dimanche, 17 novembre 2013

L'uomo che cavalcava la tigre

L'uomo che cavalcava la tigre. Il viaggio esoterico del barone Julius

di Andrea Scarabelli

Quello che presentiamo è un autentico viaggio, realizzato attraverso le opere pittoriche evoliane, che ripercorre le tappe fondamentali della vita di quello che è uno dei protagonisti della cultura novecentesca. Un viaggio nel quale Evola non è una semplice comparsa ma autentico medium delle sue opere, trascinando il lettore all'interno del suo mondo, biografico ma soprattutto metabiografico.

Quello che presentiamo è un autentico viaggio, realizzato attraverso le opere pittoriche evoliane, che ripercorre le tappe fondamentali della vita di quello che è uno dei protagonisti della cultura novecentesca. Un viaggio nel quale Evola non è una semplice comparsa ma autentico medium delle sue opere, trascinando il lettore all'interno del suo mondo, biografico ma soprattutto metabiografico.

Un passo per volta, però. Lo sfondo di queste pagine è il vernissage di un'ipotetica esposizione: “Ea, Jagla, Julius Evola (1898-1974), poeta, pittore, filosofo. Il barone magico. Attraverso questa Mostra, promossa dalla Fondazione Julius Evola, conosceremo l'Evola pittore futurista e dadaista. È questa la prima retrospettiva a lui dedicata nel XXI secolo” (p. 13). Henriet ci invita a questa esposizione immaginaria, all'interno della quale ogni dipinto prende vita, inaugura una dimensione metatemporale e ci conduce attraverso le sillabe alchemiche dell'universo pittorico evoliano. Senza però fermarsi alle tele, a futurismo e dadaismo ma estendendosi all'interezza della “tavolozza dai molti colori dell'Irrazionalismo evoliano” (p. 13), momento altresì fondamentale per accedere alla cultura continentale novecentesca. E chi conosce il pensiero di Evola sa bene che tipo di valenza conferire al termine “irrazionale”...

Ad accompagnare il lettore altri non è che Evola stesso, a volte sostituito dal suo doppio Ea (uno degli pseudonimi con cui questi firmava taluni dei suoi contributi su Ur e Krur, alla fine degli anni Venti). Ogni dipinto “esposto” in quella che può considerarsi una galleria anzitutto interiore ridesta nel filosofo ricordi, universi, dimensioni – realtà. In ognuno dei ventisei capitoli che costituiscono il volumetto – molti dei quali recano, non casualmente, i titoli di opere evoliane, come Five o' clock tea, Nel bosco e Truppe di rincalzo sotto la pioggia – il lettore percorre i labirinti di Evola, ognuno dei quali avente una via d'accesso differente ma tutti diretti verso il cuore della sua Weltanschauung.

In questa dimensione, a metà tra la realtà fisica ed una onirico-allucinatoria, personaggi reali interagiscono con figure fantastiche – questo l'intreccio, abilmente restituito dalle pagine di Henriet. Non è difficile così scorgere un Evola intento a leggere recensioni dei suoi dipinti sulle colonne di riviste intemporali, intrattenere conversazioni con personaggi fantastici, percorrere dimensioni ontologiche ultraterrene. Ma, al contempo, a questi itinerari sono accostati momenti storici ben precisi, con il loro corollario umano - appaiono allora Arturo Reghini, Sibilla Aleramo, Arturo Onofri, Giulio Parise e gli iniziati del Gruppo di Ur.

Ed ecco evocati, come d'incanto, gli anni Venti, delle avanguardie e dei cenacoli esoterici. Ecco le feste organizzate dagli aristocratici, frequentate dal giovane Evola, nella fattispecie una, tenutasi per festeggiare la fine della Prima Guerra Mondiale: “Julius è vestito di nero, ed ha il volto coperto da una maschera aurea, provvista di un lungo naso conico” (p. 16). È l'unico, in Italia, tra i futuristi, ad apprezzare l'arte astratta. Il futurismo non è che una maschera, gli rivela la duchessa de Andri, organizzatrice della festa, liberatevene. E, tra le boutade di Marinetti e gli abiti disegnati da Depero, “egli andò oltre” (p. 22).

Non è che l'inizio: la realtà onirica diviene visione “vera” e simboli percorrono le trame dei vari capitoli, rendendoli interdipendenti tra loro: l'ape austriaca che, muovendosi a scatti con un ritmo metallico, si posa sulla tela appena conclusa di Truppe di rincalzo sotto la pioggia è la stessa che accompagna il giovane poeta Arturo Onofri tra i colpi delle granate della Grande Guerra, nella quale “la voce di Evola è a favore degli Imperi Centrali: l'Austria e la Germania” (p. 26).

Attraversati gli scandalismi e i manifesti futuristi, percorso il nichilismo dadaistico, il cammino del cinabro evoliano procede: “In un dorato pomeriggio autunnale, in Roma, nel 1921, alle ore 17, infine Evola capì. Aveva da poco smesso di dipingere. Quell'esperienza artistica era giunta alla fine, nel senso che le sue potenzialità creative si erano esaurite: tutto quel che poteva fare attraverso i quadri per procedere nella sua ricerca interiore, ebbene, lo aveva fatto” (p. 28). Alle 17.15, Evola si libera del suo doppio dadaista per procedere oltre, dopo l'abisso delle avanguardie per poi risalire, senza incappare nell'impasse dell'inconscio freudiano surrealista e della scrittura automatica. Via, verso Ur e Krur, La Torre e la sua rivolta contro la tirannia della modernità.

Come già detto, il percorso tracciato da Henriet non si arresta all'esaurimento della fase artistica, ma procede, percorrendo tutte le sue fasi fondamentali. Un altro frammento di realtà, trasfigurato e sublimato nelle serpentine dell'ermetismo pittorico del futuro filosofo: il XXI aprile 1927, dies natalis Romae, coglie il Nostro affacciato alla finestra di una torre – non d'avorio ma “di nera ossidiana” – mentre assiste da lontano ad una parata. “Tutta l'Urbe è in festa, ma Ea preferisce restarsene da solo, nel proprio salone. Per lui, in fondo, il fascismo è troppo plebeo” (p. 41). Ed ecco comparire, a cavallo di farfalle che sorvolano la Città Eterna, gli altri membri del Gruppo di Ur, quasi a formare una delle loro catene nei cieli liberi sopra la città, sopra il mondo intero, al di sopra della storia. Henriet rievoca qui le vicende legate alla celebre Grande Orma (episodio con retroscena ancora da scoprire, come testimonia il recente ottimo libro di Fabrizio Giorgio, Roma Renovata Resurgat, Settimo Sigillo, Roma 2012): “Nel 1923 hanno donato al capo del Governo un fascio formato da un'ascia di bronzo che proviene da una misteriosa e antica tomba etrusca, e dodici verghe di betulla, legate con strisce di cuoio rosso” (p. 42). La Tradizione porge la mano alla Storia, aspettando una risposta. Sono anni cruciali, questi, nei quali in poche ore possono decidersi non solo i destini di un decennio ma le sorti di un'intera civiltà. Riuscirà il fascismo a farsi depositario del proprio destino romano? Sono in molti a chiederselo. Attonito, Evola assiste al Concordato, al vanificarsi di un sogno, “ancora una volta è solo”, “uno spirito libero e aristocratico, fuori tempo e fuori luogo” (p. 42): in una parola, inattuale, in senso nietzschiano. Così, mentre le piazze gorgogliano dei singhiozzi gioiosi di quegli stessi che all'indomani del fallimento del fascismo prepareranno le forche e accenderanno i roghi, Evola se ne rimane in disparte. Alla fine della scena, una camicia nera emerge dal buio della notte, gli si avvicina, pronunciando, con una voce d'acciaio, queste parole: Il Natale romano è finito, barone. Da ora in poi, il destino degli eventi a venire è già scritto.

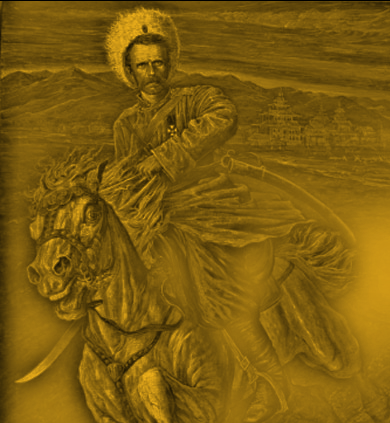

Ed ecco la Seconda Guerra Mondiale, la guerra civile europea, l'inizio di un nuovo ciclo, sul quale già pesa il presagio dell'ipoteca. Il viaggio nella prima mostra evoliana del XXI secolo continua, tra anticipazioni e retrospettive. Nella camera magica, Evola vede quello che sarà il suo destino: “In piedi, tra le rovine fumanti d'Europa, al termine della Seconda Guerra Mondiale, si aggira per Vienna. 1945. Una visione di morte. La tigre diventa metallo: la carne si solidifica” (p. 47). Sbalzato contro un muro dallo spostamento d'aria causato da una bomba, trascorrerà il resto della sua esistenza affetto da una semiparalisi degli arti inferiori.

Il Barone è costretto su una carrozzella, novella tigre d'acciaio. Il secondo dopoguerra. Con una certa ironia (che non sarebbe dispiaciuta al Barone ma che forse non piacerà a certi “evolomani”, come scrive Gianfranco de Turris nella sua Introduzione) l'autore immagina che proprio a cavallo di questa nuova tigre il Nostro continui la sua battaglia. Inizia a dipingere copie dei suoi dipinti degli anni Venti, dispersi (ossia venduti) durante la celebre retrospettiva del 1963. Eppure, anche in questa nuova situazione, si profilano nuovi attacchi, nuove situazioni da superare, come i Rivoluzionari del Sesso (evidente richiamo alle dottrine di Wilhelm Reich). Ed ecco gli Anti-Veglianti, Signori dell'Occhio, che tentano di impiantare un Occhio televisivo al posto di quelli biologici, teso ad uniformare Evola al mondo moderno, alla tirannia dell'homo oeconomicus e dei Mezzi di Comunicazione di Massa, che al terzo occhio ne sostituiscono uno artefatto e anestetizzante, che riduce l'uomo a Uomo Banale e Mediocre. Ma Evola riesce a fuggire.

