Il y a exactement vingt ans, Pierre Gripari nous quittait. Les plus anciens lecteurs du Spectacle du Monde se souviennent certainement des portraits d’écrivains qu’il y donnait. Jean Dutourd a dit de lui qu’il fut, avec Alexandre Vialatte – autre collaborateur de haut vol de notre revue –, le grand méconnu des lettres françaises. Il est temps de le (re)découvrir.

Les gens ne veulent pas le croire, mais les Martiens existent, un homme les a rencontrés : l’écrivain Pierre Gripari. On raconte même qu’il en était peut-être un, lui l’auteur d’une mémorable trilogie martienne (Moi, Mitounet-Joli, 1982 ; le Septième Lot, 1986 ; et les Derniers Jours de l’Eternel, 1990). Tous ceux qui l’ont côtoyé vous le diront : Gripari ne vivait pas vraiment sur Terre, il y campait seulement, créature en transit, emprisonné dans le corps d’un auteur français, né, selon l’état civil, à Paris, le 7 janvier 1925, et mort – enlevé plutôt – dans cette même ville, le 23 décembre 1990, il y a tout juste vingt ans. Sur les registres, était inscrit qu’il avait pour mère et père « une sorcière viking » et « un magicien grec », mais en réalité, c’était un orphelin des étoiles qui a fait une longue escale sur notre planète.

Peut-être y a-t-il eu un malencontreux accident à sa naissance, un peu comme dans La vie est un long fleuve tranquille. On aurait alors interverti les bébés. Gripari se serait ainsi retrouvé avec des parents terrestres, lui l’extraterrestre. Disant cela, on ne brode pas sur un thème cher à l’auteur des Rêveries d’un Martien en exil (1976). Non, la révocation du monde est le préalable à l’œuvre griparienne. Elle est née d’un coup d’Etat : il n’y a rien, pas d’origine divine, ni d’ascendance humaine.

De là vient que les héros de Gripari sont des enfants, des fées, des lutins, des animaux, des centaures et des surhommes. Telle était sa vraie famille. Son oeuvre est traversée par une volonté d’exhominisation. Les personnages aux noms et prénoms si cocasses qui la jalonnent le prouvent abondamment : dans la Vie, la Mort et la Résurrection de Socrate-Marie Gripotard (1968), le héros éponyme est un mutant nietzschéen ; Charles Creux, dans Frère Gaucher ou le Voyage en Chine (1975), un fantôme ; Roman Branchu, dans les Vies parallèles de Roman Branchu (1978), une probabilité déroutante dans un univers de possibles.

Tout apparente Gripari aux créatures mythologiques dont il peuplait son univers, tour à tour cyclope, mère-grand, Petit Poucet, Chat botté, Merlin l’enchanteur. Un homme à la croisée des mondes, vivant dans plusieurs dimensions, chacune d’entre elles communiquant avec les autres. C’est cela le fantastique : la pluralité des mondes, l’aptitude à glisser d’un univers à l’autre, du réel à l’imaginaire, du mythique au fantastique, du trivial au poétique.

Gripari commençait sa phrase sur Terre et la finissait sur Mars. Ou plutôt l’inverse, tant il a su renverser la perspective habituelle de la science-fiction, un peu à la manière de Montesquieu dans les Lettres persanes : ce ne sont plus des hommes qui partent à la découverte des extraterrestres, mais des Martiens qui viennent explorer cette espèce étrange – l’homme.

