jeudi, 17 octobre 2013

Die Geburt der Moderne

Die Geburt der Moderne

von Benjamin Jahn Zschocke

Ex: http://www.blauenarzisse.de

Der Nationalsozialismus ist der absolute Fixpunkt der deutschen Geschichte – wirklich alles ballt sich zu ihm hin. Alle zeitlich daran angrenzenden Epochen verschwinden in seinem Schatten.

Der Nationalsozialismus ist der absolute Fixpunkt der deutschen Geschichte – wirklich alles ballt sich zu ihm hin. Alle zeitlich daran angrenzenden Epochen verschwinden in seinem Schatten.

Der in Chemnitz lehrende Professor für Europäische Geschichte des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts Frank-Lothar Kroll ist dafür bekannt, eine mittelbar an diese Zeit angrenzende Epoche, nämlich das Deutsche Kaiserreich von 1871 bis 1918, dankenswerter Weise aus diesem Schatten hervorzuholen. Unter Zuhilfenahme aller verfügbaren historischen Quellen betrachtet er diese Epoche so, wie sie war und nicht, wie sie laut der verengten Sichtweise eines „deutschen Sonderweges“ – bei einem gleichzeitig angenommenen „westeuropäischen Normalweg“ – gewesen sein soll.

Ein umfassendes Update der Quellenlage

Krolls aktuellstes Werk Geburt der Moderne. Politik, Gesellschaft und Kultur vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg unternimmt auf reichlich 200 Seiten den Versuch, einen Gesamtüberblick über die gesellschaftlichen Entwicklungslinien zwischen 1900 und 1914 zu geben. Da dies in solcher Kürze fast unmöglich scheint, verzichtet Kroll auf alle narrativen Elemente und gibt dem Leser in höchster Komprimierung sozusagen ein Update der aktuellen Quellenlage, in deren Ergebnis die Annahme des besagten „deutschen Sonderweges“ ebenso definitiv zu den Akten gelegt werden muß, wie das „persönliche Regiment“ unseres letzten Kaisers Wilhelm II.

Die seit gut fünfzig Jahren praktizierte „germanozentrische“ Herangehensweise gelangt bei Kroll ebenfalls auf die Deponie. Vielmehr gehört der historische Blickwinkel nach seinem Verständnis auf eine europäische Dimension geweitet, was allein angesichts der verästelten außenpolitischen Bündnisse dieser Epoche gar nicht anders möglich ist.

Doch Krolls Schwerpunkt liegt in diesem Buch definitiv nicht auf dem Ersten Weltkrieg: ungleich mehr interessiert ihn der kulturelle und soziale Entwicklungsstand eines Landes, das zur damaligen Zeit das fortschrittlichste der Welt war. Krolls große Stärke ist es, nicht nach Belieben zu werten, sondern nüchtern Fakten um Fakten vorzutragen und damit großkalibrig gegen die an deutschen Gymnasien, Universitäten und in den Medien herrschende Guido Knopp-Mentalität vorzugehen.

Kultureller Vorreiter des Kontinents

Besonders der kulturelle Schwerpunkt reizt an Krolls Buch. Die titelgebende These, nach der die Moderne bereits zwischen 1900 – 1914 unter Wilhelm II. ihren Anfang nahm sowie erste Schwerpunkte herauskristallisierte – und damit nicht erst in den gepriesenen (dekadenten und auf Kredit finanzierten) so genannten Goldenen Zwanzigern – macht die Lektüre besonders empfehlenswert. Walther Rathenau schrieb schon 1919 in seinem Text Der Kaiser: „Für Kunst lag [beim Kaiser, Anm. BJZ] eine entschiedene formale Begabung zugrunde, die in rätselhafter Weise über die kunstfremde Umgebung emporhob […]. So ergab sich von selbst der Anspruch des künstlerischen Oberkommandos.“

Unter anderem am Beispiel der Kulturreform aber auch der Jugendbewegung arbeitet Kroll heraus, welche in Europa zur damaligen Zeit einmalige Fülle an verschiedenartigsten Kulturinstitutionen entstand und sich in aller Ruhe, teils sogar mit erheblichen Finanzspritzen, entwickeln konnte. Am bekanntesten sind auf dem Gebiet der Kunst wohl die Strömungen des Jugendstils, des Expressionismus und des Impressionismus, die zwischen 1900 – 1914 ihren Anfang nahmen. Besonders mit Blick auf Letzteren lohnt ebenso die Lektüre des bereits 1989 bei Königshausen & Neumann erschienenen Werkes von Josef Kern Impressionismus im Wilhelminischen Deutschland.

Weimars Probleme im Voraus erkannt – und behoben

Der oben mit „Guido Knopp-Mentalität“ zusammengefaßten Erscheinung heutiger Geschichtsschreibung (eigentlich politischer Bildung), tritt Kroll mit aller Entschiedenheit entgegen: Erhellend sind zum Beispiel seine Erkenntnisse auf dem Gebiet der Presse– und Parteienlandschaft. Er spricht hier von einem „beispiellosen Pluralismus“. Außerdem wird die vielzitierte, himmelschreiende Armut der späten Phase der Industrialisierung (auf die im gymnasialen Geschichtsunterricht „zufällig“ eine monatewährende Behandlung der deutschen Arbeiterbewegung folgt) als Ammenmärchen enttarnt: „Wirkliche Massenarmut, die zur Verelendung trieb, gab es im wilhelminischen Deutschland – anders als im viktorianischen und edwardianischen England – nicht, wenngleich, die Mehrheit der Arbeiterschaft von sehr bescheidenen Einkommen zehrte.“

Am schwerwiegendsten sind, mit Blick auf den anfangs benannten Schatten einer gewissen Epoche wohl Krolls Feststellungen zum angeblich durch und durch judenfeindlichen Deutschland unter Wilhelm II.: „Die unmissverständliche Zurückweisung solcher Zumutungen seitens des Kaisers und der Reichsregierung verdeutlichte einmal mehr, dass im ‚ausgleichenden Klima des wilhelminischen Obrigkeitsstaates‘ dem politischen Einfluss radikalisierter Massen und Massenbewegungen, anders als in den späten Jahren der Weimarer Republik, enge Grenzen gesetzt waren.“

An anderer Stelle wird Kroll noch deutlicher: „Dass sich die Mobilisierung antisemitischer Ressentiments in Deutschland – und nicht etwa in Frankreich, wo sie vor und nach der Jahrhundertwende weitaus stärker verbreitet waren – Jahrzehnte später zu einer parteipolitischen Massenformation verdichten und schließlich in die Katastrophe des ‚Dritten Reiches‘ einmünden sollte, lag, bei aller partiell vorhandenen gesellschaftlichen Diskriminierung der rechtlich gleichgestellten Juden im Kaiserreich, nicht an strukturellen Defiziten oder Defekten des vermeintlichen wilhelminischen Obrigkeitsstaates. Eigentliche Ursache waren vielmehr die fatalen Konsequenzen der militärischen und politischen Niederlage Deutschlands im Ersten Weltkrieg.“

Hörenswerte Audio-Rezension bei Deutschlandradio Kultur.

Frank-Lothar Kroll: Geburt der Moderne. Politik, Gesellschaft und Kultur vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg. Band 1 der Reihe Deutsche Geschichte im 20. Jahrhundert. 224 Seiten, Be.Bra Verlag 2013. 19,90 Euro.

Josef Kern: Impressionismus im Wilhelminischen Deutschland. Studien zur Kunst– und Kulturgeschichte des Kaiserreichs. 476 Seiten, Königshausen & Neumann Verlag 1989. 50,00 Euro.

00:05 Publié dans art, Livre, Livre, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : modernisme, modernité, allemagne, livre, histoire, art |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 08 octobre 2013

R. Marchand: Reconquista

00:05 Publié dans Evénement, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : rené marchand, lyon, événement, france, livre, dédicace |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

L’Ecologie n’est pas la démagogie !

Pierre Le Vigan

Ex: http://metamag.fr

Les auteurs couplent cette idée avec celle d’un Revenu maximum acceptable (RMA), en d’autres termes d’un revenu maximum. Comme d’autres écologistes radicaux, ils fixent l’écart entre le revenu minimum universel (donc sans travailler) et le revenu maximum à 4. Les auteurs essaient aussi d’articuler leur projet de revenu inconditionnel d’autonomie avec une réduction du temps de travail qui permettrait un partage du travail. Ils ne sont là-dessus guère convaincants. On leur objectera volontiers qu’ils posent mal le problème qu’ils essaient de résoudre par leur « revenu universel ». D’une part le travail ne saurait être rejeté, il est le propre de l’homme. Un revenu sans travail est donc inacceptable. En défendant un tel revenu, ils se privent de tout moyen d’effectuer une critique solide de la finance.

Par contre, le travail peut revêtir de multiples formes, il peut avoir un intérêt social sans être un travail salarié. Il faut donc reconsidérer ce qui est travail mais non proposer une anti-civilisation refusant le travail. On ne pinaillera pas outre mesure sur les écarts de revenus proposés. Mais tout de même… Un écart de 1 à 4 entre deux travailleurs est pour le moins modeste. Mais pourquoi pas ? Un travail 4 fois mieux payé que le salaire minimum est aussi souvent beaucoup plus intéressant. Mais ce n’est pas ce que proposent nos auteurs. Pour eux, c’est encore trop inégalitaire ! Ce qu’ils veulent c’est un écart entre le revenu inconditionnel donc sans travail et le salaire maximum de 1 à 4, cela veut dire un écart de 1 à 4 entre quelqu’un au RSA actuellement et le salarié le mieux payé : quelque 492 € pour le moins bien payé ne travaillant pas, moins de 2000 € pour le mieux payé. Imagine-t-on que quelqu’un prendra des risques, travaillera 70 heures et plus par semaine pour ne gagner que 4 fois le revenu minimum attribué inconditionnellement à quelqu’un qui ne travaille pas et à qui on ne demande pas de le faire ? Ce n’est pas sérieux.

