AFRIQUE-ASIE : Sans sponsors et en toute indépendance, à contre-courant des livres de commande publiés récemment en France sur le Qatar, Nicolas Beau et Jacques-Marie Bourget* ont enquêté sur ce minuscule État tribal, obscurantiste et richissime qui, à coup de millions de dollars et de fausses promesses de démocratie, veut jouer dans la cour des grands en imposant partout dans le monde sa lecture intégriste du Coran. Un travail rigoureux et passionnant sur cette dictature molle, dont nous parle Jacques-Marie Bourget.

Écrivain et ancien grand reporter dans les plus grands titres de la presse française, Jacques-Marie Bourget a couvert de nombreuses guerres : le Vietnam, le Liban, le Salvador, la guerre du Golfe, la Serbie et le Kosovo, la Palestine… C’est à Ramallah qu’une balle israélienne le blessera grièvement. Grand connaisseur du monde arabe et des milieux occultes, il publiait en septembre dernier avec le photographe Marc Simon, Sabra et Chatila, au cœur du massacre (Éditions Érick Bonnier, voir Afrique Asie d’octobre 2012)

Nicolas Beau a longtemps été journaliste d’investigation à Libération, au Monde et au Canard Enchainé avant de fonder et diriger le site d’information satirique français, Bakchich. info. Il a notamment écrit des livres d’enquêtes sur le Maroc et la Tunisie et sur Bernard-Henri Lévy.

Qu’est-ce qui vous a amenés à consacrer un livre au Qatar ?

Le hasard puis la nécessité. J’ai plusieurs fois visité ce pays et en suis revenu frappé par la vacuité qui se dégage à Doha. L’on y a l’impression de séjourner dans un pays virtuel, une sorte de console vidéo planétaire. Il devenait intéressant de comprendre comment un État aussi minuscule et artificiel pouvait prendre, grâce aux dollars et à la religion, une telle place dans l’histoire que nous vivons. D’autre part, à l’autre bout de la chaîne, l’enquête dans les banlieues françaises faite par mon coauteur Nicolas Beau nous a immédiatement convaincus qu’il y avait une stratégie de la part du Qatar enfin de maîtriser l’islam aussi bien en France que dans tout le Moyen-Orient et en Afrique. D’imposer sa lecture du Coran qui est le wahhabisme, donc d’essence salafiste, une interprétation intégriste des écrits du Prophète. Cette sous-traitance de l’enseignement religieux des musulmans de France à des imams adoubés par le Qatar nous a semblé incompatible avec l’idée et les principes de la République. Imaginez que le Vatican, devenant soudain producteur de gaz, profite de ses milliards pour figer le monde catholique dans les idées intégristes de Monseigneur Lefebvre, celles des groupuscules intégristes qui manifestent violement en France contre le « mariage pour tous ». Notre société deviendrait invivable, l’obscurantisme et l’intégrisme sont les meilleurs ennemis de la liberté.

Sur ce petit pays, nous sommes d’abord partis pour publier un dossier dans un magazine. Mais nous avons vite changé de format pour passer à celui du livre. Le paradoxe du Qatar, qui prêche la démocratie sans en appliquer une seule once pour son propre compte, nous a crevé les yeux. Notre livre sera certainement qualifié de pamphlet animé par la mauvaise foi, de Qatar bashing… C’est faux. Dans cette entreprise nous n’avons, nous, ni commande, ni amis ou sponsors à satisfaire. Pour mener à bien ce travail, il suffisait de savoir lire et observer. Pour voir le Qatar tel qu’il est : un micro-empire tenu par un potentat, une dictature avec le sourire aux lèvres.

Depuis quelques années, ce petit émirat gazier et pétrolier insignifiant géopolitiquement est devenu, du moins médiatiquement, un acteur politique voulant jouer dans la cour des grands et influer sur le cours de l’Histoire dans le monde musulman. Est-ce la folie des grandeurs ? Où le Qatar sert-il un projet qui le dépasse ?

Il existe une folie des grandeurs. Elle est encouragée par des conseillers et flagorneurs qui ont réussi à convaincre l’émir qu’il est à la fois un tsar et un commandeur des croyants. Mais c’est marginal. L’autre vérité est qu’il faut, par peur de son puissant voisin et ennemi saoudien, que la grenouille se gonfle. Faute d’occuper des centaines de milliers de kilomètres carrés dans le Golfe, le Qatar occupe ailleurs une surface politico-médiatique, un empire en papier. Doha estime que cette expansion est un moyen de protection et de survie.

