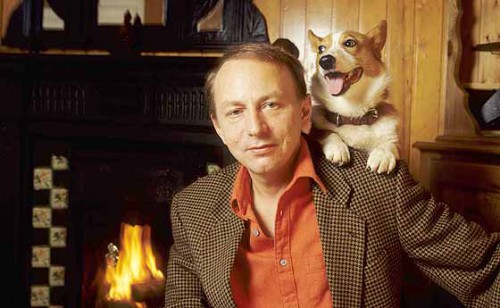

Michel Houellebecq

Michel Houellebecq

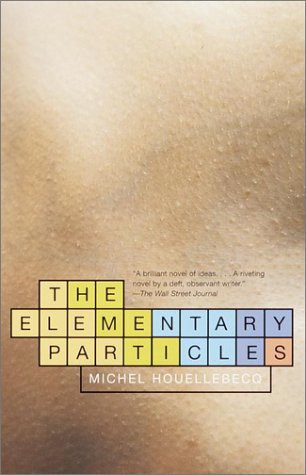

The Elementary Particles [2]

Translated from the French by Frank Wynne

New York: Knopf, 2000

“I get my kicks above the waistline, Sunshine.”[1]

“The universe is nothing but a furtive arrangement of elementary particles. . . . And human actions are as free and as stripped of meaning as the unfettered movements of the elementary particles.” — Michel Houellebecq, H. P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life

“Frolicking has never been so depressing.”—MST3k Episode 609: Coleman Francis’ Skydivers.

It really does seem odd that I have until now managed to avoid reading the novels of Michel Houlelebecq. It’s especially odd I didn’t plunge right in after reading his excellent essay on Lovecraft, [2] and even quoting it my very own first essay on Lovecraft, published right here on Counter Currents.[3] Why, we even share the same year of birth![4]

The appeal of Houellebecq to elements of the Right should be obvious; his enemies seem to be our enemies, from American consumer culture to modernity itself, as well as not just the French versions of PC but French culture itself, at least in its postwar state.[5]

His basic notion is that, contrary to the foolish dreams of the ’68ers, and dogmatically enforced today by both academic and consumer establishments, “The ‘decentred self’ remains a selfish unit; the death of hierarchy merely nurtures the cult of the individual and an incoherent, deviant society.”[6]

These fiercely individualized entities are the elementary particles left to spin aimlessly by the smashing of the bonds of traditional society.

It is interesting to note that the “sexual revolution” was sometimes portrayed as a communal utopia, whereas in fact it was simply another stage in the historical rise of individualism. As the lovely word “household” suggests, the couple and the family would be the last bastion of primitive communism in liberal society. The sexual revolution was to destroy these intermediary communities, the last to separate the individual from the market. The destruction continues to this day.

This is pretty consistent with the model explored by Baron Evola in, for example, Ride the Tiger: A Survival Manual for the Aristocrats of the Soul.[7] Liberalism has atomized[8] society by a Nietzschean smashing of all our idols. All members are now “free” to “realize themselves” and “become what they are.” The problem being, Nietzsche intended this to apply to an elite, the potential Supermen — what Evola calls “differentiated [from the social herd] men” — not society at large. Left to his own devices, the Underman resorts to what he knows best: sensation, and thus to shopping and sex.

Houellebecq’s characters are notable for how completely they embrace the consumerist ethos: believing that youth is society’s primary index of value, that sex is the only pleasure and is eminently commodifiable, that disposability is natural, that quality is ultimately reducible to quantity [cf. Guénon], that the quest for novelty is our only genuine tradition, that secular materialism has triumphed once and for all over atavistic spirituality. [9]

So far, he seems to be on our team. Of course, someone who hates as much as Houellebecq is apt to be an uncomfortable ally.

I know that Islam — by far the most stupid, false and obfuscating of all religions – currently seems to be gaining ground, but it’s a transitory and superficial phenomenon . . . [All but Guénon & Co. shout Yah!]