Ennesima anticipazione: questa volta in alta montagna, molti passi sul mare, ancora di più sull'uomo, come aveva scritto Nietzsche. Eccolo assistere in anteprima alla deposizione delle sue ceneri sul ghiacciaio del Lys. Allucinato da uno dei suoi quadri, Evola ha una visione di quel che sarà: “Il vento spira freddo, la luce del sole è netta, brillante. Il silenzio domina tutto. I ghiacci eterni scintillano. V'è una gran quiete, tesa, nervosamente carica di energia in potenza” (p. 36). Per disposizione testamentaria, il suo corpo viene cremato, le ceneri disperse sulle Alpi. Così vive la propria morte Ea, Jagla, il Barone – nel libro non la conoscerà mai più, fisicamente. Si addormenterà, sognando un'intervista realizzata per la televisione svizzera nei primi anni Ottanta. Il “diamante pazzo” che scaglia bagliori qua e là, illuminando ora l'uno ora l'altro frammento del firmamento occidentale, è seduto “sulla sua tigre a dondolo, in legno aromatico e dai colori smaltati in vernice brillante” (p. 67). Certo, pensa Evola beffardamente, parlare di certe cose nel mondo moderno, servendosi dei media (chissà che avrebbe pensato oggi, nell'epoca della Rete...), non è certo ottimale. Comincia a dubitare della sua decisione di concedere l'intervista. Questa posizione a cavallo della tigre comincia ad apparirgli un po' scomoda. Risponde alle domande, ribadendo le proprie posizioni di fronte al neospiritualismo, alle censure di certe cricche intellettuali e via dicendo. Ma la realtà del suo sogno inizia a sfaldarsi. Il suo pellegrinaggio nel kali-yuga lo ha prosciugato: “Evola non immaginava che sarebbe stato così difficile. Il sogno della realtà è diventato un caos indistinto di colori acidi” (p. 71). Abbandonandosi al disfacimento dell'architettura onirica nella quale si vive morente, si spegne, “gli occhi accecati da una radianza aurea intensissima” (Ibid.). Il confine tra sogno e realtà è disciolto per sempre: Evola, che aveva visto la propria fine vivente in uno dei suoi quadri, ora vive la propria morte in un sogno.

Scritto con un registro stilistico iperbolico ed evocativo, il libro di Henriet, come messo a fuoco da de Turris nella già citata introduzione, non è però solo una rassegna di queste esperienze, quanto piuttosto una ricognizione sul senso dell'interezza del sentiero del cinabro, portato a stadio mercuriale durante il corso della vita del Nostro. Come è noto, a partire peraltro dalla sua biografia spirituale, il Cammino del cinabro, Evola diede pochissimo spazio a dettagli di ordine personale, preferendo ad essi un'impersonalità attiva fatta di testimonianze ed opere. In uno degli ultimi capitoli, Henriet scrive: “Della vita privata di Ea si sapeva poco, era come se non gli fosse accaduto nulla di personale. Egli era semplicemente il mezzo, uno dei possibili, attraverso i quali l'Io originario – la Genitrice dell'Universo, una delle Madri di Goethe – operava su quel piano della realtà, governato dalle regole del tempo e dello spazio” (p. 62). In questo può risolversi l'esercizio della prassi tradizionale, per come interpretata dal filosofo romano. Una azione nella quale l'essere un mezzo di istanze sovraindididuali non annichilisce l'Io, come vorrebbero invece talune spiritualità fideistiche sempre avversate da Evola, ma lo potenzia, finanche a realizzarlo in tutti i suoi molteplici stati. Un monito, questo, quanto mai attuale, tanto per accedere all'universo evoliano quanto per attraversare illesi il mondo moderno, sopravvivendo alle sue chimere e fascinazioni.

Alberto Henriet, L'uomo che cavalcava la tigre. Il viaggio esoterico del barone Julius. Presentazione di Gianfranco de Turris, Gruppo Editoriale Tabula Fati, Chieti 2012, pp. 80, Euro 8,00.

titolo: L'uomo che cavalcava la tigre. Il viaggio esoterico del barone Julius

autore/curatore: Andrea Scarabelli

fonte: Fondazione Julius Evola

tratto da: http://www.fondazionejuliusevola.it/Documenti/recensioneScarabelli_Sito.doc

lingua: italiano

data di pubblicazione su juliusevola.it: 10/06/2013

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : julius evola, evola, traditionalisme, tradition, italie, livre, philosophie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 10 novembre 2013

LE JAPON MEDIEVAL : LE MONDE A L'ENVERS...

Rémy Valat

Le Japon médiéval est méconnu en France et grande est la tentation de le comparer à la période féodale européenne, tant il est vrai que nombreuses similitudes peuvent être constatées entre ces deux modèles de sociétés pourtant situées aux deux extrémités du continent eurasiatique.

Ce rapprochement, plutôt cette interprétation, est notamment le produit de l'historiographie nippone : le terme de « Moyen-Âge » apparaît pour la première fois sous la plume de l'historien Hara Katsurô, auteur d'une Histoire du Moyen-Âge parue en 1906. Pour lui, cette période instable et transitoire se situe entre deux sociétés stabilisées : Heian (794-1185) et Edo (1603-1867). Ce néologisme s'imposa sur l'appellation originelle des contemporains (l'« âge des guerriers »). Il est vrai que l'émiettement de l'autorité, la captation du pouvoir politique par les hommes d'armes, l'apparition de liens de vassalité, la naissance de seigneuries foncières, le phénomène monastique, l'émergence d'oppositions pour les libertés communales, l'essor économique et démographique, le développement d'une bourgeoisie urbaine favorisent le rapprochement (en dépit d'un décalage chronologique dans le développement de ce type de société au Japon).

À l'heure de la montée en puissance du nationalisme et d'une politique coloniale dynamique, le livre Hara Katsurô écrit dans le contexte de la victorieuse guerre russo-japonaise souhaite interpréter le « Moyen-Âge » comme une période fondatrice, d'affirmation de l'identité nationale, similaire à la période féodale européenne et où auraient dominé les valeurs martiales : ce discours visait à démontrer une « supériorité intrinsèque » des industries et des armées japonaises et à légitimer l'expansion coloniale en Asie. Une idée similaire sous-tend le livre de Nitobe Inazo, Le Bushidô : l'âme du Japon, ouvrage paru en 1910 et très prisé des artistes martiaux ou amoureux de la chose militaire qui tombent dans le piège tendu par l'auteur...

Le travail de Pierre-François Souyri a été de « remettre à l'endroit » l'histoire médiévale nippone et de corriger cette interprétation... L'histoire du Japon médiéval : le monde à l'envers, paru cette année au éditions Perrin-Tempus , paru en août 2013, est une réédition de l'ouvrage Monde à l'envers, la dynamique de la société médiévale, publié par la très regrettée maison d'éditions Maisonneuve et Larose en 1998. Le contenu de ce livre offre une forte similitude avec la 3ème partie (consacrée au Moyen-Âge) du même auteur de L'histoire du Japon des origines à nos jours, paru chez Hermann en 2009 avec cependant un intéressant chapitre additionnel comparant les sociétés médiévales européennes et nippones (chapitre 13. De la comparaison entre les sociétés médiévales d'Occident et du Japon). L'auteur, Pierre-François Souyri, professeur à l'université de Genève et ancien directeur la Maison Franco-japonaise de Tôkyô, est un spécialiste incontesté du sujet : on lui doit notamment la traduction du livre de Katsumata Shizuo relatif aux coalitions et ligues de la période médiévale (Ikki. Coalitions, ligues et révoltes dans le Japon d'autrefois, CNRS éditions, 2011). Enfin, le livre se fonde sur une abondante documentation et sources primaires japonaises, soigneusement confrontées et analysées.

L'« âge des guerriers » est une période foisonnante, aussi violente que créatrice. Après la victoire du clan des Minamoto sur celui des Taira (1185), un premier pouvoir militaire central s'impose : le shôgunat de Kamakura (1185-1333). Minamoto Yoritomo obtient de l'empereur le titre de sei tai shôgun (征夷大将軍 ), c'est-à-dire de « général en chef chargé de la pacification des barbares ». Mais, à la mort de ce dernier en 1199, le pouvoir réel échappe au fils du défunt (Minamoto Yoriie) ; le pouvoir est confié à un conseil de vassaux que domine le clan des Hôjô, clan dont l'influence ne cesse de s'étendre et de s'affirmer. Le shôgunat de Kamakura est resté dans toutes les mémoires en raison du célèbre épisode des tentatives d'invasions mongoles, dispersées par un typhon, un « vent divin » (1274 et 1281)... Ce long XIIIe siècle est propice à une intense réflexion spirituelle et à la contestation religieuse : des réformes sont initiées par les prédicateurs Hônen, Shinran, Nichiren et les maîtres zen, Eisai et Dôgen.

L'échec des invasions mongoles aussi est le prélude à la chute du clan Hôjô, incapable de récompenser les guerriers qui ont contribué aussi bien financièrement que par leur engagement personnel à la victoire. Une coalition de malcontents appuie l'empereur Go Daigo qui réalise une éphémère et autoritaire restauration impériale (restauration Kemmu, 1333-1336). L'empire se scinde ensuite en deux entités rivales (les cours du Nord et du Sud) ; la guerre civile fait rage, mais celle-ci profite au clan des Ashigaka, partisan de la cours kyôtoîte du Nord : en 1338, Ashikaga Takauji reprend la fonction de shôgun. Après la défaite de la « cour sudiste » en 1392 : les Ashikaga deviennent les maîtres du pays. La période Muromachi (1392-vers 1490) est entrecoupée de crises politiques et sociales sur fond d'essor économique (développement d'une économie commerciale avec échanges monétaires et premières tentatives d'accumulation de capital). C'est le « monde à l'envers » (gekokujô, 下剋上) : les mouvements civils ou religieux d'autonomie rurale et urbaine et l'irrésistible ascension de la classe des guerriers débouchent sur un affrontement général, dont l'enjeu devient l'unification du pays. Oda Nabunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi et Tokugawa Ieyasu la réaliseront au prix d'une longue guerre contre les forces politiques centrifuges, conflit dont Ieyasu sort vainqueur en créant la dernière dynastie de shôgun en 1603.

