Lafcadio Hearn and Japanese Buddhism

by Kenneth Rexroth

Ex: http://www.bobsecrets.org

“In attempting a book upon a country so well trodden as Japan, I could not hope — nor would I consider it prudent attempting — to discover totally new things, but only to consider things in a totally new way. . . . The studied aim would be to create, in the minds of the readers, a vivid impression of living in Japan — not simply as an observer but as one taking part in the daily existence of the common people, and thinking with their thoughts.”

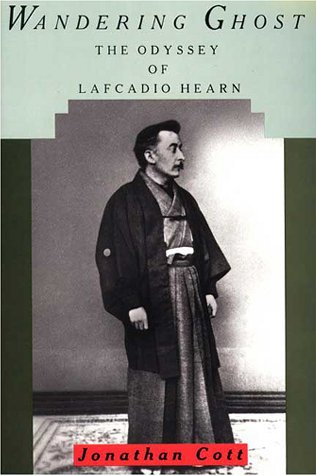

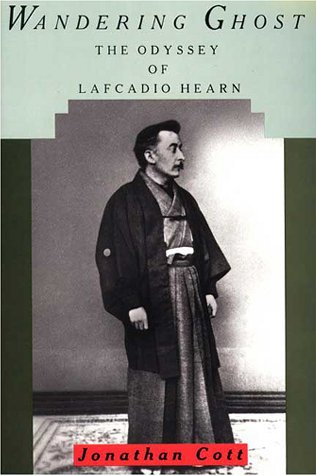

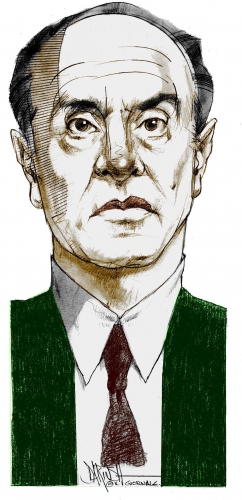

So Lafcadio Hearn wrote to Harper’s Magazine in 1889 just prior to leaving for Japan. He kept this promise so well that by his death in 1904 (as Koizumi Yakumo, a Japanese citizen) he was acclaimed as one of America’s greatest prose stylists and the most influential authority of his generation on Japanese culture. That reputation has dimmed somewhat since then. Changing tastes in literary styles have made Hearn’s work seem old-fashioned, and Japan’s astonishing absorption of Western industrial methods and industrial values have made him for a time irrelevant.

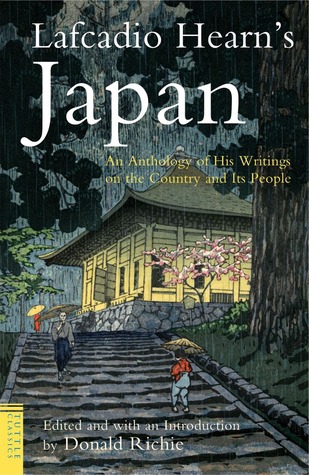

Now interest in ancient Japanese culture and religion is again on the rise, and Hearn’s work, devoted as it is to what he perceived as lasting and essential in Japanese life, is experiencing a revival. From his essays and stories emerges a sensitive and durable vision of how Buddhism was and still is lived in Japan — the ancient Buddhist traditions, rituals, myths, and stories that are still preserved, and their effects upon the beliefs and daily life of ordinary Japanese people.

Lafcadio Hearn was born on the Ionian island of Santa Maura in either June or August 1850 and died in Okubo, Japan in 1904. His father was an Irish surgeon major stationed in Greece and his mother a Greek woman, famous for her beauty. It was she who named him Lafcadio, after Leudakia, the ancient name of Santa Maura, one of the islands connected with the legend of Sappho. In a relatively short lifespan of fifty-four years he managed to live several different literary lives.

Lafcadio Hearn was born on the Ionian island of Santa Maura in either June or August 1850 and died in Okubo, Japan in 1904. His father was an Irish surgeon major stationed in Greece and his mother a Greek woman, famous for her beauty. It was she who named him Lafcadio, after Leudakia, the ancient name of Santa Maura, one of the islands connected with the legend of Sappho. In a relatively short lifespan of fifty-four years he managed to live several different literary lives.

From Greece, at two years of age, he went to Ireland, where his father soon obtained a dissolution of marriage from his mother. She was sent back to Greece. His father quickly remarried and went off to India. That is the last Hearn saw of either of them.

His formal education consisted of one year at a Catholic school in France (he just missed Guy de Maupassant, who entered the school a year later and who later became one of his literary idols), and four years at St. Cuthbert’s in England, where he lost one eye in a playing field accident. The disfigurement (the blinded eye was whitened, the good eye protruded from overuse) helped to make Hearn a painfully sensitive and shy person for the rest of his life. At seventeen, as a result of financial and personal misfortunes in the family, he was withdrawn from school. A year later, his uncle gave him passage money to America and advised him to look up a distant relative in Cincinnati. From then on Hearn had to make his own way in the world.

After a year of homelessness and near-starvation in Cincinnati, Hearn got a job as an editor for a trade journal and then as a reporter for the daily Enquirer. His assignment was the night watch, his specialty sensational crimes and gory murders. He had good contacts in the coroner’s office, and his small, shy figure and one-eyed face did not arouse suspicion among the street people. His stories, with their ghastly descriptions, were frequent features that titillated the Enquirer’s readers. The editor reluctantly fired Hearn when rumors began to circulate that he was living with a mulatto woman whom he insisted he had married. (He had, but Ohio law refused to recognize mixed marriages.)

Another daily newspaper, the Cincinnati Commercial, hired him immediately. Here Hearn was allowed to contribute brief scholarly essays, local color stories, and prose poems, as well as the sensational stories that had got him his reputation. But he was restless with this kind of newspaper work, and sick of Cincinnati. In 1877 he quit the Commercial and left for New Orleans.

There he found work as a reporter for the struggling Item, though what he reported was anything he fancied, most often sketches of Creole and Cajun life. His Item essays were eccentric, flamboyant, and often self-indulgent, but they caught the eye of New Orleans’ literary establishment. When the city’s two largest newspapers merged to form the Times-Democrat, Hearn was invited to be its literary editor. He translated and adapted French stories (principally Gautier, Maupassant, Flaubert, and Loti — none of whom yet had a reputation in America); he wrote original stories in the lavish prose style he was perfecting at that time; and he collected local legends and factual narratives. His subjects ranged from Buddhism to Russian literature, from popularizations of science to European anti-Semitism. Altogether he offered the people of New Orleans such unpredictable and exotic fare that his reputation soon spread throughout the South. By this time he had become a disciple of his contemporary, Robert Louis Stevenson (or perhaps vice versa: they developed similarly mellifluous prose styles and shared a fondness for fantastic and exotic subject matter). Hearn was enormously popular. From these years in New Orleans date Stray Leaves from Strange Literatures, 1884, Some Chinese Ghosts, 1887, and a novel, Chita, 1889.

In 1887 Hearn went to the West Indies for Harper’s Magazine and produced Two Years in the French West Indies, 1890, and his last novel, Youma, 1890, an unprecedented story about a slave rebellion.

In 1890 he went to Japan for Harper’s but soon became a school teacher in Izumo, in a northern region then little influenced by Westernization. There he married Koizumi Setsuko, the daughter of a Samurai. In 1891 he moved to Kumamoto Government College.

Hearn was by now well known in America as an impressionistic prose painter of odd peoples and places. For this he was at first celebrated and later deprecated. Yet much of his Japanese work is of an entirely different quality and intention. He wrote to his friend Chamberlin in 1893, “After for years studying poetical prose, I am forced now to study simplicity. After attempting my utmost at ornamentation, I am converted by my own mistakes. The great point is to touch with simple words.” The Atlantic Monthly printed his articles on Japan and syndicated them to a number of newspapers. They were enormously popular when they appeared and became even more so when they were published in two volumes as Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan, 1894.

In 1895 Hearn became a Japanese citizen and took the name of Koizumi Yakumo. In 1896 he became professor of literature at Tokyo Imperial University, a most prestigious academic position in the most prestigious school in Japan. From then until his death he produced his finest books: Exotics and Retrospectives, 1898, In Ghostly Japan, 1899, Shadowings, 1900, A Japanese Miscellany, 1901, Kwaidan, 1904, Japan, An Attempt at Interpretation, 1904. These were translated into Japanese and became at least as popular in Japan as they did in America.

During the last two years of his life, failing health forced Hearn to give up his position at Tokyo Imperial University. On September 26, 1904, he died of heart failure. He had instructed his eldest son to put his ashes in an ordinary jar and to bury it on a forested hillside. Instead, he was given a Buddhist funeral with full ceremony, and his grave is to this day a place of pilgrimage perpetually decorated with flowers.

At the turn of the century, Hearn was considered one of the finest, if not the finest, of American prose stylists. He was certainly one of the masters of the Stevensonian style. As literary tastes changed, he was thought of more as a writer of pretty but dated essays about Japanese tame crickets and of sentimental ghost stories. After his death, his literary reputation was further damaged by the publication of several collections of his florid earlier work. His all-but-final reputation was as a lush, frothy stylist whose essays and stories were about as important as the pressed flowers likely to be found between their pages.