. . . in the long term, Islam is even more doomed than Christianity. [Crickets][10]

And just to be clear on that: “I was talking about the stupidity of all monotheistic religions.”[11]

Alrighty then, moving along . . . Besides being a fountain of opinions either bold and scintillating or mean and stupid, depending on whose ox is being gored,[12] Houellebecq is a damned good, clear — lucid, the French would say, I suppose — writer; here, if anywhere, worthy of the comparisons made to Camus. [13]

But unlike Camus, he’s a funny guy[14] (though perhaps rather like Joe Pesci is “funny” in Goodfellas[15]):

As a teenager, Michel believed that suffering conferred dignity on a person. Now he had to admit that he had been wrong. What conferred dignity on people was television.

Rumor had it that he was homosexual; in reality, in recent years, he was simply a garden-variety alcoholic

The beach at Meschers was crawling with wankers in shorts and bimbos in thongs. It was reassuring.

Whatever, in the showers at the gym I realized I had a really small dick. I measured it when I got home—it was twelve centimeters, maybe thirteen or fourteen if you measured right to the base. I’d found something new to worry about, something I couldn’t do anything about; it was a basic and permanent handicap. It was around then that I started hating blacks.

Not that Old Grumpypuss will let you just have your fun:

Irony won’t save you from anything; humour doesn’t do anything at all. You can look at life ironically for years, maybe decades; there are people who seem to go through most of their lives seeing the funny side, but in the end, life always breaks your heart. Doesn’t matter how brave you are, or how reserved, or how much you’ve developed a sense of humour, you still end up with your heart broken. That’s when you stop laughing. In the end there’s just the cold, the silence and the loneliness. In the end, there’s only death.

And, as in liberal society, until then, when all else fails, there’s also the sex.[16] Perhaps I’ve consumed more than my share of pornography, but it did not seem as overwhelming or perverse as reviewers would have us believe. I suppose it serves the purpose of shocking the shockable, but if you find it off-putting, or just boring, go ahead and skip it, it really adds nothing to the message of the book.

Now, at this point, fifteen years later, there’s little to be gained in adding yet another review; so with the book taken as read, I’d like to take a look at that message and try to place it in relation to some other, rather grander works.

First off, the book has an odd structure that only becomes apparent with the Epilogue. “Despite the essentially elaborate scope of the plot revealed in the novel’s conclusion (i.e. the eventual emergence of cloning as a replacement for the sexual reproduction of the human race) . . .”[17] It’s not entirely mind-shattering, but if, like Ulysses, you’ve been told it’s just a book about sex, you might wonder what the point is. Even the New Yorker reviewer found himself frustrated by what he called “editorials” cropping up throughout the text, which he felt were Houellebecq putting in his two cents.[18]

Actually, they are another feature of, and clue to, the structure and intent of the book. Certainly other odd features, such as the long poem that opens the book, become clearer at this point. What you have here is another one of those “future histories” that I’ve been reviewing here recently; [19] a biography, from the near future (apparently around 2030) of the main protagonist, the geneticist Michel, and the effects of his work in our near future (actually, now right about today).

In particular, though, it reminded me of a far older, and much more substantial one than those. Then it finally hit me: Hermann Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game [4] .[20]

.[20]

Hesse’s novel takes place around 2500 and presents itself as a biography of a recently deceased and rather controversial Game Master, one Joseph Knecht. To orient the reader (both fictional and real) to both the Game and the history out of which it emerged (which is our own, of course) it opens with a long section presenting “A General Introduction” to the Game’s history “For the Layman.”[21] It ends with a supposed selection of poems from Knecht’s student days documenting his struggle to assimilate the game, and to allow himself to be assimilated by it.

The Game, we learn, arose out of the ruins of The Century of Wars, which was, not coincidentally, the “Age of the Feuilleton,” symbol of journalistic and scholarly frivolity.[22] At the last moment, Europe pulled back from the brink, and initiated a movement dedicated to Truth rather than Interest, to Platonically purify and uplift society by purifying the arts and sciences of fraud, triviality, and irrelevance; above all, by demonstrating their unity and interconnection.