Le monde à l'envers c'est surtout celui des petites gens avides d'autonomie et d'ascension sociales dans un contexte de mutation économique et sociale, mais aussi celui d'un monde flottant qui a influencé les modes de vie et la culture nippones (les parias, appelés notamment kawaramono, 河原者). Les guerriers, acteurs principaux de la période médiévale et en particulier ceux de l'est de l'île d'Honshû, s'organisent sur une base familiale et clanique et créent des liens de vassalité (bushidan, 武士団). Ils sont issus de lignées de déclassés de la cour (voire de princes de la famille impériale, c'est le cas du lignage des Taira et des Minamoto qui font s'affronter entre 1180 et 1185) venu tenter leur chance loin de la capitale ou bien proviennent du milieu des paysans aisés et de la petite notabilité rurale. Ces hommes sont très attachés à leur terroir et défendent les intérêts des travailleurs de la terre, desquels ils se désolidarisent progressivement pour les dominer. Ces militaires en quête d'ascension sociale et de récompenses sont loin de la représentation conventionnelle du serviteur fidèle et loyal façonnée à l'époque d'Edo. Leur engagement est conditionné par les revenus de leurs terres : la période des récoltes (et de la perception des redevances) venue, le souffle d'un vent politique ou militaire contraire, ces hommes s'évaporent ou changent de camp. Leurs prouesses militaires, relatées dans les « dits » servent autant à bâtir une réputation qu'à ouvrir droit à récompenses... Si la bravoure du guerrier japonais médiéval ne peut être remis en question, leur éthique et leurs motivations étaient cependant plus prosaïques...

Histoire du Japon médiéval, le monde à l'envers, de Pierre-François Souyri, aux éditions Perrin-Tempus, août 2013, 522 p.

00:09 Publié dans Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : traditioon, traditions, traditionalisme, japon, asie, samourai |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 06 novembre 2013

Un texte du 19ème siècle sur la formation du Samouraï déchiffré

Un texte du 19ème siècle sur la formation du Samouraï déchiffré

Ex: http://www.zejournal.mobi

Un texte d'entraînement, utilisé par une école d'arts martiaux pour enseigner aux membres de la classe bushi (samurai ou samouraï), a été déchiffré. Il révèle les règles que les samouraïs étaient censés suivre et ce qu'il fallait faire pour devenir un véritable maître épéiste.

Le texte est appelé Bugei no jo, ce qui signifie "Introduction aux arts martiaux" et est daté de la 15e année de Tenpo (1844).

Écrit pour les étudiants samouraïs sur le point d'apprendre le Takenouchi-Ryu, un système d'arts martiaux , il devait les préparer pour les défis qui les attendaient.

Une partie du texte traduit donne ceci: "Ces techniques de l'épée, nées à l'âge des dieux, ont été prononcées par la transmission divine. Elles forment une tradition vénérée de par le monde, mais sa magnificence se manifeste seulement quand on a pris connaissance (...). Quand [la connaissance] est arrivée à maturité, l'esprit oublie la main, la main oublie l'épée," un niveau de compétence que peu obtiennent et qui requiert un esprit calme.

Le texte comprend des citations écrites par les anciens maîtres militaires chinois et est écrit dans un style Kanbun formel: un système qui combine des éléments de l'écriture japonaise et chinoise.

Le texte a été publié à l'origine par des chercheurs en 1982, dans sa langue originale, dans un volume de l'ouvrage "Nihon Budo Taikei." Récemment, il a été partiellement traduit en anglais et analysé par Balázs Szabó, du département d'études japonaises de l'Université Eötvös Loránd à Budapest, en Hongrie.

La traduction et l'analyse sont décrites dans la dernière édition de la revue Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae.

Parmi ses nombreux enseignements, le texte dit aux élèves de montrer une grande discipline et de ne pas craindre le nombre d'ennemis. "(...) c'est comme franchir la porte d'où nous voyons l'ennemi, même nombreux, nous les voyons comme quelques uns, donc aucune crainte ne s'éveille, et nous triomphons alors que le combat vient à peine de commencer", citation d'un enseignement Sur les Sept Classiques Militaires de la Chine ancienne.

Le dernier siècle des samouraïs

En 1844, seuls les membres de la classe Samouraï étaient autorisés à recevoir une formation d'arts martiaux. Szabó explique que cette classe était strictement héréditaire et qu'il y avait peu de possibilités pour les non-samurai d'y adhérer.

Les étudiants Samurai, dans la plupart des cas, auraient participé à plusieurs écoles d'arts martiaux et, en outre, auraient appris "l'écriture chinoise, les classiques confucéens et la poésie dans les écoles du domaine ou des écoles privées", a expliqué Szabó.

Les étudiants qui commencent leur formation de Takenouchi-ryu en 1844 ne réalisaient pas qu'ils vivaient à une époque où le Japon était sur ??le point de subir d'énormes changements.

Pendant deux siècles, il y a eu des restrictions sévères sur les Occidentaux entrant au Japon. Cela a pris fin en 1853 quand le commodore américain Matthew Perry est entré dans la baie de Tokyo avec une flotte et a exigé que le Japon signe un traité avec les États-Unis.

Dans les deux décennies qui ont suivi, une série d'événements et de guerres ont éclaté qui on vu la chute du Japon Shogun, la montée d'un nouveau Japon moderne et, finalement, la fin de la classe des Samouraïs.

Les règles Samurai.

Le texte qui vient d'être traduit énonce 12 règles que les membres de l'école de Takenouchi-ryu étaient censés suivre.

Certaines d'entre elles, dont "Ne quittez pas le chemin de l'honneur !" et "Ne commettez pas de turpitude !" étaient des règles éthiques que les samouraïs étaient censés suivre.

Une règle notable, "Ne laissez pas les enseignements de l'école s'échapper !" a été créé pour protéger les techniques secrètes d'arts martiaux de l'école et à aider les élèves s'ils devaient se trouver au milieu d'un combat.

"Pour une école d'arts martiaux ... afin d'être attrayante, il était nécessaire de disposer de techniques spéciales permettant au combattant d'être efficace même contre un adversaire beaucoup plus fort. Ces techniques sophistiquées faisaient la fierté de l'école et étaient gardées secrètes, car leur fuite aurait causé une perte aussi bien économique que de prestige", écrit Szabó.

Deux autres règles, peut-être plus surprenantes, précisent que les étudiants "ne se concurrencent pas !" et "Ne racontent pas de mauvaises choses sur d'autres écoles !".

Les occidentaux modernes ont une vision populaire des samouraïs s'affrontant régulièrement, mais en 1844, ils n'étaient pas autorisés à se battre entre eux.

Le shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi (1646-1709) avait placé une interdiction sur les duels d'arts martiaux et a même réécrit le code que le samouraï devait suivre, en l'adaptant pour une période de paix relative. "L'apprentissage et la compétence militaire, la loyauté et la piété filiale, doit être promue, et les règles de la bienséance doivent être exécutées correctement", expliquait le shogun (traduction du livre "Études sur l'histoire intellectuelle du Japon des Tokugawa," par Masao Maruyama, Princeton University Press, 1974).

Les compétences secrètes.

Le texte propose seulement un faible aperçu des techniques secrètes que les élèves auraient appris à cette école, en séparant les descriptions en deux parties appelées "secrets les plus profonds du combat" et "secrets les plus profonds de l'escrime."

Une partie des techniques secrètes de combat à mains nues est appelé Shinsei no daiji, ce qui se traduit par "techniques divines", indiquant que ces techniques étaient considérées comme les plus puissantes.

Curieusement, une section de techniques secrètes d'escrime est répertoriée comme ?ry?ken, également connu sous le nom IJU ichinin, ce qui signifie "ceux considérés être accordés à une personne" - dans ce cas, l'héritier du directeur.

Le manque de détails décrivant ces techniques dans des cas pratiques n'est pas surprenant pour Szabó. Les directeurs avaient des raisons pour utiliser un langage crypté et l'art du secret.

Non seulement ils protégeaient le prestige de l'école, et les chances des élèves dans un combat, mais ils contribuaient à "maintenir une atmosphère mystique autour de l'école," quelque chose d'important pour un peuple qui tenait l'étude des arts martiaux en haute estime.

- Source : Les Découvertes Archéologique

00:05 Publié dans Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : tradition, traditions, traditionalisme, japon, samourai, asie, castes guerrières |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 30 octobre 2013

Il diritto negato alla tradizione

Dopo quello che abbiamo definito il falso mito del diritto alla cultura, forse suscitando l’orrore di qualcuno, ci occupiamo dell’autentico mito di un diritto negato, un diritto che può avere diversi nomi ma che qui definiremo, semplicemente, diritto alla tradizione.

Hic et nunc il termine tradizione viene assunto nella sua pura semplicità che lo rimanda, direttamente, al patrimonio simbolico e culturale trasmesso di generazione in generazione. L’Italia è un Paese di tradizioni interrotte, di culture locali che in forza di una serie di con-cause hanno cessato di essere trasmesse di Padre in Figlio, di Madre in Figlia. I tratti comuni di queste culture erano l’oralità e il dialetto (lingue sì, ma non codificate e dunque legate al vitalismo delle comunutà parlanti), e tutte manifestavano sia lo scopo di produrre la massima autonomia del singolo nella sfera produttiva, sia la qualità che, curiosamente ma nemmeno troppo, Alan W. Watts assegna al Taoismo, l’antico sistema metafisico, etico e infine religioso della Cina, nel suo celebre lavoro “Il Tao. La via dell’acqua che scorre”: “L’antica filosofia del Tao segue in modo abile ed intelligente il corso, la corrente e le venature dei fenomeni naturali, considerando la vita umana come un’integrale caratteristica del processo del mondo”. Diversa, quindi, dalla scienza occidentale che “ha posto l’accento sull’atteggiamento di oggettività – un freddo, calcolatore e distaccato atteggiamento per mezzo del quale appare che i fenomeni naturali, incluso l’organismo umano, non sono altro che meccanismi”.