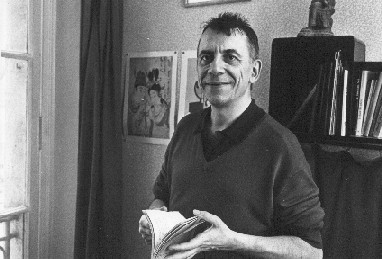

Dans l’excellent petit ouvrage qu’ils viennent de lui consacrer, à l’occasion du vingtième anniversaire de sa disparition, Anne Martin-Conrad et Jacques Marlaud nous rappellent quel homme étrange il fut, lui qui mena une vie ascétique de vieux garçon dans de modestes meublés sans confort, moitié Diogène des temps modernes vivant dans un tonneau sommairement aménagé, moitié franciscain parlant d’égal à égal à frère Martien et soeur Sorcière. C’est là qu’il vivait, dans un dénuement heureux, avec une table en Formica, pour prendre de frugaux repas, écrire et rêver, habillé comme un chiffonnier d’Emmaüs de chandails mités et de chemises qui sortaient du pantalon, toujours en espadrilles, été comme hiver, comme échappé d’un film de Jacques Tati, animal pataud habité par la grâce des poètes, dont le sourire désarmait les douaniers et les enfants.

Dans l’excellent petit ouvrage qu’ils viennent de lui consacrer, à l’occasion du vingtième anniversaire de sa disparition, Anne Martin-Conrad et Jacques Marlaud nous rappellent quel homme étrange il fut, lui qui mena une vie ascétique de vieux garçon dans de modestes meublés sans confort, moitié Diogène des temps modernes vivant dans un tonneau sommairement aménagé, moitié franciscain parlant d’égal à égal à frère Martien et soeur Sorcière. C’est là qu’il vivait, dans un dénuement heureux, avec une table en Formica, pour prendre de frugaux repas, écrire et rêver, habillé comme un chiffonnier d’Emmaüs de chandails mités et de chemises qui sortaient du pantalon, toujours en espadrilles, été comme hiver, comme échappé d’un film de Jacques Tati, animal pataud habité par la grâce des poètes, dont le sourire désarmait les douaniers et les enfants.

Il était volontiers scabreux, souvent saugrenu, toujours lunaire, pareil, finalement, à son Pierrot la Lune (1963), titre de son premier livre, sa seule autobiographie. Il tutoyait tout le monde, à commencer par son lecteur, qu’il installait d’emblée dans une relation de fraternelle complicité. La voie haut perchée, faite pour réciter des fables d’Esope ou contrefaire des bruits d’animaux, il n’avait pas son pareil pour lire des textes, coassant, barrissant, mugissant, autant qu’il parlait. Ensuite, il partait d’un rire « hénaurme ». Ce n’était pas un rire, mais l’expectoration d’un ogre jovial. Tout était inattendu chez lui, comme en physique aléatoire. On ne savait jamais quelle direction allait emprunter sa conversation, ni quels contours dessineraient ses récits. Il était unique – on l’est tous, mais lui l’était superlativement. C’était un ovni qui professait des idées hétérodoxes dans tous les domaines, se définissant de préférence comme un homosexuel athée, misogyne et fasciste. Ce n’était pas une carte de visite qu’il vous jetait à la face, mais un casier judiciaire. Il était tout cela, certes, mais d’une façon si inhabituelle, si peu convenue, si peu bornée, qu’il intriguait et subjuguait jusqu’aux hétérosexuels les plus intransigeants et aux chrétiens les plus fervents.

Gripari a payé un lourd tribut à son inimitable liberté de ton. Quoiqu’il ait laissé derrière lui quelques-uns des livres les plus originaux de notre temps, la plupart de ses ouvrages sont confinés aux rayons pour enfants. L’oeuvre pour adultes, qui réunit pourtant des romans bizarres, des fantaisies géniales, des contes loufoques ou profonds, des dialogues hilarants, des pièces de théâtre ambitieuses ou légères – son premier succès a d’ailleurs été sur les planches, le Lieutenant Tenant (1962), qui lui vaudra l’amitié de Michel Déon –, des poèmes facétieux et drolatiques, cette oeuvre pléthorique reste dans l’ombre des Contes de la rue Broca (1967), adaptés à la télévision, et des Contes de la Folie- Méricourt (1983).

A l’heure où l’oeuvre de Sade a quitté l’enfer des bibliothèques, celle de Gripari est ainsi venue l’y remplacer. On la tient soigneusement à l’écart, trop dérangeante, comme sa Patrouille du conte (1982), parabole étourdissante et prémonitoire du politically correct à la française : une patrouille d’enfants reçoit pour mission d’aller faire la police dans le royaume si peu démocratique du conte ; sa feuille de route : l’épurer de tous ses reliquats féodaux et monarchiques. L’affaire tourne mal, comme on s’en doute.