In fact, Hearn’s Japanese writings demonstrate economy, concentration, and great control of language, with little stylistic exhibitionism. Their attitude of uncritical appreciation for the exotic and the mysterious is as unmistakably nineteenth century as the fine prose idiom with which it is consistent.

In spite of the incredible changes that have taken place in Japan since Hearn’s death in 1904, as an informant of Japanese life, literature, and religion he is still amazingly reliable, because beneath the effects of industrialization, war, population explosion, and prosperity much of Japanese life remains unchanged. For Hearn the old Japan — the art, traditions, and myths that had persisted for centuries — was the only Japan worth paying attention to. Two world wars and Japan’s astonishing emergence as a modern nation temporarily extinguished the credibility of Hearn’s vision of traditional Japanese culture. But both in the West and in Japan interest in the old forms of Japanese culture is increasing. In Tokyo there are still thousands of people living the old life by the traditional values alongside the most extreme effects of Westernization. Pet crickets, for example, still command high prices, and more people apply their new prosperity to learning tea ceremony, calligraphy, flower arrangement and sumi-e painting than ever before. Ghost stories like those told by Hearn are popular on television; three of his own were recently combined to make a successful movie that preserves his title, Kwaidan.

In spite of the incredible changes that have taken place in Japan since Hearn’s death in 1904, as an informant of Japanese life, literature, and religion he is still amazingly reliable, because beneath the effects of industrialization, war, population explosion, and prosperity much of Japanese life remains unchanged. For Hearn the old Japan — the art, traditions, and myths that had persisted for centuries — was the only Japan worth paying attention to. Two world wars and Japan’s astonishing emergence as a modern nation temporarily extinguished the credibility of Hearn’s vision of traditional Japanese culture. But both in the West and in Japan interest in the old forms of Japanese culture is increasing. In Tokyo there are still thousands of people living the old life by the traditional values alongside the most extreme effects of Westernization. Pet crickets, for example, still command high prices, and more people apply their new prosperity to learning tea ceremony, calligraphy, flower arrangement and sumi-e painting than ever before. Ghost stories like those told by Hearn are popular on television; three of his own were recently combined to make a successful movie that preserves his title, Kwaidan.

One of the foreigners’ (and Westernized, secularized Japanese intellectuals’) myths of Japan is that the Japanese are a fundamentally secular, irreligious people. Nothing could be less true. The great temples swarm with pilgrims and are packed during their major festivals. Buddhism is more popular than ever. Shinto and Shingon and Tendai Buddhism perpetuate rites that began long before the dawn of Japanese history.

Although it is no longer true, if it ever was, that Japan is totally “Westernized,” it is certainly the most Post-Modern of all the major nations today. With an economy which has ceased to be based on the mechanical, industrial methods of the nineteenth century (really because the old industrial capital structure was destroyed and everything dates from 1946), Japan has moved into the electronic age more completely than any other nation. Yet any Japanese who wishes can still make immediate contact with the Stone Age.

Hearn foresaw the industrialization of Japan and her development of imperialist ambitions. As much as possible he avoided the atmosphere of modernization, spending his summers away from Tokyo at Yaizu, a small fishing village where today there is a Hearn monument. His happiest period in Japan was the early years he spent as a country school teacher in Matsue on the southwest coast. His house and garden there are still preserved, and a Hearn museum is located next door. The essay “In a Japanese Garden” in his book Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan describes his home and Matsue.

Beginning with Charles Eliot’s Japanese Buddhism, there has grown up an immense bibliography of Buddhological works in Western languages. Since World War II, there is an ever greater store in the United States of books on Zen, which has become a popular form of Existentialism. There is no interpreter of Japanese Buddhism quite like Hearn, but he is not a Buddhologist. Far from it. Hearn was not a scholar, nor was he in the Western sense a religious believer. What distinguishes him is an emotional identification with the Buddhist way of life and with Buddhist cults. Hearn is as good as anyone at providing an elementary grounding in Buddhist doctrine. But what he does incomparably is to give his reader a feeling for how Buddhism is lived in Japan, its persistent influence upon folklore, burial customs, children’s riddles, toys for sale in the marketplace, and even upon the farmer’s ruminations in the field. For Hearn, Buddhism is a way of life, and he is interested in the effects of its doctrine upon the daily actions and common beliefs of ordinary people. Like the Japanese themselves, he thinks of religion as something one does, not merely as something one believes, unlike the orthodox Christian whose Athanasian Creed declares: “Whosoever would be saved, it is necessary before all things that he believe . . .”

One of the things Hearn admires about Buddhism is its adaptability to the spiritual and historic needs of a people. If they need a pantheon of gods, Buddhism makes room for them. If they need to fix upon a savior, Buddhism provides one. But the Buddhist elite, the more learned monks, never lose sight of the true doctrine. I will never forget a symposium in which I once took part along with a number of Buddhist clergy. A Westerner asked the leading Shinshu abbot, “Do you really believe in the existence of supernatural beings like Amida and Kannon, and in a life after death in the True Land Paradise of Amida?” The abbot answered very quietly, “These are conceptual entities.” In fact the Diamond and Womb Mandalas with their hundreds of figures (sometimes represented by quasi-Sanskrit letters) are tools for meditation. The monk moves from the guardian gods at the outer edge, in to the central Buddha — the Vairocana — and at last beyond him to the Adi Buddha — the Pure, unqualified Void.

Yet, popular rather than “higher” Buddhism is Hearn’s main subject, and he always is careful to distinguish between the metaphysically complex Buddhism of the educated monks and the simpler, more colorful Buddhism of the ordinary people.

The only peculiarity in Hearn’s Buddhism is his habit of equating it with the philosophy of Herbert Spencer, now so out of date. However, this presents few difficulties for the modern reader, as his Spencerianism can be said to resemble Buddhism more than his Buddhism resembles Herbert Spencer. Also, it is not Spencer’s Darwinism, “red in tooth and claw,” but Spencer’s metaphysical and spiritual speculations that have influenced Hearn’s interpretation of Buddhism. We must not forget that Teilhard de Chardin, who certainly is not out of date, is, in the philosophical sense, only Herbert Spencer sprinkled with holy water. Philosophies and theologies come and go, but the group experience of transcendence is embedded in human nature, and when it is abandoned, theology, philosophy, and eventually culture, perish.

It is difficult to think of a better guide to Japanese Buddhism for the completely uninformed than Hearn, though there are others who may be his equals. Certainly the popularizers of Zen are not. Zen, after all, is a very special sect, in many ways more Vedantist or Taoist than Buddhist. And of course as the religion of the Japanese officer caste and of the great rich it plays in Japan a decidedly reactionary role. Hearn’s Buddhism is far less specialized than Zen. It is the Buddhism of the ordinary Japanese Buddhist of whatever sect.

The first distinction to be made in any consideration of Buddhism itself is that Christianity is the only major religion whose adherents live lives and hold beliefs diametrically opposed to those of its founder. Nothing could be less like the life of Jesus than that of the typical Christian, clerical or lay. Imagine thirteen men with long beards, matted hair, and probably lice, in ragged clothes and dusty bare feet, taking over the high altar at St. Peter’s in Rome or the pulpit of a fashionable Fifth Avenue sanctuary. The Apostolic life survives in only odd branches of Christianity: the Hutterites, some Quakers, even Jehovah’s Witnesses, but not, as everyone knows, in official and orthodox denominations. Catholicism carefully quarantines such people in monasteries and nunneries where a life patterned on that of the historic Jesus is not wholly impossible to achieve. The opposite is true of Buddhism. No matter how far the sect — Lamaism, Zen, or Shingon — may have moved from the Buddhologically postulated original Buddhist Order, all sects of Buddhism are pervaded by the personality of the historic Siddhartha Gautama.

The historicity of almost all the details of what are generally considered to be the earliest Buddhist documents is subject to dispute and in many instances is improbable. The earliest surviving Life of Buddha was written hundreds of years after his death. The prevailing form of Buddhism in Japan, Mahayana, seems to Westerners more like a group of competing, highly speculative philosophies than a religion. The complete collection of Hinayana, Mahayana and Tantric Buddhist texts makes up a very large library. In addition, there are many thousands of pages of noncanonical commentary and speculation. Yet out of it all emerges, with extraordinary clarity, a man, a personality, a way of life and a basic moral code.

Buddha was born in Kapilavastu, now Rummimdei, Nepal, sometime around 563 BC and died about 483 BC in Kusimara, now Kasia, India. His personal name was Siddhartha Gautama. Buddha, The Enlightened One, is a title, not a name, as is Shakyamuni, the saint of the Shaka clan. In Japan, the historic Buddha is commonly known as Shakya. He was a member of the Kshatriya warrior caste, the son of the ruler of a small principality.

Buddha was born in Kapilavastu, now Rummimdei, Nepal, sometime around 563 BC and died about 483 BC in Kusimara, now Kasia, India. His personal name was Siddhartha Gautama. Buddha, The Enlightened One, is a title, not a name, as is Shakyamuni, the saint of the Shaka clan. In Japan, the historic Buddha is commonly known as Shakya. He was a member of the Kshatriya warrior caste, the son of the ruler of a small principality.

