pour l’historien, de compenser, selon Joseph Bergin, la sensation de « vide » que pouvait éprouver un catholique dans un univers majoritairement protestant. Elle renvoie en tant qu’objet analytique à des expériences personnelles diverses et divergentes mais surtout à la prise de conscience de la nécessité de comprendre celles-ci à partir du principe d’un dépassement géopolitique qui fait donc dialoguer le passé avec le présent et le présent avec le passé.

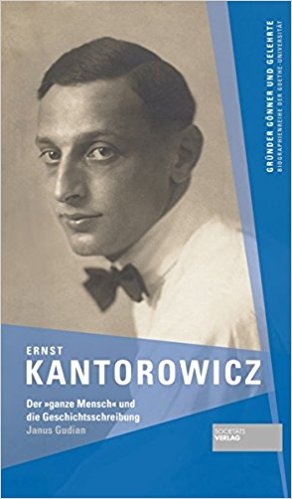

On peut poursuivre avec Ernst Kantorowicz et son parcours qui le mène tout d’abord de Frédéric II, empereur-sauveur, et d’un attachement à un Reich imaginé régénérateur, de la foi dans le génie de la nation allemande, au boycott de ses cours par les étudiants nazis, puis à son exfiltration d’Allemagne. Parvenu aux USA et nommé à Berkeley, il doit affronter le maccarthysme en se faisant le défenseur d’une conception européenne de l’université à laquelle il reste attaché. Et son œuvre, qui est alimentée de multiples sources puisées dans des espaces et des temps différents, Gérald Chaix l’écrit, dépasse les évidences dans un paradoxe apparent : parce que sa « perspective est d’emblée européenne, même si, dans sa lecture impériale, il attribue à une Allemagne imprégnée de romanité un destin privilégié. Elle le demeure lorsque les circonstances, mais aussi ses propres choix, l’en éloignent. Elle se précise lorsque étudiant la conception anglaise des deux corps du roi, il situe explicitement celle-ci dans la construction chronologique et géographique d’une histoire européenne nullement close sur elle-même. » Kantorowicz pense par l’Europe. L’Europe conditionne sa pensée et son inventivité d’historien.

On peut poursuivre avec Ernst Kantorowicz et son parcours qui le mène tout d’abord de Frédéric II, empereur-sauveur, et d’un attachement à un Reich imaginé régénérateur, de la foi dans le génie de la nation allemande, au boycott de ses cours par les étudiants nazis, puis à son exfiltration d’Allemagne. Parvenu aux USA et nommé à Berkeley, il doit affronter le maccarthysme en se faisant le défenseur d’une conception européenne de l’université à laquelle il reste attaché. Et son œuvre, qui est alimentée de multiples sources puisées dans des espaces et des temps différents, Gérald Chaix l’écrit, dépasse les évidences dans un paradoxe apparent : parce que sa « perspective est d’emblée européenne, même si, dans sa lecture impériale, il attribue à une Allemagne imprégnée de romanité un destin privilégié. Elle le demeure lorsque les circonstances, mais aussi ses propres choix, l’en éloignent. Elle se précise lorsque étudiant la conception anglaise des deux corps du roi, il situe explicitement celle-ci dans la construction chronologique et géographique d’une histoire européenne nullement close sur elle-même. » Kantorowicz pense par l’Europe. L’Europe conditionne sa pensée et son inventivité d’historien.

C’est paradoxalement encore que Reinhardt Koselleck a posé les fondements, ambigus sans aucun doute parce que déterminés au sein d’une dialectique plus ou moins consciente de la culpabilité/déculpabilisation, si l’on suit l’étude de Thomas Maissen, d’une construction conceptuelle certifiant que c’est par l’Europe que s’expliquerait l’aventure nazie inscrite dans un phénomène de « guerre civile » européenne ayant désormais réalisé sa migration dans une guerre civile mondiale, mais enracinée dans le champ conceptuel de Lumières du XVIIIe siècle qui ont été européennes. Ici l’Europe fixe l’écriture parce qu’elle sert à déspécifier une histoire, à la désintégrer en la sortant en quelque sorte d’elle-même, de ses jeux particularisés.

À l’inverse, peut-on souligner à travers l’analyse de Jean-François Dunyach, le travail de Hugh Trevor-Roper sur la crise générale du XVIIe siècle, s’il permet de définir une Europe frappée par un continuum de crise, de scansions ayant des origines et des conséquences identifiables selon les différents pays, n’en ouvre pas moins à la valorisation d’« une communauté, unique, de destins au pluriel » et donc à la restitution d’une histoire dialectique qui fait travailler ensemble l’unité et la multiplicité.

Et avec Robert Lopez, Jean-Claude Marie Vigueur démontre que l’Europe médiévale est un moyen de penser l’histoire à l’échelle du monde puisqu’elle permet de partir à la recherche de ce qui a fait sa spécificité, l’essor de l’individualisme et donc ce que l’on pourrait appeler un état d’esprit. L’Europe autorise la désignation de ce qu’il faudrait nommer « une révolution mentale » articulée à la révolution commerciale, il faut aussi voir que le processus de changement doit être mis en rapport avec les grandes catastrophes qui ont marqué le reste du monde et dont l’Europe n’a pas connu l’intensité destructrice. Finalement l’histoire de l’Europe aide à saisir le pourquoi de l’agencement du mouvement en histoire et donc de la dynamique dialectique des contingences. Elle veut moins assurer d’une identité que produire une théorie expérimentale de l’histoire mettant en avant la part de l’individualisme.