Gripari racontait des histoires dont il était sûr « qu’elles ne sont jamais arrivées, qu’elles n’arriveront jamais », vivant de plain-pied dans le merveilleux, sans jamais tenir compte de l’absurde convention qui veut qu’il n’y ait qu’un niveau de réalité. Dès lors, tout devenait possible, la Terre pouvait être plate et l’Amérique ne pas exister, comme dans l’Incroyable Equipée de Phosphore Noloc (1964).

Ses romans sont des bric-à-brac enchantés, des bibliothèques remplies de vieux grimoires qui s’animent comme dans des histoires de revenants. Il y avait en lui quelque chose de jungien en cela qu’il considérait le matériau des contes et des mythes comme des invariants inscrits depuis toujours dans l’inconscient collectif de l’humanité. A charge pour nous de les revisiter. Ce qu’il fit. Mythologie grecque, cycle arthurien, sagas scandinaves, romantiques allemands (Hoffmann en tête), tout y passa.

On trouvait de tout dans sa boîte à malices d’écrivain. Il lisait dans le texte quantité de littératures étrangères. Cette curiosité le conduisit à écrire du théâtre selon les règles du Nô japonais, des poèmes érotiques, des romans par lettres, des fabliaux médiévaux, des chansons de geste. Mais la forme qu’il chérissait le plus, c’est le conte ; un genre qui remonte à la plus Haute Antiquité et à la plus lointaine enfance, à la fois sans âge et éternellement jeune. Ainsi de l’auteur de l’Arrière-Monde et autres diableries (1972) et des Contes cuistres (1987), grand prix de la nouvelle de l’Académie française. On ne le dira jamais assez, Gripari a été pour le XXe siècle ce que furent Charles Perrault pour le XVIIe siècle et les frères Grimm pour le XIXe siècle : le conteur, le diseur, le fabuliste de notre temps, celui qui donne à l’homme son indispensable nourriture onirique, l’architecte de nos songes.

C’était un décathlonien de la littérature, un auteur complet qui exerçait son art en généraliste, s’essayant à tous les genres littéraires, qu’il respectait scrupuleusement. Sur la forme. Pas sur le fond. C’est le fond qui est original chez lui. Sa langue procédait plus de la tradition orale que des écritures sophistiquées, privilégiant le rythme à la mélodie et l’expression dramatique aux effets de style. Grec d’origine, mais non byzantin. Si d’ailleurs il restait méditerranéen par la forme – claire et précise –, par le fond, il était celte, germanique, septentrional.

De toute sa tribu de personnages, un être, entre tous, se détache : Dieu. C’était pour lui le personnage de fiction par excellence, il le mettait en scène inlassablement. Yahvé, Zeus, Osiris, Baal, Allah, toujours le même, toujours recommencé, avec ou sans barbe, cruel ou facétieux. On pourrait presque dire de son œuvre qu’elle est une exégèse sauvage et romancée de la Bible, qu’il a lue et relue avec une sorte de virginité critique, même si sa lecture n’est pas sans rappeler celle de Marcion, l’un des premiers hérésiarques du christianisme.

Dans son esprit, la création du monde s’apparentait à un faux départ. Au commencement, il y eut un raté céleste, un couac divin, un accident originel, qu’il s’agisse de la Genèse, du big bang ou de la naissance de l’auteur. Quelque chose a cloché. Dieu créa le monde et il vit que cela n’était pas bon. Il faut tout reprendre à zéro, depuis le début. C’est là qu’intervient Gripari, démiurge bricoleur muni de sa baguette magique, comme dans Diable, Dieu et autres contes de menterie (1965).