For six years Buddha lived with five other ascetics in a grove at Uruvela practicing the most extreme forms of self-mortification and the most advanced techniques of Hatha Yoga, until he almost died of starvation. He gave up ascetic life, left his companions, and traveled on. At Bodh Gaya he seated himself under a Bo tree (ficus religiosa) and resolved not to get up until he had achieved true enlightenment. Maya, the personification of the world’s illusion, with his daughters and all the attendant incarnate sins and illusions, attacked him without success. Gautama Siddhartha achieved final illumination, entered Nirvana and arose a Buddha: an Enlightened One. He returned to his five companions at Uruvela and preached to them the Middle Way between self-indulgence and extreme asceticism. They were shocked and repudiated him, but after he had preached to them the Noble Eightfold Way and the Four Truths, they became the first Buddhist monks.

The first Truth is the Truth of suffering: birth is pain, old age is pain, sickness is pain, death is pain, the endless round of rebirths is pain, the five aggregates of grasping are pain. The second Truth is the cause of pain: the craving that holds the human being to endless rebirth, the craving of the passions, the craving for continued existence, the craving for nonexistence. The third Noble Truth is the ending of pain: the extirpation of craving. The fourth Noble Truth is the means of arriving at the cessation of pain: the Noble Eightfold Path, which is right views, right intentions, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, right concentration (or contemplation). This doctrine is the essence of Buddhism, common to all of its otherwise divergent sects. It is always there, underlying the most extreme forms of Tantrism or Amidism. It produces in the personality of the devout Buddhist what the Japanese would call the iro, the essential color of the Buddha-life.

As Hinduism was taking form in the Upanishads, it began to teach the doctrine of the identity of the individual self, the Atman, and of the universal self, Brahman as Atman. Buddha attacked the Atman doctrine head-on, denying the existence of the individual or absolute self. He taught that the self is simply a bundle of skandhas, the five aggregates of grasping: body, feeling, perception, mental elements, and consciousness. The skandhas that comprise the self are momentary and illusory in the flux of Being — but they do cause and accumulate karma, the moral residue of their acts in this life and in past lives. It is karma which holds the aggregates embedded in the bonds of craving and consequence until the skandhas disintegrate in the face of Ultimate Enlightenment. In the most philosophical teaching of Buddhism, it is the karma and the skandhas which reincarnate. The individual consciousness or soul, as we think of it, disappears. But the universal belief in the reincarnation of the individual person has always overridden this notion. The ordinary Buddhist in fact believes in the rebirth of the self, the atman.

It is these doctrines which distinguish Buddhism. Many ideas which we think of as especially Buddhist are actually shared by Hinduism, by Jainism, and in fact by many completely secular modern Indians — transmigration, Yogic practices (some modern Buddhologists have held that Buddhism is only a special form of Yoga, anticipating its final synthesis in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali). Vedic gods appear at all the crucial moments in Buddha’s life, from his conception to his entry into final Nirvana. Some time after its inception, Buddhism developed the practice of bhakti, personal devotion to a Savior, parallel to that of Hinduism. But always what distinguishes Buddhism is the Buddha Way, the Buddha-life, the all-pervasive personality of its founder, as the personality of Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita does not.

The fifty years after his illumination Buddha spent traveling and preaching, usually with a large entourage of monks. In his eightieth year he stopped at the home of Cunda the smith, where he and his followers were given a meal of something to do with pigs. The language is obscure — pork, pigs’ food, or something that had been trampled by pigs. Buddha became ill and later stopped in the gardens of Ambhapala, where he announced to his monks that he was about to enter Parinirvana, the final bliss. He lay down under the flowering trees and died, mourned by all creation, monks, laymen, gods, and the lowest animals. His last words were, “The combinations of the world are unstable by nature. Monks, strive without ceasing.”

This is the account preserved by the Pali texts, the sacred books of the Theravada Buddhists, of the religion of Ceylon, Burma, and the countries of the Indo-Chinese peninsula. Pali is a dialect of a small principality in Northern India, now forgotten in its homeland. The Pali texts are earlier than all but fragments of Buddhist Sanskrit documents, but this does not necessarily mean that the Hinayana (“The Lesser Vehicle”) Buddhism which they embody is the most primitive form of the religion. Theirs is simply the religion of the Theravada, “The religion of the Elders,” one of the early sects. However, up until the reign of Ashoka, the saintly Buddhist emperor who ruled more of the Indian subcontinent than anyone before him, Buddhism seems to have been a more or less unified religion resembling the later Hinayana. From the reign of Ashoka to the beginning of the Christian era two currents in Buddhism began to draw more and more apart until Mahayana, “The Greater Vehicle,” became dominant in the North and in Java. All the forms of Japanese Buddhism with which Hearn came into contact are rooted in the Mahayana tradition.

The many Mahayana texts are differentiated from the postulated Buddha Word as it appears in Pali by several radically different, indeed contradictory, beliefs and practices. In Hinayana man achieves Nirvana, or advances towards it in a future life, solely by his own efforts to overcome the accumulated evil karma of thousands of incarnations. There is devotion to the Founder as the Leader of the Way, but no worship, because there is nothing to worship. The difference is the same as that which the Roman Catholic Church calls dulia, adoration of the saints, and latria, adoration of God. Mahayana introduced the idea of saviors, Bodhisattvas, who have achieved Buddhahood but who have taken a vow not to enter Nirvana until they can take all sentient creatures with them. As saviors they are worshipped with a kind of hyper-dulia, as is the Blessed Virgin in Roman Catholicism. Buddhism was influenced by the great wave of personal worship that swept through India, bhakti, the adoration of Krishna, the incarnation of Vishnu, or of Kali, the female embodiment of the power of Shiva. At least theoretically above the Bodhisattvas arose a pantheon of Buddhas of whom Vairocana was primary. Later, an Adi-Buddha was added above him. It is disputable if either properly can be called the Absolute. If there is any absolute in Buddhism, it is Nirvana, which in fact means the religious experience itself. From Vairocana emanate the four Dhyana Buddhas, the Buddhas of Contemplation, of whom Amida is the best known, and of whom the historic Shakyamuni is only one of four, although in his most transcendental form he can be equated with Vairocana or the Adi Buddha.

The story of the development of Mahayana as it spread from what is now Afghanistan and Russian Turkestan to Mongolia and Indonesia to Tibet, China and Japan, while it died out in India, would take many thousands of words to tell. There are traces of Buddhism in China two hundred years or more before the Christian era. Its official introduction is supposed to have occurred in the first century AD. From then until the Muslim conquest of India, Chinese pilgrims visited India and brought back caravan loads of statuaries and sutras (sacred texts) which were translated into Chinese.

The story of the development of Mahayana as it spread from what is now Afghanistan and Russian Turkestan to Mongolia and Indonesia to Tibet, China and Japan, while it died out in India, would take many thousands of words to tell. There are traces of Buddhism in China two hundred years or more before the Christian era. Its official introduction is supposed to have occurred in the first century AD. From then until the Muslim conquest of India, Chinese pilgrims visited India and brought back caravan loads of statuaries and sutras (sacred texts) which were translated into Chinese.

Indian missionaries emigrated to China and taught and translated. Buddhism was introduced into Korea in the fourth century and had thoroughly established itself in the three countries of the peninsula by the seventh. From there it passed to Japan in the sixth century.

The first missionaries converted the Soga Clan, which was then the power behind the Japanese throne. For the greater part of a century Buddhism was almost exclusively the religion of a faction of the nobility, and its fortune varied with the factional struggles of the court. In 593 AD Prince Shôtoku became the effective head of state. His knowledge of Buddhism and of the more profound meanings of Mahayana was extraordinary. He not only saved Buddhism from rapidly becoming a cult of magic and superstition, but like Ashoka in India before him, he went far to make it a religion of the people. He copied sutras in characters of gold on purple paper. He preached the doctrines of Mahayana to the common people as well as to the court. He established hundreds of monasteries, nunneries and temples. Not least, he promulgated a kind of charter which modern Japanese called The Seventeen Article Constitution, in which Buddhist ethics and, to a lesser degree, Confucianism were established as the moral foundations of Japan. To this day he is regarded by many as an avatar of Avalokiteshvara, Kuan Yin in Chinese and Kannon or Kwannon in Japanese — the so-called Goddess of Mercy and the most popular of all Bodhisattvas.

By the eighth century Buddhism had become Japan’s official state religion, a feat Hearn credits to Buddhism’s absorption and expansion of the older Shinto worship of many gods, ghosts, and goblins (the gods, Buddhas or Bodhisattvas, the ghosts beings in transit from one incarnation to another, and the goblins, gakis, beings suffering in a lower state of existence). By the thirteenth century most of the major forms of Japanese Buddhism — a religion quite distinct from Buddhism elsewhere in the world — had been established, though minor sects continued to proliferate.