La réflexion de Fernand Braudel, originellement méfiant quant à déterminer ce que peut être l’Europe face à l’unité qu’il détecte dans la Méditerranée, est aussi une réflexion sur le « mouvement », le changement qui donne « un destin » à l’Europe. Sans l’Europe rien ne peut se comprendre car l’Europe est investiguée comme devenant la « plus vaste Europe » qui tend à se confondre avec le monde ; elle ne se caractérise plus par sa géographie continentale car elle est un cheminement vers la totalité, vers le sens de l’histoire. Elle fait glisser l’historien vers une forme de philosophie de l’histoire, de la nécessité de l’histoire telle qu’elle s’est à l’échelle du monde inventée. Ainsi pour Braudel, la grammaire de l’Europe serait devenue la grammaire du monde, et le monde serait devenu l’Europe dans une sorte d’englobement rétroactive d’une totalité par une autre. Où l’on retrouve toujours et encore, d’une autre façon proposée, l’idée que l’Europe, pour les historiens, a été le moyen pour penser l’histoire, parvenir à la conceptualiser dans une dialectique mettant en action le particulier et le général, l’un et le tout. À la faire basculer dans une « nouvelle histoire ».

Penser par l’Europe, mais aussi penser pour l’Europe. La seconde partie du livre s’attache à une autre modalité de mise en problème historique de l’Europe. Avec en ouverture bien sûr, Johan Huizinga qui traduit une volonté d’écrire une histoire de l’Europe dans la perspective d’une fin de durée, un « automne » du Moyen Âge d’abord franco-bourguignon caractérisé par une exacerbation d’affects contradictoires, l’exubérance d’une vie contrastée mais commune. Et ensuite, après les idéaux chevaleresques, il y eut les idéaux renaissants qui transcendèrent la diversité des hommes et des nations. Et Jean-Baptiste Delzant d’insister sur un point : l’Europe de Huizinga est d’abord un « esprit » transhistorique qui en appelle à un « besoin d’unité civilisatrice » et donc à une exigence morale partagée et conceptualisée, entre autres, par Érasme. L’histoire apparaît tel un bouclier, une mise en défense contre les idéologies négatives ultranationalistes, contre les ruines qui en adviennent et en sont advenues au cours du XXe siècle, et pour Huyzinga, de ce fait, elle a un avenir et un présent : « donner corps à une unité désirée… ».

Penser par l’Europe, mais aussi penser pour l’Europe. La seconde partie du livre s’attache à une autre modalité de mise en problème historique de l’Europe. Avec en ouverture bien sûr, Johan Huizinga qui traduit une volonté d’écrire une histoire de l’Europe dans la perspective d’une fin de durée, un « automne » du Moyen Âge d’abord franco-bourguignon caractérisé par une exacerbation d’affects contradictoires, l’exubérance d’une vie contrastée mais commune. Et ensuite, après les idéaux chevaleresques, il y eut les idéaux renaissants qui transcendèrent la diversité des hommes et des nations. Et Jean-Baptiste Delzant d’insister sur un point : l’Europe de Huizinga est d’abord un « esprit » transhistorique qui en appelle à un « besoin d’unité civilisatrice » et donc à une exigence morale partagée et conceptualisée, entre autres, par Érasme. L’histoire apparaît tel un bouclier, une mise en défense contre les idéologies négatives ultranationalistes, contre les ruines qui en adviennent et en sont advenues au cours du XXe siècle, et pour Huyzinga, de ce fait, elle a un avenir et un présent : « donner corps à une unité désirée… ».

Henri Pirenne et son Histoire de l’Europe peuvent alors intervenir. Marc Boone et Sarah Keymeulen, d’emblée, insistent sur l’aspect thérapeutique de l’écriture, qui fait penser l’Europe comme « une communauté dynamique » se renouvelant après des séquences de dépressivité dont l’une, celle d’après 1918 et plus encore des années trente, contraint l’historien belge de la Belgique, avec d’autres, à repenser son métier dans le sens d’une dénonciation des divagations racisto-nationalistes des nazis. Mais cette prise de position résolument « internationaliste », humaniste, libérale et pacifiste se combine avec une affirmation de la Belgique comme môle symbolique : « l’idée d’une certaine Europe ne servait pas uniquement à démontrer l’existence d’une identité belge […], mais également à souligner la mission diplomatique du pays pour promouvoir en Europe la coopération, la paix et le progrès ». L’historien est le révélateur d’un fonctionnement du particulier au général et du général au particulier…

Il n’est peut-être pas absurde alors de faire un parallèle avec Norbert Elias, parvenant à une histoire européenne par les biais de la sociologie, de la psychologie, des émotions, mais aussi guidé, selon Francisco Bethencourt, sans aucun doute dans la mise en exergue de la formation d’une civilisation des mœurs courant en Europe depuis Érasme par le désir d’identification historique d’un contre-monde qu’il subissait et qui l’avait chassé de son Allemagne natale. Ou plutôt d’une contre-impulsion replaçant la violence au cœur de la vie des hommes. Car la civilisation des mœurs sur laquelle Elias se met au travail, et qu’il scrute attentivement, associe une pacification des relations sociales à une régulation passant par l’autocontrainte des individus. L’histoire à nouveau comme une thérapie qui ne se dit pas, mais qui cherche à analyser la disciplination sociale jadis structurée autour des pouvoirs étatiques au moment même où elle se défait en une sauvagerie encadrée, légitimée par des idéologues animés par une pensée mortifère et criminelle. Ou plutôt en une décivilisation des mœurs.