Avec cela, joyeusement pessimiste. Si la vérité, c’est le vide absolu – et elle n’était rien d’autre pour lui –, il faut de toute urgence remplir ce vide, faute de quoi il nous absorbera, pareil à un trou noir. D’où sa fantaisie potache, ses contrepèteries incessantes, son « oui » nietzschéen au vide autant qu’à la vie. Quoique placidement désespérée, sa philosophie était amicale, allant chercher la sagesse là où elle s’est exprimée avec le plus de vigueur et de sérénité, chez Lucrèce, Maître Eckhart, Marc Aurèle, Epicure et quelques autres. Il a rassemblé leurs dits et paroles dans une anthologie, l’Evangile du rien (1980), qui dessine en creux le visage du récipiendaire, un peu comme dans Frère Gaucher, roman épistolaire où le personnage principal se dégage à partir des lettres qu’il reçoit.

Nul doute que le monde était pour lui froid, hostile, inhospitalier. Mais la littérature est là, qui le réchauffe. De tous les écrivains qu’il lisait et relisait jusqu’à plus soif, avec l’entrain d’un enfant que rien ne peut épuiser, c’était vers Dickens, l’écrivain chaleureux de l’enfance malheureuse, qu’il se tournait le plus souvent. Le vent mauvais, la pluie glacée, l’hiver de la vie s’arrêtent au seuil des livres de Dickens. On pourrait en dire autant de ceux de Gripari.

Gripari est entré en littérature comme on entre en religion. Le grand éditeur de sa vie, Vladimir Dimitrijevic, directeur de l’Age d’Homme, disait que « la littérature a été sa véritable patrie ». Il avait une confiance absolue en elle. « J’écris, confiait-il, pour être aimé longtemps après ma mort, comme j’ai aimé Dickens. J’écris pour faire du bien, comme Jack London m’a fait du bien, à quelques individus que je ne connaîtrai jamais, dont les pensées ne seront pas les miennes, qui vivront dans un monde que je ne puis concevoir. » Lui qui n’est plus, le voilà maintenant pareil à Dickens et Jack London, grand frère qui nous a précédés dans la grande aventure de la vie et se tient, tout sourires, au carrefour des existences, prêt à faire un bout de chemin avec chacun d’entre nous.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Un livre de plus consacré au temps. Au cours des décennies écoulées on n’a jamais autant écrit sur la condition humaine en relation avec le temps. Beaucoup de sociologues prennent au sérieux la temporalité pour essayer de prouver qu’ils pensent. Il ne faut pas les confondre avec des philosophes puissants comme Dilthey, Ortega et Heidegger, dont les œuvres sont centrées sur cela.

Un livre de plus consacré au temps. Au cours des décennies écoulées on n’a jamais autant écrit sur la condition humaine en relation avec le temps. Beaucoup de sociologues prennent au sérieux la temporalité pour essayer de prouver qu’ils pensent. Il ne faut pas les confondre avec des philosophes puissants comme Dilthey, Ortega et Heidegger, dont les œuvres sont centrées sur cela.

Le regard est-il pessimiste en ce qui concerne les réserves naturelles ? Le gaz de schiste n’est-il pas la solution ? Outre le danger de son extraction, et le coût élevé des méthodes les moins intrusives – et qui le restent – les réserves mondiales en pétrole de schiste sont estimées à 4 ans de consommation. Elles ne sont donc pas le moins du monde une relève durable.

Le regard est-il pessimiste en ce qui concerne les réserves naturelles ? Le gaz de schiste n’est-il pas la solution ? Outre le danger de son extraction, et le coût élevé des méthodes les moins intrusives – et qui le restent – les réserves mondiales en pétrole de schiste sont estimées à 4 ans de consommation. Elles ne sont donc pas le moins du monde une relève durable.  Depuis 1997, on a beaucoup parlé de la politique de l’emploi en Europe, les petits bourgeois de la Commission fumant de slogans nouveaux et s’exaltant à propos de l’économie du savoir. Pendant que ces crânes solennels mais creux rédigeaient des rapports, la population s’enfonçait dans la pauvreté. Toutes les industries ont chuté et les syndicats ne font plus rien pour les aider à se maintenir. Le racket fiscal tombe sur les seules entreprises restantes et gérées par des européens de l’ancien temps, car aucune diaspora venue du vaste monde ne paye d’impôts ; les petits fonctionnaires pratiquent l’art du faux, n’ayant plus le courage ni souvent la volonté de traiter ces fraudeurs comme ils le méritent.