Le tradizioni interrotte d’Italia erano culture in cui la sapienza si scambiava con la saggezza, in un gioco caleidoscopico di empirismo, produzione fiabesca, pragmatismo, originalità. Erano, anche, confini difficilmente superabili dal Potere, persino da quello religioso che doveva, sovente, scendere a patti con le tradizioni pre-esistenti e con le credenze ataviche delle comunità. Erano veri e propri anticorpi sociali alle pretese di “dominio” che le istituzioni del tempo coltivavano nei confronti dei propri sottoposti, emblemi di un’alterità che tracciava una demarcazione netta tra chi esercitava il potere e chi poteva ribellarvisi.

Perché e come queste tradizioni sono state interrotte e rescisse? Chi o cosa minacciavano concretamente?

La loro eliminazione era naturaliter funzionale all’affermazione dello Stato nazionale, di quella moderna unità linguistica e storica che si affermò – ancorché incompiutamente – attraverso la scuola, la guerra e, infine, attraverso la televisione, lo strumento di comunicazione, manipolazione e persuasione più potente che sia mai apparso sulla scena della storia.

Il 9 dicembre 1973, dalle colonne del Corriere della Sera, Pier Paolo Pasolini lanciava uno storico monito dal carattere profetico: “Nessun centralismo fascista è riuscito a fare ciò che ha fatto il centralismo della civiltà dei consumi. Il fascismo proponeva un modello, reazionario e monumentale, che però restava lettera morta. Le varie culture particolari (contadine, sottoproletarie, operaie) continuavano imperturbabili a uniformarsi ai loro antichi modelli: la repressione si limitava ad ottenere la loro adesione a parole. Oggi, al contrario, l’adesione ai modelli imposti dal Centro, è tale e incondizionata”. L’articolo prosegue: “Per mezzo della televisione, il Centro ha assimilato a sé l’intero paese che era così storicamente differenziato e ricco di culture originali. Ha cominciato un’opera di omologazione distruttrice di ogni autenticità e concretezza. Ha imposto cioè – come dicevo – i suoi modelli: che sono i modelli voluti dalla nuova industrializzazione, la quale non si accontenta più di un “uomo che consuma”, ma pretende che non siano concepibili altre ideologie che quella del consumo”.

La soppressione delle culture popolari era anche un atavico obiettivo di coloro che professavano l’affermazione definitiva di una nuova fede, quella nella scienza. Oggi sappiamo, o dovremmo sapere, che nessuna verità scientifica è inconfutabile, che nulla di quanto è scientifico può non essere superato. Ciononostante, attribuiamo alla scienza un valore dogmatico. Ciononostante, abbiamo elevato la scienza a nuova religione, con i suoi riti, i suoi sacerdoti e i suoi anatemi, pagando questo scotto con la perdita di bio-diversità culturale, la disumanizzazione del lavoro, l’iper-medicalizzazione, il costante tentativo di superamento dell’ultima etica possibile, l’etica della vita o bio-etica.

Attraverso il mito della sapere scientifico, passate le co-scienze per la “spada” della televisione , siamo giunti a una nuova ortodossia del pensiero che ci avvolge da ogni lato, offrendoci risposte ma risparmiandoci domande: un nuovo totalitarismo a cui le tradizioni locali avrebbero contrapposto un anarco-liberismo del pensiero, basato sulla trasmissione “selvatica” di ciò che agli invidui spetta loro non in virtù di un inconsistente diritto sociale alla redistribuzione del reddito ma di un diritto naturale alla trasmissione di simboli – mai davvero assimilati alla cultura ufficiale, nemmeno da quella religiosa – e al loro recepimento.

Il processo di nazionalizzazione e costruzione della nazione, giustificato da un presunto “riscatto” delle masse dall’ignoranza da cui sarebbero state afflitte, si manifesta oggi come un processo di giustificazione dello Stato e dei processi persuasivi di potere, manipolazione e controllo sulle coscienze. Quanto poco efficace sia questo processo nel creare uomini liberi, lo testimonia l’analfabetismo di ritorno a cui la maggior parte della popolazione, dopo essere stata privata della sua iniziazione al sapere locale, viene condannata. Ma siamo sicuri che si tratti davvero di analfabetismo di ritorno, o forse l’unico alfabetismo che interessa alle istituzioni scolastiche è quello di instillare, nelle anime giovani, niente più che “Miti”, mere credenze e principi prodotti sotto l’egida della certezza scientifica e certificati dal complesso militare-industriale?

Può una società massificata, in cui il sapere e la cultura delle masse non sono argini all’esercizio del potere ma sue dirette emanazioni, essere davvero una società di uomini liberi?

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie, Terroirs et racines, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : tradition, pier paolo pasolini, pasolini, heimat, terroir, racines, italie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 28 octobre 2013

Remplacer les fêtes chrétiennes par Yom Kippour et l’Aïd

Remplacer les fêtes chrétiennes par Yom Kippour et l’Aïd : 80% des français disent non

Ex: http://zejournal.mobi

La France est un pays de culture et de tradition catholique, sous un régime républicain et démocratique. Je mérite sûrement la guillotine, bien affûtée, de la libre parole républicaine pour ces propos nauséabonds. Plus besoin de guillotine, elle est désormais implantée directement dans les âmes et consciences, et ce, dès l’enfance, grâce à la « ligne Buisson » de la laïcité de Vincent Peillon, et la pastorale républicaine qu’il met en place à l’école. Prochaine étape : la suppression des fêtes chrétiennes. On y vient très vite, on y est : une «sociologue» convertie à l’islam, membre de l’Observatoire de la laïcité, vient de proposer de remplacer deux fêtes chrétiennes par une fête juive et une fête musulmane…

L’Observatoire de la laïcité, organisme étatique dépendant directement du Premier Ministre de la République, a été créé en 2007, sûrement pour contrer, au moins en tant que « poudre aux yeux », la problématique du culte musulman au cœur du quotidien des citoyens. Aujourd’hui, au main des socialistes, cet observatoire devient très dangereux – comme pour nombre de lois prises sous la droite, que la droite applaudissait, et qu’elle se prend aujourd’hui en pleine poire. Dounia Bouzar, qui a été nommée dimanche à l’observatoire de la laïcité par le Premier ministre, qui est une anthropologue spécialiste du fait religieux, propose, dans un entretien à Challenges, de remplacer deux fêtes chrétiennes (au choix) par Yom Kippour et l’Aïd…

Cette experte, donc, nous informe que « la France a montré l’exemple de la laïcité au monde en instaurant la première la liberté de conscience » [sauf pour les pharmaciens ou les maires - ajout de l’ami Michel Janva]. Liberté de conscience, soit dit en passant, qui existait dès la grèce antique, sinon avant, et qui trouve d’ailleurs dans la théologie médiévale des arguments étayés. Il suffit d’ouvrir saint Thomas d’Aquin pour comprendre que l’homme créé à l’image de Dieu veut dire qu’il en est l’image en tant qu’il est libre, comme Lui, de ses actes et de ses pensées.

À la fin de cet entretien sur les cas posés par la problématique musulmane au travail et dans les cantines, le journaliste lui demande quand même s’il faut ajouter deux fêtes en plus ; et notre experte en laïcité de répondre : « le clergé y a longtemps été opposé mais il a évolué et n’y est plus hostile car il y a beaucoup de fêtes chrétiennes ». Il a « évolué ». Comprenez : le clergé sort enfin des siècles sombres, moyenâgeux et lugubres dans lesquels il était enfermé, et il en sort sous l’impulsion du « sens de l’histoire », qui file en droite ligne vers le Grand Soir socialiste, le paradis terrestre, enfin délivré de toute croyance et de toute vérité des cieux.

Et, comme toute histoire a ses prophètes, je vous en offre deux qui avait tout prévu : le prophète Jacques Attali disait déjà, en février 2003, qu’« il convient (…) d’enlever de notre société laïque les derniers restes de ses désignations d’origine religieuse. »… Pas mieux que l’autre prophète, Vincent Peillon, qui affirmait dans une vidéo de 2005 qu’il fallait détruire la religion catholique, pour imposer sa « religion laïque et républicaine » (l’équivalent, chez lui, de « socialiste »). L’enjeu, dit Peillon, est « de forger une religion qui soit non seulement, plus religieuse que le catholicisme dominant, mais qui ait davantage de force, de séduction, de persuasion et d’adhésion, que lui. ». La chose est claire ? Il parle exclusivement du catholicisme, et non des autres religions : la rivalité mimétique de la République et de l’Église, dès la Révolution française – qui n’est pas terminée, rappelons-le, est un combat, une guerre des religions qui est strictement polarisée par ces deux-là. L’islam est là de surcroit, comme un allié objectif de la République dans ce combat, quoi qu’on puisse en penser.

L’objectif est donc clairement de bâtir une société anti-chrétienne. Pourquoi autant de pessimisme et de fermeture, me direz-vous : l’espace social n’est-il pas le lieu de la « cohabitation des différences » et du « multiculturalisme » ? Oui, très bien, et alors il ne resterait qu’à nous, chrétiens, de convaincre les autres – sans pouvoir trop en parler publiquement, en se cachant dans les caves, en évitant d’être trop « visible », se faisant tout petit, et en n’intervenant surout pas dans les débats publics. Comment voulez qu’une lampe éclaire le monde si elle est placée sous la table ? Comment voulez-vous que l’avenir de la France se batisse sans son passé ? Comment voulez-vous construire une maison sans ses fondations ? Point n’est besoin de fondation, d’historicité et de continuité, puisque, dans leurs esprit peilloniens, tout commence par la Révolution, et tout finira avec la Révolution achevée : une Révolution, selon le grand-maître Peillon, qui est « un événement religieux », une « nouvelle genèse » un « nouveau commencement du monde », une « nouvelle espérance », une « incarnation théologico-politique », qu’il faut porter à son terme, à savoir : « la transformation socialiste et progressiste de la société toute entière » (La révolution française n’est pas terminée, p. 195).