Fortunately, the same Zeitgeist was expressing itself by the slow development of The Game; conveniently indescribable, it seems to be a system, akin to music or mathematics,[23] by which the content of any science can be stated, developed, and, most importantly, interwoven with any other, in a kind of scientific or cultural or spiritual counterpoint. The result is a spiritual exercise, akin to meditation but often performed publicly and ceremonially, “an act of mental synthesis through which the spiritual values of all ages are seen as simultaneously present and vitally alive.” The celibate scholars of the province of Castalia are the secular monks of this new quasi-religious order that orders society as Catholicism did mediaeval Europe.

While there is a certain intellectual thrill in contemplating this picture (perhaps a clue as to whether the reader would be a suitable candidate for the Order) the dramatic heart of the work is the Bildungsroman in the center, in which Joseph Knecht is initiated into the game and the Order, rises to the very highest position, only to abdicate and return to the world when he begins to sense that the Game itself has become arrogant, sterile, and alien to human society, which may someday decide they no longer need to support it; and as Marx would say, the same shit would start all over again.

What does this have to do with The Elementary Particles? Houellebecq has essentially inverted Hesse’s novel, both structurally and thematically.

Structurally, he has placed at the beginning an unattributed poem that strikes the same themes as Hesse’s work, resembling one of Knecht’s final poems of contentment with the Game, “Stages.”

We live today under a new world order

The web which weaves together all things envelops our bodies

Bathes our limbs,

In a halo of joy.

A state to which men of old sometimes acceded through music

Greets us each morning as a commonplace.

What men considered a dream, perfect but remote,

We take for granted as the simplest of things.

But we are not contemptuous of these men,

We know how much we owe to their dreaming,

We know that without the web of suffering and joy which was their history, we would be nothing.

Now, rather than Hesse’s long, clear, conveniently labeled Introduction to the Game and our history we have the unexpected and puzzling epilogue, which details Michel’s self-exile to Ireland (land of monks where “most of them around here are Catholics”) and his breakthrough in genetics that results in the replacement of sexual reproduction with perfect, immortal clones. The bulk of the novel shows us the modern, secular society that Michel comes to doubt and reject.

Genetics, of course, easily lends itself to metaphors of weaving, but Michel’s breakthrough, which somehow bases itself on quantum mechanics, seems especially Game-like: “Any genetic code, however complex, could be noted in a standard, structurally stable form, isolated form disturbances and mutation . . . every animal species could be transformed into a similar species . . .”

Moreover, the description of his thought processes and inspirations constantly recur to similar tropes; he takes inspiration from the Book of Kells and writes works like “Meditations on Interveaving” — “Separation is another word for evil; it is also another word for deceit. All that exists is a magnificent interweaving, vast and reciprocal.” — while a his protégé’s article “Michel Djerzinki and the Copenhagen Interpretation” is in fact a “long meditation on a quotation from Parmenides” while another attempts “a curious synthesis of the Vienna Circle and the religious positivism of Comte.”

Meanwhile, the popularizing of Michel’s ideas adds to the popular ferment. We live in “the age of materialism (defined as the centuries between the decline of medieval Christianity and the publication of Djerzinki’s work)” whose “confused and arbitrary” ideas have led to a 20th century “characterized by progressive decline and disintegration.” But now, “There had been an acceptance of the idea that a fundamental shift was indispensable if society was to survive – a shift which would credibly restore a sense of community, of permanence and of the sacred.”

The key to this is “the global ridicule in which the works of Foucault, Lacan, Derrida and Deleuze had suddenly foundered, after decades of inane reverence,” which “heaped contempt on all those intellectuals active in the ‘human sciences.’” Now “they believed only in science; science was to them the arbiter of unique, irrefutable truth.”