Si l’histoire s’écrit comme une défense face à l’angoisse de voir un monde se défaire, à la peur, elle peut aussi être édictée par un désir militant d’action et donc de paix. Et alors il est difficile de savoir ce qui guide la pensée de Henri Hauser, ce qui façonne son engagement d’historien, du passé et de ses conflits, de ses développements économiques ou de ses modes de domination, ou du présent. Comme l’écrit Claire Dolan, « L’histoire devient alors le témoin des idées qu’il défend », mais ses idées, par exemple celles qui touchent à l’application du droit et qui lui font mettre en avant le principe de compromis, lui viennent aussi de son expérience de l’analyse historique. « Par l’histoire, Hauser place donc la France au cœur d’un ensemble beaucoup plus vaste dont il faudra gérer les relations entre les éléments. L’apport français est intellectuel, il fournit les arguments pour penser l’Europe, mais laisse aux diplomates le soin d’en imaginer l’organisation concrète. »

Federico Chabod

En Italie, il y a eu Federico Chabod qui s’attacha à construire le lien opératoire du Risorgimento et du Rinascimento, en passant par les Lumières et la Révolution française. Donc une autre voie analytique intégrant cependant un cadre dialectique puisque sans l’Italie, rien n’aurait pu être possible mais puisque aussi sans l’Europe il n’y aurait eu, en Italie et ailleurs, que de la non-conscience de soi. Le Prince de Machiavel, si l’on suit Guido Castelnuovo, joue alors comme paradigme donné par l’Italie à l’Europe puisque posant les fondations d’un mode de pensée et d’action défini, au-delà de la morale, par « la liberté et la grandeur de l’action politique, la force et l’autorité du pouvoir central ». L’histoire est, pour Chabod, l’histoire de l’idée d’Europe, de ses « traditions morales et culturelles, nous oserions dire plus que son présent, son passé… », mais dans une nécessité de s’interroger sur ce qu’a pu être la trame inventive d’une conscience de l’Europe et sur ce que cette conscience peut dicter au présent comme sens… Un Chabod proche d’Alphonse Dupront dans son épistémologie mettant en valeur le concept de « matrice ».

Avec Lucien Febvre, l’historien « pour l’Europe » acquiert une grande densité, même si le livre qui aurait pu être écrit n’a jamais vu le jour. L’Europe est une « civilisation », mais dont les points d’ancrage sont des terres et des eaux méditerranéennes, puis des tracés de voies et de routes dans l’espace, et enfin des métissages advenus avec les invasions. Febvre s’engage dans une vision filmographique, d’une Europe carolingienne qui doit son unité à l’Église avant tout, une Europe dont le tissé de la trame passe et repasse du politique au religieux, puis à l’économique et au culturel : jusqu’à, après la Renaissance, un XVIIIe siècle au cours duquel l’Europe est devenue une « patrie ». Le grand drame découle de l’événement pourtant positif qu’a été la Révolution, avec l’émergence des nations et des nationalismes, quand deviennent anachroniques les rêves d’équilibre et de paix et quand le malheur surgit d’une succession de guerres intraeuropéennes. L’historien se voit donc récepteur d’une mission, la mission de comprendre comment un sens de l’histoire s’est perdu et comment un autre sens a pu prendre le dessus, et donc empêcher que par l’oubli du passé les chemins de la haine demeurent libres d’accès. D’où un appel, parce que l’Europe est aussi mondiale, à produire de l’espoir, en créant une Europe. L’historien se doit d’inventer une herméneutique que lui seul peut agencer et qu’il a le devoir éthique de formuler, car lui seul connaît les mystères du passé puisqu’il a secoué les blocages d’une histoire engoncée dans ses anachronismes structurels et dans ses illusions facticistes. « Penser l’Europe, pour Febvre, c’est aussi la penser en fonction des cadres de pensées, de l’outillage mental qui forment l’architecture d’une civilisation. »

Avec Eric Hobsbawm examiné par Mark Greengrass, un autre paradigme est à l’œuvre, parce que jouent le marxisme et donc un engagement politique affirmé. L’Europe est présente d’abord parce que l’historien a vécu une vie européenne et qu’en conséquence sa propre expérience formate son écriture, et aussi parce que l’internationalisme faisait partie de lui-même ; mais elle s’estompa dans la mesure où ce sont les mutations du monde qui se lisent pour lui au filtre des événements européens et de la pluralité historique des transformations révolutionnaires que ces derniers suggèrent. Ce qui compte plutôt alors, c’est « la diversité et le caractère indéterminé des “nombreuses Europes” » qui jouent historiquement ; et alors le fait essentiel est que l’Europe, moins qu’un « sujet d’étude », est un « processus ».