« c’est encore une religion, sinon une certaine forme de religiosité, qui est encore à l’œuvre dans ce médiocre spectacle dit laïque »

Que les musulmans (et les juifs) ne se réjouissent donc pas trop vite : ils sont aujourd’hui les idiots utiles de la République, plus que les alliés objectifs. Une République qui se sert de l’islam, à sa droite, et du « multiculturalisme », à sa gauche, pour imposer sa propre religion, mais qui veut les fendre toutes, et, au premier chef, l’Église, dont elle est depuis le début la copie mondaine et le décalque horizontal. Elle veut et n’existe que pour s’imposer elle-même comme religiosité, et, grâce à Vincent Peillon, dont on peut reconnaître, au moins, la franchise, cela est rendu public. Oui il faudra répandre la bonne parole, selon le rapport de l’Observatoire de la laïcité remis le 25 juin au Premier ministre : « favoriser la diffusion de guides de la laïcité dans les municipalités, hopitaux, maternité, entreprises privées », « inventer une charte laïque » ou encore « enseigner la morale laïque à l’école » (p. 4), tout cela en s’appuyant « sur la lutte contre toutes les discriminations économiques, sociales, urbaines ». L’homme nouveau, républicain et socialiste, ouvert à tout sans n’être à rien, subissant toutes les cultures du monde sans avoir le droit à la sienne, étant partout « chez autrui » plutôt que « chez lui », sera lisse et livide, sans visage et sans porosité, homme relatif et relativiste, où tout se vaut, dans une angoisse permanente et suffoquante. Rien à quoi se rattacher. Sinon à la République laïque et socialiste qui est là, et qui tend les bras.

Oui, c’est encore une religion, sinon une certaine forme de religiosité, qui est encore à l’œuvre dans ce médiocre spectacle dit « laïque ». Les petits rituels narcissiques, ludiques ou névrotiques de l’homo festivus sont désormais les grandes-messes du monde post-moderne, avec leurs prêtres, leurs thuriféraires, leurs porte-croix, leurs fêtes de Bacchus, leurs processions infâmes et leurs vêpres télévisuelles débilisantes. Et les sermons servis au cours de ces messes profanes sont d’une violence inouïe pour toute personne attachée à la continuité, la verticalité, la transcendance et le sérieux de la vie en société. Chrétiens, vous n’êtes pas les bienvenues : vous représentez le passé, le mur, l’échaffaud sur lequel, certes – et encore ! – on a bâti la civilisation, mais qu’il faut désormais rejeter. Place aux autres, à tout le monde, sauf à vous, déchets moyenâgeux.

- Faites donc une « croix » sur deux fêtes (au choix, mais ne rêvez pas trop pour un réferundum) :

Lundi de Pâques (21 avril pour 2014)

Jeudi de l’Ascension (29 mai pour 2014)

Lundi de Pentecôte (9 juin pour 2014)

Assomption (15 août)

Toussaint (1er novembre)

Noël (25 décembre)

Puis tournez-vous vers le dieu républicain, ses valeurs « humanistes » et immanentes, cette « transcendance flottante », cette réduction anthropologique, gage de paix, de sérénité, et surtout, comme nous le voyons tous les jours dans notre société, de beau, de vrai et de bien. Amen.

- Source : Nouvelles de France

00:07 Publié dans Actualité, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : fêtes chrétiennes, fêtes musulmanes, fêtes juives, yom kippour, aïd el kebir, traditions, actualité, fête du mouton |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 26 octobre 2013

Niet Piet maar de Sint is het probleem

Ex: http://visionairbelgie.wordpress.com/2013/10/24/piet/

Niet Piet maar de Sint is het probleem

Shepherd

Nog maar net is het stofwolkje rond mijn kritiek op het moraalridderdom van de humanitaire gemeenschap gaan liggen, of daar komt mevrouw Verene Shepherd met een heuse VN-delegatie naar Nederland (dus niet naar België of waar dan ook, maar het vrijdenkende Holland) om te onderzoeken of die Zwarte Piet wel geen vermomde Surinaamse slaaf zou kunnen zijn.

Ik kan haar bij voorbaat gerust stellen: neen, Piet is geen Creool uit de omstreken van Paramaribo, de Hollanders zullen op een andere manier met hun koloniaal verleden moeten klaarkomen.

Wel stuitend is deze nieuwe opstoot van mondiale political correctness en mensenrechterlijke haarklieverij. Niet dus tegenover het Indische kastensysteem dat nog steeds zeer verbreid is. Niet tegen de vaginale verminking wereldwijd of de kinderarbeid of de slavernij van vandaag, of de onthoofding van homo’s in

Saudi-Arabië, of het heksengeloof dat in Afrika nog altijd vrouwen en kinderen letterlijk de woestijn in drijft. Maar dus wel tegen de 6 december-folklore waar trouwens geen enkel kind nog in gelooft, al doen ze alsof om hun ouders een goed gevoel te geven.

Afbleekmiddel

Om die Hollandse pietenhysterie te duiden, ondertussen goed voor anderhalf miljoen FaceOdinbooklikes, is het goed om even de herkomst van de traditie op te frissen. En het gaat wel degelijk over kleuren. De Christelijke Klaasfiguur is gebaseerd op de legendes rond de semi-fictieve Nicolaas van Myra, een bisschop die in de 4de eeuw zou geleefd hebben, en vooral gereputeerd was als helper-in-nood voor onbemiddelde meisjes die in de prostitutie dreigen verzeild te geraken (belangrijk voor het vervolg van ons verhaal).

De Zwarte Piet is een ander verhaal, of toch weer niet. De andere, heidense Nicolaas, die men omwille van de zieltjeswinnerij vermengde met de Christelijke versie, is namelijk een gedaante van de Germaanse oppergod Wotan, een nachtridder die met zijn achtpotige Sleipnir vooral in de twaalf donkerste dagen van het jaar de buurt onveilig maakte en in ruil voor bescherming loon-in-natura eiste. Geen gever dus, maar een nemer.

Probleem voor de Christelijke iconologie: na de nuttige vermenging van de twee klazen moest dat zwart-maffieus tintje er wel terug uit, teneinde weer een proper, deugdelijk afkooksel te bekomen dat zonder problemen in de Biblioteca Sanctorum paste.

En zo ontstond het olijke duo van de bebaarde Goedheilige Man alias de gecastreerde Wotan, en zijn donkerhuidige dommekracht, in Vlaanderen nog steeds Nicodemus genoemd. In de Angelsaksische wereld heeft men alleen Santa Claus overgehouden en de Piet zedigheidshalve gedumpt. Maar het lijdt geen twijfel: Pieterman is een afsplitsel van Sinterklaas zelf, en herinnert aan de fratsen van de seksbeluste Wotanfiguur. Mevrouw Shepherd wil dus eigenlijk de geamputeerde penis (de roe) van de weldoener op sterk water. Gevaarlijk werk voor meisjes, me dunkt.

Kinderlokker en meisjesgek

Zo zijn we direct waar we moeten wezen: niet de zwartheid van Piet is het probleem, mKlaasaar wel de witter-dan-witheid van Klaas, wiens schijnvroomheid veel stof tot contestatie biedt, zonder dat men er het racisme hoeft bij te sleuren. Er zijn m.a.w. een boel redenen om dat Klaasgedoe eens door de mangel te draaien, zomaar, zonder tussenkomst van de Verenigde Naties.

Vooreerst is het stuitend dat dit icoon van de Christelijke caritas altijd al een conservatieve functie heeft gehad: hij moest de rijken aanzetten tot vrijgevigheid, in hun eigen belang, opdat de armen niet opstandig zouden worden. In de 19de eeuw zou die meritocratische achtergrond absoluut primeren: wie rijk is, heeft dat ook verdiend, en wie arm is al evenzeer. De schoentjes van de deugdzamen worden het best gevuld, omdat ze hun mérites voor deze maatschappij bewezen hebben. De anderen moeten maar wat harder werken, eventueel aangespoord door de roe.

Vandaag stoort mij vooral de permanente ongelijkheid in het Sinterklaasverhaal, de afzichtelijke commercialisering van het ritueel, en het feit dat de vrijgevigheid van de Sint, als PR-man van de speelgoedindustrie, vooral met de draagkracht van de ouderlijke beurs is verbonden. Er zij dus kinderen die gewoon niks krijgen, nada, noppes, met de impliciete motivatie dat het met hun slecht gedrag te maken heeft. Ze zijn zwart, gebrandmerkt, veel meer dan de geschminkte Piet.

Terecht geven kinderen bij dit vertoon hun eigen onschuld maar wat graag op. Het zijn uiteindelijk zij die de Sint wandelen moeten sturen, als een verhaal vol ranzige kantjes.

In een bredere context is de link tussen braafheid en giften krijgen ronduit ranzig. Het creëert afhankelijkheid én onderdanigheid. Het maakt van de Sint een usurpator en kinderlokker, wat hij eigenlijk altijd al was. Zijn voorkeur voor jonge meisjes –liefst arm, die zijn gewilliger- is een rode draad in alle Sintlegendes, ook de Christelijke. Zijn Piet hangt er niet zo maar bij, maar is een wezenlijk onderdeel van een seksuele toeëigening die als dusdanig niet herkend wordt, juist door de tweeledigheid, de scheiding tussen wit en zwart.