Ten large sects dominate Japanese Buddhism. The oldest of these are Tendai and Shingon. First was Tendai, established by the monk Saichô in 804 on Mt. Hiei northeast of Kyoto (Heian kyo), facing the most inauspicious direction. Not long afterwards the monk Kukai returned from China and introduced Shingon, which became the Japanese form of Tantric Buddhism. In China, Tendai attempted a synthesis of the various schools and cults in the great complex of monasteries on Mt. T’ien Tai. The similar monastic city on Mt. Hiei sheltered a wide variety of cults, doctrines, and philosophies. Basically, however, Japanese Tendai modified what in India was known as “right-handed” Tantrism, which we see today in the Yellow Hat sect of Tibetan Lamaism in exile. All the great Buddhist sutras were studied, the doctrine of the Void, the doctrine of Mind Only, the vision of reality as the interpenetration of compound infinitives of Buddha natures of the Avatamsaka Sutra, and the complex panpsychism of the Lankavatara Sutra. Most popular, however, was the Lotus Sutra (Hokkekyo in Japanese), the Saddharma Pundarika Sutra, the only major Buddhist document a Japanese lay person is at all likely to have read. Tendai is a ceremonial religion, and only in recent years has it done much for the laity except to permit them to participate in pilgrimages and to watch public ceremonies.

Shingon is even more esoteric than Tendai and is in fact Japanese Lamaism. Its doctrines are occult, its mysteries are not divulged to the people, and many of its rites are kept secret. The worship of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas as sexual dualities or as terrifying wrathful figures is not as common in Japan as in Tibet, though in both cultures the emphasis on magic formulas, gestures, spells and special methods of inducing trance remains essential. It is not known how many Tantric shastras (scriptures secondary to sutras) survive and are studied in Shingon monasteries, but recent discoveries and paintings of this literature are read by the more learned Japanese monks. “Left-handed” Tantrism, with its cult of erotic mysticism, survives underground in Tachigawa Shingon.

The worship of Amida which began in India around the advent of the Christian era, almost certainly under the influence of Persian religion, effected a complete revolution in Japanese Buddhism when it was introduced in the ninth century. Originally sheltered within the Tendai sect, Amidism grew to be the most popular form of Buddhism in Japan — and the one with which Hearn was most familiar. Amida is the Buddha of Endless Light whose paradise, The Pure Land, is in the west. He has promised that any who believe in him and call on his name will be saved and at death will be reborn in his Pure Land. Buddha, of course, insisted that by oneself one is saved and thus achieves, not paradise, but Nirvana, which far transcends any imaginable paradise. Hearn, however, observed that few Japanese even knew of the concept of Nirvana. For them Amida’s Pure Land was the highest heaven imaginable. Buddha also forbade worship of himself or others and considered the gods inferior to human beings because they could not escape the round of rebirths and enter Nirvana. Amidism, as a gesture to orthodoxy, teaches that the older Buddhism is too hard for this corrupt age and that the Pure Land, unlike other paradises, provides a direct stepping stone to Nirvana. As the Amidist sects developed in Japan, the doctrine of salvation by faith became more and more extreme. At first, it was necessary to invoke the name of Amida many times a day and especially with one’s last words, but finally one had only to invoke it once in a lifetime. This was enough to erase the karma, the consequences, of a life of ignorance and sin.

The Japanese monk Nichiren, who played a role not unlike that of the Hebrew Prophets, taught that salvation could be won by reciting the words “Namu Myohorengekyo,” “Hail to the Lotus Sutra!” The Lotus Sutra is a sort of compendium of Mahayana Buddhism, lavishly embroidered with miraculous visions, with thousands upon thousands of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, gods, demigods and lesser supernatural beings. But its important chapter is the Kannon (Avalokiteshvara), which raises the Bodhisattva to a position similar to that of Amida, The Savior of the World, “He Who Hears The World’s Cry.” The earliest Kannon statues and paintings seem to have reached Japan from the oasis cities of Central Asia. Their peculiar sexlessness led the Japanese, as it did the Chinese, to think of the Bodhisattva as a woman. Not just Westerners, but most Japanese, refer to him as the Goddess of Mercy, and cheap modern statues which depict him holding a baby bear a striking resemblance to popular representations of the Virgin Mary.

The secret of the tremendous success of Amidism and Nichirenism is that they are congregational religions. The largest of all Buddhist sects, the Amidist Jodo-Shinshu, is in this sense much like a modern Christian denomination. But in other respects, and despite its tremendous pilgrimages, Buddhism seems inaccessible to the common Japanese. Very few people know anything about the profound and complex metaphysics of the Mahayana speculation. A surprising number do know the life of Buddha as it is told in Hinayana, which scarcely exists in Japan, and do try to model their lives on the Buddha-life — with remarkable success. But for most secular Japanese, a Buddhist monk is just a kind of undertaker, to be called upon only when somebody dies.

Zen Buddhism cultivated a special sensibility that many Japanese people think of as Japanese. The tea ceremony, sumi-e ink painting, the martial arts (archery, sword play, jiu-jitsu, judo, aikido, wrestling), flower arrangement, pottery, and haiku survive as creative expressions of the Zen sensibility in pursuit of perfection. But this sensibility has weakened in most modern Japanese.

Zen is often translated as Enlightenment (Ch’an or Dhyana), but it means something like illumination, specifically illumination achieved by systematic religious meditation of the kind we identify as yoga. It is supposed to have been introduced to China by a missionary Indian monk, Bodhidharma, probably in the sixth century. It spread to Japan in the thirteenth as the long civil wars were beginning, became popular with the military castes and the great rich, and for a long time dominated the intellectual and artistic life of the country. Zen owed its powerful influence to the fact that it began as a revolt against the Buddhist cults of its time and reverted to what the nineteenth century was to call “Primitive” Buddhism. It rejected the salvation by faith and the devotional worship of Amidism, the cults of Kannon and the Lotus Sutra (“By yourself alone shall you be saved,” says Gautama). It reinstated yogic meditation with a view to final enlightenment as the central and essential practice of the Buddhist religious life. Finally, it reinstated Shakyamuni himself, Shaka, as he is known in Japanese: its special interpretation of the Buddha-life is modeled on his.

Since World War II, Zen Buddhism has become enormously popular in the West, and largely in response to its reception here it has seen an intellectual revival in Japan. Although Hearn was familiar with Zen theories and practices, and had Zen Buddhist friends, he wrote little about the sect that was to become the most influential in the West. Neither Zen as a manifestation of aristocratic traditions nor Zen as a popular fad interested him. Instead, he kept his eye on what had persisted in Japanese Buddhism through the centuries among the farmers, fishermen, and other poor folk. Many of their beliefs inform their stories, and many of their customs in turn have stories behind them. It was the survival of Buddhism in such forms that above all else engaged Hearn.

Hearn’s role in the spread of Buddhism to the West was a preparatory one. He was the first important American writer to live in Japan and to commit his imagination and considerable literary powers to what he found there. Like the “popular” expressions of Buddhist faith that were his favorite subject, Hearn popularized the Buddhist way of life for his Western readers. And he was widely read, both in his articles for Harper’s Magazine and the Atlantic Monthly, and in his numerous books on Japan. Hearn’s essays, with their rich descriptions and queer details, almost never generalizing but staying with a particular subject, always backed by the likeable and enthusiastic personality of Hearn himself, and always factually reliable, satisfied the vague and growing curiosity of his American readers about the mysterious East.

At St. Cuthbert’s school, at age fifteen, Hearn had discovered that he was a pantheist. That is not unusual for a fifteen-year-old, and the fact that pantheism is unaccepted in Christian doctrine or in Western philosophical thought normally suffices to extinguish the common adolescent philosophy or to transmute it to something less vulnerable. But the idea stuck with Hearn, and when finally, at forty, he arrived in Japan, he was delighted to find that he could now exercise and explore his intuition of God-in-All. If Hearn entered Japanese culture and achieved understanding of Japanese Buddhist (and Shinto) thought with unprecedented rapidity for a Westerner, it is because his own spirit had always longed for an atmosphere in which his belief in the sentience and blessedness of all Nature could flourish.

Hearn never became a Buddhist, and he remained skeptical about certain of Buddhism’s key doctrines — such as the relationship of karma and rebirth — but he passionately believed that Buddhism promoted a far better attitude toward daily life than did Christianity. It would be up to more scholarly and less imaginative writers to begin to translate and preach specific Buddhist doctrines, but Hearn has done much to translate the spirit of Japanese Buddhism and to prepare Western society for it.

KENNETH REXROTH

1977

This essay was originally published as the Introduction to The Buddhist Writings of Lafcadio Hearn (1977). It was reprinted in World Outside the Window: Selected Essays of Kenneth Rexroth (1987). The Buddhist Writings collection is out of print, but dozens of other Hearn books are still available.