Les auteurs de ce livre réduisent ainsi l’écologie à de la démagogie et n’emportent pas la conviction. Dommage car ils ont parfois des lueurs de lucidité. Ainsi quand ils indiquent que les « premières victimes de l’ [cette] immigration massive sont les immigrants eux-mêmes, condamnés pour des raisons économiques, aveuglés par les lumières du consumérisme, à quitter leur culture et leurs proches et à prendre de gros risques pour finalement être exploités par le système capitaliste dans un autre pays ». Les immigrés ont donc une culture ? Différente de la nôtre alors ? Ils ne sont donc pas solubles si facilement dans l’Occident ? L’immigration serait « massive » alors que les journaux « sérieux » nous expliquent que le nombre d’immigrés n’augmente pas ou si peu ? Il ne manquerait plus que nos auteurs finissent par nous expliquer que l’immigration n’est pas une chance pour l’écologie. Il resterait à reconnaitre que les indigènes aussi en sont victimes car l’immigration comme armée de réserve du capital est une arme de la lutte des classes que mène l’hyperclasse contre les peuples.

Vincent Liegey, Stéphane Madelaine, Christophe Ondet, Anne-Isabelle Veillot, Un projet de décroissance. Manifeste pour une dotation inconditionnelle d’autonomie, préface de Paul Ariès, éd. Utopia.

00:05 Publié dans Ecologie, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : écologie, livre, démagogie, politique, décroissance |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 06 octobre 2013

G. Adinolfi: Orchestre rouge

Gabriele Adinolfi vient de publier en France son tout dernier livre, Orchestre Rouge, adressé tout particulièrement au public français (il n’existe pas encore de version italienne).

Dans ce livre-enquête, il nous revèle les secrets de l’internationale terroriste. Secrets de Polichinelle, pour utiliser une expression chère à la commedia dell’arte! Les enquêteurs sont en effet en possession de preuves irréfutables disculpant totalement les nationalistes. Ils les ont toujours ignorées par décision politique.Cet ouvrage, conçu comme un complément de Nos belles années de plomb (toujours en librairie), reconstitue pas à pas les actes terroristes perpétués en Italie, mais qui concernent aussi la France, longtemps carrefour international de la terreur.Adinolfi révéle (avec l’aide d’avocats et de juges qui ont tenu à conserver l’anonymat), les preuves qui clouent la centrale de la terreur italienne qui n’était rien d’autre que la filière du commandemant partisan des annés quarante. Qui oserait dire que la «pieuvre» de la terreur était consitituée essentiellement de l’internationale trotzkiste et socialiste? Que leurs agissements étaient non seulement autorisés, mais surtout couverts par la Commisson Trilatèrale? Qu’ils ont déclenché une véritable guerre méditerranéenne, remportée par Israël avec l’imposition de la doctrine Kissinger?A la fin de l’ouvrage, un témoignage historique nous éclaire sur les motivations et le jeu machiavélique des guérilleros rouges. Une clef indispensable pour comprendre la mentalité révolutionnaire.L’auteur nous démontre point par point comment la théorie (officielle) de la «stratégie de la tension» voulue par le parti atlantiste pour contrer l’avancé communiste et le pacte de Varsovie est totalement fausse.

Orchestre Rouge Avatar Editions, 19 €.

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, gabriele adinolfi, orchestre rouge, terrorisme, années de plomb, italie, nationalisme révolutionnaire |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 03 octobre 2013

UN REGARD SUR LES TRENTE GLORIEUSES

Pierre LE VIGAN

Ex: http://metamag.fr

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, france, trente glorieuses, livre |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 29 septembre 2013

Montherlant und der nutzlose Dienst

Montherlant und der nutzlose Dienst

von Jens Strieder

Ex: http://www.blauenarzisse.de

Die wichtigsten Auszüge aus Henry de Montherlants 1939 erstveröffentlichter Essaysammlung wurden im Verlag Antaios wieder aufgelegt.

Vielen deutschen Lesern ist der Name Henry Marie Joseph Frédéric Expedite Millon de Montherlant nicht mehr geläufig. Das gilt auch für sein Heimatland Frankreich. Es ist umso verwunderlicher, wenn man bedenkt, dass es sich bei dem 1895 in Paris geborenen Literaten um ein Ausnahmetalent handelte, das in nahezu allen Textformen zu Hause war: Montherlant schrieb Romane, Erzählungen, Novellen, Theaterstücke, Essays und Tagebücher. Sein Gedankenreichtum, seine Beobachtungsgabe und die durch ihre Schönheit bestechende Ausdruckskraft, sprechen für sich und machen ihn zu einem der bedeutendsten Schriftsteller des 20. Jahrhunderts.

Das Nutzlose liegt nicht im Trend

1939 erschien in Leipzig sein Essay-Band mit dem Titel „Nutzloses Dienen”. Damit diese Texte nicht vollends in Vergessenheit geraten, ist im Verlag Antaios ein Band erschienen, der in Form von fünf Essays eine Auswahl der im Original vertretenen Schriften aus den Jahren 1928 – 1934 versammelt.

Die Namensgebung des Bandes verweist sogleich auf eine literarische, aber auch lebenspraktisch orientierte Selbstkonzeption Montherlants: Eine persönliche Haltung, die einem scheinbar sinnlosen oder gar unsinnigen Handeln einen eigentümlichen Wert jenseits jeglichen oberflächlichen Utilitarismus’ beimisst.

Das Nutzlose liegt nicht im Trend, erschließt sich nicht jedem und ist vornehmlich Selbstzweck, dessen idealistischer Wert in der Herauslösung aus dem Alltäglichen, Banalen und Kollektiven liegt. Dabei dient es Montherlant auch zur Überwindung des Nihilismus: „Was mich aufrecht hält auf den Meeren des Nichts, das ist allein das Bild, das ich mir von mir selber mache”.

Der überzeitliche Wert des eigenen Handelns

Allein dieser Satz macht deutlich, dass sich die Dienerschaft auf den Dienenden selbst bezieht. Eine derartige Selbstkonzeption sollte nicht als Ausdruck von Arroganz oder Narzissmus missverstanden werden. Vielmehr geht es Montherlant darum, dem eigenen Wirken einen ideellen und überzeitlichen Wert jenseits des Egos beizugeben.

Ein solches Verständnis vom irdischen Dasein schlägt sich dann auch in allen fünf hier enthaltenen Texten nieder. Entscheidend scheint hierbei vor allem der Umstand zu sein, dass sich Montherlants Ethik eines nutzlosen Dienstes bei aller inneren Höhe, durch eine spezielle Form von Askese auszeichnet, die nicht nur auf Anerkennung von außen verzichtet, sondern auch nicht nach sichtbaren Bezeugungen giert.

So ist für Montherlant beispielsweise die Architektur ein Spiegel dieser Ethik. Wo das Versailler Schloß in erster Linie durch äußeren Glanz und Prunk wirkt, jedoch nach Meinung von Montherlant nicht darüber hinausschaut, sind beispielsweise die spanischen Paläste durch die Verbindung von Schnörkel und schlichtester Einfachheit ein Zeichen von Strenge, welche zum unabdingbaren Wesensmerkmal echter Größe gehört.

Montherlants Selbstkonzeption als Habitus

Für Montherlant sind deshalb die einzig wertvollen Kronen diejenigen, die man sich selbst gibt, denn „[…] die gute Tat geht nicht verloren, wie vergebens sie auch gewesen ist […].” Entsprechend wird auch die „sittliche Idee” der Ehre verteidigt, die auch dann zu wahren ist, wenn sie anderen als unangemessen oder gar lächerlich erscheinen mag.

Das „Heldentum des Alltags” ist nicht weniger bedeutsam als beispielsweise jenes im Krieg und anderen Ausnahmesituationen. Vielmehr ist es Bestandteil der Würde des Menschen. Montherlant setzt nicht einfach andere Prioritäten als jene, die ihm hier nicht folgen können, sondern er wird auch zum Schöpfer seiner selbst, indem er die Rolle konzipiert, die er als endliches Wesen im Fortgang der Zeit spielen möchte – nicht als Schauspieler, sondern als Resultat eines inneren Bedürfnisses.

Somit ist es nur logisch, sich nicht mit dem von niederen Instinkten geleiteten, hässlichen gemein machen zu wollen. Der nutzlose Dienst ist so auch immer ein Akt der bewussten Sezession.

Die Unabhängigkeit des Schriftstellers

Zugleich grenzt Montherlant in einem ebenfalls abgedruckten Vortrag, den der er am 15. November 1933 vor Offizieren der Kriegsakademie hielt, jenes Handeln aus Pflichtgefühl, Notwendigkeit oder edlen Motiven gegen ein Ehrverständnis ab, das der Unbesonnenheit anheim fällt und aus Dummheit und Leichtsinn Risiken eingeht und andere Leben gefährdet.

In Der Schriftsteller und das öffentliche Wirken fordert Montherlant die Freiheit der Unbhängigkeit des Schriftstellers von gesellschaftlich relevanten Themen ein. Er wendet sich gegen das Schubladendenken und die Erwartungshaltung des Kulturbetriebs, die letztlich den wesentlichen Teil des dichterischen Ausdrucks unterdrücken. Vor dem Hintergrund der heute üblichen, feuilletonistischen Simplifizierungen und Rollenzuschreibungen kann man mit Gewissheit sagen, dass dieses Anliegen berechtigt war.