What we have, then, is in effect a re-write of Hesse’s novel, but now centered on the (in Hesse’s work, anonymous by choice[24]) inventor of the Game, rather than his later descendant; the celibate monks of Castalia, selected in childhood and separated forever from their mundane families, have now been generalized to the entire population of the Earth: “Having broken the filial chain that linked us to humanity, we live on. We have succeeded in overcoming the forces of egotism, cruelty and anger which they [us!] could not.”[25]

While it’s pretty cool and all, one can’t help but think, especially if one has already read Hesse’s novel, that Houellebecq has simply passed the buck. Remember that whole middle section about Joseph Knecht? Hesse had played around with the idea of a utopian society devoted to intellectual contemplation for years; who hasn’t, from Leibniz all the way back to Plato? And he, like Plato, had seen, living through the Century of Wars himself, that it was the only hope for mankind, or at least for culture.

The problem was, however, less one of how to do it — Step One, invent cloning — than Step Two, how would it work; or rather, how would it be maintained? Houellebecq’s narrator speaks with the same placid self-satisfaction as the narrator of Hesse’s introduction: “Science and art are still a part of our society; but without the stimulus of personal vanity, the pursuit of Truth and Beauty has taken on a less urgent aspect.” Indeed. What Joseph Knecht realizes is that dealing with the “less urgent aspect” (his scholars can, if they choose, while away whole careers freely pursuing research so inane that even our Federally-funded researchers would be embarrassed) may be the key to avoiding sterility (admitted, not a problem perhaps with cloning) and self-defeating social irrelevance.

Simultaneously and synchronistically, while Hesse was writing away in Switzerland Thomas Mann was comfortably ensconced in LA, writing his own very similar book, Doctor Faustus : The Life of the German Composer Adrian Leverkuhn As Told by a Friend [5] .[26] Given its resemblances to Hesse’s novel, it’s not surprising to find similarities to Houellebecq’s. Mann’s narrator is contemporary with us, not a few decades in advance, but also writing about our own (then) recent times — Germany from Bismarck to Hitler. His subject, Adrian Leverkuhn is, like Houellebecq’s Bruno, an artist, though also, like Michel, a whiz at mathematics, at least of the cabalistic kind (thus relating him to Hesse’s Castalians). Like Bruno, he is sexually twisted, though in a Wilhemine German way — like Nietzsche, he has sexual contact once, with a prostitute, in order to deliberately infect himself, like Nietzsche, with syphilis. Like both Bruno and Michel, his one, last object of love, his nephew, is torn away from him through an agonizing, grotesque death.

.[26] Given its resemblances to Hesse’s novel, it’s not surprising to find similarities to Houellebecq’s. Mann’s narrator is contemporary with us, not a few decades in advance, but also writing about our own (then) recent times — Germany from Bismarck to Hitler. His subject, Adrian Leverkuhn is, like Houellebecq’s Bruno, an artist, though also, like Michel, a whiz at mathematics, at least of the cabalistic kind (thus relating him to Hesse’s Castalians). Like Bruno, he is sexually twisted, though in a Wilhemine German way — like Nietzsche, he has sexual contact once, with a prostitute, in order to deliberately infect himself, like Nietzsche, with syphilis. Like both Bruno and Michel, his one, last object of love, his nephew, is torn away from him through an agonizing, grotesque death.

But most significantly, after that last catastrophe, he conceived his ultimate work, before sinking, again like Nietzsche and Bruno, into madness — The Lamentations of Dr. Faustus, an blasphemous atonal work by which he intends “to take back the Ninth.” I think Houellebecq’s novel can be seen as performing a similar function — taking back The Glass Bead Game, or at least its dramatic sections, where the personal and historical conflicts are lived through and at least somewhat resolved; instead settling comfortably in with the rather pompous narrator of the Introduction, refusing to face the task of working out the problems of the interactions of the human particles and simply saying, “Oh, sure, the modern world sure sucks so let’s just let Science clone us and be done with it!”

Notes

[1] “One Night In Bangkok,” from Chess [6] by Tim Rice and Benny Andersson

[3] Now republished in the collection The Eldritch Evola … & Others (Counter Currents, 2014).

[4] Although not, like Thomas Ligotti, the same city of birth, college and first job.