Copyright 1987 Kenneth Rexroth Trust. Reproduced by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les autres peuples indo-européens, tout en conservant la fonction de ce dieu, oublièrent en revanche son nom. Les Celtes ne le désignèrent plus que par le nom de Cernunnos, le dieu « cornu ». En tant que tel, il était le dieu de la richesse de la nature, le maître des animaux sauvages comme d’élevage, le dieu conducteur des morts et un dieu magicien. Il avait enseigné aux druides son art sacré, d’où son abondante représentation en Gaule notamment. Sous le nom d’Hernè, il a pu s’imposer également chez les Germains voisins. Représenté avec des bois de cerf et non des cornes au sens strict, il était le dieu le plus important après Taranis et Lugus. En revanche, en Bretagne et en Irlande, il était absent. Son culte n’a pas pu traverser la Manche. Chez les Hittites, le dieu cornu Kahruhas était son strict équivalent mais notre connaissance à son sujet est des plus limités.

Les autres peuples indo-européens, tout en conservant la fonction de ce dieu, oublièrent en revanche son nom. Les Celtes ne le désignèrent plus que par le nom de Cernunnos, le dieu « cornu ». En tant que tel, il était le dieu de la richesse de la nature, le maître des animaux sauvages comme d’élevage, le dieu conducteur des morts et un dieu magicien. Il avait enseigné aux druides son art sacré, d’où son abondante représentation en Gaule notamment. Sous le nom d’Hernè, il a pu s’imposer également chez les Germains voisins. Représenté avec des bois de cerf et non des cornes au sens strict, il était le dieu le plus important après Taranis et Lugus. En revanche, en Bretagne et en Irlande, il était absent. Son culte n’a pas pu traverser la Manche. Chez les Hittites, le dieu cornu Kahruhas était son strict équivalent mais notre connaissance à son sujet est des plus limités.

Rispetto all’interesse evoliano per il dato esoterico-politico nell’Alighieri, è opportuno ricordare che la cerca del Poeta è sintonica, e la cosa è accortamente rilevata da Consolato, a quella che maturò negli ambienti graalici in rapporto al problema dell’Impero. Caratterizzata, in particolare, dal continuo riferirsi al motivo dell’imperatore latente, mai morto e per questo atteso e al Regno isterilito, simbolizzato in modo paradigmatico dall’Albero secco che rinverdirà con il rimanifestarsi nella storia dell’Impero, per l’azione del Veltro-Dux. L’Impero, per esser tale, deve far riferimento ad un re-sacerdote il cui modello è Melchisedec, custode della funzione attiva e di quella contemplativa. L’autore suggerisce che in tema di Veltro e relativamente alla sua esegesi storico-politica, Evola si richiama alla lezione di Alfred Bassermann, grazie alla quale egli coglie come Dante, in tema, si sia fermato a metà strada, “la sua concezione dei rapporti tra Chiesa e Impero rimase imperniata su di un dualismo limitatore…tra vita contemplativa e vita attiva” (p. 39). Lo stesso esoterismo dell’Alighieri era legato ad una sorta di via iniziatica platonizzante, non pienamente giunta a rilevare, come accadrà nel puro templarismo, che l’iniziazione regale risolve in sé i due momenti del Principio, contemplazione ed azione. In questo contesto, suggerisce Consolato, deve essere letta la polemica di Cecco d’Ascoli nei confronti dell’Alighieri, attaccato in quanto “deviazionista” rispetto all’iniziazione propriamente regale. In questi termini, Dante è il simbolo più proprio, per Evola, dell’età in cui visse, il

Rispetto all’interesse evoliano per il dato esoterico-politico nell’Alighieri, è opportuno ricordare che la cerca del Poeta è sintonica, e la cosa è accortamente rilevata da Consolato, a quella che maturò negli ambienti graalici in rapporto al problema dell’Impero. Caratterizzata, in particolare, dal continuo riferirsi al motivo dell’imperatore latente, mai morto e per questo atteso e al Regno isterilito, simbolizzato in modo paradigmatico dall’Albero secco che rinverdirà con il rimanifestarsi nella storia dell’Impero, per l’azione del Veltro-Dux. L’Impero, per esser tale, deve far riferimento ad un re-sacerdote il cui modello è Melchisedec, custode della funzione attiva e di quella contemplativa. L’autore suggerisce che in tema di Veltro e relativamente alla sua esegesi storico-politica, Evola si richiama alla lezione di Alfred Bassermann, grazie alla quale egli coglie come Dante, in tema, si sia fermato a metà strada, “la sua concezione dei rapporti tra Chiesa e Impero rimase imperniata su di un dualismo limitatore…tra vita contemplativa e vita attiva” (p. 39). Lo stesso esoterismo dell’Alighieri era legato ad una sorta di via iniziatica platonizzante, non pienamente giunta a rilevare, come accadrà nel puro templarismo, che l’iniziazione regale risolve in sé i due momenti del Principio, contemplazione ed azione. In questo contesto, suggerisce Consolato, deve essere letta la polemica di Cecco d’Ascoli nei confronti dell’Alighieri, attaccato in quanto “deviazionista” rispetto all’iniziazione propriamente regale. In questi termini, Dante è il simbolo più proprio, per Evola, dell’età in cui visse, il

Lafcadio Hearn was born on the Ionian island of Santa Maura in either June or August 1850 and died in Okubo, Japan in 1904. His father was an Irish surgeon major stationed in Greece and his mother a Greek woman, famous for her beauty. It was she who named him Lafcadio, after Leudakia, the ancient name of Santa Maura, one of the islands connected with the legend of Sappho. In a relatively short lifespan of fifty-four years he managed to live several different literary lives.

Lafcadio Hearn was born on the Ionian island of Santa Maura in either June or August 1850 and died in Okubo, Japan in 1904. His father was an Irish surgeon major stationed in Greece and his mother a Greek woman, famous for her beauty. It was she who named him Lafcadio, after Leudakia, the ancient name of Santa Maura, one of the islands connected with the legend of Sappho. In a relatively short lifespan of fifty-four years he managed to live several different literary lives.  In spite of the incredible changes that have taken place in Japan since Hearn’s death in 1904, as an informant of Japanese life, literature, and religion he is still amazingly reliable, because beneath the effects of industrialization, war, population explosion, and prosperity much of Japanese life remains unchanged. For Hearn the old Japan — the art, traditions, and myths that had persisted for centuries — was the only Japan worth paying attention to. Two world wars and Japan’s astonishing emergence as a modern nation temporarily extinguished the credibility of Hearn’s vision of traditional Japanese culture. But both in the West and in Japan interest in the old forms of Japanese culture is increasing. In Tokyo there are still thousands of people living the old life by the traditional values alongside the most extreme effects of Westernization. Pet crickets, for example, still command high prices, and more people apply their new prosperity to learning tea ceremony, calligraphy, flower arrangement and sumi-e painting than ever before. Ghost stories like those told by Hearn are popular on television; three of his own were recently combined to make a successful movie that preserves his title, Kwaidan.

In spite of the incredible changes that have taken place in Japan since Hearn’s death in 1904, as an informant of Japanese life, literature, and religion he is still amazingly reliable, because beneath the effects of industrialization, war, population explosion, and prosperity much of Japanese life remains unchanged. For Hearn the old Japan — the art, traditions, and myths that had persisted for centuries — was the only Japan worth paying attention to. Two world wars and Japan’s astonishing emergence as a modern nation temporarily extinguished the credibility of Hearn’s vision of traditional Japanese culture. But both in the West and in Japan interest in the old forms of Japanese culture is increasing. In Tokyo there are still thousands of people living the old life by the traditional values alongside the most extreme effects of Westernization. Pet crickets, for example, still command high prices, and more people apply their new prosperity to learning tea ceremony, calligraphy, flower arrangement and sumi-e painting than ever before. Ghost stories like those told by Hearn are popular on television; three of his own were recently combined to make a successful movie that preserves his title, Kwaidan.  Buddha was born in Kapilavastu, now Rummimdei, Nepal, sometime around 563 BC and died about 483 BC in Kusimara, now Kasia, India. His personal name was Siddhartha Gautama. Buddha, The Enlightened One, is a title, not a name, as is Shakyamuni, the saint of the Shaka clan. In Japan, the historic Buddha is commonly known as Shakya. He was a member of the Kshatriya warrior caste, the son of the ruler of a small principality.

Buddha was born in Kapilavastu, now Rummimdei, Nepal, sometime around 563 BC and died about 483 BC in Kusimara, now Kasia, India. His personal name was Siddhartha Gautama. Buddha, The Enlightened One, is a title, not a name, as is Shakyamuni, the saint of the Shaka clan. In Japan, the historic Buddha is commonly known as Shakya. He was a member of the Kshatriya warrior caste, the son of the ruler of a small principality.  The story of the development of Mahayana as it spread from what is now Afghanistan and Russian Turkestan to Mongolia and Indonesia to Tibet, China and Japan, while it died out in India, would take many thousands of words to tell. There are traces of Buddhism in China two hundred years or more before the Christian era. Its official introduction is supposed to have occurred in the first century AD. From then until the Muslim conquest of India, Chinese pilgrims visited India and brought back caravan loads of statuaries and sutras (sacred texts) which were translated into Chinese.

The story of the development of Mahayana as it spread from what is now Afghanistan and Russian Turkestan to Mongolia and Indonesia to Tibet, China and Japan, while it died out in India, would take many thousands of words to tell. There are traces of Buddhism in China two hundred years or more before the Christian era. Its official introduction is supposed to have occurred in the first century AD. From then until the Muslim conquest of India, Chinese pilgrims visited India and brought back caravan loads of statuaries and sutras (sacred texts) which were translated into Chinese.