Existentielle Bedrohung von innen oder außen

In einer Lage existentieller Bedrohung von innen oder außen dagegen sieht Montherlant den Schriftsteller dennoch in der Pflicht, seinen Beitrag zu leisten. Das verdeutlicht, dass die konstatierte Eigenart keine Ausrede für Verantwortungslosigkeit oder Feigheit sein kann. Ein geistig-moralischer Führungsanspruch im Sinne einer „engagierten Literatur” lässt sich hieraus jedoch keineswegs ableiten und wird vom Autor auch verworfen.

Für alle, die sich für diesen großen Geist interessieren, stellt der Band trotz seiner Knappheit den idealen Einstieg für eine tiefergehende Beschäftigung mit dessen Werk und Wirkung dar.

Henry de Montherlant: Nutzloses Dienen. 88 Seiten, Verlag Antaios 2011. 8,50 Euro.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, lettres, littérature, lettres françaises, littérature française, france, montherlant |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 25 septembre 2013

Pour une critique positive

La première publication de Pour une critique positive est datée de 1962. Rédigé en détention (les prisons de la République hébergeaient alors de nombreux patriotes coupables d’avoir participé à la défense des Français d’Algérie), ce texte est un exercice d’autocritique sans comparaison « à droite ».

S’efforçant de tirer les enseignements des échecs de son action, l’auteur propose une véritable théorie de l’action révolutionnaire. Pour une critique positive a été une influence stratégique majeure pour de très nombreux militants, des activistes estudiantins des années 70 aux identitaires.

Pour une critique positive a été publié sous anonymat, comme c’est souvent le cas pour ce type de textes d’orientation, mais il est aujourd’hui communément admis que Dominique Venner en fut l’auteur. C’était avant qu’il quitte le terrain de l’action politique pour se consacrer à l’histoire.

Nous avons souhaité conserver l’œuvre originale dans son intégralité, les références ou le vocabulaire employés dans le texte pourront parfois surprendre ou choquer. S’il arrive que les mots soient durs, c’est que l’époque et les épreuves traversées l’étaient.

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : dominique venner, nouvelle droite, critique positive, livre |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 23 septembre 2013

La teoria etnonazionalista

La teoria etnonazionalista

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Terroirs et racines, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ethno-nationalisme, ethnies, livre, théorie politique, sciences politiques, politologie, ethnisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 22 septembre 2013

Technopol und Maschinen-Ideologien

Robert Steuckers:

Technopol und Maschinen-Ideologien

Analyse: Neil POSTMAN, Das Technopol. Die Macht der Technologien und die Entmündigung der Gesellschaft, S. Fischer Verlag, 1991, 221 S., ISBN 3-10-062413-0.

Neil Postman, zeitgenößischer amerikanischer Denker und Soziolog, ist hauptsächlich für seine Bücher über die Fernsehen-Gefahren bei Kindern bekannt. In seinem Buch Das Technopol klagt er den Technizismus an, wobei er nicht die Technik als solche ablehnt, sondern die Mißbräuche davon. In seiner Einleitung, spricht Postman eine deutliche Sprache: Die Technik ist zwar dem Menschen freundlich, sie erleichtert ihm das Leben, aber hat auch dunkle Seiten. Postman: «Ihre Geschenke sind mit hohen Kosten verbunden. Um es dramatisch zu formulieren: man kann gegen die Technik den Vorwurf erheben, daß ihr unkontrolliertes Wachstum die Lebensquellen der Menschheit zerstört. Sie schafft eine Kultur ohne moralische Grundlage. Sie untergräbt bestimmte geistige Prozesse und gesellschaftliche Beziehungen, die das menschliche Leben lebenswert machen» (S. 10). Weiter legt Postman aus, was die Maschinen-Ideologien eigentlich sind und welche Gefahren sie auch in sich tragen. Postman macht uns darauf aufmerksam, das gewisse Technologien unsichtbar sein können: so Postman: «Management, ähnlich der Statistik, des IQ-Messung, der Notengebung oder der Meinungsforschung, funktionniert genau wie eine Technologie. Gewiß, es besteht nicht aus mechanischen Teilen. Es besteht aus Prozeduren und Regeln, die Verhalten standardisieren sollen. Aber wir können ein solches Prozeduren- und Regelsystem als eine Verfahrensweise oder eine Technik bezeichnen; und von einer solchen Technik haben wir nichts zu befürchten, es sei denn, sie macht sich, wie so viele unserer Maschinen, selbstständig. Und das ist der springende Punkt. Unter dem Technopol neigen wir zu der Annahme, daß wir unsere Ziele nur erreichen können, wenn wir den Verfahrensweisen (und den Apparaten) Autonomie geben.

Diese Vorstellung ist um so gefährlicher, als sie niemand mit vernünftigen Gründen gegen den rationalen Einsatz von Verfahren und Techniken stellen kann, mit denen sich bestimmte Vorhaben verwirklichen lassen. (...) Die Kontroverse betrifft den Triumph des Verfahrens, seine Erhöhung zu etwas Heiligem, wodurch verhindert wird, daß auch andere Verfahrensweisen eine Chance bekommen» (S. 153-154). Weiter warnt uns Postman von einer unheimlichen Gefahr, d. h. die Gefahr der Entleerung der Symbole. Wenn traditionnelle oder religiöse Symbole beliebig manipuliert oder verhöhnt werden, als ob sie mechanische Teilchen wären, entleeren sie sich. Hauptschuldige daran ist die Werbung, die einen ständig größeren Einfluß über unseres tägliche Denken ausübt und die die Jugend schlimm verblödet, so daß sie alles im Schnelltempo eines Werbungsspot verstehen will. Um Waren zu verkaufen, manipulieren die Werbeleute gut bekannte politische, staatliche oder religiöse Symbole. Diese werden dann gefährlich banalisiert oder lächerlich gemacht, dienen nur noch das interressierte Verkaufen, verlieren jedes Mysterium, werden nicht mehr mit Andacht respektiert. So verlieren ein Volk oder eine Kultur ihren Rückengrat, erleben einen problematischen Sinnverlust, der die ganze Gemeinschaft im verheerenden Untergang stoßen. Postmans Bücher sind wichtig, weil sie uns ganz sachlich auf zeitgenößischen Problemen aufmerksam machen, ohne eine peinlich apokalyptische Sprache zu verwenden. Zum Beispiel ist Postman klar bewußt, daß die Technik lebenswichtig für den Menschen ist, denunziert aber ohne unnötige Pathos die gefährliche Autonomisierung von technischen Verfahren. Postman plädiert nicht für eine irrationale Technophobie. Schmittianer werden in seiner Analyse der unsichtbaren Technologien, wie das Management, eine tagtägliche Quelle der Delegitimierung und Legalisierung der politischen Gemeinschaften. Politisch gesehen, könnten die soziologischen Argumente und Analysen von Postman eine nützliche Illustration der Legalität/Legitimität-Problematik sein (Robert STEUCKERS).

Diese Vorstellung ist um so gefährlicher, als sie niemand mit vernünftigen Gründen gegen den rationalen Einsatz von Verfahren und Techniken stellen kann, mit denen sich bestimmte Vorhaben verwirklichen lassen. (...) Die Kontroverse betrifft den Triumph des Verfahrens, seine Erhöhung zu etwas Heiligem, wodurch verhindert wird, daß auch andere Verfahrensweisen eine Chance bekommen» (S. 153-154). Weiter warnt uns Postman von einer unheimlichen Gefahr, d. h. die Gefahr der Entleerung der Symbole. Wenn traditionnelle oder religiöse Symbole beliebig manipuliert oder verhöhnt werden, als ob sie mechanische Teilchen wären, entleeren sie sich. Hauptschuldige daran ist die Werbung, die einen ständig größeren Einfluß über unseres tägliche Denken ausübt und die die Jugend schlimm verblödet, so daß sie alles im Schnelltempo eines Werbungsspot verstehen will. Um Waren zu verkaufen, manipulieren die Werbeleute gut bekannte politische, staatliche oder religiöse Symbole. Diese werden dann gefährlich banalisiert oder lächerlich gemacht, dienen nur noch das interressierte Verkaufen, verlieren jedes Mysterium, werden nicht mehr mit Andacht respektiert. So verlieren ein Volk oder eine Kultur ihren Rückengrat, erleben einen problematischen Sinnverlust, der die ganze Gemeinschaft im verheerenden Untergang stoßen. Postmans Bücher sind wichtig, weil sie uns ganz sachlich auf zeitgenößischen Problemen aufmerksam machen, ohne eine peinlich apokalyptische Sprache zu verwenden. Zum Beispiel ist Postman klar bewußt, daß die Technik lebenswichtig für den Menschen ist, denunziert aber ohne unnötige Pathos die gefährliche Autonomisierung von technischen Verfahren. Postman plädiert nicht für eine irrationale Technophobie. Schmittianer werden in seiner Analyse der unsichtbaren Technologien, wie das Management, eine tagtägliche Quelle der Delegitimierung und Legalisierung der politischen Gemeinschaften. Politisch gesehen, könnten die soziologischen Argumente und Analysen von Postman eine nützliche Illustration der Legalität/Legitimität-Problematik sein (Robert STEUCKERS).

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Nouvelle Droite, Philosophie, Sociologie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : neil postman, technocratisme, livre, synergies européennes, nouvelles droite, robert steuckers |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 21 septembre 2013

Kerry Bolton: Revolution from Above

Kerry Bolton: Revolution from Above

By Manfred Kleine-Hartlage

Ex: http://www.sezession.de

Jeder, der einmal versucht oder auch nur theoretisch erwogen hat, einen größeren geistig-politischen Umschwung herbeizuführen – von einer Revolution ganz zu schweigen –, weiß, daß dazu vor allem eines erforderlich ist: Geld.