Pierre Chaunu

Ces Europes plurielles, elles sont mises en scène par Pierre Chaunu dont Yann Rodier reconstitue les cheminements intellectuels : impossibilité de penser l’Europe moderne sans faire référence à l’européanisation du monde, impossible de penser la modernité européenne sans postuler que ses origines sont d’ordre démographique, impossible de penser l’Europe triomphante sans intégrer dans son histoire sa « révolution » scientifique ; impossible de penser l’Europe sans partir de son histoire religieuse pour assimiler ce qu’a été un « système de civilisation » lisible des débuts de l’âge classique à l’âge des Lumières ; impossible de lire l’histoire du temps présent sans user de la focale de l’histoire du passé, sans donc faire mouvement vers une écriture qui n’a de sens que son présent et qui rêve prophétiquement d’une Europe confédérale marquant une ultime étape de la modernité dans la transition de l’État nation à une communauté humaine du futur. Une Europe qui transcenderait l’angoisse d’une décadence que l’histoire suggère aussi à l’historien…

L’itinéraire de Jean-Baptiste Duroselle retient ensuite l’attention de Laurence Badel. Flexible et évolutive au fur et à mesure que les années avancent, l’histoire se fixe la visée de venir en appui de la construction européenne, jusqu’à aller vers la vision d’une identité de longue durée qui serait celle d’une « civilisation européenne » intégratrice. « En historien engagé, Duroselle alimente le topos de l’heure, celui de l’Europe “close”, de l’Europe-forteresse qui s’est développé au tournant des années 1980-1990, en Europe et sur d’autres continents et, contre “Bruxelles”, il prend position pour la transformation de l’Europe en une confédération qui respecterait la diversité des cultures et institutions nationales et serait susceptible de susciter la “passion des peuples”. »

Cette succession de grandes figures s’achève avec Jacques Le Goff. Être historien de l’Europe médiévale, c’était, selon Jacques Chiffoleau, entrer dans un monde parallèle de l’Europe scindée par un mur et dire que ce mur n’était pas inéluctable. Aborder ensuite l’histoire de l’Europe médiévale par le biais de l’anthropologie, c’était briser les clivages de frontières temporelles et spatiales, briser des champs épistémologiques étroits et dépassés. Enfin quand commence à s’obscurcir ou se complexifier l’horizon européen, écrire l’histoire, c’était écrire une histoire pour l’Europe. « Faire l’Europe par l’histoire et imaginer ce que peut être l’Europe, dans l’oscillation entre unité et diversité, à travers ce qu’a pu être son Moyen Âge – peut-être mythifié, euphémisé toutefois. Une histoire qui n’est pas d’abord politique mais plutôt culturelle, même si les difficultés de la construction européenne renvoient toujours au poids des états nationaux. »

Ainsi se clôt ce livre, sur l’hypothèse que si aujourd’hui il y a une crise du projet européen, c’est aussi parce que l’histoire n’accomplit plus son travail…, qu’elle tend à ne pas poursuivre dans les chemins parcourus au XXe siècle par de grands historiens en dépassant leurs intuitions : c’est-à-dire en appréhendant l’Europe non pas comme une fin, mais comme le premier pallier d’une anthropologie humaniste de la globalité permettant d’aller dans un second mouvement vers la certitude d’une universalité

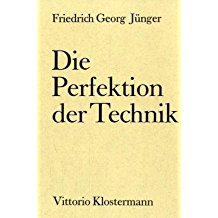

Denis Crouzet (dir.), Historiens d’Europe, historiens de l’Europe. Défense et illustration de l’histoire de l’Europe, Ceyzérieu, Champ Vallon, 5 octobre 2017, 388 p., ici p. 7-21.

Reproduction avec l’aimable autorisation de l’auteur et de Champ Vallon. En dehors des italiques, les emphases sont celles du GEG.

Denis Crouzet est professeur d’histoire moderne à l’université Paris-Sorbonne, titulaire de la chaire d’histoire du XVIe siècle, Corresponding Fellow de la British Academy et auteur d’une œuvre immense consacrée à l’anthropologie des violences religieuses, aux processus de pacification en Europe, à l’histoire des imaginaires et à la pensée politique des débuts de l’époque moderne. Ses ouvrages incluent notamment Les guerriers de Dieu : la violence au temps des troubles de religion, vers 1525-vers 1610 (Champ Vallon, 1990, rééd. 2005), La nuit de la Saint-Barthélemy : un rêve perdu de la Renaissance (Fayard, 1994), La Sagesse et le Malheur : Michel de l’Hospital, chancelier de France (Champ Vallon, 1998), Dieu en ses royaumes : une histoire des guerres de Religion (Champ Vallon, 2008) et Charles Quint : empereur d’une fin des temps (Odile Jacob, 2016). Avec Jean-Marie Le Gall, il est également l’auteur d’un essai sur le rôle que peut jouer l’histoire dans la compréhension de la violence sacrale contemporaine (Au péril des guerres de Religion, PUF, 2015).