Enfin il y a la religion. Un profond rêve messianique pousse Doha vers la conquête des âmes et des territoires. Ici, on peut reprendre la comparaison avec le minuscule Vatican, celui du xixe siècle qui envoyait ses missionnaires sur tous les continents. L’émir est convaincu qu’il peut nourrir et faire fructifier une renaissance de la oumma, la communauté des croyants. Cette stratégie a son revers, celui d’un possible crash, l’ambition emportant les rêves du Qatar bien trop loin de la réalité. N’oublions pas aussi que Doha occupe une place vide, celle libérée un temps par l’Arabie Saoudite impliquée dans les attentats du 11-Septembre et contrainte de se faire plus discrète en matière de djihad et de wahhabisme. Le scandaleux passe-droit dont a bénéficié le Qatar pour adhérer à la Francophonie participe à cet objectif de « wahhabisation » : en Afrique, sponsoriser les institutions qui enseignent la langue française permet de les transformer en écoles islamiques, Voltaire et Hugo étant remplacés par le Coran.

Cette mégalomanie peut-elle se retourner contre l’émir actuel ? Surtout si l’on regarde la brève histoire de cet émirat, créé en 1970 par les Britanniques, rythmée par des coups d’État et des révolutions de palais.

La mégalomanie et l’ambition de l’émir Al-Thani sont, c’est vrai, discrètement critiquées par de « vieux amis » du Qatar. Certains, avançant que le souverain est un roi malade, poussent la montée vers le trône de son fils désigné comme héritier, le prince Tamim. Une fois au pouvoir, le nouveau maître réduirait la voilure, notamment dans le soutien accordé par Doha aux djihadistes, comme c’est le cas en Libye, au Mali et en Syrie. Cette option est même bien vue par des diplomates américains inquiets de cette nouvelle radicalité islamiste dans le monde. Alors, faut-il le rappeler, le Qatar est d’abord un instrument de la politique de Washington avec lequel il est lié par un pacte d’acier.

Cela dit, promouvoir Tamim n’est pas simple puisque l’émir, qui a débarqué son propre père par un coup d’État en 1995, n’a pas annoncé sa retraite. Par ailleurs le premier ministre Jassim, cousin de l’émir, le tout-puissant et richissime « HBJ », n’a pas l’intention de laisser un pouce de son pouvoir. Mieux : en cas de nécessité, les États-Unis sont prêts à sacrifier et l’émir et son fils pour mettre en place un « HBJ » dévoué corps et âme à Washington et à Israël. En dépit de l’opulence affichée, l’émirat n’est pas si stable qu’il y paraît. Sur le plan économique, le Qatar est endetté à des taux « européens » et l’exploitation de gaz de schiste est en rude concurrence, à commencer aux États-Unis.

La présence de la plus grande base américaine en dehors des États-Unis sur le sol qatari peut-elle être considérée comme un contrat d’assurance pour la survie du régime ou au contraire comme une épée de Damoclès fatale à plus ou moins brève échéance ?

La présence de l’immense base Al-Udaï est, dans l’immédiat, une assurance vie pour Doha. L’Amérique a ici un lieu idéal pour surveiller, protéger ou attaquer à son gré dans la région. Protéger l’Arabie Saoudite et Israël, attaquer l’Iran. La Mecque a connu ses révoltes, la dernière réprimée par le capitaine Barril et la logistique française. Mais Doha pourrait connaître à son tour une révolte conduite par des fous d’Allah mécontents de la présence du « grand Satan » en terre wahhabite.

Ce régime, moderne d’apparence, est en réalité fondamentalement tribal et obscurantiste. Pourquoi si peu d’informations sur sa vraie nature ?

Au risque de radoter, il faut que le public sache enfin que le Qatar est le champion du monde du double standard : celui du mensonge et de la dissimulation comme philosophie politique. Par exemple, des avions partent de Doha pour bombarder les taliban en Afghanistan alors que ces mêmes guerriers religieux ont un bureau de coordination installé à Doha, à quelques kilomètres de la base d’où décollent les chasseurs partis pour les tuer. Il en va ainsi dans tous les domaines, et c’est le cas de la politique intérieure de ce petit pays.