Depuis 1997, on a beaucoup parlé de la politique de l’emploi en Europe, les petits bourgeois de la Commission fumant de slogans nouveaux et s’exaltant à propos de l’économie du savoir. Pendant que ces crânes solennels mais creux rédigeaient des rapports, la population s’enfonçait dans la pauvreté. Toutes les industries ont chuté et les syndicats ne font plus rien pour les aider à se maintenir. Le racket fiscal tombe sur les seules entreprises restantes et gérées par des européens de l’ancien temps, car aucune diaspora venue du vaste monde ne paye d’impôts ; les petits fonctionnaires pratiquent l’art du faux, n’ayant plus le courage ni souvent la volonté de traiter ces fraudeurs comme ils le méritent. Trois pays du Nord de l’Europe et deux du Sud ont retenu l’attention des économistes. En Hollande, le partage des tâches a toujours été privilégié : entre hommes et femmes, entre employés à plein temps et à temps partiel. En Finlande, les personnes de plus de 45 ans ont été incitées à rester actives et le moment de la retraite dépend d’un choix personnel. Au Danemark, chaque employé en arrêt de travail, pour quelque raison que ce soit, laisse le temps disponible à un travailleur sans emploi. En Italie, l’innovation a consisté à fonder des bourses du temps. Les individus disposent d’un compte-temps où ils peuvent accumuler ou utiliser des heures, dans le cadre d’une organisation collective du temps de la vie urbaine. Les horaires de fonctionnement des services publics, des entreprises privées, les spécificités des familles ont été mises en synergie dans certaines villes. Enfin, n’oublions pas les possibilités des coopératives dont le pays basque a donné d’excellents exemples. Les coopératives offrent l’opportunité de rassembler professionnels et bénévoles, subventions publiques et contributions privées, afin de satisfaire des besoins solvables ou non. Toute cette ferblanterie sociale ne vaut rien et s’écroule sous le poids de sa propre médiocrité. Aucune élite n’est sélectionnée pour mettre en place, durablement, avec fermeté, les conditions dans lesquelles chacun pourrait mener une vie décente. Le monde de la finance choisit des collaborateurs sans talent, sans esprit, sans rien, hormis l’obscurantisme. Le désert nous rattrape.