Nous reviendrons prochainement plus en détail avec Denis Crouzet sur le contenu de l’ouvrage et sur le tissage de nouveaux liens entre histoire et géopolitique de l’Europe. L’abonnement à notre lettre hebdomadaire vous permettra d’en être tenu informé.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

La même constatation d’une situation de relative déshérence historiographique et surtout de la priorité donnée au choix de coupures par périodes (Renaissance, XVIIe siècle) peut être constatée pour ce qui est de la recherche anglo-saxonne, après les deux volumes de l’History of Europe de H. A. L. Fisher (Londres, 1935). Citons l’exemple de la Short Oxford History of Europe qui, si elle est récente, n’en est pas moins très traditionnelle dans sa conception clivant le passé en grandes séquences classiques si ce n’est anachronisantes, à commencer par « Classical Greece » ou « Roman Europe » ; citons aussi, plus originales, les New Approaches to European History de Cambridge Uni- versity Press et les Fontana History of Europe Series qui reposent sur un projet thématico-chronologique. À quoi s’ajoute The Penguin History of Europe, de J. M. Roberts (1996), fort heureusement renouvelée dans les Penguin History of Europe Series grâce aux contributions de grands spécialistes comme Chris Wickham ou Mark Greengrass. Là est le paradoxe, c’est la Grande-Bretagne du Brexit d’aujourd’hui qui a donné récemment les ouvrages scientifiques les plus parachevés sur une Europe désanachronisée et pensée comme une totalité d’histoire ayant fonctionné plus sur des connexions que sur des spécificités ou sur des collections de particularités. Pour aller dans cette direction, l’histoire de l’Europe se trouve travaillée outre-Manche surtout systématiquement sur le plan de l’histoire économique, avec The Cambridge Economic History of Europe et The Fontana Economic History of Europe. Un peu à part, original, et soupçonné aujourd’hui d’européo-centrisme parce que donnant le primat à la question de l’exceptionnalité du continent désormais passé de mode, il y a le livre important d’Eric Jones, The European Miracle (Cambridge, 1981) à l’inverse du plus superficiel Europe. A History, de Norman Davies (Oxford, 1996). Il faudrait signaler encore Eugen Weber et Une histoire de l’Europe, Paris (2 vol., Paris, 1986-1987), qui insiste sur le concept postromantique d’héritage légué au monde mais noie le lecteur sous une avalanche factuelle donnant une certaine invisibilité à l’objet même Europe.

La même constatation d’une situation de relative déshérence historiographique et surtout de la priorité donnée au choix de coupures par périodes (Renaissance, XVIIe siècle) peut être constatée pour ce qui est de la recherche anglo-saxonne, après les deux volumes de l’History of Europe de H. A. L. Fisher (Londres, 1935). Citons l’exemple de la Short Oxford History of Europe qui, si elle est récente, n’en est pas moins très traditionnelle dans sa conception clivant le passé en grandes séquences classiques si ce n’est anachronisantes, à commencer par « Classical Greece » ou « Roman Europe » ; citons aussi, plus originales, les New Approaches to European History de Cambridge Uni- versity Press et les Fontana History of Europe Series qui reposent sur un projet thématico-chronologique. À quoi s’ajoute The Penguin History of Europe, de J. M. Roberts (1996), fort heureusement renouvelée dans les Penguin History of Europe Series grâce aux contributions de grands spécialistes comme Chris Wickham ou Mark Greengrass. Là est le paradoxe, c’est la Grande-Bretagne du Brexit d’aujourd’hui qui a donné récemment les ouvrages scientifiques les plus parachevés sur une Europe désanachronisée et pensée comme une totalité d’histoire ayant fonctionné plus sur des connexions que sur des spécificités ou sur des collections de particularités. Pour aller dans cette direction, l’histoire de l’Europe se trouve travaillée outre-Manche surtout systématiquement sur le plan de l’histoire économique, avec The Cambridge Economic History of Europe et The Fontana Economic History of Europe. Un peu à part, original, et soupçonné aujourd’hui d’européo-centrisme parce que donnant le primat à la question de l’exceptionnalité du continent désormais passé de mode, il y a le livre important d’Eric Jones, The European Miracle (Cambridge, 1981) à l’inverse du plus superficiel Europe. A History, de Norman Davies (Oxford, 1996). Il faudrait signaler encore Eugen Weber et Une histoire de l’Europe, Paris (2 vol., Paris, 1986-1987), qui insiste sur le concept postromantique d’héritage légué au monde mais noie le lecteur sous une avalanche factuelle donnant une certaine invisibilité à l’objet même Europe. On peut, entre autres travaux individuels ou collectifs, ajouter à cette sphère d’écriture Krzysztof Pomian, L’Europe et ses nations (Paris, 1990), puis Jacques Le Goff, La Vieille Europe et la nôtre (Paris, 1994) ou L’Europe est-elle née au Moyen Âge ? (Paris, Seuil, 2003). L’ouvrage de Denis de Rougemont, Vingt-huit siècles de l’Europe, la conscience européenne à travers les textes d’Hésiode à nos jours (Paris, 1961), est un produit militant issu de la réflexion de l’un des fondateurs du projet européen de l’après-1945. Notons encore Identités nationales et conscience européenne, sous la direction de Joseph Rovan et Gilbert Krebs (Paris, 1992). Et encore, L’Europe dans son histoire. La vision d’Alphonse Dupront, publié par François Crouzet et François Furet (Paris, 1998). Ou Penser l’Europe, d’Edgar Morin (Paris, 1987), qui met l’accent sur la complexité européenne, et sur le dialogue des pluralités ou l’interculturalité étant le moteur interne de l’histoire de l’Europe, « unitas multiplex ».