Regardons ce qui se passe dans ce coin de désert. Les libertés y sont absentes, on y pratique les châtiments corporels, la lettre de cachet, c’est-à-dire l’incarcération sans motif, est une pratique courante. Le vote n’existe que pour nommer une partie des conseillers municipaux, à ceci près que les associations et partis politiques sont interdits, tout comme la presse indépendante… Une Constitution qui a été élaborée par l’émir et son clan n’est même pas appliquée dans tous ses articles. Le million et demi de travailleurs étrangers engagés au Qatar s’échinent sous le régime de ce que des associations des droits de l’homme qualifient « d’esclavage ». Ces malheureux, privés de leurs passeports et payés une misère, survivent dans les camps détestables sans avoir le droit de quitter le pays. Nombre d’entre eux, accrochés au béton des tours qu’ils construisent, meurent d’accidents cardiaques ou de chutes (plusieurs centaines de victimes par an).

La « justice », à Doha, est directement rendue au palais de l’émir, par l’intermédiaire de juges qui le plus souvent sont des magistrats mercenaires venus du Soudan. Ce sont eux qui ont condamné le poète Al-Ajami à la prison à perpétuité parce qu’il a publié sur Internet une plaisanterie sur Al-Thani ! Observons une indignation à deux vitesses : parce que cet homme de plume n’est pas Soljenitsyne, personne n’a songé à défiler dans Paris pour défendre ce martyr de la liberté. Une anecdote : cette année, parce que son enseignement n’était pas « islamique », un lycée français de Doha a tout simplement été retiré de la liste des institutions gérées par Paris.

Arrêtons là car la situation du droit au Qatar est un attentat permanent aux libertés.

Pourtant, et l’on retombe sur le fameux paradoxe, Doha n’hésite pas, hors de son territoire, à prêcher la démocratie. Mieux, chaque année un forum se tient sur ce thème dans la capitale. Son titre, « New or restaured democracy » alors qu’au Qatar il n’existe de démocratie ni « new » ni « restaured »… Selon le classement de The Economist, justement en matière de démocratie, le Qatar est 136e sur 157e États, classé derrière le Bélarusse. Bizarrement, alors que toutes les bonnes âmes fuient le dictateur moustachu Loukachenko, personne n’éprouve honte ou colère à serrer la main d’Al-Thani. Et le Qatar, qui est aussi un enfer, n’empêche pas de grands défenseurs des droits de l’homme, notamment français, de venir bronzer, invités par Doha, de Ségolène Royal à Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, de Dominique de Villepin à Bertrand Delanoë.

Comment un pays qui est par essence antidémocratique se présente-t-il comme le promoteur des printemps arabes et de la liberté d’expression ?

Au regard des « printemps arabes », où le Qatar joue un rôle essentiel, il faut observer deux phases. Dans un premier temps, Doha hurle avec les peuples justement révoltés. On parle alors de « démocratie et de liberté ». Les dictateurs mis à terre, le relais est pris par les Frères musulmans, qui sont les vrais alliés de Doha. Et on oublie les slogans d’hier. Comme on le dit dans les grandes surfaces, « liberté et démocratie » n’étaient que des produits d’appel, rien que de la « com ».

Si l’implication du Qatar dans les « printemps » est apparue comme une surprise, c’est que la stratégie de Doha a été discrète. Depuis des années l’émirat entretient des relations très étroites avec des militants islamistes pourchassés par les potentats arabes, mais aussi avec des groupes de jeunes blogueurs et internautes auxquels il a offert des stages de « révolte par le Net ». La politique de l’émir était un fusil à deux coups. D’abord on a envoyé au « front » la jeunesse avec son Facebook et ses blogueurs, mains nues face aux fusils des policiers et militaires. Ceux-ci défaits, le terrain déblayé, l’heure est venue de mettre en poste ces islamistes tenus bien au chaud en réserve, héros sacralisés, magnifiés en sagas par Al-Jazeera.

Comment expliquez-vous l’implication directe du Qatar d’abord en Tunisie et en Libye, et actuellement en Égypte, dans le Sahel et en Syrie ?

En Libye, nous le montrons dans notre livre, l’objectif était à la fois de restaurer le royaume islamiste d’Idriss tout essayant de prendre le contrôle de 165 milliards, le montant des économies dissimulées par Kadhafi. Dans le cas de la Tunisie et de l’Égypte, il s’agit de l’application d’une stratégie froide du type « redessinons le Moyen-Orient », digne des « néocons » américains. Mais, une fois encore, ce n’est pas le seul Qatar qui a fait tomber Ben Ali et Moubarak ; leur chute a d’abord été le résultat de leur corruption et de leur politique tyrannique et aveugle.