Celui qui l’a appris à ses dépens, c’est un Néo-Zélandais, gérant de bar en Birmanie (Myanmar, SVP), un certain Phil Blackwood, condamné à deux ans et demi de prison pour avoir portraituré Bouddha avec des écouteurs sur la tête, juste histoire de faire de la publicité pour son bar, « lounge », évidemment. Eh oui, le bouddhisme, ce n’est pas forcément la fête du slip tous les dimanches. Le Phil Blackwood en question a eu beau s’excuser, battre coulpe et montrer patte blanche : pas de remise de peine et case prison direct.

Celui qui l’a appris à ses dépens, c’est un Néo-Zélandais, gérant de bar en Birmanie (Myanmar, SVP), un certain Phil Blackwood, condamné à deux ans et demi de prison pour avoir portraituré Bouddha avec des écouteurs sur la tête, juste histoire de faire de la publicité pour son bar, « lounge », évidemment. Eh oui, le bouddhisme, ce n’est pas forcément la fête du slip tous les dimanches. Le Phil Blackwood en question a eu beau s’excuser, battre coulpe et montrer patte blanche : pas de remise de peine et case prison direct. Le penseur français René Guénon (1886 – 1957) ne suscite que très rarement l’intérêt de l’université hexagonale. On doit par conséquent se réjouir de la sortie de René Guénon. Une politique de l’esprit par David Bisson. À l’origine travail universitaire, cet ouvrage a été entièrement retravaillé par l’auteur pour des raisons d’attraction éditoriale évidente. C’est une belle réussite aidée par une prose limpide et captivante.

Le penseur français René Guénon (1886 – 1957) ne suscite que très rarement l’intérêt de l’université hexagonale. On doit par conséquent se réjouir de la sortie de René Guénon. Une politique de l’esprit par David Bisson. À l’origine travail universitaire, cet ouvrage a été entièrement retravaillé par l’auteur pour des raisons d’attraction éditoriale évidente. C’est une belle réussite aidée par une prose limpide et captivante. Au cours de l’Entre-deux-guerres, le futur historien des religions affine sa propre vision du monde. Alimentant sa réflexion d’une immense curiosité pluridisciplinaire, il a lu – impressionné – les écrits de Guénon. D’abord rétif à tout militantisme politique, Eliade se résout sous la pression de ses amis et de son épouse à participer au mouvement politico-mystique de Corneliu Codreanu. Il y devient alors une des principales figures intellectuelles et y rencontre un nommé Cioran. Au sein de cet ordre politico-mystique, Eliade propose un « nationalisme archaïque (p. 252) » qui assigne à la Roumanie une vocation exceptionnelle. Son engagement dans la Garde de Fer ne l’empêche pas de mener une carrière de diplomate qui se déroule en Grande-Bretagne, au Portugal et en Allemagne. Son attrait pour les « mentalités primitives » et les sociétés traditionnelles pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale s’accroît si bien qu’exilé en France après 1945, il jette les premières bases de l’histoire des religions qui le feront bientôt devenir l’universitaire célèbre de Chicago. Si Eliade s’éloigne de Guénon et ne le cite jamais, David Bisson signale cependant qu’il lui expédie ses premiers ouvrages. En retour, ils font l’objet de comptes-rendus précis. Bisson peint finalement le portrait d’un Mircea Eliade louvoyant, désireux de faire connaître et de pérenniser son œuvre.

Au cours de l’Entre-deux-guerres, le futur historien des religions affine sa propre vision du monde. Alimentant sa réflexion d’une immense curiosité pluridisciplinaire, il a lu – impressionné – les écrits de Guénon. D’abord rétif à tout militantisme politique, Eliade se résout sous la pression de ses amis et de son épouse à participer au mouvement politico-mystique de Corneliu Codreanu. Il y devient alors une des principales figures intellectuelles et y rencontre un nommé Cioran. Au sein de cet ordre politico-mystique, Eliade propose un « nationalisme archaïque (p. 252) » qui assigne à la Roumanie une vocation exceptionnelle. Son engagement dans la Garde de Fer ne l’empêche pas de mener une carrière de diplomate qui se déroule en Grande-Bretagne, au Portugal et en Allemagne. Son attrait pour les « mentalités primitives » et les sociétés traditionnelles pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale s’accroît si bien qu’exilé en France après 1945, il jette les premières bases de l’histoire des religions qui le feront bientôt devenir l’universitaire célèbre de Chicago. Si Eliade s’éloigne de Guénon et ne le cite jamais, David Bisson signale cependant qu’il lui expédie ses premiers ouvrages. En retour, ils font l’objet de comptes-rendus précis. Bisson peint finalement le portrait d’un Mircea Eliade louvoyant, désireux de faire connaître et de pérenniser son œuvre. En étroite correspondance épistolaire avec Guénon, Schuon devient son « fils spirituel ». cela lui permet de recruter de nouveaux membres pour sa confrérie soufie qu’il développe en Europe. D’abord favorable à son islamisation, Schuon devient ensuite plus nuancé, « la forme islamique ne contrevenant, en aucune manière, à la dimension chrétienne de l’Europe. Il essaiera même de fondre les deux perspectives dans une approche universaliste dont l’ésotérisme sera le vecteur (p. 172) ». Cette démarche syncrétiste s’appuie dès l’origine sur son nom musulman signifiant « Jésus, Lumière de la Tradition».

En étroite correspondance épistolaire avec Guénon, Schuon devient son « fils spirituel ». cela lui permet de recruter de nouveaux membres pour sa confrérie soufie qu’il développe en Europe. D’abord favorable à son islamisation, Schuon devient ensuite plus nuancé, « la forme islamique ne contrevenant, en aucune manière, à la dimension chrétienne de l’Europe. Il essaiera même de fondre les deux perspectives dans une approche universaliste dont l’ésotérisme sera le vecteur (p. 172) ». Cette démarche syncrétiste s’appuie dès l’origine sur son nom musulman signifiant « Jésus, Lumière de la Tradition». Mais qu’est-ce que la multipolarité ? Pour Alexandre Douguine, ce phénomène « procède d’un constat : l’inégalité fondamentale entre les États-nations dans le monde moderne, que chacun peut observer empiriquement. En outre, structurellement, cette inégalité est telle que les puissances de deuxième ou de troisième rang ne sont pas en mesure de défendre leur souveraineté face à un défi de la puissance hégémonique, quelle que soit l’alliance de circonstance que l’on envisage. Ce qui signifie que cette souveraineté est aujourd’hui une fiction juridique (pp. 8 – 9) ». « La multipolarité sous-tend seulement l’affirmation que, dans le processus actuel de mondialisation, le centre incontesté, le noyau du monde moderne (les États-Unis, l’Europe et plus largement le monde occidental) est confronté à de nouveaux concurrents, certains pouvant être prospères voire émerger comme puissances régionales et blocs de pouvoir. On pourrait définir ces derniers comme des “ puissances de second rang ”. En comparant les potentiels respectifs des États-Unis et de l’Europe, d’une part, et ceux des nouvelles puissances montantes (la Chine, l’Inde, la Russie, l’Amérique latine, etc.), d’autre part, de plus en plus nombreux sont ceux qui sont convaincus que la supériorité traditionnelle de l’Occident est toute relative, et qu’il y a lieu de s’interroger sur la logique des processus qui déterminent l’architecture globale des forces à l’échelle planétaire – politique, économie, énergie, démographie, culture, etc. (p. 5) ». Elle « implique l’existence de centres de prise de décision à un niveau relativement élevé (sans toutefois en arriver au cas extrême d’un centre unique, comme c’est aujourd’hui le cas dans les conditions du monde unipolaire). Le système multipolaire postule également la préservation et le renforcement des particularités culturelles de chaque civilisation, ces dernières ne devant pas se dissoudre dans une multiplicité cosmopolite unique (p. 17) ». Le philosophe russe s’inspire de certaines thèses de l’universitaire réaliste étatsunien, Samuel Huntington. Tout en déplorant les visées atlantistes et occidentalistes, l’eurasiste russe salue l’« intuition de Huntington qui, en passant des États-nations aux civilisations, induit un changement qualitatif dans la définition de l’identité des acteurs du nouvel ordre mondial (p. 96) ».