Jeder, der einmal versucht oder auch nur theoretisch erwogen hat, einen größeren geistig-politischen Umschwung herbeizuführen – von einer Revolution ganz zu schweigen –, weiß, daß dazu vor allem eines erforderlich ist: Geld.

Geld bringt Journalisten dazu, bestimmte Themen hoch- oder niederzuschreiben, Geld veranlaßt Professoren, ihre Erkenntnisinteressen denen ihrer Drittmittelgeber anzupassen, Geld ermöglicht es, Zeitungen und Fernsehsender zu kaufen, mit Geld kann man Kurse für Agitatoren und solche, die es werden wollen, bezahlen, mit Geld eine Infrastruktur von „Nichtregierungsorganisationen“ unterhalten, und wenn all dies nicht reicht, kann man mit Geld Waffen kaufen.

Obwohl dies so offenkundig ist, daß man es schon banal nennen muß, ist es zugleich ein Tabuthema. Jeder weiß zwar, daß etwa die Bolschewiki eine Organisation von „Berufsrevolutionären“ waren; und jeder, der darüber nachdenkt, könnte sich sagen, daß Berufsrevolutionäre – wie alle anderen Berufstätigen auch – auf Arbeitgeber oder Kunden angewiesen sind, die sie bezahlen. Und doch gilt die Oktoberrevolution bis heute als das Werk eines gewissen Lenin, nicht etwa als das seiner Geldgeber. Allenfalls gesteht man zu, daß die Millionensummen, die die deutsche Regierung während des Ersten Weltkriegs zur Verfügung stellte, eine gewisse Rolle gespielt haben mögen. Daß entsprechende Summen aber schon lange vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg an die Bolschewisten und andere revolutionäre Organisationen flossen, und daß sie keineswegs aus Deutschland stammten, sondern aus amerikanischen Finanzkreisen: Das ist zwar kein Geheimnis, sondern wohldokumentiert; im offiziösen Geschichtsbild kommt es aber nicht vor.

Dabei ist die Russische Revolution noch dasjenige Thema, bei dem der kausale Zusammenhang zwischen den Interessen schwerreicher Finanziers und der Entfesselung der Revolution am ehesten thematisiert werden kann. Wer dagegen fragt, warum 1789 wie auf Kommando in ganz Frankreich Agitatoren auftauchten, die ein gar nicht so unzufriedenes Volk aufzuhetzen verstanden, sieht sich schnell als „Verschwörungstheoretiker“ abgestempelt, und erst recht gilt dies für den, der den ominösen „Zeitgeist“ hinterfragt, der – man weiß nicht wie – seit rund hundert Jahren, spätestens aber seit dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, grundsätzlich nur von links zu wehen scheint.

Wiederum ist es nicht wirklich ein Geheimnis, daß dieser Zeitgeist keineswegs von selbst entstanden ist, und es ist auch kein Geheimnis, wer seine Entstehung organisiert und finanziert hat: Die verantwortlichen Akteure rühmen sich dessen sogar und geben in ihren Veröffentlichungen detailliert Auskunft darüber. Und doch haben diese allgemein zugänglichen Informationen kaum Eingang ins herrschende politische Bewußtsein gefunden.

In seinem Buch „Revolution from Above“ [2], das zur Zeit leider nur auf Englisch verfügbar ist, hat der neuseeländische Autor Kerry Bolton diese Informationen zusammengetragen und zu einem theoretisch überzeugenden und empirisch unanfechtbar untermauerten Ganzen zusammengefügt. Er weist überzeugend – und dies ausschließlich auf der Basis von Selbstzeugnissen der einschlägigen Akteure! – nach, daß praktisch alle intellektuellen und politischen Strömungen der Linken im 20. Jahrhundert, soweit sie nicht von der UdSSR finanziert wurden, nur aufgrund der milliardenschweren Unterstützung durch eine winzige Schicht von amerikanischen Superreichen und deren Stiftungen zum Zuge kommen konnten. Zumindest hätten sie ohne diese Unterstützung bei weitem nicht die Durchschlagskraft haben können, die sie haben.

Ein solcher Befund mag denjenigen überraschen, der den Gegensatz von Kapitalisten und Sozialisten immer noch für unüberbrückbar hält. Tatsächlich war er das nie. Die Linke leistet dem Kapital vielmehr gute Dienste bei der Zerstörung hergebrachter Strukturen, Bindungen und Werte. Sie planiert damit das Gelände, auf dem der globale Kapitalismus errichtet wird. Sie zerstört reale, gewachsene Solidarität im Namen einer fiktiven und bloß ideologisch postulierten, und sie erzeugt damit die Gesellschaft von atomisierten Einzelnen, die auf ihre Rolle als Produzenten und Konsumenten zurückgeworfen werden und als Masse so lenkbar und nutzbar sind wie eine Viehherde. Das gilt für die russischen und chinesischen Kommunisten, die eine traditionelle agrarische Gesellschaft ins Industriezeitalter katapultierten und schließlich in den Weltmarkt einbanden; es gilt genauso für die westliche Linke mit ihrem Kampf gegen Nation, Tradition, Religion und Familie.

Boltons Buch ist die passende Ergänzung zu meinen eigenen Ausführungen zu diesem Thema (in „Die liberale Gesellschaft und ihr Ende“ [3]). Wo ich die Zusammenhänge abstrakt analysiere, nennt er konkrete Namen, Summen, Profiteure und Strategien. Steinchen für Steinchen entsteht dabei das Mosaik einer langfristigen Strategie der amerikanischen Plutokratie, die auf nicht mehr und nicht weniger hinausläuft als auf eine Weltrevolution – eben auf die Revolution von oben, der das Buch seinen Titel verdankt.

Solche Bücher können auch entmutigen: Wie will man denn, so mag mancher Leser fragen, einem Feind entgegentreten, der an allen Fronten unter Einsatz schier unbegrenzter Mittel auf dem Vormarsch ist? Ist da nicht jeder Widerstand von vornherein zumm Scheitern verurteilt?

Ich selbst ziehe den umgekehrten Schluß: Wenn der Feind Milliardensummen einsetzt, dann deshalb, weil er es nötig hat. Wer ganze Völker mit einem geschlossenen System von Lügen indoktrinieren muss, muß wesentlich mehr investieren als der, der es sich leisten kann, mit Wahrheiten zu operieren. Freilich rechtfertigt auch diese Feststellung nicht eine in manchen Kreisen immer noch verbreitete naive rechte Sozialromantik, die ohne professionelle Strukturen auszukommen glaubt, weil die Wahrheit sich allein durch den Idealismus ihrer Verfechter durchsetzen werde.

Kerry Boltons Buch ist insofern kein Anlaß zu Resignation, wohl aber zu produktiver Ernüchterung: Wir kommen mit weniger Geld aus als der Gegner, aber auch wir werden viele Millionen Euro benötigen, um einen spürbaren politischen Effekt zu erzielen. Es wird Zeit, daß diese Einsicht sich unter den besser betuchten Sympathisanten der politischen Rechten herumspricht.

Article printed from Sezession im Netz: http://www.sezession.de

URL to article: http://www.sezession.de/40908/kerry-bolton-revolution-from-above.html

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.sezession.de/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/kerry-bolton-revolution-from-above.jpg

[2] „Revolution from Above“: http://www.arktos.com/revolution-from-above.html

[3] „Die liberale Gesellschaft und ihr Ende“: http://antaios.de/detail/index/sArticle/314/sCategory/13

19:09 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : kerry bolton, nouvelle droite américaine, livre |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 19 septembre 2013

Silvio Gesell: der “Marx” der Anarchisten

Robert STEUCKERS:

Silvio Gesell: der “Marx” der Anarchisten

Analyse: Klaus SCHMITT/Günter BARTSCH (Hrsg.), Silvio Gesell, “Marx” der Anarchisten. Texte zur Befreiung der Marktwirtschaft vom Kapitalismus und der Kinder und Mütter vom patriarchalischen Bodenunrecht, Karin Kramer Verlag, Berlin, 1989, 303 S., ISBN 3-87956-165-6.

Silvio Gesell war ein nonkonformistischer Ökonom. Er nahm zusammen mit Figuren sowie Niekisch, Mühsam und Landauer an der Räteregierung Bayerns teil. Der gebürtige Sankt-Vikter entwickelte in seinem wichtigsten Buch “Die natürliche Ordnung” ein Projekt der Umverteilung des Bodens, damit ein Jeder selbständig-autonom in totaler Unabhängigkeit von abstrakten Strukturen leben konnte. Günter Bartsch nennt ihn ein “Akrat”, d.h. ein Mensch, der frei von jeder Bevormündung ist, sei diese politischer, religiöser oder verwaltungsartiger Natur. Für Klaus Schmitt, der Gesell für die deutsche nonkonforme Linke wiederentdeckt (aber nicht kritiklos), ist der räterepublikanische Akrat ein der schärfsten Kritiker der “Macht Mammons”. Diese Allmacht wollte Gesell mit der Einführung eines “Schwundgeldes” bzw. einer “Freigeld-Lehre” zerschmettern. Unter “Schwundgeld” verstand er ein Geld, das man nicht thesaurisieren konnte und für das keine Zinsen gezahlt wurden. Im Gegenteil war für Gesell die Hortung von Geldwerten die Hauptsünde. Geld, das nicht in Sachen (Maschinen, Geräte, Technik, Erziehung, Boden, Vieh, usw.) investiert wird, mußte durch moralischen und ökonomischen Zwang an Wert verlieren. Solche Ideen entwickelten auch der Vater des kanadischen und angelsächsichen Distributismus, C. H. Douglas, und der Dichter Ezra Pound, der in den amerikanischen Regierung ein Instrument des Teufels Mammon sah. Douglas entwickelte distributistische Bauern-Projekte in Kanada, die teilweise noch heute existieren. Pound drückte seinen Dichterhaß gegen Geld- und Bankwesen, indem er die italienischen “Saló-Republik” am Ende des Krieges unterstütze. Pound versuchte, seine amerikanische Landgenossen zu überzeugen, keinen Krieg gegen Mussolini und das spätfaschistischen Italien zu führen. Nach 1945, wurde er in den VSA zwölf Jahre lang in einer Irrenanstalt eingesperrt. Er kam trotzdem aus dieser Hölle ungebrochen zurück und ging bei seiner Dochter Mary de Rachewiltz in Südtirol wohnen, wo er 1972 starb.