[5] His narrator from the future laconically notes that “Foucault, Lacan, Derrida, and Deleuze” have fallen into “global ridicule” and “suddenly foundered, after decades of inane reverence.”

[6] “Confused extremes: Platform, Michel Houellebecq’s follow-up to Atomised [aka The Elementary Particles]” by Anna Lynskey, here [8].

[7] 1961; first English translation (by Joscelyn Godwin and Constance Fontana) published by Inner Traditions in 2003. See especially “Part Two: In the World Where God is Dead.”

[8] The title of the UK edition of the book.

[9] “Death Dreams” by Rob Horning, here [9].

[10] Of course, some on the Right would be fine with that: “Ben Jeffery makes a comment on this, saying: ‘It is not that Houellebecq is a reactionary writer exactly. For example, it is never suggested that religious faith is the solution to his character’s dilemmas; the books are all resolutely atheist.’ But I guess Jeffery has never heard of the likes of Mencius Moldbug [10], neoreactionary atheist….” “Ben Jeffery’s Anti-Matter: Michel Houellebeq and Depressive Realism” by Craig Hickman; May 19, 2013, here [11].

[11] Suzie Mackenzie, Interview with Michel Houellebecq, The Guardian. August 31, 2002.

[12] “I don’t begin by wanting to be provocative exactly, no. But when I realize that what I say is provoking, I don’t change it because of obstinacy. It’s up to me. Nobody asked me to say it again.” — The Guardian. August 31, 2002.

[14] “Yet Houellebecq possesses one quality in which the Left Bank existentialists of the ’40s and ’50s were notably lacking, namely, humor. Houellebecq’s fiction is horribly funny. Often the joke is achieved by a po-faced conjunction of the grandiloquent and the thumpingly mundane.” – “Futile Attraction: Michel Houellebecq’s Lovecraft” by John Banville, Bookforum (April/May 2005), here [13].

[15] Henry: You’re just funny, y’know, the story. It’s funny. You’re a funny guy.

Tommy: Whattya mean? The way I talk? What?

Henry: It’s just, y’know, it’s just funny, you know the way you tell the story and everything . . .

Tommy: Funny how? I mean, what’s funny about it?

Anthony (Frank Adonis): (worried) Tommy, no, you got it all wrong . . .

Tommy: Whoa, whoa Anthony! He’s a big boy, he knows what he said. What’d you say? Funny how? What?

Henry: Just you know you’re funny.

Tommy: You mean, let me understand this . . . cuz I . . . maybe it’s me, maybe I’m a little fucked up maybe. I’m funny how, I mean funny, like I’m a clown? I amuse you. I make you laugh? I’m here to fuckin’ amuse you? Whattya you mean funny? Funny how? How am I funny?

Henry: I don’t know just . . . you know how you tell the story. What?

Tommy: No, no I don’t know. You said it. How do I know? You said I’m funny. (yelling now) How the fuck am I funny? What the fuck is so funny about me? Tell me. Tell me what’s funny?

[16] “Now the wife and I are going to have the sex.” — MST3k, Experiment #0612 — The Starfighters.

[17] Wikipedia, here [14].

[18] “Paris Journal: Noel Contendere: A political impasse gives way to a literary scandal” by Adam Gopnick; Dec. 28, 1998 & Jan. 4, 1999, p61.

[20] Das Glasperlenspiel, 1943; English as Magister Ludi (1949) and The Glass Bead Game (1969).

[21] If you have a kindle, you can download the whole Introduction as a “sample” from Amazon.

[22] Imagine American Idol, although Hesse couldn’t think of anything more degrading than crossword puzzles and popularizing literary biographies.

[23] Music, of course, properly understood, is mathematics. For this, and the Traditional doctrine by which musical systems are methods of creation rather than arbitrary systems of pleasant noise, see the material presented in my essay “Our Wagner, Only Better: Harry Partch, The Wild Boy of American Music” in The Eldritch Evola . . . & Others.

[24] See Guénon’s The Reign of Quantity, Chapter 9, “The Twofold Significance of Anonymity.”