Mais qu’est-ce que la multipolarité ? Pour Alexandre Douguine, ce phénomène « procède d’un constat : l’inégalité fondamentale entre les États-nations dans le monde moderne, que chacun peut observer empiriquement. En outre, structurellement, cette inégalité est telle que les puissances de deuxième ou de troisième rang ne sont pas en mesure de défendre leur souveraineté face à un défi de la puissance hégémonique, quelle que soit l’alliance de circonstance que l’on envisage. Ce qui signifie que cette souveraineté est aujourd’hui une fiction juridique (pp. 8 – 9) ». « La multipolarité sous-tend seulement l’affirmation que, dans le processus actuel de mondialisation, le centre incontesté, le noyau du monde moderne (les États-Unis, l’Europe et plus largement le monde occidental) est confronté à de nouveaux concurrents, certains pouvant être prospères voire émerger comme puissances régionales et blocs de pouvoir. On pourrait définir ces derniers comme des “ puissances de second rang ”. En comparant les potentiels respectifs des États-Unis et de l’Europe, d’une part, et ceux des nouvelles puissances montantes (la Chine, l’Inde, la Russie, l’Amérique latine, etc.), d’autre part, de plus en plus nombreux sont ceux qui sont convaincus que la supériorité traditionnelle de l’Occident est toute relative, et qu’il y a lieu de s’interroger sur la logique des processus qui déterminent l’architecture globale des forces à l’échelle planétaire – politique, économie, énergie, démographie, culture, etc. (p. 5) ». Elle « implique l’existence de centres de prise de décision à un niveau relativement élevé (sans toutefois en arriver au cas extrême d’un centre unique, comme c’est aujourd’hui le cas dans les conditions du monde unipolaire). Le système multipolaire postule également la préservation et le renforcement des particularités culturelles de chaque civilisation, ces dernières ne devant pas se dissoudre dans une multiplicité cosmopolite unique (p. 17) ». Le philosophe russe s’inspire de certaines thèses de l’universitaire réaliste étatsunien, Samuel Huntington. Tout en déplorant les visées atlantistes et occidentalistes, l’eurasiste russe salue l’« intuition de Huntington qui, en passant des États-nations aux civilisations, induit un changement qualitatif dans la définition de l’identité des acteurs du nouvel ordre mondial (p. 96) ». Piochant dans toutes les écoles théoriques existantes, le choix multipolaire de Douguine n’est au fond que l’application à un domaine particulier – la géopolitique – de ce qu’il nomme la « Quatrième théorie politique ». Titre d’un ouvrage essentiel, cette nouvelle pensée politique prend acte de la victoire de la première théorie politique, le libéralisme, sur la deuxième, le communisme, et la troisième, le fascisme au sens très large, y compris le national-socialisme.

Piochant dans toutes les écoles théoriques existantes, le choix multipolaire de Douguine n’est au fond que l’application à un domaine particulier – la géopolitique – de ce qu’il nomme la « Quatrième théorie politique ». Titre d’un ouvrage essentiel, cette nouvelle pensée politique prend acte de la victoire de la première théorie politique, le libéralisme, sur la deuxième, le communisme, et la troisième, le fascisme au sens très large, y compris le national-socialisme.

Nachdem die Zahl der Anhänger der nordischen Glaubensrichtung sich auf Island seit dem Jahr 2000 verfünffacht hat, soll in der isländischen Hauptstadt Reykjavík erstmals seit der Wikingerzeit wiedereine heidnische Kultstätte entstehen.Nach der Christianisierung Islands im Jahre 1000 durfte das Heidentum nicht mehr praktiziert werden.

Nachdem die Zahl der Anhänger der nordischen Glaubensrichtung sich auf Island seit dem Jahr 2000 verfünffacht hat, soll in der isländischen Hauptstadt Reykjavík erstmals seit der Wikingerzeit wiedereine heidnische Kultstätte entstehen.Nach der Christianisierung Islands im Jahre 1000 durfte das Heidentum nicht mehr praktiziert werden.

La testimonianza archeologica che più può essere d’aiuto per comprendere il complesso sistema iniziatico del culto di Mithra è sicuramente il mosaico pavimentale presente nel mitreo di Felicissimo ad Ostia, denominato Scala delle Sette Porte. Sia Celso sia Porfirio ci parlano di un’iniziazone con sette diversi e gerarchici gradi di conoscenza e, come rappresentato nelle sette porte di Ostia, ognuno rappresentato dall’animale simbolico e dall’Astro/Nume di riferimento. Il primo grado è rappresentato dal Corax (Corvo), egli è la base del culto mithriaco, il neofita che affronta le prime prove di umiltà, di controllo dell’ego, di mantenimento del segreto. Simboleggiato appunto da un corvo, è il messaggero degli Dei che risvegliano Mithra, avendo in Hermes-Mercurio la propria divinità tutelare. Il risveglio è l’inizio della rettificazione del myste, il risveglio della propria essenza solare: ogni rettificazione la si può riconnettere ai centri di luce, chakra nella tradizione indù o sephira in quella cabalistica, lungo il canale verticale che corre lungo la colonna vertebrale, espressione proprio di un Caduceo Ermetico che ritroviamo tra i simboli di Hermes e del Corax, ove si intrecciano le energie lunari e solari, mercuriali e sulfuree, lungo quello che viene denominato il “canale di Brahma”.

La testimonianza archeologica che più può essere d’aiuto per comprendere il complesso sistema iniziatico del culto di Mithra è sicuramente il mosaico pavimentale presente nel mitreo di Felicissimo ad Ostia, denominato Scala delle Sette Porte. Sia Celso sia Porfirio ci parlano di un’iniziazone con sette diversi e gerarchici gradi di conoscenza e, come rappresentato nelle sette porte di Ostia, ognuno rappresentato dall’animale simbolico e dall’Astro/Nume di riferimento. Il primo grado è rappresentato dal Corax (Corvo), egli è la base del culto mithriaco, il neofita che affronta le prime prove di umiltà, di controllo dell’ego, di mantenimento del segreto. Simboleggiato appunto da un corvo, è il messaggero degli Dei che risvegliano Mithra, avendo in Hermes-Mercurio la propria divinità tutelare. Il risveglio è l’inizio della rettificazione del myste, il risveglio della propria essenza solare: ogni rettificazione la si può riconnettere ai centri di luce, chakra nella tradizione indù o sephira in quella cabalistica, lungo il canale verticale che corre lungo la colonna vertebrale, espressione proprio di un Caduceo Ermetico che ritroviamo tra i simboli di Hermes e del Corax, ove si intrecciano le energie lunari e solari, mercuriali e sulfuree, lungo quello che viene denominato il “canale di Brahma”.  Il terzo grado è quello del Miles (Soldato), simboleggiato dallo scorpione, rappresenta, tramite la consacrazione a Mithra ed il rifiuto dell’incoronazione umana (“Mithra è la mia corona!”), l’ingresso dell’iniziato nella Milizia Celeste, coloro che combattono per il Fuoco e la Luce, avendo in Marte il proprio nume tutelare. E’ il chakra Manipura dove ha sede il fuoco, in corrispondenza con il plesso solare, o l’ottavo sephira Hod, la sapienza e la collettività, quindi Mithra che esce armato dalla grotta platonica per combattere, con la lancia di Marte, per affrontare un cammino oscuro che non conosce, è l’elemento ferreo che si attiva, l’irrazionale che cerca di purificarsi, la forza guerriera cieca, istintiva, che intraprende la via per la propria purificazione: alchemicamente si arriva alla terza operazione, quella della soluzione, ove si produce l’unione progressiva e non violenta del fisso col volatile…il Fuoco deve essere ancor tenuto basso!

Il terzo grado è quello del Miles (Soldato), simboleggiato dallo scorpione, rappresenta, tramite la consacrazione a Mithra ed il rifiuto dell’incoronazione umana (“Mithra è la mia corona!”), l’ingresso dell’iniziato nella Milizia Celeste, coloro che combattono per il Fuoco e la Luce, avendo in Marte il proprio nume tutelare. E’ il chakra Manipura dove ha sede il fuoco, in corrispondenza con il plesso solare, o l’ottavo sephira Hod, la sapienza e la collettività, quindi Mithra che esce armato dalla grotta platonica per combattere, con la lancia di Marte, per affrontare un cammino oscuro che non conosce, è l’elemento ferreo che si attiva, l’irrazionale che cerca di purificarsi, la forza guerriera cieca, istintiva, che intraprende la via per la propria purificazione: alchemicamente si arriva alla terza operazione, quella della soluzione, ove si produce l’unione progressiva e non violenta del fisso col volatile…il Fuoco deve essere ancor tenuto basso!  L’esame del settimo grado dell’iniziazione mithriaca, quello del Pater, comporta necessariamente un approfondimento del mito centrale e fondante del culto in questione, cioè il sacrificio cosmogonico ed esoterico del toro: tale mito, insieme alla tutela mithriaca dei patti e dei giuramenti, è sicuramente presente sin dall’origini indoiraniche della divinità e ne rappresenta simbolicamente la più alta valenza metafisica. Mithra nato dalla roccia il giorno del Solstizio d’Inverno e uscito dalla caverna nel grado di Miles, sa di dover immolare il toro, per ordine degli Dei su mandato del loro messaggero, il corvo Hermes-Mercurio.