Silvio Gesell war ein nonkonformistischer Ökonom. Er nahm zusammen mit Figuren sowie Niekisch, Mühsam und Landauer an der Räteregierung Bayerns teil. Der gebürtige Sankt-Vikter entwickelte in seinem wichtigsten Buch “Die natürliche Ordnung” ein Projekt der Umverteilung des Bodens, damit ein Jeder selbständig-autonom in totaler Unabhängigkeit von abstrakten Strukturen leben konnte. Günter Bartsch nennt ihn ein “Akrat”, d.h. ein Mensch, der frei von jeder Bevormündung ist, sei diese politischer, religiöser oder verwaltungsartiger Natur. Für Klaus Schmitt, der Gesell für die deutsche nonkonforme Linke wiederentdeckt (aber nicht kritiklos), ist der räterepublikanische Akrat ein der schärfsten Kritiker der “Macht Mammons”. Diese Allmacht wollte Gesell mit der Einführung eines “Schwundgeldes” bzw. einer “Freigeld-Lehre” zerschmettern. Unter “Schwundgeld” verstand er ein Geld, das man nicht thesaurisieren konnte und für das keine Zinsen gezahlt wurden. Im Gegenteil war für Gesell die Hortung von Geldwerten die Hauptsünde. Geld, das nicht in Sachen (Maschinen, Geräte, Technik, Erziehung, Boden, Vieh, usw.) investiert wird, mußte durch moralischen und ökonomischen Zwang an Wert verlieren. Solche Ideen entwickelten auch der Vater des kanadischen und angelsächsichen Distributismus, C. H. Douglas, und der Dichter Ezra Pound, der in den amerikanischen Regierung ein Instrument des Teufels Mammon sah. Douglas entwickelte distributistische Bauern-Projekte in Kanada, die teilweise noch heute existieren. Pound drückte seinen Dichterhaß gegen Geld- und Bankwesen, indem er die italienischen “Saló-Republik” am Ende des Krieges unterstütze. Pound versuchte, seine amerikanische Landgenossen zu überzeugen, keinen Krieg gegen Mussolini und das spätfaschistischen Italien zu führen. Nach 1945, wurde er in den VSA zwölf Jahre lang in einer Irrenanstalt eingesperrt. Er kam trotzdem aus dieser Hölle ungebrochen zurück und ging bei seiner Dochter Mary de Rachewiltz in Südtirol wohnen, wo er 1972 starb.

Neben seiner ökonomischen Lehren über das Schwund- und Freigeld, theorisierte Gesell einen Anarchofeminismus, wobei er besonders die Kinder und die Frauen gegen männliche Ausbeutung schützen wollte. Diese Interpretation des matriarchalischen Archetyp implizierte eine ziemlich scharfe Kritik des Vaterrechts, der in seinen Augen die Position der Kinder in der Gesellschaft besonders labil machte. Insofern war Gesell ein Vorfechter der Kinderrechte. Praktish bedeutete dieser Anarchofeminismus die Einführung einer “Mutterrente”. «Gesell und sein Anhänger wollten den gesamten Boden den Müttern zueignen und ihnen bzw. ihren Kinder die Bodenrente bis zum 18. Lebensjahr der Kinder als “Mutter-” bzw. “Kinderrente” zukommen lassen. Ein “Bund der Mütter” soll den gesamten nationalen und in ferner Zukunft den gesamten Boden unseres Planeten verwalten und (...) an den oder die Meistbietenden verpachten. Nach diesem Verfahren hätte jeder einzelne Mensch und jede einzelne Gruppe (z. B. eine Genossenschaft) die gleichen Chancen wie alle anderen, Boden nutzen zu können, ohne von privaten oder staatlichen Parasiten ausgebeutet zu werden» (S. 124). Wissenschaftliche Benennung dieses Systems nach Gesell hieß “physiokratische Mutterschaft”.

Neben seiner ökonomischen Lehren über das Schwund- und Freigeld, theorisierte Gesell einen Anarchofeminismus, wobei er besonders die Kinder und die Frauen gegen männliche Ausbeutung schützen wollte. Diese Interpretation des matriarchalischen Archetyp implizierte eine ziemlich scharfe Kritik des Vaterrechts, der in seinen Augen die Position der Kinder in der Gesellschaft besonders labil machte. Insofern war Gesell ein Vorfechter der Kinderrechte. Praktish bedeutete dieser Anarchofeminismus die Einführung einer “Mutterrente”. «Gesell und sein Anhänger wollten den gesamten Boden den Müttern zueignen und ihnen bzw. ihren Kinder die Bodenrente bis zum 18. Lebensjahr der Kinder als “Mutter-” bzw. “Kinderrente” zukommen lassen. Ein “Bund der Mütter” soll den gesamten nationalen und in ferner Zukunft den gesamten Boden unseres Planeten verwalten und (...) an den oder die Meistbietenden verpachten. Nach diesem Verfahren hätte jeder einzelne Mensch und jede einzelne Gruppe (z. B. eine Genossenschaft) die gleichen Chancen wie alle anderen, Boden nutzen zu können, ohne von privaten oder staatlichen Parasiten ausgebeutet zu werden» (S. 124). Wissenschaftliche Benennung dieses Systems nach Gesell hieß “physiokratische Mutterschaft”.

Neben den langen Aufsätzen von Bartsch und Schmitt enthält das Buch auch Texte von Gustav Landauer (“Sehr wertvolle Vorschläge”) und Erich Mühsam (“Ein Wegbahner. Nachruf zum Tode Gesells 1930”).

Fazit: Das Buch hilft uns, die Komplexität und Verwicklung von Ideen zu verstehen, die in der Räterepublik anwesend waren. Ist Niekisch wiederentdeckt und breit kommentiert, so ist seine Nähe zu Personen wie Landauer, Mühsam und Gesell kaum erforscht. Auch interressant wäre es, die Beziehungspunkte zwischen Gesell, Douglas und Pound zu analysieren und zu vergleichen. Letztlich wäre es auch, die Lehren Gesells mit den national-revolutionären Theorien eines Henning Eichbergs in den Jahren 60 und 70 und mit dem Gedankengut, das eine Zeitschrift wie Wir Selbst verbreitet hat. Eichberg hat ja auch immer den Akzent auf das Mütterliche gelegt. Er sprach eher von einem mütterlich-schützende Mutterland statt von einem patriarchalisch-repressive Vaterland. Ähnlichkeiten, die der Ideen-Historiker nicht vernachlässigen kann (Robert STEUCKERS).

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Livre, Livre, Nouvelle Droite, Synergies européennes, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : silvio gesell, anarchisme, allemagne, histoire, nouvelle droite, théorie politique, sciences politiques, politologie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 13 septembre 2013

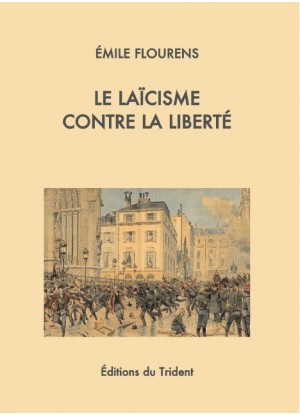

Pour une séparation du Laïcisme et de l'État

Pour une séparation du Laïcisme et de l'État

par Jean-Gilles MALLIARAKIS

Ex: http://www.insolent.fr

Peillon s'est encore fait remarquer pour la rentrée scolaire. Le personnage communique beaucoup. Tel Robespierre, qu'il admire et qui, cependant signa son arrêt de mort à la Fête de l'Être suprême, il pose en grand maître d'une religion [presque] nouvelle.

Peillon s'est encore fait remarquer pour la rentrée scolaire. Le personnage communique beaucoup. Tel Robespierre, qu'il admire et qui, cependant signa son arrêt de mort à la Fête de l'Être suprême, il pose en grand maître d'une religion [presque] nouvelle.

Tout cela le prétentieux personnage l'écrit lui-même.

Qu'on en juge par ses propres citations :

On remarquera d'abord que, comme beaucoup d'esprits marqués par l'enseignement de la philosophie, il fait bon marché de la connaissance concrète de l'Histoire. Voici en effet comment il définit la révolution :

"La révolution française est l’irruption dans le temps de quelque chose qui n’appartient pas au temps, c’est un commencement absolu, c’est la présence et l’incarnation d’un sens, d’une régénération et d’une expiation du peuple français. 1789, l’année sans pareille, est celle de l’engendrement par un brusque saut de l’histoire d’un homme nouveau. La révolution est un événement méta-historique, c’est-à-dire un événement religieux." (1)⇓

Et il enchaîne donc par cette conclusion, certes logique, mais terrifiante :

"La révolution implique l’oubli total de ce qui précède la révolution. Et donc l’école a un rôle fondamental, puisque l’école doit dépouiller l’enfant de toutes ses attaches pré-républicaines pour l’élever jusqu’à devenir citoyen. C’est une nouvelle naissance, une transsubstantiation qui opère dans l’école et par l’école cette nouvelle église avec son nouveau clergé, sa nouvelle liturgie, ses nouvelles tables de la loi."