On peut, entre autres travaux individuels ou collectifs, ajouter à cette sphère d’écriture Krzysztof Pomian, L’Europe et ses nations (Paris, 1990), puis Jacques Le Goff, La Vieille Europe et la nôtre (Paris, 1994) ou L’Europe est-elle née au Moyen Âge ? (Paris, Seuil, 2003). L’ouvrage de Denis de Rougemont, Vingt-huit siècles de l’Europe, la conscience européenne à travers les textes d’Hésiode à nos jours (Paris, 1961), est un produit militant issu de la réflexion de l’un des fondateurs du projet européen de l’après-1945. Notons encore Identités nationales et conscience européenne, sous la direction de Joseph Rovan et Gilbert Krebs (Paris, 1992). Et encore, L’Europe dans son histoire. La vision d’Alphonse Dupront, publié par François Crouzet et François Furet (Paris, 1998). Ou Penser l’Europe, d’Edgar Morin (Paris, 1987), qui met l’accent sur la complexité européenne, et sur le dialogue des pluralités ou l’interculturalité étant le moteur interne de l’histoire de l’Europe, « unitas multiplex ». On pourrait encore évoquer le centrage sur la démographie, avec l’Histoire des populations de l’Europe éditée par Jean-Pierre Bardet et Jacques Dupaquier (3 vol., Paris, 1997), sur l’histoire de l’écosystème, avec l’Histoire de l’environnement européen de Robert Delort (préface de Jacques Le Goff, Paris, 2001). L’Europe peut encore s’écrire dans la longue durée de son histoire économique tendant vers une « unité organique » malgré ses « diversités », avec L’Histoire de l’économie européenne 1000-2000 de François Crouzet (Paris, 2000) : « On essaiera constamment de considérer l’Europe comme un ensemble, et de prêter attention aux relations entre ses diverses parties : au commerce intra-européen, qui s’est développé de bonne heure, notamment sur la base des dotations différentes en ressources de l’Europe du Nord et de celle du Sud ; à la diffusion des institutions, des organisations et des technologies, aux migrations de main-d’œuvre et de capitaux. On recherchera les forces qui ont rapproché les régions européennes et contribué à créer une économie européenne intégrée – même si ce ne fut que de façon lâche. Cependant, ni les forces centrifuges, ni les rapports avec le monde extérieur ne seront négligés… ». D’autres enquêtes se sont fixées dans la problématique de Les Racines de l’identité européenne, de Francis Dumont (Paris, 1999) ou de La Conscience européenne au XVIe siècle de Françoise Autrand et Nicole Cazauran (éd.) (Paris, 1983) ; ou dans le champ de l’histoire des relations internationales avec L’Ordre européen du XVIe au XXe siècle, dirigé par Georges-Henri Soutou (Paris, 1998) ou La Société des princes (Paris, 1999), de Lucien Bély.

On pourrait encore évoquer le centrage sur la démographie, avec l’Histoire des populations de l’Europe éditée par Jean-Pierre Bardet et Jacques Dupaquier (3 vol., Paris, 1997), sur l’histoire de l’écosystème, avec l’Histoire de l’environnement européen de Robert Delort (préface de Jacques Le Goff, Paris, 2001). L’Europe peut encore s’écrire dans la longue durée de son histoire économique tendant vers une « unité organique » malgré ses « diversités », avec L’Histoire de l’économie européenne 1000-2000 de François Crouzet (Paris, 2000) : « On essaiera constamment de considérer l’Europe comme un ensemble, et de prêter attention aux relations entre ses diverses parties : au commerce intra-européen, qui s’est développé de bonne heure, notamment sur la base des dotations différentes en ressources de l’Europe du Nord et de celle du Sud ; à la diffusion des institutions, des organisations et des technologies, aux migrations de main-d’œuvre et de capitaux. On recherchera les forces qui ont rapproché les régions européennes et contribué à créer une économie européenne intégrée – même si ce ne fut que de façon lâche. Cependant, ni les forces centrifuges, ni les rapports avec le monde extérieur ne seront négligés… ». D’autres enquêtes se sont fixées dans la problématique de Les Racines de l’identité européenne, de Francis Dumont (Paris, 1999) ou de La Conscience européenne au XVIe siècle de Françoise Autrand et Nicole Cazauran (éd.) (Paris, 1983) ; ou dans le champ de l’histoire des relations internationales avec L’Ordre européen du XVIe au XXe siècle, dirigé par Georges-Henri Soutou (Paris, 1998) ou La Société des princes (Paris, 1999), de Lucien Bély.

On peut poursuivre avec Ernst Kantorowicz et son parcours qui le mène tout d’abord de Frédéric II, empereur-sauveur, et d’un attachement à un Reich imaginé régénérateur, de la foi dans le génie de la nation allemande, au boycott de ses cours par les étudiants nazis, puis à son exfiltration d’Allemagne. Parvenu aux USA et nommé à Berkeley, il doit affronter le maccarthysme en se faisant le défenseur d’une conception européenne de l’université à laquelle il reste attaché. Et son œuvre, qui est alimentée de multiples sources puisées dans des espaces et des temps différents, Gérald Chaix l’écrit, dépasse les évidences dans un paradoxe apparent : parce que sa « perspective est d’emblée européenne, même si, dans sa lecture impériale, il attribue à une Allemagne imprégnée de romanité un destin privilégié. Elle le demeure lorsque les circonstances, mais aussi ses propres choix, l’en éloignent. Elle se précise lorsque étudiant la conception anglaise des deux corps du roi, il situe explicitement celle-ci dans la construction chronologique et géographique d’une histoire européenne nullement close sur elle-même. » Kantorowicz pense par l’Europe. L’Europe conditionne sa pensée et son inventivité d’historien.