[25] “Our people have forgotten, they have been made to forget. For centuries. But I have learned how it once was. Families. Brothers and sisters. There was happiness . . . there was love.” — Teenagers from Outer Space (1959).

[26] Theodore Ziolkowski explores the remarkable parallels in his “Foreword” to the 1969 translation.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Penser en Europe est devenu dangereux. Le renouveau de l’inquisition a perdu de réputation l’histoire, désormais lieu de la vérité révélée et donc légale. L’époque qui s’étend du XVIIIème siècle à 1880 - à peu près - connaît ses idéologues bornés malgré que le thème général soit l’étude de l’industrialisation. Si la tyrannie a cessé, laquelle obligeait à penser le développement selon les lois de la science prolétarienne appuyée sur le Goulag, la science occidentale l’a remplacée avantageusement en imposant les analyses du FMI, de la Banque mondiale, de l’OMC. Mais Patrick Verley mène son enquête avec des méthodes éprouvées et nous convainc d’une absence de lois générales et a-temporelles pour expliquer le processus d’industrialisation.

Penser en Europe est devenu dangereux. Le renouveau de l’inquisition a perdu de réputation l’histoire, désormais lieu de la vérité révélée et donc légale. L’époque qui s’étend du XVIIIème siècle à 1880 - à peu près - connaît ses idéologues bornés malgré que le thème général soit l’étude de l’industrialisation. Si la tyrannie a cessé, laquelle obligeait à penser le développement selon les lois de la science prolétarienne appuyée sur le Goulag, la science occidentale l’a remplacée avantageusement en imposant les analyses du FMI, de la Banque mondiale, de l’OMC. Mais Patrick Verley mène son enquête avec des méthodes éprouvées et nous convainc d’une absence de lois générales et a-temporelles pour expliquer le processus d’industrialisation.

Serge Latouche et Cornélius Castoriadis ont beaucoup en commun. C’est pourquoi l’ouvrage du premier sur le second, décédé en 1997, est beaucoup plus qu’un ouvrage de présentation. C’est avant tout un corps à corps avec la pensée de Castoriadis. L’autonomie est le maitre mot de Castoriadis. L’autonomie du citoyen, et l’organisation de l’autonomie des collectifs de producteurs-travailleurs, cela amène logiquement à refuser la domination d’une technique monoforme au service du Capital comme rapport social et organisation productiviste de l’économie. La technique doit être plurielle, et non pas orientée en fonction des exigences de l’accumulation du Capital. L’autonomie mène ainsi directement à l’écosocialisme, ou encore, comme le dit Serge Latouche et comme le souhaitait André Gorz, à la décroissance.

Serge Latouche et Cornélius Castoriadis ont beaucoup en commun. C’est pourquoi l’ouvrage du premier sur le second, décédé en 1997, est beaucoup plus qu’un ouvrage de présentation. C’est avant tout un corps à corps avec la pensée de Castoriadis. L’autonomie est le maitre mot de Castoriadis. L’autonomie du citoyen, et l’organisation de l’autonomie des collectifs de producteurs-travailleurs, cela amène logiquement à refuser la domination d’une technique monoforme au service du Capital comme rapport social et organisation productiviste de l’économie. La technique doit être plurielle, et non pas orientée en fonction des exigences de l’accumulation du Capital. L’autonomie mène ainsi directement à l’écosocialisme, ou encore, comme le dit Serge Latouche et comme le souhaitait André Gorz, à la décroissance.

Les dirigeants du Japon ont embrassé et imité les règles régissant les relations internationales occidentales, ont réagi par la force à la politique de la canonnière et bâti un empire colonial asiatique : pour les thuriféraires du Grand Japon et quelques intellectuels ( le plus connu est

Les dirigeants du Japon ont embrassé et imité les règles régissant les relations internationales occidentales, ont réagi par la force à la politique de la canonnière et bâti un empire colonial asiatique : pour les thuriféraires du Grand Japon et quelques intellectuels ( le plus connu est