Au Sahel, les missionnaires qataris sont en place depuis cinq ans. Réseaux de mosquées, application habile de la zaqat, la charité selon l’islam, le Qatar s’est taillé, du Niger au Sénégal, un territoire d’obligés suspendus aux mamelles dorées de Doha. Plus que cela, dans ce Niger comme dans d’autres pays pauvres de la planète le Qatar a acheté des centaines de milliers d’hectares transformant ainsi des malheureux affamés en « paysans sans terre ». À la fin de 2012, quand les djihadistes ont pris le contrôle du Nord-Mali, on a noté que des membres du Croissant-Rouge qatari sont alors venus à Gao prêter une main charitable aux terribles assassins du Mujao…

La Syrie n’est qu’une extension du domaine de la lutte avec, en plus, une surenchère : se montrer à la hauteur de la concurrence de l’ennemi saoudien dans son aide au djihad. Ici, on a du mal à lire clairement le dessein politique des deux meilleurs amis du Qatar, les États-Unis et Israël, puisque Doha semble jouer avec le feu de l’islamisme radical…

Le Fatah accuse le Qatar de semer la zizanie et la division entre les Palestiniens en soutenant à fond le Hamas, qui appartient à la nébuleuse des Frères musulmans. Pour beaucoup d’observateurs, cette stratégie ne profite qu’à Israël. Partagez-vous cette analyse ?

Quand on veut évoquer la politique du Qatar face aux Palestiniens, il faut s’en tenir à des images. Tzipi Livni, qui fut avec Ehud Barak la cheville ouvrière, en 2009, de l’opération Plomb durci sur Gaza – 1 500 morts – fait régulièrement ses courses dans les malls de Doha. Elle profite du voyage pour dire un petit bonjour à l’émir. Un souverain qui, lors d’une visite discrète, s’est rendu à Jérusalem pour y visiter la dame Livni… Souvenons-nous du pacte signé d’un côté par HBJ et le souverain Al-Thani et de l’autre les États-Unis : la priorité est d’assister la politique d’Israël. Quand le « roi » de Doha débarque à Gaza en promettant des millions, c’est un moyen d’enferrer le Hamas dans le clan des Frères musulmans pour mieux casser l’unité palestinienne. C’est une politique pitoyable. Désormais, Mechaal, réélu patron du Hamas, vit à Doha dans le creux de la main de l’émir. Le rêve de ce dernier – le Hamas ayant abandonné toute idée de lutte – est de placer Mechaal à la tête d’une Palestine qui se situerait en Jordanie, le roi Abdallah étant déboulonné. Israël pourrait alors s’étendre en Cisjordanie. Intéressante politique-fiction.

Le Qatar a-t-il « acheté » l’organisation de la Coupe du monde football en 2022 ?

Un grand et très vieil ami du Qatar m’a dit : « Le drame avec eux, c’est qu’ils s’arrangent toujours pour que l’on dise “cette fois encore, ils ont payé !” » Bien sûr, il y a des soupçons. Remarquons que les fédérations sportives sont si sensibles à la corruption que, avec de l’argent, acheter une compétition est possible. On a connu cela avec des jeux Olympiques étrangement attribués à des outsiders…

Dans le conflit frontalier entre le Qatar et le Bahreïn, vous révélez que l’un des juges de la Cour internationale de justice de La Haye aurait été acheté par le Qatar. L’affaire peut-elle être rejugée à la lumière de ces révélations ?

Un livre – sérieux celui-là – récemment publié sur le Qatar évoque une manipulation possible lors du jugement arbitral qui a tranché le conflit frontalier entre le Qatar et Bahreïn. Les enjeux sont énormes puisque, sous la mer et les îlots, se trouve du gaz. Un expert m’a déclaré que cette révélation pouvait être utilisée pour rouvrir le dossier devant la Cour de La Haye…

Les liaisons dangereuses et troubles entre la France de Sarkozy et le Qatar se poursuivent avec la France de Hollande. Comment expliquez-vous cette continuité ?