On peut poursuivre avec Ernst Kantorowicz et son parcours qui le mène tout d’abord de Frédéric II, empereur-sauveur, et d’un attachement à un Reich imaginé régénérateur, de la foi dans le génie de la nation allemande, au boycott de ses cours par les étudiants nazis, puis à son exfiltration d’Allemagne. Parvenu aux USA et nommé à Berkeley, il doit affronter le maccarthysme en se faisant le défenseur d’une conception européenne de l’université à laquelle il reste attaché. Et son œuvre, qui est alimentée de multiples sources puisées dans des espaces et des temps différents, Gérald Chaix l’écrit, dépasse les évidences dans un paradoxe apparent : parce que sa « perspective est d’emblée européenne, même si, dans sa lecture impériale, il attribue à une Allemagne imprégnée de romanité un destin privilégié. Elle le demeure lorsque les circonstances, mais aussi ses propres choix, l’en éloignent. Elle se précise lorsque étudiant la conception anglaise des deux corps du roi, il situe explicitement celle-ci dans la construction chronologique et géographique d’une histoire européenne nullement close sur elle-même. » Kantorowicz pense par l’Europe. L’Europe conditionne sa pensée et son inventivité d’historien. Penser par l’Europe, mais aussi penser pour l’Europe. La seconde partie du livre s’attache à une autre modalité de mise en problème historique de l’Europe. Avec en ouverture bien sûr, Johan Huizinga qui traduit une volonté d’écrire une histoire de l’Europe dans la perspective d’une fin de durée, un « automne » du Moyen Âge d’abord franco-bourguignon caractérisé par une exacerbation d’affects contradictoires, l’exubérance d’une vie contrastée mais commune. Et ensuite, après les idéaux chevaleresques, il y eut les idéaux renaissants qui transcendèrent la diversité des hommes et des nations. Et Jean-Baptiste Delzant d’insister sur un point : l’Europe de Huizinga est d’abord un « esprit » transhistorique qui en appelle à un « besoin d’unité civilisatrice » et donc à une exigence morale partagée et conceptualisée, entre autres, par Érasme. L’histoire apparaît tel un bouclier, une mise en défense contre les idéologies négatives ultranationalistes, contre les ruines qui en adviennent et en sont advenues au cours du XXe siècle, et pour Huyzinga, de ce fait, elle a un avenir et un présent : « donner corps à une unité désirée… ».

Penser par l’Europe, mais aussi penser pour l’Europe. La seconde partie du livre s’attache à une autre modalité de mise en problème historique de l’Europe. Avec en ouverture bien sûr, Johan Huizinga qui traduit une volonté d’écrire une histoire de l’Europe dans la perspective d’une fin de durée, un « automne » du Moyen Âge d’abord franco-bourguignon caractérisé par une exacerbation d’affects contradictoires, l’exubérance d’une vie contrastée mais commune. Et ensuite, après les idéaux chevaleresques, il y eut les idéaux renaissants qui transcendèrent la diversité des hommes et des nations. Et Jean-Baptiste Delzant d’insister sur un point : l’Europe de Huizinga est d’abord un « esprit » transhistorique qui en appelle à un « besoin d’unité civilisatrice » et donc à une exigence morale partagée et conceptualisée, entre autres, par Érasme. L’histoire apparaît tel un bouclier, une mise en défense contre les idéologies négatives ultranationalistes, contre les ruines qui en adviennent et en sont advenues au cours du XXe siècle, et pour Huyzinga, de ce fait, elle a un avenir et un présent : « donner corps à une unité désirée… ».

Su molti dei nomi studiati da Colombo grava ancora una damnatio memoriae non scalfita dal tempo, su altri il pregiudizio è caduto lasciando spazio ad analisi più riflessive e distaccate. Del resto, come avverte l’autore, gli stessi intellettuali che avevano creduto nel sogno nazionalrivoluzionario di Hitler e Mussolini scelsero destini diversi nel dopoguerra: “C’è chi fuggirà da quel sogno diventato incubo, e tenterà di nascondere per tutta la vita le sue simpatie giovanili, come Lorenz. Chi invece, come Evola, non rinuncerà alle sue idee neanche dopo il 1945… Pound, infine, negli anni della vecchiaia si chiuderà in un mutismo enigmatico. Un tempus tacendi che segnerà la fine definitiva del tragico sogno“.

Su molti dei nomi studiati da Colombo grava ancora una damnatio memoriae non scalfita dal tempo, su altri il pregiudizio è caduto lasciando spazio ad analisi più riflessive e distaccate. Del resto, come avverte l’autore, gli stessi intellettuali che avevano creduto nel sogno nazionalrivoluzionario di Hitler e Mussolini scelsero destini diversi nel dopoguerra: “C’è chi fuggirà da quel sogno diventato incubo, e tenterà di nascondere per tutta la vita le sue simpatie giovanili, come Lorenz. Chi invece, come Evola, non rinuncerà alle sue idee neanche dopo il 1945… Pound, infine, negli anni della vecchiaia si chiuderà in un mutismo enigmatico. Un tempus tacendi che segnerà la fine definitiva del tragico sogno“.

Schleiermacher thought that the Romantics’ criticism of religion applied only to external factors such as dogmas, opinions, and practices, which determine the social and historical form of religions. Religion was about the source of the external factors. He noted that, “as the childhood images of God and immortality vanished before my doubting eyes, piety remained.”