Dat Pietencirkus dient dus vooral om de aandacht van de handen van de goedgeilige man zelf af te leiden. Men kan er nochtans moeilijk naast kijken, als buitenstaander. Altijd weer die kindjes op schoot, hun gekrijs omdat ze voelen dat er iets niet klopt, de witte handschoenen, het gefriemel en gefezel in het rode pluche, het grote zondenboek, de geënsceneerde aankomst per boot, het debiel-vrolijke geneuzel van Bart Peeters er rond (“Piet is zwart vanwege de schoorsteen”), de verhullende witte baard waarboven toch de uitpuilende ogen hangen van Jan Decleir, de belachelijke leugens en het gemonkel van de volwassenen,- heel dat ziekelijk vertoon is een beschaving onwaardig.

Terecht geven kinderen bij dit vertoon hun eigen onschuld maar wat graag op. Het zijn uiteindelijk zij die de Sint wandelen moeten sturen. De twaalfjarige Mozart voerde de dubieuze weldoener al ten tonele in zijn opera “Bastien und Bastienne”, gebaseerd op J.J. Rousseau’s “Le devin du village”, waar hij als Colas het herderinnetje Bastienne belooft om te bemiddelen in een ruzie met haar vriendje, maar eigenlijk zichzelf opdringt als meester en inwijder.

Sint-killer

Terug naar de negritude. Op 30 juni 1960 hield Patrice Lumumba, de eerste premier van hlumumba_speechet onafhankelijke Congo, een vlijmscherpe, niet-aangekondigde speech tegen de wandaden van de Belgische weldoener en kolonisator. Koning Boudewijn zat op de eerst rij en keerde in koude razernij huiswaarts. Het heeft toen niet veel gescheeld of Zwarte Piet werd verboden in het Koninkrijk België. Gelukkig spaarde onze diepbetreurde vorst zijn roe en gaf de opdracht om Lumumba zelf te liquideren, letterlijk: hij werd geëxecuteerd en zijn lijk opgelost in zwavelzuur. De weg voor de corrupte Joseph Mobutu lag open. De rol van de CIA, de Britse geheime dienst én het Belgische hof is in deze ondertussen historisch uitgeklaard, België bood in 2002 zelfs excuses aan. Case closed… of toch niet?

De reden waarom wij in Vlaanderen geen zin hebben om Piet te bannen, is nu net zijn subversieve betekenis. Nog altijd is een zwarte bij ons niet alleen een neger, maar het wijst tegelijk op een politiek-foute paria, iemand die men geen hand geeft zonder de handen nadien te wassen. Meteen blijkt, hoe die mevrouw Shepherd eigenlijk het omgekeerde doet van wat ze voorwendt: ze elimineert de zwarte, waarna de witte als Santa Claus het rijk voor zich alleen heeft. Vreemd geval van zelfhaat.

De reden waarom wij in Vlaanderen geen zin hebben om Piet te bannen, is nu net de dreiging die hij uitstraalt tegenover de witte weldoener.

Want in hun coëxistentie zit net de mogelijkheid van een omslag. Op elk moment kan de knecht de meester van het dak gooien of in de haard verbranden, dat gevaar is inherent aan hun relatie. Het is voor mij ook het enige motief om de doodsstrijd van Nicolaas te rekken en te wachten tot hét gebeurt: het exploot van de Sint-killer. Wat Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) al omschreef als de meester-knecht-dialectiek, nl. het feit dat gezagsrelaties altijd labiel zijn omdat de meerdere de mindere nodig heeft om zijn macht te bevestigen, bevat de dreiging van een grote vadermoord. Nicodemus alias Lumumba zal dan, zelfs als hij daarvoor achteraf wordt terecht gesteld, blijven spoken in de speelgoedwinkel en de dromen van de machthebbers teisteren.

Zwarte poes

Laten we voor de rest niet vergeten dat dit een verschrikkelijke mannenzaak is, van in de oorsprong. Na de moord op Klaas lijkt me een nieuw element van verering op zijn plaats, als we in deze donkere tijden toch moeten wegdromen: geen Zwarte Piet maar Zwarte Poes, het vrouwelijk geslacht dat als een origine du monde geeft zonder te nemen, zonder voorwaarden te stellen, zonder gehoorzaamheid te eisen, genereus en absoluut. Geen pietenschmink maar echte, diepe negritude met een matriarchale inslag. Verene Shepherd zou er best voor kunnen doorgaan, als ze toch maar die bedillerige en rancuneuze zwavelzuurtoon achterwege kon laten die ze, dat weet ik heel zeker, in het blanke maatpakkenuniversum heeft opgelopen.

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : tradition, saint nicolas, père fouettard, zwarte piet, sinterkallas, pays-bas, flandre, folklore |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 18 octobre 2013

La era de la ginecocracia

por Evgueni Golovín*

Ex: http://paginatransversal.wordpress.com

Muchos libros en nuestro siglo se han escrito sobre la visión del mundo femenina, sobre la psicología femenina y el erotismo femenino. Muy pocos fueron escritos sobre los hombres. Y estos pocos estudios dejan una impresión bastante desoladora. Dos de ellos, escritos por conocidos sociólogos son especialmente sombríos: Paul Duval – “Hombres. El sexo en vías de extinción”, David Riseman – “El mito del hombre en América”. La multitud masculina de rostros variopintos no inspira optimismo. Al contemplar a la multitud masculina uno se entristece: “él”, “ello”, “ellos”… con sus discretos trajes, corbatas mal atadas… sus estereotipados movimientos y gestos están sometidos a la fatal estrategia de la más pulcra pesadilla. Tienen prisa porque “están ocupados”. ¿Ocupados en qué? En conseguir el dinero para sus hembras y los pequeños vampiros que están creciendo.

Muchos libros en nuestro siglo se han escrito sobre la visión del mundo femenina, sobre la psicología femenina y el erotismo femenino. Muy pocos fueron escritos sobre los hombres. Y estos pocos estudios dejan una impresión bastante desoladora. Dos de ellos, escritos por conocidos sociólogos son especialmente sombríos: Paul Duval – “Hombres. El sexo en vías de extinción”, David Riseman – “El mito del hombre en América”. La multitud masculina de rostros variopintos no inspira optimismo. Al contemplar a la multitud masculina uno se entristece: “él”, “ello”, “ellos”… con sus discretos trajes, corbatas mal atadas… sus estereotipados movimientos y gestos están sometidos a la fatal estrategia de la más pulcra pesadilla. Tienen prisa porque “están ocupados”. ¿Ocupados en qué? En conseguir el dinero para sus hembras y los pequeños vampiros que están creciendo.

Son cobardes y por eso les gusta juntarse en manadas. Si prescindimos de las refinadas divagaciones, la cobardía no es más que una tendencia centrípeta, deseo de encontrar un centro seguro y estable. Los hombres tienen miedo de sus propias ideas, de los bandidos, de los jefes, de “la opinión pública”, de las arañas que se chupan el dinero y que lo dan. Pero las mujeres son las que más miedo les dan. “Ella” camina multicolor y bien centrada, su pecho vibra tentadoramente… y los ansiosos ojos siguen sus curvas, y la carne se rebela dolorosamente. Su frialdad – qué desgracia, su compasión erótica – ¡qué felicidad! “Ella” es la materia formada de manera atrayente en este mundo material, en el que vivimos solo una vez, “ella” – es una idea, un ídolo, sus emergentes encantos saltan de los carteles, portadas de revistas y pantallas. “Ella” es un bien concreto. El cuerpo femenino bonito cuesta caro, tal vez más barato que “La maja desnuda” de Goya, pero hay que pagarlo. Una prostituta cobra por horas, la amante o la esposa, naturalmente, piden mucho más. El lema del matrimonio estadounidense es sex for support. Las puertas del paraíso sexual se abren con la llavecita de oro. El cuerpo masculino sin cualificar y sin muscular no vale nada.

La realidad de la civilización burguesa

Aunque nos acusen de cargar las tintas, la situación sigue siendo triste. La igualdad, emancipación, feminismo son los síntomas del creciente dominio femenino, porque la “igualdad de los sexos” no es más que otro fantasma demagógico de turno. El hombre y la mujer debido a la marcada diferencia de su orientación están luchando permanentemente de forma abierta o encubierta, y el carácter del ciclo histórico-social depende del dominio de uno u otro sexo. El hombre por naturaleza es centrípeto, se mueve de izquierda a derecha, hacia adelante, de abajo a arriba. En la mujer es todo al revés. El impulso “puramente masculino” es entregar y apartar, el impulso “puramente femenino” es quitar y conservar. Claro que se trata de impulsos muy esquemáticos, porque cada ser en mayor o menor medida es andrógino, pero está claro que de la ordenación y armonización de estos impulsos depende el bienestar del individuo en particular y de la sociedad en su conjunto, pero semejante armonía es imposible sin la activa irracionalidad del eje del ser, convencimiento intuitivo de la certeza del sistema de valores propios, la instintiva fe en lo acertado del camino propio. De otro modo la energía centrípeta o destrozará al hombre, o le obligará a buscar algún centro y punto de aplicación de sus fuerzas en el mundo exterior. Lo cual lleva a la destrucción de la individualidad y a la total pérdida de control del principio masculino propio. La energía erótica en vez de activar y templar el cuerpo, como ocurre en un organismo normal, comienza a dictar al cuerpo sus propias condiciones vitales.

La androginia del ser está provocada por la presencia femenina en la estructura psicosomática masculina. La “mujer oculta” se manifiesta en el nivel anímico y espiritual como el principio regulador que sujeta o el ideal estrellado del “cielo interior”. El hombre debe mantener la fidelidad hacia esta “bella dama”, la aventura amorosa es la búsqueda de su equivalente terrenal. En el caso contrario estará cometiendo una infidelidad cardinal, existencial.

¿Pero de qué estamos hablando?

Del amor.

La mayoría de los hombres actuales pensarán que se trata de tonterías románticas, que solo valen cuando se habla de los trovadores y caballeros. Oigan, nos dirán, todos nosotros – mujeres y hombres – vivimos en un mundo cruel y tecnificado en condiciones de lucha y competencia. Todos por igual dependemos de estas duras realidades, y en este sentido se puede hablar de la igualdad de los sexos. En cuanto a la dependencia del sexo, sabrá que en todos los tiempos ha habido obsesos y erotómanos. En efecto, las mujeres ahora juegan mucho mayor papel, pero no es suficiente para hablar de no se sabe qué “matriarcado”.