Parler du Qatar, c’est parler de Sarkozy, et inversement. De 2007 à 2012, les diplomates et espions français en sont témoins, c’est l’émir qui a réglé la « politique arabe » de la France. Il est amusant de savoir aujourd’hui que Bachar al-Assad a été l’homme qui a introduit la « sarkozie » auprès de celui qui était alors son meilleur ami, l’émir du Qatar. Il n’y a pas de bonne comédie sans traîtres. Kadhafi était, lui aussi, un grand ami d’Al-Thani et c’est l’émir qui a facilité l’amusant séjour du colonel et de sa tente à Paris. Sans évoquer les affaires incidentes, comme l’épopée de la libération des infirmières bulgares. La relation entre le Qatar et Sarkozy a toujours été sous-tendue par des perspectives financières. Aujourd’hui Doha promet d’investir 500 millions de dollars dans le fonds d’investissement que doit lancer l’ancien président français à Londres. Échange de bons procédés, ce dernier fait de la propagande ou de la médiation dans les aventures, notamment sportives, du Qatar.

François Hollande, par rapport au Qatar, s’est transformé en balancier. Un jour le Qatar est « un partenaire indispensable », qui a sauvé dans son fief de Tulle la fabrique de maroquinerie le Tanneur, le lendemain, il faut prendre garde de ses amis du djihad. Aucune politique n’est fermement dessinée et les diplomates du Quai-d’Orsay, nommés sous Sarkozy, continuent de jouer le jeu d’un Doha qui doit rester l’ami numéro 1. En période de crise, les milliards miroitants d’Al-Thani impliquent aussi une forme d’amitié au nom d’un slogan faux et ridicule qui veut que le Qatar « peut sauver l’économie française »… La réalité est plus plate : tous les investissements industriels de Doha en France sont des échecs… Reste le placement dans la pierre, vieux bas de laine de toutes les richesses. Notons là encore un pathétique grand écart : François Hollande a envoyé son ministre de la Défense faire la quête à Doha afin de compenser le coût de l’opération militaire française au Mali, conduite contre des djihadistes très bien vus par l’émir.

Majed Nehmé

http://www.afrique-asie.fr/menu/actualite/70-points-chauds/5510-le-qat...

* Le Vilain Petit Qatar – Cet ami qui nous veut du mal, Jacques-Marie Bourget et Nicolas Beau, Éd. Fayard, 300 p., 19 euros

Janvier 1978-janvier 1979. C’est au moment où elle se modernisait que la monarchie des Pahlavi s’est défaite dans la confusion. De là date l’essor de l’islamisme radical.

Janvier 1978-janvier 1979. C’est au moment où elle se modernisait que la monarchie des Pahlavi s’est défaite dans la confusion. De là date l’essor de l’islamisme radical.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Né en 1956, Pierre Le Vigan a grandi en proche banlieue de Paris. Il est urbaniste et a travaillé dans le domaine du logement social. Collaborateur de nombreuses revues depuis quelque 30 ans, il a abordé des sujets très divers, de la danse à l’idéologie des droits de l'homme, en tentant toujours de s'écarter des pensées préfabriquées. Attentif tant aux mouvements sociétaux ou psychiques qu'aux idées philosophiques, il a publié, notamment dans la revue Éléments, des articles nourris de ses lectures et de ses expériences et a été un des principaux collaborateurs de Flash Infos magazine.

Né en 1956, Pierre Le Vigan a grandi en proche banlieue de Paris. Il est urbaniste et a travaillé dans le domaine du logement social. Collaborateur de nombreuses revues depuis quelque 30 ans, il a abordé des sujets très divers, de la danse à l’idéologie des droits de l'homme, en tentant toujours de s'écarter des pensées préfabriquées. Attentif tant aux mouvements sociétaux ou psychiques qu'aux idées philosophiques, il a publié, notamment dans la revue Éléments, des articles nourris de ses lectures et de ses expériences et a été un des principaux collaborateurs de Flash Infos magazine.

When the ban on D.H. Lawrence’s controversial novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, was finally lifted in 1960 it was a watershed moment for censorship in Britain. But many assume it was only Lawrence’s novels that suffered at the hands of the censors.

When the ban on D.H. Lawrence’s controversial novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, was finally lifted in 1960 it was a watershed moment for censorship in Britain. But many assume it was only Lawrence’s novels that suffered at the hands of the censors.