Schleiermacher thought that the Romantics’ criticism of religion applied only to external factors such as dogmas, opinions, and practices, which determine the social and historical form of religions. Religion was about the source of the external factors. He noted that, “as the childhood images of God and immortality vanished before my doubting eyes, piety remained.” The dialogue begins with the historical criticism of the Enlightenment, claiming that although the Christmas celebration is a powerful and vital present reality, it is hardly based on historical fact. The birth of Christ is only a legend. Schleiermacher rejects the historical empiricism of the Enlightenment since it results only in the discovery of insignificant causes for important events and the outcome of history becomes accidental. This is not good enough, “for history derives from epic and mythology, and these clearly lead to the identity of appearance and idea.” Therefore, he says, “it is precisely the task of history to make the particular immortal. Thus, the particular first gets its position and distinct existence in history by means of a higher treatment.”

The dialogue begins with the historical criticism of the Enlightenment, claiming that although the Christmas celebration is a powerful and vital present reality, it is hardly based on historical fact. The birth of Christ is only a legend. Schleiermacher rejects the historical empiricism of the Enlightenment since it results only in the discovery of insignificant causes for important events and the outcome of history becomes accidental. This is not good enough, “for history derives from epic and mythology, and these clearly lead to the identity of appearance and idea.” Therefore, he says, “it is precisely the task of history to make the particular immortal. Thus, the particular first gets its position and distinct existence in history by means of a higher treatment.” Schleiermacher and Fichte based their idea of university on the transcendental idealist philosophy and its new conception of science. A mere technical academy could not represent the totality of knowledge. According to Schleiermacher, “the totality of knowledge should be shown by perceiving the principles as well as the outline of all learning in such a way that one develops the ability to pursue each sphere of knowledge on his own.” All genuine and creative scholarly work must be rooted in the scientific spirit as expressed in philosophy.

Schleiermacher and Fichte based their idea of university on the transcendental idealist philosophy and its new conception of science. A mere technical academy could not represent the totality of knowledge. According to Schleiermacher, “the totality of knowledge should be shown by perceiving the principles as well as the outline of all learning in such a way that one develops the ability to pursue each sphere of knowledge on his own.” All genuine and creative scholarly work must be rooted in the scientific spirit as expressed in philosophy.

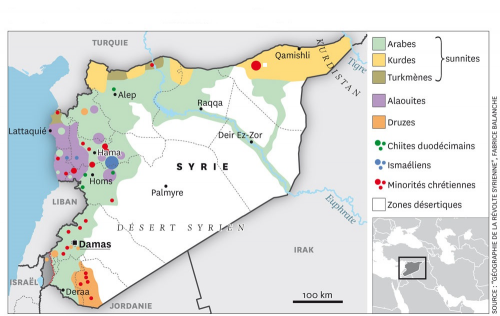

Le mot mentionne ensuite une communauté ethno-religieuse surtout présente en Syrie et au Liban. Abdallah Naaman étudie ce groupe peu connu pour lequel il remplace les lettres o et u par un w : Les Alawites. Histoire mouvementée d’une communauté mystérieuse (Éditions Érick Bonnier, coll. « Encre d’Orient », 359 p., 20 €). L’ouvrage se compose de deux parties inégales. L’une revient longuement sur le déclenchement de la guerre civile syrienne. Démocrate et laïque, l’auteur récuse les supposés rebelles et vrais terroristes islamistes sans pour autant soutenir le gouvernement légitime du président Bachar al-Assad. Très critique envers Israël et l’Arabie Saoudite, il n’hésite pas à qualifier Nicolas Sarkozy de « burlesque », Laurent Fabius de « mouche du coche (p. 200) » et à dénoncer le philosophe botulien Bernard-Henri Lévy qu’il considère comme un « affabulateur (p. 201) » et un « malhonnête homme à la chemise blanche immaculée que d’aucuns traitent d’imposteur intellectuel de la nouvelle philosophie (p. 201) ». Cependant, hors de ces quelques vérités très incorrectes, l’autre partie s’attache à découvrir un peuple mystérieux.

Le mot mentionne ensuite une communauté ethno-religieuse surtout présente en Syrie et au Liban. Abdallah Naaman étudie ce groupe peu connu pour lequel il remplace les lettres o et u par un w : Les Alawites. Histoire mouvementée d’une communauté mystérieuse (Éditions Érick Bonnier, coll. « Encre d’Orient », 359 p., 20 €). L’ouvrage se compose de deux parties inégales. L’une revient longuement sur le déclenchement de la guerre civile syrienne. Démocrate et laïque, l’auteur récuse les supposés rebelles et vrais terroristes islamistes sans pour autant soutenir le gouvernement légitime du président Bachar al-Assad. Très critique envers Israël et l’Arabie Saoudite, il n’hésite pas à qualifier Nicolas Sarkozy de « burlesque », Laurent Fabius de « mouche du coche (p. 200) » et à dénoncer le philosophe botulien Bernard-Henri Lévy qu’il considère comme un « affabulateur (p. 201) » et un « malhonnête homme à la chemise blanche immaculée que d’aucuns traitent d’imposteur intellectuel de la nouvelle philosophie (p. 201) ». Cependant, hors de ces quelques vérités très incorrectes, l’autre partie s’attache à découvrir un peuple mystérieux.