On se situe exactement dans cette idée rousseauiste "il faut les forcer d'être libres" qu'Augustin Cochin souligne. (2)⇓

Peillon ose écrire : "La laïcité elle-même peut alors apparaître comme cette religion de la République recherchée depuis la Révolution". (3)⇓

Mais il déclare par ailleurs ouvertement que "la franc-maçonnerie est la religion de la république". (4)⇓

Le laïcisme qu'il professe se veut par conséquent l'expression profane, le mot d'ordre, – et comme le mot "républicain",– le mot de passe d'une secte, d'ailleurs divisée, dont on rappellera qu'au sein de l'Éducation dite Nationale elle doit représenter au maximum 1 % des fonctionnaires eux-mêmes, malgré sa réputation d'ascenseur professionnel : ce qui doit bien vouloir dire qu'elle dégoûte les autres 99 %.

Cessons donc de confondre laïcité et neutralité. L'un des fondateurs du système, Viviani, qui fut président du Conseil au moment de la déclaration de guerre de 1914, l'écrivait à l'époque: "La neutralité est, elle fut toujours un mensonge [...]. Un mensonge nécessaire lorsque l’on forgeait, au milieu des impétueuses colères de la droite, la loi scolaire [...]. On promit cette chimère de la neutralité pour rassurer quelques timidités dont la coalition eût fait obstacle au principe de la loi. Mais Jules Ferry avait l’esprit trop net pour croire en l’éternité de cet expédient [...]." (5)⇓

Le développement de l'éducation étatique a toujours été conçu en vue de perpétuer le système.

Le fonctionnement de cette coûteuse administration, lourdement centralisée, se révèle d'année en année plus improductif, et plus destructeur.

Les écoles d'État ne parviennent plus à enseigner aux enfants de France à lire, écrire et compter. Mais on veut, par l'effet du laïcisme totalitaire, faire semblant d'imposer avec une soi-disant "morale laïque", dont personne ne connaît les fondements, un recul de l'islamisme, lâchement, sans oser le nommer : cette rustine méprisable, poisseuse et liberticide ne servira à rien. Jetons la sans hésiter. Séparons le laïcisme de l'État.

JG Malliarakis

Apostilles

- cf. "La révolution française n’est pas terminée" Seuil 2008 page 17⇑

- *cf. "Les sociétés de pensée et la démocratie moderne" Éditions du Trident. ⇑

- Ibidem p. 162 ⇑

- cf. ses déclarations destinées à promouvoir son livre enregistrées au départ sur le site de son éditeur.⇑

- cf. L’Humanité 4 octobre 1904.⇑

Si vous appréciez le travail de L'Insolent

soutenez-nous en souscrivant un abonnement.

Pour recevoir régulièrement des nouvelles de L'Insolent

inscrivez-vous gratuitement à notre messagerie.

Si vous cherchez des lectures intelligentes pour l'été >

Visitez le catalogue des Éditions du Trident et commandez en ligne.

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : jean-gilles malliarakis, laïcisme, laïcité, état, france, livre, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 12 septembre 2013

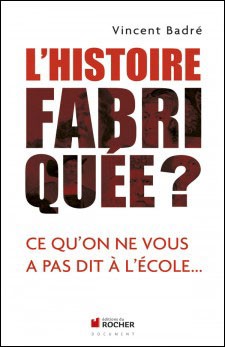

L’histoire fabriquée

Pierre LE VIGAN

Ex: http://metamag.fr

Peut mieux faire. C’est le moins que l’on puisse dire à propos de beaucoup de manuels scolaires d’histoire dans le secondaire. Mais il est vrai qu’il faudrait aussi plus de temps pour enseigner l’histoire. Vincent Badré remet les pendules à l’heure. Reprenant le contenu des principaux manuels en circulation il expose les faits et idées enseignées, indique leur part de vérité, mais parfois aussi leur part de contre-vérité.

Peut mieux faire. C’est le moins que l’on puisse dire à propos de beaucoup de manuels scolaires d’histoire dans le secondaire. Mais il est vrai qu’il faudrait aussi plus de temps pour enseigner l’histoire. Vincent Badré remet les pendules à l’heure. Reprenant le contenu des principaux manuels en circulation il expose les faits et idées enseignées, indique leur part de vérité, mais parfois aussi leur part de contre-vérité.

00:04 Publié dans Ecole/Education, Histoire, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, histoire, école, éducation, enseignement |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 10 septembre 2013

The Gentleman from Providence

The Gentleman from Providence

By Alex Kurtagić

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

S. T. Joshi

I Am Providence: The Life and Times of H. P. Lovecraft [2]

2 vols.

New York: Hippocampus Press, 2012

When it comes to a truly comprehensive biography of Howard Philip Lovecraft, one cannot do better than S. T. Joshi’s I am Providence, a 2 volume, 1,000-page, 500,000-word mammoth of a book that aims to cover everything there is to know about the American master of the weird tale.

As with Mark Finn, whose biography of Howard I reviewed recently, it would seem that L. Sprague de Camp was what spurred Joshi into action: after reading the latter’s Lovecraft: A Biography upon initial publication in 1975, Joshi dedicated his life thereafter to the study of the author from Providence. His choice of university was dictated by its holding the Lovecraft manuscript collection of the John Hay Library. And when he discovered that At the Mountains of Madness, his favourite Lovecraft story, contained no less than 1,500 textual errors, he devoted the ensuing years to tracking down and examining manuscripts and early publications in order to determine the textual history of the work and make possible a corrected edition of Lovecraft’s collected fiction, “revisions,” and other writings. What we have here, you may confidently conclude, is the product of decades of fanaticism and obsessive investigation.

Lovecraft was born in 1890, into a conservative upper middle class family, in Providence, Rhode Island. His father, Winfield, was a travelling salesman, employed by Gorham & Co., Silversmiths, and his mother, Sarah, could trace her ancestry back to the arrival of George Phillips to Massachusetts in 1630. His parents married in their thirties.

The young Lovecraft was talented, intellectually curious, and precocious, able to recite poetry by age two, and to read by age three. Growing up at a time when school was not compulsory, Lovecraft would not be enrolled in one until he was eight years of age and his attendance would be sporadic, possibly due to a nervous complaint and / or psychosomatic condition. But he was well ahead of his coevals in any event, having been exposed, and thereafter enjoyed ready access, to the best of classical and English literature. From Lovecraft’s perspective, this meant 17th and early 18th century prose and poetry, and, indeed, so steeped was he in the canonical literature from this period that he regarded its style of writing not only the finest ever achieved, but, for him, the norm. In the process, he also absorbed some of the archaic tastes and sensibilities permeating this literature, which would subsequently be reflected in his writing, speech, and attitudes, fundamentally aristocratic and at odds with the 20th century. What is more, Lovecraft was never denied anything he may have needed in the pursuit of his intellectual development, be it a chemistry set, a telescope, or printing equipment, so he became knowledgeable enough on these topics, and particularly his passion, astronomy, to contribute articles to a local publication from an early age. He also regularly produced—while still in infancy—his own amateur scientific journals, many of which still survive and were personally examined by Joshi for this biography. Thus, from early on, Lovecraft, a somewhat lonely boy with a charmed boyhood, was committed to a life entirely of the mind.

With such beginnings, it would appear to a casual observer that Lovecraft was well-equipped to become a success in life. But, instead, in adulthood he experienced ever-worsening poverty, squalor, and, though well known for a period within the specialised milieu of amateur publishing, growing professional obscurity. That his legacy has endured owes—besides to the intrinsic value of his works—perhaps in a not insignificant measure to his having been a prodigous correspondent: it has been estimated that throughout the course of his life Lovecraft may have written as many as 100,000 letters (only about 20,000 of which survive), and these were not hastily penned missives, as can be seen in the many excerpts herein presented, but thoughtful communications, sometimes of up to 30 pages in length, which are works of literatue in themselves.

In examining his overall trajectory, we can identify a number of negative vectors early on. The loss of his father, who, following a psychotic episode and permanent committal to a local hospital, suffering from what Joshi presumes to have been syphilis, meant that, from 1893, Lovecraft passed into the care of his mother, aunts, and his maternal grandfather. Whipple van Buren Phillips, a wealthy businessman, proved a positive influence, but died in 1904, and, his estate being poorly managed, this eventually forced the family to downsize. This badly affected the young Lovecraft, to the point that he briefly contemplated suicide. He was eventually dissuaded by his own intellectual curiosity and love of learning.

In 1908, just prior to his high school graduation, Lovecraft suffered a nervous breakdown. Joshi speculates that failure to master higher mathematics may have been a factor, since Lovecraft’s ambition was to become a professional astronomer. (Failure to master meant not getting straight As, but, among the As, a few A-s and Bs.) Whatever its cause, the breakdown prevented Lovecraft from obtaining his diploma, a fact he would later conceal or minimise. Lovecraft then went into seclusion—hikikomori, as it would be called today—in which condition he remained for five years, mostly reading and writing poetry. Joshi expresses alarm at the sheer volume of reading undertaken by Lovecraft during this period, a large portion of it consisting of magazines.

Lovecraft’s re-emergence owes to his irritation with a pulp author, Fred Jackson, whose stories in Argosy magazine he found maudlin, mediocre, and irritating. His letter was published in the magazine, whereby it detonated an opinionated debate. When Lovecraft’s expressed view led to attacks, he responded in lofty and witty verse, thus instigating a months-long war—in archaic rhyme—in the letters’ page. This got him noticed by the president of the United Amateur Press Association (UAPA), Edward F. Daas, who invited Lovecraft to join. This inaugurated Lovecraft’s amateur career, which led to his return to fiction—something he had dabbled in years before—and, by 1919, to his first commerically published work. During his early years in amateurdom, Lovecraft would also produce his own literary journal, The Conservative, a publication that truly lived up to its name and that has only recently been reprinted by Arktos in unabridged form.