Ciertamente, no se puede hablar del “matriarcado” en la actualidad en el sentido estricto. Según Bachofen, el matriarcado es más bien un concepto jurídico, relacionado con el “derecho de las madres”. Pero perfectamente podemos ocuparnos de la ginecocracia, del dominio de la mujer, debido a la orientación eminentemente femenina de la Historia Moderna. Aquí está la definición de Bachofen:

“El ser ginecocrático es el naturalismo ordenado, el predominio de lo material, la supremacía del desarrollo físico”

J.J. Bachofen. Mutterrecht, 1926, p. 118

Nadie podrá negar el éxito de la Época Moderna en este sentido. A lo largo de los últimos dos siglos en la psicología humana se ha producido un cambio fundamental. De entrada a la naturaleza masculina le son antipáticas las categorías existenciales tales como “la propiedad” y el tiempo en el sentido de “duración”. El carácter centrípeto, explosivo del falicismo exige instantes y “segundos” que están fuera de la “duración”, que no se componen en “duración”. El destino ideal del hombre es avanzar hacia adelante, superar la pesadez terrenal, buscar y conquistar nuevos horizontes del ser, despreciando su vida, si por vida se entiende la existencia homogénea, rutinaria, prolongada en el tiempo. Los valores masculinos son el desinterés, la bondad, el honor, la interpretación celestial de la belleza. Desde este punto de vista, “Lord Jim” de Joseph Conrad es casi la última novela europea sobre un “hombre de verdad”. Jim, simple marinero, ofendido en su honor, no lo puede perdonar, ni superar. Por eso el autor le concedió el título, porque el honor es el privilegio y el valor de la nobleza. El justo y el caballero errante son los auténticos hombres.

Podrán replicar: si todos se ponen a hacer de Quijote o a hablar con los pájaros ¿en qué se convertirá la sociedad humana? Es difícil contestar a esta pregunta, pero es fácil observar en qué se convertiría dicha sociedad sin San Francisco y sin Don Quijote. Don Quijote es mucho más necesario para la sociedad que una docena de consorcios automovilísticos.

La civilización burguesa es medio civilización, es un sinsentido. Para crear la civilización hacen falta los esfuerzos conjuntos de los cuatro estamentos.

Decimos: centralización, centrípeto. Sin embargo no es nada fácil definir el concepto “centro”. El centro puede ser estático o errante, manifestado o no, se puede amarlo u odiarlo, se puede saber de él, o sospechar, o presentirlo con la sutilísima y engañosa antena de la intuición. Es posible haber vivido la vida sin tener ni idea acerca del centro de la existencia propia. Se trata del paradójico e inmóvil móvil de Aristóteles. En el centro coinciden las fuerzas centrífugas y las centrípetas. Cuando una de ellas apaga a la otra el sistema o explota o se detiene en una muerte gélida. Es evidente: lo incognoscible del centro garantiza su centralidad, porque el centro percibido y explicado siempre se arriesga a trasladarse hacia la periferia. De ahí la conclusión: el centro permanente no se puede conocer, hay que creer en él. Por eso Dios, honor, bien, belleza son centros permanentes. Es la condición principal de la actividad masculina dirigida, radial.

En los dos primeros estamentos – el sacerdotal y el de la nobleza – la actividad masculina, entendida de esta forma, domina sobre la femenina. Y únicamente con la posición normal, es decir alta, de estos estamentos se crea la civilización, en todo caso la civilización patriarcal. El burgués reconoce los valores ideales nominalmente, pero prefiere las virtudes más prácticas: el honor se sustituye por la honradez, la justicia por la decencia, el valor por el riesgo razonable. En el burgués la energía centrífuga está sometida a la centrípeta, pero el centro no se encuentra dentro de la esfera de su individualidad, el centro hay que afirmarlo en algún lugar del mundo exterior para convertirse en su satélite. La tendencia de “entregar y apartar” en este caso es posible como una maniobra táctica de la tendencia de “quitar, conservar, adquirir, aumentar”.

Después de la revolución burguesa francesa y la fundación de los estados unidos norteamericanos vino el derrumbe definitivo de la civilización patriarcal. La rebelión de La Vendée, seguramente, fue la última llamarada del fuego sagrado. En el siglo XIX el principio masculino se desperdigó por el mundo orientado hacia lo material, haciéndose notar en el dandismo, en las corrientes artísticas, en el pensamiento filosófico independiente, en las aventuras de los exploradores de los países desconocidos. Pero sus representantes, naturalmente, no podían detener el progreso positivista. La sociedad expresaba la admiración por sus libros, cuadros y hazañas, pero los veía con bastante suspicacia. Marx y Freud contribuyeron bastante al triunfo de la ginecocracia materialista. El primero proclamó la tendencia al bienestar económico como la principal fuerza motriz de la historia, mientras que el segundo expresó la duda global acerca de la salud psíquica de aquellas personas, cuyos intereses espirituales no sirven al “bien común”. Los portadores del auténtico principio masculino paulatinamente se convirtieron en los “hombres sobrantes” al estilo de algunos protagonistas de la literatura rusa. “Wozu ein Dichter?” (¿Para qué el poeta?) – preguntaba Hölderlin con ironía todavía a principios del siglo XIX. Ciertamente ¿para qué hacen falta en una sociedad pragmática los soñadores, los inventores de espejismos, de las doctrinas peligrosas y demás maestros de la presencia inquietante? Gotfied Benn reflejó la situación con exactitud en su maravilloso ensayo “Palas Atenea”:

“… representantes de un sexo que se está muriendo, útiles tan solo en su calidad de copartícipes en la apertura de las puertas del nacimiento… Ellos intentan conquistar la autonomía con sus sistemas, sus ilusiones negativas o contradictorias – todos estos lamas, budas, reyes divinos, santos y salvadores, quienes en realidad nunca han salvado a nadie, ni a nada – todos estos hombres trágicos, solitarios, ajenos a lo material, sordos ante la secreta llamada de la madre-tierra, lúgubres caminantes… En los estados de alta organización social, en los estados de duras alas, donde todo acaba en la normalidad con el apareamiento, los odian y toleran tan solo hasta que llegue el momento”.

Los estados de los insectos, sociedades de abejas y termitas están perfectamente organizados para los seres que “solo viven una vez”. La civilización occidental muy exitosamente se dirige hacia semejante orden ideal y en este sentido representa un episodio bastante raro en la historia. Es difícil encontrar en el pasado abarcable una formación humana, afianzada sobre las bases del ateísmo y una construcción estrictamente material del universo. Aquí no importa qué es lo que se coloca exactamente como la piedra angular: el materialismo vulgar o el materialismo dialéctico o los procesos microfísicos paradójicos. Cuando la religión se reduce al moralismo, cuando la alegría del ser se reduce a una decena de primitivos “placeres”, por los que además hay que pagar ni se sabe cuánto, cuando la muerte física aparece como “el final del todo” ¿acaso se puede hablar del impulso irracional y de la sublimación? Por eso en los años veinte Max Scheler ha desarrollado su conocida tesis sobre la “resublimación” como una de las principales tendencias del siglo. Según Scheler la joven generación ya no desea, a la manera de sus padres y abuelos, gastar las fuerzas en las improductivas búsquedas del absoluto: continuas especulaciones intelectuales exigen demasiada energía vital, que es mucho más práctico utilizar para la mejora de las condiciones concretas corporales, financieras y demás. Los hombres actuales ansían la ingenuidad, despreocupación, deporte, desean prolongar la juventud. El famoso filósofo Scheler, al parecer, saludaba semejante tendencia. ¡Si viera en lo que se ha convertido ahora este joven y empeñado en rejuvenecerse rebaño y de paso contemplara en lo que se ha convertido el deporte y otros entretenimientos saludables!

Y además.

¿Acaso la sublimación se reduce a las especulaciones intelectuales? ¿Acaso el impulso hacia adelante y hacia lo alto se reduce a los saltos de longitud y de altitud? La sublimación no se realiza en los minutos del buen estado de humor y no se acaba con la flojera. Tampoco es el éxtasis. Es un trabajo permanente y dinámico del alma para ampliar la percepción y transformar el cuerpo, es el conocimiento del mundo y de los mundos, atormentado aprendizaje del alpinismo celestial. Y además se trata de un proceso natural.

Si un hombre tiene miedo, rehúye o ni siquiera reconoce la llamada de la sublimación, es que, propiamente, no puede llamarse hombre, es decir un ser con un sistema irracional de valores marcadamente pronunciado. Incluso con la barba canosa o los bíceps imponentes seguirá siendo un niño, que depende totalmente de los caprichos de la “gran madre”. Obligando el espíritu a resolver los problemas pragmáticos, agotando el alma con la vanidad y la lascivia, siempre se arrastrará hasta sus rodillas buscando la consolación, los ánimos y el cariño.

Pero la “gran madre” no es en absoluto la amorosa Eva patriarcal, carne de la carne del hombre, es la siniestra creación de la eterna oscuridad, pariente próxima del caos primordial, no creado: bajo el nombre de Afrodita Pandemos envenena la sangre masculina con la pesadilla sexual, con el nombre de Cibeles le amenaza con la castración, la locura y le arrastra al suicidio. Algunos se preguntarán ¿qué relación tiene toda esta mitología con el conocimiento racional y ateísta? La más directa. El ateísmo no es más que una forma de teología negativa, asimilada de manera poco crítica o incluso inconsciente. El ateo cree ingenuamente en el poder total de la razón como instrumento fálico, capaz de penetrar hasta donde se quiera en las profundidades de la “madre-naturaleza”. Sucesivamente admirando la “sorprendente armonía que reina en la naturaleza” e indignándose ante las “fuerzas elementales, ciegas de la naturaleza” es como un niño mimado que quiere recibir de ella todo sin dar nada a cambio. Aunque últimamente, asustado ante las catástrofes ecológicas y la perspectiva de ser trasladado en un futuro próximo a las hospitalarias superficies de otros planetas, apela a la compasión y el humanismo.