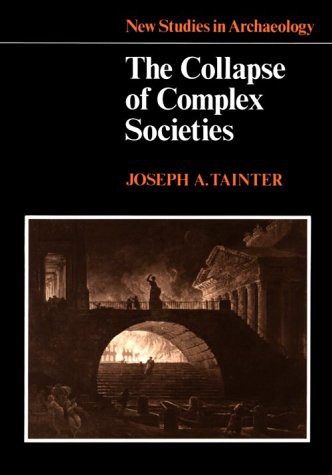

Trois pays du Nord de l’Europe et deux du Sud ont retenu l’attention des économistes. En Hollande, le partage des tâches a toujours été privilégié : entre hommes et femmes, entre employés à plein temps et à temps partiel. En Finlande, les personnes de plus de 45 ans ont été incitées à rester actives et le moment de la retraite dépend d’un choix personnel. Au Danemark, chaque employé en arrêt de travail, pour quelque raison que ce soit, laisse le temps disponible à un travailleur sans emploi. En Italie, l’innovation a consisté à fonder des bourses du temps. Les individus disposent d’un compte-temps où ils peuvent accumuler ou utiliser des heures, dans le cadre d’une organisation collective du temps de la vie urbaine. Les horaires de fonctionnement des services publics, des entreprises privées, les spécificités des familles ont été mises en synergie dans certaines villes. Enfin, n’oublions pas les possibilités des coopératives dont le pays basque a donné d’excellents exemples. Les coopératives offrent l’opportunité de rassembler professionnels et bénévoles, subventions publiques et contributions privées, afin de satisfaire des besoins solvables ou non. Toute cette ferblanterie sociale ne vaut rien et s’écroule sous le poids de sa propre médiocrité. Aucune élite n’est sélectionnée pour mettre en place, durablement, avec fermeté, les conditions dans lesquelles chacun pourrait mener une vie décente. Le monde de la finance choisit des collaborateurs sans talent, sans esprit, sans rien, hormis l’obscurantisme. Le désert nous rattrape. De même que la notion de progrès, celle d’effondrement ou de décadence suppose un jugement porté à partir d’une interprétation. Le choix des éléments importants de l’interprétation suppose à son tour une certaine conception de l’histoire ou de la société. Il est banal de remarquer que le vécu des peuples, comme de tout ce qui existe, connaît des modifications dont certaines se révèlent des dégradations si on les compare à un Etat antérieur qui sert de référence. Le livre de Tainter, qui vient d’être traduit en français alors qu’il a été publié en 1988 présente un intérêt à travers le rôle qu’il fait jouer au concept de rendement décroissant.

De même que la notion de progrès, celle d’effondrement ou de décadence suppose un jugement porté à partir d’une interprétation. Le choix des éléments importants de l’interprétation suppose à son tour une certaine conception de l’histoire ou de la société. Il est banal de remarquer que le vécu des peuples, comme de tout ce qui existe, connaît des modifications dont certaines se révèlent des dégradations si on les compare à un Etat antérieur qui sert de référence. Le livre de Tainter, qui vient d’être traduit en français alors qu’il a été publié en 1988 présente un intérêt à travers le rôle qu’il fait jouer au concept de rendement décroissant. Selon les époques, c’est-à-dire le contexte historique singulier, l’effondrement couvre trois types de phénomènes: La disparition totale d’une civilisation et de la population qui la portait ; la chute d’une civilisation qui transmet une partie de son héritage à d’autres ; la transformation interne d’une civilisation qui abandonne certains de ses traits.

Selon les époques, c’est-à-dire le contexte historique singulier, l’effondrement couvre trois types de phénomènes: La disparition totale d’une civilisation et de la population qui la portait ; la chute d’une civilisation qui transmet une partie de son héritage à d’autres ; la transformation interne d’une civilisation qui abandonne certains de ses traits.

Der evangelische Theologe Karl Richard Ziegert untersucht und kritisiert ausführlich die Rolle der Evangelischen Kirche in Deutschland bei der Entstehung der bundesdeutschen Zivilreligion.

Der evangelische Theologe Karl Richard Ziegert untersucht und kritisiert ausführlich die Rolle der Evangelischen Kirche in Deutschland bei der Entstehung der bundesdeutschen Zivilreligion.

Or le nomadisme est de retour. C’est incontestable. Orsenna a raison et voit juste sur ce point. Le terrorisme islamiste est nomade et s’empare de territoires vastes où ses combattants font du nomadisme. La piraterie, nomadisme des mers est également revenue. Les entreprises qui délocalisent sont nomades, la finance internationale est nomade et surtout le monde de l'internet est par définition un monde nomade. La civilisation sédentaire, quant à elle, doute de ses valeurs.

Or le nomadisme est de retour. C’est incontestable. Orsenna a raison et voit juste sur ce point. Le terrorisme islamiste est nomade et s’empare de territoires vastes où ses combattants font du nomadisme. La piraterie, nomadisme des mers est également revenue. Les entreprises qui délocalisent sont nomades, la finance internationale est nomade et surtout le monde de l'internet est par définition un monde nomade. La civilisation sédentaire, quant à elle, doute de ses valeurs.

Jacqueline de Romilly se base ici sur Sophocle et surtout Thucydide où elle décèle les éléments d’une sagesse politique tendant à des vérités valables pour le présent mais aussi l’avenir.

Jacqueline de Romilly se base ici sur Sophocle et surtout Thucydide où elle décèle les éléments d’une sagesse politique tendant à des vérités valables pour le présent mais aussi l’avenir.