Throughout this period Lovecraft continued to live with his mother, who sustained them both off an ever-shrinking inheritance. Trapped between the expectations of her class and dwindling resources, she grew progressively more neurotic and unstable. She already had an unheathily close, love-hate, relationship with her son, and Joshi records that she considered her son’s visage too ugly for public view. By 1919, suffering from hysteria and clinical depression, she would be committed to hospital, where she would remain for the rest of her days. Mother and son stayed close correspondents, but she was a perennial source of worry. Thus, when Sarah died in 1921, initial grief led to a sense of liberation, and an improvement in Lovecraft’s general health—though he, at this time a tall man of nearly 200 lbs, always regarded himself as ailing.

Yet there were further turns to the worst ahead. In 1921, at a convention for amateur journalists in Boston, Lovecraft met Sonia Green, an assimilated 38-year-old Ukrainian Jew from New York, whom he would marry in 1924. Interestingly, Lovecraft only told his aunt after the fact, writing to her from New York, where he had by then already taken residence at Sonia’s apartment.

Joshi notes that at this time Lovecraft’s prospects appeared to be improving: Sonia earned a good living at a hat shop in Fifth Avenue, and Lovecraft’s professional writing career was taking off. Lovecraft, then in a decadent phase, was also enthralled by the city, where he had a number of amateur friends. However, Sonia lost her job almost immediately when the shop went bankrupt. This forced Lovecraft for the first time to find regular employment, but without qualifications, work experience, nor, apparently, marketable skills, he was unable to find a position. The consequent financial difficulties impacted on Sonia’s health, who entered a sanatorium for a period of recovery. Eventually, she would find a job in Cleveland, leaving Lovecraft to live on his own, in a tiny apartment, in Brooklyn Heights (then Red Hook), back then a seedy neighbourhood. Sonia sent him an allowance, which permitted him to cover his rent and minimal expenses, but otherwise Lovecraft lived in poverty, stretching as far as possible a minuscule fare of unheated beans, bread, and cheese.

This was, however, genteel poverty. When, on one occasion, Lovecraft’s apartment was burglarised, he was left with only the clothes on his back (while he slept, the thieves gained access to his closet and stole all his suits). His reaction says much about Lovecraft: first priority for him was to get four new replacements: light and dark, winter and summer—no easy task, given his slender wallet. A gentleman may be poor, but he must still dress like a gentleman! The ensuing hunt for suitable attire taxed Lovecraft’s ingenuity, and ignited his frustration at the shoddy quality of modern suits (Lovecraft’s original suits had been made in happier times). Eventually, he succeeded, with minimal compromise.

Seething with immigrants of all descriptions, crowded, and filthy, Lovecraft came to despise New York, recognising it as an emblem of modern degeneration (remember: he already thought this in 1925!). This negative opinion does not sit well with Joshi: having immigrated from India at a young age and having been a New York resident for 27 years, Joshi puts Lovecraft through the wringer for failing to appreciate the city’s vibrancy. Here and elsewhere, he attacks Lovecraft for his enamourment with Anglo-Saxondom, his fierce resistance to racial egalitarianism, and his rejection of the multicultural society. In Joshi’s estimation, Lovecraft ought to have considered Franz Boas’ research, which was beginning to transform anthropology at this time; Joshi views this as contrary to Lovecraft’s rigorous scientific outlook—in other words, as Lovecraft having been blinded by prejudice. However, this overlooks the fact that there were different strands of opinion in anthropology at this time: this was the Progressive Era, when the American eugenics movement was at its height, enjoying institutional legitimacy, famous proponents (e.g. John Harvey Kellogg), and backing from the likes of the Rockefeller Foundation, the Carnegie Institution, and the the Harriman estate. Boas’ findings were politically motivated and not universally accepted, and he had by no means proven his case. (Worse still, since then there have been accusations of scientific fraud.) It would, therefore, seem that Lovecraft was entirely consequent with his aristocratic and scientific worldview.

Though Joshi deems it necessary to shoehorn his views on race and racism—zzz . . . —he shows admirable restraint, all things considered—though he has still been criticised by readers. He clearly struggles to reconcile his admiration for Lovecraft with an imagined rejection by him, which is coloured by the absurdities of the modern discourse on these matters. As the author of The Angry Right: Why Conservatives Keep Getting it Wrong (2006), where he invects against liberals like William Buckley and Rush Limbaugh, and where he welcomes the Leftward drift of American values, he can understand Lovecraft’s own merely as a reflection of the times in which he lived. Yet, Joshi has expended an immense amount of time and energy studying and writing about Lovecraft’s thought and worldview, as expressed both in correspondence and in fiction, and thus makes a fair attempt at describing them at length in a temperate fashion.

Lovecraft would eventually return to Providence, thus marking the beginning of the most productive phase of his career. By this time his marriage to Sonia was essentially over; a final attempt was made, but Lovecraft’s aunts rejected the idea of Sonia setting up shop in Providence, regarding her—or rather, the idea of a businesswoman—as somewhat declassé. Joshi again takes Lovecraft to task for not having shown more backbone before his aunts, but he is, nevertheless, of the opinion that Lovecraft was unsuited for marriage—being emotionally distant, stiff-upper lipped, and sexually sluggish—and ought never to have taken a wife. The Lovecrafts would in time agree on an amicable divorce (though, in the end, and to Sonia’s shock later on, he never signed the decree).

Despite his peaking productivity, Lovecraft’s economic prospects continued to decline. His stories became longer and more complex, and it became increasingly difficult to place them. Farnsworth Wright, Weird Tales’ capricious editor, repeatedly rejected them, though sometimes he would accept some after a period, after lobbying or intercession by one of Lovecraft’s correspondents. His seminal essay on horror fiction, Supernatural Horror in Literature [3], completed at this time, appeared haphazardly and incompletely in tiny amateur publications, and would never appear in its final, revised, complete form during his lifetime. Therefore, Lovecraft, now living in semi-squalor with his aunt in cramped accommodation, was increasingly forced to survive through charging for “revisions,” which, given the amount of hands-on editing and re-writing involved, was for the most part tantamount to ghostwriting. Lovecraft was too much of a gentleman, too generous for his own good, and charged very modest fees. We must remember, however, that Lovecraft, in this same modest spirit, saw himself as a hack.

All the same, through extreme frugality and resourcefulness, Lovecraft still managed to travel yearly around New England, mainly as an antiquary. This resulted in extensive travelogues, written in 18th-century prose, replete with archaisms and therefore neither publishable nor intended for publication. Joshi mentions that some have criticised Lovecraft for expending excessive energy on correspondence and unpublishable travelogues, rather than writing fiction, but he argues that this was Lovecraft’s life, not his critics’—who are they to tell him, posthumously, what he ought to have done?

Joshi notes that the Great Depression forced Lovecraft to reconsider some of his earlier positions, and that he—encouragingly in his view—embraced FDR’s New Deal. He also notes, although briefly, that Lovecraft may have misunderstood the nature of the program. All the same, he likes to describe Lovecraft as having become a “moderate socialist,” even if he is later careful to point out that his socialism was radically distinct from the Marxist conception—in fact, Lovecraft instinctively sympathised with fascism and Hitler’s movement, and would remain firmly opposed to Communism. Lovecraft’s conception of socialism was entirely elitist. From his perspective, the culture-bearing stratum of a civilisation should not, in an ideal world, be shackled by the need to waste time and energy on trivial tasks, out of the need to earn a living: the production of high culture is often incompatible with commercial goals, so, in his view, it demands freedom from economic activity. And this implied some sort of patronage, in the manner that kings, popes, or wealthy aristocrats or businessmen provided to artists in the past. In other words, a portion of the nation’s wealth should be channelled into things of lasting value—and, therefore, into seeing to it that the very few individuals capable of producing them are in a position to do so. Lovecraft conceived this as socialism because he saw it as the task of the best to better the rest, and high art and intellection played an important rôle in that endeavour.

By 1936, Lovecraft, already in constant pain, was diagnosed with bowel cancer. He would die a few months later, on 15 March 1937.

As with Finn’s biography of Robert E. Howard, Joshi carries on beyond the grave to trace Lovecraft’s legacy, and the development of Lovecraft scholarship over the past 75 years. Like Finn, he has complaints about L. Sprague de Camp’s biography, which he deems substandard and inaccurate; he describes de Camp as business-minded (a euphemism for opportunist). Joshi also criticises August Derleth, one of Lovecraft’s correspondents, who acted early on and energetically to preserve Lovecraft’s legacy through his publishing company, Arkham House: as de Camp did with Howard, Derleth sought to extend Lovecraft’s mythology with posthumous “collaborations,” wherein he distorted the mythology by infusing it with his own preconceptions. To Joshi this was a disreputable attempt to market his own fiction using Lovecraft’s name, though Derleth would later become a well-regarded author in his own right.

While Joshi’s biography is impressive in its comprehensiveness and level of detail, I found his compulsion to provide a plot summary of every single story that Lovecraft ever wrote rather tedious and beyond requirements. One can see that the biography’s comprehensive logic dictates their inclusion, and they can be useful, but I wonder if the tomes’ objectives could not have been met without this overwhelming prolixity.