Pero el “sol de la razón” no es más que el fuego fatuo del pantano y el instrumento fálico no es más que un juguete en las depredadoras manos de la “gran madre”. No se debe acercar al principio femenino que crea y que también mata con la misma intensidad. “Dama Natura” exige mantener la distancia y la veneración. Lo entendían bien nuestros patriarcales antepasados, teniendo cuidado de no inventar el automóvil, ni la bomba atómica, que ponían en los caminos la imagen del dios Término y escribían en las columnas de Hércules “non plus ultra”.

El espíritu se despierta en el hombre bruscamente y este proceso es duro, – esta es la tesis principal de Erich Neumann, un original seguidor de Jung, en su “Historia de la aparición de la conciencia”. El mundo orientado ginecocráticamente odia estas manifestaciones y procura acabar con ellas utilizando diferentes métodos. Lo que en la época moderna se entiende por “espiritualidad”, destaca por sus características específicamente femeninas: hacen falta memoria, erudición, conocimientos serios, profundos, un estudio pormenorizado del material – en una palabra, todo lo que se puede conseguir en las bibliotecas, archivos, museos, donde, cual si fuera el baúl de la vieja, se guardan todas las bagatelas. Si alguien se rebela contra semejante espiritualidad, siempre podrán acusarlo de ligereza, superficialidad, diletantismo, aventurerismo – características esencialmente masculinas. De aquí los degradantes compromisos y el miedo del individuo ante las leyes ginecocráticas del mundo exterior, que la psicología profunda en general y Erich Neumann en particular denominan el “miedo ante la castración”. “Tendencia a resistir, – escribe Erich Neumann, – el miedo ante la “gran madre”, miedo ante la castración son los primeros síntomas del rumbo centrípeto tomado y de la autoformación”. Y continúa:

“La superación del miedo ante la castración es el primer éxito en la superación del dominio de la materia”.

Erich Neumann. Urspruggeschichte des Bewusstseins, Munchen, 1975, p. 83

Ahora, en la era de la ginecocracia, semejante concepción constituye en verdad un acto heroico. Pero el “auténtico hombre” no tiene otro camino. Leamos unas líneas de Gotfried Benn del ya citado ensayo:

“De los procesos históricos y materiales sin sentido surge la nueva realidad, creada por la exigencia del paradigma eidético, segunda realidad, elaborada por la acción de la decisión intelectual. No existe el camino de retorno. Rezos a Ishtar, retournons a la grand mere, invocaciones al reino de la madre, entronización de Gretchen sobre Nietzsche – todo es inútil: no volveremos al estado natural”.

¿Es así?

Por un lado: conocimiento dulce, embriagador: sus vibraciones, movimientos gráciles, zonas erógenas… paraíso sexual.

Por el otro:

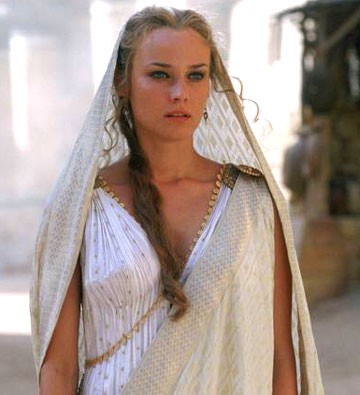

“Atenas, nacida de la sien de Zeus, de ojos azules, resplandeciente armadura, diosa nacida sin madre. Palas – la alegría del combate y la destrucción, cabeza de Medusa en su escudo, sobre su cabeza el lúgubre pájaro nocturno; retrocede un poco y de golpe levanta la gigantesca piedra que servía de linde – contra Marte, quien está del lado de Troya, de Helena… Palas, siempre con su casco, no fecundada, diosa sin hijos, fría y solitaria”.

1 de enero de 1999.

* Evgueni Golovín (1938-2010) fue un genio inclasificable. Situado completamente fuera del mundo actual, cuya legitimidad rechazaba de plano. “Quien camina contra el día no debe temer a la noche” – era su lema vital. Profundo conocedor de alquimia y de tradición hermética europea, también era especialista en los “autores malditos” franceses, románticos y expresionistas alemanes, traductor de libros de escritores europeos cuya obra está catalogada como “de la presencia inquietante”. Su identificación con el mundo pagano griego llegó al punto de que algunos que le conocieron íntimamente llegaron a definirlo como “Divinidad” (para empezar por el principio, Golovín aprendió el griego a los 16 años y comenzó con la lectura de Homero). En los años 60 del siglo pasado se convirtió en la figura más carismática de la llamada “clandestinidad mística moscovita”, conocido como “Almirante” (de la flotilla hermética, formada por los “místicos”). Fue el primero en la URSS en difundir la obra de autores tradicionalistas como Guénon y Évola. Ya en los años 90 y 2000 redactó la revista Splendor Solis, publicó varios libros y una recopilación de sus poemas. Veía con recelo las doctrinas orientales que consideraba poco adecuadas para el hombre europeo. Y, sobre todo, nunca buscó el centro de gravedad del ser en el mundo exterior. En su “navegación” sin fin siempre se mantuvo firmemente anclado a su interiore terra. El encuentro con Evgueni Golovín, en distintas etapas de sus vidas, fue decisivo para la formación de futuras figuras clave en la vida intelectual rusa como Geidar Dzhemal o

Alexandr Duguin

24/08/2012

Fuente: Poistine.com

(Traducido del ruso por Arturo Marián Llanos)

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : evgueni golovin, russie, littérature, littérature russe, lettres, lettres russes, traditions, gynécocratie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 13 octobre 2013

Living in Accordance with Our Tradition

Living in Accordance with Our Tradition

By Dominique Venner

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

Every great people own a primordial tradition that is different from all the others. It is the past and the future, the world of the depths, the bedrock that supports, the source from which one may draw as one sees fit. It is the stable axis at the center of the turning wheel of change. As Hannah Arendt put it, it is the “authority that chooses and names, transmits and conserves, indicates where the treasures are to be found and what their value is.”

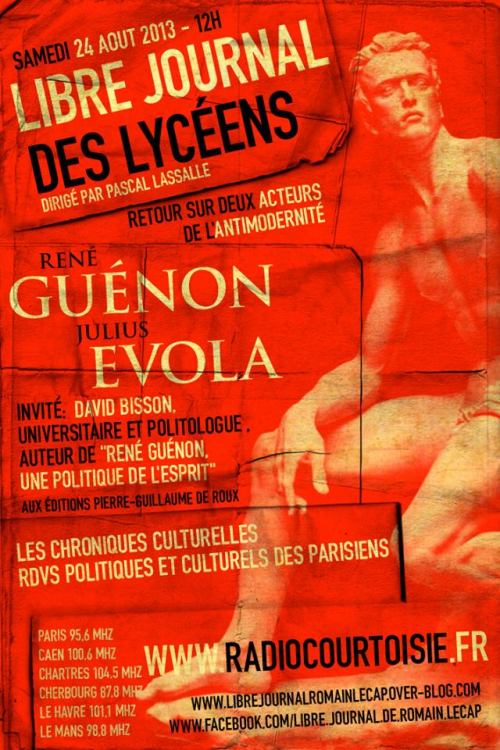

This dynamic conception of tradition is different from the Guénonian notion of a single, universal and hermetic tradition, which is supposedly common to all peoples and all times, and which originates in a revelation from an unidentified “beyond.” That such an idea is decidedly a-historical has not bothered its theoreticians. In their view, the world and history, for three or for thousand years, is no more than a regression, a fatal involution, the negation of of the world of what they call “tradition,” that of a golden age inspired by the Vedic and Hesiodic cosmologies. One must admit that the anti-materialism of this school is stimulating. On the other hand, its syncretism is ambiguous, to the point of leading some of its adepts, and not the least of them, to convert to Islam. Moreover, its critique of modernity has only lead to an admission of impotence. Unable to go beyond an often legitimate critique and propose an alternative way of life, the traditionalist school has taken refuge in an eschatological waiting for catastrophe.[1]

That which is thinking of a high standard in Guénon or Evola, sometimes turns into sterile rhetoric among their disciples.[2] Whatever reservations we may have with regard to the Evola’s claims, we will always be indebted to him for having forcefully shown, in his work, that beyond all specific religious references, there is a spiritual path of tradition that is opposed to the materialism of which the Enlightenment was an expression. Evola was not only a creative thinker, he also proved, in his own life, the heroic values that he had developed in his work.

In order to avoid all confusion with the ordinary meaning of the old traditionalisms, however respectable they might be, we suggest a neologism, that of “traditionism.”

For Europeans, as for other peoples, the authentic tradition can only be their own. That is the tradition that opposes nihilism through the return to the sources specific to the European ancestral soul. Contrary to materialism, tradition does not explain the higher through the lower, ethics through heredity, politics through interests, love through sexuality. However, heredity has its part in ethics and culture, interest has its part in politics, and sexuality has its part in love. However, tradition orders them in a hierarchy. It constructs personal and collective existence from above to below. As in the allegory in Plato’s Timaeus, the sovereign spirit, relying on the courage of the heart, commands the appetites. But that does not mean that the spirit and the body can be separated. In the same way, authentic love is at once a communion of souls and a carnal harmony.

Tradition is not an idea. It is a way of being and of living, in accordance with the Timaeus’ precept that “the goal of human life is to establish order and harmony in one’s body and one’s soul, in the image of the order of the cosmos.” Which means that life is a path towards this goal.

In the future, the desire to live in accordance with our tradition will be felt more and more strongly, as the chaos of nihilism is exacerbated. In order to find itself again, the European soul, so often straining towards conquests and the infinite, is destined to return to itself through an effort of introspection and knowledge. Its Greek and Apollonian side, which are so rich, offers a model of wisdom in finitude, the lack of which will become more and more painful. But this pain is necessary. One must pass through the night to reach the dawn.