Surfant sur la vague de l’opuscule philosophique mi-sérieux mi-drôle (ou plutôt : traitant sérieusement d’un sujet à première vue saugrenu) comme le célèbre On Bullshit de Harry G. Frankfurt ou le récent Art of Procrastination de John Perry, Aaron James nous livre avec Assholes: A Theory une analyse d’un phénomène somme toute assez peu étudié : le connard (ma traduction de l’anglais “assholes”, même si celui-ci se traduit plus littéralement par “trou-du-cul” - j’espère que ce choix apparaîtra comme justifié à la lecture de ce qui suit ).

Surfant sur la vague de l’opuscule philosophique mi-sérieux mi-drôle (ou plutôt : traitant sérieusement d’un sujet à première vue saugrenu) comme le célèbre On Bullshit de Harry G. Frankfurt ou le récent Art of Procrastination de John Perry, Aaron James nous livre avec Assholes: A Theory une analyse d’un phénomène somme toute assez peu étudié : le connard (ma traduction de l’anglais “assholes”, même si celui-ci se traduit plus littéralement par “trou-du-cul” - j’espère que ce choix apparaîtra comme justifié à la lecture de ce qui suit ).

Anarchie et Christianisme, deux gros mots pour certains, deux mots inconciliables pour d’autres. Jacques Ellul ne s’y trompe pas et l’écrit lui-même en introduction:

Anarchie et Christianisme, deux gros mots pour certains, deux mots inconciliables pour d’autres. Jacques Ellul ne s’y trompe pas et l’écrit lui-même en introduction:

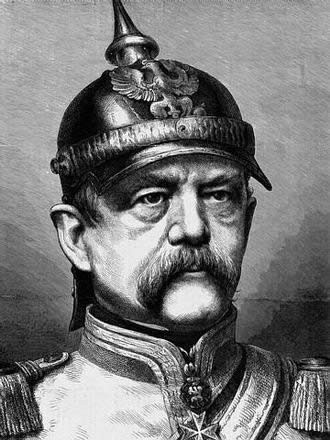

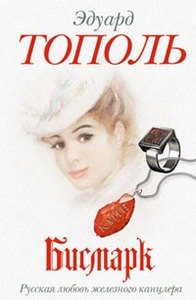

Am 6. August 1862 begegnet Otto von Bismarck in Biarritz dem russischen Fürsten Nikolai Orloff und dessen Gattin Katharina, geborene Trubezkaja. Der künftige „Eiserne Kanzler“ verknallt sich auf der Stelle in die 22-jährige Blondine. Er selbst ist bereits 47.

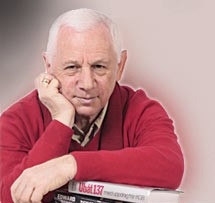

Am 6. August 1862 begegnet Otto von Bismarck in Biarritz dem russischen Fürsten Nikolai Orloff und dessen Gattin Katharina, geborene Trubezkaja. Der künftige „Eiserne Kanzler“ verknallt sich auf der Stelle in die 22-jährige Blondine. Er selbst ist bereits 47. Der heute 74-jährige Topol (Bild), der in den 70er-Jahren nach Europa und anschließend in die USA ausgewandert war, sich später aber auch in seiner postsowjetischen Heimat einen Namen machte, hat nämlich für Erotik einiges übrig. Mit seinen Büchern „Russland im Bett“, „Neues Russland im Bett“, „Die unschuldige Nastja, oder: Die ersten 100 Männer“, „Ich will dein Mädchen“ etc. sorgte er dafür, dass seine Leserschaft in jedem neuen Werk von ihm auf Prickelndes wartet. In „Bismarck“ kommt sie – wenn auch nicht mehr so ausgiebig wie früher – auf ihre Kosten. „Ich kann mich noch erinnern, wie das funktioniert“, gesteht der Autor schmunzelnd.

Der heute 74-jährige Topol (Bild), der in den 70er-Jahren nach Europa und anschließend in die USA ausgewandert war, sich später aber auch in seiner postsowjetischen Heimat einen Namen machte, hat nämlich für Erotik einiges übrig. Mit seinen Büchern „Russland im Bett“, „Neues Russland im Bett“, „Die unschuldige Nastja, oder: Die ersten 100 Männer“, „Ich will dein Mädchen“ etc. sorgte er dafür, dass seine Leserschaft in jedem neuen Werk von ihm auf Prickelndes wartet. In „Bismarck“ kommt sie – wenn auch nicht mehr so ausgiebig wie früher – auf ihre Kosten. „Ich kann mich noch erinnern, wie das funktioniert“, gesteht der Autor schmunzelnd.  Katharina stirbt aber noch viel früher als er mit 35. Als Bismarck das erfährt, verfällt er für sieben Jahre in Depression. Inzwischen hat er als Politiker ziemlich alles erreicht, die Liebe seines Lebens ist aber nicht mehr auf dieser Welt. Wozu dann das Ganze?