Joshi recognises his subject’s superior character in that, though Lovecraft would have been able to prosper economically had he compromised on quality, produced more, and stuck to what was popular, he remained steadfast in his refusal to do so. Whatever he did, he did to the best of his ability, without homage to Mammon. Readers, says Joshi, should be grateful for that, as it was this that has guaranteed the lasting value of Lovecraft’s work as well as his enduring legacy.

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2013/09/the-gentleman-from-providence/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/iap.gif

[2] I Am Providence: The Life and Times of H. P. Lovecraft: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1614980519/ref=as_li_ss_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=1614980519&linkCode=as2&tag=countercurren-20

[3] Supernatural Horror in Literature: http://shop.wermodandwermod.com/supernatural-horror-in-literature.html

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Livre, Livre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, littérature américaine, lettres, lettres américaines, livre, lovecraft |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 07 septembre 2013

Nietzsche et l'éternité

Pierre Le Vigan

Ex: http://metamag.fr

« La vie éternelle n’est pas une autre vie, mais, précisément, la vie que tu vis » écrivait le philosophe de Sils-Maria. La question de l’éternité est au cœur de la pensée de Nietzsche. Aimer la vie longue est selon lui le contraire d’aimer la vie. L’homme ne se résigne pas à la brièveté. L’homme est malade du manque d’éternité. Pour Nietzsche c’est la cause du nihilisme. L’éternité est pourtant à portée de main. Elle est dans le corps même, ce grand oublié, elle est dans la vie même. C’est la vie elle-même qui crée les valeurs qui rendent inutile le nihilisme. La tentation du nihilisme est inhérente à la vie elle-même mais c’est la vie qui permet de la surmonter. « Nous ne pouvons comprendre que le monde que nous avons créé » explique Nietzsche. Il rejette ainsi toute foi et toutes valeurs extérieures à l’homme. Le principe d’une foi extérieure à l’homme est de refuser le temps cyclique, comme le faisait Augustin d’Hippone. Le monothéisme veut le temps droit et linéaire. Au contraire, Nietzsche affirme que « tout ce qui est droit ment (…), toute vérité est courbée, le temps lui-même est un cercle. » (Zarathoustra). C’était ce qu’exprimait Héraclite : « Pour le temps comme sur le pourtour de la roue, le début et la fin sont communs ».

« La vie éternelle n’est pas une autre vie, mais, précisément, la vie que tu vis » écrivait le philosophe de Sils-Maria. La question de l’éternité est au cœur de la pensée de Nietzsche. Aimer la vie longue est selon lui le contraire d’aimer la vie. L’homme ne se résigne pas à la brièveté. L’homme est malade du manque d’éternité. Pour Nietzsche c’est la cause du nihilisme. L’éternité est pourtant à portée de main. Elle est dans le corps même, ce grand oublié, elle est dans la vie même. C’est la vie elle-même qui crée les valeurs qui rendent inutile le nihilisme. La tentation du nihilisme est inhérente à la vie elle-même mais c’est la vie qui permet de la surmonter. « Nous ne pouvons comprendre que le monde que nous avons créé » explique Nietzsche. Il rejette ainsi toute foi et toutes valeurs extérieures à l’homme. Le principe d’une foi extérieure à l’homme est de refuser le temps cyclique, comme le faisait Augustin d’Hippone. Le monothéisme veut le temps droit et linéaire. Au contraire, Nietzsche affirme que « tout ce qui est droit ment (…), toute vérité est courbée, le temps lui-même est un cercle. » (Zarathoustra). C’était ce qu’exprimait Héraclite : « Pour le temps comme sur le pourtour de la roue, le début et la fin sont communs ».

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, nietzsche |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

A Breviary for the Unvanquished

A Breviary for the Unvanquished

By Michael O'Meara

A propos of Dominique Venner

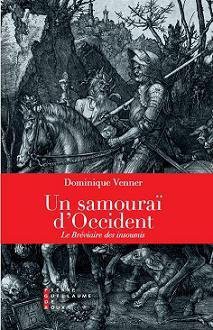

Un Samouraï d’Occident: Le Bréviaire des insoumis [2]

Paris: PGDR, 2013

In his commentaries on the Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar claimed the ancient Celts were ruled by two principles: to fight well and to speak well. By this standard, the now famous essayist, historian, and former insurgent, Dominique Venner, who frequently identified with his Gallic ancestors, was the epitome of Caesar’s Celt—for with arms and eloquence, he fought a life-long war against the enemies of Europe.

In his commentaries on the Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar claimed the ancient Celts were ruled by two principles: to fight well and to speak well. By this standard, the now famous essayist, historian, and former insurgent, Dominique Venner, who frequently identified with his Gallic ancestors, was the epitome of Caesar’s Celt—for with arms and eloquence, he fought a life-long war against the enemies of Europe.

Like much else about him (especially his self-sacrifice on Notre Dame’s high altar, which, as Alain de Benoist writes, made him un personage de l’histoire de France), Venner’s posthumously published Un Samuraï d’Occident bears testament not just to his rebellion against the anti-European forces, but to his faith in the Continent’s tradition and the restorative powers this tradition holds out to a Europe threatened by the ethnocidal forces of the present American-centric system of global usury.

His “samurai” (his model of resistance and rebellion) refers to the “figure” of the aristocratic warrior, once honored in Japan and Europe. Such a figure has, actually, a long genealogy in the West, having appeared 30 centuries ago in Homer’s epic poems. And like a re-occurring theme, this figure continued to animate much of Western life and thought—up until at least 1945.

An especially emblematic illustration of Venner’s warrior is Albrect Dürer’s 1513 engraving of “The Knight, Death, and the Devil.” In the daunting Gothic forest sketched by Dürer, where his solitary knight encounters both the devil and time’s relentless march toward death, the figure of the noble warrior is seen serenely mounted on his proud horse, with a Stoic’s ironic smile on his lips, as he patrols the lurking dangers, accompanied by his dog representing truth and loyalty.

For Venner, Dürer’s timeless rebel does what needs doing, knowing that however high the price he must pay to defend the cosmic order of his world, it will be commensurate with whatever “excellence” (courage and nobility) he finds in himself. It is, in fact, the intensity, beauty, and grandeur of the knight, in his struggle with the forces of death and disorder, that imbue him with meaning. The crueler the destiny, it follows, the greater it is—just as a work of art is great to the degree it transcends tragedy by turning it into a work of beauty.

Contemporary “conservatives” and libertarians struggling with the crisis-ridden economic imperatives of our globalized/miscegenated consumer society, will undoubtedly think Venner’s warrior irrelevant to the great challenges facing it—but this is not the opinion of the “European Resistance” (and it will not likely be the opinion of the European-American Resistance, if one should arise). For between those forming the fake, system-friendly opposition to the liberal nihilism programming our global electronic Gulag—and those European rebels defending the Continent’s millennial tradition and identity—there stretches a gaping ontological abyss.

***

Venner’s book begins with an account of a not uncommon situation in today’s France, especially among the so-called petit blancs—the little people. He cites the case, reported by Le Monde, of one “Catherine C.,” who is what France’s black and brown invaders refer to as a Gauloise: a French native (i.e., someone whose Celtic ancestors fought Caesar’s legions).

All her life Catherine C. has lived in the suburbs of Paris, in a housing estate originally designed to lodge French workers, but now occupied almost exclusively by the invaders. She has hence become a “minority,” a stranger in her own land, abandoned to the whim and rule of the non-Europeans dominating her environment. As such, she rarely leaves her apartment, feeling alienated not just from her “neighbors,” but from the established institutions and authorities favoring the invaders. Even her son, who lacks her sense of French identity, has converted to Islam and wants “to be black or beur [Arab] like everyone else.” But however isolated and threatened, this Gauloise refuses—out of pride—to abandon her home or identity.

We know from other sources that Venner’s resistance to the present anti-white regime began long ago, in his late adolescence, when he took up arms to defend “French Algeria.” His resistance – then on the field of battle (against the outer enemy), later in Parisian street skirmishes (against the inner traitor), and finally on the printed page – has shaped the course of his entire life. Though a “tribal solidarity” and “rebel heart” motivated his initial resistance, the cause of France’s “little people”—the Catherine C.’s—constituting the majority of the nation—became a no less prominent motive for him, especially in that the “little people” of French France are the principal victims of the elites’ criminal system of governance and privilege.

***

“To exist,” Venner argues, “is to struggle against that which denies me.” Since 1945, the whole world has “denied” the European (allegedly “responsible” for the Shoah, slavery, colonization, etc.) the right to exist. At the most fundamental level, this implies that Europeans have no right to an identity: no right to be who they are (given that they are a scourge to humanity). Venner, of course, refused to submit to such tyranny, which has made him a “rebel”: someone who not only refuses to accommodate the reigning subversion, but who remains true to himself in the name of certain higher principles.

Venner’s rebel—the “unvanquished” to use Faulkner’s term—is an offspring of indignation. In face of imposture or sacrilege, the rebel revolts against a violated legitimacy. His rebellion begins accordingly in the conscience before it occurs in arms. Our earliest example of such a rebellion is Sophocles’ Antigone, who rebelled against King Creon’s violation of the sacred law. Like Antigone, Venner’s rebel warrior obeys a transcendent “legitimacy” and resists all that transgresses it; similarly, he never calculates the prospect of success or refuses to pay the often terrible price of rebellion—because a higher defining duty with which he identifies impels him to do so.

Since such rebellion arises from an offended spirit, it often breaks out where least expected. In a life spanning the 20th century’s great catastrophes (World War II, the German Occupation of France, the so-called “Liberation” and its murderous left-wing purges, the Cold War, Decolonization, etc.), Venner has known a Europe paralyzed by dormition (sleep)—too traumatized by the great bloodlettings and destructions of earlier decades to counter her ongoing de-Europeanization. The present “shock of history,” he contends, may change this.