L’esame del settimo grado dell’iniziazione mithriaca, quello del Pater, comporta necessariamente un approfondimento del mito centrale e fondante del culto in questione, cioè il sacrificio cosmogonico ed esoterico del toro: tale mito, insieme alla tutela mithriaca dei patti e dei giuramenti, è sicuramente presente sin dall’origini indoiraniche della divinità e ne rappresenta simbolicamente la più alta valenza metafisica. Mithra nato dalla roccia il giorno del Solstizio d’Inverno e uscito dalla caverna nel grado di Miles, sa di dover immolare il toro, per ordine degli Dei su mandato del loro messaggero, il corvo Hermes-Mercurio.  Molti sono stati gli scritti, gli articoli, i testi che profondamente hanno indagato la simbolica e l’essenza tradizionale e spirituale dell’iniziazione mithriaca, ma, purtroppo, pochi hanno ben evidenziato come il settimo grado di tale culto misterico, quello del Pater, non rappresentasse l’ultima tappa dell’ascensione al Divino. Se profanamente si provasse a schematizzare il processo iniziatico di cui si è scritto, sarebbe possibile confrontarlo, riducendo il settenario in forma quaternaria, alle varie fasi dell’Opera Alchemica ed alla suddivisione microcosmica operata dal Kremmerz e dalla sua Schola. Infatti, le prime quattro figure che partono dal Corax ed arrivano al Leone è possibile paragonarle alle quattro operazioni dell’Opera al Nero, la Nigredo (calcinazione, putrefazione, soluzione, distillazione ), mentre la figura del Pherses, sotto l’egida astrale della Luna, e quella di Heliodromos, portatore del Sole ma non il Sole, configurano la dimensione numinosa della nuda Diana, dell’immortalità virtuale, quindi della realizzazione dell’Opera al Bianco, Albedo.

Molti sono stati gli scritti, gli articoli, i testi che profondamente hanno indagato la simbolica e l’essenza tradizionale e spirituale dell’iniziazione mithriaca, ma, purtroppo, pochi hanno ben evidenziato come il settimo grado di tale culto misterico, quello del Pater, non rappresentasse l’ultima tappa dell’ascensione al Divino. Se profanamente si provasse a schematizzare il processo iniziatico di cui si è scritto, sarebbe possibile confrontarlo, riducendo il settenario in forma quaternaria, alle varie fasi dell’Opera Alchemica ed alla suddivisione microcosmica operata dal Kremmerz e dalla sua Schola. Infatti, le prime quattro figure che partono dal Corax ed arrivano al Leone è possibile paragonarle alle quattro operazioni dell’Opera al Nero, la Nigredo (calcinazione, putrefazione, soluzione, distillazione ), mentre la figura del Pherses, sotto l’egida astrale della Luna, e quella di Heliodromos, portatore del Sole ma non il Sole, configurano la dimensione numinosa della nuda Diana, dell’immortalità virtuale, quindi della realizzazione dell’Opera al Bianco, Albedo.

El Islam, en cambio, incluso en nuestras sociedades, a menudo trae elementos y valores realmente incompatibles con la modernidad y, por lo tanto, difícilmente “integrables”. Y es eso lo que las fuerzas identitarias le reprochan, viendo a sus miembros como sujetos extraños y alógenos respecto a nuestro mundo, a diferencia, como se ha dicho, de los seguidores de otras religiones que, al igual que los cristianos, más allá de las formas externas que aún permanezcan en las prácticas del culto, por lo demás están totalmente homologados a las costumbres y al estilo de vida materialista y consumista propio de nuestra civilización. Así, una mujer musulmana que viste su ropa tradicional, como por ejemplo el velo, genera protestas y casi un sentimiento de repulsión que está en conformidad con nuestra “tradición”, los atuendos con los cuales se engalanan nuestras chicas respetando la última moda lanzada por la etiqueta del momento. Del mismo modo, la apertura de un kebab o de una carnicería musulmana irían a desfigurar, para los lugareños “identitarios”, la decoración urbana de nuestras calles, mientras que un McDonalds o un local de moda y tendencias no. Los ejemplos podrían multiplicarse: hace años, en Suiza, los partidos identitarios organizaron un referéndum contra la construcción de minaretes porque éstos implicarían la ruptura de la arquitectura típica de las ciudades suizas: no consta que tales partidos, en Suiza como en otros lugares, se hayan levantado alguna vez, al menos con el mismo ardor, en contra de la excéntrica arquitectura moderna que desfigura habitualmente nuestros centros históricos, como en general nuestros barrios, por no hablar de los eco-monstruos de nuestros suburbios, donde ahora todo el sentido de la proporción, la armonía, y por lo tanto de lo “bello” está completamente perdido, y no ciertamente por culpa de los minaretes o de quién sabe qué otro exótico edificio.

El Islam, en cambio, incluso en nuestras sociedades, a menudo trae elementos y valores realmente incompatibles con la modernidad y, por lo tanto, difícilmente “integrables”. Y es eso lo que las fuerzas identitarias le reprochan, viendo a sus miembros como sujetos extraños y alógenos respecto a nuestro mundo, a diferencia, como se ha dicho, de los seguidores de otras religiones que, al igual que los cristianos, más allá de las formas externas que aún permanezcan en las prácticas del culto, por lo demás están totalmente homologados a las costumbres y al estilo de vida materialista y consumista propio de nuestra civilización. Así, una mujer musulmana que viste su ropa tradicional, como por ejemplo el velo, genera protestas y casi un sentimiento de repulsión que está en conformidad con nuestra “tradición”, los atuendos con los cuales se engalanan nuestras chicas respetando la última moda lanzada por la etiqueta del momento. Del mismo modo, la apertura de un kebab o de una carnicería musulmana irían a desfigurar, para los lugareños “identitarios”, la decoración urbana de nuestras calles, mientras que un McDonalds o un local de moda y tendencias no. Los ejemplos podrían multiplicarse: hace años, en Suiza, los partidos identitarios organizaron un referéndum contra la construcción de minaretes porque éstos implicarían la ruptura de la arquitectura típica de las ciudades suizas: no consta que tales partidos, en Suiza como en otros lugares, se hayan levantado alguna vez, al menos con el mismo ardor, en contra de la excéntrica arquitectura moderna que desfigura habitualmente nuestros centros históricos, como en general nuestros barrios, por no hablar de los eco-monstruos de nuestros suburbios, donde ahora todo el sentido de la proporción, la armonía, y por lo tanto de lo “bello” está completamente perdido, y no ciertamente por culpa de los minaretes o de quién sabe qué otro exótico edificio.

Sa postérité est telle que ce que nous connaissons réellement de sa vie fraye avec le romanesque et le légendaire, et bien sûr ce personnage atypique a ses adulateurs et détracteurs chez les amoureux de la culture japonaise et des arts martiaux. Ce qui est certain, à la lecture des Écrits sur les Cinq Éléments, c'est que Musashi était un esprit libre en phase avec la vie. Ces cinq rouleaux rédigés à l'extrême fin de sa vie étaient destinés à transmettre l'essence de son art à ses élèves.

Sa postérité est telle que ce que nous connaissons réellement de sa vie fraye avec le romanesque et le légendaire, et bien sûr ce personnage atypique a ses adulateurs et détracteurs chez les amoureux de la culture japonaise et des arts martiaux. Ce qui est certain, à la lecture des Écrits sur les Cinq Éléments, c'est que Musashi était un esprit libre en phase avec la vie. Ces cinq rouleaux rédigés à l'extrême fin de sa vie étaient destinés à transmettre l'essence de son art à ses élèves.

Miyamoto Mikinosuke deviendra un vassal de la seigneurie de Himeji (1622), mais le jeune homme suivra son seigneur dans la mort en pratiquant le suicide rituel (1626). Miyamoto Iori, qui serait peut-être un sien neveu, entrera au service du seigneur Ogasawara (1626). Surtout, en 1624, il séjourne à Edo, la capitale, et noue d’étroites relations avec Hayashi Razan, un célèbre savant confucéen, ce dernier proche du Shôgun l’aurait proposé comme maître de sabre, mais le Shôgun disposant déjà de deux maîtres d’armes de renom, Yagyû Munenori (école shinkage ryû) et

Miyamoto Mikinosuke deviendra un vassal de la seigneurie de Himeji (1622), mais le jeune homme suivra son seigneur dans la mort en pratiquant le suicide rituel (1626). Miyamoto Iori, qui serait peut-être un sien neveu, entrera au service du seigneur Ogasawara (1626). Surtout, en 1624, il séjourne à Edo, la capitale, et noue d’étroites relations avec Hayashi Razan, un célèbre savant confucéen, ce dernier proche du Shôgun l’aurait proposé comme maître de sabre, mais le Shôgun disposant déjà de deux maîtres d’armes de renom, Yagyû Munenori (école shinkage ryû) et  Le jitte est une arme de neutralisation, sa lame est non-tranchante et effilée avec une griffe latérale au niveau de la garde. Le jitte était une arme d’appoint complétant le sabre. Toutefois, selon d’autres sources le jitte manipulé par Musashi aurait été un modèle à dix griffes. Le jitte et le sabre court (wakizashi) servaient à immobiliser ou à parer la lame de l’adversaire offrant une ouverture pour une frappe au sabre long (katana). Toutefois, pour Musashi, l’emploi des deux sabres est circonstancielle comme l’affirme les Écrits sur les Cinq Éléments, mais cette technique fait l’originalité de son école. C’était peut-être, outre les aspects techniques, un moyen de se différencier et de « séduire » un seigneur en quête d’instructeur. L’école de Musashi, la