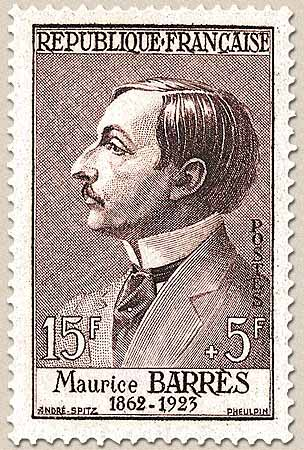

Katharina stirbt aber noch viel früher als er mit 35. Als Bismarck das erfährt, verfällt er für sieben Jahre in Depression. Inzwischen hat er als Politiker ziemlich alles erreicht, die Liebe seines Lebens ist aber nicht mehr auf dieser Welt. Wozu dann das Ganze?  Longtemps principale figure de la République des Lettres et modèle de plusieurs générations d’écrivains, Maurice Barrès est aujourd’hui bien oublié tant des institutions que du public. 2012 marquait les cent cinquante ans de sa naissance, le 20 août 1862. Cet événement n’a guère mobilisé les milieux officiels plus inspirés par les symptômes morbides d’une inculture abjecte. Le rattrapage demeure toutefois possible puisque 2013 commémorera la neuvième décennie de sa disparition brutale, le 4 décembre 1923 à 61 ans, à la suite d’une crise cardiaque. belle session de rattrapage pour redécouvrir la vie, l’œuvre et les idées de ce député-académicien.

Longtemps principale figure de la République des Lettres et modèle de plusieurs générations d’écrivains, Maurice Barrès est aujourd’hui bien oublié tant des institutions que du public. 2012 marquait les cent cinquante ans de sa naissance, le 20 août 1862. Cet événement n’a guère mobilisé les milieux officiels plus inspirés par les symptômes morbides d’une inculture abjecte. Le rattrapage demeure toutefois possible puisque 2013 commémorera la neuvième décennie de sa disparition brutale, le 4 décembre 1923 à 61 ans, à la suite d’une crise cardiaque. belle session de rattrapage pour redécouvrir la vie, l’œuvre et les idées de ce député-académicien. Par delà ce talent polémique, Jean-Pierre Colin perçoit dans l’œuvre de Barrès politique la préfiguration des idées gaullistes de la V

Par delà ce talent polémique, Jean-Pierre Colin perçoit dans l’œuvre de Barrès politique la préfiguration des idées gaullistes de la V

Het jaar van het gevaarlijke dromen bestaat grofweg uit twee delen. Eerst maakt Zizek een aantal opmerkingen over de dynamiek van het kapitalisme, waardoor deze ideologie er steeds weer in slaagt zich aan de veranderende omstandigheden aan te passen zonder evenwel haar principes van uitbuiting en onrechtvaardigheid op te geven.

Het jaar van het gevaarlijke dromen bestaat grofweg uit twee delen. Eerst maakt Zizek een aantal opmerkingen over de dynamiek van het kapitalisme, waardoor deze ideologie er steeds weer in slaagt zich aan de veranderende omstandigheden aan te passen zonder evenwel haar principes van uitbuiting en onrechtvaardigheid op te geven. Canale Mussolini ist ein Epochen- und Familienroman, der – autobiographisch angereichert – davon erzählt, wie aus den Männern und Frauen einer norditalienischen, mittellosen Bauernsippe handfeste Faschisten werden: un-ideologische zwar, aber ist das nicht immer so, wenn es um die Masse unterhalb der weltanschaulich gefestigten Revolutionäre geht?

Canale Mussolini ist ein Epochen- und Familienroman, der – autobiographisch angereichert – davon erzählt, wie aus den Männern und Frauen einer norditalienischen, mittellosen Bauernsippe handfeste Faschisten werden: un-ideologische zwar, aber ist das nicht immer so, wenn es um die Masse unterhalb der weltanschaulich gefestigten Revolutionäre geht?

![[Lecture] Contre l’Europe de Bruxelles – Fonder un Etat européen, par Gérard Dussouy](http://fr.novopress.info/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/dussouy_modifie-1.jpg)